Abstract

Objective:

We evaluated whether memory recall following an extended (1 week) delay predicts cognitive and brain structural trajectories in older adults.

Method:

Clinically normal older adults (52–92 years old) were followed longitudinally for up to 8 years after completing a memory paradigm at baseline [Story Recall Test (SRT)] that assessed delayed recall at 30 minutes and 1 week. Subsets of the cohort underwent neuroimaging (N = 134, mean age = 75) and neuropsychological testing (Ns = 178–207, mean ages = 74–76) at annual study visits occurring approximately 15–18 months apart. Mixed-effects regression models evaluated if baseline SRT performance predicted longitudinal changes in gray matter volumes and cognitive composite scores, controlling for demographics.

Results:

Worse SRT 1-week recall was associated with more precipitous rates of longitudinal decline in medial temporal lobe volumes (p = .037), episodic memory (p = .003), and executive functioning (p = .011), but not occipital lobe or total gray matter volumes (demonstrating neuroanatomical specificity; ps > .58). By contrast, SRT 30-minute recall was only associated with longitudinal decline in executive functioning (p = .044).

Conclusions:

Memory paradigms that capture longer-term recall may be particularly sensitive to age-related medial temporal lobe changes and neurodegenerative disease trajectories.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, cognitive aging, early diagnosis, episodic memory, learning, temporal lobe

Introduction

Episodic memory consolidation—the process by which “temporary, labile memory is transformed into a more stable, long-lasting form”—involves a host of changes within the brain, ranging from the strengthening of connections between individual synapses to the reorganization of entire brain networks distributed across multiple neocortical regions (Squire, Genzel, Wixted, & Morris, 2015, p. 1). Although these neurobiological changes require days, weeks, or perhaps even years to unfold, standard neuropsychological tests of episodic memory typically assess recall after much briefer delay periods of 10 to 30 minutes (Lezak, Howieson, Bigler, & Tranel, 2012). Conventional memory tests are therefore subject to ceiling effects and may critically miss longer-term recall deficits that occur in typical aging and early stages of neurodegenerative disease (Loewenstein, Curiel, Duara, & Buschke, 2018). For example, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the leading cause of dementia among older adults, is hallmarked by degenerative changes in the medial temporal lobes (MTL)—a brain system that is integral for learning and retaining new information (Squire, Stark, & Clark, 2004). However, impairments on standard memory tests often do not become apparent until years or even decades after AD pathology begins to accrue, which greatly complicates early detection and intervention efforts (Jack et al., 2018).

A growing body of literature supports the utility of episodic memory paradigms with extended delay periods for assessing clinically meaningful deficits in recall performance that are not captured by traditional neuropsychological tests. For example, we previously demonstrated that recall of a story following a 1-week delay is significantly more sensitive to accelerated forgetting than standard (≤ 30 minute) delay periods in individuals with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI; Walsh et al., 2014). Other research groups have similarly demonstrated that individuals with subjective cognitive complaints (Manes, Serrano, Calcagno, Cardozo, & Hodges, 2008), pre-symptomatic autosomal dominant AD (Weston et al., 2018), and epilepsy (Butler et al., 2007) show poor performances on extended (1–6 week) delayed recall paradigms despite normal performance on memory tests with briefer delays. Neuroanatomically, we also found that worse 1-week delayed recall was cross-sectionally associated with smaller MTL volumes in clinically normal older adults, whereas standard delay periods (20–30 minutes) were not (Saloner et al., 2018).

The present study aimed to extend prior cross-sectional work by evaluating if memory recall following an extended delay predicts longitudinal changes in brain structure and cognition in older adults classified as clinically normal at baseline. We hypothesized that poorer recall following a 1-week delay period would be more sensitive to declines in MTL structure and function compared to recall ability following a traditional (30-minute) delay. To probe for neuroanatomical and cognitive specificity, we also evaluated the relationship between recall abilities and longitudinal changes in occipital lobe volumes (control region), total gray matter volumes, and performance on non-memory neuropsychological tests.

