Abstract

This study tested whether a child sexual abuse (CSA) prevention program, Smart Parents-Safe and Healthy Kids (SPSHK), could be implemented as an additional module in evidence-based parent training and whether the added module might detract from the efficacy of the original program. In a cluster randomized trial, six community-based organizations were randomized to deliver Parents as Teachers (PAT) with SPSHK (PAT+SPSHK) or PAT as usual (PAT-AU). CSA-related awareness and protective behaviors, as well as general parenting behaviors taught by PAT were assessed at baseline, post-PAT, post-SPSHK, and 1-month follow-up. Multilevel analyses revealed significant group by time interactions for both awareness and behaviors (ps < .0001), indicating the PAT +SPSHK group had significantly greater awareness of CSA and used protective behaviors more often (which were maintained at follow-up) compared to the PAT-AU group. No differences were observed in general parenting behaviors taught by PAT suggesting adding SPHSK did not interfere with PAT efficacy as originally designed. Results indicate adding SPHSK to existing parent training can significantly enhance parents’ awareness of and readiness to engage in protective behavioral strategies. Implementing SPHSK as a selective prevention strategy with at-risk parents receiving parent training through child welfare infrastructures is discussed.

Keywords: prevention, child sexual abuse, parenting, intervention science

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is a global public health problem affecting one in five women and one in 12 men before age 18 (Stoltenborgh et al., 2011). In the U.S., the most recent national prevalence rates indicate 63,000 children were victims of CSA in 2018 alone (DHHS, 2020; Finkelhor et al., 2020). An adverse childhood experience, CSA is associated with lifelong adverse mental health (Bebbington et al., 2009; Dube et al., 2005), physical health (Daigneault et al., 2017; Noll et al., 2007, 2017), and behavioral health (Barnes et al., 2009; Noll et al., 2018; Noll & Shenk, 2013) outcomes and is known to have intergenerational effects (Bartlett et al., 2017; Kwako et al., 2010; Trickett et al., 2011). Accounting for productivity losses as well as healthcare, education, child welfare, and criminal justice costs, the lifetime economic burden of CSA is estimated to exceed $9.3 billion (Letourneau et al., 2018). Between 1990 and 2017, rates of CSA declined 62% (Finkelhor et al., 2019); however, reasons for this decline are not well understood. It is likely primary prevention efforts, beginning in earnest in the 1980s, contributed to the reduction by raising public awareness about the signs of and how to respond to abuse. Importantly, this decline notably plateaued over the past decade, and prevalence estimates from 2018 indicate that rates of CSA in the U.S. may be on the rise (Finkelhor et al., 2020).Given the individual and societal costs of CSA exposure and increasing prevalence rates, effective CSA primary prevention strategies are urgently needed.

Historically, CSA primary prevention efforts have predominantly focused on teaching personal safety skills to school-aged children (Jin et al., 2019; Pulido et al., 2015) with the purpose of strengthening children’s knowledge and skills to prevent victimization. Some of these preventive efforts rely on parents to serve as the teacher, directly convey safety skills to children which is problematic as parents are uncomfortable talking to their children about sex, even when they have the knowledge and intentions to do so (Rudolph & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2018a; Xie et al., 2016). Criticisms of child-focused strategies include the complexity of concepts for young children (Wurtele, 2009), difficulty for children to challenge authority (i.e., adults) leading to a report of abuse (Rudolph & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2018b), as well as an inconclusive direct effect on disclosures (Walsh et al., 2018; White et al., 2018). Primary prevention efforts also have targeted adults of the general community by raising CSA awareness, challenging social norms, and increasing knowledge about how to recognize signs of CSA (Rheingold et al., 2015). Child-focused and community-based efforts have similarly failed to empirically demonstrate an effect on rates of CSA. Responsibility to prevent CSA cannot fall on only one group, especially children, and it is unlikely one strategy focused at one segment of the population will affect rates of CSA (Wandersman & Florin, 2003). Broadening the scope of CSA primary prevention efforts will increase the odds of impacting overall CSA rates. A comprehensive CSA prevention strategy adopting a public health approach would include efforts at individual, relational, community, and societal levels. Notably absent from prevailing primary CSA prevention are parent-focused strategies. Leading researchers suggest that parents, situated at the relational level of a comprehensive strategy, have a notable influence on youth behavior and are most proximal to and are most aware of their children’s environments (Mendelson & Letourneau, 2015; Rudolph et al., 2018). This paper describes a parent-focused CSA prevention strategy that, when included in a comprehensive prevention strategy, will increase the potential to decrease rates of CSA.

Parents as Agents of Prevention

Incorporating parent-focused strategies into prevention efforts has empirical precedence across several public health issues affecting children including substance use (Dishion et al., 2002) and delinquency (Mason et al., 2003). Further, parents are the primary foci of programs designed to prevent other forms of maltreatment (i.e., physical abuse and neglect) and some programs have achieved the gold standard of reducing rates of those forms of maltreatment (Chaffin et al., 2012; Prinz et al., 2009; Reid & Webster-Stratton, 2001). The effects of generalized parent training programs on rates of CSA has been negligible (Selph et al., 2013), which is not surprising given these programs do not include content specific to CSA prevention such as healthy sexual development, strategies for parents to use when discussing sex or sexual behaviors, internet safety, or vetting a babysitter. Moreover, there is considerable evidence that CSA has a unique etiology. For example, CSA is less likely to be perpetrated by family members with 64% of perpetrators being non-familial (Finkelhor & Shattuck, 2012), as compared to 28% and 8% for perpetrators of physical abuse and neglect, respectively (Sedlak et al., 2010). The age of elevated risk for CSA also differs, the median age being 9 years old (Sedlak et al., 2010) in contrast to 3 years old for physical abuse and neglect (DHHS, 2020). Whereas physical abuse and neglect stem from parental behavior deficits, CSA is a product of opportunity and exploitation occurring most commonly in environments where children are unsupervised (Snyder, 2000). Whereas neglect may be evident from observation of children’s physical environments or appearance, and physical abuse may be proven by bodily injuries, there are not always outward signs of CSA. Instead, CSA detection commonly requires explicit disclosure by the victim (Paine & Hansen, 2002), which is not always immediate, sometimes surpassing 20 years (Jonzon & Lindblad, 2004).

Despite high rates of co-occurrence with other maltreatment types (Finkelhor et al., 2020; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2013; Vachon et al., 2015), the unique features of CSA (Noll et al., 2018) necessitate a nuanced parent-focused prevention approach. For example, CSA prevention requires parents to monitor the access that others have to their children both online and in-person given that most perpetrators are known by the victim and/or trusted by the family (Snyder, 2000). Parents must also be knowledgeable about child development, age appropriate behaviors, and affect, as changes to a child’s developmental trajectory (e.g., normative and non-normative sexual developmental milestones) may suggest the child is being exploited sexually (Hornor, 2004). An involved, trusting relationship between parent and child which facilitates open discussion and disclosure can reduce the potential for and severity of victimization (Leclerc et al., 2015). Parents are uniquely equipped to foster self-efficacy, thus rendering their children more difficult targets for victimization.

