Abstract

Women and children are vulnerable to sexual violence in times of conflict, and the risk persists even after they have escaped the conflict area. The impact of rape goes far beyond the immediate effects of the physical attack and has long-lasting consequences. We describe the humanitarian community's response to sexual violence and rape in times of war and civil unrest by drawing on the experiences of Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders and other humanitarian agencies. Health care workers must have a keen awareness of the problem and be prepared to respond appropriately. This requires a comprehensive intervention protocol, including antibiotic prophylaxis, emergency contraception, referral for psychological support, and proper documentation and reporting procedures. Preventing widespread sexual violence requires increasing the security in refugee camps. It also requires speaking out and holding states accountable when violations of international law occur. The challenge is to remain alert to these often hidden, but extremely destructive, crimes in the midst of a chaotic emergency relief setting.

Sexual violence has long seemed an inevitable consequence of war and civil upheaval. In the mid-1990s the world was shocked by stories of widespread and systematic sexual violence in the former Yugoslavia and in Rwanda. Yet these reports simply made the public aware of occurrences that are in fact commonplace in areas affected by conflict. For example, widespread rape of civilian women has also been documented in Bangladesh, Uganda, Myanmar and Somalia.1,2 The problem, however, often remains hidden and poorly addressed by the humanitarian community.

There are signs of improvement in the international community's capacity to document and respond to sexual violence in war. In this article we review recent experiences of nongovernment organizations and United Nations agencies in their efforts to prevent sexual violence and to treat victims in conflict areas. This review should be helpful to medical staff who end up working in conflict areas. Furthermore, we believe that it will increase awareness of the problem in the international medical community, which is crucial for the development of better intervention strategies and the generation of more active responses to advocacy campaigns originating from the field.

The situation in the field

Women and girls are especially vulnerable to sexual violence during war and civil conflict, whether in the midst of fighting, while escaping from their homes, or even once inside camps for refugees or internally displaced people. Many families become separated during the confusion and chaos of flight or when the men leave to fight. Women must then support their families on their own, and they may become easy prey for men seeking to take advantage of their vulnerability. At border crossings, women may be forced to endure rape as a “price of passage.” Even refugee camps may offer no refuge, as women's lack of economic power leaves them open to sexual exploitation and coercion. Many women find themselves living without protection in a culture of violence fed by conflict and social chaos.

Examples are regularly encountered in the field. In 1994 Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) was one of many agencies working in refugee camps that had sprung up overnight when the Rwandan Patriotic Front's victory led to the exodus of an estimated 800 000 Rwandan refugees into neighbouring Zaire. A cholera epidemic broke out almost immediately and claimed the lives of 20 000 people in the initial days alone.3 As relief agencies struggled to control this epidemic, it became apparent that a lack of security within the camps was a major factor hampering relief efforts. The Zairean national army had been chased out of the camps, and security was literally left in the hands of a local Boy Scout troupe. There was little protection for anyone but the strong and well armed.

The resulting insecurity had a devastating impact on refugee midwives working in a maternal health centre inside the camp. Shortly after the centre opened, the midwives confided to MSF doctors that the centre's guards were raping them while on night duty. The midwives were frightened and insisted that the alleged perpetrators not be confronted because of possible retaliation. At the same time, they felt strong pressure to continue working to support their families. In such situations, relief agencies may feel powerless given that they have 2 equally unpleasant options: to close the health centres at night and accept the health risks posed to patients, or to leave them open and accept the security risks posed to staff. In the camps in Zaire it was decided to close the health centres at night until advocacy efforts succeeded in implementing a security force.

Other examples of women's vulnerability to sexual violence have been encountered in conflict areas. In Somalia in the early 1990s, clinics run by nongovernment organizations regularly treated women who had been raped by bandits when they went outside the camp. An indication of the scale of the problem in refugee camps was revealed in a survey done in a Tanzanian camp by the International Rescue Committee. Of the Burundian refugee women interviewed, 26% had been victims of sexual violence during their time in the camp.4 Daily essential tasks such as gathering firewood and collecting water become dangerous activities. In Liberia refugee staff workers would wear trousers under their skirts before they went to collect water, hoping to slow their attackers and increase their chance of escape.

