Abstract

Proteotoxic stress is a common challenge for all organisms. Among various mechanisms involved in defending such stress, the evolutionarily conserved unfolded protein responses (UPRs) play a key role across species. Interestingly, UPRs can occur in different subcellular compartments including the endoplasmic reticulum (UPRER), mitochondria (UPRMITO), and cytoplasm (UPRCYTO) through distinct mechanisms. While previous studies have shown that the UPRs are intuitively linked to organismal aging, a systematic assay on the temporal regulation of different type of UPRs during aging is still lacking. Here, using Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) as the model system, we found that the endogenous UPRs (UPRER, UPRMITO, and UPRCYTO) elevate with age, but their inducibility exhibits an age-dependent decline. Moreover, we revealed that the temporal requirements to induce different types of UPRs are distinct. Namely, while the UPRMITO can only be induced during the larval stage, the UPRER can be induced until early adulthood and the inducibility of UPRCYTO is well maintained until mid-late stage of life. Furthermore, we showed that different tissues may exhibit distinct temporal profiles of UPR inducibility during aging. Collectively, our findings demonstrate that UPRs of different subcellular compartments may have distinct temporal mechanisms during aging.

Keywords: aging, cytosolic UPR, endoplasmic reticulum UPR, mitochondrial UPR, stress, temporal

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The unfolded protein responses (UPRs) play an essential role in controlling various physiological processes ranging from maintaining the cellular proteostasis network, calcium homeostasis, redox homeostasis, to bioenergetic function (Richter et al., 2010; Ruan et al., 2020; Walter & Ron, 2011). As evolutionarily conserved cellular stress responses, UPRs are activated by the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in cells. Under diverse stress conditions, organelle-specific UPRs could occur in response to the imbalances between local protein biosynthesis, loading, and folding, and these UPRs can be referred to as the UPRER, UPRMITO, and UPRCYTO (also called the heat shock response, or HSR). The UPRER is mainly regulated by three separate cis-acting response elements (i.e., XBP1, ATF6, and ATF4), and the protein folding environment inside the ER is sensed by the ER-resident membrane proteins IRE1, ATF6, and PERK, respectively (Walter & Ron, 2011). The UPRMITO can be induced by various cellular stressors that cause impaired mitochondrial function, and it is mediated by the bZIP transcription factors ATF5, ATF4 and CHOP in mammals which correspond to ATFS-1 in Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans; Higuchi-Sanabria et al., 2018; Naresh & Haynes, 2019; Ruan et al., 2020). By contrast, the UPRCYTO is primarily regulated by the heat shock transcription factors (HSFs), which can induce the expression of multiple chaperon proteins including Hsp70, Hsp90, and a subset of the J-domain chaperon proteins (Joutsen & Sistonen, 2019).

Intriguingly, advanced ages are commonly accompanied with compromised UPRs (Higuchi-Sanabria et al., 2018; Labbadia & Morimoto, 2015). Moreover, many aging-related disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease are associated with the protein aggregation-induced proteotoxicity, where age-related decline in the UPRs may play an important role (Knowles et al., 2014; Labbadia & Morimoto, 2015). On the other hand, the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins presents a major challenge to the proteostasis network, which in turn may accelerate aging. Indeed, genetic studies in C. elegans have shown that enhanced UPRER, UPRMITO, or UPRCYTO can each lead to lifespan extension under certain circumstances (Durieux et al., 2011; Morley & Morimoto, 2004; Taylor & Dillin, 2013). Therefore, the UPRs seem to be intuitively linked to organismal aging.

While proteotoxic stress could impose a constant threat throughout the lifespan of an organism, surprisingly, the induction of UPRs may have specific temporal requirements. For example, in C. elegans both the induction of UPRMITO and the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC)-mediated lifespan regulation mainly occur during the L3/L4 stages of larval development (Dillin et al., 2002; Durieux et al., 2011). Nonetheless, a systematic survey on the temporal requirement of the induction of different types of UPRs is still lacking. In addition, the age-related changes in endogenous UPRs are unclear.

In this study, we used the well-established model organism C. elegans to investigate the temporal actions of different type of UPRs (i.e., UPRER, UPRMITO, and UPRCYTO) during aging. Our results demonstrated that although the endogenous UPRs elevate with age, their inducibility exhibits an age-related decline. Furthermore, we revealed that the temporal requirements to induce different types of UPRs are distinct in C. elegans and different tissues may exhibit distinct temporal profiles of UPR inducibility during aging.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Strains

C. elegans strains N2 Bristol, zcls13[hsp-6p∷GFP], zcls4[hsp-4p∷GFP], gpIs1 [hsp-16.2p∷GFP] were all obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (University of Minnesota). If not specified, all worms were grown and maintained on nematode growth media (NGM) agar plates at 20°C as previously described (Brenner, 1974).

2.2 |. RNA interference (RNAi) feeding assay

Standard RNAi feeding assays were performed as described before (Xiao et al., 2013, 2015), and worms were subjected to RNAi bacteria from different life stages as indicated in figures. Escherichia coli HT115 (DE3) transformed with the empty vector L4440 was used as control for all RNAi feeding experiments. RNAi clones against gas-1 (a complex I component), mev-1 (a complex II component), cox-7C (a complex IV component), spg-7 (a putative metalloprotease), daf-2 (the C. elegans insulin receptor), and daf-16 (the C. elegans FOXO transcription factor downstream of insulin/IGF-1 signaling [IIS] pathway) were derived from the Ahringer RNAi library, and the isp-1 (a complex III component) RNAi clone was generated by ourselves using primers isp-1 forward: CACTGGACGGTGTCGAAATG and isp-1 reverse: CTAATACGTCCAGAAGCGTCG (1024 base pair PCR product). All RNAi clones were sequence verified using Sanger sequencing.

2.3 |. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay

For each age group, approximately 100 age-synchronized N2 worms were collected for total messenger RNA (mRNA) extraction. To achieve age synchronization, we put approximately 50 gravid adult worms in the NGM plate and allow them to lay eggs for 1–2 h. Of note, age synchronization using the bleaching technique triggers robust UPRCYTO in the L1 and L2 larval worms (not shown). The total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). qPCR reactions were performed in 10 μl with the primer concentration of 1 μM mixed with the PowerUp SYBR Green Master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad). For all qPCR experiments, the mRNA level of act-1 was used for normalization. qPCR primers used in this study: act-1 forward: GCTGGACGTGATCTTACTGATTACC, act-1 reverse: GTAGCAGAGCTTCTCCTTGATGTC; hsp-4 forward: GACATCGAGCGCATGATCAA, hsp-4 reverse: CCTTGTCGGCGATTTGAGTT; hsp-6 forward: TCGTGAACGTTTCAGCCAGA, hsp-6 reverse: CTCAGCGGCATTCTTTTCGG; hsp-16.2 forward: AGATGTAGATGTTGGTGCAGT, hsp-16.2 reverse: TCTCTTCGACGATTGCCTGT.

