Abstract

Background:

Little is known about the timing of preclinical heart failure (HF) development, particularly among blacks. The primary aims of this study were to delineate age-related left ventricular (LV) structure and function evolution in a biracial cohort and to test the hypothesis that young-adult LV parameters within normative ranges would be associated with incident stage B-defining LV abnormalities over 25 years, independent of cumulative risk factor burden.

Methods:

We analyzed data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Participants (N=2,833) were 45% black, 56% female, with mean baseline age 30.1 years. We used generalized estimating equation logistic regression to estimate age-related probabilities of stage B LV abnormalities (remodeling, hypertrophy, or dysfunction) and logistic regression to examine risk-factor-adjusted associations between baseline LV parameters and incident abnormalities. We used Cox regression to assess whether baseline LV parameters associated with incident stage B LV abnormalities were also associated with incident clinical (stage C/D) HF events over >25 years’ follow-up.

Results:

Probabilities of stage B LV abnormalities at ages 25 and 60 years were 10.5% (95% CI, 9.4–11.8%) and 45.0% (42.0–48.1%), with significant race-sex disparities; e.g., at age 60: black men 52.7% (44.9–60.3%), black women 59.4% (53.6–65.0%), white men 39.1% (33.4–45.0%), and white women 39.1% (33.9–44.6%). Over 25 years, baseline LV end-systolic dimension/height was associated with incident systolic dysfunction (adjusted odds ratio per 1-SD higher: 2.56 [1.87–3.52]), eccentric hypertrophy (1.34 [1.02–1.75]), concentric hypertrophy (0.69 [0.51–0.91]), and concentric remodeling (0.68 [0.58–0.79]); baseline LV mass/height2.7 was associated with incident eccentric hypertrophy (1.70 [1.25–2.32]), concentric hypertrophy (1.63 [1.19–2.24]), and diastolic dysfunction (1.24 [1.01–1.52]). Among the entire cohort with baseline echocardiographic data available (N=4097; 72 HF events), LV end-systolic dimension/height and mass/height2.7 were significantly associated with incident clinical HF (adjusted hazard ratios per 1-SD higher: 1.56 [95% CI, 1.26–1.93] and 1.42 [1.14–1.75], respectively).

Conclusions:

Stage B LV abnormalities and related racial disparities were present in young adulthood, increased with age, and were associated with baseline variation in indexed LV end-systolic dimension and mass. Baseline indexed LV end-systolic dimension and mass were also associated with incident clinical HF. Efforts to prevent the LV abnormalities underlying clinical HF should start from a young age.

Keywords: left ventricle, disparities, heart failure

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) is a condition of aging,1,2 with lifetime risks of at least 1 in 5 at age 45 years in US cohorts, even without antecedent myocardial infarction (MI).3,4 Once HF is diagnosed, mortality is high, at around 50% over 5 years.5–7 Although HF-related cardiovascular (CV) disease mortality in the US declined from 1999 to 2011, it subsequently increased through 2017, and black-white disparities concurrently widened, particularly among younger adults.8

The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) approach to HF emphasizes the potential for early intervention by including early asymptomatic periods in the progressive stages of HF development.1 Stage A indicates clinical risk factors (e.g., hypertension), stage B indicates asymptomatic left ventricular (LV) remodeling or dysfunction, and stages C and D indicate symptomatic HF. Given the high mortality of symptomatic HF, prevention of progression from stage A to B and C are key targets.1,7 However, the timing with which stage B-defining LV abnormalities and related black-white disparities develop is not well-studied. Prior reports in this area have focused on midlife or later, or were limited by racial homogeneity, cross-sectional design, or restricted focus on one or a few LV parameters. To better understand the natural history of early HF development and identify potential preventive strategies, longitudinal data are needed with tracking of multiple subclinical LV phenotypes through young adulthood and quantification of the relative importance of these antecedents of HF and related disparities.

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) has phenotyped the aging process, including repeated echocardiograms, among a biracial community-based cohort. We utilized 25 years of CARDIA data to: (1) examine normative evolution of LV structure and function and related race-sex differences from young adulthood (baseline ages 22–38 years) through middle age, (2) test and quantify associations between variations in young-adult LV parameters and incident adverse geometry or dysfunction (stage B-defining abnormalities) in middle age, adjusted for cumulative CV risk factor burden, and (3) assess whether young-adult LV parameters associated with incident stage B-defining LV abnormalities were also associated with incident clinical (stage C/D) HF events.

METHODS

Additional details are available in the Online Appendix.

Study Design and Participants

CARDIA9 is a population-based, longitudinal cohort study that began in 1985–86 with enrollment of 5,115 healthy young black and white adults from Birmingham, Alabama; Chicago, Illinois; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Oakland, California. Follow-up examinations occurred 2, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 years later, including echocardiography in 1990–91 (CARDIA Year 5; hereafter referred to as baseline), 2010–11, and 2015–16 (CARDIA Year 30; hereafter referred to as 25-year follow-up from baseline). Retention rates among surviving participants at each in-person examination were 91%, 86%, 81%, 79%, 74%, 72%, 72%, and 71%, respectively. Contact is maintained with participants every 6 months, with annual interim medical history ascertainment; over the last 2 years, >90% of the surviving cohort members have been directly contacted. The study was approved by institutional review boards at all sites, and participants gave informed consent.

For our main analyses, we included participants who completed echocardiograms both at baseline and 25 years later (N=2,878), excluding examinations during pregnancy (N=45); we also used data from echocardiograms 20 years after baseline, but these were not required for inclusion. Data from these 2,833 participants were analyzed to determine age-related patterns of cardiac change and stage B LV abnormalities development. To examine associations between baseline LV parameters and incident stage B LV abnormalities, we excluded participants with certain intervening conditions and events (e.g., significant valve dysfunction or MI; eFigure 1), given the focus on age-related, progressive cardiac remodeling and dysfunction, rather than more rapid (and clinically suspected) LV changes in response to an inciting event or intervention. After exclusions (N=130), 2,703 participants comprised the analytic sample for the association analyses. All available data were used; participants were excluded from particular analyses if relevant variables were missing.

For the secondary analysis of incident clinical HF events, we included all participants with baseline echocardiographic and covariate data available (N=4,097).

Echocardiographic Measures and Classification

Echocardiographic protocols were consistent with contemporaneous guidelines10–13 and are publicly available.14 For analyses of age-related patterns of cardiac change, chocardiographic variables measured at baseline, 20 years later, and 25 years later were utilized (eTable 1). For analyses of associations with incident stage-B defining LV abnormalities, predictors were echocardiographic measures at baseline (1990–91; ages 22–38 years) and outcomes were echocardiographic measures 25 years later (2015–16; ages 47–63 years). For analyses of associations with incident clinical HF, predictors were echocardiographic measures at baseline.

We used American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) criteria12 to classify LV geometry into four categories: concentric remodeling (no hypertrophy), concentric hypertrophy, eccentric hypertrophy, or normal (eFigure 2). Systolic dysfunction was defined as ejection fraction (EF) <50% 7,15. Diastolic dysfunction was defined per ASE 2016 guidelines13 (eTable 1); given limitations in available technology at baseline in 1990–91, this assessment was not available until the 2010–11 examination (participant ages ≥40 years). Stage B LV abnormalities were defined as any of the following: abnormal geometry (i.e., concentric remodeling, concentric hypertrophy, or eccentric hypertrophy), systolic dysfunction, or diastolic dysfunction.

Clinical (Stage C/D) Heart Failure

Clinical CV events were reported by participants during annual telephone interviews (with specific inquiry regarding hospitalizations), and deaths were identified on an ongoing basis from family contacts and queries of the National Death Index. Reported events were validated and adjudicated as HF (including fatal or nonfatal HF) by two members of the CARDIA endpoints committee through medical record review using standard definitions.16 For the current analysis, adjudication of HF events was complete through 2017–18, 27 years after baseline.