These individual episodes of rape, although widespread, must be distinguished from the systematic rape of women and children that was used as an act of genocide in the former Yugoslavia. Systematic rape in these cases was clearly used as a strategy to spread terror and fear among the population. Moreover, it was aimed at the male combatants who were out of reach. Through a single act of rape, the assailant can humiliate and demoralize, and thereby “attack,” the woman's male relatives who are unable to protect her.5

The effectiveness of rape as a strategy, or weapon, of war relies on the pervasive cultural norms that value women's sexual virtue. It is this perception of public ownership of women's sexuality that makes it possible to translate an attack against one woman into an attack against an entire community or ethnic group.6 The impact is multiplied when the woman becomes pregnant; the attack is then passed on to the next generation.

Enforced pregnancy is used as a form of ethnic cleansing, because the woman is forced to bear a child that has been “ethnically cleansed” by the blood of the rapist. In Rwanda after the 1994 genocide, it was estimated that as many as 5000 babies were born to women as a result of rape.7 These children became known as enfants mauvais souvenir, or children of bad memories. Many women have difficulty caring for these children, and there have been reports of abandonment and infanticide.6

Treatment of survivors of sexual violence

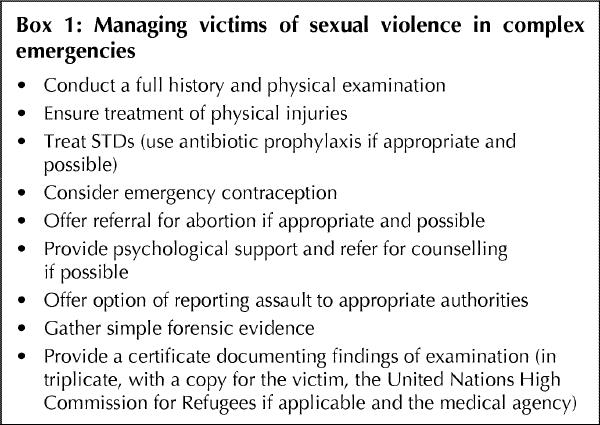

Medical personnel working in conflict settings must be trained to recognize victims of rape and to address both the immediate and long-term consequences. Clear protocols for responding to and documenting episodes of sexual violence are particularly important in emergency humanitarian interventions, since the issue may otherwise be lost if there are more immediately pressing issues such as ensuring clean water and providing access to basic health care.

A comprehensive protocol should attempt to address the medical, psychological and legal consequences of rape (Box 1). The first step is to obtain a full history and perform a physical examination. Some women are so badly injured that they will require referral for reconstructive surgery. Because of the high risk of STDs in most conflict settings, antibiotic prophylaxis should be prescribed when possible. In areas with high HIV prevalence rates, the option of prescribing antiretroviral prophylaxis is often not possible because of the high cost of the drugs and other related problems (e.g., lack of availability of antiretroviral drugs, lack of laboratory facilities for monitoring drug use, and sometimes government policy). Women who present early are offered emergency contraception. For those already pregnant and wishing termination, an abortion can sometimes be arranged depending on the laws of the country.

Box 1.

Rape survivors should be referred for mental health services where they exist. Women are often stigmatized by societal and cultural norms that view the victim as defiled. They may be rejected outright by their families and left destitute. Not surprisingly, many survivors end up debilitated by post-traumatic stress disorder.

Psychological interventions are complicated by the reality that rape in wartime usually happens against a backdrop of other traumas and losses. In this context, mental health programs for rape victims must be broad based and target a variety of traumas. In MSF's mental health programs, we have found that many patients never talk of sexual violence in an explicit way or publicly name their problem. Respecting a survivor's decision not to disclose an attack and protecting their anonymity while they receive treatment is an important aspect of the program.

