Abstract

The central role of cupric superoxide intermediates proposed in hormone and neurotransmitter biosynthesis by noncoupled binuclear copper monooxygenases like dopamine-β-monooxygenase has drawn significant attention to the unusual methionine ligation of the CuM (“CuB”) active site characteristic of this class of enzymes. The copper–sulfur interaction has proven critical for turnover, raising still-unresolved questions concerning Nature’s selection of an oxidizable Met residue to facilitate C–H oxygenation. We describe herein a model for CuM, [(TMGN3S)CuI]+ ([1]+), and its O2-bound analog [(TMGN3S)CuII(O2•−)]+ ([1·O2]+). The latter is the first reported cupric superoxide with an experimentally proven Cu–S bond which also possesses demonstrated hydrogen atom abstraction (HAA) reactivity. Introduction of O2 to a precooled solution of the cuprous precursor [1]B(C6F5)4 (−135 °C, 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF)) reversibly forms [1·O2]B(C6F5)4 (UV/vis spectroscopy: λmax 442, 642, 742 nm). Resonance Raman studies (413 nm) using 16O2 [18O2] corroborated the identity of [1·O2]+ by revealing Cu–O (446 [425] cm−1) and O–O (1105 [1042] cm−1) stretches, and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy showed a Cu–S interatomic distance of 2.55 Å. HAA reactivity between [1·O2]+ and TEMPO–H proceeds rapidly (1.28 × 10−1 M−1 s−1, −135 °C, 2-MeTHF) with a primary kinetic isotope effect of kH/kD = 5.4. Comparisons of the O2-binding behavior and redox activity of [1]+ vs [2]+, the latter a close analog of [1]+ but with all N atom ligation (i.e., N3S vs N4), are presented.

