Antibody tests for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, are widely available. This living review summarizes the evidence on the prevalence, levels, and durability of detectable antibodies after SARS-CoV-2 infection and whether antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 confer protective immunity. The review will be updated as more evidence becomes available.

Abstract

Background:

The clinical significance of the antibody response after SARS-CoV-2 infection remains unclear.

Purpose:

To synthesize evidence on the prevalence, levels, and durability of detectable antibodies after SARS-CoV-2 infection and whether antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 confer natural immunity.

Data Sources:

MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov, World Health Organization global literature database, and Covid19reviews.org from 1 January through 15 December 2020, limited to peer-reviewed publications available in English.

Study Selection:

Primary studies characterizing the prevalence, levels, and duration of antibodies in adults with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR); reinfection incidence; and unintended consequences of antibody testing.

Data Extraction:

Two investigators sequentially extracted study data and rated quality.

Data Synthesis:

Moderate-strength evidence suggests that most adults develop detectable levels of IgM and IgG antibodies after infection with SARS-CoV-2 and that IgG levels peak approximately 25 days after symptom onset and may remain detectable for at least 120 days. Moderate-strength evidence suggests that IgM levels peak at approximately 20 days and then decline. Low-strength evidence suggests that most adults generate neutralizing antibodies, which may persist for several months like IgG. Low-strength evidence also suggests that older age, greater disease severity, and presence of symptoms may be associated with higher antibody levels. Some adults do not develop antibodies after SARS-CoV-2 infection for reasons that are unclear.

Limitation:

Most studies were small and had methodological limitations; studies used immunoassays of variable accuracy.

Conclusion:

Most adults with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by RT-PCR develop antibodies. Levels of IgM peak early in the disease course and then decline, whereas IgG peaks later and may remain detectable for at least 120 days.

Primary Funding Source:

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (PROSPERO: CRD42020207098)

The association of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 with immunity to COVID-19 (which SARS-CoV-2 causes) remains unclear. Of key importance is whether having antibodies after recovery from COVID-19 is associated with lower risk for reinfection or less severe disease if reinfection occurs. Understanding the implications of having antibodies is essential to guiding individual patient care decisions as well as public health interventions, such as testing and vaccination.

Although antibody presence is popularly equated with immunity, the actual relationship between antibodies and immunity varies by viral disease. For example, antibodies develop in response to seasonal human coronaviruses that cause the common cold but do not confer lifelong immunity, perhaps because waning antibody levels or viral mutations render preexisting antibodies ineffective, as with seasonal influenza (1, 2). Properties of the infecting virus, the “dose” and route of infection, and such host factors as age may also influence the antibody response and immunity (3). Case reports of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection, although rare, have generated speculation about the role of antibodies in the risk for and severity of reinfection but have not shown clear trends (4).

Numerous immunoassays have been developed to detect SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. However, a standard approach to testing in terms of antibody subtypes and timing has not yet been determined, and guidelines from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend against making individual health care decisions based on antibody test results alone (5). Immunoassays detect antibody subtypes (IgM, IgG, or IgA) or composite antibody responses (pan-Ig) and may report results qualitatively or quantitatively. Most immunoassays detect antibodies to the viral spike protein, receptor-binding domain (which is part of the spike protein), or nucleocapsid protein (5). Neutralizing antibodies, which most commonly act against the receptor-binding domain region of the viral spike protein, bind to the virus and prevent infection and are therefore of particular interest in determining whether antibodies confer protective immunity (6).

We aimed to synthesize evidence on the following 4 topics: 1) prevalence, levels, and durability of antibodies developed in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection; 2) variation by patient characteristics, disease severity, and immunoassay used; 3) whether and for how long antibodies confer natural immunity; and 4) any unintended consequences of antibody testing. This article is based on a rapid systematic review done by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Effective Health Care Program in coordination with the American College of Physicians (ACP). This review helped inform the development of ACP Practice Points on the role of antibody testing in COVID-19.

Methods

We followed standard systematic review methods and reporting guidelines and registered the protocol for this review at PROSPERO on 15 October 2020 (CRD42020207098) (7, 8). To accommodate a rapid review timeline, we used sequential instead of independent dual review processes for study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment. A complete description of our methods can also be found on the AHRQ website (9). Key questions (detailed in the ACP Practice Points) were developed by ACP and AHRQ staff and revised with input from the review authors (I.A.-J., K.M., and M.H.).

Data Sources and Searches

A research librarian (R.A.P.) searched for English-language articles in the following databases: Ovid MEDLINE ALL, Elsevier Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, ClinicalTrials.gov, the World Health Organization global literature database, and COVID19reviews.org. The original database search was from 1 January to 5 August 2020. Later hand-searching of relevant citations showed gaps in the search strategies, which were revised for an updated search that captured citations from 1 January to 15 December 2020 (see the Supplement for the search strategy). We limited our search to peer-reviewed publications and excluded preprint (non–peer-reviewed) studies.