Covariates

Standard adjustment covariates included baseline age, sex, race, educational level (years), and heart rate. Risk factor covariates included standardized measurements of body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure (average of second and third), total to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio, and fasting blood glucose; as well as self-reported physical activity,17 alcohol use (ml/day), smoking (cigarettes/day), and antihypertensive and antihyperlipidemic medication use (yes/no). The cumulative intervening burden of each risk factor was calculated using all available measurements from baseline to 20 years later (required ≥3 measurements: baseline, 20 years later, and ≥1 in between). For continuous factors, the measurement at each examination was multiplied by the number of years until the next available measurement, and these were summed to yield the 20-year cumulative exposure, expressed as units*years (e.g., mm Hg*years). For categorical factors (medication use), cumulative exposure was defined by the proportion of study examinations exposed.

Statistical Analysis

Normative LV Structure-Function Evolution and Related Disparities

To describe the natural history of LV structure and function from early- to mid-adulthood by age (rather than by CARDIA examination year, which does not adequately represent age), unadjusted echocardiographic parameter means and prevalence of stage B LV abnormalities were plotted by 5-year categories of age at measurement, overall and for each race-sex group; in plots of categorical abnormalities, ages 55–64 years were grouped together due to smaller subgroup sample sizes at age 60–64 years. We incorporated all available echocardiograms (2 or 3) for each participant to demonstrate longitudinal patterns of change. For each continuous echocardiographic parameter, a random coefficients mixed model consisting of fixed-effect terms for race-sex group, linear and quadratic terms for exam age, and an interaction between race-sex group and linear exam age was assessed using the SAS procedure MIXED. An additional interaction between race-sex group and age-squared was tested but dropped due to non-significance. For each categorical LV outcome, a generalized estimating equation logistic regression on these same terms was assessed, and predicted probabilities (with 95% confidence intervals [CI]) are reported. Primary analyses utilized M-mode data for consistency across examinations; in a sensitivity analysis, we used two-dimensional data for LV size (i.e., end-diastolic and end-systolic volume/height) and EF.

Associations of Early-Adult LV Structure-Function with Incident Stage B LV Abnormalities

To examine associations of early-adult LV parameters with incident stage B abnormalities, we used covariate-adjusted logistic regression of categorical LV outcomes at 25-year follow-up on baseline echocardiographic parameters, excluding participants who had the outcome of interest at baseline. For diastolic dysfunction, e’ and tricuspid regurgitation velocity were unavailable at baseline (in 1990–91), so participants were excluded if they had left atrial dilation or E/A outside of age-specific norms;18 participants were also excluded if they had EF <50%, since diastolic function assessment is primarily relevant to individuals with normal EFs.13 Covariate adjustment was performed in two steps. Model 1 adjusted for demographics and heart rate at 25-year follow-up. Model 2 additionally adjusted for cumulative risk factor burden from baseline to 20 years later. Models were first evaluated with single baseline echocardiographic predictors and dichotomous outcomes. Subsequent models incorporated multiple baseline predictors with polytomous geometry outcomes and dichotomous function outcomes. Sets of collinear predictors (on the basis of variance inflation factors and/or clinical judgment; e.g., LV mass with wall thicknesses) were examined in separate models. Final multivariable models were selected considering the strength and consistency of associations (e.g., Wald chi-square), collinearity, and clinical interpretability. In the final models, an interaction term for race-sex group was tested and qualitative differences were explored via race-sex stratification. A quadratic term for each echocardiographic predictor was also tested in the final models; these did not add meaningfully to the results and are not presented. In a sensitivity analysis, we excluded outliers, defined by any baseline echocardiographic parameter >3 SD from the sex-specific mean.

We also examined continuous associations between echocardiographic parameters in early and middle adulthood using covariate-adjusted linear regression. These analyses were similar to those for categorical outcomes, except participants with prevalent abnormalities were not excluded.

Associations of Early-Adult LV Structure-Function with Incident Clinical (Stage C/D) HF

To assess whether selected baseline LV parameters found to be associated with incident stage B-defining LV abnormalities were also associated with incident clinical HF events, we used Cox proportional hazards regression, after confirming appropriateness of proportional hazards assumptions. We estimated hazards ratios (HR) for associations between baseline LV parameters and incident fatal or nonfatal clinical HF in multiple models, including single or multiple echocardiographic predictors, and with adjustment for baseline age, sex, educational level, and heart rate (Model 1), or these standard covariates plus baseline risk factor covariates (Model 2; see Covariates, above). Participants who died from something other than HF were censored at the time of death.

Bias Assessment

To address potential selection bias, we compared covariates for CARDIA participants included in our main analytic sample versus those not included due to lack of required echocardiograms or presence of exclusion criteria.

For all analyses, SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used, with a two-sided significance level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Analytic Sample

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 2,833 participants in the main analytic sample are shown by examination year in Table 1 and eTable 2. Characteristics of the CARDIA participants included versus not included are compared in eTable 3. Participants not included (vs included) were slightly younger, more likely to be black or male, had less education, and had somewhat less favorable risk factor profiles at study enrollment.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics at Baseline (1990–91), Overall and by Race and Sex: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study

| Overall | Black Men | Black Women | White Men | White Women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2833 | 517 (18) | 771 (30) | 720 (25) | 825 (29) |

| Age, years | 30.1 (3.6) | 29.4 (3.8) | 29.6 (3.8) | 30.6 (3.3) | 30.6 (3.3) |

| Education, years | 14.6 (2.4) | 13.5 (2.0) | 13.7 (2.0) | 15.5 (2.5) | 15.4 (2.3) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.0 (5.7) | 26.7 (5.2) | 28.1 (7.3) | 25.5 (3.9) | 24.1 (4.8) |

| Heart rate, bpm | 68 (10) | 65 (9) | 70 (10) | 65 (9) | 69 (10) |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 107 (11) | 113 (11) | 107 (10) | 110 (10) | 102 (9) |

| Hypertension | 98 (3) | 32 (6) | 32 (4) | 26 (4) | 8 (1) |

| BP medication | 32 (1) | 6 (1) | 20 (3) | 5 (1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 6 (0.8) | 5 (0.7) | 1 (0.1) |

| Cigarettes per day | 3.2 (7.0) | 3.9 (7.1) | 3.1 (5.9) | 3.4 (8.2) | 2.7 (6.6) |

| Current smoking | 716 (25) | 175 (34) | 235 (31) | 142 (20) | 164 (20) |

| TC, mg/dL | 178 (33) | 181 (35) | 176 (31) | 180 (36) | 176 (30) |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 54 (14) | 52 (15) | 56 (13) | 47 (12) | 59 (14) |

| TC/HDL-C ratio | 3.5 (1.2) | 3.8 (1.2) | 3.3 (0.9) | 4.1 (1.3) | 3.2 (0.9) |

| Cholesterol medication | 6 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.4) |

| Physical activity score | 382 (293) | 488 (345) | 263 (232) | 463 (297) | 357 (259) |

| Alcohol intake, mL/day | 10 (21) | 18 (30) | 6 (22) | 14 (21) | 6 (11) |

Continuous variables are presented as mean (SD). Categorical variables are presented as N (%).

Hypertension was defined by systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg, diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg, or BP medication use.

Diabetes mellitus was defined by fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL, 2-hour glucose ≥200 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1C ≥6.5%, or diabetes medication use.

Bpm, beats per minute; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol.