Existing Parent-Focused CSA Education

A small number of existing parent-focused CSA primary prevention efforts have relied on teaching parents to educate their children about CSA and encouraging the use of protective behaviors such as saying “no” or trying to create distance from a potential perpetrator by running away. Empirical, peer reviewed studies evaluating these parent-focused strategies are sparse and results are mixed. Berrick (1988) examined the effect of a single session focused on knowledge related to the prevalence of CSA, indications of abuse, and appropriate responses to abuse. No significant changes in a convenience sample of 118 parents’ knowledge were identified in the pre-post-test assessment and participation in the session was notably low (i.e., only 34% of eligible parents attended). The work of Wurtele and colleagues has perhaps been the most informative. In one pilot study, Burgess and Wurtele (1998) demonstrated parents randomized to watch a 30-minute video with actors modeling how to calmly discuss sexuality and how to appropriately handle a CSA disclosure had significantly greater intentions of talking to their child about CSA compared to parents who watched a general home safety video. Another study indicated a singular 3-hour in-person workshop conducted by a CSA-prevention expert significantly improved parents’ self-reported knowledge and discussions with their children about CSA (Wurtele et al., 2008). Though dated, these studies demonstrate the feasibility of affecting parent CSA-related knowledge in one session but were not evaluated using a fully powered randomized controlled trial and some were designed without a comparison group (e.g., Berrick, 1988; Wurtele et al., 2008). Additionally, programs were evaluated solely on the degree to which parents had—or their intention to have—a discussion about CSA with their child but did not assess changes in protective behaviors and therefore it is unknown if these programs affected parents’ use of protective behaviors or if these parents were using protective behaviors prior to the program. Although there is theoretical and modest empirical support for the inclusion of parents in the primary prevention of CSA, it is unknown whether targeting all parents universally is warranted or whether there might be a subset of parent who would benefit more than others. In a review of universal child and adolescent prevention programs designed to improve mental health, Dodge (2020) demonstrates that the net cost savings of programs is highest among programs delivered to individuals at highest risk. Not only is the efficacy of existing parent-focused CSA prevention programs inconsistent, the allocation of resources via a universal prevention strategy may not cost-effective nor sustainable.

Toward an Efficient, Sustainable, Selective Approach to CSA Prevention

Whereas universal prevention strategies involve everyone in a population (e.g., all parents of school-aged kids), selective prevention strategies focus efforts on individuals with elevated or high risk but who have not yet experienced the outcome of interest (Rae Grant, 1994). A selective prevention programs increase cost-effectiveness by targeting a subset of the population that are deemed at-risk based on membership in a specific segment of the population. For example, children of parents with substance use disorder are at risk of engaging in substance use themselves (Lipari & Van Horn, 2017). A selective prevention approach is designed to mitigate the development of an adverse outcome among that subgroup (Institute of Medicine, 1994). Extending the previous example, a selective prevention approach might be delivered as a school-based program for elementary students from drug-involved families that focuses on emotional and behavioral strategies for coping with difficult situations that might ultimately lead to a child’s substance use (see Bröning et al., 2012). Selective approaches efficiently allocate resources to those at-risk, among whom change in risk factors is most likely to occur, and, thus, present a cost effective prevention approach (Dodge, 2020). Because they bear the additional cost burden associated with screening, it behooves selective approaches to leverage existing systems to efficiently and effectively funnel those at highest risk into preventive interventions.

Identifying a subgroup of children and families at-risk for CSA is complicated, as many risk factors are simultaneously associated with other types of child maltreatment such as physical abuse and neglect (Stith et al., 2009), such as parental substance use (Davies & Jones, 2013), parenting deficits (e.g., absence, lack of supervision; Finkelhor & Baron, 1986), and parental history of victimization (Finkelhor et al., 1997; McCloskey & Bailey, 2000). A meta-analysis of 72 studies reported the strongest risk factors for CSA included: parent history of childhood victimization (r = .27); parenting problems (i.e., poor relationship; r = .29); and social isolation (r = .20; Assink et al., 2019). Risk for CSA is also significantly heighted by exposure to other forms of maltreatment and involvement with the child welfare system (Laaksonen et al., 2011; Palusci & Ilardi, 2020). Taken together, these studies of associated CSA risk-factors suggest that there are some home environments in which CSA occurs more frequently than others, namely those where parents could benefit from increased support, where there is a need for parenting skills enhancement, or when the family has had contact with the child welfare system. Because these are the households in which CSA is most likely to occur, targeting such home environments holds promise for reducing the risk of CSA. Families who are accepted for services within the child welfare system exemplify these high-risk households. As such, engaging parents receiving services within the child welfare system is a viable option for a selective approach to the primary prevention of CSA that would eliminate the cost of screening.

As with other prevention approaches delivered to at-risk parents, in a selective prevention program it will be important to overcome the problem of parental engagement (Guastaferro et al., 2018). For example Berrick (1988) reported a 19% attrition rate between pre-and post-test in addition to a low initial participation rate. Rather than offering a standalone program, it may be beneficial to add CSA prevention content to parent training programs, such as those included in the 2018 Family First Prevention Service Act, with which many at-risk or child welfare-involved parents are already engaged (Mendelson & Letourneau, 2015). CSA-specific prevention skills and protective behaviors are reinforced by fundamental parenting skills and concepts taught in parent training programs, which focus on child-development, strategies to improve parent-child interactions and communication as well as strategies to reduce problematic child behaviors (Lundahl et al., 2006; Timmer & Urquiza, 2014). Parents need to know how to create safe environments where CSA is less likely to occur, how to identify normative and nonnormative sexual development, and how to communicate with children about sexual topics that will increase their perception of danger cues as well as behavioral and physical signs of CSA. An additive and complementary to existing parenting training approaches could easily be leveraged into the implementation infrastructure of child welfare systems. Such an approach would maximize the potential for dissemination and scale-up without additional resources.

A CSA-specific parent education module, Smart Parents—Safe and Healthy Kids (SPSHK), was developed to leverage the evidence-based content of parent training programs by adding three key CSA-prevention components; healthy child sexual development, parent-child communication about sex and sexual behaviors, and CSA-specific safety strategies such as vetting a babysitter and monitoring one-on-one time with adults (Guastaferro et al., 2019). Behaviorally based, the module presents developmentally comprehensive information to parents of children 0–13 and utilizes role-playing scenarios and activities to maximize parents’ use of learned skills. For example, in the healthy sexual development component, parents learn about healthy sexual development and practice answering questions about sexual development (i.e., “where do babies come from?”) in a developmentally appropriate manner for the age of their child. Because the module builds upon the foundational skills of general parent training programs, SPSHK is delivered in one session added to the general parenting training program. An acceptability and feasibility pilot study confirmed the module could be delivered within a single session (~ 60 minutes) and the content and presentation of information were satisfactory to providers and parents (Guastaferro et al., 2019). In open-ended questions, providers reiterated their willingness to include the module referencing the lack of this information in the programs they currently deliver and the needs of the parents they serve.

The Current Study

The current study sought to examine the effectiveness of SPSHK on parents’ CSA-related awareness and use of protective behavior strategies when added to an existing evidence based parent training program. Parents as Teachers (PAT) is widely disseminated to parents of children under five and focuses on improving parenting skills by strengthening parent-child interactions, encouraging development centered parenting, and enhancing general family well-being. PAT is delivered in biweekly or monthly sessions (based on risk level) and includes group connections, health screenings, and referrals to resource networks. PAT has demonstrated positive effects on child and parent outcomes related to school readiness (Zigler et al., 2008) and is often used to address general parenting skills among those who have come into contact with the child welfare system. In addition to child welfare involvement, parents may become involved with PAT through schools or community-based referrals (e.g., placement services, substance use services, or voluntarily).

Using a cluster randomized experimental design, the current study compared the effect of SPSHK added to PAT (PAT+SPSHK) to PAT as usual (PAT-AU). It was hypothesized that parents who received PAT+SPSHK would have greater awareness about how to recognize signs of and prevent CSA and would engage in protective behaviors (i.e., monitoring one-on-one time between child and adults, vetting babysitters) to a greater degree than parents who received PAT-AU, and that gains would be maintained 1 month post-intervention. Since it is important that adding additional content to existing interventions does not alter the efficacy of the evidence-based intervention, a secondary objective of this study was to demonstrate that adding SPSHK not negatively impact the efficacy of PAT.