Method

The sample was comprised of community-dwelling older adults (52–92 years old) participating in the Hillblom Aging Network at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Memory and Aging Center. Recruitment for the Hillblom Aging Network began in 2000, primarily through flyers, community outreach events, snowball sampling, and newspaper advertisements in the Bay Area. All participants underwent comprehensive neurobehavioral examinations and were determined to be clinically normal at baseline per consensus conference with a board-certified neuropsychologist and neurologist, as published elsewhere (Lindbergh et al., 2019). Individuals with MCI or dementia at baseline, or any neurological disorder known to impact cognition (e.g., epilepsy, stroke), were excluded. The present analyses included 134 participants who completed the Story Recall Test (described below) at their baseline visit and underwent longitudinal neuroimaging during annual study visits, occurring approximately 15–18 months apart, over a timeframe of up to 7.15 years from baseline (mean number of study visits = 2.26; range = 2–4 visits). Larger subsets of the cohort underwent longitudinal cognitive testing, including 207 participants with processing speed data (mean = 2.49 visits; range = 2–6 visits; followed for up to 8.04 years from baseline) and 178 participants with episodic memory data (mean = 2.68 visits; range = 2–7 visits; followed for up to 8.04 years from baseline) and executive functioning data (mean = 2.76 visits; range = 2–7 visits; followed for up to 8.04 years from baseline). A more detailed breakdown of the number of observations at each timepoint for each outcome of interest is provided in Table 1. The study was conducted in compliance with the standards set forth by the UCSF Committee on Human Research and the Helsinki Declaration.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Subset with Processing Speed Composite (N = 207) | Subset with Memory Composite (N = 178) | Subset with Executive Composite (N = 178) | Subset with Brain Structural Volumes (N = 134) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 74.3 (6.8) | 75.5 (6.0) | 75.5 (6.0) | 75.1 (5.6) |

| Sex (% female) | 57% | 51% | 51% | 54% |

| Race (% White) | 92%a | 94%b | 94%b | 93%c |

| Education (years) | 17.5 (2.0) | 17.5 (2.1) | 17.5 (2.1) | 17.7 (2.0) |

| APOE (% ε4 carrier) | 22%d | 22% | 22% | 22% |

| SRT 30-Minute | 18.5 (1.4) | 18.4 (1.5) | 18.4 (1.5) | 18.6 (1.4) |

| SRT 1-Week | 12.8 (4.4) | 12.9 (4.4) | 12.9 (4.4) | 12.7 (4.4) |

| SRT Learning Trials | 5.1 (0.5) | 5.1 (0.5) | 5.1 (0.5) | 5.0 (0.2) |

| # participants with 2 visits | n = 207 | n = 178 | n = 178 | n = 134 |

| # participants with 3 visits | n = 89 | n = 77 | n = 85 | n = 32 |

| # participants with 4 visits | n = 10 | n = 29 | n = 35 | n = 2 |

| # participants with 5 visits | n = 3 | n = 11 | n = 13 | -- |

| # participants with 6 visits | n = 1 | n = 3 | n = 2 | -- |

| # participants with 7 visits | -- | n = 1 | n = 1 | -- |

Note. Descriptive statistics at baseline are presented as mean (standard deviation) or frequency (i.e., percentage or n) for subsets of the cohort with data available for each cognitive and brain structural outcome of interest. As shown, participants had varying numbers of study visits (2–7 visits) because the Hillblom Aging Network is an active longitudinal study with ongoing recruitment and enrollment efforts; accordingly, some participants were enrolled more recently than others and therefore had not accrued as many follow-up visits. APOE = apolipoprotein E (percentage of participants who were carriers of at least one copy of the ε4 allele). SRT = Story Recall Test. SRT 30-Minute and 1-Week = average number of story units recalled (out of 20) at the different delay periods. SRT Learning Trials = average number of learning trials required to reach the 90% mastery criterion.

N = 201;

N = 174;

N = 131;

N = 185.

