Abstract

Background

National guidelines recommend 10 days of antibiotics for children with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), acknowledging that the outcomes of children hospitalized with CAP who receive shorter durations of therapy have not been evaluated.

Methods

We conducted a comparative effectiveness study of children aged ≥6 months hospitalized at The Johns Hopkins Hospital who received short-course (5–7 days) vs prolonged-course (8–14 days) antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated CAP between 2012 and 2018 using an inverse probability of treatment weighted propensity score analysis. Inclusion was limited to children with clinical and radiographic criteria consistent with CAP, as adjudicated by 2 infectious diseases physicians. Children with tracheostomies; healthcare-associated, hospital-acquired, or ventilator-associated pneumonia; loculated or moderate to large pleural effusion or pulmonary abscess; intensive care unit stay >48 hours; cystic fibrosis/bronchiectasis; severe immunosuppression; or unusual pathogens were excluded. The primary outcome was treatment failure, a composite of unanticipated emergency department visits, outpatient visits, hospital readmissions, or death (all determined to be likely attributable to bacterial pneumonia) within 30 days after completing antibiotic therapy.

Results

Four hundred and thirty-nine patients met eligibility criteria; 168 (38%) patients received short-course therapy (median, 6 days) and 271 (62%) received prolonged-course therapy (median, 10 days). Four percent of children experienced treatment failure, with no differences observed between patients who received short-course vs prolonged-course antibiotic therapy (odds ratio, 0.48; 95% confidence interval, .18–1.30).

Conclusions

A short course of antibiotic therapy (approximately 5 days) does not increase the odds of 30-day treatment failure compared with longer courses for hospitalized children with uncomplicated CAP.

Keywords: antibiotics, bacterial pneumonia, duration of therapy, pediatrics

National guidelines recommend 10 days of antibiotics for children with community-acquired pneumonia. In a propensity-weighted cohort of 439 children hospitalized for uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia, short-course antibiotic therapy (median, 6 days) resulted in similar outcomes as prolonged-course therapy (median, 10 days).

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is one of the most common reasons children are hospitalized in the United States [1]. Children hospitalized for pneumonia receive more days of antibiotic therapy than those hospitalized for any other condition [2]. The 2011 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS) guidelines state that “treatment courses of 10 days have been best studied [for children with pneumonia], although shorter courses may be just as effective (strong recommendation; moderate-quality evidence)” [3]. These guidelines also emphasize the importance of research to identify the shortest effective duration of therapy to minimize patient harms, including the development of antibiotic resistance and drug-related toxicities.

Multiple randomized, controlled trials have demonstrated that clinical outcomes with short-course antibiotic therapy (generally consisting of 5 days) are equivalent to longer courses for hospitalized adults with CAP [4–10]. Several meta-analyses have corroborated these findings [11–13]. The abundance of evidence supporting short-course therapy has prompted the IDSA and American Thoracic Society to recommend 5 days of antibiotics for the treatment of adults hospitalized with uncomplicated CAP [14].

There are no data available from randomized, controlled trials or even robust observational studies that evaluate the optimal duration of therapy for children hospitalized with CAP in high-resource settings. Children are generally less likely than adults to be smokers, diabetic, have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or protracted immobilizing conditions (all of which may contribute to worse clinical outcomes), making it reasonable to hypothesize that 5 days of antibiotic therapy may also be sufficient for children with uncomplicated CAP [15]. If shorter courses of therapy are indeed equally effective as prolonged courses of therapy for children with CAP, this could significantly reduce antibiotic use in children across the United States and the associated downstream consequences of antibiotic overuse, including antibiotic resistance, intestinal dysbiosis, and adverse drug events.

Based on the available published data and clinical experience in the adult population, local guidelines at the Johns Hopkins Hospital have recommended 5 days of antibiotics for children hospitalized with uncomplicated CAP since 2012 [16]. Because of gradual uptake of these recommendations, variability in prescribing persists, providing a prime population to compare clinical outcomes between short and prolonged treatment durations for CAP in children. We sought to determine whether hospitalized children treated for uncomplicated CAP with short courses of antibiotics are at an increased risk of treatment failure compared with children who receive longer courses of antibiotics.

