Graphical abstract

Keywords: Sulfonamides, Cationic surfactants, Petro-collecting, Petro-dispersing, Biocidal activity, Molecular docking

Abstract

Surfactants with their diverse activities have been recently involved in controlling the spread of new coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic as they are capable of disrupting the membrane surrounding the virus. Using hybrids approach, we constructed a novel series of cationic surfactant-sulfonamide conjugates (3a-g) through quaternization of the as-prepared sulfonamide derivatives (2a-g) with n-hexadecyl iodide followed by structural characterization by spectroscopy (IR and NMR). Being collective properties required in petroleum-processing environment, the petro-collecting/dispersing capacities on the surface of waters with different degrees of mineralization, and the antimicrobial performance against microbes and sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) that mitigate microbiological corrosion were investigated for the synthesized conjugates. Among these conjugates, 3g (2.5% aq. solution) exhibited the strongest ability to disperse the thin petroleum film on the seawater surface, whereas KD is 95.33% after 96 h. In diluted form, 3f collected the petroleum layer on distilled water surface (Kmax = 32.01) for duration exceeds 4 days. Additionally, almost all compounds revealed high potency and comparable action with standard antimicrobials, especially 3b and 3f, which emphasize their role as potential biocides. Regarding biocidal activity against SRB, 3g causes a significant reduction in the bacterial count from 2.8 × 106 cells/mL to Nil. Moreover, the conducted molecular docking study confirms the strong correlation between RNA polymerase binding with bioactivity against microbes over other studied proteins (threonine synthase and cyclooxygenase-2).

1. Introduction

Discovery of lead candidates for multiple applications or purposes is a hot area of scientific research. High-throughput screening (HTS), HTS-coupled optimization and hybrids/conjugates approaches are the most common methods for developing multi-function compounds. Surfactants are always attracting a great attention because of possessing a wide variety of applications in medicine as drug carriers, foamers, wetting agents, and in industry as emulsifiers, corrosion inhibitors, paint additives as well as great potential use in surfactant flooding for enhanced oil recovery [1], [2]. Specifically, cationic surfactants with their excellent solubility, strong adsorption capability, high antimicrobial activity and improved wettability as unique indices are useful for numerous applications [3]. The positively-charged nitrogen in their structures is considered the main responsible constituent for the most of their principal features beside their tendency to be adsorbed at negatively-charged surfaces. The latter property facilitates their use as anticorrosive agents for steel, dispersants for inorganic pigments, cationic softeners for fabrics, flotation collectors for mineral ores, anticaking agents for fertilizers, and carriers/solubilizers for drugs [4]. A model example of these compounds is benzalkonium chlorides (BAC, Fig. 1 ) which possesses many functions including good detergency, antibacterial, fabric-softening, and catalytic activities.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of some bioactive sulfonamides, BAC, and our conjugates.

As a group of pharmaceuticals, sulfonamide derivatives such as sulfamethoxazole [5], E7820 [6] and tolbutamide [5] (Fig. 1) with their SO2NH group bonded directly to aromatic ring are classified as one of the oldest agents with promising therapeutic effect [7]. Previously reported studies return their strong activities toward numerous biological systems such as malaria parasites [8], tuberculosis [9], cancer [10], microbes [11], and inflammation [12] to the presence of the sulfonamide group.

Increasing in the resistance of many microbes to common drugs directed researchers to focus on developing effective alternatives. Cationic surfactants are a perfect option as they can disrupt the integral membrane protein of the microbial cell at the membrane/water interface [13], [14]. Their extraordinary antimicrobial activity was correlated and rationalized to the bioactivity of other moieties conjugated to the cationic groups. In addition, their biocidal action against microbial strains could be introduced to the well formation due to other well stimulation methods such as hydraulic cracking that may cause microbial-induced corrosion [15], [16], [17]. Sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) usually accompany the crude petroleum production and their growth exhibits severe corrosive action in processing-related tools including pipelines and tanks. A big issue such as oil well souring may occur due to the extreme multiplication of SRB cells. Cationic surfactants exhibit high efficiency in killing the SRB [15], [18], [19] and some reports confirm the importance of some functionality like amino, cyano, hydroxy, and mercapto groups [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23] in enhancing the biological activity [24], [25] . For instance, introducing hydroxyl group could significantly improve the water solubility of the cationic surfactants, while sulfonamide group helped the them to achieve good antimicrobial activity [26], [27], [28].

The pollution of water surface with petroleum is one of the main problems facing world and due to different reasons, including accidents in oil pipelines, and oil tankers, a large quantity of petroleum oil enters the hydrosphere. The thick petroleum film can be separated easily via mechanical techniques while the remaining thin film is ecologically hazardous. To overcome this problem, many solutions including colloid-chemical methods were utilized to remove such thin oil films through the application of petro-collecting and petro-dispersing agents [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37]. Surfactants, especially conventional and gemini-cationic surfactants, are proven to be the most efficient dispersing and collecting materials for cleaning the water surface from petroleum thin films produced in stages of oil processing [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44]. Another accompanying issue is the development of microbes during petroleum processing.

As a good solution for addressing these issues, the current work utilized the hybrids approach to make benefits of both the sulfonamide and fatty ammonium salts (cationic surfactant) substructures for the construction of novel conjugates. Therefore, they combine the advantages and characteristics of both parts making them suitable for multiple applications. To test their convenience for the use in petroleum-related processes, three features were intensively-evaluated: petro-collecting/dispersing indices, antimicrobial activities, and biocidal activities against SRB. Furthermore, compounds that possess variable antibacterial activities were docked into the pockets of selected target proteins with the aim of recognizing the possible mechanism by which these compounds acquire their activities. Collectively, the results of this study induce the continuation to construct surfactant-drug hybrids having various properties.

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemistry

A XT-4 binocular microscope (Tianjin Analytical Instrument Factory, China) was used for determining the uncorrected melting points of compounds. Via a Nicolet Avatar 330 FT-IR spectrometer, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was recorded. 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectra for DMSO‑d 6 samples’ solutions were recorded on a Bruker Avance 600 MHz instrument using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal standard. Multiplicities of signals were expressed by their coupling constants (J) that were reported in Hz. TLC, using aluminum silica gel, was used to monitor the progress of all reactions. Purification of the target molecules was carried out using silica gel (200–300 mesh) column chromatography.

2.1.1. General procedure for the synthesis of sulfonamide derivatives (2a-g)

To a solution of N,N-dimethyl-1,3-diaminopropane (1.16 g, 11.32 mmol) and Et3N (1.43 g, 14.16mmol) in CH2Cl2 (50 mL), benzene, 4-cyanobenzene, 2-thiophene, 2-naphthalene, 2,4,6-triisopropylbenzene, 4-(tert-butyl)benzene, or 3-(trifluoromethyl)benzene sulphonyl chlorides (5.66 mmol) was added in several portions. After completing the addition, the reaction mixture was kept stirring for 10 h at room temperature. Then, 50 mL of half-saturated sodium chloride solution was poured into the mixture followed by extraction with CH2Cl2 (50 mL × 3). After separating and drying the organic phase with anhydrous Na2SO4, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude products were purified by flash column chromatography (CHCl3:MeOH = 5:1) to produce 2a-g as white to yellow solids with 90–96% yields.

