Abstract

Misfolding and aggregation of transthyretin (TTR) is linked to amyloid disease. Amyloidosis occurs when the TTR homotetramer dissociates into aggregation-prone monomers that self-assemble into amyloid. In familial transthyretin amyloidosis, hereditary amino acid substitutions destabilize TTR and promote aggregation. In the present work, we used 19F-NMR to determine the effect of mutations, in the EF helix (Y78F, K80D, K80E, and A81T) and EF loop (G83R and I84S) on the aggregation kinetics and stability of the TTR tetramer and monomer. The EF region acts as a scaffold that stabilizes interactions in both the strong and weak dimer interfaces of the tetramer and is the site of a cluster of pathogenic mutations. K80D and K80E are non-natural mutants that destabilize the EF helix and yield an equilibrium mixture of tetramer and monomer at neutral pH, providing a unique opportunity to determine the thermodynamic parameters for tetramer assembly under non-denaturing conditions. Of the pathogenic mutants studied, only A81T formed appreciable monomer at neutral pH. Real-time 19F NMR measurements showed that the pathogenic Y78F mutation accelerates aggregation by destabilizing both the tetrameric and monomeric species. The pathogenic mutations A81T, G83R, and I84S destabilize the monomer and increase its aggregation rate by disrupting a Schellman helix C-capping motif. These studies provide new insights into the mechanism by which relatively subtle mutations that affect tetramer or monomer stability promote entry of TTR into the dissociation-aggregation pathway.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Transthyretin is a homotetrameric protein secreted into the blood and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) where it acts, respectively, as the secondary and primary carrier of thyroxin.1 Misfolding and aggregation of TTR is linked to amyloid diseases such as familial associated polyneuropathy and cardiomyopathy (FAP and FAC) and senile systemic amyloidosis (SSA; now called wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis, (ATTRwt). In all cases amyloidosis occurs in two steps. Firstly, in the rate limiting step, the tetramer dissociates into an aggregation-prone monomer,2–7 which then misfolds and aggregates via a downhill polymerization pathway,8 to form oligomers and amyloid. In ATTRwt, it is the wild type (WT) protein that undergoes amyloidosis, a disease that may affect up to 20% of people over the age of 80.9 In FAP and FAC, hereditary amino acid point mutations are responsible for destabilizing the tetramer and typically result in an earlier onset of disease than ATTRwt,10 depending on the denaturation energetics of the mutation.11 Many of these point mutants exhibit tissue-selective depositions and pathologies.12

The TTR tetramer consists of a dimer of dimers. Each protomer contains 8 β-strands, designated A-H, that are arranged in two β-sheets (formed from strands DAGH and CBEF) that form a β-sandwich,13,14 shown schematically together with the amino acid sequence in Figure S1. Hydrogen bonds between the H and H’ strands of adjacent protomers form the strong dimer interface (Figure S1C). Interactions between the F and F’ strands also contribute to this interface. Two strong dimers pack to form the tetramer via hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding interactions involving the AB and GH loops and the C-terminal region of strand H. This interface is referred to as the weak dimer interface (Figure S1D). The importance of hydrophobic packing for TTR tetramer formation and stability is demonstrated by the observation that the subunit exchange rates increase at lower temperatures.15

Dissociation of the tetramer is necessary but not sufficient to drive TTR amyloidosis; partial unfolding of the monomer is also a prerequisite for progression along the aggregation pathway.7,16 The factors that destabilize the tetramer and lead to formation of amyloidogenic monomers are only partially understood. Dissociation of the tetramer and entry into the aggregation pathway can be initiated in vitro at mildly acidic pH.2,6 An X-ray structure of the WT TTR tetramer at pH 4.0 revealed structural perturbations in the EF helix (residues D74-L82) and EF loop (residues G83-E89) relative to the pH 7 structure.17 This region is of particular interest since it acts as a scaffold that stabilizes interactions that form both the strong and weak dimer interfaces, has been implicated in amyloidogenesis, and is the locus of multiple pathogenic mutations (D74H, S77F/Y, Y78F, A81T/V, G83R, I84N/S/T). Maximum amyloid formation of WT TTR occurs at pH 4.4,3 and NMR resonances of residues in the EF helix of the TTR monomer are broadened at pH 4.4, indicating increased conformational fluctuations under conditions where fibril formation is maximal.18 The EF helix undergoes structural changes in the amyloid state, refolding to form two short β-strands in patient-derived fibrils.19,20 Previous studies have shown that TTR is highly sensitive to subtle structural changes in the EF region; substitution of W79 by 6-fluorotryptophan destabilizes the tetramer and increases its aggregation propensity, even though the fluorine atom has an atomic radius only 0.3 Å larger than the hydrogen it replaces.21

In the present work, we used our recently-reported 19F NMR probe22 to obtain new insights into the effect of pathogenic and non-natural mutations in the EF loop and helix on TTR tetramer stability and aggregation kinetics. Disease-causing mutations were introduced into the EF helix (Y78F and A81T) and EF loop (G83R and I84S). To probe the role of the EF helix in stabilizing the TTR tetramer, we introduced the non-natural, helix disrupting mutation K80D,23 with the less disruptive mutation K80E as a control. K80 is fully solvent exposed (Figure 1) so that mutations at this site would not be expected to disrupt tertiary contacts within the TTR structure. We hypothesized that K80 helps stabilize the helix through favorable interactions with the negative end of the helix dipole. Introduction of a charge reversal at this site provides an opportunity to test the effects of subtle changes in EF helix stability on the stability and aggregation kinetics of the TTR tetramer.