Study Selection

We included studies of adults (aged ≥18 years) with SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosed via reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) who had serologic testing when the study addressed at least 1 of our 4 aims and included an outcome of interest (Supplement Table 2 provides inclusion and exclusion criteria). We included immunoassay validation studies identified in our first round of searching but subsequently focused on studies that directly addressed our aims. Although we retained immunoassay validation studies to illustrate what they contributed to the evidence base, they provided indirect and less reliable evidence about antibody dynamics given that seroprevalence had to be extrapolated from sensitivity and specificity estimates. Using a sequential process (involving I.A.-J., K.M., C.A., J.A., and E.G.), 1 reviewer screened abstracts for inclusion and reviewed full texts and a second reviewer verified decisions. Disagreements were resolved through consensus.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Using a sequential process, 1 reviewer extracted study characteristics and outcomes (I.A.-J., K.M., C.A., J.A., or E.G.) and a second reviewer verified accuracy (I.A.-J., K.M., C.A., J.A., or E.G.). We intended to use the National Institutes of Health criteria to describe COVID-19 severity as mild, moderate, or severe, but we instead reported disease severity as defined in individual studies because of the wide range of criteria used (10). Two reviewers (K.M. and E.G.) sequentially assessed study quality (risk of bias) using adapted criteria from one of the following: the Joanna Briggs Institute's critical appraisal checklist for prevalence studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort and cross-sectional studies, or the QUADAS-2 (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2) tool for immunoassay validation studies (11–13).

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We synthesized evidence qualitatively and did not do meta-analyses because of variability in study populations, immunoassays used, test timing, and outcomes. Two reviewers (I.A.-J. and K.M.) rated the overall strength of evidence using criteria that assessed study risk of bias, how directly the populations and outcomes of interest were evaluated, precision of effect estimates, and consistency of results across studies. We focused strength-of-evidence assessments regarding antibody prevalence on results from seroprevalence, cross-sectional, and cohort studies rather than results from immunoassay validation studies (which provide less reliable estimates for the reasons already discussed). For the remaining outcomes of interest, we incorporated results from all studies into strength-of-evidence assessments.

Literature Surveillance

We plan monthly literature surveillance using our most recent search strategy and methods as described in the preceding sections. New evidence that does not substantively change our findings will be summarized quarterly; a major update will be made when new evidence changes the nature or strength of the conclusions. We anticipate maintaining this living review through December 2021, adjusting the timeline as needed depending on when we can conclusively answer the review's key questions.

Role of the Funding Source

Staff at AHRQ contributed to the development of the review aims and scope but had no role in the selection, assessment, or synthesis of evidence; AHRQ was not involved in the decision to submit this article for publication.

Results

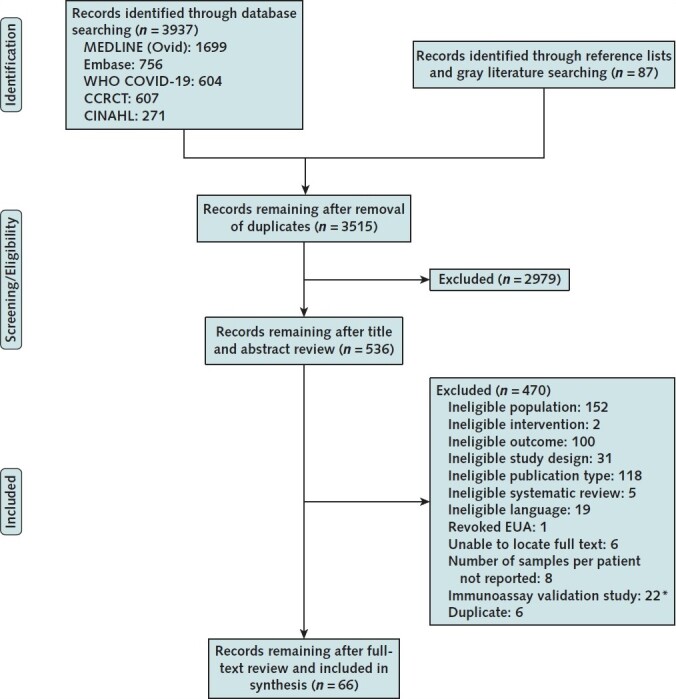

The literature flow chart (Figure 1) summarizes the results of search and study selection processes (7). We included 66 observational studies (total n = 16 525): 4 studies estimated population seroprevalence and included a subpopulation with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by RT-PCR, 45 were cross-sectional or cohort studies characterizing the antibody response (that is, antibody types, levels, and durability), and 17 validated the diagnostic performance of 1 or more immunoassays (14–45-46–77-78, 79). Supplement Table 3 shows study characteristics.

Figure 1. Evidence search and selection.

CCRCT = Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; EUA = emergency use authorization; WHO = World Health Organization.

* Exclusion applied to update search only.

About half of the studies (52%) included fewer than 100 participants with SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosed via RT-PCR; sample sizes ranged from 29 to 2547 persons (median, 98 persons). Most studies (64%) included participants with a range of disease severity and symptoms. Nine studies (14%) included only participants with asymptomatic or mild disease; 10 (15%) included only participants with moderate, severe, or critical disease; and 5 (7%) did not report disease severity. Twenty-five studies (38%) were done in China, 22 (33%) in Europe, and 12 (18%) in the United States or Canada; the remaining 7 studies (11%) were from other countries (Korea, Japan, Thailand, Singapore, India, or Brazil). Thirty-four studies (51%) were done in hospital settings, 15 (23%) in outpatient settings, and 15 (23%) in a mix of inpatient and outpatient settings; 2 studies (3%) did not report setting. Most studies evaluated antibody prevalence or levels within the first 28 days from symptom onset or RT-PCR diagnosis. A longitudinal prospective study of neutralizing antibody titers among 32 recovered adults collected samples up to 152 days after symptom onset, the longest follow-up among included studies (23). With a few exceptions, most other studies followed participants for less than 100 days (20, 29, 50, 53, 63).

