Abstract

Background

Pregnancy can be a stressful time for many women; however, it is unclear if higher stress and depressive symptoms are associated with poorer diet quality during pregnancy.

Objective

The aims for this narrative review were to (1) synthesize findings of original, peer-reviewed studies that examined associations of stress and/or depressive symptoms with diet quality during pregnancy; (2) review the measurement tools used to assess stress, depressive symptoms, and diet quality; (3) identify current gaps in the extant literature; and (4) offer recommendations for future research.

Methods

A search strategy was used to identify peer-reviewed manuscripts published between January 1997 and October 2018, using the following databases: PubMed, CINAHL Complete, PsycINFO, Academic Search Complete, and Psychology & Behavioral Sciences Collection. The search was updated December 2019. Two reviewers independently assessed title, abstract, and full-text of the studies that met the inclusion criteria. Data were extracted and a quality assessment was conducted.

Results

Twenty-seven observational studies were identified in this review (21 cross-sectional and 6 longitudinal). In 22 studies, higher stress and/or depressive symptoms were associated with poorer diet quality or unhealthy dietary patterns; 5 studies found no association. Findings are mixed and inconclusive regarding the relationship among stress, depressive symptoms, and food groups related to diet quality and frequency of fast-food consumption.

Conclusions

The current data suggest stress and depressive symptoms may be a barrier to proper diet quality during pregnancy; however, variability in the assessment tools, timing of assessments, and use of covariates likely contribute to the inconsistency in study findings. Gaps in the literature include limited use of longitudinal study designs, limited use of comprehensive diet-quality indices, underrepresentation of minority women, and lack of multilevel theoretical frameworks. Studies should address these factors to better assess associations of stress and/or depressive symptoms with diet quality during pregnancy.

Keywords: stress, depression; diet quality; pregnancy; review

INTRODUCTION

Almost one-half (46%) of pregnant women in the United States (US) exceed the Institute of Medicine’s 2009 gestational weight gain (GWG) recommendations,1,2 and this has become a significant public health challenge. Excessive GWG is associated with adverse maternal outcomes (eg, increased risk of preeclampsia and cesarean delivery)3 and poor infant health. Maternal diet quality, or overall eating pattern during pregnancy influences infant development and can help prevent excessive GWG, making it an important modifiable factor to address during pregnancy.4,5

Depression is the primary cause of disease-related disability among women worldwide, with the prevalence of depression reaching its peak during the childbearing years.6 Depression during pregnancy has been associated with excessive GWG7 and suicidal ideation,8 among other adverse health outcomes, highlighting the importance of screening for depressive symptoms during pregnancy to intervene.9 Stress, defined as generalized perceived stress,10 is inextricably linked with depression by increasing one’s risk for depression,11 and depression, in turn, also increases one’s susceptibility to stressful events,12 creating a feedback loop for chronic stress.12 Measuring perceived stress is beneficial because it captures one’s experience of stress independent of the source of stress, compared to stressful life events scales.10

Stress has been associated with consuming energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods (eg, less fruit and vegetable intake13; more fast-food intake14; more intake of sweets and snacks) among pregnant women.15 Stress is thought to disrupt the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis system, which elevates cortisol levels, encouraging increased consumption of energy-dense foods,16,17 which may negatively affect diet quality. Depressive symptoms are important to investigate in the context of dietary intake because depressive symptoms may exacerbate the negative effect of maternal stress on diet quality.18

Proper diet quality involves consuming foods from a variety of different food groups, such as those that compose diet-quality indices (eg, fruits, vegetables, grains).19 Dairy is the primary source of dietary calcium in the US,20 making it an important component of overall diet quality.19 Emerging research is now examining the relationship between the consumption of fermented foods (eg, yogurt, cheese, fermented milk) and mental health during pregnancy,21 with conflicting results to date. In addition, soy product consumption has been gaining attention because of the multiple health benefits of isoflavones (eg, prevention of hormone-dependent cancers and cardiovascular diseases)22; however, the mental health benefits of soy consumption in pregnancy have not received much attention.23 Furthermore, epidemiologic data indicate consuming more fish is associated with a lower occurrence of depressive symptoms among the general population24–26; however, these associations have not been thoroughly examined during pregnancy. Fast-food consumption is also important to examine because it is associated with excess energy intake and eating behaviors related to poor diet quality (eg, higher sodium and added-sugar intake).27

Previous reviews that have explored the relationship between stress and/or depressive symptoms and diet quality during pregnancy have been limited in 3 main ways: (1) having a predominant focus on the impact of nutrient deficiencies (eg, zinc, iron, omega-3 fatty acids)28,29; (2) compiling studies that examined outcomes during the entire perinatal period (including pregnancy and up to 1-year postpartum)29–31; and (3) focusing on how diet quality affects child health and dietary outcomes (eg, height; blood pressure; fruit and vegetable intake).32–35 These previous approaches leave important gaps in the literature as it pertains to maternal physical and mental health during pregnancy. Limited research has examined associations of maternal mental health factors (ie, stress, depressive symptoms) with overall diet quality in pregnancy exclusively.15

The aims for conducting this narrative literature review were to: (1) synthesize findings of original, peer-reviewed studies that examined associations of stress and/or depressive symptoms with diet quality during pregnancy; (2) review the measurement tools used to assess stress, depressive symptoms, and diet quality; (3) identify gaps in the extant literature; and (4) offer recommendations for future research.

METHODS

This narrative review was conducted using a systematic literature search strategy. In October 2018, the following databases were searched: PubMed, CINAHL Complete, PsycINFO, Academic Search Complete, and Psychology & Behavioral Sciences Collection. The search was updated in December 2019. Free text and controlled vocabulary were developed in conjunction with a librarian who validated the search strategy for all databases. The following filters were used: English articles and articles published since January 1, 1997. This date was chosen because Kant’s 1996 review36 acknowledged that it was common to examine individual nutrients or foods with health outcomes at that time, an approach that had many limitations. Kant’s review helped signify a more widespread shift in assessing diet quality comprehensively. In addition, a search yielded no relevant articles before 1997. The PubMed search strategy is detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

PubMed search strategy for the narrative review investigating associations of stress and/or depressive symptoms with diet quality in pregnancy

| Concept | Search terms |

|---|---|

| Concept 1: Stress |

|

| Concept 2: Depression |

|

| Concept 3: Diet quality |

|

| Concept 4: Pregnancy |

|

Abbreviations:MESH, medical subject headings; tw, text word.

English-language articles published between January 1997 and December 2019.

Truncated term.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined a priori. Studies were included if they: (1) were full-text articles; (2) were of cohort, cross-sectional, or randomized design; and (3) examined associations of stress and/or depressive symptoms with diet quality in pregnancy. Stress was defined as self-reported perceived stress or stressful life events.10,37 Depressive symptoms were self-reported or assessed by diagnostic measurement tools.38,39 Diet quality was defined as the quality of one’s typical food intake determined by a diet quality score,18 alignment with healthy eating guidelines,40 adherence to a specific dietary pattern (eg, “Western” diet),41 or intake of food groups related to diet quality.15 Diet quality was the main outcome of interest; however, cross-sectional studies were included if they examined diet quality as the exposure or the outcome, because the direction of the relationship is unclear. Cohort studies were included if they examined diet quality as the outcome.