2.1.2. Quaternarization of sulfonamide derivatives: Synthesis of conjugates (3a-g)

1-Iodohexadecane (1.6 mmol) was added to a solution of 2a-g, separately (0.8 mmol) in anhydrous ethyl acetate (0.3 M). The reaction solution was refluxed at 70 °C for 15–24 h. After equilibrating the reaction mixture solution to room temperature, the solid precipitate was granulated for 5 h at 0 °C. The solid products were obtained by filtration and via washing several times with anhydrous diethyl ether to remove the unreacted materials followed by drying in air. The yields of the target products were ranging from 70 to 91%.

2.1.3. N,N-Dimethyl-N-(3-(phenylsulfonamido)propyl)hexadecan-1-aminium Iodide (3a)

Yield: 91%, yellowish white solid, m.p. 60–62 °C: IR(KBr) νmax: 3229, 3039, 2939, 2852, 1472, 1319, 1161, 1083 cm−1. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ 7.82–7.79 (m, 2H), 7.75 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 7.69–7.66 (m, 1H), 7.63 (dd, J = 8.2, 6.6 Hz, 2H), 3.29–3.23 (m, 2H), 3.23–3.18 (m, 2H), 2.97 (s, 6H), 2.80 (q, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 1.83–1.77 (m, 2H), 1.62 (p, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.24 (s, 26H), 0.85 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ 140.37, 133.09, 129.83, 126.97, 63.63, 61.06, 60.24, 50.64, 33.33, 31.76, 30.28, 29.89, 29.52, 29.48, 29.43, 29.36, 29.30, 29.17, 28.97, 28.31, 26.22, 22.88, 22.56, 22.10, 21.24, 14.42.

2.1.4. N-(3-((4-Cyanophenyl)sulfonamido)propyl)-N,N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium Iodide (3b)

Yield: 83%, white solid, m.p. 128–130 °C: IR(KBr) νmax: 3051, 2920, 2850, 2231 (C N), 1464, 1323, 1155, 1093 cm−1. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ 8.20 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 8.03–7.98 (d, 2H), 7.92–7.88 (d, 2H), 3.26 (td, J = 8.3, 7.5, 3.0 Hz, 2H), 3.24–3.16 (m, 2H), 2.99 (s, 6H), 1.90–1.81 (m, 2H), 1.63 (dq, J = 15.0, 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.28–1.20 (m, 26H), 0.85 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ 148.23, 134.77, 133.28, 132.65, 130.01, 125.04, 63.64, 60.96, 50.66, 33.34, 31.76, 30.28, 29.53, 29.50, 29.48, 29.43, 29.37, 29.31, 29.17, 28.98, 28.32, 26.23, 23.05, 22.56, 22.10, 14.43, 9.60.

2.1.5. N,N-Dimethyl-N-(3-(thiophene-2-sulfonamido)propyl)hexadecan-1-aminium Iodide (3c)

Yield: 89%, white solid, m.p. 68–70 °C: IR(KBr) νmax: 3150, 3029, 2919, 2850, 1466, 1332, 1157, 1069 cm−1. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ 7.97 (dd, J = 5.0, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.94 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (dd, J = 3.8, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (dd, J = 5.0, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 3.29–3.24 (m, 2H), 3.24–3.20 (m, 2H), 2.99 (s, 6H), 2.89 (q, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 1.89–1.79 (m, 2H), 1.67–1.59 (m, 2H), 1.25 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 26H), 0.86 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ 141.19, 133.24, 132.21, 128.31, 63.62, 61.04, 60.23, 50.65, 31.76, 29.53, 29.48, 29.43, 29.31, 29.18, 28.98, 26.24, 22.77, 22.57, 22.11, 21.24, 14.43.

2.1.6. N,N-Dimethyl-N-(3-(naphthalene-2-sulfonamido)propyl)hexadecan-1-aminium Iodide (3d)

Yield: 80%, pale yellow solid, m.p. 70–72 °C: IR(KBr) νmax: 3070, 2919, 2850, 1468, 1321, 1151, 1084 cm−1. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ 8.45 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 8.17 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.5 Hz, 2H), 8.07 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.87–7.82 (m, 2H), 7.71 (dddd, J = 21.9, 8.2, 6.9, 1.3 Hz, 2H), 3.27–3.21 (m, 2H), 3.21–3.15 (m, 2H), 2.96 (s, 6H), 2.84 (q, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 1.81 (dd, J = 10.4, 6.5 Hz, 2H), 1.60 (dd, J = 10.3, 6.4 Hz, 2H), 1.24 (t, J = 4.3 Hz, 26H), 0.86 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ 137.37, 134.68, 132.19, 130.02, 129.63, 129.31, 128.33, 128.17, 127.96, 122.65, 63.62, 61.07, 50.63, 33.33, 31.75, 30.28, 29.52, 29.50, 29.47, 29.42, 29.36, 29.29, 29.16, 28.95, 28.31, 26.20, 22.89, 22.56, 22.08, 14.43, 9.62.

2.1.7. N,N-Dimethyl-N-(3-((2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl)sulfonamido)propyl)hexadecan-1-aminium Iodide (3e)

Yield: 75%, yellowish white solid, m.p. 103–105 °C: IR(KBr) νmax: 3176, 3029, 2958, 2850, 1469, 1316, 1155, 1100 cm−1. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ 7.59 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (s, 2H), 4.10 (p, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 3.28–3.25 (m, 2H), 3.24–3.18 (m, 2H), 2.98 (s, 6H), 2.91 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 2.86 (q, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 1.85 (dq, J = 11.8, 6.3 Hz, 2H), 1.67–1.60 (m, 2H), 1.24 (s, 26H), 1.21 (dd, J = 6.8, 3.1 Hz, 18H), 0.85 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ 152.65, 150.16, 133.14, 124.10, 63.63, 61.14, 50.73, 33.78, 31.76, 29.51, 29.47, 29.45, 29.41, 29.30, 29.28, 29.17, 28.95, 26.23, 25.23, 23.89, 22.89, 22.56, 22.09, 14.42, 9.62.

2.1.8. N-(3-((4-(tert-Butyl)phenyl)sulfonamido)propyl)-N,N-dimethylhexadecan-1-aminium Iodide (3f)

Yield: 90%, white solid, m.p. 101–103 °C: IR(KBr) νmax: 3078, 2919, 2850, 1470, 1329, 1161, 1083 cm−1. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ 7.75–7.71 (m, 2H), 7.68 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 7.65–7.61 (m, 2H), 3.27–3.23 (m, 2H), 3.23–3.19 (m, 2H), 2.97 (s, 6H), 2.79 (q, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 1.80 (td, J = 11.3, 10.0, 5.7 Hz, 2H), 1.63 (p, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.31 (s, 9H), 1.24 (s, 26H), 0.85 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ 156.02, 137.58, 126.91, 126.63, 63.63, 61.07, 50.64, 35.33, 31.76, 31.28, 29.52, 29.48, 29.43, 29.30, 29.17, 28.97, 26.23, 22.89, 22.56, 22.10, 14.43.

