Abstract

The establishment of bipolar spindles during meiotic divisions ensures faithful chromosome segregation to prevent gamete aneuploidy. We analyzed centriole duplication, as well as centrosome maturation and separation during meiosis I and II using mouse spermatocytes. The first round of centriole duplication occurs during early prophase I, and then, centrosomes mature and begin to separate by the end of prophase I to prime formation of bipolar metaphase I spindles. The second round of centriole duplication occurs at late anaphase I, and subsequently, centrosome separation coordinates bipolar segregation of sister chromatids during meiosis II. Using a germ cell‐specific conditional knockout strategy, we show that Polo‐like kinase 1 and Aurora A kinase are required for centrosome maturation and separation prior to metaphase I, leading to the formation of bipolar metaphase I spindles. Furthermore, we show that PLK1 is required to block the second round of centriole duplication and maturation until anaphase I. Our findings emphasize the importance of maintaining strict spatiotemporal control of cell cycle kinases during meiosis to ensure proficient centrosome biogenesis and, thus, accurate chromosome segregation during spermatogenesis.

Keywords: Aurora kinase, centriole, centrosome, chromosome segregation, meiosis, polo‐like kinase

Subject Categories: Cell Adhesion, Polarity & Cytoskeleton; Cell Cycle

Polo‐like kinase 1 and Aurora A kinase are required for the maturation and separation of centrosomes prior to the first meiotic division in mouse spermatocytes, which ensure accurate segregation of chromosomes during spermatogenesis.

Introduction

The centrosome, the main microtubule‐organizing center (MTOC) in animal cells, executes important functions during cell divisions to ensure faithful segregation of chromosomes. Prior to its duplication, a canonical centrosome consists of two centrioles surrounded by a proteinaceous matrix, the pericentriolar material (PCM). The centriole, with a conserved cylinder architecture organized by nine microtubule triplets, is specifically involved in spindle orientation and centrosome structural maintenance (Bettencourt‐Dias & Glover, 2007; Nigg & Holland, 2018). PCM, conventionally perceived to be amorphous, is actually a structurally ordered and highly hierarchical matrix that drives microtubule nucleation through the recruitment of factors including γ‐tubulin and pericentrin (PCNT; Rieder et al, 2001; Bornens, 2002; Fu & Glover, 2012).

In mitotically dividing cells, centrosome biogenesis is synchronized with the cell cycle. In G1‐phase, the cell has one centrosome that consists of two centrioles that are connected by intercentrosomal linker proteins. Centriole duplication is initiated at the onset of S‐phase, when a procentriole cartwheel structure comprising components such as spindle assembly proteins, SAS4 and SAS6, and centrosomal protein, CEP135, forms orthogonally to the mother centriole (Leidel & Gönczy, 2003; Gopalakrishnan et al, 2010; Kraatz et al, 2016). The procentriole elongates by the recruitment of centrin proteins (CETN1–4) throughout S‐phase and G2 phase while simultaneously recruiting additional PCM proteins that drive centrosome maturation. In later stages of G2 phase, the mature centrosomes separate following the degradation of intercentrosomal linkers and travel to opposite poles of the cell to drive the assembly of mitotic bipolar spindles. The transition between late mitosis and early G1 marks the disengagement of the mother and daughter centriole that licenses future centriole duplication (Wang et al, 2014).

During meiosis, DNA replication is followed by recombination between homologous chromosomes, which results in the homologs being physically linked together. Then, two rounds of chromosome segregation occur, firstly, homologous chromosomes segregate (meiosis I) and then, sister chromatids segregate (meiosis II), resulting in the formation of haploid gametes that are genetically different from the parental cell. Centrosome‐mediated formation of bipolarity during male meiotic divisions is essential in spermatogenesis (Schatten & Sun, 2009; Chu & Shakes, 2013). In both Caenorhabditis elegans and mouse spermatocytes, meiosis I and II spindle poles possess a pair of engaged centrioles, indicating that centrioles undergo two rounds of duplication without an additional round of DNA replication (Albertson & Thomson, 1993; Schvarzstein et al, 2013; Marjanović et al, 2015). Compared with mitosis, where centriole duplication initiates at the start of S‐phase and centrosome separation occurs during G2‐phase, the first round of meiotic centriole duplication initiates during early prophase and centrosome separation in meiosis occurs at the end of prophase I (Marjanović et al, 2015). To date, little more is known about how centriole duplication and centrosome biogenesis is regulated during meiosis.

Coordination of centrosomal biogenesis and the ability of centrosomes to assemble bipolar spindles. As meiotic centrosome biogenesis is synchronized with cell cycle progression, it is likely that aberrancies in function or expression of cell cycle kinases will cause gamete aneuploidy and infertility. PLK1 and Aurora A kinases are important for centrosome maturation and separation in mitotically dividing cells. However, their roles during meiosis, specifically relating to centrosome dynamics, are yet to be elucidated. Therefore, we conditionally mutated Plk1 and Aurka during early meiotic prophase in mouse spermatocytes and assessed perturbations in centriole duplication, centriole and centrosome maturation, and centrosome separation.

Results

Centriole duplication and centrosome separation during meiosis in mouse spermatocytes

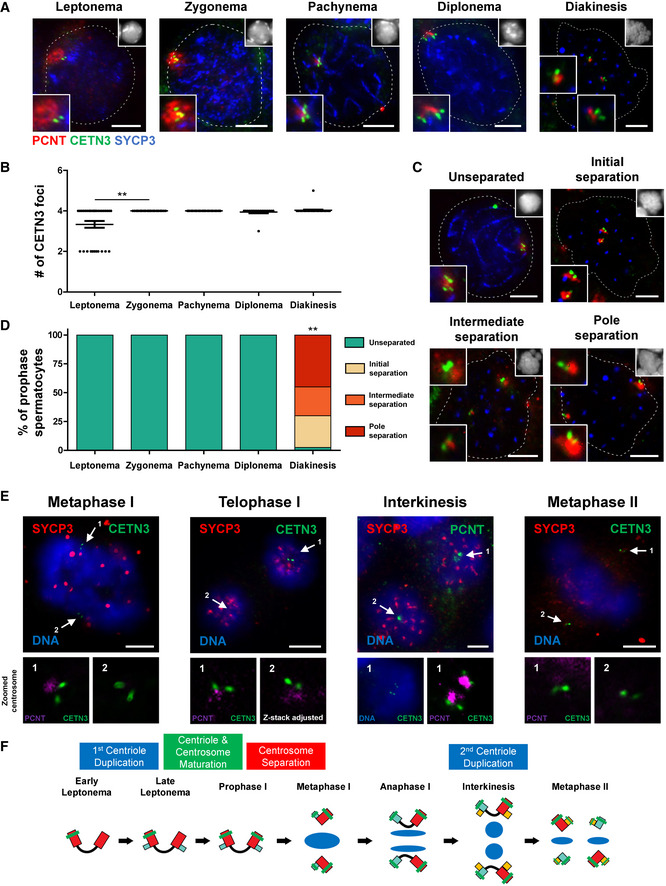

We closely assessed centriole duplication and centrosome separation during the first wave of spermatogenesis using optimized tubule squash techniques and immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig 1A; Wellard et al, 2018). We used immunofluorescence staining on two centrosomal markers, pericentrin (PCNT), and centrin 3 (CETN3), to identify the PCM and centrioles, respectively, which helped us delineate the centriole duplication and centrosome separation pattern in meiosis I. SYCP3, a lateral element of the synaptonemal complex, was used to identify the substages of prophase I. We determined that centriole duplication occurs during the first sub‐stage of prophase I, leptonema. One third of the leptotene stage spermatocytes possess a single centrosome with unduplicated centrioles, while the remaining spermatocytes have duplicated centrioles within a single centrosome (Fig 1A and B). Essentially, all spermatocytes at the later prophase I substages and prometaphase have four centrioles, indicating that centriole duplication occurs exclusively during leptonema (Fig 1A and B).

Figure 1. Centriole duplication and centrosome separation patterns during meiosis in mouse spermatocytes.

Tubule squash preparations were performed on wild‐type juvenile C57BL/6J mice undergoing the first wave of spermatogenesis.

-

ASpermatocytes were immunolabeled against PCNT (red), CETN3 (green), and SYCP3 (blue) and stained with DAPI (upper right inset). Zoomed images of the centrosome are shown in the bottom left inset. Scale bars = 5 μm.

-

BQuantification of the number of CETN3 foci per spermatocyte (n = 30) at each meiotic prophase substage. Bars and error bars show mean ± SEM. P values obtained from two‐tailed Mann–Whitney t‐test. **P < 0.01.

-

CRepresentative images of unseparated (< 1 μm apart), initial separation (1–5 μm apart), intermediate separation (5–11 μm apart), and pole separation (> 11 μm apart) of centrosomes. Spermatocytes were immunolabeled against PCNT (red), CETN3 (green), and SYCP3 (blue) and stained with DAPI (upper right inset). Zoomed images of the centrosome are shown in the bottom and top left insets. Scale bars = 5 μm.

-

DCentrosome separation was scored in n = 30 spermatocytes at each prophase substage using the four centrosome separation classifications shown in C. P value obtained from a Kruskal–Wallis one‐way ANOVA. **P < 0.01.

-

ESpermatocytes undergoing meiosis I through meiosis II were immunolabeled against PCNT (purple), CETN3 (green), and SYCP3 (red) and stained with DAPI (blue). Zoomed images of centrosomes below each panel. Scale bars = 5 μm.

-

FModel for centriole duplication and centrosome separation patterns throughout the meiotic prophase and division stages. During the leptonema to zygonema transition, the first round of centriole duplication occurs. As cells progress through meiotic prophase I, centrosomes mature and acquire distal appendages. During diakinesis centriole separation occurs, allowing the formation of a bipolar spindle during the first meiotic division. During interkinesis, centrioles duplicate a second time and separate to form a bipolar spindle at meiosis II.

At each stage of meiotic prophase, the centrioles are surrounded by the PCM as deemed by the presence of PCNT (Fig 1A and C). Centrosome separation commences during the transition between diplonema and diakinesis, and separation continues so that centrosomes are situated on opposite sides of the chromatin (Fig 1A, C and D). Thus, as the nuclear envelope breaks down at prometaphase, the centrosomes can efficiently form bipolar spindles from opposite sides of the condensed chromosomes by metaphase I (Fig 1E). As spermatocytes progress from prophase to metaphase I, the average PCNT signal per cell becomes more compact, from 13.21μm2 to 2.30μm2, respectively (Fig 1A).