METHODS

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a retrospective cohort study of children hospitalized with CAP at The Johns Hopkins Hospital from January 2012 through December 2018. Specific International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision and Tenth Revision (ICD-9, ICD-10) codes were used to identify all children aged ≥6 months who may have had CAP. To optimize sensitivity, records were reviewed for all children with a pneumonia ICD-9/ICD-10 code anywhere on the discharge diagnosis code list [17]. Study inclusion was then limited to children with the relevant ICD-9/ICD-10 codes as well as both clinical and radiographic criteria considered to be consistent with CAP based on the adjudication of 2 infectious diseases physicians (R. G. S. and P. D. T.). Diagnostic criteria were similar to those used in prior studies of pediatric pneumonia [17, 18]. Clinical criteria included the combination of fever plus at least 1 of the following symptoms: cough, chest pain, increased work of breathing, or hypoxia. Reports from relevant imaging were reviewed by R. G. S. and P. D. T. Radiographic criteria required a radiologist’s interpretation of chest radiograph or computed tomography scan findings of an “opacity, density, infiltrate, or consolidation.”

Exclusion criteria included the following features that may be consistent with more complex illness for which it is unclear whether short-course therapy would be appropriate: the presence of a loculated or moderate to large pleural effusion or pulmonary abscess; tracheostomy dependence; healthcare-associated pneumonia, hospital-acquired pneumonia, or ventilator-associated pneumonia; intensive care unit (ICU) stay for greater than 48 hours; sickle cell disease (due to the syndromic overlap with acute chest syndrome); cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis; severe immunosuppression defined as receipt of chemotherapy, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, or solid organ transplant within the last 6 months or current neutropenia with absolute neutrophil count ≤500 cells/mm3; receipt of greater than 48 hours of antipseudomonal beta-lactams, which may be indicative of other relevant healthcare exposures or concern for unusual pathogens; or fungal or mycobacterial pneumonia. Children who received fewer than 5 or more than 14 days of antibiotic therapy were also excluded as these durations suggested an alternative diagnosis to uncomplicated CAP.

Data Collection

Demographic data, preexisting medical conditions, clinical signs and symptoms, microbiological data, antibiotic regimens, and outcomes data were collected for all eligible patients via medical record review and entered into a secure REDCap database. To maximize the comprehensiveness of pre- and post-discharge clinical data, information was reviewed from the Epic Care Everywhere Network and the Chesapeake Regional Information System for Our Patients (CRISP). The Epic Care Everywhere network includes inpatient and outpatient records from a large number of healthcare facilities in the United States. CRISP includes inpatient, outpatient, and emergency department information for children in the state of Maryland and the District of Columbia. The Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board approved the study, with a waiver of informed consent.

Exposures and Outcomes

The primary exposure was duration of antibiotic treatment, dichotomized to short-course (5–7 days) and prolonged-course (8–14 days), with day 1 being the first day antibiotics were administered in the hospital for the treatment of CAP. Antibiotic duration included antibiotics administered in the hospital and those prescribed after hospital discharge identified through review of inpatient notes, discharge summaries, discharge instructions, and discharge prescriptions. The primary outcome was treatment failure, a composite of unanticipated outpatient or emergency department visits not necessitating hospital readmission, new hospitalizations, or death occurring within 30 days after the discontinuation of antibiotic therapy. Categorization as treatment failure required independent agreement by 2 infectious diseases physicians that the new healthcare encounter was highly likely to be related to underlying bacterial pneumonia. Readmissions or outpatient visits not related to pneumonia, such as for the diagnosis of a new viral illness without prescription of antibiotics, were not included. Treatment failures that occurred prior to the completion of the initial prescribed course of therapy were also not included because they could not be reasonably attributed to the duration of therapy. For example, if a child was prescribed 10 days of amoxicillin and required readmission on day 3 of therapy, this was not included as the 10 day course had not yet been completed.