Patterns of Longitudinal Change in Left Ventricular Structure and Function

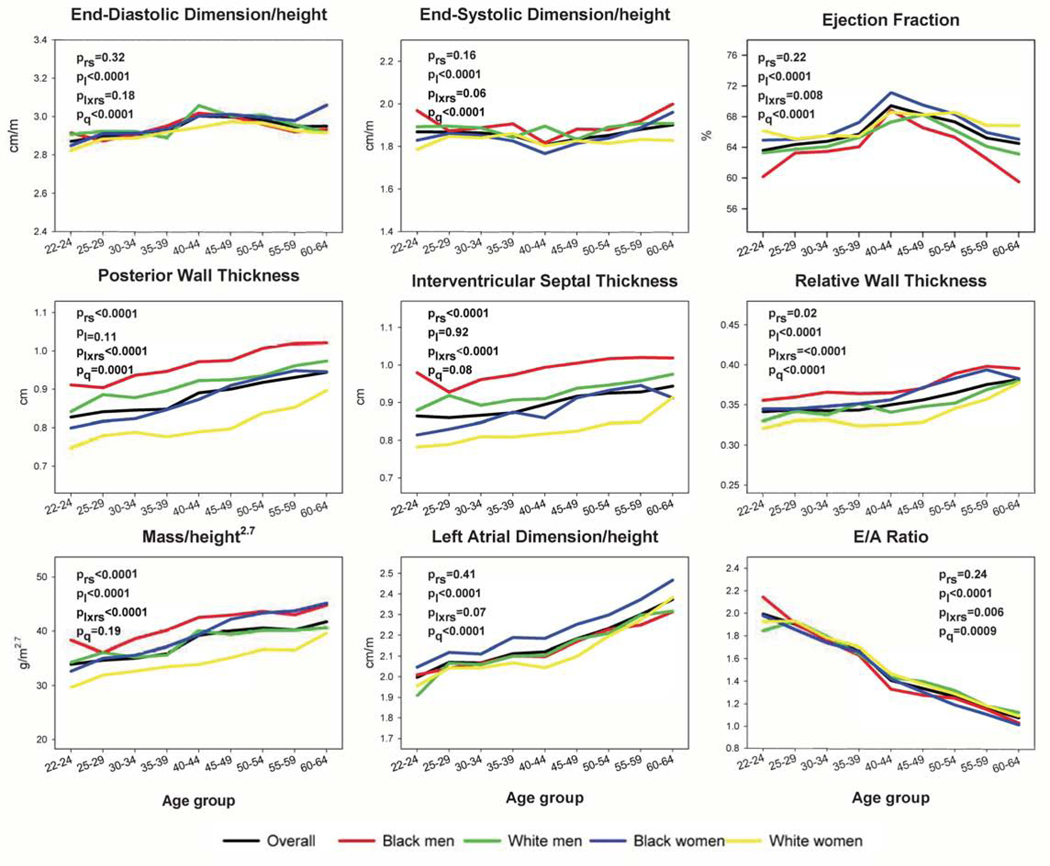

Unadjusted LV parameter means across young adulthood into middle age are shown in Figure 1 and eFigures 3–4. As age increased from 22 to 64 years, mean relative wall thickness (RWT) and indexed LV mass increased significantly (Figure 1). Diastolic parameters generally worsened with age (Figure 1, eFigure 4); for example, indexed left atrial dimension (LAD) increased significantly and E/A ratio decreased significantly with age. Indexed LV cavity dimensions remained nearly flat across young adulthood, and EF had a non-monotonic relationship with age (Figure 1, eFigure 3).

Figure 1. Unadjusted Mean Patterns of Change in Left Ventricular Structure and Function Parameters with Age, Overall and by Race and Sex.

Mean patterns of left ventricular (LV) changes with age were estimated using M-mode measures to maximize sample size. For comparison purposes, y axes are standardized to span 1.5 standard deviations, centered around the mean. P-values are as follows: prs, comparison by race-sex group; pl, linear trend with age; plxrs, age*race-sex interaction; pq, quadratic trend with age. With increasing age, relative wall thickness (RWT), indexed mass, and indexed left atrial dimension (LAD) increased, whereas the ratio of mitral early to late diastolic velocities (E/A) decreased. LV dimensions were nearly flat, and ejection fraction (EF) changed non-monotonically. Statistically significant race-sex differences were observed for EF, posterior wall thickness, interventricular septal thickness, RWT, indexed mass, and E/A ratio. The minimum and maximum sample sizes underlying any data point are as follows: overall 200 (for multiple parameters at age 40–44 years) to 2147 (for indexed LAD and E/A ratio at age 50–54 years); among Black men 31 (for multiple parameters at age 60–64 years) to 390 (for E/A ratio at age 50–54 years); among Black women 59 (for multiple parameters at age 60–64 years) to 575 (for indexed LAD at age 50–54 years); among White men 30 (for multiple parameters at age 40–44 years) to 562 (for E/A ratio at age 50–54 years); and among White women 40 (for multiple parameters at age 40–44 years) to 626 (for E/A ratio at age 50–54 years).

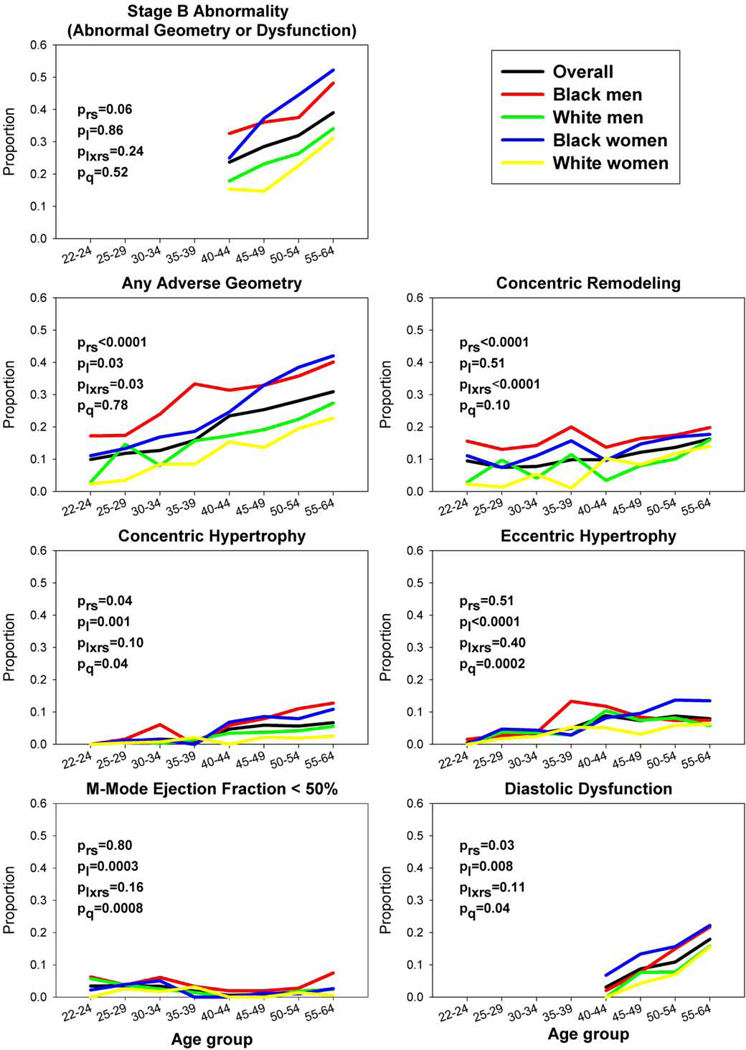

Prevalences of categorical LV outcomes by age are shown in Figure 2, and corresponding predicted probabilities are shown in Table 2 and eTable 4. Overall, the predicted probability of stage B LV abnormalities (i.e., adverse geometry, EF <50%, and/or diastolic dysfunction) increased from 19.5% (95% CI, 16.5–22.9%) at age 40 years (the youngest age of complete measurement including diastolic function) to 45.0% (42.0–48.1%) at age 60 years (Table 2). The predicted probability of adverse geometry increased from 10.5% (9.4–11.8%) at age 25 years to 36.6% (34.6–38.6%) at age 60 years, including increases for concentric remodeling, concentric hypertrophy, and eccentric hypertrophy (eTable 4). The predicted probability of EF <50% remained relatively low (<6%), whereas that of diastolic dysfunction increased sharply with age (from 2.6% to 21.9% from age 40 to 60 years; eTable 4).