2.4 |. Fluorescence microscopy and GFP reporter assay

To monitor the UPRER, UPRMITO, and UPRCYTO, age-synchronized zcls4[hsp-4p∷GFP], zcls13[hsp-6p∷GFP], and gpIs1[hsp-16.2p∷GFP] worms were placed on NGM plates (for the UPRER and UPRCYTO) or RNAi plates seeded with RNAi plasmid-containing bacteria (for the UPRMITO). After the induction of UPRs, worms at different ages were immobilized with 10 mM levamisole (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and imaged at room temperature (22–25°C) using an Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope coupled with a 10X UPlanFI objective and QImaging optiMOS camera. Of note, acute levamisole treatment did not induce UPRER, UPRMITO, or UPRCYTO (Figure S1). In addition, our fluorescence microscopy was performed at standard room temperature (22–25°C), while all worms were grown and maintained at 20°C. To minimize the exposure to the warm temperature and reduce the potential impact of warm temperature on UPRs, worms were quickly mounted on slides and each microscopy experiment was typically completed within 2 min. Based on our UPR reporter assays, we did not observe any noticeable induction of UPRER, UPRMITO, or UPRCYTO within this short period (not shown). Images were captured using the μManager software (https://micro-manager.org/), and the fluorescence signals of the whole worms were quantified using the ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). To compare different worms and genotypes, fluorescence signals were normalized to the area of worms.

2.5 |. Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using Prism 7 (GraphPad Software), and one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s multiple comparison test or unpaired student t test was used to compare different groups. For all experiments, data were shown as mean ± SEM, and a p value of less than .05 was considered as statistically significant. Sample sizes were determined by the reproducibility of the experiments.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. The endogenous UPRs elevate during aging

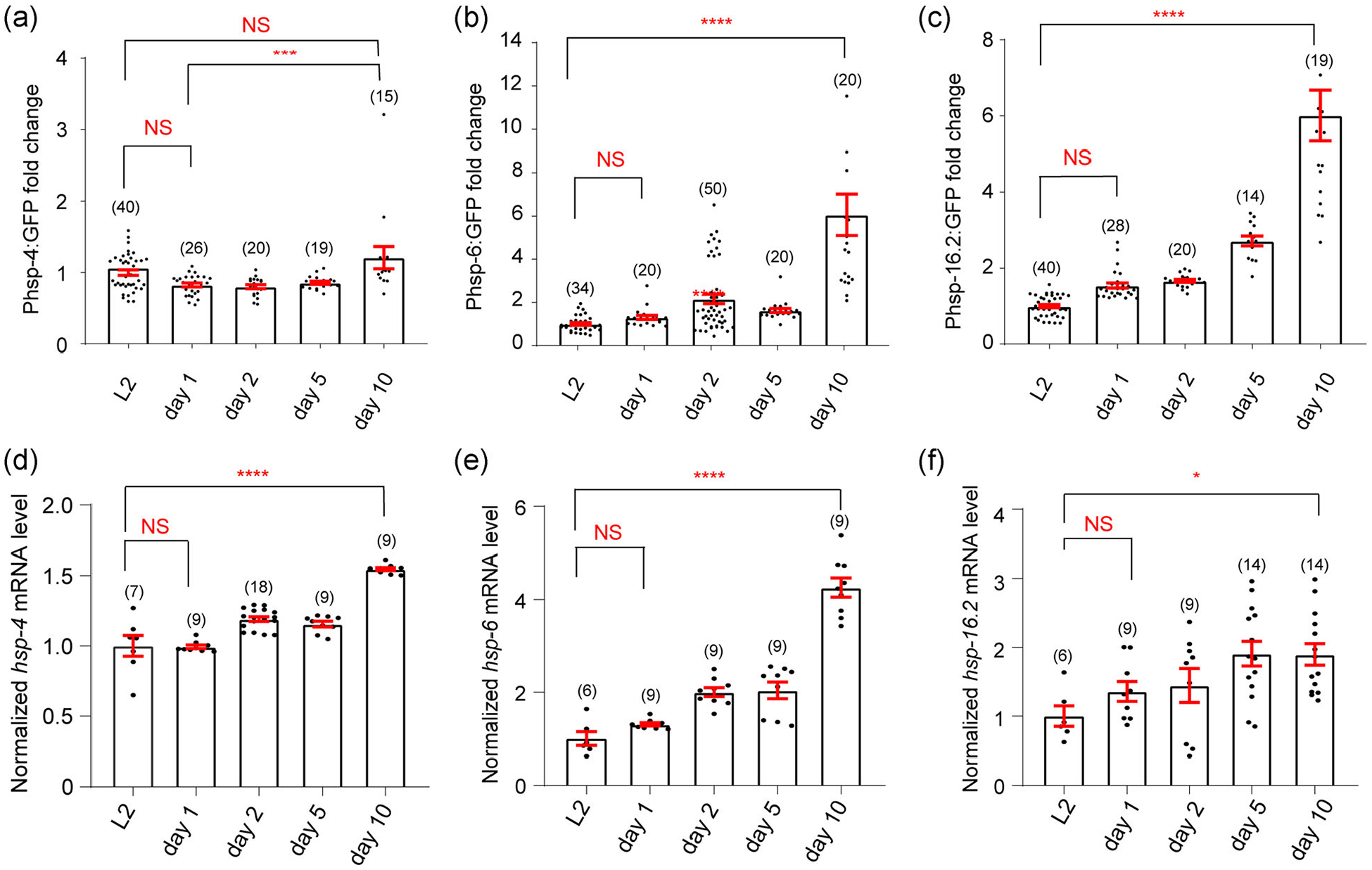

Most of the previous studies on UPRs have focused on the acute stress-induced UPRs, but not endogenous UPRs. As proteotoxic stress is a constant challenge throughout the lifespan of an organism, we were curious about the potential changes of endogenous UPRs at different life stages. To study this question, we decided to use the genetic model organism C. elegans, which features a short lifespan (~20 days under standard laboratory conditions) and a transparent body. First, we used the well-established reporter strains zcls4[hsp-4p∷GFP] (GFP driven by the ER chaperone BIP (hsp-4) promoter), zcls13[hsp-6p∷GFP] (GFP driven by the mitochondrial chaperone HSP70 (hsp-6) promoter), and gpIs1[hsp-16.2p∷GFP] (GFP driven by the heat shock protein hsp-16.2 promoter) which allow us to monitor the UPRER, UPRMITO, and UPRCYTO, respectively, in real time (Calfon et al., 2002; Rea et al., 2005; Yoneda et al., 2004). Similar to many other species, C. elegans exhibits an age-dependent increase in autofluorescence which is typically due to the buildup of “age pigment” or lipofuscin (Forge & Macguidwin, 1989). As this autofluorescence could potentially interfere with our imaging experiments of UPR reporters, we subtracted the green autofluorescence signals of age-matched wild type N2 worms from the GFP signal of each UPR reporter line. These background-corrected GFP signals should give us an indication of the endogenous UPRs at different ages (L2 of the larval stage, Day 1, 2, 5, and 10 of adulthood). Overall, we observed an age-related increase in all three types of endogenous UPRs (Figure 1a–c).

FIGURE 1.