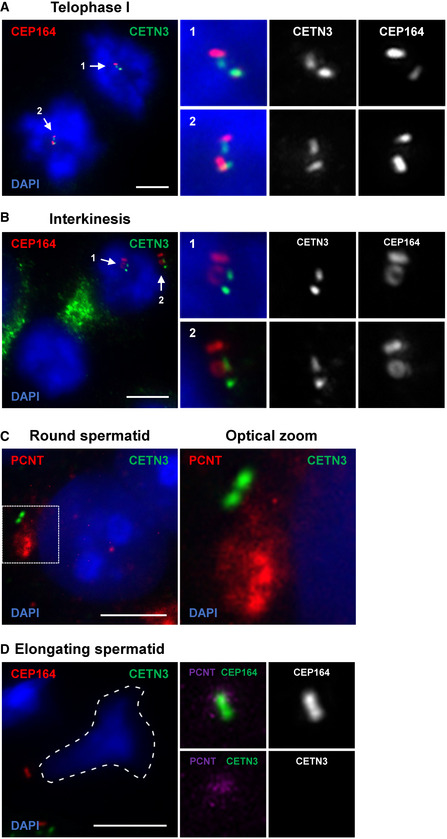

After homologous chromosomes have segregated in meiosis I, centrioles duplicate again during the interkinesis stage (Figs 1E and EV1A and B). Subsequently, centrosomes mature and separate to form metaphase II bipolar spindles that mediate the segregation of sister chromatids (Fig 1E). Thus, a single primary spermatocyte results in the formation of four haploid spermatids that each have a centrosome containing a pair of centrioles (Figs 1F and EV1C and D).

Figure EV1. Additional assessment of wild‐type spermatocytes completing meiosis I and II.

-

A, BRepresentative images of wild‐type telophase I (A) and interkinesis (B) stage spermatocytes immunolabeled against CEP164 (red) and CETN3 (green) and stained with DAPI. Scale bars = 5 μm. Subpanels show zoomed images of centrosomes with the above staining, CETN3 alone, and CEP164 alone.

-

CRepresentative image of a wild‐type round spermatid immunolabeled against PCNT (red) and CETN3 (green) and stained with DAPI. Scale bars = 5 μm.

-

DRepresentative image of a wild‐type elongating spermatid immunolabeled against CEP164 (red) and CETN3 (green) and stained with DAPI. Scale bars = 5 μm. Subpanels highlight the centrosome with various combinations of PCNT, CETN3, and CEP164 immunolabeling.

Conditional mutation of Plk1 in primary spermatocytes leads to apoptosis and infertility

Mice that harbored a conditional knockout (cKO) allele of Plk1 were used to assess the requirement of PLK1 during meiotic divisions (Fig EV2A, see materials and methods). Exon 3 of Plk1 was flanked by loxP Cre recombinase target sequences, and this allele was termed Plk1 flox (Fig EV2A). Breeding heterozygous Plk1 flox mice to mice expressing the Cre recombinase transgene generated a KO allele termed Plk1 del (Fig EV2A). We used the Spo11‐Cre transgene, which is expressed in spermatocytes as early as 10 days post‐partum, corresponding to early prophase, pre‐leptotene/leptotene stage (Lyndaker et al, 2013; Hwang et al, 2018). We assessed three genotypes of male mice; control (Plk1 +/flox), conditional heterozygous mutants (Plk1 +/flox, Spo11‐Cre tg/0; called Plk1 cHet), and conditional knockout mutants (Plk1 flox/del, Spo11‐Cre tg/0; called Plk1 cKO).

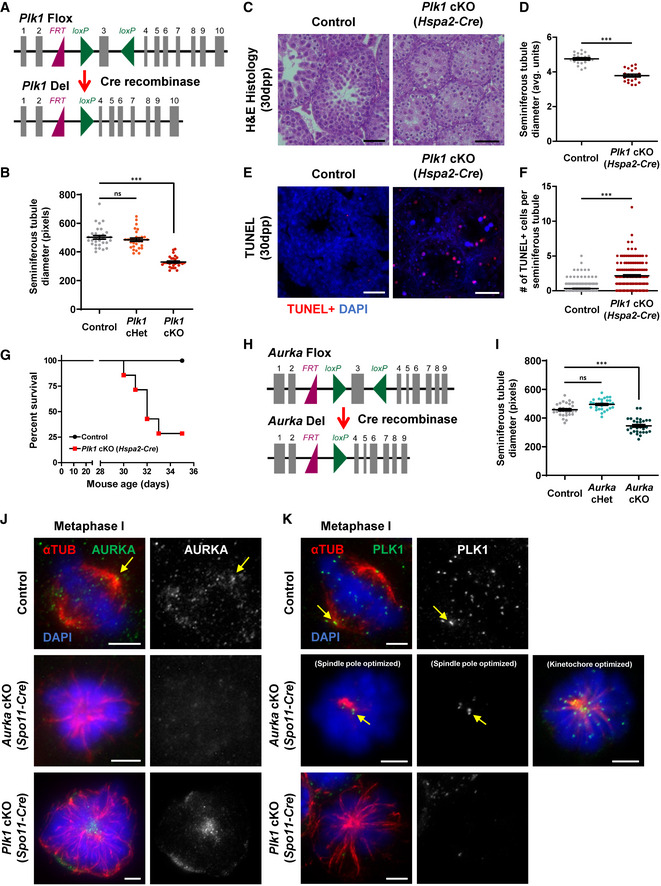

Figure EV2. Conditional deletion of Plk1 and Aurka in mouse primary spermatocytes.

-

ADiagram of the Plk1 flox and Plk1 del alleles. The Plk1 flox allele harbors two loxP sites (green triangle) flanking exon 3 (gray box), and the resulting Plk1 deletion allele after excision of exon 3 by Cre recombinase in early prophase. The purple triangle represents the remaining Frt site following FLP‐mediated recombination of the original conditional ready tm1a allele (Plk1tm1a(EUCOMM)Hmgu).

-

BSeminiferous tubule diameter was quantified from hematoxylin‐and‐eosin‐stained testis sections in control, Plk1 cHet, and Plk1 cKO mice (n = 30 tubules per genotype). Conditional deletion of Plk1 was driven by the Spo11‐Cre.

-

CHematoxylin and eosin staining of 5‐μm thick testis sections of juvenile (30dpp) control, Plk1 cHet, and Plk1 cKO mice. Conditional deletion of Plk1 was driven by the Hspa2‐Cre. Scale bars = 50 μm.

-

DSeminiferous tubule diameter was quantified from n = 30 tubules in control and Plk1 cKO (Hspa2‐Cre) mice.

-

ETUNEL staining of paraffin‐embedded testis sections of juvenile (30dpp) control, and Plk1 cKO (Hspa2‐Cre) mice. Scale bars = 50 μm.

-

FThe number of TUNEL‐positive cells per seminiferous tubule cross‐section was quantified in control (n = 277 tubules) and Plk1 cKO (Hspa2‐Cre) (n = 163 tubules) mice.

-

GKaplan–Meier survival curves of control and Plk1 cKO (Hspa2‐Cre) mice from birth to 35dpp. n = 6 mice per genotype assessed.

-

HDiagram of the Aurka flox and Aurka del alleles. The Aurka flox allele harbors two loxP sites (green triangle) flanking exon 3 (grey box), and the resulting Aurka deletion allele after excision of exon 3 by Cre recombinase in early prophase. The purple triangle represents the remaining Frt site following FLP‐mediated recombination of the original conditional ready tm1a allele (Aurkatm1a(EUCOMM)Hmgu).

-

ISeminiferous tubule diameter was quantified from hemotoxalyn‐and‐eosin‐stained testis sections in control, Aurka cHet, and Aurka cKO mice (n = 30 tubules per genotype). Conditional deletion of Aurka was driven by the Spo11‐Cre.

-

JSpermatocytes were immunolabeled against AURKA (green), alpha‐tubulin (αTUB, red), and stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars (5 μm). Arrow indicates centrosome localized AURKA. Scale bars = 5 μm. Subpanels on the right show AURKA immunolabeling.

-

KSpermatocytes were immunolabeled against PLK1 (green), alpha‐tubulin (αTUB, red), and SYCP3 (magenta) and stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars (5 μm). Arrow indicates centrosome localized PLK1. Scale bars = 5 μm. Subpanels on the right show PLK1 immunolabeling.

Data information: For graphs (B, D, F, and I) bars and error bars show mean ± SEM. P values obtained from two‐tailed Student’s t‐test. n.s. (not significant) and ***P < 0.001.

We assessed Cre recombination efficiency by mating Plk1 cHet male mice to wild‐type C57BL6/J female mice. 97.5% of pups obtained from the Plk1 cHet males either harbored the wild‐type allele of Plk1 or Plk1 del allele, indicating the efficiency of Cre‐mediated deletion of the 3rd exon using the Spo11‐Cre transgene (Table EV1).

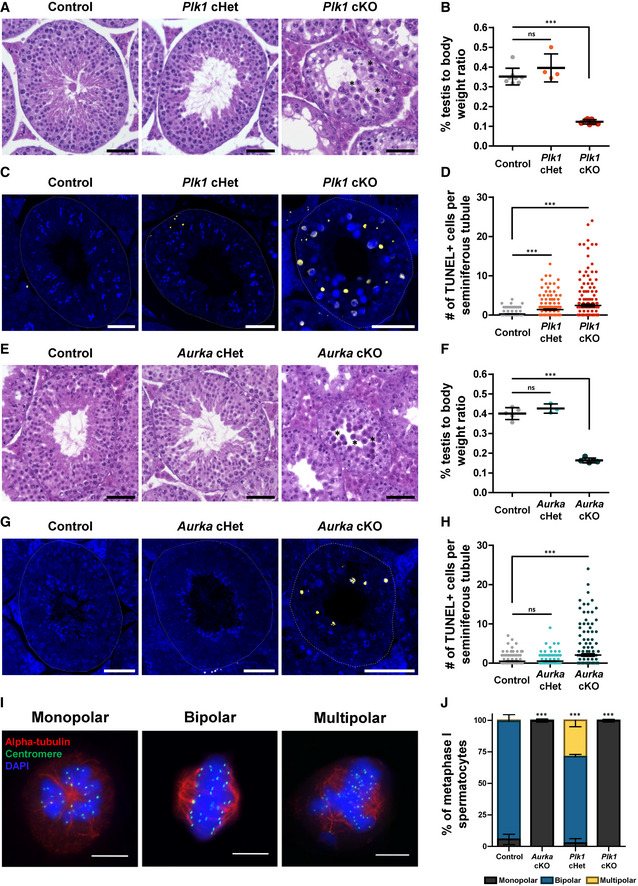

Testes from Plk1 cKO, Plk1 cHet, and control male adult littermates were harvested, weighed, and cross‐sectioned for histological analyses (Fig 2A and B). The Plk1 cKO testes were 65% smaller in weight and seminiferous tubule diameter was significantly reduced compared with Plk1 cHet and control littermates (Figs 2A and B, and EV2B). From assessment of TUNEL‐stained seminiferous tubule cross‐sections, it was evident that Plk1 cKO primary spermatocytes were undergoing apoptosis (Fig 2C and D). Additionally, the Plk1 cHet was observed to have a significant increase in TUNEL staining compared with control, indicating that conditional mutation of a single Plk1 allele causes defects during spermatogenesis (Fig 2C and D).

Figure 2. Conditional deletion of Plk1 or Aurka causes meiosis I arrest in mouse spermatocytes.

-

AHematoxylin and eosin staining of 5‐μm thick testis sections of adult control, Plk1 cHet, and Plk1 cKO mice. Stars indicate examples of spermatocytes with condensed chromosomes. Scale bars = 50 μm.

