Abstract

We developed a Clinical Score (CS) at Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center (VICC) that we hoped would predict outcomes for patients with progressive well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) receiving therapy with Lutetium-177 (177Lu)-DOTATATE. Patients under consideration for 177Lu-DOTATATE between 3/1/2016–3/17/2020 at VICC were assigned a CS prospectively. The CS included 5 categories: available treatments for tumor type outside of 177Lu-DOTATATE, prior systemic treatments, patient symptoms, tumor burden in critical organs and presence of peritoneal carcinomatosis. The primary outcome of the analysis was progression-free survival (PFS). To evaluate the effect of the CS on PFS, a multivariable Cox regression analysis was performed adjusting for tumor grade, primary tumor location, and the interaction between 177Lu-DOTATATE doses received (zero, 1–2, 3–4) and CS. A total of 91 patients and 31 patients received 3–4 doses and zero doses of 177Lu-DOTATATE, respectively. On multivariable analysis, in patients treated with 3–4 doses of 177Lu-DOTATATE, for each 1-point increase in CS, the estimated hazard ratio (HR) for PFS was 2.0 (95% CI 1.61–2.48). On multivariable analysis, in patients who received zero doses of 177Lu-DOTATATE, for each 1-point increase in CS, the estimated HR for PFS was 1.22 (95% CI .91–1.65). Among patients treated with 3–4 doses of 177Lu-DOTATATE, those with lower CS experienced improved PFS with the treatment compared to patients with higher CS. This PFS difference, based upon CS, was not observed in patients who did not receive 177Lu-DOTATATE, suggesting the predictive utility of the score.

Keywords: peptide receptor radionuclide therapy, lutetium-177-DOTATATE, Clinical Score, patient outcomes

Introduction

Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) has been a transformative therapy for patients with progressive well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (NETs). Though PRRT has been utilized in Europe since the mid-1990’s for patients with NETs, its regulatory approvals occurred much more recently (Otte et al. 1999, Valkema et al. 2002). Lutetium-177 (177Lu)-DOTATATE was approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2017 and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2018 for patients with gastroenteropancreatic NETs with somatostatin receptor positive disease based on the NETTER-1 study and several large cohort studies from Europe (Strosberg et al. 2017, Brabander et al. 2017). Athough neither EMA nor FDA approval of 177Lu-DOTATATE has yet been granted for patients with lung NETs with somatostatin receptor positive disease, data from multiple cohorts also suggests the anti-tumor activity of the treatment in this patient group (Mariniello et al. 2016, Ianniello et al. 2016). Despite the benefit of 177Lu-DOTATATE, uncertainty exists about when to sequence the treatment for patients in relation to other available therapies. Studies comparing PRRT to everolimus or sunitinib in the post-somatostatin analog (SSA) setting are ongoing and will help to inform the optimal sequencing of PRRT in relation to these therapies for patients with well-differentiated NETs; however, these studies [NCT03049189, NCT02230176] will take several years to result and still may not define the optimal time point to administer the therapy for an individual patient. In addition to the question of when PRRT should be administered, is the question of to whom it should be administered; the therapy may be associated with unacceptable toxicity for patients with certain sites of disease involvement (e.g. peritoneal carcinomatosis, bulky mesenteric lymphadenopathy) or baseline co-morbidities (Baum et al. 2018, Merola et al. 2020). The PRRT predictive quotient (PPQ), a recently developed score comprised of NET transcript expression and tumor grade, appears promising in its ability to predict individual patient response to PRRT; the PPQ, however, does not specifically address the issues of when PRRT should be sequenced and which baseline patient characteristics may be associated with unfavorable outcomes post-PRRT (Bodei et al. 2018, Bodei et al. 2020). We believe a Clinical Score (CS), derived from readily available clinical data, which can address these issues would be an asset for physicians providing care for patients with NETs. In this article, we describe the derivation of a CS developed at Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center (VICC) and the results from the initial analysis exploring the association between CS and patient outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Population of Patients

Patients with progressive well-differentiated NETs (small intestinal, pancreatic, colon, gastric, lung, thymic and unknown primaries) under consideration for PRRT with 177Lu-DOTATATE at VICC between 3/1/2016–3/17/2020 were assigned a CS (N=122) prospectively. All patients included in the analysis demonstrated radiographic or symptomatic disease progression in the preceding 12 months prior to being considered for 177Lu-DOTATATE. The CS did not influence whether patients received treatment with PRRT or an alternative therapy. Patients who received treatment with 177Lu-DOTATATE were treated either with a dose of 7.4 or 3.7 Gigabecquerel (GBq). Patients who had previously undergone treatment with PRRT were not included in the analysis.

Data Collection

A Redcap database was designed at VICC and was used to generate a data collection instrument for the purposes of standardized data collection. A single MD investigator collected the data using this instrument (Supplemental Information). The specific data collected for each patient included the following: gender, date of birth, grade of tumor (as defined by 2019 World Health Organization Classification of NETs), Ki-67 % of tumor, primary site of disease, number of prior systemic therapies, whether prior SSA therapy had been given, whether prior chemotherapy had been given, whether primary tumor resection was performed, whether prior debulking surgery was performed, whether prior liver-directed therapy was performed, date of PRRT start, date of other treatment start (if non-PRRT), number of PRRT doses received, whether dose reductions (number of treatments or individual dose) were performed, largest volume of disease, referral reason, CS, baseline toxicities, grade of baseline toxicities, treatment-associated toxicities, grade of treatment-associated toxicities, date of treatment-associated toxicity onset, symptomatic improvement post-PRRT, post-PRRT treatment, whether an objective response was achieved post-PRRT, institution where treatment was administered, date of death, date of progression and date of last visit. For purposes of convenience, typical lung NETs were considered grade 1 tumors while atypical lung NETs were considered grade 2 tumors. Tumors which did not have grade listed on pathology reports, nor features (Ki-67 %, mitoses) which would suggest grade, were characterized as well-differentiated.

Data Analysis

A single investigator from VICC generated a CS for each patient based on the scoring system detailed below. Independent radiologists at VICC measured post-treatment response (complete response, partial response, stable disease or disease progression) for patients by RECIST 1.1 on cross-sectional imaging. Patients underwent baseline gallium-68 (68Ga)-DOTATATE positron emission tomography (PET) scans prior to PRRT to confirm adequate somatostatin receptor positivity of their tumors and post-PRRT 68Ga-DOTATATE PET scans to assess global disease status (Deppen et al. 2016, Deppen et al. 2016), however, response outcomes were assessed from computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. The radiologists at VICC had no knowledge of the CS of patients during outcome assessment.

The primary outcome of the analysis was progression-free survival (PFS), which was defined as the time from the initial 177Lu-DOTATATE or other alternate treatment dose to date of progression or death. Several secondary endpoints such as overall survival (OS), objective response rate (ORR), symptomatic benefit and development of grade 3/4 adverse events (AEs) were also assessed. OS was defined as the time between initial 177Lu-DOTATATE or other alternate treatment dose and date of death. Patients who did not experience disease progression or death were censored based upon the date of their last clinic visit. ORR was defined as the proportion of patients who achieved complete response or partial response on post-PRRT CT or MRI scans by RECIST 1.1. AEs were graded by Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 5.0 and tabulated for patients who received at least one dose of 177Lu-DOTATATE.