Statistical Analyses

Because treatment duration was not assigned at random, propensity scores were assigned. Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was used to account for possible selection bias regarding the prescribed treatment duration (eg, sicker patients may have been more likely to receive prolonged courses of therapy than relatively well-appearing patients). The following covariates were included in generating the propensity score: age, gender, race, asthma, hypoxia, bacteremia due to a respiratory bacterial pathogen, positive respiratory viral test, admission to the ICU, year of admission, and hospitalization longer than 7 days. Hospitalization of longer than 7 days was used as a surrogate marker for baseline medical complexity as otherwise healthy patients would not generally require hospitalizations longer than 7 days for uncomplicated pneumonia. A new weighted pseudopopulation was then created in which individuals who received a duration of therapy outside of the anticipated range based on the propensity score were given an increased weight (eg, those who received prolonged-course therapy even though the propensity score suggested a high likelihood of receiving short-course therapy) and individuals who received the expected duration of therapy were given a decreased weight.

Baseline data were compared using the Pearson χ2 test for categorical variables or the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. In the IPTW cohort, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the composite outcome of treatment failure were estimated using weighted regression, adjusting for variables with standardized mean differences greater than 10%, which indicate suboptimal balance between exposed and unexposed groups for that specific variable. A 2-sided P value <.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests. Statistical analysis was completed using Stata version 13.0.

