Abstract

Background/Aims

Prokinetics can be used for treating patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), who exhibit suboptimal response to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment. We conducted a systematic review to assess the potential benefits of combination treatment with PPI plus prokinetics in GERD.

Methods

We searched PubMed, the Cochrane Library, and EMBASE for publications regarding randomized controlled trials comparing combination treatment of PPI plus prokinetics to PPI monotherapy with respect to global symptom improvement in GERD (until February 2020). The primary outcome was an absence or global symptom improvement in GERD. Adverse events and quality of life (QoL) scores were evaluated as secondary outcomes using a random effects model. Quality of evidence was rated using Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE).

Results

This meta-analysis included 16 studies involving 1446 participants (719 in the PPI plus prokinetics group and 727 in the PPI monotherapy group). The PPI plus prokinetics treatment resulted in a significant reduction in global symptoms of GERD regardless of the prokinetic type, refractoriness, and ethnicity. Additionally, treatment with PPI plus prokinetics for at least 4 weeks was found to be more beneficial than PPI monotherapy with respect to global symptom improvement. However, the QoL scores were not improved with PPI plus prokinetics treatment. Adverse events observed in response to PPI plus prokinetics treatment did not differ from those observed with PPI monotherapy.

Conclusions

Combination of prokinetics with PPI treatment is more effective than PPI alone in GERD patients. Further high-quality trials with large sample sizes are needed to verify the effects based on prokinetic type.

Keywords: Gastroesophageal reflux, Gastrointestinal agents, Proton pump inhibitors

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common gastrointestinal disorder with an estimated worldwide prevalence of between 8% and 33%.1 Following the introduction of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) into the drug market, PPIs were used as the treatment of choice for GERD. However, approximately 30% of the GERD patients treated with the standard doses of PPIs continue to manifest symptoms.2 Consequently, the use of other adjunctive treatments, including histamine H2 receptor antagonists, prokinetics, alginate, and surgery have been suggested in several guidelines.3-8 However, the evidences supporting the efficacy of such treatments are currently weak. Prokinetics have traditionally been found to improve gastrointestinal motility, and therefore have been recommended as a first-line treatment in functional dyspepsia patients with a postprandial distress subtype.9 Furthermore, several studies have reported that when used in combination with PPIs, prokinetics show additional benefits with respect to global symptom improvement in patients with GERD.10-12 In the Asia-Pacific region, the consensus regarding the management of GERD has indicated that the uses of prokinetics as an adjunctive therapy with PPIs may have a beneficial effect on the treatment of PPI-refractory GERD symptoms, although the effect appears to be modest.13,14 In Asia, the most commonly used prokinetics are mosapride, itopride, and domperidone. However, another prokinetic agent, cisapride, has been withdrawn from the market owing to its association with fatal heart arrhythmia. Furthermore, although previous studies have shown that mosapride, a selective 5-hydroxytryptamine 4 receptor agonist, can reduce the episodes of acid reflux and enhance esophageal clearance,15,16 another clinical trial has reported no additional effect of mosapride when used in combination with PPIs for treating GERD.12 Accordingly, for clarifying the efficacy of prokinetics for the treatment of patients with GERD, we conducted a systematic review of studies that have used prokinetics as an adjunctive therapy for the treatment of GERD.

Methods

Literature Search Strategy

In this study, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of the combination treatment with PPI plus prokinetics and PPI monotherapy on GERD symptoms based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) principles.17 PubMed, Cochrane Library, and EMBASE databases (from inception to February 2020) were searched independently by 2 authors of the present review (D.H.J. and C.W.H.), using the following search string (Supplementary Data). Cited references in published studies were manually and repetitively searched to identify other relevant studies. The latest date for updating our search was February 14, 2020.

Study Selection

In the first stage of study selection, the title and abstract of articles returned by our keyword search were scrutinized to rule out articles deemed irrelevant with respect to the purpose of the present analysis. Thereafter, we screened the full texts of all selected studies in accordance with our stated inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) a diagnosis of GERD, (2) randomized controlled trials with parallel design, (3) comparison of PPI plus prokinetics therapy with PPI monotherapy for the treatment of GERD, (4) investigations of adults aged ≥ 18 years; and (5) no evidence of disorder (organic, metabolic, or drug-induced) to explain the symptoms. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies without a detailed description of the diagnosis of GERD, (2) studies in which the objective was to evaluate herbal prokinetic agents; (3) studies in which the treatment duration was less than 7 days, (4) publication in a language other than English, or (5) abstract-only publications.

