Abstract

Psychological stress is common in patients with heart failure, due in part to the complexities of effective disease self-management and progressively worsening functional limitations, including frequent symptom exacerbations and hospitalizations. Emerging evidence suggests that heart failure patients who experience higher levels of stress may have a more burdensome disease course, with diminished quality of life and increased risk for adverse events, and that multiple behavioral and pathophysiological pathways are involved. Furthermore, the reduced quality of life associated with heart failure can serve as a life stressor for many patients. The purpose of this review is to summarize the current state of the science concerning psychological stress in patients with heart failure and to discuss potential pathways responsible for the observed effects. Key knowledge gaps are also outlined, including the need to understand patterns of exposure to various heart failure-related and daily life stressors and their associated effects on heart failure symptoms and pathophysiology, to identify patient subgroups at increased risk for stress exposure and disease-related consequences, and the effect of stress specifically for patients who have heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Stress is a potentially modifiable factor, and addressing these gaps and advancing the science of stress in heart failure is likely to yield important insights about actionable pathways for improving patient quality of life and outcomes.

Keywords: heart failure, psychological, stress, mental, behavioral

Heart failure (HF) is a progressive disease with considerable variation in the clinical course. Patients who survive a first episode of acute HF subsequently experience an unpredictable trajectory, typically characterized by varying periods of symptom stability interspersed with episodes of decompensation. Generally, as HF progresses, symptom exacerbations become more frequent and recovery to prior health status less likely [1]. While underlying pathophysiology and treatment approaches play a pivotal role in this process, the course is also influenced by patient-level variables, including lifestyle, self-care and treatment adherence, and psychosocial factors [2–4]. Psychological stress is a less frequently considered but potential disease modifier. As a chronic, life-threatening illness, HF is itself a potent stressor, and there is accumulating evidence that high levels of stress adversely impact HF disease progression [5–10]. In this focused review we describe and evaluate the literature concerning stress and HF, and identify critical knowledge gaps in need of further study, thereby setting the stage for advancing the science of this factor.

Stress and HF Progression

Population-based studies concerning particularly salient and sustained stressors suggest that psychological stress is associated with adverse outcomes in HF (see Table 1). A nationwide study of 111,970 US Veteran men with HF examined the relationship of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a chronic stress condition, to HF outcomes using retrospective electronic health record data [5]. In this sample, having a diagnosis of PTSD was associated with higher all-cause mortality starting 2 years after the initial HF diagnosis [5]. This analysis controlled for an extensive number of possible confounders, but generalizability is limited as the sample was restricted to only Veteran men with reduced ejection fraction who were prescribed a beta-blocker.

Table 1.

Summary of Studies Examining the Effects of Psychological Stress in Patients with Heart Failure

| Study | Design | Sample | Stress exposure/assessment | HF Metric | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fudim et al., 2018 [5] | Retrospective using EHR data | 111,970 US Veteran men | PTSD diagnosis | All-cause mortality | PTSD prior to HF onset was associated with higher all-cause mortality starting 2 years after HF diagnosis. |

| Aoki et al., 2012 [6] Nakamura et al., 2016 [7] | Retrospective using ambulance and hospital records | ~300,000 residents of Northeastern Japan | 2011 Catastrophic earthquake and tsunami | HF hospitalizations | HF admissions increased beyond pre-disaster rates and remained elevated 4 years post-disaster. |

| Kažukauskienė et al., 2019 [8] | Prospective | 481 HF patients attending inpatient cardiac rehabilitation post-ACS event | Single administration of Major Life Events Scale at baseline (prior year stressful events) | HF-related quality of life assessed at baseline, and 6, 12, 18, and 24 months | Prior year stress exposure was independently and inversely associated with HF-related quality of life at baseline only; Quality of life was poorest among patients with moderate to high stress exposure. |

| Alhurani et al., 2014 [21] | Prospective | 81 hospitalized HF patients | Single administration of 4-item Perceived Stress Scale at baseline (perceived stress) | 6-month cardiac-related re-hospitalization and mortality | Perceived stress was elevated in the sample but not associated with outcomes. |

| Endrighi et al., 2016 and 2019 [9,10] (BETRHEART Study) | Prospective | 144 ambulatory, non-hospitalized NYHA II-IV HF patients | Repeat, bi-weekly administration of 10-item Perceived Stress Scale over 3 months (perceived stress) | Functional and health status assessed biweekly over 3 months and 9-month cardiac hospitalization and all-cause mortality | Increased perceived stress was associated with worsening in functional status and health status; 3-month average stress was associated with average health status and predictive of adverse events; Hospitalizations were associated with increased stress. |

EHR = electronic health record; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; HF = heart failure; ACS = acute coronary syndrome; NYHA = New York Heart Association

More generalizable, naturalistic observations were made in a series of studies conducted in northeastern Japan after the region was devastated by a catastrophic earthquake and tsunami in 2011. HF admissions increased in the months following the disaster and remained elevated four years post-event in the most affected areas [6,7]. The sustained long-term elevations in HF admissions may have been due to continued stressful post-disaster sequelae, including PTSD, as even years after the event, unemployment remained high, many still resided in temporary housing, and searches continued for individuals missing since the disaster [7]. Unfortunately, the data needed to test this hypothesized mechanism – i.e., patient interviews or information on the individual socioeconomic and mental health status of admitted patients – were not collected.

Other studies in HF samples have directly queried patients about stress. There are varied methods used to accomplish this assessment and each has its strengths and limitations (see Table 2) [11–20]. In one study conducted in an inpatient cardiac rehabilitation setting, 481 HF patients post-acute coronary syndrome completed the Social Readjustment Rating Scale, a checklist measure where respondents indicate if they’ve experienced any of 43 objectively considered stressful events during the prior year [8,11]. HF-related quality of life was assessed at baseline and prospectively every six months for two years. A cross-sectional inverse association was found at baseline between prior year stressful life event exposure and current HF-related quality of life, independent of demographics, health status, and other psychosocial factors, and the greatest effect was observed for patients endorsing moderate to high stress exposure; no relationship was found however, between stressful life events reported at baseline and later HF-related quality of life [8].

Table 2.

Overview of Available Patient-Report Measures of Psychological Stress

| Stress Data | Methods | Example Measures | Details | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stressful life events | Checklist questionnaires | Social Readjustment Rating Scale [11]; Crisis in Family Systems [12] | List of major life events objectively considered stressful; stressors are weighted by severity (e.g., divorce weighted more than obtaining a loan) | Captures exposure to a wide range of stressful life events over a one’s lifetime or a specified period (i.e., past year), often freely available and easy to administer | Not comprehensive, does not capture stress caused by the non-occurrence of events, severity scores may not align with respondent perceptions |

| Comprehensive inventories | Life Events and Difficulties Schedule [13]; Life Events Assessment Profile [14]; Stress and Adversity Inventory [15] | Semi-structured interviews or computer adaptive testing used to collect information about stressful events across life domains | More detailed than checklists, respondents rate the severity of events | Can be expensive and time-consuming to administer and score | |

| Domain-specific questionnaires | City Stress Inventory [16]; Experiences of Discrimination [17] | Specific sources of stress (e.g., discrimination) or stress experienced within specific domains (i.e., neighborhood, job, relationships) | Good for addressing research questions about specific types of stress exposures, often freely available and easy to administer | Narrow scope, may not ask about all potential sources of stress within a domain | |

| Trauma questionnaires | Brief Trauma Questionnaire [18]; Life Events Checklist [19] | Includes traumatic events considered severe enough to meet threshold for PTSD (e.g., combat, assault, serious accident) | Easy to administer and freely available from the National Center for PTSD | Narrow scope, not a comprehensive list of all traumas, cannot be used to make a diagnosis of PTSD | |

| Subjective perceptions of stress | General questionnaires | Perceived Stress Scale [20] | Assesses the degree to which recent life experiences are considered stressful or overwhelming | Strong psychometric properties, easy to administer, freely available, broad applicability to diverse populations, considers stress due to the non-occurrence of events | Asks only about recent experiences, single administrations have limited predictive validity for long-term outcomes |

This methodology of testing the association of a single baseline stress assessment to later outcomes was used in another study, of 81 hospitalized HF patients, who during their inpatient stay completed the 4-item screening version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), which measures feeling in control of vs. overwhelmed by recent life occurrences (see Table 2). Cardiac-related re-hospitalization and mortality were tracked for 6 months [20,21]. Perceived stress was elevated in this sample compared to values obtained in samples of non-hospitalized healthy adults and patients with other cardiovascular diseases [20,21], and this is not surprising, since HF hospitalization can feel overwhelming. This single assessment of stress however, was not prospectively associated with 6-month event-free survival [21]. The choice of a very brief stress screening measure and single assessment at the time of hospitalization may have been insufficient for capturing the natural variation in stress as it is experienced over time and thus, the contribution of this factor to re-hospitalization and mortality. For example, it may be that most patients would endorse high stress during hospitalization, but it is the patient who continues to endorse high stress after discharge that is more likely to be re-hospitalized or die over the subsequent follow-up period.

