Abstract

Most quality control pathways target misfolded proteins to prevent toxic aggregation and neurodegeneration 1. Dimerization quality control (DQC) further improves proteostasis by eliminating complexes of aberrant composition 2, yet how it detects incorrect subunits is still unknown. Here, we provide structural insight into target selection by SCFFBXL17, a DQC E3 ligase that ubiquitylates and helps degrade inactive heterodimers of BTB proteins, while sparing functional homodimers. We find that SCFFBXL17 disrupts aberrant BTB dimers that fail to stabilize an intermolecular β-sheet around a highly divergent β-strand of the BTB domain. Complex dissociation allows SCFFBXL17 to wrap around a single BTB domain for robust ubiquitylation. SCFFBXL17 therefore probes both shape and complementarity of BTB domains, a mechanism that is well suited to establish quality control of complex composition for recurrent interaction modules.

Keywords: ubiquitin, quality control, BTB domain, KEAP1, FBXL17, dimerization, domain swap

The signaling networks of metazoan development rely on recurrent interaction modules, such as BTB domains or zinc fingers, which often mediate specific dimerization events 3. By forming stable homodimers 4–7, ~200 human BTB proteins control stress responses, cell division, or differentiation 8–17. Extensive conservation of the BTB dimer interface causes frequent heterodimerization, which disrupts signaling and needs to be corrected for development to proceed 2.

Accordingly, dimerization quality control (DQC) by the E3 ligase SCFFBXL17 degrades BTB dimers with wrong or mutant subunits, while it leaves active homodimers intact 2. BTB proteins could give rise to ~20,000 heterodimers and potentially more mutant complexes, yet how SCFFBXL17 can recognize such a wide range of substrates, while retaining specificity, is unknown. How SCFFBXL17 discriminates complexes based on composition is also unclear, especially as heterodimers contain the same subunits that are not recognized when forming homodimers. Here, we addressed these issues by combining structural studies of substrate-bound SCFFBXL17 with biochemical analyses of DQC target selection.

To generate SCFFBXL17 substrates for structural investigation, we mutated residues near the dimerization helix of KEAP1, whose BTB domain had been characterized by X-ray crystallography 6,18. As with other BTB proteins 2, SCFFBXL17 detected KEAP1F64A, KEAP1V98A, and KEAP1V99A, but not wildtype KEAP1, with submicromolar affinity (Fig. 1a; Extended Data Fig. 1a, b). Despite these differences in SCFFBXL17 recognition, wildtype and mutant BTB domains formed dimers in size exclusion chromatography and SEC-MALS analyses (Extended Data Fig. 1c, d). These dimers possessed similar stability towards unfolding by urea, with the unfolding of mutant BTB domains proceeding through an intermediate that might reflect local conformational changes described below (Extended Data Fig. 1e, f). Crystal structures showed that KEAP1F64A and KEAP1V98A adopted the same BTB dimer fold as wildtype KEAP1 (Fig. 1b), with a Cα root mean square deviation of only ~0.2 Å between these proteins (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1g). We conclude that SCFFBXL17 must exploit features other than persistent structural changes to select substrates for DQC.

Figure 1: SCFFBXL17 binds monomeric BTB domains.

a. 35S-labeled KEAP1 variants are recognized by immobilized FBXL17. Binding of mutant KEAP1 to FBXL17 was performed five times. b. Mutant (blue) and wildtype (green) KEAP1 BTB domains adopt the same dimer fold, as shown by X-ray crystallography at 2.2-2.5 Å resolution. c. 8.5 Å resolution cryo-EM structure of a complex between CUL1 (residues 1-410; medium gray); SKP1 (light gray); FBXL17 (orange); and KEAP1V99A (blue). X-ray coordinates of the FBXL17-SKP1-BTB complex (Fig. 2) and CUL1-RBX1 28 were fitted into the cryo-EM density. d. FBXL17 and CUL3 recognize overlapping surfaces on the BTB domain of KEAP1. CUL3 (magenta) was superposed onto the KEAP1 BTB domain based on PDB ID 5NLB.

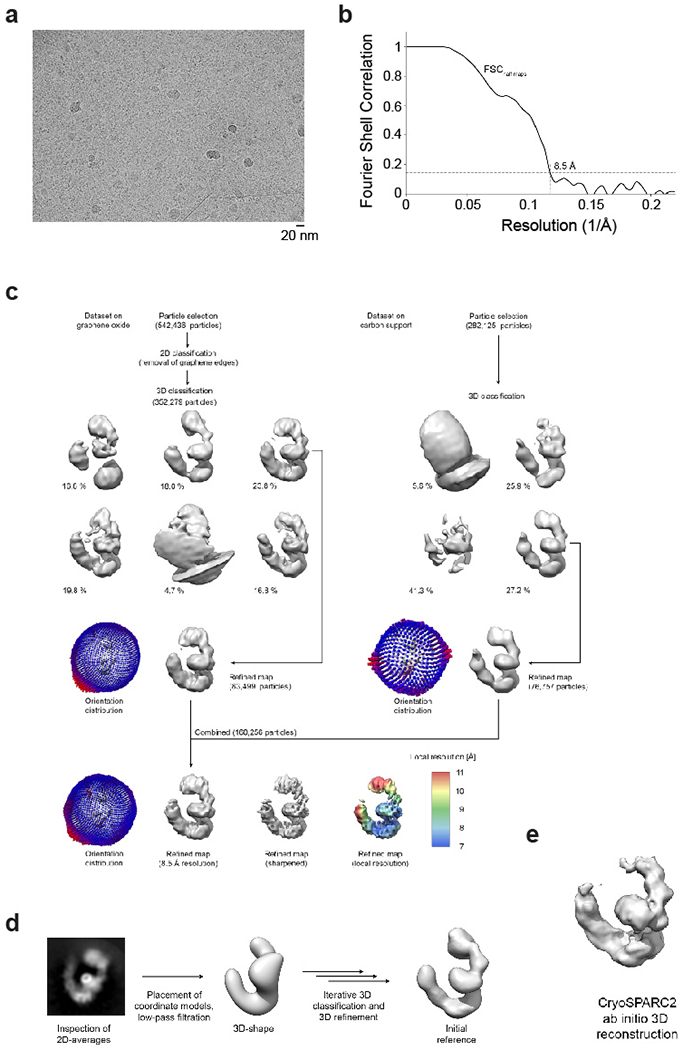

We therefore purified a complex of FBXL17, SKP1, the amino-terminal half of CUL1, and KEAP1V99A and solved its cryo-electron microscopy (EM) structure to 8.5 Å resolution (Fig. 1c, Extended Data Fig. 2; Extended Data Fig. 3a, b). We found that FBXL17 engaged the BTB domain of KEAP1V99A in a manner mutually exclusive with KEAP1’s interaction with CUL3 (Fig. 1c, d). CUL3 did not prevent SCFFBXL17 from ubiquitylating a BTB protein, suggesting that DQC is dominant over CUL3 (Extended Data Fig. 3c). The active site of SCFFBXL17, marked by RBX1 19, was next to the Kelch-repeats of KEAP1V99A (Fig. 1c), and SCFFBXL17 ubiquitylated BTB proteins with Kelch-repeats more efficiently than BTB domains (Extended Data Fig. 3d, e). This suggests that substrate selection and ubiquitylation by SCFFBXL17 occur in distinct target domains. Yet, the structure’s most notable feature was its stoichiometry: although KEAP1V99A formed dimers, SCFFBXL17 bound a single BTB domain (Fig. 1c). This indicated that SCFFBXL17 targets BTB dimers that dissociate more frequently or are split apart more easily than their homodimeric counterparts.

Focusing on the specificity determinant of DQC, we mixed SKP1-FBXL17 and the BTB domain of KEAP1F64A (Extended Data Fig. 4a) and obtained a 3.2 Å resolution crystal structure of the resulting complex (Fig. 2a; Extended Data Table 1). The crystal structure fit well into the map independently obtained by cryo-EM (Fig. 1c). As expected, FBXL17 uses its F-box to bind SKP1-CUL1 (Fig. 2a; Extended Data Fig. 4b, c), yet relies on a domain of 12 leucine rich repeats (LRRs) to recruit its targets. The LRRs of FBXL17 form a solenoid around the BTB domain, with residues in the last four LRRs directly engaging the substrate (Fig. 2b). FBXL17’s substrate-binding domain is longer and more curved than that of other LRR proteins 20,21 (Extended Data Fig. 4d), and closely follows the BTB domain’s shape (Fig. 2b). Downstream of its LRRs, FBXL17 contains a carboxy-terminal helix (CTH), which allows FBXL17 to encircle the BTB domain (Fig. 2b–e). The CTH crosses the BTB dimer interface, which explains why FBXL17 ultimately binds single BTB domains (Fig. 2d, e). Structural models indicated that many BTB domains, which are similar in shape but distinct in sequence, could be accommodated by FBXL17 (Extended Data Fig. 4e), while the slightly larger BTB-fold proteins SKP1 or Elongin C, which are not substrates for DQC, would clash with FBXL17 (Extended Data Fig. 4f). In addition to confirming monomer capture, these results implicated the shape of BTB domains as a specificity determinant for DQC.

Figure 2: Crystal structure of substrate-bound FBXL17 reveals specificity determinants of DQC.

a. Side view of the 3.2 Å X-ray structure of a complex between SKP1 (gray), FBXL17 (orange), and the BTB domain of KEAP1F64A (residues 48-180; blue). b. Top view of the SKP1-FBXL17-BTB complex showing how FBXL17 encircles the BTB domain through its LRRs and the C-terminal helix (CTH). c. Side view of the SKP1-FBXL17-BTB complex. d. The CTH binds a conserved area of the BTB domains (blue: high conservation; red: low conservation). e. The CTH crosses the dimerization interface of the BTB domain in a position typically occupied by another subunit in the BTB dimer (green).