The endogenous UPRs elevate during aging. (a–c) The endogenous UPRs are measured using specific fluorescent reporters Phsp-4∷GFP (UPRER) (a), Phsp-6∷GFP (UPRMITO) (b), and Phsp-16.2∷GFP (UPRCYTO) (c). The fluorescence intensity of reporter strains is compared among different age groups (larval 2, Day 1, 2, 5, and 10 of adulthood, respectively) and the intensity values of all age groups are normalized to the L2 group. For the UPRMITO and UPRCYTO, the background-corrected fluorescence intensity of Day 10 worms is significantly higher than that of L2 worms. For the UPRER, the mean value for Day 10 worms is significantly higher than that of Day 1, but not L2 (p = .087), worms. (d–f) In addition to the fluorescent reporter assay, the endogenous UPR levels are measured by the qPCR analyses of hsp-4 mRNA (UPRER) (d), hsp-6 mRNA (UPRMITO) (e), and hsp-16.2 mRNA (UPRCYTO) (f). In general, the mRNA levels of UPR reporter genes are significantly higher in Day 10 worms compared to that of L2 worms. Numbers in parentheses indicate the amount of worms assayed or the number of experiments repeated. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, and the statistical significance is assessed using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). *p < .05; ***p < .001; ****p < .0001; mRNA, messenger RNA; NS, not significant; qPCR, quantitative PCR; UPR, unfolded protein response

To provide additional evidence on the elevated endogenous UPRs during aging, we also performed the real-time qPCR assay to directly measure the mRNA levels of hsp-4, hsp-6, and hsp-16.2, respectively, in the wild type background. Again, old worms tend to express higher levels of UPR reporters (Figure 1d–f). Taken together, the endogenous UPRs appear to elevate during aging in C. elegans. Because our qPCR results have overall good correlation with imaging data, for convenience purpose, we decided to focus on the three fluorescent reporter strains of UPRs in subsequent studies.

3.2 |. The UPRER can be induced during both developmental stage and young adulthood

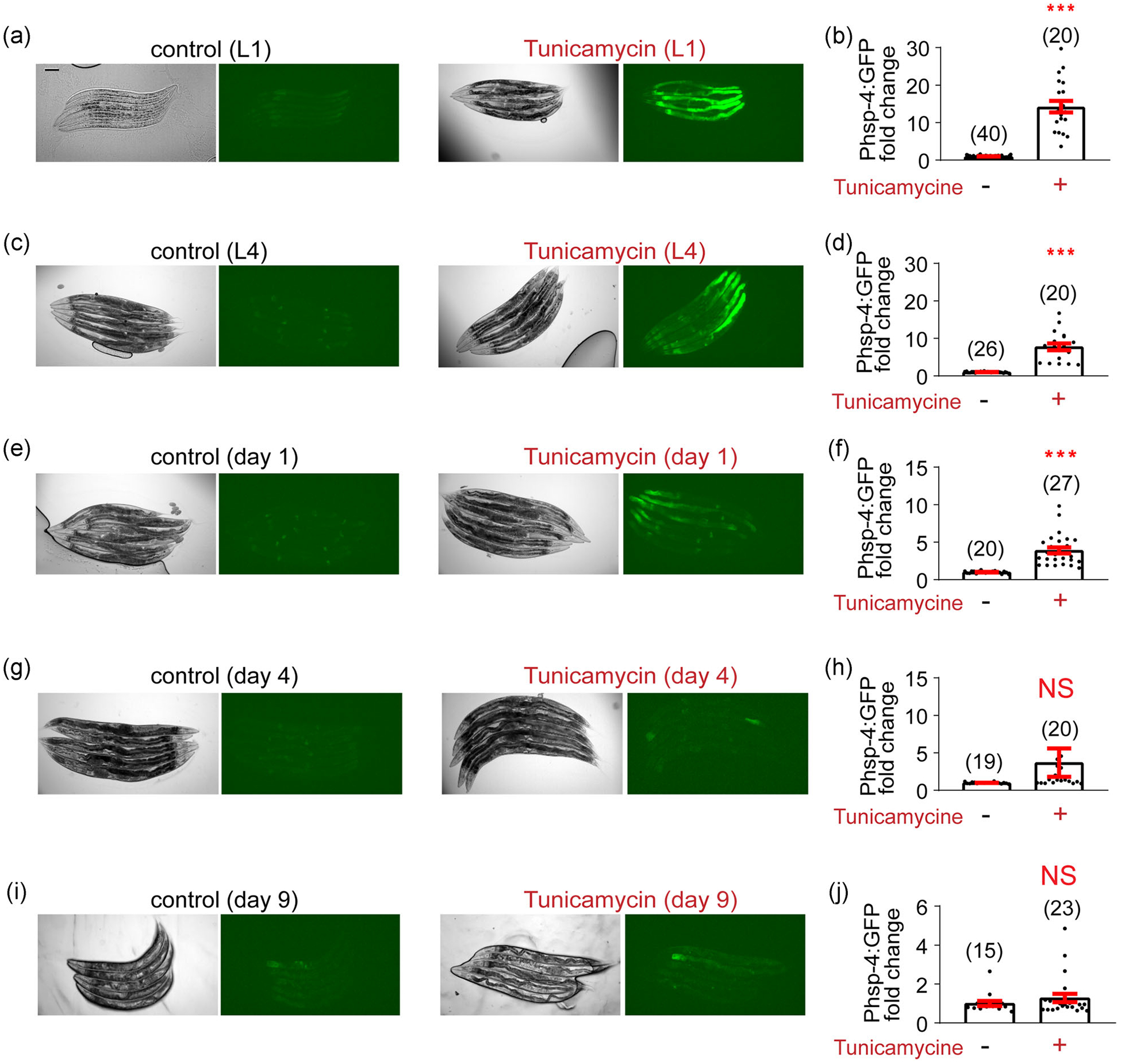

Although proteotoxic stress could occur at any life stages, studies in C. elegans suggested that there might be a specific temporal window for UPR induction (Durieux et al., 2011; Taylor & Dillin, 2013). As many studies typically only examine one type of UPRs, we next set to compare the temporal requirements to induce different types of UPRs in the same study. To experimentaly induce the UPRER in a temporally regulated manner, we used a well-established inhibitor of N-glycosylation, tunicamycin, which is a perturbant of ER homeostasis and powerful inducer of UPRER (Heifetz et al., 1979). We treated worms of different ages with a low dose of tunicamycin (5 μg/ml, 24 h) to prime the ER stress response before taking images. Consistent with a previous report (Taylor & Dillin, 2013), we found that the UPRER can be strongly induced during larval stages (L1 and L4; Figure 2a–d). Although Day 1 adult worms still displayed significant UPRER induction (Figure 2e,f), it can hardly be induced in adult worms of older ages (>Day 4; Figure 2g–j). Overall, our results suggested that the inducible UPRER exhibits an age-dependent decline since early stage of life.

FIGURE 2.

Tunicamycin can induce the UPRER during both larval stage and early adulthood. (a) Representative images of tunicamycin-induced UPRER in the zcls4[hsp-4p∷GFP] reporter line during the L1 stage. Tunicamycin (5 μg/ml in DMSO) or an equal amount of DMSO (control) is added 24 h before taking images. Scale bar, 100 μm. (b) Quantification of imaging experiments in (a). (c–j) A similar set of experiments are conducted with the zcls4[hsp-4p∷GFP] reporter line at different ages: L4 (c,d), Day 1 adulthood (e,f), Day 4 adulthood (g,h), and Day 9 adulthood (i,j). The UPRER can be induced during larval stages and Day 1 adulthood, but not Day 4 or 9 adulthood. Numbers in parentheses indicate the amount of worms assayed. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, and the statistical significance is assessed using the unpaired student t test. ***p < .001; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; NS, not significant; UPR, unfolded protein response