Method

Setting and Participants

A cluster randomized trial was conducted in cooperation with community-based agencies delivering PAT within the child welfare system of a large mid-Atlantic state which has a large pre-existing statewide implementation infrastructure to support PAT program fidelity. Eligible parents—broadly defined to include biological, adoptive, foster, and step parents as well as parents’ partners, or other adult relatives—were currently enrolled in PAT, over 18 years old, and the parent to a child <5. One parent per household participated in the research.

A total of 110 parents consented to participate and completed the baseline assessment (Table 1). The sample was predominantly female (95%), White (96%), and single or unmarried (51%). The mean age of participants was 31 (SD=8.6; range 19–73). The largest proportion of the sample had completed high school or obtained a GED (47%), but 12% of the sample did not complete high school. Slightly over a quarter (28%) of respondents reported an annual income <$5,000 and another quarter (24%) reported an annual income ≥ 40,000. The majority (79%) of the sample reported receiving at least some aid, most commonly WIC and/or Medicaid. Participants reported being a parent to an average of 2.5 children under 5. There were statistically significant (p < .05) differences on some characteristics between groups (Table 1) that were controlled for in analytic models.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Baseline.

| Total (N = 110) | PAT-AU (n = 63) | PAT+SPSHK (n = 47) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | P value | |

| Femalea | 104 | (95) | 58 | (92) | 46 | (100) | .05 |

| Hispanic | 3 | (3) | 2 | (3) | 1 | (2) | .74 |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 106 | (96) | 59 | (94) | 47 | (100) | .08 |

| Black | 1 | (1) | 1 | (2) | 0 | (0) | .38 |

| Single | 56 | (51) | 38 | (60) | 18 | (38) | .02 |

| Educational Attainment | |||||||

| Less than high school | 13 | (12) | 11 | (17) | 2 | (4) | .03 |

| High school or GED | 52 | (47) | 30 | (48) | 22 | (47) | .93 |

| Some college | 22 | (20) | 14 | (22) | 8 | (17) | .50 |

| College graduate or advanced degree | 23 | (21) | 8 | (13) | 15 | (32) | .01 |

| Income | |||||||

| ≤ $4,999 | 29 | (28) | 20 | (35) | 9 | (20) | .09 |

| $5,000–14,999 | 21 | (21) | 16 | (28) | 5 | (11) | .04 |

| $15,000–19,999 | 10 | (10) | 6 | (11) | 4 | (9) | .78 |

| $20,000–29,999 | 11 | (11) | 6 | (11) | 5 | (11) | .92 |

| $30,000–39,999 | 7 | (7) | 2 | (4) | 5 | (11) | .13 |

| ≥ $40,000 | 24 | (24) | 7 | (12) | 17 | (38) | .003 |

| Receiving Aid | 87 | (79) | 57 | (90) | 30 | (64) | < .001 |

| M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | P value | |

| Parent Age | 31 | (8.6) | 28 | (5.5) | 34 | (10.8) | .001 |

| Age when first child born | 23 | (5.2) | 22 | (4.5) | 24 | (5.9) | .05 |

| # of Kids ≤ 5 years old | 2.5 | (1.2) | 2.6 | (1.2) | 2.3 | (1.1) | .23 |

| Alcohol Use | 0.9 | (1.0) | 1.0 | (1.2) | 0.8 | (0.8) | .27 |

| Drug Use | 0.2 | (0.5) | 0.3 | (0.6) | 0.2 | (0.4) | .22 |

| Depression | 9.5 | (6.6) | 10.4 | (6.9) | 8.1 | (6.0) | .07 |

| Interpersonal Support | 21.0 | (3.5) | 20.4 | (3.8) | 21.8 | (2.9) | .04 |

KEY: PAT = Parents as Teachers; AU = As Usual; SPSHK = Smart Parents-Safe and Healthy KidsProcedure.

Due to participants’ ability to skip questions there is varied missingness across items.

The PAT model includes a parent group connection element and supervision of providers may be provided in a group setting. For these reasons, randomization occurred at the agency level to reduce the potential for contamination. Of 36 sites approached, 6 agreed to participate. Most sites (n = 26) never responded to recruitment communications, but among the 4 sites that directly declined participation the reasons provided included funding cuts or recent staff turnover. The 6 sites were randomized to PAT-AU (N = 3) or PAT+SPSHK (N = 3).

Provider training.

Providers in the PAT+SPSHK group were sent a link for a 20-minute webinar which reviewed the pedagogical approach, structure of the materials, and goals of SPSHK. One week after the webinar was distributed, providers attended a 4-hour in-person workshop at their agency led by members of the research team. In the workshop the curriculum was first explained and modeled by the research team trainers, then providers practiced delivering the module to each other with corrective feedback provided from the trainers.

Experimental procedure.