Data Extraction

Two authors (D.H.J. and C.W.H.) of the present review independently extracted data from the included studies using a pre-data extraction form. The titles and abstracts of all included studies were reviewed to exclude irrelevant publications. Discrepancies in data interpretation were resolved by discussion, re-review of studies, or when necessary, consultation with the third author (S.K.L.) of this review. The data collected included the following: (1) participant characteristics, including demographics, recruitment source, diagnostic criteria used by the study authors, and GERD subtype; (2) interventions details, including the name of the PPI or prokinetic, dose, and treatment duration; (3) and improvement in reflux symptoms before and after the intervention, including the number of patients with reflux symptoms, quality of life (QoL), and adverse events (AEs). We defined refractory GERD as patients who complained of GERD symptoms despite with once daily dose of PPI for at least 8 weeks.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome was a global symptom improvement of GERD. If more than 1 definition of global symptom improvement was identified, we assessed the most stringent definition of global symptom improvement. Although we primarily evaluated patient reported outcomes after treatment, if this information was not available, we used overall symptom assessment by the physician or researcher. If the global symptoms of GERD were not reported, we used heartburn or reflux improvement as the outcome measure. Secondary outcomes were QoL and AEs.

Methodological Quality

All trials were assessed using Cochrane’s “Risk of Bias (RoB)” tool, which includes the following domains: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data addressed over the short and long terms (attrition bias); selective reporting (reporting bias); and other biases. Two authors (D.H.J. and C.W.H.) independently assessed the methodological quality of the included studies. Any disagreement between the 2 evaluators was resolved by discussion.

Statistical Methods

For data analysis, we used Review Manager version 5.3 (RevMan for Windows 7; the Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). The Mantel–Haenszel random-effect model was used for binary end points, and the inverse variance method was used for continuous outcomes. In addition, we evaluated subgroup analyses according to the following criteria: GERD based on endoscopic findings (erosive reflux disease (ERD) vs non-erosive reflux disease (NERD), refractory GERD vs non-refractory GERD, study population (Eastern vs Western), length of treatment (≤ 4 weeks vs > 4 weeks), and studies assessed as low RoB vs unclear RoB. To determine heterogeneity, we used the I2 test developed by Higgins.18 A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The levels of evidence in each outcome were evaluated based on the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach with the consensus of 2 authors (D.H.J. and C.W.H.).

Results

Study Selection

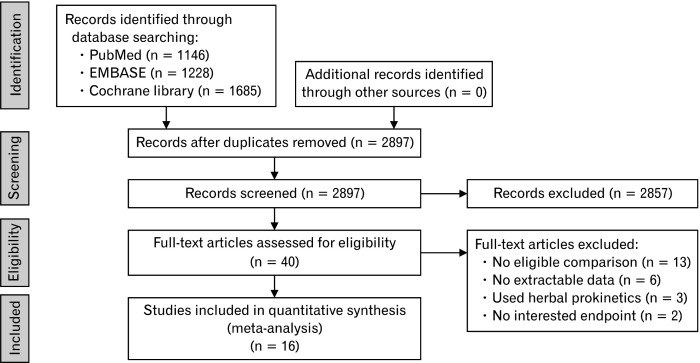

Our primary literature search retrieved a total of 2897 studies, of which 2857 were rejected based on the scrutiny of the title and abstract. The remaining 40 articles were subjected to full reviews, and after assessing the eligibility, we excluded a further 24 articles (Fig. 1), leaving 16 articles10,19-33 for meta-analysis (Table 1). These 16 studies presented details on 1446 participants, among whom 719 were included in the PPI plus prokinetics group (mosapride,10,21,22,24,25,29-32,34 domperidone,23,27,28 revexepride,19,20 and acotiamide26) and 727 were included in the PPI monotherapy group. Among these 16 studies, half (8 studies) were rated as having an unclear RoB, whereas among the remaining eight studies, 6 and 2 trials were assessed as having a low and high RoB, respectively. The authors’ assessments regarding each RoB domain in the respective trials are shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Authors | n | Male (n) | Age (mean, yr) | Region of study | Outcome measures |

Type of outcome | GERD subtype I (n) | GERD subtype II | PPI | Prokinetic | Treatment duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yamashita et al,26 2019 | 70 | 33 | PPI: 70.0 PPI + Prokinetic: 63.0 |

Eastern (Japan) | Overall treatment effect | Binary | NERD: 55 ERD: 15 |

Refractory GERD | NA | Acotimide 100 mg tid | 2 wk |

| Xiao and Mao,32 2019 | 90 | 53 | PPI: 39.9 PPI + Prokinetic: 40.6 |

Eastern (China) | RDQ | Continuous | NA | Non-refractory GERD | Omeprazole 20 mg bid | Mosapride 5 mg tid | 12 wk |

| Sirinawasatien and Kantathavorn,33 2019 | 44 | 13 | PPI: 53.1 PPI + Prokinetic: 49.2 |