Studies were excluded if they only: (1) examined individual nutrients or micronutrients (eg, omega-6 fatty acids); (2) examined disordered eating or gestational diabetes; (3) measured associations in prepregnancy or postpartum; (4) assessed diet in relation to malnutrition or food insecurity; (5) used animal models; (6) used qualitative methods; (7) focused on child outcomes; (8) were pilot studies (sample size < 20 women); (9) were review articles; (10) measured stress biomarkers; or (11) were dissertations or unpublished works.

Selection process

All records were uploaded into Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia); duplicates were automatically removed. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts to identify studies that met the inclusion criteria. A calibration exercise, which involved screening 50 titles and abstracts, was conducted to clarify the eligibility criteria. After agreement was achieved, reviewers identified relevant articles and a full-text screening was conducted by 2 reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The lead reviewer extracted data from included studies and a second reviewer independently checked the extraction to ensure accuracy. The extracted data included study characteristics (sample size, study design, study location, participants’ racial composition, and inclusion of a theoretical framework); diet quality assessment (measures used, time of completion, and method for assessing diet quality); stress and depressive symptoms assessment (measures used, time of completion, and cutoff scores); statistical analyses; covariates; and a summary of relevant findings. If information needed to be added, reviewers had a discussion and came to an agreement. The same 2 reviewers independently assessed the quality of the studies using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation 4 guidelines, which evaluate observational studies against 4 criteria: developing and including eligibility criteria, unflawed measurement of exposure and outcome, controlling for confounding, and incomplete follow-up.42

RESULTS

Study selection

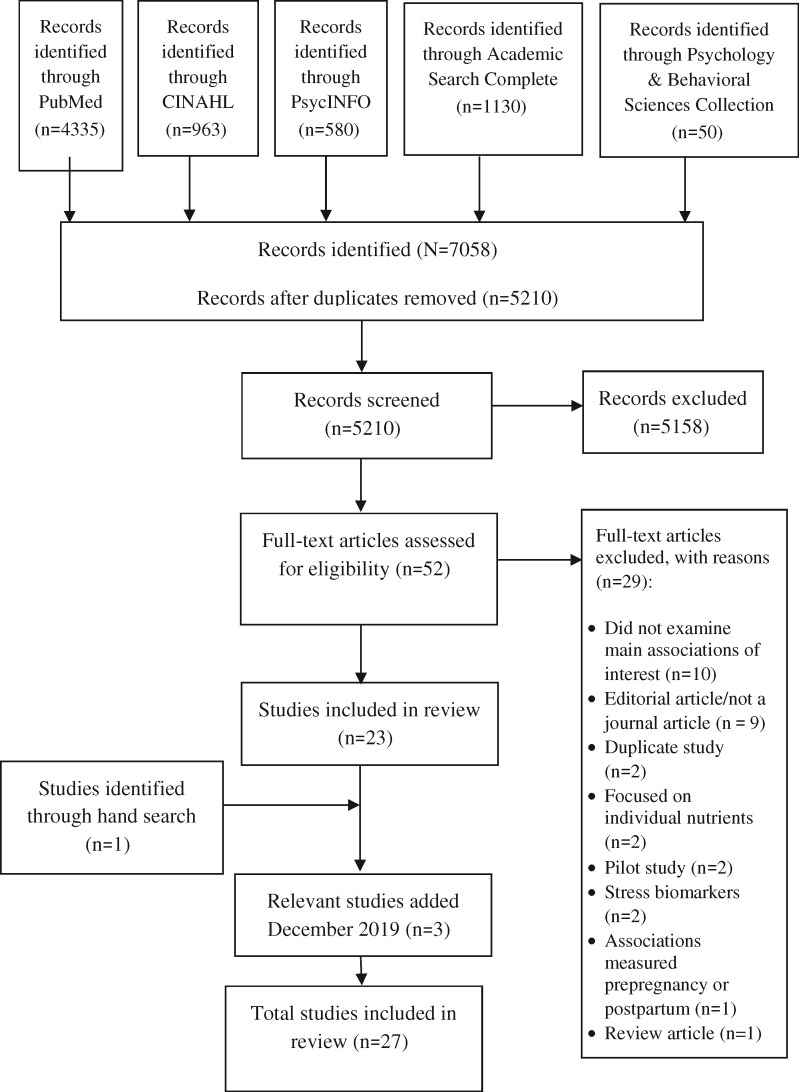

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart provides an overview of the search process (Figure 1). The initial search occurred in October 2018. Out of 7058 identified records, Covidence removed 1848 duplicates, resulting in 5210 records that were screened by title and then by abstract. From these, 5158 records were excluded because they were irrelevant to the topic (eg, animal models, examined individual nutrients, examined child outcomes, examined associations either prepregnancy or postpartum, focused on eating disorders). The full-text for the resulting 52 studies were read and an additional 29 articles were excluded. Reasons for exclusion are detailed in Figure 1. There were 23 articles that met the inclusion criteria and their reference lists were reviewed for additional relevant articles. One article was identified from reference lists. The search was updated in December 2019 to check for new relevant articles and 3 were added, for a total of 27 articles.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart for article selection process for narrative review assessing stress and/or depressive symptoms with diet quality in pregnancy.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of included studies are reported in Table 2. All studies were observational and used a survey methodology. There were 21 cross-sectional studies13–15,18,21,23,40,43–56 and 6 prospective cohort studies.41,57–61

Table 2.

Summary of 27 studies evaluating associations of stress and/or depressive symptoms with diet quality during pregnancy

| First author (year) | Country | Study design | Sample size, racial composition | IV, assessment tool(s) | DV, assessment tool(s) | Week of pregnancy | Statistical tests, covariates | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary patterns (nonindices) | ||||||||

| Barker (2013)45 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional |

|

|

|

32 |

|

Adjusted: Higher depressive symptoms were associated with higher “unhealthy” dietary pattern scores (d = 0.096; P < 0.05) and lower “healthy” dietary pattern scores (d = −0.059; P < 0.05) |

| Baskin (2017)59 | Australia | Cohort study |

|

|

|

T1: 16 T2: 32 |

|

|

| Jiang (2018)61 | China | Cohort study, cross-sectional analysis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lobel (2008)57 | United States | Cohort study |

|

|

|

|

|

Adjusted: Higher pregnancy-specific stress scores were associated with higher “unhealthy” dietary pattern scores (β = 0.29; P < 0.05), and associated with lower “healthy” dietary pattern scores (β = −.14; P < 0.05) |

| Miyake (2018)46 | Japan | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

5−39 wk |

|

|

| Molyneaux (2016)41 | United Kingdom | Cohort study |

|

|

|

|

|

Adjusted: High depressive symptoms at 18 and 32 wk were significantly associated with higher confectionary dietary pattern scores only (β = 0.10; 95%CI, 0.02–0.17; P =0.01) |

| Omidvar (2018)53 | Iran | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

Anytime in pregnancy (range, < 13 to 42 wk) |

|

Adjusted: Neither depressive symptoms nor pregnancy-specific stress were significantly associated with healthy nutrition scores in adjusted models (P > 0.05) |

| Paskulin (2017)47 | Brazil | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

