Abstract

Curiosity and intent to use alcohol in pre-adolescence is a risk factor for later experimentation and use, yet we know little of how curiosity about use develops. Here, we examine factors that may influence curiosity around alcohol use, as it may be an important predictor of later drinking behavior. Cross-sectional data on youth ages 10–11 from the ongoing Adolescent Brain Cognitive DevelopmentSM (ABCD) Study Year 1 follow-up were used (n=2,334; NDA 2.0.1). All participants were substance-naïve at time of assessment. Group factor analysis identified latent factors across common indicators of risk for early substance use (i.e., psychopathology and trait characteristics; substance use attitudes/behaviors; neurocognition; family and environment). Logistic mixed-effect models tested associations between latent factors of risk for early substance use and curiosity about alcohol use, controlling for demographics and study site. Two multidimensional factors were significantly inversely and positively associated with greater curiosity about alcohol use, respectively: (1) low internalizing and externalizing symptomatology coupled with low impulsivity, perceived neighborhood safety, negative parental history of alcohol use problems, and fewer adverse life experiences and family conflict; and (2) low perceived risk of alcohol use coupled with lack of peer disapproval of use. When assessing all risk factors in an overall regression, lack of perceived harm from trying alcohol once or twice was associated with greater likelihood of alcohol curiosity. Taken together, perceptions that alcohol use causes little harm and having peers with similar beliefs is related to curiosity about alcohol use among substance-naïve 10–11 year-olds. General mental health and environmental risk factors similarly increase the odds of curiosity for alcohol. Identification of multidimensional risk factors for early alcohol use may point to novel prevention and early intervention targets. Future longitudinal investigations in the ABCD cohort will determine the extent to which these factors and curiosity predict alcohol use among youth.

Keywords: Alcohol, intent to use, alcohol curiosity, pre-adolescent, children

Introduction

The brain is highly vulnerable to substance exposure during adolescence, leading to potential changes that may influence later life outcomes (Spear, 2013). Despite the known deleterious impact of substance use on neuromaturation, nearly 60% of high school seniors report lifetime alcohol use (Johnston et al., 2020). Concurrently, adolescents’ perception of harm of regular alcohol use is declining (Johnston et al., 2019). Shifting attitudes towards alcohol and other substance use may contribute to a greater willingness to experiment with substance use in youth. Importantly, curiosity and intent to use substances (and, particularly, tobacco) during pre-adolescence is a risk factor for later experimentation and use (Choi, Gilpin, Farkas, & Pierce, 2001; Nodora et al., 2014; Strong et al., 2015); childhood reports of curiosity may increase the likelihood of later substance use initiation two-fold (Pierce, Choi, Gilpin, Farkas, & Merritt, 1996) and significantly increase sensitivity when added to risk profile predictors (Nodora et al., 2014; Strong et al., 2015). However, there has been little investigation of contributors to the development of curiosity, despite the fact that curiosity has been identified as a leading reason why individuals initiate substance use (Guo, Unger, Azen, MacKinnon, & Johnson, 2012; Guo, Unger, Palmer, Chou, & Johnson, 2013) and precedes intention to use (Pierce, Distefan, Kaplan, & Gilpin, 2005). Here we examine factors that may influence curiosity about alcohol use in children 10–11 years of age, as it may be an important predictor of later drinking behavior.

Curiosity has been described as being driven by internal motivation for external stimulation, learning, and receiving information (Giambra, Camp, & Grodsky, 1992; Grossnickle, 2014). Consistent with this, functional neuroimaging data suggest curiosity is broadly related to neural processing (e.g., nucleus accumbens, frontal brain regions) underlying reward-based learning and decision-making abilities (Gruber, Gelman, & Ranganath, 2014; Kang et al., 2009). Notably, satisfaction of curious thoughts (i.e., receiving information) has been shown to increase activity in striatal brain regions (Jepma, Verdonschot, van Steenbergen, Rombouts, & Nieuwenhuis, 2012). As information acts as a reward, it has been suggested that curiosity leads to reward-motivated behaviors (Marvin & Shohamy, 2016). Relatedly, reward processing and decision-making are also key factors in risk of substance use onset (Casey et al., 2011; MacKillop et al., 2011). Together, this suggests decision-making and reward processing are likely linked to both curiosity and substance use risk.