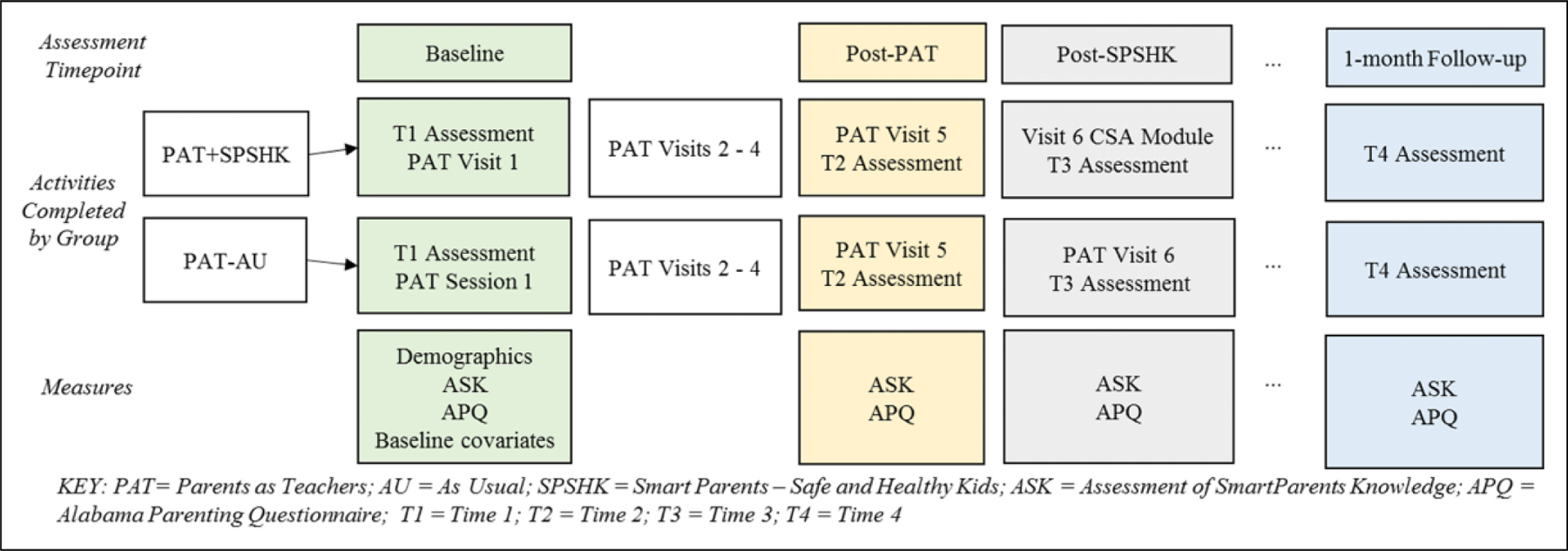

Parents were invited to participate in the study and consented by their provider during a scheduled PAT visit. In consultation with the PAT National Center, parents were eligible to receive SPHSK after receiving at least five foundational visits during which parents learn the core parenting behaviors corresponding to the content of the CSA module. Providers were able to recruit any parent on their caseload, meaning the duration of PAT program involvement prior to study enrollment varied by participant. Note visit is used to describe contact, but not indicative of what content a parent received. Participation was voluntary and had no impact on the parents’ eligibility to receive PAT services. Figure 1 depicts the schedule of assessment timepoints (Baseline [T1], Post-PAT [T2], Post-SPSHK [T3], and 1-month follow-up [T4]), the activities completed at each assessment point (i.e., visit) by group, and measures asked at each assessment. Consent encompassed both the assessments and the added module.Following consent, at baseline parents in PAT+SPSHK and PAT-AU groups completed the T1 assessment and received a PAT visit. PAT was then implemented as planned for Visits 2–4. By the Post-PAT assessment, Visit 5, parents received the core parenting skills upon which the concepts in the SPSHK curriculum relies. In the Post-PAT assessment, parents in both groups completed the PAT visit as planned and the T2 assessment. At subsequent visit, Visit 6, parents in the PAT+SPSHK group received the SPSHK module and completed the T3 assessment. At Visit 6, parents in the PAT-AU group received the PAT visit as planned and completed the T3 assessment. Implementation of PAT visits as planned continued for both groups. One-month post Visit 6, parents in PAT+SPSHK and PAT-AU groups completed the T4 assessment during their scheduled visit. The T1 survey took participants ≥25 minutes to complete and all other assessments <10 minutes to complete. All assessments were conducted via paper survey which were later double entered by research assistants into REDCap® (Harris et al., 2009). Parents received a small monetary incentive for each survey completed and the university institutional review board approved all procedures.

Figure 1.

Assessment timeline and measure schedule for cluster randomized trial.

Measures

Participant characteristics.

At baseline (Figure 1), participants provided demographic information including: gender, race, marital status, level of educational attainment, income, receipt of aid (e.g., WIC, TANF), age, age at birth of first child, and the household constellation (e.g., number of children, number of adults in the home). Based on the premise that parent training programs reduce risk for maltreatment broadly, at baseline parents completed four questionnaires related to well-documented risk-factors for maltreatment, including CSA: alcohol use, drug use, depression, and interpersonal support (Duffy et al., 2015; Kelley et al., 2015; Palusci, 2011; Stith et al., 2009). Participants completed the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993). The 10 AUDIT items are summed to create an overall measure of hazardous drinking; a score ≥ 8 indicates an alcohol use problem. To ascertain drug use (i.e., illicit drugs), participants completed the 10-item self-report Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10; Skinner, 1982). Each endorsed item receives one point such that a DAST score of 0 indicates no drug problem; 1–2 low level; 3–5 moderate level; and ≥ 6 substantial or severe. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD) is a 20-item self-report assessment of depressive symptoms experienced in the prior week (Radloff, 1977); a score ≥ 16 indicates a clinical level of depressive symptoms. To ascertain perceived interpersonal support, participants completed the 12-item Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL; Cohen et al., 1985). A higher score (range 0–36) reflects highly perceived availability of support. These characteristics were used to describe the sample in terms of risk and were treated as covariates in analytic models when group differences were observed.

Outcomes.

The primary outcome of interest was change in parents’ self-reported knowledge of CSA and positive attitudes toward CSA prevention, operationally defined henceforth as “awareness,” and the use of protective behaviors to limit risk for CSA. The Assessment of SmartParent’s Knowledge (ASK) questionnaire, developed and evaluated psychometrically in concert with the SPSHK curriculum (Guastaferro et al., 2019), is a reliable and valid measure comprised of two factors: awareness and behaviors. The awareness factor (9-items; αt1 = 53) assesses parents’ knowledge of general facts about CSA (e.g., “Most sexual abuse victims are abused by someone they know”) and the perception of their role in prevention (e.g., “As a parent, I am the best person to teach my child about preventing sexual abuse”). The behavior factor (6-items; αt1 = .77) assesses parents’ behaviors regarding CSA prevention including skills to identify signs of CSA (e.g., “I know what signs to look for that suggest my child may have been sexually abused”) and talking to their child (e.g., “I have talked to my child about how to protect him/herself from being sexually abused”). The 15-items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) such that higher scores indicate greater levels of awareness and use of protective behaviors. Alphas on the ASK subscales for the present sample are slightly lower than in the original psychometric sample (αAwareness = 0.68; αBehaviors = 0.75), likely because the composition of the two samples is not directly comparable. Subsequent analyses, including factorial invariance tests across differing samples at various levels of risk are thus warranted to further refine this outcome measure.

To assess the effect of the added SPSHK module on efficacy of PAT, parents responded to questions regarding parenting behaviors targeted by the PAT curriculum at all time points (Figure 1). Three subscales of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ; Shelton et al., 1996) corresponding to the parenting skills taught by PAT were selected: involvement (nine-items; αt1 = .85; e.g. “You ask your child about his/her day in school”), positive parenting (six items; αt1 = 36; e.g. “You hug or kiss your child when he/she does something well”), and inconsistent discipline (six items; αt1 = .74; e.g. The punishment you give your child depends on your mood”).All items were rated on a 5-point frequency scale (never to always) with higher scores indicating a higher frequency of the behavior (max score = 105). Parents also had the option to select “child is too young.” For the present analyses, parents reporting on children under two years old were excluded from the APQ analysis. If a parent endorsed the “child is too young” option, but the oldest reported child was over two years old, the item was recoded to never.

Analytic Plan

Data were managed using REDCap® and analyzed using SAS v 9.4. Between-group differences in parent characteristics including risk factors for maltreatment at baseline were examined, and values are reported in Table 1. Models evaluating the effect of the CSA module over time and the effect of the CSA module on parenting skills (measured by APQ) were estimated in the multilevel modeling framework using PROC MIXED with the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimator. REML is a full information maximum likelihood estimator that uses all information provided from each participant, resulting in small amounts of missing data across measures (11%). Initially, three-level multilevel models were estimated to account for time (treated as a continuous variable; level-1) nested within individuals (level-2) and sites (level-3). However, there were too few sites (n = 6) to reliably estimate the models and the ICCs were near zero. Next, we estimated two-level multilevel models controlling for site as a fixed effect. However, these models did not converge due to a multicollinearity issue between the indicator for condition and site; a majority (~86%) of participants from the control condition came from a single site. As a result, the final models estimated were two-level multilevel models, ignoring cluster, where repeated assessments were nested within individuals. The primary effect of interest was the interaction between the experimental condition (PAT+SPSHK) and the linear time trends. Alpha levels for all analyses were set to 0.05.

Results

Participant characteristics are reported in Table 1. Participants in both PAT+SPSHK and PAT-AU groups reported minimal alcohol use (M = 0.91); most parents (40%) scored a 0 on the AUDIT and no parents had a score indicating an alcohol problem. Similarly, participants reported minimal drug use (M =0.24); the majority (87%) scored a 0 on the DAST. The highest score was 2 (n = 3) indicating low drug use. Self-reported substance use among this sample was lower than hypothesized; the most recent prevalence estimates indicate that among children with a substantiated case of maltreatment, 12% had the caregiver alcohol use risk factor and 31% had the caregiver drug use risk factor (DHHS, 2020). The mean score on the CESD was 9.45 (SD = 6.64); however, 27% of the sample met diagnostic criteria for depressive symptoms (≥ 16). The prevalence of depressive symptoms is within expected ranges; it is estimated nearly one-quarter of child welfare involved children have a caregiver meeting diagnostic criteria for depression (Children’s Bureau, 2005). The mean score on the ISEL was 21 (SD = 3.51; range = 8–28) indicating a moderate level of perceived social support, though lower than observed among comparable samples (Ammerman et al., 2013). Parents in the PAT+SPSHK group reported significantly higher perceived social support compared to parents in the PAT-AU group (p = 0.04), which was controlled for in analytic models.

