Abstract

Molecular conjugation refers to methods used in biomedicine, advanced materials and nanotechnology to link two partners — from small molecules to large and sometimes functionally complex biopolymers. The methods ideally have a broad structural scope, proceed under very mild conditions (including in H2O), occur at a rapid rate and in quantitative yield with no by-products, enable bioorthogonal reactivity and have zero toxicity. Over the past two decades, the field of click chemistry has emerged to afford us new and efficient methods of molecular conjugation. These methods are based on chemical reactions that produce permanently linked conjugates, and we refer to this field here as covalent click chemistry. Alternatively, if molecular conjugation is undertaken using a pair of complementary molecular recognition partners that associate strongly and selectively to form a thermodynamically stable non-covalent complex, then we refer to this strategy as non-covalent click chemistry. This Perspective is concerned with this latter approach and highlights two distinct applications of non-covalent click chemistry in molecular conjugation: the pre-assembly of molecular conjugates or surface-coated nanoparticles and the in situ capture of tagged biomolecular targets for imaging or analysis.

Progress in many technical fields such as biomedicine, advanced materials and nanotechnology would be greatly enhanced given the availability of highly efficient molecular conjugation methods. These methods are essential for a myriad of purposes, including connection of two different molecules, immobilizing molecules to surfaces, crosslinking polymer networks and coating nanoparticles with molecules1. The conjugation partners range from small organic and inorganic molecules to large and functionally complex biopolymers. Ideally, molecular conjugation methods should have a broad structural scope and proceed at rapid rates and in quantitative yields even under very mild conditions, including operation in H2O. Practical requirements mandate an absence of by-products and zero toxicity but also bioorthogonal reactivity, such that no undesired side reactions with common biological functional groups occur. The early days of molecular conjugation saw chemists being limited to reactions mostly based on conversions of organic carbonyls. Although these reactions can be useful, they have drawbacks because they are often slow and result in undesired reactions with molecules other than the target. Over the past two decades, the field of click chemistry has emerged to give us access to a suite of new chemical methods to achieve molecular conjugation2. At the time of writing, there are almost 200 review articles with ‘click chemistry’ in the title. In this Perspective, we refer to this enormous body of work as covalent click chemistry because it is based on chemical reactions with high thermodynamic driving forces that produce permanently linked conjugates under very mild conditions (BOX 1). This classification allows us to define non-covalent click chemistry as a newer and distinct chemical method to achieve molecular conjugation, whereby a pair of complementary molecular recognition partners (arbitrarily called host and guest) associate to form a thermodynamically stable non-covalent complex (FIG. 1). Compared with covalent bonds, non-covalent bonds are weaker and usually form more quickly. The molecular structure of the complex is governed by a (usually cooperative) set of non-covalent interactions between the partners. Non-covalent click reactions can proceed with a high degree of structural selectivity, such that the association of two molecules that do not have complementary host–guest structures is thermodynamically disfavoured and not observed. Thus, molecular conjugation based on non-covalent click chemistry can be programmed to occur spontaneously and selectively by designing association partners with structures that include a complementary host and guest component, respectively. It is important to note that our definition of non-covalent click chemistry does not include colloidal self-assembly processes because these are primarily driven by relatively nonspecific interactions such as Coulombic attraction or the hydrophobic effect3. Although colloidal self-assembly processes can enable us to fabricate 3D nanoscale objects such as vesicles and soft nanoparticles, these processes do not have sufficient selectivity relative to the atomically precise non-covalent conjugation procedures that we now describe.

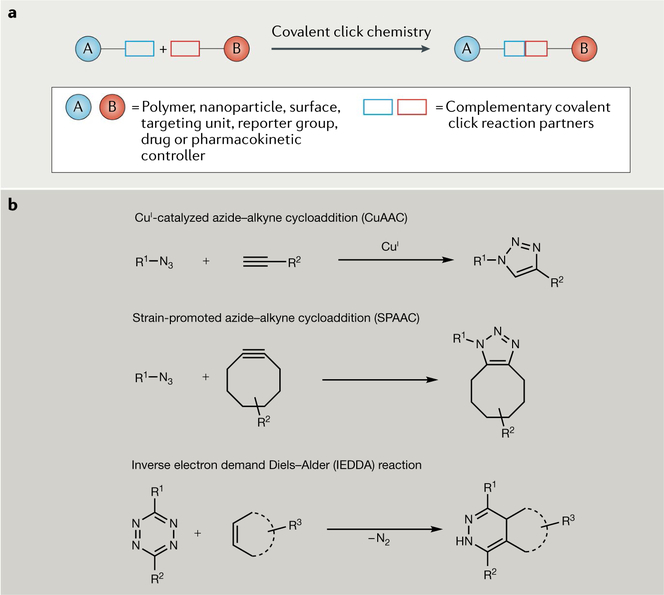

Box 1 |. Covalent click chemistry.

The concept of click chemistry was introduced in 2001 as a set of powerful, reliable and selective reactions for the rapid synthesis of useful new compounds2. Since then, covalent click chemistry has been utilized for molecular conjugation in diverse fields including drug design, bioconjugation, polymer chemistry, materials science, nanotechnology and molecular imaging62,63, as shown in the general schematic in part a of the figure. In the beginning, three classes of ‘spring-loaded’ chemical reactions were originally recommended for covalent click chemistry: nucleophilic opening of strained rings, cycloadditions and protecting group reactions. Cycloaddition reactions, in particular those shown in part b of the figure, have emerged as the most popular.