Figure 2. Unadjusted Prevalence of Adverse Left Ventricular Outcomes with Age, Overall and by Race and Sex.

The prevalences of adverse left ventricular (LV) outcomes were estimated by age. Age groups 55–59 and 60–64 years were combined due to small sample sizes in some race-sex groups at age 60–64 years. Diastolic dysfunction and stage B abnormalities are shown after age 40–44 years due to unavailability of measures at younger ages (see Methods). P-values are as follows: prs, comparison by race-sex group; pl, linear trend with age; plxrs, age*race-sex interaction; pq, quadratic trend with age. Blacks had higher prevalences than whites of all adverse LV outcomes, and race-sex differences were statistically significant for adverse geometry overall, concentric remodeling, concentric hypertrophy, and diastolic dysfunction. The minimum and maximum sample sizes underlying any data point are as follows: overall 200 (for adverse LV geometry at age 40–44 years) to 2070 (for diastolic dysfunction at age 50–54 years); among Black men 35 (for LV geometry at age 35–39 years) to 351 (for diastolic dysfunction at age 50–54 years); among Black women 66 (for any stage B abnormality at age 40–44 years) to 563 (for diastolic dysfunction at age 50–54 years); among White men 29 (for any stage B abnormality at age 40–44 years) to 535 (for diastolic dysfunction at age 50–54 years); and among White women 40 (for any stage B abnormality at age 40–44 years) to 621 (for diastolic dysfunction at age 50–54 years).

Table 2.

Predicted Probabilities* of Stage B Left Ventricular Abnormalities by Age, Overall and by Race and Sex: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study

| Predicted Probability (%) and 95% Confidence Interval for Any Stage B Left Ventricular Abnormality (Adverse Geometry, Ejection Fraction <50%, and/or Diastolic Dysfunction†, by Age | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 years | 45 years | 50 years | 55 years | 60 years | |

| N with outcome/N total‡ | 45/183 | 258/883 | 603/1825 | 541/1360 | 102/250 |

| Overall | 19.5 (16.5–22.9) | 24.8 (22.3–27.4) | 30.8 (29.1–32.6) | 37.7 (36.0–39.4) | 45.0 (42.0–48.1) |

| Black men | 27.0 (19.3–36.3) | 32.8 (26.8–39.3) | 39.1 (35.1–43.2) | 45.8 (41.2–50.4) | 52.7 (44.9–60.3) |

| Black women | 25.3 (19.4–32.3) | 32.8 (28.0–37.9) | 41.3 (38.0–44.6) | 50.4 (46.8–53.9) | 59.4 (53.6–65.0) |

| White men | 15.1 (10.1–21.8) | 19.7 (15.3–25.0) | 25.2 (22.0–28.8) | 31.7 (28.7–35.0) | 39.1 (33.4–45.0) |

| White women | 7.7 (4.9–11.8) | 12.2 (9.1–16.1) | 18.8 (16.1–21.8) | 27.8 (25.3–30.5) | 39.1 (33.9–44.6) |

An age-squared term was tested and not significant (P>0.05) so was not included in models.

Diastolic dysfunction on the basis of full 2016 American Society of Echocardiography criteria, among participants with ejection fraction ≥50%. Required variables were only available at years 25 and 30; probabilities are thus restricted to ages 40 to 60 years. See text (Methods) for details.

Across race-sex groups, patterns were directionally similar. However, for most parameters and outcomes, there were significant race-sex differences (global race-sex [prs] and/or age*race-sex [plxrs] terms p<.05 in Figures 1–2). Men had larger indexed LV volumes than women (eFigure 3), but differences were minimal for indexed LV dimensions (Figure 1). Although men had higher mean wall thicknesses than women at all ages, age-related increases in RWT and indexed mass appeared to accelerate among black women in middle age (≥45 years), such that race became a stronger correlate of these variables than sex (i.e., higher among black women than white men; Figure 1). On average, EFs were lowest and declined most rapidly in black men, whereas indexed LADs and E/e’ ratios were highest in black women (Figure 1, eFigures 3–4).

Stage B LV abnormalities overall were more common among blacks than whites across ages, with the prevalence among black women surpassing that among black men in middle age (≥45 years) (Figure 2, Table 2). By age 60 years, predicted probabilities of stage B abnormalities were approximately 53–59% for black men and women compared with 39% for white men and women (Table 2). Age-related probabilities were consistent with an acceleration of risk for stage B LV abnormalities by 10–15 years in blacks vs whites (e.g., ~30% probability reached at age 40–45 years in blacks vs 55 years in whites). Race-sex interaction terms reached statistical significance for adverse geometry, which was more common among blacks than whites and increased in prevalence most rapidly among black women, as well as diastolic dysfunction, which was most common among black women (Figure 2, eTable 4).

Associations of Baseline Echocardiographic Parameters with Incident Stage B Left Ventricular Abnormalities 25 Years Later

In the analysis of associations between baseline LV parameters and incident LV abnormalities 25 years later, baseline indexed LV end-systolic dimension (ESD/ht) and mass (mass/ht2.7) were the predictors selected for the final model (Table 3; see also eTables 5–6 for models with single predictors and various combinations of predictors). With full adjustment (including cumulative risk factor burden), associations were strongest between baseline ESD/ht and incident EF <50%, with more than 2.5-times higher odds per 1-SD greater ESD/ht, and between baseline mass/ht2.7 and incident hypertrophy, with 63–70% higher odds per 1-SD greater mass/ht2.7 (Table 3). Baseline ESD/ht was also directly associated with incident eccentric hypertrophy and inversely associated with incident concentric remodeling and concentric hypertrophy, but not with diastolic dysfunction. Conversely, baseline LV mass/ht2.7 was also directly associated with incident diastolic dysfunction, but not with incident concentric remodeling. There were no statistically significant interactions of race-sex group with baseline ESD/ht or mass/ht2.7 for any outcome, nor qualitative race-sex differences upon stratification (data not shown). In sensitivity analyses excluding participants with outlier values of baseline echocardiographic parameters, findings were unchanged (data not shown).

Table 3.

Associations of Significant Baseline Left Ventricular Parameters with Incident Left Ventricular Adverse Geometry*, Ejection Fraction <50%†, or Diastolic Dysfunction‡ 25 Years Later, Adjusted§ for Demographics and Cumulative Risk Factor Burden: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study

| Baseline LV Parameter, per 1 SD|| | Adjusted§ Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) for Outcome at 25-Year Follow-Up | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentric Remodeling | Concentric Hypertrophy | Eccentric Hypertrophy | Ejection Fraction <50% | Diastolic Dysfunction | ||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Outcome N (%)/total N¶ | 264 (18) / 1445 | 66 (5) / 1445 | 72 (5) / 1445 | 50 (3) / 1613 | 137 (13) / 1073 | |||||

| ESD/ht | 0.68 (0.58–0.80) | 0.68 (0.58–0.79) | 0.69 (0.53–0.92) | 0.69 (0.51–0.91) | 1.29 (1.00–1.67) | 1.34 (1.02–1.75) | 2.54 (1.86–3.46) | 2.56 (1.87–3.52) | 0.96 (0.79–1.16) | 0.97 (0.80–1.19) |

| Mass/ht2.7 | 1.06 (0.91–1.24) | 1.03 (0.87–1.21) | 2.10 (1.58–2.79) | 1.63 (1.19–2.24) | 2.24 (1.70–2.97) | 1.70 (1.25–2.32) | 0.83 (0.60–1.14) | 0.77 (0.54–1.10) | 1.42 (1.18–1.70) | 1.24 (1.01–1.52) |

Baseline LV variables were selected for inclusion on the basis of statistically significant univariate associations, potential for collinearity, and clinical relevance.