Studies measured IgM and IgG most frequently, followed by neutralizing antibodies and IgA. Studies used various immunoassays, including commercially available immunoassays and those developed “in-house” by academic and research institutions. Supplement Table 4 presents immunoassay manufacturer information, performance characteristics, and authorization status in the United States and Europe (80–82).

Overall, 15 studies (23%) had low risk of bias, 16 (24%) had high risk of bias, and reporting gaps made risk of bias for the remaining 35 (53%) unclear. Supplement Table 5 presents risk-of-bias assessments for each study, as well as the criteria used in assessments. Three of the 4 seroprevalence studies had low risk of bias (28, 29, 35). The exception was a study of U.S. Navy service members aboard the U.S.S. Theodore Roosevelt carrier during a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak; this study had high risk of bias due to low participation (27% of eligible participants were included in the sample), differences in the age and racial distribution of participants compared with nonparticipants, and use of participant self-report for RT-PCR and serology test results (49). Among cross-sectional and cohort studies with high risk of bias, the most serious methodological issues were unclear patient selection methods (that is, whether selection was random or consecutive) and lack of adjustment for confounding factors, like age, that could influence subgroup comparisons (16, 18, 24, 40, 42, 45, 51, 54, 57, 66, 68, 74, 76, 77, 79). In the immunoassay validation studies, inadequate reporting of patient selection methods and unclear or inconsistent criteria for interpreting immunoassay results meant that we could not rule out high risk of bias and limited the clinical applicability of results (14, 15, 22, 25, 26, 32, 33, 37, 43, 44, 48, 56, 64, 65, 69, 71, 72).

IgM Prevalence, Levels, and Duration

Evidence suggests that most adults with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by RT-PCR (80%) develop IgM antibodies. We derived this estimate from results of 21 seroprevalence, cross-sectional, and cohort studies (n = 6073; range, 32 to 1850 participants) that reported IgM prevalence at or around 20 days after symptom onset or RT-PCR diagnosis (Table 1) (24, 27, 29–31, 35, 36, 38, 41, 45, 47, 51, 54, 57, 59, 60, 74–78).

Table 1. Antibody Prevalence.

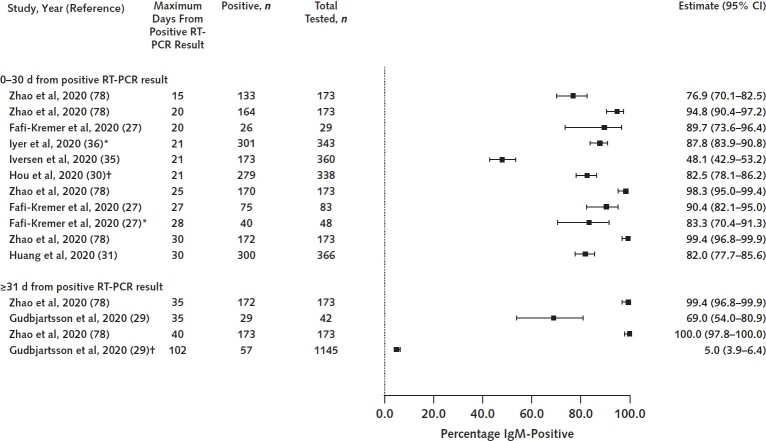

We chose to examine IgM prevalence at or around 20 days because this is when IgM levels are estimated to peak on the basis of a subset of studies describing trends in IgM levels over time (Table 2). Results from studies that trended IgM levels over time also suggest that IgM is first detected at a mean of 7 days and starts to decline at 27 days. Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of IgM prevalence estimates.

Table 2. Antibody Kinetics*.

Figure 2. IgM prevalence at 0–30 d and after 30 d.

Studies represented had well-characterized patient populations and settings, measured antibodies using validated immunoassays, and lacked serious methodological problems. RT-PCR = reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

* Number of days from positive result on RT-PCR is minimum of unbounded range (e.g., >20 d).

† Study provided mean or median number of days from positive result on RT-PCR.

We have moderate confidence in findings about IgM peak prevalence and trends in IgM levels over time. Although some studies had serious methodological limitations and nearly all used different immunoassays and collected samples at different frequencies and time points, findings that most individuals develop IgM and that these levels decline over time are consistent across most studies.