16–36 wk |

|

|

| Pina-Camacho (2015)60 | United Kingdom | Prospective cohort study |

|

|

|

Depressive symptoms: 18 wk, 32 wkDiet: 32 wk |

|

Correlation: Higher depressive symptoms at 18 wk were associated with higher unhealthy dietary pattern scores at 32 wk (r = 0.024; P < 0.05) |

| Wall (2016)48 | New Zealand | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

29−40 wk |

|

Adjusted: Higher “junk” dietary pattern scores were associated with having an EPDS score > 13 (β = 0.14; 95%CI, 0.06–0.23; P = 0.001). |

| Diet quality (indices) | ||||||||

| Berube (2019)54 | United States | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

28−32 wk |

|

Depressive symptoms were not associated with diet quality |

| Fowles (2011)18 | United States | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

<14 wk |

|

Adjusted: Higher distress scores were significantly associated with higher poor eating habits scores (β = 0.36; P < 0.01), and directly (β = −0.23; P < 0.05) and indirectly associated with lower diet-quality index scores (β = −0.30; P < 0.05) |

| Fowles (2012)43 | United States | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

<14 wk |

|

Unadjusted: Women with diet quality scores below the median (DQI-P score, 53.3) had higher depressive symptoms (mean ± standard deviation, 9.6 ± 5.1 vs 6.7 ± 5.1; P = 0.02) and stress scores (22.1 ± 5.4 vs 19.3 ± 4.8; P = 0.03) than women with diet-quality scores above the median |

| Saeed (2016)58 | Pakistan | Cohort study |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Food groups | ||||||||

| Chang (2015)13 | United States | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

Any time during pregnancy (women in all 3 trimesters) |

|

|

| Chang (2016)52 | United States | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

Any time during pregnancy (women in all 3 trimesters) |

|

Unadjusted: Among overweight women, those who reported more depressive symptoms were more likely to eat fast foods, which led to more vegetable intake (P = 0.01) and partially higher fat intake than women with fewer depressive symptoms (P = 0.003) |

| Chang (2019)55 | United States | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

Any time during pregnancy (women in all 3 trimesters) |

|

Adjusted: There was no relationship between stress and fat intake. Women with high stress reported significantly lower fruit and vegetable intake but not fat intake than women with low stress |

| Fowles (2011)14 | United States | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

< 14 wk |

|

Unadjusted: Eating from fast-food restaurants ≥3 times in the past week was associated with having higher stress (mean ± standard deviation, 23.7 ± 6.8 vs 18.9 ± 4.1; 95%CI, −7.87 to −1.70; P < 0.05) and depressive symptoms (10.4 ± 6.0 vs 6.8 ± 4.1; 95%CI, −6.45 to −0.71; P < 0.05) compared with eating at fast-food restaurants 0−2 times in the past week |

| Golding (2009)49 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

32 wk |

|

Adjusted: Compared with women consuming > 1.5 g of omega-3 from seafood/wk, those consuming none were more likely to have higher depressive symptoms at 32 wk' gestation (adjusted OR, 1.54; 95%CI (1.25, −1.89); P < 0.001) |

| Hurley (2005)15 | United States | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Malek (2017)40 | Australia |

|

|

|

|

13−30 wk |

|

Adjusted: Perceived stress was not a significant predictor of adherence to food group recommendations (β = 0.04, P > 0.05) |

| Miyake (2013)50 | Japan | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

|

|

Adjusted: Compared with being in the lowest quartile, being in the highest quartile for fish intake was associated with a lower prevalence of depressive symptoms during pregnancy (adjusted OR between extreme quartiles, 0.61; 95%CI, (0.42–0.87); P = 0.01) |

| Miyake (2015)51 | Japan | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Miyake (2018)23 | Japan | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sontrop (2008)44 | Canada | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

10−22 wk |

|

Adjusted: No relationship between fish intake and depressive symptoms after controlling for confounders (β = −0.2; 95%CI, −0.9 to 0.4; P > 0.05) |

| Takahashi (2016)21 | Japan | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

13−40 wk |

|

Adjusted: The consumption of yogurt and other fermented foods was not associated with lower prevalence of psychological distress in pregnant women (P > 0.05) |

| Takei (2019)56 | Japan | Cross-sectional study |

|

|

|

19−23 wk |

|

There was no association between depressive symptoms and vegetable intake |

Abbreviations: AA, African American; ALSPAC, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children; BMI, body mass index; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale; DQI-P, Diet Quality Index for Pregnancy; DV, dependent variable; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; HEI, Healthy Eating Index; IV, independent variable; KOMCHS, Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study; OR, odds ratio; PR, prevalence ratio; PRIME-MD, Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders; RR, relative risk; SDS, Self-Rating Depression Scale; WIC, Women, Infants, & Children.

Setting.

The studies were conducted in multiple countries. Nine studies were conducted in the US13–15,18,43,52,54,55,57, 6 studies were conducted in Japan,21,23,46,50,51,56 4 studies were conducted in the United Kingdom,41,45,49,60 2 took place in Australia,40,59 and 1 study was conducted in each of the following countries: Brazil,47 New Zealand,48 Pakistan,58 Canada,44 China,61 and Iran.53

Population.

Sample sizes ranged from 8258 to 13 31441 women in cohort studies and from 5014 to 14 54149 in cross-sectional studies. Eight cross-sectional studies included targeted populations: low-income women13,14,18,43,52,54,55; women with a prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) of overweight or obese 13,52,55; and well-educated, middle-class women.15 One cohort study included a targeted population of middle-income women.58

Dietary assessment.

Dietary intake was assessed through a variety of tools. Dietary intake was most commonly assessed through food frequency questionnaires (FFQs), which were used in 12 studies.15,21,40,41,44,45,47–49,54,59,60 FFQs estimate one’s usual intake, typically over the previous month.62 The level of detail of FFQs varied among these studies: One study used a 3-item version,49 1 study used a 4-item version,44 1 study used a 6-item version,40 and the remaining studies used detailed FFQs, ranging from 4341 to 118 items.54 Three studies used 24-hour dietary recalls14,18,43; 1 study used a 21-item dietary recall questionnaire61; 5 studies used diet history questionnaires23,46,50,51,56; 3 studies used a rapid food screener13,52,55; 1 study used a prenatal health behaviors scale57; 1 study used a combination of 24-hour dietary recalls and a food frequency checklist modified to fit the cultural context of Pakistan58; and 1 study used a health-promoting lifestyle profile (Persian version).53

Comprehensive diet quality index scores were estimated in 4 studies18,43,54,58 and were derived from 24-hour dietary recalls or a detailed FFQ. The Diet Quality Index for Pregnancy was used in 2 studies18,43 and consisted of 8 components: grains; fruit; vegetables; percentage of recommended intake for folate, calcium, and iron; percentage of energy from fat; and meal/snack pattern.63 Scores for each component ranged from 0 to 10, with total scores ranging from 0 to 80. A composite score ≥ 70 indicated the most desirable diet quality.63 The third study modified the traditional Healthy Eating Index (HEI) to assess only the adequacy components (ie, areas where typical consumption is too low) such as whole grains, whole fruit, and total vegetables.58 The overall score of the modified HEI was reduced to 50, with a score > 40 indicating good diet quality. The fourth study used the traditional HEI-2015, with scores ranging from 0 to 100.

