Abstract

Introduction:

The current shortage of physicians in the United States has potential to dramatically limit access to healthcare. Nurse practitioners (NPs) can provide a cost-effective solution to the shortage, yet few states allow NPs to practice independently.

Purpose:

The purpose of this study was to provide an up-to-date description of the NP workforce and to identify the professional and organizational factors associated with NP care quality.

Methods:

Cross-sectional survey data from a sample of NPs actively employed in four states with reduced or restricted practice (California, Florida, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania) was used. NPs were categorized into acute and primary care. Regression models were fit to estimate the odds of three measures of care quality: overall quality of patient care, NP confidence that patients and their caregivers can manage their care at home, and whether NPs would recommend their practice facility to family and friends.

Results:

Receiving support from administrative staff and physicians was associated with an increase in the three measures of quality. The greatest effects were seen in primary care settings.

Conclusion:

It is imperative that legislators and healthcare administrators implement policies that provide NPs with an environment that supports clinical practice and enhances care delivery.

Keywords: Acute care, nurse practitioners, outcomes, primary care

The United States is facing a physician shortage that is likely to adversely affect access to healthcare unless action is taken. Despite more than 4 decades of policy efforts, the supply of primary and specialty care physicians is projected to fall substantially over the next decade as more physicians retire than enter practice (Association of American Medical Colleges, 2018). Healthcare reform and our aging population will further increase the demand for healthcare services (Gaudette, Tysinger, Cassil, & Goldman, 2015; Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 2018). Nurse practitioners (NPs) could help address this problem, yet current information is lacking about their evolving practice patterns. The most recent large-scale sample survey of NPs was undertaken in 2012 (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2014). Since then, the supply of NPs has grown and their practice conditions have changed as states have altered their scope-of-practice laws and more employers have implemented reduced or restricted practice in their institutions (Brom, Salsberry, & Graham, 2018). Furthermore, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018) reports the demand for NPs will increase by 31% from 2016 to 2026.

Despite the current and projected need for NPs, a recent report shows many states continue to impose legislation that results in reduced or restricted NP practice; only 14 states allow NPs to practice to the full extent of their education (Phillips, 2018). That there are so many states with reduced or restricted practice laws is alarming considering that one study found that states with the most restrictive scope of practice laws are significantly less likely to have NPs available for primary care (Kuo, Loresto, Rounds, & Goodwin, 2013). However, investigators from the National Center for Health Statistics reported no association between NP scope of practice laws and the availability of NPs (Hing & Hsiao, 2015). Furthermore, reduced and restricted scope of practice has not been associated with patient outcomes such as 30-day hospital readmissions or hospitalization for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, diabetes, heart failure, or pneumonia (Ortiz et al., 2018). A recent study suggested organizational regulation of NPs can impede attainment of full scope of practice, where 32% of NPs in states allowing full scope of practice reported they did not have full practice authority because of policies at their institution (Gigli, Dietrich, Buerhaus, & Minnick, 2018). Based on reports from NPs, aspects of the practice environment that support teamwork are at times lacking but are necessary for improvement in patient outcomes and the overall quality of care (Poghosyan, Norful, & Martsolf, 2017). Such improvements to the practice environment are an organizational solution as states struggle to expand scope of practice laws.

In the current study, we examine data from a large sample of NPs surveyed in 2016 to offer new insight into the organizational factors that might contribute to a decrease in the barriers to practice in four states with laws that reduce or restrict NP practice.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a cross-sectional secondary analysis of data from the RN4CAST-US survey of advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) actively licensed in California, Florida, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania (Sloane, Smith, McHugh, & Aiken, 2018). These states were chosen based on their size, different geographic regions of the United States, and the substantial number of APRNs licensed in each state. Additionally, these four states reduce or restrict NP scope of practice.