Story Recall Test

The Story Recall Test (SRT), which Lezak (1995) refers to as “Fishermen,” is described in detail elsewhere (Butler et al., 2009; Saloner et al., 2018; Walsh et al., 2014). Briefly, the SRT involves reading aloud a 20-unit story to the examinee across a minimum of 5 learning trials. Additional learning trials are administered until the examinee reaches a 90% mastery criterion (18/20 units) to help control for initial learning levels. In our sample, the number of learning trials administered ranged from 5 to 9 (mean, median, and mode = 5). The SRT provides measures of delayed free recall at both 30 minutes and 1 week, with scores at each delay interval ranging from 0 (no story units recalled) to 20 (all story units recalled). The 1-week delayed recall assessment is conducted via telephone. The precise time of day is not held exactly constant between the 30-minute and 1-week delay intervals, though performance was always assessed during standard business hours for the present study (9:00 am to 5:00 pm). Examinees are not notified ahead of time about either the 30-minute or 1-week delayed recall to minimize rehearsal or other effortful memorization strategies. Frequency histograms of SRT performance at both delay intervals are provided in Supplemental Materials (Figures S1 and S2). In the largest subset of participants (N = 207), SRT 1-week recall was moderately correlated with SRT 30-minute recall (r = .238, p = .001) and demonstrated a negative, trend-level association with number of learning trials required to reach the 90% mastery criterion (r = −.119, p = .086). SRT 1-week recall was largely dissociable from the cognitive composite outcome measures (described below) in cross-sectional analyses at baseline, demonstrating only modest correlations with better performance on the episodic memory composite (r = .154, p = .04) and the processing speed composite (r = −.176, p = .011), and no significant relation with the executive functioning composite (r = −.033, p = .665).

Cognitive Outcomes

Cognitive outcomes included z-score composite measures of episodic memory (using delay periods of 10–20 minutes), executive functioning, and processing speed, all of which are described in prior publications (e.g., Lindbergh et al., 2019). Briefly, the episodic memory composite is comprised of the Benson Figure Recall and the California Verbal Learning Test, second edition (CVLT-II), including immediate free recall total correct (trials 1–5), long delay free recall total correct, and recognition discriminability (d’). The executive functioning composite consists of Stroop interference, digit span backward, phonemic fluency (number of D-words per minute), modified Trail Making Test, and design fluency (Condition 1, Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System). The processing speed composite includes six computerized visually-based reaction time tasks, as detailed by Kerchner et al. (2012), which are normalized relative to healthy young adults (lower scores = faster performance). Participants were administered two different versions of the CVLT-II (Standard Form and Alternate Form) on sequential study visits to help minimize practice effects, though alternate forms were unavailable for the other cognitive measures. Performance on the episodic memory (b = −.04, p = .004), executive functioning (b = −.02, p = .022), and processing speed (b = .10, p < .001) composites all showed statistically significant longitudinal declines over the course of the study, suggesting sensitivity to the aging process.

Brain Structural Outcomes

T1-weighted magnetization prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) MRI scans were acquired sagittally on either a 3.0 Tesla Siemens TIM Trio or 3.0 Tesla Siemens Prisma Fit scanner, which had nearly identical parameters (TR = 2300 ms, TI = 900 ms, flip angle = 9°, FOV = 240×256 mm with 1×1 mm in-plane resolution and 1 mm slice thickness), but slightly different echo times (Trio: 2.98 ms; Prisma: 2.9 ms). Image processing included magnetic field bias correction using the N3 algorithm, tissue segmentation using SPM12’s unified segmentation procedure, and warping of each participant’s gray matter segmentation to produce a study-specific template using DARTEL (Diffeomorphic Anatomical Registration using Exponentiated Lie algebra) (Ashburner, 2007). Nonlinear and rigid-body transformation was applied to normalize and modulate each participant’s native space gray matter segmentation to study-specific template space. Smoothing was achieved using a Gaussian kernel of 4-mm full width half maximum. Linear and nonlinear transformations between DARTEL’s space and ICBM space were performed for statistical purposes. Brain region volumes of interest were calculated by transforming a standard parcellation atlas into ICBM space and adding together all gray matter within each parcellated region (Desikan et al., 2006). The MTL volume was comprised of bilateral hippocampal, entorhinal, and parahippocampal cortices (Squire et al., 2004). Total gray matter volumes and occipital lobe volumes (lingual, pericalcarine, cuneus, and lateral occipital regions) were also calculated to evaluate for specificity of observed effects to MTL regions. Each brain volume of interest (MTL, occipital lobe, total gray matter) was thus represented by a single value—the sum of all parcellated gray matter within that volume in milliliters—in our statistical analyses (described below). The occipital lobe was selected a priori as a control region given its lack of involvement in verbal episodic memory performance. In addition, the occipital lobe has been used as a control region in prior (cross-sectional) investigations of the neuroanatomical correlates of SRT performance (e.g., Saloner et al., 2018); using it again in the present study facilitates consistency and comparability in the literature.