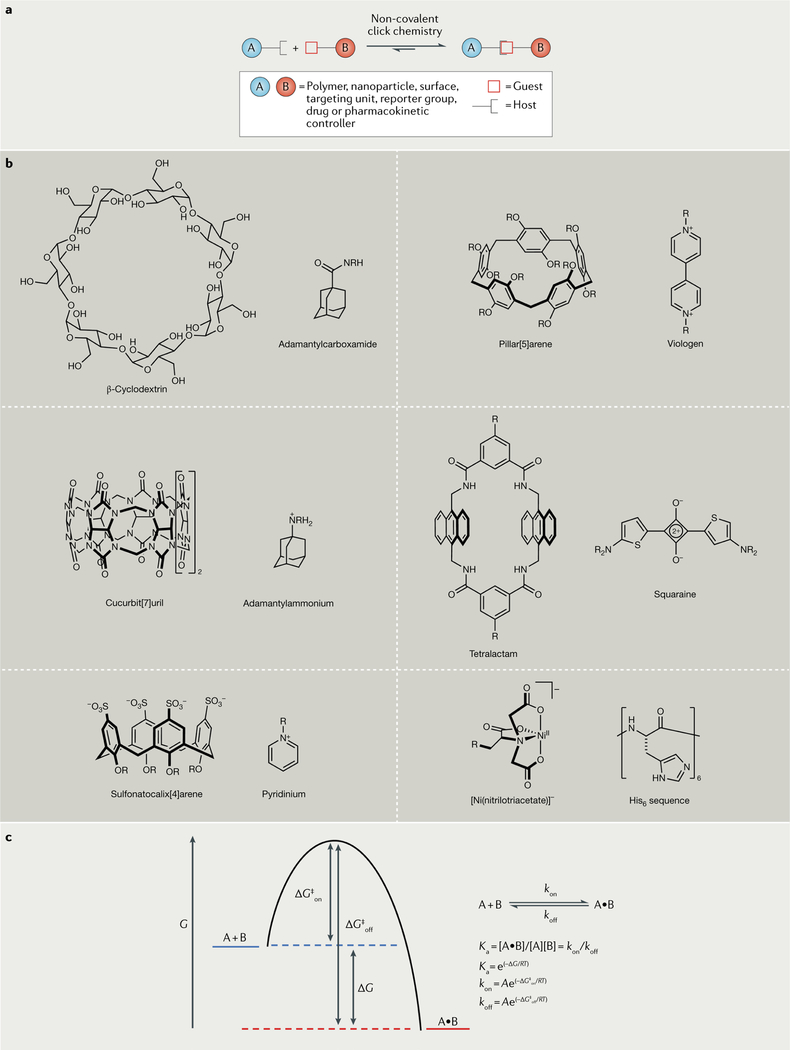

Fig. 1 |. Non-covalent click chemistry.

Non-covalent click chemistry employs a pair of complementary molecular recognition partners, arbitrarily called host and guest. As shown in part a, molecular conjugation occurs when host-functionalized molecule A associates with guest-functionalized molecule B to form a thermodynamically stable 1:1 complex A•B. Part b depicts structures of six pairs of synthetic host–guest partners that have been used for molecular conjugation using non-covalent click chemistry. Association between the complementary partners is driven by interactions that include hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic effects, π–π stacking, electrostatic effects (including ion–dipole interactions) and metal–ligand bonding. A general Gibbs free energy profile is given for association between A and B and is drawn in part c. The change in Gibbs free energy ΔG is related to the association constant Ka, which is, in turn, the quotient of the rate constants for complex formation (kon) and dissociation (koff). The versatility and usefulness of non-covalent click chemistry is greatest when the values of Ka and kon are high.

Covalent click chemistry

Although this Perspective pays particular attention to bioconjugation applications, it is important to realize that covalent click chemistry is also used for many other applications, including small-molecule and polymer synthesis, material fabrication and surface modification. The rate of a molecular conjugation reaction is usually not a crucial consideration if we speak of a standard laboratory synthesis that can be conducted for a long period of time. However, there are many situations in which rapid rates of molecular coupling are crucial. For example, there is an emerging trend to prepare molecular conjugates and functionalized nanoparticles by procedures based on flow methods and microfluidics4,5. Flow chemistry is a particularly useful way to make molecular probes for imaging or multifunctional nanoparticles for imaging and therapy6–8. By definition, the time that reactants come into contact with each other is relatively short, such that flow syntheses must be based on reactions that are rapid at room temperature and/or do not disrupt the delicate architecture of self-assembled nanoparticles such as liposomes, microvesicles or exosomes. Rapid molecular conjugation or selective molecular capture under mild conditions is also a requirement in modern biomedical applications in proteomics or chemical biology. For example, a bioconjugation process has to be complete within a few minutes if the goal is to selectively label a biomolecular target in its native setting9. Indeed, mild conditions are needed if the bioconjugated product is fragile, as is the case for a covalently labelled biomolecule embedded in the plasma membrane of a living cell10.