Eastern (Thailand) | FSSG | Continuous | NA | Refractory GERD | Omeprazole20 mg qd | Mosapride 5 mg tid | 4 wk |

| Puranik et al,27 2018 | 80 | 55 | NA | Eastern (India) | FSSG | Continuous | NA | Non-refractory GERD | Pantoprazole 40 mg qd | Domperidone 30 mg qd | 2 wk |

| Marakhouski et al,28 2017 | 100 | 27 | PPI: 47.1 PPI + Prokinetic: 45.7 |

Western (Belarus) | GERD-Q | Binary | NA | Non-refractory GERD | Omeprazole 20 mg bid | Domperidone 30 mg bid | 8 wk |

| Lee et al,29 2017 | 116 | 78 | PPI: 55.8 PPI + Prokinetic: 54.9 |

Eastern (Korea) | Total GERD symptom score | Binary | ERD: 116 | Non-refractory GERD | Esomeprazole 40 mg qd | Mosapride 5 mg tid | 8 wk |

| Shaheen et al,19 2015 | 240 | 94 | PPI: 46.2 PPI + Prokinetic: 49.2 |

Western (USA) | GERD-Q | Binary | NA | Refractory GERD | NA | Revexepride0.5 mg tid | 8 wk |

| Tack et al,20 2015 | 60 | 25 | PPI: 45.8 PPI + Prokinetic: 43.8 |

Western(European countries) | PAGI-SYM | Continuous | NA | Refractory GERD | NA | Revexepride0.5 mg tid | 4 wk |

| Yamaji et al,21 2014 | 50 | 13 | PPI: 61.7 PPI + Prokinetic: 65.0 |

Eastern (Japan) | FSSG | Continuous | NA | Non-refractory GERD | Omeprazole10 mg qd | Mosapride 5 mg tid | 4 wk |

| Wang,30 2014 | 116 | NA | NA | Eastern (China) | GERD-Q | Binary | NA | Non-refractory GERD | Esomeprazole 20 mg bid | Mosapride 10 mg tid | 8 wk |

| Cho,22 2013 | 43 | 24 | PPI: 43.0 PPI + Prokinetic: 49.0 |

Eastern (Korea) | Reflux-symptoms questionnaire | Binary | NA | Non-refractory GERD | Esomeprazole 40 mg qd | Mosapride 5 mg tid | 4 wk |

| Lim,31 2013 | 30 | 16 | PPI: 53.3 PPI + Prokinetic: 48.5 |

Eastern (Korea) | Questionnaires about gastroesophageal reflux symptoms | Continuous | NA | Non-refractory GERD | Pantoprazole 40 mg qd | Mosapride 5 mg tid | 8 wk |

| Ndraha,23 2011 | 60 | 20 | PPI: 40.4 PPI + Prokinetic: 44.3 |

Eastern (Indonesia) | FSSG | Continuous | NA | Non-refractory GERD | Omeprazole 20 mg bid | Domperidone 10 mg bid | 2 wk |

| Miwa,10 2011 | 192 | 72 | PPI: 52.2 PPI + Prokinetic: 52.1 |

Eastern (Japan) | Patient’s reflux symptoms | Binary | NERD:192 | Non-refractory GERD | Omeprazole10 mg qd | Mosapride 5 mg tid | 4 wk |

| Hsu et al,24 2010 | 94 | 48 | PPI: 47.0 PPI + Prokinetic: 47.0 |

Eastern (Taiwan) | FSSG | Binary | ERD:94 | Non-refractory GERD | Lansoprazole30 mg qd | Mosapride 5 mg tid | 8 wk |

| Madan et al,25 2004 | 61 | 40 | PPI: 34.7 PPI + Prokinetic: 36.5 |

Eastern (India) | Patient’s reflux symptoms | Binary | ERD:32 NERD: 29 |

Non-refractory GERD | Pantoprazole 40 mg bid | Mosapride 5 mg tid | 8 wk |

GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; NERD, non-erosive reflux disease; ERD, erosive reflux disease; RDQ, reflux disease questionnaire; FSSG, frequency scale for the symptom of GERD; GERD-Q, gastroesophageal reflux disease questionnaire; PAGI-SYM, patient assessment of upper gastrointestinal symptom severity index; NA, not available; qd, once a day; bid, twice a day; tid, 3 times a day.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

