ABSTRACT

Bloodstream infections (BSIs) caused by carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) are potentially life-threatening and an urgent threat to public health. The present study aims to clarify the characteristics of carbapenemase-encoding and virulent plasmids, and their interactions with the host bacterium. A total of 425 Kp isolates were collected from the blood of BSI patients from nine Chinese hospitals, between 2005 and 2019. Integrated epidemiological and genomic data showed that ST11 and ST307 Kp isolates were associated with nosocomial outbreak and transmission. Comparative analysis of 147 Kp genomes and 39 completely assembled chromosomes revealed extensive interruption of acrR by ISKpn26 in all Kp carbapenemase-2 (KPC-2)-producing ST11 Kp isolates, leading to activation of the AcrAB-Tolc multidrug efflux pump and a subsequent reduction in susceptibility to the last-resort antibiotic tigecycline and six other antibiotics. We described 29 KPC-2 plasmids showing diverse structures, two virulence plasmids in two KPC-2-producing Kp, and two novel multidrug-resistant (MDR)-virulent plasmids. This study revealed a multifactorial impact of KPC-2 plasmid on Kp, which may be associated with nosocomial dissemination of MDR isolates.

KEYWORDS: Bloodstream infection, carbapenem resistance, Klebsiella pneumoniae, genomics, KPC-2

Introduction

Bloodstream infections (BSIs) caused by Enterobacterales have become increasingly life-threatening, leading to a mortality rate as high as 48% [1,2]. Carbapenems remain one of the first-line of therapeutic agents for BSIs. Therefore, the emergence of carbapenemase-mediated resistance represents a serious public health threat [3]. Carbapenem resistance has been associated with increased length of hospital stay and mortality of BSI patients [4]. Carbapenemase-encoding plasmids can be transferred among various Enterobacterales via horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and disseminated in hospitals [5]. As a result, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) have been reported worldwide [6]. Klebsiella pneumoniae is a clinically important species and causes serious nosocomial infections such as septicemia, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, surgical site infection, and soft tissue infection [7]. In China, carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) accounts for about 64% of CRE infections [8]. Nonetheless, the characteristics of carbapenemase-encoding plasmids and their interactions with the host bacterium are not fully understood.

The hypervirulent variant of Kp (HvKp) has been increasingly reported in association with plasmid-mediated virulence loci rmpA/rmpA2, iuc, and iro [9,10]. The rmpA/rmpA2 genes encode proteins regulating capsule production in Kp, while iucABCDiutA and iroBCDN are responsible for the biosynthesis of siderophores aerobactin and salmochelin, respectively [11]. Carbapenem-resistant and virulence plasmid-carrying Kp is associated with excess morbidity and mortality in China [12]. The emergence and dissemination of carbapenem-resistant HvKp (CR-HvKp) are of great concern due to the combination of virulence and lack of treatment options.

Herein, we conducted integrated epidemiological and genomic analysis to infer the resistomes, virulence determinants, and the phylogenetic relationship between CRKP and CSKP isolates. We demonstrated that ISKpn26 insertion contributed to the MDR phenotypes in all the ST11-blaKPC-2 Kp by blocking the expression of AcrAB-TolC repressor acrR. Furthermore, we identified novel MDR-virulent plasmids due to ongoing recombination in Kp, representing a significant health threat in terms of both disease and treatment.

Material and methods

Bacterial isolates

We collected 425 Kp isolates from the blood of BSI patients from nine tertiary hospitals in Guangdong province, China, between 2005 and 2019 (Table S1). In cases with multiple positive blood cultures, we only included the first positive blood culture. Preliminary species identification was achieved by MALDI-TOF MS (BrukerDaltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany) and 16S rRNA sequencing. Ethical approval for this study was given by Zhongshan School of Medicine of Sun Yat-sen University under approval number 068.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing, s1-PFGE, and Southern blotting

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined for 15 antibiotics for all isolates using the agar dilution method with the exception of colistin, which used the broth dilution method following the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [13]. MIC determinations were also carried out with fixed concentration (100 μg/mL) of the efflux pump inhibitor 1-(1-naphthylmethyl)-piperazine (NMP) against 20 antibiotics among all the ST11-blaKPC-2 strains. The plasmid location of the carbapenem encoding gene was determined by S1-nuclease digestion and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (S1-PFGE), followed by Southern blotting hybridizations with a blaKPC-2 probe [14].