3.3 |. The inducible UPRMITO occurs specifically during the developmental stage

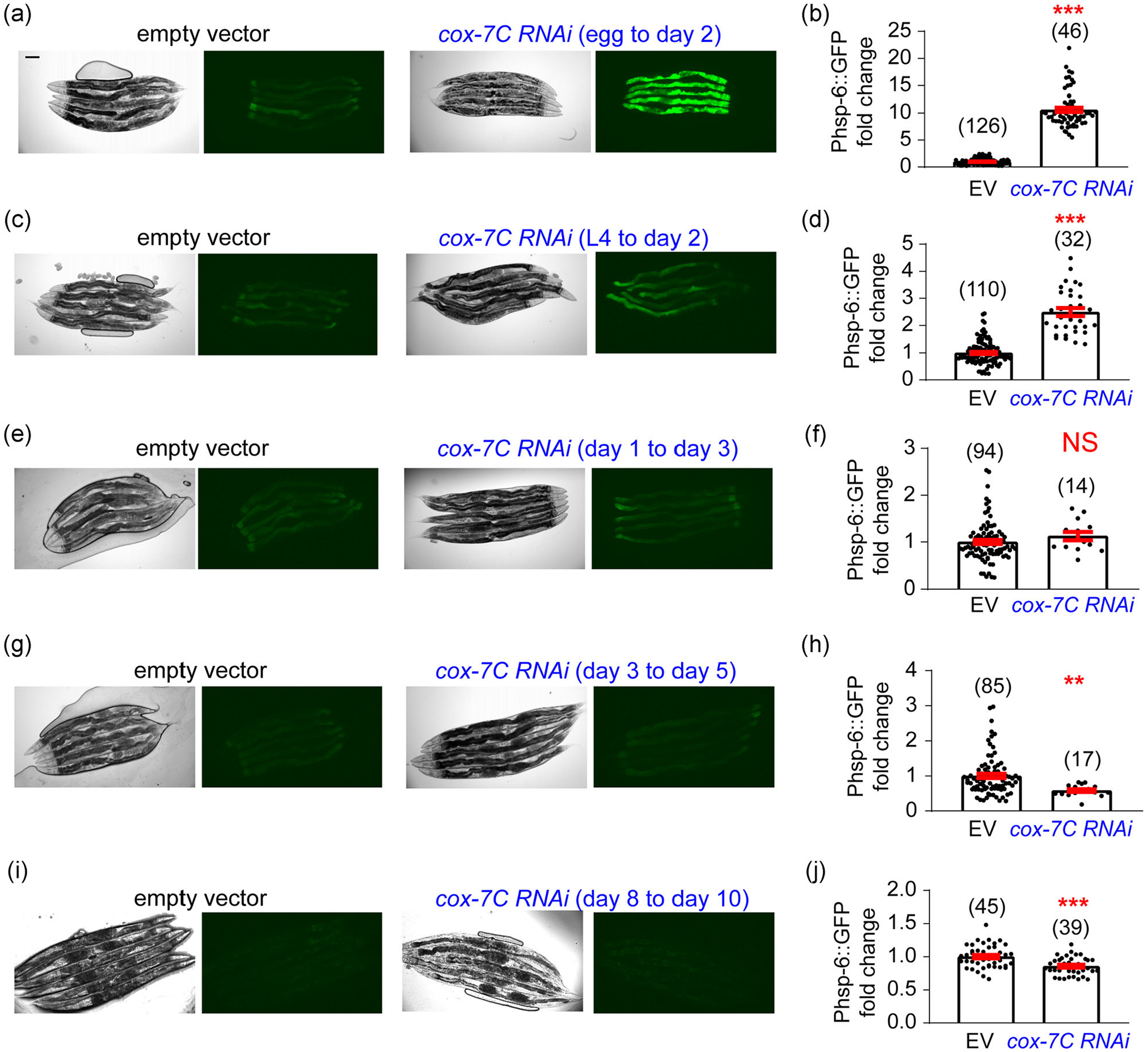

RNAi-mediated disruption of ETC is widely used to induce the UPRMITO (Naresh & Haynes, 2019). We thus assayed multiple RNAi clones against different components of ETC, and found that RNAi of the complex IV component cox-7C seems to be the strongest inducer of UPRMITO as revealed by the zcls13[hsp-6p∷GFP] reporter (not shown). Interestingly, although cox-7C RNAi from egg till Day 2 of adulthood can potently induce the UPRMITO, the same treatment from the L4 larval stage to Day 2 of adulthood induced a much weaker but still significant UPRMITO (Figure 3a–d). Furthermore, after Day 1 of adulthood, cox-7C RNAi can no longer induce the UPRMITO (Figure 3e–j). Thus, in line with the previous study that targeted the cytochrome c oxidase-1 subunit Vb/COX4 (cco-1; Durieux et al., 2011), our results suggested that the inducible UPRMITO mainly occurs during the developmental stage.

FIGURE 3.

cox-7C RNAi can only induce the UPRMITOduring larval stages. (a) Representative images of cox-7C RNAi-induced UPRMITO in the zcls13[hsp-6p∷GFP] reporter line. The RNAi treatment starts from egg until Day 2 adulthood, and images are taken at Day 2 adulthood. Scale bar, 100 μm. (b) Quantification of imaging experiments in (a). (c–j) A similar set of experiments are conducted with the zcls13[hsp-6p∷GFP] reporter line, and cox-7C RNAi is initiated at different stages: starting from L4 till Day 2 adulthood (c, d), from Day 1 to Day 3 adulthood (e,f), from Day 3 to Day 5 adulthood (g,h), and from Day 8 to Day 10 adulthood (i,j). Images are taken on the last day of RNAi treatment for each condition. The UPRMITO can be only induced during larval stages but not adulthood. Numbers in parentheses indicate the amount of worms assayed. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, and the statistical significance is assessed using the unpaired student t test. **p < .01; ***p < .001; NS, not significant; RNAi, RNA interference; UPR, unfolded protein response