Effect of SPSHK

Awareness.

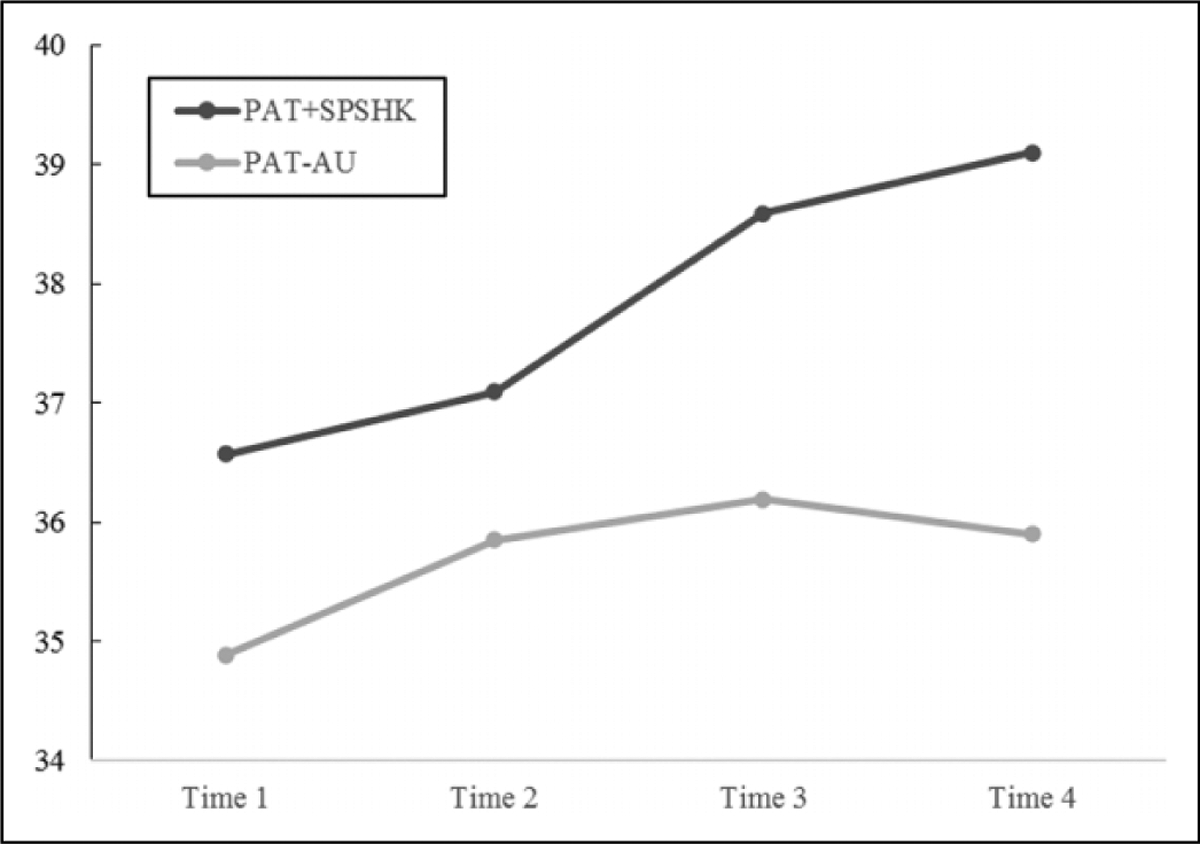

Raw means on the awareness subscale for each group over time are presented in Table 2. In the unconditional model, results indicate a significant effect for Time indicating that awareness increased linearly over time for both groups (F[1, 282] = 18.05, p < 0.001). The conditional model showed a significant Group Time interaction effect (F[1, 254] = 4.53,p = 0.034), indicating that the PAT+SPSHK group showed steeper gains in CSA awareness over time as compared to the PAT-AU group, and that these gains were maintained at follow-up (Figure 2). As depicted in Figure 2, both groups demonstrated an increase in awareness over time but the level of awareness among parents in the PAT-AU group decreased at the 1-month follow-up (T4). Post hoc area under the curve analyses indicate gains in awareness among the PAT+SPSHK group were maintained to a greater degree at follow-up compared to the PAT-AU group (F[1, 89] = 5.68, p =.019). This suggests that those who received SPSHK were able to maintain gains and a longer follow-up period may further be evidence of the benefit of the added module.

Table 2.

Raw Means of Outcomes of Interest: Awareness and Behaviors as Measured by the Assessment of SmartParent Knowledge (ASK) and Parenting Behaviors as Measured by the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ).

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Mean (SD) | PAT-AU (n = 59) | PAT+SPSHK (n = 43) | PAT-AU (n = 52) | PAT+SPSHK (n = 44) | PAT-AU (n = 51) | PAT+SPSHK (n = 44) | PAT-AU (n = 48) | PAT+SPSHK (n = 39) |

| ASK | Behavior | 21.61 (4.56) | 21.53 (4.28) | 21.53 (4.41) | 22.72 (4.79) | 22.02 (4.83) | 23.34 (4.64) | 22.45 (4.76) | 23.90 (4.44) |

| Awareness | 34.89 (4.53) | 36.57 (3.65) | 35.85 (4.30) | 37.79 (3.85) | 36.19 (4.27) | 38.59 (4.00) | 35.90 (4.03) | 39.10 (4.29) | |

| APQ | Involvement | 24.86 (7.80) | 25.26 (7.75) | 23.38 (8.26) | 25.0 (8.58) | 24.54 (8.31) | 25.40 (7.53) | 25.14 (8.70) | 24.77 (7.94) |

| Positive Parenting | 21.42 (2.37) | 21.51 (1.91) | 20.77 (3.31) | 21.88 (2.07) | 21.27 (2.34) | 21.00 (3.22) | 21.27 (2.69) | 21.69 (1.79) | |

| Inconsistent Discipline | 6.76 (4.03) | 5.74 (3.77) | 5.87 (3.68) | 5.45 (3.86) | 5.62 (3.77) | 5.45 (3.59) | 5.06 (4.02) | 5.11 (3.52) | |

Note. Sample size for each group reflects the parents that were excluded if their child was under 2 years old, as well as attrition over time. KEY: PAT = Parents as Teachers; AU = As Usual; SPSHK = Smart Parents–Safe and Healthy Kids.

Figure 2.

Raw means on the awareness subscale of the assessment of smartparents’ knowledge. Note: Unconditional model indicates a linear increase in awareness over time (F[1, 282] = 18.05, p < 0.001). The conditional model indicated a significant Group ×Time interaction effect (F[1, 254] = 4.53, p = 0.034), controlling for between-group differences in demographic characteristics (marital status, age, educational attainment, income, receipt of aid, and perceived social support). Area under the curve analyses indicate a significant group difference (F[1, 89] = 5.68, p < 0.019), demonstrating that at follow-up there was significant degradation in awareness among the PAT-AU group.

Behaviors.