RESULTS

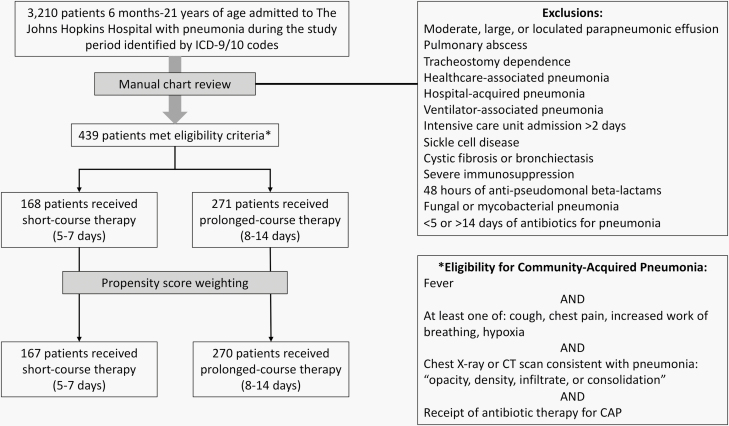

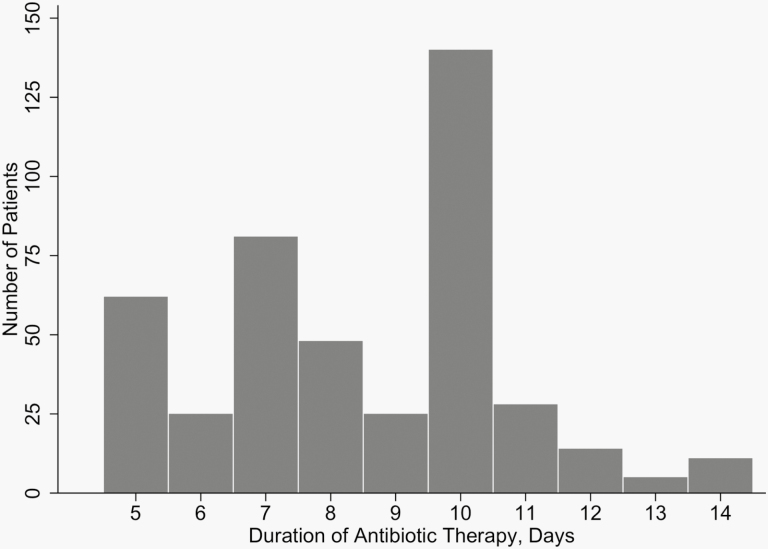

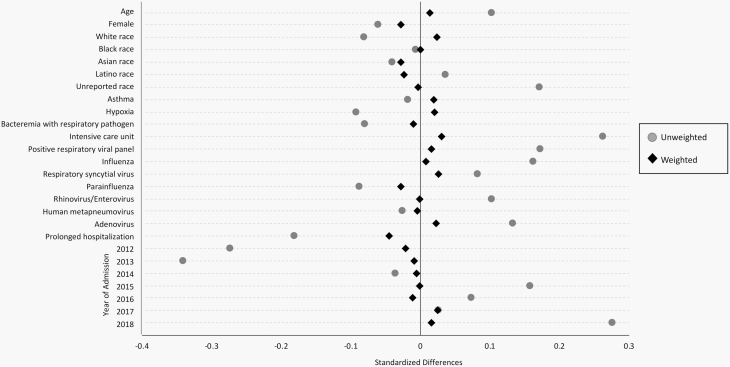

There were 3210 pediatric patients hospitalized with ICD-9/ICD-10 codes for pneumonia. After manual chart review, 2771 patients were excluded, resulting in 439 patients who met eligibility criteria. Among these, 168 (38%) patients received short-course and 271 (62%) received prolonged-course antibiotic therapy (Figure 1). The median duration of therapy was 6 days (interquartile range [IQR], 5–7) in the short-course group and 10 days (IQR, 9–10) in the prolonged-course group (Figure 2). At baseline, patients in the short-course group were more likely to have been admitted to the ICU and to have positive respiratory viral tests (Table 1). They were less likely to have a prolonged hospitalization or to be admitted during the earlier years of the study. Propensity score weighting yielded 2 well-balanced groups without any residual differences in all measured baseline characteristics (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Design of a study to compare treatment outcomes in hospitalized children receiving short-course vs prolonged-course antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated CAP. Abbreviations: CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; ICD, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision and Tenth Revision.

Figure 2.

Histogram depicting the duration of antibiotic therapy prescribed for 439 children hospitalized for uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Pediatric Patients With Uncomplicated Community-Acquired Pneumonia Hospitalized Between 2012 and 2018 at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Before and After Propensity Score Weighting, by Short-Course (5–7 days) or Prolonged-Course (8–14 days) Antibiotic Therapy

| Full Cohort | Weighted Cohort | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Short Course (n = 168) | Prolonged Course (n = 271) | P Value | Standardized Mean Differences | Short Course (n = 166.8) | Prolonged Course (n = 270.0) | P Value | Standardized Mean Differences |

| Age, median (interquartile range), y | 4 (2–8) | 4 (2–7) | .288 | 0.103 | 4 (2–8) | 4 (2–8) | .897 | 0.014 |

| Female, n (%) | 83 (49.4) | 142 (52.4) | .542 | –0.060 | 83.0 (49.8) | 138.1 (51.1) | .794 | –0.028 |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||||

| White | 58 (34.5) | 104 (38.4) | .416 | –0.080 | 62.6 (37.5) | 98.2 (36.4) | .822 | 0.024 |

| Black | 77 (45.8) | 125 (46.1) | .952 | –0.006 | 78.4 (47.0) | 126.7 (46.9) | .989 | 0.001 |

| Asian | 5 (3.0) | 10 (3.7) | .689 | –0.040 | 4.5 (2.7) | 8.7 (3.2) | .761 | –0.028 |

| Latino | 16 (9.5) | 23 (8.5) | .711 | 0.036 | 13.5 (8.1) | 23.7 (8.8) | .812 | –0.023 |

| Unreported | 12 (7.1) | 9 (3.3) | .068 | 0.172 | 7.8 (4.8) | 12.8 (4.8) | .971 | –0.003 |

| Asthma, n (%) | 84 (50.0) | 138 (50.9) | .851 | –0.018 | 87.0 (52.1) | 138.0 (51.1) | .847 | 0.020 |