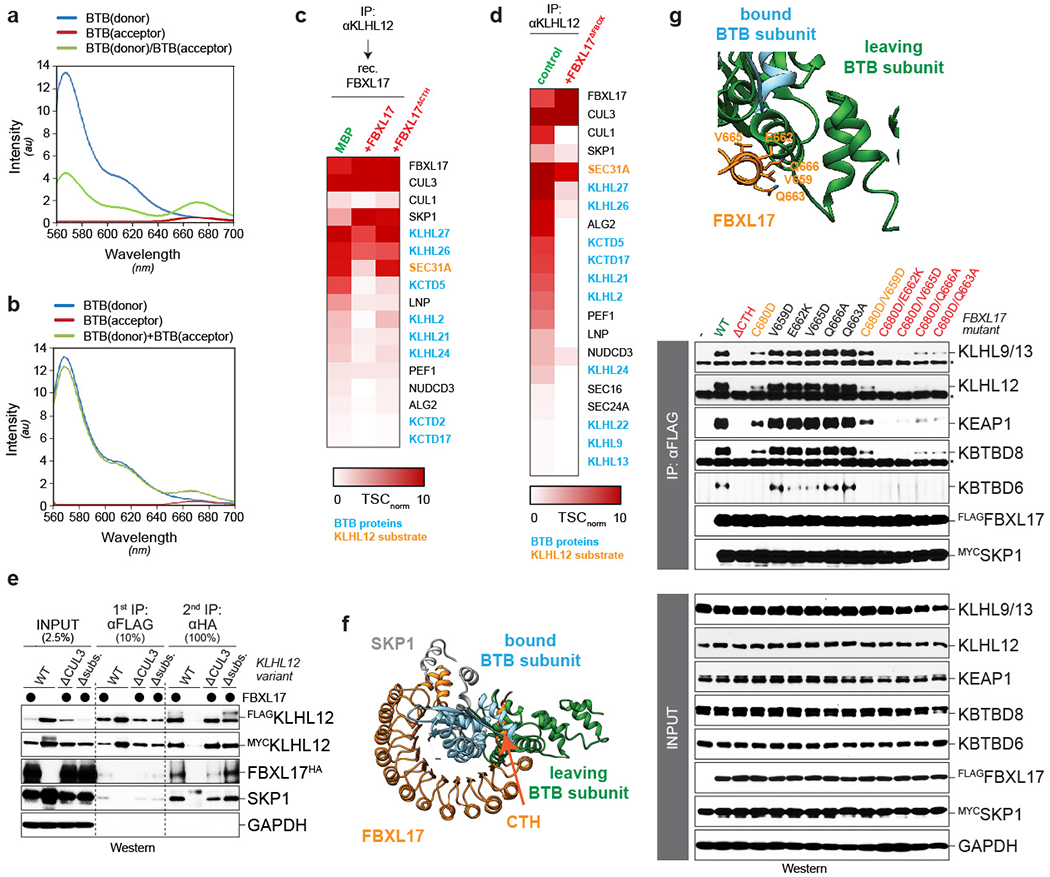

To validate our structures, we monitored the effects of FBXL17 mutations on target selection in cells. By investigating nascent KEAP1 2, we found that single mutations in FBXL17 rarely affected substrate binding or degradation (Fig. 3a–c; Extended Data Fig. 5a, b). By contrast, if mutations in LRRs and CTH were combined, recognition of KEAP1 by SCFFBXL17 and its proteasomal degradation were obliterated (Fig. 3a–c). Our mutant collection showed that even residual binding to SCFFBXL17 triggered degradation, as seen with the C574A/W626A or W626A/L677A variants of FBXL17. Proteomic analyses found that combined LRR mutations or CTH deletion impacted recognition of all BTB targets by FBXL17 (Fig. 3d). While deletion of the CTH prevented recognition of BTB heterodimers (Fig. 3b–d; Extended Data Fig. 5c, d), the CTH itself was unable to bind DQC targets (Extended Data Fig. 5c).

Figure 3: Multiple surfaces of FBXL17 contribute to substrate binding.

a. Detailed view of the interface between FBXL17 (orange) and the BTB domain of KEAP1F64A (blue). b. Combined mutation of FBXL17 residues in LRRs and CTH prevents recognition of HAKEAP1, as shown by FBXL17FLAG affinity-purification and quantitative αHA-LiCor Western blotting. c. Combined mutations in FBXL17 interfere with proteasomal degradation of KEAP1, as monitored by quantitative Western blotting. d. Mutations in FBXL17 prevent recognition of endogenous BTB proteins, as determined by affinity-purification and mass spectrometry. The heat map shows total spectral counts normalized to FBXL17. e. Mutation of residues in HAKEAP1 inhibits binding to SCFFBXL17, as seen upon FBXL17FLAG affinity-purification and quantitative αHA-Western blotting. f. Combined mutations in KEAP1 inhibit SCFFBXL17-dependent degradation, as monitored by quantitative Western blotting.

Similarly, mutation of multiple KEAP1 residues at the interface with FBXL17 was required to abolish E3 binding and degradation (Fig. 3e, f; Extended Data Fig. 6a, b). Flexibility in substrate recognition was also implied by the observation that A60 of KLHL12 2, but not the corresponding A109 of KEAP1, was required for FBXL17-binding (Extended Data Fig. 6a), likely a consequence of KEAP1A109 being slightly removed from the FBXL17 interface (Extended Data Fig. 6c). Combined with the relatively poor conservation of BTB residues at the interface with FBXL17 (Extended Data Fig. 7), these findings showed that FBXL17 can accommodate significant sequence variation among BTB proteins to provide quality control against a large domain family.

How DQC can discriminate homo- versus heterodimers, even if these contain overlapping subunits? As FBXL17 ultimately captures BTB monomers, it might disrupt aberrant dimers, exploit spontaneous complex dissociation, or use a combination thereof. Suggestive of complex disassembly, fluorescence resonance energy transfer measurements showed that FBXL17, but not FBXL17ΔCTH, caused dissociation of KEAP1F64A dimers (Fig. 4a, b; Extended Data Fig. 8a). Excess unlabeled KEAP1 or GroEL, which should capture monomers arising from spontaneous dimer disassembly, had only minor effects (Fig. 4a, b), and mixtures of BTB domains labeled with either FRET donor or acceptor established insignificant FRET after prolonged incubation (Extended Data Fig. 8b). Treatment of endogenous KLHL12 complexes with FBXL17, but not FBXL17ΔCTH, also strongly reduced BTB heterodimerization (Extended Data Fig. 8c), and an FBXL17 variant that can bind, but not ubiquitylate, its targets inhibited KLHL12 heterodimerization in cells (Extended Data Fig. 8d).

Figure 4: A domain-swapped β-sheet in BTB domains controls access to SCFFBXL17.

a. KEAP1F64A BTB dimers labeled with distinct fluorophores dissociate, as shown by loss of donor fluorescence quenching, upon incubation with FBXL17. Inactive FBXL17ΔCTH, excess unlabeled BTB domains (KEAP1F64A; KEAP1V98A), GroEL, or MBP did not have strong effects. Dissociation by FBXL17 was measured three times. b. Overnight incubation of FRET-labeled KEAP1F64A BTB dimers with FBXL17, FBXL17ΔCTH, or excess unlabeled KEAP1F64A BTB domain. Dissociation was measured 2-3 times. c. The amino-terminal β-strand of the KEAP1 BTB domain forms an intermolecular sheet in dimers, but adopts an intramolecular conformation in the BTB monomer bound to SCFFBXL17. d. Binding of 35S-labeled KEAP1 variants with mutations in the domain-swapped β-sheet to MBPFBXL17. This experiment was performed once. e. 35S-labeled unfused BTB domains of KLHL12V50A, fused BTB domains of KLHL12V50A or fused BTB domains that were cut within the linker were bound to MBPFBXL17. Two independent experiments were performed with similar results. f. Structural model of a KLHL12-KEAP1 heterodimer shows clashes at the dimerization helix region and amino-terminal β-strand. g. 35S-labeled KLHL12-KEAP1 BTB heterodimers, mutant heterodimers, and KEAP1 BTB homodimers were bound MBPFBXL17. Two independent experiments were performed with similar results. h. 35S-labeled homodimeric KEAP1 (green), mutants with helix and β-strand residues of KLHL12 placed into the first subunit of a KEAP1 homodimer (blue), or KLHL12-KEAP1 heterodimers were incubated with MBPFBXL17 and analyzed for binding by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. Two independent experiments were performed with similar results. i. The amino-terminal β-strand and its interaction residues in the partner BTB domain evolve rapidly (high conservation: blue; no conservation: red).

Both modeling and sequential affinity-purifications found that FBXL17 could initially engage BTB dimers (Extended Data Fig. 8e, f), if its CTH were displaced from the BTB interface (Extended Data Fig. 8f). Mutation of FBXL17 residues modelled close to the leaving BTB subunit also impaired substrate binding (Extended Data Fig. 8g), which suggested that a feature of BTB dimers allows SCFFBXL17 select its targets. A likely candidate was an intermolecular anti-parallel β-sheet between a β-strand in the amino-terminus of one subunit and a carboxy-terminal β-strand of the interacting domain 4,7. In BTB monomers caught by FBXL17, the amino-terminal β-strand folds back onto its own carboxy-terminal β-strand (Fig. 4c). As the intermolecular β-sheet must be dismantled for SCFFBXL17 to capture BTB monomers, differences in its stability might allow substrate discrimination.

Indeed, mutations that disrupt the domain-swapped β-sheet strongly promoted substrate recognition by SCFFBXL17 (Fig. 4d), as did deletion of the amino-terminal β-strand 2. SCFFBXL17 binding was also stimulated by dimer interface mutations, such as V50A in KLHL12 or F64A in KEAP1 (Fig. 1a, b; Extended Data Fig. 1a–d). Combining the latter mutations with those in the β-strand did not further enhance substrate recognition by SCFFBXL17 (Fig. 4d), suggesting that altering the dimer interface displaces the domain-swapped β-strand. Conversely, if we fused the amino-terminus of KLHL12V50A to the carboxy-terminus of another BTB subunit to lock the β-strand in its dimer position, substrate recognition by SCFFBXL17 was lost (Fig. 4e).