The CS was constructed based upon input from the multidisciplinary VICC NET tumor board, comprised of faculty experts in gastrointestinal medical oncology, thoracic medical oncology, surgical oncology, pathology, diagnostic radiology and nuclear medicine. The 5 elements of the CS included: available treatments for tumor type outside of PRRT, prior systemic treatments, disease-related symptoms, tumor burden in critical organs and the presence of peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC). Each category was scored from 0–2 except the PC category which was scored from 0–1; the total range of scores for patients ranged from 0–9 (Supplemental Information). The presence of PC was scored as a separate category from tumor bulk in critical organs given existing literature suggesting that it may independently predict poor outcomes in patients with NETs (Merola et al. 2020), and our desire to separately assess outcomes and AEs in this group of patients.

The scoring for the available treatments for tumor type outside of PRRT category was done in the following manner: patients were assigned 2 points if they possessed a thymic NET, 1 point if they possessed a non-pancreatic (small intestinal, lung, colonic, gastric, unknown origin) NET and zero points if they possessed a pancreatic NET. The rationale behind this scoring criteria is that patients with pancreatic NETs possess the greatest number of treatment options beyond PRRT, relative to patients with gastrointestinal or lung NETs. Patients with thymic NETs, on the other hand, possess the lowest number of treatment options beyond PRRT, relative to patients with gastrointestinal or lung NETs (Akirov et al. 2019). Patients with NETs of unknown primary origin typically receive similar treatments as patients with gastrointestinal NETs and thus received the same point allocation in this category. Patients were scored according to prior systemic therapies received. Patients received 2 points if they were treated with chemotherapy for an appropriate indication, 1 point if they were treated with a non-chemotherapy treatment beyond a SSA, and zero points if they had only been treated with a SSA. Patients were scored according to their disease-related symptoms prior to PRRT consideration. Patients with symptoms ≥ grade 2 received 2 points, those with grade 1 symptoms received 1 point and asymptomatic patients received zero points. Finally, patients received scores according to tumor bulk in critical organs. The determination of what constituted critical organ involvement, and how the category was scored, was done in a systematic manner. First, during a weekly VICC NET Tumor Board meeting, possible sites of metastatic or primary involvement were identified. After possibilities were identified, through a series of votes at the subsequent NET Tumor Board meeting, the sites were categorized into scores of zero, 1 and 2. Patients received a score of 2 for the following sites of involvement: cardiac, orbital, brain, hepatic (≥ 50% tumor involvement), spinal cord, ureteral with hydronephrosis, gastric outlet, encased mesenteric vessels, compressed tracheobronchial tree or pathologic bony fractures. Patients received a score of 1 for the following sites of involvement: mesenteric vessel abutment, vena cava, ≥ 5 asymptomatic bony metastases, symptomatic bone metastases (any number), hepatic (25–49% tumor involvement) or bulky hilar/mediastinal lymph nodes (> 2.5 cm in short axis) without tracheobronchial involvement (Cerfolio et al. 2008). Patients received a score of zero for any sites or degree of metastatic involvement unspecified in the prior categories.

Statistical Methodology

Patient demographics and characteristics at baseline were summarized using descriptive statistics such as medians, lower and upper quartiles for continuous variables, and frequencies and relative frequencies for categorical variables. The Wilcoxson rank-sum test and Pearson’s chi-squared test were applied when comparing a continuous variable and a categorical variable, respectively, between two groups. Survival times were estimated using Kaplan-Meier (KM) method and Log–rank test was used to compare the difference between groups. To evaluate the effect of the CS on PFS, a multivariable Cox regression with robust standard errors was performed adjusting for tumor grade (grade 2/grade 3 versus grade 1/well-differentiated), primary tumor location (small intestine, pancreas and Other) and the interaction between PRRT doses received (zero, 1–2, 3–4) and CS. To evaluate the effect of the CS on OS, a multivariable Cox regression model, adjusting only for PRRT doses received given the limited deaths in the analysis, was performed.