Repeat assessment of stress and thus, changes in stress over time, may be a better approach for testing the prospective association between stress and longer-term outcomes. This approach was used in the Biobehavioral Triggers of HF (BETRHEART) Study [9,10]. A sample of 144 ambulatory, non-hospitalized HF patients completed a phone assessment of stress with the 10-item PSS every two weeks for three months. Functional status and health status (i.e., symptom severity and quality of life) were measured at an in-person visit a few days after each PSS assessment, with clinical outcomes tracked for nine months from baseline assessment. Controlling for demographics and markers of HF disease severity, patients with higher average stress across the 3-months of PSS administrations had worse average HF health status during the same period [9]. Additionally, when participants reported a PSS score that was higher than their 3-month average, they were more likely to demonstrate worsening in health status and functional status at the in-person assessment that followed a few days later [10]. This timing suggests that experiencing increased stress may adversely impact HF status however, this design does not rule out the possibility of the reverse effect - e.g. that worsening HF status was the precipitating factor that caused the increase in stress.

The prospective association between stress and cardiac-related outcomes was also tested. Controlling for demographics, markers of HF severity, body mass index, smoking, and hypertension, sustained high stress across the 3-months of PSS administrations was associated with a significantly higher risk for cardiac-related hospitalizations and mortality during the 9-month follow-up (OR=1.10, 95% CI=1.04 to 1.17 per unit PSS score) [10]. A post-hospitalization stress effect was also observed, with >60% of those hospitalized reporting higher stress on assessments occurring after the hospitalization, compared to assessments not following a hospitalization [10]. It is important to note that the BETRHEART sample was predominantly African American, male, and comprised of HF patients with reduced ejection fraction, thus limiting generalizability.

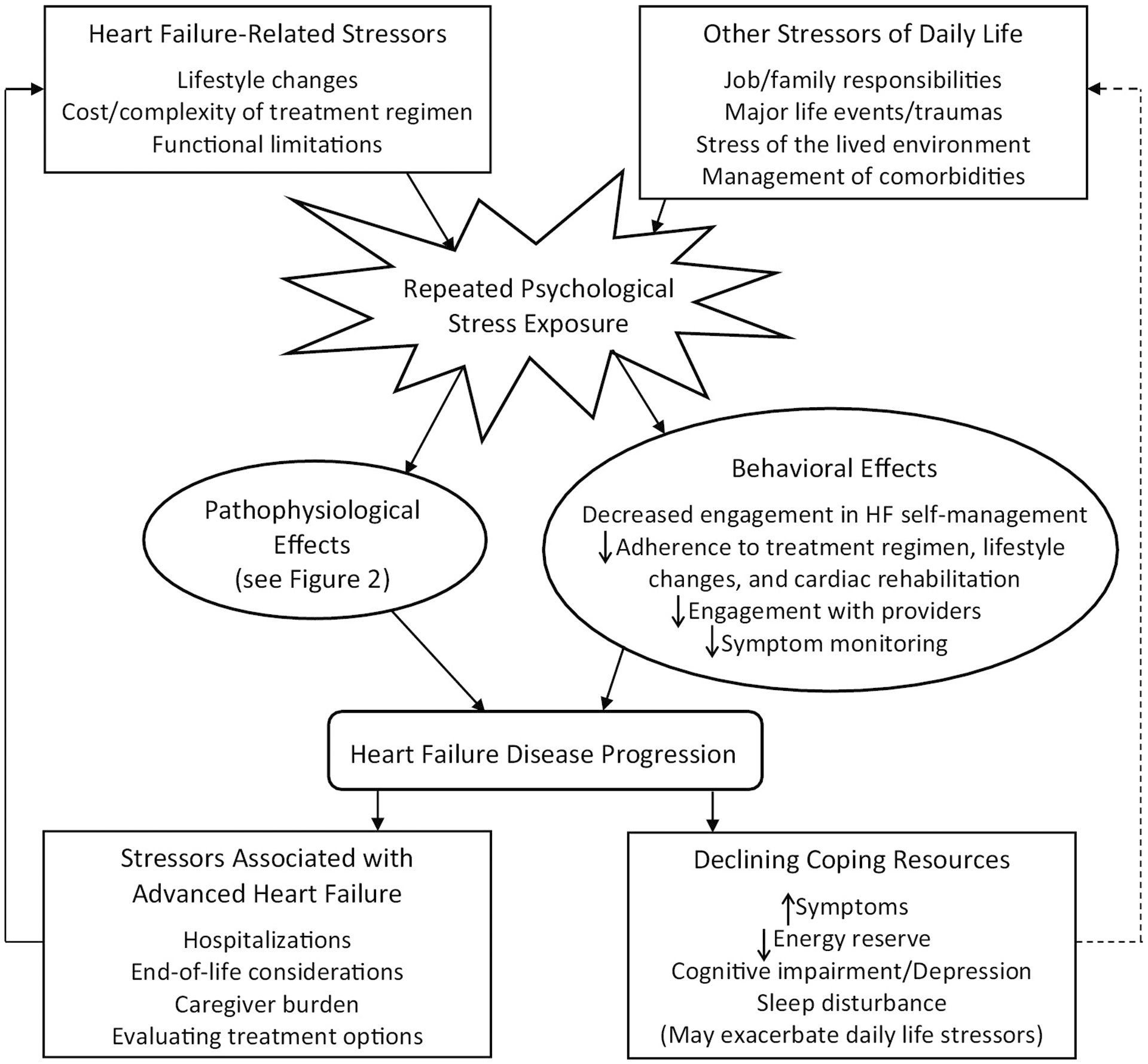

While preliminary and suggestive, and based on data derived from relatively small samples of HF patients with reduced ejection fraction, the current literature reveals that, 1) repeated exposure to major life stress, sustained higher perceived stress, and short-term elevations in perceived stress may adversely affect disease burden and make the day-to-day HF experience more challenging, 2) sustained perceived stress increases risk for short-term adverse outcomes, and 3) hospitalizations often increase stress [5–10]. Stress is likely to fluctuate, and these studies suggest that a clearer effect on the HF clinical course may emerge when change in stress exposure and overall average stress level are examined over an extended period. In each of the reviewed studies, potential mechanisms linking stress (i.e., perceived stress, stressful life event exposure, PTSD) to HF progression were not directly tested. In the following section we review both physiological and behavioral pathways that may be involved (see Figures 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Proposed cyclical relationship of psychological stress and heart failure progression

