Abstract

Background:

Peripartum depression (PND) impairs mother-infant boding and perceived social support, yet limited research has examined if women at-risk for PND also experience impairment. We examined if pregnant women at-risk for PND, women with PND, and healthy comparison women (HCW) differed in their mother-infant bonding and social support. As PND is highly comorbid with anxiety, we also examined if peripartum anxiety impacted postpartum diagnosis of PND.

Methods:

144 pregnant women at-risk for PND or euthymic were assessed twice antepartum and twice postpartum. We utilized regression models to examine the impact of PND risk group status and diagnostic status on mother-infant bonding and perceived social support postpartum. We conducted a sensitivity analysis using a generalized estimating equations model to determine if anxiety (Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, HAM-A) across all four time points was associated with postpartum diagnosis of PND.

Results:

Women at-risk for PND experienced significantly worse mother-infant bonding compared to HCW (p=.03). Women diagnosed with PND experienced significantly worse mother-infant bonding and social support compared to HCW (p=.001, p=.002, respectively) and to those who were at-risk for but did not develop PND (p =.02, p =.008, respectively). HAM-A severity at each visit was associated with PND diagnosis status, where each increase in HAM-A was associated with 15% increased odds of being diagnosed with PND postpartum.

Conclusions:

Both women at-risk for PND and those with PND experience worse mother-infant bonding. Peripartum anxiety should also be assessed as it represents a marker for later PND.

Keywords: Peripartum, Postpartum, Depression, Anxiety, Mother-Infant Relationship, Social Support

1. Introduction

Major depressive disorder with peripartum onset, or peripartum (perinatal) depression (PND), is a severe and persistent form of depression. Occurring in approximately 1 in 8 women (Gavin et al., 2005), PND is a significant public health problem. The negative sequelae of PND, including pre-eclampsia (Hu et al., 2015), pre-term birth, low birth weight (Lobel et al., 2008, Hu et al., 2015), and maternal substance use (Connelly et al., 2013), exacts a substantial toll on women’s physical and mental health. In addition to its high prevalence and negative consequences, PND is commonly comorbid with anxiety, occurring together 20–60% throughout the peripartum period (Miller et al., 2015, Reck et al., 2008). This comorbidity is associated with higher symptom severity and an increased resistance to treatment (Dindo et al., 2017). Further, severe forms of PND can lead to suicidal ideation (Kingston et al., 2018) and in some cases child abuse or even infanticide (Spinelli, 2004). Tragically, maternal suicide is the leading cause of maternal mortality in the first year postpartum (Draper et al., 2018), indicating the critical and urgent need for early detection and ideally, prevention efforts.

Maternal-infant bonding provides the infant with a secure environment and fosters long-term neurological, cognitive, and social-emotional outcomes (Feldman and Eidelman, 2003, Carter and Keverne, 2002). Women suffering from PND can experience disruptions in the mother-infant relationship and can fail to accurately notice, correctly interpret, or respond sensitively to infant cues (Johnson, 2013). These infants are at greater risk for future regulation difficulties (Davis et al., 2011), which can lead to enduring behavioral and emotional problems (Johnson, 2013), such as insecure attachment and developmental delay (Barry et al., 2015, Murray et al., 2010). The impaired mother-infant relationship and children’s risk for negative outcomes can continue even after the depression has been successfully treated (Hay et al., 2001, Hay et al., 2010). Further, impaired maternal bonding may worsen postpartum depressive symptoms, creating a negative coercive cycle.

During pregnancy, depression may interfere with the normal adaptation of the maternal brain to respond accurately to infant cues, causing impairment in a woman’s ability to attend to infant distress (Pearson et al., 2011, Edhborg et al., 2011). Studies in postpartum depression have suggested that women’s negative affect after a child is born may lead to negative cognitions of typical infant behavior, unemotional interactions, and failing to respond appropriately to infant cues (Moehler et al., 2006, Nagata et al., 2003).

Similar to the negative impact PND can have on the mother-infant relationship, PND has been shown to impact women’s perception of social support. During the antepartum period, a women’s perception of social support from those around them plays an important role in their overall functioning. Perceived positive social support serves as a protective factor and is associated with decreased maternal and infant distress and reduced risk of later depression and anxiety symptoms (Schwab-Reese et al., 2017, Stapleton et al., 2012). New mothers can experience an increased need for social support during the peripartum period in order to cope with the new demands of pregnancy and motherhood (Negron et al., 2013). However, depression during this critical period can cause women to perceive low social support from those around them. In pregnancy, depression has been found to cause a strong decline in perceived emotional support from husbands and mothers-in-law (Senturk et al., 2017), with low perceived social support a significant predictor of postpartum depression (Morikawa et al., 2015). During the postpartum period women experiencing depressive symptoms have significantly lower perceptions of their partner’s social support and availability for companionship, leading to a worsening of depressive symptoms (Dennis and Ross, 2006, Brugha et al., 1998).

Currently, it is unclear if antepartum or postpartum onset PND is the more salient predictor of impaired postpartum mother-infant bonding and social support. As it is important to understand how depression impacts women’s functioning throughout the peripartum period, it is critical to know how both periods contribute to a healthy mother-infant relationship and perceived social support. Additionally, it is unknown if mother-infant bonding and social support are impaired in women at-risk for PND. A better understanding of how timing, risk, and diagnostic status impacts the mother-infant relationship and perceived social support postpartum will help guide prevention and intervention efforts.