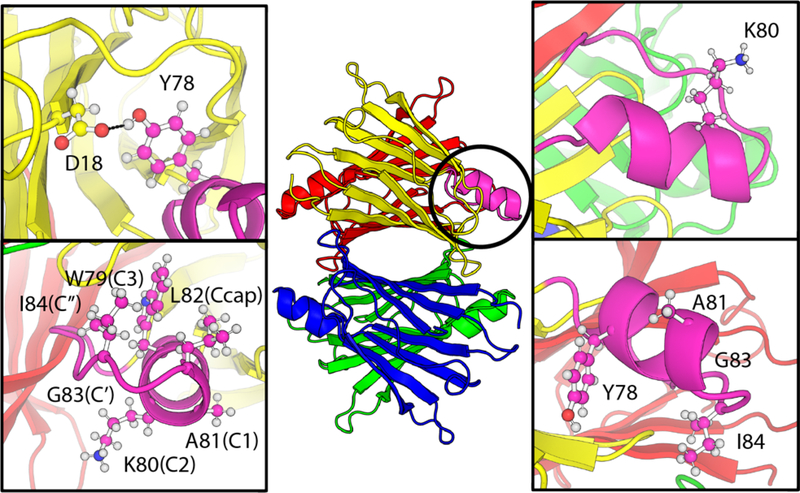

Figure 1:

Overall architecture of homotetrameric human TTR (PDBID 2ROX24). The four subunits are shown in different colors. The EF helix and loop are highlighted in magenta on the yellow protomer. The top left panel shows the hydrogen bond between the side chains of Y78 and D18 in the AB loop. The top right panel shows the location of K80 at the C-terminal end of the helix with the side chain fully solvent exposed. The bottom left panel shows the Schellman motif residues (labeled using the notation of Aurora et. al.25). Hydrophobic interactions between W79 (C3) and I84 (C”) are important for helix stability. The bottom right panel shows the location of naturally occurring pathogenic mutations in the EF helix and loop.

Materials and Methods:

Protein expression, purification, and labelling

The C10S/S85C variant of human TTR22 was used as the template for all subsequent mutations discussed in this paper. All constructs were encoded in a pET29a plasmid that includes an N-terminal methionine. Mutants were generated using the QuikChange kit (Agilent), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 Star (DE3) in minimal medium for isotopic labeling and purified by a previously described method22 except that dithiothreitol (DTT) was used instead of tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), the medium contained 30 μg.ml−1 kanamycin, and LB medium was used for samples that did not require isotopic enrichment. 15N labeled samples for NMR chemical shift perturbation (CSP) analysis were grown in M9 media with 1g/L (15NH4)2SO4, and 3g/L 12C-glucose.

Purified TTR samples were labeled with 3-bromo-1,1,1-trifluoroacetone (BTFA) as described previously.22 The various BTFA-labeled TTR constructs are designated using the notation TTRF (shorthand for C10S/S85C-BTFA), K80DF (C10S/ K80D/S85C-BTFA), etc. Unless otherwise noted, NMR samples were prepared in buffer containing 10 mM potassium phosphate, 100 mM KCl, at pH 7.0 (NMR buffer), and 10% D2O. The NMR buffer was extensively degassed with argon and NMR tubes were purged with argon before use. Spectra in low salt solution were acquired in buffer containing 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, and 10% D2O and no added KCl (0 mM KCl buffer).

NMR experiments

1H, 15N-TROSY-HSQC spectra26 were collected on a Bruker Avance 900 spectrometer equipped with a 5mm room temperature TXI probe with a triple axis gradient. Spectra were acquired with 2K complex points and 256 increments. The 15N carrier offset was at 118 ppm, the 1H carrier offset was at 4.7 ppm, spectral width 16 ppm, and the interscan relaxation delay was 1s. One-dimensional 19F NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker Avance 601 or Avance 700 spectrometers equipped with 1H/19F-13C/15N cryoprobes with z-gradients. Spectra were acquired with 4K complex points using a 19F pulse length of 10 μs, sweep width of 40 ppm, carrier offset at −84.2 ppm, and interscan relaxation delay of 1 s. At sample concentrations of 1.25 μM, the relaxation delay was shortened to 0.4 s to decrease the time required to acquire a spectrum. All NMR data were acquired using XWinNMR/TopSpin NMR, processed using NMRPipe,27 and analyzed and visualized by MATLAB and Sparky.28 For 1D 19F-NMR data processing, a 1-Hz exponential line-broadening factor was applied to the free induction decay which was then zero-filled to 16k before Fourier transformation. Unless otherwise stated, populations were calculated using peak areas and all uncertainties in NMR populations were calculated as one standard deviation of 50 bootstrapped data sets.

19F-NMR aggregation assay.

Real-time 19F-NMR aggregation assays were performed at 10 μM protomer concentration following a previously reported protocol.22 Briefly, 50 μl of a 100 μM solution of TTRF mutant in NMR buffer was mixed with 50μl D2O followed by 400μl 50 mM sodium acetate, 100 mM KCl at pH 4.4 to initiate aggregation. Corrections were made for the measurement dead time (<10 min, required for mixing, matching, tuning, and shimming the probe), so that t=0 in the kinetics data analyses corresponds to the time when the pH was lowered from 7.0 to 4.4. A series of 1D 19F NMR spectra was acquired to determine the time course of aggregation. Aggregation was also assayed by monitoring changes in optical density at 330 nm (OD330) according to.22

Fitting tetramer dissociation data

Concentration-dependent dissociation of the K80DF and K80EF tetramers was monitored by 19F NMR. The equilibrium constant for the T ⇌ 4M dissociation is:

By mass conversion we have:

where ct is the total concentration of TTR, expressed as the monomer concentration and quantified by an extinction coefficient of 18450 M−1 cm-1.

We then define the monomer molar fraction fM = [M]/ct, which is equivalent to the 19F peak area of monomer relative to the total 19F peak areas. By rearranging these three equations, we arrive at:

This quartic equation was numerically solved by the roots function and the residuals were minimized by the fminsearch function in MATLAB. The error was calculated as 1 standard deviation from 50 bootstrapped datasets.

Results

Effect of Helix Destabilizing Mutations on Tetramer Stability

To destabilize the EF helix, the solvent-exposed K80 was replaced by aspartate, a known helix breaker. The K80D mutation is expected to destabilize the helix both through interactions of the short carboxyl side chain with the helix backbone and, by virtue of its location on the last turn of the helix (Figure 1), through unfavorable interactions with the negative end of the helix dipole.23 As a control, K80 was also replaced by Glu, a helix favoring amino acid; Glu at this site would also interact unfavorably with the helix dipole but has the potential to form a stabilizing salt bridge with K76.

