To the Editor:

The emergency department (ED) has been considered a venue of high-yield HIV screening for over 30 years.1,2 Current strategies of ED-based HIV testing include targeted screening (screening based on identification of risk factors) and non-targeted screening (screening regardless of risk).3,4 Non-targeted screening has been shown to be feasible in several studies but with relatively high costs of implementation and staffing needs.3,5–7 Further, it is important to recognize that the staffing model, training, and process selected for offering testing can influence test uptake. Targeted screening, based on traditional HIV risk factors, focuses limited testing resources on patients considered at highest risk; however, this strategy may not diagnose some patients with HIV.8

We sought to determine the proportion of ED patients who did not undergo HIV testing with either a targeted or non-targeted screening strategy, due to drop-off at each step of the following screening cascade: (1) not eligible for testing; (2) not offered testing based on responses to a risk-questionnaire; (3) offered but opted-out from testing; (4) agreeable to testing but testing not completed. We conducted a cross-sectional, identity-unlinked HIV seroprevalence study nested within a clinical trial comparing targeted and non-targeted ED-based HIV screening strategies (see Digital Appendix for detailed description of study methods). The HIV Testing using Enhanced Screening Techniques in EDs (HIV TESTED) trial was a multi-center, pragmatic randomized trial of different opt-out HIV screening strategies (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01781949). Inclusion criteria were adults (≥18 years of age) presenting to the ED without known HIV and capable of consenting for medical care.9 ED patients were excluded if: critically ill; altered consciousness; a victim of sexual assault or occupational exposure. Eligible patients presenting to the ED were randomized at triage to one of three arms: (1) non-targeted HIV screening, wherein all patients were offered an HIV test; (2) targeted HIV screening based on conventional risk characteristics as defined by the CDC (injection drug use, high risk sexual activity, diagnosis of HIV-associated infections, and a history of immunosuppression); or (3) enhanced targeted HIV screening based on the Denver HIV Risk Score, a validated quantitative HIV risk prediction instrument employing age, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual history, injection drug use, and HIV testing history.10 Using a standardized script, an ED triage nurse offered HIV testing to all participants who were randomized to non-targeted screening and administered either HIV risk assessment to those randomized to targeted screening. During the course of the trial (December 10, 2015, through January 21, 2016) at the Johns Hopkins ED, we conducted an identity-unlinked HIV seroprevalence study using methods previously described.11,12 This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Hospital Institutional Review Board.

During the 6-week study period, 6,593 unique patients accounted for 7,931 ED visits. Sufficient remnant blood was available for 4,015 (60.9%) unique patients. Of these, 1,092 (27.2%) were ineligible to be randomized to an HIV testing strategy in the HIV TESTED trial, most commonly for reasons of altered mental status or critical illness. The remaining 2,923 (72.8%) patients were included and randomized to one of the three testing strategies.