Thus far, research on substance-related curiosity has focused on (1) tobacco use (Gentzke, Wang, Robinson, Phillips, & King, 2019; Guo et al., 2013; Nodora et al., 2014; Pierce et al., 2005), (2) adolescents (Guo et al., 2013; Pierce, Choi, Gilpin, Farkas, & Merritt, 1996), and (3) curiosity as a predictor of future substance use (Guo et al., 2013; Nodora et al., 2014; Pierce et al., 2005), rather than factors that contribute to development of curiosity in childhood. Curiosity about nicotine in early adolescence is a significant predictor of later use in adolescence/young adulthood in numerous studies. For example, Nodora and colleagues (2014) found inclusion of a tobacco curiosity question substantially increased their ability to identify 10–13 year-olds who would transition to tobacco use by 19 (from 25% to 45%). A study of over 12,000 middle and high school students in China found that curiosity about tobacco use predicted experimentation with tobacco one year later (Guo et al., 2013). Similarly, curiosity has been shown to precede intention to use tobacco in adolescents. A three year longitudinal study found that among 12–15 year-olds those who reported any tobacco curiosity at baseline were most likely to later engage in use (Pierce et al., 2005), which suggests curiosity may be one of the earliest markers of risk for later substance initiation. This is important as curiosity and intent to use substances in pre-adolescence is a risk factor for later experimentation and use (Choi et al., 2001; Nodora et al., 2014; Strong et al., 2015), though a wide range of other risk factors have been noted. More research is needed examining if development of curiosity about other substances (e.g., alcohol) may be an important marker for even earlier implementation of prevention efforts.

Efforts have been made to identify the most sensitive and specific predictors of who will later initiate substance use in early adolescence, with numerous possible risk factors suggested (see (Clark & Winters, 2002). Individual risk factors across several domains have been identified in longitudinal studies examining adolescent cohorts transitioning to alcohol use by later adolescence or young adulthood and include: (1) personality traits (e.g., sensation seeking, impulsivity) (Sargent, Tanski, Stoolmiller, & Hanewinkel, 2010) and psychopathology (e.g., externalizing symptoms; Gorka et al., 2014; Heron et al., 2013); (2) attitudes and peer influences about alcohol use (Maggs, Staff, Patrick, Wray-Lake, & Schulenberg, 2015; Donovan & Molina, 2011); (3) family and environmental influences (e.g., conflict, engagement, alcohol exposure; Donovan & Molina, 2011; Gorka et al., 2014; Hayatbakhsh et al., 2008; Sargent, Wills, Stoolmiller, Gibson, & Gibbons, 2006); and (4) neurocognitive vulnerabilities (e.g., response inhibition, decision making; Audrain-McGovern et al., 2009; MacKillop et al., 2011). More broadly, many of these risk factors also often relate to increased real-world risk taking and impaired decision-making, shaping behavioral and clinical outcomes (Isles, Winstanley, & Humby, 2019).

While understanding risk factors for use is important, the current literature is hampered by often using pre-post data to assess factors of those who have already initiated use. Identification of intermediary time points of higher risk prior to the onset of use may prevent some of the detrimental effects of later substance initiation. As curiosity has already been shown to be a unique and clinically significant predictor of later tobacco use (Nodora et al., 2014), it stands to reason that other substance use, such as alcohol use, may similarly be identified by curiosity. Better knowledge around alcohol curiosity predictors may lead to the development of targeted prevention efforts that can be utilized at the onset of curiosity, rather than the onset of alcohol use. Understanding factors across domains that relate to increased curiosity in pre-adolescent youth prior to substance use initiation may inform early assessment and intervention approaches (Choi et al., 2001; Nodora et al., 2014; Strong et al., 2015). Remarkably, the relationship between identified risk factors for alcohol initiation and alcohol curiosity, a potential antecedent to alcohol use, have not been investigated. Therefore, this investigation was designed to fill a gap in the literature and broadly investigate factors that influence curiosity about alcohol use in pre-adolescent youth ages 10–11. Using a data-driven process, we include relevant variables across domains and supported by previous studies (Clark & Winters, 2002; Donovan & Molina, 2011; Maggs et al., 2015; Sargent et al., 2010) that may be risk factors for curiosity about alcohol use to create latent factors. We hypothesize that high levels of these empirically derived latent factors will predict increased odds of curiosity about alcohol use.

Methods

Participants and their parents completed baseline (ages 9–10) and 1-Year follow-up (ages 10–11) assessments in the ABCD Study®, a 21-site 10-year longitudinal study with 11,880 participants funded by the National Institutes of Health (Volkow et al., 2018). They were assessed on a range of behavioral, psychosocial, and cognitive risk factors related to early substance use experiences and curiosity about alcohol use. Cross-sectional data from ABCD Data Release 2.0.1 was used, containing the first half of the Year 1 follow-up data. Data in the 2.0.1 release contained available data from 4,951 participants, of which 2,334 participants were included in the present analyses as they had never used alcohol and had no missing data on key variables. All aspects of the ABCD protocol were approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Recruitment and ABCD Procedures.

In brief, 9–10-year-olds were recruited primarily through probability-based sampling of schools, guided by epidemiological research to match United States census data (Barch et al., 2018; Casey et al., 2018; Garavan et al., 2018; Lisdahl et al., 2018; Luciana et al., 2018; Volkow et al., 2018; Zucker et al., 2018). Participants were excluded from baseline study participation if they had MRI contraindications, were outside the recruitment catchment area, or did not fall within the correct age range. Following a brief eligibility interview to ensure these characteristics, participants and a parent/guardian presented at their local research site and provided written assent/consent. Families were compensated for their time. ABCD participant compensation is determined by each local research site and os varies. Compensation amounts are higher during longer visits (e.g., imaging visits). On average, participants are compensated roughly $20 per hour for their time, with parents separately compensated a similar amount.