Statistical Analyses

Linear mixed-effects regression models were employed to test the relationship of baseline SRT performance to cognitive and brain structure trajectories over time. Mixed-effects modeling was chosen due to its ability to accommodate complex longitudinal datasets in which individual participants have varying numbers of study visits and data points. All models allowed for random intercepts and slopes, except for one model that failed to converge (SRT 1-week recall predicting processing speed), which used only random intercepts. SRT was modeled continuously as a fixed effect (total number of story units freely recalled at baseline, separately for the 30-minute and 1-week delay periods) and time was modeled continuously as years from baseline. The primary term of interest was therefore the interaction between SRT performance and time (SRT × time) on the outcome variables. Results are presented as unstandardized regression coefficients to directly reflect change in annualized decline (i.e., slope) of the outcome (brain volume in milliliters or cognition in z-scores) for each unit increase in baseline SRT performance. All models controlled for baseline age, sex, and education. Total intracranial volume was included as an additional covariate when predicting brain structural outcomes. A conventional α-level of p < .05, two-tailed, was used to define statistically significant effects. A sensitivity analysis revealed that all of our brain structural findings held upon also controlling for MRI scanner (Trio versus Prisma).

Results

As indicated in Table 1, SRT performance and demographic characteristics were very similar across the different subsets of participants with data available for each outcome of interest. Overall, the sample was highly educated (>17 years on average; range = 12–20) with a slight female majority. In the largest subset of participants (N = 207), educational attainment was positively associated with SRT 30-minute recall (r = .246, p < .001) but not 1-week recall (r = −.032, p = .642) at baseline. Males and females did not significantly differ on SRT performance at either delay period (ps > .05). Regarding the outcome measures, education was significantly associated with performance on the executive functioning composite (r = .307, p < .001) but not the processing speed composite, episodic memory composite, or MTL volumes (ps > .05). Females outperformed males on the episodic memory composite (t = −3.14, p = .002); there were no sex differences on the processing speed composite, executive functioning composite, or MTL volumes (ps > .05).

In the largest subset of participants (N = 207), there were no significant differences (ps all > .05) in age, sex, education, race, or SRT performance between participants who completed 2 study visits (54% female; mean education = 17.53 years), 3 study visits (61% female; mean education = 17.47 years), or ≥4 study visits (50% female; mean education = 17.60 years). Over the course of the study, 9 of 207 participants (4.35%) converted to MCI or dementia. These “converters” displayed worse SRT 1-week recall compared to non-converters at baseline (t = 2.33, p = .021) despite no significant differences in performance on the standard episodic memory composite (t = 0.86, p = .384). This raises the possibility that longer-term recall decrements may hold predictive utility for subsequent conversion to MCI or dementia, though conclusions are limited by small cell sizes. Among 185 participants in the sample with APOE genotyping available, SRT 1-week recall performance was similar (t = −0.15, p = .883) between carriers of the ε4 allele (N = 41) and non-carriers (N = 144).

