Abstract

Purpose:

Maternal nutrition is a key modifier of fetal growth and development. However, many maternal diets in the U. S. don’t meet nutritional recommendations. Dietary supplementation is therefore necessary to meet nutritional goals. The effects of many supplements on placental development and function are poorly understood. In this review we will address the therapeutic potential of maternal dietary supplementation on placental development and function in both healthy and complicated pregnancies.

Methods:

This is a narrative review of original research articles published between Feb 1970 – July 2020, pertaining to dietary supplements consumed during pregnancy, and reporting placental outcomes (including nutrient uptake, metabolism and delivery, growth and efficiency). Impacts of placental changes on fetal outcomes were also reviewed. Both human and animal studies were included.

Findings:

We found evidence for potential therapeutic benefit of several supplements on maternal and fetal outcomes, via their placental impacts. Our review supports a role for probiotics as a placental therapeutic, with effects including improved inflammation and lipid metabolism, which may prevent preterm birth and poor placental efficiency. Supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids (as found in fish oil) during pregnancy tempers the negative effects of maternal obesity, but may have little placental impact on healthy lean women. The beneficial effects of choline supplementation on maternal health and fetal growth are largely due to its placental impacts. L-arginine supplementation was found to have a potent pro-vascularization effect on the placenta which may underlie its fetal growth-promoting properties.

Implications:

The placenta is exquisitely sensitive to dietary supplements. Pregnant women should consult their healthcare provider before continuing with or initiating a dietary supplement. As little is known about impacts of many supplements in placental and long term offspring health, more research is required before robust clinical recommendations can be made.

Keywords: placenta, dietary supplement, growth, nutrients

Introduction

Adequate fetal growth and development depends on a mother’s diet, her metabolic milieu, and placental function. Both undernutrition and excess nutrients are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes(1). Improved dietary intake may alter deleterious outcomes by modulating placental inflammation, oxidative stress, metabolism, and growth(2). Many pregnant women do not consume recommended amounts of essential nutrients, and maternal dietary supplementation has been proposed as an alternative.

A recent analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 1999–2014 found that 77% of pregnant women take dietary supplements compared to 44.8% of non-pregnant and non-lactating women (3). Furthermore, over 10% of pregnant women are supplementing with something other than a standard prenatal vitamin (3). Data from 501 couples planning a pregnancy showed that of women using supplements more than once a week in the last 3 months, 63% used multivitamins, while 13.2% supplemented with fish oil, and others supplemented with Echinacea (3.4%), gingko biloba (1%), and/or St John’s wort (1.2%) (4). Effects of many of these supplements on maternal health and pregnancy outcomes is understudied. The placenta is exquisitely sensitive to the maternal nutritional environment, and thus dietary supplementation in pregnancy is likely to impact placental development and function, which may ultimately affect fetal nutrient delivery and growth.

Within, we will review the therapeutic potential of non-standard dietary supplements on placental development and function in healthy and complicated pregnancies. Micronutrients such as the vitamins and minerals typically contained in prenatal supplements, are well-studied and their effects on placental function have recently been reviewed (5,6). Rather, we will highlight increasingly popular supplements (e.g. omega-3 fatty acids and probiotics), and those that show therapeutic promise (choline, arginine) but whose placental impacts are largely unrecognized.

Methods

To identify articles pertinent to this review, we conducted a PubMed search using the terms “dietary supplements” and “placenta“ published previous to July 2020. We prioritized RCTs, longitudinal observational studies, and cohort studies. We included only full text English language peer-reviewed publications. Studies were grouped by nutrient and/or compound, i.e. “amino acids”, “lipids”, “probiotics”. Supplements the focus of >5 original research articles reporting placental outcomes were chosen for narrative review, those with fewer articles were listed in Table. Human, animal, and in vitro studies were included.

TABLE.

Other dietary supplement studies with reported placental outcomes

| REFERENCE | SUPPLEMENT | MODEL | PLACENTAL OUTCOME | FETAL OUTCOME |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YIMAM 2015 (102) | Botanical Composition UP446 | Rat/Rabbit | No effect on placental weight | No effect on fetal weight, malformations mortality or sex ratios. |

| PRATER 2006 (103) | Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) | Mouse | ↓ placental damage in mice exposed to Methylnitrosourea midgestation. | Improved fetal limb development in mice exposed to Methylnitrosourea midgestation. |

| NAKANO 2005 (104) | Chlorella pyrenoidosa | Human | ↓ developmental toxicants (polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans) | ↑ birth weight |

| MATHEW 2018 (105) | DHA and EPA | Human | ↑ Angiogenic potential of placental mesenchymal stem cells | N/A |

| SMIT 2014 (106) | DHA and EPA | Pigs | ↑ placental weight | ↓ decrease litter size |

| GRIFFITHS 2007 (107) | D-Ribose | Rat | No effect on placental weight | No effect on fetal weight, malformations mortality or sex ratios. |

| PENG 2019 (108) | EPA | Mouse | ↑ inflammation and promotion of angiogenesis | ↑ fetal weight |

| LIN 2011 (109) | Fiber and N-acetylcysteine (NAC) | Rat | ↑ superoxide anion, hydroxyl radical scavenging capacities, protein carbonyl concentrations, placental weight and GLUT3 expression in fiber + high-fat diet group only. Few effects with NAC. | ↑ litter size and fetal liver total superoxide dismutase |

| LIN 2012 (110) | Fiber | Rat | ↑ copper-zinc superoxide dismutase and manganese superoxide dismutase | ↑ litter size and fetal copper-zinc superoxide dismutase. |

| WANG 2018 (111) | Leucine | Sow | ↑ amino acid transporter expression (SNAT1, SNAT2, LAT1) | ↑ birth weight |

| CRUZ 2016 (112) | Leucine | Rat | ↑ DNA, protein content, mTOR pathway expression, antioxidant capacity ↓ lipid peroxidation induced by tumor and ascites |

↑ fetal weight |

| VIANA 2015 (113) | Leucine | Mouse | ↓ the impact of cancer on placental function by improving the cell-signaling activity and reducing the proteolytic process. | ↑ fetal weight |

| ELMES 2004 (114) | Linoleic Acid | Sheep | ↑ prostaglandin production | ↑ LCPUFA in fetal circulation |

| CHENG 2005 (115) | Linoleic Acid | Sheep | ↑ prostaglandin production | N/A |

| CHENG 2011 (116) | Linoleic acid; γ-linolenic acid; arachidonic acid | Sheep | ↓ prostaglandin production | N/A |

| LIU 2019 – 1 (117) | L-proline | Mouse | ↑ amino acid and glucose transporters and angiogenic pathways (VEGF) @ E12.5 | ↑ litter size |

| LIU 2019 – 2 (118) | L-proline | Mouse | ↑ polyamines (putrescine and spermidine) | No effect on fetal weight or survival from F1 dams |

| SHARMA 2014 (119) | Mannose | Mouse | Mannose-6-P accumulation; grossly disorganized placenta | ↓ litter size and survival ↑ eye defects |

| BATISTEL 2017 (120) | Methionine | Cow | ↑ SLC7A5, mTOR | ↑ birth weight |

| BATISTEL 2019 (121) | Methionine | Cow | ↑ TCA metabolites and markers of mitochondrial function; increased DNMT3A expression (Female only) | ↑ calf growth 0–9 wk |

| CHEN 2018 (122) | Methionine | Mouse | ↑ glucose and amino acid transporters | ↑ litter size and fetal wt in Metionine deficient pregnancies |

| LUO 2019 (123) | N-acetyl-cysteine | Pigs | ↑ IGFs, E-cadherin, angiogenesis genes, amino acids transporters, antioxidant markers. ↓ autophagy markers, MDA and inflammation |

↑ relative abundances of fecal Prevotella, Clostridium cluster XIVa, and Roseburial/Eubacterium rectale |

| VAN DEN BOSCH 2019(124) | Nitrate | Pigs | ↑ placental width | ↑ Probability of a higher vitality score (movement and breathing) |

| CAPOBIANCO 2018 (125) | Oleic Acid | Rats | ↓ mTOR, lipoperoxidaBon, inflammation in model of GDM | ↓ fetal overgrowth |

| CHENG 2015 (126) | Oleic Acid | Sheep | ↑ prostaglandin production | N/A |

| PARRISH 2013 (127) | Phytonutrient | Human | No change in “placenta-related morbidity” (composite of IUGR, PPROM, PTD, pregnancy loss) | No change in birthweight, mortality, APGAR |

| LIM 2013 (128) | Phytophenols (curcumin, naringenin and apigenin) | Human | ↓ LPS-stimulated IL-6 and IL-8, COX-2, prostaglandins, oxidative stress and MMP-9. Naringenin alone ↓ IL-1β-induced IL-6 and IL-8. ↓ NF-kB p65 DNA-binding activity |

In fetal membranes: ↓ LPS-stimulated I L-6 and IL-8, COX-2, prostaglandins, oxidative stress ↓ NF-kB p65 DNA-binding activity |

| YANG 2019 (129) | Quercetin | Rats | ↓ MDA in preeclamptic dams when given with aspirin | ↑ fetal:placental weight in preeclamptic dams when given with aspirin |

| ARITA 2019 (130) | Sulforaphane | Human | ↑ antioxidant HO-1 and sgp130 ↓ IL-1β and IL-10 ↓ IL-6 and BDNF with and without cotreatment with E.coli. |

N/A |

FATTY ACIDS

The fetoplacental unit requires fatty acids (FA) as a source of energy, to build cell membranes, and as precursors to bioactive compounds. Humans cannot synthesize FA de novo with double bonds three (omega/n-3) or six (n-6) carbons from the omega terminus, thus these long-chain polyunsaturated FA (LCPUFA) must be obtained from the diet, or derived from essential FA precursors. Of the LCPUFA, arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4 n-6), eicosapentaenoic (EPA, 20:5 n-3), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6 n-3) are metabolically the most important (7). The major dietary source of the n-3 LCPUFAs are fish and seafood, particularly oily fish (8,9). Following the 2001 federal advisory regarding methylmercury contamination in certain fish species, only 11% of women consumed more than the recommended 2–3 fish servings per week during pregnancy (10,11).