Sample and Setting

APRNs were sampled from nurse licensure lists provided by the four states. The licensure list included mailing addresses, dates of licensure, and license type (registered nurse [RN] vs. APRN). A 50% random sample of APRNs from each state was generated and subsequently invited to participate in the study. Using a modified Dillman method (Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2014), a series of surveys and reminder postcards were mailed to the homes of all the NPs in the sample (N = 21,629). A total of 6,539 APRNs completed and returned a survey for an overall response rate of 30%. We sampled survey nonrespondents to assess for bias to validate our response rate. Detailed information on organizational context of NP practice and identification of the actual practice site were collected. This additional data collection is a unique feature of this study compared to, for example, the 2012 National Sample of Nurse Practitioners (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2014). Institutional review board approval for the survey and data collection was obtained from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Florida. As outlined in the cover letter that accompanied the questionnaire, completion and return of a survey was the nurse’s consent to participate.

Practice Settings

We defined practice settings based on previous work (Spetz, Fraher, Li, & Bates, 2015), where acute care settings included hospitals and primary care settings included the ambulatory, outpatient, long-term care, home health, physician office, nurse-managed, community, public health, school nurse, correctional facility, and occupational health clinics and related institutions. Of the APRNs who completed and returned a survey, 1,263 NPs reported they worked in an acute care hospital and 2,343 NPs reported working in a primary care setting. The remaining 2,933 surveys were excluded because survey respondents worked in other settings and/or data were missing from those surveys.

NP Characteristics

The survey items included age, gender, race, ethnicity, state of licensure (California, Florida, New Jersey, or Pennsylvania), years in their current position, employment status (full time, part time, per diem), academic degree (master’s degree, doctor ofnNursing practice, or other), and practice specialty. In addition, we asked NPs if they had more than one job.

Practice Characteristics

A series of survey items also asked the NP about practice patterns and practice settings. Questions including whether they bill under their own National Provider Identifier (NPI); scope-of-practice limitations; how many patients they cared for on their most recent day of work (face-to-face and indirectly); whether they practice in a rural area; whether they perform tasks typically assigned to RNs and non-nurse support staff; and time constraints that make it impossible to complete necessary care.

Organizational climate of NPs was assessed with the Nurse Practitioner Organizational Climate Questionnaire (Poghosyan, Nannini, Finkelstein, Mason, & Shaffer, 2013), which is a validated measure of the NP work environment. Nurse practitioners rated characteristics present in their practice environment based on a 4-point Likert-type scale, where 1 = strongly disagree and 4 = strongly agree. The four subscales of the Nurse Practitioner Organizational Climate Questionnaire have high reliability coefficients as evidence by NP-physician relations (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90), independent practice and support (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89), NP-administration relations (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95), and professional visibility (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87). For this study, as in previous work (Poghosyan, Liu, Shang, & D’Aunno, 2016; Poghosyan, Norful, Liu, & Friedberg, 2018), we used the mean score for each subscale of the Nurse Practitioner Organizational Climate Questionnaire.

Nurse Practitioner Care Quality Outcomes

A series of single item questions with established predictive validity (Doblier, Webster, McCalister, Mallon, & Steinhardt, 2005; Wanous & Reichers, 1997) were used to assess NPs’ perspectives on the overall quality of care where they practice (excellent or good vs. fair or poor), confidence that their patients and their caregivers can manage their care at home (very confident or confident vs not at all confident or somewhat confident), and whether NPs would recommend their practice facility to family and friends (definitely yes or probably yes vs. definitely no or probably no).

Analysis

Descriptive analyses included the t test and analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Logistic regression models were fit to estimate the odds of our quality outcomes (quality of care, patients can manage care at home, and recommend facility to family and friends). Significance was set at .05 and STATA 15 (College Station, TX) was used for all computations.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the NPs who participated in our study by practice setting. Nurse practitioners employed in acute care settings were on average younger (47.9 vs. 50.3 years) and were more likely to be male (10.1% vs. 7.9%) when compared with NPs employed in primary care settings. A larger proportion of NPs in acute care settings reported their highest degree as a master’s degree (89.0% vs. 87.2%) or doctor of nursing practice (6.5% vs. 5.5%), whereas the NPs in primary care settings reported a larger proportion of other degrees (4.5% vs. 7.3%). There were no significant differences noted between these two groups of NPs on race, ethnicity, or years in their current position. In both primary care and acute care settings, the majority of NPs reported their educational specialty as a family NP (55.2% and 37.3%, respectively) and that they were certified in a specialty practice by a national certification board (68.8% and 77.6%, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of NPs by Acute Care (n = 1,263) and Primary Care (n = 2,343) Settings