Measures.

Full description of neurocognitive, substance use, psychosocial, and other questionnaires are described elsewhere (Barch et al., 2018; Lisdahl et al., 2018; Luciana et al., 2018; Zucker et al., 2018). Briefly, 27 variables were included as potential risk-factors for curiosity about alcohol use from the 14 measures below, spanning 4 domains:

Psychopathology and Trait Characteristics.

Childhood Behavior Checklist (CBCL)—

Parents completed the CBCL to answer questions regarding their child’s mental health. Here, the normed externalizing and internalizing subscales are used. Higher externalizing symptoms reflect behavioral and disruptive social disturbances, while higher internalizing symptoms reflect greater mood and anxiety difficulties.

BIS/BAS.

The Behavioral Inhibition Scale and Behavioral Activation Scale (Carver & White, 1994) was administered to youth at baseline. It consisted of 24 items which gave four subscales: Drive, Fun Seeking, Reward Responsiveness and Behavioral Inhibition.

UPPS-P Youth Short Version—

A modified version of the UPPS (urgency, perseverance, premeditation, and sensation seeking) was created for ABCD (Barch et al., 2018; Lynman, 2013; Zapolski, Stairs, Settles, Combs, & Smith, 2010). It included 20 items, answered by youth participants, and provided five subscales: Negative Urgency, Positive Urgency, Lack of Perseverance, Lack of Planning, and Sensation Seeking.

Substance-Related Behaviors and Attitudes

Early Substance Use.

Youth reported their earliest alcohol sipping experiences using the iSay Sip Inventory (Jackson, Barnett, Colby, & Rogers, 2015). Quantity of alcohol sips were calculated. If a participant had tried alcohol, they were not asked about their curiosity regarding alcohol use; therefore, this measure was used as a means of ensuring inclusion criteria. At Year 1, 1,227 participants had reported using alcohol and so were excluded from analyses.

Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Intention to Use.

The PATH Inventory measures a child’s curiosity and intention to use cigarettes (Hyland et al., 2017; Pierce et al., 1996) and has been expanded to include alcohol and cannabis (Lisdahl et al., 2018). Only participants who have heard of the drug but not yet experimented with that drug were administered the PATH questionnaire. Participants were asked “Have you ever been curious about drinking alcohol?” and rated their curiosity for alcohol use on a 4-point Likert scale (“Very Curious”, “Somewhat Curious”, “A Little Curious”, and “Not At All Curious”). Given limited variability in reporting and consistent with prior studies of curiosity (Nodora et al., 2014), participant report was adjusted to a binary variable, where “Not At All Curious” = 0 and all other reporting (a little, somewhat, or very) = 1.

Peer Substance Use.

Tolerance of Use (Peer Disapproval). Participants were asked if their friends would strongly disapprove (scored as 2), disapprove (scored as 1), or not disapprove (scored as 0) of their alcohol use at three levels: trying alcohol once or twice, drinking alcohol daily, or binge drinking (Johnston et al., 2017). Peer Use (Number of Friends who Drink). Youth reported if their peers drink alcohol (full standard drinks) on a 5-point Likert scale (“none”=0, “a few”=1, “some”=2, “most”=3, or “all”=4) (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2015).

Substance Use Perceived Risk.

Participants were asked to report their perceptions of harm for low to high level alcohol use (1–2 drinks, drinking every day, binging; Johnston et al., 2017). No risk was scored as “0”, while perceiving great risk of harm was scored as “3”.

AUD Family History.

Family history of alcohol use disorder (AUD) was reported through the family history of psychopathology interview (Rice et al., 1995). Only diagnostic history of one or both biological parents with AUD was used in the present study (Parent History of AUD).

Parental Substance Use.

Information on the reporting parent’s substance use was derived from the Achenbach Adult Self Report (Achenbach, 2009). Of interest here, parents who attended the in-person assessments with the child reported their own frequency of drinking too much alcohol (Parent-Reported Drunkenness Frequency), days of getting drunk (Parent-Reported Days Drunk), cigarette use (Parent-Reported Cigarettes per Day), and number of days of illicit substance use (Parent-Reported Drug Use Days).

Alcohol Access.

Parents reported how easy it would be for their children to drink alcohol if their child wanted to (Hyland et al., 2017). Responses varied from very hard (scored as 0) to very easy (scored as 3), with higher scores indicating greater ease (Ease of Alcohol Access).

Family and Environmental Influences.

Family Environment Scale (Conflict Subscale).

Youth reported family conflict on a 9-item binary scale (Moos & Moos, 1994), with higher scores indicating more conflict (Family Conflict).

PhenX.

Neighborhood Safety. Neighborhood Safety was reported by youth. They answered one question regarding how safe they felt walking around their neighborhood (within one mile of their home) on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater feelings of safety. Adverse Life Events Scale. Youth reported lifetime occurrence of a range of adverse life events they may have experienced and how much it affected them. Both measures came from the PhenX Toolkit (Hamilton et al., 2011).