Survivors who do wish to report the incident to the authorities must be supported in doing so. When indicated, and with the victim's consent, a forensic examination should be done and samples collected according to the local laboratory's capacity for forensic testing (often only a microscope is available and therefore testing is limited to a check for sperm; in other areas more extensive forensic testing can be done to identify the assailant[s]). However, even victims not wishing to pursue legal action should receive a certificate documenting the findings of the medical examination. This medical certificate becomes the legal validation of the woman's experience, to be used in the event of a refugee application or future legal proceedings. A copy should be kept by the relief agency so that an objective picture of the scale of sexual violence can be compiled.

Barriers to effective implementation of an intervention protocol

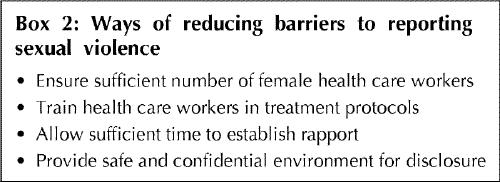

Many barriers exist to the proper implementation of a protocol for responding to and documenting episodes of sexual violence. An important one is the reluctance of victims to report the attack. Ways to reduce this barrier are highlighted in Box 2. One example is to employ sufficient numbers of female health care workers. Standard guidelines on working with refugee women suggest that at least 30% (ideally 50%) of health care workers should be women to ensure access to a same-sex health care worker for the medical examination.8 This strategy also recognizes that boys and men may also be victims of sexual violence and thus will have access to a male health worker if desirable.

Box 2.

Other ways to encourage reporting have been identified through mental health programs run by relief agencies. One of the most critical is the willingness of the health care provider to spend some extra time with the victim to establish a rapport. Extra time is, however, a rare commodity in a refugee camp, where patients may be lined up under the hot sun and health care workers often have to see between 80 and 100 people per day. In such settings, providing an atmosphere in which both the patient and the health care worker feel comfortable with the disclosure of such a sensitive topic is problematic.

Clearly, the need to respond proactively to sexual violence while trying to address basic emergency health priorities in a complex humanitarian mission is stressful for health care workers. The problem can also be compounded by a lack of resources and staff.

These constraints were vividly apparent in the Republic of the Congo in 1999. Fighting had erupted the year before, and up to 300 000 people fled south from the capital city of Brazzaville. Unfortunately, they were soon surrounded by fighting again. Along with the local residents, they found themselves trapped and completely cut off from external assistance. Eventually a main route out of the region was secured, and the population fled back toward the capital in several waves. This route would come to be dubbed the “corridor of death” by those travelling it.

A small number of international organizations were in Brazzaville as the internally displaced people returned. Up to 2000 people per day were screened, with large numbers found to be ill and malnourished. The reports of their return journey were horrific. Stories were told of young men suspected of being militiamen getting pulled from the lines of returning people and executed on the spot. Women and girls told of being brutally raped by soldiers, militiamen and even fellow returnees. In 12 months the general hospital in Brazzaville documented over 1300 reports of rape. The difficulty of adequately addressing sexual violence in such a context of overwhelming violence was painfully apparent in one doctor's lament when describing a typical incident at the hospital:

A large lorry suddenly stops in the hospital yard, with about twenty dust-covered people, mainly women, children and the elderly, surrounded by armed men. One man gets down: a machine gun burst had torn into his shoulder the day before, and his arm is hanging off. A young woman accompanied by little girls aged about 12 is next: emaciated and exhausted, she tells how they were repeatedly raped at a checkpoint after her husband was beaten and taken away after trying to intervene.

The doctor was fortunate in that a comprehensive service set up to address sexual violence was in place at his hospital. Yet as he rushed to triage the new arrivals, he found himself thinking, “Who can heal what these women have suffered?”

Advocacy as a tool

Addressing the problem of women's and children's vulnerability to sexual violence in complex emergencies often requires advocacy campaigns to alter circumstances in the field. In the case of the refugee camps in Zaire, MSF spoke out publicly to advocate for better security in the camps. This approach met with some success: the resulting public outcry led to the implementation of an internationally monitored security force in the camps.

