Abstract

Behavior therapy is a first-line intervention for Tourette’s Disorder (TD), and a key component is the practice of therapeutic skills between treatment visits (i.e., homework). This study examined the relationship between homework adherence during behavior therapy for TD and therapeutic outcomes, and explored baseline predictors of homework adherence during treatment.

Participants included 119 individuals with TD (70 youth, 49 adults) who received behavior therapy in a clinical trial. After a baseline assessment of tic severity and clinical characteristics, participants received 8 sessions of behavior therapy. Therapists recorded homework adherence at each therapy session. After treatment, tic severity was re-assessed by independent evaluators masked to treatment condition.

Greater overall homework adherence predicted tic severity reductions and treatment response across participants. Early homework adherence predicted therapeutic improvement in youth, whereas late adherence predicted improvement in adults. Baseline predictors of greater homework adherence in youth included lower hyperactivity/impulsivity and caregiver strain. Meanwhile in adults, baseline predictors of increased homework adherence included younger age, lower hyperactivity/impulsivity, obsessive-compulsive severity, anger, and greater work-related disability.

Homework adherence is an integral component of behavior therapy and linked to therapeutic improvement. Strategies that improve homework adherence may optimize the efficacy of behavioral treatments and improve treatment outcomes.

Keywords: Tics, Homework Adherence, Behavior Therapy, Comprehensive Behavioral Intervention for Tics

Introduction

Tourette’s Disorder and persistent tic disorders (collectively referred to as TD) are neurodevelopmental conditions that affect almost 1% of the population (Scahill et al., 2014). For many individuals with TD, tics cause school/work difficulties, and social problems, emotional distress, and at times, physical pain (Conelea et al., 2011, 2013). Youth and adults with TD often experience co-occurring psychiatric conditions such as attention deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and anxiety disorders (Freeman et al., 2000). The combination of tics and associated psychiatric conditions can result in problems across multiple domains of functioning (e.g., school, work, social life, family functioning, negative self-view) and poor overall quality of life (Cloes et al., 2017; Conelea et al., 2011, 2013; Hanks et al., 2016; Storch et al., 2007). Thus, interventions to effectively manage TD bear considerable importance across the lifespan.

While TD has been historically managed with pharmacological treatments (Essoe et al., 2019), behavior therapy is an efficacious intervention for TD that yields large treatment effects across clinical trials (McGuire et al., 2014; Piacentini et al., 2010; Wilhelm et al., 2012), and has shown some secondary benefit on co-occurring psychiatric conditions and psychosocial functioning (McGuire et al., 2020; Woods et al., 2011). Given its efficacy and tolerability (Peterson et al., 2016), behavior therapy is currently recommended as a first-line intervention for TD by multiple professional organizations (Murphy et al., 2013; Pringsheim et al., 2019; Steeves et al., 2012; Verdellen et al., 2011). Nevertheless, only approximately 50% of youth (Piacentini et al., 2010) and 38% of adults (Wilhelm et al., 2012) with TD exhibit a positive treatment response to behavior therapy. Moreover, even amongst those who exhibit a positive treatment response, bothersome tics often persist and cause impairment (Piacentini et al., 2010; Wilhelm et al., 2012). Therefore, it is important to determine factors that contribute to treatment response and improve therapeutic outcomes for this evidence-based intervention (Essoe et al., 2019; Scahill et al., 2013).

Homework adherence, sometimes referred to as homework compliance (Chakrabarti, 2014), is one factor that may influence behavior therapy outcomes, but its effect on TD treatment remains unexamined. “Homework” broadly refers to the utilization (or practice) of therapeutic skills between therapy sessions. When patients practice skills between therapy sessions (i.e., exhibit “good” homework adherence), the learning that begins within therapy sessions is strengthened through repetition and becomes more readily accessible. Beyond facilitating the generalization of learning from the clinic to a patient’s natural environment (e.g., home, school, work place), the practice of therapeutic skills between therapy sessions also makes learning more resilient to contextual changes and the passage of time (Kazantzis & Lampropoulos, 2002). Although homework adherence remains unexamined in behavior therapy for TD, it has been well-studied in the psychosocial treatments (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy) of OCD and anxiety—conditions related to TD, and often co-occur with TD.

In OCD, empirical investigations have generally identified that greater homework adherence predicts greater therapeutic improvement (Abramowitz et al., 2002; Anand et al., 2011; Maher et al., 2012; Olatunji et al., 2015; Park et al., 2014; Wheaton et al., 2016). Homework adherence itself may be differentially impacted by various factors. For example, in pediatric OCD, greater baseline OCD severity was associated with increased homework adherence, and greater levels of externalizing symptoms were associated with decreased homework adherence (Park et al., 2014). Please see Wheaton & Chen (2020) and Leeuwerik et al. (2019) for a discussion on the importance of homework adherence in OCD.

In contrast, the relationship between homework adherence and treatment outcomes in anxiety disorders is less clear (Cammin-Nowak et al., 2013; Hughes & Kendall, 2007; Schmidt & Woolaway-Bickel, 2000; Westra et al., 2007; Westra & Dozois, 2006; Wetherell et al., 2005; Woods et al., 2002; Woody & Adessky, 2002; Wu et al., 2020). Some reports suggest that the timing of homework adherence (early versus late adherence in treatment) may influence therapeutic improvement, and timing patterns differ between samples of youth and adults (Park et al., 2014; Simpson et al., 2011; Westra & Dozois, 2006). As meta-analyses demonstrate that homework adherence is broadly associated with therapeutic improvement across psychosocial treatments (Kazantzis et al., 2016; Mausbach et al., 2010), understanding the relationship between homework adherence and therapeutic improvement from behavior therapy for TD may offer new insights for enhancing tic severity reductions achieved during this evidence-based treatment. Please see Kazantzis et al. (2017) for further discussion on homework adherence for anxiety and depression.

For behavior therapies such as habit reversal training (HRT; Azrin & Peterson, 1990) and its successor, Comprehensive Behavioral Interventions for Tics (CBIT; Woods et al., 2008), two therapeutic skills—awareness training and competing response training—are emphasized. Awareness training builds awareness to the occurrence of tics and eventually incorporates detection of early tic movements or premonitory urges that precede the tic. Meanwhile, competing response training focuses on developing and implementing a competing response contingent upon the early detection of the tic. A competing response is a behavior that is physically incompatible with the tic, is socially discrete, and could be maintained for up to one minute (or until the urge is dissipated/tolerated). In practice, once a tic or an urge is detected, the patient performs the competing response to inhibit the expression of the targeted tic. After these skills are learned within therapy sessions, between-session practice (homework) is applied to reinforce and strengthen the learned behavioral responses. A social support person (usually a caregiver or partner) is trained to assist the patient in the repeated implementation of these skills outside of therapy sessions.

