Abstract

We propose a hub-and-spoke model of Alzheimer’s disease, with endosomal recycling acting as the pathogenic hub from where the disease’s other pathologies fan out, thereby providing a role for the amyloid-precursor protein and reconciling a paradox caused by mounting questions over the ‘amyloid cascade’ hypothesis.

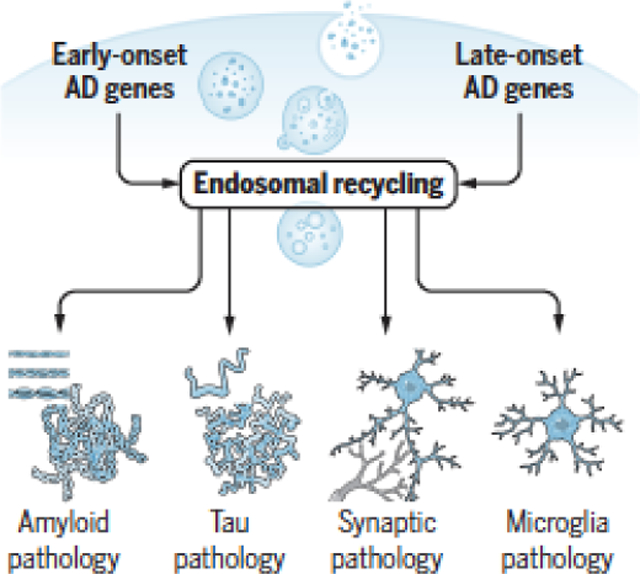

Graphical Abstract

The Alzheimer’s paradox

The hallmark histopathologies of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have remained essentially the same as those described by Alois Alzheimer over a century ago, except that we now have a deeper understanding into their molecular and cellular underpinnings. The extracellular plaques of ‘amyloid pathology’ chiefly comprise the Aβ peptide, a proteolytic fragment of the amyloid precursor protein (APP), which is primarily produced in neuronal endosomes from where it is secreted. The neurofibrillary tangles found inside neurons comprise the microtubule and actin binding protein tau. ‘Tau pathology’ begins in neurons, but is it is now known that tau can be actively secreted(1), spreading its pathological consequences(2). AD is a neurodegenerative disease, but years before the neurogenerative process causes actual neuronal cell death it is preceded by ‘synaptic pathology’, characterized by loss of dendritic spines. In contrast to these neuronal histopathologies, AD’s fourth pathology localizes to glia, which was also commented on by Dr. Alzheimer. Recent studies have shown that AD’s hallmark glial pathology appears to be primarily in microglia, and a characteristic of AD’s ‘microglial pathology’ is loss of its phagocytotic capabilities.

A hypothesis of the relationship of these four pathologies was proposed when genetic mutations linked to rare, autosomal-dominant, early-onset AD were identified at the tail end of the 20th century, and when subsequent investigations of these mutations showed that they belonged to the same biological pathway. The hypothesis was first formulated when mutations in APP itself were found. It then gained momentum when additional mutations were isolated, in genes that were ultimately called presenilin1 (PSEN1) and presenilin2 (PSEN2), because they were shown to encode proteins involved in APP’s enzymatic cleavage. Biochemically, all three mutations directly affect the proteolytic processing of APP, and all three were found to worsen amyloid pathology. Thus the ‘amyloid cascade hypothesis’ was born. As any good scientific hypothesis, it was anchored by two specific and testable assumptions. First, extracellular amyloid pathology-- the plaques observed by Alzheimer or the soluble cloud of amyloid fragments that surrounds them-- was stipulated to represent the upstream cause of the disease. Second, in a linear series of causal steps, extracellular amyloid pathology was proposed to secondarily trigger AD’s other three pathologies. In this way, extracellular amyloid was postulated to be the upstream cause of AD, setting into motion a domino effect of its other pathologies. While the mutations in APP or its cleaving enzyme are not found in the common, ‘sporadic’ and late-onset form of the disease, because both forms share the same four defining core features, the hypothesis was proposed to be generalizable to both.