Galleria mellonella infection model

The virulence of target strains was determined using the wax moth (G. mellonella) larvae model [12,15]. Three doses of 1×10⁴, 1×105, 1×106 CFU each with ten worms per group were tested. 1×10⁴ CFU was used for the injection. Controls included a PBS injection group, one group receiving no dose, a non-virulent control using E. coli MG1655, and a highly-virulent control using HvKP4 as previously reported [12]. The larvae were incubated at 37°C in a darkroom and the survival rate was recorded every 12 h for seven days. The experiments were conducted in duplicate.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

The experimental procedures for qPCR were modified from a previous report [16]. The total RNA of Kp strains was extracted using the bacteria RNA Extraction Kit (Vazyme Biotech, China). Reverse transcription was performed using GoldenstarTM RT6 cDNA Synthesis Kit Ver.2 (Beijing TsingKe Biotech, China). The qPCR assay was conducted using the Bio-Rad IQ thermocycler and Master qPCR Mix-SYBR (Beijing TsingKe Biotech, China) for three biological replicates and three technical replicates. Calculation of 2-ΔΔCT using 16S rRNA as the reference was used to determine the relative transcript levels for each target gene of acrA, acrB, and acrR. The primers used to amplify each gene are listed in Table S2.

Whole-genome sequencing and genotyping

All the 72 CRKP isolates and 82 randomly selected carbapenem-susceptible Kp (CSKP) isolates from the contributing hospitals were selected for whole-genome sequencing (WGS). DNA libraries were constructed with 350-bp paired-end fragments and sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. Short-read sequence data were de novo assembled using SPAdes v3.10 [17]. For the reference strains (Table S3), eight ST11 strains and one ST23 strain from China [12], 140 ST11 strains from Europe [18], six ST11 strains from other countries in Asia [19], and six outbreak-associated ST258 strains from the USA were enrolled [20]. Furthermore, to detect the ISKpn26 insertion into acrR across public strains, all fully assembled Kp genomes were downloaded from GenBank as of 1/1/2021. The long-read MinION sequencing (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK) was used to sequence 40 Kp strains out of the 154 newly sequenced strains with a mean read length of 24 kbp. These isolates included all the 34 ST11 strains, two KPC-2-producing non-ST11 strains, and four virulence plasmid-carrying strains. De novo hybrid assembly both of short Illumina reads and long MinION reads was performed using Unicycler v0.4.3 [21], and corrected using Pilon v1.22. Plasmid sequences were confirmed by manually extracting the sequences from the assemblies to conduct a BLASTn search. The MLST and cgMLST were identified using the BIGSdb (//bigsdb.web.pasteur.fr/klebsiella/). The minimum spanning tree (MST) was constructed by GrapeTree [22]. Acquired antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and virulence genes were identified using ABRicate version 0.5 (https://github.com/tseemann/abricate) by aligning genome sequences to the ResFinder database [23] and VFDB database [24]. IS elements (https://www-isfinder.biotoul.fr), CRISPRs (https://crisprcas.i2bc.paris-saclay.fr/CrisprCasFinder/Index), PAIs (http://www.paidb.re.kr) [25], and prophages (https://phaster.ca/) [26] were identified using web-based searches. Kaptive was used to identify the whole capsule synthesis locus (K-locus) based on assembly scaffolds [27].

Phylogenetic analysis

For each de novo assembly, coding sequences were predicted using Prodigal v2.6 [28] and annotated using Prokka v1.13.3 [29]. Core genes were identified and used to build the core genome using Roary v3.12 [30] with the –e –mafft setting to create a concatenated alignment of core genomic CDS. SNP-sites (https://github.com/sanger-pathogens/snp-sites) was used to extract the core-genome SNPs (cgSNPs) [31]. The clonal strains differed by fewer than four cgSNPs [12]. Recombinogenic regions were removed with Gubbins v2.3.4 [32]. To construct a maximum likelihood phylogeny of the sequenced isolates, RAxML v8.2.10 was used with the generalized time-reversible model and a GTRGAMMA distribution to model site-specific rate variation [33]. We used iTOL [34] to visualize and edit the phylogenetic tree.

Data availability

All the 154 whole-genome sequenced data have been deposited in the NCBI database BioProject: PRJNA550041. A total of 34 blaKPC-2-carrying or virulence plasmid sequences were deposited in the GenBank database and assigned the accession numbers MT269819-MT269852.

Results

Kp is the dominant CRE species from BSI patients

A total of nine tertiary hospitals were involved in this study, with a median of 1,851 beds (IQR 1,375-2,851). Of 425 Kp isolates from patients with BSIs collected between 2005 and 2019, 72 were CRKP. The CRKP isolates were most frequently susceptible to colistin (71/72, 99%), followed by tigecycline (60/72, 83%), and amikacin (38/72, 53%) (Figure S1A). The carriage of rmtB and armA contributed to the resistance of amikacin and other aminoglycoside antibiotics, while the resistance of quinolones was mostly attributed to plasmid-mediated qnrB and qnrS1 genes. Furthermore, the MICs were significantly higher among CRKP for multiple antibiotics (Figure S1B; Table S4).