Additionally, while there is abundant literature on individual PND risk factors, there are still considerable gaps in understanding predictive factors that lead to a diagnosis. Research has begun to examine these predictive factors in postpartum women (Dennis et al., 2004), yet limited studies have examined these factors across the peripartum period. While the rates and detrimental effects of comorbid anxiety have been well established in relation to PND, many studies examining risk for PND do not assess for anxiety symptoms (Nielsen et al., 2000), do not examine diagnostic status of depression (Verreault et al., 2014), and include only one time point (Lancaster et al., 2010),

Given these gaps in the literature, the current prospective study examined how risk status and diagnostic status were associated with mother-infant bonding and perceived social support at 2-11 weeks postpartum. We hypothesized that women who began pregnancy at-risk for PND (AR-PND), compared to healthy comparison women (HCW), would have worse mother-infant bonding and perceived social support postpartum. Additionally, we hypothesized that women who later met diagnostic criteria for PND in the postpartum would also have worse mother-infant bonding and perceived social support compared to women who never met PND diagnostic criteria. Additionally, we examined if peripartum anxiety severity, measured by the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) (Shear et al., 2001, Hamilton, 1959), predicted PND diagnosis status postpartum. We predicted that both antepartum and postpartum anxiety severity would increase a women’s risk for a PND diagnosis postpartum.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant selection

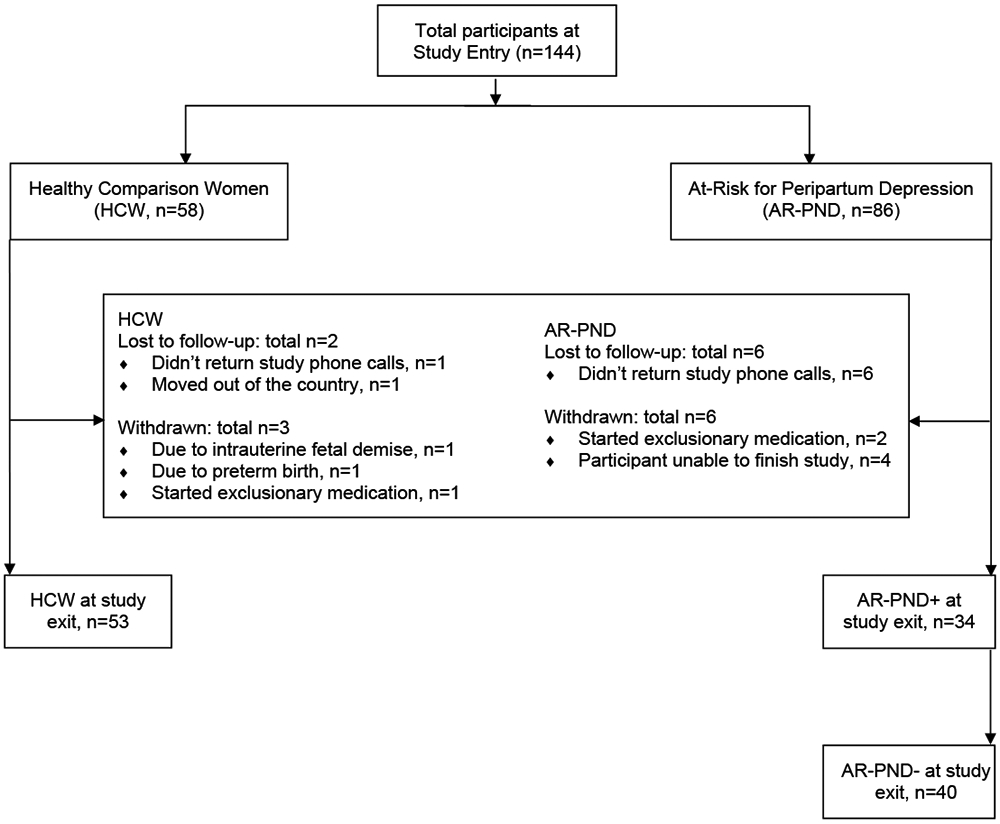

As this was a secondary data analysis on previously collected data, the sample consisted of adult peripartum women who participated in two similarly designed prospective studies (Deligiannidis et al., 2018, Deligiannidis et al., 2016a). English-speaking, pregnant women attending routine prenatal clinical care at an academic medical center were assessed for initial eligibility using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox et al., 1987); 144 eligible and interested women consented to the prospective studies. Between the studies, two groups of women were enrolled during pregnancy: (1) 58 HCW and (2) 86 AR-PND, see Figure 1. Recruitment of HCW and AR-PND groups was balanced across the studies.

FIGURE 1: Participant study completion flow diagram.

Note. PND: peripartum depression; AR-PPD−: started study AR-PND and did not develop a diagnosis of depression; AR-PND+: started study AR-PND and did develop a diagnosis of depression

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria for AR-PND:

The AR-PND group included women who had one of the following risk factors for developing a major depressive episode with peripartum onset (PND) during the prospective study: an EPDS score of ≥10 (indicating current depressive symptomatology); a history of PND or non-puerperal depression as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV TR Disorders (SCID-IV), Patient Edition (First et al., 2001); or a current antepartum diagnosis of an anxiety disorder or depressive disorder not otherwise specified (NOS). The EPDS is a common PND screening tool used in clinical settings. However, given that research has shown the EPDS is not sufficiently accurate in predicting risk of PND alone (Meijer et al., 2014), women with a history of PND or non-puerperal depression were also included (Viguera et al., 2011). Lastly, as antepartum anxiety and depression symptoms can represent an early indication of later PND, we also included women who met criteria for an anxiety disorder or depressive disorder.

2.1.2. Inclusion Criteria for HCW

HCW participants were included if they had an EPDS score ≤5 and no current or past psychiatric diagnosis or family history of psychiatric illness, as ascertained by clinical and research interviews conducted by a board-certified psychiatrist.

2.1.3. Exclusion Criteria:

Participants were excluded from both groups if they met SCID-IV criteria for a current major depressive episode (MDE), as the original studies designed to examine euthymic women and those at risk for developing a PND (Deligiannidis et al., 2018, Deligiannidis et al., 2016a). Participants were also excluded for lifetime history of hypomanic/manic episode or any psychotic disorder, elevated suicidal risk, alcohol, nicotine or substance abuse/dependence in the six months prior to study entry or use during the study. As the original studies were designed to examine neuroendocrine markers in women at risk for developing their first episode of PND, participants with multiple gestation pregnancy or pregnancy loss were excluded.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Risk-status.