2.1.9. N,N-Dimethyl-N-(3-((3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)sulfonamido)propyl)hexadecan-1-aminium Iodide (3g)

Yield: 73%, yellowish white solid, m.p. 62–64 °C: IR(KBr) νmax: 3054, 2924, 2844, 1473, 1329, 1164, 1083 cm−1. 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ 8.22–8.18 (m, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 8.09 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.37–3.32 (m, 3H), 3.29 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 3.07 (s, 6H), 2.92 (q, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 1.90 (dq, J = 11.7, 6.5, 5.7 Hz, 2H), 1.70 (tt, J = 11.6, 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.32 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 26H), 0.92 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ 141.62, 131.57, 131.16, 130.55, 130.33, 129.91, 129.89, 124.80, 123.48, 123.45, 123.00, 63.63, 60.95, 60.23, 50.66, 33.33, 31.75, 30.28, 29.52, 29.47, 29.42, 29.36, 29.29, 29.17, 28.96, 28.31, 26.21, 22.96, 22.56, 22.10, 21.23, 14.55, 14.41, 9.58. 19F NMR (565 MHz, DMSO‑d 6) δ − 61.39.

2.2. Procedure for evaluating petro-dispersing and petro-collecting capacities

Being surfactants, the synthesized conjugates have excellent solubility in water. Their petro-dispersing and petro-collecting capacities (in form of 2.5% aq. solution and untreated state) have been investigated on the surface of three waters of different mineralization degrees using the crude oil from Red sea in the South Sinai (Egypt) (at 20 °C its density is 0.86 g/cm3 and kinematic viscosity equals 0.16 cm2 s1). The solid-state surfactant (0.01 g) or its aqueous solution (2.5%) was added to a thin film (thickness ≈ 0.15 mm) of the crude oil on the tested waters’ surface (distilled, fresh (river) and the Red sea) in Petri dishes. Via the relationship K = So/S, petro-collecting factor (K) was calculated, whereas So is the surface area of the petroleum film at the beginning of the test, S denotes the surface area of the of the petroleum spot formed under the action of the surfactant. During the observations, the surface area of the spot was measured periodically, K-values were computed for these specific time intervals (τ). Petro-dispersing ability (KD) was calculated by the degree of cleaning of polluted water surface from petroleum which was calculated as a percentage of clean water surface areas and the initial area of the petroleum film.

Film thickness effect. Conjugates 3f and 3g (2.5% aq. solution) with the largest dispersing capacities were tested against petroleum films with different thicknesses. The thickness was controlled by changing the added volume of petroleum. Every 1.0 mL of petroleum corresponds to a thickness of 0.165 mm.

2.3. Biological assays

The biocidal activity of the cationic surfactant-sulfonamide conjugates was determined by using agar well diffusion method against some pathogenic bacteria and fungi as well as SRB. The Gram-negative (G−ve) bacteria were Escherichia coli (ATCC 8739) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 9027) while the Gram-positive (G+ve) bacteria were Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633) and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29737). The tested fungal models were Aspergillus niger (ATCC 16404) and Candida albicans (ATCC 10231). The anti-SRB activity was tested against Desulfovibrio sapovorans ATCC 33892 which was obtained from operation department, Egyptian Petroleum Research Institute while the different species of the microorganism were obtained from micro analytical center, Cairo University.

Growing of microbes. Strains of bacteria were streaked on nutrient agar media and incubated at 37 °C overnight however, the fungal strains were grown on sabouraud dextrose agar, and incubated at 30 °C for about 48 h.

Susceptibility Measurements. For inoculation and disc preparation, 1.0 mL of inocula was mixed with agar media (50 mL) at 40 °C. Then it was poured into Petri dishes (120 mm) and allowed to equilibrate to room temperature. Via convenient sterile tubes, wells with 6 mm- diameter were developed in the agar plates. Each well was filled up with 100 µL aqueous solution of the cationic surfactant-sulfonamide conjugate (1 mg/mL). All bacterial plates were kept at 37 °C incubation for 24 h while plates of fungal strains operated similarly at 30 °C for 48 h. The average value was calculated for three individual replicates to represent the sample zone of growth inhibition [19]. In parallel, Nalidixic acid (30 µg), Amoxicillin (30 µg) and Fluconazole (100 ppm) as positive controls, and sterile water as a negative control were tested against microbes. In addition, the % activity index was computed by the following equation [45]:

The lowest concentration of a biocide that is able to stop all progression of the microbial growth during a bioassay test is the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) [22]. However, the lowest concentration that exterminates 99% of the proliferated germs is called the minimum bactericidal/fungicidal concentration (MBC/MFC). The values of MIC, MBC and MFC for the cationic surfactant-sulfonamide conjugates were evaluated via applying broth microdilution method using a 96-sample microwell plates method as previously stated in Amsterdam protocol with further considerations. The inoculation preparations were propagated by the cultivation of the purchased bacterial strains in Difco™ Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) purchased from BD Biosciences, USA. The experimental inocula were prepared as previously described by Miller et. al., 2005 [46].

Microwell plates from Nunclon™, Germany (F, PS, non-TC-treated) were used to determine the MICs of the synthesized cationic surfactant-sulfonamide conjugates via two-fold micro-dilution technique. At the beginning, cationic surfactants (100 µL) were dispensed onto the microwell plates for a further inoculation with the prepared microbial inoculum suspension (100 µL). A positive control for the evaluated conjugates (media and inoculum) and a negative control (only media) were conducted. All microwell plates were incubated under aerobic condition for a duration of 20–22 h at 37 °C for bacteria and for 48 h at 30 °C in the case of fungal species [22]. MBC/MFC values of the prepared surfactants were estimated via the removal of the media that displays no visual microbial development from the wells, followed by their sub-culturing onto agar plates as before until the microbial development becomes visible in the control plates [24].

The effect of the cationic conjugates on the SRB was determined utilizing the serial dilution method based on ASTM D4412-84 [47]. Water contaminated with SRB had been received from General Petroleum Company, Egypt and subject to bacterial growth of 2.8 × 106 cells/mL. The conjugates, at a concentration of 5 mg/mL, and contact time of 3 h were cultured in a specific media for SRB at 30 °C for 21 days.

2.4. Molecular docking

The 3D-crystal structures of E. coli RNA polymerase (PDB ID: 4kn4), threonine synthase from B. subtilis ATCC 6633 (PDB ID: 6nmx) and cyclooxygenase-2 (PDB ID: 6cox) were obtained from PDB (www.rscb.org). All ligands in the structures were eliminated, and the final structures were saved as PDBQT formats using AutoDock Tools. The surfactant-sulfonamide hybrids (3a, 3b and 3e) were docked separately into the active pocket of the polymerase protein (PDB ID: 4kn4). Compounds 3b and 3f were also docked into threonine synthase protein (PDB ID: 6nmx). In addition, compound 3b was subjected for docking in the cyclooxygenase-2 protein (PDB ID: 6cox). All docking calculations were carried out using Autodock 4.2 [48] and Cygwin softwares using the step-wise protocol that was previously published [49].