The variety of covalent click reactions presently available is impressive and extremely useful, but the approach is not without limitations, especially when conjugation has to be achieved under dilute conditions in physiological media — conditions under which many covalent click reactions are too slow to be effective11. These limitations have been articulated and motivated the development of next-generation covalent click reactions that proceed at extremely rapid rates with high levels of bioorthogonal selectivity12. A conceptually related approach has made use of enzymology to develop covalent protein tagging technologies such as Halo-tag, CLIP-tag and Snap-tag13. Each of these tagging methods is based on a selective covalent reaction between a modified enzyme and a complementary small-molecule partner. Thus, the genetically encoded target enzyme (or a larger fused protein construct) is permanently tagged by the small-molecule partner, which usually contains a fluorescent component that enables subsequent microscopy of the labelled cells. The high target selectivity and mild conditions of these tagging technologies makes them quite amenable for studies that aim to track a specific protein within a living cell culture. However, the scope of these technologies is limited in that one of the coupling partners must be a large enzyme. This can be problematic because this size lowers the surface density of the attached fluorescent tag, making it difficult to image the labelled target. In addition, the enzymes can be susceptible to proteolysis or denaturation, making them incompatible with technologies that require the molecular conjugates to survive for long periods under harsh conditions. Lastly, we note that two molecules can be covalently conjugated using enzyme-catalysed ligation reactions14. This approach has many desirable aspects — not least that the reactions proceed under mild conditions — but also has important undesirable aspects. For example, relatively slow reaction rates, unreliable reaction yields and the requirement of specific ligation enzymes limit generality.

Non-covalent click chemistry

Biological chemistry has afforded us several non-covalent click reactions, the best known of which is based on the biotin–(strept)avidin association pair. Avidin (and its bacterial analogue streptavidin) is a tetrameric protein with a total molecular weight of ~64 kDa and four equivalent binding sites, each of which has a very high and selective affinity for the small molecule biotin and its derivatives15. The rates of biotin–(strept)avidin association are very high (kon ≈ 107 M−1 s−1), and the equilibrium association constants, Ka, fall in the range of 1013–1015 M−1, even in strongly competitive biological media. The kinetic and thermodynamic stability of biotin–(strept)avidin conjugates are reflected in their many applications, and in certain cases ongoing commercial and academic research efforts are targeted at optimizing the association pair15,16.

There are other, less popular biological association pairs that can be used for non-covalent click chemistry. For example, Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase (eDHFR) is an enzyme that has a high affinity for molecules containing the folate analogue trimethoprim (TMP). The conjugation of these two units to form non-covalent eDHFR–TMP pairs is very thermodynamically favourable, with Ka being on the order of 109 M−1 (REF.17). The eDHFR–TMP pairing has been used to non-covalently tag fused proteins that have been genetically expressed inside living mammalian cells, thereby enabling cell microscopy studies. A related method to non-covalently tag fused proteins inside cells employs fluorogen-activating proteins18. These proteins are genetically encoded single-chain antibodies that have the capacity to bind specific fluorescent organic dyes with nanomolar affinity (1/Ka ≈ 10−9 M). Moreover, the dye’s fluorescence quantum yield is greatly enhanced when it is part of a non-covalent complex, making the system well suited for microscopy.

A versatile method to tag a protein outside a cell exploits metal coordination chemistry to form bonds between a host that contains a transition metal cation and a guest (typically a protein) with appropriate donor groups19. The process is not a pure example of non-covalent click chemistry because metal–ligand bonds often have substantial covalent character. Nevertheless, there is close functional similarity in that metal coordination can be fast, reversible and selective. The best-known manifestation of this technology uses a host molecule with one or more [Ni(nitrilotriacetate)]− (Ni-NTA, FIG. 1) moieties (or next-generation versions thereof20) to label or capture proteins that contain a sequence of 6–12 consecutive His residues. These His-tagged proteins feature basic N atoms that can strongly chelate the Niii site in the host molecule21.

Unsurprisingly, a variety of oligonucleotides have been exploited in non-covalent click chemistry. One approach that is analogous to the fluorogen-activating proteins described above uses fluorogen-activating RNA aptamers to selectively bind dyes with Ka values in the range of 106–108 M−1 and switch on their fluorescence22. Another approach involves exploiting the sequence-selective formation of oligonucleotide duplexes (hybridization), in which complementary oligonucleotides with 16–22 nucleobases associate with nanomolar affinity23. Although oligonucleotides (especially DNA) are chemically stable, they are readily degraded by nuclease enzymes, therefore effective operation in biological media requires structurally modified oligonucleotides that resist nuclease action.

Association pairs based on proteins, peptides and oligonucleotides are important members of the non-covalent click chemistry toolbox. However, as was noted above, the relatively large size and biochemical fragility of these biomolecules limits their utility in several important technical applications. Thus, there is a need to develop synthetic association pairs that have relatively low molecular weights but still have high thermodynamic and kinetic stabilities at ambient temperature (Ka and kon, respectively). The field of host–guest chemistry is a logical realm in which to find non-covalent association pairs with suitably high Ka values24–26 (TABLE 1). For example, cucurbiturils, pillarenes, cyclodextrins, calixarenes and tetralactams are H2O-soluble organic macrocycles that can host specific types of small-molecule guests. The number of repeat units in the macrocyclic hosts defines the size of the host, which, in turn, governs the size of the guest that binds with the highest affinity (the most complementary guest). Of these synthetic hosts, those with the highest guest affinity are the cucurbiturils, which can bind complementary guests with Ka values in the range 109–1015 M−1 and are featured in many studies describing non-covalent click chemistry with ultra-high-affinity hosts. Another set of host molecules with intrinsically high guest affinity are the tetralactams, which can bind fluorescent squaraine dyes with Ka values in the range of 108–1011 M−1. By contrast, the pillarenes, cyclodextrins and calixarenes have lower affinities for guests, making them less suitable for many conjugation applications. One way to increase the Ka values of these systems is to exploit multivalency, in which we use one molecule featuring n host functionalities and another molecule with n complementary guest functionalities.