LV geometry is a polytomous outcome including: concentric remodeling, defined as RWT≥0.42 without hypertrophy; hypertrophy, defined as LVM/ht2.7 >51 g/m2.7 and classified as concentric if RWT≥0.42 and eccentric if RWT<0.42, or normal geometry.

Ejection fraction was measured by 2-dimensional imaging in 780 participants; it was measured by M-mode in 834 participants without a 2-dimensional measurement available.

Diastolic dysfunction is defined as more than half of available indicators abnormal from e’, E/e’, left atrial size, and tricuspid regurgitation jet velocity; see text (Methods) for details.

Model 1 adjusts for demographics (age, sex, race, educational level) and heart rate at 25-year follow-up. Model 2 additionally adjusts for cumulative clinical risk factor burden from baseline to 20 years later (sum of years at level * level of body mass index, systolic blood pressure, total to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio, blood glucose, physical activity, and alcohol intake; and percent of study visits using blood pressure and cholesterol medication).

1 SD for ESD/ht and mass/ht2.7 respectively equals 0.22 cm/m and 7.2 grams/m2.7 for geometry outcomes, 0.22 cm/m and 8.8 grams/m2.7 for ejection fraction outcome, and 0.21 cm/m and 7.8 grams/m2.7 for diastolic dysfunction outcome.

Ns shown are for complete cases analyzed in both Model 1 and Model 2.

E, early diastolic mitral inflow velocity; e’, tissue Doppler myocardial relaxation velocity; ESD, end-systolic dimension; ht, height (meters); LV, left ventricular; M, mass; RWT, relative wall thickness; SD, standard deviation.

Associations Between Continuous Echocardiographic Parameters at Baseline and 25 Years Later

In covariate-adjusted models including all significant echocardiographic predictors for each LV parameter at 25-year follow-up, associations were modest in magnitude (Table 4; see also eTable 7 for single predictors). Interaction testing and stratified analyses revealed modest differences in the associations by race-sex group (e.g., the association of baseline mass/ht2.7 with later mass/ht2.7 was largest in black men but significant in all; interaction p=.01; data not shown). In sensitivity analyses excluding participants with outlier values of baseline echocardiographic parameters, findings were similar (data not shown).

Table 4.

Associations of Significant Baseline Left Ventricular Parameters with Left Ventricular Parameters 25 Years Later, Adjusted* for Demographics and Cumulative Risk Factor Burden: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study

| Baseline LV Parameter, per 1 SD† | Regression Coefficient (β, 95% Confidence Interval) for Association with Left Ventricular Parameter at 25-Year Follow-Up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass/Height2.7 | Relative Wall Thickness | Ejection Fraction | Average E/e’ | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| N‡ | 1618 | 1656 | 1641 | 1566 | ||||

| ESD/ht, per 0.23 cm/m | 1.2 (0.7, 1.7) | 1.2 (0.8, 1.7) | −0.008 (−0.011, −0.004) | −0.009 (−0.013, −0.006) | −1.1 (−1.4, −0.8) | −1.1 (−1.4, −0.8) | −0.03 (−0.2, 0.1) | −0.1 (−0.2, 0.03) |

| Mass/ht2.7, per 8.7 g/m2.7 | 3.0 (2.4, 3.6) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.4) | - | - | 0.03 (−0.2, 0.3) | 0.1 (−0.2, 0.4) | - | - |

| RWT, per 0.06 | - | - | 0.007 (0.004, 0.011) | 0.005 (0.001, 0.009) | - | - | 0.2 (0.1, 0.3) | 0.1 (−0.01, 0.2) |

| EF, per −1 SD | - | - | - | - | −0.3 (−0.6, −0.04) | −0.3 (−0.6, −0.04) | - | - |

| E/A, per 0.50 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.1 (0.01, 0.2) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.3) |

| LAD/ht, per 0.26 cm/m | 1.9 (1.3, 2.4) | 0.8 (0.3, 1.4) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Baseline LV variables were selected for inclusion on the basis of statistically significant univariate associations, potential for collinearity, and clinical relevance. Some cells are empty because the selected sets of baseline variables varied by outcome at 25-year follow-up.

Model 1 adjusts for demographics (age, sex, race, educational level) and heart rate at 25-year follow-up. Model 2 additionally adjusts for cumulative clinical risk factor burden from baseline to 20 years later (sum of years at level * level of body mass index, systolic blood pressure, total to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio, blood glucose, physical activity, and alcohol intake; and percent of study visits using blood pressure and cholesterol medication).

1 SD for each baseline parameter is shown. For EF, 1 SD is 8.0% for M-mode (N=852) and 6.2% for 2D (N=789). Association with outcomes at 25-year follow-up was modeled per 1 SD decrease in baseline EF; all others were per 1 SD increase in the baseline predictor.

Ns shown are for complete cases analyzed in both Model 1 and Model 2.

A, late diastolic mitral inflow velocity; cm, centimeters; E, early diastolic mitral inflow velocity; e’, tissue Doppler myocardial relaxation velocity; EF, ejection fraction; ESD, end-systolic dimension; g, grams; ht, height (meters); LAD, left atrial dimension; LV, left ventricular; m, meters; RWT, relative wall thickness; SD, standard deviation.

Associations of Baseline Echocardiographic Parameters with Incident Clinical (Stage C/D) HF Over >25 Years

Among the 4,097 CARDIA participants with baseline echocardiographic and covariate data available, the median follow-up time was 26.9 years, and 72 fatal or nonfatal clinical (stage C/D) HF events occurred during follow-up (4,025 participants were censored; see eFigure 5). The two baseline LV parameters most associated with incident stage B-defining LV abnormalities, ESD/ht and mass/ht2.7, were each significantly associated with incident clinical HF after full adjustment for baseline demographics, heart rate, and clinical risk factor levels (adjusted HRs per 1-SD higher: 1.56 [1.26–1.93] and 1.42 [1.14–1.75], respectively; Table 5). When both ESD/ht and mass/ht2.7 were included in the model together, the adjusted HR for mass/ht2.7 was somewhat attenuated (Table 5).

Table 5.

Adjusted* Associations of Baseline Left Ventricular Indexed End-Systolic Dimension and Mass with Incident Clinical Heart Failure Events over >25 Years: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study

| Baseline LV Parameter, per 1 SD† | Adjusted* Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) for Clinical Heart Failure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Echocardiographic Predictor in Model | Both Echocardiographic Predictors in Model | |||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Clinical HF N (%)/total N‡ | 72 (1.8)/4097 | 69 (1.8)/3917 | 72 (1.8)/4097 | 69 (1.8)/3917 |

| ESD/ht | 1.73 (1.41–2.11) | 1.56 (1.26–1.93) | 1.43 (1.14–1.78) | 1.44 (1.15–1.81) |

| Mass/ht2.7 | 1.70 (1.44–2.01) | 1.42 (1.14–1.75) | 1.49 (1.23–1.81) | 1.24 (0.99–1.55) |

Model 1 adjusts for baseline demographics (age, sex, race, educational level) and heart rate. Model 2 additionally adjusts for baseline clinical risk factors, including body mass index, systolic blood pressure, total to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio, blood glucose, physical activity, alcohol intake, and use of blood pressure medication (no participants used cholesterol medication at baseline).