Interest in n-3 FA intake during pregnancy began in the 1980s when Danish investigators noted that women in the Faroe Islands with a high fish intake delivered babies that were 194 g heavier and gestated 4 days longer than babies born in Denmark (12). Since then, n-3 FAs have been found to enhance neurodevelopment and lower risk of allergic diseases early in postnatal life (13). Correspondingly, deficiencies in n-3 FA during pregnancy are associated with poor developmental outcomes in offspring, including reduced visual acuity, risk of obesity and cardiometabolic disease (diabetes, hypertension) in later life (14). The fetoplacental unit is unable to synthesize sufficient levels of n-3 LCPUFA from their precursor FA, therefore maternal n-3 FA supply and placental transport is critical to fetal delivery.

Omega-3 FA affect placental fatty acid uptake and incorporation

FA are released at the placental surface from maternal triglycerides (TG) and phospholipids (PL), and n-3 FA uptake and transfer to the fetus may depend upon the carrier (15,16). This packaging of n-3 FA differs depending on the source of the supplement (e.g. fish oils, single cell microalgae oils, krill oils, and egg yolk extracts). Gazquez et al. found that PL-DHA was taken up at higher rates than TG-DHA by the placenta, but fetal brain accretion did not differ between the two sources (16). This demonstrates that DHA may be processed differently in the placenta depending on the supplement source.

FA enter the syncytiotrophoblast layer of the placenta most efficiently by transporters, such as FA transport proteins (FATP) (17). Inside the cytosol FAs are oxidized for energy, metabolized into lipid signaling compounds, or re-esterified and incorporated as PL into membranes or deposited as TG and hydrolyzed for later release into the fetal circulation. Maternal DHA supplementation (800 mg/d) from week 26 to term resulted in higher placental membrane DHA content in a randomized control trial (RCT) of 30 women with obesity, compared to placebo group (18). Placental membrane DHA was associated with a reduction in placental amino acid transport and inflammatory markers, along with an increase in FA transport capacity (18). Consistent with this, Larque et al, showed that FATP-1 and FATP-4 expression correlated with PL-DHA in placentas of overweight women (19). These findings suggest that DHA content of placental membranes, elevated by maternal supplementation, alters nutrient transport capacity.

Omega-3 FA modify placental lipid metabolism and accumulation

Placentas of women with obesity display greater lipid accumulation, inflammation and oxidative stress (OS) compared to women without obesity, a characteristic of lipotoxicity (20,21). This lipid accumulation may be caused by impaired FA oxidation or increased esterification; which ultimately may affect lipid supply to the fetus (20,22,23). In a secondary analysis of an RCT in a US mid-western population, Calabuig-Navarro et al. showed that fish oil supplementation (1200 mg/d EPA + 800 mg/d DHA) of overweight and obese women during pregnancy decreased placental lipid accumulation by 28%, and downregulated FA esterification pathways in the placenta (25). Moreover, both combined and separately, DHA and EPA inhibited esterification of the saturated FA [3H]-palmitate in vitro in primary trophoblast cells isolated from women with obesity (25). Thus, supplementation of n-3 FA during pregnancy may ameliorate the effects of obesity on FA accumulation in the placenta. Studies comparing women in a high vs low fish intake region explored whether high n-3 FA consumption in the form of whole foods could lessen the impact of obesity on placental lipid metabolism. Women from Hawaii had 8-fold higher DHA levels than Ohioan women, and maternal obesity in Hawaiian women was not associated with placental lipid accumulation or alterations in lipid metabolism pathways observed in Ohioan women (20,26), suggesting therapeutic potential for dietary fish intake.

Omega-3 FA reduce placental inflammation and oxidative stress

Accumulation of macrophages and pro-inflammatory mediators in placentas of women with obesity may be linked to high lipid accumulation and lipotoxic phenotype (21,27). The anti-inflammatory impacts of DHA and EPA in the placenta are well documented in animal experiments, where they decrease production of eicosanoids, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and relieve OS by inhibiting the NF-κB and MAPK pathway (28–30). Using human placental explants, Melody et al. found that pre-exposure to 20 μM individual n-3 FA resulted in reduced IL-6 levels, whereas exposure to complex FA mixtures (total 600 μM) enriched in n-3 FA resulted in a modest but significant stimulation of IL-6 production (31). Thus, the effect of n-3 FA on placental cytokine expression may be influenced by quantity and composition of FA exposure.

Placental concentration of IL-6 or TNFα did not differ between women with high (≥ three fatty fish meals per week, excluding fried fish) or low (< two fish meals per week) fish intake in late pregnancy, however, differences in maternal n-3 FA levels were not detected between groups in this observational study (31). Overweight and obese women randomly assigned to n-3 FA (2g/day) from week 10–16 of pregnancy to term exhibited a significant decrease in placental toll-like-receptor (TLR) 4 expression and IL-6, IL-8, and TNFα as compared to placebo. In vitro studies in primary human trophoblast cells confirmed that EPA and DHA suppressed the activation of TLR4, IL-6, and IL-8 induced by palmitate (32). Together these results suggest that measurable increases in maternal DHA are capable of altering placental inflammatory cytokine levels and blunt responses to inflammatory stimuli.

Recently, a class of n-3 LCPUFA derived mediators has been identified, known as specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators (SPM), which includes the resolvins, protectins and maresins (33). The SPMs have potent immunoresolving properties, preventing destructive effects of unrestrained chronic inflammation and promoting the return to homeostasis (34,35). Keelan et al, found that 3.7 g/d n-3 FA (2.1g DHA + 1g EPA) supplementation during pregnancy enhanced placental accumulation of DHA and SPM precursors, though inflammatory gene expression was not altered in the non-obese participants (36).

Excessive formation of reactive free radicals in the placenta can damage cell structure and increase the risk of pregnancy and fetal disorders (37). N-3 FA supplementation can have both pro and anti-oxidant effects depending on experimental conditions, dosage, timing, content of the supplement and background diet (9,38). In an in vitro study, term and pre-term placental explants were exposed to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), DHA (1, 10, 100μM), and DHA + LPS (39). While DHA reduced LPS-induced OS in all explants, DHA alone at high levels induced OS in term explants. In the pre-term explants, DHA alone induced OS at all three concentrations, demonstrating that pre-term placentas are particularly sensitive to DHA (39). Conversely, no evidence of increased OS was detected in term placenta from women with obesity in response to DHA supplementation in vivo (18). Discrepancies between in vitro and in vivo effects suggest that timing, dosage, and the cellular milieu all influence impacts of FA on OS, and carefully designed experiments are needed.

Omega-3 fatty acids affect placental apoptotic markers

Placental apoptosis is important for normal trophoblast differentiation and proliferation. In a rat model of preeclampsia with high apoptosis, supplementation with fish oil and vitamin E reduced the apoptotic markers caspase 8 and 3 in the placenta (40). Consistent with this, in 28 healthy pregnant women supplemented with 300mg DHA from week 20 until delivery, caspase 3 activity was significantly lower in the DHA group (41). Conversely, no effect of supplementation on placental apoptosis or proliferation was detectable in 16 healthy women receiving 500mg/150mg DHA/EPA from week 20 until delivery (42). Current evidence supports a potential anti-apoptotic role for n-3 FA in the placenta, but larger RCTs are required.

Impact of supplementation may depend on individual characteristics

The impact of n-3 FA supplementation on fetal outcomes may depend on placental function, current diet and individual characteristics. In data from >1500 women participating in the DOMInO trial, the number of DHA capsules consumed over the course of pregnancy explained < 35% of the variation in DHA abundance in cord plasma at delivery (43). A secondary analysis emphasized that heterogeneity of the sample may mask the benefit of the intervention; for example, women who smoked in the preconception period did not benefit from the supplementation (44). In women with GDM, there is a significant discrepancy in plasma n-3 FA levels between the mother and neonate (45,46), hypothesized to be due to an impairment of placental FA transport (47). Low expression of major facilitator superfamily domain-containing protein 2 (MFSD2a) may reduce placental n-3 FA transfer in women with GDM, impeding the accretion of fetal n-3 FA (48). Indeed, DHA supplementation of women with GDM effectively enhances maternal, but not fetal DHA status, which was attributed to placental abnormalities linked to GDM (49).

Summary

Omega-3 FA supplementation has substantial potential to modify the placental environment during pregnancy, particularly in overweight and obese women (Figure 1). However, inter-individual variability in the placental and fetal impact may be due to supplement source, heterogeneity of maternal characteristics, and impairments in FA transfer capacity. The impact of fetal sex on response to maternal LCPUFA supplementation is unclear and requires further study. Moreover, dosage and timing of supplementation need further investigation to better understand the effects of supplementation, as an excess of omega-3 FA may also increase oxidative damage to the placenta.