Table 1 |.

Host–guest pairs for non-covalent click chemistry, typical association constants (Ka) in H2O

| Host | Guest | Ka (M−1) | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Strept)avidin (high M protein tetramer) | Biotin derivatives (low M organics) | 1012–1014 | 64 |

| Escherichia coli dihydrofolate reductase (high M protein) | Trimethoprim derivatives (low M organics) | 109 | 17 |

| Fluorogen-activating proteins (moderate M single-chain antibodies) | Fluorescent dyes (low M organics) | 107–109 | 65 |

| Nickel-nitrilotriacetate (moderate M synthetic metal complex) | Polyhistidine derivatives (moderate M peptides) | 107–1010 | 20,21 |

| RNA aptamer (moderate M synthetic biomolecule) | Fluorescent dyes (low M organics) | 106–109 | 22,66 |

| Single-stranded DNA (moderate M synthetic biomolecule) | Complementary single-stranded DNA (moderate M synthetic biomolecule) | 108–1010 | 50,67 |

| Cucurbit[n]urils (low M organics) | Hydrophobic organic cations (low M) | 109–1015 | 68,69 |

| Tetralactams (low M organics) | Fluorescent squaraine dyes (low M organics) | 107–1011 | 70,71 |

| Pillar[n]enes (low M organics) | Hydrophobic organic molecules (low M) | 103–106 | 72 |

| Cyclodextrins (low M organics) | Hydrophobic organic molecules (low M) | 103–106 | 73 |

| Sulfonatocalixarenes (low M organics) | Hydrophobic organic cations (low M) | 104–106 | 42 |

The pairs are ordered according to their approximate association constants. M, molecular weight.

There are two broadly distinct ways that non-covalent click chemistry is utilized for molecular conjugation. One is the pre-assembly of molecular conjugates for subsequent deployment and the other is in situ capture of target molecules. The next two sections describe how non-covalent click chemistry enables these different processes to be realized.

Pre-assembly of molecular conjugates

Pre-assembly is a molecular synthesis process in which stoichiometric quantities of A and B are mixed and a conjugated product A•B is formed. The name pre-assembly stems from the complex A•B being assembled before being administered, which contrasts with separate dosage of A and B, for example. In the case of covalent click chemistry, this process affords, in principle, a permanently connected A•B conjugate that can be purified by standard laboratory methods. In the case of non-covalent click chemistry, high concentrations of the association partners are mixed in H2O so as to favour the assembled A•B complex Typically, there is little or no attempt to purify an H20-soluble A•B product, which is instead used as a concentrated stock solution that is dispensed on demand. It is important to realize that when using non-covalent pre-assembly there is no absolute requirement that Ka and kon be extremely high. In principle, Ka and kon only have to be high enough to ensure quantitative formation of the soluble A•B complex as a concentrated solution. Many biological imaging or drug delivery procedures are complete within a short time frame (minutes to hours), such that even if a dispensed aliquot of stock solution is diluted to the very low concentrations at which A•B dissociation is thermodynamically favoured, the pre-assembled complex has sufficient kinetic stability (sufficiently low koff) to remain intact over the course of the experiment. To date, only a few reports exist of designing complexes with a high kinetic stability (slow koff) for use in non-covalent pre-assembly of durable, H2O-soluble27 or surface-immobilized conjugates20.