A widespread ST11-blaKPC-2 lineage in Kp

We sequenced 154 Klebsiella isolates, including 72 CRKP and 82 CSKP. Among these isolates, there were 62 distinct STs, and seven strains with novel alleles. The most prevalent STs were ST11 (n=34), ST20 (n=13), ST307 (n=8), ST37 (n=7), ST147 (n=4), and ST23 (n=4) (Table S1). Each ST identified in multiple isolates was more common in CRKP strains, while most of the singleton STs were CSKP isolates (Figure 1A). Furthermore, ST11, ST307, ST76, ST37, ST23, ST20, ST1473, ST1, ST656, and ST14 included both CRKP and CSKP isolates. According to cgMLST, ST11 and ST20 strains can be divided into a few sub-types, while all the ST307 strains were clustered into the same cgMLST type. The ST11 Kp was assigned in 34 isolates from four hospitals across eight years. Out of these 34 isolates, 31 were CRKP, of which 30 harboured blaKPC-2 with the remaining strain lacking any known carbapenemase-encoding gene. Identification of capsule synthesis loci revealed that KL47 (21/154, 14%), KL64 (16/154, 10%), KL102 (12/154, 8%), and KL28 (12/154, 8%) were the most common loci. ST11 Kp strains included 21 ST11-KL47, nine ST11-KL64, two ST11-KL111, one ST11-KL15, and one unknown capsule type (Table S1).

Figure 1.

Population structure of CRKP and CSKP isolates. (A) Minimum-spanning tree of Kp isolates based on a core-genome MLST (cgMLST). Each node within the tree represents a cgMLST type, with diameters scaled to the number of isolates belonging to that type. Join lines represent locus variants. The length of the branch between each node is proportional to the number of distinct alleles of cgMLST scheme genes that differ between the two linked nodes. The figure was colored by the group of strains and each node showed labels of STs. (B) Phylogeny of core genome SNPs in 147 KpI isolates. The classic virulence ST23-KL1 strain NTUH-K2044 (GenBank accession no. NC_012731) was used as a reference. The circle beside the nodes indicate strains of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) (solid) and carbapenem-susceptible Klebsiella pneumoniae (CSKP) (hollow). Squares indicate the carbapenemase-encoding gene to be given beside the relevant phylogeny.

By maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis derived from the core genome SNPs among the 154 Kp isolates, four phylogroups of KpI (Kp, n = 147), KpII (Klebsiella quasipneumoniae, n = 5), KpIII (Klebsiella quasivariicola, n = 1), and KpIII (Klebsiella variicola, n = 1) were observed. The population structure of the 147 KpI isolates, including 76,408 SNPs extracted from 3,617,098 bp sequences concatenated from 3,780 core genes was explored. Phylogenetic analyses revealed a deep branching and scattered population structure that was broadly classified into distinct phylogenetic lineages (Figure 1B). In contrast, the 76 CSKP isolates were unclustered and intermingled with the 71 CRKP isolates. Notably, all the ST11-CRKP isolates were clustered as the dominant phylogroup with limited nucleotide divergences among isolates belonging to the same capsular types. However, the other three ST11-CSKP isolates were grouped into two sub-lineages that were phylogenetically distal from the ST11-KL47/KL46 group. Two of these three isolates belonged to KL111, and the other isolate belonged to KL15. Upon the enrollment of reference genomes, the ST11-blaKPC-2 strains from multiple provinces in China were clustered together (Figure S2). Furthermore, the two ST11-KL111 isolates in the collection clustered together with an ST11-KL64 isolate from Singapore, two isolates from Germany, and one isolate from Spain, while the ST11-KL15 strain was clustered together with KL15 strains from Europe [18,19].