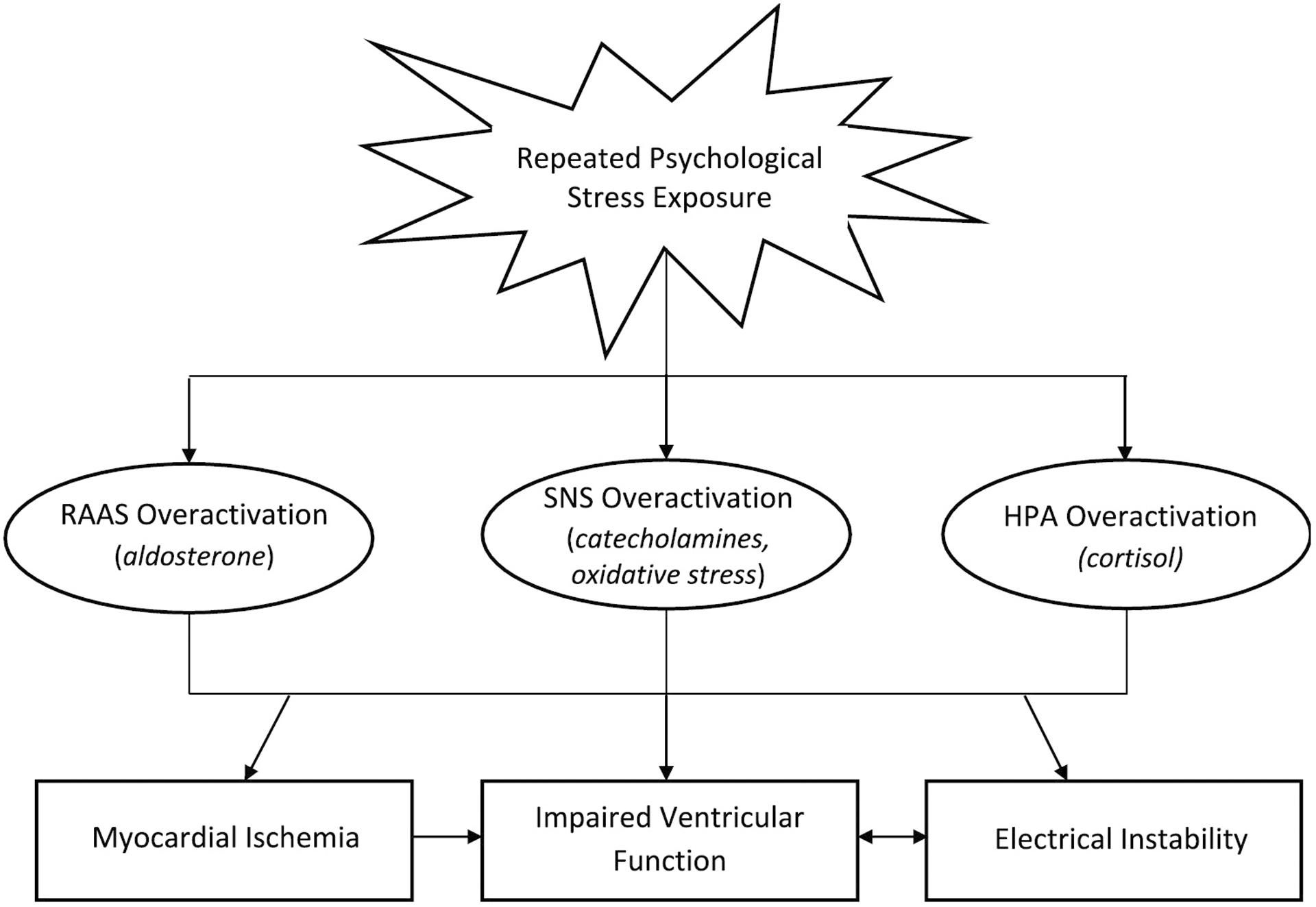

Fig. 2.

Potential pathophysiological effects of stress in heart failure

RAAS = renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; SNS = sympathetic nervous system; HPA = hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis; Italics are used to indicate specific hypothesized chemical messengers and mechanistic processes

Potential Pathophysiological Mechanisms

In healthy adults, psychological stress evokes an adaptive physiological response characterized by increased autonomic and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity and the associated downstream consequences, including reduced cardiac vagal tone, and catecholamine and cortisol release. This cascade results in increased heart rate, cardiac output, and blood pressure, inflammatory cytokine release, and alterations to hemostasis and thrombosis, each orchestrated to support the individual’s response to the stress. A successful response is associated with a return to baseline autonomic and HPA axis activity, whereas chronic stress is associated with chronically elevated activity [22,23].

HF pathophysiology is also characterized by profound changes in sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) activity [24,25]. As the left ventricle increasingly fails, a compensatory increase in SNS activity and hormonal secretion drives chronotropic and inotropic support of cardiac output [22,24,25]. However, by increasing angiotensin II and cytokines and decreasing nitric oxide, these compensatory processes promote further ventricular dilation and remodeling. SNS activity may also cause catecholamine-induced cardiotoxicity and oxidative damage to the myocardium [24]. Beta-blockers and angiotensin and aldosterone blockers improve outcomes in HF by disrupting this cycle. By inhibiting sympathetic input to cardiac adrenergic receptors and dampening RAAS activation, respectively, these medications improve ventricular performance and reverse remodeling [22,24,25]. Psychological stress may impede these efforts as, even with beta-blockade, cortisol can promote ventricular damage by acting as a mineralocorticoid receptor agonist to mimic the effects of aldosterone in the myocardium [26,27].

Research has shown that patients taking standard HF medications continue to display stress-induced physiological responses, possibly due to only partial blockade of the SNS and RAAS, and/or through effects on other pathways such as the cytokine system [28,29] (see Figure 2). For example, research in patients with compromised ventricular function treated with implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) demonstrates that routine daily stress can trigger potentially fatal ventricular arrhythmias [29], as can acute psychological stress administered under controlled conditions. ICD patients with acute stress triggered arrhythmias also demonstrated high catecholamine release during the stress [30]. Stress, through direct effects on cardiac conduction, or indirectly through catecholamine release, is thought to promote heterogeneity of ventricular denervation and repolarization and thus increase arrhythmia risk [30,31]. Such effects may be more pronounced in HF patients due to electrical instability from myocardial damage and remodeling [32].

In the BETRHEART study, a subset of patients - those with ischemic cardiomyopathy - completed a standard laboratory psychological stress protocol [33], comprised of sequential rest, stress, and recovery conditions [c.f., 30, 34], while wall motion was assessed by cardiac ECHO and myocardial perfusion was assessed by SPECT. Overall, two-thirds of patients demonstrated a new reversible myocardial perfusion deficit with stress - mental stress induced myocardial ischemia (MSIMI) - thought to result from stress-induced inflammation, coronary microvascular dysfunction, and/or endothelial dysfunction [33,34]. Although beta-blockade was held in this sample the morning of testing, previous research has shown that these medications do not reduce likelihood of MSIMI [34]. Thus, another pathway through which stress may affect the course of HF is by contributing to the ischemic burden of the disease. Perfusion deficits from acute or chronic stress exposure have the potential to worsen symptoms (dyspnea, angina), further impair ventricular functioning, and increase adverse events [33,34]. While prior evidence suggests ACE inhibition may protect against MSIMI due to its effect on endothelial function and epicardial and coronary microvascular vasomotion [35], the majority of BETRHEART substudy participants demonstrated MSIMI, and all but one were on a RAAS inhibitor, including on the testing day. On cardiac ECHO, two-thirds of patients (43% of whom also demonstrated MSIMI) exhibited an acute stress-induced worsening in left ventricular filling pressure (E/e’ ratio). These patients had higher systemic vascular resistance and lower stroke volume during stress and greater stress-induced increases in diastolic blood pressure [36]. Although the long-term effects are unknown, this finding suggests that stress may also exert a direct, transient effect on ventricular relaxation in HF, possibly through acute pressure load, a mechanism that needs confirmation in future research using invasive hemodynamic monitoring.

Heterogeneity has been observed for stress-related effects on cardiac conduction, myocardial perfusion, and diastolic function in HF, with some patients demonstrating a larger response to stress than others. Factors related to differential physiological stress response in HF patients have yet to be identified. In BETRHEART, demographic and clinical characteristics and resting ventricular function did not differ between patients who did vs. those who did not demonstrate stress-induced effects however, power to detect these differences may have been limited by the small sample size. It is possible that patients with advanced HF or a higher comorbidity burden may be more vulnerable to the effects of catecholamines or cortisol that are released during stress. Psychiatric comorbidities, including depression, anxiety, and PTSD, may also amplify the acute and chronic effects of stress in HF. Each of these disorders is associated with autonomic dysregulation, and with cognitive distortions that can influence stress perception by heightening awareness to potential threats and reducing coping capacity [37–40]. Patients with these comorbidities are therefore likely to experience greater perceived stress related to daily life occurrences, including aspects of their HF management, and an exaggerated and/or prolonged autonomic response to these stress exposures. Other patient psychological characteristics may also be relevant. In non-HF samples, chronic stress exposure, early life stress, and use of maladaptive coping strategies have each been associated with greater stress reactivity, whereas social support has been associated with attenuated stress reactivity [41,42]. The relationship of these factors and psychiatric comorbidities to stress-related physiological effects in HF remains to be investigated. Lastly, while there are likely multiple physiological pathways through which stress may affect HF progression, observed relationships may be bi-directional. For example, the underlying sympathetic and neurohormonal disarray in HF may cause patients to experience an increased or prolonged response when exposed to a stressor.