We utilized the EPDS to assess initial eligibility at study entry. The EPDS is a 10-item screening questionnaire routinely used in research and clinic settings. Responses range from 0 “not at all” to 3 “yes, most of the time/as much as I always could,” with higher scores indicating more depression. Cut-off scores indicating a possible diagnosis of depression range from 9-13 (Murray and Carothers, 1990, El-Hachem et al., 2014).

2.2.2. Diagnostic Status.

The SCID-IV was administered to assess initial eligibility at study entry and to assess psychiatric diagnosis at study exit. The SCID-IV is a semi-structured interview considered the gold-standard for the assessment of DSM diagnoses. It has consistently demonstrated superior reliability and validity (Basco et al., 2000). All interviews were conducted by a board-certified psychiatrist (KMD) with expertise in the interview. For the purposes of our study, we will refer to women who started the study in pregnancy AR-PND and developed a new onset of major or minor depression, depression NOS, or an adjustment disorder with depressed mood in postpartum as AR-PND+. Women who started the study in pregnancy AR-PND but did not meet diagnostic criteria for any depression diagnosis postpartum are referred to as AR-PND−.

2.2.3. Anxiety.

The HAM-A is a semi-structured interview consisting of 14 items and was administered at all antepartum and postpartum study visits to assess anxiety severity. Each item is scored on a scale of 0 (not present) to 4 (severe), with scores <17 indicating mild severity, 18–24 mild to moderate severity, and 25–30 moderate to severe symptomology (Hamilton, 1959). The HAM-A has been shown to have good reliability and validity (Clark and Donovan, 1994).

2.2.4. Mother-infant bonding.

To assess mother-infant bonding postpartum, the Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale (MIBS) (Taylor et al., 2005) was administered to all women postpartum at study exit (visit 4). The MIBS is a self-reported questionnaire consisting of 10 items, ranging from 1 “not at all” to 3 “very much,” with higher scores indicating worse bonding. This measure has been shown to a have good reliability and construct validity across cultures (Kitamura et al., 2015, Van Bussel et al., 2010), and has been validated up to 12 weeks postpartum (Taylor et al., 2005).

2.2.5. Perceived social support.

To assess women’s perception of social support the Postpartum Social Support Questionnaire (PSSQ) (Hopkins and Campbell, 2008) was given to all women postpartum at study exit (visit 4). The PSSQ is a self-report measure consisting of 81 items, which is comprised of four subscales: Spouse's Emotional Support, Spouse's Instrumental Support, Others’ Emotional Support and Others’ Instrumental Support. In addition to assessing social support objectively, the questionnaire provides a measure of its perceived adequacy, making it one of the best scales for assessing postpartum social support than a general interpersonal support evaluation list (Heh, 2003). The PSSQ has been validate in women up to 12 months postpartum (Hopkins and Campbell, 2008). For the purposes of this study, a total score was used to assess overall perceived social support.

2.3. Study Procedures

Participants were evaluated at four study visits. The first two visits occurred antepartum: visit 1 (study entry) occurred between 21-38 weeks’ gestation and visit 2 occurred 30 – 39 weeks’ gestation. The last two visits occurred postpartum: visit 3 occurred within days after delivery and visit 4 (study exit) occurred between 2-11 weeks postpartum. At study entry, past medical history/demographics were collected. The SCID-IV was also administered at study entry and study exit to assess diagnostic status. The HAM-A was completed at all four study visits. At the final visit, subjects completed the PSSQ, and the MIBS. For visit 4, the initial study attempted to complete the final visit within 8-9 weeks postpartum, based on literature suggesting an optimal postpartum onset definition of up to 6–8 weeks of delivery as optimal (Forty et al., 2006). However, some women were difficult for the study team to reach, and participants were allowed to complete the study as able. As this was secondary data analysis, the timing of all visits were based on previous research design (Deligiannidis et al., 2016b, Deligiannidis et al., 2019). The original studies were designed to examine neuroendocrine markers in women at risk for developing their first episode of PND,

2.4. Data Analysis Plan

Study entry characteristics were compared between AR-PND vs. HCW groups using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Student’s independent samples t-test for continuous variables (with Satterthwaite adjustment for unequal variances, when appropriate). Study exit characteristics were compared between AR-PND+, AR-PND−, and HCW using chi-square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA F tests for continuous variables. We utilized regression models to examine the association between risk and diagnostic status and MIBS and PSSQ scores. Four models were run: 1) a model examining the association between antepartum risk status (AR-PND vs. HCW) and postpartum MIBS score; 2) a model examining the association between antepartum risk status (AR-PND vs. HCW) and postpartum PSSQ score; 3) a model examining differences in postpartum MIBS score with postpartum diagnostic group (AR-PND+, AR-PND−, HCW); and 4) a model examining differences in postpartum PSSQ score with postpartum diagnostic group (AR-PND+, AR-PND−, HCW). Additionally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using a generalized estimating equations (GEE) model to determine if peripartum HAM-A scores were associated with postpartum diagnosis of PND (AR-PND+ vs. AR-PND−), accounting for the correlation between participants across time. All results are reported at the critical significance level of p=0.05. Analyses were conducted in SAS v9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) with additional modeling completed in R version 3.6.0. As our sample was enrolled for previous studies, we conducted a post-hoc power calculation that >90% power with our sample size, adjusting for attrition, to identify a difference in MIBS of 1.6 points between depressed and not depressed women, with mean differences based on previous literature (O’Higgins et al., 2013).