To determine the effect of the K80D/K80E mutations, we collected 19F NMR spectra of the BTFA-labeled constructs K80DF and K80EF in NMR buffer (pH7.0, 100mM KCl) at 298K, with [TTR]total = 25 μM and 1.25 μM, in the typical concentration ranges of TTR in the blood and in the CSF, respectively29 (Figure 2A). When [TTR]total = 25 μM, K80DF and K80EF have 5.0% and 3.0% population of monomer, respectively. However, when the concentration is lowered to 1.25 μM, the population of monomer increases to 40% and 20% for K80DF and K80EF, respectively. No monomer is detectable for TTRF at these concentrations. Thus, even a relatively conservative K80E substitution, which changes the charge at the C-terminus without affecting the stability of the helix, results in thermodynamic destabilization of the tetramer.

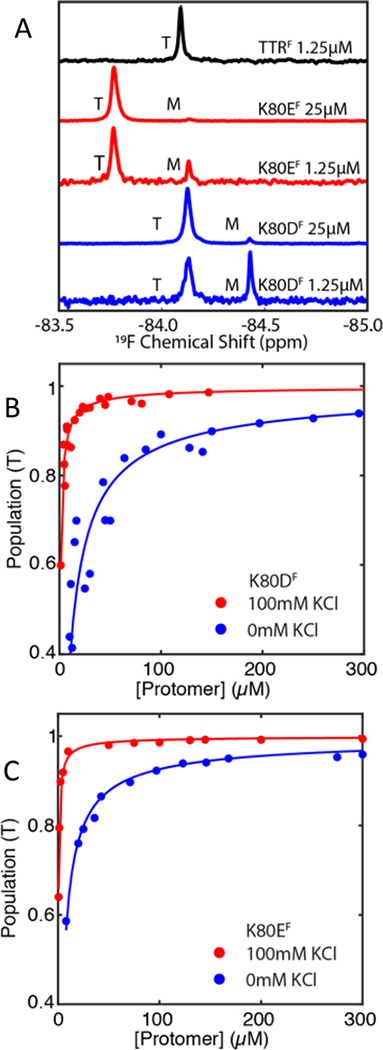

Figure 2:

(A) 19F-NMR spectra of BTFA labelled K80DF (blue), K80EF (red) and TTRF (black) at [TTR]total = 1.25 μM or 25 μM in NMR buffer (pH 7.0 at 298K). Intensity is normalized to the highest peak at the stated concentration.

(B) and (C) Changes in tetramer population as a function of the protomer concentration at 298 K (see Table 1). Data are shown for K80DF(B) and K80EF(C) in NMR buffer and in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, with 0 mM KCl

Measurement of Tetramer Stability by 19F NMR

The stability of the K80DF and K80EF tetramers was determined quantitatively by monitoring the tetramer and monomer populations in 19F NMR spectra recorded over a range of TTR concentrations (Figure 2B, C). Only tetramer and monomer resonances were observed; no peaks that could potentially arise from a dimeric intermediate were observed. Given the location of the BTFA probe near both the strong and weak dimer interfaces, a new 19F resonance would be expected if appreciable quantities of dimer accumulated. Spectra were acquired from samples in buffer containing 100 mM or 0 mM KCl at 298K and the populations of tetramer and monomer were determined from peak areas. The concentration dependence of the tetramer and monomer populations was fitted to two different dissociation models. In the first model, it was assumed that tetramer dissociates to dimer which immediately dissociates into monomer.5 The data were fitted to a single Kd for the equilibrium T ⇌ 2D, where [D] = [M]/2. This model does not fit the experimental 19F data well in the physiological concentration range (Figure S2). In the second model, the NMR data were fitted to a T ⇌ 4M equilibrium, as described in Materials and Methods. This model fitted the data with the lowest root mean squared error (fits shown in Figure 2B, C), giving Kd values of 1.3×10−19 M3 and 2.0×10−20 M3 for the K80DF and K80EF tetramers, respectively, in NMR buffer at 298K (Table 1). As expected,15 lowering the salt concentration of the NMR buffer to 0 mM KCl further destabilized the tetramer and led to an increased population of monomer (blue data points and fitted curves in Figure 2B, C), with Kd values of 1.6×10−15 M3 and 1.2×10−16 M3 for K80DF and K80EF respectively.

Table 1.

Tetramer dissociation constants and thermodynamic parameters determined from concentration dependence and temperature dependence of 19F NMR spectra.

| Data source | Parameter | WTe | K80DF | K80DF | K80EF | K80EF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [KCl] | 100 mM | 0 mM | 100 mM | 0 mM | ||

| Concentration Titrationa | Kd (M3) | 9 × 10−25 | 1.3 × 10−19 | 1.6 × 10−15 | 2.0 × 10−20 | 1.2 × 10−16 |

| ΔG (kcal.mol−1) | 32.8 | 25.7 | 20.1 | 26.8 | 21.6 | |

| van’t Hoff plotb | ΔH (kcal.mol−1) | −16.6 ± 0.3 | −17 ± 2 | −18 ± 2 | −17 ± 1 | |

| TΔS (kcal.mol−1)c | −41.8 ± 0.3 | −37 ± 2 | −44 ± 2 | −39 ± 1 | ||

| ΔG (kcal.mol−1)d | 25.2 | 20.3 | 25.9 | 21.8 |

Concentration titration performed in NMR Buffer (10mM sodium phosphate (pH7.0), 100mM KCl) at 298K.

Uncertainties in ΔH and TΔS are standard deviations from 3 measurements except for K80DF (100mM KCl) where the uncertainty is the standard error of two measurements.

TΔS at 298K

ΔG = ΔH - TΔS

Values from 30 measured from urea denaturation experiments.

Temperature Dependence of Tetramer Population

Since TTR folding and tetramer assembly are heavily dependent on the hydrophobic effect, we predicted that the population of tetramer would increase when the temperature is raised. Figure S3A shows the population of tetramer as a function of temperature for both K80DF and K80EF, for samples at [TTR]total = 30 μM in NMR buffer containing 0 mM or 100 mM KCl. In all cases the population of monomer increased as the temperature decreased. In the absence of salt, both mutant proteins were destabilized and were more sensitive to changes in temperature. In terms of stability: K80EF(salt)>K80DF(salt)>K80EF(no salt)>K80DF(no salt).