-

BPercent testis to body weight ratios from control (n = 8), Plk1 cHet (n = 4), and Plk1 cKO (n = 7) adult mice.

-

CTUNEL staining of paraffin‐embedded testis sections of adult control, Plk1 cHet, and Plk1 cKO mice. Scale bars = 50 μm.

-

DThe number of TUNEL‐positive cells per seminiferous tubule cross‐section was quantified in control Plk1 cHet, and Plk1 cKO mice. Two technical replicates were performed per genotype, and 100 seminiferous tubule cross‐sections were analyzed per replicate.

-

EHematoxylin and eosin staining of 5‐μm thick testis sections of adult control, Aurka cHet, and Aurka cKO mice. Stars indicate examples of spermatocytes with condensed chromosomes. Scale bars = 50 μm.

-

FPercent testis to body weight ratios from control (n = 5), Aurka cHet (n = 3), and Aurka cKO (n = 5) adult mice.

-

GTUNEL staining of paraffin‐embedded testis sections of adult control, Aurka cHet, and Aurka cKO mice. Scale bars = 50 μm.

-

HThe number of TUNEL‐positive cells per seminiferous tubule cross‐section was quantified in control Aurka cHet, and Aurka cKO mice. Two technical replicates were performed per genotype, and 100 seminiferous tubule cross‐sections were analyzed per replicate.

-

IRepresentative images of spermatocytes containing monopolar, bipolar, and multipolar spindles immunolabeled against alpha‐tubulin (red), centromere (green) and stained with DAPI. Scale bars = 10 µm.

-

JSpindle pole number per primary spermatocyte was quantified for control, Aurka cKO, Plk1 cHet, and Plk1 cKO. n = 3 experimental replicates with > 40 metaphase I spermatocytes analyzed per genotype in each experiment.

Data information: For all graphs (B, D, F, H, J) bars and error bars show mean ± SEM. P values obtained from two‐tailed Student’s t‐test. n.s. (not significant) and, ***P < 0.001.

To complement our assessment of the Plk1 cKO allele, we also used the Hspa2‐Cre transgene, which is expressed in leptotene/zygotene stage spermatocytes (Inselman et al, 2010; Hwang et al, 2018). Conditional mutation of Plk1 via Hspa2‐Cre also resulted in reduced seminiferous tubule diameter and apoptosis of primary spermatocytes (Fig EV2C–F). However, the Hspa2‐Cre transgene resulted in animal mortality shortly after wean age (Fig EV2G). As Plk1 is an essential gene, this indicates that Hspa2‐Cre expression occurred in other tissues and resulted in animal mortality. Indeed, it has been reported that Hspa2‐Cre is expressed in the cardiovascular, neural, and respiratory systems (Mouse Genome Informatics, http://www.informatics.jax.org/; MGI:3843498). Therefore, we used the Spo11‐Cre transgene for the remainder of our study.

Conditional mutation of Aurka in primary spermatocytes leads apoptosis and infertility

We assessed the requirement of Aurora A during spermatogenesis using mice that harbored a cKO allele of Aurka (Fig EV2H, see materials and methods). Exon 3 of Aurka was flanked by loxP Cre recombinase target sequences (Aurka flox allele; Fig EV2H). Again, we used the Spo11‐Cre transgene and assessed three genotypes of male mice; control (Aurka +/flox), conditional heterozygous mutants (Aurka +/flox, Spo11‐Cre tg/0; called Aurka cHet) and conditional knockout mutants (Aurka flox/del, Spo11‐Cre tg/0; called Aurka cKO).

We assessed Cre recombination efficiency by mating Aurka cHet male mice to wild‐type C57BL6/J female mice. All pups obtained from the Aurka cHet males either harbored the wild‐type allele of Aurka or the Aurka del allele, indicating the efficiency of Cre‐mediated deletion of the 3rd exon using the Spo11‐Cre transgene (Table EV1). The Aurka cKO testes were 59% smaller in weight, and seminiferous tubule diameter was significantly reduced compared with Aurka cHet and control littermates (Figs 2E and F and EV2I). TUNEL‐staining seminiferous tubule cross‐sections demonstrated that Aurka cKO primary spermatocytes were undergoing apoptosis (Fig 2G and H). In contrast to the Plk1 cHet, TUNEL signal detected in Aurka cHet was equivalent to control, suggesting that there are no defects during spermatogenesis when one allele of Aurka is mutated (Fig 2G and H).

Mutation of Plk1 and Aurka leads to abnormal spindle morphology during meiosis

The seminiferous tubule cross‐sections of Plk1 and Aurka cKO presented a similar accumulation of primary spermatocytes with condensed chromosomes (Figs 2A and E, and EV2C). Moreover, meiotic divisions were not evident based on the absence of secondary spermatocytes or round spermatids in Plk1 and Aurka cKO tubules (Figs 2A and E, and EV2C). To further define the stage that Plk1 cKO and Aurka cKO primary spermatocytes undergo cell cycle arrest, we performed tubule squashes and assessed alpha‐tubulin and chromosome morphology during meiosis I. Most primary spermatocytes from the control mice that had condensed chromosomes were attached to bipolar spindles, which was also the case for the Aurka cHet spermatocytes (Fig 2I and J). In contrast, the majority of Plk1 cKO and Aurka cKO primary spermatocytes with condensed chromosomes had monopolar spindles (Fig 2I and J). Intriguingly, more than 25% of the Plk1 cHet primary spermatocytes displayed a multipolar spindle morphology (Fig 2I and J).

As the stage of meiotic arrest is similar between Plk1 cKO and Aurka cKO, we assessed whether the localization of PLK1 and Aurora A was interdependent. Aurora A kinase localizes to the spindle poles and along microtubule spindle in control spermatocytes at metaphase I (Fig EV2J). PLK1 also localizes to the spindle poles at metaphase I in control spermatocytes but is also present at the kinetochores (Fig EV2K). Aurora A or PLK1 signal was absent in primary spermatocytes isolated from Aurka cKO and Plk1 cKO, respectively, demonstrating robust protein depletion (Fig EV2J and K). Aurora A signal was predominantly detected at the single spindle pole in primary spermatocytes isolated from the Plk1 cKO (Fig EV2J). Similarly, PLK1 signal was still detected at the centrosome as well as the kinetochores in the Aurka cKO (Fig EV2K). Taken together, this suggests that Aurora A and PLK1 localize to the centrosomes independently of one another.

Heterozygous mutation of Plk1 leads to centriole overduplication during meiosis

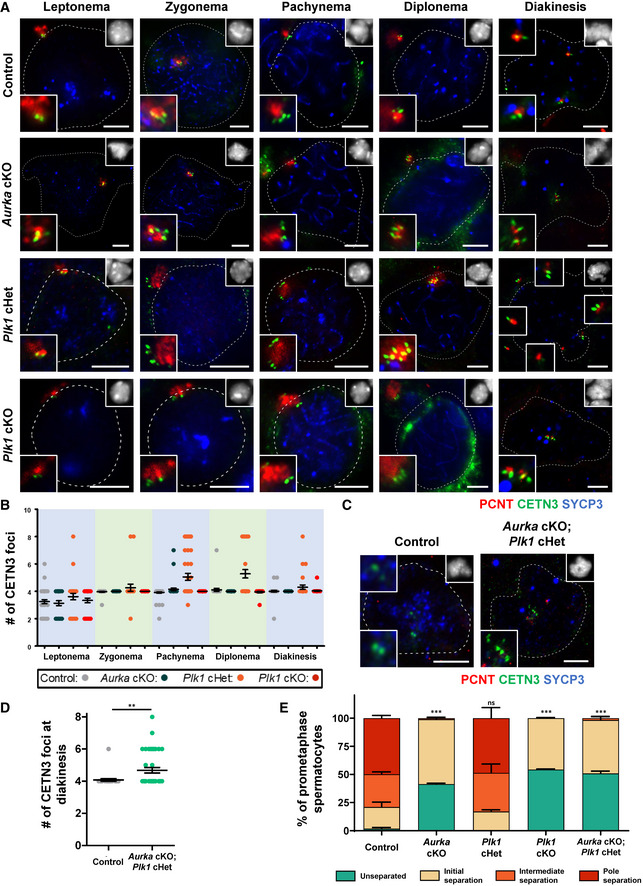

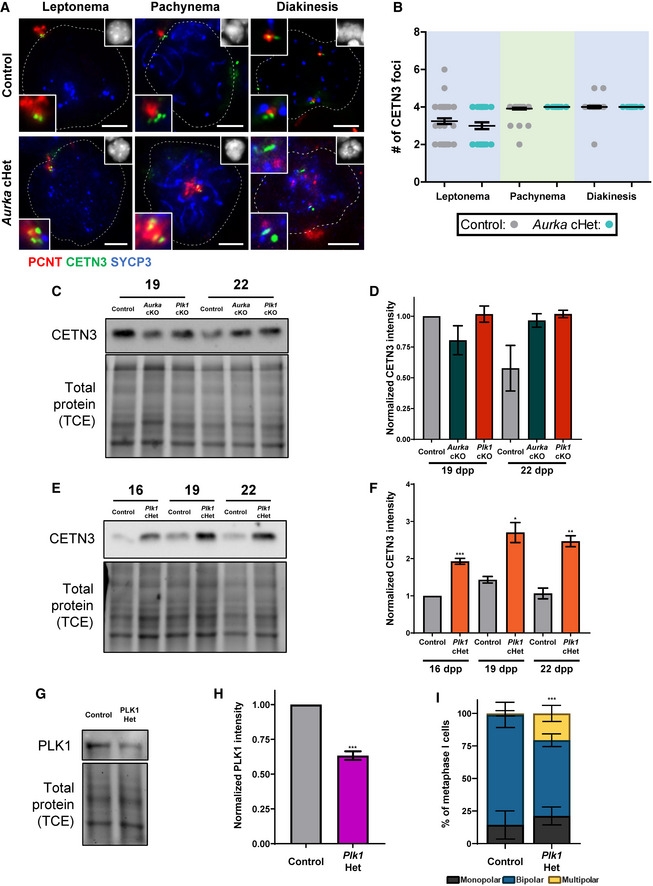

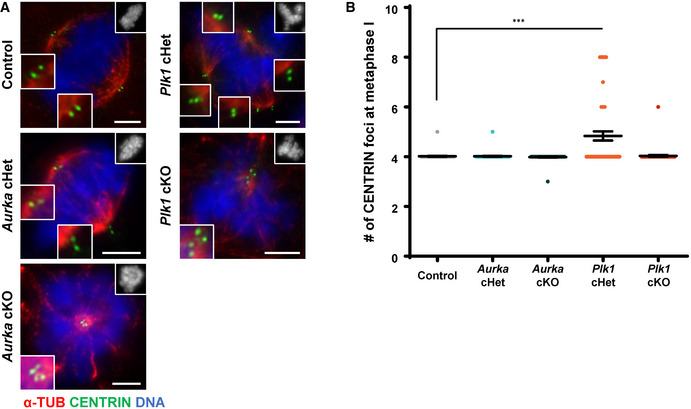

To further assess meiotic defects of the Plk1 and Aurka conditional mutants, we quantified centriole number during the substages of meiotic prophase I, using antibodies to detect two different centriole components (Figs 3, EV3A and B, and EV4A and B). Like the control, the Plk1 cKO, Aurka cKO, and Aurka cHet spermatocytes underwent a single round of centriole duplication during the early stages of meiotic prophase (Figs 3A and B, and EV3A and B). In contrast, 21% of Plk1 cHet spermatocytes underwent centriole amplification in prophase I. Plk1 cHet spermatocytes undergo a first round of centriole duplication during the leptotene stage, just as observed for control (Fig 3A and B). However, spermatocytes isolated from Plk1 cHet mice possess a significantly greater number of centrioles in pachytene and diplotene stages compared with control (average of five centrioles compared with four in the control), and CETN3 protein levels were elevated (Figs 3A and B, EV3C–F, and EV4A and B). We also assessed mice harboring ubiquitous heterozygous deletion of Plk1, which results in reduced PLK1 protein levels in the testis and leads to a similar incidence of multipolar metaphase I spermatocytes compared with the Plk1 cHet (Fig EV3G–I).

