Abstract

We investigated a Spanish and Catalan family in which multiple cancer types tracked across three generations, but for which no genetic etiology had been identified. Whole exome sequencing of germline DNA from multiple affected family members was performed to identify candidate variants to explain this occurrence of familial cancer. We discovered in all cancer-affected family members a single rare heterozygous germline variant (I654V, rs1801201) in ERBB2/HER2 that is located in a transmembrane glycine zipper motif critical for ERBB2-mediated signaling and in complete linkage disequilibrium (D’=1) with a common polymorphism (I655V, rs1136201) previously reported in some populations as associated with cancer risk. Because multiple cancer types occurred in this family, we tested both the I654V and the I655V variants for association with cancer across multiple tumor types in 6,371 cases of Northern European ancestry drawn from The Cancer Genome Atlas and 6,647 controls, and found that the rare variant (I654V) was significantly associated with an increased risk for cancer (OR=1.40, p=0.021, 95% CI=1.05–1.89). Functional assays performed in HEK 293T cells revealed that both the I655V single mutant (SM) and the I654V;I655V double mutant (DM) stabilized ERBB2 protein and activated ERBB2 signaling, with the DM activating ERBB2 significantly more than the SM alone. Thus, our results suggest a model whereby heritable genetic variation in the transmembrane domain activating ERBB2 signaling is associated with both sporadic and familial cancer risk, with increased ERBB2 stabilization and activation associated with increased cancer risk.

Keywords: ERBB2, Functional, Germline, Cancer Susceptibility

INTRODUCTION

Considerable data indicate that cancer is a highly heritable complex disease. Because the genetic architecture of familial disease is vastly simplified relative to that of sporadic disease, studying the genetics of complex diseases in families with multiple affected individuals is an attractive strategy to discover high penetrance susceptibility variants. The study of familial aggregations of cancer has led to the discovery of many genes that, when mutated, play a role in the etiology of different cancer types. In some cases, the inheritance of a high-penetrance susceptibility allele results in the occurrence of the same types of cancer amongst affected relatives, such as RB1 mutations and retinoblastoma(1). In others, it confers upon affected family members an increased risk for multiple cancer types, such as TP53 mutations and osteosarcoma, breast cancer, brain tumors, adrenocortical carcinoma, and others(2). Although many cancer syndromes have been identified, there remain many cancer-predisposed families that cannot yet be categorized. Studying such families enables the identification of potentially new cancer susceptibility genes and syndromes.

Importantly, except in very rare cases, genetics does not function in a vacuum. The expression of a trait or disease linked to even high penetrance variants can be significantly modified by other genetic factors, multiple non-genetic and environmental factors, and behaviors. As one example, the well-described CHEK2 c.1100delC variant is of moderate penetrance in the general population, but is of much higher penetrance in the context of a family history of cancer(3–5). Moreover, for multiple reasons including incomplete penetrance and sampling bias, even bona fide high-penetrance risk variants are sometimes identified in individuals unaffected by the associated disease(6,7). Therefore, multiple orthogonal genetic and functional studies are often required to assess fully the contribution of a candidate risk variant identified in a family. Here, we performed genetic and functional studies to characterize variation in ERBB2 identified in a single family with multiple cancer types tracking across three generations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects

The family investigated was ascertained at the Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona, Spain. All study subjects provided written informed consent that was approved by the Hospital Saint Joan de Déu institutional review board (IRB). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations and were approved by The University of Chicago IRB. To protect the anonymity of the study subjects, the family pedigree was altered in ways that did not affect the genetic analysis. Whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed on DNA samples from all consented family members; family members who were not analyzed did not provide DNA samples.

Exome capture and whole exome sequencing

Germline DNA for WES was obtained from whole blood. At least 1 μg of DNA was used for whole exome capture using the SureSelect Human All Exon V4 50 Mb kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). Paired-end (PE) Sequence reads were generated on an Illumina HiSeq2000 instrument (Illumina, San Diego, USA) at the University of Chicago Functional Genomics Facility.

Quality control, read alignment, and germline variant detection

The quality of raw sequencing reads was assessed by FastQC (v0.11.5) (http://wwwbioinformaticsbabrahamacuk/projects/fastqc). Reads were pre-processed to trim low-quality reads and remove adaptors, and mapped to human reference genome (hg19) using three aligners: BWA(8) (v0.7.9a), Bowtie2(9) (v2.2.1), and Novoalign (v3.02.05) (Novocraft, Malaysia). An average of 50±2 million (mean±S.E.M.) reads were uniquely mapped to reference genome for each sample. Read alignment was post-processed for duplicate removal using Picard tools, followed by indel (insertions/deletions) realignment and base quality score recalibration using GATK(10) (v1.6). Four callers were used for variant calling and genotyping: GATK UnifiedGenotyper(10) (v1.6); FreeBayes(11) (v0.9.13); Atlas2(12) (v1.4.3); and SAMtools(13) mpileup/bcftools (v0.1.19). Variant calls passing the internal quality filters of each caller were then filtered to remove potential false positives based upon: 1) variant quality score <50; 2) read coverage <5; 3) genotype quality score < 10; or 4) location within a single nucleotide variant (SNV) cluster in which >3 SNVs were called within a 10bp window. After combining results from the three aligners and four callers, variants called by at least two callers and found in the aligned sequence from at least two aligners were carried forward for annotation using ANNOVAR(14) (November, 2014 release). Global minor allele frequency (MAF) was derived from multiple public databases including The 1000 Genomes Project database (phase 1, release v3, 20101123); the Exome Variant Server, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (version ESP6500-V2-SSA137, Seattle, WA (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) [06/2012 accessed]); and the Exome Aggregation Consortium Project (ExAC65000, v0.3). Population-specific MAF were derived from the non-cancer dataset of The Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD)(15) (v2.1.1) (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/variant). Each variant was annotated for pathogenicity using seven prediction programs (SIFT; Polyphen-2; MutationTaster; MutationAssessor; FATHMM; LRT; and Radial SVM). We also calculated an ensemble deleteriousness score using Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD)(16). Variants were also assessed for multispecies conservation using GERP++ and PhyloP100Way scores.

Prioritization of candidate rare germline variants associated with cancer

To identify rare germline candidate causative variants, we required that variants passing our QC pipeline: 1) have a population MAF<0.01 in The 1000 Genomes Project, ESP Project and ExAC Project; 2) be either a non-synonymous, stop-gain, or stop-loss single nucleotide variant (SNV); a splice site modifier; or an insertion or deletion; and 3) be deleterious as predicted by at least one of the seven pathogenicity prediction programs. Variants were curated by the study team and prioritized based upon existing literature if they were in genes previously reported to be associated with heritable cancer and if so, whether they were in functional domains containing other heritable cancer-predisposing variants(17).