At other times, public advocacy has done little to change the situation for women in the field. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire), Amnesty International recently reported that both sides of the conflict are using sexual violence “to spread terror among the populations, and to destabilize community identity.”9 There was little, if any, response from the international community. Similarly, in late 1999 MSF reported the atrocities they had documented in neighbouring Brazzaville,10 but there was little international reaction, and both sides of the conflict rejected responsibility for acts of violence against civilians.

Even when the likelihood of a significant response is limited, many physicians still feel it is their ethical duty to speak out publicly against abuses of human rights they have witnessed. This is based on an understanding both of individual medical ethics and of the principles of human rights and international humanitarian law.11 Victims of rape and violence may be too frightened to speak and are unlikely to be heard anyway. Those who advocate on their behalf do so because, like the MSF doctor in Brazzaville, they recognize the inadequacy of simply treating physical wounds without addressing the larger issues that allow the abuse to occur in the first place.

Beyond advocating for the prosecution of perpetrators of sexual violence, nongovernment organizations may also lobby for the involvement of political actors to help end the conflict. Yet, in some cases, this may not ensure an end to sexual violence. In places such as Bosnia that have found a fragile political peace, the sexual violence continues. The trauma that war and the breakdown of civil society produces, along with the culture of violence it promotes, means that many individuals have difficulty functioning in peacetime. As in wartime, women are finding themselves unwittingly on the frontline of this continuing violence. Women in MSF mental health programs have reported they now experience a significantly higher level of marital violence, including rape, than they did before the war. The focus of intervention programs must shift from war trauma to domestic violence. Unfortunately for these women, political settlements such as the Dayton Peace Agreement in Bosnia–Herzegovina, although successful at stopping the fighting, can do nothing to restore the private peace.

Progress in international law

The continuing challenge for medical humanitarian workers is to open the eyes of the world to these forgotten wars, and to insist that states conform to international standards of humanitarian law and human rights. Such efforts can lead to change. International reaction to the atrocities committed in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia has helped to trigger changes to international humanitarian law. The unique aspects of sexual violence that distinguish it from other forms of torture are now clearly recognized. The law also recognizes that rape is used systematically by regimes to achieve their goals of ethnic cleansing and genocide. Thanks to the testimony of many courageous women, the International Criminal Tribunals for Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia have successfully prosecuted cases of rape as a war crime and as an act of genocide.12,13

These cases represent a fraction of the women involved, but at least for some, justice can be said to have been served. For now, however, the legal framework permitting such prosecutions remains tenuous. A statute to create a permanent International Criminal Court with clear provisions for the prosecution of perpetrators of systematic sexual violence has been signed by 113 countries but ratified by only 21. Until such an international legal framework becomes more firmly established, ad-hoc advocacy efforts, both local and international, will remain crucial when trying to prevent sexual violence in the field.

Prevention of sexual violence

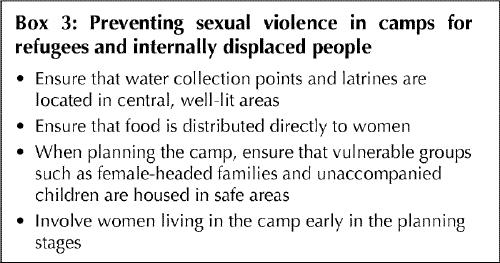

In the last decade, aid agencies have increasingly recognized that a response to sexual violence involves not just a treatment protocol but also preventive measures designed to decrease the risk for women (Box 3). The United Nations High Commission for Refugees instituted a program of gender awareness for its staff and, in 1995, published guidelines specifically addressing sexual violence and refugees.14 Simple measures in refugee camps such as locating water collection points and latrines in central areas with adequate lighting can make a significant difference. The importance of distributing food and other essential items directly to women is stressed. Camp planners are advised to consider vulnerable groups such as female-headed households and unaccompanied children to ensure that they are housed in safe areas of the camp. Most important, however, is the need to involve women living in the camp early in the planning stages of the camp, since they are best able to assess their risks and vulnerabilities and advise how they can be minimized.

Box 3.