| Hypoxia requiring supplemental oxygen, n (%) | 76 (45.2) | 135 (49.8) | .351 | –0.092 | 81.8 (49.1) | 129.7 (48.0) | .844 | 0.021 |

| Bacteremia with a respiratory pathogen, n (%) | 2 (1.2) | 6 (2.2) | .436 | –0.079 | 2.9 (1.7) | 5.0 (1.9) | .927 | –0.010 |

| Intensive care unit, n (%) | 59 (35.1) | 63 (23.3) | .007 | 0.263 | 48.9 (29.3) | 75.4 (27.9) | .770 | 0.031 |

| Positive respiratory viral panel, n (%) | 56 (33.3) | 69 (25.5) | .076 | 0.173 | 47.1 (28.2) | 74.3 (27.5) | .873 | 0.016 |

| Influenza | 8 (4.8) | 5 (1.9) | .080 | 0.163 | 4.4 (2.6) | 6.7 (2.5) | .924 | 0.008 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | 17 (10.1) | 21 (7.8) | .391 | 0.083 | 15.2 (9.1) | 22.6 (8.4) | .804 | 0.026 |

| Parainfluenza | 1 (0.6) | 4 (1.5) | .398 | –0.087 | 1.4 (0.8) | 3.0 (1.1) | .796 | –0.028 |

| Rhinovirus/Enterovirus | 23 (13.7) | 28 (10.3) | .286 | 0.103 | 19.6 (11.7) | 31.8 (11.8) | .988 | –0.001 |

| Human metapneumovirus | 6 (3.6) | 11 (4.1) | .797 | –0.025 | 6.4 (3.8) | 10.5 (3.9) | .969 | –0.004 |

| Adenovirus | 4 (2.4) | 2 (0.7) | .150 | 0.133 | 2.0 (1.2) | 2.5 (0.9) | .760 | 0.023 |

| Prolonged hospitalization, n (%) | 6 (3.6) | 21 (7.8) | .077 | –0.181 | 8.7 (5.3) | 17.0 (6.3) | .703 | –0.045 |

| Year of admission, n (%) | ||||||||

| 2012 | 13 (7.7) | 45 (16.6) | .008 | –0.273 | 20.9 (12.5) | 35.7 (13.2) | .860 | –0.021 |

| 2013 | 8 (4.8) | 40 (14.8) | .001 | –0.341 | 18.0 (11.0) | 18.0 (10.8) | .956 | –0.008 |

| 2014 | 18 (10.7) | 32 (11.8) | .726 | –0.035 | 18.8 (11.2) | 30.8 (11.4) | .962 | –0.005 |

| 2015 | 27 (16.1) | 29 (10.7) | .101 | 0.158 | 21.4 (12.9) | 34.8 (12.9) | .989 | –0.001 |

| 2016 | 34 (20.2) | 47 (17.3) | .447 | 0.074 | 29.7 (17.8) | 49.2 (18.2) | .910 | –0.011 |

| 2017 | 27 (16.1) | 41 (15.1) | .791 | 0.026 | 27.8 (16.7) | 42.6 (15.8) | .810 | 0.025 |

| 2018 | 41 (24.4) | 37 (13.7) | .004 | 0.276 | 30.2 (18.1) | 47.3 (17.5) | .874 | 0.016 |

Figure 3.

Standardized mean differences in baseline characteristics comparing the full unweighted cohort with the inverse probability of treated weighted cohort incorporating propensity scores.

The most commonly prescribed antibiotic class on day 1 of therapy was cephalosporins (n = 236, 54%), followed by penicillins (n = 176, 40%). The most common antibiotic class patients received to complete their antibiotic course post-discharge was penicillins (n = 309, 70%).