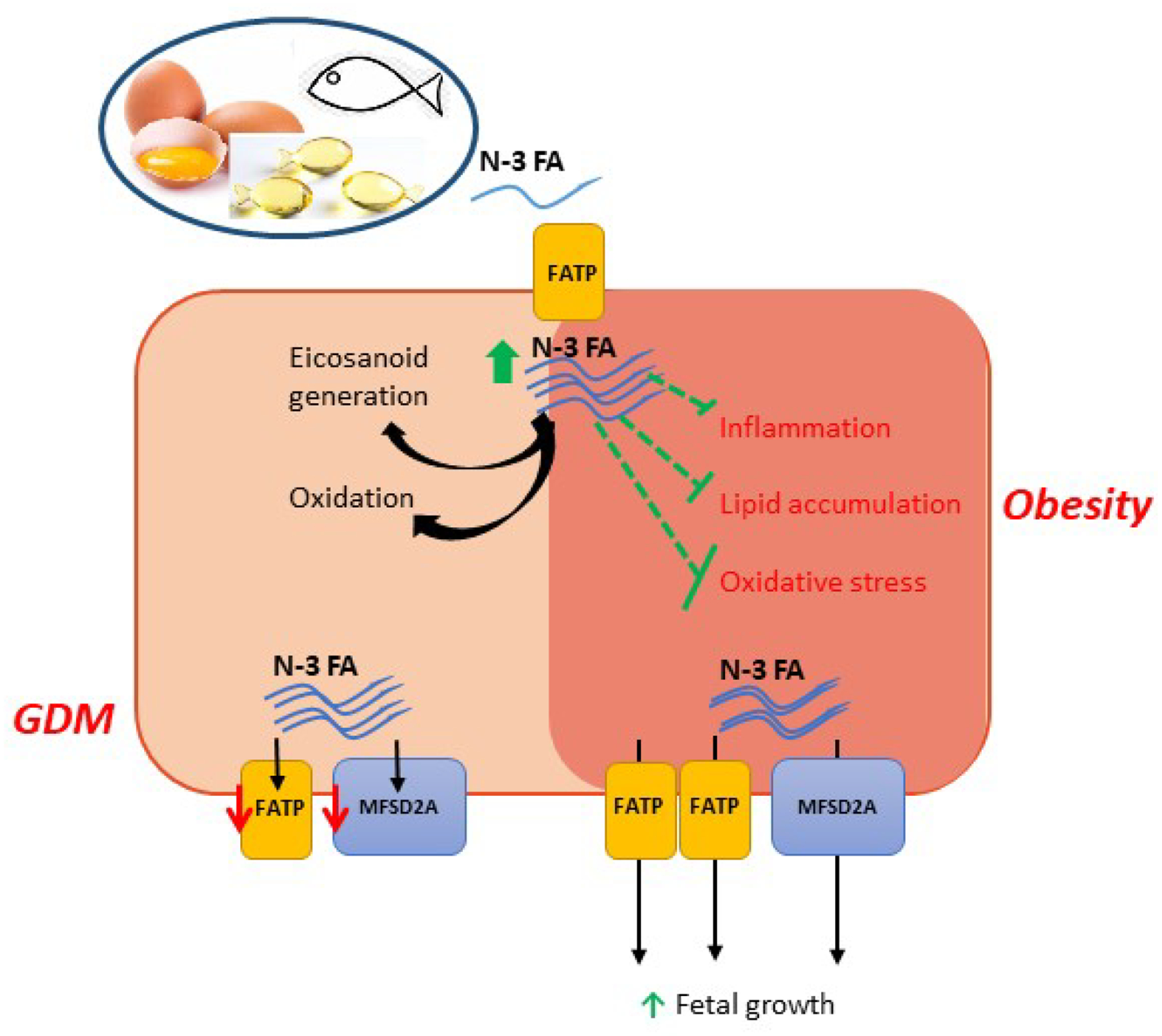

Figure 1.

Impact of omega-3 fatty acid (n-3 FA) supplementation on placental function in women with obesity and gestational diabetes (GDM). Supplementation with n-3 FA lowered (green lines) inflammation, lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in women with obesity. Additionally, placental FA transport capacity increased, impacting fetal growth. N-3 FA supplementation in GDM women improved maternal more than neonatal plasma levels, potentially due to impairment of placental FA transporters

CHOLINE

Now recognized as an essential nutrient, choline is a cation that forms salts. Choline is an integral part of the phospholipid phosphotidylcholine (PC) which is an important component of cell membranes throughout the body. Choline deficiency has been associated with fatty liver and muscle damage secondary to lipid metabolism dysfunction (as reviewed by Zeisel et al. (50)). During pregnancy, low choline levels (150 mg/d; recommended adequate intake >450 mg/d) may lead to neural tube defects in the fetus (51). Choline can be generated endogenously, but is mainly sourced from the diet – namely meat, eggs and milk. High levels of estrogen found in pregnant women support enhanced choline synthesis in the liver by stimulating phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PEMT) (52), but as less than 10% of pregnant women in the US consume enough choline from dietary sources (53), and prenatal vitamins do not routinely contain choline, it has been argued that pregnant women should supplement with choline (50).

Using deuterium-enriched choline, Yan et al. found with enhanced requirements for choline during pregnancy, choline metabolism is shifted away from PEMT-driven PC synthesis and toward an alternate pathway (54). Interestingly, PC synthesized via the PEMT pathway are selectively partitioned to the fetus, likely due to their enrichment in DHA. Women supplemented with 930 mg/d of choline (~2x the recommended intake), had higher PEMT-PC levels (54), suggesting that higher than currently recommended levels of choline supplementation in pregnancy may increase the transport of DHA-enriched PC to the fetus. Choline can also impact fetal nutrient delivery and growth by directly modulating nutrient transporters in the placenta.

Choline modifies placental nutrient uptake and metabolism

Using a mouse model of maternal obesity, Nam et al. reported that many of the growth stimulatory and placental nutrient handling impacts of a maternal high fat diet (HFD: 60% dietary fat; normal fat: 10%) were reversed by simultaneously supplementing with 25mM choline in the drinking water (55). Interestingly, choline did not modify the HFD effect on maternal weight gain or glucose tolerance. Specifically, choline supplementation reversed or blunted HFD-induced increases in placental growth, GLUT1 and FATP1 mRNA expression, triglyceride and glycogen concentration (55). These placental effects of choline occurred simultaneously with decreases in HFD-stimulated fetal growth. Consistent with these data, Nanobashvilli et al. reported that supplementation with 25mM choline or its metabolite betaine mitigated the effect of a HFD on placental glycogen accumulation in a mouse model of obesity (56). The direct effect of both compounds was confirmed in vitro using the BeWo trophoblast cell line, where the stimulatory effect of high glucose on glucose and FA uptake was moderated by choline and betaine individually (56). Altogether, these findings suggest a role for choline supplementation in maintenance of placental nutrient metabolism and growth, and highlight choline as a potential dietary supplement with beneficial effects on fetal growth in obese women.

Choline supplementation decreases placental inflammation and apoptosis

In the Dlx3+/− mouse model of placental insufficiency, King et al. reported that maternal choline supplementation at 4x normal intake (5.6 g/kg vs 1.4 g/kg) increased the placental labyrinth area at E10.5 – the region responsible for nutrient transport and metabolism in the mouse (57). This growth occurred in parallel with decreased apoptosis in the placenta, and later in gestation, decreased inflammatory gene expression and angiogenic factors (57). These mechanisms may underlie previous findings that maternal choline supplementation improves placental efficiency and fetal growth in this model (58). Earlier reports have also shown that choline supplementation decreased placental inflammation during normal murine pregnancy in a sex- and gestational stage-specific manner (59), though fetal growth and placental efficiency was not altered. Of particular interest, choline’s impact on placental angiogenic pathways is sex-specific (59), with females largely demonstrating an inhibitory response to choline, whereas angiogenic pathways were stimulated by choline supplementation in male placentas in late pregnancy (57). Sex differences in placental growth responses to maternal nutritional milieu has been reported previously (60), and the above data suggests that placental response to choline is also dependent on fetal sex, though sexually dimorphic differences in fetal growth were not reported. Kwan et al. demonstrated that choline supplementation increased maternal spiral artery luminal area, perhaps by inhibiting apoptosis in these vessels (59). Maternal spiral artery diameter – which is smaller in Dlx3+/− mice – was not affected by choline supplementation in this model (57), suggesting that choline’s positive effects on fetal growth are independent of maternal vascular modifications.

Placental anti-angiogenic proteins are downregulated by choline supplementation in humans

Anti-angiogenic factors such as soluble FLT1 (sFLT1) and soluble endoglin are produced within the placenta and released into the maternal circulation where they can sequester pro-angiogenic factors such as VEGF, leading to maternal endothelial dysfunction (61). Thus, excessive production of these anti-angiogenic factors by the placenta may result in maternal hypertension and proteinuria, symptoms of preeclampsia (61). A controlled feeding study of adequate (480 mg/d) vs high (930 mg/d) choline intake during the third trimester of pregnancy by Jiang et al (62) showed that high dietary choline suppressed placental sFLT1 expression and production at term. Placental sFLT1 levels correlated with lower maternal circulating sFLT1, and were negatively associated with placental acetylcholine, a metabolite of choline. The in vivo observations were confirmed by in vitro experiments which verified that choline supplementation decreased sFLT1 mRNA and production in the HTR8 trophoblast cell line (62). Randomized controlled trials will be necessary to determine choline’s effectiveness in lowering rates of maternal hypertension and preeclampsia in at risk mothers.

Summary

The above evidence supports a beneficial role for choline supplementation in improving placental function in pregnancies complicated by maternal obesity, placental insufficiency and potentially maternal vascular dysfunction (Figure 2). These improvements in placental function were associated with increases in fetal growth, independent of maternal physiological changes, demonstrating a largely placental-specific impact that may vary with fetal sex. Choline has great promise as a dietary supplement that could improve placental function and fetal growth outcomes in at risk pregnancies, and deserves further study.