For griding, 80 × 70 × 60 as grid points for all ligand atoms with a spacing of 0.375 A were used for calculations. Using Lamarckian genetic algorithm (GA), each docking calculation was performed with default parameters (energy evaluations = 2.5 million, maximum generations = 27000, population size = 150, mutation rate = 0.02 and crossover rate = 0.8) to get new docking trials for subsequent generations. For each compound, fifty binding poses were predicted with root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) clustering. Binding poses with the highest scores were selected and visualized using PyMol software [50]. In addition, the 2D-binding behaviors were presented using LigPlot + software [51].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Chemistry

Constructing compounds with distinguished activities against numerous targets can be easily achieved by hybrid approach. A single-functionalized molecule can work efficiently against only one target for specific application. In some cases/problems such molecules will not be the suitable solutions. Developing molecules with dual or multiple functions (hybrids or conjugates) will help in broadening their application types and subsequently they can affect multiple targets.

Cationic, anionic and polymeric surfactants have been used for solving problems in petroleum-processing environment [2], [39], [41], [43], [44]. Sulphonamide-incorporating compounds have found applications as antibacterial and antifungal agents. In the current work, we connected a cationic surfactant moiety to numerous aryl/heteroaryl sulphonamides via a propane spacer with the aim of synthesizing surfactant-sulphonamide conjugates (3a-g) for multiple applications. The synthetic route simply includes, first, the formation of N-substituted sulphonamides (2a-g) through a base-catalyzed dehydrochlorination of sulphonyl chloride derivatives (1a-g) with N,N-dimethylpropyl-1,3-diamine in a non-polar solvent (dichloromethane, DCM) followed by quaternization of the tertiary nitrogen with 1-iodo-hexadecane (Scheme 1 ).

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route for the cationic surfactant-sulfonamide conjugates.

The 1H NMR spectra of the target compounds classified their protons into three regions; fatty chain protons appeared in the highly shielded region (δ < 2 ppm); aromatic and NH protons in the highly deshielded region (δ > 7 ppm), and other aliphatic protons (except substituents on 3e and 3f) in the middle region of the spectra. The 13C NMR spectra showed a similar behavior to that of 1H NMR in classifying the types of carbon atoms within the structure. Interestingly, compound 3e exhibited a clear 1H NMR spectrum especially for the three isopropyl groups. As expected, the proton (of CH group) in position-4 emerged in an upfield region with respect to the other two. However, the multiplicity of the three protons appeared as quintet instead of septet ( Fig. 2 ). This means that each one of these protons was affected by only four adjacent protons (two of each methyl group) out of six. The third proton (in methyl group) of one isopropyl group may be coupled with proton in methyl group of another isopropyl group.

Fig. 2.

Zoomed 1H NMR spectrum (region: 2.85–4.15 ppm) of compound 3e.

3.2. Petro-dispersing and petro-collecting abilities of the synthesized conjugates

As a result of accidents occurring during oil-carrying tankers, oil pipelines, transportation of petroleum, pollution of water surface takes place [52]. After removing thick oil slicks via various mechanical techniques, thin oil films inevitably contaminate the water surface which is impossible to remove by mechanical methods. Such films are hazardous for ecological system as they corrupt the oxygen absorption and prevent sunlight penetration into water-depth damaging the conditions of life for marine inhabitants [53]. So, the application of petro-collecting or dispersing agents is considered the most convenient method for removing thin oil films.

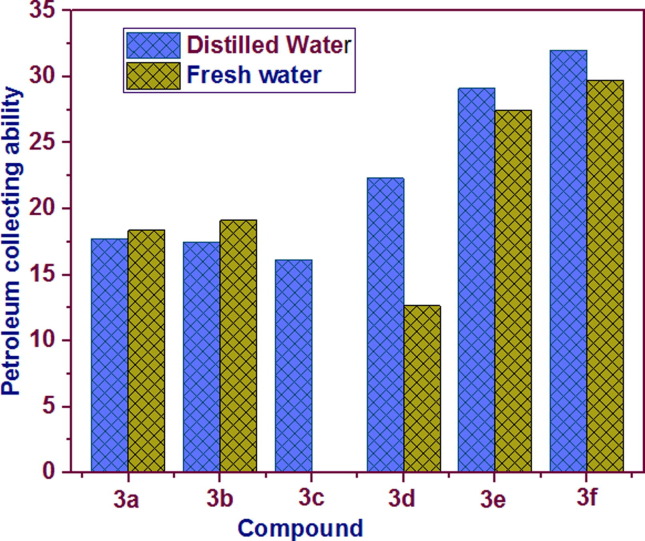

The results of petro-dispersing and petro-collecting indices of the as-prepared bioactive cationic surfactants were recorded in Table 1 and Fig. 3 , S1 and conducted in parallel for both pure-state solids and their 2.5% wt. aqueous solutions. It is noticeable that in undiluted form all synthesized cationic surfactants were unstable to enhance the petro-dispersing and collecting properties. Interestingly, in the sea water, 3f and 3g gave excellent petro-dispersing action in diluted form, whereas KD ranges from 73.17 to 91.22%, τ = 0–96 h and from 71.27 to 95.33%, τ = 0–96 h, respectively. These compounds can maintain its effect for longer more than 4 days. Moreover, 3g in distilled and fresh waters behaves as a petro-dispersant, whereas KD ranges from 63.17 to 91.22%, τ = 0–96 h and from 65.77 to 93.56%, τ = 0–96 h, respectively.

Table 1.

Petro-collecting/dispersing properties of the synthesized cationic surfactant-sulfonamide conjugates 3a-g.

| Compd. No. |

Undiluted product |

2.5% wt. water solution |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Distilled water |

Fresh water |

Sea water |

Distilled water |

Fresh water |

Sea water |

|||||||

| τ (h) | K (kD) | τ (h) | K (kD) | τ (h) | K (kD) | τ (h) | K (kD) | τ (h) | K (kD) | τ (h) | K (kD) | |

| 3a | 0–2 | NEa | 0–2 | NE | 0–2 | NE | 0–2 | 5.29 ± 0.9 | 0–2 | 3.29 ± 0.7 | 0–2 | NE |

| 30 | 3.91 ± 0.8 | 20 | 2.84 ± 0.9 | 5–20 | 3.91 ± 1.1 | 30 | 7.27 ± 1.2 | 30 | 4.30 ± 1.8 | 20 | 5.37 ± 0.8 | |

| 60–96 | 4.17 ± 1.0 | 25–96 | 5.70 ± 0.5 | 30–60 | 3.30 ± 0.3 | 48–96 | 17.73 ± 1.6 | 40–60 | 10.17 ± 1.1 | 40–96 | 8.88 ± 0.9 | |

| – | – | – | – | 70–96 | 4.1 ± 0.7 | – | – | 70–96 | 18.36 ± 1.9 | – | – | |

| 3b | 0–2 | 3.45 ± 0.1 | 0–2 | 4.10 ± 0.7 | 0–2 | 2.40 ± 0.7 | 0–2 | 7.33 ± 0.1 | 0–2 | 6.16 ± 0.8 | 0–2 | 5.78 ± 0.8 |

| 2–55 | 5.22 ± 0.6 | 30–60 | 7.23 ± 1.0 | 5–20 | NCb | 2–55 | 9.11 ± 0.1 | 30–60 | 10.78 ± 1.1 | 5–20 | 7.34 ± 0.5 | |