Confirmation of ERBB2 variants using Sanger sequencing

The primer sequences for ERBB2 exon17 were 5’-TTTATTGTGGAGGCAGCGGG-3’ (forward) and 5’-CAGTCTCCGCATCGTGTACT-3’ (reverse), with an expected amplicon of 305 base pairs. All PCR reactions were carried out using Phusion High Fidelity Taq (Thermo Scientific) with 50ng of genomic DNA and an annealing temperature of 60°C. PCR products were gel-extracted and sequenced to validate the mutations identified by WES. The sequencing results were compared with the ERBB2 reference sequence (RefSeq Gene accession ID NG_007503.1) to validate the presence of rs1801201 (I654V) and rs1136201 (I655V) in both the germline and the tumor samples.

Sporadic cancer case-control association studies

To investigate the association with cancer of rs1801201 (I654V) and rs1136201 (I655V), we utilized WES data on 8,321 cases from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (https://www.cancer.gov/tcga) representing 24 tumor types, and 7,388 controls from the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap). The studies included are listed in Supplementary Table 1. For germline WES variant calling, we performed a joint analysis of all case and controls using GVCF-based best practices for the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) as implemented in a custom pipeline at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai(18). We then performed sample and variant QC as previously described(19). We controlled for population stratification by principal components analysis (PCA) as previously described(20). In brief, we first removed rare variants (<0.05 MAF) found in the 1000 Genomes Project(21) and Ashkenazi Genome Consortium (https://ashkenazigenome.org) reference datasets. Then, using EIGENSTRAT 5.0.1, we performed linkage disequilibrium pruning, and finally, we focused on the largest cluster within the PCA plot by PCA gating. After QC and controlling for population structure, we analyzed 6,371 cases and 6,647 controls of Northern European ancestry.

DNA plasmids

A pcDNA3.1-ERBB2-WT plasmid was purchased from Addgene (ID16257, Watertown, MA, USA), and the cDNA of ERBB2 encoded on the plasmid was used as a template for site-directed mutagenesis. GENEART Site-Directed Mutagenesis System (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to mutate A1963G to generate the ERBB2 I655V mutant, and A1960G/A1963G to generate the I654V;I655V double-mutant. The PCR products were digested with DpnI (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and transformed into TOP10 chemically competent cells (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). The I655V mutant, I654V;I655V mutant and wild-type ERBB2 plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing. A plasmid with cDNA encoding MCHERRY in place of ERBB2 was used as a confirmation for transfection efficiency and a control plasmid in all the transfection experiments.

Cell culture and transfections

The HEK 293T cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. All cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100U/ml penicillin and 100μg/ml streptomycin. Transfections were carried out with Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) at 80% confluency. HEK 293T cells used for phospho-AKT expression analysis were transfected under serum-reduced conditions (0.1% FBS). Cells used for ERBB2 stability and phospho-p38 expression analysis were transfected under normal conditions (10% FBS).

For ERBB2 stability studies, cycloheximide (CHX; 100μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA)) was added 24 hours after transfection of the different ERBB2 constructs. Cells were then harvested for immunoblot analysis at various time points following the addition of CHX.

For ERBB2 pathway activation studies, cells were harvested for immunoblot analysis 24 hours after transfection of the different ERBB2 constructs.

Immunoblotting assays

For all experiments, cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer and sonicated. Protein concentrations were determined by Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). 10μg of total protein was resolved by SDS/PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membranes and blocked in 5% BSA for 1 hour at 4°C. All primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C, and secondary antibodies was incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. Chemiluminescence signals were revealed by Clarity Western ECL Blotting Substrate (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and detected by ChemiDoc system (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Pixel intensities were measured using ImageLab software version 5.2.1 by Bio-Rad. For the ERBB2 stability experiments, blots were probed with ERBB2, and RAN as a loading control. Five independent experiments were performed. Relative abundance of different ERBB2 isoforms was calculated as the percentage of ERBB2 present at 0hours. To measure the half-life of different ERBB2 isoforms, the protein degradation time course determined from each experiment was plotted individually for linear regression analyses. For ERBB2 pathway activation studies, blots were first probed for phospho-p38 or phospho-AKT, as well as RAN, as loading control. Then, membranes were stripped with Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s directions, and probed for total AKT or p38, as well as ERBB2. For each ERBB2 construct tested, we first calculated the ratio of activated phospho-AKT or phospho-p38 to total AKT or p38, and then controlled for loading by normalizing to RAN, and controlled for transfection efficiency by normalizing to ERBB2. Five biological replicates were performed for each experiment.

Immunoblotting reagents and antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal anti-RAN (1:1000), rabbit polyclonal anti-AKT (1:3000), rabbit polyclonal anti-p38 (1:3000), rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-p38 (Thr180/182) (1:2000), rabbit monoclonal anti-phospo-AKT (Ser473) (1:4000), and anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary (1:2000) antibodies were all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). RIPA lysis buffer and rabbit anti-Neu2 antibody (1:10,000) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA).

Tumor ERBB2 copy number analysis

To determine whether the WT- or the rs1801201/rs1136201-containing chromosomal strand was amplified somatically in the neuroblastoma tumor that was available for analysis, we performed copy number variation (CNV) analysis using the high-density genome-wide CytoScan® HD platform (Affymetrix, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). DNA was extracted from fresh frozen tumour biopsies with more than 70% viable tumour cell content using standard procedures. Analysis of the CytoScan® HD Array data was performed using the Chromosome Analysis Suite (ChAS) software (Affymetrix, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). We constructed phased haplotypes comprised of heterozygous variants located within 1 million base pairs of rs1801201/rs1136201 that were both directly genotyped on the CytoScan® HD Array and covered by WES target regions, thereby enabling us to distinguish the WT-containing strand from the rs1801201/rs1136201-containing strand. We then directly compared A/B allele fractions for each informative variant to identify the amplified chromosomal segment.

Statistical analysis

For ERBB2 stability studies, we used a two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. To assess ERBB2 isoform half-life differences, a one-way ANOVA was used followed by Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. For ERBB2 pathway activation studies, significance was assessed using an unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test. For association testing in the TCGA data set, a two-sided Fisher’s exact test was used. All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) and R 3.2.1.

RESULTS

Familial WES analysis

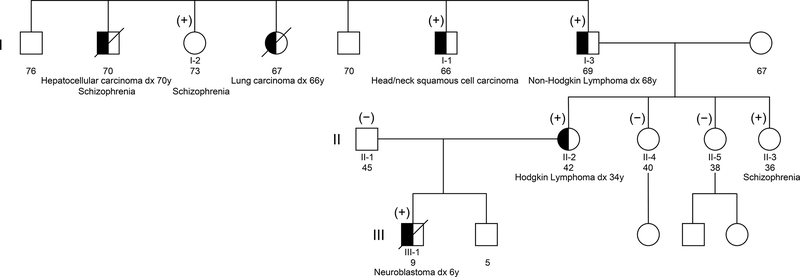

We performed WES on germline DNA from seven members spanning three generations of a single family of Spanish and Catalan ancestry in which there were multiple individuals diagnosed with cancer, confirmed by pathology review (Figure 1). Individuals I-1, I-2, and I-3 are full siblings; Individuals II-2, II-3, II-4, and II-5 are daughters of Individual I-3; individual II-1 is the unrelated spouse of individual II-2; and Individual III-1 is the son of Individuals II-1 and II-2. Individual I-1 was diagnosed with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma at age 20; Individual I-3 was diagnosed with Non-Hodgkin lymphoma at age 68; Individual II-2 was diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma at age 34; and Individual III-1 was diagnosed with high-risk neuroblastoma at age 6. Of note, a sister of Individuals I-1, I-2, and I-3 was diagnosed with lung cancer (age 66), and a brother was diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma (age 70), but no DNA was available for sequencing from either individual.