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics

At study entry, participants age ranged from 19.4 - 40.8 years old (see Table 1 for full demographic information). Women who entered the study as AR-PND had significantly different education level and marital status compared to HCW. Study exit characteristics are presented in Table 2 across the three groups: AR-PND+, AR-PND−, and HCW. There were no significant differences across groups for gestational age, delivery method, and breastfeeding status. There were significant differences across MIBS, PSSQ, and diagnoses of depression and anxiety across groups. When examining all study visits, the HAM-A differed significantly, with AR-PND women statistically more likely to score higher than HCW on the HAM-A at every visit (p<.001 for all comparisons).

Table 1.

Population Characteristics at Study Entry in Pregnancy (n=144)

| Variablea | AR-PND (n=86) |

HCW (n=58) |

P-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 30.5 (5.2) | 29.9 (4.5) | 0.48 |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Non-White | 15 (17.4) | 18 (31.0) | 0.07 |

| White | 69 (80.2) | 39 (67.2) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 16 (18.6) | 9 (15.5) | 0.82 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 68 (79.1) | 47 (81.0) | |

| Education level, n (%) | |||

| High school diploma or less | 10 (11.6) | 5 (8.6) | 0.005 |

| Partial or completed college | 62 (72.1) | 30 (51.7) | |

| Graduate/professional degree | 13 (15.1) | 23 (39.7) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Married | 49 (57.0) | 48 (82.8) | 0.002 |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 7 (8.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Never married | 29 (33.7) | 10 (17.2) | |

| Employment status (currently employed), n (%) | 60 (69.8) | 46 (79.3) | 0.33 |

| Number of children in household | |||

| 0 | 32 (37.2) | 29 (50.0) | 0.39 |

| 1 | 39 (45.4) | 22 (37.9) | |

| 2+ | 13 (15.1) | 7 (12.1) | |

| EPDS total score, mean (SD) | 9.6 (5.2) | 2.4 (2.3) | <.0001 |

| HAM-A, mean (SD) | 15.4 (7.1) | 5.9 (5.0) | <.0001 |

| SCID Depression diagnosis, n (%) | 26 (30.2) | 0 (0.0) | <.0001 |

| Depression | 23 (26.7) | 0 (0.0) | <.0001 |

| Adjustment disorder | 3 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | <.0001 |

| SCID Anxiety diagnosis, n (%) | 50 (58.1) | 0 (0.0) | <.0001 |

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as number (percentage) of subjects. Percentages have been rounded and may not total 100.

P-values from Fisher's Exact Test for categorical variables and Student’s independent samples t-test for continuous variables (with Satterthwaite adjustment for unequal variances, when appropriate); Note: SD: Standard Deviation; AR-PPD: At-risk for postpartum depression at study entry; HCW: Healthy comparison women; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; HAM-A: Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; MIBS: Mother-Infant Bonding Scale; PSSQ: Postpartum Social Support Questionnaire; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV TR Disorders

Table 2.

Population Characteristics at Study Exit (n=127)

| Variablea | AR-PND+ (n=34) |

AR-PND− (n=40) |

HCW (n=53) |

p-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks), mean (SD) | 39.1 (1.3) | 39.3 (1.2) | 39.6 (1.0) | 0.31 |

| Delivery method, n (%) | ||||

| Vaginal | 22 (64.7) | 30 (75.0) | 41 (77.4) | 0.41 |

| Cesarean section | 10 (29.4) | 9 (22.5) | 11 (20.8) | 0.64 |

| Labor induction (yes), n (%) | 17 (50.0) | 19 (47.5) | 22 (41.5) | 0.61 |

| Breastfeeding status, n (%) | ||||

| Full or partial | 25 (73.5) | 28 (70.0) | 43 (81.1) | 0.35 |

| Bottle-feeding | 7 (20.6) | 12 (30.0) | 9 (17.0) | |

| HAM-A, mean (SD) | 18.2 (7.4) | 7.5 (5.4) | 3.7 (3.3) | <.0001 |

| MIBS, mean (SD) | 2.5 (2.2) | 1.3 (1.8) | 1.1 (1.5) | 0.002 |

| PSSQ, mean (SD) | 118.5 (25.2) | 135.6 (26.6) | 138.1 (28.4) | 0.005 |

| SCID Depression diagnosis, n (%) | 34 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | <.0001 |

| Major depression | 14 (41.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | <.0001 |

| Minor depression | 15 (44.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | <.0001 |

| Adjustment disorder | 5 (14.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.001 |

| SCID Anxiety diagnosis, n (%) | 25 (73.5) | 13 (32.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.0001 |

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as number (percentage) of subjects. Percentages have been rounded and may not total 100.

p-values from chi-square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA F tests for continuous variables.

Note: SD: Standard Deviation; AR-PPD−: started study AR-PND and did not develop a diagnosis of depression; AR-PND+ started study AR-PND and did develop a diagnosis of depression; HCW: Healthy comparison women; HAM-A: Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; MIBS: Mother-Infant Bonding Scale; PSSQ: Postpartum Social Support Questionnaire