A van’t Hoff plot indicates that formation of monomer from tetramer is an exothermic process and is entropically disfavored (Figure S3B). The linearity of this plot suggests that enthalpy and entropy are constant over the temperature range (277 – 310K) studied. The thermodynamic parameters determined from the van’t Hoff plot are summarized in Table 1. Overall, a decrease in temperature favors the exothermic process of dissociation to monomers, and lowers its entropic cost (less negative TΔS), in accord with the well-known destabilization of the TTR tetramer at lower temperatures.15

Structural Perturbations Caused by K80D/E Mutations

To obtain insights into potential structural perturbations that may lead to tetramer destabilization, 1H,15N -HSQC spectra of K80DF and K80EF were acquired (Figures S4 and S5) to determine backbone amide chemical shift perturbations (CSP) relative to the parent TTRF (Figure S6). Changes in chemical shift are generally very small, indicating that the overall TTR structure is not significantly perturbed. The largest CSPs are in the immediate vicinity of the mutation site, revealing subtle changes in structure or hydrogen bonding at the C-terminal end of the helix and beginning of the EF loop, with the Asp substitution causing slightly larger chemical shift changes than Glu. No significant chemical shift changes are observed at distant sites, indicating that the effects of the K80D and K80E substitutions are entirely local.

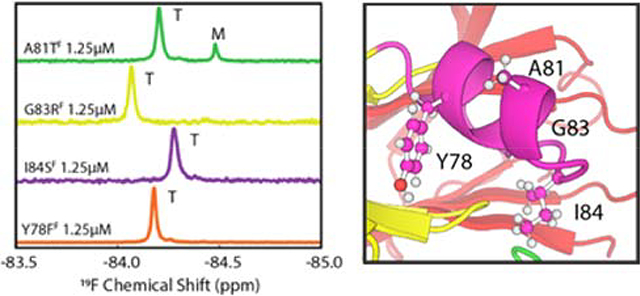

Effect of pathogenic mutations in EF helix and loop

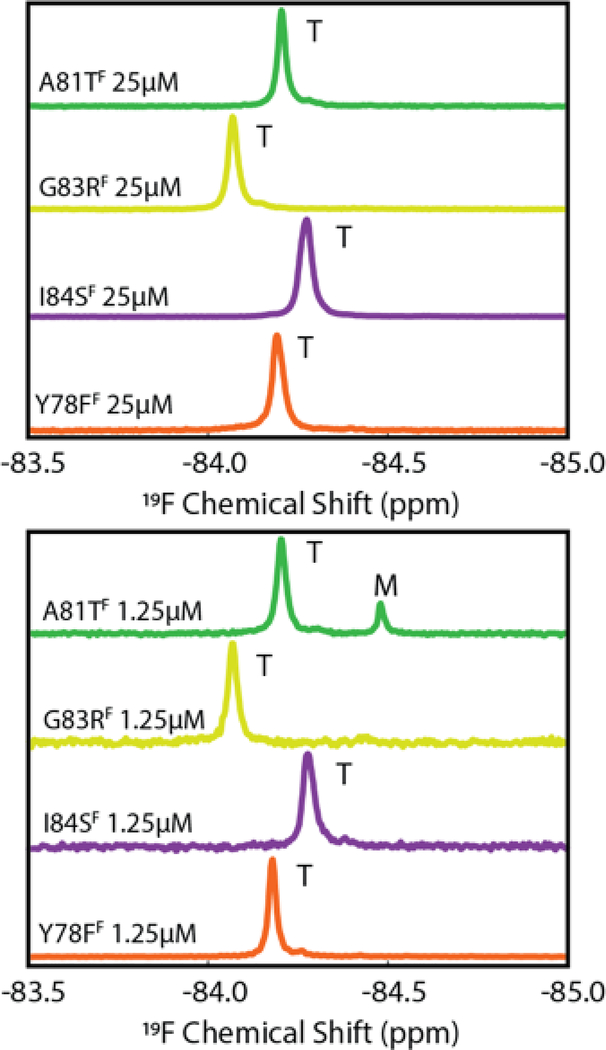

While K80D and K80E provide new insights into the importance of the helix in determining tetramer stability, these mutants do not occur naturally. We therefore generated four TTRF variants, Y78FF, A81TF, G83RF, and I84SF, with naturally-occurring pathogenic mutations in the EF helix and loop. 19F NMR spectra at [TTR]total = 25.0 μM and 1.25 μM are shown in Figure 3. With the exception of A81TF, which contained 17% population of monomer at 1.25 μM, the variant TTRs were fully tetrameric at both concentrations.

Figure 3.

19F spectra of pathogenic EF helix mutants at 298K in pH 7.0 NMR buffer containing 100 mM KCl. Spectra were recorded at 25 μM (upper panel) and 1.25 μM (lower panel) TTR concentration. The scale of each spectrum is normalized to the highest peak at the stated concentration.

Kinetics of aggregation

Since the 19F NMR spectra show that the K80DF and K80EF tetramers are destabilized relative to the parent TTRF and spontaneously form 20 – 40% monomer upon dilution to 1.25 μM, we investigated their aggregation kinetics using our recently developed 19F-NMR aggregation assay22 and turbidity measurements at 330 nm. Our expectation was that the mutants would exhibit increased aggregation rates since the tetrameric structure has been destabilized. We also used 19F NMR to measure the aggregation kinetics of the pathogenic Y78FF, A81TF, G83RF, and I84SF variants.