Figure 3. Centriole duplication and centrosome separation patterns in PLK1 and AURKA mutant spermatocytes.

-

ASpermatocytes were immunolabeled against PCNT (red), CETN3 (green), and SYCP3 (blue) and stained with DAPI (upper right inset). Zoomed images of the centrosome are shown in the bottom left inset. Scale bars = 5 μm.

-

BQuantification of the number of CETN3 foci per spermatocyte. n = 30 for each meiotic prophase substage. Bars and error bars show mean ± SEM.

-

CSpermatocytes were immunolabeled against PCNT (red), CETN3 (green), and SYCP3 (blue) and stained with DAPI (upper right inset). Zoomed images of the centrosome are shown in the bottom and top left insets. Scale bars = 5 μm.

-

DQuantification of the number of CETN3 foci per spermatocyte. n = 30 for each meiotic prophase substage. Bars and error bars show mean ± SEM. P values obtained from two‐tailed Mann–Whitney t‐test. **P < 0.01.

-

ECentrosome (PCNT) separation was scored per spermatocyte. Three biological replicates were analyzed with > 30 metaphase I spermatocytes assessed per replicate using the four centrosome separation classifications defined in Fig 1C. Bars and error bars show mean ± SEM. P values obtained from two‐tailed Student’s t‐test comparing the percent of unseparated centrosomes in each mouse mutant to control. n.s. (not significant), ***P < 0.001.

Figure EV3. Additional analysis of CETN3 in Aurka cHet, Plk1 cHet, and Plk1 Het spermatocytes.

-

ASpermatocytes from control and Aurka cHet mice were immunolabeled against PCNT (red), CETN3 (green), and SYCP3 (blue) and stained with DAPI (upper right inset). Zoomed images of the centrosome are shown in the bottom left inset. Note: control images from Fig 3A. Scale bars = 5 μm.

-

BQuantification of the number of CETN3 foci per spermatocyte (n = 30) at each meiotic prophase substage. Note: control CETN3 foci numbers from Fig 3A.

-

CWestern blots of CETN3 from protein extracts obtained from 19dpp and 22dpp control, Aurka cKO, and Plk1 cKO whole testes (C) were performed in triplicate. Total protein stained with 2,2,2‐Trichloroethanol (TCE) display protein loading.

-

DQuantification of relative band intensity for CETN3 presented in C obtained from three technical replicates.

-

EWestern blots of CETN3 from protein extracts isolated from control and Plk1 cHet whole testes at 16, 19, and 22 dpp were performed in triplicate. Total protein stained with 2,2,2‐Trichloroethanol (TCE) display protein loading.

-

FQuantification of relative band intensity for CETN3 presented in E from three technical replicates.

-

GWestern blots of PLK1 from protein extracts obtained from 16dpp control, and Plk1 Het whole testes were performed in triplicate. Total protein stained with 2,2,2‐Trichloroethanol (TCE) display protein loading.

-

HQuantification of relative band intensity for PLK1 presented in G from three technical replicates.

-

ISpindle pole number per primary spermatocyte was quantified for control, and Plk1 Het mice. n = 3 technical replicates with > 20 metaphase I spermatocytes analyzed per genotype in each experiment.

Data information: For graphs (B, D, F, H, and I) bars and error bars show mean ± SEM. P values obtained from two‐tailed Student’s t‐test. *P < 0.05, *P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. For the Western blot shown in C, the same samples were used for blotting in Fig 4E. For the Western blot shown in E, the same samples were used for blotting in Figs 4F, and 5C. Therefore, the TCE images are the same. Full Western blot images and replicates are presented in Source Data for Fig EV3.

Figure EV4. Additional assessment of centriole numbers.

-

ASpermatocytes were immunolabeled against alpha‐TUB (red) and CENTRIN (green) and stained with DAPI (upper right inset). Zoomed images of the centrosome are shown in the bottom left inset. Scale bars = 5 μm.

-

BQuantification of the number of CENTRIN foci per spermatocyte from three biological replicates (n = 60 metaphase I spermatocytes quantified per genotype). Bars and error bars show mean ± SEM. P values obtained from two‐tailed Mann–Whitney t‐test. ***P < 0.001.

The centriole number in Plk1 cHet prophase spermatocytes reached up to eight centrioles, which indicates that each centriole undergoes an additional round of duplication (Figs 3A and B, EV3C–F, and EV4A and B). Centrioles duplicate once prior to chromosome segregation during meiosis I and again prior to meiosis II (Figs 1 and EV1). These data suggest that wild‐type expression levels of PLK1 are needed to prevent the second round of centriole duplication from occurring prior to the first meiotic division. Further, Plk1 haploinsufficiency can lead to multipolar spindles and chromosome missegregation during spermatogenesis (Figs 2J and EV3I).

Finally, by crossing mice harboring the Aurka and Plk1 flox alleles, we obtained male mice that were compounded for the Aurka cKO and Plk1 cHet mutations. From assessment of CETN3 number during meiotic progression, we determined that centriole overduplication was evident in Aurka cKO; Plk1 cHet compound mutant spermatocytes during meiotic prophase, demonstrating that absence of Aurora A kinase does not prevent centriole overduplication when PLK1 levels are reduced via the Plk1 cHet mutation (Fig 3C and D).

Centrosome separation is blocked in Plk1 and Aurka cKOs during meiosis I

The majority of Plk1 cKO and Aurka cKO spermatocytes formed monopolar spindles (Fig 2I and J) but successfully underwent centriole duplication during meiotic prophase (Fig 3A and B). Therefore, we hypothesized that Plk1 cKO and Aurka cKO spermatocytes have centrosome separation defects. We closely classified the stages of centrosome separation, which commences during the diplonema to diakinesis transition (initial separation) and continues during diakinesis (intermediate separation), until centrosomes are situated on opposite sides of the chromatin (pole separation; Fig 1C and D). At diakinesis, most Plk1 cKO and Aurka cKO spermatocytes displayed initial centrosome separation but did not reach the intermediate or pole separation stages (Fig 3A and E). These observations demonstrate that PLK1 and Aurora A kinase are critical for centrosome separation prior to meiosis I, which is essential for the formation of bipolar spindles and homologous chromosome segregation.

In addition, centrosome separation during meiosis I was defective in Aurka cKO; Plk1 cHet compound mutant spermatocytes, indicating that Plk1 haploinsufficiency and centriole overduplication does not override the inability to undergo centrosome separation due to the absence of Aurora A kinase (Fig 3D–E).

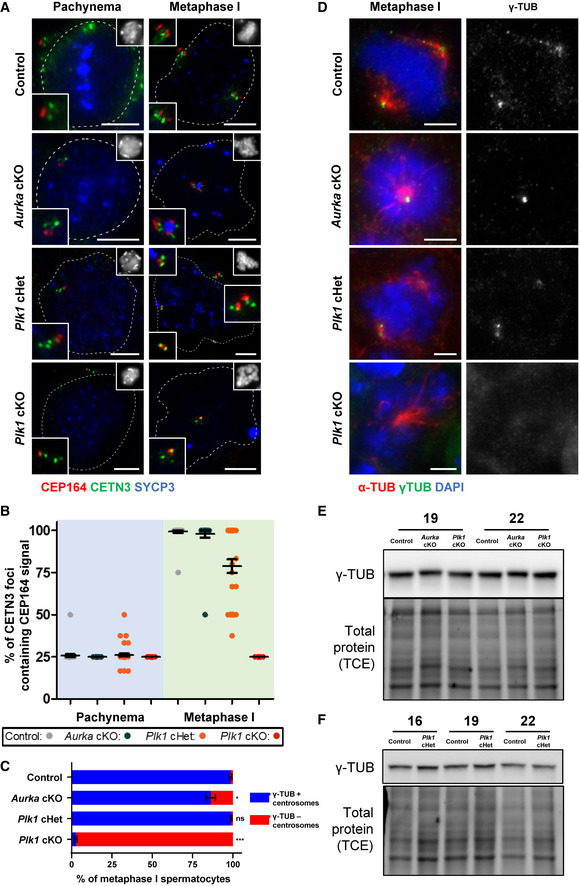

Centriole maturation during spermatogenesis is dependent on PLK1 function

During the G2 phase of mitosis, the oldest of the two parental centrioles is fully mature and competent to function as a basal body for ciliogenesis, a feature indicated by the presence of distal appendages (Inaba & Mizuno, 2016). Prior to centrosome separation and mitosis, the younger parental centriole acquires distal appendages, whereas the daughter centrioles do not acquire them until the subsequent mitotic division (Nigg & Holland, 2018). In spermatogenesis, distal appendages are essential for sperm flagella formation (Inaba & Mizuno, 2016). We hypothesized that each parent and daughter centriole formed during meiosis I must acquire distal appendages to ensure that each spermatid can form a flagellum during spermiogenesis. Therefore, we assessed the localization of distal appendage component, CEP164 during meiosis I (Fig 4A and B). In control pachytene‐stage spermatocytes, one of the four centrioles harbored CEP164 signal, presumably the oldest of the two parental centrioles. By metaphase I stage all four centrioles in control spermatocytes harbor CEP164 signal, indicating that each centriole has matured to contain distal appendages. The association of CEP164 to every centriole at metaphase I during spermatogenesis is a novel finding, given that daughter centrioles do not form distal appendages at metaphase in mitotic cells (Nigg & Holland, 2018). Nevertheless, it is possible that daughter centriole distal appendages in metaphase I stage spermatocytes are not yet functional. Elucidating the functionality of distal appendages during spermatogenesis will be an interesting avenue for future research. Distal appendage acquisition in spermatocytes isolated from Aurka cKO displayed the same pattern as control, despite arresting with condensed chromosomes surrounding a monopolar spindle and failing to proficiently separate spindle poles (Figs 2J, 3, 4A and B). Although Plk1 cKO spermatocytes arrest in a strikingly similar stage as Aurka cKO spermatocytes, Plk1 cKO spermatocytes remained with a single centriole with CEP164 signal (Fig 4A and B). These observations indicate that PLK1 is required for distal appendage acquisition following centriole duplication during meiotic prophase of spermatogenesis. Spermatocytes isolated from the Plk1 cHet mice form up to eight centrioles during meiotic prophase (Fig 3A–C). At pachynema, the average number of CEP164‐positive centrioles in Plk1 cHet spermatocytes is similar to control (average of 26% of centrioles compared with 25.7% in control). However, in most cases, not all centrioles had a CEP164 signal in Plk1 cHet metaphase I spermatocytes (average of 78.8% of centrioles compared with 99.2% in control). Taken together, our data suggest that PLK1 is critical for the construction of distal appendages on centrioles, ensuring centriole maturation, and, thus, the ability to form functional sperm.