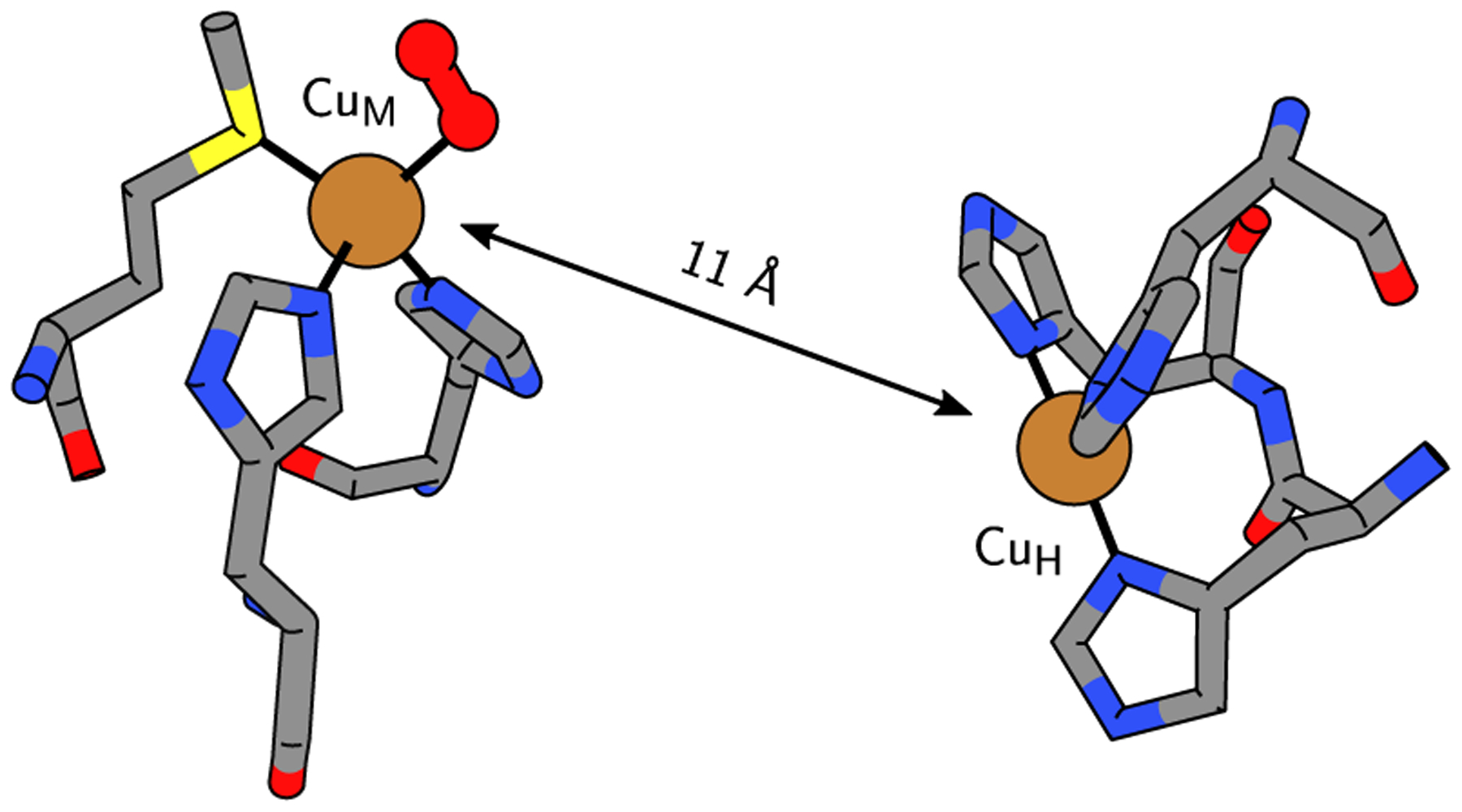

The noncoupled binuclear (NCBN) copper monooxygenase family of peptidylglycine-α-hydroxylating monooxygenase (PHM), dopamine-β-monooxygenase (DβM), and tyramine-β-monooxygenase (TβM) is crucial to hormone and neurotransmitter biosynthesis. This family is characterized by two distant (11–14 Å) copper centers CuM (CuB) and CuH (CuA) (Figure 1). The former has a MetHis2 coordination sphere and is thought to play the major role in O2 activation and substrate-binding, while the latter has His3 coordination and behaves as an electron relay.1–4 After years of study,2,5–10 experimental and computational evidence have mostly converged on an end-on (η1) superoxide CuMII(O2•−) intermediate hypothesized as the active species in substrate hydrogen atom abstraction (HAA), initiating C–H hydroxylation.11 Such an intermediate is distinct from other proposed cupric superoxides12–14 due to the presence of an oxidizable methionine at CuM. In fact, this Met has proven critical to turnover, as mutants lacking sulfur ligation (Met, Cys) have been inactive.15

Figure 1.

A depiction (PDB: 1SDW)2 of the copper centers of PHM, the O2-binding CuM, and the electron relay CuH.

The criticality of the methionine remains unexplained16–19 prompting model system investigations. These have demonstrated the influences of denticity,4,20–25 electron richness,26,27 steric modulation,28,29 coordination geometry,30 temperature, solvent,31 and hydrogen bonding32,33 on electronic structure and reactivity.

Despite these insights, we still lack a CuIIO2•− model with a clear CuII–S interaction and its corresponding HAA reactivity. Although thioether-containing tridentate or tetradentate ligand-copper models have been investigated,34–41 many synthetic attempts rather form binuclear cupric peroxides,37,42–44 and none exhibit substrate oxidative reactivity. Our recent report45 using a modified TMPA ligand26 succeeded in observation of a mononuclear CuIIO2•− in the presence of a thioether; however, direct evidence of the Cu–S interaction by (EXAFS) spectroscopy eluded us. Furthermore, the extreme instability of this complex prevented rigorous spectroscopic and reactivity studies, as it rapidly formed the more stable trans-peroxide.

We now report that the TMGN3S ligand39 supports a cupric superoxide, [(TMGN3S)CuIIO2•−]+ ([1·O2]+), with a demonstrable CuII–S interaction (Scheme 1) and HAA reactivity. Resonance Raman (rR) studies confirmed the identity of ([1·O2]+) as a superoxide complex, and EXAFS studies demonstrate the first irrefutable Cu–S bond in a CuO2 complex. Beyond the relevance of [1·O2]+ as an NCBN structural model with Cu–Sthioether ligation, it is the first functional mimic of the CuM active site.

Scheme 1.

Compound [1]B(C6F5)4 Reversibly Binds O2 upon Cooling to −135 °C in 2-MeTHF, Forming [1·O2]B(C6F5)4

The O2-chemistry of [1]OTf was previously interrogated, but no superoxide formation was observed in acetone at −76 °C.39 However, the success of the similar TMG3tren ligand in supporting a stabilized cupric superoxide [2·O2]+28,46–48 encouraged our exploration of broader experimental conditions for the −CH2CH2SEt ligand analog, [1·O2]+ (Scheme 1). We sought lower temperatures by a switch from acetone to 2-MeTHF, also requiring a switch to tetrakis(pentafluorophenyl)borate, B(C6F5)4−, as the counteranion. Combination of TMGN3S with [CuI(CH3CN)4](C6F5)4 in 2-MeTHF provided [1]B(C6F5)4 (87% yield) following workup and recrystallization. Our present single crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD) study (see Section 2 in the Supporting Information (SI)) revealed a monomeric species with a normal Cu–S distance of 2.2709(5) Å (Figure 2a).37,39,42–44 [1]B(C6F5)4 possesses unremarkable Cu–N distances of 2.0362(15), 2.0436(15), and 2.1987(14) Å. This four-coordinate, distorted trigonal pyramidal geometry presents an open fifth coordination site for further ligand binding.