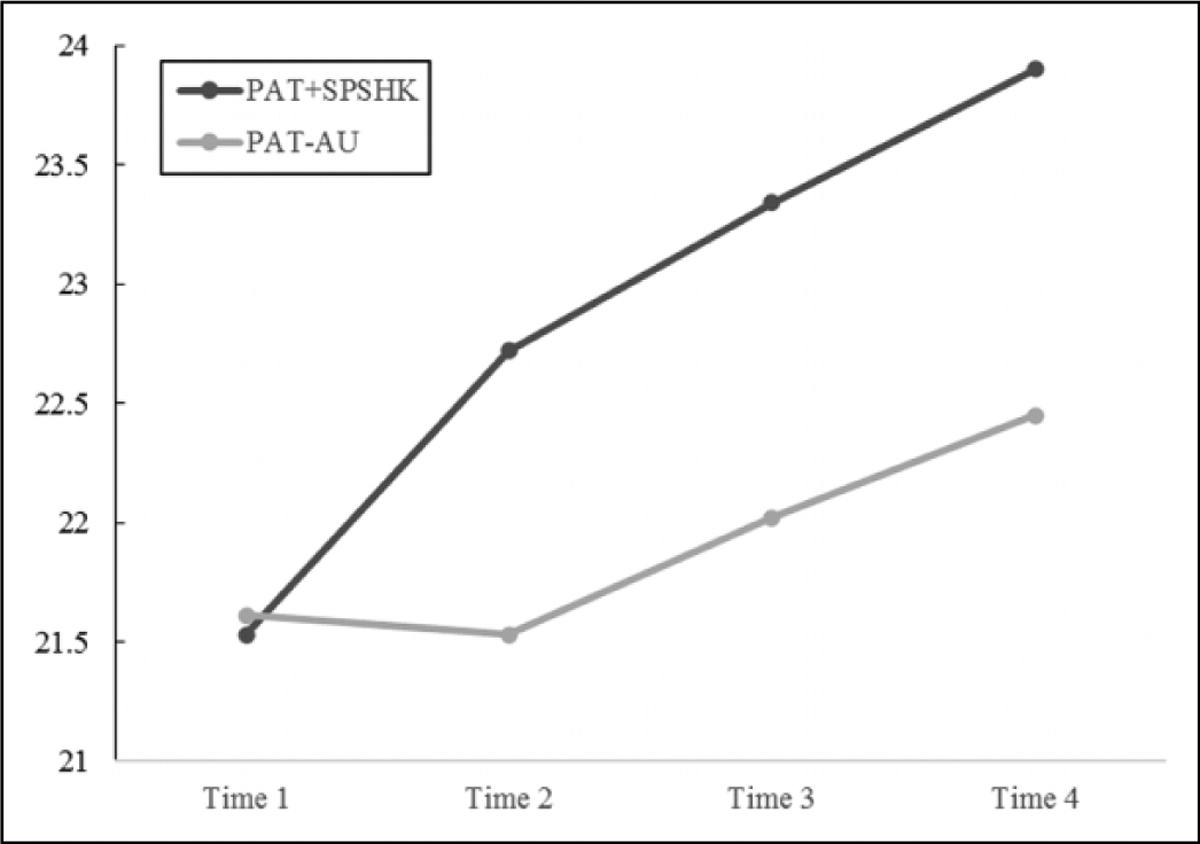

Raw means on the behavior subscale for each group over time are presented in Table 2. Unconditional models for behaviors showed a significant linear effect for Time (F[1,281] = 22.67, p < 0.001), indicating that behaviors, similar to awareness, increased linearly. The conditional model also showed a significant Group× Time effect (F[1.236] = 8.36, p < 0.001), suggesting greater gains in protective behaviors for those in the PAT+SPSHK group than for those in the PAT-AU group (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Raw means on the behaviors subscale of the assessment of smart parents’ knowledge. Note: Unconditional model indicates a linear increase in protective behaviors over time (F[1,281] = 22.67, p < 0.001). The conditional model indicated a significant Group × Time interaction effect (F[1.236] = 8.36, p < 0.001), controlling for between-group differences in demographic characteristics (marital status, age, educational attainment, income, receipt of aid, and perceived social support).

Effect of SPSHK on the Efficacy of PAT

A secondary objective was to evaluate the impact of the addition of the added CSA-module, SPSHK, on the efficacy of PAT. Table 2 depicts raw means of general parenting behaviors as measured by the APQ for PAT SPSHK and PAT-AU groups at each assessment timepoint. Unconditional models for involvement (F[1, 265] = 1.21, p = 0.27) and positive parenting (F[1, 265] = 0.52, p = 0.47) did not indicate a significant effect for time, suggesting these self-reported behaviors did not increase linearly over time. In contrast, results of the unconditional model for inconsistent discipline indicate a significant effect for time (F[1, 265] = 9.53, p =0.002), suggesting a reduction in the use of inconsistent discipline strategies over time. In conditional models, there were no significant Group Time effects on involvement (F[1, 240] = 0.89, p = 0.34), positive parenting (F[1, 240] = 0.02, p =0.89), or inconsistent discipline (F[1, 240] = 0.18, p = 0.67). This suggests that there was no difference in general parenting behaviors for those in PAT+SPSHK group than for those in the PAT-AU group, and the added session did not adversely alter the efficacy of PAT nor did it increase efficacy.

Discussion

Given the recent uptick in national prevalence estimates (Finkelhor et al., 2020), and the high economic burden conferred by CSA (Letourneau et al., 2018), there is a need for innovative primary prevention strategies. One way to maximize the public health impact is to target those at highest risk, a subgroup for whom a selective prevention strategy would be most efficacious and cost-effective (Dodge, 2020). As risk for CSA is heighted by the need for parent-training and involvement with the child welfare system (Laaksonen et al., 2011; Palusci & Ilardi, 2020), the child welfare system can provide the necessary screening mechanism for a selective parent-focused CSA prevention program. The parent training programs currently employed in these systems lack CSA-specific curriculum and thus have been insufficient to impact overall rates of CSA (Selph et al., 2013). SPSHK was designed to be added onto existing parent training programs delivered in the child welfare system in one additional session and to equip parents with the awareness and skills that can protect their children (and other children within their community) from CSA victimization. A primary prevention strategy, SPHSK could therefore be implemented to any parent receiving a parent-education program. Findings suggest that when added to PAT, an existing parent-education program delivered to skill-seeking parents involved in the child welfare system, in one session SPSHK significantly improved parents’ CSA-related awareness and increased use of protective behaviors compared to parents receiving PAT as usual. Gains in CSA-related awareness were evident in both groups, however the downtrend observed among the PAT-AU group at the 1 month follow-up suggests these gains may have been artifacts from PAT related to general awareness about child safety that were not maintained over time (Figure 2). The effect on protective behaviors is especially encouraging given the lack of behavioral outcomes in prior research. How these self-reported behaviors translate into actual calls to protective services and/or lowering CSA risk in home environments remains to be seen. Future research should be designed to test whether SPSHK operates as primary prevention by indeed changing behaviors that impact overall rates of CSA.

This first attempt to add a CSA-focused module onto existing evidence-based parent training has several strengths. First, SPSHK was designed as a selective prevention approach to be implemented through the child welfare system thereby reaching families in environments where the risk for CSA is heightened. Second, this approach capitalizes on existing infrastructure by including SPSHK in parent-education services within the child welfare system. Results demonstrate the added session did not alter the efficacy of PAT and that changes in awareness and protective behaviors can be accomplished in one additional session suggesting that a standalone program may not be necessary. Because it can be added to existing evidence-based parent training, this approach also has the potential to enhance parental engagement—a persistent issue across models (Guastaferro et al., 2018). This study was not without its limitations. First, parents were enrolled in this study did not necessarily have child welfare involvement as they were largely referred to PAT through community-level pipelines, including through schools, word of mouth, or voluntarily. As such, this sample was likely at lower risk than most parents who are receiving public services and may not be representative to the target SPSHK population. Although parents in the present sample did not endorse high rates of substance use, they did however report levels of depression and social support consistent with other child welfare samples (Ammerman et al., 2013; Children’s Bureau, 2005). Nonetheless, future permutations of SPSHK should be derived on child-welfare referred parents. Second, given that SPSHK was added to a home-visiting based parenting program delivered to individuals, it is unknown how these findings might generalize to other programs, particularly those delivered through other modalities (e.g., group-based administration via programs akin to Incredible Years (Reid & Webster-Stratton, 2001)). Finally, gains in awareness and protective behaviors reported in this study were only observed at 1-month post-intervention and it is unclear whether long-term gains might be sustained. Longer-term follow-up studies of the addition of SPSHK to parenting programs delivered through child protective service systems is warranted. Delivered through child protective service system involvement, it may be possible to ascertain the impact of SPSHK on actionable behaviors that can impact rates of CSA. It is important to consider that teaching parents CSA-related awareness and protective behavior will have an impact on children beyond their immediate family. Thus, future research should not only examine administrative records of CSA, but include a more comprehensive self-report of behaviors, perhaps incorporating vignettes or role-play scenarios.