Figure 4. Centriole and centrosome maturation defects are observed in Plk1 cKO spermatocytes.

-

ASpermatocytes were immunolabeled against CETN3 (green), CEP164 (red), and SYCP3 (blue) and stained with DAPI (upper right inset). Zoomed images of the centrosome are shown in the bottom and top left insets. Scale bars = 5 μm.

-

BThe percent of centrioles containing CEP164 distal appendages was quantified from three biological replicates (n = 30 total cells) in control, Aurka cKO, Plk1 cHet, and Plk1 cKO spermatocytes at the pachytene stage of meiotic prophase and metaphase I.

-

CQuantification of gamma‐tubulin positive centrosomes per metaphase I spermatocyte. Immunolabeling was performed on three biological replicates, with ≥ 20 spermatocytes quantified per replicate. The total number of cells quantified for control, Aurka cKO, Plk1 cHet, and Plk1 cKO mice were 137, 169, 198, and 198, respectively.

-

DSpermatocytes were immunolabeled against gamma‐tubulin (green), and alpha‐tubulin (red) and stained with DAPI (blue). Plk1 and Aurka cKO spermatocytes arrest at a prometaphase stage. Scale bars = 5 μm.

-

E, FWestern blots of gamma‐tubulin from protein extracts obtained from 19dpp and 22dpp control, Aurka cKO, and Plk1 cKO spermatocytes (E). Protein extracts from control and Plk1 cHet spermatocytes at 16, 19, and 22 dpp (F). Total protein stained with 2,2,2‐Trichloroethanol (TCE) display protein loading.

Data information: For graphs (B, C) bars and error bars show mean ± SEM. P values obtained from two‐tailed Student’s t‐test. n.s. (not significant), *P < 0.05, and ***P < 0.001. For the Western blot shown in E, the same samples were used for blotting in Fig EV3C. For the Western blot shown in F, the same samples were used for blotting in Figs 5C and EV3E. Therefore, the TCE images are the same for these blots. Full Western blot images and replicates are presented in Source Data for Fig 4.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Centrosome maturation during spermatogenesis is dependent on PLK1 function

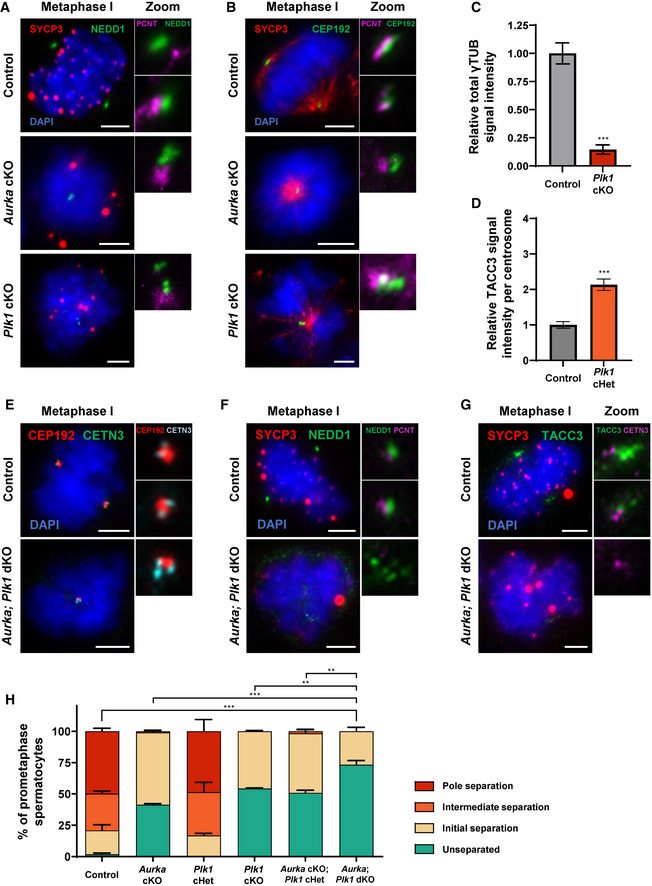

Prior to the formation of a bipolar spindle, centrosomes undergo a maturation process that involves accumulation of PCM proteins. Centrosome proteins CEP192 and NEDD1 (Neural Precursor Cell Expressed Developmentally Down‐Regulated Protein 1) are essential components of the maturation machinery, as they recruit and anchor gamma‐tubulin ring complexes (γTuRC) that execute major microtubule nucleation functions (Dictenberg et al, 1998; Haren et al, 2006; Gomez‐Ferreria et al, 2007; Zhang et al, 2009). In control metaphase I spermatocytes, CEP192 and NEDD1 localized to the outer edge of the PCM (Fig EV5A and B). Although Plk1 cKO and Aurka cKO spermatocytes fail to undergo centrosome separation and arrest with condensed chromosomes attached to monopolar spindles, we observed that CEP192 and NEDD1 localized normally to the outer edge of the PCM (Fig EV5A and B).

Figure EV5. Additional assessment of centrosome maturation markers in Aurka cKO, Plk1 cKO, and Aurka; Plk1 dKO spermatocytes.

-

ASpermatocytes were immunolabeled against NEDD1 (green), SYCP3 (red), and PCNT (magenta) and stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 5 μm.

-

BSpermatocytes were immunolabeled against CEP192 (green), SYCP3 (red), and PCNT (magenta) and stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 5 μm.

-

CRelative γTUB signal intensity was calculated from three biological replicates (n = 15 prometaphase spermatocytes assessed per genotype) in control and Plk1 cKO spermatocytes seen in Fig 4D.

-

DRelative TACC3 signal intensity per centrosome was calculated from three biological replicates (n = 15 prometaphase spermatocytes assessed per genotype) in control and Plk1 cHet spermatocytes seen in Fig 5A.

-

ESpermatocytes were immunolabeled against CETN3 (green), and CEP192 (red) and stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 5 μm. Subpanels are zooms for each spindle pole with CEP192 (red) and CETN3 (teal) shown.

-

FSpermatocytes were immunolabeled against NEDD1 (green), SYCP3 (red), and PCNT (magenta) and stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 5 μm. Subpanels are zooms for each spindle pole with NEDD1 (green) and PCNT (purple) shown.

-

GSpermatocytes were immunolabeled against TACC3 (green), SYCP3 (red), and PCNT (magenta) and stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars = 5 μm. Subpanels are zooms for each spindle pole with TACC3 (green) and CETN3 (purple) shown.

-

HCentrosome (PCNT) separation was scored per spermatocyte. Data from Figs 3E and 6B are compiled to allow for statistical comparison between all genotypes. Three biological replicates were analyzed with > 30 metaphase I spermatocytes assessed per replicate using the four centrosome separation classifications defined in Fig 1C. Statistical tests compare the percent of unseparated centrosomes in Aurka; Plk1 dKO spermatocytes to the indicated genotype.

Data information: Plk1 and Aurka cKO spermatocytes arrest at a prometaphase stage. For all graphs (C, D, and H) bars and error bars show mean ± SEM. P values obtained from two‐tailed Student’s t‐test. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

A key feature of fully mature centrosomes is the successful recruitment of γTuRC (Wiese & Zheng, 2006). Therefore, we assessed the localization and expression of γ‐tubulin to spindle poles in primary spermatocytes (Fig 4C and D). In control metaphase I spermatocytes, γ‐tubulin signal was detected at both spindle poles (Fig 4C and D). γ‐tubulin was also observed to colocalize with the single spindle pole in Aurka cKO spermatocytes and the multiple spindle poles characteristic to the Plk1 cHet spermatocytes (Fig 4C and D). In contrast, γ‐tubulin failed to localize to the spindle pole in Plk1 cKO primary spermatocytes, although the γ‐tubulin protein levels were not altered (Figs 4C–F, and EV5C). Collectively, these observations demonstrate that PLK1 is required for γ‐tubulin recruitment to maturing centrosomes in primary spermatocytes. It has previously been shown that while γ‐tubulin is not absolutely required for microtubule nucleation, it is important for microtubule organization at the centrosome and spindle assembly (Wiese & Zheng, 2006; O’Toole et al, 2012).

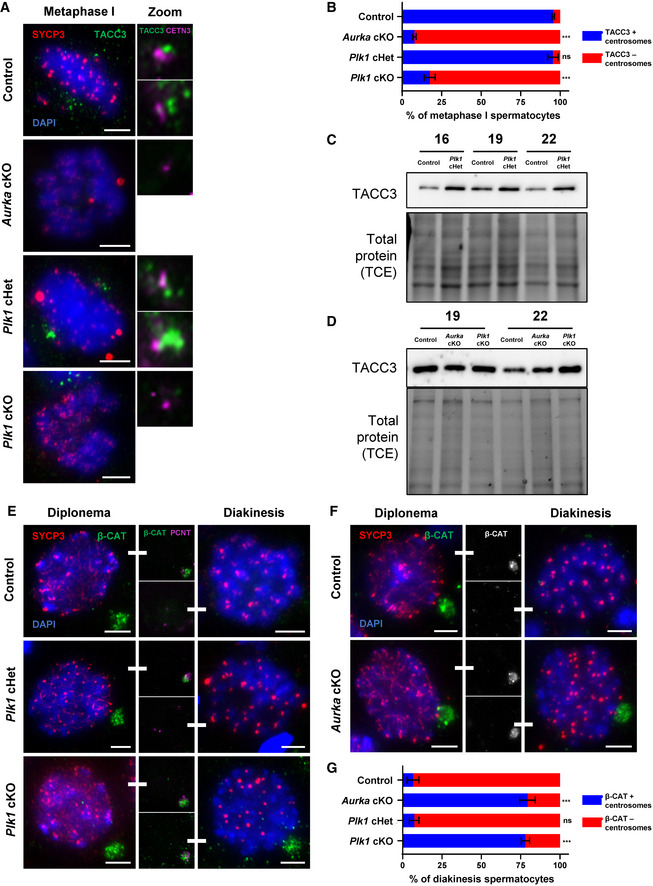

Aurora A and PLK1 are required for proficient localization of TACC3

TACC3 (Transforming Acidic Coiled‐Coil Containing Protein 3) has been shown to be a substrate for Aurora A kinase in mitotic cells, and TACC3 phosphorylation is important for regulating centrosome maturation and stabilizing centrosomal microtubules (Barros et al, 2005; Burgess et al, 2018). Recently, TACC3 was characterized to be the major component of the liquid‐like spindle domain (LISD) in mouse oocytes, which is essential for the stabilization of microtubules emanating from acentriolar MTOCs (So et al, 2019; Little & Jordan, 2020).