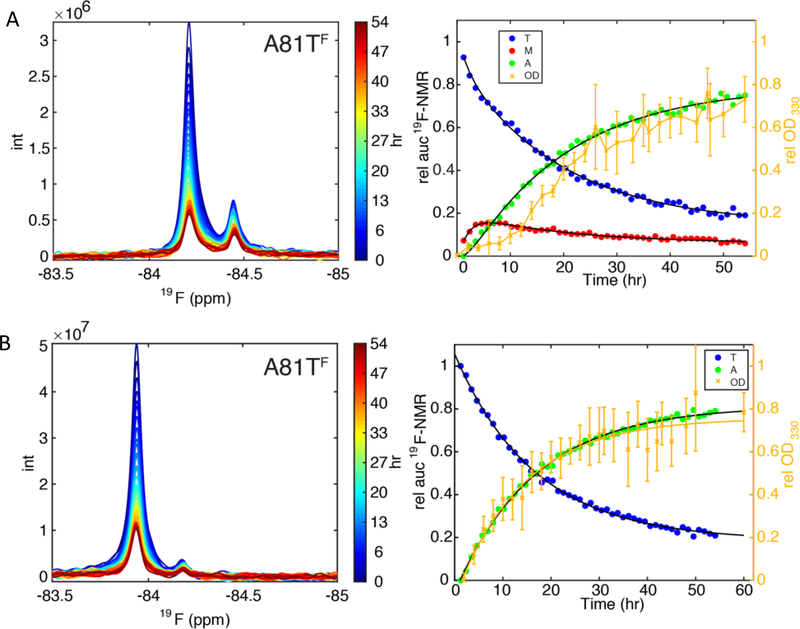

For each TTR variant, aggregation was initiated by diluting the protein to 10 μM protomer concentration in pH 4.4 buffer. Aggregation was then monitored by real-time 19F NMR, as illustrated in Figure 4B and S7A for experiments performed at 310K and Figure 4A and S7B for those performed at 298K.

Figure 4.

Monitoring aggregation kinetics of A81TF at pH 4.4 (A) at 298K and (B) at 310K, using 19F-NMR and OD330 measurements. The left panels show the overlaid time series of 19F-NMR spectra with raw peak heights. The right panels show normalized 19F-NMR and OD330 data. The 19F-NMR peak areas (left black axis) and OD330 (right gold axis) are plotted as a function of aggregation time. The data points are colored blue for tetramer (T). At 298K, growth and decay of a well-separated monomer peak (M) is observed (red data points), which is much less populated at 310K, thus not quantified. Green points represent the missing NMR signal amplitude for the ensemble of aggregates (A) and are derived by subtracting normalized T (at 310K) or T+M intensity (at 298K) from 1. The maximal OD330 is normalized to the maximum of the A signal for convenience of comparison. The black lines in (A) show the fits of the NMR kinetic data based on the two-step reversible kinetic scheme while those in (B) are single exponential fits. The orange connecting lines in (A) are for guidance of the eye only and those in (B) are single exponential fits to the OD signal. Kinetic data are shown in Table 2. Data for the remaining 5 mutants are shown in Figure S7.

The total 19F signal intensity decreases with time due to formation of aggregated species that cannot be observed by NMR. At 298K the time-dependent changes in 19F peak area were fitted to a reversible two-step kinetic scheme:

where T denotes tetramer, M is the monomer, and A represents an ensemble of NMR-invisible aggregated species, as described in detail elsewhere.22 The fitted kinetic parameters are summarized in Table 2. At 310K all variants were fitted to a single exponential rate, kslow (Table 2). Although small amounts of monomer were observed for K80DF, K80EF, and A81TF, the populations were too small for accurate quantitation and the data were fitted to the dominant single exponential decay.

Table 2:

Aggregation kinetics determined by real-time 19F NMR.

| Mutant | Temp (K) | k1 (h−1) | k−1 (h−1) | k2 (h−1) | k−2 (h−1) | γ2b (h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTRF (a) | 298 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.63 ± 0.10 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| 310 | γ2 = 0.06 ± 0.01 | |||||

| K80DF | 298 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 |

| 310c | kslow = 0.14 ± 0.01 | |||||

| K80EF | 298 | 0.17 ± 0.08 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| 310c | kslow = 0.06 ± 0.01 | |||||

| Y78FF | 298 | 0.49 ± 0.07 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.64 ± 0.03 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.01 |

| 310c | kslow = 0.30 ± 0.02 | |||||

| A81TF | 298 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.23 ± 0.09 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| 310c | kslow = 0.06 ± 0.01 | |||||

| G83RF | 298 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.39 ± 0.07 | 0.01 ±0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| 310c | kslow = 0.06 ± 0.01 | |||||

| I84SF | 298 | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.01 |

| 310c | kslow = 0.08 ± 0.01 | |||||

Data for TTRF from 22

γ2 is the slower relaxation rate defined in 22 and represents the rate of increase of A in the aggregation scheme used here.

The population of monomer intermediate is small or unobservable and the decay of the tetramer peak was fitted to a single exponential with rate kslow which approximates the relaxation rate γ2.22

Discussion

Previous studies have established that entry into and progression along the transthyretin aggregation pathway requires both dissociation of the tetramer and partial unfolding of the resulting monomer.2–5,7,16 More than 120 single-site mutations that are associated with familial amyloid disease have been identified (http://amyloidosismutations.com/mut-attr.php), but insights into the mechanisms by which these mutations drive amyloidosis are mostly lacking. Elucidation of the general molecular determinants of TTR tetramer and monomer stability, and how stability is modulated by pathogenic mutations, is therefore of great interest and importance. In the present work, we have examined the effects of pathogenic and non-natural mutations in the EF helix and EF loop, an area distant from the subunit interfaces, on the stability and aggregation kinetics of TTR. Our results reveal that the TTR tetramer is poised on the threshold of stability, such that even a modest charge reversal, K80E, near the C-terminal end of the EF helix is sufficient to thermodynamically destabilize the tetramer.

The K80E substitution, at a site that is one turn from the C-terminus of the EF helix, has an effect on helix stability that varies with the side chain charge. At pH 7, where the Glu carboxyl is deprotonated, the K80E mutation destabilizes the helix by placing a negative charge close to the negative end of the helix macrodipole.31 As a consequence, the tetramer is destabilized and dissociates to form a substantial population of monomer as the K80EF concentration is decreased (Figure 2C). The monomer population is dependent upon the salt concentration and is decreased in the presence of 100 mM KCl, which partially screens the unfavorable charge-helix dipole interaction and stabilizes the tetramer by screening electrostatic repulsion between K15 side chains on opposing subunits.15 The K80D substitution is even more destabilizing than K80E due to the proximity of the carboxylate group to the helix backbone23 and, under the same conditions, a higher monomer population is observed for K80DF (Figure 2B). The pKas of Asp and Glu side chains in the C-terminal region of a helix are increased by interactions with the negative end of the helix dipole.23,31 At pH 4.4, where the E80 and D80 side chains are likely to be fully or partially protonated, the destabilizing charge-dipole interactions are relieved and the apparent tetramer dissociation constants (= k1/k-1, Table 2) of K80EF and K80DF are similar to that of the parent TTRF (0.26, 0.19 and 0.21, respectively).