Results

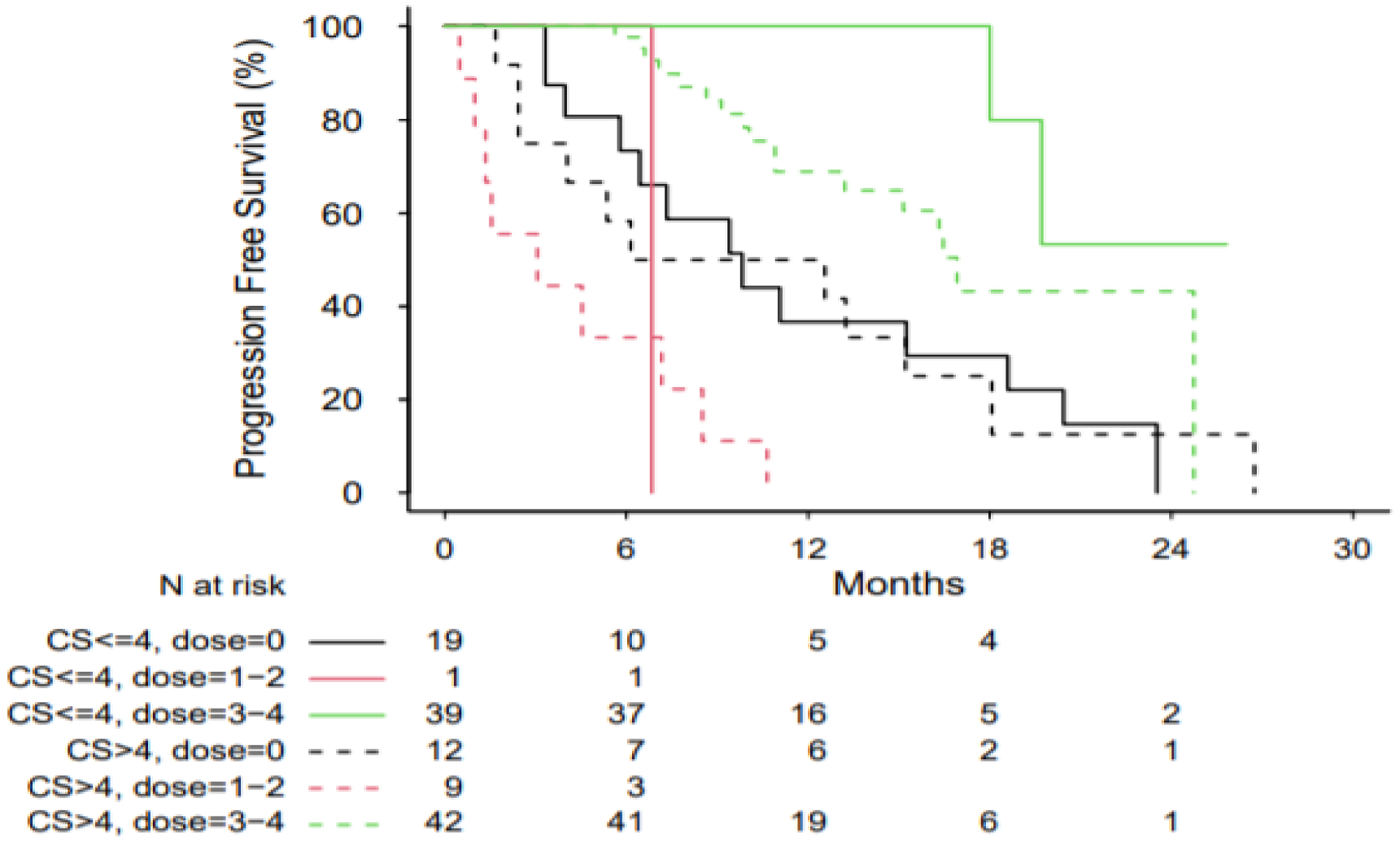

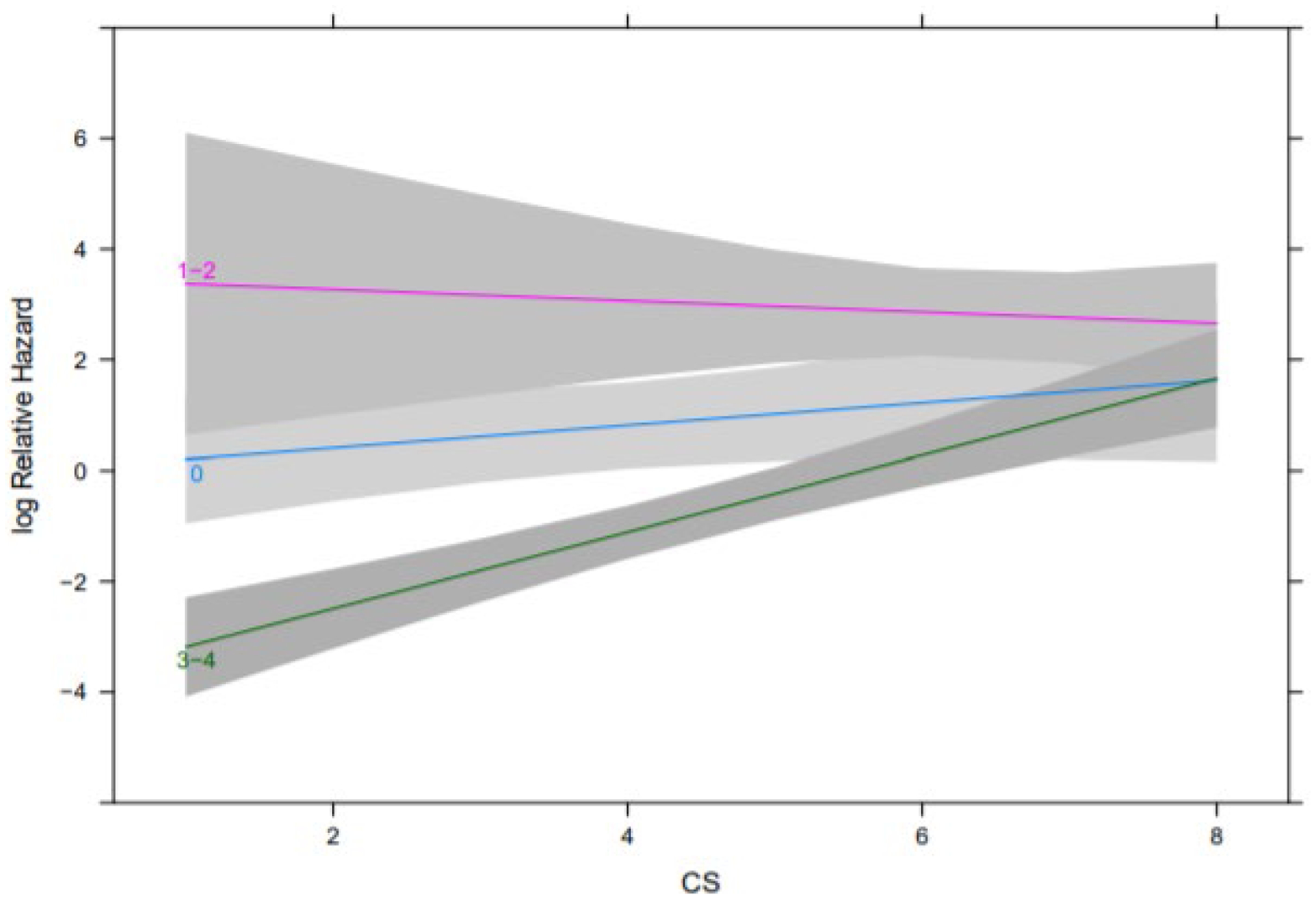

A total of 122 patients were included in the analysis. Median patient age was 61.8 years. A total of 59 patients possessed CS ≤ 4 while 63 patients possessed CS > 4. The most common primary NETs represented in the analysis originated in the small intestine (N=66), pancreas (N=33), unknown primary (N=9) and lung (N=8). Of the included patients, 65 had undergone primary tumor resection, 21 had undergone debulking surgery and 30 had undergone prior liver directed therapy; 114 patients had received prior SSA treatment while 39 patients had received prior chemotherapy. A total of 81 patients received 3–4 doses of PRRT, 31 received zero doses of PRRT and 10 received 1–2 doses of PRRT. Baseline characteristics of patients, by PRRT doses received, are detailed in Table 1. PFS was estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis. Among patients who received 3–4 doses of PRRT, patients with a CS ≤ 4 experienced a median PFS of not reached (NR) (95% CI 18 – NR) while patients with a CS > 4 experienced a median PFS of 16.92 months (95% CI 13.21 – NR). Among patients who received zero doses of PRRT, patients with a CS ≤ 4 experienced a median PFS of 9.82 months (95% CI 5.78 – 18.6) while patients with a CS > 4 experienced a median PFS of 9.35 months (95% CI 2.43 – 18.1). Among patients who received 1–2 doses of PRRT, patients with a CS ≤ 4 experienced a median PFS of 6.83 months (95% CI NR – NR) while patients with a CS > 4 experienced a median PFS of 3.06 months (95% CI .49 – 8.51) (Figure 1) (Log rank-test p < .0001). On multivariable Cox regression, adjusting for primary tumor site, tumor grade, PRRT doses received and the interaction between PRRT doses received and CS, among patients treated with 3–4 doses of PRRT, for each 1-point increase in CS, the hazard ratio (HR) for PFS was 2.0 (95% CI 1.61 – 2.48). Among patients treated with zero doses of PRRT, for each 1-point increase in CS, the HR for PFS was 1.22 (95% CI .91 – 1.65) (Figure 2) (p values for effect of tumor grade, primary tumor site and the interaction between CS and PRRT dose were .041, .021 and 0.006, respectively).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics in groups defined by PRRT doses received.