| 60–96 | 6.66 ± 0.1 | 60–96 | 10.1 ± 0.8 | 30–96 | NC | 60–96 | 17.45 ± 0.4 | 60–96 | 19.12 ± 0.6 | 30–96 | NC | |

| 3c | 0–2 | 3.67 ± 0.1 | 0–2 | 5.22 ± 0.6 | 0–2 | 2.40 ± 0.3 | 0–2 | 6.77 ± 0.8 | 0–2 | 60.23% | 0–2 | 4.37 ± 0.1 |

| 2–55 | 6.11 ± 0.2 | 30–60 | 5.48 ± 1.3 | 5–20 | NC | 2–55 | 8.23 ± 0.5 | 30–60 | 77.78% | 5–20 | 5.92 ± 0.4 | |

| 60–96 | 7.19 ± 0.7 | 60–96 | 8.53 ± 1.0 | 30–96 | NC | 60–96 | 16.12 ± 0.1 | 60–96 | 83.67% | 30–96 | NC | |

| 3d | 0–2 | 2.32 ± 0.8 | 0–2 | 4.21 ± 0.6 | 0–2 | 3.23 ± 0.9 | 0–2 | 6.76 ± 1.0 | 0–2 | 5.21 ± 0.5 | 0–2 | 6.33 ± 0.2 |

| 2–55 | 5.21 ± 0.1 | 30–60 | NC | 5–20 | 6.54 ± 0.1 | 5–20 | 8.23 ± 0.1 | 30–60 | 7.23 ± 0.6 | 5–20 | 8.91 ± 0.8 | |

| 60–96 | 7.25 ± 0.3 | 60–96 | NC | 30–96 | 8.76 ± 0.1 | 30–96 | 22.34 ± 0.9 | 60–96 | 12.65 ± 0.1 | 30–96 | 11.88 ± 1.2 | |

| 3e | 0–2 | 3.23 ± 0.1 | 0–2 | 2.32 ± 0.2 | 0–2 | 4.21 ± 1.1 | 0–2 | 10.76 ± 0.8 | 0–2 | 8.55 ± 0.1 | 0–2 | 1.16 ± 0.8 |

| 2–55 | 6.54 ± 0.1 | 30–60 | 5.21 ± 0.2 | 5–20 | NC | 5–20 | 16.89 ± 1.4 | 30–60 | 16.11 ± 0.7 | 5–20 | NC | |

| 60–96 | 8.76 ± 0.4 | 60–96 | 7.25 ± 0.1 | 30–96 | NC | 30–96 | 29.11 ± 0.9 | 60–96 | 27.43 ± 1.5 | 30–96 | NC | |

| 3f | 0–2 | 10.76 ± 0.8 | 0–2 | 7.85 ± 0.3 | 0–2 | 65.27% | 0–2 | 12.21 ± 0.7 | 0–2 | 8.35 ± 0.2 | 0–2 | 73.17% |

| 2–55 | 11.44 ± 0.1 | 30–60 | 10.89 ± 0.4 | 5–20 | 68.02% | 5–20 | 18.32 ± 0.6 | 30–60 | 16.32 ± 0.2 | 5–20 | 88.32% | |

| 60–96 | 12.23 ± 0.3 | 60–96 | 11.03 ± 0.4 | 30–96 | 73.66% | 30–96 | 32.01 ± 0.2 | 60–96 | 29.76 ± 0.9 | 30–96 | 91.22% | |

| 3g | 0–2 | 60.11% | 0–2 | 61.23% | 0–2 | 70.03% | 0–2 | 63.17% | 0–2 | 65.77% | 0–2 | 71.27% |

| 2–55 | 62.12% | 30–60 | 63.44% | 5–20 | 75.11% | 5–20 | 85.38% | 30–60 | 88.31% | 5–20 | 90.32% | |

| 60–96 | 77.23% | 60–96 | 79.01% | 30–96 | 83.03% | 30–96 | 91.22% | 60–96 | 93.56% | 30–96 | 95.33% | |

NEa = No Effect, NCb = No Change.

Fig. 3.

Petro-collecting capacities of the synthesized conjugates 3a-f.

The collection of petroleum occurred in fresh water (Kmax = 29.76) and distilled water (Kmax = 32.01) by the action of the 2.5% aqueous solution of 3f. In the case of 2.5% aqueous solution of 3e, in the distilled and fresh waters, a collecting of petroleum is observed, whereas Kmax = 22.34 and 12.65, Kmax = 29.11 and 27.43, respectively. Compound 3c in an aqueous solution registered a dual action as a petro-collecting property in the distilled water (Kmax = 16.12) and in the fresh water only petro-dispersing is observed (KD = 83.67%), τ exceeding 4 days. In diluted form, 3a and 3b collect the petroleum in distilled water (Kmax = 17.73 and 17.45, respectively) and in fresh water (Kmax = 18.36 and 19.12, respectively), duration of action exceeds 4 days.

The values of petro-dispersing and petro-collecting coefficients reported by Tantawy et al., 2017 [44] for dodecyl methacrylate-vinyl imidazolium salt copolymers as well as gemini cationic surfactants based on Guava fat [39] are smaller than those for our synthesized bioactive cationic surfactants.

Regarding the structure-petroleum capacity relationship, compounds with mono-substitution at meta or para position on the benzenesulfonamide moiety (3b, 3f and 3g) exhibited the highest petroleum capacities. Removing such substitution or introducing bulky groups at ortho positions (3a and 3e) results in a sharp drop in collecting/dispersing petroleum film. Furthermore, replacing phenyl group in 3a with thiophene (3c) could not improve its ability to collect or disperse the petroleum film. Therefore, structure optimization for enhanced petroleum capacity may include designing compounds with simple substitution such as methoxy, hydroxy, dimethylamino, etc. on the benzene ring, especially at para position.

To explore the effect of the petroleum film thickness, the petro-dispersing capacity of the 2.5% aqueous solution of the most efficient dispersant conjugates (3f and 3g) in seawater was investigated against different thicknesses varying from 0.165 to 1.155 mm. As clearly shown in Fig. 4 , the tested surfactant-sulfonamide conjugates 3f and 3g displayed the best effect in the relatively thin film and this effect was gradually decreased with raising the thickness. These derivatives exhibited almost stable and strong dispersing capacity (>70%) with increasing the film thickness up to 0.7 mm. This indicates their effectiveness in removing not only thin films but also the thick layers of petroleum.

Fig. 4.

Petro-dispersing properties of the synthesized conjugates 3f and 3g toward Red sea crude slicks of different thicknesses.

3.3. In vitro antimicrobial activity

The antibacterial and antifungal activities of the conjugates (3a-g) against pathogenic G−ve (E. coli & P. aeuroginosa), G+ve (S. aureus & B. subtilis) bacteria, and fungi (C. albicans & A. niger) were investigated and depicted in Table 2 . These results show that the biocidal efficacy of these surfactants powerfully associated with the existence of the heteroatoms (N, F, and S), the aromatic ring nucleus, and the sulfonamide group in their structures [17]. The strong activity of the conjugates can be interpreted on the basis of their physical adsorption at the microbial cell wall surface disrupting the cell membrane, followed by penetration that causes inadequate selective permeability permitting the cytoplasm release and hence cell apoptosis (Fig. 5 ). This mechanism depends on the adsorption affinity of these surfactants on the cell membrane being consisted of a bilayer of phospholipid along with proteins. Giving a focus look, such affinity comes from the electrostatic interaction between the negatively-charged lipid membrane and the positively-charged conjugates (Fig. 5) beside other lipophilic interactions that facilitate the penetration into cell [15], [18], [19], [23].