Practicing therapeutic skills outside of therapy sessions is important for skill development, and also enables skill recall and implementation in ecologically valid situations outside of the therapist’s office (Cummings et al., 2014). For instance, patients with TD who have “good” homework adherence would regularly practice therapeutic skills and acquire greater experience implementing these skills during daily activities. This would strengthen behavior therapy skill learning, facilitate the generalization of learning across real-life situations, and likely produce greater reduction in tic severity. However, patients with “intermediate” or even “poor” homework adherence would likely experience less skill learning, exhibit less generalization of learning in ecologically valid settings (e.g., home, work, school), and experience less reduction in tic severity.

This study examined homework adherence in 119 individuals with TD who received behavior therapy as part of two randomized clinical trials. First, we characterized behavior therapy homework adherence and compared differences between “good” and “intermediate or poor” homework adherence. Second, we examined whether homework adherence changed across treatment sessions. Third, we examined the predictive relationship between homework adherence and reductions in tic severity and treatment response. Fourth, we evaluated whether outcomes differed between early and late homework adherence. Finally, we investigated baseline factors that predicted homework adherence based on the extant literature in related disorders.

Methods

Participants

Participants received behavior therapy for TD as part of two randomized multisite clinical trials (NCT00218777, NCT00231985; Piacentini et al., 2010; Wilhelm et al., 2012) These studies employed similar inclusion criteria, with exception of age. All participants had: (1) a diagnosis of TD of moderate or greater severity; (2) English fluency; (3) an estimated IQ > 80; and (4) a stable dose of psychiatric medication for at least six weeks with no planned changes (or were medication free). Exclusion criteria included: (1) an unstable medical condition; (2) a current diagnosis of substance abuse/dependence; (3) a lifetime diagnosis of pervasive developmental disorder, mania, or psychosis; or (4) four or more previous sessions of behavior therapy for tics.

Participants were 119 individuals with TD (70 youth and 49 adults) who were 21 years of age on average (M = 21.76, SD = 14.08, range: 9 – 67 years) and predominantly male (n = 80, 67.2%). While there were no baseline differences between youth and adults on clinical characteristics, there was a small demographic difference regarding the preponderance of males between groups (V = .18, see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants by age group (N = 119).

| Characteristics | Overall | Adult | Child | Age-Group Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (SD) | mean (SD) | mean (SD) | p (t-test) | |

| Age in years | 21.76 (14.08) | 35.14 (12.85) | 12.39 (2.82) | |

| YGTSS Total Tic Score | 24.45 (6.43) | 23.82 (0.97) | 24.90 (0.74) | .516 |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p (X2) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 39 (32.8%) | 21 (42.9%) | 18 (25.7%) | .050 |

| Male | 80 (67.2%) | 28 (57.1%) | 52 (74.3%) | |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 96 (80.7%) | 39 (79.6%) | 57 (81.4%) | .701 |

| Non-Caucasian | 23 (19.3%) | 10 (20.4%) | 13 (18.6%) | |

| Medication Status | ||||

| On Tic Medications | 39 (37.9%) | 12 (29.3%) | 27 (43.5%) | .144 |

| No Medications | 64 (62.1%) | 29 (70.7%) | 35 (56.5%) | |

| Diagnoses | ||||

| Chronic Vocal Tic Disorder | 2 (1.7%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (1.4%) | -- |

| Chronic Motor Tic Disorder | 11 (9.2%) | 7 (14.3%) | 4 (5.7%) | |

| Tourette’s Disorder | 106 (89.1%) | 41 (83.7%) | 65 (92.9%) | |

| Co-occurring Conditions | ||||

| Anya | 65 (54.6%) | 23 (46.9%) | 42 (60%) | .159 |

| OCD | 20 (16.8%) | 10 (20.4%) | 10 (14.3%) | .379 |

| Anxiety Disordersb | 30 (25.2%) | 8 (16.3%) | 22 (31.4%) | .062 |

| ADHD | 35 (29.4%) | 14 (28.6%) | 21 (30%) | .866 |

Abbreviations: ADHD = Attention Deficit/Hyperactive Disorder; OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; YGTSS = Yale Global Tic Severity Scale.

Participants who met diagnostic criteria for any psychiatric conditions, including OCD, ADHD, anxiety and depressive disorders.

Generalized anxiety, social anxiety, separation anxiety, specific phobia, panic disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Measures

Diagnostic Interviews.

Participants completed a diagnostic interview to determine TD and co-occurring diagnoses. While most youth (n = 59, 49.58%) were administered the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS) for DSM-IV-TR: Child Version (Silverman & Albano, 1996), older adolescents and adults (n = 60, 50.42%) completed the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First & Spitzer, 1996) Both of these clinical interviews have good reliability and validity (First & Spitzer, 1996; Silverman et al., 2001; Wood et al., 2002).

Tic Severity.

Participants were administered the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) at baseline and post-treatment (Leckman et al., 1989). The YGTSS is a clinician-rated scale used to measure tic severity and produces a total tic score (range: 0 – 50). The YGTSS total tic score has shown good reliability, validity, and treatment sensitivity (Jeon et al., 2013; Leckman et al., 1989; McGuire et al., 2018; Storch et al., 2005, 2011), with good internal consistency observed across assessments (α = .75 – .85).

Treatment Response.

The Clinical Global Impressions of Improvement scale (CGI-I) was used to determine treatment response (Guy, 1976). The CGI-I is a clinician rating of global improvement in TD-related functioning relative to baseline on a 7-point scale (Cohen et al., 1988; Leckman et al., 1988), in which lower scores indicate symptom improvement and higher scores indicate worsening. Ratings of (1) very much improved or (2) much improved correspond with positive treatment response (Jeon et al., 2013; Storch et al., 2011).

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

The severity of ADHD symptoms was assessed using the Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder-Rating Scale (ADHD-RS; DuPaul et al., 1998). The ADHD-RS contains 18 items rated on a 4-point scale, and contains an inattention subscale (9-items) and a hyperactivity/impulsivity subscale (9-items). The ADHD-RS has good reliability and validity in youth and adults (McGuire, 2019; Scahill et al., 2001). The Inattention subscale (α = .93) and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity subscale (α = .87 – .89) both exhibited good internal consistency across assessments.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

The severity of OCD symptoms was captured using the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS; Goodman et al., 1989). The Y-BOCS is a clinician-administered scale that assesses OCD symptom type and severity and has a parallel version for youth (Scahill et al., 1997). The Y-BOCS total score consists of 10 items rated on a 5-point scale, with higher scores corresponding to greater OCD severity (range: 0 – 40). The Y-BOCS and its parallel child version have good reliability and validity (Goodman et al., 1989; Scahill et al., 1997), with excellent internal consistency observed across assessments (α = .93).