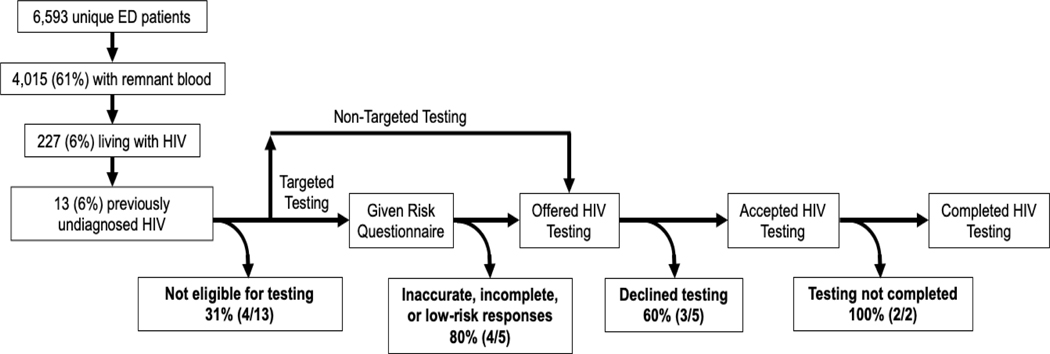

Among the 4,015 patients with sufficient quantities of remnant blood, 227 (5.7%, 95% CI: 5.0%, 6.4%) were living with HIV, and 13 (0.3%, 95% CI: 0.2%, 0.6%) were previously undiagnosed (i.e., 5.7% [95% CI: 3.1%, 9.6%] among 227 patients infected with HIV). Among these 13 patients, four were excluded from TESTED trial due to ineligibility, four were randomized to the non-targeted screening arm, and five were randomized to targeted arms (four to the conventional targeted arm and one to the enhanced targeted arm). Eleven of the 13 patients were not offered or were not agreeable to HIV screening. Reasons for not being screened were: four were ineligible for inclusion; three out of four opted out of screened after being randomized to the non-targeted screening strategy; four out of five provided non-responses or were determined to be low-risk after being randomized to the targeted screening strategy. Of the four patients randomized to the non-targeted screening, only one did not opt out of HIV testing offered by the triage nurses, but ultimately did not complete screening. Of the five patients randomized to the targeted screening strategies, four underwent risk assessment using conventional risk behaviors: two did not respond to the questions and two were classified to be low-risk by their responses to the questionnaire. The remaining patient who was randomized to the enhanced targeted screening was identified as being at increased risk after completing the risk assessment and agreed to HIV testing, but ultimately did not complete testing. We were not able to determine the reasons HIV testing was not completed for the two patients who were agreeable to testing because of the identity-unlinked nature of this study.

These findings allow us to create a process map of HIV screening. On the path to diagnosis, patients with previously undiagnosed HIV must first be offered HIV testing, then must accept (or not opt out of) HIV testing, and finally must complete HIV testing. Similar to the ‘HIV Care Cascade,’13 we summarized data from this study to characterize the HIV screening cascade (Figure) in ED patients. A previous identity-unlinked seroprevalence study from our ED during a period of universal, non-targeted HIV screening found the prevalence of undiagnosed HIV to be 1.0% among those offered testing versus 3.0% among those not offered testing (p < 0.001).14 Drop-off in the cascade also occurred among those who were offered but opted out of testing: four of the 13 patients with previously undiagnosed HIV under a non-targeted strategy and one of five under a targeted strategy were offered testing, but only two (40%) accepted testing. In our prior study with non-targeted HIV screening, we found an overall prevalence of previously undiagnosed HIV of 2.3%: 1.3% among those who declined testing and 0.4% among those who accepted testing (p = 0.08).14 Compared to that study conducted in 2007, our current study demonstrates a much lower overall prevalence of undiagnosed HIV (0.3%), but a similar drop-off along the screening cascade due to patient declining screening. The overall opt-out frequency among patients randomized to the non-targeted strategy 58%, which is consistent with two prior studies of non-targeted ED-based HIV screening programs.15,16

Figure:

HIV Screening Cascade as determined by an identity-unlinked HIV seroprevalence study nested within a pragmatic randomized clinical trial of Emergency Department-based HIV screening strategies (HIV TESTED), Baltimore 2015 – 2016

Among the five patients with previously undiagnosed HIV who were randomized to targeted screening, none were ultimately diagnosed. Although these numbers are small, this suggests that targeted screening using conventional HIV risk factors may not be optimal in a real-world setting. The overall frequency of non-response among those randomized to the targeted testing strategies was 37.8%. Given the sensitive nature of the risk questions, and the persistence of behavioral stigmatization, it is possible that respondents were deterred from answering accurately or even completing the questionnaire.17 While the conventional risk assessment is entirely comprised of potentially sensitive questions, the Denver HIV Risk Score includes non-behavioral risk characteristics as well, which may improve its fidelity in clinical practice. Our findings illustrate that the success of targeted screening partially depends on accurate completion of the risk assessment.

Two patients (one randomized to targeted screening and the other to non-targeted screening) were agreeable but did not complete screening. The overall frequency of test completion among participants who were agreeable to testing at our site during this clinical trial was 81%. Due to the nature of identity-unlinked methodology, we were not able to review the reasons of testing not completed for these two patients. One possible reason is that the treating ED physician did not complete the test order or cancelled the test order. It is also possible that blood was not drawn for HIV testing (which required a separate blood tube). Finally, it is possible that patient care needs or patient flow in the ED prevented testing from being completing after the patients expressed consent to testing. In many EDs, varied workflow issues add to existing structural barriers that hinder implementation of HIV screening programs, including constraints in staffing, resource support for linkage-to-care for rapid ART start. Addressing these issues may eliminate drop-off at this final step of the cascade and increase HIV testing yield among our patient population.

Important limitations of this study design should be noted. As with any seroprevalence study, we necessarily excluded ED patients without sufficient remnant blood to conduct HIV testing. Because of the identity-unlinked nature of the study, we could not identify specific reasons for subject exclusion from the HIV TESTED trial. Finally, it is possible that our operational definition of new diagnosis of HIV may have misclassified individuals who had previously been diagnosed elsewhere with HIV but did not disclose HIV as part of their past medical history.