| Patient Characteristics | Zero Doses (N=31) |

1–2 Doses (N=10) |

3–4 Doses (N=81) |

Combined (N=122) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | .361 | ||||

| Male | 61% (12) | 40% (4) | 48% (39) | 51% (62) | |

| Female | 39% (19) | 60% (6) | 52% (42) | 49% (60) | |

| Age (Median) | 60.6 | 57.1 | 64.2 | 61.8 | .512 |

| WHO Grade | .191 | ||||

| G1 | 16% (5) | 30% (3) | 28% (23) | 25% (31) | |

| WD | 23% (7) | 10% (1) | 16% (13) | 17% (21) | |

| G2 | 42% (13) | 40% (4) | 51% (41) | 48% (58) | |

| G3 | 19% (6) | 20% (2) | 5% (4) | 10% (12) | |

| Primary Tumor Site | .561 | ||||

| Small Intestine | 45% (14) | 50% (5) | 58% (47) | 54% (66) | |

| Pancreas | 45% (14) | 30% (3) | 20% (16) | 27% (33) | |

| Unknown | 3% (1) | 10% (1) | 9% (7) | 7% (9) | |

| Lung | 3% (1) | 10% (1) | 7% (6) | 7% (8) | |

| Gastric | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 2% (2) | 2% (2) | |

| Colon | 3% (1) | 0% (0) | 1% (1) | 2% (2) | |

| Thymus | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 2% (2) | 2% (2) | |

| Number of Prior Systemic Therapies | .0311 | ||||

| 0 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | |

| 1 | 58% (18) | 30% (3) | 54% (44) | 53% (65) | |

| 2 | 26% (8) | 40% (4) | 25% (20) | 26% (32) | |

| 3 | 13% (4) | 0% (0) | 11% (9) | 11% (13) | |

| 4 | 3% (1) | 20% (2) | 10% (8) | 9% (11) | |

| 5 | 0% (0) | 10% (1) | 0% (0) | 1% (1) | |

| 6 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | |

| CS | .201 | ||||

| 1 | 6% (2) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 2% (2) | |

| 2 | 6% (2) | 0% (0) | 7% (6) | 7% (8) | |

| 3 | 23% (7) | 0% (0) | 14% (11) | 15% (18) | |

| 4 | 26% (8) | 10% (1) | 27% (22) | 25% (31) | |

| 5 | 26% (8) | 50% (5) | 33% (27) | 33% (40) | |

| 6 | 10% (3) | 20% (2) | 14% (11) | 13% (16) | |

| 7 | 3% (1) | 20% (2) | 4% (3) | 5% (6) | |

| 8 | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 1% (1) | 1% (1) |

Tests Used:

Pearson Test

Kruskal-Wallis Test

Abbreviations: CS, Clinical Score; WD, well-differentiated; PRRT, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS in patients, based upon CS and PRRT doses administered. Log-rank test p < 0.0001.

Abbreviations: PFS, progression-free survival; CS, Clinical Score; PRRT, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy

Figure 2.

Effects of CS by PRRT dose on PFS from the multivariable Cox regression analysis. Note, each line corresponds to a different PRRT dose group (zero, 1–2, 3–4). P values for effect of tumor grade, primary tumor site and the interaction between CS and PRRT dose were .041, .021 and 0.006 respectively.