SRT 1-Week Delay

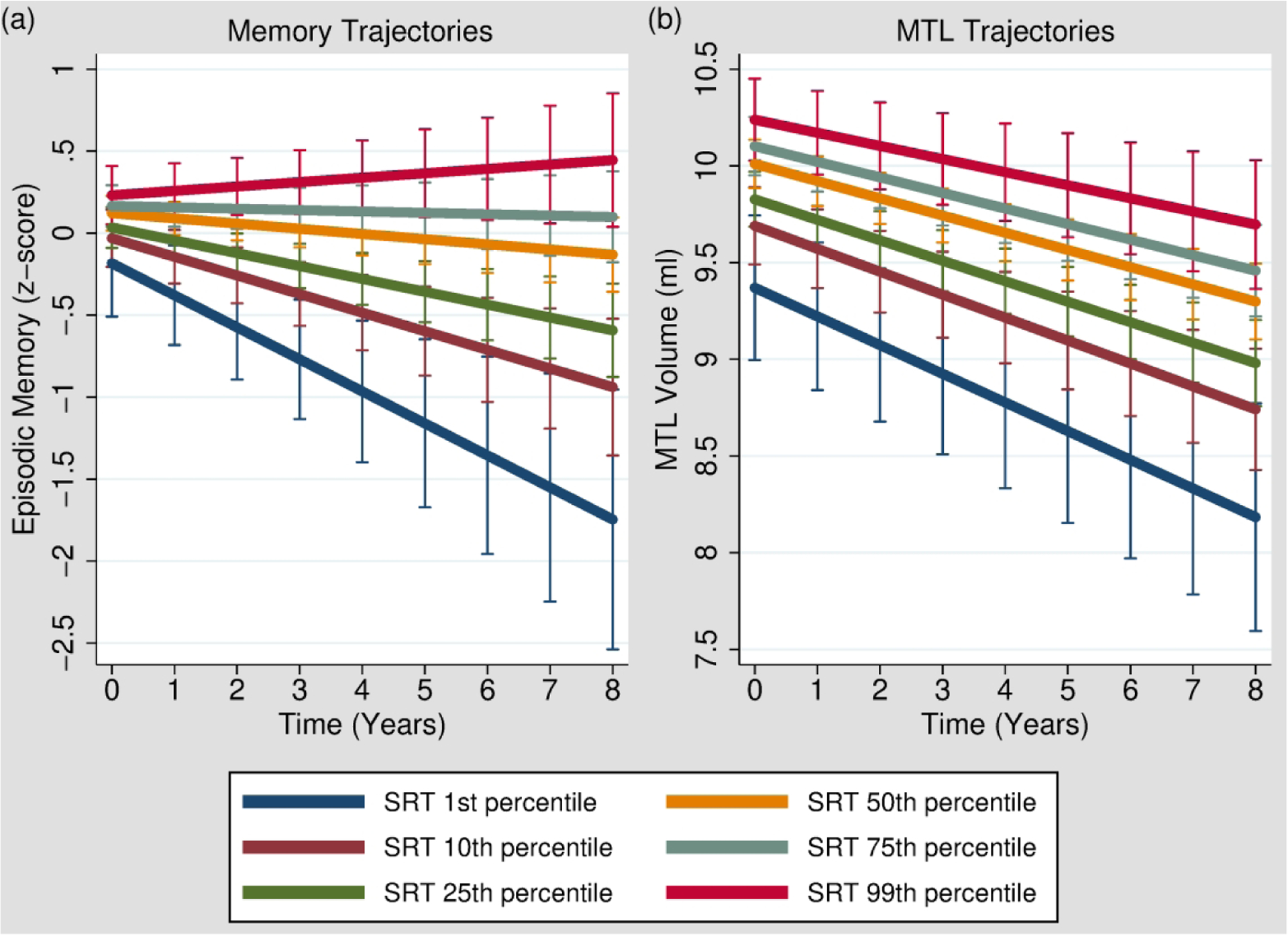

The main effects of SRT 1-week delayed recall on episodic memory (b = 0.02, p = .074), executive functioning (b = −0.01, p = .32), and processing speed (b = −0.04, p = .09) composite scores were not significant. Importantly, worse SRT 1-week delayed recall at baseline interacted with time (SRT 1-week × time) to predict significantly steeper rates of longitudinal decline in episodic memory (b = 0.01, p = .003; Figure 1a) and executive functioning (b = 0.006, p = .011) composites, but not processing speed (b = −0.006, p = .32).

Figure 1.

Worse 1-week delayed recall on the SRT (Story Recall Test) at baseline was associated with significantly steeper rates of longitudinal decline in episodic memory (California Verbal Learning Test and Benson Figure Recall composite score) and MTL (medial temporal lobe) volumes. To depict these interactions (SRT 1-week × time), episodic memory trajectories [Panel (a)] and MTL volume trajectories [Panel (b)] with 95% confidence intervals are plotted at various levels of 1-week recall performance in our sample, including the 1st percentile (SRT = 0/20 units recalled), 10th percentile (SRT = 7/20 units recalled), 25th percentile (SRT = 10/20 units recalled), 50th percentile (SRT = 14/20 units recalled), 75th percentile (SRT = 16/20 units recalled), and 99th percentile (SRT = 19/20 units recalled). It should be kept in mind, however, that SRT performance was treated as a continuous variable in our analyses; the delineation of the sample into representative percentiles is presented here solely to assist in visualizing the SRT 1-week × time interactions.