IgG Prevalence, Levels, and Duration

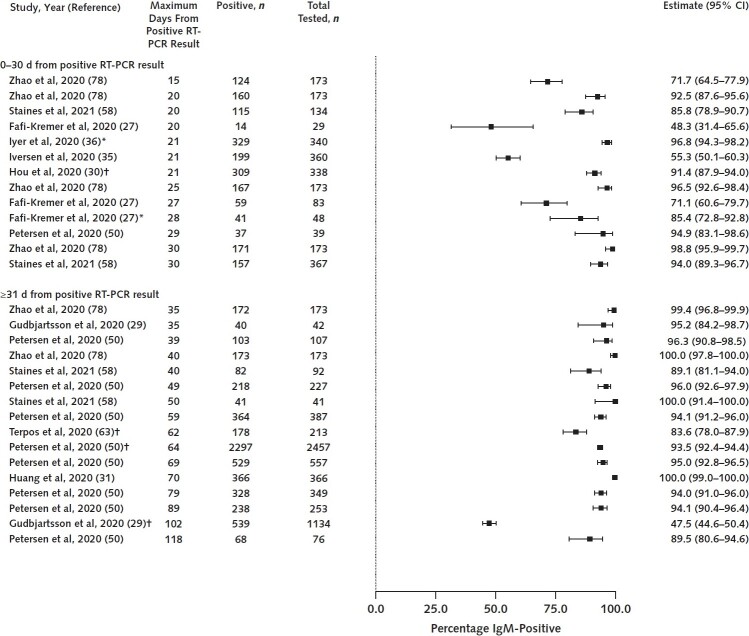

Evidence suggests that nearly all adults with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by RT-PCR (95%) develop IgG antibodies. In the same way that we derived an overall estimate for IgM prevalence, we derived an estimate for IgG based on results from 24 seroprevalence, cross-sectional, and cohort studies (n = 9136; range, 32 to 2547 participants) that reported IgG prevalence at or around 25 days, when IgG levels are estimated to peak (Table 1) (18, 24, 27, 29, 30, 35, 36, 38, 41, 45, 47, 50, 51, 54, 55, 57, 60, 61, 67, 74–78). Studies that trended IgG levels over time also found that IgG is first detected at a mean of 12 days (slightly later than IgM), peaks at 25 days, then plateaus and may decline after 60 days (Table 2). Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of IgG prevalence estimates. We have moderate confidence in findings about IgG peak prevalence and trends in IgG levels over time. Findings are consistent even though studies were done in different regions and settings and had a range of quality.

Figure 3. IgG prevalence at 0–30 d and after 30 d.

Studies represented had well-characterized patient populations and settings, measured antibodies using validated immunoassays, and lacked serious methodological problems. RT-PCR = reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

* Number of days from positive result on RT-PCR is minimum of unbounded range (e.g., >20 d).

† Study provided mean or median number of days from positive result on RT-PCR.

IgA Prevalence, Levels, and Duration

Only 5 cross-sectional and cohort studies (n = 747; range, 40 to 343 participants) evaluated IgA prevalence, and they varied widely in test timing. These studies found that IgA prevalence ranged from 75% to 89% (median, 83%) when measured from days 2 to 122 after symptom onset or RT-PCR diagnosis (Table 1) (18, 21, 36, 53, 54). Like IgG, IgA may remain detectable for months past SARS-CoV-2 infection. A large seroprevalence study done in Iceland found that IgA antibodies peaked within a month of SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis and then declined but remained detectable for at least 100 days (29). Two other studies that trended IgA levels over time reported similar findings (21, 54). We have low confidence in these findings given the smaller number of studies (with small sample sizes) and estimates for IgA prevalence and levels at different time points.

Neutralizing Antibody Prevalence, Levels, and Duration

Evidence from 8 cross-sectional and cohort studies (n = 979; range, 29 to 567 participants) suggests that almost all individuals (99%) develop neutralizing antibodies (Table 1) (23, 27, 36, 38, 39, 61, 68, 70). Findings about the durability of neutralizing antibodies varied. In some studies, neutralizing antibody levels declined after the acute phase of illness; in others, levels plateaued and remained detectable for several months (Table 2) (23, 39, 54). Several studies found that neutralizing activity is correlated with the presence of IgG antibodies to the viral spike protein, nucleocapsid protein, and receptor-binding domain (20, 36, 39). We have low confidence in findings regarding neutralizing antibody prevalence and changes in levels over time. Although results are consistent, studies of neutralizing antibody activity were small, used different neutralization tests, and collected samples at different frequencies and time points, limiting our ability to draw stronger conclusions.

Variation in the SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Response

We examined whether antibody prevalence or levels varied significantly by patient factors like age, sex, race/ethnicity, and comorbid conditions; disease factors like severity and the presence or absence of symptoms; and the type of immunoassay used. We found little correlation between these factors and antibody responses, although weak evidence suggests that older age, greater disease severity, and the presence of symptoms may be associated with higher antibody levels. We have low confidence in these findings given the limitations of the evidence base, including small study sizes, inconsistent adjustment for confounding factors, and lack of precision in estimates. Details on these analyses can be found in the full AHRQ report.

Lack of an Antibody Response

Nearly all studies found that a certain proportion of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by RT-PCR did not have detectable antibodies. For example, in an Icelandic seroprevalence study in which 489 recovered patients had antibody testing at 2 time points (once ≥3 weeks after diagnosis and again ≥1 month after that), 19 (4%) had negative results for 2 pan-Ig immunoassays (29). Few studies evaluated whether patient factors and illness severity were associated with this finding. An exception is a U.S. study of 2547 frontline health care workers and first responders, which found that about 6% of participants remained seronegative 14 to 90 days after symptom onset (50). This result was strongly associated with disease severity and presence of symptoms. Although 11% of 308 asymptomatic patients did not develop antibodies, none of the 79 patients hospitalized for COVID-19 were seronegative.