1 SD for ESD/ht and mass/ht2.7 respectively equals 0.25 cm/m and 9.3 grams/m2.7.

Ns shown are for complete cases analyzed in the indicated model.

ESD, end-systolic dimension; ht, height (meters); LV, left ventricular; SD, standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

Principal Findings

In this study of a community-based, biracial population of 2,833 young adults aged 22 to 38 years followed with echocardiograms over 25 years, several insights into the natural history of preclinical HF development emerged. First, LV RWT and indexed mass were higher among blacks than same-sex whites throughout young adulthood and middle age, but age-related increases in these two parameters were greatest among black women such that they surpassed white men starting in middle age. Conversely, black men stood out among race-sex groups for the lowest mean EF. Second, categorical stage B LV abnormalities had emerged already by young adulthood and rapidly increased with age, with an overall probability of at least 10% (adverse geometry) by age 25 years, 25% by age 45 years, and 45% by age 60 years. Black-white disparities in stage B abnormalities were prominent from the youngest ages, with acceleration of risks by about 10–15 years compared with whites (e.g., ~30% predicted probability reached at age 40–45 years for blacks vs 55 years for whites), and black women surpassed black men around middle age (≥45 years) to reach nearly 60% probability of any stage B abnormality by age 60 years. Third, among young adults with categorically normal LV structure and function, baseline indexed LV ESD and mass were particularly associated with incident stage B LV abnormalities, with up to 2.5-times greater odds per 1-SD difference (for baseline ESD/ht and incident systolic dysfunction), independent of demographics and cumulative intervening risk factor burden over 25 years. These associations were similar across race-sex groups. Fourth, among the entire CARDIA cohort with data available, 1-SD higher indexed LV ESD and mass at baseline were each significantly associated with 40–50% greater hazards for clinical (stage C/D) HF development during >25 years’ follow-up, independent of baseline demographics and risk factors.

Prior Studies of Age-Related Development of Cardiac Remodeling and Dysfunction

Most studies of age-related cardiac structure and function evolution have focused on participants who were middle-aged or older and predominantly white.19–23 Data in younger, biracial populations are primarily from CARDIA and the Bogalusa Heart Study. Among 1,061 adults aged 24 to 46 years (mean, 37.7) in the Bogalusa Heart Study, the cross-sectional prevalence of adverse geometry was 24% overall and higher among blacks (37%) than whites (23%);24 subsequent changes through adulthood have not been reported. The most comprehensive prior analysis of age-related LV changes in CARDIA examined simple changes between baseline and 20-year follow-up for LV structure (but not function), as well as predictors of those changes.25 This analysis found that adverse changes in geometry were most striking among black women, and that 20-year change in LV indexed mass and RWT were associated with baseline LV indexed mass and RWT independent of baseline and 20-year change in clinical risk factors. A separate CARDIA analysis demonstrated that higher baseline LV indexed mass was also associated with lower EF 20 years later.15 Another CARDIA report noted black-white disparities in all stages of HF development both in young adulthood and middle age, with just 18–22% of blacks vs 35–44% of whites remaining free from any stage (stage 0) and 1.7% of blacks vs 0.3% of whites developing clinical HF (stage C/D) by middle age.26 The current analysis extends these prior findings in three main ways. First, we comprehensively examined LV systolic and diastolic function in addition to geometry, including 25 years of longitudinal data which were augmented through age-based (rather than exam-based) analysis to provide race/sex-specific probabilities of each LV abnormality across the entire spectrum of ages 25 to 60 years. Second, we identified from among a larger set of baseline LV parameters that young-adult ESD/ht and mass/ht2.7, even within normative ranges, are most predictive of incident stage B LV abnormalities. Third, we demonstrated that young-adult ESD/ht and mass/ht2.7 are furthermore significantly associated with the risk for incident clinical (stage C/D) HF events.

Implications

The timing of race- and sex-specific transitions in subclinical LV phenotypes from early to middle adulthood, as revealed in this analysis, can inform strategies to prevent progression through preclinical stages of HF development (from stages A/B to C) and related clinical HF disparities. The 2017 ACC/AHA HF guideline endorsed a prevention strategy of primary care-based natriuretic peptide screening followed by echocardiography and CV specialist care, as such a strategy cut the risks of LV dysfunction and clinical HF nearly in half in a randomized trial of middle-aged or older adults (mean age, 65 years) in Ireland.27 However, the ACC/AHA recommendation included a cautionary note regarding heterogeneity in prevalence and rate of progression among populations.28 The current findings that among blacks the risk of any stage B-defining LV abnormality was accelerated by 10–15 years (vs whites) and reached 52–59% by age 60 years, along with known racial disparities in early-onset (at <50 years) symptomatic HF29 and HF mortality8, together emphasize the importance of studying this strategy and others in multiracial populations including younger individuals. Ongoing developments in race-specific clinical HF risk prediction tools applicable at younger ages30 hold promise as a strategy for early identification of diverse individuals who might benefit from echocardiography and intensive risk factor control. Importantly, a prior report from the middle-aged (45–64 years) Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities cohort estimated that nonoptimal levels of 5 risk factors—BMI, blood pressure, total cholesterol, diabetes and smoking—accounted for 100% of HF events in blacks and 86% in whites.31

Along these lines, the current study also has implications for primordial prevention of HF, i.e., prevention of risk factor development in the first place. We found that the probability of adverse LV geometry was already 10% by age 25 years in our sample, and that even for the 90% with normal baseline geometry, higher indexed LV ESD and mass predicted incident stage B LV abnormalities and clinical (stage C/D) HF events over the ensuing 25 years, independent of clinical risk factor burden. Because early-adult LV ESD and mass in turn represent the cumulative and combined effects of genetics, behaviors, and other exposures during youth, these data suggest the relevance of early-life factors for later-life HF. Despite moderate genome-wide heritability estimates for LV end-systolic volume and mass (39% and 34% among whites), specific genes and corresponding molecular targets have been elusive, particularly among blacks.32–34 On the other hand, consistent with the very high population attributable fractions of clinical risk factors for HF in midlife noted above, epidemiologic studies have demonstrated consistent associations of risk factor levels during youth, including BMI, blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes, with adult LV remodeling24,35–40 and dysfunction38,39,41 and clinical HF.42,43 Moreover, in small clinical populations of children with obesity44 or hypertension,45–47 substantial proportions have already developed adverse LV geometry (e.g., 32–40% of hypertensive youth aged 4 to 22 years45), with higher rates of LV hypertrophy among Hispanic and black youth compared with white youth.45 It is unclear whether reversal of childhood or young-adult adverse LV geometry would fully reverse the related CV risk; among 2,604 adults in the Framingham Heart Study with serial echocardiograms, abnormal LV geometry was associated with increased risk of incident MI, HF, or CV death, even if LV geometry improved over time.48 Primordial prevention, or at least delaying the onset, of risk factors (i.e., the transition to stage A in HF development) would likely have the largest impact on HF incidence and related racial disparities.31,49 Conversely, recent increases in childhood obesity50 and diabetes51 rates may increase the burden of HF in the US beyond that projected based on population aging.2

Strengths and Limitations

Our study benefitted from repeated echocardiography in the same individuals over 25 years from young adulthood into middle age, a unique contribution to understanding normative aging-related LV structure and function across this age range. Additional strengths include the community-based design with a high proportion of black participants, use of standardized, quality-controlled echocardiographic protocols, and comprehensiveness of the data including a variety of echocardiographic parameters and 20-year cumulative risk factor covariates.