There was a significant main effect of worse SRT 1-week recall on smaller MTL volumes (b = 0.05, p = .001), consistent with previously published cross-sectional findings from this cohort (Saloner et al., 2018). In addition, worse SRT 1-week recall at baseline was associated with significantly steeper rates of longitudinal decline in MTL volumes (SRT 1-week × time: b = 0.004, p = .037; Figure 1b). To determine whether specific subregions of the MTL were driving this relationship, we decomposed MTL volumes into its subcomponents and observed a significant SRT 1-week × time interaction on bilateral entorhinal cortex (b = 0.002, p = .023), but not hippocampal (b = 0.002, p = .075) or parahippocampal (b = 0.001, p = .13) regions.

As expected, SRT 1-week recall did not significantly interact with time in predicting occipital lobe (b = −0.005, p = .58) or total gray matter volume (b = −0.03, p = .76) trajectories.

All primary analyses that were statistically significant were repeated with SRT 30-minute delayed recall in the models to determine whether the 1-week delay provided any predictive utility above and beyond a more typical delay period of 30 minutes. The overall pattern of results remained virtually unchanged. Specifically, worse SRT 1-week recall continued to predict significantly steeper rates of longitudinal decline (SRT 1-week × time) in episodic memory (b = 0.01, p = .002), executive functioning (b = 0.006, p = .01), and MTL volumes (b = 0.004, p = .036) with little to no attenuation of effect sizes. The main effect of SRT 1-week recall on MTL volumes was modestly attenuated, but remained statistically significant (b = 0.04, p = .003).

SRT 30-Minute Delay

There was a significant main effect of poorer SRT 30-minute delayed recall on worse performance on the episodic memory composite (b = 0.15, p < .001), but not on either executive functioning (b = 0.03, p = .35) or processing speed (b = 0.003, p = .96) performance. SRT 30-minute delayed recall at baseline did not significantly interact with time to predict longitudinal changes in the episodic memory (b = 0.02, p = .11) or processing speed (b = −0.02, p = .40) composites. However, worse baseline SRT 30-minute delayed recall was associated with longitudinal declines in executive functioning (SRT 30-minute × time: b = 0.01, p = .044). This effect remained statistically significant and of very similar magnitude with SRT 1-week recall in the model (b = 0.01, p = .045).

Neither the main effect of SRT 30-minute delayed recall on MTL volumes (b = 0.07, p = .14) nor the SRT 30-minute × time interaction on MTL volume trajectories (b = 0.01, p = .10) were statistically significant. SRT 30-minute recall did not significantly interact with time in predicting occipital lobe (b = −0.03, p = .26) or total gray matter volume (b = −0.13, p = .64) trajectories.

SRT Learning Trials

The number of learning trials required to meet the 90% mastery criterion on the SRT did not significantly predict (SRT learning × time) longitudinal trajectories in episodic memory composites (b = .015, p = .74), executive functioning composites (b = .0019, p = .95), processing speed composites (b = .019, p = .79), or MTL volumes (b = −0.011, p = .788).

Discussion

Our main finding was that memory recall following an extended (1 week) delay significantly predicted cognitive and brain volume trajectories among clinically normal older adults. Specifically, poorer 1-week delayed recall was associated with steeper rates of decline in episodic memory (as assessed by traditional neuropsychological tests), executive functioning, and MTL volumes. By contrast, recall following a standard (30-minute) delay did not significantly predict future changes in episodic memory or MTL volumes, though there was a relationship with executive functioning trajectories. Taken together, these findings extend prior cross-sectional work (Saloner et al., 2018; Walsh et al., 2014) and highlight the added longitudinal prognostic value of using memory paradigms with extended delays to capture longer-term recall abilities.

The observed association between 1-week delayed recall and MTL volume trajectories in clinically normal older adults suggests that assessing memory performance over longer timeframes may improve sensitivity to very early brain changes implicated in age-related neurodegenerative conditions such as AD. Indeed, post hoc analyses indicated that this relationship was driven by declines in entorhinal cortex volume, which is among the first MTL subcomponents to be affected by AD pathology (Braak, Alafuzoff, Arzberger, Kretzschmar, & Tredici, 2006). Although this suggests that longer-term recall decrements may be an early marker of AD-related changes, further work is needed to evaluate correlations with established AD biomarkers of β-amyloid and pathologic tau aggregation. Regardless, the lack of a significant association between 30-minute delayed recall and MTL volume trajectories, or longitudinal episodic memory performance, indicates that conventional delay periods may be less sensitive to early brain changes in aging adults without overt cognitive impairments.