Role of Antibodies in Immunity Against Reinfection

Studies in this review primarily aimed to estimate seroprevalence and characterize the antibody response after SARS-CoV-2 infection and did not directly evaluate the association between antibodies and immunity. A retrospective study of 47 hospitalized patients in China with moderate to severe COVID-19 mentions a potential case of reinfection in 1 patient during the “convalescence stage” of the disease (77). Of note, the patient did not have detectable antibodies (either IgM or IgG) at follow-up 4 weeks after discharge, but the study does not provide more detail or describe how reinfection was determined. Otherwise, we did not identify any studies of persons with SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosed via RT-PCR that directly linked the presence or absence of antibodies with incidence of reinfection. A Danish study is investigating immunity by following participants positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies at 1, 5, 10, and 20 years, but so far it has reported only initial antibody test results (35). Population seroprevalence studies, such as the Icelandic study discussed in the previous section, could provide insight into reinfection risk if study periods were extended and incidence of reinfection compared among participants with and without antibodies.

We note that, in several recent studies of adults with known positive or negative SARS-CoV-2 serologies, antibody presence is associated with protective immunity. A prospective study following 12 541 health care workers in the United Kingdom for up to 31 weeks found that anti-spike IgG seropositivity at baseline was associated with lower risk for subsequent positive results on RT-PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 (223 of 11 364 vs. 2 of 1265; adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.11) (83, 84). Only 37% (466 of 1265) of the seropositive workers had a prior RT-PCR–confirmed infection. Two small retrospective studies also suggest that prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, as measured by positive antibody results, is associated with reduced risk for reinfection (85, 86). One of these studies described a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak among attendees and staff at a summer school retreat (85). Among 152 participants, 76% (n = 116) had confirmed or presumed SARS-CoV-2 infection, whereas none of the 24 persons who had documented seropositive results in the 3 months before the retreat developed symptoms. In another study, 3 participants who had positive neutralizing antibody results (and negative results on RT-PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2) before departing on a fishing vessel did not subsequently test positive for SARS-CoV-2 despite an outbreak affecting 85% (104 of 122) of the onboard population (86).

Unintended Consequences of SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Testing

Abandoning recommended safety practices, such as wearing masks and social distancing, is a potential unintended consequence of antibody testing. In a survey of 560 British health care workers, 15% of whom had a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by RT-PCR, 11% (n = 61) would view social distancing as less important and 31% (n = 175) would be “happier to visit friends and relatives” if they received a positive antibody test result (52). No studies have documented actual behavior change related to knowledge of antibody status.

Discussion

This rapid systematic review synthesizes currently available evidence (based on a literature search through 15 December 2020) on the prevalence of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after COVID-19 and whether antibodies confer natural immunity.

Moderate-strength evidence suggests that most adults with SARS-CoV-2 infection develop IgM and IgG antibodies. Moderate-strength evidence also suggests that IgM levels peak approximately 20 days into the disease course and then decline, whereas IgG peaks approximately 25 days after symptom onset for most patients and may remain detectable for at least 120 days. Low-strength evidence suggests that neutralizing antibody activity may also persist for several months. Low-strength evidence also suggests that antibody prevalence does not vary by age or sex but that older age and greater disease severity may be associated with higher antibody levels. Details regarding strength-of-evidence assessments for all outcomes are included in the ACP Practice Points and in Supplement Table 6.

Most studies to date have not been designed to evaluate whether the presence of antibodies among persons recovered from SARS-CoV-2 confers natural immunity, nor whether the absence of postinfection antibodies is clinically meaningful. Several studies are under way to help answer these questions, and the AHRQ Effective Health Care Program will update this report as new evidence becomes available.

The evidence base has several limitations. First, studies were mostly small, primarily included hospitalized patients with COVID-19, and were done mostly in China and Europe, potentially limiting applicability to other populations and settings. Second, the diagnostic accuracy of several immunoassays has not yet been validated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (the standard for emergency use authorization is different from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's typical review standard) (87). Some antibody tests may have low sensitivity, and false-positive results may occur because of cross-reactivity from past exposures to other coronaviruses. The degree to which false-negative or false-positive results affect prevalence estimates is unclear and was rarely commented on by study authors. Third, most studies did not distinguish active infection from persistently positive results on RT-PCR testing due to viral RNA shedding that does not represent active infection, a recently recognized phenomenon (88).

Limitations of our review methods include use of sequential rather than independent dual review for study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment. Given the large volume of studies and our rapid review timeline, we may have missed subgroup data if the information was in an online appendix or otherwise not prominently featured in the text. A second limitation is our exclusion of preprints (non–peer-reviewed publications). Online publication of studies before peer review is common in the era of COVID-19, and we may have excluded pertinent studies. Because this is a living review with ongoing literature surveillance, we will continue to monitor the evidence base for relevant preprint studies as they are published. Finally, our scope was limited to studies of adults with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by RT-PCR, and findings may not apply to those diagnosed clinically on the basis of other criteria (such as imaging findings) or those with subclinical disease who did not seek medical care.