Eight studies identified dietary patterns through factor analysis,45,46,59,60 other statistical techniques,41,47,48 or “healthy” or “unhealthy” subscales.57 Standardized scores for each dietary pattern were calculated for study participants, with higher scores indicating greater similarity to that dietary pattern.41 Some of the identified patterns include “healthy” vs “unhealthy”45,59; “Japanese”46; “health conscious”41,48; “common Brazilian”47; “junk”/“processed”/“confectionary”/“Western”41,46,48; and “vegetarian.”41 One study assessed diet quality by examining dietary diversity across 9 food groups and creating a composite score, with higher scores indicating greater dietary diversity and better diet quality.61 In addition, 9 studies assessed food groups (eg, fruit, vegetables, fish, dairy)13,15,40,44,49–51,55,56 and 1 assessed fast-food intake.14

Mental health assessment.

Mental health was assessed through multiple tools. A total of 23 studies assessed depressive symptoms during pregnancy.13–15,18,23,41,43–54,56,58–61 Of these, 13 studies used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS),13,14,18,41,43,45,48,49,52,56,58–60 a validated self-report screening tool used in clinical and research settings to identify depressive symptoms during pregnancy and postpartum.38 Scores from this scale can be used as a continuous variable, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms or categorized into levels of depressive symptoms using validated cutoff scores.38 Of these, 5 studies analyzed depressive symptoms as a continuous variable45,52,56,59,60 and 8 studies used cutoff scores ranging from ≥ 9 to ≥ 13 to identify high levels of depressive symptoms.13,14,18,41,43,48,49,58 Five studies used the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale to assess depressive symptoms,23,44,46,50,51 which is a research screening tool to identify high depressive symptoms and has been validated in community samples.64 Of these 5, 1 study used a cutoff score of > 1646 and 4 studies used a cutoff of ≥ 1623,44,50,51 to identify depressive symptoms. One study used the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders,47 a valid tool designed to facilitate the diagnosis of major depressive disorder by primary care physicians.39 One study used the Profile of Mood States–Depression subscale,15 a continuous measure that assesses depressed mood, with higher scores reflecting more-negative mood65; another study used the Self-Rating Depression Scale,61 a previously validated screening tool used to evaluate one’s mood in the past 7 days, with higher scores indicating higher depressive symptoms (score range, 20–80; cutoff, ≥ 53)66; and 1 study used the Beck Depression Inventory–II,53 which is a widely used and valid instrument for detecting depression in normal and clinical populations. Higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms.67 Last, 1 study used the Patient Health Questionnaire–9, a validated tool that includes 9 items related to depression; higher scores indicate higher depressive symptoms.68

Eleven studies assessed self-reported stress or psychological distress during pregnancy.13–15,18,21,40,43,52,53,55,57 Three studies used the Prenatal Psychosocial Profile–Stress subscale,14,18,43 a validated continuous measure of stress during pregnancy.69 Two studies used the full-length (14-item) Perceived Stress Scale,15,55 2 studies used the 9-item version,13,52 and 1 study used the brief 4-item version,40 with all versions measuring general perceived stress.10 Two studies assessed pregnancy-specific stress; 1 used the original Prenatal Distress Questionnaire, and 1 used a revised version.57 The Prenatal Distress Questionnaire is a continuous measure of pregnancy-specific stress.70 One study examined stressful life events in conjunction with prenatal distress by using the Prenatal Life Events Scale, which is a count of stressful life events during pregnancy and resulting level of distress.37 Last, 1 study used the 6-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale,21 which is a widely used screening tool for identifying psychological distress in the general population.71 On all stress measures, higher scores indicated higher levels of stress or distress.

Methodological quality.

The results of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation 4 quality assessment are summarized in Table 3.42 Ten studies provided adequate and appropriate information regarding eligibility criteria, including exclusion for health conditions that could affect diet quality.14,15,18,43,44,53,54,56,58,61 Most of the studies provided unflawed measurement of exposure and outcome.14,15,18,21,23,40,41,43–51,54–56,58–61 Only 5 studies failed to adequately control for potential confounding factors or did not specify their control variables,13,14,43,52,56 and only 6 studies had complete follow-up or results for multiple points during pregnancy.41,57–61 Two studies had the strongest methodological design42 relative to the other included studies. These studies found significant associations of mental health with diet quality in pregnancy.58,61 There was variation in the covariates included across studies. Sociodemographic factors such as age, education, income, and marital status were controlled for in nearly half of the studies.15,18,21,23,40,41,46,47,49,53–55,59,61 Parity was controlled for in 9 studies,15,21,23,40,41,49,54,59,61 gestational age (weeks) was controlled for in 7 studies,21,23,46,50,51,53,55 history of depression was controlled for in 6 studies,21,23,46,50,51,59 and BMI was controlled for in 11 studies.15,21,23,40,46,48,50,51,54,59,61

Table 3.

Risk-of-bias summarya

| First author (year) | Appropriate eligibility criteria | Appropriate measurement of exposure and outcome | Adequately controlled confounding | Complete follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barker (2013)45 | — | + | + | — |

| Baskin (2017)59 | — | + | + | + |

| Berube (2019)54 | + | + | + | — |

| Chang (2015)13 | — | — | c | — |

| Chang (2016)52 | — | — | c | — |

| Chang (2019)55 | — | + | + | — |

| Fowles (2011)18 | + | + | + | — |

| Fowles (2011)14 | + | + | — | — |

| Fowles (2012)43 | + | + | — | — |

| Golding (2009)49 | — | + | + | — |

| Hurley (2005)15 | + | + | + | — |

| Jiang (2018)61 | + | + | + | + |

| Lobel (2008)57 | — | — | + | + |

| Malek (2017)40 | — | + | + | — |

| Miyake (2013)50 | — | + | + | — |

| Miyake (2015)51 | — | + | + | — |

| Miyake (2018)46 | — | + | + | — |

| Miyake (2018)23 | — | + | + | — |

| Molyneaux (2016)41 | — | + | + | + |

| Omidvar (2018)53 | + | — | + | — |

| Paskulin (2017)47 | — | + | + | — |

| Pina-Camacho (2015)60 | — | + | + | + |

| Saeed (2016)58 | + | + | + | + |

| Sontrop (2008)44 | + | + | + | — |

| Takahashi (2016)21 | — | + | + | — |

| Takei (2019)56 | + | + | ? | — |

| Wall (2016)48 | — | + | + | — |

Abbreviations: —, high risk of bias (criteria not met in the study design); +, low risk of bias (criteria met in the study design).

Authors’ judgments about each risk-of-bias item were reviewed for each included study according to Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation–4 guidelines.

Unclear risk of bias; authors did not report whether criteria were met.

Study findings (Table 2) were grouped into 3 categories on the basis of the way diet quality was assessed: (1) dietary patterns, such as healthy or Western patterns, (2) diet quality determined from standardized diet quality indices (eg, Diet Quality Index for Pregnancy, HEI), and (3) dietary diversity, consumption of fast food, or specific food groups commonly included in diet quality indices (eg, fruit, vegetable, seafood).

Stress and depressive symptoms: studies assessing dietary patterns (nonindices).