| Acute Care Settings | Primary Care Settings | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | p | |

| Age | 47.9 (10.6%) | 50.3 (11.5%) | <.01 |

| Gender | .02 | ||

| Female | 1,135 (89.9%) | 2,159 (92.2%) | |

| Male | 128 (10.1%) | 184 (7.9%) | |

| Race | .05 | ||

| White | 1,037 (82.1%) | 1,984 (84.7%) | |

| Non-white | 226 (17.9%) | 359 (15.3%) | |

| Ethnicity | .09 | ||

| Hispanic | 96 (7.6%) | 143 (6.1%) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 1,167 (92.4%) | 2,200 (93.9%) | |

| Highest Nursing Degree | <.01 | ||

| Master’s degree | 1,124 (89.0%) | 2,043 (87.2%) | |

| Doctor of Nursing Practice | 82 (6.5%) | 128 (5.5%) | |

| Other | 57 (4.5%) | 172 (7.3%) | |

| Educational Specialty | <.01 | ||

| Adult NP | 387 (31.5%) | 431 (18.8%) | |

| Family NP | 458 (37.3%) | 1,264 (55.2%) | |

| Neonatal NP | 87 (7.1%) | 3 (0.1%) | |

| Pediatric NP | 119 (9.7%) | 213 (9.3%) | |

| Mental Health NP | 30 (2.4%) | 65 (2.8%) | |

| Women’s Health NP | 21 (1.7%) | 167 (7.3%) | |

| Others | 125 (10.2%) | 149 (6.5%) | |

| Certified in a Specialty Practice | <.01 | ||

| Yes | 966 (77.6%) | 1,588 (68.8%) | |

| No | 279 (22.4%) | 719 (31.2%) | |

| Years in Position, mean (SD) | 7.3 (7.0) | 7.7 (7.2) | .07 |

| State of Licensure | <.01 | ||

| Pennsylvania | 395 (31.4%) | 583 (25.0%) | |

| California | 324 (25.7%) | 726 (31.1%) | |

| Florida | 366 (29.1%) | 782 (33.5%) | |

| New Jersey | 174 (13.8%) | 244 (10.5%) | |

Note. NP = nurse practitioner; SD = standard deviation.

Practice Characteristics

The employment characteristics of NPs are shown in Table 2. Comparing NPs employed in acute care settings with those employed in primary care settings, more NPs employed in acute care settings report they worked full-time (86.2% vs. 70.6%). NPs employed in primary care settings reported caring for more patients on their most recent day of work (15 vs. 11), a larger proportion bill under their own NPI (58.6% vs. 43%), and, though small, a larger proportion practice in rural areas (17.5% vs. 12.4%) compared with NPs employed in acute care settings. There were no significant differences between these two groups of NPs on the number of jobs worked. Though not statistically significant, a large proportion of NPs reported doing tasks typically assigned to RNs and non-nurses and that time constraints cause them not to complete necessary care (84% and 88%, respectively).

TABLE 2.

Nurse Practitioner Practice Characteristics and Outcomes by Care Setting

| Acute Care Settings | Primary Care Settings | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | p | |