R-Movie Viewing.

Youth were asked the frequency with which they view R-rated movies (“Never”=0, “Once in A While”=1, “Regularly”=2, “All the Time”=3), with higher scores indicating greater frequency (Hull, Brunelle, Prescott, & Sargent, 2014). Viewing of R-rated movies was included (1) as a proxy variable for alcohol advertising familiarity, as the ABCD study does not query this and (2) because viewing of R-rated movies has been associated with increased odds of alcohol use (Tanski, Dal Cin, Stoolmiller, & Sargent, 2010).

Neurocognition.

Delay Discounting.

The Adjusting Delay Discounting Task (Koffarnus & Bickel, 2014) is a 42-item task in which participants choose between getting a smaller amount of money right now or a larger amount (up to $100) sometime in the future (between 6 hours and 5 years). Area under the curve (AUC) was calculated according to standardized procedures (Myerson, Green, & Warusawitharana, 2001).

Data Analysis.

All statistical analyses were conducted in R 3.6.1 through RStudio. Correlations were run between all independent variables and the dependent variable to ensure the dependent variable was unique from the predictors. The R package GFA (Leppäaho, Ammad-ud-din, & Kaski, 2017) was used to run a Group Factor Analysis (GFA) to create latent factors encompassing the shared variance across 27 risk-factors for early and/or problematic alcohol use. Extracted latent factors were subsequently used in logistic regression models using the R package gamm4 (Wood, 2017). GFA was chosen to better account for relationships across questionnaires. ABCD release 2.0.1 included data from 4,951, of which a significant portion (25%) had already at least sipped alcohol by ages 10–11 and thus were excluded. Further, participants with any missing data (including missing data due to answering “Refused to Answer” or “I don’t know”) from included variables were excluded (see Missing Data below); 2,334 had complete datasets and were included in the present analyses. Logistic regressions predicted youth-reported curiosity about alcohol use (yes/no) from each individual latent risk factor (from the GFA) controlling for fixed effects of relevant demographic covariates (race, age, sex, household income) and a random effect of site. The use of latent factors was used given the fact that there are numerous identified risk factors and it is likely that certain profiles, rather than individual risk variables, that best predict overall substance use risk (here designated as curiosity). To confirm this, we also assessed the relative utility of identified latent factors to individual risk variables.

Missing Data.

While 4,951 participants completed Year 1 sessions, 1,227 participants had sipped alcohol and thus were not asked about curiosity but excluded from analyses. A further 347 participants answered either “Don’t know” or “Refuse to answer” when queried about alcohol curiosity, or denied having heard of alcohol and were not queried. Of the remaining participants, 278 did not report complete demographic data and 765 completed at least one of the remaining questionnaires with one or more responses of either “I don’t know” or “Refuse to answer”. Together this resulted in a sample of 2,334 with complete data for analyses.

Group Factor Analysis.

A total of 27 variables were entered into a GFA. The GFA approach identifies latent factors between variables, while also taking into consideration within-group factors that may contribute to the relative loading on a latent factor. This method minimizes within-group correlations to find correlations between measures in different groups. This is particularly pertinent when using multiple measures from the same instrument, such as subscales from a single questionnaire, which will often be highly correlated with each other. Therefore, GFA allows a more nuanced assessment of the variance across measures from the same and different sources. Thus, GFA is similar to a Bayesian exploratory factor analysis (EFA), but improves upon an EFA in that it allows for taking into account group factors between variables. GFA latent factors included here account for at least 4% of loading across all variable groupings and demonstrated orthogonal relationships between factors.

Mixed-effects logistic regressions.

Mixed-effect logistic regression models were implemented using the “gamm4” R-package to test associations between endorsement of curiosity about alcohol use and each latent factor (in independent models), controlling for fixed effects of sex, age, race, household income and random effect of data collection site. Variables that loaded significantly onto a latent factor were then run in one overall logistic regression (without the GFA latent factors included) to assess if any variable explained unique variance in alcohol curiosity above the shared variance from the GFA predictors. If any individual variables were associated with curiosity, they were then run in a separate model with covariates to assess their uniquely predicted variance. Six logistic regression models were run in total. Coefficients with a p < .01 were interpreted as significant. Odds ratios were calculated by taking the exponent of the coefficient.

Results

Demographics.

Table 1 contains sample demographics.

Table 1.

Demographics for ABCD participants at their 1-year follow-up included in NDA 2.0.1 with complete data for the measures analyzed.

| Variable | N=2334 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| White | 1720 | 74% |

| Black | 217 | 9% |

| Asian | 50 | 2% |

| Other/Mixed | 347 | 15% |

| % Male | 1186 | 51% |

| Household Income | ||

| <$50k/year | 540 | 23% |

| ≥$50k and <$100k/year | 768 | 33% |

| ≥$100k | 1026 | 44% |

| Parental Education | ||

| < High School Diploma | 60 | 3% |

| High School Diploma/GED | 134 | 6% |

| Some College | 599 | 26% |

| Bachelor | 678 | 29% |

| Post Graduate Degree | 863 | 37% |

| Mean | SD | |

| Age (years) | 10.99 | 0.64 |

Correlations between individual variables.