Cohort

There are mixed findings regarding the relationship between depressive symptoms in early pregnancy (ie, 16 or 18 weeks) and dietary pattern scores at 32 weeks (eg, “unhealthy,” “confectionary,” “health conscious”).41,59,60 For example, Baskin et al59 found that higher depressive symptoms at 16 weeks significantly predicted lower “unhealthy” dietary pattern scores at 32 weeks (β = −0.17; 95%CI, −0.32 to −0.02; P < 0.05).59 Molyneaux et al41 found that consistently elevated depressive symptoms were significantly associated with higher “confectionary” dietary pattern scores [β = 0.10; 95%CI, 0.02–0.17); however, they found no relationship between elevated depressive symptoms and 4 other dietary patterns (ie, health conscious, traditional, processed, or vegetarian). Stress, specifically pregnancy-specific stress, was assessed in only 1 cohort study.57 Lobel et al57 found that higher pregnancy-specific stress was significantly associated with higher unhealthy dietary pattern scores (β = 0.29; P < 0.05) and lower healthy dietary pattern scores (β = −0.14; P < 0.05) in a majority white sample of US women (n = 279).

Cross-sectional

Two cross-sectional studies examined stress and/or depressive symptoms as the exposure and dietary patterns as the outcome.45,53 The authors reported mixed findings. For example, Barker et al45 found that higher depressive symptoms were associated with higher unhealthy dietary pattern scores (β = −0.01; 95%CI, −0.015 to −0.006) and lower healthy dietary pattern scores [β = −0.005; 95%CI, −0.009 to −0.003) at 32 weeks. Alternatively, Omidvar et al53 found that neither depressive symptoms nor pregnancy-specific stress were significantly associated with healthy nutrition scores.

Four cross-sectional studies examined dietary patterns or dietary diversity as the exposure and level of depressive symptoms46,48,61 or diagnosis of major depressive disorder as the outcome.47 Overall, findings indicated an inverse relationship between dietary pattern and depressive symptoms or major depressive disorder. For example, Miyake et al46 found that Japanese women (n = 1744) who scored in the upper quartiles of the healthy dietary pattern (second, third, or fourth quartiles) had a lower prevalence of depressive symptoms, indicated by Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale scores > 16 (adjusted prevalence ratio, 0.56; 95%CI, 0.43–0.73), compared with those in the lower quartile. In terms of diagnosed depression, Paskulin et al47 found that Brazilian women with high “common Brazilian” dietary pattern scores had a 43% higher prevalence of major depressive disorder compared with those with high scores on the varied dietary pattern (adjusted prevalence ratio, 1.43; 95%CI, 1.01–2.02).

Overall, higher depressive symptoms were generally associated with higher scores on unhealthy and confectionary dietary patterns in pregnancy. In addition, higher depressive symptoms and pregnancy-specific stress were both cross-sectionally related to higher unhealthy dietary pattern scores and lower healthy dietary pattern scores. A similar inverse relationship was observed for depressive symptoms, where higher healthy and Japanese dietary pattern scores were associated with lower prevalence of depressive symptoms.

Stress and depressive symptoms: studies assessing diet quality scores (indices).

Cohort

Three studies investigated associations of stress and/or depressive symptoms with diet quality during pregnancy, using a standardized diet quality index score,18,43,58 and only 1 used a cohort study design.58 Saeed et al58 found that middle-income women with higher depressive symptoms (EPDS score ≥ 9) at 13 weeks had lower HEI scores at 36 weeks (relative risk, 2.58; 95%CI, 1.60–5.23) compared with women who had lower depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms explained 62% of the variance in diet quality during pregnancy, highlighting the importance of mental well-being in relation to diet quality during pregnancy.58

Cross-sectional

Fowles et al43 examined the independent relationships between stress and depressive symptoms on diet quality using the Diet Quality Index–Pregnancy. In a sample of majority Hispanic, low-income women (n = 71), they found that women with diet quality scores below the median (Diet Quality Index–Pregnancy = 53.3) had higher depressive symptoms (mean ± standard deviation, 9.6 ± 5.1 vs 6.7 ± 5.1; P = 0.02) and stress scores (22.1 ± 5.4 vs 19.3 ± 4.8, P = 0.03) than did women with diet quality scores above the median.43 Fowles et al18 built on their previous study by recruiting additional women (n = 118) and combining stress and depressive symptoms into an index called “distress” to examine their synergistic effects on diet quality. They found that higher distress scores were significantly associated with higher poor eating habits scores (β = 0.36; P < 0.01), and were directly (β = −0.23; P < 0.05) and indirectly (β = −0.30; P < 0.05) associated with lower scores on the Diet Quality Index–Pregnancy in their sample of low-income, majority Hispanic women.18 Alternatively, Berube et al54 examined the relationship between depressive symptoms on diet quality using the HEI-2015 and they found no association.

Overall, there is limited reported research on the relationship between stress, depressive symptoms, and diet quality in pregnancy using a standardized diet quality index. Emerging research indicates there are mixed results regarding the relationship between stress and/or depressive symptoms on overall diet quality.18,43,54,58

Stress and depressive symptoms: studies assessing food group and fast-food consumption.

Thirteen articles examined associations of stress and/or depressive symptoms with the consumption of food groups13,15,21,23,40,44,49–51,55,56 or fast-food in pregnancy.14,52 All articles used a cross-sectional design.

Five studies investigated associations of mental health with the consumption of food groups relevant to diet quality or adherence to food-group recommendations as the outcome.13,15,40,55,56 Chang et al13 found that women with higher levels of stress were less likely to eat fruits and vegetables during their first trimester (β = −0.56; P ≤ 0.05); however, this association was not significant in the second or third trimesters. Similarly, women with higher depressive symptoms (EPDS score ≥ 13) were more likely to have higher levels of fat intake during the first trimester (β = 0.67; P ≤ 0.05), but the association was not significant in the second or third trimesters. These findings highlight the importance of measuring stress, depressive symptoms, and dietary intake multiple times throughout pregnancy, because associations may change.

Malek et al40 investigated the relationship between maternal stress and adherence to the Australian food-group recommendations in Australian pregnant women (n = 455) and found that perceived stress was not a significant predictor of adherence to food-group recommendations (β = 0.04; P > 0.05). This was the only study that was informed by an evidence-based theory (ie, Theory of Planned Behavior); however, the researchers did not assess depressive symptoms.

Seven studies examined the relationship between dairy/fermented foods, fish/seafood intake, or soy products on stress, psychological distress, or depressive symptoms in pregnancy.14,21,23,44,49–51 Miyake et al51 found that scoring in the highest quartile for yogurt intake was associated with a lower prevalence of depressive symptoms (Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale score ≥ 16) during pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio, 0.69; 95%CI, 0.48–0.99). Alternatively, Takahashi et al21 found no relationship between the consumption of fermented foods (eg, yogurt, lactic acid beverages, and fermented soybeans) and psychological distress in a large sample of Japanese women (n = 9030).