3.4 |. The inducibility of UPRCYTO is well maintained until mid-late life

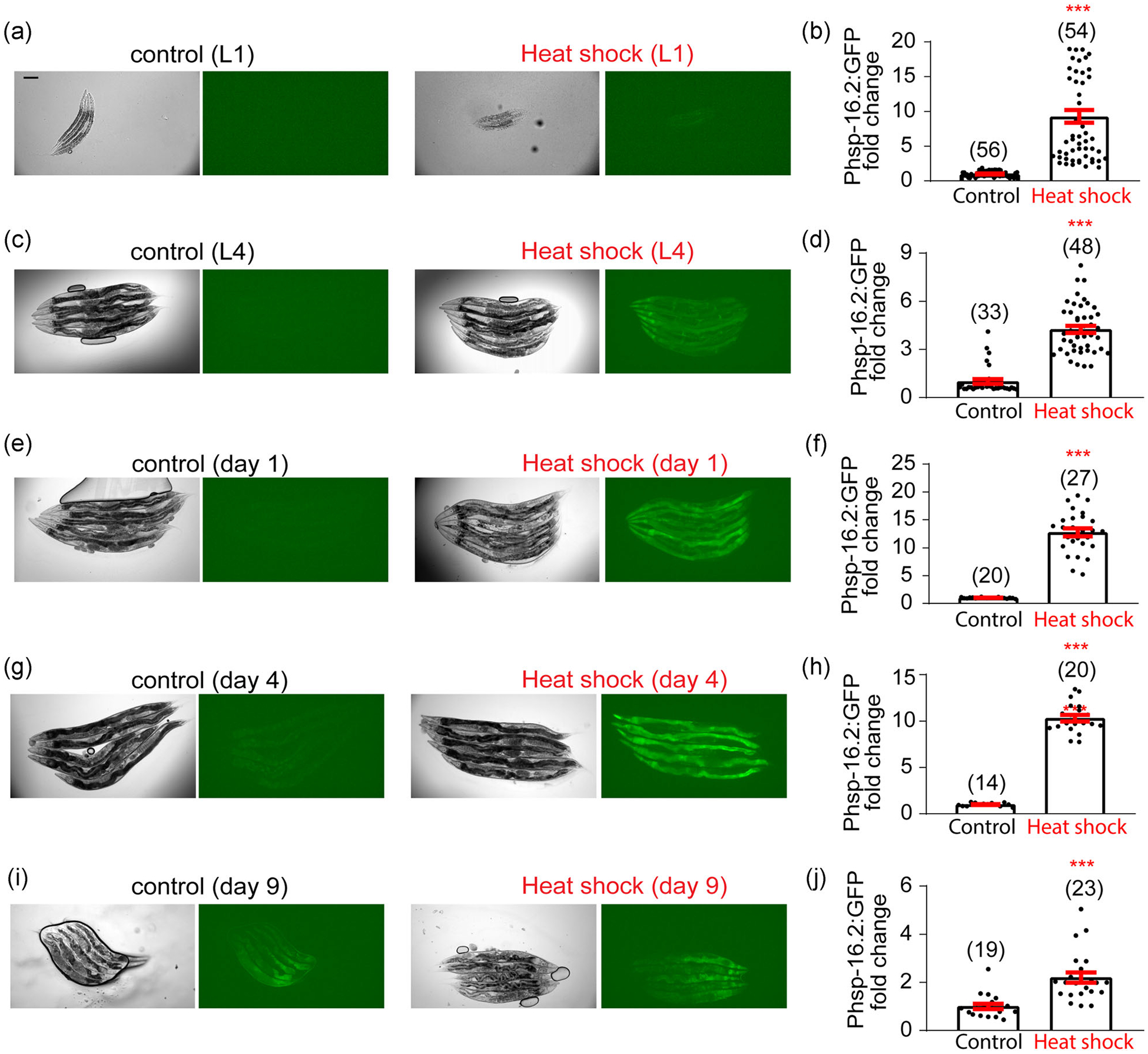

Besides the UPRER and UPRMITO, we also examined the UPRCYTO that occurs in the cytosol. To monitor the UPRCYTO, the gpIs1[hsp-16.2p∷GFP] reporter strain at different ages was heat shocked (35°C) for 1 h and images were taken 24 h after the heat shock. Interestingly, the UPRCYTO can be well induced even at advanced ages (Figure 4). Moreover, the age-dependent decline of UPRCYTO induction is significantly slower than that of the UPRER or UPRMITO. Collectively, while all three types of inducible UPRs exhibit age-dependent decline, their decline rates are different with the UPRMITO being the fastest and the UPRCYTO being the slowest.

FIGURE 4.

Heat shock induces the UPRCYTO from larval stage untill mid-late life. (a) Representative images of heat shock-induced UPRCYTO in the gpIs1[hsp-16.2p∷GFP] reporter line at the L1 stage. Heat shock (35°C) is applied for 1 h and images are taken 24 h after the heat shock. Scale bar, 100 μm. (b) Quantification of imaging experiments in (a). (c–j) A similar set of experiments are conducted with the gpIs1[hsp-16.2p∷GFP] reporter line at different ages: L4 (c,d), Day 1 adulthood (e,f), Day 4 adulthood (g,h), and Day 9 adulthood (i,j). Heat shock can induce the UPRCYTO at all stages tested, although its inducibility declines during aging. Numbers in parentheses indicate the amount of worms assayed. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, and the statistical significance is assessed using the unpaired student t test. ***p < .001. UPR, unfolded protein response

3.5 |. Different tissues exhibit distinct temporal profiles of UPR inducibility during aging