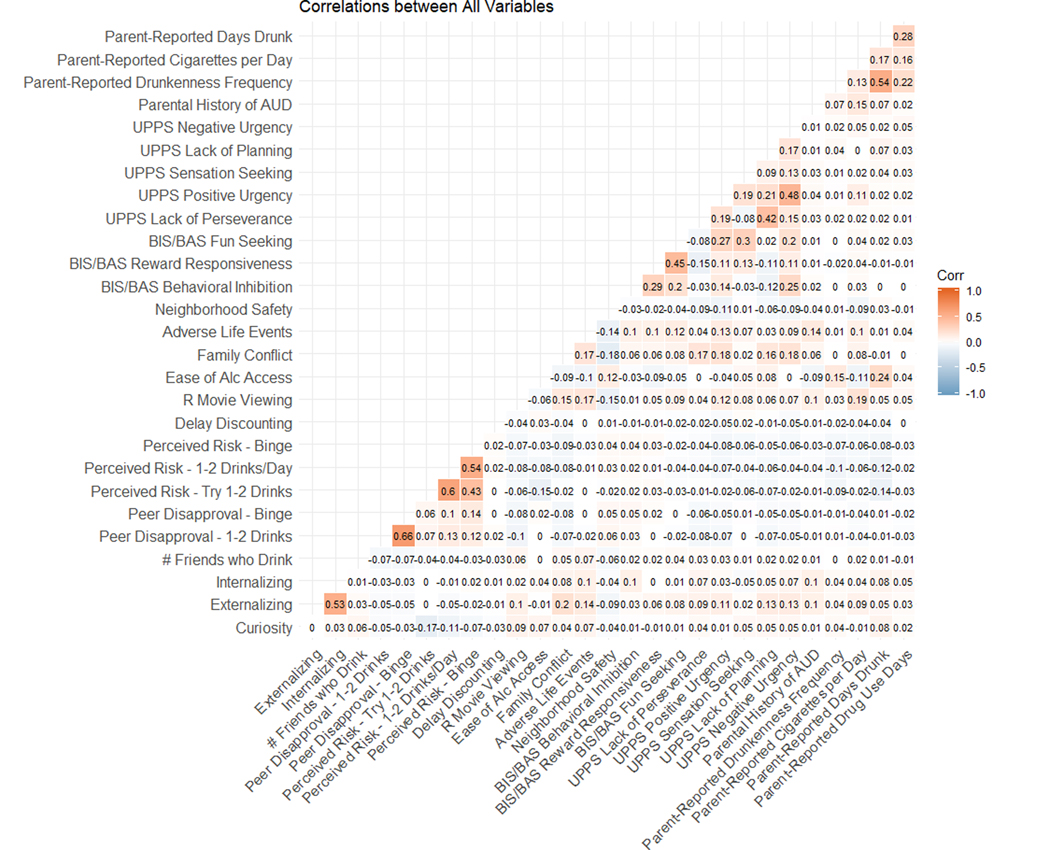

Zero-order correlations were created to assess the relative relationships between each individual risk variable and curiosity. As observed in Figure 1, no individual risk variable was strongly or significantly correlated with curiosity about alcohol use.

Figure 1.

Zero-order correlations between each individual risk variable and participant-reported alcohol curiosity.

Latent factors of risk for early alcohol use using a GFA.