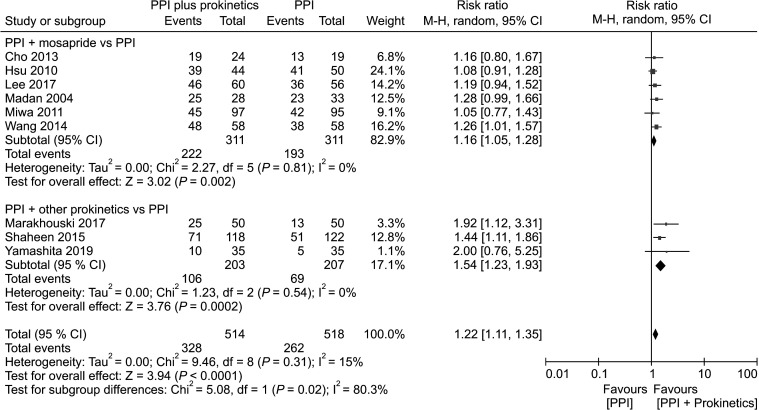

Nine studies indicated global symptom improvement of GERD in terms of a binary outcome (yes or no),10,19,22,24-26,28-30 whereas the other 7 studies20,21,23,27,31-33 reported continuous measures (ie, a change in symptom improvement). Among the 9 studies that rated global symptom improvement of GERD in terms of a binary outcome, the average percentage symptom improvement was 63.8% in the PPI plus prokinetics group, compared with 50.6% in the PPI monotherapy group. The PPI plus prokinetics treatment was found to significantly reduce the global symptoms of GERD (risk ratio [RR] of reflux symptoms resolution, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.35; P < 0.0001; number needed to treat [NNT], 7; 95% CI, 5 to 13 with low heterogeneity [I2 15%]). With respect to individual prokinetics, the data were as follows: mosapride (RR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.28; NNT, 11; 95% CI, 5 to 51), and prokinetics other than mosapride (RR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.23 to 1.93; NNT, 5; 95% CI, 4 to 11) (Fig. 2). In the seven trials in which the primary outcome was reported as a continuous measure (change in symptom improvement), subgroup analyses also showed a significant improvement in the PPI plus prokinetics group (pooled standardized mean difference [SMD], 1.38; 95% CI, 0.42 to 2.34) with high heterogeneity (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot comparing proton pump inhibitor (PPI) plus prokinetics and PPI monotherapy in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease in term of symptom improvement, subgrouped by individual prokinetic.

Pooled data from 2 studies (n = 300) which reported the QoL scores revealed no significant differences in the QoL scores between patients receiving PPI plus prokinetics treatment and PPI monotherapy (SMD, 1.22; 95% CI, -1.76 to 4.20; I2, 99%; P = 0.420). Pooled data from 8 separate studies (n = 725) which reported AEs including 3 different prokinetics (mosapride, domperidone, and acotiamide) revealed that AEs were detected in 7.9% of patients in the PPI plus prokinetics group compared with 9.2% of patients in the PPI monotherapy group. There was no association between a specific prokinetic and any particular AE (RR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.57 to 1.45; I2, 0%; P = 0.680).

Subgroup Analyses

Erosive reflux disease versus non-erosive reflux disease

Evaluation of the outcomes based on GERD subtype determined by endoscopic findings was performed in 9 studies. Analysis of 4 studies involving 257 participants with the ERD subtype showed no significant improvement in patients in the PPI plus prokinetics group with moderate heterogeneity. Three studies that evaluated patients with the NERD subtype (n = 276) revealed no significant difference between the combination treatment with PPI plus prokinetics and PPI monotherapy groups with respect to relieving the symptoms of reflux, and showed that there was significant heterogeneity among these trials. Four trials involving 499 participants did not differentiate between GERD subtypes. Subgroup analyses in these trials indicated the efficacy of PPI plus prokinetics therapy at reducing global GERD symptoms (RR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.57; NNT, 5; 95% CI, 3 to 9) with low heterogeneity (Supplementary Fig. 3).