Externalizing Symptoms.

Externalizing symptoms were measured differently in youth and adults due to study design differences. The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) for ages 6 to 18 is a measure of general youth behavior that was completed by parents of youth in the child clinical trial (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1991). The CBCL produces two overall scores of Internalizing symptoms and Externalizing symptoms. The CBCL has excellent psychometric properties (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1979; Edelbrock & Achenbach, 1984). Meanwhile in the adult clinical trial, adults completed the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2nd edition (STAXI-2; Spielberger, 1988). The STAXI-2 is a reliable and valid self-report measure that consists of four scales: state anger, trait anger, anger expressions (with two subscales, inward and outward expression of anger), and anger control (with two subscales, inward and outward anger control). Higher scores reflect greater anger, anger expression, and reduced anger control (Lievaart et al., 2016; Spielberger, 1988). Good internal consistency was observed for all STAXI-2 subscales within the current sample (α = .75 – .93).

Family Functioning.

The Caregiver Strain Questionnaire (Brannan et al., 1997) was administered to caregivers of youth participants to assess the degree to which TD has negatively affected family functioning. The Caregiver Strain Questionnaire consists of 21 items rated on a 5-point scale, summing to a total score (Woods et al., 2011), with higher scores corresponding to greater strains on family functioning. Acceptable psychometric properties have been reported for this scale (Brannan et al., 1997), with good internal consistency found across assessments (α = .89 – .92).

Disability.

The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS; Leon et al., 1992) was administered to adults and older adolescents to assess work-, social-, and family-related disability. The SDS consists of three self-report items on a 10-point scale. It is reliable and valid, and has been used in treatment studies (Deckersbach et al., 2006; Leon et al., 1992).

Homework Adherence.

At each therapy session, therapists reviewed the homework assigned from the prior visit and rated adherence on a 7-point Likert scale using the following anchors: 1–2 (Poor Compliance, 1 = noncompliant), 3–5 (Intermediate Compliance, 4 = compliant about ½ the time), and 6–7 (Good Compliance, 7 = completely compliant). For example, Session 3 homework adherence rating would characterize a participant’s adherence with homework assigned at Session 2. Homework adherence ratings were extracted from sessions in which core behavior therapy skills were assigned (i.e., awareness training and competing response training) and averaged across relevant sessions. Overall homework adherence refers to the average across all therapy sessions (Session 2 through Session 8). Meanwhile, early homework adherence refers to the average homework adherence rating for early sessions (Session 2 through Session 5) and late homework adherence refers to the average rating for late therapy sessions (Session 6 through Session 8).

Procedures

Child recruitment occurred at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, the University of California Los Angeles, and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, with adults recruited from Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and Yale’s Child Study Center. Study procedures were approved by each local Institutional Review Board. Adult participants provided written consent, and youth participants provided assent while their parents provided written consent.

Participants completed a baseline assessment to characterize psychiatric diagnoses, tic severity, psychiatric comorbidity, and psychosocial functioning. Assessments were conducted by independent evaluators (IEs) who were masked to treatment, trained to reliability, and supervised using a structured protocol (Piacentini et al., 2010; Wilhelm et al., 2012). Afterward, participants received eight sessions of CBIT over 10 weeks from therapists who had masters-level or higher education. Prior to delivering treatment, therapists were systematically trained to deliver CBIT using treatment manuals (Woods et al., 2008) closely supervised over two training cases. After demonstrating adherence to the treatment protocol, therapists provided CBIT in the study and received weekly site-level and cross-site supervision. Training included completion of session summary sheets, which detailed therapeutic skills and homework adherence items. Therapy sessions were recorded and randomly selected to evaluate fidelity to the treatment protocol. There was good fidelity to the treatment protocol in both clinical trials (Piacentini et al., 2010; Wilhelm et al., 2012).

At each therapy session, therapists assigned homework according to the manualized treatment protocol (Woods et al., 2008), and documented homework assignments. Homework assignments typically involved 3 – 4 formal practice sessions of therapeutic skills that lasted about 30 minutes in duration, with informal practice of skill-use throughout daily life. At the following session, therapists reviewed with participants previously assigned homework, and discuss potential adjustment to improve skill implementation. Based on this information, therapists completed a session summary sheet in which participant’s homework adherence over the past week was rated. At the end of treatment, participants completed a post-treatment assessment where tic severity (YGTSS) and treatment response (CGI-I) were assessed by IEs. Please see Piacentini et al. (2010) and Wilhelm et al., (2012) for further information on assessment and treatment protocols.