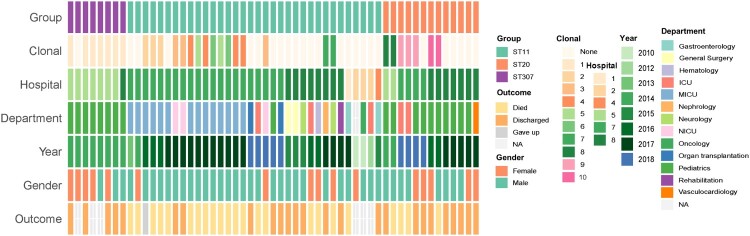

Nosocomial outbreak and transmission caused by ST11 and ST307 CRKP

Considering the strains within each phylogroup of ST11, ST20, and ST307 differed by a few cgSNPs (Figure S3), their link to a nosocomial outbreak of infection was investigated. Out of the eight neonatal infections caused by ST307 CRKP, seven infants were admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) in the same hospital (Figure 2). The duration of the infections lasted from 28 days to 63 days, and the seven ST307 CRKP were isolated within one week of admission to the hospital. (Table S1). Pairwise SNP analysis of the seven ST307 CRKP showed that six of them differed by fewer than 4 cgSNPs, indicating that these strains originated from a single clone. The remaining ST307 strain from this hospital exhibited a difference of 10–12 cgSNPs compared to the other six isolates. The integrated genomic and epidemiological analysis suggested that ST307 CRKP strains were linked to a nosocomial outbreak of infection. The 13 ST20 Kp strains were collected between 2014 and 2018 across three different hospitals. The isolates from the same hospital had fewer cgSNPs differences and multiple clones were identified across the isolates (Figure 2). Furthermore, 21 out of the 34 ST11 Kp isolates were collected from the same hospital from 2013 to 2018 and the majority of the patients were admitted to the MICU (67%, 14/21) (Figure 2; Table S1). 14 out of the 21 strains were related to multiple clones with cgSNPs ≤ 4. However, since ST11 Kp is prevalent in China, and given the limited strain numbers and time lag between patient presentations, both nosocomial transmission events and independent introductions in each hospital were possible.

Figure 2.

Epidemiological data and clonal identification of ST11, ST307, and ST20 Kp isolates. All the ST11 (n = 34), ST20 (n = 13), and ST307 (n = 8) isolates were enrolled and each block represented a strain which was ordered by the sampling date from the same hospital within each group of STs. For the clonal panel, clonal strains were indicated when the difference of core-genome SNPs fewer than four. Each number in the legend represented one type of collections of clonal strains, and the strain marked the same number/color represented that they are clonal-related strains.

Extensive ISKpn26 insertion within the AcrAB-TolC repressor acrR contributes to the multidrug-resistant (MDR) phenotypes in ST11-blaKPC-2 Kp

Comparative analysis of 39 completely assembled Kp genomes revealed extensive conservation of gene content between ST11-blaKPC-2 and ST11 Kp without blaKPC-2 (Figure 3A). However, three additional segments of ∼28-kbp, ∼7,600-bp, and ∼5,500-bp were exclusively observed in the three ST11 isolates that lacked blaKPC-2 (Table S5). Furthermore, all ST11 isolates carried a 52-kbp intact prophage sequence named PHAGE_Salmon_SEN34, which was absent from 6 non-ST11 genomes.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of mobile genetic elements integrated in ST11-blaKPC-2 chromosome. (A) Circular genetic map of 39 completely assembled Kp genomes. The color intensity in each ring represents the BLASTn match identity to the Kp strain BSI130 genome. The distribution of prophage sequences, insertion sequence (IS) elements, virulence genes, pathogenicity island (PAI)-like sequences, and CRISPR sequences were mapped to the BSI130 chromosome. The legend of each ring indicates the strain ID, year of isolation, sequence type (ST), carbapenemase-encoding gene, plasmid-mediated virulence gene (VR). (B) Schematic presentation of ISKpn26 insertion into the acrR gene in Kp genomes. This represented three types of ISKpn26 insertion, each identified in different Kp isolates. All the 39 newly assembled Kp genomes were used to clarify the profile of ISKpn26 insertion. Homologous sequences (representing >99% sequence identity) are indicated by light gray shading. Arrows show the direction of transcription of open reading frames (ORFs). (C) The relative mRNA expression of acrR and acrAB. acrR+ represents three ST11 Kp harbouring intact acrR without ISKpn26 insertion; acrR- represents three ST11 Kp carrying truncated acrR by ISKpn26. Data represent the mean ± SE. (D) The number of ISKpn26 in the 39 newly assembled Kp chromosomes. The four groups represent Kp strains harbouring ISKpn26 which was located in different plasmids. Group A represents no ISKpn26 found either in KPC-2 plasmid or other plasmids (n = 7); Group B represents ISKpn26 found only in non-blaKPC-2-carrying plasmids (n = 7); Group C represents ISKpn26 found both in KPC-2 plasmid and other plasmids (n = 12); Group D represents ISKpn26 found only in KPC-2 plasmid (n = 13). (t-test, *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001).