Although this review focused on studies of antibodies, the immune system's response to infection also includes cell-mediated immunity (immunity dependent on the recognition of antigens by T cells). Studies designed to evaluate the roles of both antibody-mediated and cell-mediated immunity in preventing SARS-CoV-2 reinfection are under way. For example, a prospective cohort study funded by the National Institutes of Health is recruiting adults with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by RT-PCR or a history of exposure; the study will monitor serum markers of antibody and T-cell–mediated immunity over a 3-year period and evaluate incidence of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection over time (89). Selected in-progress studies are described in Supplement Table 7.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 16 March 2021.

References

- 1. Krammer F . The human antibody response to influenza A virus infection and vaccination. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:383-397. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0143-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Edridge AWD , Kaczorowska J , Hoste ACR , et al. Seasonal coronavirus protective immunity is short-lasting. Nat Med. 2020;26:1691-1693. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1083-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rouse BT , Sehrawat S . Immunity and immunopathology to viruses: what decides the outcome. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:514-26. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1038/nri2802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kim AY , Gandhi RT . Re-infection with SARS-CoV-2: what goes around may come back around. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidelines for COVID-19 antibody testing. 1 August 2020. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/resources/antibody-tests-guidelines.html on 25 January 2021.

- 6. Infectious Diseases Society of America. IDSA guidelines on the diagnosis of COVID-19: serologic testing. 18 August 2020. Accessed at www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-serology on 25 January 2021.

- 7. Moher D , Liberati A , Tetzlaff J , et al; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264-9, W64. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. AHRQ publication no. 10(14)-EHC063-EF. [PubMed]

- 9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Immunity after COVID-19: research protocol. 10 September 2020. Accessed at https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/immunity-after-covid/protocol on 25 January 2021.

- 10. National Institutes of Health. Clinical spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 infection. 17 December 2020. Accessed at www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/overview/clinical-spectrum on 25 January 2021.

- 11. Munn Z , Moola S , Lisy K , et al. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:147-53. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2019. Accessed at www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp on 25 August 2020.

- 13. Whiting PF , Rutjes AW , Westwood ME , et al; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529-36. [PMID: ]. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Andrey DO , Cohen P , Meyer B , et al. Head-to-head accuracy comparison of three commercial COVID-19 IgM/IgG serology rapid tests. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [PMID: ] doi: 10.3390/jcm9082369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Andrey DO , Cohen P , Meyer B , et al; Geneva Centre for Emerging Viral Diseases. Diagnostic accuracy of Augurix COVID-19 IgG serology rapid test. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020;50:e13357. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1111/eci.13357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bao Y , Ling Y , Chen YY , et al. Dynamic anti-spike protein antibody profiles in COVID-19 patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:540-548. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Blain H , Rolland Y , Tuaillon E , et al. Efficacy of a test-retest strategy in residents and health care personnel of a nursing home facing a COVID-19 outbreak. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:933-936. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bruni M , Cecatiello V , Diaz-Basabe A , et al. Persistence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in non-hospitalized COVID-19 convalescent health care workers. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [PMID: ] doi: 10.3390/jcm9103188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen Y , Ke Y , Liu X , et al. Clinical features and antibody response of patients from a COVID-19 treatment hospital in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. 2020. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1002/jmv.26617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen Y , Zuiani A , Fischinger S , et al. Quick COVID-19 healers sustain anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody production. Cell. 2020;183:1496-1507.e16. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chirathaworn C , Sripramote M , Chalongviriyalert P , et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding in recovered COVID-19 cases and the presence of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in recovered COVID-19 cases and close contacts, Thailand, April-June 2020. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0236905. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Choe JY , Kim JW , Kwon HH , et al. Diagnostic performance of immunochromatography assay for rapid detection of IgM and IgG in coronavirus disease 2019. J Med Virol. 2020;92:2567-2572. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1002/jmv.26060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crawford KHD , Dingens AS , Eguia R , et al. Dynamics of neutralizing antibody titers in the months after SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Infect Dis. 2020. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dave M, Poswal L, Bedi V, et al. Study of antibody-based rapid card test in COVID-19 patients admitted in a tertiary care COVID hospital in Southern Rajasthan. Journal, Indian Academy of Clinical Medicine. 2020;21:7-11.