In the propensity-weighted cohort, 20 children (4%) experienced treatment failure within 30 days of discontinuing antibiotics (Supplementary Table 1). There was no difference in treatment failure between patients who received short-course (3%) vs prolonged-course (6%) antibiotic therapy (OR, 0.48; 95% CI, .18–1.30). Three patients (2%) in the short-course group compared with 8 patients (3%) in the prolonged-course group experienced an unplanned emergency department or outpatient visit related to CAP (OR, 0.54; 95% CI, .14–2.07) and 2 patients (2%) and 7 patients (3%) in the short- and prolonged-course groups, respectively, required hospital readmission for pneumonia (OR, 0.43; 95% CI, .11–1.74). There were no deaths in either group within 30 days of discontinuing therapy. We performed a subgroup analysis excluding all patients with any positive respiratory viral test and repeated the propensity score weighting and subsequent analysis. In this subgroup analysis including 312 patients, 14 children (4%) experienced treatment failure. There was no difference in treatment failure between those receiving short-course and prolonged-course therapy (OR, 0.45; 95% CI, .05–3.91).

DISCUSSION

In this observational study of hospitalized children with uncomplicated CAP, we found no difference in treatment failure between children treated with a short course of therapy (median 6 days) compared with longer courses of therapy. Pneumonia-related revisits and readmissions were rare in our study, occurring in approximately 4% of patients, and were similar between patients who received short-course and prolonged-course therapy. This estimate is similar to those reported in prior studies of children hospitalized for CAP [19, 20]. To our knowledge, this is the first study in the United States to investigate the clinical outcomes for hospitalized children with uncomplicated CAP receiving short-course antibiotic therapy.

Our findings are consistent with the extensive evidence from adult trials that indicate that short course therapy is safe and effective for CAP [4–13]. Limited data in children also support shorter therapy; a randomized, controlled trial that included 140 children showed no difference in outcomes for ambulatory children in Israel treated with 5 days compared with 10 days of high-dose amoxicillin [21]. A multicenter, randomized, placebo controlled clinical trial (SCOUT-CAP) is currently underway to assess outcomes in pediatric outpatients with mild CAP receiving 5 days vs 10 days of oral beta-lactam therapy [22]. Both of these studies are limited to otherwise healthy outpatients; there are no studies evaluating treatment duration for CAP in hospitalized children in the United States. Although we did not include ambulatory children with CAP in our study, if a short course of therapy is reasonable for hospitalized children with CAP, this duration should also be sufficient for children with less severe CAP who are treated as outpatients. Trials in resource-limited settings have suggested that 5 days or fewer of antibiotics are effective for the treatment of CAP in both inpatient and outpatient settings. However, these studies have used clinical rather than radiographic definitions of pneumonia, which have poor specificity, and the results may not be generalizable to children in developed countries [23–25].

The diagnosis of bacterial CAP is challenging. There is variability in the interpretation of radiographic images, and a definitive microbiologic diagnosis is rare. Children do not reliably produce sputum and blood cultures are only positive in around 2% of cases of uncomplicated CAP [26–29]. While the increased use of multiplex respiratory viral panels has increased the number of children with CAP identified with viruses [18], in practice, it is often unclear whether clinical and radiographic changes represent a purely viral pneumonia or a concomitant or subsequent bacterial process. We elected to include children with positive respiratory viral tests in our study only if they met parameters for hospitalization, were febrile, had relevant respiratory symptoms and radiographic findings suggestive of bacterial pneumonia, if the treating clinician diagnosed and treated bacterial pneumonia, and if 2 infectious diseases physicians independently agreed that bacterial pneumonia was likely. We believe that, in clinical practice, children with this constellation of signs and symptoms would generally be treated with antibiotics because of the limitations in diagnostics for bacterial CAP. To assess the possibility that our results could be biased in favor of shorter courses of therapy due to the inclusion of children with viral pneumonia who would have improved without antibiotic therapy, we performed a subgroup analysis limited to patients with negative respiratory viral tests. Treatment failure occurred in 4% of children (similar to the larger IPTW cohort) and there was no difference in treatment failure between those who received short- and prolonged-course therapy.