3.2. Models examining the association between risk status and postpartum scales

3.2.1. Model 1: Association between Study Entry Risk Status (AR-PND vs. HCW) and MIBS

Women in the AR-PND group, identified at study entry, had a significantly higher postpartum MIBS scores compared to women in the HCW group, indicating worse mother-infant bonding (Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk Group Association with Postpartum MIBS and PSSQ

| Association between Study Entry Risk Status and Postpartum MIBS/PSSQ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p-value | ||

| Model 1 | Study Entry At-Risk vs. HCW on MIBS | 0.76 | 0.34 | 0.03 |

| Model 2 | Study Entry At-Risk vs. HCW on PSSQ | −8.45 | 5.18 | 0.11 |

| Risk Group Association with Postpartum MIBS | ||||

| Model 3 | AR-PND − vs. HCW | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.53 |

| AR-PND + vs. HCW | 1.42 | 0.40 | 0.001 | |

| AR-PND + vs. AR-PND − | 1.18 | 0.47 | 0.02 | |

| Risk Group Association with Postpartum PSSQ | ||||

| Model 4 | AR-PND − vs. HCW | −2.50 | 5.74 | 0.66 |

| AR-PND + vs. HCW | −19.57 | 6.14 | 0.002 | |

| AR-PND + vs. AR-PND − | −17.07 | 6.26 | 0.008 | |

Note. Higher scores on the MIBS indicate worse bonding. Lower scores on the PSSQ indicate less perceived social support. MIBS: Mother-Infant Bonding Scale; PSSQ: Postpartum Social Support Questionnaire; AR-PPD-: women who were classified at study entry as at-risk for peripartum depression, but did not meet diagnostic criteria for depression at study exit; AR-PPD+: women who were classified at study entry as at-risk for peripartum depression and did meet diagnostic criteria for depression at study exit

3.2.2. Model 2: Association between Study Entry Risk Status (AR-PND vs. HCW) and PSSQ

Women in the in the AR-PND group, identified at study entry, had lower postpartum PSSQ scores on average compared to women in the HCW group (Table 3). However, we did not find a statistically significant difference in PSSQ scores between risk groups.

3.2.3. Model 3: Association between Postpartum Diagnosis Group (AR-PND+, AR-PND−, HCW) and MIBS Postpartum

When examining the association between diagnostic group and postpartum MIBS score postpartum, we found that women in the AR-PND+ group had statistically significant higher (worse) scores compared to the HCW and the AR-PND− groups (Table 3). Compared to HCW women, AR-PND+ women scored 1.42 points higher on the MIBS, while AR-PND− women were more similar in score to the HCW group.

3.2.4. Model 4: Association between Postpartum Diagnosis Group (AR-PND+, AR-PND−, HCW) and PSSQ Postpartum

Similar to the MIBS findings, women in the AR-PND+ group had statistically significant lower (worse) PSSQ scores compared to HCW women and AR-PND− groups (Table 3). Women in the AR-PND− group did not differ statistically from HCW women.

3.2.5. Anxiety severity predicting postpartum diagnosis of PND

Finally, our GEE model indicated that HAM-A total score was associated with AR-PND+ diagnosis across time, where each increase in HAM-A total score was associated with 15% increased odds of AR-PND+ vs. AR-PND− status in the postpartum.

4. Discussion

This prospective study examined the association between risk status and diagnosis status of PND with postpartum mother-infant bonding and perceived social support. Our first aim examined how antepartum women AR-PND and HCW differed in their mother-infant bonding and perceived social support postpartum. Our results indicated that women AR-PND had significantly worse mother-infant bonding postpartum compared to HCW; however, there was no significant difference in PSSQ scores between risk groups. Our next aim was to examine how postpartum diagnostic status impacted mother-infant bonding and perceived social support postpartum. In line with our hypotheses, women in the AR-PND+ group, indicating the presence of a PND diagnosis, reported significantly worse mother-infant bonding and perceived social support, compared to women in the AR-PND− and HCW groups. Taken together, our results indicate that risk status antepartum and diagnosis status postpartum were associated with impaired mother-infant bonding postpartum. However, only women who met SCID diagnostic criteria for PND in the postpartum experienced worse perceived social support.

Results indicate that even women AR-PND at 21-38 weeks’ gestation have significantly worse mother-infant relationships at up to 11 weeks postpartum compared to their healthy counterparts. This finding highlights the critical need for antepartum assessment and risk identification. In regard to perceived social support, women identified in pregnancy with known risk factors for PND did not significantly differ from their healthy counterparts in perceived social support postpartum. Given that depression can manifest differently throughout pregnancy (Putnam et al., 2017), it may be the case that a woman’s need for social support and interpersonal relationships also change. As the demands on women significantly increase when the child is born, this may explain why women who met diagnostic criteria for PND postpartum reported significantly less perceived social support.

Our final aim was to examine how peripartum anxiety severity impacted PND diagnostic status postpartum. As there are many PND risk factors, identifying key ones that predict diagnostic status early on is critical, as they may help us to identify women with the greatest risk trajectory. Our study found that both antepartum and postpartum HAM-A severity increased a women’s chance of meeting diagnostic criteria for PND in the postpartum. As anxiety symptoms can be overlooked, our results suggest that clinicians should also assess for anxiety throughout the peripartum period. Future research should assess how specific antepartum anxiety diagnoses may influence the risk for developing PND as our study was not powered to do so.

As seen in our study, not all women who started AR-PND went on to develop a diagnosis, indicating that symptoms can develop and change across the peripartum period. Given how important prevention is, women at-risk for PND should be screened more frequently and referred quicker to mental health services for a diagnostic evaluation. Additionally, based on our findings that anxiety symptoms throughout peripartum increase the chance of a PND diagnosis, women with current symptoms or a history of anxiety should also be screened more frequently.

Together, these findings add important new data in at-risk women that can be used to shape PND preventative interventions. Peripartum anxiety severity contributes to a women’s risk of a PND diagnosis postpartum. Women diagnosed with PND are at a significantly higher risk for poor mother-infant bonding and low perceived social support when compared to women with risk factors for PND but never meet diagnostic criteria. Clinically, this points to the need for preventative interventions, as interventions delivered to women at-risk have more success in preventing postpartum depression than those delivered to women from the general population (Dennis and Dowswell, 2013). These findings support the recent United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation that at-risk women for PND, even without a diagnosis of depression, should receive treatment (e.g., cognitive behavior therapy) during pregnancy to prevent PND (O’Connor et al., 2019, Curry et al., 2019, Shorey et al., 2015). Additionally, in light of the high prevalence rates of peripartum anxiety (Fawcett et al., 2019), our results suggest that prevention efforts should also include women with peripartum anxiety.