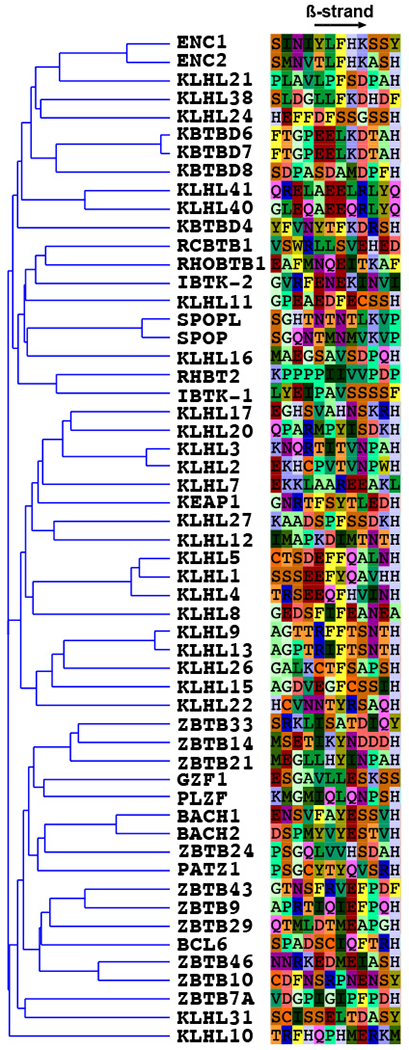

A structural model of KLHL12-KEAP1 heterodimers showed clashes only at the domain-swapped β-sheet and at neighboring residues of the dimer interface (Fig. 4f). If we replaced clashing KLHL12 residues with those of KEAP1 to anchor the domain-swapped β-strand, the heterodimer escaped capture by SCFFBXL17 (Fig. 4g). Conversely, if we introduced clashing KLHL12 residues into one subunit of KEAP1 homodimers to release the β-strand, the resulting complexes were readily detected by SCFFBXL17 (Fig. 4h). When we transferred the same residues of KEAP1 into KLHL12, the chimeric KLHL12 formed heterodimers with KEAP1 in cells (Extended Data Fig. 9a), which were strongly impaired in their association with targets of either KLHL12 or KEAP1 (Extended Data Fig. 9b, c). Thus, the domain-swapped β-sheet of BTB domains guides BTB dimerization and target selection by SCFFBXL17. The β-sheet residues are highly divergent across BTB domains, with not a single β-strand being identical (Fig. 4i; Extended Data Fig. 10). This raises the possibility that the amino-terminal β-strand evolved rapidly to constitute a molecular barcode for BTB dimerization that controls access to SCFFBXL17.

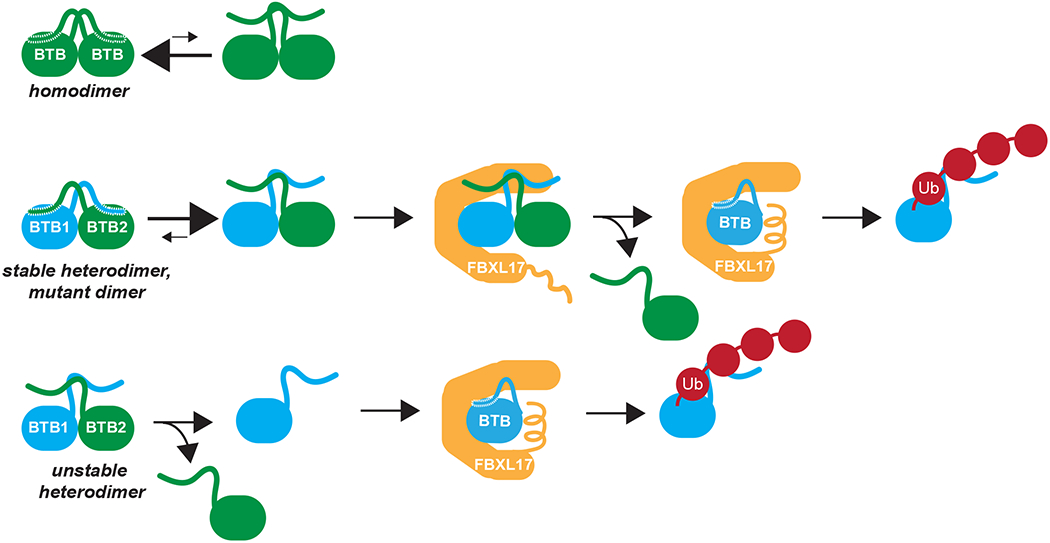

Based on these findings, we propose that BTB homodimers form a robust domain-swapped β-sheet around their amino-terminal β-strands to escape capture by SCFFBXL17 (Fig. 5). By contrast, heterodimers or mutant dimers fail to stabilize this β-sheet, which licenses them for detection and further destabilization by SCFFBXL17. Dimer dissociation produces an unbound BTB subunit that can be immediately captured by other FBXL17 molecules. We expect that FBXL17 also binds BTB monomers that emerge upon spontaneous dissociation of heterodimers composed of distantly related BTB domains. SCFFBXL17 finally wraps around and ubiquitylates single BTB domains that are similar in shape, but not necessarily in sequence. SCFFBXL17 therefore selects its targets through a mechanism that is akin to subunit exchange 22–27.

Figure 5: Model of the DQC mechanism.

BTB homodimers have identical amino-terminal β-strand mostly in the domain swapped position. This prevents SCFFBXL17 from engaging and ubiquitylating the homodimer. BTB heterodimers or mutant BTB dimers have poorly compatible helices and β-strands. Their amino-terminal β-strand will be mostly displaced, which allows for capture of these aberrant dimers by SCFFBXL17. SCFFBXL17 could further destabilize these dimers or rely on spontaneous dimer dissociation to associate with a monomeric BTB subunit for ubiquitylation and degradation.

By probing complementarity and shape of BTB domains, SCFFBXL17 discriminates complexes independently of the nature of specific subunits. Together with sequence variation accommodated by its large substrate-binding surface, this allows SCFFBXL17 to target hundreds of heterodimers, yet ignore the respective homodimers. We note that this approach could be extended to other interaction modules, such as leucine zippers or zinc fingers, which mediate specific dimerization events. Although further work is needed, we therefore anticipate that the mechanism described here will be of general importance for our understanding of quality control of complex composition.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and antibodies

All cDNAs for cellular and in vitro transcription/translation studies were cloned into pCS2+. For cellular experiments, FBXL17 was expressed as an active truncation, residues 310-701, with a C-terminal FLAG tag 2. FBXL17ΔCTH encompassed residues 310-675 with a C-terminal FLAG tag. FBXL17ΔFbox encompassed residues 366-701 with a C-terminal Myc tag. KEAP1 point mutants were made in full-length constructs with an N-terminal 3xHA tag. KLHL12 and KEAP1 BTB fusions were based on constructs encompassing residues 6-129 of KLHL12 and residues 50-178 of KEAP1, separated by a GGGSGGG linker, and with a C-terminal HA tag. In the N-swap experiments, the N-terminal sequence was defined as residues 50-58 for KEAP1 and 6-14 for KLHL12 and swapped for the N-terminal BTB in the respective fusion construct. Additional mutations in the N-terminal BTB of the fusions were made as annotated. The HRV 3C cleavable fusion constructs contained the same truncations but were instead separated by a GGGLEVLFQGGGG linker sequence and they contained an N-terminal FLAG tag instead of a C-term epitope tag. To generate chimeric KLHL12, a sequence encompassing residues 6-63 from the KLHL12 (N-swap + IL19/20AF) construct was PCR amplified and ligated into full length KLHL12 construct with a C-terminal FLAG in pCS2+. Additional constructs were generated: dominant negative (dn) Cul1 (residues 1-228 but without residues 59-82), 6xMycSKP1, KLHL123xFLAG, KLHL12HA, and KEAP1FLAG. KLHL12ΔCUL3 and KLHL12Δsubs. constructs were generated previously 8. Point mutants were generated using Quikchange (Agilent).

Antibodies used in this study were: anti-FLAG (CST, #2368, 1:5000, Lot 12), anti-HA (CST, #3724, clone C29F4, 1:15000, Lot 9), anti-c-Myc (Santa Cruz, #sc-40, clone 9E10, Lot B0519), anti-GAPDH (CST, #5174, clone D1GH11, 1:15000, Lot 7), anti-beta-Actin (MP Biomedicals, #691001, clone C4, 1:20000, Lot 04917), anti-SEC31A (BD, #612350, Clone 32/Sec31A, 1:500, Lot 8192947), anti-PEF1 (Abcam, #ab137127, clone EPR9310, 1:500, Lot GR104171-8), ALG2/PDCD6 (Proteintech, #12303-1-AP, Clone AG2949, 1:500), anti-NRF2 (CST, #12721, clone D1Z9C, 1:1000, Lot 3), anti-KLHL12 (CST, #9406, clone 2G2, 1:1000, Lot 1), anti-KEAP1 (CST, #7705, Clone D1G10, 1:1000, Lot 1), anti-KLHL9/13 (Santa Cruz, #166486, Clone D-4, 1:1000, Lot F1011), anti-KBTBD6 (Abnova, #H00089890-B01P, 1:500, Lot G2191). The anti-KBTBD8 antibody was generated previously9 (1:250). For fluorescent Western blot analysis we used secondary antibodies IRDye 800CW anti-rabbit (Li-Cor, #926-32211, 1:20000, Lot C90723-17). Blots were scanned on a Li-Cor Odyssey CLx instrument, and bands were quantified with ImageStudio. The normalized results were plotted as heatmaps using Morpheus, https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus. Original uncropped Western blots can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Cell culture analyses

We used 293T cells cultured in DMEM with GlutaMAX (Gibco, cat #10566-016) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Transfections for immunoprecipitations were performed using polyethylenimine (PEI) (Polysciences, cat#23966-2) in a 1:6 ratio of μg DNA:μl PEI. 6xMyc-Skp1 was also co-transfected with FBXL17 in a 3:1 ratio of FBXL17:Skp1. To perform the FBXL17 co-expression degradation assay 300,000 293T cells were seeded per well into 12-well plates 24 hours prior to transfection. We transfected 1 μg of DNA per well using 3μl of Transit293 (Mirus, cat #2705). The ability of FBXL17 mutants to degrade the substrate was tested using the following four conditions: 50ng WT-KEAP1HA, 950ng pCS2+ vector; 50ng WT-KEAP1HA, 300ng WT-FBXL17FLAG, 100ng 6xMycSKP1, 550ng pCS2+ vector; 50ng WT-KEAP1HA, 300ng mutant FBXL17FLAG, 100ng 6xMycSKP1, 550ng pCS2+ vector; 50ng WT-KEAP1HA, 300ng mutant FBXL17FLAG, 100ng 6xMycSKP1, 550ng pCS2+ vector, 150ng dnCUL1. The degradation of KEAP1 mutants was tested using the following five conditions: 50ng WT-KEAP1HA, 950ng pCS2+ vector; 50ng WT-KEAP1HA, 300ng WT-FBXL17FLAG, 100ng 6xMycSKP1, 550ng pCS2+ vector; 50ng mutant KEAP1HA, 950ng pCS2+ vector; 50ng mutant KEAP1HA, 300ng WT-FBXL17FLAG, 100ng 6xMycSKP1, 550ng pCS2+ vector; 50ng mutant KEAP1HA, 300ng WT-FBXL17FLAG, 100ng 6xMycSKP1, 550ng pCS2+ vector, 150ng dnCUL1. Cells were transfected for 36 hours, washed, lysed using sample loading buffer and sonicated prior to Western blot analysis. Authenticated cell lines have been purchased through ATCC; they have continuously been monitored for Mycoplasma contamination.