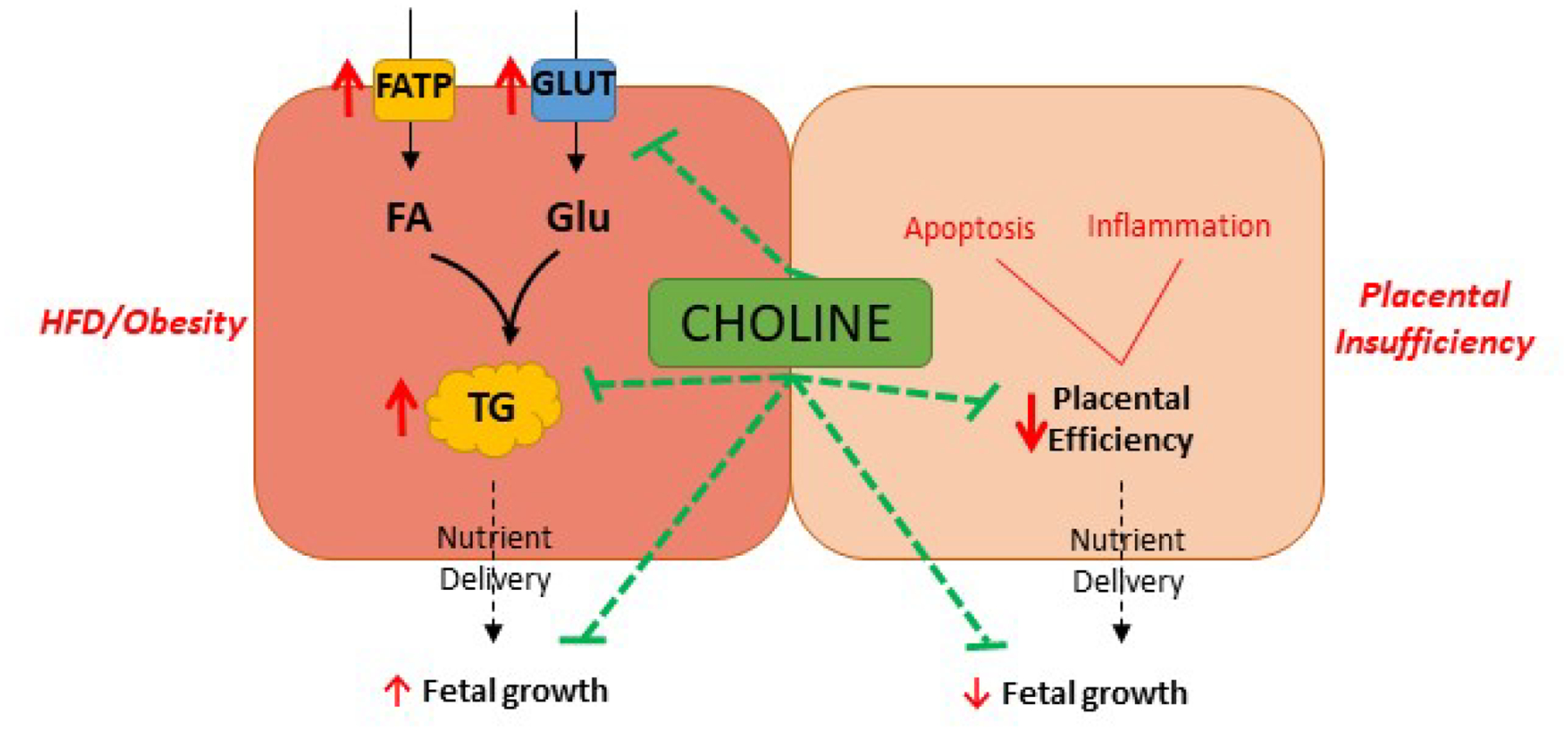

Figure 2.

Placental impacts of choline supplementation mediate fetal growth effects. Maternal choline supplementation results in higher placental choline and reverses (green lines) the stimulatory effects (red arrows) of maternal high fat diet (HFD) or obesity on placental nutrient transport and storage and fetal growth. In models of placental insufficiency, choline supplementation has anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects (green lines) that improve placental efficiency and fetal growth

PROBIOTICS

The World Health Organization defines probiotics as “live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host” (63); therefore there must be scientific evidence for health benefits. Probiotics are similar to beneficial microorganisms found naturally in the human gut and are readily available in the form of dietary supplementation and foods. Currently there is no recommended daily intake. Overall, probiotics are generally considered safe and are well tolerated, which would make them a good nutritional supplement for pregnant women. In fact a systematic review of over 1500 pregnant women who took probiotics during the third trimester showed that there was no increase in incidence of miscarriages or malformations, or changes in birthweight or gestational age at birth (64). Despite this, very little is known about probiotics’ health benefits to the placenta.

In healthy humans probiotics are generally taken in order to supplement the gut microbiota, which in turn plays a critical role in immune, metabolic and neurological functions. The fetal intestinal microbiota can be influenced as early as birth by mode of delivery, feeding, stress or infection, and rapidly matures from initial colonization at birth. The uterine environment has long been considered a sterile environment and it was thought that the neonatal microbiome is initially colonized at delivery and post-birth. Conflicting research currently exists on whether the placenta hosts a microbiome, with compelling data that both refutes (65) and supports (66) this idea. If the placenta does indeed have its own microbiome, it may be able to influence fetal microbiome whilst still in utero (67,68), which has implications for long-term health. Here we will collate studies that suggest that the placenta may be a beneficial therapeutic target for probiotics that requires further investigation.

Probiotics modulate inflammation

The most common bacteria species found in probiotics is of the lactobacillus variety; known for its immunomodulatory effects. This property of Lactobacillus is particularly relevant for research in the treatment of preterm birth which is linked to intrauterine and placental inflammation and infection. A study in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) showed associations between intake of milk containing probiotics during the first half of pregnancy and reduced risk of spontaneous preterm delivery (69). In the US alone, preterm birth complicates 9.85% of all pregnancies (70), and worldwide is the leading cause of infant mortality (71).

Studies in isolated primary placental cells from healthy term caesarian sections show reductions in inflammatory profiles using probiotics, thus demonstrating benefits when applied directly to the placenta. By using LPS to induce an inflammatory response in isolated primary trophoblast, both Lactobacillus Rhamnosus (LR) variants GR-1 and GG can induce anti-inflammatory effects via upregulation of colony-stimulating factor 3 (CSF3) (in placentas of female fetuses only) (72) and also downregulation of both protein and mRNA expression of TNFα (73,74), the latter being observed also in isolated amnion cells (75). These changes in trophoblasts are achieved without altering hormone production of β-HCG and progesterone, suggesting there is an immunomodulatory function without affecting overall function of these cells (73). Elevated expression of placental TNFα in particular has been shown to play a key role in infection-mediated preterm birth (76–78), as well as low infant serum levels of CSF3 (79), therefore modulation by probiotic administration is clinically significant. Interestingly, LR alone increases expression of anti-inflammatory interleukins IL-4, IL-10 in trophoblast (73,74) and IL-6 in amnion (75), which does not hold true when co-incubated with LPS. It is not clear yet how these cytokines contribute to the final maternal immune response and whether these changes influence preterm birth but maternal immune cells have been reported to cross the placenta and regulate fetal immune responses (80). It is important to note that there may be sex-specific effects of probiotics (72) which requires further examination, particularly in the context of increased risk of preterm birth for male fetuses (81).

The effect of probiotics on placental inflammation has also been studied in a model of allergy and asthma. In mice, 108 colony forming units (CFU)/2 days of freeze dried LR-GG was given before conception, during pregnancy and lactation in order to assess its anti-inflammatory effects on asthma and allergy in offspring (82). Maternal intestinal colonization was successful, and inflammatory markers in the offspring lung were downregulated. However, contrary to the offspring response, there was a significant increase in placental TNFα mRNA expression which indicates a pro-inflammatory environment. It is unclear why in vivo administration of LR would increase, rather than decrease, a pro-inflammatory response compared to the in vitro experiments outlined above. The authors suggest that the induction of a slight pro-inflammatory reaction (83,84) may lead to a down regulation of allergic immune responses (85), however this mechanism of action requires further investigation in this model. It is also critical to note that the route of supplement intake is intragastric which could affect placental response to probiotic supplementation.

In an RCT in Finland, Rautava et al., assessed the effect of Bifidobacterium Lactis (Bb12) with or without LR-GG (both 109 CFU/day) 14 days before elective caesarian procedure from healthy uncomplicated pregnancies on immune gene expression profiles in the placenta and fetal gut. Both Lactobacilli and Bifidobacterium DNA were detected in 100% and 41% the placentas respectively. Placental TLR expression was modulated by both Bb12 and LR-GG plus Bb12 with overall downregulated TLRs expression levels. TLRs form the major family of pattern recognition receptors (PRR) that are involved in innate immunity. This decrease in placental TLRs supports the in vitro experiments that show decreased pro-inflammatory markers in trophoblast and amnion cells. However, both bacterial and lactobacillus DNA in the placenta significantly increased the expression of TLR5 and TLR6 in the fetal gut (86). Previous research in mice demonstrates that neonatal TLR5 expression influences long term gut microbial composition via TLR5- mediated REG3γ counter-selection of colonizing flagellated bacteria (87). In addition, lower levels of TLR5 have been associated with metabolic changes including obesity (88). This study demonstrates that even short periods of probiotic supplementation during late pregnancy modulates the microbial and immune environment of the placenta which in turn can impact neonatal intestinal immune gene expression.

Probiotics modulate placental efficiency, antioxidant capacity and fatty acids

Another small RCT in Finland was conducted to assess the benefits of 109 CFU/day probiotic supplementation (LR-GG and Bb12) from 14 weeks gestation on placental phospholipid FA (89). FA which are incorporated into phospholipids are utilized to synthesize longer chain FA derivatives or inflammatory modulators. These FA also play an important role in fetal growth and development. Dietary counselling with probiotics resulted in higher concentrations of linoleic (18:2n-6) and di-homo-c linolenic acids (20:3n-6) compared with dietary counselling plus placebo or placebo alone. These pregnancies were uncomplicated, and infants delivered at term with no significant changes to birth weight or length between groups. Placental weight and efficiency were not measured in this study. However in sows, Gu et al, reported an increase in placental efficiency when supplemented with Bacillus variants, subtilis and lichenformis (2×1011CFU) in late pregnancy (90). This was associated with an increase in average piglet birth weight. In this study placental antioxidant capacity as measured by elevated total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) levels could explain the increased efficiency. However, levels of antioxidant enzymes glutathione peroxidase and catalase were reduced. This study noted lower levels of placental malondialdehyde (MDA), which is created via peroxidation of polyunsaturated FA and is a marker for OS. This, in addition to the previous study, tentatively suggest that these probiotics may be able to influence placental lipid composition and metabolism.

Summary

Overall, in vitro data shows compelling evidence for immunomodulatory effects of probiotics in the placenta that may be relevant for the treatment of preterm birth or other inflammatory diseases. Prenatal probiotic supplementation may provide a tool to modulate sex-specific fetal and placental inflammation via the placental microbial environment. In the current in vivo trials, dietary supplementation with probiotics has shown beneficial placental metabolism outcomes (Figure 3), however, more extensive human research is required to determine whether ingestion of probiotics leads to beneficial fetal outcomes. Future RCTs evaluating effects of probiotics on placental function, particularly in women susceptible to preterm birth, are warranted.