Table 2.

In vitro antimicrobial activity of the synthesized cationic surfactant-sulfonamide conjugates in term of inhibition zone diameter.

| Compd. No. |

Inhibition zone diameter in mma(% activity index) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gram-positive bacteria |

Gram-negative bacteria |

Fungi |

||||

| B. subtilis (ATCC 6633) | S. aureus (ATCC 29737) |

P. aeruginosa (ATCC 9027) |

E. coli (ATCC 8739) |

C. albicans (ATCC 10231) |

A. niger (ATCC16404) |

|

| 3a | 16 (94.2) | 14 (70) | 11 (61.1) | 13 (72.2) | 14 (93.3) | Nil |

| 3b | 18 (105.9) | 17 (85) | 12 (66.7) | 18 (100) | 14 (93.3) | 12 (80) |

| 3c | 16 (94.2) | 11 (55) | 13 (72.2) | 14 (77.8) | 14 (93.3) | 12 (80) |

| 3d | 14 (82.4) | 16 (80) | 11 (61.1) | 12 (66.7) | 14 (93.3) | Nil |

| 3e | 13 (76.5) | 12 (60) | Nil | 12 (66.7) | 13 (86.7) | Nil |

| 3f | 19 (111.8) | 14 (70) | 11 (61.1) | 18 (100) | 13 (86.7) | 12 (80) |

| 3g | 16 (94.2) | 15 (75) | 12 (66.7) | 14 (77.8) | 14 (93.3) | Nil |

| AMCb (30 µg) | 17 | 20 | NTe | NT | NT | NT |

| NAc (30 µg) | NT | NT | 18 | 18 | NT | NT |

| Flud (100 ppm) | NT | NT | NT | NT | 15 | 15 |

Standard deviation = 5%, AMCb = Amoxicillin, NAc = Nalidixic acid, Flud = Fluconazole, NTe = Not tested.

Fig. 5.

Representation for the surfactant action on the bacterial cell membrane.

Our conjugates could significantly affect the G+ve bacterial profile and, as expected, the G−ve bacteria were more resistant than the G+ve ones (Table 2). For G+ve bacteria, layers of teichoic acids and peptidoglycans compose the cell wall [54], while high lipopolysaccharides and proteins are the main constituents of the G−ve bacteria outer membrane making them relatively insensitive which limits the entrance of amphiphilic compounds [26]. Therefore, the activity of the synthesized conjugates against G+ve is better than that of G−ve bacteria. Regarding the activity toward fungi, the cationic compounds exhibit moderate to good growth inhibition to C. albicans. Unlike bacteria, the fungal membranes are more rigid and resistant for biocides due to the presence of chitin and some amino sugars [55].

Collectively, all inhibitors showed acceptable antibacterial activities of 12–19 mm for G+ve and G−ve bacteria (11–18 mm). The cell wall G+ve bacteria embodies only single peptidoglycanic layer, which makes it more sensitive towards many antibacterial agents. While for the G−ve bacteria, the cell wall encompasses additional multilayers of membranes (outer lipid membrane and periplasm) that provides more resistance against most antibacterial agents [54]. Correspondingly, the mechanism of the bacterial cell wall disruption can be related to two main aspects: the number of terminal groups as well as the bio-permeability action. The penetration of the counter ions such as iodide into cells via the cellar membranes increases the potent action against microbes [19], [23]. The comparison of the zones of inhibition of antibacterial activity of compounds 3b and 3f shows that replacement of 4-cyano group by the 4-tert-butyl group increases the antimicrobial activity against B. subtilis.

The MICs, MBCs and MFCs of the cationic surfactant-sulfonamide conjugates were recorded in Table 3 . Collectively, compounds exhibited lower MICs/MBCs for the G−ve bacteria than G+ve ones. Moreover, they displayed comparable MICs/MFCs values against fungal strains with standard drugs. As previously mentioned, the net charge on molecules represents a vital parameter that determines their activities toward different microorganisms. Various reports confirm the key role of the electrostatic interactions in altering the biocidal activity, and demonstrate the effect of decreasing the charge density in reducing the adsorption and hence the antimicrobial efficiency [19].

Table 3.

The MICs, MBCs and MFCs of the synthesized conjugates against different standard microbial strains.

| Compd. No. |

Gram-positive bacteria |

Gram-negative bacteria |

Fungi |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

B. subtilis (ATCC 6633) |

S. aureus (ATCC 29737) |

P. aeruginosa (ATCC 9027) |

E. coli (ATCC 8739) |

C. albicans (ATCC 10231) |

A. niger (ATCC16404) |

|||||||

| MICa (µM) |

MBCb (µM) |

MIC (µM) |

MBC (µM) |

MIC (µM) |

MBC (µM) |

MIC (µM) |

MBC (µM) |

MIC (µM) |

MFCc (µM) |

MIC (µM) |

MFC (µM) |

|

| 3a | 62.5 ± 2.6 | 78.2 ± 2.1 | 93.8 ± 1.2 | 156.3 ± 2.7 | 187.5 ± 2.7 | 250 ± 5.3 | 125 ± 3.3 | 187.5 ± 2.1 | 125 ± 3.0 | 156.3 ± 1.8 | Nil | Nil |

| 3b | 31.2 ± 1.1 | 31.2 ± 1.5 | 46.7 ± 0.7 | 62.5 ± 1.1 | 156.3 ± 1.5 | 234.7 ± 2.8 | 31.2 ± 1.9 | 62.5 ± 1.7 | 93.8 ± 1.3 | 125 ± 2.4 | 250 ± 3.3 | 281.3 ± 2.7 |

| 3c | 62.5 ± 1.3 | 93.8 ± 1.3 | 187.5 ± 2.7 | 250 ± 2.2 | 125 ± 3.7 | 187.5 ± 3.3 | 93.8 ± 3.1 | 156.3 ± 3.4 | 125 ± 2.2 | 140.6 ± 1.4 | 187.5 ± 2.0 | 250 ± 4.0 |

| 3d | 93.8 ± 1.1 | 125 ± 3.3 | 31.2 ± 1.8 | 46.7 ± 0.9 | 187.5 ± 2.5 | 250 ± 4.7 | 156.3 ± 3.7 | 218.7 ± 5.2 | 125 ± 1.3 | 125 ± 2.1 | Nil | Nil |

| 3e | 125 ± 3.1 | 156.3 ± 2.5 | 156.3 ± 3.6 | 234.7 ± 2.4 | Nil | Nil | 156.3 ± 4.6 | 156.3 ± 1.6 | 156.3 ± 2.4 | 218.7 ± 2.6 | Nil | Nil |

| 3f | 15.6 ± 0.8 | 31.2 ± 1.7 | 78.1 ± 1.5 | 125 ± 2.7 | 187.5 ± 2.8 | 187.5 ± 3.6 | 31.2 ± 0.5 | 46.7 ± 1.6 | 156.3 ± 2.8 | 156.3 ± 0.7 | 218.7 ± 3.2 | 218.7 ± 2.8 |

| 3g | 31.2 ± 1.1 | 46.7 ± 0.8 | 46.7 ± 1.2 | 62.5 ± 1.7 | 156.3 ± 2.6 | 218.7 ± 5.1 | 93.8 ± 0.9 | 93.8 ± 2.2 | 125 ± 3.6 | 187.5 ± 1.4 | Nil | Nil |

MICa = Minimum inhibitory concentration, MBCb = Minimum bactericidal concentration. MFCc = Minimum fungicidal concentration.