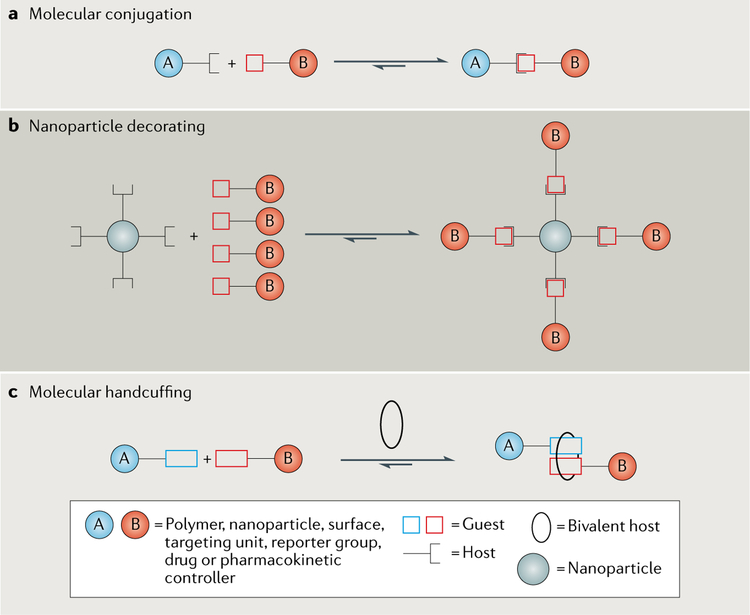

There are three conceptually different non-covalent click chemistry approaches to pre-assembling a molecular conjugate. The first and simplest approach is molecular conjugation (FIG. 2a) of two monovalent components to give a 1:1 complex. For example, a tetralactam host, modified with a cancer-targeting peptide, binds a fluorescent squaraine dye to afford a pre-assembled complex that has been used as a targeted fluorescence probe for tumour imaging in a mouse model of cancer28. In a similar vein, non-covalent click chemistry can be used to attach a polymer chain to a protein, thereby modifying the protein’s solubility and pharmacological properties. A common strategy is to use a host with an appended polyethylene glycol (PEG) moiety and high affinity for a specific region on a protein’s surface29–32. An attractive feature of non-covalent PEG–protein linkages is the possibility of releasing the PEG chain once the complex has reached its target so as not to interfere with the binding of the protein to its biological receptor33. The reversibility of non-covalent clicked linkages has also been exploited to crosslink polymer networks to afford dynamic and self-healing hydrogels for various biomedical applications34–36. The second pre-assembly approach uses non-covalent click chemistry to coat a multivalent species, such as a nanoparticle, with multiple copies of a targeting unit and/or imaging reporter group (FIG. 2b). Here, the nanoparticle must first be decorated with multiple copies of a host molecule (for example, a cucurbituril37–39, cyclodextrin40, pillarene41 or calixarene42), after which the corresponding targeting and/or imaging guest can simply be added to give a targeted nanoparticle for theranostic applications. The third pre-assembly procedure exploits the unique capacity of the organic macrocyclic host cucurbit[8]uril to simultaneously encapsulate two non-identical guests and thus act as ‘molecular handcuffs’ (FIG. 2c). This approach has been used to conjugate small and large biomolecules43, to create supramolecular polymers44 and to append drugs to the surface of nanoparticles45.

Fig. 2 |. Pre-assembly of molecular conjugates using non-covalent click chemistry.

Each pre-assembly process uses the complementary host and guest binding partners illustrated in FIG. 1 and TABLE 1. a | The simplest case of molecular conjugation involves binding between a monovalent host and guest, which can afford functional products such as H2O-soluble molecular probes for imaging, modified proteins with improved pharmaceutical properties or crosslinked hydrogels. b | A nanoparticle can be decorated with host moieties such that it can be functionalized with guests, for example, small molecules that bind certain proteins. In this way, conjugation affords targeted nanoparticles for theranostic applications. c | Molecular handcuffing is a linking method that connects two mono-valent moieties with a third bivalent host. This process can give supramolecular polymers or drug-coated nanoparticles.

In situ molecular capture

In situ capture is a multistep process wherein two components A and B are added to a complicated multicomponent mixture (or they are generated in situ by metabolic action on suitable precursors), after which the non-covalent complex A•B forms selectively in high yield. Form a supramolecular chemistry perspective, in situ capture is more demanding than pre-assembly because it absolutely requires both Ka and kon to be very high. That is, non-covalent complex formation has to be trongly thermodynamically and kinetically favoured, even when the concentrations of A and B are low and there is a high abundance of species that compete for binding. This latter point is a major challenge when using biological media, which are of high ionic strength and contain many competing small molecules and serum proteins that can lower Ka.

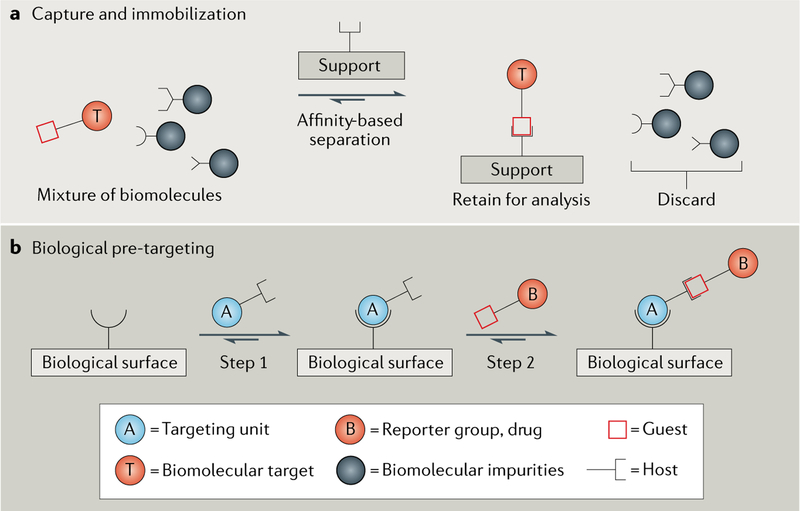

In situ capture is a process that is central to two distinctive experimental procedures. The first procedure, selective capture and immobilization of a biomolecular target, is principally a two-step process (FIG. 3a). The first step is to selectively tag a biomolecular target of interest with a guest molecule, and the second step is to use affinity separation methods based on non-covalent click chemistry to capture and immobilize the tagged biomolecule for subsequent analysis. A common version of this procedure is a ‘pulldown’ assay, in which one first biotinylates a biomolecular target and uses solid-supported (strept) avidin to capture and isolate the target from the mixture15. Another popular version uses immobilized Ni-NTA complexes to capture and immobilize His-tagged proteins21. More recently, other types of non-covalent click chemistry have been developed using immobilized cucurbit[7]uril46 and pillar[5] arene47 to capture and separate cellular proteins that have been tagged with the appropriate complementary guests48. The second general procedure that uses non-covalent click chemistry for in situ capture is a multistep imaging procedure known as biological pre-targeting9 (FIG. 3b). This technique is used to solve a conundrum that arises in nuclear imaging or radionuclide therapy of cancer in living subjects. Certain molecular targeting agents, such as antibodies, have long blood clearance times that prohibit the use of short-lived radionuclides that do not survive the lengthy, pre-scan waiting period that is needed to ensure sufficient tumour accumulation and high target-to-background ratio. Pre-targeting circumvents this problem by splitting the imaging procedure into two distinct steps. The first step is to dose the subject with a multifunctional molecular probe that has selective affinity for the target tumour (biological pre-targeting). It is not a problem if a long waiting period is required for extensive tumour accumulation and clearance of unbound probe from the bloodstream because the pre-targeted probe is not yet radiolabelled. The second step is to inject a fast-clearing radioactive (‘hot’) agent that is rapidly captured by the probe that has localized at the tumour, thus enabling nuclear imaging using an agent that features a short-lived radionuclide. The step involving the hot agent can be performed using covalent click chemistry, but a drawback with this approach is that the bimolecular covalent click reactions are slow at the very low probe concentrations present in the cancerous tissue within a living subject9. Therefore, non-covalent click chemistry has been investigated as a way to increase the rate and extent of radionuclide capture at the tumour target. To date, the non-covalent systems that have been tried include biotin–(strept)avidin49, oligonucleotide hybridization31,50, cucurbit[7]uril–adamantylammonium51 and multivalent β-cyclodextrin–adamantylcarboxamide52.