The K80D and K80E mutations provide a unique opportunity to directly determine thermodynamic parameters for the tetramer – monomer equilibrium under non-denaturing conditions using 19F NMR. To date, the stability of WT and mutant TTR tetramers could be determined only under denaturing conditions, by fitting concentration-dependent urea denaturation data or by denaturing the tetramer at high pressure and low temperature.30,32 The high sensitivity of the 19F NMR spectrum allows us to directly measure the relative populations of tetramer and monomer over a range of K80DF and K80EF concentrations from 1 – 300 μM (Figure 2). In buffer containing 100 mM KCl, the K80DF and K80EF tetramers are 7.0 and 5.9 kcal.mol−1 less stable than the WT TTR tetramer, respectively (Table 1). By measuring the temperature dependence of the K80DF and K80EF NMR spectra, we obtained the first insights into the thermodynamics of tetramer formation (Table 1). Tetramer formation is enthalpically unfavorable but is strongly favored by the product of temperature and entropy (ΔH = 16.6 kcal.mol−1, TΔS = 41.8 kcal.mol−1 for formation of the K80DF tetramer in 100 mM KCl at 298K), highlighting the importance of hydrophobic packing in stabilization of the tetramer at high temperatures compared to low temperatures.15,33 The large increase in entropy upon association of the subunits is probably associated with release of hydration water from the exposed hydrophobic surfaces of the monomers. The well-known effect of salt in stabilization of the TTR tetramer is seen to be entirely entropy driven: increasing the KCl concentration from 0 to 100 mM increases TΔS for tetramer formation by ~5 kcal.mol−1 for both K80DF and K80EF while there is no change in enthalpy within the experimental uncertainties (Table 1). These results are in accord with molecular dynamics simulations which show that high-charge-density ions enhance hydrophobic interactions between surfaces by a purely entropic effect.34

Aggregation kinetics at pH 4.4 and 310K were measured both by real-time 19F NMR and by optical density (Figure 4B and S7A). At this temperature, loss of intensity of the tetramer peak and increase in OD330 is monophasic and dominated by the slow step in the aggregation pathway (Table 2). At 298K, however, formation of a transient monomeric intermediate can be observed directly by 19F NMR (Figure 4A and S7B), providing important insights into the detailed mechanisms by which EF helix and loop mutations promote TTR aggregation. Although the TTR tetramer is thermodynamically destabilized by the glutamate side chain of K80E at physiological pH, the aggregation kinetics of K80EF at pH 4.4, where the Glu carboxyl would be largely protonated, are indistinguishable from those of TTRF (Table 2). In contrast, K80DF aggregates more rapidly than TTRF; while both tetramers have similar stability (similar values of k1 and k-1) at 298K, the monomeric intermediate is destabilized by the mutation and proceeds more rapidly to NMR-invisible aggregates (k2 = 0.44 h−1 for K80DF versus 0.06 h−1 for TTRF) (Table 2). The behavior of the K80E and K80D substitutions at low pH can be understood from their differing effects on helix stability;35 the uncharged Glu side chain is helix stabilizing while Asp, even in its uncharged state, is helix destabilizing and promotes aggregation of the monomer.

The EF helix (residues T75 – L82) and EF loop (residues G83 – E89) are the locus of a cluster of pathogenic mutations (http://amyloidosismutations.com/mut-attr.php). We used real-time 19F NMR to elucidate the mechanism by which representative mutations in this region destabilize TTR, accelerate aggregation, and cause amyloid disease. Only one of the studied pathogenic variants (A81T) led to substantial thermodynamic destabilization of the tetramer at physiological pH in 100 mM KCl, exhibiting a 17% population of monomer at 1.25 μM concentration (Figure 3). However, at pH 4.4 and 298K, all of the variants aggregate via a two-step pathway involving a monomeric intermediate (Figure 4A and S7B).

The Y78F mutant is highly amyloidogenic and is associated with peripheral neuropathy and cardiomyopathy.36,37 In WT TTR, Y78 helps anchor the EF helix to the TTR core by way of hydrophobic interactions and a hydrogen bond between the tyrosine hydroxyl group and the carboxyl group of D18 in the AB loop (Figure 1). D18 plays a critical role in stabilization of the weak dimer interface; substitution by Gly in the pathogenic D18G variant destabilizes the AB loop, disrupts the weak dimer interface, and renders the protein monomeric.38,39 The structure of the Y78F variant is almost indistinguishable from that of WT TTR.40 However, our measurements of aggregation kinetics by real-time 19F NMR show that disruption of the hydrogen bond to D18 destabilizes both the tetramer and monomer, increasing the rate of tetramer dissociation (k1 = 0.49 h−1 for Y78FF vs 0.13 h−1 for TTRF at 298K) and of monomer unfolding and aggregation (k2 = 0.64 h−1 for Y78FF vs 0.06 h−1 for TTRF) (Table 2). These observations underscore the importance of the Y78 – D18 hydrogen bond for maintaining the structural integrity of the AB loop and weak dimer interface and for stabilizing the EF helix packing.

At pH 4.4 and 298K, where aggregation proceeds via an observable monomeric intermediate, the A81TF, G83RF, and I84SF tetramers dissociate at similar rates to the parent TTRF (Table 2). However, for each of these variants, the monomers are destabilized by the mutations and aggregate 2- to 6-fold faster than the TTRF monomer (k2 = 0.15 h−1 for A81TF, 0.39 h−1 for G83RF, and 0.39 h−1 for I84SF vs 0.06 h−1 for TTRF). Thus, these EF loop variants have little effect on the rate of dissociation of the tetramer, but they accelerate oligomerization by destabilization of the monomer. Although the A81T mutation does not change the rate of tetramer dissociation, it does decrease the rate of re-association of the monomer (k-1 = 0.23 h−1 for A81TF vs 0.63 h−1 for TTRF), consistent with the observed destabilization of the A81TF tetramer at pH 7 (Figure 3).