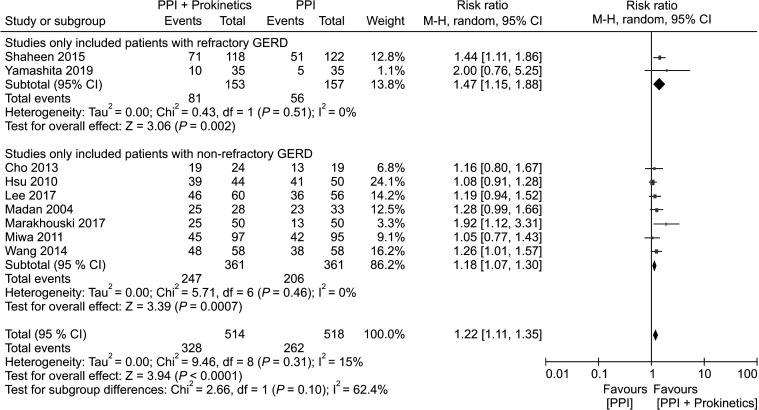

Refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease versus non-refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease

Analysis of 2 studies involving 310 participants with refractory GERD revealed a significant global symptom improvement in the PPI plus prokinetics group (NNT, 5; 95% CI, 3 to 15) with low heterogeneity. Seven studies evaluated patients with non-refractory GERD (n = 722) and identified a greater likelihood of global symptom improvement in patients receiving PPI plus prokinetics treatment compared with those receiving PPI monotherapy (NNT, 8; 95% CI, 5 to 22) with no significant heterogeneity (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot comparing proton pump inhibitor (PPI) plus prokinetics and PPI monotherapy in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease in term of symptom improvement, subgrouped by refractoriness of gastroesophageal reflux disease.

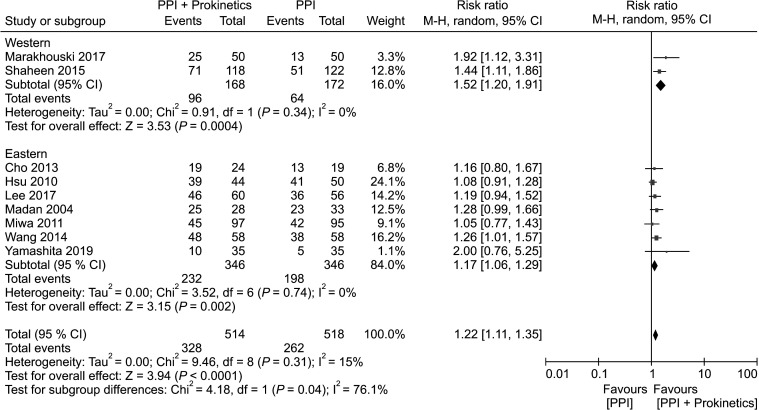

Region of study (Western versus Eastern)

Two trials with 340 participants were conducted in Western countries (the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Poland, Romania, the USA, and Belarus), whereas 7 studies involving 692 participants were conducted in Asia (Korea, Japan, Taiwan, India, and China). Studies from both regions indicated the efficacy of PPI plus prokinetics at reducing global GERD symptoms with low heterogeneity (Fig. 4). However, the NNT was found to be 2-fold higher in the Eastern population (10; 95% CI, 5 to 37) than that in patients from Western countries (5; 95% CI, 3 to 10).

Figure 4.

Forest plot comparing proton pump inhibitor (PPI) plus prokinetics and PPI monotherapy in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease in term of symptom improvement, subgrouped by region of study.

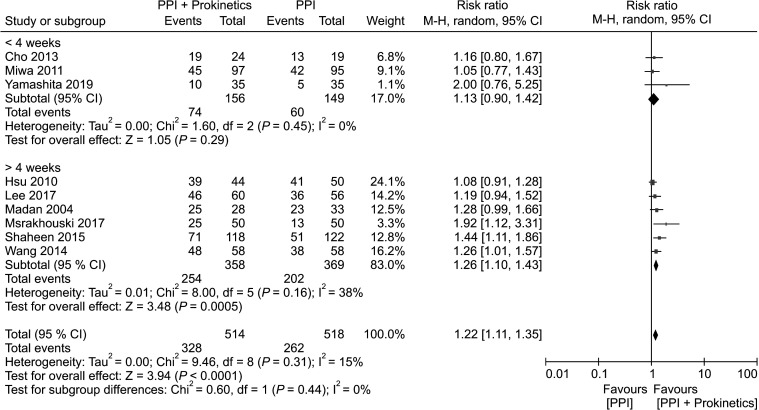

Length of treatment

Three trials that assessed the efficacy of treatment (PPI plus prokinetics treatment or PPI monotherapy) for 4 weeks or less, and the included follow-up in 305 individuals revealed no significant difference between the PPI plus prokinetics and PPI monotherapy groups with respect to relieving the symptoms of GERD, and there was a low heterogeneity among these trials. In contrast, among patients receiving treatment for at least 4 weeks, there was a significant reduction in GERD symptoms in patients treated with PPI plus prokinetics compared to those treated with PPI monotherapy, (n = 727) (NNT 6, 95% CI, 4 to 10) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot comparing proton pump inhibitor (PPI) plus prokinetics and PPI monotherapy in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease in term of symptom improvement, subgrouped by length of treatment.