Only 3 studies examined the relationship between fish or seafood intake and the presence of depressive symptoms in pregnancy,44,49,50 and findings conflicted. For example, Miyake et al50 found that pregnant women who scored in the highest quartile of fish intake had a significantly lower prevalence of depressive symptoms (adjusted odds ratio, 0.61; 95%CI, 0.42–0.87) compared with those in the lowest quartile among a sample of Japanese women (n = 1745). Alternatively, Sontrop et al44 found no relationship between fish intake and depressive symptoms after adjusting for confounders.

Miyake et al23 found that higher intake of total soy products, tofu, tofu products, fermented soybeans, boiled soybeans, and miso soup were independently associated with a lower prevalence of depressive symptoms between extreme quartiles. Adjusted prevalence ratios (95% CI; P for trend) were 0.63 (0.47–0.85; 0.002), 0.72 (0.54–0.96; 0.01), 0.74 (0.56–0.98; 0.04), 0.57 (0.42–0.76; < 0.001), 0.73 (0.55–0.98; 0.03), and 0.65 (0.49–0.87; 0.003), respectively.23

Two studies examined the relationship between fast-food intake and mental health in pregnancy. Overall, these studies found that higher stress and/or higher depressive symptoms were significantly associated with more fast-food intake among pregnant women, which negatively affected their diet quality.14,52 For example, Fowles et al14 found that eating fast food ≥ 3 times in the past week was associated with having significantly higher stress levels (mean ± standard deviation, 23.7 ± 6.8 vs 18.9 ± 4.1; 95%CI, −7.87 to −1.70) and higher depressive symptoms (10.4 ± 6.0 vs 6.8 ± 4.1; 95%CI, −6.45 to −0.71) compared with eating fast food less frequently in a largely Hispanic sample (n = 50) of pregnant women.

Overall, study findings suggest higher depressive symptoms and pregnancy-specific stress were associated with higher unhealthy dietary pattern scores and lower healthy dietary pattern scores. Regarding comprehensive diet quality, higher stress levels and higher depressive symptoms were mostly associated with lower diet quality scores in pregnancy; however, evidence is very limited, and 1 study found no association. Associations of mental health with the consumption of specific food groups were inconclusive. Higher stress levels and higher depressive symptoms may be associated with lower fruit and vegetable consumption and greater quantity of fat intake. There was limited evidence in support of greater quantity of yogurt consumption and lower prevalence of depressive symptoms, and associations of fish/seafood consumption with depressive symptoms were conflicting. Poor mental health was consistently associated with more fast-food consumption. Last, there was a predominant focus on depressive symptoms, with fewer studies investigating stress in relation to diet quality.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we aimed to examine associations of stress and/or depressive symptoms with diet quality during pregnancy; review the measurement tools used to assess stress, depressive symptoms, and diet quality; identify current gaps in the literature; and offer recommendations for future research. Higher stress and higher depressive symptoms were associated with higher unhealthy dietary pattern scores and lower diet quality index scores in pregnancy. Similarly, lower stress and lower depressive symptoms were associated with higher healthy dietary pattern scores. We found limited and inconclusive evidence for associations of stress and/or depressive symptoms with the consumption of specific food groups (ie, fruits, vegetables, dairy, fish/seafood) and fast-food consumption. Overall, there was a dominant focus on depressive symptoms, with fewer studies investigating stress in relation to diet quality in pregnancy.

Conflicting findings could be influenced by sample characteristics, assessment tools used, and timing of assessments. Most studies were conducted with samples outside of the US and with factor analysis to identify dietary patterns, making it difficult to compare specialized patterns (ie, Japanese, common Brazilian, and Western) across populations.46,47 Other authors have highlighted the need for high-quality studies that use standard definitions and methods of assessing diet quality and dietary patterns.30,72,73 Studies that analyze dietary-intake data as a comprehensive diet quality score allow for a more standardized approach to compare findings across different populations. Although many studies used the EPDS to measure depressive symptoms, studies varied in their use of a continuous score or varying cutoff scores,41,59 as evidenced in Table 2. Stress was assessed in multiple ways, including general and pregnancy-specific stress, limiting the ability to compare results across studies. In addition, studies varied in the number of covariates that were controlled for, with 4 studies not adjusting for any covariates13,14,43,58; however authors either found no significant differences in sample characteristics that could pose as confounding factors14,58 or were unable to include covariates, due to small sample sizes.13,43 In terms of timing of assessments, only 1 study reported findings across all 3 trimesters,13 demonstrating varying results as pregnancy progressed.

The majority of the studies in this review were cross-sectional studies; a few were cohort studies. Thus, the direction of the relationship between mental health and diet quality is unclear. A bidirectional association is plausible for the relationship between depressive symptoms and diet quality during pregnancy.41 Nutrition plays a role in influencing biological processes that underlie depressive illnesses,74 such as inflammation,75 the stress response system,76 and oxidative processes.77 Deficiencies in folate, vitamin B12, iron, selenium, zinc, and polyunsaturated fatty acids are associated with depression in the general population.78 Because pregnant women have increased nutrient needs for proper fetal development, they may be more susceptible to the effects of poor nutrition on depression.29 More large-scale, prospective cohort studies are needed that assess stress, depressive symptoms, and diet quality across multiple times to help determine the direction of the relationship.30

A recent feasibility study found that 2 novel, 8-week, stress-reduction interventions facilitated meaningful reductions in stress and depressive symptoms and improved eating behaviors among a sample of multiethnic, low-income, pregnant women with overweight and obesity.79 Future studies could also investigate the effectiveness of stress management interventions in improving diet quality during pregnancy on a larger scale through randomized controlled trials. In addition, because fast-food consumption contributes to poor diet quality, addressing fast-food consumption may be a leverage point for future dietary interventions in pregnancy. Given the wide variability in the way diet quality was assessed, studies should use standardized diet quality indices to enhance consistency in measurement. There is also room for improvement in the racial diversity of study samples.

When considering the racial and ethnic diversity of women in the US studies, 3 studies consisted primarily of Hispanic women (> 45%),14,18,43 and only 2 studies had participant samples of which > 20% were African American.13,52 This is a major gap in the literature, because African American women have disproportionately high rates of obesity,80 worse diet quality,81 increased risk of excessive GWG,82 and are more likely to retain excess weight after delivery1,82–85 compared with their white counterparts. Given the racial disparities related to obesity, GWG, and diet quality between white and African American US women, it is imperative that African American and minority women overall are adequately represented in studies to better understand the contextual factors influencing diet quality and to develop culturally relevant interventions to improve diet quality.

A 2010 Institute of Medicine report specified the need to investigate multiple levels of influence on eating to inform systems-level approaches for obesity prevention in the US86 In only 1 study40 in this review did authors report a specific framework that informed their research (ie, Theory of Planned Behavior), which focused on individual-level factors. Examining multiple levels of influence (eg, intrapersonal-, interpersonal-, and environmental-level factors) can help improve our understanding of these complex relationships and inform policy-, systems-, and environmental-level initiatives to improve health.87

A major strength of this study is that it synthesizes literature on associations of stress and/or depressive symptoms with diet quality during pregnancy, which has not been thoroughly researched. Also, the review is exhaustive because it involved multiple reviewers, involvement of a research librarian, 5 databases, and a thorough review of the measurement tools used to assess stress, depressive symptoms, and diet quality during pregnancy. This study also highlights important gaps in the literature that need to be addressed to achieve health equity. This review identified the following gaps: (1) limited use of longitudinal study designs assessing variables at multiple times throughout pregnancy; (2) paucity of studies that have examined overall diet quality using comprehensive indices; (3) underrepresentation of minority women in samples; and (4) lack of theoretical frameworks that bridge multiple levels of influences to explain diet quality in pregnancy beyond individual-level factors.