Immunoprecipitations

Cells were transfected for 48 hours, pelleted and resuspended in cold swelling buffer (20 mM HEPES-NaOH pH 7.5, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2) with 0.1% Triton-X100, 2 mM NaF, 0.2 mM Na3VO4 and protease inhibitors (Roche, cat #11873580001).

For transfections done in 10-cm plates, 500μl of swelling buffer was used to resuspend cells. For larger scales cells were resuspended in a 5:1 volume:mass ratio of buffer:pellet. Cells were lysed for 30 minutes on ice, 1X freeze/thawed in liquid N2 followed by 40 minutes centrifugation at 21,000g. Total protein concentration and volume of the lysate were normalized using Pierce 660 (Thermo, cat #22660). Normalized lysate was supplemented with NaCl to a final concentration of 150mM and anti-FLAG resin was added and incubated at 4°C for two hours. After four washes of the bound resin with cold wash buffer (20mM HEPES-NaOH pH 7.5, 5mM KCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton-X100, 150mM NaCl) bound proteins were eluted by addition of sample loading buffer and analyzed by Western blotting.

For the KLHL12-FBXL17 sequential immunoprecipitation, KLHL123xFLAG was purified with the anti-FLAG resin and eluted with wash buffer supplemented with 0.5 mg/mL 3xFLAG peptide (Sigma, cat #F4799). The αHA resin (Sigma, EZview cat #E6779) was blocked with 10% FBS for 20 minutes at 4°C and washed once with wash buffer. The pre-blocked αHA resin was added to the elution supplemented with 10% FBS and incubated for 2 h at 4°C. After three washes in wash buffer, sample loading buffer was added to the αHA resin, and samples were analyzed by Western.

For mass spectrometry, cells were transfected in 25 15-cm plates per condition (Fig. 3d; Extended Data Fig. 7d) or 40 plates per condition were used for endogenous KLHL123xFLAG (Extended Data Fig. 7b, c). To prepare samples for mass spectrometry, bound proteins were eluted from anti-FLAG resin using 0.5 mg/mL 3xFLAG peptide (Sigma, cat #F4799), and proteins were precipitated overnight by the addition of trichloroacetic acid (Fisher, cat #BP555) to a final concentration of 20% (w/v). Protein precipitates were washed three times in cold solution of 10mM HCl in 90% acetone; resuspended in 8 M urea, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5; reduced with 5 mM TCEP; and alkylated with 10 mM iodoacetamide. The samples were diluted with 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5 to a 2M urea concentration, supplemented with CaCl2 to 1 mM concentration. Samples were trypsinized with 1 μL of 0.5mg/mL trypsin (Promega) overnight at 37°C, and formic acid was added to 5% final concentration.

To test the effect of recombinant FBXL17 on endogenous KLHL123xFLAG binding partners, anti-FLAG resin bound with KLHL12 complexes were supplemented with 60 μg of either His-MBP-FBXL17(310-701)/Skp1, His-MBP-FBXL17ΔCTH(310-675)/Skp1, or His-MBP and 500 μL of PBST (PBS (Gibco, cat # 14190144) + 0.1% Triton-X100) and rotated overnight at 4°C. Resins were washed five times in cold wash buffer and further processed as described above.

Mass spectrometry

We used multidimensional Protein Identification Technology (MudPIT) to analyze mass spectrometry samples. The analysis was performed by the Vincent J. Coates Proteomics/Mass Spectrometry Laboratory at UC Berkeley. To generate the interaction heatmap, the normalized TSCs of select interactors in FBXL17 or BTB IPs were plotted and higher values were set to 10 using default parameters of Morpheus, https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus.

Protein purifications

All KEAP1 BTB recombinant proteins were of the 48-180 truncation and contained the S172A mutation that enhanced crystallization 6. KEAP148-180 S172A, S172A/F64A, S172A/V98A, S172A/R116C, and S172A/F64A/R116C were cloned as a His-SUMO-TEV-KEAP1 fusion into the pET28a vector. They were transformed into E. coli LOBSTR cells containing an RIL tRNA plasmid. Typically, 12 L of E. coli were grown to an OD600 of 0.6, cooled to 16 °C, induced with 0.2 mM IPTG, and shaken at 16 °C overnight. Cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (10% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM imidazole pH 8.0, 1 mM PMSF, and 1 mg/mL lysozyme), lysed by sonication, and clarified by centrifugation at 38,000 xg for 30 mins. Clarified lysate was incubated with Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen), washed with wash buffer (10% glycerol, 500 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.0, 10 mM imidazole pH 8.0, 5 mM beta-mercaptoethanol), and eluted in a column with elution buffer (10% glycerol, 250 mM imidazole pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM beta-mercaptoethanol). KEAP1 was dialyzed overnight at 4°C into buffer without imidazole (10% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM beta-mercaptoethanol), cut with TEV protease, and the tags were removed by Ni-NTA resin. KEAP1 was concentrated and then injected onto an HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg equilibrated with 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, and 1 mM TCEP at 4°C. Fractions were pooled, concentrated to 11 mg/mL, and stored at −80 °C.

His/MBP-FBXL17310-701/Skp1 and the ΔCTH variant (residues 310-675) were purified from insect cells as previously described 2. To purify SKP1/FBXL17310-701/KEAP1BTB complex for crystallography, we used a modified KEAP1BTB construct that also contained a GST tag (His-SUMO*-GST-TEV-KEAP1S172A/F64A48-180). KEAP1 protein was expressed and purified using Ni-NTA resin as described above and following the Ni elution it was bound to Skp1/His-MBP-FBXL17310-701 by mixing equal masses of Skp1/FBXL17 and KEAP1. After incubating the proteins overnight at 4 °C, KEAP1 was bound to glutathione sepharose 2B resin (GE), washed with 500 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, and 5 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, and then eluted with 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 5 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, and 20 mM reduced glutathione (Sigma) by rotating at RT for 30 mins. Following the glutathione elution, TEV was added for overnight cleavage at 4 °C. A subtractive Ni step was performed to remove the tags and then the protein complex was concentrated and injected at 4 °C onto a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg equilibrated with 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, and 1 mM TCEP. Fractions were pooled, concentrated to 20 mg/mL, and stored at −80 °C.

CTH-MBP-His and MBP-His were subcloned into a pET28a vector with the CTH (residues 676-701 of FBXL17) and MBP separated by a GGS linker sequence. Constructs were expressed in E. coli LOBSTR cells and protein was purified using Ni-NTA resin, eluted with imidazole, and further purified using size-exclusion chromatography.

The CUL11-410/SKP1/FBXL17310-701/KEAP1V99A complex for cryo-EM was purified from High Five insect cells. Two pFastBac Dual constructs, one expressing FBXL17310-701 and Skp1 and another expressing KEAP1V99A (full-length) and CUL11-410 were used to prepare separate baculoviruses according to standard protocols (Bac-to-Bac Baculovirus Expression System, Thermo Fisher). Several liters of High Five cells were split (1x106 cells/mL) and infected with SKP1/FBXL17 and KEAP1/CUL1 baculoviruses (1% v/v for each) and grown at 27 °C for 3 days prior to harvesting. Following harvesting, cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM PMSF, 10 mM imidazole, 1% NP-40 substitute, 10% glycerol). After rotating at 4 °C for 30 mins, lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 38,000 xg for 1 hour. Supernatant was bound to Ni-NTA resin, washed with wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM imidazole pH 8.0, 10% glycerol), and eluted (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, 250 mM imidazole pH 8.0, 10% glycerol). The Ni elution was dialyzed into buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 5 mM beta-mercaptoethanol and cut with TEV overnight at 4 °C. Protein was concentrated and injected onto a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200 pg equilibrated with 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES-NaOH pH 8.0, and 1 mM DTT. Fractions containing the quaternary complex were pooled, concentrated to 6 mg/mL, and stored at −80 °C.

The CUL11-410/SKP1/FBXL17310-701/KEAP1V99A cryo-EM complex was crosslinked using BS3 (bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate) (Thermo Fisher). The concentrated protein complex (24 uM) was supplemented with 1.4 mM BS3 crosslinker and incubated at RT for 30 mins. The reaction was stopped by adding Tris-HCl pH 8.0 to 25 mM and incubating an additional 10 mins.

The recombinant CUL31-197 for competition assays was cloned into pMAL-TEV-CUL31-197-his, expressed in BL21(DE3) cells and purified on amylose resin.

Crystallization and data collection

Crystals of KEAP1BTB or the mutant variants were grown using the hanging vapor diffusion method in 24-well plates. KEAP1 protein (11 mg/mL) was mixed in a 1:1 ratio with the reservoir solution. After 1-3 days at 20 °C, crystals with a needle morphology first appeared. By four days, crystals grew to dimensions of 25 μm x 25 μm x 800 μm. All of the KEAP1BTB only crystals used for structure determination were grown in wells containing reservoir solutions of 160-400 mM lithium acetate and 14-18% PEG 3350 (Hampton) as previously described 6.

Crystals of the SKP1/FBXL17310-701/KEAP1F64ABTB complex were grown using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method by mixing 100 nL of 20 mg/ml protein and 100 nL of reservoir solution within 96-well plates. After mixing, the plates were stored at 20 °C. Small rod-like crystals were first identified in the E7 condition (50 mM MgCl2, 100 mM HEPES-NaOH pH 7.5, 30% (v/v) PEG MME 550) of the Index HT sparse matrix screen by Hampton. Crystals appeared after 1 day. Crystal growth was optimized by diluting the protein to 15 mg/mL and by using a reservoir solution diluted to 75% (i.e. 37.5 uL of E7 condition and 12.5 uL of water). By two days, crystals grew to 50 μm x 50 μm x 300 μm. Crystal growth was very sensitive to the volume of the drop (i.e. no crystals formed in drops larger than 0.2 μL) and to the batch of E7 reservoir solution.

All crystals were cryo-protected by briefly soaking them in solutions containing the reservoir composition plus 20% (v/v) glycerol, before being plunged into liquid nitrogen. All data were collected on the Advanced Light Source beamline 8.3.1 at 100 K. Data collection and refinement statistics are presented in Extended Data Table 1.

X-ray crystal structure determination

Data were processed using XDS (version Jan 26, 2018) 29 and scaled and merged with Aimless (v0.7.1) 30 in CCP4 (v7.0.058) 31. Structures were solved by molecular replacement using Phenix Phaser (v2.8.2) 32. The KEAP1 structures were solved by using the published KEAP1 dimer structure coordinates (PDB ID 4CXI). The SKP1/FBXL17/KEAP1BTB complex structure was solved by searching for the KEAP1 core (residues 75-180 of PDB ID 4CXI), part of SKP1/SKP2 (all of SKP1 and the F-box of SKP2 (residues 95-137) in PDB ID 2ASS), and three LRRs of SKP2 (residues 204-279 in PDB ID 1FQV). Manual model building was performed in COOT (v0.8.9.1) 33 and models were refined using Phenix refine (v1.14) 32. The initial SKP1/FBXL17/KEAP1BTB complex model was improved using Phenix Rosetta Refine 34. The software used was curated by SBGrid 35.