The amyloid cascade hypothesis mobilized the pharmaceutical industry to develop a range of drugs, and to complete over 100 clinical trials, all targeting amyloid pathology. Unfortunately for patients, nearly all have failed. The minimal clinical efficacy has received the most attention in calling the amyloid cascade hypothesis into question. In truth, the complexity of clinical trials that rely on cognitive measures for a slowly progressing disease must be recognized, and there can always be post-hoc practical reasons for failed clinical endpoints. Since many of the most recent clinical trials tracked AD’s pathologies, in vivo or ex vivo, these trials can also function as ‘experimental medicine’ studies from which scientific conclusions can be inferred. More than showing little clinical benefit, perhaps the most telling finding from these studies is that despite clearing amyloid pathology, even in relatively early stages of the disease, the other pathologies have often been found to continue unabated(3, 4). Extracellular accumulation of amyloid pathology can at some level be cognitively detrimental and its reduction might confer some mild clinical benefits. Nevertheless, the conclusion that can be drawn from the trials is that extracellular amyloid pathology does not necessarily mediate the disease’s other pathologies on its road to dementia, as stipulated by the linear model.

With the prominence of the amyloid cascade hypothesis, there is now a backlash, not only against the hypothesis but against APP misprocessing in general. While this sociological dynamic is understandable, such a response can overswing. Unless it is assumed that AD’s autosomal-dominant and sporadic variants are mechanistically distinct, despite being near complete phenocopies, it would seem scientifically imprudent to throw out APP with the bathwater. APP and its fragments should be part of any unified AD hypothesis.

So, here’s the paradox: How can APP and its fragments be incorporated into a mechanistic hypothesis of AD, despite the growing number of studies that suggest that key assumptions of the amyloid cascade hypothesis seem wrong.

Reconciling the Paradox

The paradox can be reconciled when viewed through 21st century genomics, which have at long last mapped the genomic architecture of sporadic AD, and through other recent complimentary studies that have clarified AD’s cell biology and anatomical biology.

The more recent genetics has reliably linked approximately two-dozen genes to sporadic AD. The important conclusion from these studies is that genes linked to late-onset AD cohere around three biological pathways —endosomal trafficking, the innate immune response, and cholesterol metabolism. Each pathway contains multiple genes, but they are best typified by the genes within each pathway that have the strongest linkage to the disease: The retromer-trafficking receptor SORL1, the microglial phagocytic receptor TREM2, and the cholesterol-binding apolipoprotein APOE4. Among these three, recent studies suggest that only SORL1 is likely to be causal of AD, when in rare cases the mutated gene causes loss-of-function protein truncations(5). Both TREM2, whose own loss-of-function truncating mutations cause other diseases but not AD, and APOE4 only increase disease risk and do not by themselves cause AD.

These genetic observations suggest that the endosomal trafficking pathway, like the APP processing pathway, might be causal in AD. While the distinction between rare causal genes (originally APP, PSEN1, PSEN2, and now likely SORL1) and common genes that confer very high genetic risk (TREM2 and APOE4) can be debated, further support for the causal role of the endosomal trafficking pathway comes from AD’s cytopathology and by the pathophysiological consequences observed when proteins of each of the pathways are manipulated in model systems.

Just as plaques and tangles represent AD’s hallmark histopathology, it is now generally acknowledged that enlarged endosomes represents its hallmark cytopathology. The enlargement of endosomes in AD can be caused directly by dysfunction of the endosomal trafficking pathway. As clearly shown for SORL1, by reducing retromer-dependent recycling from endosomes, there is a jamming of trafficking out of endosomes, resulting in enlarged and dysfunctional endosomes(6). Importantly, this ‘traffic jam’ phenotype occurs independent of amyloid(6). Endosomal enlargement can also be caused by AD’s APP processing pathway, and AD’s cell biology explains how. APP is primarily cleaved when it is trafficked into endosomal membranes and APP’s fragments accumulate, therefore, inside endosomes where they are toxic, causing enlarged endosomes(7). Importantly, the traffic jam phenotype is caused by APP’s C-terminal fragments, not Aβ, and thus is also formally amyloid-independent (7). Thus, the endosomal trafficking and APP processing pathways converge on endosomal recycling dysfunction, and cause AD’s hallmark cytopathology independent of extracellular amyloid.