Regarding limitations, only English-language papers were included, which may limit the generalizability of findings. Because this is a growing area of research, there are limited sources of data. For example, 4 studies came from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children cohort in England,41,45,49,60 4 studies came from the Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study cohort in Japan,23,46,50,51 and 3 studies came from the same research group in Texas.14,18,43 This may limit the generalizability to other study populations. In addition, the exclusion of broad search terms (eg, health behavior) could have excluded studies that examined eating within assessments of other health behaviors. Search terms were not cross-referenced with the tools used to operationalize eating, which may have inadvertently excluded potentially relevant studies from the search results. Furthermore, interrater reliability was not calculated, so the exact agreement between raters is unknown. Depressive symptoms can coexist or overlap with other mental health conditions (eg, anxiety, generalized negative affect); however, this study is limited to 2 aspects of mental health. Future studies should examine how other mental health concerns could be associated with diet quality. There also could potentially be a confounding variable explaining the associations between mental health and diet quality (eg, poverty, food insecurity, unplanned pregnancy, intimate partner violence) that should be explored in future research.

CONCLUSION

In this review, we highlight the limited amount of research that has been conducted on associations of stress and/or depressive symptoms with diet quality during pregnancy. Overall, the findings suggest that higher stress levels and higher depressive symptoms are associated with unhealthy dietary patterns. Pregnancy-specific stress should be further investigated but is associated with higher scores on unhealthy dietary patterns and lower scores on healthy dietary patterns. Few studies have examined mental health in relation to diet quality indices in pregnancy; however, findings show that higher stress levels and higher depressive symptoms are associated with poorer diet quality index scores. During pregnancy, women have an increased risk of experiencing stress and depressive symptoms, both of which have been associated with poor diet quality.30 In general, diet quality during pregnancy is inadequate,88 and nutrition is very important during pregnancy.5,89 Thus, there is a need to identify and examine factors that contribute to poor diet quality in pregnancy. Clinical health professionals should consider implementing standardized screening practices to identify women with high stress levels and high depressive symptoms during prenatal care visits who may need targeted dietary or mental health interventions or referral to additional resources. Pregnancy is an important time to optimize maternal diet quality and mental well-being to increase chances of positive health outcomes for mothers and children.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions. A.K.B., B.T.M., S.W., J.L., J.M.E., and A.T.K. contributed significantly to the manuscript’s design and conception. A.K.B. drafted the manuscript. B.T.M., S.W., J.L., J.M.E., and A.T.K. critically revised and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding. This project was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (award no. R01HD078407). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was partially supported by a SPARC Graduate Research Grant from the Office of the Vice President for Research at the University of South Carolina. The funders were not involved in the conception, design, performance, or approval of the work.

Declaration of interests. None.

References

- 1. Olson CM. Achieving a healthy weight gain during pregnancy. Annu Rev Nutr. 2008;28:411–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Influences of Pregnancy Weight on Maternal and Child Health: Workshop Report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3. DeVader SR, Neeley HL, Myles TD, et al. Evaluation of gestational weight gain guidelines for women with normal prepregnancy body mass index. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:745–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stuebe AM, Oken E, Gillman MW.. Associations of diet and physical activity during pregnancy with risk for excessive gestational weight gain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:58.e1–58.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Phillips C, Johnson NE.. The impact of quality of diet and other factors on birth weight of infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 1977;30:215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kessler RC. Epidemiology of women and depression. J Affect Disord. 2003;74:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Webb JB, Siega‐Riz AM, Dole N.. Psychosocial determinants of adequacy of gestational weight gain. Obesity. 2009;17:300–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gavin AR, Tabb KM, Melville JL, et al. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14:239–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecology. ACOG committee opinion no. 757: screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132: Doi : 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R.. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:293–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang M-W, Brown R, Nitzke S, et al. Stress, sleep, depression and dietary intakes among low-income overweight and obese pregnant women. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:1047–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fowles ER, Timmerman GM, Bryant M, et al. Eating at fast-food restaurants and dietary quality in low-income pregnant women. West J Nurs Res. 2011;33:630–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hurley KM, Caulfield LE, Sacco LM, et al. Psychosocial influences in dietary patterns during pregnancy. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:963–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Torres SJ, Nowson CA.. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition. 2007;23:887–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bjorntorp P, Rosmond R.. Obesity and cortisol. Nutrition. 2000;16:924–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fowles ER, Bryant M, Kim S, et al. Predictors of dietary quality in low-income pregnant women: a path analysis. Nurs Res. 2011;60:286–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guenther PM, Casavale KO, Kirkpatrick SI, et al. Update of the healthy eating index: HEI-2010. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:569–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Scientific report of the 2015 dietary guidelines advisory committee. 2015. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/PDFs/Appendix-E-3.2.pdf. Accessed January 22, 2018.