Potential Behavioral Pathways

Stress is in part comprised of a subjective emotional experience that occurs when demands exceed a person’s resources [43]. When faced with repeated psychological stress exposures, patients will have limited resources (e.g., time, energy) to devote to their HF care. Thus, while speculative and in need of empirical investigation, we propose that another pathway through which stress may affect HF progression is by limiting engagement in effective disease self-management. Patients who feel overwhelmed, either by their HF or other stressors of daily life, may be less adherent to their treatment regimen or monitoring of symptoms and delay medical follow-up, each of which may contribute to hastened disease progression. Additionally, low participation in cardiac rehabilitation is a serious problem among patients with HF, with an analysis of Medicare beneficiaries from 2016–2017 showing that only 2.7% of eligible HF patients attended cardiac rehabilitation and, among these, only 19.1% completed all 36-sessions [44]. Stress may be one factor that can influence whether a patient decides - or is even able - to initiate and complete cardiac rehabilitation. Indeed, in a recent retrospective study of patients who were primarily post-acute myocardial infarction, higher dropout from cardiac rehabilitation was observed among those who reported elevated stress at program entry [45].

Heart Failure as a Stressor

HF is a unique chronic stressor due to the unpredictability of symptom exacerbations and increasing likelihood of frequent hospitalizations as the disease progresses [1]. Each of these can promote further stress, in a positive feedback loop (see Figure 1). HF-related stress is likely to begin at diagnosis and increase as the disease progresses and new demands are encountered. Once diagnosed, patients must quickly learn the management of a complex medication regimen and associated lifestyle adjustments [2,46]. Patients often feel ill-equipped to maintain this self-care, and adherence can drain resources (time, money), further increasing stress [46–48]. The financial burden may be particularly stressful for HF patients. A 2014 study of 149 HF patients estimated annual out-of-pocket healthcare costs at between $3913 to $5829, with 54% reporting not enough, or just enough, money to cover monthly expenses [49]. This burden has likely been increased by newer therapeutics such as angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors which cost Medicare Part D beneficiaries almost $1400 more in annual copay costs compared to angiotensin receptor blockers [50].

HF-related symptoms reduce a patient’s energy reserve, which can make it increasingly challenging to meet the responsibilities of daily life related to one’s job, family, or caregiving duties, and limit the ability to engage in previously enjoyable activities, contributing to diminished quality of life [48]. Additionally, HF is rarely a patient’s only medical condition and may not be their most stressful condition, with evidence from community-based cohorts suggesting that, on average, patients have 6 additional chronic medical or psychiatric conditions [51]. The complexity of self-management in the setting of multiple comorbidities can be overwhelming, and furthermore, many of the most common comorbidities can complicate HF management. For instance, depression and cognitive impairment, common in patients with HF, may affect the capacity to acquire and understand disease-related information, evaluate treatment options, and engage in goal-directed behavior [4,52], making disease self-management a more stressful process. Sleep disturbance is also common in HF and higher stress has been reported in patients with a greater number of nighttime awakenings [53]. Furthermore, in HF patients with ICDs, the anticipated or actual experience of shocks may increase stress [54]. In advanced HF, deciding whether to pursue transplant or left ventricular assist device (LVAD) placement may also be stressful, along with the waiting time for receiving a selected therapy [55], and then learning and following the complex post-transplant or LVAD management regimen.

Symptom fluctuation is typical in HF, even among treatment adherent patients [1]. This can foster a sense of uncontrollability and diminish motivation for continued engagement in disease self-management. As reported in BETRHEART, stress can increase further during hospitalizations, with almost two-thirds of patients endorsing increased perceived stress during the two weeks following hospital discharge [10]. During hospitalization there is disruption in sleep and normal circadian rhythms, inactivity and general discomfort, inadequate nourishment, and altered cognitive function [56]. Over 60% of 30-day readmissions post-HF discharge are for reasons other than HF, and may in part be due to “post-hospitalization syndrome” [56,57]. The complex interaction of post-hospitalization stress with HF symptoms and the potential for further decline warrants closer examination, and could promote new approaches that proactively attempt to reduce the stressful impact when hospitalization is required.

Engaging support persons can help alleviate stress but outcomes may be affected if caregivers become over-burdened. In a study of 156 recently hospitalized HF patients and their caregivers, independent of patient distress, when caregivers reported high perceived stress and depressive symptoms, patients were at increased risk for 3-month re-admission [58]. Palliative care may also mitigate stress by helping patients with advanced HF navigate end-of-life considerations. Yet palliative care is underutilized in HF, likely due to misperceptions about the role of the service in end-stage disease, and uncertainty about when to initiate referral [59].

Social Determinants of Health and Stress

Psychological stress is ubiquitous however, certain patient groups may be disproportionately affected. Women with HF, former smokers, patients with lower income, and those with obesity report higher perceived stress, as do NYHA class II patients, compared to asymptomatic class I patients [60]. Nationwide studies have also demonstrated that social determinants of health are related to HF prevalence, with the highest rates of HF and HF-related re-admission seen in the most economically disadvantaged communities and in those with greater income inequality [61–63]. These trends may in part be explained by chronic stressors of the lived environment, as these individuals are more likely to experience violence, crime, noise, air pollution, and poverty, and less protective social capital and cohesion [47,61–63]. Repeated exposure to these stressors has the potential to complicate the clinical course by adversely affecting HF pathophysiology, or by overwhelming patient resources and consequently limiting engagement in HF self-management.

In one study, 35 low-income, urban dwelling patients with a HF re-admission were asked about their HF self-management and stressful living circumstances [47]. A discordant pattern emerged between patient narratives and endorsed stress. Patients described objectively stressful life circumstances - violence, marginal housing, unmet financial obligations, health concerns, personal loss - yet 68% had low stress scores on the PSS. This discrepancy may be the result of inadequacies in the PSS but may also be explained by psychological habituation to chronic stressors over time. In the face of unabating stress, individuals become somewhat inured to their circumstances and exhibit a diminished psychological response to repeat stress exposure. Consistent with this theory, a cross-sectional analysis found higher perceived stress among HF patients diagnosed within the last 2–5 years compared to patients with more longstanding disease [60]. HF is a progressively worsening illness and thus it is puzzling that stress would decrease as symptoms and disease-related limitations increase. It may be that patients gradually become accustomed to disease-related stress and the threshold is raised as to what is considered a significant stressor against this background. Yet, while psychologically adaptive, the process does not necessarily inhibit the physiological stress response. Thus, even if a patient reports low perceived stress, high autonomic and HPA axis activity still have the potential to adversely affect health [64].

Critical Knowledge Gaps

Pathophysiology

Research concerning the role of stress in HF has primarily relied on retrospective patient reports of stress exposures [8–10,21]. While useful for understanding patient perceptions of stress or major life events, responses may be affected by recall bias, and using only these measures is not sufficient for assessing the complexities of how stress prospectively effects HF and related disease processes over time. The effects of acute psychological stress on hemodynamic and ventricular function in HF has been studied in the laboratory setting [33,36], but this approach too, is limited; it lacks ecological validity and does not inform about the longer-term consequences of stress exposure. Improved methods are therefore needed to capture the full range of stress exposures experienced by HF patients, including whether there are different patterns of exposure and changes in the types of stressors throughout the disease trajectory, and the extent to which these aspects of the stress experience varies among specific patient sub-groups. Sophisticated ecological momentary procedures, paired with wearable or implanted cardiac monitors can be used to address these gaps [65]. By pairing patient records of daily stress on electronic diary with data from ambulatory monitors - e.g., of arterial pressure or stiffness, researchers can study patients as they navigate daily activities, and distinguish the momentary and cumulative effects of stress exposure on disease markers. This approach may also be used to discern the directionality and temporal relationship of daily reported stress to daily assessment of more proximal HF relevant indices (e.g., pulmonary artery pressure and/or fluid status [66,67]) and symptoms. A determination can be made as to whether changes in stress precede the earliest signs of HF exacerbation, or if stress is more likely to be a consequence.