Abbreviations: PFS, progression-free survival; CS, Clinical Score

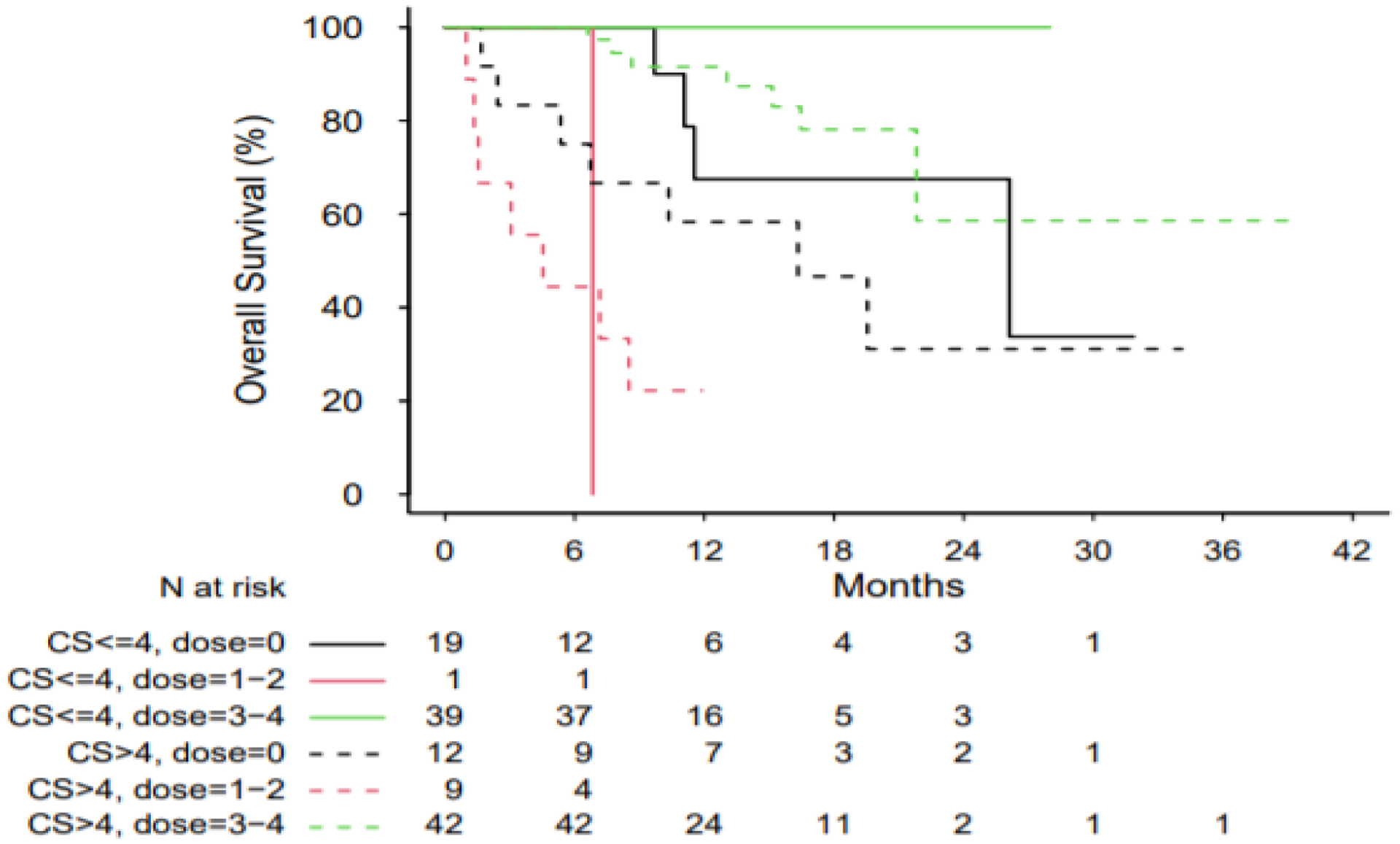

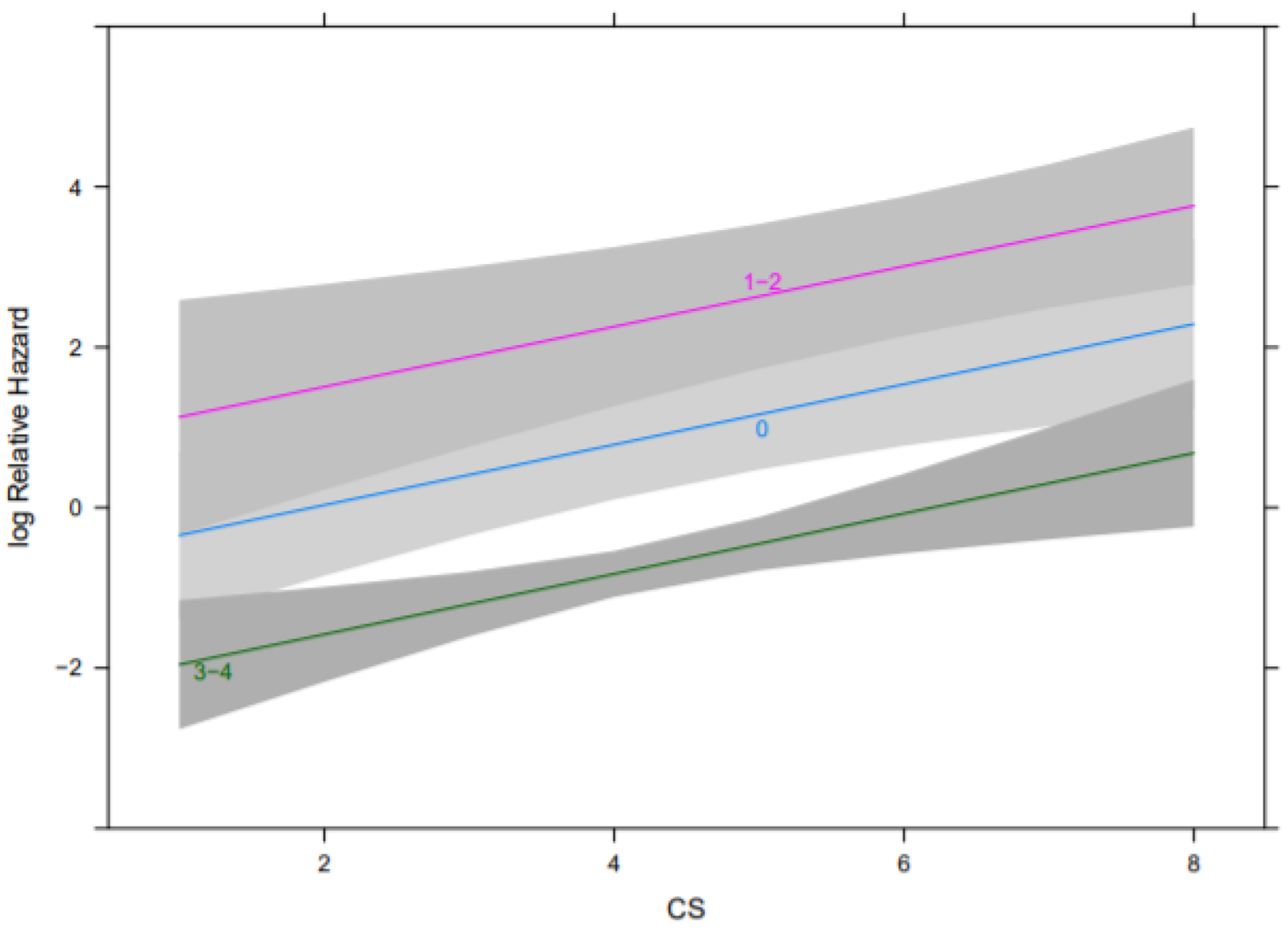

OS was also estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis. Among patients who received 3–4 doses of PRRT, patients with a CS ≤ 4 experienced a median OS of NR (95% CI NR – NR) while patients with a CS > 4 experienced a median OS of NR (95% CI 21.82 – NR). Among patients who received zero doses of PRRT, patients with a CS ≤ 4 experienced a median OS of 26.12 months (95% CI 9.69 – NR) while patients with a CS > 4 experienced a median OS of 16.33 months (95% CI 2.43 – NR). Among patients who received 1–2 doses of PRRT, patients with CS ≤ 4 experienced a median OS of 6.83 months (NR – NR) while patients with a CS > 4 experienced a median OS of 4.53 months (95% CI .99 – NR) (Figure 3) (Log-rank test p < .0001). On multivariable Cox regression, adjusting for PRRT doses administered, for each 1-point increase in CS, the HR for OS was 1.46 (95% CI 1.16 – 1.84), assuming no modification by PRRT dose (Figure 4) (p values for effect of CS and PRRT dose were 0.0015 and < .0001, respectively).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier Curves for OS in patients, based upon CS and PRRT doses administered. Log-rank test p < 0.0001.

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; CS, Clinical Score; PRRT, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy

Figure 4.

Effects of CS by PRRT dose on OS from the multivariable Cox regression analysis. Note, each line corresponds to a different PRRT dose group (zero, 1–2, 3–4). P values for effect of CS and dose were 0.0005 and < .0001 respectively.

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; CS, Clinical Score; PRRT, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy

Among the 91 patients who received PRRT, 58 patients had a total of 74 hematologic abnormalities at baseline while 29 patients had a total of 31 non-hematologic abnormalities. During treatment, 74 patients developed a total of 141 hematologic AEs while 25 patients developed a total of 28 non-hematologic AEs. The most common hematologic treatment related AEs were lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia and anemia while the most common non-hematologic treatment related AEs were transaminase elevation, bilirubin rise and creatinine rise (Table 2). With regards to grade 3/4 treatment related hematologic AEs, 14 cases of lymphopenia, 5 cases of anemia and 2 cases of thrombocytopenia were documented. With regards to grade 3/4 treatment related non-hematologic AEs, 2 cases of bilirubin elevation and 1 case of transaminase rise was documented. No differences in the development of grade 3/4 treatment related hematologic AE numbers (subject * events) (p = 1.0 by Pearson’s chi-squared test) or grade 3/4 treatment related non-hematologic AE numbers (p = .34 by Pearson’s chi-squared test) were observed between patients with CS ≤ 4 or CS > 4.

Table 2.