As to be expected of a causal pathway, manipulating retromer-dependent endosomal recycling in model systems can mediate all four of AD’s hallmark pathologies. Recycling regulates the endosomal outflow of APP back to the neuronal cell surface. By manipulating recycling function up or down, the pathway has been shown to mediate amyloid pathology(8, 9), first inside the neuron and then, via endosomal secretion, to the extracellular space. Recycling also regulates endosomal outflow of glutamate receptors at synapses(10), a transport route critical for plasticity and synaptic health. A loss of cell-surface glutamate receptors is characteristic of AD’s synaptic pathology, which can be recapitulated or rescued by manipulating recycling(8, 10). Endosomal recycling also delivers the mannose-6-phosphate receptor (M6PR) back to the trans-Golgi network (TGN), where the receptor is needed for trafficking proteases from the TGN to the lysosome via the endosome. It is now known that tau gains access to the endosomal compartment, from where it is trafficked to the lysosome for degradation(11). It is thus most likely in the endosome that tau’s pathological state might be regulated, supporting observations showing that manipulating endosomal recycling mediates tau pathology(8, 9, 12). Furthermore, it is via the unconventional endocytic pathway that tau is likely secreted(2), mediating its pathological trans-synaptic spread. Consistent with their role as risk factor pathways, manipulating AD’s immune response or cholesterol metabolism pathways can only modulate but not trigger the three AD pathologies that originate in neurons.

How about microglial pathology? For this pathology the immune response and cholesterol metabolism pathways can clearly act as causal drivers, both interacting at microglia, but interestingly so too can endosomal recycling. Many of the proteins of the recycling pathway are expressed in microglia, and many of the proteins in the immune response pathway, such as Trem2, are phagocytic receptors that are recycled from the endosome to the microglia cell surface. It is unsurprising therefore that by reducing cell-surface phagocytic receptors in microglia, manipulating the retromer-dependent recycling pathway recapitulates core features of AD’s microglial pathology(13).

Collectively, these studies show that endosomal recycling can directly mediate all four of AD’s pathologies, supporting the conclusion that this pathway plays a causal role in disease. Importantly, studies have shown that endosomal recycling can regulate tau pathology and synaptic pathology independent of amyloid(6, 9, 10), which appears true also for the microglia pathology(6, 13, 16). Rather than triggering a linear cascading series of events, therefore, endosomal recycling defects act more like a central hub from which each pathology fans out independent of the others (Figure). This conclusion can in part explain why, even when extracellular amyloid is cleared in sporadic patients in relatively early stages of disease, the other pathologies might progress unabated.

FIGURE. A proposed ‘hub & spoke’ model for Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis.

Causal genes in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease affect the intracellular processing of the amyloid-precursor protein, while putative causal genes in late-onset disease affect intracellular trafficking. Both classes of genes converge by causing defects in endosomal recycling, a pathogenic event that occurs independent of amyloid. Endosomal recycling defects cause enlarged endosomes, a ‘traffic jam’ phenotype that is a hallmark cytopathology of the disease. Endosomal recycling defects can, through parallel pathways, trigger all four of the disease’s histopathological hallmarks: extracellular and intracellular amyloid pathology, tau pathology, synaptic pathology, and microglia pathology. Like the spokes of a wheel, the downstream pathologies might interconnect, but according to the model they represent the disease’s smoke, not its fire.

AD’s anatomical biology provides additional support for the centrality of endosomal recycling in the pathogenesis of the disease. The entorhinal cortex, a region of the hippocampal formation, is differentially vulnerable to AD, and gene expression studies designed to explain this vulnerability have identified selective defects in retromer-dependent endosomal recycling as being a critical factor, and first implicated Sorl1 as being part of this pathway(14).

With these new findings it is now possible to propose a mechanistic model that might resolve the Alzheimer’s paradox. The model has two assumptions. First, instead of extracellular amyloid pathology, intracellular endosomal recycling dysfunction is proposed to act as a primary pathogenic event, which can secondarily lead to all of AD’s core features. Second, and perhaps most importantly, it proposes that all of AD’s core pathologies can occur in parallel from one central driver, giving rise to a hub-and-spoke model instead of a cascading series of events (Figure).

APP is incorporated into the model, because, as shown most clearly in early-onset AD, intracellular fragments produced by the APP processing pathway, either Aβ or more likely its C-terminal fragment, can act as a primary trigger of endosomal recycling defects (7). In addition, we acknowledge that extracellular amyloid, like any of AD’s other pathologies, can be detrimental, and that like the spokes of a wheel, the downstream pathologies might interconnect. Nevertheless, in the new model amyloid pathology and the other spoking out pathologies are the disease’s smoke, not its fire.