HF with Preserved Ejection Fraction

Another critical knowledge gap concerns the role of stress for HF patients with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Research to date has been conducted exclusively among HF patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), or study inclusion was defined by NYHA class, with no distinction made between phenotypes in the reporting of results [5–10,21]. HFrEF and HFpEF share symptomatology and involve decrements to the pumping capacity of the left ventricle, yet differ in their risk factors, etiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and disease trajectory [68]. Thus, one cannot assume that stress exerts identical effects in both phenotypes [69].

The last decade has seen an increase in HFpEF-related research and, consequently, a greater appreciation as to the complexity of the pathophysiology. Historically defined by the presence of diastolic dysfunction, results from exercise stress testing studies led to the introduction of a field-shifting theory, that HFpEF is a multi-organ reserve dysfunction syndrome in which the body cannot adequately tolerate stress [70–72]. During exercise testing, HFpEF patients demonstrate a systemic failure of the typical autonomic response, with chronotropic incompetence, blunted ventricular contractility and relaxation, increased arterial stiffness, and endothelial dysfunction [72]. Of note, the coordinated autonomic response to psychological stress also exerts downstream effects on ventricular performance, arterial compliance, and endothelial function, and an impaired response in each of these domains has been observed in other cardiac groups [22,23,73–76]. It is possible that psychological stress may be experienced more frequently by HFpEF patients than physical stress, and unlike physical stress in which there is typically a discrete starting and stopping of demand, the boundaries of psychological stress exposures are less distinct. Many psychological stress exposures lack a clear resolution, and individuals may ruminate on stress, resulting in continued activation of the autonomic response. Thus, while psychological stress affects many of the same physiological processes key to the exercise reserve dysfunction seen in HFpEF, it is possible that this form of stress exerts a more insidious effect on HFpEF pathophysiology.

HFpEF will soon represent the most common clinical presentation of HF and there is an imminent need to fully reveal the underlying pathophysiology of the syndrome in the search for treatment targets [70,71,77]. Investigations are therefore needed to determine if psychological stress indeed evokes a multi-organ reserve dysfunction syndrome comparable to what is observed during exercise testing in HFpEF. Such investigations should be conducted under both controlled settings (e.g., inducing acute psychological stress in a laboratory with simultaneous monitoring of multiple physiological processes), and as patients navigate daily life (e.g., pairing an electronic diary of stress exposures and HF symptoms with an ambulatory monitor of arterial stiffness). These responses should also be compared to those observed with controlled and naturalistically occurring physical stress to reveal the full extent of stress-related effects.

Who Is at Risk

Moving forward it will be important to study patient-level moderators that identify who is most at risk for disease-related stress, and in whom the effects of stress are most detrimental. These investigations should focus on patient (age, sex, other psychological factors) and disease-related (HF phenotype, disease severity) factors and social determinants of health (socioeconomic status, social support, health care access, neighborhood environment). This information is readily obtained by surveying patients directly or querying electronic health records. Further, newer metrics such as the Area Deprivation Index provide a summary of neighborhood socioeconomic status disadvantage using only a patient’s address [78]. Researchers studying stress in HF are encouraged to incorporate assessment of these factors into their projects, and to report moderation effects.

Stress Management Interventions

While initial evidence suggest that stress is an important disease modifier in HF, there have been limited stress management intervention studies in this population. Only one small study with methodological limitations (see Table 3) has investigated whether a stress management intervention in HF improved patient perceptions of stress, with promising results [79]. Other trials have tested cognitive or mind-body interventions with a stress management component but studied the effects of the intervention on other outcomes, including functional status, quality of life, and depressive symptoms [80–86]. Thus, an important gap exists concerning the efficacy of stress management interventions in HF. Prior to initiating further intervention trials, additional observational and mechanistic studies in larger and more representative samples, are first needed to clarify actionable physiological and behavioral pathways and identify patients at increased risk for stress exposure and subsequent disease-related effects. This work is likely to yield important insights that can be used to formulate specific recommendations for the routine clinical assessment of stress in HF patients, and for the development and optimized targeting of, efficient interventions with the potential for improving quality of life and outcomes in HF.

Table 3.

Summary of Stress Management Intervention Studies in Heart Failure

| Study | Design and Sample | Intervention | Stress Outcome | Findings and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klaus et al., 2000 [80] | 8 NYHA III patients completed group guided imagery training | 3 weekly 90-minute trainings on using guided imagery to promote relaxation | N/A | Post-intervention improvements in physical quality of life but not HF symptoms or exercise capacity. Small sample and lack of control group limits the validity of findings. Although guided imagery is used for stress management the effects on stress were not assessed. |

| Luskin et al., 2002 [79] | 33 NYHA I-III patients randomized to group intervention or wait-list control | 8 weekly 75-minute sessions focused on ‘Freeze-Frame’ relaxation principles of stress management | Perceived Stress Scale | Post-intervention improvements in stress, functional status, and depressive symptoms. Full randomization was not achieved limiting the validity of results; no follow-up to determine if improvements were maintained. |

| Middlekauff et al., 2002 [81] | 15 NYHA II-III patients were randomized to two of three acupuncture conditions: real, non-acupoint, or non-needle | Acupuncture was performed during a laboratory procedure designed to induce acute stress | Muscle sympathetic nerve activity | Acute acupuncture (but not non-acupoint or non-needle) attenuated sympathoexcitation during mental stress. Limited generalizability; findings cannot be extrapolated to chronic acupuncture nor is there evidence of a sustained effect. |

| Chang et al., 2005 [82] | 83 NYHA II-III patients randomized to group relaxation response training, cardiac education, or usual care | 15 weekly 90-minute trainings on 8 techniques designed to promote relaxation | N/A | Post-intervention improvements in emotional quality of life but not physical quality of life or exercise capacity. While techniques were adapted from a stress reduction program, effects on stress were not directly assessed. |

| Jayadevappa et al., 2007 [83] | 23 African American NYHA II-III patients were randomized to group transcendental meditation stress reduction or health education | 1.5-hour daily trainings in a transcendental meditation over 7 consecutive days then biweekly meetings for 3 months and monthly meetings for 3 months | Cortisol | Post-intervention improvements in functional status, quality of life, and depressive symptoms and fewer re-hospitalizations in intervention group. Stress not directly assessed and no effects on cortisol; no follow-up to determine if improvements were maintained. |

| Yu et al., 2007 [84] | 121 older Chinese patients were randomized to usual care or individual progressive muscle relaxation training | 2 hour-long skills training sessions, a skills revision workshop 4 weeks later, and biweekly phone calls | N/A | Post-intervention improvements in depressive symptoms but not dyspnea or fatigue. Progressive muscle relaxation is a type of stress management training however, the effect on stress was not assessed. |

| Sullivan et al., 2009 [85] | 208 patients were assigned to group mindfulness-based stress reduction or usual care based on geographic location | 8 weekly 135-minute sessions focused on mindfulness-based stress reduction, coping skills training, and supportive group discussion | N/A | Post-intervention improvements in depression, anxiety, and HF symptoms. While the intervention is a type of stress management training, the effect on stress was not assessed. |

| Yeh et al., 2016 [86] | 100 NYHA I-III patients were randomized to group tai chi or an educational control | 1-hour tai chi classes held biweekly for 12 weeks | N/A | Qualitative interviews were completed with a random subset of participants (n=17 in intervention group). Decreased stress reactivity was among the benefits commonly reported by the intervention group however, changes in stress were not directly measured. |

NYHA = New York Heart Association; HF = heart failure

Although we do not view intervention studies as the immediate next step for advancing the science of stress in HF, thoroughly tested stress management interventions do exist and have demonstrated efficacy in other cardiac (post-myocardial infarction, MSIMI) and chronic disease (breast cancer, multiple sclerosis) populations [87–91]. For example, a 12-week cognitive-behavioral group intervention focused on reducing stressful demands and increasing coping abilities reduced stress and adverse events in cardiac rehabilitation patients and coronary artery disease outpatients [87,88]. Similarly, a 20-session group psychosocial stress reduction intervention improved survival in 237 women post-myocardial infarction, with an almost 3-fold protective effect of the intervention in the 7 years post-index event [89].