Analytic plan

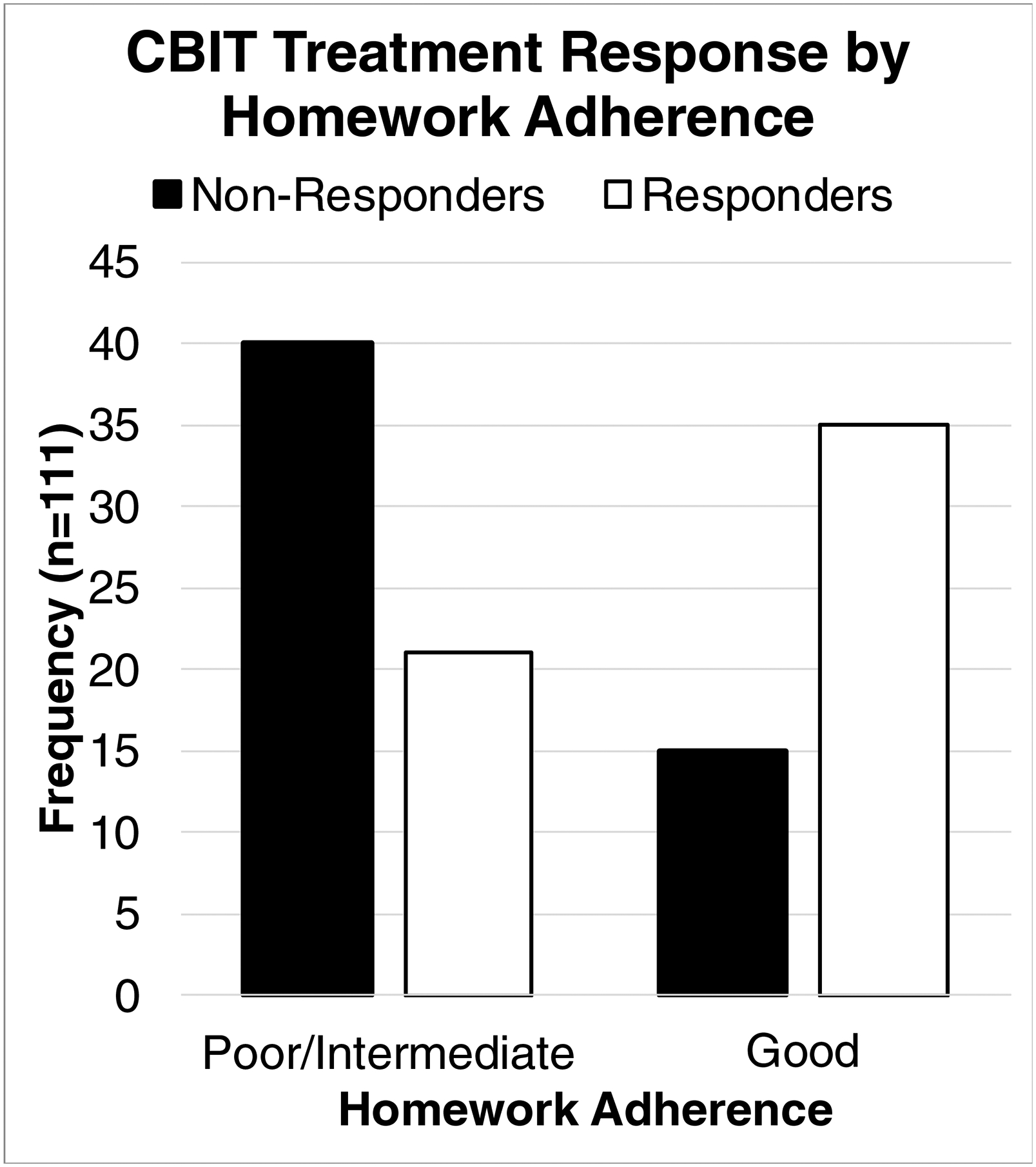

Eight participants (3 youth and 5 adults, 7.5%) discontinued behavior therapy, and were excluded from analyses. Additionally, four other participants (1 youth and 3 adults, 1.6%) had one or more missing late homework adherence ratings, but were included in early adherence analyses. First, descriptive statistics characterized the sample and homework adherence ratings. Chi-square tests and t-tests compared differences between age groups (youth and adults) in baseline demographic and clinical characteristics (e.g., sex, baseline YGTSS scores, co-occurring conditions; Table 1). Second, a repeated measures analysis of variance examined whether homework adherence differed across treatment visits. Third, linear regression models evaluated whether homework adherence ratings predicted tic severity reductions from baseline to post-treatment on YGTSS total tic scores. Additionally, logistic regression models examined whether homework adherence ratings predicted treatment response on the CGI-I. We explored whether dichotomized homework adherence (“good” adherence: score > 6; “intermediate/poor” adherence: ≤ 6) was associated with treatment response (Figure 1), as a simplified analysis of “Good” vs “Less Than Good” adherence may be preferrable for practitioners to discuss with patients during psychoeducation. Lastly, forward selection linear regression models investigated whether baseline clinical characteristics predicted homework adherence ratings.

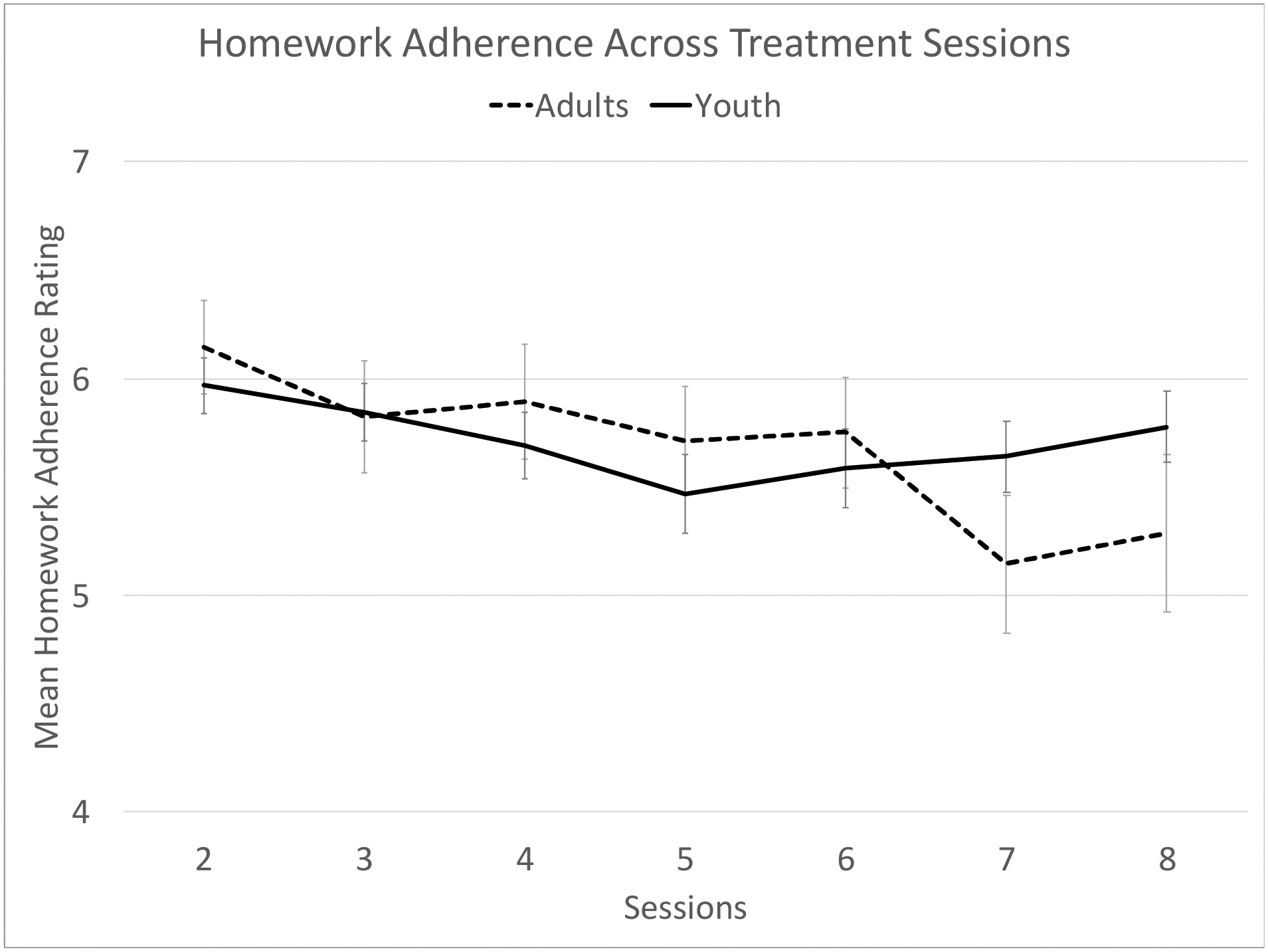

Figure 1. Averaged Homework Compliance Ratings Across Treatment Sessions.