Figure 1. Cancer family pedigree.

Shown is a three-generation pedigree of the family. Germline DNA of individuals I-1, I-2, I-3, II-1, II-2, II-3, II-4, II-5, and III-1 were analyzed by WES. Cancer-affected individuals are denoted by blackened circles or squares. (+) indicates individuals heterozygous for the rare ERBB2 I654V variant; (−) indicates individuals homozygous for the reference allele.

For each sample, on average, over 98% of the captured exome was covered at 5x and at least 85% was covered at 20x, with an average coverage depth of 60x or greater (Supplementary Table 2). Variants of low quality score, read depth <5, or not called by at least two variant callers within the aligned sequence generated by at least two aligners were removed. After filtering out synonymous variants, 10,971±124 (mean±SD) variants/individual were identified (Supplementary Table 3).

Identification of candidate familial germline cancer-predisposing variation

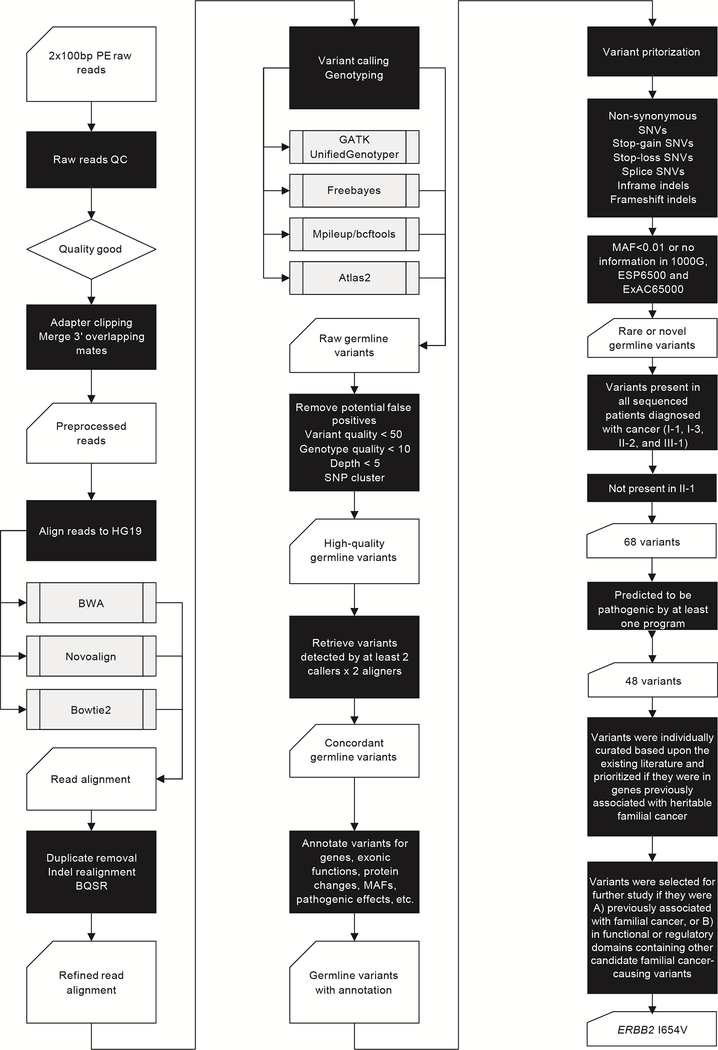

To identify candidate familial cancer-predisposing mutations, we hypothesized that the cancer-affected siblings, individuals I-1 and I-3, shared one or a small number of rare variants that were inherited by the cancer-affected Individuals II-2 and III-1. Because of incomplete penetrance, the small size of this family, and the difficulty inherent in interpreting the consequence of a putative risk variant observed in a cancer-unaffected family member (e.g., whether the individual is truly unaffected or is only unaffected by the time of last follow up), we considered cancer-unaffected family members to be uninformative and did not include them in our analysis. Our variant prioritization pipeline is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. WES and variant prioritization workflow.

Because individual II-1, the father of individual III-1, is genetically unrelated to the family and did not have either a personal or family history of cancer, we removed variants that were shared with him. Each affected individual carried an average of 1,217 rare (minor allele frequency (MAF) <0.01) or novel variants. After excluding those found in individual II-1, 68 variants were shared among the cancer-affected individuals (Supplementary Table 4). Variants were categorized as: non-frameshift indels (n=2), frameshift indels (n=1), nonsynonymous SNVs (n=60), splice SNVs (n=3), and stop-gain SNVs (n=2). Among these, 48 variants in 48 genes were predicted to be deleterious (Supplementary Table 5).

To prioritize among these 48 candidate variants, we first assessed whether any were in genes previously implicated in known familial cancer susceptibility syndromes(17) (Supplementary Table 6), but found none. Then, based on manual curation of the literature, we investigated the association between the genes and cancer susceptibility. We identified two heterozygous variants in two genes linked to familial cancer, one in AHCY, rs41301825 (MAF= 0.0063, European (non-Finnish)) (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/variant/20-32880242-C-T?dataset=gnomad_r2_1_non_cancer), resulting in a glutamine to arginine change at amino acid 123 (Q123R), and the other in ERBB2, rs1801201 (MAF= 0.0080, European (non-Finnish)), resulting in an isoleucine to valine substitution at amino acid 654 (I654V).

AHCY encodes SAH hydrolase (SAHH), a major regulator of methionine metabolism. SAHH deficiency is extremely rare, inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, and linked to severe liver disease, myotonia, cognitive impairment, and early death (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man®) (OMIM®) entry 180960, Phenotype #613752, https://www.omim.org/entry/180960 )(22). In one family, two affected individuals died of early onset hepatocellular carcinoma at ages 17 and 32. Heterozygotes have not been reported to have any phenotype or an increased risk for cancer(23). ERBB2 (also known as HER2/neu), is a gene commonly mutated somatically in breast cancer and other cancers. The heterozygous I654V variant, located within a transmembrane domain critical for ERBB2-mediated signaling has been associated with both sporadic and familial breast cancer(24,25). Additionally, the ERBB2 G660D variant, located in the same transmembrane domain, was implicated in familial lung cancer and was demonstrated to significantly alter ERBB2 function(26).

Taken together, these observations suggest that the ERBB2 I654V variant is the most likely candidate to explain the occurrence of multiple cancers in the family we studied, and so, it was selected for further investigation.