In HF, greater attention has been devoted to ameliorating depression, another psychological factor associated with increased disease burden and poor outcomes [4]. In the largest psychological intervention trial for depression in HF, depressive symptoms were reduced but patient self-care, functional status, and outcomes were not improved [92]. These findings underscore the importance of understanding the pathways through which psychological factors affect HF progression and outcomes to ensure the optimization of future interventions. By identifying the mechanisms responsible for stress effects in HF, more personalized, tailored approaches to stress management can be developed and tested.

Mobile technology and just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAI) that collect and analyze real-time data to inform the delivery of tailored interventions in moments of need, have been used to support behavior change in weight management, physical inactivity, substance use, and mental illness [93]. These technologies hold promise as an innovative delivery method for disseminating personalized stress management interventions to HF patients. This type of precision-medicine is likely to yield interventions that are brief and specific and can be delivered remotely and therefore less likely to incur additional patient burden.

It is important to note that, given the full range of stressors experienced by HF patients as discussed previously, there is a downside to focusing solely on stress management interventions that target the individual. Doing so - e.g., placing the responsibility for managing HF-related stress on the patient - implies that HF-related stress falls fully under their purview, and thereby ignores the stressors that are more systemic. For instance, much of the stress related to HF management may be due to a patient being under-resourced (e.g., lack of money to pay medical expenses, inability to take time away from caregiving responsibilities to attend appointments or cardiac rehabilitation) and this may be a function of where the patient lives (e.g., inadequate transportation, living in a food desert without access to healthy foods), factors that are arguably beyond the patient’s control. Healthcare systems however, can begin to develop and test new models of care delivery that identify and intervene on under-resourced pockets of the patient population, and measure the extent to which this approach reduces stress exposure, as part of providing comprehensive HF care. Such system-level interventions could significantly reduce the stress of HF management, and consequently, positively alter the HF disease trajectory for large numbers of patients. The sources of stress among HF patients are likely broad and diverse but to begin informing this work, we should prioritize research that advances our understanding of stress exposure specifically related to HF healthcare costs, care delivery models (e.g., frequency and format of visits [telehealth vs. in-person] and HF patient education), and hospitalizations.

Conclusions

Psychological stress has received relatively limited attention as a potential disease modifier in HF. Emerging evidence however, suggests that psychological stress can affect physiological and behavioral pathways associated with HF disease progression and prognosis, and that aspects of the HF experience can increase stress for the patient. While suggestive, there exist many knowledge gaps concerning potentially actionable pathways that must be addressed before determining the best strategies for clinical assessment and intervention. Addressing these gaps and expanding the science of stress in HF has the potential to yield important insights relevant to improving quality of life and extending longevity in this critical, increasingly prevalent population.

Acknowledgements –

Dr. Harris is funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Dr. Jacoby has received grants and other funding from Abbott, Myokardia, Pfizer, and Alnylam. Dr. Lampert has received research grants and honoraria/consulting fees from Abbott and Medtronic and is a principal investigator for studies funded by the NIH/NHLBI (R01HL125918, R01HL152548). Dr. Burg is a principal investigator for studies funded by the NIH/NHLBI (R01HL125587, R01HL126770, R01HL152548) and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Soucier has no relevant relationships to disclose.

Funding: No direct funding sources to disclose.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests: Dr. Harris is funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Dr. Jacoby has received grants and other funding from Abbott, Myokardia, Pfizer, and Alnylam. Dr. Lampert has received research grants and honoraria/consulting fees from Abbott and Medtronic and is a principal investigator for studies funded by the NIH/NHLBI (R01HL125918, R01HL152548). Dr. Burg is a principal investigator for studies funded by the NIH/NHLBI (R01HL125587, R01HL126770, R01HL152548) and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Soucier has no relevant relationships to disclose.

Ethics approval: This review manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data.

Availability of data and material: Not applicable

Code availability: Not applicable

References

- 1.Cowie MR, Anker SD, Cleland J, Felker GM, Filippatos G, Jaarsma T, Jourdain P, Knight E, Massie B, Ponikowski P, López-Sendón J. Improving care for patients with acute heart failure: Before, during, and after hospitalization. ESC Heart Fail. 2014;1:110–145. 10.1002/ehf2.12021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggarwal M, Bozkurt B, Panjrath G, Aggarwal B, Ostfeld RJ, Barnard ND, Gaggin H, Freeman AM, Allen K, Madan S, Massera D, Litwin SE, American College of Cardiology’s Nutrition and Lifestyle Committee of the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Council. Lifestyle modifications for preventing and treating heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72: 2391–2405. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu JR, Frazier SK, Rayens MK, Lennie TA, Chung ML, Moser DK. Medication adherence, social support, and event-free survival in patients with heart failure. Health Psychol. 2013; 32:637–646. 10.1037/a0028527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Celano CM, Villegas AC, Albanese AM, Gaggin HK, Huffman JC. Depression and anxiety in heart failure: A review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2018;26:175–184. 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fudim M, Cerbin LP, Devaraj S, Ajam T, Rao SV, Kamalesh M. Post-traumatic stress disorder and heart failure in men within the veteran affairs health system. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122:275–278. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aoki T, Fukumoto Y, Yasuda S, Sakata Y, Ito K, Takahashi J, Miyata S, Tsuji I, Shimokawa H. The great east Japan earthquake disaster and cardiovascular diseases. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2796–2803. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakamura M, Tanaka F, Komi R, Tanaka K, Onodera M, Kawakami M, Koeda Y, Sakai T, Tanno K, Onoda T, Matsura Y, Komatsu T, Northern Iwate Heart Registry Consortium. Sustained increase in the incidence of acute decompensated heart failure after the 2011 Japan earthquake and tsunami. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:1374–1379. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.07.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kažukauskienė N, Burkauskas J, Macijauskienė J, Mickuvienė N, Brožaitienė J. Stressful life events are associated with health-related quality of life during cardiac rehabilitation and at 2-yr follow-up in patients with heart failure. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2019;39:E5–8. 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Endrighi R, Dimond AJ, Waters AJ, Dimond CC, Harris KM, Gottlieb SS, Krantz DS. Associations of perceived stress and state anger with symptom burden and functional status in patients with heart failure. Psychol Health. 2019;34:1250–1266. 10.1080/08870446.2019.1609676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Endrighi R, Waters AJ, Gottlieb SS, Harris KM, Wawrzyniak AJ, Bekkouche NS, Li Y, Kop WJ, Krantz DS. Psychological stress and short-term hospitalisations or death in patients with heart failure. Heart. 2016;102:1820–1825. 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-309154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967;11: 213–218. 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berry C, Shalowitz M, Quinn K, Wolf R. Validation of the crisis in family systems-revised, a contemporary measure of life stressors. Psychol Rep. 2001;88:713–724. 10.2466/pr0.2001.88.3.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown GW, Harris TO. 1989. Life Events and Illness. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson B, Wethington E, Kamarck TW. Interview assessment of stressor exposure. In: Contrada RJ, Baum A, eds. The Handbook of Stress Science: Biology, Psychology, and Health. Berlin: Springer; 2010. p. 565–582. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slavich GM, Shields GS. Assessing lifetime stress exposure using the stress and adversity inventory for adults (Adult STRAIN): An overview and initial validation. Psychosom Med. 2018;80:17–27. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ewart CK, Suchday S. Discovering how urban poverty and violence affect health: development and validation of a neighborhood stress index. Health Psychol. 2002;21:254–262. 10.1037//0278-6133.21.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1576–1596. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnurr P, Vielhauer M, Weathers Findler, M The brief trauma questionnaire (BTQ) [Measurement instrument]. 1999. Available from http://www.ptsd.va.gov