We further determined the presence of IS elements in the chromosome for those genomes. Notably, we found that 30 out of 39 genomes had an insertion of ISKpn26 (1,196 bp, IS5 family) within the acrR gene, all of which were ST11-blaKPC-2 strains. Among the 30 ISKpn26 sequences, ten SNPs were detected and consisted of G+173A, T+176C, A+180G, C+181 T, C+182G, C+184A, T+185A, G+647A, G+698 T, and G+950A. In each strain, the ISKpn26 sequence within acrR was identical to the ISKpn26 located in the blaKPC-2-carrying plasmid. ISKpn26 insertion was located in the target site of a 4-bp (CTAG) direct repeat (DR) at +276 bp of acrR, with a target site duplication producing another copy of DR at the boundaries of ISKpn26 after its transposition (Figure 3B). Besides the 29 strains with the consistent insertion of ISKpn26 forming two ΔacrR fragments, one isolate harboured an additional insertion causing the loss of the first 276-bp sequence of acrR and the duplicated DR. Although the remaining ST11-blaKPC-2 isolate lacked ISKpn26 within acrR, it harboured two copies of DR and a 4-bp (GTTC) sequence belonging to ISKpn26, indicating that ISKpn26 had been inserted in acrR. By searching all the additional newly assembled Kp genomes (n = 117), ISKpn26 insertion in acrR was not detected. By searching all the 669 fully assembled Kp genomes in the public database, the intact ISKpn26 insertion in acrR was found in 85 isolates. The vast majority of these isolates were collected in China and 80 were ST11 strains (Table S6). qPCR showed that ISKpn26 interruption blocked the expression of acrR (P = 0.032, t-test), while the relative expression of acrB was enhanced by a 12.6-fold change (P = 0.002, t-test) (Figure 3C). The susceptibility testing among all the ST11-blaKPC-2 isolates revealed significantly reduced MICs for multiple antimicrobial agents; namely tigecycline, ciprofloxacin, colistin, piperacillin-tazobactam, nitrofurantoin, ofloxacin, and chloramphenicol in the presence of the efflux pump inhibitor NMP (P < 0.05) (Figure 4). Next integration of ISKpn26 into other regions of the chromosome was assessed. It was found that the strains which harboured plasmids with both ISKpn26 and blaKPC-2, had a significantly higher mean number of ISKpn26 in the chromosome (15 ± 0.4 vs. 6 ± 2.4, P < 0.001, t-test) (Figure 3D).

Figure 4.

Antimicrobial resistance profile of 20 antimicrobial agents among 30 ST11-blaKPC-2 Kp before and after adding NMP. The MICs were log-transformed for statistical analysis. NMP: 1-(1-naphthylmethyl)-piperazine (NMP). CIP: ciprofloxacin; TGC: tigecycline; PZT: piperacillin-tazobactam; NIT: nitrofurantoin; CT: colistin; OFL: ofloxacin; CHL: chloramphenicol; CFX: cefoxitin; CAZ: ceftazidime; NAL: nalidixic acid; SXT: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; MEM: meropenem; GEN: gentamicin; AMK: amikacin; IMP: imipenem; CTX: cefotaxime; ATM: aztreonam; AMP: Ampicillin; ETP: ertapenem; FOS: fosfomycin. Dashed lines represented resistance breakpoints (t-test, *P<0.05; ***P<0.001).

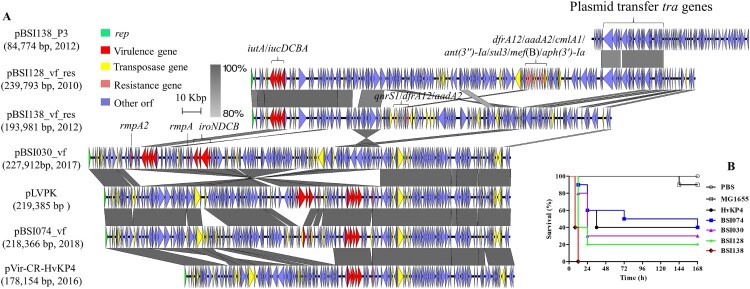

MDR-virulent plasmids and virulence plasmids in blaKPC-2-harbouring Kp

We further detected the virulence plasmid-harbouring genes of rmpA (hypermucoidy) (CRKP=4; CSKP=14), rmpA2 (hypermucoidy) (CRKP=0; CSKP=1), iucABCD/iutA (aerobactin) (CRKP=4; CSKP=15), and iroBCDN (salmochelin) (CRKP=1; CSKP=14). Of the four CRKP strains harbouring plasmid-mediated virulence genes, two carried blaKPC-2 and two carried blaNDM-1. Complete virulence plasmid sequences for the two KPC-2-producing strains and two earlier CSKP strains (Figure 5A) were obtained. Notably, pBSI128_vf_res (239,793 bp) and pBSI138_vf_res (193,981 bp), cultured from patients in 2010 and 2012 at the same hospital, carried both virulence factors (iucABCD and iutA) and multiple ARGs (Figure 5A). These two plasmids had IncFIB and IncFII replicons and displayed >90% sequence identity with 60% coverage. In the two plasmids, iuc and iutA were associated with an ISEc45 downstream. They shared sequence identities across the virulence module, while significant differences were observed in the MDR region. The 14,922-bp MDR region in pBSI128_vf_res contained genes conferring resistance to trimethoprim, chloramphenicol, aminoglycoside, and macrolides. Furthermore, the pBSI138_P3 from Kp strain BSI138 shared two homologous regions with pBSI128_vf_res, which covered the tra loci, one 21,497 bp in length with 97% identity and another 9,397 bp in length with 94% identity. A BLASTn search did not find homologous plasmids to pBSI138_vf_res and pBSI128_vf_res (coverage <60%), with the exception of p130411-38618_1 (GenBank: MK649826) from a Kp isolate collected in 2011 in Vietnam [35] (identity >99%, coverage 62%).