In control metaphase I spermatocytes, TACC3 associates on either side of the aligned chromosomes and an accumulation of TACC3 signal colocalizes with centrioles (Fig 5A and B). This pattern of TACC3 localization was also observed in Plk1 cHet metaphase I spermatocytes. However, the TACC3 signal intensity per centrosome was higher compared with control metaphase I spermatocytes, and this was complemented by an increase in total TACC3 protein levels in Plk1 cHet spermatocyte extracts compared with control (Figs 5A–C, and EV5D). The increase in TACC3 signal is likely correlated with the increase in centrioles and separated centrosomes observed in Plk1 cHet primary spermatocytes (Fig 3). In contrast to control, TACC3 signal was diminished in Plk1 cKO spermatocytes and not detected in Aurka cKO spermatocytes at an equivalent stage of meiosis I (Fig 5A and B). Aberrant localization of TACC3 at spindle poles in Plk1 cKO and Aurka cKO spermatocytes was not accompanied with a reduction of TACC3 protein levels compared with control extracts (Fig 5D).

Figure 5. The localization of AURKA and PLK1 substrates is perturbed in Aurka cKO and Plk1 cKO spermatocytes.

-

ASpermatocytes were immunolabeled against TACC3 (green), SYCP3 (red), and CETN3 (magenta) and stained with DAPI (blue). Zoom images of the centrosomes are presented to the right. Scale bars = 5 μm.

-

BQuantification of TACC3‐positive centrosomes per metaphase I spermatocyte. Immunolabeling was performed on three biological replicates, with ≥ 20 spermatocytes quantified per replicate. The total number of cells quantified for control, Aurka cKO, Plk1 cHet, and Plk1 cKO mice were 97, 103, 96, and 105, respectively.

-

C, DWestern blots of TACC3 from protein extracts obtained from 19dpp and 22dpp control, Aurka cKO, and Plk1 cKO spermatocytes (D). Protein extracts from control and Plk1 cHet spermatocytes at 16, 19, and 22 dpp (C). Total protein stained with 2,2,2‐Trichloroethanol (TCE) display protein loading.

-

E, FSpermatocytes were immunolabeled against beta‐catenin (green), SYCP3 (red), and PCNT (magenta) and stained with DAPI (blue). Middle columns emphasize beta‐catenin signal in diplonema and diakinesis spermatocytes. Scale bars = 5 μm.

-

GQuantification of beta‐catenin positive centrosomes per spermatocyte at diakinesis. Immunolabeling was performed on three biological replicates, with ≥ 20 spermatocytes quantified per replicate. The total number of cells quantified for control, Aurka cKO, Plk1 cHet, and Plk1 cKO mice were 89, 106, 122, and 93, respectively.

Data information: For graphs (B, G) bars and error bars show mean ± SEM. P values obtained from two‐tailed Student’s t‐test. n.s. (not significant) and ***P < 0.001. For the Western blot shown in C, the same samples were used for blotting in Figs 4F and EV3E. Therefore, the TCE images are the same. Full Western blot images and replicates are presented in Source Data for Fig 5.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Centrosome separation defects are due to an inability to remove the intercentrosomal linker

As Plk1 cKO and Aurka cKO spermatocytes display an inability to undergo centrosome separation (Fig 3), it is possible that these kinases contribute to the degradation of intercentrosomal linkers and the generation of pushing and pulling forces that drive centrosome separation during meiosis. The intercentrosomal linker is comprised of an array of fibrous proteins, among which is β‐catenin (Bahmanyar et al, 2008; Mbom et al, 2014).

In control diplonema spermatocytes, β‐catenin colocalizes with PCNT at the centrosome (Fig 5E–G). By diakinesis, following centrosome separation, β‐catenin signal is not detected in control spermatocytes. The same localization pattern was observed in stage matched Plk1 cHet spermatocytes (Fig 5E and G). Plk1 cKO and Aurka cKO diplonema spermatocytes also harbor β‐catenin at the centrosome (Fig 5E–G). However, β‐catenin signal does not diminish in Plk1 cKO and Aurka cKO spermatocytes staged at diakinesis. These observations suggest that PLK1 and Aurora A are required to ensure removal of intercentrosomal linkage, and, thus, centrosome separation.

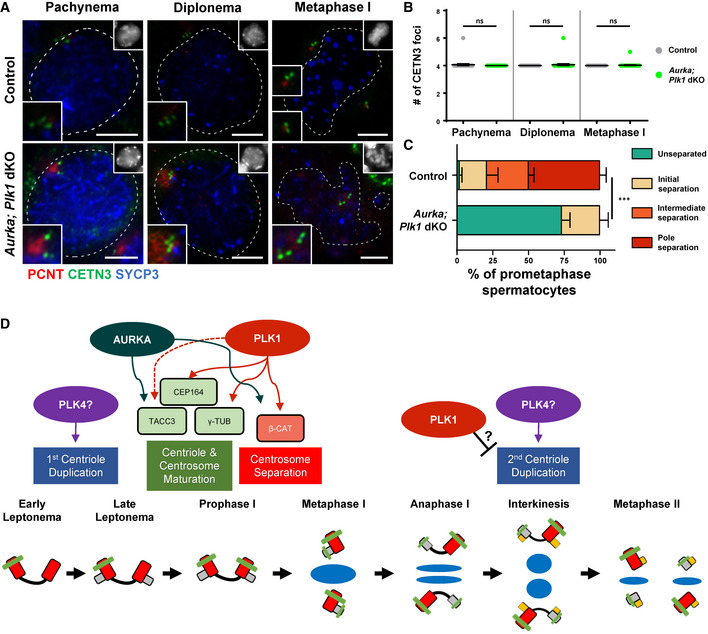

Combined absence of PLK1 and Aurora A compounds centrosome maturation and separation defects

Assessment of Plk1; Aurka double cKO (dKO) spermatocytes demonstrated that loss of both PLK1 and Aurora A did not affect centriole duplication during meiotic prophase (Fig 6A and B). In addition, the Plk1; Aurka dKO did not result in a failure to localize centrosome components, CEP192 or NEDD1 (Fig EV5E and F). However, Plk1; Aurka dKO did result in a more severe centrosome separation phenotype compared to the Aurka cKO and Plk1 cKO spermatocytes (Figs 3A and C, 6A and C, and EV5G and H). This compounded centrosome separation defect is expected as we have shown that PLK1 and Aurora A are required for γ‐tubulin and TACC3 localization to the centrosome, respectively, our data suggest that although PLK1 and Aurora A kinase have overlapping function regarding centrosome maturation both have unique roles to play. We show that Aurora A is primarily involved in TACC3 localization. Whereas, PLK1 is not only important for ensuring γ‐tubulin loading during centrosome maturation, which indirectly affects TACC3 localization, but also for centriole duplication and maturation (Fig 6D).

Figure 6. Centrosome separation defects are compounded in spermatocytes lacking both PLK1 and AURKA.

-

ASpermatocytes were immunolabeled against PCNT (red), CETN3 (green), and SYCP3 (blue) and stained with DAPI (upper right inset). Zoomed images of the centrosome are shown in the bottom left inset. Scale bars = 5 μm.

-

BQuantification of the number of CETN3 foci per spermatocyte (n = 30) at each meiotic prophase substage.

-

CCentrosome (PCNT) separation was assessed in Aurka; Plk1 dKO spermatocytes. Three biological replicates were analyzed with > 30 metaphase I spermatocytes assessed per replicate using the four centrosome separation classifications defined in Fig 1C.

-

DAurora A‐ and PLK1‐mediated regulation of meiotic centrosome biogenesis during spermatogenesis. After spermatocytes enter meiotic prophase and complete the first round of centriole duplication, presumably stimulated by PLK4, the centrioles must mature in order to effectively act as MTOCs during the first meiotic division. PLK1 and AURKA regulate this maturation process by ensuring the recruitment of various maturation factors including TACC3, CEP164, and γ‐tubulin (γ‐TUB). PLK1 and AURKA are also required for the efficient degradation of β‐catenin (β‐CAT), a necessary step to ensure centrosome separation prior to bipolar spindle establishment at metaphase I. The mechanism by which the first and second rounds of centriole duplication are restricted to early meiotic prophase I and interkinesis, respectively, is not understood and warrants further investigation. However, we find that high levels of PLK1 are necessary to avoid a premature second round of centriole duplication, which insinuates that PLK1 counteracts the centriole duplication function of PLK4.

Data information: For graphs (B and C) bars and error bars show mean ± SEM. P values obtained from two‐tailed Student’s t‐test. n.s. (not significant) and ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Centriole duplication and maturation during spermatogenesis

Centriole duplication in mitotically dividing cells is initiated at the onset of S‐phase, when PLK4 stimulates construction of the procentriole cartwheel structure perpendicular to each parent centriole within the centrosome (Fig 3; Kleylein‐Sohn et al, 2007; Kratz et al, 2015; Moyer & Holland, 2019). Following procentriole formation, PLK4 is rapidly degraded to ensure only a single round of centriole duplication occurs. The procentriole is elongated by the recruitment of centrin proteins (CETN1–4) throughout S‐phase and G2‐phase while simultaneously recruiting additional pericentrosomal proteins that drive centrosome maturation. Here, we show that centriole duplication occurs twice during spermatogenesis, once prior to meiosis I to mediate segregation of homologous chromosomes, and again prior to meiosis II to facilitate segregation of sister chromatids. Thus, centriole duplication in spermatocytes is in stark contrast to mitotically dividing cells, and there is a plethora of questions that remain to be answered. For instance, how is PLK4 involved and regulated during spermatogenesis? Our prior work showed that PLK4 levels remain high during the first wave of spermatogenesis and localize to the centrosomes, which indicates that PLK4 is not necessarily degraded during spermatogenesis as it is in mitotic cells following procentriole formation (Jordan et al, 2012). Future work that focuses on the role of PLK4 during mammalian spermatogenesis is needed to help further elucidate its function and how it is regulated.

In this study, we show that Aurora A and PLK1 are not required for centriole duplication during prophase of spermatogenesis, as centrioles duplicate normally in Aurka and Plk1 cKO spermatocytes. However, we provide evidence to suggest that wild‐type PLK1 levels are required to avoid overduplication of centrioles during meiotic prophase, as many Plk1 cHet spermatocytes harbor up to eight centrioles instead of four by the pachytene stage. Our findings imply that PLK1 levels are finely tuned to avoid abnormal licensing of the second round of centriole duplication prior to meiosis II. In mitotic cells, aberrant reduplication of centrioles is thought to be caused by disengagement of the parent and daughter centrioles that are normally in close orthogonal association with one another (Duensing et al, 2007; Peel et al, 2007; Loncarek et al, 2010; Hatano & Sluder, 2012; Shukla et al, 2015). PLK1 has been shown to be required to drive centriole disengagement, distancing, and centriole maturation, which are prerequisites for centriole duplication (Loncarek et al, 2010; Hatano & Sluder, 2012; Shukla et al, 2015). Therefore, it is a little counterintuitive that the reduction of PLK1 expression levels would cause aberrant centriole overduplication. One possibility is that PLK1 levels must be high to counteract the function and/or localization of PLK4 following centriole duplication during early prophase of spermatogenesis. One prior study reported the assessment of a heterozygous mutation of Plk1 in mice, demonstrating that reduced PLK1 levels leads to aneuploidy (Lu et al, 2008). However, the cause of aneuploidy was not addressed. Taken together, there is a clear need for further in vivo assessment of Plk1 heterozygous mutant mice to address the roles of PLK1 during centriole biogenesis.