Risk of bias (low versus unclear)

Five trials with a low RoB (n = 533) revealed the significant efficacy of combination treatment with PPI plus prokinetics at improving global GERD symptoms. Similarly, 4 studies with 499 individuals having an unclear RoB revealed significant differences between the PPI plus prokinetics and PPI monotherapy arms, with a low heterogeneity between the studies (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Quality of Evidence

On comparing the efficacy of the PPI plus prokinetics treatment with that of the PPI monotherapy, GRADE assessment of the quality of evidence indicated a moderate effect on reducing the global GERD symptoms. This can be attributed to concerns regarding the RoB in primary outcome assessments relating to trial design (eg, unexplained random sequence generation, allocation concealment, and blinding method for participants, medical personnel, and outcome assessors). However, the quality of evidence for QoL was found to be very low, while for AEs it was low (Table 2).

Table 2.

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation Assessment for Proton Pump Inhibitor Plus Prokinetic Versus Proton Pump Inhibitor Monotherapy Studies

| PPI plus prokinetic compare to PPI for GERD | ||||||

| Patient: GERD | ||||||

| Setting: out patients | ||||||

| Intervention: PPI plus prokinetic | ||||||

| Comparison: PPI monotherapy | ||||||

| Outcome | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with PPI | Risk with PPI plus prokinetic | |||||

| Symptom improvement | 51 per 100 (46 to 56) | 64 per 100 (59 to 69) | RR 1.22 (1.11-1.35) | 1032 (9 RCTs) | Moderatea | Higher scores mean better quality of life |

| Change of QoL scores | - | - | - | 300 (2 RCTs) | Very lowa,b,c | |

| Adverse events | 11 per 100 (6 to 16) | 10 per 100 (5 to 15) | RR 0.91 (0.57-1.45) | 725 (8 RCTs) | Lowa,b | |

aDowngraded one level due to study limitations: most information were obtained from studies with unclear risk of bias.

bDowngraded one levels due to imprecision (small number of included trials).

cDowngraded one level due to serious inconsistency: significant heterogeneity.

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE)––working group grades of evidence:

- High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

- Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

- Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

- Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

PPI, proton pump inhibitor; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; RR, risk ratio; RCTs, randomized controlled trials; QoL, quality of life.

Discussion

GERD is a complex disease characterized by a multifactorial pathogenesis. Previously, 60-70%, 20-30%, and 6-10% improvement in the symptoms of GERD in response to PPI treatment has been reported in patients with NERD, ERD, and Barrett’s esophagus, respectively.2 Given this variable efficacy, agents other than PPIs, including histamine H2 receptor antagonists, alginate, baclofen, and prokinetics, are often used for treating patients with GERD.34 Although the use of prokinetics in North America is generally limited, these agents are widely used in patients with functional dyspepsia in Asia. However, evidence regarding the efficacy of prokinetics for treating patients with GERD is controversial.

The present systematic review indicate that compared with PPI monotherapy, combination treatment with PPI plus prokinetics can improve GERD symptoms with a moderate NNT of 7 and low heterogeneity. In addition, although only 2 trials were assessed, our analysis indicated that in patients with PPI-refractory GERD, PPI plus prokinetics treatment showed beneficial effects with low heterogeneity with respect to global symptom improvement of GERD compared with that observed in response to PPI monotherapy. Our analysis identified mosapride, domperidone, acotiamide, and revexepride as effective prokinetics in GERD patients when combined with PPI therapy. In contrast to the results of a previous meta-analysis,12 our findings on PPI plus mosapride treatment indicated the beneficial effects of prokinetics with respect to reducing GERD symptoms. This disparity in assessments can probably be explained by our inclusion of 2 studies, involving 232 participants that were published subsequent to the publication of the aforementioned meta-analysis,29,30 in which combination treatment with PPI plus mosapride was found to result in a significant global symptom improvement of GERD. Mosapride has the effect of reducing the acid reflux by modulating esophageal motility,16 and accordingly, mosapride combined with PPI therapy was found to be beneficial for enabling relief from GERD symptoms. However, given that the assessment of the efficacies of domperidone, acotiamide, and revexepride were represented by 1 study each, we were unable to verify whether any of these prokinetics are more effective than mosapride owing to insufficient evidence.