Our study design has several strengths. First, almost all previous studies have primarily relied on the EPDS to measure depressive symptoms. While the EPDS is a quick, informative clinical screening tool for PND, the EPDS also assesses symptomatology of several other major psychiatric illnesses including anxiety, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and obsessive compulsive disorder (Lydsdottir et al., 2014). Further, the EPDS does not assess for all symptoms of depression, with some prior research solely using a variety of EPDS cut-off scores to categorize women with and without PND (O’Higgins et al., 2013, Ohoka et al., 2014).

This is one of the first studies to include a semi-structured research interview specifically for anxiety (i.e. the HAM-A) and semi-structured research diagnostic interview (i.e., SCID) in addition to the EPDS, improving research rigor. Additionally, our study included a healthy comparison group and allowed for examination of how risk status and diagnostic status impacted mother-infant boding and perceived social support.

There are several limitations to our study, including a moderate sample size and that mother-infant bonding and social support were measured by self-report rather than observational measures. It is possible that depressive or anxiety symptoms can contribute to a women’s reporting (Briggs-Gowan et al., 1996). However, it is important to note that previous research found that women’s perception of social support had a stronger relationship with depression when compared to objective measures of social support (Schaefer et al., 1981, Logsdon and McBride, 1994), indicating that women’s perception plays a vital role. Additionally, there may be potential interactions (Ohara et al., 2017) that we did not assess. As we only had MIBS and PSSQ collected at one simultaneous visit (Visit 4), we were unable to run further longitudinal models with a time-varying factor to examine the relationship between these variables. Furthermore, as depressive symptoms are associated with isolation from social support (Heh, 2003), the lack of which could worsen depressive and anxiety symptoms as the mother tries to care for her child alone, further impairing mother-infant bonding. Additionally, as social isolation is a later risk factor for postpartum depression (Nielsen et al., 2000), future research should examine these variables concurrently (both objectively and self-report) through the peripartum period to better understand their interactive effects. It is also important that future research examine maternal-infant bonding and social support within other disorders during peripartum, such as bipolar depression.

5. Conclusion

The peripartum period creates a heightened risk for the emergence of depression and anxiety, particularly in women who are already at risk. Our research indicates the importance of continued assessment as symptoms of depression can develop and change across the peripartum period. Women at-risk for peripartum depression should be screened more frequently and referred quicker to mental health services for a diagnostic evaluation. This would allow women to be identified earlier in pregnancy so that preventative efforts could be implemented before symptoms worsen. Lastly, anxiety symptoms should also be assessed frequently in all peripartum women as it represents a significant risk factor for PND.

Acknowledgments:

We thank the perinatal participants who contributed their time and data for this research study.

Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants K23MH097794, UL1TR000161, and T32DA043449. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Data Availability:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- BARRY TJ, MURRAY L, FEARON RP, MOUTSIANA C, COOPER P, GOODYER IM, HERBERT J & HALLIGAN SL 2015. Maternal postnatal depression predicts altered offspring biological stress reactivity in adulthood. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 52, 251–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BASCO MR, BOSTIC JQ, DAVIES D, RUSH AJ, WITTE B, HENDRICKSE W & BARNETT V 2000. Methods to improve diagnostic accuracy in a community mental health setting. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1599–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRIGGS-GOWAN MJ, CARTER AS & SCHWAB-STONE M 1996. Discrepancies among mother, child, and teacher reports: Examining the contributions of maternal depression and anxiety. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 24, 749–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRUGHA TS, SHARP H, COOPER S-A, WEISENDER C, BRITTO D, SHINKWIN R, SHERRIF T & KIRWAN P 1998. The Leicester 500 Project. Social support and the development of postnatal depressive symptoms, a prospective cohort survey. Psychological medicine, 28, 63–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARTER C & KEVERNE EB 2002. The neurobiology of social affiliation and pair bonding. Hormones, brain and behavior. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- CLARK DB & DONOVAN JE 1994. Reliability and validity of the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale in an adolescent sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33, 354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONNELLY CD, HAZEN AL, BAKER-ERICZÉN MJ, LANDSVERK J & HORWITZ SM 2013. Is screening for depression in the perinatal period enough? The co-occurrence of depression, substance abuse, and intimate partner violence in culturally diverse pregnant women. Journal of Women's Health, 22, 844–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COX JL, HOLDEN JM & SAGOVSKY R 1987. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British journal of psychiatry, 150, 782–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURRY SJ, KRIST AH, OWENS DK, BARRY MJ, CAUGHEY AB, DAVIDSON KW, DOUBENI CA, EPLING JW, GROSSMAN DC & KEMPER AR 2019. Interventions to prevent perinatal depression: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Jama, 321, 580–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVIS EP, GLYNN LM, WAFFARN F & SANDMAN CA 2011. Prenatal maternal stress programs infant stress regulation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 119–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DELIGIANNIDIS KM, FALES CL, KROLL-DESROSIERS AR, SHAFFER SA, VILLAMARIN V, TAN Y, HALL JE, FREDERICK BB, SIKOGLU EM & EDDEN RA 2018. Resting-state functional connectivity, cortical GABA and neuroactive steroids in peripartum and peripartum depressed women: a functional magnetic imaging and resonance study. Neuropsychopharmacology, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DELIGIANNIDIS KM, FALES CL, KROLL-DESROSIERS AR, SHAFFER SA, VILLAMARIN V, TAN Y, HALL JE, FREDERICK BB, SIKOGLU EM & EDDEN RA 2019. Resting-state functional connectivity, cortical GABA, and neuroactive steroids in peripartum and peripartum depressed women: a functional magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy study. Neuropsychopharmacology, 44, 546–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DELIGIANNIDIS KM, KROLL-DESROSIERS AR, MO S, NGUYEN HP, SVENSON A, JAITLY N, HALL JE, BARTON BA, ROTHSCHILD AJ & SHAFFER SA 2016a. Peripartum neuroactive steroid and γ-aminobutyric acid profiles in women at-risk for postpartum depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 70, 98–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DELIGIANNIDIS KM, KROLL-DESROSIERS AR, SVENSON A, JAITLY N, BARTON BA, HALL JE & ROTHSCHILD AJ 2016b. Cortisol response to the Trier Social Stress Test in pregnant women at risk for postpartum depression. Archives of women's mental health, 19, 789–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENNIS CL & DOWSWELL T 2013. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for preventing postpartum depression. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENNIS CL, JANSSEN PA & SINGER J 2004. Identifying women at-risk for postpartum depression in the immediate postpartum period. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 110, 338–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENNIS CL & ROSS L 2006. Women's perceptions of partner support and conflict in the development of postpartum depressive symptoms. Journal of advanced nursing, 56, 588–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DINDO L, ELMORE A, O’HARA M & STUART S 2017. The comorbidity of Axis I disorders in depressed pregnant women. Archives of women's mental health, 20, 757–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRAPER E, GALLIMORE I, KURINCZUK J, SMITH P, BOBY T, SMITH L & MANKTELOW B 2018. MBRRACE-UK perinatal mortality surveillance report, UK perinatal deaths for births from January to December 2016. Leicester: The Infant Mortality and Morbidity Studies, Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester. [Google Scholar]