| Employment Status | <.01 | ||

| Full-time | 1,066 (86.2%) | 1,625 (70.6%) | |

| Part-time | 143 (11.6%) | 610 (26.5%) | |

| Per-diem | 28 (2.3%) | 67 (2.9%) | |

| Works MoreThan One Job | .18 | ||

| Yes | 319 (25.3%) | 545 (23.3%) | |

| No | 944 (74.8%) | 1,798 (76.7%) | |

| Patient Workload, M (SD) | 10.8 (12.5) | 15.0 (16.8) | <.01 |

| Does RN and Staff Work | .94 | ||

| Yes | 1,027 (83.9%) | 1,826 (83.8%) | |

| No | 197 (16.1%) | 360 (16.2%) | |

| Time Constraint to Finish Care | .12 | ||

| Yes | 1,090 (89.3%) | 1,932 (87.5%) | |

| No | 131 (10.7%) | 277 (12.5%) | |

| Bill Under Own NPI | <.01 | ||

| Yes | 525 (43.0%) | 1,318 (58.6%) | |

| No | 695 (57.0%) | 933 (41.4%) | |

| Practices in Rural Area | <.01 | ||

| Yes | 153 (12.4%) | 404 (17.5%) | |

| No | 1,085 (87.6%) | 1,911 (82.6%) | |

| Rate on Quality of Care | <.01 | ||

| Excellent/good | 1,128 (92.4%) | 2,210 (95.6%) | |

| Fair/poor | 93 (7.6%) | 98 (4.4%) | |

| Recommend Facility to Family and Friends | .24 | ||

| Yes | 1,107 (90.9%) | 2,040 (92.1%) | |

| No | 111 (9.1%) | 176 (7.9%) | |

| Confident Patients Can Manage Care at Home | <.01 | ||

| Yes | 1,111 (94.3%) | 2.025 (96.5%) | |

| No | 67 (5.7%) | 73 (3.5%) | |

Note. NPI = National Provider Identifier; RN = registered nurse.

Quality of care in the NPs’ organizations, where NPs employed in acute and primary care settings rated their perceptions of overall quality of care at their practice facilities, confidence that their patients and their patients’ caregivers can manage care at home, and whether they would recommend their practice facility to family and friends is also shown in Table 2.

The mean scores for the Nurse Practitioner Organizational Climate Questionnaire subscales are shown in Table 3. On average, NPs employed in primary care settings reported higher scores for organizational climate on two subscales compared with NPs employed in acute care settings: professional visibility (3.1 vs. 2.9) and NP-administration relations (3.0 vs. 2.7). NPs in acute care settings reported higher scores on one subscale, independent practice and support (3.6 vs. 3.4). NPs employed in acute care and primary care settings, on average, scored the same for the subscale of NP-physician relations (3.4).

TABLE 3.

NP Reports on Organizational Climate Subscales by Care Setting

| Acute Care Settings | Primary Care Settings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Items | M (SD) | M (SD) | p | |

| Professional visibility | 4 | 2.9 (0.8) | 3.1 (0.8) | <.01 |

| NP-administration relations | 9 | 2.7 (0.8) | 3.0 (0.7) | <.01 |

| NP-physician relations | 7 | 3.4 (0.5) | 3.4(0.6) | 0.84 |

| Independent practice and support | 9 | 3.6 (0.5) | 3.4 (0.5) | <.01 |

Note. NP = nurse practitioner.

Nurse Practitioner Reports on Quality of Care

Acute Care Settings

Table 4 shows the odds ratios that estimate NP reports on care quality. In the models that estimated NP ratings on the quality of care, a 1-unit increase in NP-administration and NP-physician relations was associated with an almost 3-fold and 2-fold increase in the odds that NPs would rate the quality of care provided at their practice as excellent/good (OR = 2.86, p ≤ .001; OR = 2.06, p ≤ .001). A 1-unit increase in NP-physician relations was associated with a 2-fold increase in the odds that NPs would report they feel confident that patients and their caregivers can manage care at home (OR = 2.12, p ≤ .05). A 1-unit increase in NP-administration relations was associated with a 3-fold increase in the odds that NPs would recommend their practice facility to family and friends (OR = 2.94, p ≤ .001).

TABLE 4.

Odds Ratios That Estimate Nurse Practitioner Reports on the Quality of Patient Care by Care Setting

| Acute Care Setting | Primary Care Setting | |

|---|---|---|

| Nurse Reports on Quality of Care | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Excellent/Good Quality of Care | ||

| NP-administration relations | 2.86 (1.77–4.62)a | 3.68 (2.37–5.70)a |

| NP-physician relations | 2.06 (1.27–3.33)a | 1.68 (1.09–2.57)b |

| Independent practice and support | 1.84 (1.11 −3.05)b | |

| Confident Patients Can Manage Care at Home | ||

| NP-administration relations | 2.99 (1.87–4.77)a | |

| NP-physician relations | 2.12 (1.18–3.84)b | |

| Recommend Facility to Family and Friends | ||

| NP-administration relations | 2.94 (1.92–4.52)a | 3.10 (2.23–4.31)a |

| NP-physician relations | 2.16 (1.55–3.01)a | |

| Bills under own NPI | 1.73 (1.21 −2.48)c | |

Note. CI = Confidence interval; NP = nurse practitioner; NPI = National Provider Identifier; OR = odds ratio. Controls included all items listed on previous tables.