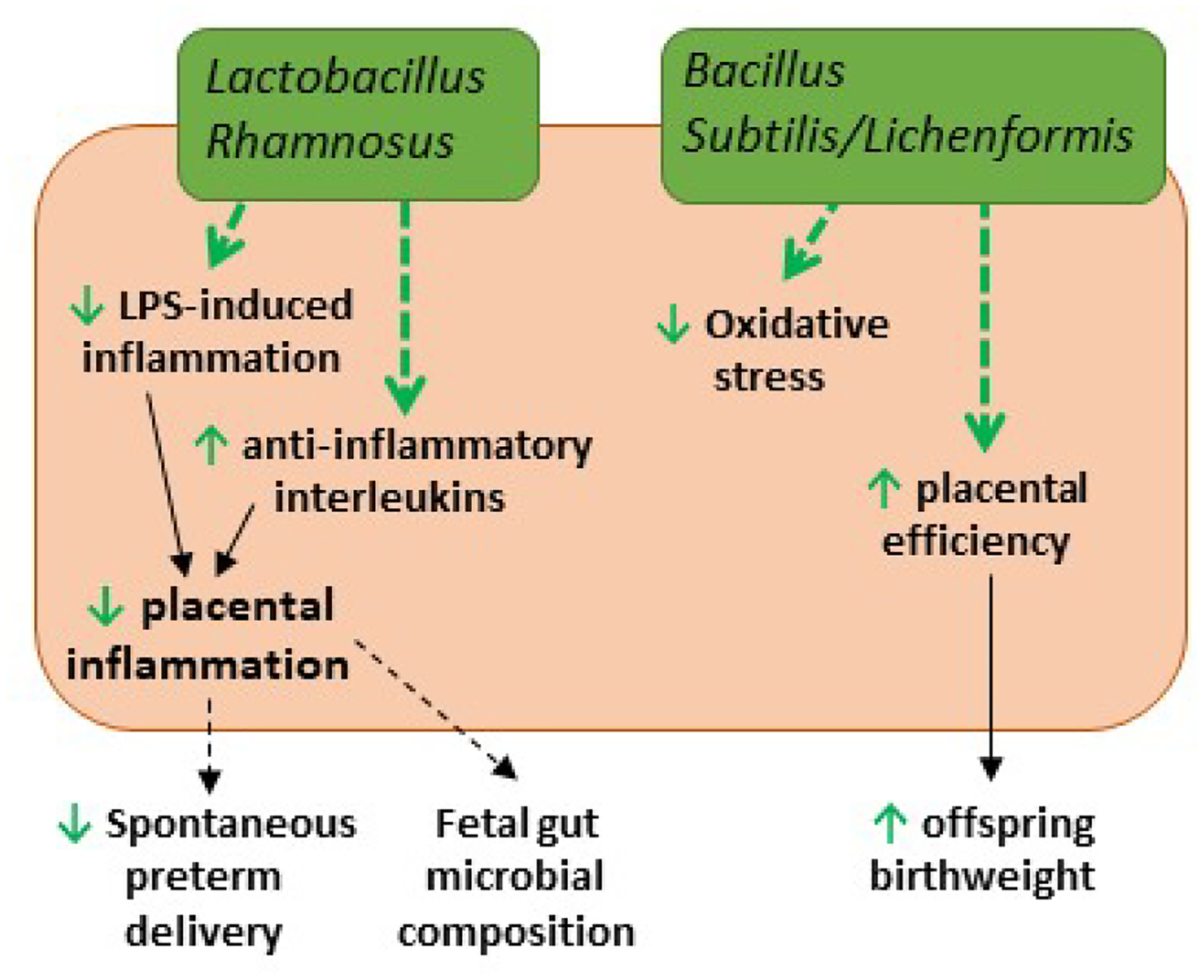

Figure 3.

Placental impacts of probiotic supplementation. Lactobacillus Rhamnosus supplementation reduces pro-inflammatory (TNF-α, TLRs) and increases anti-inflammatory (CSF3, IL-4, IL-10) pathways (green arrows) in human placental cells. This decreases overall placental inflammation which may decrease spontaneous preterm delivery and influence fetal gut composition (dotted black arrows). Bacillus subtilis/lichenformis decreases oxidative stress, and increases placental efficiency and offspring birthweight in sows (green arrows).

L-ARGININE

Targeted supplementation strategies, particularly for women in resource-poor settings where protein-rich foods such as meat and eggs are scarce, are increasingly of interest in order to prevent or moderate poor pregnancy outcomes such as preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction and gestational hypertension (91). Arginine is a nutritionally essential amino acid during gestation, when its metabolites (e.g. nitric oxide, proline, creatine) are in particularly high demand. Though most women in the US consume sufficient amounts of arginine during pregnancy (~4 g/d), several well-powered RCTs in high resource settings (as reviewed by Weckman et al. (91)) have shown that a low (3–4 g/d), long-term supplementation with L-arginine, beginning in early pregnancy, decreases risk of preeclampsia, fetal growth restriction and gestational hypertension. Some of these studies reported an increase in circulating NO and decreased umbilical resistance in women randomized to the supplement, suggesting that improvements in vascular function may be an underlying mechanism into L-arginine’s beneficial effects on outcomes. Similar trials have not yet been conducted among pregnant women in low resource settings that are even more likely to benefit from supplementation.

Based on data generated in pre-clinical models, to be reviewed below, it has been proposed that the placenta is an important target of L-arginine and may be the main mediator of this amino acid’s beneficial effects.

L-arginine and placental growth in normal pregnancy

The majority of studies have reported an increase in fetal growth following L-arginine supplementation during pregnancy, dependent on gestational stage. In sows, supplementation with 0.8% L-arginine for the first 25 days of gestation increased vascularity of the chorionic and allantoic membranes, but the number of fetuses and fetal weight was reduced compared to isonitrogenous controls (92). The same group found that supplementation with the same level of L-arginine starting 2 weeks after fertilization (GD 14–25) resulted in more fetuses, lower embryonic mortality, and increased placental weight at GD 25 compared to isonitrogenous controls (93), suggesting that the timing of supplementation is critical to fetal outcomes, and may be tied to placental growth effects. In this model, maternal hormone levels were unchanged by supplementation, but placental arginine levels were increased (93). The latter study findings are consistent with other studies using the porcine model – L-arginine supplementation of ~1% diet initiated after GD 15 for 2 weeks or more (studies looked at effects up to 3 months of gestation; full-length gestation = 114 days) is consistently associated with increases in placental weight (~16%), more fetuses and higher fetal weights (94–97). These fetal growth outcomes may be secondary to greater placental vascularization, promoting nutrient transport to the fetus (92,95,97). Wu et al. reported that supplementation with L-arginine or stimulation of arginine production using N-carbamyl glutamate (NCG) resulted in higher plasma NO levels and stimulation of placental eNOS and VEGF production, both critical components of placental vascular growth (95). Placental angiogenin mRNA expression – used as a marker of vascularization – was stimulated by supplementation with 20g/day Progenos, a commercial L-arginine supplement, when administered from GD 15–29 of pregnancy (97). Together, these findings in the porcine model suggest that L-arginine stimulates fetal growth and increases the number of live fetuses born, potentially via activation of NO production and increased placental vascularization in normal pregnancy.

In a murine model, 2% L-arginine increased litter sizes, number of live born pups, and total birthweight when administered throughout pregnancy (starting at GD1) (98). To understand the underlying mechanism, the authors bred wild-type females with homozygous Vegfr2-luc (luciferase-tagged) male mice, to track the transcriptional activity of the VEGF receptor in the fetoplacental unit – used as a marker of angiogenic activity - with supplementation. They found that L-arginine stimulated VEGFR2 transcription and activity corrected for fetoplacental mass, and led to an earlier rise in placental VEGFR2 expression in gestation, proposing that the increases in NO derived from arginine increased VEGF binding to its receptor, activating VEGFR2 transcription (98). These findings are consistent with the increased markers of vascularization found in the porcine studies, and altogether provide evidence for a strong pro-angiogenic effect of arginine supplementation during healthy pregnancy.

The higher number of pups born in L-arginine supplemented pregnancies may be related to the stimulation of key cellular growth pathways in the placenta and uterus, such as STAT3, protein kinase B, and S6K1 activity, which were associated with increases in litter size in an NCG-supplementation rat model (99). Arginine and its metabolites activated these same growth pathways in vitro in trophoblast Jar cell line, and increased cellular adhesion, effects which were abolished by pretreatment with PI3K and mTOR inhibitors (99). This is consistent with a pro-implantation effect of L-arginine supplementation noted by Greene et al. with a 66% increase in implantation sites associated with 2% arginine during pregnancy as compared to isonitrogenous controls (98).

L-arginine as a therapeutic in complicated pregnancies – placenta as target

As reviewed by Weckman et al., L-arginine has positive impacts on fetal growth and birth outcomes in women at risk for growth restriction and preeclampsia (91), however the mechanisms underlying these effects are unclear. A classic pre-clinical model for intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is the low protein diet rat model. Normal dietary protein is 20% for rodents, while 4% dietary protein (LP) has been shown to induce fetal growth restriction by late pregnancy. Bourdon et al. used the LP diet rat model to test the effectiveness of L-arginine or its more bioavailable precursor, L-citrulline, in moderating the effects of a LP diet on fetal growth. The control for this study was an isonitrogenous mixture of nonessential amino acids (100). Both L-citrulline and L-arginine effectively improved fetal growth, though not to levels of the control diet rats, while the isonitrogenous mixture of amino acids had no effect on growth. Placental weight was lower in animals on a LP diet, but was not improved with supplementation. However, placental efficiency was enhanced with both L-arginine and L-citrulline, suggesting some improvement in placental function (100). In a separate study, L-citrulline supplementation (2g/kg/d) of a 4% protein diet, stimulated placental pathways resulting in pro-growth (IGF2), anti-apoptotic (Bcl2/BAX ratio), pro-angiogenic (VEGF, FLT1, FLT1/sFLT), and nutrient transport (SNAT1 and SNAT4) effects on GD15, one week before any effects of supplementation on fetal growth were measurable (101). Together these studies suggest that arginine is capable of mitigating the restrictive fetal growth effects of a low protein diet in pregnancy via impacts on placental signaling pathways involved in growth, vascularization and nutrient transport.

Summary

Despite the strong evidence for positive effects of L-arginine on pregnancy and fetal growth outcomes from human RCTs, the mechanism underlying these effects is poorly understood. Pre-clinical models show that stimulation of endogenous arginine synthesis, or direct supplementation with dietary L-arginine, improves fetal growth in normal and complicated pregnancies, potentially via pro-growth and pro-vascularization effects on the placenta (Figure 4). The reviewed studies did not report outcomes by fetal sex, thus sex-specific effects of L-arginine supplementation remain unknown. More studies are warranted to determine the potential utility of this dietary supplement for improving pregnancy outcomes in women.