As expected, neither 30-minute nor 1-week delayed recall was associated with longitudinal changes in processing speed, occipital lobe volumes, or total gray matter volumes, supporting the cognitive and neuroanatomical specificity of our findings. Unexpectedly, however, poorer performance following both the 30-minute and 1-week delay predicted longitudinal declines in executive functioning. Prior work has demonstrated that executive skills contribute to episodic memory performance by facilitating successful encoding (learning) and retrieval (Casaletto et al., 2017). Considering that the SRT memory paradigm controls for initial learning by requiring a 90% mastery criterion, the association we observed may relate to executive-mediated retrieval processes, possibly stemming from fronto-parietal network dysfunction (Angel et al., 2016). In turn, these retrieval inefficiencies may precede and subsequently develop into executive difficulties more broadly as captured by neuropsychological tests specifically designed to measure executive functioning. Future studies are needed to test this hypothesis more directly.

It should be acknowledged that SRT 30-minute recall performance was negatively skewed in our sample with many participants demonstrating “ceiling” effects (see Supplemental Figure S1), likely related to the high mastery criterion (≥90%) required on initial learning trials. The skewed distribution and associated lack of variability is likely at least in part responsible for the failure of the 30-minute delay to predict future MTL trajectories as robustly as the 1-week delay, which showed a relatively more normal distribution (see Supplemental Figure S2). That said, the clear differences in performance distributions between the 30-minute and 1-week delay intervals are in many ways consistent with our hypotheses: more challenging memory paradigms with extended delays appear to improve psychometric properties by increasing sensitivity to subtle decrements in recall performance that are not captured with traditional delay periods.

Future work will be necessary to shed light onto the precise cognitive and biological factors that explain why some older adults show decrements in recall after extended delay intervals. This may reflect deficits in longer-term consolidation or a host of other phenomena, such as subtle difficulties with encoding, post-consolidation storage disruptions (e.g., from retroactive interference), or retrieval failures. The numerous factors that can impact delayed recall performance were not experimentally manipulated in the SRT paradigm, which reflects a limitation of the present study and hinders conclusions about underlying processes.

Other study limitations include the possibility that environmental differences between the 30-minute delayed recall (in-person) and the 1-week delayed recall (telephone call) influenced our results, particularly considering the broader literature on state-dependent learning effects (Radulovic, Jovasevic, & Meyer, 2017). At the same time, the ability to follow-up remotely via telephone improves the practicality of assessing longer-term recall and may actually increase ecological validity given that day-to-day memory performance occurs across a range of environmental contexts. Future work would benefit from exploring variations in delay periods (e.g., weeks versus months), information content (e.g., verbal versus visual material), and other factors that may increase sensitivity to early decline and/or tap different underlying neuroanatomies. It also may be informative to evaluate whether longitudinal changes in SRT performance track with longitudinal changes in MTL structure and function; the present analysis was limited to whether SRT performance assessed at baseline predicts future trajectories. In addition, we generally did not use alternate forms for our cognitive outcomes (except for the CVLT-II) and the extent to which practice effects impacted observed trajectories is unclear, though it is somewhat reassuring that all of our cognitive composites showed significant age-associated declines over the course of the study.

The exact time of day that recall was assessed on the SRT was not held constant between the 30-minute delay and the 1-week delay, which warrants consideration in future studies. We also did not evaluate the extent to which participants employed effortful memorization strategies (e.g., rehearsal) during the delay intervals; individuals in early neurodegenerative disease stages may be less likely to use such strategies, which could have impacted our findings. Finally, replication in more diverse populations will be necessary, particularly considering that the present sample was predominately Caucasian and highly educated.

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge the present study is the first to evaluate whether memory paradigms with extended delay periods can predict longitudinal cognitive and brain structural outcomes in an aging population. It appears that decrements in longer-term recall performance, even among clinically normal older adults, may hold unique potential to improve early detection of unhealthy brain aging and neurodegenerative disease trajectories.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest: J.H.K. helped develop the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System and receives royalties from Pearson Education, Inc., for helping to develop the California Verbal Learning Test. No other study authors have any conflicts of interest or other disclosures to report.