- 25. de la Iglesia J, Fernández-Villa T, Fegeneda-Grandes JM, et al.. Concordance between two rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Semergen. 2020;46 Suppl 1:21-25. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.semerg.2020.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dellière S , Salmona M , Minier M , et al; Saint-Louis CORE (COvid REsearch) group. Evaluation of the COVID-19 IgG/IgM rapid test from Orient Gene Biotech. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1128/JCM.01233-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fafi-Kremer S , Bruel T , Madec Y , et al. Serologic responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection among hospital staff with mild disease in eastern France. EBioMedicine. 2020;59:102915. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Flannery DD , Gouma S , Dhudasia MB , et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence among parturient women in Philadelphia. Sci Immunol. 2020;5. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abd5709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gudbjartsson DF , Norddahl GL , Melsted P , et al. Humoral immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in Iceland. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1724-1734. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2026116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hou H , Wang T , Zhang B , et al. Detection of IgM and IgG antibodies in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Transl Immunology. 2020;9:e01136. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1002/cti2.1136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang M , Lu QB , Zhao H , et al. Temporal antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of coronavirus disease 2019. Cell Discov. 2020;6:64. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-00209-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Imai K , Tabata S , Ikeda M , et al. Clinical evaluation of an immunochromatographic IgM/IgG antibody assay and chest computed tomography for the diagnosis of COVID-19. J Clin Virol. 2020;128:104393. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Infantino M , Grossi V , Lari B , et al. Diagnostic accuracy of an automated chemiluminescent immunoassay for anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG antibodies: an Italian experience. J Med Virol. 2020;92:1671-1675. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1002/jmv.25932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Isho B , Abe KT , Zuo M , et al. Persistence of serum and saliva antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike antigens in COVID-19 patients. Sci Immunol. 2020;5. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abe5511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Iversen K , Bundgaard H , Hasselbalch RB , et al. Risk of COVID-19 in health-care workers in Denmark: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:1401-1408. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30589-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Iyer AS , Jones FK , Nodoushani A , et al. Persistence and decay of human antibody responses to the receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in COVID-19 patients. Sci Immunol. 2020;5. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abe0367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jääskeläinen AJ , Kekäläinen E , Kallio-Kokko H , et al. Evaluation of commercial and automated SARS-CoV-2 IgG and IgA ELISAs using coronavirus disease (COVID-19) patient samples. Euro Surveill. 2020;25. [PMID: ] doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.18.2000603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ko JH , Joo EJ , Park SJ , et al. Neutralizing antibody production in asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients, in comparison with pneumonic COVID-19 patients. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [PMID: ] doi: 10.3390/jcm9072268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Koblischke M , Traugott MT , Medits I , et al. Dynamics of CD4 T cell and antibody responses in COVID-19 patients with different disease severity. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:592629. [PMID: ] doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.592629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kwon JS , Kim JY , Kim MC , et al. Factors of severity in patients with COVID-19: cytokine/chemokine concentrations, viral load, and antibody responses. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:2412-2418. [PMID: ] doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li K , Huang B , Wu M , et al. Dynamic changes in anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies during SARS-CoV-2 infection and recovery from COVID-19. Nat Commun. 2020;11:6044. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19943-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu J , Guo J , Xu Q , et al. Detection of IgG antibody during the follow-up in patients with COVID-19 infection [Letter]. Crit Care. 2020;24:448. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03138-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liu L , Liu W , Zheng Y , et al. A preliminary study on serological assay for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in 238 admitted hospital patients. Microbes Infect. 2020;22:206-211. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu R , Liu X , Yuan L , et al. Analysis of adjunctive serological detection to nucleic acid test for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection diagnosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;86:106746. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liu X , Wang J , Xu X , et al. Patterns of IgG and IgM antibody response in COVID-19 patients [Letter]. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:1269-1274. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1773324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liu J , Lian R , Zhang G , et al. Changes in serum virus-specific IgM/IgG antibody in asymptomatic and discharged patients with reoccurring positive COVID-19 nucleic acid test (RPNAT). Ann Med. 2021;53:34-42. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1080/07853890.2020.1811887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lynch KL , Whitman JD , Lacanienta NP , et al. Magnitude and kinetics of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses and their relationship to disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pancrazzi A , Magliocca P , Lorubbio M , et al. Comparison of serologic and molecular SARS-CoV 2 results in a large cohort in Southern Tuscany demonstrates a role for serologic testing to increase diagnostic sensitivity. Clin Biochem. 2020;84:87-92. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2020.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Payne DC , Smith-Jeffcoat SE , Nowak G , et al; CDC COVID-19 Surge Laboratory Group. SARS-CoV-2 infections and serologic responses from a sample of U.S. Navy service members — USS Theodore Roosevelt, April 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:714-721. [PMID: ] doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Petersen LR , Sami S , Vuong N , et al. Lack of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in a large cohort of previously infected persons. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Qu J , Wu C , Li X , et al. Profile of immunoglobulin G and IgM antibodies against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2255-2258. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Robbins T , Kyrou I , Laird S , et al. Healthcare staff perceptions & misconceptions regarding antibody testing in the United Kingdom: implications for the next steps for antibody screening. J Hosp Infect. 2020. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schaffner A , Risch L , Weber M , et al. Sustained SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid antibody levels in nonsevere COVID-19: a population-based study [Letter]. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;59:e49-e51. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Seow J , Graham C , Merrick B , et al. Longitudinal observation and decline of neutralizing antibody responses in the three months following SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:1598-1607. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-00813-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shang Y , Liu T , Li J , et al. Factors affecting antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with severe COVID-19 [Letter]. J Med Virol. 2021;93:612-614. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1002/jmv.26379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shen B , Zheng Y , Zhang X , et al. Clinical evaluation of a rapid colloidal gold immunochromatography assay for SARS-Cov-2 IgM/IgG. Am J Transl Res. 2020;12:1348-1354. [PMID: ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shu H , Wang S , Ruan S , et al. Dynamic changes of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 patients at early stage of outbreak. Virol Sin. 2020;35:744-751. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1007/s12250-020-00268-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Staines HM , Kirwan DE , Clark DJ , et al. IgG seroconversion and pathophysiology in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27. [PMID: ] doi: 10.3201/eid2701.203074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Stock da Cunha T, Gomá-Garcés E, Avello A, et al.. The spectrum of clinical and serological features of COVID-19 in urban hemodialysis patients. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [PMID: ] doi: 10.3390/jcm9072264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sun B , Feng Y , Mo X , et al. Kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 specific IgM and IgG responses in COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:940-948. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1762515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Suthar MS , Zimmerman MG , Kauffman RC , et al. Rapid generation of neutralizing antibody responses in COVID-19 patients. Cell Rep Med. 2020;1:100040. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Takahashi T , Ellingson MK , Wong P , et al; Yale IMPACT Research Team. Sex differences in immune responses that underlie COVID-19 disease outcomes. Nature. 2020;588:315-320. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2700-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Terpos E, Politou M, Sergentanis TN, et al. Anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses in convalescent plasma donors are increased in hospitalized patients; subanalyses of a phase 2 clinical study. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1885. doi:10.3390/microorganisms8121885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64. Theel ES , Harring J , Hilgart H , et al. Performance characteristics of four high-throughput immunoassays for detection of IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1128/JCM.01243-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Traugott M , Aberle SW , Aberle JH , et al. Performance of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 antibody assays in different stages of infection: comparison of commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and rapid tests. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:362-366. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Van Elslande J, Decru B, Jonckheere S, et al.. Antibody response against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and nucleoprotein evaluated by four automated immunoassays and three ELISAs. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1557.e1-1557.e7. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wang B , Van Oekelen O , Mouhieddine TH , et al. A tertiary center experience of multiple myeloma patients with COVID-19: lessons learned and the path forward. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:94. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00934-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wang K , Long QX , Deng HJ , et al. Longitudinal dynamics of the neutralizing antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wang P . Combination of serological total antibody and RT-PCR test for detection of SARS-COV-2 infections. J Virol Methods. 2020;283:113919. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2020.113919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wendel S , Kutner JM , Machado R , et al. Screening for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in convalescent plasma in Brazil: preliminary lessons from a voluntary convalescent donor program. Transfusion. 2020;60:2938-2951. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1111/trf.16065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wolff F , Dahma H , Duterme C , et al. Monitoring antibody response following SARS-CoV-2 infection: diagnostic efficiency of 4 automated immunoassays. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;98:115140. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2020.115140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Xiang F , Wang X , He X , et al. Antibody detection and dynamic characteristics in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:1930-1934. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Xie L , Wu Q , Lin Q , et al. Dysfunction of adaptive immunity is related to severity of COVID-19: a retrospective study. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2020;14:1753466620942129. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1177/1753466620942129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Xu X , Sun J , Nie S , et al. Seroprevalence of immunoglobulin M and G antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in China. Nat Med. 2020;26:1193-1195. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0949-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Young BE , Ong SWX , Ng LFP , et al; Singapore 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak Research team. Viral dynamics and immune correlates of COVID-19 disease severity. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zhang B , Zhou X , Zhu C , et al. Immune phenotyping based on the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and IgG level predicts disease severity and outcome for patients with COVID-19. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:157. [PMID: ] doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.00157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zhao G , Su Y , Sun X , et al. A comparative study of the laboratory features of COVID-19 and other viral pneumonias in the recovery stage. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34:e23483. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1002/jcla.23483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zhao J , Yuan Q , Wang H , et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2027-2034. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zheng Y , Yan M , Wang L , et al. Analysis of the application value of serum antibody detection for staging of COVID-19 infection. J Med Virol. 2021;93:899-906. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1002/jmv.26330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. EUA authorized serology test performance. 8 January 2021. Accessed at www.fda.gov/medical-devices/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-emergency-use-authorizations-medical-devices/eua-authorized-serology-test-performance on 25 January 2021.