The findings should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. First, such a long-term study as this is necessarily subject to the technology available at the time (e.g., at baseline in 1990–91, tissue Doppler imaging was unavailable [as were other more advanced measures such as speckle tracking echocardiography] and 2D measures were available only in a subset). General age-related patterns of cardiac changes are likely robust, but small changes in M-mode-based parameters should be interpreted carefully. Comparison of findings with those from other cohorts should likewise be done carefully; for example, previous reports have suggested that with aging, LV EF increases slightly,20,21 decreases slightly,52 or remains stable,53 depending upon imaging modality (magnetic resonance,20,52 M-mode21 or 2D53 echocardiography), design, and participant characteristics. Second, we acknowledge controversy around diastolic function assessment (e.g., the lack of age adjustment for E/e’) and LV indexing methods (e.g., to height versus body surface area); we selected methods consistent with ASE guidelines12,13 and prior publications,54,55 but comparison of various methods is beyond the scope of our analyses. Third, although retention in CARDIA compares favorably to other long-term cohorts, participants who could not be included in this analysis (due to non-attendance or lack of echocardiogram at baseline or 25-year follow-up) were on average less healthy than included participants; thus our results may underestimate the true community burden of stage B LV abnormalities. Fourth, due to limited sample size and multiple testing, some subgroup and supplemental data should be interpreted cautiously. In particular, single data points of crude prevalences of LV outcomes with age among subgroups should not be overinterpreted. Fifth, our analyses describing age-related LV structure-function changes utilized a combination of longitudinal and cross-sectional data (i.e., each participant had 2–3 echocardiograms over time, rather than at every age from 25–60 years). In analyses by echocardiogram year instead of age, patterns were similar (data not shown). Sixth, detailed examination of the relative contributions of risk factors (e.g., BMI, menopausal status) to sex-race differences in LV structure and function parameters with age was beyond the scope of this study; published55–57 and ongoing58,59 work in CARDIA addresses these factors. Seventh, stage B-defining LV abnormalities are important preclinical intermediates that confer higher risk for clinical HF1,7,28, but are not themselves clinical HF. Although CARDIA participants have not experienced enough HF events to sufficiently power an analysis examining associations between categorical stage B LV abnormalities and clinical HF, we demonstrated significant associations between continuous LV parameters and clinical HF, underscoring the relevance of LV structure and function in young adulthood for clinical HF development.

CONCLUSIONS

In a community-based, biracial cohort of young adults, stage B-defining LV abnormalities were present already in young adulthood, rapidly increased in prevalence with age, and developed at younger ages in blacks compared with whites. Higher indexed LV ESD and mass in young adulthood were significantly associated with incident stage B LV abnormalities and clinical (stage C/D) HF over 25 years. These data underscore the contributions of LV changes during young adulthood and earlier to the population burden of HF and related black-white disparities.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

We examined cardiac changes in black and white young adults over 25 years

At age 25, left ventricular remodeling or dysfunction was present in 10%

Remodeling and dysfunction were accelerated by 10–15 years in blacks (vs whites)

Young-adult cardiac parameters were associated with incident heart failure

Efforts to prevent heart failure should start before young adulthood

Acknowledgements:

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the many people whose collaborative efforts run the CARDIA study. We especially thank Dr. Alexander Arynchyn for his work on quality control of echocardiographic data, Ms. Kimberly Keck for her coordination of the CARDIA echocardiography reading center, and Dr. Henrique Doria de Vasconcellos for his review of the manuscript. We also thank the participants of the CARDIA study for their long-term commitment to the study and important contributions to science. This manuscript has been reviewed by CARDIA for scientific content.

Funding Sources: CARDIA is conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham (HHSN268201800005I & HHSN268201800007I), Northwestern University (HHSN268201800003I), University of Minnesota (HHSN268201800006I), Kaiser Foundation Research Institute (HHSN268201800004I), and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (HHSN268200900041C). AMP was supported in part by research grants from the NHLBI (T32 HL069771 and K23 HL145101) from the NHLBI and from the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Department of Pediatrics. SSK was supported in part by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (KL2TR001424) and American Heart Association (19TPA34890060). The funding sources had no role in study design, the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ACC

American College of Cardiology

- AHA

American Heart Association

- ASE

American Society of Echocardiography

- BMI

body mass index

- CARDIA

Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study

- CI

confidence interval

- CV

cardiovascular

- E/A

ratio of inflow (mitral) peak velocities in early (E) and late (A) diastole

- E/e’

average of ratios of inflow (mitral) peak velocity in early diastole (E) to septal and lateral tissue Doppler myocardial early relaxation (e’) velocities

- EF

ejection fraction

- ESD

end-systolic dimension

- HF

heart failure

- LAD

left atrial dimension

- LV

left ventricle

- MI

myocardial infarction

- OR

odds ratio

- RWT

relative wall thickness

- SD

standard deviation

- US

United States

Footnotes

Disclosures: All authors have read and approved submission of the manuscript. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institutes of Health; or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors report no conflicts of interest. The article is original, does not infringe upon any copyright or other proprietary right of any third party, is not under consideration by another journal, and has not been previously published.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, et al. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(15):e1–e90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, Bluemke DA, Butler J, Fonarow GC, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):606–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandey A, Omar W, Ayers C, LaMonte M, Klein L, Allen NB, et al. Sex and Race Differences in Lifetime Risk of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction and Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circulation. 2018;137(17):1814–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huffman MD, Berry JD, Ning H, Dyer AR, Garside DB, Cai X, et al. Lifetime risk for heart failure among white and black Americans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(14):1510–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor CJ, Ordonez-Mena JM, Roalfe AK, Lay-Flurrie S, Jones NR, Marshall T, et al. Trends in survival after a diagnosis of heart failure in the United Kingdom 2000–2017. BMJ. 2019;364:l223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loehr LR, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Folsom AR, Chambless LE. Heart failure incidence and survival. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(7):1016–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(16):e147–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glynn P, Lloyd-Jones DM, Feinstein MJ, Carnethon M, Khan SS. Disparities in Cardiovascular Mortality Related to Heart Failure in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(18):2354–2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, Hughes GH, Hulley SB, Jacobs DR Jr.,, et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(11):1105–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardin JM, Wong ND, Bommer W, Klopfenstein HS, Smith VE, Tabatznik B, et al. Echocardiographic design of a multicenter investigation of free-living elderly subjects. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1992;5(1):63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28(1):1–39 e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, Byrd BF 3rd, Dokainish H, Edvardsen T, et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016;29(4):277–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CARDIA Scientific Resources: Exam Materials. https://www.cardia.dopm.uab.edu/exam-materials2. Accessed August 20, 2019.

- 15.Kishi S, Armstrong AC, Gidding SS, Jacobs DR Jr., Sidney S, Lewis CE, et al. Relation of left ventricular mass at age 23 to 35 years to global left ventricular systolic function 20 years later. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(2):377–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CARDIA Endpoint Events Manual of Operations. http://www.cardia.dopm.uab.edu/images/more/recent/CARDIA_Endpoint_Events_MOO_v03_20_2015.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed May 19, 2020.