Figure 2.

(a) Displacement ellipsoid plot (50% probability level) of [1]B(C6F5)4 at 110(2) K with a Cu–S distance of 2.2709(5) Å. Hydrogen atoms and counterions have been omitted for clarity. (b) Structure of [1·O2]+ from density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Selected interatomic distances [Å] and angles [deg]: Cu–S 2.50, Cu–O 1.99, O–O 1.29; Cu–O–O 113.0.

Exposure of a precooled solution of [1]B(C6F5)4 (0.39 mM, 2-MeTHF, −135 °C) to excess O2 evinced the brilliant green color of [1·O2]B(C6F5)4. UV/vis spectroscopic monitoring (Figures S1 and S2) revealed growth of features at λmax 442 nm (ε 3700 M−1 cm−1), 642 nm (ε 1525 M−1 cm−1), and 742 nm (ε 1675 M−1 cm−1),49 matching well with those of [2·O2]+.48 Quantification was achieved by variable temperature O2 binding studies (Figures 3a and 3b), which revealed that the earlier report of [1]+ likely missed superoxide formation because [1·O2]+ only appreciably forms below −90 °C. Interestingly, the difference in temperature profiles of O2 binding between [1]+ and the N4-analog [2]+ was stark (Figures 3b and S3) and could be fit to show dioxygen binding by [1]+ was more endergonic by ΔΔH[1]–[2] = +3.2 kcal/mol and ΔΔS[1]–[2] = +3.7 cal/mol·K (see Section 4 in the SI). Cyclic voltammetry showed similar results. Solutions of both [1]B(C6F5)4 and [2]B(C6F5)4 (0.1 mM, 17:3 2-MeTHF/acetone, 0.1 M TBAPF6, 25 °C) exhibited quasi-reversible features and had half-wave potentials at 150 and −126 mV, respectively (Figure 3c; see Figure S4 for CV data in CH3CN). This corresponds to a 6 kcal/mol difference between CuII/CuI reduction potentials, in qualitative agreement with the O2 binding behavior.

Figure 3.

(a) UV/vis spectra show [1]B(C6F5)4 solutions (0.39 mM, 2-MeTHF) under an O2 atmosphere to reversibly form [1·O2]B(C6F5)4. (b) O2 binding curves (UV/vis, 740 nm) and fits (see the SI). (c) CVs of [1]B(C6F5)4 and [2]B(C6F5)4 (~1 mM, 17:3 2-MeTHF/Acetone, 0.1 M TBAPF6). (d) Resonance Raman spectra (413 nm, 20 mW) of the 16O and 18O samples, along with a difference spectrum (gray). (e) Cu K-edge XAS spectra of [1]B(C6F5)4 (green) and [1·O2]B(C6F5)4 (orange) with the expanded pre-edge region (inset). (f) Cu K-edge EXAFS data (inset) and nonphase-shift-corrected FT for [1·O2]B(C6F5)4 (data, solid orange; fits, dotted black).

The presence of a cupric superoxide moiety within [1·O2]B(C6F5)4 was confirmed by resonance Raman (rR) spectroscopic studies on a frozen 2-MeTHF sample (Figure 3d). Laser excitation at 413 nm revealed resonantly enhanced bands at 446 and 1105 cm−1 that shifted upon 18O2 labeling (425, 1042 cm−1, respectively). The 446 cm−1 band can be assigned as the Cu–O stretch and the 1105 cm−1 band as the superoxide O–O stretch in line with other η1-end-on-bound superoxides, including [2·O2]+.26,32,33,45,50–52

Importantly, this assignment left unresolved the question of a CuII–S interaction in [1·O2]+. To address this, and as previously successfully applied,41,42 Cu K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) studies were undertaken on frozen 2-MeTHF solutions of both [1]B(C6F5)4 and [1·O2]B(C6F5)4 (Figure 3e). An electric dipole-forbidden quadrupole-allowed 1s–3d transition pre-edge feature was observed for [1·O2]+ at ~8979 eV, indicative of significant CuII character.53 In contrast, [1]+ shows an intense feature at ~8984 eV from the electric dipole-allowed 1s–4p transition expected of CuI complexes.54 The absence of this feature in [1·O2]+ demonstrates little-to-no residual [1]+.