Conclusion

Addressing sexual violence is challenging in any setting, yet it is doubly so in the context of war. Rape in wartime comes in many forms; in the extreme, systematic rape is a highly effective weapon used to terrorize communities and to achieve ethnic cleansing. Humanitarian organizations need to design protocols that take into account the medical, psychological and social impact of all types of sexual violence. Barriers to reporting should be addressed, and all cases should be adequately documented, both for the victim and as part of larger advocacy efforts. Advocacy should be pursued to improve compliance with international humanitarian law by local actors and to pressure the international community to respond appropriately to widespread or systematic violations. International law still needs strengthening in this regard, for example through the ratification of the statute creating the International Criminal Court.

However, commonplace episodes of everyday rape and sexual violence targeting vulnerable women and children in displaced populations will continue unabated unless the international community insists on minimum security guarantees for the vulnerable. The humanitarian community can help by implementing basic security measures when setting up refugee camps and by allowing women refugees to have input into their own protection. These interventions should be part of an integrated approach to emergency humanitarian interventions, to avoid the temptation of making this “silent emergency” a secondary priority.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Acknowledgements: We thank Kaz de Jong for supplying information and insight into the mental health programs of Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF). We also thank Dr. Joanne Liu for her helpful comments on the manuscript and for providing information on MSF's program in the Republic of the Congo.

Correspondence to: Dr. Leslie Shanks, Médecins Sans Frontières/ Doctors Without Borders — Canada, 402–720 Spadina Ave., Toronto ON M5S 2T9; vreekeed@hotmail.com

References

- 1.Toole M. Complex emergencies: refugee and other populations. In: Noji EK, editor. The public health consequences of disasters. 1st ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. p. 425.

- 2.Wiss S, Giller J. Rape as a crime of war. JAMA 1993;270:612-5. [PubMed]

- 3.Médecins Sans Frontières – Holland. Breaking the cycle. MSF call for action in the Rwandese refugee camps in Tanzania and Zaire. Amsterdam: MSF – Holland; 1994.

- 4.Human Rights Watch. Women's Rights Project. In: Human Rights Watch world report 1998. Available: www.hrw.org/worldreport/Back-04.htm#P643_128126 (accessed 2000 Sept 20).

- 5.Serrano-Fitamant D. Sexual violence in Kosovo. In: Grandits M, Wipler E, Baker K, Kokar E, editors. Rape is a war crime. How to support the survivors. Lessons from Bosnia — strategies for Kosovo. Conference report; Vienna; 18-20 June 1999. Vienna: International Centre for Migration Policy Development; 1999. p. 47-52. Available: www.icmpd.org/publications/k.htm (accessed 2000 Sept 20).

- 6.Human Rights Watch. Shattered lives: sexual violence during the Rwandan genocide and its aftermath. New York: Human Rights Watch; 1996.

- 7.United Nations High Commission for Refugees. Women in war-torn societies. In: The state of the world's refugees: a humanitarian agenda. Geneva: The Commission; 1997. Box 4.3. Available: www.unhcr.ch/refworld/pub/state/97/toc.htm (accessed 2000 Sept. 20).

- 8.International NGO Working Group on Refugee Women. Working with refugee women: a practical guide. Geneva: The Group; 1989.

- 9.Africa update: a summary of human rights concerns in sub-Saharan Africa. London (UK): Amnesty International; June 1999. Cat no 01/02/99.

- 10.Marschner A. A scientific approach to témoignage. In: O'Brien I, editor. Médecins Sans Frontières activity report July 1998-June 1999. MSF International; 1999. p. 18-9.

- 11.Bedell R, Coppens K, Lefkow L, Nolan H, Shanks L, Schull MJ. Humanitarian medicine, gender, and the law: utility, inadequacy and irrelevance. J Womens Health 1999-2000;1:109-24.

- 12.Prosecutor v. Jean Paul Akayesu (1996), Case no. ICTR-96-4-T (International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, Trial Chamber).

- 13.Prosecutor v. Furundzija (1995), Case no. IT-95-17/1 (International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, Trial Chamber).

- 14.United Nations High Commission for Refugees. Sexual violence against refugees: guidelines on prevention and response. Geneva: The Commission; 1995.