With respect to the region of study, trials conducted in both Western and Eastern countries have demonstrated the efficacy of combination treatment with PPI plus prokinetics at reducing GERD symptoms. Although only 2 relevant trials have been conducted in Western countries, these indicated that the patients in these countries (NNT, 5) appear to show a more pronounced response to treatment with PPI plus prokinetics treatment compared with patients in Eastern countries (NNT, 10). Although we assume that these differences in response may be associated with patient-related factors such as ethnicity, genetics, environment, and culture, additional studies in Western countries would be necessary to provide more supportive evidence in this respect.

With respect to the length of treatment, patients receiving treatment for ≤ 4 weeks appear to show no significant difference in their response to combination treatment with PPI plus prokinetics and PPI monotherapy with respect to relief from GERD symptoms. However, in patients treated for at least 4 weeks, those receiving PPI plus prokinetics therapy were found to show a greater reduction in GERD symptoms than patients receiving PPI monotherapy. Therefore, when physicians prescribe a combination of prokinetics and PPI to patients with GERD, a treatment regimen of at least 4 weeks should be recommended.

With respect to the GERD subtype determined by endoscopic findings, studies with the ERD and NERD subtype showed no significant difference between the combination treatment with PPI plus prokinetics and PPI monotherapy groups with respect to global symptom improvement. We thought that it was due to the small number of studies and more than moderate heterogeneity.

Although the present study represents the most comprehensive review to date on comparison between PPI plus prokinetics therapy and PPI monotherapy with respect to the treatment of patients with GERD, it does have certain limitations. First, half (8/16) of the studies we assessed were rated as having an unclear RoB, and thus, at best, the quality of evidence should be considered moderate. Second, given the limited availability of prokinetics in Western countries, we included only 2 relevant studies in the present meta-analysis. Third, the type of prokinetics was heterogenous. Lastly, various methods were used to evaluate primary outcome (global symptom improvement of GERD).

Despite the aforementioned limitations, this study can, nevertheless, be considered to have certain strengths. This, to the best of our knowledge, is the first meta-analysis to show the superior efficacy of PPI plus prokinetics treatment with respect to PPI monotherapy in patients with GERD. In this respect, current guidelines simply recommend the use of prokinetics in combination with PPIs in GERD patients who exhibit an insufficient response to PPI alone. However, with the exception of studies that have examined the effect of individual prokinetics, there is a lack of strong evidence regarding the efficacy of these agents in the treatment of patients with GERD when used in combination with PPI therapy. The findings of this study do, nevertheless, indicate that combination treatment with prokinetics and PPI would be beneficial in patients with GERD, particularly when this treatment lasts for at least 4 weeks.

In conclusion, the findings of this study indicate (with a moderate level of evidence) the benefits of combining prokinetics with PPI therapy for treating GERD. Although the data we assessed were insufficient to identify the type(s) of prokinetics that would be the most effective, we found that the combination of prokinetics and PPI appears to reduce the symptoms of GERD in patients who are unresponsive to PPI monotherapy.

Supplementary Materials

Note: To access the Supplementary Data and Figures mentioned in this article, visit the online version of Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility at http://www.jnmjournal.org/, and at https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm20161.

Footnotes

Financial support: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1C1C1013775).

Conflicts of interest: None.

Author contributions: In planning and/or conducting the study: Da Hyun Jung, Cheal Wung Huh, and Sang Kil Lee; collecting and/or interpreting data: Da Hyun Jung, Cheal Wung Huh, Jun Chul Park, Sung Kwan Shin, and Yong Chan Lee; drafting the manuscript: Da Hyun Jung, Cheal Wung Huh, and Sang Kil Lee; and guarantor of the article: Sang Kil Lee.