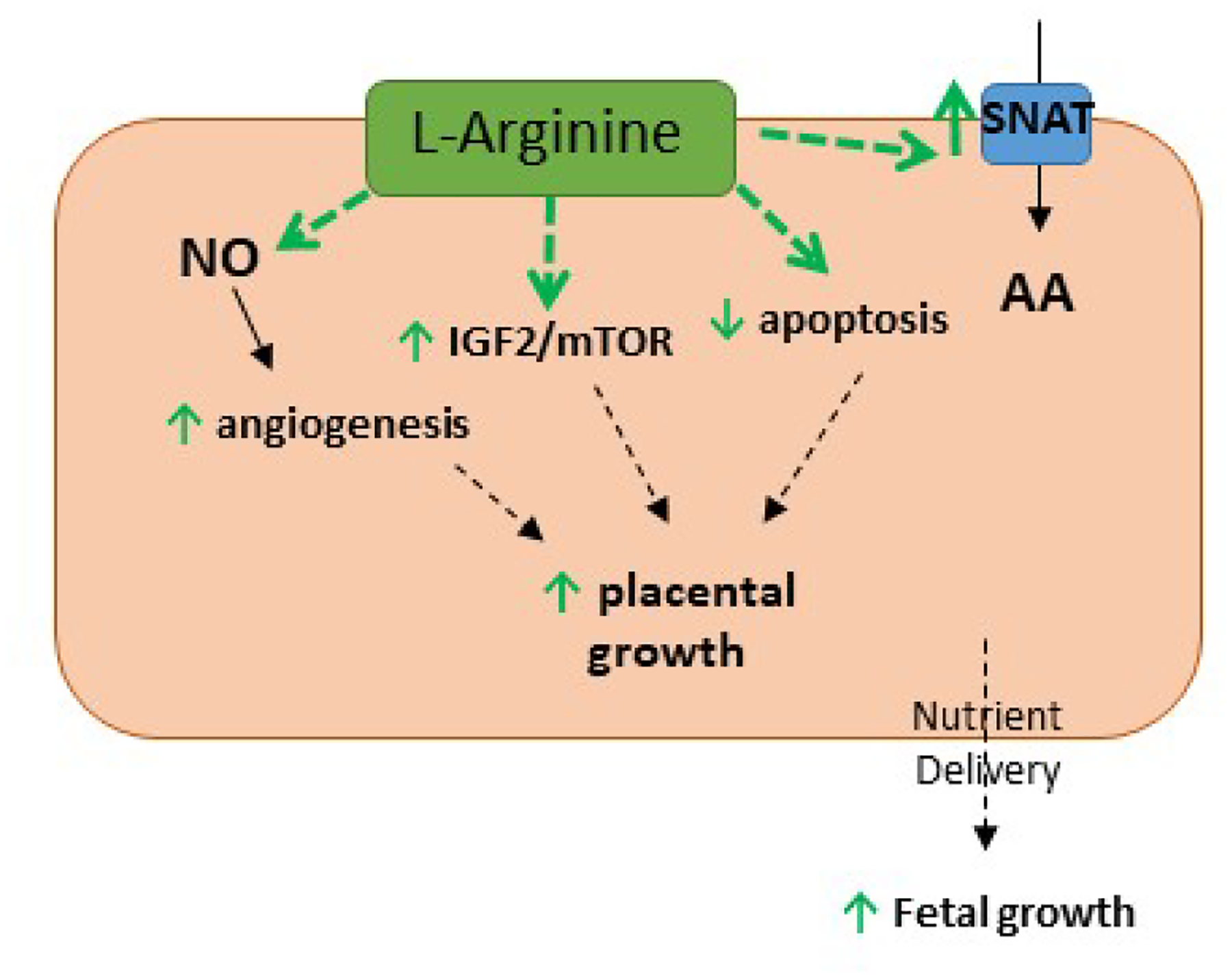

Figure 4.

Placental impacts of L-arginine supplementation. Maternal L-arginine supplementation stimulates placental angiogenic pathways (VEGF, FLT1), growth factors (IGF2, mTOR) and amino acid transporters (e.g. SNAT1, SNAT4), and decreases apoptosis (BCL2/BAX) (green arrows), stimulating placental and fetal growth.

Conclusion

We have reviewed several supplements that have promising therapeutic effects on pregnancy outcomes and fetal growth, which may be mediated by their placental impacts. The sex-specific nature of these effects require further study. Future well-powered RCTs of pregnant women at risk of complications due to either nutritional deficiencies or pre-existing conditions (e.g. obesity, hypertension) are necessary to better understand the full therapeutic potential of these supplements. Dietary supplementation before or during pregnancy may be a safe, relatively affordable and effective way of improving maternal and fetal health.

Acknowledgments

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This work was funded by National Institutes of Health R00HD062841, R01HD091735, and R01HD091054 (POG).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

Dr. O’Tierney-Ginn, Dr. Alvardo-Flores and Dr. Rasool have nothing to disclose. Please see ICMJE forms.