- 17.Sidney S, Jacobs DR Jr., Haskell WL, Armstrong MA, Dimicco A, Oberman A, et al. Comparison of two methods of assessing physical activity in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133(12):1231–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagueh SF, Appleton CP, Gillebert TC, Marino PN, Oh JK, Smiseth OA, et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10(2):165–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lieb W, Xanthakis V, Sullivan LM, Aragam J, Pencina MJ, Larson MG, et al. Longitudinal tracking of left ventricular mass over the adult life course. Circulation. 2009;119(24):3085–3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng S, Fernandes VR, Bluemke DA, McClelland RL, Kronmal RA, Lima JA. Age-related left ventricular remodeling and associated risk for cardiovascular outcomes. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(3):191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng S, Xanthakis V, Sullivan LM, Lieb W, Massaro J, Aragam J, et al. Correlates of echocardiographic indices of cardiac remodeling over the adult life course. Circulation. 2010;122(6):570–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borlaug BA, Redfield MM, Melenovsky V, Kane GC, Karon BL, Jacobsen SJ, et al. Longitudinal changes in left ventricular stiffness. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(5):944–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kane GC, Karon BL, Mahoney DW, Redfield MM, Roger VL, Burnett JC Jr.,, et al. Progression of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and risk of heart failure. JAMA. 2011;306(8):856–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai CC, Sun D, Cen R, Wang J, Li S, Fernandez-Alonso C, et al. Impact of long-term burden of excessive adiposity and elevated blood pressure from childhood on adulthood left ventricular remodeling patterns. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(15):1580–1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gidding SS, Liu K, Colangelo LA, Cook NL, Goff DC, Glasser SP, et al. Longitudinal determinants of left ventricular mass and geometry. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(5):769–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gidding SS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Lima J, Ambale-Venkatesh B, Shah SJ, Shah R, et al. Prevalence of American Heart Association Heart Failure Stages in African-American and White Young and Middle Aged Adults. Circ Heart Fail. 2019;12(9):e005730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ledwidge M, Gallagher J, Conlon C, Tallon E, O’Connell E, Dawkins I, et al. Natriuretic peptide-based screening and collaborative care for heart failure: the STOP-HF randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(1):66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Colvin MM, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2017;23(8):628–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bibbins-Domingo K, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Gardin JM, Arynchyn A, et al. Racial differences in incident heart failure among young adults. New Engl J Med. 2009;360(12):1179–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan SS, Ning H, Shah SJ, Yancy CW, Carnethon M, Berry JD, et al. 10-Year Risk Equations for Incident Heart Failure in the General Population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(19):2388–2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folsom AR, Yamagishi K, Hozawa A, Chambless LE, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study I. Absolute and attributable risks of heart failure incidence in relation to optimal risk factors. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2(1):11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vasan RS, Glazer NL, Felix JF, Lieb W, Wild PS, Felix SB, et al. Genetic variants associated with cardiac structure and function: a meta-analysis and replication of genome-wide association data. JAMA. 2009;302(2):168–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aung N, Vargas JD, Yang C, Cabrera CP, Warren HR, Fung K, et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of Left Ventricular Image-Derived Phenotypes Identifies Fourteen Loci Associated With Cardiac Morphogenesis and Heart Failure Development. Circulation. 2019;140(16):1318–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fox ER, Musani SK, Barbalic M, Lin H, Yu B, Ogunyankin KO, et al. Genome-wide association study of cardiac structure and systolic function in African Americans: the Candidate Gene Association Resource (CARe) study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2013;6(1):37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toprak A, Wang H, Chen W, Paul T, Srinivasan S, Berenson G. Relation of childhood risk factors to left ventricular hypertrophy (eccentric or concentric) in relatively young adulthood. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(11):1621–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang T, Li S, Bazzano L, He J, Whelton P, Chen W. Trajectories of Childhood Blood Pressure and Adult Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2018;72(1):93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan Y, Liu J, Wang L, Hou D, Zhao X, Cheng H, et al. Independent influences of excessive body weight and elevated blood pressure from childhood on left ventricular geometric remodeling in adulthood. Int J Cardiol. 2017;243:492–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robertson J, Schaufelberger M, Lindgren M, Adiels M, Schioler L, Toren K, et al. Higher Body Mass Index in Adolescence Predicts Cardiomyopathy Risk in Midlife: Long-Term Follow-Up Among Swedish Men. Circulation. 2019;140:117–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.TODAY Study Group. Longitudinal Changes in Cardiac Structure and Function From Adolescence to Young Adulthood in Participants With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13:e006685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bazzano LA, Belame SN, Patel DA, Chen W, Srinivasan S, McIlwain E, et al. Obesity and left ventricular dilatation in young adulthood. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34(3):153–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heiskanen JS, Ruohonen S, Rovio SP, Kyto V, Kahonen M, Lehtimaki T, et al. Determinants of left ventricular diastolic function. Echocardiography. 2019;36(5):854–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosengren A, Aberg M, Robertson J, Waern M, Schaufelberger M, Kuhn G, et al. Body weight in adolescence and long-term risk of early heart failure in adulthood among men in Sweden. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(24):1926–1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindgren M, Aberg M, Schaufelberger M, Aberg D, Schioler L, Toren K, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and muscle strength in late adolescence and long-term risk of early heart failure in Swedish men. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24(8):876–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jing L, Binkley CM, Suever JD, Umasankar N, Haggerty CM, Rich J, et al. Cardiac remodeling and dysfunction in childhood obesity. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016;18(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hanevold C, Waller J, Daniels S, Portman R, Sorof J, International Pediatric Hypertension A. The effects of obesity, gender, and ethnic group on left ventricular hypertrophy and geometry in hypertensive children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(2):328–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daniels SR, Loggie JM, Khoury P, Kimball TR. Left ventricular geometry and severe left ventricular hypertrophy in children and adolescents with essential hypertension. Circulation. 1998;97(19):1907–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richey PA, Disessa TG, Somes GW, Alpert BS, Jones DP. Left ventricular geometry in children and adolescents with primary hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23(1):24–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lieb W, Gona P, Larson MG, Aragam J, Zile MR, Cheng S, et al. The natural history of left ventricular geometry in the community. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7(9):870–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Avery CL, Loehr LR, Baggett C, Chang PP, Kucharska-Newton AM, Matsushita K, et al. The population burden of heart failure attributable to modifiable risk factors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(17):1640–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skinner AC, Ravanbakht SN, Skelton JA, Perrin EM, Armstrong SC. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity in US Children, 1999–2016. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dabelea D, Mayer-Davis EJ, Saydah S, Imperatore G, Linder B, Divers J, et al. Prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among children and adolescents from 2001 to 2009. JAMA. 2014;311(17):1778–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoneyama K, Donekal S, Venkatesh BA, Wu CO, Liu CY, Souto Nacif M, et al. Natural History of Myocardial Function in an Adult Human Population. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(10):1164–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hung C-L, Gonçalves A, Shah AM, Cheng S, Kitzman D, Solomon SD. Age- and Sex-Related Influences on Left Ventricular Mechanics in Elderly Individuals Free of Prevalent Heart Failure. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(1):e004510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Echocardiographic Normal Ranges Meta-Analysis of the Left Heart Collaboration. Ethnic-Specific Normative Reference Values for Echocardiographic LA and LV Size, LV Mass, and Systolic Function: The EchoNoRMAL Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(6):656–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Desai CS, Ning H, Liu K, Reis JP, Gidding SS, Armstrong A, et al. Cardiovascular Health in Young Adulthood and Association with Left Ventricular Structure and Function Later in Life. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28(12):1452–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khan SS, Shah SJ, Colangelo LA, Panjwani A, Liu K, Lewis CE, et al. Association of Patterns of Change in Adiposity With Diastolic Function and Systolic Myocardial Mechanics From Early Adulthood to Middle Age. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2018;31(12):1261–1269 e1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Appiah D, Schreiner PJ, Nwabuo CC, Wellons MF, Lewis CE, Lima JA. The association of surgical versus natural menopause with future left ventricular structure and function. Menopause. 2017;24(11):1269–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Appiah D, Nwabuo CC, Ebong I, Vasconcellos HD, Wellons MF, Lewis CE, et al. Does age at natural menopause influence changes in left ventricular structure and function during the menopausal transition? The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study [abstract]. Circulation. 2019;139:AP411. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lloyd-Jones DM, Colangelo LA, Lewis CE, Schreiner P, Sidney S, Gidding SS, et al. Association of risk factor exposure patterns through young adulthood with left ventricular structure/function in middle age: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study [abstract]. Circulation. 2017;135:AP367. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.