Sporadic cancer risk and ERBB2 I654V and I655V

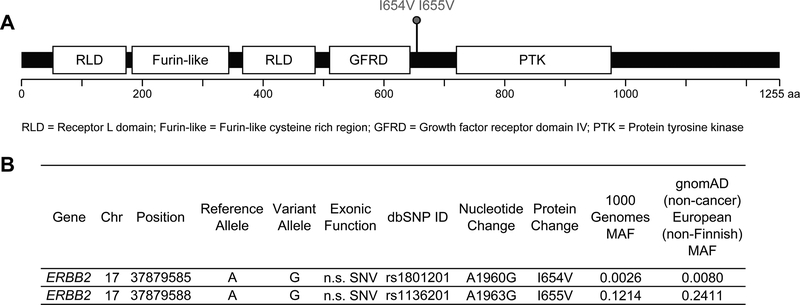

The allele frequency of I654V varies from 0.0080 in European (non-Finnish) to 0.0023 in Africans to 0.00 in East Asians in the gnomAD v2.1.1 non-cancer cohort. It is in complete linkage disequilibrium (LD) (D’=1) with a common polymorphism (rs1136201) causing an isoleucine to valine change at position 655 (I655V) (Figure 3). The correlation between the two variants, however, is very low (r2=0.023), because I655V is much more common than I654V (MAF=0.2411 in European (non-Finnish); 0.0411 in African; and 0.1202 in East Asian). Consequently, while all individuals with I654V carry the I655V variant, most individuals with I655V do not carry the I654V variant. As expected, all individuals in the family with I654V also have I655V, confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Although results remain controversial, I655V has been studied extensively in breast cancer and may be associated with increased risk in African and Asian ancestry populations, but not European or other populations, suggesting its effect may be modified by ancestry and genetic background(27–31).

Figure 3. Familial ERBB2 variants.

(A) Diagram of the ERBB2 protein showing functional domains. Red lollipops indicate germline variants carried by the affected individuals in the family. Common variants present in all individuals are not shown. (B) Genomic annotation for the two experimentally confirmed deleterious ERBB2 germline variants. Chr = Chromosome; SNV = single nucleotide variant; n.s. = nonsynonymous; MAF = minor allele frequency.

Because no family members developed the same cancer type and variation in the transmembrane domain, including I654V, has been reported in both familial breast and lung cancer, we hypothesized that I654V and/or I655V might be associated with risk for cancer across multiple cancer types. To test this, we investigated the association between each variant and cancer in a jointly called sample set from TCGA and dbGaP (see Supplementary Table 1 for datasets included). After accounting for population stratification and performing QC analysis, there remained 6,371 cases across 24 tumor types and 6,647 controls of Northern European ancestry. We found that the rare I654V variant was significantly associated with a pan-cancer risk (OR=1.40, p=0.021, 95% CI=1.05–1.89), but, as expected in this European sample set, the common I655V variant was not (OR=0.95, p=0.13, 95% CI:0.88–1.02). The Odds Ratio of the association between I654V and individual cancer types was >1.0 for 18/24 cancers in the data set and was most significant for cervical squamous cell carcinoma/endocervical adenocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma (Supplementary Table 7).

To explore further the association between ERBB2 and pan-cancer risk, we employed our pipeline to identify 67 rare deleterious ERBB2 variants that we jointly tested for association using penalized logistic regression. Whereas the overall enrichment of variants in cases neared significance (OR=1.17, p=0.071, 95% CI:0.98–1.40), when the I654V variant was removed from the analysis, the OR=1.06 (p=0.62, 95% CI:0.85–1.32), suggesting that no variant other than i654V was associated.

We also investigated AHCY rs41301825, and found no association (OR=1.29, p=0.17, 95% CI:0.90–1.84).

Functional studies of ERBB2 I654V and I655V

The rare ERBB2 variant causing a G660D amino acid substitution identified in a Japanese family with multi-generational lung adenocarcinoma is located within the same transmembrane Thr652-X3-Ser656-X3-Gly660 glycine zipper motif as I654V and I655V(26). It is functional, stabilizing and activating ERBB2, resulting in potentiated downstream AKT and p38 signaling, which thereby suggests a mechanism by which it may be associated with increased cancer risk(32–35).

We hypothesized that I654V and I655V would similarly stabilize ERBB2 dimerization and activate downstream signaling(26,36,37). Because the I654V allele is only found in the presence of the I655V allele but the I655V allele is often found in the absence of the I654V allele, we tested this by comparing wild-type ERBB2 (WT) activity to that of the I655V single-mutant (SM) and the I654V;I655V double-mutant (DM). Because the association between I655V and cancer is uncertain, whereas I654V is associated with both sporadic and high-penetrance familial disease(24,25), we further hypothesized that the DM would potentiate and activate ERBB2 signaling to a greater extent than the SM. To ensure that our results reflected the influence of the SM and DM on ERBB2 signaling, we performed these studies in HEK 293T cells, which lack both endogenous ERBB2 and other EGFR-related family members(38–40).

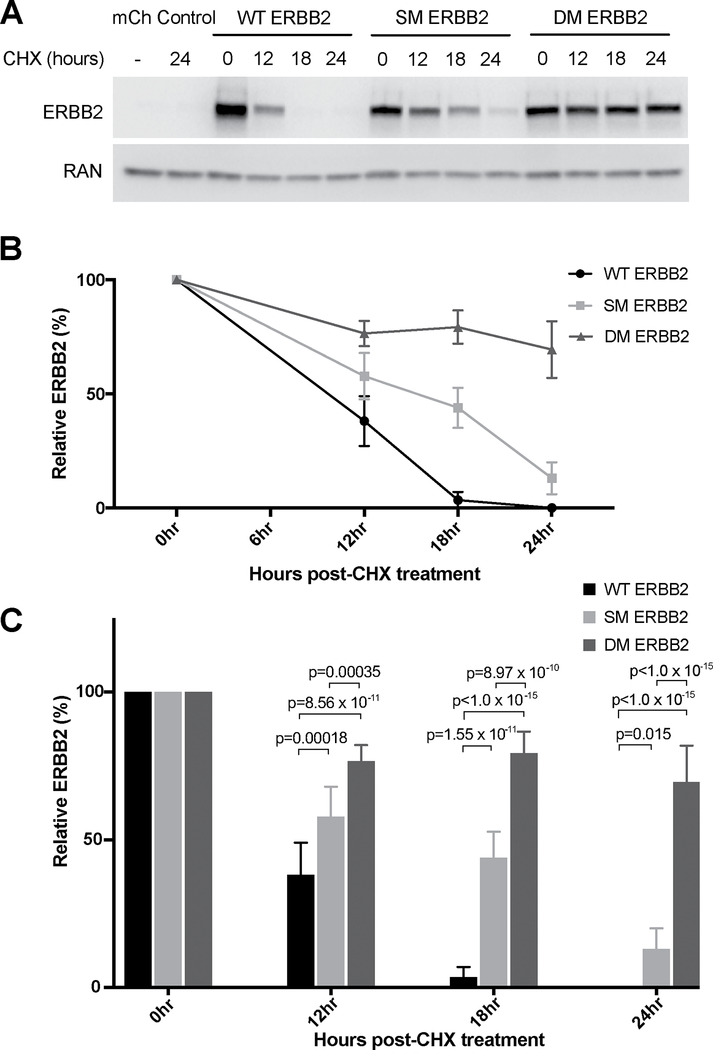

First, we investigated ERBB2 stability using either un-transfected controls, or following transient transfection with: MCHERRY-containing empty vector control; WT ERBB2; I655V SM ERBB2; or I654V;I655V DM ERBB2. 24 hours after transfection, protein synthesis was blocked with CHX and ERBB2 stability was determined by western blot at various time points following the addition of CHX. We found that whereas WT ERBB2 was degraded 12–18 hours after CHX administration, SM ERBB2 degradation occurred 18–24 hours after administration, and DM ERBB2 degradation was even slower, with significantly more DM ERBB2 remaining even 24 hours after CHX treatment (p<1.0×10−15 relative to both WT and SM) (Figure 4). Half-life estimates for WT, SM and DM ERBB2 were 10 hours, 15 hours, and more than 24 hours, respectively (Supplementary Figures 1A and 1B).