The Cu K-edge EXAFS data and corresponding Fourier transforms (FT) provided geometrical insight (Figure 3f). Compared to [1]+, [1·O2]+ exhibits shifts in the EXAFS beat pattern to higher k and in the first-shell FT peak to lower R (SI Figure S5b), suggesting a general contraction in the first coordination sphere of [1·O2]+. Careful fitting revealed this contraction was not uniform (SI Table S2): [1]+ had 3 Cu–N/O at 2.01 Å and 1 Cu–S at 2.26 Å, while [1·O2]+ had 4 Cu–N/O at 1.98 Å and 1 Cu–S at 2.55 Å. Thus, the Cu–S bond lengthened upon O2 binding. The distances agree with XRD of [1]B(C6F5)4 and related copper–dialkylthioether distances39,55,56 in the Cambridge Structural Database (CuI⋯S 2.24–2.43 Å, CuII⋯S 2.30–2.74 Å).57 The relatively high σ2 for the Cu–S path of [1·O2]+ (SI Table S2) reflects higher disorder, reasonable considering the fairly long interatomic distance. The Cu–S contributions were essential to achieve good fits; fits for [1·O2]+ replacing the Cu–S interaction with Cu⋯C or Cu⋯O scatterers were poorer, most noticeably in the ~2 Å FT feature and the larger errors (Figure S5e–f and Table S3).

Density functional theory (DFT) computations supported these structural features. Geometry optimizations of [1]+ and [1·O2]+ (Figure 2b) with ORCA 458 at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/Def2-TZVP level of theory59–65 and a tetrahydrofuran conductor-like polarizable continuum model66 predicted an end-on CuO2•− triplet with a CuOO angle of 113° and similar lengthening of the Cu–S bond upon O2 binding (2.32 to 2.50 Å). The calculated thermodynamics of O2 binding also agreed reasonably with experiment (vide supra), showing ΔΔH[1]–[2] = +1.3 kcal/mol and ΔΔS[1]–[2] = +1.7 cal/mol·K. The calculated vibrations (Cu–O 378 cm−1, O–O 1173 cm−1) also comport with our Raman assignments.

Beyond its demonstrable CuII–S interaction, [1·O2]B-(C6F5)4 was remarkable for its stability. Monitoring its formation by UV/vis spectroscopy showed no decay or dimerization over 4 h,32,49 unlike the previously reported cases with sulfur-substituted ligand frameworks. Cycling a solution from −135 °C to +25 °C and back again gave ~95% recovery of [1·O2]+, illustrating clean and reversible dioxygen binding (see Figure S2).

Such stability enabled further reactivity studies. Hydrogen atom abstraction (HAA) by [1·O2]+ was probed using 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-ol (TEMPO–H; Scheme 2).67 Monitoring the 742 nm band by UV/vis spectroscopy (2-MeTHF, −135 °C) in the presence of excess TEMPO-H68 (25–200 equiv) revealed [1·O2]+ to decay isosbestically by pseudo-first-order kinetics (Figure 4), allowing extraction of a second-order rate constant k2 = 1.28 × 10−1 M−1 s−1 (see SI Figures S6–S7 and Table S4), to the putative cupric hydroperoxide [1·OOH]+ (330 nm, 400 nm) in >94% yields (see Section 10 in the SI). Deuteration (100–750 equiv of TEMPO–D69) slowed the decay of [1·O2]+ with kD = 0.24 × 10−1 M−1 s−1, revealing a primary kinetic isotope effect (KIE) of kH/kD = 5.4 (see Figures S8–S9), indicating a rate-limiting HAA process. To probe the effect of Sthioether substitution on the HAA reactivity with the O–H bond of TEMPO–H, the rates of the reaction of [2·O2]+ were reevaluated in 2-MeTHF at −135 °C and contrasted with that of [1·O2]+.48 The obtained pseudofirst-order rate constants (kobs) were plotted (see Figures S10–S11 and Table S5) to yield a second-order rate constant k2 = 0.82 × 10−1 M−1 s−1 indicating a slightly slower HAA reactivity by [2·O2]+ (Figure S12). Quantitation of the products of the HAA reaction between [1·O2]+ and TEMPO–H, i.e., [1·OOH]+ and TEMPO•, was carried out by showing that the hydroperoxide [1·OOH]+ protonates to give H2O2 (see Figures S13–S14) and that electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy reveals the production of CuII in [1·OOH]+ along with the TEMPO• radical in an ~1:1 ratio (see Figure 4 above). These results illustrate that [1·O2]+ performs HAA both cleanly and competently. Thus, [1·O2]+ is the first thioether CuM model to demonstrate CuM reactivity.

Scheme 2.

HAA from TEMPO–H by [1·O2]+

Figure 4.