The mechanism by which pathogenic mutations in the EF loop promote aggregation can be understood in terms of their effects on capping of the EF helix. The EF loop functions as a classic Schellman helix C-capping motif.25 In the notation of Aurora et al.,25 the C-terminal residues of the helix and capping residues are designated:

where C3, C2, and C1 belong to the EF helix, the Ccap residue is at the boundary between the helix and the EF loop, and C’ and C” are EF loop residues that cap and stabilize the helix (Figure 1). The key sites of the Schellman motif are C3, C’, and C”; substitution of disallowed residues at these sites is highly destabilizing. Hydrophobic interactions between C3 (W79 in TTR) and C”(I84) are critical for helix stabilization;25 the known pathogenic mutations at C” (I84S, I84N, I84T) would abrogate these interactions and thereby destabilize the EF helix. Indeed, the importance of a bulky hydrophobic residue at position 84 is confirmed by X-ray structures of the I84S and I84A variants; at pH 7.5, the structures are virtually identical to WT TTR but at pH 4.6 the EF helix is unwound and the loop conformation rearranged in two subunits of the tetramer.41 The C’ residue of the Schellman motif must be in the αL backbone conformation, with a positive φ angle; Gly is strongly conserved at this position25 and substitution of G83 by Arg, for which the αL conformation is unfavorable, is highly destabilizing and leads to a 6-fold increase in the rate of aggregation of the monomer (k2 = 0.39 s−1 vs 0.06 s−1 for TTRF, Table 2). Finally, Ala is strongly favored at position C1 of the helix and substitution by branched side chains in the pathogenic variants A81T and A81V destabilizes the monomer and enhances aggregation.

Conclusions

The present study shows clearly that residues in the EF helix and EF loop are involved in critical interactions that contribute to the structural stability of both the TTR tetramer and monomer and that mutations that perturb these interactions predispose TTR towards aggregation. Mutations that destabilize the EF helix by disrupting packing interactions with the core (Y78F) or by perturbing capping interactions or helical propensity (K80D/E, A81T, G83R, I84S) accelerate monomer unfolding and aggregation. Remodeling of the EF helix and loop is an essential step towards fibril formation19,20 and mutations that destabilize the native conformation probably increase k2 by lowering the energy barrier for helix unfolding. Amongst the pathogenic variants studied in the present work, only Y78F, which disrupts a critical hydrogen bond to the AB loop, destabilizes the tetramer directly and increases its rate of dissociation. The present work provides important new insights into the mechanisms by which pathogenic mutations destabilize transthyretin and promote fibrillogenesis and amyloid disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Maria Martinez-Yamout for discussions and advice on protein preparation, Gerard Kroon for assistance with NMR experiments, and Euvel Manlapaz for technical assistance. We thank Jeffrey Kelly for valuable discussion.

Funding:

This work was supported by grants DK34909 (PEW) and GM131693 (HJD) from the National Institutes of Health, and American Heart Association Grant # 20POST35050060 (to X.S.).

Footnotes

Accession Codes:

Human transthyretin: P02766

Supporting Information:

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website. Fits of an alternative model involving T and D, van ‘t Hoff plots of the T ⇌ 4M equilibrium of K80DF and K80EF, 1H 15N-TROSY spectra of K80D and K80E with associated CSPs, and 19F-NMR and OD330 aggregation data of the remaining 5 TTR mutants in this work.