p < 0.001.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

Primary Care Settings

We found similar yet unique findings on the ratings of care quality from NPs employed in primary care when compared to NPs employed in acute care settings. In the models that estimated the perceived overall quality of care, a 1-unit increase in NP-administration relations, NP-physician relations, and independent practice and support were associated with a 3.7-fold and 68% and 84% increase in the odds that NPs would rate the quality of care as excellent/good (OR = 3.68, p ≤ .001; OR = 1.68, p ≤ .05; OR = 1.84, p ≤ .05). A 1-unit increase in NP-administration relations was associated with an almost 3-fold increase in the odds that NPs were confident that patients and their caregivers can manage their care at home (OR = 2.99, p ≤ .001). A 1-unit increase in NP-administration and NP-physician relations was associated with a 3-fold and 2-fold increase in the odds that NPs would recommend their practice facility to family and friends (OR = 3.10, p ≤ .001; OR = 2.16, p ≤ .001). Additionally, the ability to bill under one’s own NPI was associated with a 73% increase in the odds that NPs recommend their practice facility to family and friends (OR = 1.73, p ≤ .01).

Discussion

To our knowledge, the findings from this study represent the most recent large-scale survey of nurse practitioners across acute and primary care. We found specific aspects of the practice environment, such as NP-administration relations, NP-physician relations, and independent practice and support, to be consistently associated with reported quality of care across settings. This finding is similar to an earlier report on nurse practitioners where improved NP-administration relations was associated with improved care quality in asthmatics (Poghosyan et al., 2016) and independent practice and support were associated with improved care in patients with cardiovascular disease (Poghosyan et al., 2018).

We reported on NP workload defined as the number of patients cared for during the most recent shift, though little is known about this measure among advanced providers in acute and primary care settings. Some research suggests the mental demand and effort is a large contributor to NP workload in critical care; other factors such as procedures, discharges, and admissions are necessary for a complete measure of NP workload (Dye & Wells, 2017). We also noted that over 80% of NPs across settings reported they are regularly assigned to RN and non-nurse support staff, suggesting NPs may have less access to support personnel than is usual for physicians. Perhaps associated with having to undertake work that could be done by a RN or other staff member, more than 80% of NPs reported time constraints on finishing their work. Yet, we found neither of these to be associated with our care outcomes of interest, which may indicate that support from administration and colleagues (physicians) can offset the deleterious effects associated with shift workload and assigned tasks.