Fig. 3 |. In situ capture using non-covalent click chemistry.

There are two distinctive experimental approaches that make use of non-covalent click reactions for in situ capture, and both approaches can involve any of the complementary host and guest binding partners described in FIG. 1 and TABLE 1. a | Capture and immobilization is a two-step process in which one first tags a biomolecular target of interest with a guest molecule and then uses affinity separation based on non-covalent click chemistry to capture and immobilize the tagged biomolecule. b | Biological pre-targeting is a multistep procedure that is well suited for imaging cancerous tissue using radionuclides. First, the subject is dosed with a multifunctional molecular probe that has a targeting unit with selective affinity for the target tumour (biological surface). After waiting for the probe to accumulate at the tumour and excess probe to be cleared from the bloodstream, a subsequent dose introduces a fast-clearing radioactive agent that is rapidly captured at the tumour by the pre-targeted probe.

Non-covalent click chemistry has also been used as a pre-targeting strategy to label biological targets within a cell culture. Recent studies have employed cucurbit[7] uril–adamantylammonium to achieve the pre-targeted, two-step labelling of intracellular and cell surface targets with fluorescent dyes that enabled epifluorescence and super-resolution fluorescence microscopy53,54. A different approach involved the multivalent association of adamantylcarboxamide-containing guest molecules and a polymer containing multiple copies of a β-cyclodextrin-derived host to label cell surfaces for subsequent fluorescence microscopy55. It is important to emphasize that using a different host can require a different supramolecular design. For example, the Ka for a cucurbit[7]uril–adamantylammonium pair is ~1012 M−1 in buffered solution56, which means that one component is very effectively captured by the other in biological media. By contrast, the Ka for a β-cyclodextrin–adamantylcarboxamide pair is ~105 M−1, which is not high enough for efficient capture. This problem is overcome by using a multivalent version of the β-cyclodextrin–adamantylcarboxamide capture system that has much higher affinity57.

Conclusion and perspective

The emergence of covalent click chemistry over the past two decades has greatly facilitated research in biomedicine, advanced materials and nanotechnology. Similarly, non-covalent click chemistry is increasingly making an impact as a distinct and complementary method of molecular conjugation. The development of new host–guest pairs with outstanding chemical and supramolecular properties, along with structural refinement of currently known host–guest pairs, will enable a multitude of new pre-assembly and in situ capture applications.

Very recently, chemists have begun to consider the synergistic outcomes achievable by using both covalent and non-covalent click chemistry for molecular conjugation. The simplest way to combine the two conjugation methods is to deploy them as independent but orthogonal attachment processes57. The concept has been applied to decorating a nanoparticle with targeting units and fluorescent reporters using azide–strained alkyne as a covalent click pair and cucurbit[7]uril–adamantylammonium as an orthogonal non-covalent click pair58. This mixed covalent and non-covalent conjugation approach to surface functionalization will most likely be broadly used as an efficient means to prepare, potentially in a combinatorial fashion, multifunctional probes and coated surfaces for biomedicine and nanotechnology.