Figure 4. DM ERBB2 is more stable than either WT ERBB2 or SM ERBB2.

HEK 293T cells were either left un-transfected, or transfected with: empty-vector control; WT ERBB2; I655V SM ERBB2; or I654V;I655V DM ERBB2. They were then treated with CHX (100μg/ml) to terminate translation. Cell lysates were collected 0, 12, 18 and 24 hours after CHX treatment and ERBB2 stability over time was measured by western blot. Five biological replicates were performed. (A) A representative western blot of results demonstrating that both the SM ERBB2 and DM ERBB2 isoforms are more stable than WT ERBB2, and that the DM ERBB2 isoform is more stable than the SM ERBB2. (B) Quantification of ERBB2 protein levels after normalization to RAN from five independent experiments. The remaining amount of ERBB2 after CHX treatment for 12, 18 and 24hours was calculated as the percentage of ERBB2 present at 0 hour. Half-life determined from linear regression analyses for WT, SM and DM ERBB2 was 9.59 hours, 14.58 hours and 46.50 hours (with SD of 0.29, 1.49 and 23.37 respectively; n=5). (C) Statistical analyses of ERBB2 12, 18 and 24hours post-CHX treatment. Significance was assessed using two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Error bars represents mean±SD.

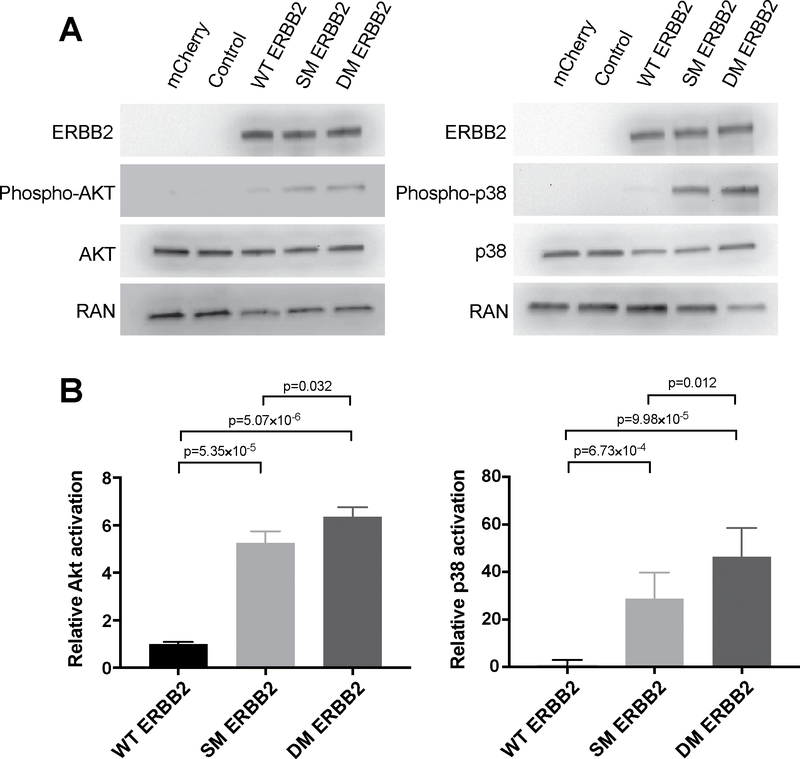

To assess the downstream consequences of enhanced ERBB2 stabilization, we investigated the activation of AKT and p38 signaling by measuring the ratios of phospho-AKT/AKT and phospho-p38/p38 proteins 24 hrs following transfection with either empty vector control; WT; SM; or DM ERBB2. We found that not only were both p38 and AKT signaling were significantly increased relative to WT following transfection with either the SM or DM, but that p38 and AKT signaling were also significantly enhanced by the DM relative to the SM (p=0.012 and p=0.032, respectively) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. DM ERBB2 activates ERBB2 signaling to a greater extent than either WT ERBB2 or SM ERBB2.

HEK 293T cells were either left un-transfected, or transfected with: empty-vector control; WT ERBB2; I655V SM ERBB2; or I654V;I655V DM ERBB2. Cell lysates were harvested 48 hours post-transfection and ERBB2 pathway activation was assessed by measuring the phosphorylation of AKT and p38. Five biological replicates were performed. (A) Representative western blots of AKT and p38 phosphorylation, respectively, demonstrating that both the SM ERBB2 and DM ERBB2 isoforms activate ERBB2 downstream signaling to a greater extent than WT ERBB2, and that the DM ERBB2 does so to a greater extent than the SM ERBB2. (B) Bar graphs quantifying results from five independent experiments for AKT and p38, respectively. Significance was assessed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. Error bars represent Mean±SD.

Taken together, these results indicate that both the SM and DM stabilize ERBB2 and activate downstream ERBB2 signaling relative to WT. The DM, however, containing both the rare I654V mutation and the common I655V variant, potentiated ERBB2 signaling to a significantly greater extent than the SM. Thus, the likely consequence of the variants is to aberrantly and cooperatively activate ERBB2-mediated oncogenic signaling.

Somatic amplification of ERBB2 in tumor DNA

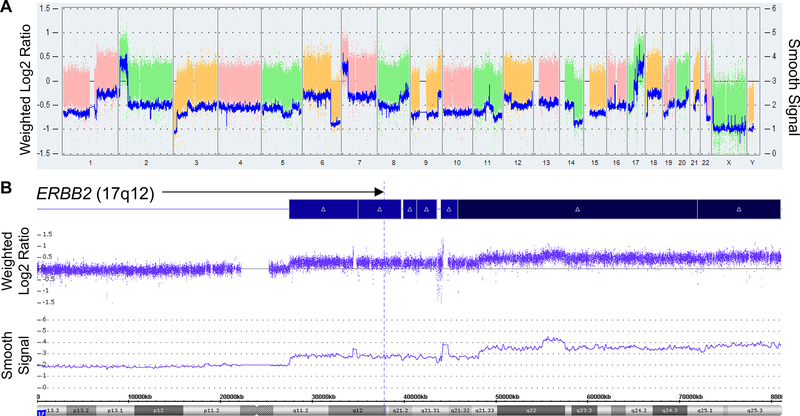

Somatic ERBB2 amplification is common in cancer and is mutually exclusive with somatic activating ERBB2 mutations(41–43). Because the I654V-containing allele is already activated, if our functional hypothesis is correct, then we would predict that in individuals carrying the I654V variant, there would be selective pressure for somatic alteration in a tumor of the remaining wild-type (WT) ERBB2 allele. To test this, we investigated the one familial tumor available for study, a neuroblastoma from Individual III-1. Sanger sequencing of ERBB2 confirmed that the DM remained heterozygous in the tumor. We assessed copy number in the tumor, and identified a somatic single-copy gain at chromosome 17q11.2-qter in a region encompassing ERBB2 (17q12), a well-described recurrent segmental chromosome aberration found in neuroblastoma and other cancers(44,45) (Figure 6). By comparing haplotypes containing either the wild-type or the DM alleles, we found that WT ERBB2 was amplified in the tumor.