In conclusion, among ED patients with previously undiagnosed HIV who were eligible for an identity-unlinked HIV seroprevalence study, none completed HIV screening. We used these data to introduce the “HIV Screening Cascade”, a conceptual framework of the path to HIV diagnosis. This framework highlights varied methods by which ED-based HIV screening programs can be optimized to reduce drop-off at each step of the cascade: (1) broadly include criteria for testing eligibility; (2) improve completion and accuracy of responses to risk questionnaires, perhaps by eliminating stigmatizing behavioral questions; and (3) address workflow issues that hinder completion of testing among those who agree to be tested.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Presented in part: 2018 Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Annual Meeting, Indianapolis, Indiana, May 15-18, 2018.

Funding: This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at National Institutes of Health; The Baltimore City Department; the Gilead Foundation HIV Focus Program; and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at National Institutes of Health [T32AI007433 to AMM; K01AI100681 to Y-HH; R01AI106057 to JSH]. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Kelen GD, Fritz S, Qaqish B, et al. Unrecognized human immunodeficiency virus infection in emergency department patients. N Engl J Med 1988;318(25):1645–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelen GD, Chanmugam A, Meyer WA, Farzadegan H, Stone D, Quinn TC. Detection of HIV-1 by polymerase chain reaction and culture in seronegative intravenous drug users in an inner-city emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 1993;22(5):769–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haukoos JS, White DAE, Lyons MS, et al. Operational methods of HIV testing in emergency departments: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med 2011;58(1 Suppl 1):S96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothman RE, Lyons MS, Haukoos JS. Uncovering HIV infection in the emergency department: a broader perspective. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med 2007;14(7):653–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.d’Almeida KW, Kierzek G, de Truchis P, et al. Modest Public Health Impact of Nontargeted Human Immunodeficiency Virus Screening in 29 Emergency Departments. Arch Intern Med 2012;172(1):12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holtgrave DR. Costs and consequences of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendations for opt-out HIV testing. PLoS Med 2007;4(6):e194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haukoos JS. The Impact of Nontargeted HIV Screening in Emergency Departments and the Ongoing Need for Targeted Strategies: Comment on “Modest Public Health Impact of Nontargeted Human Immunodeficiency Virus Screening in 29 Emergency Departments.” Arch Intern Med 2012;172(1):20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenkins TC, Gardner EM, Thrun MW, Cohn DL, Burman WJ. Risk-Based Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Testing Fails to Detect the Majority of HIV-Infected Persons in Medical Care Settings: Sex Transm Dis 2006;33(5):329–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haukoos J, Lyons M, White D, Hopkins E, Schmidt M, Pfeil S, Ruffner A, Signer D, Todorovic T, Toerper M, Ancona R, Al-Tayyib A, Rowan S, Hsieh YH, Sabel A, Rothman R. A Multi-Center Pragmatic Randomized Comparison of HIV Screening Strategy Effectiveness in the Emergency Department: The HIV TESTED Trial. Acad Emerg Med 2017;24:S7–281.28478651 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haukoos JS, Lyons MS, Lindsell CJ, et al. Derivation and validation of the Denver Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) risk score for targeted HIV screening. Am J Epidemiol 2012;175(8):838–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelen GD, Hsieh Y-H, Rothman RE, et al. Improvements in the continuum of HIV care in an inner-city emergency department: AIDS 2016;30(1):113–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsieh Y-H, Patel AV, Loevinsohn GS, Thomas DL, Rothman RE. Emergency departments at the crossroads of intersecting epidemics (HIV, HCV, injection drug use and opioid overdose)-Estimating HCV incidence in an urban emergency department population. J Viral Hepat 2018;25(11):1397–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, del Rio C, Burman WJ. The Spectrum of Engagement in HIV Care and its Relevance to Test-and-Treat Strategies for Prevention of HIV Infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52(6):793–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsieh Y-H, Kelen GD, Beck KJ, et al. Evaluation of hidden HIV infections in an urban ED with a rapid HIV screening program. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34(2):180–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felsen UR, Torian LV, Futterman DC, et al. An expanded HIV screening strategy in the Emergency Department fails to identify most patients with undiagnosed infection: insights from a blinded serosurvey. AIDS Care 2020;32(2):202–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czarnogorski M, Brown J, Lee V, et al. The Prevalence of Undiagnosed HIV Infection in Those Who Decline HIV Screening in an Urban Emergency Department. AIDS Res Treat 2011;2011:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pringle K, Merchant RC, Clark MA. Is Self-Perceived HIV Risk Congruent with Reported HIV Risk Among Traditionally Lower HIV Risk and Prevalence Adult Emergency Department Patients? Implications for HIV Testing. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2013;27(10):573–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.