- 21. Takahashi F, Nishigori H, Nishigori T, et al. Fermented food consumption and psychological distress in pregnant women: a nationwide birth cohort study of the Japan environment and children’s study. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2016;240:309–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pilšáková L, Rie I, Jagla F.. The physiological actions of isoflavone phytoestrogens. Physiol Res. 2010;59:651–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miyake Y, Tanaka K, Okubo H, et al. Soy isoflavone intake and prevalence of depressive symptoms during pregnancy in Japan: baseline data from the Kyushu Okinawa maternal and child health study. Eur J Nutr. 2018;57:441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tanskanen A, Hibbeln JR, Tuomilehto J, et al. Fish consumption and depressive symptoms in the general population in Finland. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:529–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tanskanen A, Hibbeln JR, Hintikka J, et al. Fish consumption, depression, and suicidality in a general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:512–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Silvers KM, Scott KM.. Fish consumption and self-reported physical and mental health status. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wilcox S, Sharpe PA, Turner-McGrievy G, et al. Frequency of consumption at fast-food restaurants is associated with dietary intake in overweight and obese women recruited from financially disadvantaged neighborhoods. Nutr Res. 2013;33:636–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rodriguez-Bernal CL, Rebagliato M, Chatzi L, et al. Maternal diet quality and pregnancy outcomes. In: Diet Quality. 1st ed.New York, NY: Humana Press; 2013:65–79. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leung BMY, Kaplan BJ.. Perinatal depression: prevalence, risks, and the nutrition link? A review of the literature. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1566–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baskin R, Hill B, Jacka FN, et al. The association between diet quality and mental health during the perinatal period. A systematic review. Appetite. 2015;91:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sparling TM, Henschke N, Nesbitt RC, et al. The role of diet and nutritional supplementation in perinatal depression: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13:1–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leary S. Maternal diet in pregnancy and offspring height, sitting height, and leg length. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:467–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leary SD, Brion M-J, Lawlor DA, et al. Lack of emergence of associations between selected maternal exposures and offspring blood pressure at age 15 years. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67:320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Lauzon-Guillain B, Jones L, Oliveira A, et al. The influence of early feeding practices on fruit and vegetable intake among preschool children in 4 European birth cohorts. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98:804–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jones L, Moschonis G, Oliveira A, et al. The influence of early feeding practices on healthy diet variety score among pre-school children in four European birth cohorts. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18:1774–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kant AK. Indexes of overall diet quality: a review. J Am Diet Assoc. 1996;96:785–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lobel M, J. DeVincent C, Kaminer A, et al. The impact of prenatal maternal stress and optimistic disposition on birth outcomes in medically high-risk women. Health Psychol. 2000;19:544–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Murray D, Cox JL.. Screening for depression during pregnancy with the Edinburgh Depression Scale (EPDS). J Reprod Infant Psychol. 1990;8:99–107. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Kroenke K, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Malek L, Umberger WJ, Makrides M, et al. Predicting healthy eating intention and adherence to dietary recommendations during pregnancy in Australia using the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite. 2017;116:431–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Molyneaux E, Poston L, Khondoker M, et al. Obesity, antenatal depression, diet and gestational weight gain in a population cohort study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19:899–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G, et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence—study limitations (risk of bias). J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fowles ER, Stang J, Bryant M, et al. Stress, depression, social support, and eating habits reduce diet quality in the first trimester in low-income women: a pilot study. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:1619–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sontrop J, Avison WR, Evers SE, et al. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy in relation to fish consumption and intake of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008;22:389–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Barker ED, Kirkham N, Ng J, et al. Prenatal maternal depression symptoms and nutrition, and child cognitive function. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203:417–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Miyake Y, Tanaka K, Okubo H, et al. Dietary patterns and depressive symptoms during pregnancy in Japan: baseline data from the Kyushu Okinawa maternal and child health study. J Affect Disord. 2018;225:552–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Paskulin JTA, Drehmer M, Olinto MT, et al. Association between dietary patterns and mental disorders in pregnant women in Southern Brazil. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2017;39:208–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wall C, Gammon C, Bandara D, et al. Dietary patterns in pregnancy in New Zealand—influence of maternal socio-demographic, health and lifestyle factors. Nutrients. 2016;8:300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Golding J, Steer C, Emmett P, et al. High levels of depressive symptoms in pregnancy with low omega-3 fatty acid intake from fish. Epidemiology. 2009;20:598–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Miyake Y, Tanaka K, Okubo H, et al. Fish and fat intake and prevalence of depressive symptoms during pregnancy in Japan: baseline data from the Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:572–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Miyake Y, Tanaka K, Okubo H, et al. Intake of dairy products and calcium and prevalence of depressive symptoms during pregnancy in Japan: a cross-sectional study. BJOG. 2015;122:336–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chang M-W, Brown R, Nitzke S.. Fast food intake in relation to employment status, stress, depression, and dietary behaviors in low-income overweight and obese pregnant women. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20:1506–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Omidvar S, Faramarzi M, Hajian-Tilak K, et al. Associations of psychosocial factors with pregnancy healthy life styles. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0191723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Berube LT, Messito MJ, Woolf K, et al. Correlates of prenatal diet quality in low-income Hispanic women. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2019;119:1284–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chang M-W, Tan A, Schaffir J.. Relationships between stress, demographics and dietary intake behaviours among low-income pregnant women with overweight or obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22:1066–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Takei H, Shiraishi M, Matsuzaki M, et al. Factors related to vegetable intake among pregnant Japanese women: a cross-sectional study. Appetite. 2019;132:175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lobel M, Cannella DL, Graham JE, et al. Pregnancy-specific stress, prenatal health behaviors, and birth outcomes. Health Psychol. 2008;27:604–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Saeed A, Raana T, Muhammad Saeed A, et al. Effect of antenatal depression on maternal dietary intake and neonatal outcome: a prospective cohort. Nutr J. 2016;15:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Baskin R, Hill B, Jacka FN, et al. Antenatal dietary patterns and depressive symptoms during pregnancy and early post-partum. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pina-Camacho L, Jensen SK, Gaysina D, et al. Maternal depression symptoms, unhealthy diet and child emotional–behavioural dysregulation. Psychol Med. 2015;45:1851–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jiang W, Mo M, Li M, et al. The relationship of dietary diversity score with depression and anxiety among prenatal and post-partum women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2018;44:1929–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sichieri R, Everhart JE.. Validity of a Brazilian food frequency questionnaire against dietary recalls and estimated energy intake. Nutr Res. 1998;18:1649–1659. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bodnar LM, Siega-Riz AM.. A diet quality index for pregnancy detects variation in diet and differences by sociodemographic factors. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:801–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 65. McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF.. Profile of Mood State Manual. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Leung KK, Lue BH, Lee MB, et al. Screening of depression in patients with chronic medical diseases in a primary care setting. Fam Pract. 1998;15:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG.. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams J.. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Curry MA, Burton D, Fields J.. The prenatal psychosocial profile: a research and clinical tool. Res Nurs Health. 1998;21:211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yali AM, Lobel M.. Coping and distress in pregnancy: an investigation of medically high risk women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;20:39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Quirk SE, Williams LJ, O’Neil A, et al. The association between diet quality, dietary patterns and depression in adults: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lai JS, Hiles S, Bisquera A, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary patterns and depression in community-dwelling adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:181–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Jacka F, Berk M.. Food for thought. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2007;19:321–323. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Liu S, Manson JE, Buring JE, et al. Relation between a diet with a high glycemic load and plasma concentrations of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in middle-aged women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:492–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tannenbaum BM, Brindley DN, Tannenbaum GS, et al. High-fat feeding alters both basal and stress-induced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:E1168–E1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Engelhart MJ, Geerlings MI, Ruitenberg A, et al. Dietary intake of antioxidants and risk of Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2002;287:3223–3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bodnar LM, Wisner KL.. Nutrition and depression: implications for improving mental health among childbearing-aged women. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:679–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Laraia BA, Adler NE, Coleman-Phox K, et al. Novel interventions to reduce stress and overeating in overweight pregnant women: a feasibility study. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22:670–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;219:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wang DD, Leung CW, Li Y, et al. Trends in dietary quality among adults in the United States, 1999 through 2010. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1587–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Hernandez DC. Gestational weight gain as a predictor of longitudinal body mass index transitions among socioeconomically disadvantaged women. J Womens Health. 2012;21:1082–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Olson CM, Strawderman MS.. Modifiable behavioral factors in a biopsychosocial model predict inadequate and excessive gestational weight gain. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Parker JD, Abrams B.. Differences in postpartum weight retention between black and white mothers. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:768–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Siega-Riz AM, Evenson KR, Dole N.. Pregnancy-related weight gain—a link to obesity? Nut Rev. 2004;62:105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kumanyika SK, Parker L, Sim LJ. et al., eds. Bridging the Evidence Gap in Obesity Prevention: A Framework to Inform Decision Making. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am J Health Promot. 1996;10:282–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Bodnar LM, Simhan HN, Parker CB, et al. Racial or ethnic and socioeconomic inequalities in adherence to national dietary guidance in a large cohort of US pregnant women. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117:867–877.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Moore VM, Davies MJ, Willson KJ, et al. Dietary composition of pregnant women is related to size of the baby at birth. J Nutr. 2004;134:1820–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]