While selective prevention efforts are most cost-effective (Dodge, 2020), they bear the cost of screening which can limit the feasibility of these approaches. By implementing SPSHK into the service array of the child welfare system, the barrier of screening is essentially moot, thus heightening the feasibility and sustainability of this selective prevention approach. Sustainability is further enhanced by U.S. federal legislation, such as the Stronger Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act and the Family First Preservation Services Act, in which the use of evidence-based programs is required among child welfare systems. The finding that the added session of SPSHK did not alter the efficacy of the evidence-based parent training programs, suggests that it may be possible to consider the addition of SPSHK to programs that are covered under this federal legislation. SPSHK is an innovative, unique parent-focused CSA primary prevention strategy with promising results. Capitalizing on legislation and existing infrastructure offer a unique, cost-effective approach to the primary prevention of CSA.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was supported in part by The Pennsylvania State University Social Science Research Institute, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute on Child Health and Human Development through award P50 HD089922, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through grant UL1 TR002014 and UL1 TR00045, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse through grant P50 DA039838. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ammerman RT, Putnam FW, Altaye M, Teeters AR, Stevens J, & Van Ginkel JB (2013). Treatment of depressed mothers in home visiting: Impact on psychological distress and social functioning. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(8), 544–554. 10.1038/jid.2014.371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assink M, van der Put CE, Meeuwsen MWCM, De Jong NM, Oort FJ, Stams GJJM, & Hoeve M (2019). Risk factors for child sexual abuse victimization: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 145(5), 459–489. 10.1037/bul0000188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes JE, Noll JG, Putnam FW, & Trickett PK (2009). Sexual and physical victimization among victims of severe childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect, 33(7), 412–420. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JD, Kotake C, Fauth R, & Easterbrooks MA (2017). Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: Do maltreatment type, perpetrator, and substantiation status matter? Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 84–94. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington PE, Cooper C, Minot S, Brugha TS, Jenkins R,Meltzer H, & Dennis M (2009). Suicide attempts, gender, and sexual abuse: Data from the 2000 British psychiatric morbidity survey. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(10), 1135–1140. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrick JD (1988). Parental involvement in child abuse prevention training: What do they learn? Child Abuse & Neglect, 12(4), 543–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bröning S, Kumpfer K, Kruse K, Sack PM, Schaunig-Busch I,Ruths S, Moesgen D, Pflug E, Klein M, & Thomasius R (2012). Selective prevention programs for children from substance-affected families: A comprehensive systematic review. Substance Abuse: Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 7(23), 1–17. 10.1186/1747-597X-7-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess ES, & Wurtele SK (1998). Enhancing parent-child communication about sexual abuse: A pilot study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(11), 1167–1175. 10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00094-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin MJ, Hecht D, Bard D, Silovsky JF, & Beasley WH (2012). A statewide trial of the SafeCare home-based services model with parents in Child Protective Services. Pediatrics, 129(3), 509–515. https://doi.org/peds.2011-1840[pii] 10.1542/peds.2011-1840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Children’s Bureau of the Administration on Chidlren and Families.(2005). National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-being (NSCAW): CPS sample component wave 1 data analysis report. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/abuse_neglect/nscaw/reports/cps_sample/cps_report_revised_090105.pdf

- Cohen S, Mermelstein RJ, Kamarck T, & Hoberman HM (1985). Measuring the functional components of social support. In Sarason IG & Sarason BR (Eds.), Social support: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 73–94). Martinus Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Daigneault I, Vézina-gagnon P, Bourgeois C, Esposito T, & Hébert M (2017). Physical and mental health of children with substantiated sexual abuse: Gender comparisons from a matched control cohort study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 66, 155–165. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.02.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies EA, & Jones AC (2013). Risk factors in child sexual abuse. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 20(3), 146–150. 10.1016/j.jflm.2012.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K, Schneiger A, Nelson S, & Kaufman NK (2002). Preventing early adolescent substance use: A family centered strategy for the public middle school. Prevention Science, 3(3), 191–201. 10.1023/A:1019994500301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA (2020). Annual research review: Universal and targeted strategies for assigning interventions to achieve population impact. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(3), 255–267. 10.1111/jcpp.13141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Brown DW, Felitti VJ,Dong M, & Giles WH (2005). Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(5), 430–438. 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JY, Hughes M, Asnes AG, & Leventhal JM (2015). Child maltreatment and risk patterns among participants in a child abuse prevention program. Child Abuse and Neglect, 44, 184–193. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, & Baron L (1986). Risk factors for child sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1(1), 43–71. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Moore D, Hamby SL, & Straus MA (1997). Sexually abused children in a national survey of parents: Methodological issues. Child Abuse & Neglect, 21(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Saito K, & Jones L (2019). Updated trends in child maltreatment, 2017. Durham. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Saito K, & Jones L (2020). Updated trends in child Maltreatment, 2018. 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004 [DOI]

- Finkelhor D, & Shattuck A (2012). Characteristics of crimes against juveniles. Durham. [Google Scholar]

- Guastaferro K, Self-Brown S, Shanley JR, Whitaker DJ, & Lutzker JR (2018). Engagement in home visiting: An overview of the problem and how a coalition of researchers worked to address this cross-model concern. Journal of Child and Family Studies 10.1007/s10826-018-1279-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guastaferro K, Zadzora KM, Reader JM, Shanley J, & Noll JG (2019). A parent-focused child sexual abuse prevention program: Development, acceptability, and feasibility. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(7), 1862–1877. 10.1007/s10826-019-01410-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (RED-Cap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornor G (2004). Sexual behavior in children: Normal or not? Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 18(2), 57–64. 10.1016/S0891-5245(03)00154-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (1994). Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. 10.17226/2139 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jin Y, Chen J, & Yu B (2019). Parental practice of child sexual abuse prevention education in China: Does it have an influence on child’s outcome? Children and Youth Services Review, 96(November 2018), 64–69. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.11.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jonzon E, & Lindblad F (2004). Disclosure, reactions, and social support: Findings from a sample of adult victims of child sexual abuse. Child Maltreatment, 9(2), 190–200. 10.1177/1077559504264263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, Lawrence HR, Milletich RJ, Hollis BF, & Henson JM (2015). Modeling risk for child abuse and harsh parenting in families with depressed and substance-abusing parents. Child Abuse and Neglect, 43, 42–52. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwako LE, Noll JG, Putnam FW, & Trickett PK (2010). Childhood sexual abuse and attachment: An intergenerational perspective. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 15(3), 407–422. 10.1177/1359104510367590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laaksonen T, Sariola H, Johansson A, Jern P, Varjonen M, Von Der Pahlen B, Sandnabba NK, & Santtila P (2011). Changes in the prevalence of child sexual abuse, its risk factors, and their associations as a function of age cohort in a Finnish population sample. Child Abuse and Neglect, 35(7), 480–490. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc B, Smallbone S, & Wortley R (2015). Prevention nearby: The influence of the presence of a potential guardian on the severity of child sexual abuse. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment, 27(2), 189–204. 10.1177/1079063213504594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau EJ, Brown DS, Fang X, Hassan A, & Mercy JA (2018). The economic burden of child sexual abuse in the United States. Child Abuse & Neglect, 79, 413–422. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipari RN, & Van Horn SL (2017). Children living with parents who have a substance use disorder. The CBHSQ Report: August 24, 2017. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/report_3223/ShortReport-3223.html [PubMed]