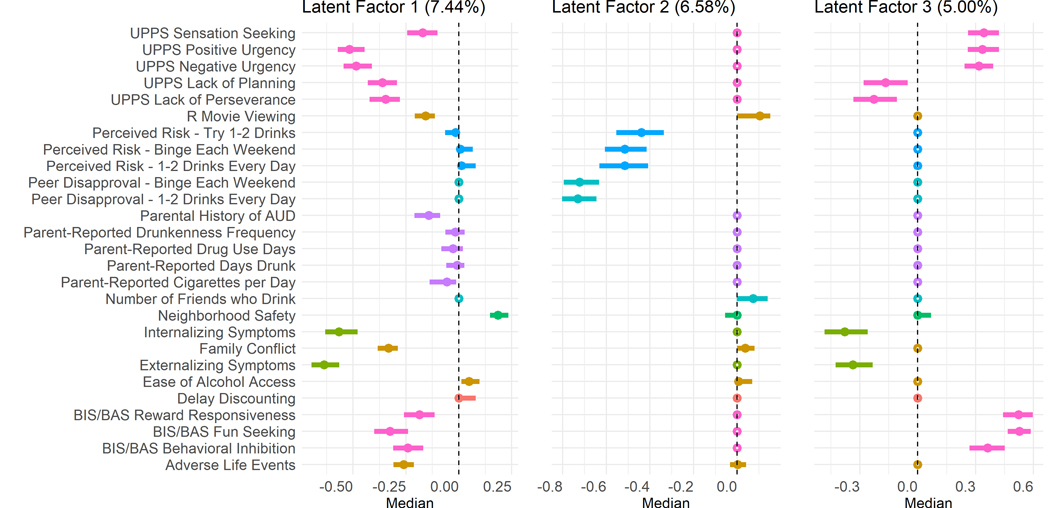

Three latent factors were identified (see Figure 2). Factor 1 contains variables that are thought to confer general risk, such as trait behavior, psychopathology, parental substance use and environment. It explained 7.44% of the variance across all of the measures input into the GFA. Variables that significantly loaded onto this latent factor included: self-report of feeling safe in his/her neighborhood with less impulsivity (UPPS and BIS/BAS), negative parental history of AUD, greater access to alcohol, parents who use fewer cigarettes per day, fewer negative life experiences and familial conflicts, less viewing of R-rated movies, and less internalizing and externalizing psychopathology.

Figure 2.

Median values for risk variable loadings by each of the three GFA latent factors. 95% confidence intervals are shown. Empty circles indicate that the variable in question did not load on to the latent factor. Variables with confidence intervals that cross 0.00 suggest that the variable is not meaningfully influencing the latent factor. Higher values are indicative of greater loading onto the factor, while values below 0 indicate negative loading of variables onto the factor.

Factor 2 explained 6.58% of the variance across measures and variables that significantly loaded onto this factor included peer disapproval of alcohol use and perceived risk of alcohol use (i.e., less perceived risk and peers who would not disapprove of substance use). While an additional five variables (delay discounting, neighborhood, conflict, alcohol access, and viewing of R movies) related to this factor (as observed in Figure 2), they did not influence overall factor loading.

Factor 3 represented a split between aspects of traits and low psychopathology and explained 5.00% of the variance. Variables contributing to the factor included higher BIS/BAS (reward and fun seeking, inhibition), higher UPPS (negative and positive urgency, and sensation seeking), lower internalizing and externalizing symptoms, with lower scores on UPPS lack of planning and UPPS lack of perseverance.

Predicting curiosity for alcohol use using latent factors of risk.

Factor 1 (consisting of broad and multiple risk factors for substance use) was significantly and inversely associated with curiosity about alcohol use (p < .001; OR = 0.75; adjusted R2 = .0161), such that individuals who loaded onto this profile of low general risk for substance use were less likely to endorse being curious. Factor 2 (consisting of peer disapproval and perceived risk) was positively associated with increased risk of curiosity about alcohol use (p < .001; OR = 1.32; adjusted R2 = .0186), indicating that, independent of the other more general risk factors for substance use, participants whose profiles loaded more robustly onto this factor through having lower levels of perceived risk of alcohol use and having peers that do not disapprove of use were more likely to endorse being curious. In this regression, being male was also associated with increased odds of alcohol curiosity (p = .005; OR = 1.43). Finally, Factor 3 (consisting of split trait and low psychopathology) was not significantly associated with curiosity about use (p = .62, adjusted R2 = .0099), though being male was associated with increased odds (p = .003; OR = 1.46). In each regression, household income significantly related to curiosity (p < .01; OR = 1.61–1.84), where a household income of >$100,000 significantly increased odds of curiosity relative to a household income <$50,000.

A final regression was run with all variables that loaded onto any significant GFA to assess the individual effect sizes for each variable in predicting curiosity and to determine unique variance predicted by individual variables. This model explained 5.36% variance in youth curiosity (adjusted R2 = .0536). Less perceived neighborhood safety (p = .0099; OR=0.83) and lower perceived risk of trying 1–2 alcohol drinks (p < .0001; OR = 0.54) was inversely associated with curiosity about alcohol use (full regression results are available in Table 2). To assess the predictive value of these isolated variables relative to the full model, we ran two final regressions with either variable (i.e., only perceived neighborhood safety in one model, and only perceived risk of low level alcohol use in the other) and covariates. Neighborhood safety predicted 1.3% of the variance and low perceived risk accounted for 3.7%.

Table 2.

Descriptive data for all variables included in the group factor analysis.

| Variable | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Externalizing Symptoms | 44.31 | 9.53 |