SEC analysis

All analytical size-exclusion runs were performed using an ÄKTA Pure (GE) fitted with a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column or Superdex 75 Increase 10/300 GL column. The column was equilibrated with 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl 8.0, 1 mM TCEP and runs were performed using a 0.2 mL injection loop and 0.5 mL/min flow rate. Approximately 0.5 mg of protein was loaded. Molecular weight standards were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

SEC-MALS

Experiments were conducted using the Agilent Technologies 1100 series with a 1260 Infinity lamp, Dawn Heleos II and the Optilab T-Rex (Wyatt Technologies), and the Superdex 75 10/300 GL (GE). The column was equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM TCEP at a rate of 0.5 mL/min at room temperature. KEAP1 WT and F64A were injected at a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL in 100 uL. A reference standard of bovine serum albumin was also injected at a concentration of 2 mg/mL in 100 uL. The RI was used to detect the amount of mass in each peak and the light scattering was used to detect the concentration and determine the molecular weight.

Denaturation monitored by circular dichroism

KEAP1 BTB domain proteins were exchanged into buffer containing 20 mM potassium phosphate pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM TCEP (CD buffer) using size-exclusion chromatography. Both a 0 M and 8 M urea solution with 0.04 mg/mL or 0.4 mg/mL KEAP1 was made in CD buffer. These solutions were mixed in proportions to create a urea gradient series with 2.4 mL (low concentration) or 0.3 mL (high concentration) samples. These were equilibrated overnight at RT.

CD recordings were taken using a 10-mm c cuvette (low concentration) or 1-mm cuvette (high concentration) on a AVIV model 410 CD spectrometer monitoring ellipticity at 222 nm. The signal was averaged over a 1 min interval, after a 1 min equilibration. Afterwards, each sample was measured using a Zeiss refractometer and the concentration of urea was calculated according to the fit 36:

where Dh is the difference in refractive index between a given sample and the no denaturant sample.

The CD data points for wild-type KEAP1 were fit to a two-state unfolding curve:

where:

x = urea concentration

Yu = unfolded baseline y intercept

Su = unfolded baseline slope

Yf = folded baseline y intercept

Sf = folded baseline slope

m = m value (F ↔ U)

The CD data points for KEAP1 mutants were fit to a three-state unfolding curve 37:

where additionally:

Yi = intermediate baseline y intercept

Si = intermediate baseline slope

G1 = ΔG (F ↔ I)

G2 = ΔG (I ↔ U)

m1 = m value (F ↔ I)

m2 = m value (I ↔ U)

The equations were fitted to the data using the nls function in R and plotted in R as well. The Cm values were calculated from Cm = ΔG/m.

In vitro assays

Full-length BTB proteins or isolated BTB domains in pCS2+ were synthesized using the TnT quick coupled rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL) in vitro transcription/translation (IVT/T) system (Promega, cat #L2080). Each 12.5 μL in vitro reaction contained 10 μL of RRL, 0.2 μL of 35S-Methionine (11 μCi/μL, Promega, cat #NEG009H005MC), and 600 ng of pCS2+ construct. Reactions were mixed and incubated at 30°C for 1 hour. Approximately 10% of the IVT/T was saved as input. The rest of reaction was mixed with 500 μL PBST, 15 μL amylose resin (NEB, cat #E8021L), 8 μg of His-MBP-FBXL17310-701/Skp1 complex or His-MBP and incubated at 4 °C for 4h. The resin was washed five times with cold PBST supplemented with 500 mM NaCl and eluted with the sample loading buffer. The pulldown was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

To test post-translational ubiquitylation of BTB proteins or isolated BTB domains, 12.5 μL IVT/T reactions were incubated for 45 minutes at 30°C and stopped by addition of 0.5 μL of 1.5 mg/mL cycloheximide (Sigma, cat# C7698; dissolved in 99% H2O/1% DMSO). Reactions were supplemented with 1 μL of 1 mg/mL Anti-Ub Tube1 (LifeSensors, UM101), 0.5 μg of either His-MBP-FBXL17WT(310-701)/SKP1 or His-MBP-FBXL17ΔCTH(310-675)/SKP1. For CUL3 competition assay 14 μg of MBP-CUL3 (1-197) was added and incubated for 10 minutes at 30°C before 0.5 μg of His-MBP-FBXL17WT(310-701)/SKP1 was added. Reactions were incubated for another 45 minutes at 30°C, sample loading buffer was added, and ubiquitylation was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

In vitro titration reactions

Increasing concentrations of His-MBP-FBXL17WT(310-701)/SKP1 were incubated with 60 μL amylose resin (NEB, cat #E8021L) at 4 °C for 4h and washed three times in PBST. The bound resin was supplemented with 100 nM WT or F64A KEAP148-180 in 400 μL PBST and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Reactions were centrifuged at 3200 rpm for 1 minute and the supernatant was removed and mixed with sample loading buffer. Samples were run on SDS-PAGE gels, stained with Coomassie, and imaged in a Li-COR Odyssey CLx. To analyze depletion of KEAP148-180 from the supernatant, band intensities were quantified in ImageJ (v1.51r), plotted in GraphPad Prism (v8.3.0), and binding affinity was calculated using a non-linear fit and binding-saturation equation.

Structural analysis and sequence alignments

The PISA server (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/pisa/) was used to calculate the total surface interaction between FBXL17 and the KEAP1F64A BTB. PISA results were also used to determine which KEAP1 residues interacted with FBXL17, the opposing KEAP1 subunit, or CUL3 (PDB ID 5NLB) in their corresponding structures. Interacting residues were defined as containing at least 30% buried area.

The model of a KEAP1-KLHL12 heterodimer was determined by first obtaining a KLHL12 homodimer model from the SWISS-model server (https://swissmodel.expasy.org). One subunit of the KLHL12 homodimer was then aligned to one subunit within a KEAP1 wild-type homodimer. Clashing or incompatible regions were determined by manual inspection.

The map of conservation within the BTB domain was determined by first producing a sequence alignment using ClustalX (v2.1) of 22 BTB substrates of FBXL17 2. Then the surface of KEAP1 was colored by mavConservation according to a red-white-blue color scheme.

Structural alignments of the KEAP1 BTB domains and the Skp1/F-box structures were performed in Chimera (v1.11). KLHL3 (PDB ID 4HXI), BCL6 (PDB ID 1R28), BACH1 (PDB ID 2IHC), SKP1 (PDB ID 1FS1), Elongin C (PDB ID 4AJY), and the KLHL12 model generated from the SWISS-model server were aligned to the KEAP1 monomer in complex with FBXL17. The SKP1/FBXL3 (PDB ID 4I6J) and SKP1/SKP2 (PDB ID 2AST) structures were used for comparison to that of SKP1/FBXL17. Similarly, a KEAP1 homodimer was aligned to the SKP1-FBXL17-KEAP1 crystal structure in order to fit an opposing KEAP1 molecule (i.e. the leaving BTB).

The sequence alignment of the N-terminal beta strand was created by first generating a sequence alignment of 55 dimeric-type BTB domains corresponding to KEAP1 residues 48-180 using ClustalX (v2.1) with manual adjustment in Jalview (v2.10.5). A neighbor-joining tree (of the full BTB domain) was calculated in Jalview using a BLOSUM62 scoring matrix. The N-J tree was then displayed using T-rex (http://www.trex.uqam.ca) and the sequence alignment of the beta-strand region (KEAP1 residues 48-59) was colored by residue in Jalview. A smaller number of BTB sequences was used in the full BTB alignment (Extended Data Fig. 6) and were displayed using ESPrint 3 (http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/ESPript/).

Cryo-electron microscopy specimen preparation and data collection

Graphene oxide coated cryo-EM grids were prepared based on Quantifoil UltraAuFoil R 1.2/1.3 (gold) grids. Carbon coated grids were prepared by floating a thin film of continuous carbon onto Quantifoil R 2/2 holey carbon grids. After drying overnight, the carbon-coated grids were glow discharged using a Cressington Sputter Coater (10 mA current, 13 sec). 4 μL of crosslinked KEAP1-FBXL17-SKP1-CUL1 complex (approx. 2 μM concentration) in buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES-NaOH pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, and 0.012 % NP-40 substitute were applied to the carbon-coated, glow-discharged R 2/2 grids, incubated for 1 min, blotted for 16-22 sec in a Thermo Scientific Vitrobot Mk IV, and flash-frozen by plunging into liquid ethane-propane cooled by liquid N2 38. For graphene oxide-coated UltrAuFoil 1.2/1.3 grids, 4 uL of KEAP1-FBXL17-SKP1-CUL1 complex at 2 μM concentration were incubated for 30 sec on the grid, blotted for 3.5-5 sec, and flash-frozen.

Cryo-EM data were collected using a Thermo Scientific Talos Arctica transmission electron microscope operated at 200 kV acceleration voltage. Electron micrograph movies were collected in two sessions using Serial EM 39,40, one using particles on carbon support, one using particles on graphene oxide support. The dataset on carbon support was acquired using a Gatan K2 Summit direct electron detector camera, with the microscope set at 43,103 x magnification, resulting in a pixel size of 1.16 Å, using a total dose of 50 electrons/Å2 fractionated into 32 frames, and using a defocus range of −1.5 to −3.0 μm; the dataset on graphene oxide was acquired using a Gatan K3 direct electron detector camera, at 43,860x magnification, resulting in a pixel size of 1.14 Å, using a total dose of 60 electrons/Å2, fractionated into 53 frames, and by applying a defocus range of −2.0 to −3.0 μm. We collected 545 micrographs of BS3-crosslinked KEAP1-FBXL17-SKP1-CUL1 complex (see above) on carbon support and 507 micrographs on graphene oxide support (example shown in Extended Data Fig. 2a).

Cryo-EM data processing

Electron micrograph movies were drift-corrected and dose-weighed using MOTIONCOR2 41 from within FOCUS (v1.1.10) 42, or the motion correction algorithm implemented in RELION3 43. CTF parameters were estimated using GCTF 44 (carbon support dataset) and CTFFIND4 45 (graphene oxide dataset) from within RELION3, identifying 380 and 538 micrographs from the graphene oxide and carbon support datasets showing suitable quality thon rings, respectively. All further data processing (Extended Data Fig. 2c, d) was performed in RELION3 43 unless stated otherwise.