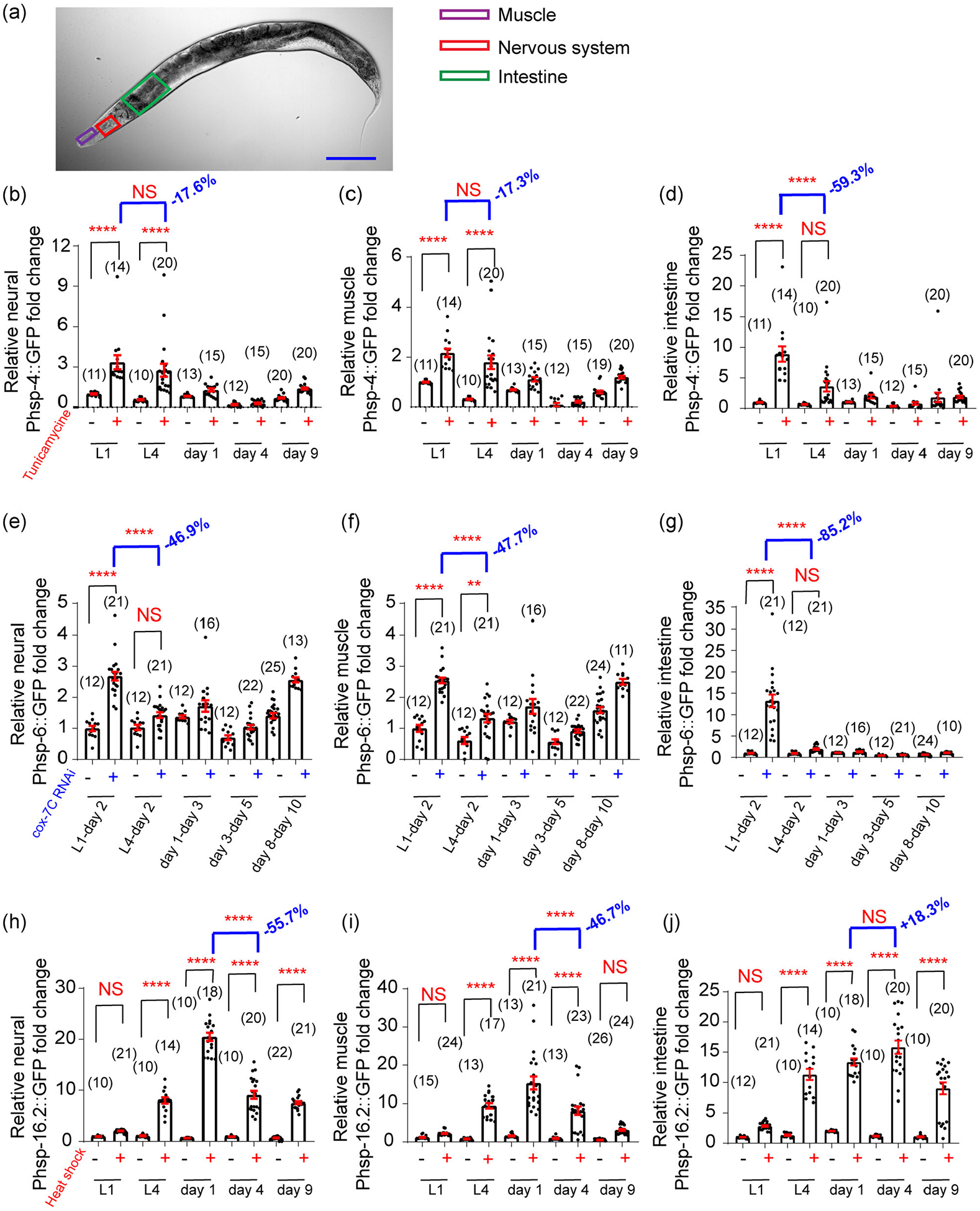

Aging is a systemic process and different tissues may differentially contribute to organismal aging (Kenyon, 2010; Riera et al., 2016). Thus, we wondered whether different tissues could display distinct temporal profiles of UPR inducibility during aging. To study it, we selected three adjacent areas in the anterior part of the worm (head muscle, nerve ring, and anterior intestine) and measured the UPR reporter fluorescence signal intensities divided by the area size (Figure 5a). This fluorescence density should allow us to monitor the inducibility of UPRER, UPRMITO, and UPRCYTO in distinct tissues at different ages. Interestingly, for both UPRER (Figure 5b–d) and UPRMITO (Figure 5e–g), the intestine exhibited a significantly faster decline of UPR inducibility than the nervous system and muscle. For example, while the decline of tunicamycine-induced UPRER was modest in the nerve ring area (17.6% reduction) and head muscle area (17.3% reduction) from L1 to L4 stage (Figure 5b,c), the intestine exhibited a 59.3% decline during the same period (Figure 5d). A similar pattern was observed for the UPRMITO, as the decline rate of cox-7C RNAi-induced UPRMITO was much larger in the intestine (85.2% reduction) than in the nerve ring area (46.9% reduction) and head muscle area (47.7% reduction) from L1 to L4 stage. Therefore, the intestine seems to be particularly vulnerable to the age-associated decline in the inducibility of UPRER and UPRMITO.

FIGURE 5.

Different tissues may exhibit distinct temporal profiles of induced UPRs during aging. (a), Distinct areas of C. elegans are chosen to quantify the induced UPRs among different tissues. For simplicity, the fluorescence intensities of head muscle (purple), nerve ring (red), and anterior intestine (green) are divided by their area size, respectively, to represent signal density at different ages. Scale bar, 100 μm. (b–d) Tunicamycin (5 μg/ml in DMSO)-induced UPRER is quantified in different tissues of zcls4[hsp-4p∷GFP] reporter line. The intestine displays a drastic decline of the UPRER inducibility from L1 to L4 stage (d). By contrast, the age-associated decline in the UPRER inducibility is much slower in the nervous system(b) and muscle (c). (e–g) cox-7C RNAi-induced UPRMITO is quantified in different tissues of zcls13[hsp-6p∷GFP] reporter line. The intestine displays a drastic decline of the UPRMITO inducibility from L1 to L4 stage (g). By contrast, the age-associated decline in the UPRMITO inducibility is significantly slower in the nervous system (e) and muscle (f). (h–j) Heat shock (35°C)-induced UPRCYTO is quantified in different tissues of gpIs1[hsp-16.2p∷GFP] reporter line. The nervous system (h) and muscle (i) display a profound decline of the UPRCYTO inducibility from Day 1 adulthood to Day 4 adulthood. By contrast, the age-associated decline in the UPRCYTO inducibility is not significant in the intestine (j) from Day 1 adulthood to Day 4 adulthood. Numbers in parentheses indicate the amount of worms assayed. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, and the statistical significance is assessed using the one-way ANOVA test. **p < .01, ****p < .0001. ANOVA, analysis of variance; UPR, unfolded protein response

Although both inducible UPRER and UPRMITO primarily occur during the developmental stage (Figures 2 and 3), the UPRCYTO can be induced until mid-late life (Figure 4). Intriguingly, unlike the UPRER or UPRMITO, the largest age-associated decline in UPRCYTO inducibility occurred in the nervous system and muscle, but not in the intestine (Figure 5h–j). For example, while the decline of heat shock-induced UPRCYTO was profound in the nerve ring area (55.7% reduction) and head muscle area (46.7% reduction) from Day 1 adulthood to Day 4 adulthood (Figure 5h,i), such a decline was not observed in the intestine (Figure 5j). Collectively, different tissues appear to display distinct temporal profiles of UPR inducibility during aging.

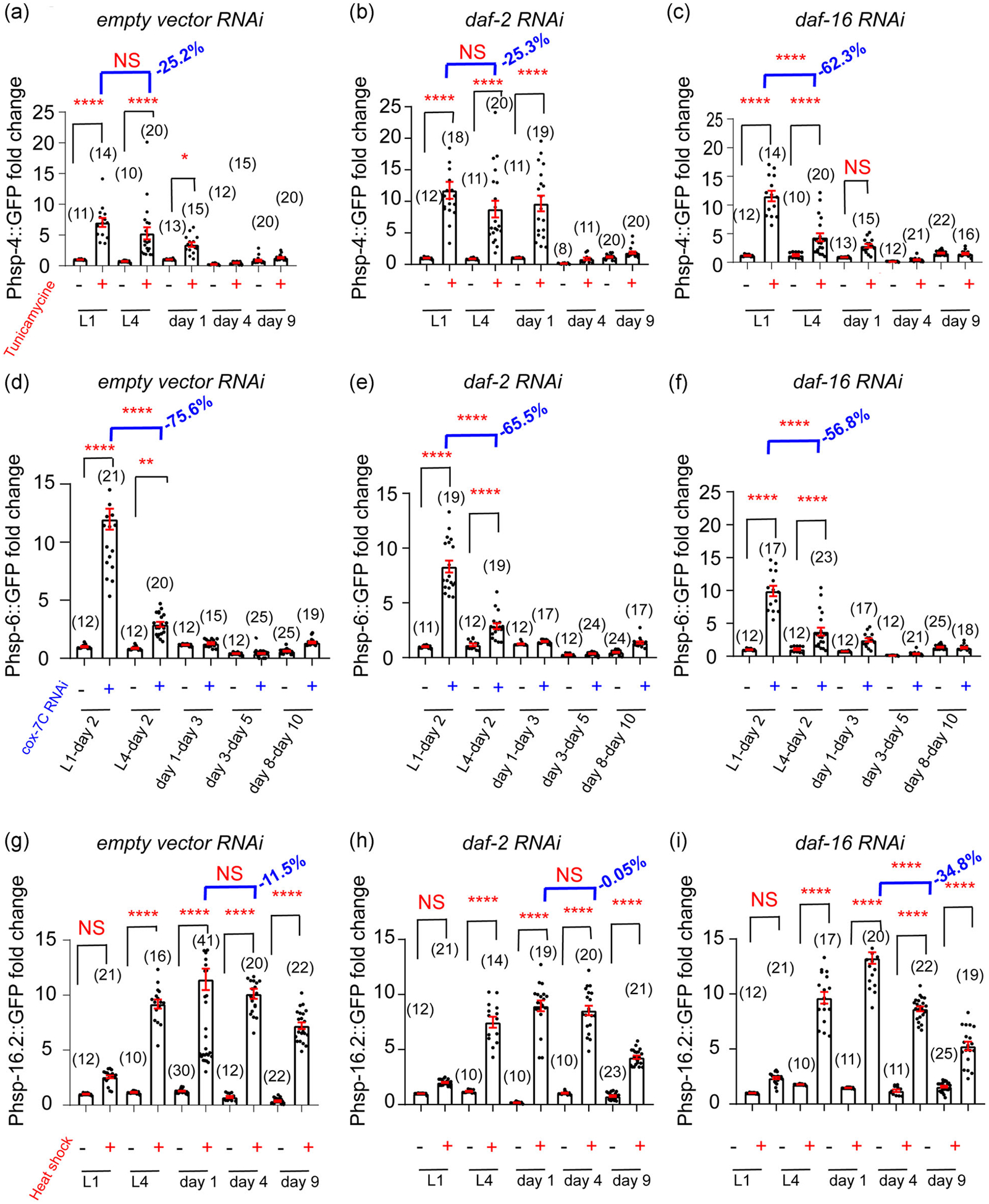

3.6 |. The temporal actions of UPRs can be modified by genetic factors

Aging and longevity are known to be regulated by evolutionarily conserved genetic factors and signaling pathways (Riera et al., 2016). We next set to test whether aging-related genetic factors could affect the age-related decline of UPR inducibility. Since the IIS pathway is arguably the best studied pathway involved in longevity modulation (Kenyon, 2010), we treated different UPR reporter lines with empty vector RNAi (control), daf-2 (the C. elegans insulin receptor) RNAi, or daf-16 (the C. elegans FOXO transcription factor downstream of IIS pathway) RNAi. Notably, daf-2 RNAi is well-established to extend lifespan whereas daf-16 RNAi shortens it (Hamilton et al., 2005; Samuelson et al., 2007).