Evidence is mounting across a multitude of bacterial infections that “less is more” [11, 30, 31]. For pneumonia specifically, a recent study found that each excess day of antibiotic therapy was associated with a 5% increase in patient-reported adverse events [32]. Efforts to reduce potentially unnecessary antibiotic use in children are often hindered by the lack of high-quality data supporting any specific therapeutic duration for common pediatric infections and hesitance to extrapolate data from adults. Absent evidence in children, guidelines often rely on historical regimens, such as the current IDSA/PIDS pediatric CAP guidelines that acknowledge that shorter courses of treatment may be safe for CAP but recommend 10 days of therapy as the “best-studied” duration. CAP accounts for approximately 2 million outpatient visits and 124 900 hospitalizations for pneumonia in children every year [1]. Reducing the standard duration of therapy from 10 days to 5 could therefore reduce antibiotic exposure in more than 2 million children each year and prevent a substantial number of adverse events.

Our study has several limitations. First, it is a single-center study at a tertiary care center limited to 439 children and results may not be generalizable to other settings. However, we used stringent clinical and radiographic criteria for CAP. If short-course therapy was safe and effective for our population, many of whom are medically complex, there is no reason to suspect it would be less successful in healthier children. We were unable to reliably verify the duration of antibiotics administered before hospitalization, which may have underestimated treatment duration for some children, though in a subgroup of 294 patients in whom this was assessed the majority (over 70%) had not received any antibiotics prior to admission. Rigorous review of networks of electronic medical records was performed to identify inpatient, outpatient, and emergency department encounters both within and outside of the Johns Hopkins Health System. However, information from some locations is not included in Epic Care Everywhere or CRISP, for example, records from some private practice pediatricians and urgent care centers that do not use the Epic electronic health record system. Consequently, if patients sought care at these locations, some healthcare visits would have been missed. Propensity score weighting was performed to account for confounding by indication, which may have introduced unmeasured bias into the exposure categories [33]. However, residual confounding may remain as we were likely unable to account for all possible factors that may influence the decision to treat with short- or prolonged-course therapy.

Although a multicenter randomized study would provide the highest-quality evidence to evaluate the optimal duration of therapy for CAP in children, we believe that the results of our study, when combined with the abundant randomized, controlled trial data in adults, suggest that hospitalized children with uncomplicated CAP can be safely and effectively treated with approximately 5 days of antibiotics. Because CAP is one of the most common causes of hospitalization and antibiotic prescription in children, decreasing the duration of therapy could have an important public health impact.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (T32-AI052071 to R. G. S. and K23-AI127935 to P. D. T.). S. E. C. reports personal fees from Novartis, Theravance, and Basilea, outside of the submitted work.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Witt WP, Weiss AJ, Elixhauser AA.. Overview of Hospital Stays for Children in the United States, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #187. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gerber JS, Kronman MP, Ross RK, et al. Identifying targets for antimicrobial stewardship in children’s hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013; 34:1252–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS, et al. ; Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America . The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:e25–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siegel RE, Alicea M, Lee A, Blaiklock R. Comparison of 7 versus 10 days of antibiotic therapy for hospitalized patients with uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Am J Ther 1999; 6:217–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Léophonte P, Choutet P, Gaillat J, et al. [Efficacy of a ten day course of ceftriaxone compared to a shortened five day course in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized adults with risk factors]. Med Mal Infect 2002; 32:369–81. [Google Scholar]