A different way to combine covalent and non-covalent click chemistry is a hybrid molecular conjugation process that exploits the most attractive properties of the separate methods. A favourable feature of covalent click chemistry is the high strength of covalent conjugate bonds but a weakness is the relative slowness by which these bonds form. By contrast, the defining properties of non-covalent click chemistry are the opposite: non-covalent complexes can form very quickly but often have only moderate stability. Merging the strengths of both processes would give bifunctional reactive probes that first undergo rapid non-covalent association with the target site. This event induces a proximity effect that accelerates a subsequent covalent bond formation step. Such a hybrid conjugation method has been demonstrated many times using metal coordination as the preliminary non-covalent association step to enhance concomitant covalent labelling of a protein19 or a liposome surface59. Hybrid conjugation has also been used in a different context for enhanced covalent labelling of glycosylated proteins on the surface of living cells60. It seems very likely that hybrid forms of covalent and non-covalent click chemistry that exploit proximity enhancement will soon emerge as a new molecular conjugation paradigm of utility to materials science, drug discovery and biomedical research61.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for a grant from the US National Institutes of Health (GM059078) and AD&T Berry Family Foundation fellowship from the University of Notre Dame.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Janaratne TK, Okach L, Brock A & Lesley SA Solubilization of native integral membrane proteins in aqueous buffer by noncovalent chelation with monomethoxy polyethylene glycol (mPEG) polymers. Bioconjug. Chem 22, 1513–1518 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolb HC, Finn MG & Sharpless KB Click chemistry: diverse chemical function from a few good reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 40, 2004–2021 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu Z, Wang L, Fang F, Fu Y & Yin Z A review on colloidal self-assembly and their applications. Curr. Nanosci 12, 725–746 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plutschack MB, Pieber B, Gilmore K & Seeberger PH The hitchhiker’s guide to flow chemistry. Chem. Rev 117, 11796–11893 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu K et al. Molecular imaging probe development using microfluidics. Curr. Org. Synth 8, 473–487 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng Z, Al Zaki A, Hui JZ, Muzykantov VR & Tsourkas A Multifunctional nanoparticles: cost versus benefit of adding targeting and imaging capabilities. Science 338, 903–910 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marqués-Gallego P & de Kroon AIPM Ligation strategies for targeting liposomal nanocarriers. Biomed Res. Int 2014, 129458 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abd Ellah NH & Abouelmagd SA Surface functionalization of polymeric nanoparticles for tumor drug delivery: approaches and challenges. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv 14, 201–214 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stéen EJL et al. Pretargeting in nuclear imaging and radionuclide therapy: improving efficacy of theranostics and nanomedicines. Biomaterials 179, 209–245 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoon HY, Koo H, Kim K & Kwon IC Molecular imaging based on metabolic glycoengineering and bioorthogonal click chemistry. Biomaterials 132, 28–36 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossin R & Robillard MS Pretargeted imaging using bioorthogonal chemistry in mice. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 21, 161–169 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patterson DM, Nazarova LA & Prescher JA Finding the right (bioorthogonal) chemistry. ACS Chem. Biol 9, 592–605 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freidel C, Kaloyanova S & Peneva K Chemical tags for site-specific fluorescent labeling of biomolecules. Amino Acids 48, 1357–1372 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rashidian M, Dozier JK & Distefano MD Enzymatic labeling of proteins: techniques and approaches. Bioconjug. Chem 24, 1277–1294 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dundas CM, Demonte D & Park S Streptavidin–biotin technology: improvements and innovations in chemical and biological applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 97, 9343–9353 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain A & Cheng K The principles and applications of avidin-based nanoparticles in drug delivery and diagnosis. J. Control. Release 245, 27–40 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller LW, Cai Y, Sheetz MP & Cornish VW In vivo protein labeling with trimethoprim conjugates: a flexible chemical tag. Nat. Methods 2, 255–257 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu S & Hu H-Y Fluorogen-activating proteins: beyond classical fluorescent proteins. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 8, 339–348 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uchinomiya S, Ojida A & Hamachi I Peptide tag/probe pairs based on the coordination chemistry for protein labeling. Inorg. Chem 53, 1816–1823 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gatterdam K, Joest EF, Gatterdam V & Tampé R Scaffold design of trivalent chelator heads dictates high-affinity and stable His-tagged protein labeling in vitro and in cellulo. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 57, 12395–12399 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.You C & Piehler J Multivalent chelators for spatially and temporally controlled protein functionalization. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 406, 3345–3357 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouhedda F, Autour A & Ryckelynck M Light-up RNA aptamers and their cognate fluorogens: from their development to their applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci 19, 44 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H et al. Assembling DNA through affinity binding to achieve ultrasensitive protein detection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 52, 10698–10705 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodell CB, Mealy JE & Burdick JA Supramolecular guest−host interactions for the preparation of biomedical materials. Bioconjug. Chem 26, 2279–2289 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Li L-L, Fan Y.-s & Wang H Host–guest supramolecular nanosystems for cancer diagnostics and therapeutics. Adv. Mater 25, (3888–3898 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu W, Samanta SK, Smith BD & Isaacs L Synthetic mimics of biotin/(strept)avidin. Chem. Soc. Rev 46, 2391–2403 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peck EM et al. Pre-assembly of near-infrared fluorescent multivalent molecular probes for biological imaging. Bioconjug. Chem 27, 1400–1410 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw S et al. Non-covalently pre-assembled high-performance near-infrared fluorescent molecular probes for cancer imaging. Chem. Eur. J 24, 13821–13829 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Dun S, Ottmann C, Milroy L-G & Brunsveld L Supramolecular chemistry targeting proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139, 13960–13968 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webber MJ et al. Supramolecular PEGylation of biopharmaceuticals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 14189–14194 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patra M, Zarschler K, Pietzsch H-J, Stephan H & Gasser G New insights into the pretargeting approach to image and treat tumours. Chem. Soc. Rev 45, 6415–6431 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim TH et al. Mix to validate: a facile, reversible pegylation for fast screening of potential therapeutic proteins in vivo. Agnew. Chem. Int. Ed 52, 6880–6884 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu X, Sun J & Gao W Site-selective protein modification with polymers for advanced biomedical applications. Biomaterials 178, 413–434 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mantooth SM, Munoz-Robles BG & Webber MJ Dynamic hydrogels from host–guest supramolecular interactions. Macromol. Biosci 19, 1800281 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Y & Hsu S.