For the UPRER, daf-2 RNAi seemed to delay the age-associated decline of inducibility as tunicamycine could still potently induce the UPRER at Day 1 adulthood (Figure 6a,b). By contrast, daf-16 RNAi accelerated the decline of UPRER inducibility, as the decline of tunicamycine-induced UPRER was much larger after daf-16 RNAi treatment (62.3% reduction) compared to empty vector RNAi treatment (25.2% reduction) from L1 to L4 stage (Figures 6a and 6c). A similar pattern was observed for the UPRCYTO. Namely, daf-2 RNAi delayed the age-associated decline of UPRCYTO inducibility while daf-16 RNAi accelerated the decline (Figure 6g–i). For example, although there was hardly any decline in the heat shock-induced UPRCYTO from Day 1 adulthood to Day 4 adulthood after daf-2 RNAi treatment (Figure 6h), a significant decline was observed in daf-16 RNAi-treated worms from Day 1 adulthood to Day 4 adulthood (Figure 6i). In contrast to the UPRER and UPRCYTO, the age-related decline in UPRMITO inducibility appeared not to be regulated by the IIS pathway, since neither daf-2 RNAi nor daf-16 RNAi significantly change the large decline of UPRMITO inducibility from L1 to L4 stage (Figure 6d–f). Thus, different genetic pathways may be involved in regulating the temporal actions of distinct types of UPRs.

FIGURE 6.

The age-associated decline in UPR inducibility can be modified by genetic factors. (a–c) Compared to the empty vector RNAi control (a) and daf-2 RNAi (b), daf-16 RNAi significantly accelerates the decline of UPRER inducibility from L1 to L4 stage (c). (d–f), Insulin pathway appears not to have a major impact on the age-associated decline of UPRMITO inducibility, as neither daf-2 RNAi (e) nor daf-16 RNAi (f) profoundly changes the decline of UPRMITO inducibility from L1 to L4 stage (d). (g–i) Compared to the empty vector RNAi control (g), daf-2 RNAi (h) delays the decline of UPRCYTO inducibility from Day 1 adulthood to Day 4 adulthood, whereas daf-16 RNAi (i) accelerates it. Numbers in parentheses indicate the amount of worms assayed. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, and the statistical significance is assessed using the one-way ANOVA test. * p < .05, **p < .01, ****p < .0001; ANOVA, analysis of variance; NS, not significant; RNAi, RNA interference; UPR, unfolded protein response

4 |. DISCUSSION

Proteotoxic stress is an inevitable burden for all living organisms throughout their life. To cope with this challenge, cells have developed sophisticated mechanisms to maintain proteostasis, and different types of UPRs are major players in this process. The hsf-1 mutant worm with disrupted UPRCYTO is short-lived while HSF-1 overexpression leads to lifespan extension in C. elegans (Hsu et al., 2003; Morley & Morimoto, 2004). Additionally, the UPRMITO may be required for ETC-mediated longevity and constitutive activation of the UPRER in neurons extends lifespan in worms (Durieux et al., 2011; Taylor & Dillin, 2013). Therefore, all three types of UPRs are involved in lifespan regulation.

Similar to many other physiological processes, the capacity of UPRs declines during aging (Higuchi-Sanabria et al., 2018; Labbadia & Morimoto, 2015). In this study, we performed a systemic comparison on the distinct temporal requirements of UPRER, UPRMITO, and UPRCYTO. Consistent with previous reports (Durieux et al., 2011; Morley & Morimoto, 2004; Taylor & Dillin, 2013), our results suggested that the inducibility of all three types of UPRs decline with age. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the decline kinetics of these UPRs is different. Namely, the UPRMITO can no longer be induced after the developmental stage, whereas the UPRER can still be induced until young adulthood. By contrast, the inducibility of UPRCYTO is maintained even in the mid-late life. Nonetheless, it should be noted that the underlying mechanisms of the distinct decline rate of different types of UPRs are unclear. It is possible that different sets of transcription factors and/or modulators might coordinate to determine the temporal actions of different UPRs. For example, while the FOXO transcription factor DAF-16 regulates the temporal window of UPRER and UPRCYTO activation, it seems not to have a major impact on the temporal action of UPRMITO induction (Figure 6). More studies are clearly needed to address this important question. On the other hand, since the molecular mechanisms of UPRs are evolutionarily conserved, it would be interesting to examine whether similar temporal requirements apply to the induction of UPRER, UPRMITO, and UPRCYTO in mammals.

What is the possible physiological significance of the distinct temporal actions of different types of UPRs? This difference in temporal requirements might correlate with the temporal window during which distinct UPRs modulate longevity. In line with this idea, the ETC-mediated lifespan regulation also specifically occurs during the larval stage, which overlaps with the temporal requirement of UPRMITO induction (Dillin et al., 2002; Durieux et al., 2011). Additionally, the UPRER–protected longevity occurs in Day 1 but not Day 7 of adulthood when worms are under ER stress (Taylor & Dillin, 2013). Furthermore, expression of the UPRCYTO reporter HSP-16.2 predicts lifespan in worms (Mendenhall et al., 2012; Rea et al., 2005). Nevertheless, it remains to be determined whether the temporal window when UPRCYTO regulates lifespan also correlates with its temporal mode of induction.