Testing the recycling model

While model systems are useful in clarifying the mechanisms of disease-associated pathways, the only way to test or refute a pathogenic model of human disease is with patients. Just as clinical trials were useful as experimental studies in challenging the cascading predictions of extracellular amyloid, so too can clinical trials test the fanning out predictions of recycling abnormalities.

Recent preclinical studies have provided proof-of-principle that recycling can be therapeutically targeted via ‘retromer enhancing’ agents. By increasing retromer levels, these interventions have been observed to normalize recycling defects, including Sorl1 and other proteins (15), thereby unjamming the endosome. In other model systems, retromer enhancers have already been shown to ameliorate AD’s core pathologies. They reduce amyloid pathology, reduce tau pathology(8, 9), ameliorate synaptic pathology(10, 16)-- and studies are beginning to show that they might even ameliorate microglia pathology(16). Retromer enhancers that normalize recycling defects, by pharmacological chaperones or by gene therapy, have already successfully moved through the efficacy stages of preclinical drug development. While, to date, these interventions are safe in flies and mice, toxicology screens in non-human primates remain as the final issue before moving to clinical trials.

Validated biomarkers are required in experimental medicine to meet the highest standard of experimental rigor. Whether by biofluids or neuroimaging, validated biomarkers already exist for amyloid, tau, and synaptic pathology, and biomarkers of microglial pathology are currently in development. Currently lacking are biomarkers of AD’s recycling pathway, which would be required for patient enrollment and for tracking target engagement.

Summary

Grounded in AD’s molecular biology, cell biology, and anatomical biology, the proposed recycling model reconciles the APP paradox, and forms a plausible updated hypothesis for explaining AD pathogenesis. Nevertheless, just like for the amyloid cascading hypothesis, only when recycling interventions and biomarkers become available can the ultimate veracity of the model be confirmed or refuted.

Limited Citations

- 1.Sato C et al. , Tau Kinetics in Neurons and the Human Central Nervous System. Neuron 98, 861–864 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katsinelos T et al. , Unconventional Secretion Mediates the Trans-cellular Spreading of Tau. Cell Rep 23, 2039–2055 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egan MF et al. , Randomized Trial of Verubecestat for Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med 380, 1408–1420 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicoll JAR et al. , Persistent neuropathological effects 14 years following amyloid-beta immunization in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 142, 2113–2126 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holstege H et al. , Characterization of pathogenic SORL1 genetic variants for association with Alzheimer’s disease: a clinical interpretation strategy. Eur J Hum Genet 25, 973–981 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knupp A et al. , Depletion of the AD Risk Gene SORL1 Selectively Impairs Neuronal Endosomal Traffic Independent of Amyloidogenic APP Processing. Cell Rep 31, 107719 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwart D et al. , A Large Panel of Isogenic APP and PSEN1 Mutant Human iPSC Neurons Reveals Shared Endosomal Abnormalities Mediated by APP beta-CTFs, Not Abeta. Neuron, 104, 256–270 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li JG, Chiu J, Pratico D, Full recovery of the Alzheimer’s disease phenotype by gain of function of vacuolar protein sorting 35. Mol Psychiatry, 10.1038/s41380-019-0364-x (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 9.Young JE et al. , Stabilizing the Retromer Complex in a Human Stem Cell Model of Alzheimer’s Disease Reduces TAU Phosphorylation Independently of Amyloid Precursor Protein. Stem Cell Reports 10, 1046–1058 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Temkin P et al. , The Retromer Supports AMPA Receptor Trafficking During LTP. Neuron 94, 74–82 e75 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaz-Silva J et al. , Endolysosomal degradation of Tau and its role in glucocorticoid-driven hippocampal malfunction. EMBO J 37, e99084 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vagnozzi AN et al. , VPS35 regulates tau phosphorylation and neuropathology in tauopathy. Mol Psychiatry, 10.1038/s41380-019-0453-x (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.Yin J et al. , Vps35-dependent recycling of Trem2 regulates microglial function. Traffic, 17, 1286–1296 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Small SA, Retromer sorting: a pathogenic pathway in late-onset Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 65, 323–328 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mecozzi VJ et al. , Pharmacological chaperones stabilize retromer to limit APP processing. Nat Chem Biol, 10, 443–449 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qureshi YH et al. , Retromer repletion with AAV9-VPS35 restored endosomal function in the mouse hippocampus. bioRxiv, 618496 (2019). [Google Scholar]