Figure 6. Somatic chromosomal alterations in the primary neuroblastoma tumor from patient III-1.

(A) Genomic profile of copy number aberrations including gain of chromosome 1q, 2p and 17q, and loss of chromosome 1p, 11q and 14q. The log2 copy number is shown as colored blocks, with the corresponding y-axis labeled on the left side of the panel. The smoothed signal is shown as blue lines, with the corresponding y-axis labeled on the right side of the panel. (B) Zoom in view of chromosome 17, demonstrating a segmental gain of one copy at 17q11.2-q21.33 and two copies at 17q21.33-qter. The ERBB2 locus (17q12) is marked by a blue dashed line. The log2 copy number track and the smooth signal indicate the segmental copy number alterations observed in the sample.

DISCUSSION

We investigated by WES a family in which multiple individuals spanning multiple generations were diagnosed with cancer. While our study design was agnostic in that it only required candidate variants to be shared by cancer-affected family members, we prioritized variants for follow up based upon prior evidence of an association with heritable cancer. We identified 48 rare deleterious candidate causal variants shared amongst those with cancer, none of which segregated completely between cancer-affected and cancer-unaffected individuals. Moreover, although all cancer-affected members sequenced carried I654V, two unaffected family members did as well (I-2, II-3). There are many possible reasons that variant-carrying individuals may be cancer-unaffected, including incomplete penetrance, insufficient follow up time for cancer development, and the presence of risk-mitigating protective genetic or other factors; therefore, we did not include these individuals in our analysis. If Individual I-2 at age 73 is considered a “true negative,” then 26 candidate variants remain, including the AHCY variant, although it has no known phenotype or association with cancer susceptibility in the heterozygous carrier state. Based upon the confluence of evidence from the literature, the precedent of the G660D variant located in the same transmembrane domain, and our own orthogonal genetic and functional studies, we propose that the ERBB2 I654V (rs1801201) is the best candidate to explain the occurrence of cancer in this family.

ERBB2/HER2/neu is a member of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) family of receptor tyrosine kinases. When bound by ligand, EGFR family members form homodimers and heterodimers. Dimerization is required to activate tyrosine kinase signaling, which then regulates numerous processes including cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation; different ligand/dimer combinations activate different downstream signaling events(46),(47). Both I654V and I655V are located in a glycine zipper transmembrane domain critical for ERBB2 stabilization. In rats, mutations here induce constitutive dimerization and activation of oncogenic ERBB2 signaling(48). Additionally, in a murine breast cancer model, a small peptide directed against this domain reduced ERBB2 phosphorylation and AKT signaling, and inhibited tumor cell proliferation(49). Moreover, targeted anti-EGFR therapy in a lung cancer patient with the germline G660D variant elicited an anti-tumor response, indicating that this variant is clinically relevant and suggesting that the same may be true for I654V(50).

Because rs1801201 is in complete LD with rs1136201but is much rarer than rs1136201, I655V is commonly observed in the absence of I654V, but I654V is never observed in the absence of I655V. We found that the I655V SM significantly stabilizes and activates ERBB2 signaling as compared to WT, and that the I654V;I655V DM significantly stabilizes and activates ERBB2 signaling as compared to the SM. We hypothesize that by itself, I655V-mediated ERBB2 activation is insufficient to influence cancer risk, but that in some genetic backgrounds, ERBB2 activity is modified and further increased, thereby explaining the variable and ancestry-dependent association observed between I655V and cancer (e.g., in Asian and African ancestry individuals but not in European ancestry individuals). In contrast, because the DM activates ERBB2 significantly as compared to the SM alone, the association between I654V and cancer is more robust, and, at a population level, not dependent upon ancestry-specific modifiers, thereby explaining our observation in TCGA that I654V but not I655V is associated with pan-cancer risk in Europeans. As well as ancestry-specific genetic background, family-specific genetic background is also a well-described modifier of risk, likely due to the shared inheritance of other common and rare genetic factors among family members. In cancer, perhaps the best studied example of this is the CHEK2 c.1100delC variant. As with I654V(25), the effect size of the CHEK2 variant is greater in studies of cases with a positive family history as compared to those of cases unselected for family history((3,4) and many others). In one study of 26,000 unselected cases and 27,000 controls the CHEK2 c.1100delC variant had OR=2.7 (95% CI: 2.1–3.4), whereas among familial breast cancer the OR was increased to 4.8 (95% CI: 3.3–7.2), corresponding to a lifetime risk comparable to that of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants(5). Interestingly and perhaps unsurprisingly, the modifying effect of these other genetic factors is greater for lower penetrance risk variants than for high penetrance variants such as deleterious BRCA1/2 mutations(51,52). Taken together, these observations and our genetic and functional results suggest a model whereby increasing ERBB2 signaling is associated with increasing cancer risk, modified by ancestry, family history, and possibly other factors.

Somatic ERBB2 amplification leading to constitutive ERBB2-mediated signaling has been observed in up to 30% of breast cancers and other cancers as well(53–56). With regard to high-risk neuroblastoma, EGFR signaling is important for cell growth and proliferation, and copy number gains spanning ERBB2 are common(57,58). In the neuroblastoma sample analyzed, we observed somatic amplification of the WT isoleucine-containing allele. Little is known, however, about the influence of germline variation on somatic ERBB2 mutation acquisition. In two small studies of HER2-positive European breast cancer patients heterozygous for the I655V variant, there was a modest preference for somatic amplification of the valine-containing allele in tumors(59,60). In contrast, another study in ovarian cancer suggested that there was selective pressure for amplification of the isoleucine-containing allele(61). Further investigation is needed to understand the interplay between germline activating variation in ERBB2 and somatic amplifications in the development of different cancer types.

Interestingly, both I654V-carrying cancer-unaffected individuals (I-2, II-3) developed schizophrenia. Cancer may occur less frequently in individuals with schizophrenia than in the general population, although this observation remains controversial(62,63). It is tempting to speculate that these two individuals may carry an as-yet unidentified predisposition increasing risk for schizophrenia but protective against cancer.