Centriole maturation during spermatogenesis also contrasts what we would expect from our knowledge in mitotically dividing cells. During early G2 phase of mitosis, only the mature parent centriole harbors appendages. It is not until late G2/M phase that the second parent centriole obtains appendages, and the two newly synthesized centrioles remain unmodified in this context until a subsequent mitotic division (Bettencourt‐Dias & Glover, 2007; Nigg & Holland, 2018). We show that by metaphase I all four centrioles (both parent and both daughter centrioles) have distal appendages. We believe this ensures that each spermatid can form a flagella during spermiogenesis, as distal appendages are essential for sperm flagella formation (Inaba & Mizuno, 2016). We show that PLK1 is required for the second parent and newly synthesized centrioles to acquire distal appendages during meiosis I. Our finding complements what has been reported from assessment of mitotic cells, where PLK1 triggers the immature parent centriole to acquire appendages (Kong et al, 2014). However, the fact that all four centrioles possess distal appendages prior to meiosis I was unexpected based on our understanding of centriole maturation during mitosis (Kong et al, 2014). This meiosis‐specific feature may occur because centrioles must duplicate immediately after meiosis I as secondary spermatocytes rapidly undergo meiosis II. Furthermore, the two centrioles inherited by each spermatid may both require distal appendages in order for elongation and flagella formation to occur normally (Avasthi & Marshall, 2012).

Centrosome maturation, separation, and function during spermatogenesis

In mammals, centrosome maturation is a process featured by the accumulation of additional PCM proteins that increases their microtubule nucleation capacity. The PCM is comprised of hundreds of proteins, including a matrix of PCNT, CEP192, and NEDD1 which together recruit and anchor gamma‐tubulin ring complexes (γTuRC) that execute major microtubule nucleation functions (Dictenberg et al, 1998). Research using a human cell lines has demonstrated that centrosome maturation is initiated when PLK1 directly phosphorylates PCNT, which subsequently recruits CEP192, NEDD1 (a γTuRC adaptor protein), γ‐tubulin, AURKA, and PLK1 to the centrosomes (Haren et al, 2006; Gomez‐Ferreria et al, 2007; Zhang et al, 2009; Lee & Rhee, 2011; Sdelci et al, 2012; Joukov et al, 2014). Aurora A kinase activates, via autophosphorylation of its T‐loop (T288; Walter et al, 2000; Joukov et al, 2010, 2014). Aurora A then activates PLK1 by phosphorylating its T‐loop (T201), which facilitates PLK1 docking onto CEP192 (Walter et al, 2000; Joukov et al, 2010, 2014). The CEP192‐bound PLK1 then phosphorylates CEP192, and other pericentriolar material proteins, including NEDD1, which increases its anchoring capacity for γTuRC onto centrosomes (Zhang et al, 2009). In our study, we showed that although CEP192 and NEDD1 localization to the centrosome was not affected, PLK1 was essential for γ‐tubulin recruitment to the centrosome, which is aligned with the known functions for PLK1 in mitotic cells. In contrast, Aurora A was not required for y‐tubulin localization but was essential for recruitment of TACC3. TACC3 is a known substrate of Aurora A and functions at the centrosome to regulate microtubule nucleation, which stabilizes the spindle apparatus and promotes spindle elongation (Gergely et al, 2003; Kinoshita et al, 2005; Lioutas & Vernos, 2013; Burgess et al, 2015). Our findings suggest that PLK1 activation with respect to mediating γ‐tubulin localization is independent of AURKA. It is possible that PLK1 can self‐activate or be activated by another cell cycle kinase such as cyclin‐dependent kinases to mediate γ‐tubulin localization during spermatogenesis (Gheghiani et al, 2017; Colicino & Hehnly, 2018).

In addition, we showed that PLK1 and Aurora A are required for centrosome separation during meiosis I to ensure formation of a bipolar spindle. Mutation of Plk1 or Aurka during meiosis resulted in an inability to deplete β‐catenin from centrosomes. We believe that this observation is aligned with centrosome separation processes in mitotically diving cells, where β‐catenin localizes to centrosomes and functions to ensure proper centrosome disjunction and bipolar spindle formation (Kaplan et al, 2004; Bahmanyar et al, 2008). Phosphorylation of β‐catenin is required for destabilizing the linker proteins, which stimulates centrosome separation (Mbom et al, 2014). PLK1 has been shown to regulate the phosphorylation of β‐catenin by NIMA‐related protein kinase 2 (NEK2; Mardin et al, 2011; Mbom et al, 2014). Phosphorylation of β‐catenin is required for destabilizing the protein by targeting it for degradation, and this is required for centrosome separation (Mbom et al, 2014).

Taken together, PLK1 and Aurora A function in overlapping but distinct pathways of centrosome biogenesis during spermatogenesis that are essential for bipolar spindle formation, and, thus, critical for accurate chromosome segregation (Fig 6D).

Conclusion

Regulation of centriole duplication, maturation, and centrosome biogenesis during mammalian meiosis is remarkably different from mitosis and sexually dimorphic. Our work has mapped the steps required for these processes during spermatogenesis (Fig 1F and 6D). Failure of MTOC processes during gametogenesis can result in gamete aneuploidy, developmental defects, spontaneous abortion, and infertility. Thus, further assessment of MTOC dynamics and biogenesis during gametogenesis, and determining germ cell‐specific MTOC components and regulators are of paramount importance.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All mice were bred at Johns Hopkins University (JHU, Baltimore, MD) and the Jackson Laboratory (JAX) in accordance with the National Institutes of Health and U. S. Department of Agriculture criteria, and protocols for their care and use were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) of JHU and JAX.

Mice

Mice harboring a Plk1 cKO allele (C57BL/6N; Plk1tm1c(EUCOMM)Hmgu) and mice harboring a Aurka cKO allele (C57BL/6N; Aurkatm1c(EUCOMM)Hmgu/J) were acquired through the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC; www.mousephenotype.org). Within the Plk1 cKO allele are two loxP sites that flank the 3rd exon of Plk1 (termed the Plk1 flox allele; Fig EV2A). Within the Aurka cKO allele are two loxP sites that flank the 3rd exon of Aurka (termed the Aurka flox allele; Fig EV2H). Conditional mutation was achieved by crossing in a hemizygous Cre recombinase transgene under the control of meiosis‐specific promoters. In this study, the promoter for Spo11 (Tg(Spo11‐cre)1Rsw) and the promoter for Hspa2 (Tg(Hspa2‐cre)1Eddy/J) were used to drive Cre recombinase expression (Lyndaker et al, 2013; Hwang et al, 2018).

PCR genotyping

Primers used during this study are described in Table EV2. PCR conditions: 90°C for 2 min; 30 cycles of 90°C for 20 s; 58°C for 30 s; and 72°C for 1 min.

Histology and cryo‐sectioning

For histological assessment, mouse testis tissue was fixed in bouins fixative (Ricca Chemical Company) prior to paraffin embedding. Serial sections 5 μm thick were mounted onto slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For the TUNEL assay, sections were deparafinnized and apoptotic cells were detected using the in situ BrdU‐Red DNA fragmentation (TUNEL) assay kit (Abcam) and counterstained with DAPI.

Tubule squash preparations

Mouse tubule squash preparations were performed as previously described (Wellard et al, 2018). Primary antibodies and dilution used are presented in Table EV3. Secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa 488, 568, or 633 against human, rabbit, goat, and mouse IgG (Life Technologies) were used at 1:500 dilution. Chromatin spreads and tubule squash preparations were mounted in Vectashield + DAPI (4',6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole) medium (Vector Laboratories). Full Z‐stack captured images were utilized to manually identify centrioles, centrosomes, spindle morphology, and chromosome structure.

Western Blot analyses

Protein was extracted from germ cells using RIPA buffer (Santa Cruz) containing 1x protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Protein concentration was calculated using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce), and 20 μg of protein extract was loaded per lane of in a SDS–PAGE gels (Bio‐Rad). To detect proteins > 100 kDa, a 7.5% gel was used, and proteins < 100 kDa were run on a 12% gel. Following protein separation, proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes using Trans‐Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio‐Rad, 12% gel) using the standard 30‐min semi‐dry program (up to 1.0 A; 25 V) or Criterion Blotter (Bio‐Rad, 7.5% gel) at a constant 300 mA for one hour. Primary antibodies and dilution used are presented in Table EV3. For detection of primary antibodies, goat anti‐mouse and goat anti‐rabbit horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated antibodies (Invitrogen) were used as secondary antibodies. Antibody signal was detected via treatment with Bio‐Rad ECL Western blotting substrate and captured using a Syngene XR5 system.

Microscope image acquisition

Tubule squash images were captured using a Zeiss CellObserver Z1 linked to an ORCA‐Flash 4.0 CMOS camera (Hamamatsu), and histology images were captured using a Zeiss AxioImager A2 with an AxioCam ERc 5s (Zeiss) camera or Keyence BZ‐800 and BZ‐X800 Viewer and Analyzer software. Images were processed using ZEN 2012 blue edition imaging software (Zeiss) or BZ‐X800 Viewer and Analyzer software (Keyence). Images were analyzed with the Zeiss ZEN 2012 blue edition image software, and Photoshop (Adobe) was used to prepare figure images.

Author contributions

Project conceptualization and experimental plan: SRW, PWJ. Experiments and analysis: SRW, YZ, CS, XZ, PWJ. Preparation of the Aurka flox mouse line: MM, SAM. Manuscript writing: SRW, PWJ.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Expanded View Figures PDF

Table EV1

Table EV2

Table EV3

Source Data for Expanded View

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 4

Source Data for Figure 5

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Andrew Holland for generously providing antibodies used in this study. This work was funded by NIGMS grant to PWJ (R01GM11755), a NIH grant to SAM (UM1OD023222), and training grant fellowship from the National Cancer Institute (NCI, NIH; CA009110) to SRW.

EMBO Reports (2021) 22: e51023.

Data availability

This study includes no data deposited in external repositories.