Particles on graphene oxide:

Particles were selected using the Laplacian-of-Gaussian algorithm implemented in RELION3 43. Picking was run separately for a subset of micrographs that showed gold edges in the images, which required different picking parameters due to the high contrast of the gold areas. Overall, 542,436 particles were picked, extracted and rescaled to 3.42 Å/pixel. To remove images that contain graphene oxide edges, the extracted particles were subjected to 2D classification. At this step, selecting the option to ignore the CTF until the first peak provided better results. Particles selected from gold edge-free and gold edge-containing micrographs were then joined, resulting in a dataset of 352,279 particle images. Based on previously obtained 3D references (see below), these particle images were classified into 6 3D-classes, the best-resolved of which was selected for further processing. Adding further classes to the subsequent refinement did not improve the resolution in spite of the increased particle numbers, probably due to conformational differences between the classes. The 83,499 particles thus selected were first refined and then re-extracted with re-centering, at 2.28 Å/pixel.

Particles on carbon support:

Similarly to the graphene oxide dataset, 282,125 particles were picked using the Laplacian-of-Gaussian algorithm 43 and extracted at 2.32 Å/pixel. An initial 3D reference was obtained from this dataset by assembling a model from atomic coordinates according to the domain architecture inferred from 2D class averages (Extended Data Fig. 2d), which was then low-pass filtered to 40 Å resolution and iteratively subjected to 3D classification and refinement until a stable solution was obtained. Later ab-initio 3D-reconstruction in CRYOSPARC2 46 (Extended Data Fig. 2e) resulted in an initial model that was consistent with the previously described 3D reference and also allowed fitting of PDB coordinate models corresponding to CUL1, SKP1, and FBXL17-KEAP1, indicating retrieval of the correct solution (Extended Data Fig. 2e). Using the initial reference described above, the 282,125-particle dataset was classified into 4 3D classes; one class showing the best density features was selected and the resulting 76,757 particles were refined and re-extracted with re-centering and re-scaling to 2.28 Å/pixel.

The particles on carbon and graphene oxide support showed different orientation distributions (Extended Data Fig. 2c). Therefore, the particle subsets obtained from individual processing of the datasets of particles on graphene oxide and carbon support were joined to improve coverage of projection angles, and the resulting dataset of 160,256 particles was refined using two fully independent half-sets (gold standard 47). The resulting map was sharpened using a b-factor of −723 Å2 and low-pass filtered to 8.5 Å (Extended Data Fig. 2b) for visualization. Resolution is likely limited by the high flexibility of the KEAP1 KELCH domain and the tip of CUL1, which also show very low local resolution (Extended Data Fig. 2c).

Cryo-EM map interpretation

To interpret the cryo-EM map, we docked the atomic structures of the SKP1-FBXL17-KEAPBTB complex (this work) as well as the structures of human SKP1 and CUL1 (PDB ID 1LDK) 48 as rigid bodies using UCSF CHIMERA (v1.13) 49. The N-terminal segment of the part of FBXL17 resolved in our structure (residues 319-362) was positioned independently to better fit the map due to a slight conformational difference between the X-ray crystal and cryo-EM structures. To resolve clashes at the interface between the rigid-body docked input models, we subsequently ran one macro cycle of PHENIX (v1.16) real space refinement 50 using a map weight of 0.01 and restricting the information used to 10 Å.

Protein Labeling for Fluorescence Energy Transfer

We use maleimide chemistry to introduce FRET dyes on an introduced cysteine residue, R116C, which is not involved in dimerization or FBXL17 binding. To obtain homolabeled donor and acceptor variants of KEAP1F64A, KEAP1S172A/F64A/R116C was first exchanged into filtered, degassed DPBS using SEC and subsequently concentrated to 7 mg/mL. A 20 mM stock of Alexa Fluor 555 C2 maleimide (donor, Thermo Fisher, A20346) and Alexa Fluor 647 C2 maleimide (acceptor, Thermo Fisher, A20347) were independently created by dissolving 1mg of solid dye in DMSO. KEAP1 was labeled in an overnight reaction in DPBS containing 100 μM protein, 20% degassed glycerol, and 1 mM of labeling dye. The reactions were quenched by adding beta-mercaptoethanol to a final concentration of 10 mM, spun down at 21,000 xg for 10 minutes at 4°C to eliminate any precipitation, and loaded onto a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL equilibrated with 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl 8.0, and 1 mM TCEP. Protein fractions containing dimeric KEAP1 were pooled and concentrated. Based on spectral comparisons of KEAP1F64A/S172A and KEAP1F64A/S172A/R116C labeling reactions, we estimate that >90% of the labeling was specific to the introduced cysteine and that >80% of molecules were labeled. The resulting homolabeled KEAP1F64A were then subjected to 8M urea denaturation and refolding via dialysis overnight at room temperature, protected from light. The protein was then concentrated, spun at 21,000 xg for 10 minutes at 4°C to eliminate any precipitation, and ran on a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column equilibrated with 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl 8.0, and 1 mM TCEP. The fractions containing dimeric KEAP1 were collected and concentrated.

To obtain heterolabeled KEAP1F64A, we mixed equimolar amounts of acceptor- and donor-labeled KEAP1F64A/S172A/R116C, denatured by adding urea to 8M, and refolded via dialysis overnight at room temperature in the dark. The protein was similarly concentrated, spun, and purified by SEC. The fractions containing dimeric KEAP1 were collected and concentrated.

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Assay and Analysis

All FRET assays were conducted at 4°C using a QuantaMaster QM4CW (PTI) fluorimeter and Hellma 105.251-QS cuvettes. Time courses followed the donor channel using an excitation of 555 nm and emission of 570 nm. Recordings were taken every 30 s for 2 hrs once 100 nM heterolabeled KEAP1 was mixed with 5 uM of chase protein. GroEL was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (C7688). Overnight incubations were performed by taking spectra (555 nm excitation) of 100 nM heterolabeled KEAP1 dimer, followed by an overnight 4°C incubation with 5 μM of chase protein. Similar measurements were performed for KEAP1 dimers labeled with either FRET donor or acceptor and then mixed. The bar graphs depicting percent increase in donor fluorescence upon addition of FBXL17, FBXL17ΔCTH, or KEAP1F64A were calculated from emission at 570nm. Calculations corrected for the dilution upon adding the chase protein.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1: Variant BTB domains of KEAP1 are recognized by SCFFBXL17.

a. Mutations in KEAP1’s BTB domain result in efficient recognition by SCFFBXL17. The same mutations as in Fig. 1a were introduced into the KEAP1S172A variant that had previously been used for crystallization. 35S-labeled double mutants, but not the KEAP1S172A single mutant, were retained by immobilized MBPFBXL17, as detected by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. This experiment was performed once. b. SCFFBXL17 strongly prefers mutant over wildtype BTB domains. Increasing concentrations of MBPFBXL17 were immobilized on amylose beads and incubated with 100nM wildtype or mutant KEAP1. Depletion of KEAP1 from the supernatant was measured by quantitative LiCor imaging of Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gels. The affinity of FBXL17 to wildtype KEAP1 was too low to be determined reliable by this method. Three independent experiments were performed with similar results. c. Mutant BTB domains form homodimers in vitro. Recombinant BTB domains of KEAP1, KEAP1F64A, and KEAPV98A (MW ~15kDa) were analyzed by size exclusion chromatography detecting A280. Expected position of BTB dimer versus monomer, as well as of control proteins with known MW are shown on top. Three independent experiments were performed with similar results. d. BTB domains of wildtype KEAP1 and mutant KEAP1F64A form homodimers in solution, as determined by SEC-MALS. This experiment was performed twice. e. Mutant BTB domains unfold via an intermediate species. Wild-type or mutant BTB domains of KEAP1 (0.04 mg/ml) were incubated with various concentrations of urea, equilibrated overnight, and their resulting secondary structure was monitored by ellipticity at 222 nm using circular dichroism. The experiment was performed once for the mutants and twice for the wild-type KEAP1. f. The intermediate seen in the unfolding of KEAP1V98A likely reflects local conformational changes, rather than monomerization. Urea-dependent unfolding curves for the BTB domain of KEAP1V98A were repeated at 10-fold higher BTB concentration (low: 0.04mg/ml; high: 0.4 mg/ml); only the second transition shifted to higher urea concentrations, identifying it as a dimer-unfolded transition. This experiment was performed once. g. Mutation of Phe64 or Val98 to Ala in the BTB domain of KEAP1 reduces contacts between helices of two interacting subunits of the KEAP1 dimer.

Extended Data Figure 2: Cryo-EM data collection and processing.

a. Representative micrograph (graphene oxide coated grid, imaged using a Talos Arctica and a Gatan K3 camera) showing CUL1-SKP1-FBXL17-KEAP1V98A particles. b. Resolution estimation using the FSC = 0.143 criterion 51 indicates an overall resolution of 8.5 Å for the cryo-EM reconstruction. c. Data processing scheme. Datasets were initially processed independently and then combined for the final refinement. EM volumes are shown in grey and orientation distributions are given for intermediate refinement steps. The final reconstruction is shown with and without sharpening applied, and additionally colored by local resolution (determined using RELION3). d, e. Initial model generation. We originally obtained an initial reference by generating a low-resolution volume with the overall shape of the complex observed in 2D class averages (d) and later also verified this solution using CRYOSPARC2 ab initio model generation (e; see methods for details).

Extended Data Figure 3: SCFFBXL17 binds the BTB domain, but its active site is next to the Kelch repeats of KEAP1.

a. Elution profile of the SCFFBXL17-KEAP1V99A complex by size exclusion chromatography detecting A280. Control proteins with known MW are shown on top. This experiment was performed three times. b. Cryo-EM density map of the SCFFBXL17-KEAP1V98A complex. Dark gray: CUL11-450; light gray: SKP1; orange: FBXL17; blue: KEAP1. c. Despite an overlap in binding sites, CUL3 does not compete with SCFFBXL17 for substrate ubiquitylation. 35S-labeled wildtype or mutant KEAP1 were ubiquitylated by SCFFBXL17 in reticulocyte lysate either in the presence or absence of a CUL3 variant shown to bind BTB proteins. Ubiquitylated KEAP1 was detected by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. Three independent experiments were performed with similar results. d. SCFFBXL17 ubiquitylates full-length BTB proteins with Kelch repeats better than isolated BTB domains. 35S-labeled full-length KEAP1F64A, the BTB domain of KEAP1F64A, full-length KLHL12V50A, or the BTB domain of KLHL12V50A were incubated in reticulocyte lysate with recombinant FBXL17, and ubiquitylation was detected by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. Two independent experiments were performed with similar results. e. Full-length BTB proteins or isolated BTB domains bind similarly well to FBXL17. 35S-labeled full-length BTB proteins or isolated BTB domains, as indicated on the right, were incubated with immobilized MBPFBXL17 and bound proteins were detected by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. Two independent experiments were performed with similar results.