Treatment related adverse events for patients in the analysis.

| Adverse Event | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Total Number of Adverse Events | Total Number of Subjects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anemia | 18 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 32 | 32 |

| Bilirubin Rise | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 7 |

| Creatinine Rise | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Dermatitis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Fatigue | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Headaches | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Leukopenia | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Lymphopenia | 16 | 26 | 14 | 0 | 56 | 47 |

| Neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 34 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 48 | 42 |

| Transaminase Rise | 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 8 |

| Vasculitis | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

Among the 91 patients who received PRRT, a total of 12 patients experienced an objective response (ORR 13.1%). No difference in the proportion of patients who achieved an ORR was observed between patients with CS ≤ 4 or CS > 4 (15% versus 12%, p = .65 by the Pearson’s chi-squared test). Among the patients who received PRRT, 74 patients (67%) experienced symptomatic improvement of pretreatment disease-related symptoms. The proportion of patients with CS ≤ 4 who derived symptomatic benefit from PRRT compared to the proportion of patients with CS > 4 was markedly greater (82% versus 55%, p = .005 by the Pearson’s chi-squared test).

Finally, PRRT outcomes were reported in select prespecified patient groups, namely those with PC, liver-dominant metastatic disease and those who required dose reductions, among the patients that received 3–4 doses of 177Lu-DOTATATE. No difference in median PFS (Log-rank test p = .1) or OS (Log-rank test p = .9) was observed between patients with (N=15) and without (N=76) PC (Supplemental Figure 1). No difference in median PFS (Log-rank test p = .9) or median OS (Log-rank test p = .6) was observed between patients with liver-dominant metastatic disease or other organ-dominant metastatic disease (Supplemental Figure 2). Although no difference in median PFS (Log-rank test p = .5) was observed in patients who received 3–4 doses of PRRT, based upon whether a dose reduction was necessary, a difference in median OS (Log-rank test p = .009) was observed (Supplemental Figure 3). Median OS of patients in both these groups, however, was not reached.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the CS represents the first score derived from clinical criteria reported for patients being considered for PRRT with 177Lu-DOTATATE. Among patients who received 3–4 doses of PRRT, a striking HR for PFS (HR 2.0 for each 1-point increase) was observed as CS increased. Perhaps as importantly, the CS showed no evidence of association with PFS in patients who received an alternative treatment instead of PRRT, suggesting the predictive utility of the score for patients specifically being considered for treatment with 177Lu-DOTATATE. The patients who received an alternative treatment instead of PRRT did so for logistical reasons (namely, prolonged wait times due to limited PRRT availability) rather than due to any disease related concerns. The relevance of patients with lower CS experiencing improved PFS with PRRT directly pertains to the issue of sequencing 177Lu-DOTATATE. Until now, the therapy has been positioned in the later line setting for patients with progressive well-differentiated NETs after therapeutic options such as capecitabine plus temozolomide, sunitinib, everolimus and SSAs. Our analysis suggests that this later line setting may not be the most optimal one to utilize the therapy for patients. Ongoing studies such as COMPETE and OCCLURANDOM are testing 177Lu-based PRRT versus everolimus and sunitinib in patients with well-differentiated gastroenteropancreatic NETs and pancreatic NETs, respectively. However, they are still years away from reporting outcomes. Furthermore, even if these studies demonstrate the anticipated superiority of 177Lu-based PRRT against the comparator arms, the results still do not necessarily inform us about how early PRRT should be utilized in an individual patient. Our findings point to the advantage of using the treatment when patients have a lower disease burden in critical organs, are less pretreated and possess fewer disease-related symptoms. These findings are also consistent with the biology of 177Lu-DOTATATE as a beta-emitting particle with relatively low energy transfer compared to other radionuclides; post-hoc analysis from the NETTER-1 trial and other analyses suggest that larger tumors are less responsive to 177Lu-DOTATATE compared to smaller tumors (van Der Zwan et al. 2015, Strosberg et al. 2020, Hirmas et al. 2018). The ongoing NETTER-2 study is seeking to demonstrate proof-of-principle by testing 177Lu-DOTATATE in the first line setting for patients with well-differentiated grade 2 and grade 3 gastroenteropancreatic NETs; the study, however, is not anticipated to complete enrollment until 2026. With regard to patients with high CS, our findings do not suggest that these patients should not be treated with PRRT, but rather that they may derive less benefit from the treatment compared to patients with lower CS.

Among patients who received 3–4 doses of PRRT, a marked HR for OS (HR 1.46 for each 1-point increase) was observed as CS increased. However, this relationship was observed across patients in all PRRT dose groups (zero, 1–2 doses, 3–4 doses). The likely reasons that the CS was not uniquely predictive for OS in patients who received 3–4 doses of PRRT, was that the number of death events in the analysis (N=26) was quite small and that no patients with CS ≤ 4, who received 3–4 doses of PRRT, died. Both phenomena are a by-product of the relatively short duration of median follow up (11.8 months post-PRRT completion) for patients in the analysis.

Interestingly, patients who received 1–2 doses of PRRT were the ones who experienced the shortest PFS and OS in the analysis. Upon closer examination of the baseline characteristics of the patients in this group, this may not be so surprising. Patients in this group had the highest proportion of CS > 4 (90%), relative to patients in the other groups (39% and 52%). As such, these patients were unable to complete more than 1–2 doses of PRRT likely due to possessing the most significant organ compromise from baseline tumor burden and a lack of physiologic reserve due to debilitating disease-related symptoms.

We observed no difference in onset of grade 3/4 hematologic or grade 3/4 non-hematologic AEs post-PRRT between patients with CS ≤ 4 or > 4. This may be due to the inherently low rates of grade 3/4 toxicity elicited by PRRT with 177Lu-DOTATATE, as has been reported from large cohort studies and prospective trials (Strosberg et al. 2017, Brabander et al. 2017, Baum et al. 2018). We also observed no statistically significant difference in ORR post-PRRT in patients with CS ≤ 4 or > 4. This may have been due to limited follow up time post-PRRT for patients in the analysis. The optimal timing of response assessment post-PRRT has still not yet been established though a recent study suggests cross-sectional imaging at 9-months may be one such benchmark (Huizing et al. 2020). As such, it is possible that a significant proportion of patients in the analysis were not followed for a long enough time period to develop a response. This may also explain why the ORR of patients in the analysis (13.1%) was lower than the ORR reported in other series of patients who received treatment with 177Lu-DOTATATE (Zandee et al. 2019). Despite the lack of difference in ORR by CS, the difference in symptomatic benefit between patients with a CS ≤ 4 and CS > 4 was striking. In other reported PRRT studies, symptomatic benefit for patients has been shown to correlate with tumor response (Zandee et al. 2019).