3.3.1. Biocidal activity against SRB

In petroleum industry, some processes may face an obstacle from SRB. These bacteria produce hydrogen sulfide which causes many problems including environmental pollution, equipment corrosion and crude oil souring. Therefore, mitigation of the SRB is necessary to control all of these issues. Table 4 shows the activity of the synthesized cationic compounds against SRB (Desulfovibrio sapovorans ATCC 33892) exhibiting strong killing effect and the activities are correlated to their structures [15]. Among the investigated compounds, 3d and 3g exhibited significant biocidal activity, where they diminished the count of bacterial cells from 2.8 × 106 cells/mL to Nil at the studied concentration (5 mg/mL). The other tested compounds showed weak anti-SRB activity.

Table 4.

Anti-SRB activity of the synthesized cationic surfactant-sulfonamide conjugates against Desulfovibrio sapovorans ATCC 33892 through serial dilution method.

| Compd. No. | 3a | 3b | 3c | 3d | 3e | 3f | 3g | Blank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial count (cells/mL) | 0.36 ± 0.08 | 0.73 ± 0.12 | 0.73 ± 0.14 | Nila | 0.36 ± 0.07 | 1.1 ± 0.23 | Nil | > 2.8 × 106 |

highly significant against SRB.

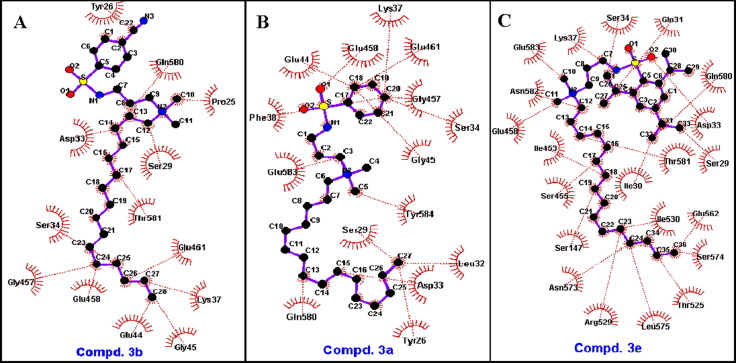

3.4. Binding modes with RNA polymerase protein

To explore and investigate the mechanism by which these compounds type may acquire its activity against the tested microbes, a molecular docking study was established for the most/the least active surfactant-sulfonamide conjugates (3a, 3b and 3e) with numerous receptors. The cationic parts of conjugates were docked into the active sites of E. coli RNA polymerase (PDB ID: 4kn4), threonine synthase from B. subtilis ATCC 6633 (PDB ID: 6nmx) and cyclooxygenase-2 (PDB ID: 6cox).

For the binding with RNA polymerase, compound 3b with cyano group exhibited the strongest binding (BE = −4.19 Kcal/mol), while compound 3e showed almost no binding (BE > +300 Kcal/mol). Removing the cyano group (compound 3a) results in weakening the binding. The 2D-binding (Fig. 6 ) indicates that only hydrophobic interactions (no hydrogen-bonding) are responsible for such binding. Both compounds 3b and 3a bind to number of amino acids residues in the active site (Fig. 6A,B) greater than that of compound 3e (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Representative hydrophobic interactions of E. coli RNA polymerase with A) compound 3b, B) compound 3a, and C) compound 3e analyzed by LigPlot + software.

Like 2D-binding, the in-depth 3D-binding modes suggest the excellent fitting of 3b and good fitting of 3a to the binding pocket of the polymerase protein (Fig. 7 A,B and Figure S2). However, compound 3e with its three bulky isopropyl groups appeared in a compact form and hence weak fitness to the protein pocket (Fig. 7C). Comparing the binding parameters (Fig. 7D), beyond the binding strength, the inhibition concentration (IC) of 3b is highly better than that of 3a. This can give a good illustration for the difference in antimicrobial activities of these compounds and confirm that small groups (especially at position-4) are favored for the bioactivity.

Fig. 7.

In-depth ligand-protein interaction profile for A) compound 3b, B) compound 3a, and C) compound 3e against E. coli RNA polymerase. D) Binding energy (BE, Kcal/mol), inhibition concentration (IC, mM) and ligand efficiency (LE) for compounds 3a and 3b.

Turning to threonine synthase, the most active compounds 3b and 3f against B. subtilis showed almost no binding affinity to the entire protein and this was clear from their positive binding parameters (Figure S3 and Table S1). Moreover, subjecting 3b for docking into the active site of a third receptor (cyclooxygenase-2) proves the weak binding ability that cannot be considered the main reason for activity (Figure S4 and Table S1).

Finally, the adequacy of the used docking protocol was tested through redocking of the conjugate 3b into the active pocket of E. coli RNA polymerase protein. It was found that the RMSD value between the ligand before and after redocking equals 1.28 Å confirming the convenience of our protocol.

4. Conclusions

The present study reported the synthesis of novel bioactive cationic surfactants bearing sulfonamide group (3a-g) via interaction between n-hexadecyl iodide with the as-prepared sulfonamide derivatives (2a-g), and elucidation of their structures by various spectroscopic analyses. It also included the evaluation of their petro-collecting/dispersing capacities, antimicrobial activities, and biocidal activity against SRB. According to the indices of the former, compound 3g (as 2.5% aq. solution) behaves as a petro-dispersant in all utilized waters (KD = 91.22% in distilled, 93.56% in fresh and 95.33% in sea waters). In some cases, the same compound showed different behavior upon changing the water type. Interestingly, the diluted form of 3f exhibited a dual effect; as a petro-collecting in both distilled and fresh waters (Kmax = 32.01 and 29.76, respectively) however, as a petro-dispersing in seawater (KD = 91.22%). With respect to activity toward microbes, conjugates 3b and 3f displayed the strongest activity against E. coli and B. subtilis with values comparable to the tested reference drugs. Regarding the anti-SRB activity, 3g was found to cause a huge reduction in the bacterial count. Furthermore, the molecular docking study showed a strong correlation between RNA polymerase binding with bioactivity against microbes. As experimentally found (inhibition zone diameter = 18 mm) and theoretically approved (BE = −4.19 Kcal/mol), compound 3b possesses the highest antibacterial activity against E. coli. This multi-side study indicates that simple substituents on the benzene ring are favored for the activity.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ahmed H. Tantawy: Conceptualization, Supervision, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Mahmoud M. Shaban: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Hong Jiang: Conceptualization, Supervision, Investigation, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. : . Man-Qun Wang: Conceptualization, Supervision, Investigation, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Hany I. Mohamed: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFE0113900) and Huazhong Agricultural University, Talent Young Scientist Program (Grant No. 42000481-7).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116068.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Lee S., Lee J., Yu H., Lim J. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2016;38:157–166. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasanov E.E., Rahimov R.A., Abdullayev Y., Asadov Z.H., Ahmadova G.A., Isayeva A.M., Ahmadbayova S.F., Zubkov F.I., Autschbach J. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020;86:123–135. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danish M., Ashiq M., Nazar M.F. J. Disper. Sci. Technol. 2017;38:837–844. [Google Scholar]

- 4.García M.T., Campos E., Sanchez-Leal J., Ribosa I. Chemosphere. 1999;38:3473–3483. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(98)00576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.A.S. Kalgutkar, R. Jones, A. Sawant, in Sulfonamide as an Essential Functional Group in Drug Design, D.A. Smith Ed., pp. 210-274, Royal Society of Chemistry, (2010).