- Lundahl BW, Nimer J, & Parsons B (2006). Preventing child abuse: A meta-analysis of parent training programs. Research on Social Work Practice, 16(3), 251–262. 10.1177/1049731505284391 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason WA, Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Haggerty KP, & Spoth RL (2003). Reducing adolescents growth in substance use and delinquency: Randomized trial effects of parent training prevention intervention. Prevention Science, 4(3), 203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey LA, & Bailey JA (2000). The intergenerational transmission of risk for child sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15(10), 1019–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson T, & Letourneau E (2015). Parent-focused prevention of child sexual abuse. Prevention Science, 16, 844–852. 10.1007/s11121-015-0553-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Guastaferro K, Beal SJ, Schreier HMC, Barnes J,Reader JM, & Font SA (2018). Is sexual abuse a unique predictor of sexual risk behaviors, pregnancy, and motherhood in adolescence? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 1–17. 10.1111/jora.12436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, & Shenk CE (2013). Teen birth rates in sexually abused and neglected females. Pediatrics, 131(4), e1181–e1187. 10.1542/peds.2012-3072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Trickett PK, Long JD, Negriff S, Susman EJ,Shalev I, Li JC, & Putnam FW (2017). Childhood sexual abuse and early timing of puberty. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(1), 65–71. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Zeller MH, Trickett PK, & Putnam FW (2007). Obesity risk for female victims of childhood sexual abuse: A prospective study. Pediatrics, 120(1), e61–e67. 10.1542/peds.2006-3058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine ML, & Hansen DJ (2002). Factors influencing children to self-disclose sexual abuse. Clinical Psychology Review, 22(2), 271–295. 10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00091-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palusci VJ (2011). Risk factors and services for child maltreatment among infants and young children. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(8), 1374–1382. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.04.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palusci VJ, & Ilardi M (2020). Risk factors and services to reduce child sexual abuse recurrence. Child Maltreatment, 25(1), 106–116. 10.1177/1077559519848489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Fuentes G, Olfson M, Villegas L, Morcillo C, Wang S, & Blanco C (2013). Prevalence and correlates of child sexual abuse: A national study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 54(1), 16–27. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz RJ, Sanders MR, Shapiro CJ, Whitaker DJ, & Lutzker JR (2009). Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. Triple P system population trial. Prevention Science, 10, 1–12. 10.1007/s11121-016-0631-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulido ML, Dauber S, Tully BA, Hamilton P, Smith MJ, & Freeman K (2015). Knowledge gains following a child sexual abuse prevention program among urban students: A cluster-randomized evaluation. American Journal of Public Health, 105(7), 1344–1350. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurements, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rae Grant NI (1994). Preventive interventions for children and adolescents: Where are we now and how far have we come? Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 13(2), 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Reid J, & Webster-Stratton C (2001). The incredible years parent, teacher, and child intervention: Targeting multiple areas of risk for a young child with pervasive conduct problems using a flexible, manualized treatment program. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 8(4), 377–386. [Google Scholar]

- Rheingold AA, Zajac K, Chapman JE, Patton M, de Arellano M, Saunders B, & Kilpatrick D (2015). Child sexual abuse prevention training for childcare professionals: An independent multi-site randomized controlled trail of Stewards of Children. Prevention Science, 16(3), 374–385. 10.1007/s11121-014-0499-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph J, & Zimmer-Gembeck MJ (2018a). Parents as protectors: A qualitative study of parents’ views on child sexual abuse prevention. Child Abuse and Neglect, 85(August), 28–38. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph J, & Zimmer-Gembeck MJ (2018b). Reviewing the focus: A summary and critique of child-focused sexual abuse prevention. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 19(5), 543–554. 10.1177/1524838016675478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph J, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Shanley DC, & Hawkins R(2018). Child sexual abuse prevention opportunities: Parenting, programs, and the reduction of risk. Child Maltreatment, 23(1), 96–106. 10.1177/1077559517729479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, & Grant M (1993). Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Screening Test (AUDIT). WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption. II. Addiction, 88, 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Petta I, McPherson K, Greene A, & Li S (2010). Fourth national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS–4): Report to congress. 10.1037/e659872010-001 [DOI]

- Selph SS, Bougatsos C, Blazina I, & Nelson HD (2013). Behavioral interventions and counseling to prevent child abuse and neglect: A systematic review to update the U.S. Preventive Task Force recommendation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 158(3), 179–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KK, Frick PJ, & Wootton J (1996). Assessment of parenting practices in families of elementary school-age children. Jounral of Clinical Child Psychology, 25(3), 317–329. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA (1982). The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addiction, 7(4), 363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HN (2000). Sexual assault of young children as reported to law enforcement: Victim, incident, and offender characteristics. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Liu T, Davies LC, Boykin EL, Alder MC, Harris JM, Som A, McPherson M, & Dees JEMEG (2009). Risk factors in child maltreatment: A meta-analytic review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(1), 13–29. 10.1016/j.avb.2006.03.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, van IJzendoorn MH, Euser EM, & Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ (2011). A global perspective on child sexual abuse: Meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreatment, 16(2), 79–101. 10.1177/1077559511403920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmer S, & Urquiza A (2014). Why we think we can make things better with evidence-based practice: Theoretical and developmental context. In Timmer S, & Urquiza A (Eds.), Evidence-based approaches for the treatment of maltreated children: Considering core components and treatment effectiveness (Vol. 3, pp. 19–39). 10.1007/978-94-007-7404-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, Noll JG, & Putnam FW (2011). The impact of sexual abuse on female development: Lessons from a multigenerational, longitudinal research study. Development and Psychopathology, 23(2), 453–476. 10.1017/S0954579411000174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S Department of Health & Human Services, Administration on Children and Families, Administration on Children Youth and Families, & Children’s Bureau. (2020). Child Maltreatment 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/childmaltreatment

- Vachon DD, Krueger RF, Rogosch FA, & Cicchetti D (2015). Assessment of the harmful psychiatric and behavioral effects of different forms of child maltreatment. JAMA Psychiatry, E1–E9. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K, Zwi K, Woolfenden S, & Shlonsky A (2018). School-based education programs for the prevention of child sexual abuse: A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Research on Social Work Practice, 28(1), 33–55. 10.1177/1049731515619705 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wandersman A, & Florin P (2003). Community interventions and effective prevention. American Psychologist, 58(6/7), 441–448. 10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C, Shanley DC, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Walsh K, Hawkins R, Lines K, & Webb H (2018). Promoting young children’s interpersonal safety knowledge, intentions, confidence, and protective behavior skills: Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Child Abuse and Neglect, 82(May), 144–155. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtele SK (2009). Preventing sexual abuse of children in the twenty-first century: Preparing for challenges and opportunities. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 18(1), 1–18. 10.1080/10538710802584650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtele SK, Moreno T, & Kenny MC (2008). Evaluation of a sexual abuse prevention workshop for parents of young children. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 1(4), 331–340. 10.1080/19361520802505768 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie QW, Qiao DP, & Wang XL (2016). Parent-involved prevention of child sexual abuse: A qualitative exploration of parents’ perceptions and practices in Beijing. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(3), 999–1010. 10.1007/s10826-015-0277-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zigler E, Pfannenstiel JC, & Seitz V (2008). The parents as teachers program and school success: A replication and extension. Journal of Primary Prevention, 29(2), 103–120. 10.1007/s10935-008-0132-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]