Extended Data Figure 4: Structural features of the SKP1/FBXL17-BTB complex.

a. Elution profile of the SKP1/FBXL17-BTB(KEAP1F64A) complex by size exclusion chromatography detecting A280. Control proteins with known MW are shown on top. This experiment was performed three times. b. FBXL17 binds to SKP1 via its F-box domain, in a manner highly similar to the LRR-domain containing F-box proteins SKP2 and FBXL3 20,21. The structures of SKP1-FBXL17, SKP1-SKP2, and SKP1-FBXL3 were aligned via SKP1. FBXL17 is shown in orange, SKP2 in magenta, and FBXL3 in yellow. c. FBXL17 uses conserved residues in its F-box to bind SKP1. The highlighted residues in FBXL17 (orange) that bind SKP1 (gray) were adopted from ref. 21. d. The substrate binding LRR domain of FBXL17 is longer and more curved than the LRR domains of SKP2 or FBXL3. Complexes were aligned via SKP1 (FBXL17, orange; SKP2, magenta; FBXL3, yellow). e. Structural models of BTB-FBXL17 complexes, using BTB domains that are similar in shape, but distinct in sequence. All complexes between FBXL17 and these confirmed substrates 2 can be formed without steric clashes. f. SKP1 and Elongin C, which also adopt BTB folds, cannot be bound to FBXL17, due to steric clashes shown in the insets.

Extended Data Figure 5: Validation of SKP1/FBXL17-BTB structure through FBXL17 mutations.

a. Single mutations of FBXL17 rarely affect co-translational recognition of KEAP1 in cells. FBXL17FLAG mutants were affinity-purified from 293T cells that also expressed MYCSKP1, HAKEAP1, and dominant negative CUL1 to prevent degradation of the BTB protein. Bound proteins were detected by gel electrophoresis and Western blotting. Red, mutations that abolish binding to FBXL17; orange, mutations that weaken binding to FBXL17; green, wild-type FBXL17; black: mutations that had no effect on KEAP1 binding. This experiment was performed once. b. Single mutations of FBXL17 rarely interfere with the proteasomal degradation of KEAP1. 293T cells were transfected with HAKEAP1 and either wild-type or mutant FBXL17FLAG, as denoted on the right, MYCSKP1, and dominant-negative CUL1 (dnCUL1), as indicated. The abundance of KEAP1 was monitored by gel electrophoresis and αHA-Western blotting. This experiment was performed once. c. The CTH is required, but not sufficient, for BTB recognition by SCFFBXL17. Immobilized recombinant MBP, MBPFBXL17, MBPFBXL17ΔCTH, or CTHMBP were incubated with 35S-labeled fused dimers of the BTB domains of KLHL12 (green) and KEAP1 (orange). Bound proteins were detected by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. This experiment was performed once. d. The CTH is required for in vitro ubiquitylation of mutant KEAP1. Recombinant FBXL17-SKP1 or FBXL17ΔCTH-SKP1 were added to reticulocyte lysate after the synthesis of either wild-type or mutant KEAP1. Reticulocyte lysate contains all other components required for in vitro ubiquitylation through SCFFBXL17. Unmodified and ubiquitylated KEAP1 were detected by gel electrophoresis and autoradiography. This experiment was performed once.

Extended Data Figure 6: Validation of SKP1/FBXL17-BTB structure through KEAP1 mutations.

a. Single mutations in KEAP1 do not inhibit the co-translational SCFFBXL17-dependent degradation of the BTB protein. 293T cells were transfected with either wild-type (left three lanes) or mutant HAKEAP1 (right two lanes; mutations denoted on the right), as well as MYCSKP1, FBXL17FLAG and dominant negative CUL1 (dnCUL1), as indicated on top. KEAP1 levels were monitored by gel electrophoresis and αHA Western blotting. This experiment was performed once. b. Single mutation of residues in KEAP1 at the interface with FBXL17 do not inhibit co-translational binding of the BTB protein to SCFFBXL17. 293T cells were transfected with wild-type or mutant HAKEAP1, MYCSKP1, FBXL17FLAG, and dominant-negative CUL1 (dnCUL1). FBXL17FLAG was affinity-purified and bound proteins were detected by gel electrophoresis and Western blotting. This experiment was performed once. c. Ala109 (red stick) in KEAP1 (blue) is positioned further from FBXL17 compared to the corresponding A60 residue in KLHL12 (green). KEAP1 and KLHL12 BTB domains were overlain bound to FBXL17 (KEAP1, actual structure; KLHL12, model).

Extended Data Figure 7: Sequence alignment of BTB domains.

Residues involved in BTB dimerization are marked by a blue dot; residues at the interface between the BTB domain and FBXL17 are marked by an orange dot; residues at the interface between the BTB domain and CUL3 are marked by a magenta dot. Sites of mutations used for X-ray crystallography or electron microscopy are marked by a red star.

Extended Data Figure 8: Binding and destabilization of BTB dimers by SCFFBXL17.

a. A FRET-based assay to monitor BTB dimer formation. Blue curve: The BTB domain of KEAP1F64A was labeled with Alexa 555, then denatured and refolded. Red curve: The BTB domain of KEAP1F64A was labeled with Alexa 647, then denatured and refolded. Green curve: Two separate BTB domain pools of KEAP1F64A were labeled with either Alexa 555 or Alexa 647, mixed in equimolar concentrations, denatured, and then refolded. ~50% of dimers are labeled with distinct fluorophores in each BTB subunit, giving rise to donor fluorescence quenching and acceptor emission as indication of FRET. Three independent experiments were performed with similar results. b. KEAP1F64A dimers dissociate very slowly and inefficiently. BTB domains of KEAP1F64A were labeled with either Alexa 555 or Alexa 647, respectively. The labeled BTB domains were then mixed, incubated overnight, and analyzed for FRET that results from stochastic rebinding of BTB monomers, leading to formation of BTB dimers containing one subunit labeled with Alexa 555 and the other subunit labeled with Alexa 647. However, in comparison to complex reformation by refolding (see above), little FRET was detected. This experiment was performed twice. c. FBXL17 can modulate BTB complex composition in vitro. The KLHL12 locus was tagged with a 3xFLAG epitope by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing. Endogenous KLHL123xFLAG complexes were affinity-purified from 293T cells and incubated with recombinant MBP (control), FBXL17, or inactive FBXL17ΔCTH. Proteins that remained bound to KLHL123xFLAG were determined by mass spectrometry. d. Overexpression of FBXL17ΔFBOX, which can bind but not ubiquitylate BTB proteins, prevents BTB heterodimerization. The endogenous KLHL123xFLAG was affinity-purified either in the presence or absence of FBXL17ΔFbox, and bound proteins were determined by mass spectrometry. e. FBXL17 can bind BTB dimers. FLAGKLHL12 was affinity-purified from 293T cells also expressing MYCKLHL12 and FBXL17HA. FLAGKLHL12 complexes were eluted with FLAG-peptide and FBXL17HA-containing complexes were then purified over αHA-agarose. Bound MYCKLHL12, indicative of FBXL17 associating with KLHL12 dimers, was then detected by Western blotting. This experiment was performed once. f. Binding of FBXL17 to BTB dimers requires its CTH to be disengaged from its binding site at the BTB dimer interface. A structural model of a KEAP1 BTB dimer bound to FBXL17 was generated using the KEAP1F64A dimer and the FBXL17-KEAP1F64A complex structures. Clashes are predominantly at the CTH of FBXL17. g. Residues of FBXL17, which in the structural model of a FBXL17-BTB dimer complex are in proximity to the leaving BTB subunit, contribute to stable substrate recognition. Indicated FBXL17 residues at the interface with the leaving BTB subunit (above) were mutated in the sensitized background of the FBXL17C680D variant and analyzed for binding to endogenous BTB proteins by affinity purification and Western blotting. This experiment was performed once.

Extended Data Figure 9: The amino-terminal β-strand is important for BTB complex formation and recognition.

a. Chimeric KLHL12 with β-strand and adjacent dimer interface residues of KEAP1, but not wild-type KLHL12, forms heterodimers with KEAP1 in vivo. 293T cells were transfected with KLHL12FLAG (wild-type or chimera) and KLHL12HA or HAKEAP1, as indicated. KLHL12FLAG variants were immunoprecipitated and bound proteins detected by gel electrophoresis and Western blotting. This experiment was performed once. b. BTB heterodimers are inactive in signaling. 293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged wild-type KLHL12, chimeric KLHL12, or wild-type KEAP1. The FLAG-tagged BTB proteins were affinity-purified and bound endogenous targets of KLHL12 (SEC31, PEF1, ALG2) or KEAP1 (NRF2) were detected by Western blotting. This experiment was performed once. c. A chimeric KLHL12 that contains helix and β-strand residues of KEAP1 efficiently heterodimerizes with KEAP1, yet fails to bind substrates of either KLHL12 or KEAP1. KLHL12FLAG, chimeric KLHL12FLAG or KEAP1FLAG were affinity-purified from 293T cells and bound proteins were determined by CompPASS mass spectrometry.

Extended Data Figure 10: The amino-terminal β-strand of BTB domains serves as a molecular barcode for functional dimerization.

Sequence alignment of amino-terminal β-strands across human BTB domains shows divergence, indicative of rapid evolution of this protein sequence.

Extended Data Table 1: Data collection and refinement statistics for crystal structures.