| Internalizing Symptoms | 48.47 | 10.40 |

| # Friends who Drink | 0.01 | 0.12 |

| Peer Disapproval – 1–2 Drinks Every Day | 2.88 | 0.35 |

| Peer Disapproval – Binge Each Weekend | 2.91 | 0.30 |

| Perceived Risk – Try 1–2 Drinks | 2.74 | 0.94 |

| Perceived Risk – 1–2 Drinks Every Day | 3.32 | 0.83 |

| Perceived Risk – Binge Each Weekend | 3.57 | 0.73 |

| Delay Discounting | 0.48 | 0.30 |

| R Movie Viewing | 1.31 | 0.56 |

| Ease of Alcohol Access | 2.04 | 1.23 |

| Family Conflict | 1.72 | 1.80 |

| Adverse Life Events | 2.28 | 2.20 |

| Neighborhood Safety | 4.28 | 0.90 |

| BIS/BAS Behavioral Inhibition | 9.43 | 3.76 |

| BIS/BAS Reward Responsiveness | 11.06 | 2.80 |

| BIS/BAS Fun Seeking | 5.63 | 2.58 |

| UPPS Lack of Perseverance | 6.80 | 2.15 |

| UPPS Positive Urgency | 7.64 | 2.88 |

| UPPS Sensation Seeking | 9.73 | 2.61 |

| UPPS Lack of Planning | 7.53 | 2.29 |

| UPPS Negative Urgency | 8.20 | 2.58 |

| Parental History of AUD | 0.08 | 0.21 |

| Parent-Reported Drunkenness Frequency | 1.10 | 0.31 |

| Parent-Reported Cigarettes Per Day | 0.88 | 4.44 |

| Parent-Reported Days Drunks | 1.27 | 5.24 |

| Parent-Reported Drug Use Days | 1.39 | 11.62 |

Notes: SD=standard deviation; for Externalizing and Internalizing symptoms, normed T-scores were used; # friends who drink: none=0 to all=4; Close friends perception of trying alcohol once or twice, or 5+ times/weekend: strongly disapprove=2 to not disapprove=0; Perceived risk of 1–2 drinks, drinking every day, binging: No risk=0 to great risk=3; standardized Delay Discounting area under the curve (AUC); R Movie Viewing: never=0 to all the time=3; Ease of Alcohol Access: very hard=0 to very easy=3; Family Conflict: higher scores indicate more conflict; # Adverse Life Events: higher scores indicate more adverse life events; Neighborhood Safety: Higher scores indicate greater perceived safety on a 1–5 scale; BIS/BAS and UPPS subscales: higher scores indicate higher levels of loading onto subscale; Parental History of AUD: neither biological parent with history of AUD=0, either/both biological parent(s) with history of AUD=1; Parent-Reported Drunkenness Frequency: parental self-report of “I drink too much or get drunk”, 0=not true to 2=very true/often; Parent-Reported Cigarettes Per Day: parental self-report of number of times they use tobacco per day (raw number); Parent-Reported Days Drunks: parental self-report of number of times they were drunk in the past 6 months (raw number); Parent-Reported Drug Use Days: parental self-report of number of times they used illicit substance recreationally in the past 6 months (raw number).

Discussion

Curiosity is noted to be an antecedent to common early risk factors for later substance use (Pierce et al., 2005), potentially making it one of the earliest markers for risk of substance initiation. The present study examined the shared variance across numerous alcohol initiation risk factors and showed that several latent factors readily predicted curiosity about alcohol use in a large developmental sample, providing targets for early prevention. Specifically, we found that 9–11 year-olds with greater curiosity about alcohol were more likely to have lower perception of risk of alcohol use combined with peers that have do not disapprove of alcohol use. They also have a profile consistent with many commonly found substance use risk factors, including parental substance use, trait impulsivity, psychopathology, and negative environmental influences such as perceived neighborhood safety and family conflict (Clark & Winters, 2002; Donovan & Molina, 2011; Gorka et al., 2014; Heron et al., 2013; Sargent et al., 2010). Finally, results indicated that lack of perceived risk of low levels of alcohol use was the independent risk factor most strongly associated with curiosity about alcohol use, though notably it is the synchrony of the measures that travel together that have a better predictive value than isolated variables. This demonstrates that risk-factors that predict later alcohol use can predict curiosity about alcohol use, before any alcohol experimentation has occurred, and highlights that curiosity may be an important construct in identifying at-risk youth and shaping prevention efforts. Further, monitoring and assessing for curiosity may be a quick proxy for identifying individuals with a profile that would place them at increased risk of alcohol use.

Consistent with prior results that perceived harm of alcohol use is an important factor in risk for alcohol onset (Henry, Slater, & Oetting, 2005; Maggs et al., 2015), we found youth who reported less perceived risk of trying one-to-two alcoholic drinks were more likely to report curiosity about alcohol use, and this also loaded with peer approval of alcohol use on Factor 2. A study of more than 10,000 10–11 year-olds in the UK found youth who had already had a full drink of alcohol were more likely to report trying one or two drinks as conferring minimal to no risk (Maggs et al., 2015). However, this study notably focused on youth who had already initiated alcohol use, rather than identifying those at risk for use; it may be that lack of perceived risk may have predated the initiation of alcohol use. Another study followed pre-adolescents for two years and found that those reporting low perceived alcohol-related risk and having alcohol using peers were more likely to initiate alcohol use (Henry et al., 2005). Perceived risk appears a particularly important construct in identifying those at risk for earliest alcohol onset as measured by curiosity.