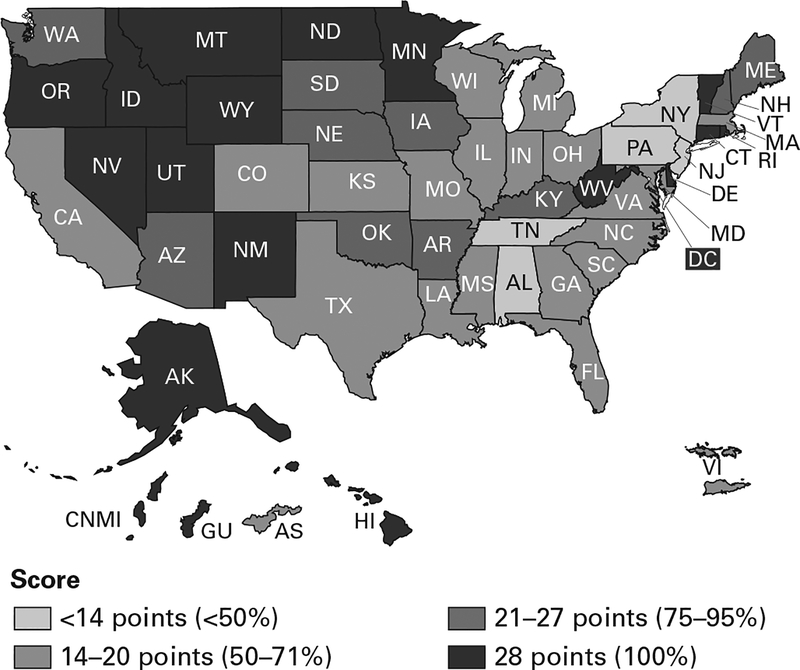

Although the four states in our study are similar in scope of practice (reduced and restricted), we found quite a bit of variation on the title of NPs and how they are regulated by state. For example, in California, the NP, certified nurse midwife, certified registered nurse anesthetist, and certified clinical nurse specialist are defined by statute, but scope of practice is defined by education standards rather than by statute or regulation; furthermore, national board certification is not required. Additionally, these nurses function under a protocol developed by a physician and the administration of their healthcare facility. They are not legally authorized to admit patients to the hospital, but individual hospitals may grant these nurses hospital privileges. In Florida, scope of practice is defined in statute where the NP must hold national board certification and establish a protocol with a doctor of medicine (MD), doctor of osteopathic medicine (DO), or dentist (Phillips, 2018). New Jersey NP scope of practice is defined in statute where national board certification is required (Phillips, 2018). The NP must practice in collaboration with a physician and is required to have a joint protocol with said physician for prescribing medications and devices. The Pennsylvania Board of Nursing defines the advanced practice nurse as a certified registered nurse practitioner (CRNP) who works in collaboration with a physician. The scope of practice of the CRNP is defined in statute and the Pennsylvania Department of Health authorizes hospitals to define the scope of privileges. Furthermore, none of the four states included in our analyses have fully implemented the APRN Consensus Model (Figure 1) even though these states have a total of 76,926 licensed APRNs (Phillips, 2018). The stark differences in regulation and role delineation at the state level highlights the struggle to implement the Consensus Model.

FIGURE 1. Implementation Status of the APRN Consensus Model Across the United States and Its Territories.

Source: APRN consensus implementation status. (2018, April 23). NCSBN website. Retrieved from https://www.ncsbn.org/5397.htm

Surprisingly, we did not find an association between scope of practice and our three measures of care quality. These findings are similar to previous work, in which scope of practice was not associated with outcomes (Kurtzman et al., 2017; Ortiz et al., 2018) despite improved care delivery differences that favored less restricted states. We suspect our findings were due to lack of variation in scope of practice in our sample of NPs because California, Florida, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania all restrict NP practice to some degree (restricted practice in California and Florida and reduced practice in New Jersey and Pennsylvania). However, we believe our findings are the first to show that despite scope of practice restrictions, administrative and collaborative support can improve quality of care as measured by NPs’ perceptions.

Our findings show that even modest improvements within organizations, such as relationships between administration and physicians, is one strategy to improve the quality of care across practice settings. In fact, we reported similar findings on the practice environment of RNs working in hundreds of hospitals over multiple time points (Aiken, Clarke, Sloane, Lake, & Cheney, 2008; Kutney-Lee, Wu, Sloane, & Aiken, 2013). Although a number of factors such as age, ethnicity, and academic degree are impossible or difficult to change, many regulations at the state and organizational level can be changed at little or no cost when compared to the costs associated with hiring and training new providers and the financial penalties associated with poor patient care outcomes.

Implications

Our findings should encourage policymakers and healthcare administrators to work in an expeditious manner to modify or remove restrictions on NP scope of practice nationwide. Furthermore, the creation and support of a practice environment that fosters autonomous and collaborative practice, such as improving NP relations with administration and physicians, can leverage our ability to recruit and retain NPs in roles across practice settings. Doing so will provide a solid foundation for the NP workforce moving forward and improve the quality of NP care and patient outcomes.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, our data were limited to those from a self-report survey of NPs in four states; however, we strategically chose the states with the largest number of practicing NPs for our sampling frame. Second, though our 30% response rate might seem low to some, it is within the current expectation of survey research, and, as in previous work (Smith, 2009), we sampled survey nonrespondents to validate our response rate.

Conclusion

As the demands for healthcare in the United States increase, it is imperative that we implement care models that foster a less restrictive collaborative practice for NPs. There is substantial evidence to suggest state and local agencies, as well has healthcare organizations, have in many ways restricted NP practice to the point where it has the potential to jeopardize the stability of the NP workforce. The NP workforce must be recognized for its valuable contributions if we are to sustain a healthcare system that benefits all.

Contributor Information

Jeannie P. Cimiotti, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University..

Yin Li, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University..

Douglas M. Sloane, School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania..

Hilary Barnes, School of Nursing, University of Delaware..