References

- 1.El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, Dent J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2014;63:871–880. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fass R, Shapiro M, Dekel R, Sewell J. Systematic review: proton-pump inhibitor failure in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease--where next? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:79–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwakiri K, Kinoshita Y, Habu Y, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for gastroesophageal reflux disease 2015. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:751–767. doi: 10.1007/s00535-016-1227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seo HS, Choi M, Son SY, Kim MG, Han DS, Lee HH. Evidence-based practice guideline for surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease 2018. J Gastric Cancer. 2018;18:313–327. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2018.18.e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sigterman KE, van Pinxteren B, Bonis PA, Lau J, Numans ME. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013:CD002095. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002095.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:308–328. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Pinxteren B, Numans ME, Bonis PA, Lau J. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD002095. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002095.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Pinxteren B, Sigterman KE, Bonis P, Lau J, Numans ME. Short-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists and prokinetics for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease-like symptoms and endoscopy negative reflux disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010: D0020:CD002095. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002095.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanghellini V, Chan FK, Hasler WL, et al. Gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380–1392. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miwa H, Inoue K, Ashida K, et al. Randomised clinical trial: efficacy of the addition of a prokinetic, mosapride citrate, to omeprazole in the treatment of patients with non-erosive reflux disease - a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:323–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyamoto M, Manabe N, Haruma K. Efficacy of the addition of prokinetics for proton pump inhibitor (PPI) resistant non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) patients: significance of frequency scale for the symptom of GERD (FSSG) on decision of treatment strategy. Intern Med. 2010;49:1469–1476. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Q, Feng CC, Wang EM, Yan XJ, Chen SL. Efficacy of mosapride plus proton pump inhibitors for treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:9111–9118. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i47.9111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fock KM, Talley N, Goh KL, et al. Asia-Pacific consensus on the management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: an update focusing on refractory reflux disease and barrett's oesophagus. Gut. 2016;65:1402–1415. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fock KM, Talley NJ, Fass R, et al. Asia-Pacific consensus on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: update. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:8–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruth M, Finizia C, Cange L, Lundell L. The effect of mosapride on oesophageal motor function and acid reflux in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:1115–1121. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200310000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruth M, Hamelin B, Röhss K, Lundell L. The effect of mosapride, a novel prokinetic, on acid reflux variables in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:35–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaheen NJ, Adler J, Dedrie S, et al. Randomised clinical trial: the 5-HT4 agonist revexepride in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease who have persistent symptoms despite PPI therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:649–661. doi: 10.1111/apt.13115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tack J, Zerbib F, Blondeau K, et al. Randomized clinical trial: effect of the 5-HT4 receptor agonist revexepride on reflux parameters in patients with persistent reflux symptoms despite PPI treatment. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:258–268. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamaji Y, Isomura Y, Yoshida S, Yamada A, Hirata Y, Koike K. Randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of mosapride plus omeprazole combination therapy to omeprazole monotherapy in gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Dig Dis. 2014;15:469–476. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho YK, Choi MG, Park EY, et al. Effect of mosapride combined with esomeprazole improves esophageal peristaltic function in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a study using high resolution manometry. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1035–1041. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2430-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ndraha S. Combination of PPI with a prokinetic drug in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Acta Med Indones. 2011;43:233–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu YC, Yang TH, Hsu WL, et al. Mosapride as an adjunct to lansoprazole for symptom relief of reflux oesophagitis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:171–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madan K, Ahuja V, Kashyap PC, Sharma MP. Comparison of efficacy of pantoprazole alone versus pantoprazole plus mosapride in therapy of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a randomized trial. Dis Esophagus. 2004;17:274–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2004.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamashita H, Okada A, Naora K, Hongoh M, Kinoshita Y. Adding acotiamide to gastric acid inhibitors is effective for treating refractory symptoms in patients with non-erosive reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:823–831. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5377-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puranik RU, Karandikar YS, Bhat SM, Patil VA. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of pantoprazole and pantoprazole plus domperidone in treatment of patients with GERD. J Clin Diagn Res. 2018;12:Ic01–Ic05. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2018/37387.12267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marakhouski KY, Karaseva GA, Ulasivich DN, Marakhouski YK. Omeprazole-domperidone fixed dose combination vs omeprazole monotherapy: a phase 4, open-label, comparative, parallel randomized controlled study in mild to moderate gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Med Insights Gastroenterol. 2017;10:1179552217709456. doi: 10.1177/1179552217709456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JY, Kim SK, Cho KB, et al. A double-blind, randomized, multicenter clinical trial investigating the efficacy and safety of esomeprazole single therapy versus mosapride and esomeprazole combined therapy in patients with esophageal reflux disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23:218–228. doi: 10.5056/jnm16100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang YP, Ji LS, Ni M, Fan HW, Sha JP. Clinical effects of esomeprazole combined with mosapride for treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. World Chin J Digestol. 2014;22:5671–5674. doi: 10.11569/wcjd.v22.i36.5671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim HC, Kim JH, Youn YH, Lee EH, Lee BK, Park H. Effects of the addition of mosapride to gastroesophageal reflux disease patients on proton pump inhibitor: a Prospective randomized, double-blind study. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:495–502. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2013.19.4.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao F, Mao J. Treatment of gastroesophageal reflux-related cough with proton pump inhibitors and prokinetic agents. Acta Medica Mediterranea. 2019;35:3131–3137. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sirinawasatien A, Kantathavorn N. Efficacy of the four weeks treatment of omeprazole plus mosapride combination therapy compared with that of omeprazole monotherapy in patients with proton pump inhibitor-refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2019;12:337–347. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S214677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gyawali CP, Fass R. Management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:302–318. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.