Funding Sources: This work was supported by the Alzheimer’s Association (R.L.J., grant number AARF-16-443577); the Larry L. Hillblom Foundation (K.B.C., grant number 2017-A-004-FEL), (A.M.S., grant number 2018-A-025-FEL), (J.H.K., grant number 2018-A-006-NET); and the National Institutes of Health-National Institute on Aging (K.B.C., grant numbers K23AG058752, L30AG057123), (A.M.S., grant number K23AG061253), (J.H.K., grant numbers P50AG023501, R01AG032289, R01AG048234).

References

- Angel L, Bastin C, Genon S, Salmon E, Fay S, Balteau E, … Collette F (2016). Neural correlates of successful memory retrieval in aging: Do executive functioning and task difficulty matter? Brain Research, 1631, 53–71. 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J (2007). A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. NeuroImage, 38(1), 95–113. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2007.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, & Tredici K (2006). Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathologica, 112(4), 389–404. 10.1007/s00401-006-0127-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler CR, Bhaduri A, Acosta-Cabronero J, Nestor PJ, Kapur N, Graham KS, … Zeman AZ (2009). Transient epileptic amnesia: Regional brain atrophy and its relationship to memory deficits. Brain, 132(2), 357–368. 10.1093/brain/awn336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler CR, Graham KS, Hodges JR, Kapur N, Wardlaw JM, & Zeman AZJ (2007). The syndrome of transient epileptic amnesia. Annals of Neurology, 61(6), 587–598. 10.1002/ana.21111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casaletto KB, Marx G, Dutt S, Neuhaus J, Saloner R, Kritikos L, … Kramer JH (2017). Is “Learning” episodic memory? Distinct cognitive and neuroanatomic correlates of immediate recall during learning trials in neurologically normal aging and neurodegenerative cohorts. Neuropsychologia, 102, 19–28. 10.1016/J.NEUROPSYCHOLOGIA.2017.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, … Killiany RJ (2006). An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. NeuroImage, 31(3), 968–980. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2006.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, … Silverberg N (2018). NIA-AA research framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 14(4), 535–562. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerchner GA, Racine CA, Hale S, Wilheim R, Laluz V, Miller BL, & Kramer JH (2012). Cognitive processing speed in older adults: Relationship with white matter integrity. PLoS ONE, 7(11), e50425. 10.1371/journal.pone.0050425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak M (1995). Neuropsychological Assessment. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lezak M, Howieson D, Bigler E, & Tranel D (2012). Neuropsychological Assessment (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lindbergh CA, Casaletto KB, Staffaroni AM, Elahi F, Walters SM, You M, … Kramer JH (2019). Systemic tumor necrosis factor-alpha trajectories relate to brain health in typically aging older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 10.1093/gerona/glz209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Loewenstein DA, Curiel RE, Duara R, & Buschke H (2018). Novel cognitive paradigms for the detection of memory impairment in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Assessment, 25(3), 348–359. 10.1177/1073191117691608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manes F, Serrano C, Calcagno ML, Cardozo J, & Hodges J (2008). Accelerated forgetting in subjects with memory complaints: A new form of mild cognitive impairment? Journal of Neurology, 255(7), 1067–1070. 10.1007/s00415-008-0850-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulovic J, Jovasevic V, & Meyer MA (2017). Neurobiological mechanisms of state-dependent learning. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 45, 92–98. 10.1016/j.conb.2017.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloner R, Casaletto KB, Marx G, Dutt S, Vanden Bussche AB, You M, … Kramer JH (2018). Performance on a 1-week delayed recall task is associated with medial temporal lobe structures in neurologically normal older adults. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 32(3), 456–467. 10.1080/13854046.2017.1370134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Genzel L, Wixted JT, & Morris RG (2015). Memory consolidation. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 7(8), 1–21. 10.1101/cshperspect.a021766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Stark CEL, & Clark RE (2004). The medial temporal lobe. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 27(1), 279–306. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh CM, Wilkins S, Bettcher BM, Butler CR, Miller BL, & Kramer JH (2014). Memory consolidation in aging and MCI after 1 week. Neuropsychology, 28(2), 273–280. 10.1037/neu0000013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston PSJ, Nicholas JM, Henley SMD, Liang Y, Macpherson K, Donnachie E, … Fox NC (2018). Accelerated long-term forgetting in presymptomatic autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease: A cross-sectional study. The Lancet Neurology, 17(2), 123. 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30434-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.