When exploring PRRT outcomes in the previously noted prespecified patient groups, several insights emerge. Although the presence of PC has been associated with poorer outcomes with PRRT from a prior study, there was no difference in PFS or OS between patients with and without PC in our analysis. In the prior study, the rates of bowel obstruction and ascites post-PRRT were reported in 28.1% in patients with PC; this likely limited the number of PRRT doses patients received and could explain the poorer treatment outcomes which were observed. Perhaps one of the reasons we saw no difference in outcomes between patients with and without PC was our utilization of a prophylactic steroid regimen (4 milligrams of dexamethasone twice daily 3 days prior to PRRT, on day of PRRT and for 3 days post-PRRT) for these patients; none of the 15 patients with PC in our cohort experienced bowel obstructions. Given the more ready adoption of prophylactic steroids for this patient population in high volume NET centers nationally, it remains to be seen whether the presence of PC will remain a poor prognostic factor for patients undergoing PRRT. A recent study, however, suggests that prophylactic steroids do not eliminate completely the risk of bowel obstructions post-PRRT in this patient group (Strosberg et al. 2020). We did not see evidence of difference in PFS or OS between patients with liver-dominant metastatic disease or other organ-dominant metastatic disease. This was consistent with the post-hoc NETTER 1 analysis which demonstrated no difference in patient outcomes based upon extent of hepatic tumor burden (Strosberg et al. 2020). Among patients who received 3–4 doses of PRRT, patients who received full dose of 177Lu-DOTATATE experienced an improved OS compared to OS in patients who received a reduced dose. The greater benefit for patients receiving full doses of PRRT compared to reduced doses has been suggested previously (Sansovini et al. 2013). In this prior analysis, among patients with well-differentiated pancreatic NETs receiving PRRT, patients treated with full dose experienced improved PFS and ORR compared to patients treated at reduced dose. This remains a finding which needs to be tested prospectively as it could influence strategies of PRRT administration when patients experience toxicity (e.g. a longer time interval between doses versus dose reduction).

Independent of the results from the analysis, the CS represents an important scoring method to categorize patients being considered for PRRT. Some of the primary strengths of the CS include its prospective derivation, simplicity and multidisciplinary expertise behind the scoring criteria for each category. Other strengths of the score include its inclusion of factors beyond those which represent surrogates for tumor burden, such as non-PRRT treatment options available for primary tumor type and types of prior treatments received.

There are several limitations of our study. First, it is a single center analysis. VICC is a tertiary care center, however, with a referral base that spans the entire southeastern United States. As such, we believe the patient population included in the analysis is quite diverse and reflective of a real-world patient population. Second, the study findings have yet to be validated. We are pursuing this validation effort currently with collaborators at 3 additional institutions. Third, though the CS was derived in a multidisciplinary manner, it is possible other factors influencing PRRT tolerability and response, such as tumor somatostatin receptor expression homogeneity and patient renal function and bone marrow reserve, were not included in its categories. The exclusion of these factors appears to be less relevant given that all included patients had to be deemed eligible for PRRT based upon multidisciplinary tumor board evaluation at VICC. Some of the standard inclusion criteria for patients being considered for PRRT with 177Lu-DOTATATE are homogeneous somatostatin receptor expression within tumors and adequate hematologic function, liver function (including synthetic function) and kidney function (Hope et al. 2020, Kwekkeboom et al. 2009). Fourth, the patients in our analysis had limited follow up time post-PRRT and as such, there were very few death events. This limited our ability to demonstrate the predictive association of CS with OS, specifically in patients who received 3–4 doses of PRRT. However, PFS may be a purer evaluation of effect of PRRT as there are a growing number of available options for patients with NETs. Fifth, the number of patients in the non-PRRT treated cohort was quite small, relative to the number of patients who received PRRT. It is possible that a larger number of patients in this cohort would have produced different results. This is less likely given the absence of association (near flat-line on Figure 2) between increasing CS and PFS in the multivariable analysis for patients who received zero doses of PRRT, and the similar patient characteristics between patients who received zero doses of PRRT and those who received 3–4 doses of PRRT. Sixth, the predictive ability of the CS only pertains to patients receiving PRRT with 177Lu-DOTATATE. We do not know whether the CS applies to patients receiving PRRT with other available radionuclides such as Yttrium-90 (90Y) or novel radionuclides such as 212-Pb (212Pb)-DOTAMTATE and 177Lu satoreotide tetraxetan. Preclinical data suggests alpha emitters such as 212Pb and somatostatin antagonists such as satoreotide tetraxetan induce a greater number of double strand DNA breaks in NET models compared to 177Lu-DOTATATE (Dalm et al. 2016, Stallons et al. 2019). Early clinical data also suggests that extent of tumor burden in patients may perhaps be a less relevant factor influencing tumor response to these radionuclides (Reidy-Lagunes et al. 2019, Ballal et al. 2019).

Conclusions

We present the development and performance of a CS for patients with progressive well-differentiated NETs being considered for PRRT with 177Lu-DOTATATE. Beyond the simplicity of the CS and its prospective derivation, to the best of our knowledge, it represents the first published clinically-derived score offering guidance on how to classify patients being considered for the treatment. Our findings suggest that the CS is predictive for PFS in patients undergoing treatment with 177Lu-DOTATATE. This is particularly impactful as our results suggest that patients with well-differentiated NETs with low CS who are candidates for 177Lu-DOTATATE should perhaps be preferentially treated with PRRT rather than with other available treatment options after progression on SSAs. With regards to patients with well-differentiated NETs with high CS, our data does not suggest that these patients not be treated with PRRT, but rather that they may derive less benefit. The question of when to sequence 177Lu-DOTATATE among other treatments is a significant one given the competing forces of long-term patient PFS and OS benefit from PRRT and possible harm from the long-term AEs from PRRT (e.g. myelodysplastic syndrome, acute myeloid leukemia). Previously, many NET specialists were inclined to delay 177Lu-DOTATATE into a later-line setting for patients to mitigate the possible development of some of these AEs. We believe the findings presented support the opposite notion and point towards utilizing 177Lu-DOTATATE in the earlier treatment setting for patients. The definitive studies which will inform the optimal timing of 177Lu-DOTATATE (e.g. NETTER2, COMPETE, OCCLURANDOM) are still years away from reporting results, and until then, we may have rely upon findings from cohort studies such as the one presented to infer decision making about treatment sequencing for patients with well-differentiated NETs.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by Dr. Das’s funding from the 5 K12 CA90625-19 grant and the Neuroendocrine Tumor Research Foundation Investigator Award.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

None of the authors declare a conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Ethics Approval

Prior to data collection, the research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of VUMC. The VUMC Institutional Review Board deemed that informed consent from patients was not needed and an exemption for this research was granted.

Informed Consent

As noted above, this research was deemed exempt from requiring informed consent from the patients whose data was included in the analysis.

Availability of Data and Material

All data (including raw data and CS scoring criteria) are included in the supplemental portion of the submission.