Homework adherence was rated on a 7-point Likert scale using the following anchors 1 = Poor, 4 = Intermediate, and 7 = Very Good.

Results

Homework Adherence Across Behavior Therapy Sessions

Homework adherence changed across treatment visits and exhibited a different pattern for youth and adults (F4.5, 376.7 = 2.65, pη2 =.03, p =.028). For youth with TD, homework adherence exhibited a quadratic trend with a dip in adherence midway through treatment (F1,57 = 5.89, pη2 =.094, p =.018). Meanwhile, adults with TD exhibited a linear decline in homework adherence (F1,27 = 7.34, pη2 =.214, p =.012; see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Homework Adherence and Treatment Response.

Frequency of treatment response as organized by homework adherence categories.

Homework Adherence and Tic Severity Reductions

Overall homework adherence (β = .20, p =.037) predicted tic severity reductions on the YGTSS at the post-treatment assessment (R2 =.04, F1, 109 = 4.44, p =.037). When examining adherence between youth and adults, a different pattern emerged. Early homework adherence (β = .38, p =.058) showed a trend to predict tic severity reductions for youth with TD, whereas late homework adherence did not (p = .99; R2 =.14, F2,61 = 4.97, p =.01). Meanwhile for adults with TD, late homework adherence predicted tic severity reductions (β = .42, p =.036) but early homework adherence did not (p =.33; R2 =.11, F2,40 = 2.50, p = .10).

Homework Adherence and Treatment Response

Overall homework adherence (B =.71, OR =2.04, 95% CI: 1.31 – 3.19) predicted treatment response on the CGI-I (X2(111) = 12.21, p < .001). Given that a simplified analysis between “Good” versus “Less than Good” is clinically relevant, we explored whether dichotomized homework adherence was associated with treatment response. There was a significant association between treatment response and homework adherence (see Figure 1, χ2(1, N = 111) = 13.91, V = .35, p <.001). Participants with good homework adherence were more likely to exhibit a positive treatment response (70%) compared to those with intermediate/poor homework adherence (i.e., “Less than Good”, 34.4%).

Further logistic regressions that treats the adherence scale as a continuous variable revealed early and late homework adherence differentially predicted treatment response in youth and adults. For youth with TD, early homework adherence (B =1.05, p =.045, OR =2.86, 95% CI: 1.03 – 7.97) predicted treatment response, but late homework adherence did not (p =.96; X2(64) =10.67, p =.005). Meanwhile for adults with TD, late homework adherence (B =1.11, p =.023, OR =3.02, 95% CI: 1.17 – 7.81) predicted treatment response but early homework adherence did not (p =.31; X2(43) =9.16, p =.01).

Baseline Predictors of Early and Late Homework Adherence

In youth with TD, lower hyperactivity/impulsivity scores (β = −.394, p =.002) predicted greater early homework adherence (R2 =.140, F1,56 =10.28, p =.002). Additionally, reduced tic—related family strain (β = −.383, p =.004) predicted greater late homework adherence (R2 =.147, F1,52 =8.93, p =.004). No other baseline characteristics predicted early or late homework adherence over and above the aforementioned predictors (e.g., baseline OCD severity, inattention score on the ADHD-RS, CBCL externalizing score, baseline YGTSS total tic and impairment scores; p =.19–.74).

In adults with TD, lower trait anger scores (β = −.463, p =.003), less social disability (β = −.452, p =.009), and greater work disability (β =.543, p =.003) predicted greater early homework adherence in behavior therapy (R2 =.326, F3,37 =5.97, p =.002). Meanwhile, baseline predictors of greater late homework adherence (R2 =.618, F6,32 =11.26, p <.001) included younger age (β = −.312, p =.004), greater work disability (β =.62., p <.001), lower social disability (β = −.606, p <.001), lower OCD severity (β = −.432, p <.001), lower ADHD hyperactivity/impulsivity scores (β = −.543, p =.001), and lower outward anger expression score (β = −.611, p <.001). No other baseline characteristics predicted early or late homework adherence over and above the aforementioned predictors (e.g., all other STAXI-2 scales and subscales, inattention score on the ADHD-RS, YGTSS total tic score, and YGTSS Impairment score; p =.16–.99).

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between homework adherence and therapeutic improvement from behavior therapy and investigated baseline predictors of homework adherence among individuals with TD. Increased adherence to behavior therapy homework predicted greater reductions in tic severity and positive treatment response. Participants with good homework adherence were more likely to display a positive treatment response compared to those with intermediate (or less) homework adherence. These findings highlight the importance of homework adherence in behavior therapy and suggest that treatment outcomes may be improved if homework adherence were optimized. However, strategies to enhance homework adherence during behavior therapy may likely differ between youth and adults. In youth with TD, homework adherence may be strengthened by the use of behavioral reward systems to reinforce the practice of behavior therapy skills. This can help maintain good homework adherence throughout behavior therapy, and particularly midway through treatment when adherence appears to diminish among youth. Meanwhile for adults with TD, greater homework adherence may be achieved by framing skill practice in relation to the individual’s treatment goals and values. This may help adults with TD to persist in practicing behavioral skills throughout treatment course, despite any setbacks, tic exacerbations, and/or other related challenges that may emerge. This may explain in part the predictive relationship between late homework adherence and improved therapeutic outcomes among adults with TD. While these two strategies may contribute to enhanced utilization of behavior therapy skills, the inclusion of a social support person (e.g., parent or partner) is important to provide corrective feedback on accurate tic detection (awareness training) and inhibition (competing response training) during homework activities.

When examining baseline predictors of homework adherence, greater hyperactivity/impulsivity scores (but not inattention scores) predicted lower homework adherence across youth and adults. This is consistent with previous research in anxiety and OCD, and may explain prior findings linking the presence of co-occurring ADHD with attenuated benefit from behavior therapy (McGuire et al., 2014). During practice sessions, patients are often stationary and seated across from the social support person in order to facilitate tic observation and correct competing response implementation. Patients with greater hyperactivity/impulsivity may find it more challenging to be sedentary while practicing therapeutic skills and/or difficult to implement competing responses that temporarily immobilize parts of the body (e.g., crossing arms to inhibit an arm tic also prevents fidgeting). Therefore, therapists may develop between-session homework practice activities specifically for non-sedentary settings (e.g., while taking walks or doing chores) and/or assign homework practice during periods of reduced hyperactivity/impulsivity (e.g., after physical exercises, when ADHD medication is at peak effectiveness). Although further research is needed to clarify the precise mechanism by which hyperactivity/impulsivity impedes homework adherence, the aforementioned strategies may prove useful to improve homework adherence in the interim.