References

- Albertson DG, Thomson JN (1993) Segregation of holocentric chromosomes at meiosis in the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans . Chromosome Res 1: 15–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avasthi P, Marshall WF (2012) Stages of ciliogenesis and regulation of ciliary length. Differentiation 83: S30–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahmanyar S, Kaplan DD, Deluca JG, Giddings TH, O’Toole ET, Winey M, Salmon ED, Casey PJ, Nelson WJ, Barth AIM (2008) beta‐Catenin is a Nek2 substrate involved in centrosome separation. Genes Dev 22: 91–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros TP, Kinoshita K, Hyman AA, Raff JW (2005) Aurora A activates D‐TACC‐Msps complexes exclusively at centrosomes to stabilize centrosomal microtubules. J Cell Bio 170: 1039–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt‐Dias M, Glover DM (2007) Centrosome biogenesis and function: centrosomics brings new understanding. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 451–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornens M (2002) Centrosome composition and microtubule anchoring mechanisms. Curr Opin Cell Biol 14: 25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess SG, Peset I, Joseph N, Cavazza T, Vernos I, Pfuhl M, Gergely F, Bayliss R (2015) Aurora‐A‐dependent control of TACC3 influences the rate of mitotic spindle assembly. PLoS Genet 11: e1005345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess SG, Mukherjee M, Sabir S, Joseph N, Gutiérrez‐Caballero C, Richards MW, Huguenin‐Dezot N, Chin JW, Kennedy EJ, Pfuhl M et al (2018) Mitotic spindle association of TACC3 requires Aurora‐A‐dependent stabilization of a cryptic α‐helix. EMBO J 37: e97902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu DS, Shakes DC (2013) Spermatogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol 757: 171–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colicino EG, Hehnly H (2018) Regulating a key mitotic regulator, polo‐like kinase 1 (PLK1). Cytoskeleton 75: 481–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dictenberg JB, Zimmerman W, Sparks CA, Young A, Vidair C, Zheng Y, Carrington W, Fay FS, Doxsey SJ (1998) Pericentrin and gamma‐tubulin form a protein complex and are organized into a novel lattice at the centrosome. J Cell Biol 141: 163–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duensing A, Liu Y, Perdreau SA, Kleylein‐Sohn J, Nigg EA, Duensing S (2007) Centriole overduplication through the concurrent formation of multiple daughter centrioles at single maternal templates. Oncogene 26: 6280–6288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Glover DM (2012) Structured illumination of the interface between centriole and peri‐centriolar material. Open Biol 2: 120104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergely F, Draviam VM, Raff JW (2003) The ch‐TOG/XMAP215 protein is essential for spindle pole organization in human somatic cells. Genes Dev 17: 336–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gheghiani L, Loew D, Lombard B, Mansfeld J, Gavet O (2017) PLK1 activation in late G2 sets up commitment to mitosis. Cell Rep 19: 2060–2073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez‐Ferreria MA, Rath U, Buster DW, Chanda SK, Caldwell JS, Rines DR, Sharp DJ (2007) Human Cep192 is required for mitotic centrosome and spindle assembly. Curr Biol 17: 1960–1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan J, Guichard P, Smith AH, Schwarz H, Agard DA, Marco S, Avidor‐Reiss T (2010) Self‐assembling SAS‐6 multimer is a core centriole building block. J Biol Chem 285: 8759–8770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haren L, Remy MH, Bazin I, Callebaut I, Wright M, Merdes A (2006) NEDD1‐dependent recruitment of the gamma‐tubulin ring complex to the centrosome is necessary for centriole duplication and spindle assembly. J Cell Biol 172: 505–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatano T, Sluder G (2012) The interrelationship between APC/C and Plk1 activities in centriole disengagement. Biol Open 1: 1153–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang G, Verver DE, Handel MA, Hamer G, Jordan PW (2018) Depletion of SMC5/6 sensitizes male germ cells to DNA damage. Mol Biol Cell 29: 3003–3016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba K, Mizuno K (2016) Sperm dysfunction and ciliopathy. Reprod Med Biol 15: 77–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inselman AL, Nakamura N, Brown PR, Willis WD, Goulding EH, Eddy EM (2010) Heat shock protein 2 promoter drives Cre expression in spermatocytes of transgenic mice. Genesis 48: 114–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan PW, Karppinen J, Handel MA (2012) Polo‐like kinase is required for synaptonemal complex disassembly and phosphorylation in mouse spermatocytes. J Cell Sci 125(Pt 21): 5061–5072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joukov V, De Nicolo A, Rodriguez A, Walter JC, Livingston DM (2010) Centrosomal protein of 192 kDa (Cep192) promotes centrosome‐driven spindle assembly by engaging in organelle‐specific Aurora A activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 21022–21027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joukov V, Walter JC, De Nicolo A (2014) The Cep192‐organized aurora A‐Plk1 cascade is essential for centrosome cycle and bipolar spindle assembly. Mol Cell 55: 578–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DD, Meigs TE, Kelly P, Casey PJ (2004) Identification of a role for beta‐catenin in the establishment of a bipolar mitotic spindle. J Biol Chem 279: 10829–10832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita K, Noetzel TL, Pelletier L, Mechtler K, Drechsel DN, Schwager A, Lee M, Raff JW, Hyman AA (2005) Aurora A phosphorylation of TACC3/maskin is required for centrosome‐dependent microtubule assembly in mitosis. J Cell Biol 170: 1047–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleylein‐Sohn J, Westendorf J, Le Clech M, Habedanck R, Stierhof YD, Nigg EA (2007) Plk4‐induced centriole biogenesis in human cells. Dev Cell 13: 190–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong D, Farmer V, Shukla A, James J, Gruskin R, Kiriyama S, Loncarek J (2014) Centriole maturation requires regulated Plk1 activity during two consecutive cell cycles. J Cell Biol 206: 855–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraatz S, Guichard P, Obbineni JM, Olieric N, Hatzopoulos GN, Hilbert M, Sen I, Missimer J, Gönczy P, Steinmetz MO (2016) The human centriolar protein CEP135 contains a two‐stranded coiled‐coil domain critical for microtubule binding. Structure 24: 1358–1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratz AS, Bärenz F, Richter KT, Hoffmann I (2015) Plk4‐dependent phosphorylation of STIL is required for centriole duplication. Biol Open 4: 370–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Rhee K (2011) PLK1 phosphorylation of pericentrin initiates centrosome maturation at the onset of mitosis. J Cell Biol 195: 1093–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leidel S, Gönczy P (2003) SAS‐4 is essential for centrosome duplication in C. elegans and is recruited to daughter centrioles once per cell cycle. Dev Cell 4: 431–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lioutas A, Vernos I (2013) Aurora A kinase and its substrate TACC3 are required for central spindle assembly. EMBO Rep 14: 829–836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TM, Jordan PW (2020) PLK1 is required for chromosome compaction and microtubule organization in mouse oocytes. Mol Biol Cell 31: 1206–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loncarek J, Hergert P, Khodjakov A (2010) Centriole reduplication during prolonged interphase requires procentriole maturation governed by Plk1. Curr Biol 20: 1277–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu LY, Wood JL, Minter‐Dykhouse K, Ye L, Saunders TL, Yu X, Chen J (2008) Polo‐like kinase 1 is essential for early embryonic development and tumor suppression. Mol Cell Biol 28: 6870–6876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyndaker AM, Lim PX, Mleczko JM, Diggins CE, Holloway JK, Holmes RJ, Kan R, Schlafer DH, Freire R, Cohen PE et al (2013) Conditional inactivation of the DNA damage response gene Hus1 in mouse testis reveals separable roles for components of the RAD9‐RAD1‐HUS1 complex in meiotic chromosome maintenance. PLoS Genet 9: e1003320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardin BR, Agircan FG, Lange C, Schiebel E (2011) Plk1 controls the Nek2A‐PP1γ antagonism in centrosome disjunction. Curr Biol 21: 1145–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marjanović M, Sánchez‐Huertas C, Terré B, Gómez R, Scheel JF, Pacheco S, Knobel PA, Martínez‐Marchal A, Aivio S, Palenzuela L et al (2015) CEP63 deficiency promotes p53‐dependent microcephaly and reveals a role for the centrosome in meiotic recombination. Nat Commun 6: 7676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbom BC, Siemers KA, Ostrowski MA, Nelson WJ, Barth AIM (2014) Nek2 phosphorylates and stabilizes β‐catenin at mitotic centrosomes downstream of Plk1. Mol Biol Cell 25: 977–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer TC, Holland AJ (2019) PLK4 promotes centriole duplication by phosphorylating STIL to link the procentriole cartwheel to the microtubule wall. eLife 8: e46054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg EA, Holland AJ (2018) Once and only once: mechanisms of centriole duplication and their deregulation in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19: 297–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole E, Greenan G, Lange KI, Srayko M, Müller‐Reichert T (2012) The role of γ‐tubulin in centrosomal microtubule organization. PLoS One 7: e29795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel N, Stevens NR, Basto R, Raff JW (2007) Overexpressing centriole‐replication proteins in vivo induces centriole overduplication and de novo formation. Curr Biol 17: 834–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder CL, Faruki S, Khodjakov A (2001) The centrosome in vertebrates: more than a microtubule‐organizing center. Trends Cell Biol 11: 413–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatten H, Sun QY (2009) The functional significance of centrosomes in mammalian meiosis, fertilization, development, nuclear transfer, and stem cell differentiation. Environ Mol Mutagen 50: 620–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schvarzstein M, Pattabiraman D, Bembenek JN, Villeneuve AM (2013) Meiotic HORMA domain proteins prevent untimely centriole disengagement during Caenorhabditis elegans spermatocyte meiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: E898–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sdelci S, Schütz M, Pinyol R, Bertran MT, Regué L, Caelles C, Vernos I, Roig J (2012) Nek9 phosphorylation of NEDD1/GCP‐WD contributes to Plk1 control of γ‐tubulin recruitment to the mitotic centrosome. Curr Biol 22: 1516–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla A, Kong D, Sharma M, Magidson V, Loncarek J (2015) Plk1 relieves centriole block to reduplication by promoting daughter centriole maturation. Nat Commun 6: 8077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So C, Seres KB, Steyer AM, Mönnich E, Clift D, Pejkovska A, Möbius W, Schuh M (2019) A liquid‐like spindle domain promotes acentrosomal spindle assembly in mammalian oocytes. Science 364: eaat9557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter AO, Seghezzi W, Korver W, Sheung J, Lees E (2000) The mitotic serine/threonine kinase Aurora2/AIK is regulated by phosphorylation and degradation. Oncogene 19: 4906–4916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Jiang Q, Zhang C (2014) The role of mitotic kinases in coupling the centrosome cycle with the assembly of the mitotic spindle. J Cell Sci 127(Pt 19): 4111–4122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellard SR, Hopkins J, Jordan PW (2018) A seminiferous tubule squash technique for the cytological analysis of spermatogenesis using the mouse model. J Vis Exp 132: e56453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese C, Zheng Y (2006) Microtubule nucleation: gamma‐tubulin and beyond. J Cell Sci 119(Pt 20): 4143–4153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Chen Q, Feng J, Hou J, Yang F, Liu J, Jiang Q, Zhang C (2009) Sequential phosphorylation of Nedd1 by Cdk1 and Plk1 is required for targeting of the gammaTuRC to the centrosome. J Cell Sci 122(Pt 13): 2240–2251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expanded View Figures PDF

Table EV1

Table EV2

Table EV3

Source Data for Expanded View

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 4

Source Data for Figure 5

Data Availability Statement

This study includes no data deposited in external repositories.