Reference List

- 1.Catalano PM, Shankar K. Obesity and pregnancy: mechanisms of short term and long term adverse consequences for mother and child. BMJ 2017; 356:j1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramakrishnan U, Grant F, Goldenberg T, Zongrone A, Martorell R. Effect of women’s nutrition before and during early pregnancy on maternal and infant outcomes: a systematic review. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology 2012; 26 Suppl 1:285–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jun S, Gahche JJ, Potischman N, Dwyer JT, Guenther PM, Sauder KA, Bailey RL. Dietary Supplement Use and Its Micronutrient Contribution During Pregnancy and Lactation in the United States. Obstetrics and gynecology 2020; 135:623–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmsten K, Flores KF, Chambers CD, Weiss LA, Sundaram R, Buck Louis GM. Most Frequently Reported Prescription Medications and Supplements in Couples Planning Pregnancy: The LIFE Study. Reproductive sciences (Thousand Oaks, Calif) 2018; 25:94–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richard K, Holland O, Landers K, Vanderlelie JJ, Hofstee P, Cuffe JSM, Perkins AV. Review: Effects of maternal micronutrient supplementation on placental function. Placenta 2017; 54:38–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker BC, Hayes DJ, Jones RL. Effects of micronutrients on placental function: evidence from clinical studies to animal models. Reproduction (Cambridge, England) 2018; 156:R69–r82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haggarty P Effect of placental function on fatty acid requirements during pregnancy. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2004; 58:1559–1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanin Aguirre LH, Reza-Lopez S, Levario-Carrillo M. Relation between maternal body composition and birth weight. BiolNeonate 2004; 86:55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leghi GE, Muhlhausler BS. The effect of n-3 LCPUFA supplementation on oxidative stress and inflammation in the placenta and maternal plasma during pregnancy. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 2016; 113:33–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oken E, Kleinman KP, Berland WE, Simon SR, Rich-Edwards JW, Gillman MW. Decline in fish consumption among pregnant women after a national mercury advisory. Obstet Gynecol 2003; 102:346–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith KM, Sahyoun NR. Fish consumption: recommendations versus advisories, can they be reconciled? Nutr Rev 2005; 63:39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olsen S, Sørensen TA, Secher N, Hansen H, Jensen B, Sommer S, Knudsen L. INTAKE OF MARINE FAT, RICH IN (n-3)-POLYUNSATURATED FATTY ACIDS, MAY INCREASE BIRTHWEIGHT BY PROLONGING GESTATION. The Lancet 1986; 328:367–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg JA, Bell SJ, Ausdal WV. Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation During Pregnancy. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2008; 1:162–169 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simopoulos AP, Leaf A, Salem N. Workshop Statement on the Essentiality of and Recommended Dietary Intakes for Omega-6 and Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids (PLEFA) 2000; 63:119–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gázquez A, Hernández-Albaladejo I, Larqué E. Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation during pregnancy as phospholipids did not improve the incorporation of this fatty acid into rat fetal brain compared with the triglyceride form. Nutrition Research 2017; 37:78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gázquez A, Ruíz-Palacios M, Larqué E. DHA supplementation during pregnancy as phospholipids or TAG produces different placental uptake but similar fetal brain accretion in neonatal piglets. Br J Nutr 2017; 118:981–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gil-Sánchez A, Demmelmair H, Parrilla JJ, Koletzko B, Larqué E. Mechanisms Involved in the Selective Transfer of Long Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids to the Fetus. Front Genet 2011; 2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lager S, Ramirez VI, Acosta O, Meireles C, Miller E, Gaccioli F, Rosario FJ, Gelfond JAL, Hakala K, Weintraub ST, Krummel DA, Powell TL. Docosahexaenoic Acid Supplementation in Pregnancy Modulates Placental Cellular Signaling and Nutrient Transport Capacity in Obese Women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017; 102:4557–4567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larqué E, Krauss-Etschmann S, Campoy C, Hartl D, Linde J, Klingler M, Demmelmair H, Caño A, Gil A, Bondy B, Koletzko B. Docosahexaenoic acid supply in pregnancy affects placental expression of fatty acid transport proteins. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 84:853–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calabuig-Navarro V, Haghiac M, Minium J, Glazebrook P, Ranasinghe GC, Hoppel C, Hauguel deMouzon S, Catalano P, O’Tierney-Ginn P. Effect of Maternal Obesity on Placental Lipid Metabolism. Endocrinology 2017; 158:2543–2555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saben J, Lindsey F, Zhong Y, Thakali K, Badger TM, Andres A, Gomez-Acevedo H, Shankar K. Maternal Obesity is Associated with a Lipotoxic Placental Environment. Placenta 2014; 35:171–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirschmugl B, Desoye G, Catalano P, Klymiuk I, Scharnagl H, Payr S, Kitzinger E, Schliefsteiner C, Lang U, Wadsack C, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. Maternal obesity modulates intracellular lipid turnover in the human term placenta. Int J Obes (Lond) 2017; 41:317–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perazzolo S, Hirschmugl B, Wadsack C, Desoye G, Lewis RM, Sengers BG. The influence of placental metabolism on fatty acid transfer to the fetus. Journal of lipid research 2016; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdelhamid AS, Brown TJ, Brainard JS, Biswas P, Thorpe GC, Moore HJ, Deane KH, AlAbdulghafoor FK, Summerbell CD, Worthington HV, Song F, Hooper L. Omega-3 fatty acids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2018; 7:Cd003177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calabuig-Navarro V, Puchowicz M, Glazebrook P, Haghiac M, Minium J, Catalano P, Hauguel deMouzon S, O’Tierney-Ginn P. Effect of ω−3 supplementation on placental lipid metabolism in overweight and obese women. Am J Clin Nutr 2016; 103:1064–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alvarado FL, Calabuig-Navarro V, Haghiac M, Puchowicz M, Tsai P-JS, O’Tierney-Ginn P. Maternal obesity is not associated with placental lipid accumulation in women with high omega-3 fatty acid levels. Placenta 2018; 69:96–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Challier JC, Basu S, Bintein T, Hotmire K, Minium J, Catalano PM, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. Obesity in pregnancy stimulates macrophage accumulation and inflammation in the placenta. Placenta 2008; 29:274–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo WL, Luo Z, Xu X, Zhao S, Li SH, Sho T, Yao J, Zhang J, Xu WN, Xu JX. The Effect of Maternal Diet with Fish Oil on Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Response in Sow and New-Born Piglets. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019; 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones ML, Mark PJ, Mori TA, Keelan JA, Waddell BJ. Maternal dietary omega-3 fatty acid supplementation reduces placental oxidative stress and increases fetal and placental growth in the rat. Biol Reprod 2013; 88:37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng J, Xiong J, Cui C, Huang N, Zhang H, Wu X, Yang Y, Zhou Y, Wei H, Peng J. Maternal Eicosapentaenoic Acid Feeding Decreases Placental Lipid Deposition and Improves the Homeostasis of Oxidative Stress Through a Sirtuin-1 (SIRT1) Independent Manner. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2019; 63:1900343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melody SM, Vincent R, Mori TA, Mas E, Barden AE, Waddell BJ, Keelan JA. Effects of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids on human placental cytokine production. Placenta 2015; 36:34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haghiac M, Yang X-h, Presley L, Smith S, Dettelback S, Minium J, Belury MA, Catalano PM, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. Dietary Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation Reduces Inflammation in Obese Pregnant Women: A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Clinical Trial. PLoS One 2015; 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calder PC. Eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid derived specialised pro-resolving mediators: Concentrations in humans and the effects of age, sex, disease and increased omega-3 fatty acid intake. Biochimie 2020; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arita M, Ohira T, Sun Y-P, Elangovan S, Chiang N, Serhan CN. Resolvin E1 selectively interacts with leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 and ChemR23 to regulate inflammation. J Immunol 2007; 178:3912–3917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bannenberg G, Serhan CN. Specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators in the inflammatory response: An update. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010; 1801:1260–1273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keelan JA, Mas E, D’Vaz N, Dunstan JA, Li S, Barden AE, Mark PJ, Waddell BJ, Prescott SL, Mori TA. Effects of maternal n-3 fatty acid supplementation on placental cytokines, pro-resolving lipid mediators and their precursors. Reproduction 2015; 149:171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Gubory KH, Fowler PA, Garrel C. The roles of cellular reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress and antioxidants in pregnancy outcomes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2010; 42:1634–1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boulis TS, Rochelson B, Novick O, Xue X, Chatterjee PK, Gupta M, Solanki MH, Akerman M, Metz CN. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids enhance cytokine production and oxidative stress in a mouse model of preterm labor. J Perinat Med 2014; 42:693–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stark MJ, Clifton VL, Hodyl NA. Differential effects of docosahexaenoic acid on preterm and term placental pro-oxidant/antioxidant balance. Reproduction 2013; 146:243–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kasture V, Kale A, Randhir K, Sundrani D, Joshi S. Effect of maternal omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin E supplementation on placental apoptotic markers in rat model of early and late onset preeclampsia. Life Sciences 2019; 239:117038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wietrak E, Kamiński K, Leszczyńska-Gorzelak B, Oleszczuk J. Effect of Docosahexaenoic Acid on Apoptosis and Proliferation in the Placenta: Preliminary Report. BioMed Research International 2015; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Klingler M, Blaschitz A, Campoy C, Caño A, Molloy AM, Scott JM, Dohr G, Demmelmair H, Koletzko B, Desoye G. The effect of docosahexaenoic acid and folic acid supplementation on placental apoptosis and proliferation. Br J Nutr 2006; 96:182–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muhlhausler BS, Gibson RA, Yelland LN, Makrides M. Heterogeneity in cord blood DHA concentration: Towards an explanation. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 2014; 91:135–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gould JF, Anderson AJ, Yelland LN, Gibson RA, Makrides M. Maternal characteristics influence response to DHA during pregnancy. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 2016; 108:5–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas B, Ghebremeskel K, Lowy C, Min Y, Crawford MA. Plasma AA and DHA levels are not compromised in newly diagnosed gestational diabetic women. EurJClinNutr 2004; 58:1492–1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wijendran V, Bendel RB, Couch SC, Philipson EH, Cheruku S, Lammi-Keefe CJ. Fetal erythrocyte phospholipid polyunsaturated fatty acids are altered in pregnancy complicated with gestational diabetes mellitus. Lipids 2000; 35:927–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Balachandiran M, Bobby Z, Dorairajan G, Jacob SE, Gladwin V, Vinayagam V, Packirisamy RM. Placental Accumulation of Triacylglycerols in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Its Association with Altered Fetal Growth are Related to the Differential Expressions of Proteins of Lipid Metabolism. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2020; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prieto-Sánchez MT, Ruiz-Palacios M, Blanco-Carnero JE, Pagan A, Hellmuth C, Uhl O, Peissner W, Ruiz-Alcaraz AJ, Parrilla JJ, Koletzko B, Larqué E. Placental MFSD2a transporter is related to decreased DHA in cord blood of women with treated gestational diabetes. Clin Nutr 2017; 36:513–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Min Y, Djahanbakhch O, Hutchinson J, Eram S, Bhullar AS, Namugere I, Ghebremeskel K. Efficacy of docosahexaenoic acid-enriched formula to enhance maternal and fetal blood docosahexaenoic acid levels: Randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled trial of pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Clinical Nutrition 2016; 35:608–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zeisel SH. Nutrition in pregnancy: the argument for including a source of choline. Int J Womens Health 2013; 5:193–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shaw GM, Carmichael SL, Yang W, Selvin S, Schaffer DM. Periconceptional dietary intake of choline and betaine and neural tube defects in offspring. American journal of epidemiology 2004; 160:102–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Resseguie M, Song J, Niculescu MD, da Costa KA, Randall TA, Zeisel SH. Phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PEMT) gene expression is induced by estrogen in human and mouse primary hepatocytes. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2007; 21:2622–2632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wallace TC, Fulgoni VL. Usual Choline Intakes Are Associated with Egg and Protein Food Consumption in the United States. Nutrients 2017; 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yan J, Jiang X, West AA, Perry CA, Malysheva OV, Brenna JT, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Gregory JF 3rd, Caudill MA. Pregnancy alters choline dynamics: results of a randomized trial using stable isotope methodology in pregnant and nonpregnant women. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2013; 98:1459–1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nam J, Greenwald E, Jack-Roberts C, Ajeeb TT, Malysheva OV, Caudill MA, Axen K, Saxena A, Semernina E, Nanobashvili K, Jiang X. Choline prevents fetal overgrowth and normalizes placental fatty acid and glucose metabolism in a mouse model of maternal obesity. J Nutr Biochem 2017; 49:80–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nanobashvili K, Jack-Roberts C, Bretter R, Jones N, Axen K, Saxena A, Blain K, Jiang X. Maternal Choline and Betaine Supplementation Modifies the Placental Response to Hyperglycemia in Mice and Human Trophoblasts. Nutrients 2018; 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.King JH, Kwan STC, Yan J, Jiang X, Fomin VG, Levine SP, Wei E, Roberson MS, Caudill MA. Maternal Choline Supplementation Modulates Placental Markers of Inflammation, Angiogenesis, and Apoptosis in a Mouse Model of Placental Insufficiency. Nutrients 2019; 11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.King JH, Kwan STC, Yan J, Klatt KC, Jiang X, Roberson MS, Caudill MA. Maternal Choline Supplementation Alters Fetal Growth Patterns in a Mouse Model of Placental Insufficiency. Nutrients 2017; 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kwan STC, King JH, Yan J, Jiang X, Wei E, Fomin VG, Roberson MS, Caudill MA. Maternal choline supplementation during murine pregnancy modulates placental markers of inflammation, apoptosis and vascularization in a fetal sex-dependent manner. Placenta 2017; 53:57–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eriksson JG, Kajantie E, Osmond C, Thornburg K, Barker DJ. Boys live dangerously in the womb. AmJHumBiol 2010; 22:330–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, Schisterman EF, Thadhani R, Sachs BP, Epstein FH, Sibai BM, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. The New England journal of medicine 2004; 350:672–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jiang X, Bar HY, Yan J, Jones S, Brannon PM, West AA, Perry CA, Ganti A, Pressman E, Devapatla S, Vermeylen F, Wells MT, Caudill MA. A higher maternal choline intake among third-trimester pregnant women lowers placental and circulating concentrations of the antiangiogenic factor fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFLT1). FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2013; 27:1245–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations WHO. Guidelines for the evaluation of probiotics in food. London, ON: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization. 2002; https://www.who.int/foodsafety/fs_management/en/probiotic_guidelines.pdf. Accessed Sept 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dugoua JJ, Machado M, Zhu X, Chen X, Koren G, Einarson TR. Probiotic safety in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Saccharomyces spp. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2009; 31:542–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.de Goffau MC, Lager S, Sovio U, Gaccioli F, Cook E, Peacock SJ, Parkhill J, Charnock-Jones DS, Smith GCS. Human placenta has no microbiome but can contain potential pathogens. Nature 2019; 572:329–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aagaard K, Ma J, Antony KM, Ganu R, Petrosino J, Versalovic J. The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6:237ra265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Collado MC, Rautava S, Aakko J, Isolauri E, Salminen S. Human gut colonisation may be initiated in utero by distinct microbial communities in the placenta and amniotic fluid. Sci Rep 2016; 6:23129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jiménez E, Marín ML, Martín R, Odriozola JM, Olivares M, Xaus J, Fernández L, Rodríguez JM. Is meconium from healthy newborns actually sterile? Res Microbiol 2008; 159:187–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nordqvist M, Jacobsson B, Brantsæter AL, Myhre R, Nilsson S, Sengpiel V. Timing of probiotic milk consumption during pregnancy and effects on the incidence of preeclampsia and preterm delivery: a prospective observational cohort study in Norway. BMJ Open 2018; 8:e018021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martin JA, Osterman MJK. Describing the Increase in Preterm Births in the United States, 2014–2016. NCHS Data Brief 2018:1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lawn JE, Kinney M. Preterm birth: now the leading cause of child death worldwide. Sci Transl Med 2014; 6:263ed221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yeganegi M, Leung CG, Martins A, Kim SO, Reid G, Challis JR, Bocking AD. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 stimulates colony-stimulating factor 3 (granulocyte) (CSF3) output in placental trophoblast cells in a fetal sex-dependent manner. Biol Reprod 2011; 84:18–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bloise E, Torricelli M, Novembri R, Borges LE, Carrarelli P, Reis FM, Petraglia F. Heat-killed Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG modulates urocortin and cytokine release in primary trophoblast cells. Placenta 2010; 31:867–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yeganegi M, Watson CS, Martins A, Kim SO, Reid G, Challis JR, Bocking AD. Effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 supernatant and fetal sex on lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine and prostaglandin-regulating enzymes in human placental trophoblast cells: implications for treatment of bacterial vaginosis and prevention of preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009; 200:532.e531–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Koscik RJE, Reid G, Kim SO, Li W, Challis JRG, Bocking AD. Effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 Supernatant on Cytokine and Chemokine Output From Human Amnion Cells Treated With Lipoteichoic Acid and Lipopolysaccharide. Reprod Sci 2018; 25:239–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Burdet J, Sacerdoti F, Cella M, Franchi AM, Ibarra C. Role of TNF-α in the mechanisms responsible for preterm delivery induced by Stx2 in rats. Br J Pharmacol 2013; 168:946–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, Kuivaniemi H, Tromp G. Bacterial vaginosis, the inflammatory response and the risk of preterm birth: a role for genetic epidemiology in the prevention of preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 190:1509–1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dudley DJ. Pre-term labor: an intra-uterine inflammatory response syndrome? J Reprod Immunol 1997; 36:93–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chirico G, Ciardelli L, Cecchi P, De Amici M, Gasparoni A, Rondini G. Serum concentration of granulocyte colony stimulating factor in term and preterm infants. Eur J Pediatr 1997; 156:269–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mold JE, Michaëlsson J, Burt TD, Muench MO, Beckerman KP, Busch MP, Lee TH, Nixon DF, McCune JM. Maternal alloantigens promote the development of tolerogenic fetal regulatory T cells in utero. Science 2008; 322:1562–1565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zeitlin J, Saurel-Cubizolles M-J, de Mouzon J, Rivera L, Ancel P-Y, Blondel B, Kaminski M. Fetal sex and preterm birth: are males at greater risk? Human Reproduction 2002; 17:2762–2768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Blümer N, Sel S, Virna S, Patrascan CC, Zimmermann S, Herz U, Renz H, Garn H. Perinatal maternal application of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG suppresses allergic airway inflammation in mouse offspring. Clin Exp Allergy 2007; 37:348–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hessle C, Hanson LA, Wold AE. Lactobacilli from human gastrointestinal mucosa are strong stimulators of IL-12 production. Clin Exp Immunol 1999; 116:276–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Viljanen M, Pohjavuori E, Haahtela T, Korpela R, Kuitunen M, Sarnesto A, Vaarala O, Savilahti E. Induction of inflammation as a possible mechanism of probiotic effect in atopic eczema-dermatitis syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005; 115:1254–1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.von der Weid T, Bulliard C, Schiffrin EJ. Induction by a lactic acid bacterium of a population of CD4(+) T cells with low proliferative capacity that produce transforming growth factor beta and interleukin-10. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2001; 8:695–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rautava S, Collado MC, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Probiotics modulate host-microbe interaction in the placenta and fetal gut: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neonatology 2012; 102:178–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fulde M, Sommer F, Chassaing B, van Vorst K, Dupont A, Hensel M, Basic M, Klopfleisch R, Rosenstiel P, Bleich A, Bäckhed F, Gewirtz AT, Hornef MW. Neonatal selection by Toll-like receptor 5 influences long-term gut microbiota composition. Nature 2018; 560:489–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vijay-Kumar M, Aitken JD, Carvalho FA, Cullender TC, Mwangi S, Srinivasan S, Sitaraman SV, Knight R, Ley RE, Gewirtz AT. Metabolic syndrome and altered gut microbiota in mice lacking Toll-like receptor 5. Science 2010; 328:228–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kaplas N, Isolauri E, Lampi AM, Ojala T, Laitinen K. Dietary counseling and probiotic supplementation during pregnancy modify placental phospholipid fatty acids. Lipids 2007; 42:865–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gu XL, Li H, Song ZH, Ding YN, He X, Fan ZY. Effects of isomaltooligosaccharide and Bacillus supplementation on sow performance, serum metabolites, and serum and placental oxidative status. Anim Reprod Sci 2019; 207:52–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Weckman AM, McDonald CR, Baxter JB, Fawzi WW, Conroy AL, Kain KC. Perspective: L-arginine and L-citrulline Supplementation in Pregnancy: A Potential Strategy to Improve Birth Outcomes in Low-Resource Settings. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md) 2019; 10:765–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li X, Bazer FW, Johnson GA, Burghardt RC, Erikson DW, Frank JW, Spencer TE, Shinzato I, Wu G. Dietary supplementation with 0.8% L-arginine between days 0 and 25 of gestation reduces litter size in gilts. The Journal of nutrition 2010; 140:1111–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li X, Bazer FW, Johnson GA, Burghardt RC, Frank JW, Dai Z, Wang J, Wu Z, Shinzato I, Wu G. Dietary supplementation with L-arginine between days 14 and 25 of gestation enhances embryonic development and survival in gilts. Amino acids 2014; 46:375–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gao K, Jiang Z, Lin Y, Zheng C, Zhou G, Chen F, Yang L, Wu G. Dietary L-arginine supplementation enhances placental growth and reproductive performance in sows. Amino acids 2012; 42:2207–2214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wu X, Yin YL, Liu YQ, Liu XD, Liu ZQ, Li TJ, Huang RL, Ruan Z, Deng ZY. Effect of dietary arginine and N-carbamoylglutamate supplementation on reproduction and gene expression of eNOS, VEGFA and PlGF1 in placenta in late pregnancy of sows. Animal reproduction science 2012; 132:187–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Garbossa CA, Carvalho Júnior FM, Silveira H, Faria PB, Schinckel AP, Abreu ML, Cantarelli VS. Effects of ractopamine and arginine dietary supplementation for sows on growth performance and carcass quality of their progenies. Journal of animal science 2015; 93:2872–2884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Novak S, Paradis F, Patterson JL, Pasternak JA, Oxtoby K, Moore HS, Hahn M, Dyck MK, Dixon WT, Foxcroft GR. Temporal candidate gene expression in the sow placenta and embryo during early gestation and effect of maternal Progenos supplementation on embryonic and placental development. Reproduction, fertility, and development 2012; 24:550–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Greene JM, Dunaway CW, Bowers SD, Rude BJ, Feugang JM, Ryan PL. Dietary L-arginine supplementation during gestation in mice enhances reproductive performance and Vegfr2 transcription activity in the fetoplacental unit. The Journal of nutrition 2012; 142:456–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zeng X, Huang Z, Mao X, Wang J, Wu G, Qiao S. N-carbamylglutamate enhances pregnancy outcome in rats through activation of the PI3K/PKB/mTOR signaling pathway. PloS one 2012; 7:e41192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bourdon A, Parnet P, Nowak C, Tran NT, Winer N, Darmaun D. L-Citrulline Supplementation Enhances Fetal Growth and Protein Synthesis in Rats with Intrauterine Growth Restriction. The Journal of nutrition 2016; 146:532–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tran NT, Amarger V, Bourdon A, Misbert E, Grit I, Winer N, Darmaun D. Maternal citrulline supplementation enhances placental function and fetal growth in a rat model of IUGR: involvement of insulin-like growth factor 2 and angiogenic factors. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet 2017; 30:1906–1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yimam M, Lee YC, Hyun EJ, Jia Q. Reproductive and Developmental Toxicity of Orally Administered Botanical Composition, UP446-Part I: Effects on Embryo-Fetal Development in New Zealand White Rabbits and Sprague Dawley Rats. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol 2015; 104:141–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Prater MR, Zimmerman KL, Pinn LC, Keay JM, Laudermilch CL, Holladay SD. Role of maternal dietary antioxidant supplementation in murine placental and fetal limb development. Placenta 2006; 27:502–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nakano S, Noguchi T, Takekoshi H, Suzuki G, Nakano M. Maternal-fetal distribution and transfer of dioxins in pregnant women in Japan, and attempts to reduce maternal transfer with Chlorella (Chlorella pyrenoidosa) supplements. Chemosphere 2005; 61:1244–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mathew SA, Bhonde RR. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids promote angiogenesis in placenta derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Pharmacol Res 2018; 132:90–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Smit MN, Spencer JD, Patterson JL, Dyck MK, Dixon WT, Foxcroft GR. Effects of dietary enrichment with a marine oil-based n-3 LCPUFA supplement in sows with predicted birth weight phenotypes on birth litter quality and growth performance to weaning. Animal 2015; 9:471–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Griffiths JC, Borzelleca JF, St Cyr J. Lack of oral embryotoxicity/teratogenicity with D-ribose in Wistar rats. Food Chem Toxicol 2007; 45:388–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Peng J, Zhou Y, Hong Z, Wu Y, Cai A, Xia M, Deng Z, Yang Y, Song T, Xiong J, Wei H. Maternal eicosapentaenoic acid feeding promotes placental angiogenesis through a Sirtuin-1 independent inflammatory pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2019; 1864:147–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lin Y, Han XF, Fang ZF, Che LQ, Nelson J, Yan TH, Wu D. Beneficial effects of dietary fibre supplementation of a high-fat diet on fetal development in rats. Br J Nutr 2011; 106:510–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lin Y, Han XF, Fang ZF, Che LQ, Wu D, Wu XQ, Wu CM. The beneficial effect of fiber supplementation in high- or low-fat diets on fetal development and antioxidant defense capacity in the rat. Eur J Nutr 2012; 51:19–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wang CX, Chen F, Zhang WF, Zhang SH, Shi K, Song HQ, Wang YJ, Kim SW, Guan WT. Leucine Promotes the Growth of Fetal Pigs by Increasing Protein Synthesis through the mTOR Signaling Pathway in Longissimus Dorsi Muscle at Late Gestation. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2018; 66:3840–3849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cruz BL, da Silva PC, Tomasin R, Oliveira AG, Viana LR, Salomao EM, Gomes-Marcondes MC. Dietary leucine supplementation minimises tumour-induced damage in placental tissues of pregnant, tumour-bearing rats. BMC cancer 2016; 16:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]