Figure 5.

Virulence plasmids and their relevance with pathogenicity. (A) Detailed comparison of linear maps of virulence plasmids in Kp isolates. Two classical virulence plasmids of pLVPK (AY378100) and pVir-CR-HvKP4 (MF437313) were used as references. Dark gray shading indicates homologous regions. Arrows show the direction of transcription of open reading frames (ORFs). Genes, mobile elements, and other features are colored based on function classification. The virulence and resistance genes are marked. The figure is drawn to scale. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for seven-day mortality following Kp infections. Each group had 10 larvae in the G. mellonella infection model. Controls included a PBS injection group, a non-virulent control using E. coli MG1655, and a highly-virulent control HvKP4. The survival curve was created using GraphPad Prism.

Among the two KPC-2-producing strains ST23 BSI030 and ST11 BSI074, pBSI030_vf harbours the virulence genes of iuc, iro, iutA, rmpA and rmpA2. This plasmid backbone showed similarity to the classic virulence plasmid pLVPK (>99% nucleotide identity, 93% coverage) but with multiple inverted regions (Figure 5A). Furthermore, pBSI030_vf carried an 11,716-bp fragment containing HigB/HigA toxin/antitoxin system that was not present in pLVPK. The pBSI074_vf backbone was similar to pBSI030_vf (>99% identity, 97% coverage) and pLVPK (>99% identity, 90% coverage) but lacked iroBCD and rmpA2 genes, and rmpA and iroN genes were truncated by ISKpn26. Rearrangement of multiple IS elements in pBSI074_vf also resulted in the difference in the recently identified pVir-CR-HvKP4 in China (Figure 5A). Using the G. mellonella infection model, we demonstrated that all four strains harbouring virulence plasmids are highly virulent compared with the hypervirulent strain HvKP4 (Figure 5B).

The highly diverse structure of blaKPC-2-carrying plasmids

Among the 72 CRKP isolates, blaKPC-2 was the predominant type and detected in 32 isolates. S1-PFGE and Southern blotting hybridization indicated that blaKPC-2 genes were located on plasmids with diverse sizes in the 32 Kp isolates (Figure S4). To further clarify the features of blaKPC-2-carrying plasmids, 29 complete plasmid sequences were obtained from the 32 blaKPC-2-harbouring Kp (ST11 = 30; ST23 = 1; ST1 = 1). The sizes of plasmids ranged from 92,603 bp for pBSI011-KPC2 to 171,483 bp for pBSI057-KPC2 (Figure 6). Almost all (28/29) of the plasmids carried at least one copy of the pilin-coding gene traA. The blaKPC-2 gene was surrounded by a 4,655-bp sequence consisting of IS26 (820 bp)-tnpR (402 bp)-ISKpn27 (1,080 bp)-blaKPC-2 (882 bp)-ΔISKpn6 (1,033 bp) across all the sequenced plasmids. No other resistance genes were detected in five plasmids, while catA2, blaTEM-1B, rmtB, blaCTX-M-65, fosA3, and blaSHV-12 were integrated into the other plasmids (Figure S5). These genes were found in concomitant plasmids within the blaKPC-2-harbouring isolates, indicating that blaKPC-2-carrying plasmids are plastic and can capture ARGs from adjacent plasmids in the same host.

Figure 6.

The highly diverse structure of blaKPC-2-carrying plasmids in Kp. The figure represents major structural features of 29 completed blaKPC-2-carrying plasmids. ORFs are portrayed by arrows to indicate the direction of transcription and colored based on their predicted gene functions. Dark gray shading indicates homologous regions. The name of each plasmid and related year of isolation are highlighted. The figure is drawn to scale.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are thankful for Prof. Rong Zhang to provide the Kp strain HvKP4.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 82061128001, 81722030, 81830103, 81902123), National Key Research and Development Program (grant number 2017ZX10302301), Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (grant number 2017A030306012), Project of high-level health teams of Zhuhai at 2018 (The Innovation Team for Antimicrobial Resistance and Clinical Infection), 111 Project (grant number B12003), Open project of Key Laboratory of Tropical Disease Control (Sun Yat-sen University), Ministry of Education (grant number 2018kfkt01/02), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant number 2019M653192), Science, Technology, and Innovation Commission of Shenzhen Municipality (JCYJ20190807151601699).