We acknowledge there are limitations to our study. All functional experiments were performed using overexpressing constructs, which may not accurately reflect endogenous proteins. Moreover, the transfection of mutant alleles does not recapitulate the heterozygous state of the patient carriers, and so, may not accurately reflect their actual cancer risk. Additionally, HEK 293T cells contain neither ERBB2 nor other EGFR family members that form heterodimers with ERBB2. While this allowed us to isolate the effect of the SM and DM on downstream ERBB2 signaling -- our primary goal -- it did not allow us to investigate possible modifying effects of other family members on signaling.

In conclusion, based upon our integrated genomic and functional analysis, we propose that germline variation stabilizing ERBB2 and activating downstream ERBB2 signaling predisposes to cancer, with increased signaling resulting in increased penetrance, modified by ancestral or private familial factors. Although considerable work remains in order to validate this intriguing hypothesis in large numbers of patients and other families, it will be of considerable interest to explore further the potential role(s) of the rare I654V variant and the common I655V polymorphism in human cancer.

Supplementary Material

Statement of significance:

By performing whole exome sequencing on germline DNA from multiple cancer-affected individuals belonging to a family in which multiple cancer types track across three generations, we identified and then characterized functional common and rare variation in ERBB2 associated with both sporadic and familial cancer. Our results suggest that heritable variation activating ERBB2 signaling is associated with risk for multiple cancer types, with increases in signaling correlated with increases in risk, and modified by ancestry or family history.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HD0433871, CA129045 and CA40046 to K Onel; CA167824 to R Klein); the American Cancer Society – Illinois Division (K Onel); the Cancer Research Foundation (K Onel); the LUNGevity Foundation and Uniting Against Lung Cancer (now merged into Lung Cancer Research Foundation) (ZH Gümüş). R Bao acknowledges funding from the Hillman Fellows for Innovative Cancer Research Program. The work in the Barcelona Laboratory was funded by the generous donations from patients and families with neuroblastoma (NEN to J Mora, and Adrian Gonzalez Foundation to C Lavarino), and the “Biobanc de l’Hospital Infantil Sant Joan de Déu per a la Investigació” integrated in the National Network Biobanks of ISCIII.