-h. Synthesis and biomedical applications of self-healing hydrogels. Front. Chem 6, 449 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diba M et al. Self-healing biomaterials: from molecular concepts to clinical applications. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 5, 1800118 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun C et al. Polymeric nanomedicine with “Lego” surface allowing modular functionalization and drug encapsulation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 25090–25098 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim S et al. Cucurbit[6]uril-based polymer nanocapsules as a non-covalent and modular bioimaging platform for multimodal: in vivo imaging. Mater. Horiz 4, 450–455 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang S et al. Precise supramolecular control of surface coverage densities on polymer micro- and nanoparticles. Chem. Sci 9, 8575–8581 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou Z, Han Z & Lu ZR A targeted nanoglobular contrast agent from host-guest self-assembly for MR cancer molecular imaging. Biomaterials 85, 168–179 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Q-L et al. Supramolecular nanosystem based on pillararene-capped CuS nanoparticles for targeted chemo-photothermal therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 29314–29324 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Y-X, Zhang Y-M, Wang Y-L & Liu Y Multifunctional vehicle of amphiphilic calix[4]arene mediated by liposome. Chem. Mater 27, 2848–2854 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hou C, Huang Z, Fang Y & Liu J Construction of protein assemblies by host–guest interactions with cucurbiturils. Org. Biomol. Chem 15, 4272–4281 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y, Yang H, Wang Z & Zhang X Cucurbit[8]uril-based supramolecular polymers. Chem. Asian J 8, 1626–1632 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samanta SK, Moncelet D, Briken V & Isaacs L Metal–organic polyhedron capped with cucurbit[8]uril delivers doxorubicin to cancer cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 14488–14496 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park KM, Murray J & Kim K Ultrastable artificial binding pairs as a supramolecular latching system: a next generation chemical tool for proteomics. Acc. Chem. Res 50, 644–646 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu H et al. Pillararene-based host–guest recognition facilitated magnetic separation and enrichment of cell membrane proteins. Mater. Chem. Front 2, 1475–1480 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Finbloom JA & Francis MB Supramolecular strategies for protein immobilization and modification. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 46, 91–98 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li G-P, Zhang H, Zhu C-M, Zhang J & Jiang X-F Avidin–biotin system pretargeting radioimmunoimaging and radioimmunotherapy and its application in mouse model of human colon carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol 11, 6288–6294 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schubert M et al. Novel tumor pretargeting system based on complementary l-configured oligonucleotides. Bioconjug. Chem 28, 1176–1188 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strebl MG, Yang J, Isaacs L & Hooker JM Adamantane/cucurbituril: a potential pretargeted imaging strategy in immuno-PET. Mol. Imaging 17, 1536012118799838 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spa SJ et al. A supramolecular approach for liver radioembolization. Theranostics 8, 2377–2386 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim KL et al. Supramolecular latching system based on ultrastable synthetic binding pairs as versatile tools for protein imaging. Nat. Commun 9, 1712 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sasmal R et al. Synthetic host–guest assembly in cells and tissues: fast, stable, and selective bioorthogonal imaging via molecular recognition. Anal. Chem 90, 11305–11314 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rood MTM et al. Obtaining control of cell surface functionalizations via pre-targeting and supramolecular host guest interactions. Sci. Rep 7, 39908 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu S et al. The cucurbit[n]uril family: prime components for self-sorting systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc 127, 15959–15967 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Welling MM et al. In vivo stability of supramolecular host–guest complexes monitored by dual-isotope multiplexing in a pre-targeting model of experimental liver radioembolization. J. Control. Release 293, 126–134 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samanta SK, Moncelet D, Vinciguerra B, Briken V & Isaacs L Metal organic polyhedra: a click-and-clack approach toward targeted delivery. Helv. Chim. Acta 101, e1800057 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bak M, Jølck RI, Eliasen R & Andresen TL Affinity induced surface functionalization of liposomes using Cu-free click chemistry. Bioconjug. Chem 27, 1673–1680 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Robinson PV, de Almeida-Escobedo G, de Groot AE, McKechnie JL & Bertozzi CR Live-cell labeling of specific protein glycoforms by proximity-enhanced bioorthogonal ligation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 10452–10455 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Long MJC, Poganik JR & Aye Y On-demand targeting: investigating biology with proximity-directed chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 3610–3622 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cañeque T, Müller S & Rodriguez R Visualizing biologically active small molecules in cells using click chemistry. Nat. Rev. Chem 2, 202–215 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xi W, Scott TF, Kloxin CJ & Bowman CN Click chemistry in materials science. Adv. Funct. Mater 24, 2572–2590 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leppiniemi J et al. Bifunctional avidin with covalently modifiable ligand binding site. PLOS ONE 6, e16576 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saunders MJ et al. Fluorogen activating proteins in flow cytometry for the study of surface molecules and receptors. Methods 57, 308–317 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ouellet J RNA fluorescence with light-up aptamers. Front. Chem 4, 29 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang JX et al. Predicting DNA hybridization kinetics from sequence. Nat. Chem 10, 91–98 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Assaf KI & Nau WM Cucurbiturils: from synthesis to high-affinity binding and catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev 44, 394–418 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Murray J, Kim K, Ogoshi T, Yao W & Gibb BC The aqueous supramolecular chemistry of cucurbit[n] urils, pillar[n]arenes and deep-cavity cavitands. Chem. Soc. Rev 46, 2479–2496 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu W, Peck EM, Hendzel KD & Smith BD Sensitive structural control of macrocycle threading by a fluorescent squaraine dye flanked by polymer chains. Org. Lett 17, 5268–5271 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gómez-Durán CFA, Liu W, Betancourt-Mendiola ML & Smith BD Structural control of kinetics for macrocycle threading by fluorescent squaraine dye in water. J. Org. Chem 82, 8334–8341 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ogoshi T, Yamagishi T. a. & Nakamoto Y Pillar-shaped macrocyclic hosts pillar[n]arenes: new key players for supramolecular chemistry. Chem. Rev 116, 7937–8002 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sadrerafi K, Moore EE & Lee MW Association constant of β-cyclodextrin with carboranes, adamantane, and their derivatives using displacement binding technique. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem 83, 159–166 (2015). [Google Scholar]