Discussion

The Kp isolates have evolved separately in distinct clonal groups, including the virulent clonal ST23, and the MDR clonal ST258 and ST11 [36]. It is important to identify carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent Kp and to understand the risk of transmission. Among the Kp strains from BSI patients, potentially novel, differently sized virulence plasmids associated with high mortality of G. mellonella were identified. Two KPC-2-producing strains (ST11 BSI074 and ST23 BSI030) harbouring virulence plasmids were detected, and pBSI074_vf shared high similarity to pBSI030_vf. Considering that a virulence plasmid was rarely found in ST11 strains but was prevalent in ST23 isolates in our collection (100%) and other sources [10], pBSI074_vf was likely acquired from ST23 isolates. Notably, two MDR-virulent plasmids harbouring virulence markers iucABCDiutA plus multiple ARGs were identified. These plasmids also possess plasmid transfer-associated genes that probably facilitate their dissemination. MDR-virulent plasmids were rare but an increasing number of studies have reported such strains in the past few years [35,37,38,39]. The emergence and spread of MDR-virulent plasmids as a result of ongoing recombination is a significant potential health threat in terms of both disease and treatment.

ST11 Kp is the dominant sequence type in China [12], which was distinct from the prevalence in other countries in South and Southeast Asia [35]. In Europe, ST11 Kp was accounting for approximately 10% of the clinical Kp population, and blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-48 are the dominant genes in ST11 CRKP [18]. In this study, the extensively disseminated ST11-blaKPC-2 Kp was continuously identified in BSIs patients. The nosocomial transmission has been detected in some hospitals. The blaKPC-2-carrying plasmids are highly diverse, and ongoing integration of additional resistance genes has been identified as causing the transmission of MDR plasmids. Another finding is the extensive integration of ISKpn26 into acrR, which was observed in all the ST11-blaKPC-2 genomes, leading to the deactivation of acrR and increased expression of acrB. ISKpn26-like insertion in mgrB has been found in ST258 Kp which was responsible for colistin resistance [40]. ISKpn26 insertion in acrR has only been reported in an ST11-blaKPC-2 Kp in Taiwan [41]. We found that the intact ISKpn26 insertion in acrR mostly happened in strains from Asia. Furthermore, a replicative-like transposition [42] produced 14–18 copies of ISKpn26 in the chromosome. A strong link between KPC-2 plasmid-located ISKpn26 and ISKpn26 insertion into acrR indicates that blaKPC-2 plasmid is the reservoir for ISKpn26. The acrR gene is the local repressor of resistance-nodulation-division (RND) efflux pump AcrAB-TolC, which is critical to acquire antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [43,44], and is involved in virulence [45]. We found that the presence of NMP increased the susceptibility of multiple antibiotics, including the last-resort antibiotic tigecycline to treat CRE infections. These data demonstrated that ISKpn26 insertion contributed to the MDR phenotypes in ST11-blaKPC-2 Kp by blocking the expression of AcrAB-TolC repressor acrR. The interaction between the blaKPC-2 plasmid and the ST11 Kp host may, therefore, facilitate nosocomial dissemination and transfer of AMR.

In conclusion, our results revealed a widespread ST11-blaKPC-2 lineage of CRKP from BSI patients in China. In addition to contributing to AMR spread, KPC-2 plasmids can further interact with the host and alter some host-dependent social traits, such as the provision of ISKpn26 to insert into acrR, and therefore, up-regulate AcrAB-TolC multidrug efflux pump, leading to the increased MDR phenotypes of the host bacterium. Furthermore, we identified novel MDR-virulent plasmids due to ongoing recombination in Kp; therefore, representing a significant health threat in terms of both disease and treatment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Ben-David D, Kordevani R, Keller N, et al. Outcome of carbapenem resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections. Clin Microbiol Infec. 2012;18(1):54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chetcuti Zammit S, Azzopardi N, Sant J.. Mortality risk score for Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteraemia. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(6):571–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y.. Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae A potential threat. Jama-J Am Med Assoc. 2008;300(24):2911–2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewardson AJ, Marimuthu K, Sengupta S, et al. Effect of carbapenem resistance on outcomes of bloodstream infection caused by Enterobacteriaceae in low-income and middle-income countries (PANORAMA): a multinational prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(6):601–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conlan S, Thomas PJ, Deming C, et al. Single-molecule sequencing to track plasmid diversity of hospital-associated carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:254ra126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordmann P, Naas T, Poirel L.. Global spread of carbapenemase-producing enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(10):1791–1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee W-H, Choi H-I, Hong S-W, et al. Vaccination with Klebsiella pneumoniae-derived extracellular vesicles protects against bacteria-induced lethality via both humoral and cellular immunity. Exp mol med. 2015;47(9):e183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang R, Liu L, Zhou H, et al. Nationwide surveillance of Clinical carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) strains in China. EBioMedicine. 2017;19:98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen YT, Chang HY, Lai YC, et al. Sequencing and analysis of the large virulence plasmid pLVPK of Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43. Gene. 2004;337:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam MMC, Wyres KL, Duchene S, et al. Population genomics of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae clonal-group 23 reveals early emergence and rapid global dissemination. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russo TA, Marr CM.. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32(3):e00001–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu D, Dong N, Zheng Z, et al. A fatal outbreak of ST11 carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Chinese hospital: a molecular epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CLSI. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute . (2018). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 28rd informational supplement. M100-S28. CLSI, Wayne, PA.