Beyond hyperactivity/impulsivity, family and social functioning emerged as possible common negative predictors of homework adherence between youth and adults. In youth with TD, greater strain on family functioning was associated with reduced homework adherence in later therapy sessions. While parents may initially be involved and motivated early in treatment, families with more dysfunction and/or burden appear to have greater difficulty maintaining adherence over time (e.g., parents may no longer have the capacity to practice with youth, behavioral reward system adherence may decline among parents). Meanwhile in adults with TD, greater social disability and anger was associated with lower homework adherence. Although seemingly different from youth, the central cause for lower homework adherence may be the same. Adults with greater social disability and anger would likely have greater difficulty interacting with a social support person (e.g., partner, friend) to practice behavior therapy skills or may even lack a social support person altogether. These homework exercises could be further complicated when the social support person provides corrective feedback on tic detection and/or implementation of competing responses—eliciting anger and frustration from the patient who is trying to appropriately implement skills. Given that baseline predictors of homework adherence appear to relate to social support, innovative solutions are needed to overcome this challenge. For instance, therapists may seek to address these baseline homework adherence barriers with social support persons at the outset of treatment.

Lastly for adults with TD, greater work disability predicted greater homework adherence throughout treatment. This suggests that adults whose tics cause greater occupational interference may be more motivated to practice behavior therapy skills between sessions or may have more time available to complete homework assignments. As behavior therapy for TD can improve functional outcomes (e.g., work disability, social disability; McGuire, 2019) these adults may experience practical benefits from homework adherence that serve to reinforce regular skill use. For instance, an adult with TD who regularly practices behavior therapy skills at work and/or in social settings may experience fewer problems at work and/or in social situations due to tics. These positive experiences (i.e. fewer problems) would serve to reinforce skill practice and use in the patient’s natural environment.

Despite several methodological strengths of this study, a few limitations remain. First, we did not capture all possible demographic and clinical characteristics for baseline predictors of homework adherence. Therefore, there may be unexamined characteristics that influence homework adherence that warrant further examination. On balance, measures of common co-occurring psychiatric conditions and key aspects of psychosocial functioning were included that would connect findings to standard clinical care. Second, while the YGTSS and CGI-I are gold-standard measures of tic severity and treatment response in clinical trials, reliance on a single measure may unintentionally inflate response rates (Loerinc et al., 2015). Although this is an unlikely concern due to the many precautions taken in these multisite clinical trials (e.g., IE training and on-going monitoring), future trials should consider additional parameters to classify treatment response (e.g., multiple outcome measures, reliable change indices). Third, ratings of homework adherence were entirely reliant on therapists’ report. While therapists had considerable contact with patients and social support persons, there was no objective measure of behavior therapy homework adherence between sessions. Future research should incorporate objective measures of homework adherence (e.g., time stamped video recording homework practices).

In summary, homework adherence predicts tic severity reductions and treatment response to behavior therapy in youth and adults with TD. Findings support the importance of between-session practice of behavior therapy skills for patients to exhibit therapeutic benefit. Therapists should emphasize the importance of homework adherence between therapy sessions during psycho-education, and implement strategies to optimize homework adherence early on in treatment (e.g., implementation of a behavioral reward system, connecting skill practice to goals and values). When baseline predictors of reduced homework adherence are present (e.g., greater hyperactivity/impulsivity, impediments to participation of the social support person), therapists should implement strategies to compensate for these challenges and revise treatment plans accordingly (e.g., discussions with social support person regarding homework implementation). While these suggestions are based on clinical experience, future research should investigate empirical approaches to optimize homework adherence for individuals with TD. Strategies that optimize homework adherence may enhance the efficacy of behavioral therapy, lead to greater tic severity reductions, and higher treatment response rates. Indeed, this may be most relevant for patients with TD who experience greater inattention/hyperactivity and/or have a clinical presentation that may impede the involvement of a social support person in treatment.

Highlights.

Behavior therapy is a first-line evidence-based treatment for Tourette’s Disorder

Behavior therapy homework adherence predicted tic severity reductions

Hyperactivity/impulsivity and social support predicted homework adherence

Behavior therapy homework adherence differed slightly between youth and adults

Strategies to improve homework adherence could optimize behavior therapy outcomes

Funding:

This work was supported in part by Tourette Association of America (to Dr. Essoe), the National Institutes of Mental Health [grant numbers K23MH113884 (to Dr. Ricketts), R01MH070802 (to Dr. Piacentini), R01MH69875 (to Dr. Peterson), R01MH069874 (to Dr. Scahill), R01MH069877 (to Dr. Wilhelm)], American Academy of Neurology (to Dr. McGuire), and American Psychological Foundation (to Dr. McGuire). Declarations of interest: none.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abramowitz JS, Franklin ME, Zoellner LA, & Dibernardo CL (2002). Treatment Compliance and Outcome in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Behavior Modification, 26(4), 447–463. 10.1177/0145445502026004001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Edelbrock C (1991). Child behavior checklist. Burlington (Vt), 7, 371–392. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Edelbrock CS (1979). The Child Behavior Profile: II. Boys aged 12–16 and girls aged 6–11 and 12–16. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47(2), 223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand N, Sudhir PM, Math SB, Thennarasu K, & Janardhan Reddy YC (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy in medication non-responders with obsessive–compulsive disorder: A prospective 1-year follow-up study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(7), 939–945. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azrin NH, & Peterson AL (1990). Treatment of Tourette syndrome by habit reversal: A waiting-list control group comparison. Behavior Therapy, 21(3), 305–318. [Google Scholar]