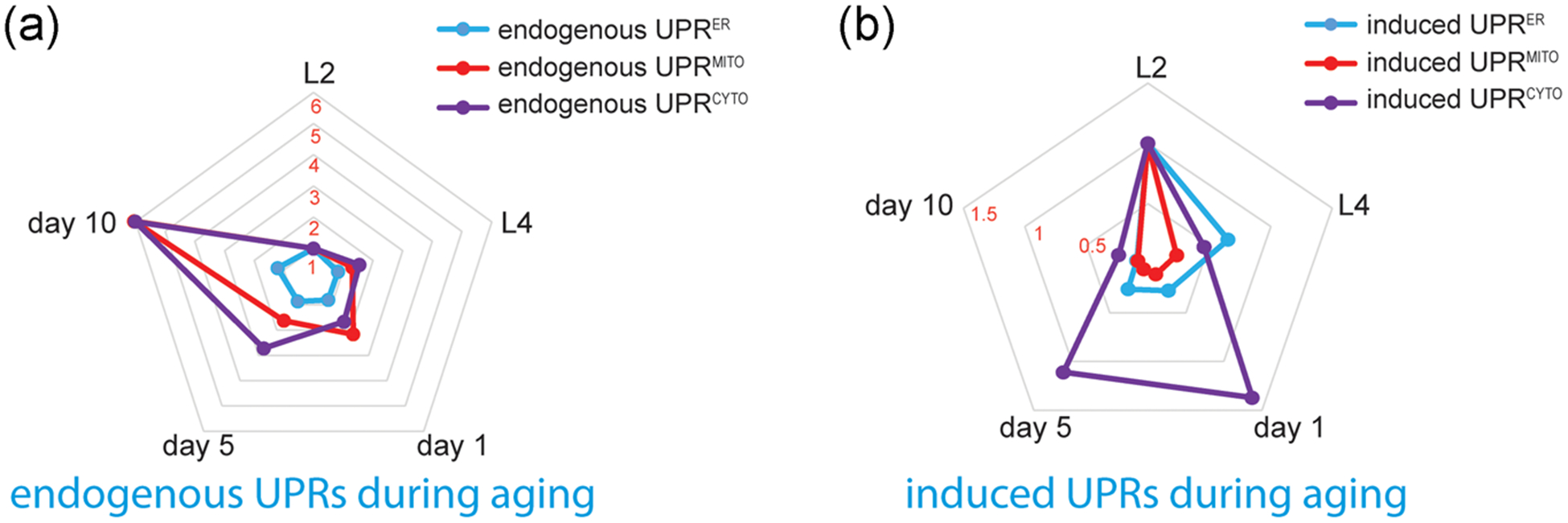

An interesting observation of our current study is the increase of endogenous UPRs (particularly the UPRMITO and UPRCYTO) during aging (Figure 7a), which is opposite to the age-related decline of induced UPRs (Figure 7b). How to reconcile this discrepancy? It is possible that the status of proteostasis gradually declines with age, which may trigger adaptive protein quality control responses in the mitochondria, cytosol, and ER. As a result, the constitutive, low-grade, and endogenous UPRs elevate during aging, and these protective responses might serve as a counteraction against aging.

FIGURE 7.

Radar charts of the age-related changes in endogenous UPRs and induced UPRs. A normalized, permutated radar chart is used to compare the endogenous UPRs (a) and induced UPRs (b) at different ages. Based on our fluorescent reporter assays, the mean fluorescence intensities of distinct UPR reporters at different ages are normalized to that of L2 worms. Overall, the endogenous UPRs elevate during aging, while different types of induced UPRs exhibit distinct age-related decline rates. UPR, unfolded protein response

Although cellular compartments such as endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, and cytosol are present in nearly all cell types, surprisingly, we found that different tissues can display distinct temporal profiles of UPR inducibility during aging (Figure 5). Namely, the age-related decline in the inducibility of UPRER and UPRMITO is more profound in the intestine, while the nervous system and muscle have a faster decline of UPRCYTO inducibility during aging. These results suggest that subcellular defense mechanisms might decline with different rates in different tissues. Notably, the intestine is a central hub of C. elegans metabolism and longevity regulation (McGhee, 2007). The quick decline of UPRER and UPRMITO inducibility in the intestine may contribute to its role in lifespan modulation. Taken together, our systematic reporter assay in C. elegans revealed the distinct temporal actions of different types of UPRs during aging, which may provide very useful insights into similar processes of other species.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (AG063766 and AG028740), the American Cancer Society (RSG-17-171-01-DMC), and the American Federation for Aging Research. We appreciate the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center, which is supported by the National Institutes of Health Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440), for providing strains.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

REFERENCES

- Brenner S (1974). Genetics of caenorhabditis-elegans. Genetics, 77(1), 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calfon M, Zeng H, Urano F, Till JH, Hubbard SR, Harding HP, Clark SG, & Ron D (2002). IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature, 415(6867), 92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillin A, Hsu AL, Arantes-Oliveira N, Lehrer-Graiwer J, Hsin H, Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, & Kenyon C (2002). Rates of behavior and aging specified by mitochondrial function during development. Science, 298(5602), 2398–2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durieux J, Wolff S, & Dillin A (2011). The cell-non-autonomous nature of electron transport chain-mediated longevity. Cell, 144(1), 79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge TA, & Macguidwin AE (1989). Nematode autofluorescence and its use as an indicator of viability. Journal of Nematology, 21(3), 399–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton B, Dong Y, Shindo M, Liu W, Odell I, Ruvkun G, & Lee SS (2005). A systematic RNAi screen for longevity genes in C. elegans. Genes and Development, 19(13), 1544–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heifetz A, Keenan RW, & Elbein AD (1979). Mechanism of action of tunicamycin on the UDP-GlcNAc:dolichyl-phosphate Glc-NAc-1-phosphate transferase. Biochemistry, 18(11), 2186–2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi-Sanabria R, Frankino PA, Paul JW 3rd, Tronnes SU, & Dillin A (2018). A futile battle? Protein quality control and the stress of aging. Developmental Cell, 44(2), 139–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu AL, Murphy CT, & Kenyon C (2003). Regulation of aging and age-related disease by DAF-16 and heat-shock factor. Science, 300(5622), 1142–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joutsen J, & Sistonen L (2019). Tailoring of Proteostasis Networks with Heat Shock Factors. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 11, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon CJ (2010). The genetics of ageing. Nature, 464(7288), 504–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles TP, Vendruscolo M, & Dobson CM (2014). The amyloid state and its association with protein misfolding diseases. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 15(6), 384–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbadia J, & Morimoto RI (2015). The biology of proteostasis in aging and disease. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 84, 435–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGhee JD (2007). The C. elegans intestine. WormBook: the online review of C. elegans biology, 1–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendenhall AR, Tedesco PM, Taylor LD, Lowe A, Cypser JR, & Johnson TE (2012). Expression of a single-copy hsp-16.2 reporter predicts life span. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 67(7), 726–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley JF, & Morimoto RI (2004). Regulation of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans by heat shock factor and molecular chaperones. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 15(2), 657–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naresh NU, & Haynes CM (2019). Signaling and regulation of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 11, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea SL, Wu D, Cypser JR, Vaupel JW, & Johnson TE (2005). A stress-sensitive reporter predicts longevity in isogenic populations of caenorhabditis elegans. Nature Genetics, 37(8), 894–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter K, Haslbeck M, & Buchner J (2010). The heat shock response: Life on the verge of death. Molecular Cell, 40(2), 253–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riera CE, Merkwirth C, De Magalhaes Filho CD, & Dillin A (2016). Signaling networks determining life span. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 85, 35–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan L, Wang Y, Zhang X, Tomaszewski A, McNamara JT, & Li R (2020). Mitochondria-associated proteostasis. Annual Review of Biophysics, 49, 41–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson AV, Carr CE, & Ruvkun G (2007). Gene activities that mediate increased life span of C. elegans insulin-like signaling mutants. Genes & Development, 21(22), 2976–2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RC, & Dillin A (2013). XBP-1 is a cell-nonautonomous regulator of stress resistance and longevity. Cell, 153(7), 1435–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter P, & Ron D (2011). The unfolded protein response: From stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science, 334(6059), 1081–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao R, Chun L, Ronan EA, Friedman DI, Liu J, & Xu XZ (2015). RNAi interrogation of dietary modulation of development, metabolism, behavior, and aging in C. elegans. Cell Reports, 11(7), 1123–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao R, Zhang B, Dong Y, Gong J, Xu T, Liu J, & Xu XZ (2013). A genetic program promotes C. elegans longevity at cold temperatures via a thermosensitive TRP channel. Cell, 152(4), 806–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneda T, Benedetti C, Urano F, Clark SG, Harding HP, & Ron D (2004). Compartment-specific perturbation of protein handling activates genes encoding mitochondrial chaperones. Journal of Cell Science, 117(Pt 18), 4055–4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.