- EDHBORG M, NASREEN H-E & KABIR ZN 2011. Impact of postpartum depressive and anxiety symptoms on mothers’ emotional tie to their infants 2–3 months postpartum: a population-based study from rural Bangladesh. Archives of women's mental health, 14, 307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EL-HACHEM C, ROHAYEM J, KHALIL RB, RICHA S, KESROUANI A, GEMAYEL R, AOUAD N, HATAB N, ZACCAK E & YAGHI N 2014. Early identification of women at risk of postpartum depression using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in a sample of Lebanese women. BMC psychiatry, 14, 242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAWCETT EJ, FAIRBROTHER N, COX ML, WHITE IR & FAWCETT JM 2019. The Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period: A Multivariate Bayesian Meta-Analysis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FELDMAN R & EIDELMAN AI 2003. Direct and indirect effects of breast milk on the neurobehavioral and cognitive development of premature infants. Developmental Psychobiology: The Journal of the International Society for Developmental Psychobiology, 43, 109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FIRST M, SPITZER R, GIBBON M & WILLIAMS J 2001. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders-patient edition (SCID-I/P). 2001. New York: Biometrics Research Department. [Google Scholar]

- FORTY L, JONES L, MACGREGOR S, CAESAR S, COOPER C, HOUGH A, DEAN L, DAVE S, FARMER A & MCGUFFIN P 2006. Familiality of postpartum depression in unipolar disorder: results of a family study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 1549–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAVIN NI, GAYNES BN, LOHR KN, MELTZER-BRODY S, GARTLEHNER G & SWINSON T 2005. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 106, 1071–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMILTON M 1959. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British journal of medical psychology, 32, 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAY DF, ASTEN P, MILLS A, KUMAR R, PAWLBY S & SHARP D 2001. Intellectual problems shown by 11-year-old children whose mothers had postnatal depression. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 42, 871–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAY DF, PAWLBY S, WATERS CS, PERRA O & SHARP D 2010. Mothers’ antenatal depression and their children’s antisocial outcomes. Child development, 81, 149–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEH SS 2003. Relationship between social support and postnatal depression. The Kaohsiung journal of medical sciences, 19, 491–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOPKINS J & CAMPBELL S 2008. Development and validation of a scale to assess social support in the postpartum period. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 11, 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HU R, LI Y, ZHANG Z & YAN W 2015. Antenatal depressive symptoms and the risk of preeclampsia or operative deliveries: a meta-analysis. PloS one, 10, e0119018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON K 2013. Maternal-Infant Bonding: A Review of Literature. International Journal of Childbirth Education, 28. [Google Scholar]

- KINGSTON D, KEHLER H, AUSTIN M-P, MUGHAL MK, WAJID A, VERMEYDEN L, BENZIES K, BROWN S, STUART S & GIALLO R 2018. Trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy and the first 12 months postpartum and child externalizing and internalizing behavior at three years. PloS one, 13, e0195365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITAMURA T, TAKEGATA M, HARUNA M, YOSHIDA K, YAMASHITA H, MURAKAMI M & GOTO Y 2015. The Mother-Infant Bonding Scale: factor structure and psychosocial correlates of parental bonding disorders in Japan. Journal of child and family studies, 24, 393–401. [Google Scholar]