- 81. Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND). SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic pipeline 2020. October 2020. Accessed at www.finddx.org/covid-19/pipeline/?avance=all&type=all&test_target=Antibody&status=all§ion=immunoassays&action=default#diag_tab on 25 January 2021.

- 82. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Serology-based tests for COVID-19. Accessed at www.centerforhealthsecurity.org/resources/COVID-19/serology/Serology-based-tests-for-COVID-19.html#sec2 on 30 October 2020.

- 83. Lumley SF , O'Donnell D , Stoesser NE , et al; Oxford University Hospitals Staff Testing Group. Antibody status and incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in health care workers. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:533-540. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lumley SF , Wei J , O'Donnell D , et al; Oxford University Hospitals Staff Testing Group. The duration, dynamics and determinants of SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses in individual healthcare workers. Clin Infect Dis. 2021. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Pray IW , Gibbons-Burgener SN , Rosenberg AZ , et al. COVID-19 outbreak at an overnight summer school retreat — Wisconsin, July–August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1600-1604. [PMID: ] doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6943a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Addetia A , Crawford KHD , Dingens A , et al. Neutralizing antibodies correlate with protection from SARS-CoV-2 in humans during a fishery vessel outbreak with a high attack rate. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1128/JCM.02107-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA fact sheet: antibody test oversight and use for COVID-19. 4 May 2020. Accessed at www.fda.gov/media/137599/download on 25 January 2021.

- 88. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Investigative criteria for suspected cases of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection (ICR). 27 October 2020. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/invest-criteria.html on 25 January 2021.

- 89.Understanding Immunity to SARS-CoV-2, the Coronavirus Causing COVID-19 [clinical trial]. Accessed at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04373148 on 30 January 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.