Table shows crystallography refinement data. Values in parentheses are for highest resolution shell.

| KEAR1BTB | KEAP1BTB F64A | KEAP1BTB V98A | KEAP1BTB F64A - FBXL17 - SKP1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||

| Beamline | ALS 8.3.1 | ALS 8.3.1 | ALS 8.3.1 | ALS 8.3.1 |

| Space Group | P6822 | P6822 | P6822 | P3221 |

| Cell dimensions | ||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 42.68, 42.68, 266.24 | 42.64, 42.64, 264.85 | 42.62, 42.62, 268.46 | 183.6, 183.6, 55.4 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 120 |

| Resolution (Å) | 44.37-2.20 (2.27-2.20) | 44.14-2.50 (2.60-2.50) | 36.91-2.55 (2.66-2.55) | 159.06-3.207 (3.43-3.21) |

| No. unique reflections | 8147 (772) | 5502 (448) | 5358 (522) | 17739 (1711) |

| Rmerge | 0.198 (3.835) | 0.172 (1.878) | 0.167 (3.271) | 0.289 (4.145) |

| I/σI | 16.1 (1.1) | 11.3 (1.0) | 11.9 (0.8) | 7.6 (0.7) |

| CC1/2 | 1 (0.713) | 1 (0.617) | 1 (0.405) | 1 (0.452) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.78 (99.61) | 97.95 (86.99) | 99.39 (98.10) | 98.44 (89.46) |

| Redundancy | 24.5 (26.4) | 11.8 (8.2) | 9.6 (9.5) | 10.6 (10.2) |

| Refinement | ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 44.37-2.20 (2.28-2.20) | 44.14-2.50 (2.59-2.50) | 36.91-2.55 (2.64-2.55) | 79.529-3.207 (3.32-3.21) |

| No. reflections | 8129 (769) | 5493 (447) | 5349 (516) | 17524 (1579) |

| Rwork | 0.2382 (0.3330) | 0.2331 (0.2878) | 0.2543 (0.4043) | 0.2456 (0.4179) |

| Rfree | 0.3053 (0.4307) | 0.2929 (0.3545) | 0.3114 (0.4334) | 0.2891 (0.4232) |

| No. atoms | 1029 | 1017 | 1015 | 5219 |

| Protein | 1006 | 1000 | 1012 | 5219 |

| Ligand/ion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Water | 23 | 17 | 3 | 0 |

| Wilson B factor (Å2) | 46.52 | 51.83 | 66.68 | 101.91 |

| Average B factor (Å2) | 55.82 | 55.33 | 69.61 | 122.25 |

| Protein | 55.96 | 55.47 | 69.66 | 122.25 |

| Water | 49.81 | 47.33 | 51.36 | - |

| R.M.S deviations | ||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.0069 | 0.0015 | 0.0039 | 0.0018 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.85 | 0.44 | 1.01 | 0.43 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||||

| Favored [%] | 97.64 | 100 | 96.06 | 90.78 |

| Allowed [%] | 2.36 | 0 | 2.36 | 8.76 |

| Outliers [%] | 0 | 0 | 1.80 | 0.46 |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Charlotte Nixon, Shawn Costello, and Susan Marqusee for their generous help with CD, the Andreas Martin lab for their help with FRET, and Laura Nocka for help with SEC-MALS. We thank Fernando Rodriguez Perez for help with R. We thank Avinash Patel and Dan Toso for help with graphene oxide grid preparation and cryo-EM data collection, respectively. We thank James Holton and George Meigs at the Advanced Light Source Beamline 8.3.1 for assistance with data collection. Beamline 8.3.1 at the Advanced Light Source is operated by the University of California Office of the President, Multicampus Research Programs and Initiatives grant MR-15-328599, the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM124149 and P30 GM124169), Plexxikon Inc. and the Integrated Diffraction Analysis Technologies program of the US Department of Energy Office of Biological and Environmental Research. The Advanced Light Source (Berkeley, CA) is a national user facility operated by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory on behalf of the US Department of Energy under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. We thank Julia Schaletzky for her comments on the manuscript. We also grateful to members of the Rape, Nogales, and Kuriyan labs for discussion and suggestions. ELM was funded by an NSF predoctoral scholarship (ID 2013157149). BJG was supported by fellowships from the Swiss National Science Foundation (projects P300PA_160983, P300PA_174355). DA was funded by an NIH F32 postdoctoral fellowship. EN, JK, and MR are Investigators with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement

The atomic coordinates of the CUL1-SKP1-FBXL17-KEAP1(V99A) complex has been deposited to Protein Data Bank with accession number 6WCQ. The respective cryo-EM map has been deposited to the Electron Microscopy Data Bank with accession number EMD-21617. The atomic coordinates of the X-ray crystal structures have been deposited to the Protein Data Bank with the following accession numbers: 6W66 (KEAP1-S172A/F64A-FBXL17-SKP1 complex), 6W67 (KEAP1-S172A), 6W68 (KEAP1-S172A/V98A), and 6W69 (KEAP1-S172A/F64A). All source data for Western blots can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Competing interests

M.R. and J.K. are founders and consultants of Nurix, a biotechnology company working in the ubiquitin field.

References

- 1.Balchin D, Hayer-Hartl M & Hartl FU In vivo aspects of protein folding and quality control. Science 353, aac4354, doi: 10.1126/science.aac4354 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mena EL et al. Dimerization quality control ensures neuronal development and survival. Science 362, doi: 10.1126/science.aap8236 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordley RM, Bugaj LJ & Lim WA Modular engineering of cellular signaling proteins and networks. Curr Opin Struct Biol 39, 106–114, doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2016.06.012 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ji AX & Prive GG Crystal structure of KLHL3 in complex with Cullin3. PLoS One 8, e60445, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060445 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhuang M et al. Structures of SPOP-substrate complexes: insights into molecular architectures of BTB-Cul3 ubiquitin ligases. Molecular cell 36, 39–50, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.022 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cleasby A et al. Structure of the BTB domain of Keap1 and its interaction with the triterpenoid antagonist CDDO. PLoS One 9, e98896, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098896 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghetu AF et al. Structure of a BCOR corepressor peptide in complex with the BCL6 BTB domain dimer. Mol Cell 29, 384–391, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.026 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGourty CA et al. Regulation of the CUL3 Ubiquitin Ligase by a Calcium-Dependent Co-adaptor. Cell 167, 525–538 e514, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.026 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werner A et al. Cell-fate determination by ubiquitin-dependent regulation of translation. Nature 525, 523–527, doi: 10.1038/nature14978 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin L et al. Ubiquitin-dependent regulation of COPII coat size and function. Nature 482, 495–500, doi: 10.1038/nature10822 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furukawa M & Xiong Y BTB protein Keap1 targets antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2 for ubiquitination by the Cullin 3-Roc1 ligase. Mol Cell Biol 25, 162–171, doi:25/1/162 [pii] 10.1128/MCB.25.1.162-171.2005 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wakabayashi N et al. Keap1-null mutation leads to postnatal lethality due to constitutive Nrf2 activation. Nat Genet 35, 238–245, doi: 10.1038/ng1248 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louis-Dit-Picard H et al. KLHL3 mutations cause familial hyperkalemic hypertension by impairing ion transport in the distal nephron. Nat Genet 44, 456–460, S451–453, doi: 10.1038/ng.2218 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maerki S et al. The Cul3-KLHL21 E3 ubiquitin ligase targets aurora B to midzone microtubules in anaphase and is required for cytokinesis. The Journal of cell biology 187, 791–800, doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906117 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sumara I et al. A Cul3-based E3 ligase removes Aurora B from mitotic chromosomes, regulating mitotic progression and completion of cytokinesis in human cells. Dev Cell 12, 887–900, doi:S1534-5807(07)00119-0 [pii] 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.019 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duan S et al. FBXO11 targets BCL6 for degradation and is inactivated in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Nature 481, 90–93, doi: 10.1038/nature10688 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan MK, Lim HJ, Bennett EJ, Shi Y & Harper JW Parallel SCF adaptor capture proteomics reveals a role for SCFFBXL17 in NRF2 activation via BACH1 repressor turnover. Mol Cell 52, 9–24, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.018 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto M, Kensler TW & Motohashi H The KEAP1-NRF2 System: a Thiol-Based Sensor-Effector Apparatus for Maintaining Redox Homeostasis. Physiol Rev 98, 1169–1203, doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2017 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng N et al. Structure of the Cul1-Rbx1-Skp1-F boxSkp2 SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. Nature 416, 703–709, doi: 10.1038/416703a (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xing W et al. SCF(FBXL3) ubiquitin ligase targets cryptochromes at their cofactor pocket. Nature 496, 64–68, doi: 10.1038/nature11964 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulman BA et al. Insights into SCF ubiquitin ligases from the structure of the Skp1-Skp2 complex. Nature 408, 381–386, doi: 10.1038/35042620 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhattacharyya M et al. Molecular mechanism of activation-triggered subunit exchange in Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Elife 5, doi: 10.7554/eLife.13405 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pierce NW et al. Cand1 promotes assembly of new SCF complexes through dynamic exchange of F box proteins. Cell 153, 206–215, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.024 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reitsma JM et al. Composition and Regulation of the Cellular Repertoire of SCF Ubiquitin Ligases. Cell 171, 1326–1339 e1314, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.016 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X et al. Cand1-Mediated Adaptive Exchange Mechanism Enables Variation in F-Box Protein Expression. Mol Cell 69, 773–786 e776, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.01.038 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu S et al. CAND1 controls in vivo dynamics of the cullin 1-RING ubiquitin ligase repertoire. Nat Commun 4, 1642, doi: 10.1038/ncomms2636 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zemla A et al. CSN- and CAND1-dependent remodelling of the budding yeast SCF complex. Nat Commun 4, 1641, doi: 10.1038/ncomms2628 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Supplemental References

- 28.Duda DM et al. Structural insights into NEDD8 activation of cullin-RING ligases: conformational control of conjugation. Cell 134, 995–1006, doi:S0092-8674(08)00942-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.022 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kabsch W Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 125–132, doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans PR & Murshudov GN How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 69, 1204–1214, doi: 10.1107/S0907444913000061 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winn MD et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67, 235–242, doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams PD et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 213–221, doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG & Cowtan K Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 486–501, doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DiMaio F et al. Improved low-resolution crystallographic refinement with Phenix and Rosetta. Nat Methods 10, 1102–1104, doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2648 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morin A et al. Collaboration gets the most out of software. Elife 2, e01456, doi: 10.7554/eLife.01456 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grimsley GR, Huyghues-Despointes BM, Pace CN & Scholtz JM Preparation of urea and guanidinium chloride stock solutions for measuring denaturant-induced unfolding curves. CSH Protoc 2006, doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4241 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonald SK & Fleming KG Aromatic Side Chain Water-to-Lipid Transfer Free Energies Show a Depth Dependence across the Membrane Normal. J Am Chem Soc 138, 7946–7950, doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03460 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tivol WF, Briegel A & Jensen GJ in Microsc. Microanal Vol. 14 375–379 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mastronarde DN in Journal of Structural Biology Vol. 152 36–51 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schorb M, Haberbosch I, Hagen WJH, Schwab Y & Mastronarde DN Software tools for automated transmission electron microscopy. Nat Meth 16, 471–477 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng SQ et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Meth 14, 331–332 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biyani N et al. Focus: The interface between data collection and data processing in cryo-EM. J. Struct. Biol 198, 124–133 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zivanov J et al. New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. Elife 7, e42166 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang K Gctf: Real-time CTF determination and correction. J. Struct. Biol 193, 1–12 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rohou A & Grigorieff N in Journal of Structural Biology Vol. 192 216–221 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ & Brubaker MA in Nat Meth Vol. 14 290–296 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]