- LANCASTER CA, GOLD KJ, FLYNN HA, YOO H, MARCUS SM & DAVIS MM 2010. Risk factors for depressive symptoms during pregnancy: a systematic review. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 202, 5–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOBEL M, CANNELLA DL, GRAHAM JE, DEVINCENT C, SCHNEIDER J & MEYER BA 2008. Pregnancy-specific stress, prenatal health behaviors, and birth outcomes. Health Psychology, 27, 604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOGSDON MC & MCBRIDE AB 1994. Social support and postpartum depression. Research in nursing & health, 17, 449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LYDSDOTTIR LB, HOWARD LM, OLAFSDOTTIR H, THOME M, TYRFINGSSON P & SIGURDSSON JF 2014. The mental health characteristics of pregnant women with depressive symptoms identified by the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 75, 393–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEIJER J, BEIJERS C, VAN PAMPUS M, VERBEEK T, STOLK R, MILGROM J, BOCKTING C & BURGER H 2014. Predictive accuracy of Edinburgh postnatal depression scale assessment during pregnancy for the risk of developing postpartum depressive symptoms: a prospective cohort study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 121, 1604–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER ES, HOXHA D, WISNER KL & GOSSETT DR 2015. The impact of perinatal depression on the evolution of anxiety and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Archives of women's mental health, 18, 457–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOEHLER E, BRUNNER R, WIEBEL A, RECK C & RESCH F 2006. Maternal depressive symptoms in the postnatal period are associated with long-term impairment of mother–child bonding. Archives of women's mental health, 9, 273–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORIKAWA M, OKADA T, ANDO M, ALEKSIC B, KUNIMOTO S, NAKAMURA Y, KUBOTA C, UNO Y, TAMAJI A & HAYAKAWA N 2015. Relationship between social support during pregnancy and postpartum depressive state: a prospective cohort study. Scientific reports, 5, 10520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURRAY L, ARTECHE A, FEARON P, HALLIGAN S, CROUDACE T & COOPER P 2010. The effects of maternal postnatal depression and child sex on academic performance at age 16 years: a developmental approach. Journal of child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 1150–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURRAY L & CAROTHERS AD 1990. The validation of the Edinburgh Post-natal Depression Scale on a community sample. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 288–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGATA M, NAGAI Y, SOBAJIMA H, ANDO T & HONJO S 2003. Depression in the mother and maternal attachment–results from a follow-up study at 1 year postpartum. Psychopathology, 36, 142–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEGRON R, MARTIN A, ALMOG M, BALBIERZ A & HOWELL EA 2013. Social support during the postpartum period: mothers’ views on needs, expectations, and mobilization of support. Maternal and child health journal, 17, 616–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIELSEN D, VIDEBECH P, HEDEGAARD M, DALBY J & SECHER NJ 2000. Postpartum depression: identification of women at risk. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 107, 1210–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’CONNOR E, SENGER CA, HENNINGER ML, COPPOLA E & GAYNES BN 2019. Interventions to prevent perinatal depression: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Jama, 321, 588–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’HIGGINS M, ROBERTS ISJ, GLOVER V & TAYLOR A 2013. Mother-child bonding at 1 year; associations with symptoms of postnatal depression and bonding in the first few weeks. Archives of women's mental health, 16, 381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHARA M, OKADA T, ALEKSIC B, MORIKAWA M, KUBOTA C, NAKAMURA Y, SHIINO T, YAMAUCHI A, UNO Y & MURASE S 2017. Social support helps protect against perinatal bonding failure and depression among mothers: a prospective cohort study. Scientific reports, 7, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHOKA H, KOIDE T, GOTO S, MURASE S, KANAI A, MASUDA T, ALEKSIC B, ISHIKAWA N, FURUMURA K & OZAKI N 2014. Effects of maternal depressive symptomatology during pregnancy and the postpartum period on infant–mother attachment. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 68, 631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEARSON RM, LIGHTMAN SL & EVANS J 2011. Attentional processing of infant emotion during late pregnancy and mother–infant relations after birth. Archives of women's mental health, 14, 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUTNAM KT, WILCOX M, ROBERTSON-BLACKMORE E, SHARKEY K, BERGINK V, MUNK-OLSEN T, DELIGIANNIDIS KM, PAYNE J, ALTEMUS M & NEWPORT J 2017. Clinical phenotypes of perinatal depression and time of symptom onset: analysis of data from an international consortium. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4, 477–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RECK C, STRUBEN K, BACKENSTRASS M, STEFENELLI U, REINIG K, FUCHS T, SOHN C & MUNDT C 2008. Prevalence, onset and comorbidity of postpartum anxiety and depressive disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 118, 459–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHAEFER C, COYNE JC & LAZARUS RS 1981. The health-related functions of social support. Journal of behavioral medicine, 4, 381–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHWAB-REESE LM, SCHAFER EJ & ASHIDA S 2017. Associations of social support and stress with postpartum maternal mental health symptoms: Main effects, moderation, and mediation. Women & health, 57, 723–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SENTURK V, ABAS M, DEWEY M, BERKSUN O & STEWART R 2017. Antenatal depressive symptoms as a predictor of deterioration in perceived social support across the perinatal period: a four-wave cohort study in Turkey. Psychological medicine, 47, 766–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEAR MK, VANDER BILT J, RUCCI P, ENDICOTT J, LYDIARD B, OTTO MW, POLLACK MH, CHANDLER L, WILLIAMS J & ALI A 2001. Reliability and validity of a structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A). Depression and anxiety, 13, 166–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHOREY S, CHAN SWC, CHONG YS & HE HG 2015. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of a postnatal psychoeducation programme on self-efficacy, social support and postnatal depression among primiparas. Journal of advanced nursing, 71, 1260–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPINELLI MG 2004. Maternal infanticide associated with mental illness: prevention and the promise of saved lives. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 1548–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STAPLETON LRT, SCHETTER CD, WESTLING E, RINI C, GLYNN LM, HOBEL CJ & SANDMAN CA 2012. Perceived partner support in pregnancy predicts lower maternal and infant distress. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAYLOR A, ATKINS R, KUMAR R, ADAMS D & GLOVER V 2005. A new Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale: links with early maternal mood. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 8, 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN BUSSEL JC, SPITZ B & DEMYTTENAERE K 2010. Three self-report questionnaires of the early mother-to-infant bond: reliability and validity of the Dutch version of the MPAS, PBQ and MIBS. Archives of women's mental health, 13, 373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERREAULT N, DA COSTA D, MARCHAND A, IRELAND K, DRITSA M & KHALIFÉ S 2014. Rates and risk factors associated with depressive symptoms during pregnancy and with postpartum onset. Journal of psychosomatic obstetrics & gynecology, 35, 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIGUERA AC, TONDO L, KOUKOPOULOS AE, REGINALDI D, LEPRI B & BALDESSARINI RJ 2011. Episodes of mood disorders in 2,252 pregnancies and postpartum periods. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168, 1179–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.