References

- Akirov A, Larouche V, Alshehri S, Asa S & Ezzat S 2019. Treatment Options for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancers (Basel) 11 E828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballal S, Yadav M, Bal C, Sahoo R & Tripathi M 2019. Broadening horizons with 225Ac-DOTATATE targeted alpha therapy for gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumour patients stable or refractory to 177Lu-DOTATATE PRRT: first clinical experience on the efficacy and safety. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 47 943–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum R, Kulkarni H, Singh A, Kaemmerer D, Mueller D, Prasad V, Homman M, Robiller F, Niepsch K, Franz H et al. 2018. Results and adverse events of personalized peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with 90Yttrium and 177Lutetium in 1048 patients with neuroendocrine neoplasms. Oncotarget 9 16932–16950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodei L, Kidd M, Singh A, van der Zwan W, Severi S, Drozdov I, Cwikla J, Baum R, Kwekkeboom D, Paganelli G et al. 2018. PRRT genomic signature in blood for prediction of 177Lu-octreotate efficacy. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecuar Imaging 45 1155–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodei L, Kidd M, Singh A, Drozdov I, Malczewska A, Baum R, Krenning E & Modlin I 2020. The utility of blood-based molecular tools-the NETest-to monitor and evaluate the efficacy of PRRT in neuroendocrine tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 38 3568–3568. [Google Scholar]

- Brabander T, van der Zwan W, Teunissen J, Kam B, Feelders R, de Herder W, van Eijck C, Franssen G, Krenning E & Kwekkeboom D 2017. Long-term efficacy, survival, and safety of [(177)Lu-DOTA(0),Tyr(3)]octreotate in patients with gastroenteropancreatic and bronchial neuroendocrine tumors. Clinical Cancer Research 23 4617–4624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerfolio R, Maniscalco L & Bryant A 2008. The Treatment of Patients with Stage IIIA Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer From N2 Disease: Who Returns to the Surgical Arena and Who Survives. Annals of Thoracic Surgery 86 912–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalm S, Nonnekens J, Doeswijk G, de Blois E, van Gent D, Konijenberg M & de Jong M 2016. Comparison of the Therapeutic Response to Treatment with a 177Lu-Labeled Somatostatin Receptor Agonist and Antagonist in Preclinical Models. The Journal of Nuclear Medicine 57 260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deppen S, Liu E, Blume J, Clanton J, Shi C, Jones-Jackson L, Lakhani V, Baum R, Berlin J & Smith G 2016. Safety and Efficacy of 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT for Diagnosis, Staging and Treatment Management of Neuroendocrine Tumors. he Journal of Nuclear Medicine 57 708–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deppen S, Blume J, Bobbey A, Shah C, Graham M, Lee P, Delbeke D & Walker R 2016. 68Ga-DOTATATE compared to 111In-DTPA- octreotide and conventional imaging for pulmonary and gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Nuclear Medicine 57 872–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirmas N, Jadaan R & Al-Ibraheem A 2018. Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy and the Treatment of Gastroentero-pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Current Findings and Future Perspectives. Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 52 190–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope T, Bodei L, Chan J, El-Haddad G, Fieldman N, Kunz P, Mailman J, Menda Y, Metz D & Mittra E 2020. NANETS/SNMMI Consensus Statement on Patient Selection and Appropriate Use of 177 Lu-DOTATATE Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy. The Journal of Nuclear Medicine 61 222–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizing D, Aalbersberg E, Versleijen M, Tesselaar M, Walraven I, Lahaye M, de Wit-van der Veen & Stokkel M 2020. Early response assessment and prediction of overall survival after peptide receptor radionuclide therapy. Cancer Imaging 20 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ianniello A, Sansovini M, Severi S, Nicolini S, Grana C, Massri K, Bongiovanni A, Antonuzzo L, Di lorio V, Sarnelli A et al. 2016. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with (177)Lu-DOTATATE in advanced bronchial carcinoids: prognostic role of thyroid transcription factor 1 and (18)F-FDG PET. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 43 1040–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwekkeboom D, Krenning E, Lebtahi R, Komminoth P, Kos-Kudla B, de Werder W & Plockinger U 2009. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the Standards of Care in Neuroendocrine Tumors: peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with radiolabeled somatostatin analogs. Neuroendocrinology 90 220–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariniello A, Bodei L, Tinelli C, Baio S, Gilardi L, Colandrea M, Papi S, Valmadre G, Fazio N & Galetta D 2016. Long-term results of PRRT in advanced bronchopulmonary carcinoid. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 43 441–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merola E, Prasad V, Pascher A, Pape U, Arsenic R, Denecke T, Fehrenbach U, Wiedenmann B & Pavel M 2020. Peritoneal Carcinomatosis in Gastro-Entero-Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: Clinical Impact and Effectiveness of the Available Therapeutic Options. Neuroendocrinology 110 517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otte A, Herrmann R, Heppeler A, Behe M, Jermann E, Powell P, Maecke H & Muller J 1999. Yttrium-90 DOTATOC: first clinical results. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 26 1439–1447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy-Lagunes D, Pandit-Taskar N, O’Donoghue J, Krebs S, Staton K, Lyashchenko S, Lewis J, Raj N, Gonen M & Lohrmann C 2019. Phase I Trial of Well-Differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumors (NETs) with Radiolabeled Somatostatin Antagonist 177Lu-Satoreotide Tetraxetan. Clinical Cancer Research 25 6939–6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansovini M, Severi S, Ambrosetti A, Monti M, Nanni O, Sarnelli A, Bodei L, Garaboldi L, Bartolomei M & Paganelli G 2013. Treatment with the Radiolabelled Somatostatin Analog 177Lu-DOTATATE for Advanced Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology 97 347–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallons T, Saidi A, Tworowska I, Delpassand E & Torgue J 2019. Preclinical Investigation of 212 Pb-DOTAMTATE for Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy in a Neuroendocrine Tumor Model. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 18 1012–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strosberg J, El-Haddad G, Wolin E, Hendifar A, Yao J, Chasen B, Mittra E, Kunz P, Kulke M, Jacene H et al. 2017. Phase 3 trial of 177Lu-dotatate for midgut neuroendocrine tumors. The New England Journal of Medicine 376 125–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strosberg J, Kunz P, Hendifar A, Yao J, Bushnell D, Kulke M, Baum R, Caplin M, Ruszniewski P, Delpassand E et al. 2020. Impact of liver tumour burden, alkaline phosphatase elevation, and target lesion size on treatment outcomes with 177 Lu-Dotatate: an analysis of the NETTER-1 study. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 47 2372–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strosberg J, Al-Toubah T, Pelle E, Smith J, Haider M, Hutchinson T, Fleming J & El-Haddad G 2020. Risk of bowel obstruction in patients with mesenteric/peritoneal disease receiving peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT). The Journal of Nuclear Medicine (no volume or page number provided). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkema R, De Jong M, Bakker W, Breeman W, Kooij P, Lugtenberg P, De Jong F, Christiansen A, Kam B, De Herder W et al. 2002. Phase I study of peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with [In-DTPA]octreotide: the Rotterdam experience. Seminars in Nuclear Medicine 32 110–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zwan W, Bodei L, Mueller-Brand J, de Herder W, Kvols L & Kwekkeboom D 2015. GEPNETs update: radionuclide therapy in neuroendocrine tumors. European Journal of Endocrinology 172 R1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandee W, Brabander T, Blazevic A, Kam B, Teunissen J, Feelders R, Hofland J & de Herder W 2019. Symptomatic and Radiological Response to 177Lu-DOTATATE for the Treatment of Functioning Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 104 1336–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.