- Brannan AM, Heflinger CA, & Bickman L (1997). The Caregiver Strain Questionnaire: Measuring the Impact on the Family of Living with a Child with Serious Emotional Disturbance. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 5(4), 212–222. 10.1177/106342669700500404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cammin-Nowak S, Helbig-Lang S, Lang T, Gloster AT, Fehm L, Gerlach AL, Ströhle A, Deckert J, Kircher T, Hamm AO, Alpers GW, Arolt V, & Wittchen H-U (2013). Specificity of Homework Compliance Effects on Treatment Outcome in CBT: Evidence from a Controlled Trial on Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(6), 616–629. 10.1002/jclp.21975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti S (2014). What’s in a name? Compliance, adherence and concordance in chronic psychiatric disorders. World Journal of Psychiatry, 4(2), 30–36. 10.5498/wjp.v4.i2.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloes KI, Barfell KSF, Horn PS, Wu SW, Jacobson SE, Hart KJ, & Gilbert DL (2017). Preliminary evaluation of child self-rating using the Child Tourette Syndrome Impairment Scale. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 59(3), 284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DJ, Bruun RDE, & Leckman JF (1988). Tourette’s syndrome and tic disorders: Clinical understanding and treatment. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Conelea CA, Woods DW, Zinner SH, Budman CL, Murphy TK, Scahill LD, Compton SN, & Walkup JT (2013). The impact of Tourette syndrome in adults: Results from the Tourette syndrome impact survey. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(1), 110–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conelea CA, Woods DW, Zinner SH, Budman C, Murphy T, Scahill LD, Compton SN, & Walkup J (2011). Exploring the impact of chronic tic disorders on youth: Results from the Tourette Syndrome Impact Survey. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 42(2), 219–242. PsycINFO. 10.1007/s10578-010-0211-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings CM, Kazantzis N, & Kendall PC (2014). Facilitating Homework and Generalization of Skills to the Real World. In Sburlati ES, Lyneham HJ, Schniering CA, & Rapee RM (Eds.), Evidence-Based CBT for Anxiety and Depression in Children and Adolescents (pp. 141–155). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 10.1002/9781118500576.ch11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deckersbach T, Rauch S, Buhlmann U, & Wilhelm S (2006). Habit reversal versus supportive psychotherapy in Tourette’s disorder: A randomized controlled trial and predictors of treatment response. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(8), 1079–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, & Reid R (1998). ADHD Rating Scale-IV: Checklists, norms, and clinical interpretation (Vol. 25). Guilford Press; New York. [Google Scholar]

- Edelbrock CS, & Achenbach TM (1984). The teacher version of the Child Behavior Profile: I. Boys aged 6–11. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52(2), 207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essoe JK-Y, Grados MA, Singer HS, Myers NS, & McGuire JF (2019). Evidence-based treatment of Tourette’s disorder and chronic tic disorders. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 1–13. 10.1080/14737175.2019.1643236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, & Spitzer RL (1996). Gibbon Miriam, and Williams, Janet BW Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-CV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman RD, Fast DK, Burd L, Kerbeshian J, Robertson MM, & Sandor P (2000). An international perspective on Tourette syndrome: Selected findings from 3500 individuals in 22 countries. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 42(7), 436–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Delgado P, Heninger GR, & Charney DS (1989). The yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale: II. Validity. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46(11), 1012–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W (1976). Clinical global impressions-ECDEU Asessment manual psychopharmacology (DHEW Publ no ADM 76–338). In.: Revised. Rockville MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, NIMH. [Google Scholar]