(a) UV/vis (2-MeTHF, −135 °C) and (b) EPR spectroscopic monitoring of the reaction between [1·O2]+ and TEMPO–H to generate [1·OOH]+ and TEMPO•. See Figure S15 for EPR simulation and further discussion.

With this report, we have outlined the stability and reactivity of [1·O2]+, the first CuM model complex to both unambiguously possess a CuII–S interaction and perform CuM-like HAA. Careful selection of solvent and temperature was crucial to successfully access this superoxide complex. Ongoing research includes studies to obtain deeper insights into the electronic structure of [1·O2]+ and their correlation to [2·O2]+. This system will be a valuable point of comparison for future work targeting the influence of a sulfur-based ligand in CuI/O2 oxidative reactivity including the methionine residue at the CuM active site of noncoupled binuclear copper monooxygenases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our research was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) under Awards GM60353 (K.D.K.) and DK31450 (E.I.S.) and the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award F32GM131602 (W.J.T.). We acknowledge the use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the NIH, NIGMS (P30GM133894). Continuous support of the German research council (DFG) and Federal Ministry of education and research (BMBF) is acknowledged. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIGMS or NIH.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.1c00260.

Experimental details, characterization data, and X-ray crystallographic data for [1]B(C6F5)4 (PDF)

Accession Codes

CCDC 2057574 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336033.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/jacs.1c00260

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Mayukh Bhadra, Department of Chemistry, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland 21218, United States.

Adam Neuba, Department of Chemistry, University of Paderborn, Paderborn D-33098, Germany.

Keith O. Hodgson, Department of Chemistry, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States; Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University, Menlo Park, California 94025, United States

Britt Hedman, Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University, Menlo Park, California 94025, United States.

Edward I. Solomon, Department of Chemistry, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States; Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University, Menlo Park, California 94025, United States.