Heather M. Brom, School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania..

Linda H. Aiken, School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania..

References

- Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET & Cheney T (2008). Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. Journal of Nursing Administration, 38(5), 223–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of American Medical Colleges. (2018). The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2016 to 2030. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Brom HM, Salsberry PJ, & Graham MC (2018). Leveraging healthcare reform to accelerate nurse practitioner full practice authority. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 30(3), 120–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. (2018, April 13). Occupational outlook handbook: Nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and nurse practitioners. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/nurse-anesthetists-nurse-midwives-and-nurse-practitioners.htm

- Dillman DA, Smyth JD, & Christian LM (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Doblier CL, Webster JA, McCalister KT, Mallon MW, & Steinhardt MA (2005). Reliability and validity of a single-item measure of job satisfaction. American Journal of Health Promotion, 19(3), 194–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye E, & Wells N (2017). Subjective and objective measurement of neonatal nurse practitioner workload. Advances in Neonatal Care, 17(4), E3–E12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudette E, Tysinger B, Cassil A, & Goldman DP (2015). Health and healthcare of Medicare beneficiaries in 2030. Forum for Health Economics & Policy, 18(2), 75–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigli KH, Dietrich MS, Buerhaus PI, & Minnick AF (2018). Regulation of pediatric intensive care unit nurse practitioner practice: A national survey. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 30(1), 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2014). Highlights from the 2012 national sample survey of nurse practitioners. Rockville, MD: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Hing E, & Hsiao CJ (2015). In which states are physician assistants or nurse practitioners more likely to work in primary care? Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants, 28(9), 46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo YF, Loresto FL, Rounds LR, & Goodwin JS (2013). States with the least restrictive regulations experienced the largest increase in patients seen by nurse practitioners. Health Affairs, 32(7), 1236–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutney-Lee A, Wu E, Sloane DM, & Aiken LH (2013). Changes in hospital nurse work environments and nurse job outcomes: an analysis of panel data. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(2), 195–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzman ET, Barrow BS, Johnson JE, Simmens SJ, Infeld DL, & Mullan F (2017). Does the regulatory environment affect nurse practitioners’ pattern of practice or quality of care in health centers? Health Services Research, 52(Suppl 1), 437–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. (2018). Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Healthcare Delivery System. Retrieved from http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun18_medpacreporttocongress_sec.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz J, Hoffer R, Bushy A, Lin Y, Khanijahani A, & Bitney A (2018). Impact of nurse practitioner scope of practice regulations on rural population health outcomes. Healthcare, 6(2), 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips SJ (2018). 30th Annual APRN Legislative Update: Improving access to healthcare one state at a time. The Nurse Practitioner, 43(1), 27–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poghosyan L, Liu J, Shang J, & D’Aunno T (2016). Practice environments and job satisfaction and turnover intentions of nurse practitioners: Implications for primary care workforce capacity. Healthcare Management Review, 42(2), 162–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poghosyan L, Nannini A, Finkelstein SR, Mason E, Shaffer JA (2013). Development and psychometric testing of the Nurse Practitioner Primary Care Organizational Climate Questionnaire. Nursing Research, 62(5), 325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poghosyan L, Norful AA, Liu J, & Friedberg MW (2018). Nurse practitioner practice environments in primary care and quality of care for chronic diseases. Medical Care, 56(9), 791–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poghosyan L, Norful AA, & Martsolf GR (2017). Primary care nurse practitioner practice characteristics: Barriers and opportunities for interprofessional teamwork. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 40(1), 77–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloane DM, Smith HL, McHugh MD, & Aiken LH (2018). Effect of changes in hospital nursing resources on improvements in patient safety and quality of care: A panel study. Medical Care, 56(12), 1001–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HL (2009). Double sample to minimize bias due to non-response in a mail survey. Philadelphia, PA: Population Studies Center, University of Pennsylvania. PSC Working Paper Series, No. 09–05. [Google Scholar]

- Spetz J, Fraher E, Li Y, & Bates T (2015). How many nurse practitioners provide primary care? It depends on how you count them. Medical Care Research and Review, 72(3), 359–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanous JP, & Reichers AE (1997). Overall job satisfaction: How good are single-item measures? Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(2), 247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]