- Hanks CE, McGuire JF, Lewin AB, Storch EA, & Murphy TK (2016). Clinical correlates and mediators of self-concept in youth with chronic tic disorders. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 47(1), 64–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AA, & Kendall PC (2007). Prediction of cognitive behavior treatment outcome for children with anxiety disorders: Therapeutic relationship and homework compliance. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 35(4), 487–494. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon S, Walkup JT, Woods DW, Peterson A, Piacentini J, Wilhelm S, Katsovich L, McGuire JF, Dziura J, & Scahill L (2013). Detecting a clinically meaningful change in tic severity in Tourette syndrome: A comparison of three methods. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 36(2), 414–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazantzis N, Brownfield NR, Mosely L, Usatoff AS, & Flighty AJ (2017). Homework in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Systematic Review of Adherence Assessment in Anxiety and Depression (2011–2016). Psychiatric Clinics, 40(4), 625–639. 10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazantzis N, & Lampropoulos GK (2002). Reflecting on homework in psychotherapy: What can we conclude from research and experience? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(5), 577–585. 10.1002/jclp.10034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazantzis N, Whittington C, Zelencich L, Kyrios M, Norton PJ, & Hofmann SG (2016). Quantity and Quality of Homework Compliance: A Meta-Analysis of Relations With Outcome in Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Behavior Therapy, 47(5), 755–772. 10.1016/j.beth.2016.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Riddle MA, Hardin MT, Ort SI, Swartz KL, Stevenson J, & Cohen DJ (1989). The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: Initial Testing of a Clinician-Rated Scale of Tic Severity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(4), 566–573. 10.1097/00004583-198907000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman J, Towbin K, Ort S, & Cohen D (1988). Clinical assessment of tic disorder severity. Tourette’s Syndrome and Tic Disorders. New York: John Wiley, 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Leeuwerik T, Cavanagh K, & Strauss C (2019). Patient adherence to cognitive behavioural therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 68, 102135. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2019.102135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Shear MK, Portera L, & Klerman GL (1992). Assessing impairment in patients with panic disorder: The Sheehan Disability Scale. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 27(2), 78–82. 10.1007/BF00788510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievaart M, Franken IHA, & Hovens JE (2016). Anger Assessment in Clinical and Nonclinical Populations: Further Validation of the State–Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72(3), 263–278. 10.1002/jclp.22253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loerinc AG, Meuret AE, Twohig MP, Rosenfield D, Bluett EJ, & Craske MG (2015). Response rates for CBT for anxiety disorders: Need for standardized criteria. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 72–82. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher MJ, Wang Y, Zuckoff A, Wall MM, Franklin M, Foa EB, & Simpson HB (2012). Predictors of Patient Adherence to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 81(2), 124–126. 10.1159/000330214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Moore R, Roesch S, Cardenas V, & Patterson TL (2010). The Relationship Between Homework Compliance and Therapy Outcomes: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34(5), 429–438. 10.1007/s10608-010-9297-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire. (2019). Effect of behavior therapy for Tourette’s disorder on psychiatric symptoms and functioning in adults. Psychological Medicine, 1–11. 10.1017/S0033291719002150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JF, Piacentini J, Brennan EA, Lewin AB, Murphy TK, Small BJ, & Storch EA (2014). A meta-analysis of behavior therapy for Tourette Syndrome. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 50, 106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JF, Piacentini J, Storch EA, Murphy TK, Ricketts EJ, Woods DW, Walkup JW, Peterson AL, Wilhelm S, & Lewin AB (2018). A multicenter examination and strategic revisions of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale. Neurology, 90(19), e1711–e1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JF, Ricketts EJ, Scahill L, Wilhelm S, Woods DW, Piacentini J, Walkup JT, & Peterson AL (2020). Effect of behavior therapy for Tourette’s disorder on psychiatric symptoms and functioning in adults. Psychological Medicine, 50(12), 2046–2056. 10.1017/S0033291719002150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy TK, Lewin AB, Storch EA, & Stock S (2013). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with tic disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(12), 1341–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Rosenfield D, Monzani B, Krebs G, Heyman I, Turner C, Isomura K, & Mataix-Cols D (2015). Effects of Homework Compliance on Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy with D-Cycloserine Augmentation for Children with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 32(12), 935–943. 10.1002/da.22423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JM, Small BJ, Geller DA, Murphy TK, Lewin AB, & Storch EA (2014). Does d-Cycloserine Augmentation of CBT Improve Therapeutic Homework Compliance for Pediatric Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(5), 863–871. 10.1007/s10826-013-9742-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson AL, McGuire JF, Wilhelm S, Piacentini J, Woods DW, Walkup JT, Hatch JP, Villarreal R, & Scahill L (2016). An empirical examination of symptom substitution associated with behavior therapy for Tourette’s Disorder. Behavior Therapy, 47(1), 29–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini J, Woods DW, Scahill L, Wilhelm S, Peterson AL, Chang S, Ginsburg GS, Deckersbach T, Dziura J, Levi-Pearl S, & Walkup JT (2010). Behavior therapy for children with Tourette disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 303(19), 1929–1937. 10.1001/jama.2010.607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringsheim T, Okun MS, Müller-Vahl K, Martino D, Jankovic J, Cavanna AE, Woods DW, Robinson M, Jarvie E, & Roessner V (2019). Practice guideline recommendations summary: Treatment of tics in people with Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders. Neurology, 92(19), 896–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, Ort SI, King RA, Goodman WK, Cicchetti D, & Leckman JF (1997). Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: Reliability and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(6), 844–852. 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill Lawrence, Chappell PB, Kim YS, Schultz RT, Katsovich L, Shepherd E, Arnsten AF, Cohen DJ, & Leckman JF (2001). A placebo-controlled study of guanfacine in the treatment of children with tic disorders and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill Lawrence, Specht M, & Page C (2014). The prevalence of tic disorders and clinical characteristics in children. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, 3(4), 394–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill Lawrence, Woods DW, Himle MB, Peterson AL, Wilhelm S, Piacentini JC, McNaught K, Walkup JT, & Mink JW (2013). Current controversies on the role of behavior therapy in Tourette syndrome. Movement Disorders, 28(9), 1179–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, & Woolaway-Bickel K (2000). The effects of treatment compliance on outcome in cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder: Quality versus quantity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(1), 13–18. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.1.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, & Albano AM (1996). The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-Child and Parent Versions. Graywinds Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman Wendy K., Saavedra LM, & Pina AA (2001). Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV : Child and parent versions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(8), 937–944. 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson HB, Maher MJ, Wang Y, Bao Y, Foa EB, & Franklin M (2011). Patient adherence predicts outcome from cognitive behavioral therapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(2), 247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD (1988). Manual for the state-trait anger expression scale (STAXI). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Steeves T, McKinlay BD, Gorman D, Billinghurst L, Day L, Carroll A, Dion Y, Doja A, Luscombe S, & Sandor P (2012). Canadian guidelines for the evidence-based treatment of tic disorders: Behavioural therapy, deep brain stimulation, and transcranial magnetic stimulation. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57(3), 144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Merlo LJ, Lack C, Milsom VA, Geffken GR, Goodman WK, & Murphy TK (2007). Quality of life in youth with Tourette’s syndrome and chronic tic disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36(2), 217–227. 10.1080/15374410701279545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch Eric A., De Nadai AS, Lewin AB, McGuire JF, Jones AM, Mutch PJ, Shytle RD, & Murphy TK (2011). Defining treatment response in pediatric tic disorders: A signal detection analysis of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 21(6), 621–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch Eric A., Murphy TK, Geffken GR, Sajid M, Allen P, Roberti JW, & Goodman WK (2005). Reliability and validity of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale. Psychological Assessment, 17(4), 486–491. 10.1037/1040-3590.17.4.486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdellen C, Van De Griendt J, Hartmann A, Murphy T, & ESSTS Guidelines Group. (2011). European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Part III: behavioural and psychosocial interventions. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 20(4), 197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra HA, & Dozois DJA (2006). Preparing Clients for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Randomized Pilot Study of Motivational Interviewing for Anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 30(4), 481–498. 10.1007/s10608-006-9016-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Westra HA, Dozois DJA, & Marcus M (2007). Expectancy, homework compliance, and initial change in cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(3), 363–373. 10.1037/0022-006X.75.3.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherell JL, Hopko DR, Diefenbach GJ, Averill PM, Beck JG, Craske MG, Gatz M, Novy DM, & Stanley MA (2005). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for late-life generalized anxiety disorder: Who gets better? Behavior Therapy, 36(2), 147–156. 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80063-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton MG, & Chen SR (2020). Homework Completion in Treating Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder with Exposure and Ritual Prevention: A Review of the Empirical Literature. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 10.1007/s10608-020-10125-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton MG, Galfalvy H, Steinman SA, Wall MM, Foa EB, & Simpson HB (2016). Patient adherence and treatment outcome with exposure and response prevention for OCD: Which components of adherence matter and who becomes well? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 85, 6–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm S, Peterson AL, Piacentini J, Woods DW, Deckersbach T, Sukhodolsky DG, Chang S, Liu H, Dziura J, & Walkup JT (2012). Randomized trial of behavior therapy for adults with Tourette syndrome. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(8), 795–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Piacentini JC, Bergman RL, McCracken J, & Barrios V (2002). Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: child and parent versions. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31(3), 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods CM, Chambless DL, & Steketee G (2002). Homework Compliance and Behavior Therapy Outcome for Panic with Agoraphobia and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 31(2), 88–95. 10.1080/16506070252959526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DW, Piacentini J, Chang SW, Deckersbach T, Ginsburg GS, Peterson AL, Scahill LD, Walkup JT, & Wilhelm S (2008). Managing Tourette Syndrome: A Behavioral Intervention for Children and Adolescents. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woods Douglas W., Piacentini JC, Scahill L, Peterson AL, Wilhelm S, Chang S, Deckersbach T, McGuire J, Specht M, & Conelea CA (2011). Behavior therapy for tics in children: Acute and long-term effects on psychiatric and psychosocial functioning. Journal of Child Neurology, 26(7), 858–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody SR, & Adessky RS (2002). Therapeutic alliance, group cohesion, and homework compliance during cognitive-behavioral group treatment of social phobia. Behavior Therapy, 33(1), 5–27. 10.1016/S0005-7894(02)80003-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MS, Caporino NE, Peris TS, Pérez J, Thamrin H, Albano AM, Kendall PC, Walkup JT, Birmaher B, Compton SN, & Piacentini J (2020). The Impact of Treatment Expectations on Exposure Process and Treatment Outcome in Childhood Anxiety Disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48(1), 79–89. 10.1007/s10802-019-00574-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]