- 14.Sirichote P, Hasman H, Pulsrikarn C, et al. Molecular characterization of extended-spectrum cephalosporinase-producing Salmonella enterica serovar choleraesuis isolates from patients in Thailand and Denmark. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(3):883–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLaughlin MM, Advincula MR, Malczynski M, et al. Quantifying the clinical virulence of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing carbapenemase Klebsiella pneumoniae with a Galleria mellonella model and a pilot study to translate to patient outcomes. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaze WH, Zhang L, Abdouslam NA, et al. Impacts of anthropogenic activity on the ecology of class 1 integrons and integron-associated genes in the environment. ISME J. 2011;5(8):1253–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(5):455–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.David S, Reuter S, Harris SR, et al. Epidemic of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Europe is driven by nosocomial spread. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:1919–1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holt KE, Wertheim H, Zadoks RN, et al. Genomic analysis of diversity, population structure, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae, an urgent threat to public health. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(27):E3574–E3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snitkin ES, Zelazny AM, Thomas PJ, et al. Tracking a hospital outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with whole-genome sequencing. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:148ra116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, et al. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(6):e1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou Z, McCann A, Litrup E, et al. Neutral genomic microevolution of a recently emerged pathogen, Salmonella enterica serovar agona. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(4):e1003471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(11):2640–2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L, Zheng D, Liu B, et al. VFDB 2016: hierarchical and refined dataset for big data analysis-10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D694–D697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoon SH, Park YK, Kim JF.. PAIDB v2.0: exploration and analysis of pathogenicity and resistance islands. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D624–D630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arndt D, Grant JR, Marcu A, et al. PHASTER: a better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W16–W21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wyres KL, Wick RR, Gorrie C, et al. Identification of Klebsiella capsule synthesis loci from whole genome data. Microb Genom. 2016;2(12):e000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(14):2068–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page AJ, Cummins CA, Hunt M, et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(22):3691–3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Page AJ, Taylor B, Delaney AJ, et al. SNP-sites: rapid efficient extraction of SNPs from multi-FASTA alignments. Microb Genom. 2016;2(4):e000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Croucher NJ, Page AJ, Connor TR, et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(3):e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(21):2688–2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Letunic I, Bork P.. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W242–W245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wyres KL, Nguyen TNT, Lam MMC, et al. Genomic surveillance for hypervirulence and multi-drug resistance in invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae from South and Southeast Asia. Genome Med. 2020;12(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bialek-Davenet S, Criscuolo A, Ailloud F, et al. Genomic definition of hypervirulent and multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clonal groups. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(11):1812–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dong N, Lin D, Zhang R, et al. Carriage of blaKPC-2 by a virulence plasmid in hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(12):3317–3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen D, Ma G, Li C, et al. Emergence of a multidrug-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 23 strain with a rare blaCTX-M-24-harboring virulence plasmid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63(3):e02273–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lam MMC, Wyres KL, Wick RR, et al. Convergence of virulence and MDR in a single plasmid vector in MDR Klebsiella pneumoniae ST15. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74(5):1218–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pitt ME, Elliott AG, Cao MD, et al. Multifactorial chromosomal variants regulate polymyxin resistance in extensively drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microb Genom. 2018;4(3):e000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang YH, Chou SH, Liang SW, et al. Emergence of an XDR and carbapenemase-producing hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae strain in Taiwan. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(8):2039–2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He S, Hickman AB, Varani AM, et al. Insertion sequence IS26 reorganizes plasmids in clinically isolated multidrug-resistant bacteria by replicative transposition. mBio. 2015;6(3):e00762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nolivos S, Cayron J, Dedieu A, et al. Role of AcrAB-TolC multidrug efflux pump in drug-resistance acquisition by plasmid transfer. Science. 2019;364(6442):778–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernandez L, Hancock RE.. Adaptive and mutational resistance: role of porins and efflux pumps in drug resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25(4):661–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Padilla E, Llobet E, Domenech-Sanchez A, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae AcrAB efflux pump contributes to antimicrobial resistance and virulence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(1):177–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the 154 whole-genome sequenced data have been deposited in the NCBI database BioProject: PRJNA550041. A total of 34 blaKPC-2-carrying or virulence plasmid sequences were deposited in the GenBank database and assigned the accession numbers MT269819-MT269852.