- 6. el Moussaoui R, de Borgie CA, van den Broek P, et al. Effectiveness of discontinuing antibiotic treatment after three days versus eight days in mild to moderate-severe community acquired pneumonia: randomised, double blind study. BMJ 2006; 332:1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Uranga A, España PP, Bilbao A, et al. Duration of antibiotic treatment in community-acquired pneumonia: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176:1257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dunbar LM, Khashab MM, Kahn JB, et al. Efficacy of 750-mg, 5-day levofloxacin in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia caused by atypical pathogens. Curr Med Res Opin 2004; 20:555–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dunbar LM, Wunderink RG, Habib MP, et al. High-dose, short-course levofloxacin for community-acquired pneumonia: a new treatment paradigm. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 37:752–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. File TM Jr, Mandell LA, Tillotson G, et al. Gemifloxacin once daily for 5 days versus 7 days for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized, multicentre, double-blind study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007; 60:112–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li JZ, Winston LG, Moore DH, Bent S. Efficacy of short-course antibiotic regimens for community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Am J Med 2007; 120:783–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dimopoulos G, Matthaiou DK, Karageorgopoulos DE, et al. Short- versus long-course antibacterial therapy for community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Drugs 2008; 68:1841–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tansarli GS, Mylonakis E. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of short-course antibiotic treatments for community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 62:e00635–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 200:e45–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tamma PD, Cosgrove SE. Duration of antibiotic therapy for community-acquired pneumonia in children. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:883–4; author reply 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hsu AJ, Tamma PD. Johns Hopkins Hospital antibiotic treatment guidelines 2019–2020. Available at: intranet.insidehopkinsmedicine.org/asp/pediatric.html. Accessed November 24, 2019.

- 17. Williams DJ, Shah SS, Myers A, et al. Identifying pediatric community-acquired pneumonia hospitalizations: accuracy of administrative billing codes. JAMA Pediatr 2013; 167:851–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jain S, Williams DJ, Arnold SR, et al. ; CDC EPIC Study Team . Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:835–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Neuman MI, Hall M, Gay JC, et al. Readmissions among children previously hospitalized with pneumonia. Pediatrics 2014; 134:100–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ambroggio L, Herman H, Fain E, et al. Clinical risk factors for revisits for children with community-acquired pneumonia. Hosp Pediatr 2018; 8:718–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Greenberg D, Givon-Lavi N, Sadaka Y, et al. Short-course antibiotic treatment for community-acquired alveolar pneumonia in ambulatory children: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014; 33:136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Interventional (Clinical Trial Identifier: NCT02891915). A Phase IV Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Trial to Evaluate Short Course vs.Standard Course Outpatient Therapy of Community Acquired Pneumonia in Children (SCOUT-CAP). 2016. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02891915. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gupta S, Lodha R, Kabra SK. Antimicrobial therapy in community-acquired pneumonia in children. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2018; 20:47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shah SN, Bachur RG, Simel DL, Neuman MI. Does this child have pneumonia?: The rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA 2017; 318:462–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rambaud-Althaus C, Althaus F, Genton B, D’Acremont V. Clinical features for diagnosis of pneumonia in children younger than 5 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2015; 15:439–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Elemraid MA, Muller M, Spencer DA, et al. ; North East of England Paediatric Respiratory Infection Study Group . Accuracy of the interpretation of chest radiographs for the diagnosis of paediatric pneumonia. PLoS One 2014; 9:e106051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Neuman MI, Hall M, Lipsett SC, et al. Utility of blood culture among children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Pediatrics 2017; 140:e20171013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fritz CQ, Edwards KM, Self WH, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of bacteremic pneumonia in children. Pediatrics 2019; 144:e20183090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lipsett SC, Hall M, Ambroggio L, et al. Predictors of bacteremia in children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Hosp Pediatr 2019; 9:770–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Spellberg B. The new antibiotic mantra— “shorter is better.” JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176:1254–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wald-Dickler N, Spellberg B. Short-course antibiotic therapy-replacing Constantine units with “shorter is better.” Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:1476–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vaughn VM, Flanders SA, Snyder A, et al. Excess antibiotic treatment duration and adverse events in patients hospitalized with pneumonia: a multihospital cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2019; 171:153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Amoah J, Stuart EA, Cosgrove SE, et al. Comparing propensity score methods versus traditional regression analysis for the evaluation of observational data: a case study evaluating the treatment of gram-negative bloodstream infections [published online ahead of print February 18, 2020]. Clin Infect Dis 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.