References

- (1).Johnson SM, Connelly S, Fearns C, Powers ET, and Kelly JW (2012) The transthyretin amyloidoses: from delineating the molecular mechanism of aggregation Linked to pathology to a regulatory-agency-approved drug, J. Mol. Biol. 421, 185–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Colon W, and Kelly JW (1992) Partial denaturation of transthyretin is sufficient for amyloid fibril formation in vitro, Biochemistry 31, 8654–8660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Lai Z, Colon W, and Kelly JW (1996) The acid-mediated denaturation pathway of transthyretin yields a conformational intermediate that can self-assemble into amyloid, Biochemistry 35, 6470–6482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Quintas A, Saraiva MJM, and Brito RMM (1999) The tetrameric protein transthyretin dissociates to a non-native monomer in solution: a novel model for amyloidogenesis, J. Biol. Chem. 274, 32943–32949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Foss TR, Wiseman RL, and Kelly JW (2005) The pathway by which the tetrameric protein transthyretin dissociates, Biochemistry 44, 15525–15533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Lashuel HA, Lai Z, and Kelly JW (1998) Characterization of the transthyretin acid denaturation pathways by analytical ultracentrifugation: implications for wild-type, V30M, and L55P amyloid fibril formation, Biochemistry 37, 17851–17864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Quintas A, Vaz DC, Cardoso I, Saraiva MJ, and Brito RM (2001) Tetramer dissociation and monomer partial unfolding precedes protofibril formation in amyloidogenic transthyretin variants, J. Biol. Chem. 276, 27207–27213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hurshman AR, White JT, Powers ET, and Kelly JW (2004) Transthyretin aggregation under partially denaturing conditions is a downhill polymerization, Biochemistry 43, 7365–7381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Pitkänen P, Westermark P, and Cornwell GG 3rd. (1984) Senile systemic amyloidosis, Am. J. Pathol. 117, 391–399. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Connors LH, Lim A, Prokaeva T, Roskens VA, and Costello CE (2003) Tabulation of human transthyretin (TTR) variants, 2003, Amyloid Int. J. Exp. Clin. Invest. 10, 160–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Hammarström P, Jiang X, Hurshman AR, Powers ET, and Kelly JW (2002) Sequence-dependent denaturation energetics: A major determinant in amyloid disease diversity, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 Suppl 4, 16427–16432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Sekijima Y, Wiseman RL, Matteson J, Hammarström P, Miller SR, Sawkar AR, Balch WE, and Kelly JW (2005) The biological and chemical basis for tissue-selective amyloid disease, Cell 121, 73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Palaninathan SK (2012) Nearly 200 X-ray crystal structures of transthyretin: what do they tell us about this protein and the design of drugs for TTR amyloidoses?, Curr. Med. Chem. 19, 2324–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hamilton JA, and Benson MD (2001) Transthyretin: a review from a structural perspective, Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58, 1491–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Schneider F, Hammarström P, and Kelly JW (2001) Transthyretin slowly exchanges subunits under physiological conditions: A convenient chromatographic method to study subunit exchange in oligomeric proteins, Protein Sci. 10, 1606–1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Jiang X, Smith CS, Petrassi HM, Hammarström P, White JT, Sacchettini JC, and Kelly JW (2001) An engineered transthyretin monomer that is nonamyloidogenic, unless it is partially denatured, Biochemistry 40, 11442–11452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Palaninathan SK, Mohamedmohaideen NN, Snee WC, Kelly JW, and Sacchettini JC (2008) Structural insight into pH-induced conformational changes within the native human transthyretin tetramer, J. Mol. Biol. 382, 1157–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Lim KH, Dyson HJ, Kelly JW, and Wright PE (2013) Localized structural fluctuations promote amyloidogenic conformations in transthyretin, J. Mol. Biol. 425, 977–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Dasari AKR, Hung I, Michael B, Gan Z, Kelly JW, Connors LH, Griffin RG, and Lim KH (2020) Structural characterization of cardiac ex vivo transthyretin amyloid: insight into the transthyretin Mmisfolding pathway In Vivo, Biochemistry 59, 1800–1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Schmidt M, Wiese S, Adak V, Engler J, Agarwal S, Fritz G, Westermark P, Zacharias M, and Fändrich M (2019) Cryo-EM structure of a transthyretin-derived amyloid fibril from a patient with hereditary ATTR amyloidosis, Nat. Commun. 10, 5008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Sun X, Dyson HJ, and Wright PE (2017) Fluorotryptophan incorporation modulates the structure and stability of transthyretin in a site-specific manner, Biochemistry 56, 5570–5581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Sun X, Dyson HJ, and Wright PE (2018) Kinetic analysis of the multistep aggregation pathway of human transthyretin, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E6201–E6208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Huyghues-Despointes BMP, Scholtz JM, and Baldwin RL (1993) Effect of a single aspartate on helix stability at different positions in a neutral alanine-based peptide, Protein Sci. 2, 1604–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Wojtczak A, Cody V, Luft JR, and Pangborn W (1996) Structures of human transthyretin complexed with thyroxine at 2.0 A resolution and 3’,5’-dinitro-N-acetyl-L-thyronine at 2.2 A resolution, Acta Cryst. D 52, 758–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Aurora R, Srinivasan R, and Rose GD (1994) Rules for α-helix termination by glycine, Science 264, 1126–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Pervushin K, Riek R, Wider G, and Wüthrich K (1997) Attenuated T2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole-dipole coupling and chemical shift anisotropy indicates an avenue to NMR structures of very large biological macromolecules in solution, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 12366–12371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Guang Z, Pfeifer J, and Bax A (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes, J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Lee W, Tonelli M, and Markley JL (2015) NMRFAM-SPARKY: enhanced software for biomolecular NMR spectroscopy, Bioinformatics 31, 1325–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Johnson SM, Wiseman RL, Sekijima Y, Green NS, Adamski-Werner SL, and Kelly JW (2005) Native state kinetic stabilization as a strategy to ameliorate protein misfolding diseases:a focus on the transthyretin amyloidoses, Acc. Chem. Res. 38, 911–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Hurshman Babbes AR, Powers ET, and Kelly JW (2008) Quantification of the thermodynamically linked quaternary and tertiary structural stabilities of transthyretin and its disease-associated variants: the relationship between stability and amyloidosis, Biochemistry 47, 6969–6984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Scholtz JM, Qian H, Robbins VH, and Baldwin RL (1993) The energetics of ion-pair and hydrogen-bonding interactions in a helical peptide, Biochemistry 32, 9668–9676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Azevedo EPC, Pereira HM, Garratt RC, Kelly JW, Foguel D, and Palhano FL (2011) Dissecting the structure, thermodynamic stability, and aggregation properties of the A25T transthyretin (A25T-TTR) variant involved in leptomeningeal amyloidosis: identifying protein partners that co-aggregate during A25T-TTR fibrillogenesis in cerebrospinal fluid, Biochemistry 50, 11070–11083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Hammarström P, Jiang X, Deechongkit S, and Kelly JW (2001) Anion shielding of electrostatic repulsions in transthyretin modulates stability and amyloidosis: insight into the chaotrope unfolding dichotomy, Biochemistry 40, 11453–11459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Zangi R, Hagen M, and Berne BJ (2007) Effect of ions on the hydrophobic interaction between two plates, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 4678–4686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Chakrabartty A, Kortemme T, and Baldwin RL (1994) Helix propensities of the amino acids measured in alanine-based peptides without helix-stabilizing side-chain interactions, Protein Sci. 3, 843–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Magy N, Liepnieks JJ, Gil H, Kantelip B, Dupond JL, Kluve-Beckerman B, and Benson MD (2003) A transthyretin mutation (Tyr78Phe) associated with peripheral neuropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome and skin amyloidosis, Amyloid Int. J. Exp. Clin. Invest. 10, 29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Anesi E, Palladini G, Perfetti V, Arbustini E, Obici L, and Merlini G (2001) Therapeutic advances demand accurate typing of amyloid deposits, American Journal of Medicine 111, 243–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Connors LH, Yamashita T, Yazaki M, Skinner M, and Benson MD (2004) A rare transthyretin mutation (Asp18Glu) associated with cardiomyopathy, Amyloid Int. J. Exp. Clin. Invest. 11, 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Hammarström P, Sekijima Y, White JT, Wiseman RL, Lim A, Costello CE, Altland K, Garzuly F, Budka H, and Kelly JW (2003) D18G Transthyretin is monomeric, aggregation prone, and not detectable in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid: A prescription for central nervous system amyloidosis?, Biochemistry 42, 6656–6663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Neto-Silva RM, Macedo-Ribeiro S, Pereira PJB, Coll M, Saraiva MJ, and Damas AM (2005) X-ray crystallographic studies of two transthyretin variants: further insights into amyloidogenesis, Acta Cryst. D 61, 333–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Pasquato N, Berni R, Folli C, Alfieri B, Cendron L, and Zanotti G (2007) Acidic pH-induced conformational changes in amyloidogenic mutant transthyretin, J. Mol. Biol. 366, 711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.