We thank E Bartom for early development of the WES analysis pipelines, and M Jarsulic and F Mu for technical assistance in software installation and job execution on the high-performance computing (HPC) clusters. This work was supported in part through the computational resources and staff expertise provided by Center for Research Informatics at The University of Chicago, Center for Research Computing at The University of Pittsburgh, and the Department of Scientific Computing at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The current affiliation for ADS is Institute for Genomics and Systems Biology, the Center for Data Intensive Sciences, and Section of Genetic Medicine, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali MJ, Parsam VL, Honavar SG, Kannabiran C, Vemuganti GK, Reddy VA. RB1 gene mutations in retinoblastoma and its clinical correlation. Saudi J Ophthalmol 2010;24:119–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varley JM. Germline TP53 mutations and Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Hum Mutat 2003;21:313–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chek-Breast-Cancer-Case-Control-Consortium. CHEK2*1100delC and susceptibility to breast cancer: a collaborative analysis involving 10,860 breast cancer cases and 9,065 controls from 10 studies. Am J Hum Genet 2004;74:1175–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meijers-Heijboer H, van den Ouweland A, Klijn J, Wasielewski M, de Snoo A, Oldenburg R, et al. Low-penetrance susceptibility to breast cancer due to CHEK2(*)1100delC in noncarriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Nat Genet 2002;31:55–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weischer M, Bojesen SE, Ellervik C, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. CHEK2*1100delC genotyping for clinical assessment of breast cancer risk: meta-analyses of 26,000 patient cases and 27,000 controls. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:542–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McClellan J, King MC. Genetic heterogeneity in human disease. Cell 2010;141:210–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper DN, Krawczak M, Polychronakos C, Tyler-Smith C, Kehrer-Sawatzki H. Where genotype is not predictive of phenotype: towards an understanding of the molecular basis of reduced penetrance in human inherited disease. Hum Genet 2013;132:1077–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009;25:1754–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 2012;9:357–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 2010;20:1297–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garrison E, Marth G. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. arXiv preprint arXiv:12073907 [q-bioGN] 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Challis D, Yu J, Evani US, Jackson AR, Paithankar S, Coarfa C, et al. An integrative variant analysis suite for whole exome next-generation sequencing data. Bmc Bioinformatics 2012;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009;25:2078–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38:e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, Cummings BB, Alfoldi J, Wang Q, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature 2020;581:434–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rentzsch P, Witten D, Cooper GM, Shendure J, Kircher M. CADD: predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47:D886–D94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindor NM, McMaster ML, Lindor CJ, Greene MH, National Cancer Institute DoCPCO, Prevention Trials Research G. Concise handbook of familial cancer susceptibility syndromes - second edition. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2008:1–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linderman MD, Brandt T, Edelmann L, Jabado O, Kasai Y, Kornreich R, et al. Analytical validation of whole exome and whole genome sequencing for clinical applications. BMC Med Genomics 2014;7:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esai Selvan M, Klein RJ, Gumus ZH. Rare, Pathogenic Germline Variants in Fanconi Anemia Genes Increase Risk for Squamous Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:1517–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esai Selvan M, Zauderer MG, Rudin CM, Jones S, Mukherjee S, Offit K, et al. Inherited Rare, Deleterious Variants in ATM Increase Lung Adenocarcinoma Risk. J Thorac Oncol 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Genomes Project C, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015;526:68–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honzik T, Magner M, Krijt J, Sokolova J, Vugrek O, Beluzic R, et al. Clinical picture of S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase deficiency resembles phosphomannomutase 2 deficiency. Mol Genet Metab 2012;107:611–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stender S, Chakrabarti RS, Xing C, Gotway G, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Adult-onset liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma in S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab 2015;116:269–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mavaddat N, Dunning AM, Ponder BAJ, Easton DF, Pharoah PD. Common Genetic Variation in Candidate Genes and Susceptibility to Subtypes of Breast Cancer. Cancer Epidem Biomar 2009;18:255–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frank B, Hemminki K, Wirtenberger M, Bermejo JL, Bugert P, Klaes R, et al. The rare ERBB2 variant Ile654Val is associated with an increased familial breast cancer risk. Carcinogenesis 2005;26:643–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto H, Higasa K, Sakaguchi M, Shien K, Soh J, Ichimura K, et al. Novel Germline Mutation in the Transmembrane Domain of HER2 in Familial Lung Adenocarcinomas. Jnci-J Natl Cancer I 2014;106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dahabreh IJ, Murray S. Lack of replication for the association between HER2 I655V polymorphism and breast cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol 2011;35:503–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma Y, Yang J, Zhang P, Liu Z, Yang Z, Qin H. Lack of association between HER2 codon 655 polymorphism and breast cancer susceptibility: meta-analysis of 22 studies involving 19,341 subjects. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;125:237–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tao W, Wang C, Han R, Jiang H. HER2 codon 655 polymorphism and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;114:371–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu PH, Huang XF. Lack of association between HER2 codon 655 polymorphism and breast cancer susceptibility was not credible: appraisal of a recent meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;125:597–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishna BM, Chaudhary S, Panda AK, Mishra DR, Mishra SK. Her2 (Ile)655(Val) polymorphism and its association with breast cancer risk: an updated meta-analysis of case-control studies. Sci Rep 2018;8:7427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karunagaran D, Tzahar E, Beerli RR, Chen X, Graus-Porta D, Ratzkin BJ, et al. ErbB-2 is a common auxiliary subunit of NDF and EGF receptors: implications for breast cancer. Embo J 1996;15:254–64 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moasser MM. The oncogene HER2: its signaling and transforming functions and its role in human cancer pathogenesis. Oncogene 2007;26:6469–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woods Ignatoski KM, Grewal NK, Markwart S, Livant DL, Ethier SP. p38MAPK induces cell surface alpha4 integrin downregulation to facilitate erbB-2-mediated invasion. Neoplasia 2003;5:128–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.GrausPorta D, Beerli RR, Daly JM, Hynes NE. ErbB-2, the preferred heterodimerization partner of all ErbB receptors, is a mediator of lateral signaling. Embo J 1997;16:1647–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bocharov EV, Mineev KS, Volynsky PE, Ermolyuk YS, Tkach EN, Sobol AG, et al. Spatial structure of the dimeric transmembrane domain of the growth factor receptor ErbB2 presumably corresponding to the receptor active state. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008;283:6950–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mineev KS, Bocharov EV, Pustovalova YE, Bocharova OV, Chupin VV, Arseniev AS. Spatial structure of the transmembrane domain heterodimer of ErbB1 and ErbB2 receptor tyrosine kinases. J Mol Biol 2010;400:231–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen SL, Lin ST, Tsai TC, Hsiao WC, Tsao YP. ErbB4 (JM-b/CYT-1)-induced expression and phosphorylation of c-Jun is abrogated by human papillomavirus type 16 E5 protein. Oncogene 2007;26:42–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fry WHD, Simion C, Sweeney C, Carraway KL 3rd. Quantity control of the ErbB3 receptor tyrosine kinase at the endoplasmic reticulum. Molecular and cellular biology 2011;31:3009–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takaoka Y, Uchinomiya S, Kobayashi D, Endo M, Hayashi T, Fukuyama Y, et al. Endogenous Membrane Receptor Labeling by Reactive Cytokines and Growth Factors to Chase Their Dynamics in Live Cells. Chem 2018;4:1451–64 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Birnbaum D, Sircoulomb F, Imbert J. A reason why the ERBB2 gene is amplified and not mutated in breast cancer. Cancer Cell International 2009;9:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chmielecki J, Ross JS, Wang K, Frampton GM, Palmer GA, Ali SM, et al. Oncogenic alterations in ERBB2/HER2 represent potential therapeutic targets across tumors from diverse anatomic sites of origin. Oncologist 2015;20:7–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li BT, Ross DS, Aisner DL, Chaft JE, Hsu M, Kako SL, et al. HER2 Amplification and HER2 Mutation Are Distinct Molecular Targets in Lung Cancers. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:414–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lastowska M, Cotterill S, Bown N, Cullinane C, Variend S, Lunec J, et al. Breakpoint position on 17q identifies the most aggressive neuroblastoma tumors. Gene Chromosome Canc 2002;34:428–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marotta M, Chen X, Inoshita A, Stephens R, Budd GT, Crowe JP, et al. A common copy-number breakpoint of ERBB2 amplification in breast cancer colocalizes with a complex block of segmental duplications. Breast Cancer Res 2012;14:R150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brennan PJ, Kumagai T, Berezov A, Murali R, Greene MI. HER2/Neu: mechanisms of dimerization/oligomerization (vol 19, pg 6093, 2000). Oncogene 2002;21:328– [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brix DM, Clemmensen KK, Kallunki T. When Good Turns Bad: Regulation of Invasion and Metastasis by ErbB2 Receptor Tyrosine Kinase. Cells 2014;3:53–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bargmann CI, Hung MC, Weinberg RA. The neu oncogene encodes an epidermal growth factor receptor-related protein. Nature 1986;319:226–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arpel A, Sawma P, Spenle C, Fritz J, Meyer L, Garnier N, et al. Transmembrane Domain Targeting Peptide Antagonizing ErbB2/Neu Inhibits Breast Tumor Growth and Metastasis. Cell Rep 2014;8:1714–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamamoto H, Toyooka S, Ninomiya T, Matsumoto S, Kanai M, Tomida S, et al. Therapeutic Potential of Afatinib for Cancers with ERBB2 (HER2) Transmembrane Domain Mutations G660D and V659E. Oncologist 2018;23:150–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gallagher S, Hughes E, Wagner S, Tshiaba P, Rosenthal E, Roa BB, et al. Association of a Polygenic Risk Score With Breast Cancer Among Women Carriers of High- and Moderate-Risk Breast Cancer Genes. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e208501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muranen TA, Greco D, Blomqvist C, Aittomaki K, Khan S, Hogervorst F, et al. Genetic modifiers of CHEK2*1100delC-associated breast cancer risk. Genet Med 2017;19:599–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. New Engl J Med 2001;344:783–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Slamon DJ, Godolphin W, Jones LA, Holt JA, Wong SG, Keith DE, et al. Studies of the Her-2/Neu Proto-Oncogene in Human-Breast and Ovarian-Cancer. Science 1989;244:707–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tateishi M, Ishida T, Mitsudomi T, Kaneko S, Sugimachi K. Prognostic Value of C-Erbb-2 Protein Expression in Human Lung Adenocarcinoma and Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. Eur J Cancer 1991;27:1372–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muzny DM, Bainbridge MN, Chang K, Dinh HH, Drummond JA, Fowler G, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2012;487:330–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Izycka-Swieszewska E, Wozniak A, Drozynska E, Kot J, Grajkowska W, Klepacka T, et al. Expression and significance of HER family receptors in neuroblastic tumors. Clin Exp Metastasis 2011;28:271–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mora J, Gerald WL. Origin of neuroblastic tumors: clues for future therapeutics. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2004;4:293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cresti N, Lee J, Rourke E, Televantou D, Jamieson D, Verrill M, et al. Genetic variants in the HER2 gene: Influence on HER2 overexpression and loss of heterozygosity in breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 2016;55:27–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Furrer D, Lemieux J, Cote MA, Provencher L, Laflamme C, Barabe F, et al. Evaluation of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in normal and breast tumor tissues and their link with breast cancer prognostic factors. Breast 2016;30:191–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Puputti M, Sihto H, Isola J, Butzow R, Joensuu H, Nupponen NN. Allelic imbalance of HER2 variant in sporadic breast and ovarian cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 2006;167:32–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barak Y, Achiron A, Mandel M, Mirecki I, Aizenberg D. Reduced cancer incidence among patients with schizophrenia. Cancer 2005;104:2817–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li H, Li J, Yu X, Zheng H, Sun X, Lu Y, et al. The incidence rate of cancer in patients with schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Schizophr Res 2018;195:519–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.