- 19.Weathers FW, Blake DD, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, Marx BP, Keane TM. The life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5) – Standard. [Measurement instrument]. 2013. Available from https://www.ptsd.va.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alhurani AS, Dekker R, Tovar E, Bailey A, Lennie TA, Randall DC, Moser DK. Examination of the potential association of stress with morbidity and mortality outcomes in patient with heart failure. SAGE Open Med. 2014;2. 10.1177/2050312114552093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soufer R, Jain H, Yoon AJ. Heart-brain interactions in mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2009;11:133–140. 10.1007/s11886-009-0020-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McEwen BS. Neurobiological and systemic effects of chronic stress. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks). 2017;1. 10.1177/2470547017692328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Triposkiadis F, Karayannis G, Giamouzis G, Skoularigis J, Louridas G, Butler J. The sympathetic nervous system in heart failure physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1747–1762. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sayer G, Bhat G. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and heart failure. Cardiol Clin. 2014;32:21–32. 10.1016/j.ccl.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kudielka BM, Fischer JE, Metzenthin P, Helfricht S, Preckel D, von Känel R. No effect of 5-day treatment with acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) or the beta-blocker propranolol (Inderal) on free cortisol responses to acute psychosocial stress: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neuropsychobiology. 2007;56:159–166. 10.1159/000115783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Güder G, Bauersachs J, Frantz S, Weismann D, Allolio B, Ertl G, Angermann CE, Störk S. Complementary and incremental mortality risk prediction by cortisol and aldosterone in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;115:1754–1761. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sherwood A, Allen MT, Obrist PA, Langer AW. Evaluation of beta-adrenergic influences on cardiovascular and metabolic adjustments to physical and psychological stress. Psychophysiology. 1986;23:89–104. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1986.tb00602.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lampert R, Burg MM, Jamner LD, Dziura J, Brandt C, Li F, Donovan T, Soufer R. Effect of β-blockers on triggering of symptomatic atrial fibrillation by anger or stress. Heart Rhythm. 2019. Aug;16:1167–1173. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lampert R, Jain D, Burg MM, Batsford WP, McPherson CA. Destabilizing effects of mental stress on ventricular arrhythmias in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Circulation. 2000;101:158–164. 10.1161/01.cir.101.2.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lampert R Mental stress and ventricular arrhythmias. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18:118. 10.1007/s11886-016-0798-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santangeli P, Rame JE, Birati EY, Marchlinski FE. Management of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1842–1860. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wawrzyniak AJ, Dilsizian V, Krantz DS, Harris KM, Smith MF, Shankovich A, Whittaker KS, Rodriguez GA, Gottdiener J, Li S, Kop W, Gottlieb SS. High concordance between mental stress-induced and adenosine-induced myocardial ischemia assessed using SPECT in heart failure patients: Hemodynamic and biomarker correlates. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1527–1533. 10.2967/jnumed.115.157990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burg MM, Soufer R. Psychological stress and induced ischemic syndromes. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2014;8:377. 10.1007/s12170-014-0377-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramadan R, Quyyumi AA, Zafari M, Binongo JN, Sheps DS. Myocardial ischemia and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition: comparison of ischemia during mental and physical stress. Psychosom Med. 2013;75:815–821. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris KM, Gottdiener JS, Gottlieb SS, Burg MM, Li S, Krantz DS. Impact of mental stress and anger on indices of diastolic function in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2020: S1071–9164(20)30890–3. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2020.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson MA, Liberzon I, Lindsey ML, Lokshina Y, Risbrough VB, Sah R, Wood SK, Williamson JB, Spinale FG. Common pathways and communication between the brain and heart: Connecting post-traumatic stress disorder and heart failure. Stress. 2019;22:530–547. 10.1080/10253890.2019.1621283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinstein AA, Deuster PA, Francis JL, Bonsall RW, Tracy RP, Kop WJ. Neurohormonal and inflammatory hyper-responsiveness to acute mental stress in depression. Biol Psychol. 2010;84:228–234. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Derry HM, Fagundes CP. Inflammation: depression fans the flames and feasts on the heat. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:1075–91. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15020152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Juruena MF, Eror F, Cleare AJ, Young AH. The role of early life stress in HPA axis and anxiety. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1191:141–153. 10.1007/978-981-32-9705-0_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cavanagh L, Obasi EM. The moderating role of coping style on chronic stress exposure and cardiovascular reactivity among African American emerging adults. Prev Sci. 2020. 10.1007/s11121-020-01141-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leicht-Deobald U, Bruch H, Bönke L, Stevense A, Fan Y, Bajbouj M, Grimm S. Work-related social support modulates effects of early life stress on limbic reactivity during stress. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018;12:1405–1418. 10.1007/s11682-017-9810-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Spring Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ritchey MD, Maresh S, McNeely J, Shaffer T, Jackson SL, Keteyian SJ, Brawner CA, Whooley MA, Chang T, Stolp H, Schieb L, Wright J. Tracking cardiac rehabilitation participation and completion among Medicare beneficiaries to inform the efforts of a national initiative. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13:e005902. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rao A, Zecchin R, Newton PJ, Phillips JL, DiGiacomo M, Denniss AR, Hickman LD. The prevalence and impact of depression and anxiety in cardiac rehabilitation: A longitudinal cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020;27:478–489. 10.1177/2047487319871716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farmer SA, Magasi S, Block P, Whelen MJ, Hansen LO, Bonow RO, Schmidt P, Shah A, Grady KL. Patient, caregiver, and physician work in heart failure disease management: A qualitative study of issues that undermine wellness. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:1056–1065. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dickens C, Dickson VV, Piano MR. Perceived stress among patients with heart failure who have low socioeconomic status: A mixed-methods study. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;34:E1–8. 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sevilla-Cazes J, Ahmad FS, Bowles KH, Jaskowiak A, Gallagher T, Goldberg LR, Kangovi S, Alexander M, Riegel B, Barg FK, Kimmel SE. Heart failure home management challenges and reasons for readmission: A qualitative study to understand the patient’s perspective. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1700–1707. 10.1007/s11606-018-4542-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Piamjariyakul U, Yadrich DM, Russell C, Myer J, Prinyarux C, Vacek JL, Ellerbeck EF, Smith CE. Patients’ annual income adequacy, insurance premiums and out-of-pocket expenses related to heart failure care. Heart Lung. 2014;43(5):469–475. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DeJong C, Kazi DS, Dudley RA, Chen R, Tseng CW. Assessment of national coverage and out-of-pocket costs for sacubitril/valsartan under Medicare part D. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4: 828–830. 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tisminetzky M, Gurwitz JH, Fan D, Reynolds K, Smith DH, Magid DJ, Sung SH, Murphy TE, Goldberg RJ, Go AS. Multimorbidity burden and adverse outcomes in a community-based cohort of adults with heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:2305–2313. 10.1111/jgs.15590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cameron J, Gallagher R, Pressler SJ. Detecting and managing cognitive impairment to improve engagement in heart failure self-care. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2017;14:13–22. 10.1007/s11897-017-0317-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gaffey AE, Jeon S, Conley S, Jacoby D, Ash GI, Yaggi HK, O’Connell M, Linsky SJ, Redeker NS. Perceived stress, subjective, and objective symptoms of disturbed sleep in men and women with stable heart failure. Behav Sleep Med. 2020:1–15. 10.1080/15402002.2020.1762601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sears SF, Hauf JD, Kirian K, Hazelton G, Conti JB. Posttraumatic stress and the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator patient: What the electrophysiologist needs to know. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:242–50. 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.957670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vermeulen KM, Bosma OH, Wv Bij, GH Koëter, EM Tenvergert. Stress, psychological distress, and coping in patients on the waiting list for lung transplantation: An exploratory study. Transpl Int. 2005;18:954–959. 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00169.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome--an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:100–102. 10.1056/NEJMp1212324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1418–1428. 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schwarz KA, Elman CS. Identification of factors predictive of hospital readmissions for patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2003;32:88–99. 10.1067/mhl.2003.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kavalieratos D, Gelfman LP, Tycon LE, Riegel B, Bekelman DB, Ikejiani DZ, Goldstein N, Kimmel SE, Bakitas MA, Arnold RM. Palliative care in heart failure: Rationale, evidence, and future priorities. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1919–1930. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cirelli MA, Lacerda MS, Lopes CT, de Lima Lopes J, de Barros ALBL. Correlations between stress, anxiety and depression and sociodemographic and clinical characteristics among outpatients with heart failure. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2018;32:235–241. 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Topel ML, Kim JH, Mujahid MS, Sullivan SM, Ko YA, Vaccarino V, Quyyumi AA, Lewis TT. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and adverse outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2019;123:284–290. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kind AJ, Jencks S, Brock J, Yu M, Bartels C, Ehlenbach W, Greenberg C, Smith M. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:765–774. 10.7326/M13-2946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Rothberg MB, Avrunin J, Pekow PS, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. Income inequality and 30-day outcomes after acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2013;346:f521. 10.1136/bmj.f521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Herman JP. Neural control of chronic stress adaptation. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:61. 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goodday SM, Friend S. Unlocking stress and forecasting its consequences with digital technology. NPJ Digit Med. 2019;2:75. 10.1038/s41746-019-0151-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ollendorf DA, Sandhu AT, Pearson SD. CardioMEMS HF for the management of heart failure - effectiveness and value. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1551–1552. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamokoski LM, Haas GJ, Gans B, Abraham WT. OptiVol fluid status monitoring with an implantable cardiac device: A heart failure management system. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2007;4(6):775–780. 10.1586/17434440.4.6.775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Borlaug BA, Redfield MM. Diastolic and systolic heart failure are distinct phenotypes within the heart failure spectrum. Circulation 2011;123:2006–2013. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.954388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Harris KM, Testani JM, Burg MM. Extending behavioral medicine to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Psychosom Med. 2020;82:345–346. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pfeffer MA, Shah AM, Borlaug BA. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in perspective. Circ Res. 2019;124:1598–1617. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.313572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shah SJ, Borlaug BA, Kitzman DW, McCulloch AD, Blaxall BC, Agarwal R, Chirinos JA, Collins S, Deo RC, Gladwin MT, Granzier H, Hummel SL, Kass DA, Redfield MM, Sam F, Wang TJ, Desvigne-Nickens P, Adhikari BB. Research priorities for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: National heart, lung, and blood institute working group summary. Circulation. 2020. Mar 24;141:1001–1026. https://doi.org/0.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nayor M, Houstis NE, Namasivayam M, Rouvina J, Hardin C, Shah RV, Ho JE, Malhotra R, Lewis GD. Impaired exercise tolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Quantification of multiorgan system reserve capacity. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:605–617. 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harris KM, Gottdiener JS, Gottlieb SS, Burg MM, Li S, Krantz DS. Impact of mental stress and anger on indices of diastolic function in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2020 :S1071–9164(20)30890–3. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2020.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vlachopoulos C, Kosmopoulou F, Alexopoulos N, Ioakeimidis N, Siasos G, Stefanadis C. Acute mental stress has a prolonged unfavorable effect on arterial stiffness and wave reflections. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:231–237. 10.1097/01.psy.0000203171.33348.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hammadah M, Alkhoder A, Al Mheid I, Wilmot K, Isakadze N, Abdulhadi N, Chou D, Obideen M, O’Neal WT, Sullivan S, Tahhan AS, Kelli HM, Ramadan R, Pimple P, Sandesara P, Shah AJ, Ward L, Ko YA, Sun Y, Uphoff I, Pearce B, Garcia EV, Kutner M, Bremner JD, Esteves F, Sheps DS, Raggi P, Vaccarino V, Quyyumi AA. Hemodynamic, catecholamine, vasomotor, and vascular responses: Determinants of myocardial ischemia during mental stress. Int J Cardiol 2017; 243:47–53. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.05.093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lima BB, Hammadah M, Kim JH, Uphoff I, Shah A, Levantsevych O, Almuwaqqat Z, Moazzami K, Sullivan S, Ward L, Kutner M, Ko YA, Sheps DS, Bremner JD, Quyyumi AA, Vaccarino V. Association of transient endothelial dysfunction induced by mental stress with major adverse cardiovascular events in men and women with coronary artery disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:988–996. 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.3252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, Bluemke DA, Butler J, Fonarow GC, Ikonomidis JS, Khavjou O, Konstam MA, Maddox TM, Nichol G, Pham M, Piña IL, Trogdon KG; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Stroke Council. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):606–619. 10.1161/HHF.0b013e318291329a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kind AJH, Buckingham W. Making neighborhood disadvantage metrics accessible: The neighborhood atlas. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2456–2458. 10.1056/NEJMp1802313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Luskin F, Reitz M, Newell K, Quinn T, Haskell W. A controlled pilot study of stress management training of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. Prev Cardiol. 2002;5: 168–172. 10.1111/j.1520.037x.2002.01029.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Klaus L, Beniaminovitz A, Choi L, Greenfield F, Whitworth GC, Oz MC, Mancini DM. Pilot study of guided imagery use in patients with severe heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:101–104. 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)00838-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Middlekauff HR, Hui K, Yu JL, Hamilton MA, Fonarow GC, Moriguchi J, Maclellan WR, Hage A. Acupuncture inhibits sympathetic activation during mental stress in advanced heart failure patients. J Card Fail. 2002;8:399–406. 10.1054/jcaf.2002.129656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chang BH, Hendricks A, Zhao Y, Rothendler JA, LoCastro JS, Slawsky MT. A relaxation response randomized trial on patients with chronic heart failure. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2005;25:149–157. 10.1097/00008483-200505000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jayadevappa R, Johnson JC, Bloom BS, Nidich S, Desai S, Chhatre S, Raziano DB, Schneider R. Effectiveness of transcendental meditation on functional capacity and quality of life of African Americans with congestive heart failure: a randomized control study. Ethn Dis. 2007;17:72–77 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yu DS, Lee DT, Woo J. Effects of relaxation therapy on psychologic distress and symptom status in older Chinese patients with heart failure. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62:427–37. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sullivan MJ, Wood L, Terry J, Brantley J, Charles A, McGee V, Johnson D, Krucoff MW, Rosenberg B, Bosworth HB, Adams K, Cuffe MS. The support, education, and research in chronic heart failure study (SEARCH): A mindfulness-based psychoeducational intervention improves depression and clinical symptoms in patients with chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 2009;157:84–90. 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yeh GY, Chan CW, Wayne PM, Conboy L. The impact of tai chi exercise on self-efficacy, social support, and empowerment in heart failure: Insights from a qualitative sub-study from a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154678. 10.1371/journal.pone.0154678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Blumenthal JA, Sherwood A, Smith PJ, Watkins L, Mabe S, Kraus WE, Ingle K, Miller P, Hinderliter A. Enhancing cardiac rehabilitation with stress management training: A randomized, clinical efficacy trial. Circulation. 2016;133:1341–1350. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Blumenthal JA, Jiang W, Babyak MA, Krantz DS, Frid DJ, Coleman RE, Waugh R, Hanson M, Appelbaum M, O’Connor C, Morris JJ. Stress management and exercise training in cardiac patients with myocardial ischemia. Effects on prognosis and evaluation of mechanisms. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2213–2223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Orth-Gomér K, Schneiderman N, Wang HX, Walldin C, Blom M, Jernberg T. Stress reduction prolongs life in women with coronary disease: the Stockholm women’s intervention trial for coronary heart disease (SWITCHD). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:25–32. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.812859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stagl JM, Lechner SC, Carver CS, Bouchard LC, Gudenkauf LM, Jutagir DR, Diaz A, Yu Q, Blomberg BB, Ironson G, Glück S, Antoni MH. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral stress management in breast cancer: survival and recurrence at 11-year follow-up. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;154:319–328. 10.1007/s10549-015-3626-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Simpson R, Booth J, Lawrence M, Byrne S, Mair F, Mercer S. Mindfulness based interventions in multiple sclerosis - a systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:15. 10.1186/1471-2377-14-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Freedland KE, Carney RM, Rich MW, Steinmeyer BC, Rubin EH. Cognitive behavior therapy for depression and self-care in heart failure patients: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1773–1782. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nahum-Shani I, Smith SN, Spring BJ, Collins LM, Witkiewitz K, Tewari A, Murphy SA. Just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) in mobile health: Key components and design principles for ongoing health behavior support. Ann Behav Med. 2018;52:446–462. 10.1007/s12160-016-9830-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]