- 6.Uehara T., Minoshima Y., Sagane K., Sugi N.H., Mitsuhashi K.O., Yamamoto N., Kamiyama H., Takahashi K., Kotake Y., Uesugi M., Yokoi A., Inoue A., Yoshida T., Mabuchi M., Tanaka A., Owa T. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13:675–680. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel T.S., Bhatt J.D., Dixit R.B., Chudasama C.J., Patel B.D., Dixit B.C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2019;27:3574–3586. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mistry B.D., Desai K.R., Intwala S.M. Indian J. Chem. 2015;54B:128–134. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ugwu D.I., Ezema B.E., Eze F.U., Ugwuja D.I. Int. J. Med. Chem. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/614808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghorab M.M., Bashandy M.S., Alsaid M.S. Acta Pharm. 2014;64:419–431. doi: 10.2478/acph-2014-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chandak H.S. Der Pharm. Chem. 2012;4:1054–1057. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahtab R., Srivastava A., Gupta N., Tripathi A. J. Chem. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2014;7:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chauhan J., Yu W., Cardinale S., Opperman T.J., MacKerell A.D., Jr, Fletcher S., de Leeuw E.P. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2020;14:567–574. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S226313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikpa C.B.C., Onoja S.O., Okwaraji A.O. Acta Chem. Malaysia. 2020;4:55–57. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aiad I., Shaban S.M., Tawfik S.M., Khalil M.M.H., El-Wakeel N. J. Mol. Liq. 2018;266:381–392. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daly R.A., Borton M.A., Wolfe R.A., Welch S.A., Krzycki J.A., Cole D.R., Wilkins M.J., Marcus D.N., Mouser P.J., Hoyt D.W., Trexler R.V., Kountz D.J., MacRae J.D., Wrighton K.C. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;1:1–9. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viani F., Rossi B., Panzeri W., Merlini L., Martorana A.M., Polissi A., Galante Y.M. Tetrahedron. 2017;73:1745–1761. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Negm N.A., Tawfik S.M. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2014;20:4463–4472. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tawfik S.M. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015;28:171–183. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fatma N., Panda M., Kabir-ud-Din, Beg M. J. Mol. Liq. 2016;222:390–394. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Labena A., Hegazy M.A., Horn H., Muller E. J. Surfact. Deterg. 2014;17:419–431. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Labena A., Hegazy M.A., Sami R.M., Hozzein W.N. Molecules. 2020;25:1348. doi: 10.3390/molecules25061348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Migahed M.A., Negm N.A., Shaban M.M., Ali T.A., Fadda A.A. J. Surfact. Deterg. 2016;19:119–128. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jadhav M., Kalhapure R.S., Rambharose S., Mocktar C., Govender T. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017;47:405–414. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu J., Gao H., Shi D., Yang Y., Zhang Y., Zhu W. J. Mol. Liq. 2020;299 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaban S.M., Saied A., Tawfik S.M., Abd-Elaal A., Aiad I. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2013;19:2004–2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Labena A., Hegazy M.A., Horn H., Müller E. RSC Adv. 2016;6:42263–42278. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rbaa M., Abousalem A.S., Rouifi Z., Benkaddour R., Dohare P., Lakhrissi M., Warad I., Lakhrissi B., Zarrouk A. Surf. Interfaces. 2020;19 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agamy E. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2012;75:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Saeed S.M., Farag R.K., Abdul-Raouf M.E., Abdel-Azim A.-A.A. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Po. 2008;57:860–877. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cojocaru C., Macoveanu M., Cretescu I. Colloid Surface A. 2011;384:675–684. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhattacharyya S., Klerks P.L., Nyman J.A. Environ. Pollut. 2003;122:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(02)00294-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wrenn B.A., Virkus A., Mukherjee B., Venosa A.D. Environ. Pollut. 2009;157:1807–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riazi M.R., Al-Enezi G.A. Chem. Eng. J. 1999;73:161–172. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peeters F., Kipfer R., Achermann D., Hofer M., Aeschbach-Hertig W., Beyerle U., Imboden D.M., Rozanski K., Fröhlich K. Deep Sea Res. Part I: Oceanographic Res. Papers. 2000;47:621–654. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaaseidnes K., Turbeville J. Pure Appl. Chem. 1999;71:95–101. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jung S.W., Kwon O.Y., Joo C.K., Kang J.-H., Kim M., Shim W.J., Kim Y.-O. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012;217–218:338–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolancılar H. J. Am. Oil. Chem. Soc. 2004;81:597–598. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abo-Riya M., Tantawy A.H., El-Dougdoug W. J. Mol. Liq. 2016;221:642–650. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asadov Z.H., Rahimov R.A., Salamova N.V. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2011;89:505–511. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Asadov Z.H., Tantawy A.H., Zarbaliyeva I.A., Rahimov R.A. J. Oleo Sci. 2012;61:621–630. doi: 10.5650/jos.61.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feairheller S.H., Bistline R.G., Jr, Bilyk A., Dudley R.L., Kozempel M.F., Haas M.J. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1994;71:863–866. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohamed H.I., Basyouni M.Z., Khalil A.A., Hebash K.A., Tantawy A.H. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2021;18:265–274. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tantawy A.H., Mohamed H.I., Khalil A.A., Hebash K.A., Basyouni M.Z. J. Mol. Liq. 2017;236:376–384. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaky R.R., Ibrahim K.M., Abou El-Nadar H.M., Abo-Zeid S.M. Spectrochim. Acta A. 2015;150:40–53. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2015.04.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller R.A., Walker R.D., Carson J., Coles M., Coyne R., Dalsgaard I., Gieseker C., Hsu H.M., Mathers J.J., Papapetropoulou M., Petty B., Teitzel C., Reimschuessel R. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2005;64:211–222. doi: 10.3354/dao064211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.ASTM D4412–84, in Standard Test Methods for Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria in Water and Water-Formed Deposits. ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rizvi S.M.D., Shakil S., Haneef M. EXCLI J. 2013;12:831–857. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mooers B.H. Protein Sci. 2016;25:1873–1882. doi: 10.1002/pro.2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laskowski R.A., Swindells M.B. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:2778–2786. doi: 10.1021/ci200227u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fingas M., Brown C.E. Sensors. 2018;18:91. doi: 10.3390/s18010091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gray J.L., Kanagy L.K., Furlong E.T., Kanagy C.J., McCoy J.W., Mason A., Lauenstein G. Chemosphere. 2014;95:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Silhavy T.J., Kahne D., Walker S. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oblak E., Piecuch A., Krasowska A., Luczynski J. Microbiol. Res. 2013;168:630–638. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.