Kenneth D. Karlin, Department of Chemistry, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland 21218, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Klinman JP Mechanisms Whereby Mononuclear Copper Proteins Functionalize Organic Substrates. Chem. Rev 1996, 96, 2541–2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Prigge ST; Eipper BA; Mains RE; Amzel LM Dioxygen Binds End-On to Mononuclear Copper in a Precatalytic Enzyme Complex. Science 2004, 304, 864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Klinman JP The Copper-Enzyme Family of Dopamine β-Monooxygenase and Peptidylglycine α-Hydroxylating Monooxygenase:Resolving the Chemical Pathway for Substrate Hydroxylation. J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281, 3013–3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Solomon EI; Heppner DE; Johnston EM; Ginsbach JW; Cirera J; Qayyum M; Kieber-Emmons MT; Kjaergaard CH; Hadt RG; Tian L Copper Active Sites in Biology. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 3659–3853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Crespo A; Martí MA; Roitberg AE; Amzel LM; Estrin DA The Catalytic Mechanism of Peptidylglycine α-Hydroxylating Monooxygenase Investigated by Computer Simulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 12817–12828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Yoshizawa K; Kihara N; Kamachi T; Shiota Y Catalytic Mechanism of Dopamine β-Monooxygenase Mediated by Cu(III)–oxo. Inorg. Chem 2006, 45, 3034–3041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Abad E; Rommel JB; Kaestner J Reaction Mechanism of the Bicopper Enzyme Peptidylglycine α-Hydroxylating Monooxygenase. J. Biol. Chem 2014, 289, 13726–13738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Chen P; Bell J; Eipper BA; Solomon EI Oxygen Activation by the Noncoupled Binuclear Copper Site in Peptidylglycine α-Hydroxylating Monooxygenase. Spectroscopic Definition of the Resting Sites and the Putative CuIIM–OOH Intermediate. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 5735–5747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Chen P; Solomon EI Oxygen Activation by the Noncoupled Binuclear Copper Site in Peptidylglycine α-Hydroxylating Monooxygenase. Reaction Mechanism and Role of the Noncoupled Nature of the Active Site. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 4991–5000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Cowley RE; Tian L; Solomon EI Mechanism of O2 activation and substrate hydroxylation in noncoupled binuclear copper monooxygenases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2016, 113, 12035–12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).For a recently proposed alternative, see:; Wu P; Fan F; Song J; Peng W; Liu J; Li C; Cao Z; Wang B Theory Demonstrated a “Coupled” Mechanism for O2 Activation and Substrate Hydroxylation by Binuclear Copper Monooxygenases. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 19776–19789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Cowley RE; Cirera J; Qayyum MF; Rokhsana D; Hedman B; Hodgson KO; Dooley DM; Solomon EI Structure of the Reduced Copper Active Site in Preprocessed Galactose Oxidase: Ligand Tuning for One-Electron O2 Activation in Cofactor Biogenesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 13219–13229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Shepard EM; Dooley DM Inhibition and Oxygen Activation in Copper Amine Oxidases. Acc. Chem. Res 2015, 48, 1218–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Johnson BJ; Yukl ET; Klema VJ; Klinman JP; Wilmot CM Structural Snapshots from the Oxidative Half-reaction of a Copper Amine Oxidase: Implications For O2 Activation. J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288, 28409–28417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Hess CR; Wu Z; Ng A; Gray EE; McGuirl MA; Klinman JP Hydroxylase Activity of Met471Cys Tyramine β-Monooxygenase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 11939–11944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Eipper BA; Quon AS; Mains RE; Boswell JS; Blackburn NJ The Catalytic Core of Peptidylglycine α-Hydroxylating Monooxygenase: Investigation by Site-Directed Mutagenesis, Cu X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy, and Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 2857–2865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Bauman AT; Broers BA; Kline CD; Blackburn NJ A Copper–Methionine Interaction Controls the pH-Dependent Activation of Peptidylglycine Monooxygenase. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 10819–10828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Hess CR; Klinman JP; Blackburn NJ The Copper Centers of Tyramine β-Monooxygenase and its Catalytic-Site Methionine Variants: An X-ray Absorption Study. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2010, 15, 1195–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Blackburn NJ; Rhames FC; Ralle M; Jaron S Major Changes in Copper Coordination Accompany Reduction of Peptidylglycine Monooxygenase: Implications for Electron Transfer and the Catalytic Mechanism. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2000, 5, 341–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Schindler S Reactivity of Copper(I) Complexes Towards Dioxygen. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2000, 2000, 2311–2326. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Itoh S Developing Mononuclear Copper–Active-Oxygen Complexes Relevant to Reactive Intermediates of Biological Oxidation Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res 2015, 48, 2066–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Elwell CE; Gagnon NL; Neisen BD; Dhar D; Spaeth AD; Yee GM; Tolman WB Copper–Oxygen Complexes Revisited: Structures, Spectroscopy and Reactivity. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 2059–2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Quist DA; Diaz DE; Liu JJ; Karlin KD Activation of Dioxygen by Copper Metalloproteins and Insights from Model Complexes. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2017, 22, 253–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Noh H; Cho J Synthesis, Characterization and Reactivity of Non-heme 1st Row Transition Metal-Superoxo Intermediates. Coord. Chem. Rev 2019, 382, 126–144. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Fukuzumi S; Lee YM; Nam W Structure and Reactivity of the First-row d-block Metal-Superoxo Complexes. Dalton Trans 2019, 48, 9469–9489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Maiti D; Fry HC; Woertink JS; Vance MA; Solomon EI; Karlin KDA 1:1 Copper–Dioxygen Adduct is an End-on Bound Superoxo Copper (II) Complex which Undergoes Oxygenation Reactions with Phenols. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 264–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Lee JY; Peterson RL; Ohkubo K; Garcia-Bosch I; Himes RA; Woertink J; Moore CD; Solomon EI; Fukuzumi S; Karlin KD Mechanistic Insights into the Oxidation of Substituted Phenols via Hydrogen Atom Abstraction by a Cupric–Superoxo Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 9925–9937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Wuürtele C; Gaoutchenova E; Harms K; Holthausen MC; Sundermeyer J; Schindler S Crystallographic Characterization of a Synthetic 1:1 End-on Copper Dioxygen Adduct Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2006, 45, 3867–3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Fujisawa K; Tanaka M; Moro-oka Y; Kitajima N A Monomeric Side-on Superoxo Copper(II) Complex: Cu(O2)(HB-(3-tBu-5-iPrpz)3). J. Am. Chem. Soc 1994, 116, 12079–12080. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Kunishita A; Kubo M; Sugimoto H; Ogura T; Sato K; Takui T; Itoh S Mononuclear Copper(II)–Superoxo Complexes that Mimic the Structure and Reactivity of the Active Centers of PHM and DβM. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 2788–2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Zhang CX; Kaderli S; Costas M; Kim E.-i.; Neuhold YM; Karlin KD; Zuberbü AD Copper(I)– Dioxygen Reactivity of [(L)CuI]+ (L= Tris (2-pyridylmethyl)amine): Kinetic/Thermodynamic and Spectroscopic Studies Concerning the Formation of Cu–O2 and Cu2–O2 Adducts as a Function of Solvent Medium and 4-Pyridyl Ligand Substituent Variations. Inorg. Chem 2003, 42, 1807–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Bhadra M; Lee JYC; Cowley RE; Kim S; Siegler MA; Solomon EI; Karlin KD Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding Enhances Stability and Reactivity of Mononuclear Cupric Superoxide Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 9042–9045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Diaz DE; Quist DA; Herzog AE; Schaefer AW; Kipouros I; Bhadra M; Solomon EI; Karlin KD Impact of Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding on the Reactivity of Cupric Superoxide Complexes with O–H and C–H Substrates. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2019, 58, 17572–17576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kodera M; Kita T; Miura I; Nakayama N; Kawata T; Kano K; Hirota S Hydroperoxo–Copper(II) Complex Stabilized by N3S-Type Ligand Having a Phenyl Thioether. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 7715–7716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Zhou L; Nicholas KM Imidazole Substituent Effects on Oxidative Reactivity of Tripodal (imid)2(thioether) CuI Complexes. Inorg. Chem 2008, 47, 4356–4367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Aboelella NW; Gherman BF; Hill LM; York JT; Holm N; Young VG; Cramer CJ; Tolman WB Effects of Thioether Substituents on the O2 Reactivity of β-Diketiminate–Cu(I) Complexes: Probing the Role of the Methionine Ligand in Copper Monooxygenases. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 3445–3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Lee Y; Lee D-H; Park GY; Lucas HR; Narducci Sarjeant AA; Kieber-Emmons MT; Vance MA; Milligan AE; Solomon EI; Karlin KD Sulfur Donor Atom Effects on Copper(I)/O2 Chemistry with Thioanisole Containing Tetradentate N3S Ligand Leading to μ-1, 2-Peroxo-Dicopper(II) Species. Inorg. Chem 2010, 49, 8873–8885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Martínez-Alanis PR; Sanchez Eguia BN; Ugalde-Saldívar VM; Regla I; Demare P; Aullón G; Castillo I Copper Versus Thioether-Centered Oxidation: Mechanistic Insights into the NonInnocent Redox Behavior of Tripodal Benzimidazolylaminothioether Ligands. Chem. - Eur. J 2013, 19, 6067–6079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Hoppe T; Josephs P; Kempf N; Wölper C; Schindler S; Neuba A; Henkel G An Approach to Model the Active Site of Peptidglycine-α-hydroxylating monooxygenase (PHM). Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem 2013, 639, 1504–1511. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Tano T; Mieda K; Sugimoto H; Ogura T; Itoh S A Copper Complex Supported by an N2S-Tridentate Ligand Inducing Efficient Heterolytic O–O Bond Cleavage of Alkylhydroperoxide. Dalton Trans 2014, 43, 4871–4877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Lee D-H; Hatcher LQ; Vance MA; Sarangi R; Milligan AE; Narducci Sarjeant AA; Incarvito CD; Rheingold AL; Hodgson KO; Hedman B; Solomon EI; Karlin KD Copper(I) Complex O2-Reactivity with a N3S Thioether Ligand: a Copper–Dioxygen Adduct Including Sulfur Ligation, Ligand Oxygenation, and Comparisons with All Nitrogen Ligand Analogues. Inorg. Chem 2007, 46, 6056–6068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Hatcher LQ; Lee D-H; Vance MA; Milligan AE; Sarangi R; Hodgson KO; Hedman B; Solomon EI; Karlin KD Dioxygen Reactivity of a Copper(I) Complex with a N3S Thioether Chelate; Peroxo–Dicopper(II) Formation Including Sulfur-Ligation. Inorg. Chem 2006, 45, 10055–10057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Park GY; Lee Y; Lee D-H; Woertink JS; Sarjeant AAN; Solomon EI; Karlin KD Thioether S-ligation in a Side-on μ-η2:η2-peroxodicopper(II) complex. Chem. Commun 2010, 46, 91–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Kim S; Ginsbach JW; Billah AI; Siegler MA; Moore CD; Solomon EI; Karlin KD Tuning of the Copper–Thioether Bond in Tetradentate N3S (thioether) Ligands; O–O Bond Reductive Cleavage via a [CuII2(μ-1,2-peroxo)]2+/[CuIII2(μ-oxo)2]2+ Equilibrium. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 8063–8071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Kim S; Lee JY; Cowley RE; Ginsbach JW; Siegler MA; Solomon EI; Karlin KD A N3S(thioether)-ligated CuII-superoxo with Enhanced Reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 2796–2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Wittmann H; Raab V; Schorm A; Plackmeyer J; Sundermeyer J Complexes of Manganese, Iron, Zinc, and Molybdenum with a Superbasic Tris (guanidine) Derivative of Tris (2-ethylamino) amine (Tren) as a Tripod Ligand. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2001, 2001, 1937–1948. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Schatz M; Raab V; Foxon SP; Brehm G; Schneider S; Reiher M; Holthausen MC; Sundermeyer J; Schindler S Combined Spectroscopic and Theoretical Evidence for a Persistent End-On Copper Superoxo Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2004, 43, 4360–4363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Maiti D; Lee DH; Gaoutchenova K; Würtele C; Holthausen MC; Narducci Sarjeant AA; Sundermeyer J; Schindler S; Karlin KD Reactions of a Copper(II) Superoxo Complex Lead to C–H and O–H Substrate Oxygenation: Modeling Copper-Monooxygenase C–H Hydroxylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2008, 47, 82–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Karlin KD; Wei N; Jung B; Kaderli S; Zuberbuehler AD Kinetic, Thermodynamic, and Spectral Characterization of the Primary Copper-Oxygen (Cu-O2) Adduct in a Reversibly Formed and Structurally Characterized Peroxo-dicopper(II) Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1991, 113, 5868–5870. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Peterson RL; Himes RA; Kotani H; Suenobu T; Tian L; Siegler MA; Solomon EI; Fukuzumi S; Karlin KD Cupric Superoxo-Mediated Intermolecular C–H Activation Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 1702–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Woertink JS; Tian L; Maiti D; Lucas HR; Himes RA; Karlin KD; Neese F; Würtele C; Holthausen MC; Bill E; Sundermeyer J; Schindler S; Solomon EI Spectroscopic and Computational Studies of an End-on Bound Superoxo-Cu(II) Complex: Geometric and Electronic Factors That Determine the Ground State. Inorg. Chem 2010, 49, 9450–9459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Peterson RL; Ginsbach JW; Cowley RE; Qayyum MF; Himes RA; Siegler MA; Moore CD; Hedman B; Hodgson KO; Fukuzumi S; Solomon EI; Karlin KD Stepwise Protonation and Electron-Transfer Reduction of a Primary Copper–Dioxygen Adduct. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 16454–16467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).DuBois JL; Mukherjee P; Stack TDP; Hedman B; Solomon EI; Hodgson KO A Systematic K-edge X-ray Absorption Spectroscopic Study of Cu(III) Sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 5775–5787. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Kau LS; Spira-Solomon DJ; Penner-Hahn JE; Hodgson KO; Solomon EI X-ray Absorption Edge Determination of the Oxidation State and Coordination Number of Copper. Application to the Type3 Site in Rhus vernicifera Laccase and its Reaction with Oxygen. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1987, 109, 6433–6442. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Flörke U; Josephs P CCDC 1846820; Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2018, DOI: 10.5517/ccdc.csd.cc1zzrvk. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Flörke U; Josephs P CCDC 1846881; Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2018, DOI: 10.5517/ccdc.csd.cc1zzttl. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Groom CR; Bruno IJ; Lightfoot MP; Ward SC The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B: Struct. Sci., Cryst. Eng. Mater 2016, 72, 171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Neese F Software update: the ORCA program system, version 4.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci 2018, 8, No. e1327. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Becke AD Density-functional Exchange-energy Approximation with Correct Asymptotic Behavior. Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys 1988, 38, 3098–3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Lee C; Yang W; Parr RG Development of the Colle-Salvetti Correlation-energy Formula into a Functional of the Electron Density. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys 1988, 37, 785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Grimme S; Ehrlich S; Goerigk L Effect of the Damping Function in Dispersion Corrected Density Functional Theory. J. Comput. Chem 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Grimme S; Antony J; Ehrlich S; Krieg H A Consistent and Accurate ab initio Parametrization of Density Functional Dispersion Correction (DFT-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys 2010, 132, 154104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Weigend F; Ahlrichs R Balanced Basis Sets of Split Valence, Triple Zeta Valence and Quadruple Zeta Valence Quality for H to Rn: Design and Assessment of Accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Neese F; Wennmohs F; Hansen A; Becker U Efficient, Approximate and Parallel Hartree-Fock and Hybrid DFT Calculations. A ‘Chain-of-Spheres’ Algorithm for the Hartree-Fock Exchange. Chem. Phys 2009, 356, 98. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Weigend F Accurate Coulomb-fitting Basis Sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2006, 8, 1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Barone V; Cossi M Quantum Calculation of Molecular Energies and Energy Gradients in Solution by a Conductor Solvent Model. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 1995–2001. [Google Scholar]

- (67).Warren JJ; Tronic TA; Mayer JM Thermochemistry of Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Reagents and its Implications. Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 6961–7001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Mader EA; Davidson ER; Mayer JM Large Ground-State Entropy Changes for Hydrogen Atom Transfer Reactions of Iron Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 5153–5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Wu A; Mader EA; Datta A; Hrovat DA; Borden WT; Mayer JM Nitroxyl Radical Plus Hydroxylamine Pseudo Self-Exchange Reactions: Tunneling in Hydrogen Atom Transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 11985–11997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.