Other risk-factors for alcohol use were also associated with alcohol curiosity when combined into latent factors. For example, three notable substance-related and familial factors loaded with or on Factor 1: parental legal substance use and family conflict loaded onto Factor 1, while family SES was significantly related to curiosity in the logistic regression assessing Factor 1. Prior results have supported parental substance use (Donovan & Molina, 2011) and family conflict (Hayatbakhsh et al., 2008) as risk factors of child and adolescent substance use. Residing in a socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhood has also been shown to increase risk (Cambron, Kosterman, Catalano, Guttmannova, & Hawkins, 2018), as suggested from Factor 1, which consisted of factors associated with general risk. Consistent with our finding that children from higher income families were more likely to report being curious, belonging to a higher SES family was associated with more substance use in a study of adolescents (Humensky, 2010). The extent to which higher or lower SES contributes to increased or decreased risk of curiosity and use behaviors remains unclear. As ABCD is a longitudinal study with annual in-person assessments, we will be able to follow this cohort over time and examine the influence of pre-adolescent curiosity and SES on later substance initiation.

Trait characteristics (Sargent et al., 2010) and psychopathology (Gorka et al., 2014; Heron et al., 2013) similarly loaded onto Factor 1, which was significantly and inversely related to curiosity. Low scores on all impulsivity and behavioral approach scales and less reported psychopathology, when combined into a latent factor, were associated with decreased odds of curiosity. In contrast, participants who reported some aspects of impulsivity (e.g., sensation seeking, urgency, fun seeking and reward responsivity) but not others (ability to plan and persevere) loaded on Factor 3, which was not associated with curiosity. Therefore, high impulsivity accompanied by behavioral issues (exemplified in psychopathology and lack of task planning or completion) may be uniquely related to curiosity. This is further reinforced by follow-up analyses which suggest it is these variables in concert with one another as identified in the latent factors that are associated with curiosity, rather than individual risk factors independently relating to curiosity.

However, not all expected and included variables loaded onto latent factors in a way that translated to increased curiosity. Delay discounting—a common measure of decision making in addiction populations (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2009; MacKillop et al., 2011)—was not significantly related to curiosity in the present results (though delay discounting approached significance [p=.06] when included independently in the final overall regression). Parental illicit substance use was also not identified as a part of a latent factor. It may be that these profiles and variables are not closely related to curiosity, but are more relevant in determining actual substance use onset; this will need to be explored over time.

Taken together, our results indicate that curiosity about alcohol use is influenced by many multidimensional factors that overlap with risk for alcohol initiation among youth. Importantly, one directly addressable risk-factor has been identified: perceived harm of alcohol use (and particularly harm from one-to-two drinks). Adolescent perceptions of risks associated with alcohol use can be influenced over time. A more accurate understanding of risks can correspond with changes in use patterns (Cable, Roman Mella, & Kelly, 2017; Grevenstein, Nagy, & Kroeninger-Jungaberle, 2015) and thus providing early and accurate information to youth is of great importance. Our results, consistent with the extant literature, suggest that early childhood prevention interventions should include psychoeducation on the relative risk of use during childhood and early adolescence in order to mitigate curiosity around alcohol use. Further, broad-based psychoeducation may lead to changes in both personal risk perception and peer disapproval rates, which combined account for greater shared variance of curiosity explained. This needs to be investigated in future research, as there are no known clinical interventions for substance related curiosity in youth.

Clinically, it is important to address both risk factors (such as perceived risk) and, if reported, alcohol curiosity. Addressing modifiable risk factors may prevent the development of curiosity, while curiosity itself may also be modifiable, though this has not yet been studied. As prior research suggests curiosity is a search for information as a source of reward (Giambra et al., 1992; Grossnickle, 2014), providing more factual information regarding alcohol use may satiate a pre-adolescent’s curiosity, hopefully contributing to a delayed onset of use. Information acting as a reward may be contribute to this end (Jepma et al., 2012). Further, other research suggests parents communicating with their children about substance use risk decreases odds of substance use onset (Kuntsche & Kuntsche, 2016). Opening lines of communication also increases parent-child engagement (Salas-Wright et al., 2019), allowing for children to be curious and ask questions, which may contribute to youth receiving more accurate and beneficial information. Interventions can be shaped with this aim, much as suggested above in addressing perceived harm, and implemented by either professionals or caregivers; efficacy of modifying curiosity should then be assessed.

It is important to note that 25% of the total ABCD cohort in data release 2.0.1 (N=4,951) had already at least sipped alcohol by ages 10–11 and thus were excluded. Additionally, only a subset of the entire cohort (N=11,880) is available for data analysis time of analysis. Our preliminary results using the currently available population of 10–11 year-old participants from the ABCD study indicate a unique population of pre-adolescent youth who may be at elevated risk for substance initiation, though they are not among those who are easily identified through self-reported substance experimentation. Many important risk factors were assessed here, consistent with prior literature and enabled through use of GFA for data reduction. Other variables (e.g., sibling alcohol use) were not measured at this time point, though are being included in future years of ABCD data collection. Desirability effects, denying and/or over-reporting alcohol use or curiosity (Del Boca & Darkes, 2003; Lantini et al., 2015; Stein et al., 2002) are always a possibility when examining self-reported substance use; however gold standard approaches to substance use assessment with this age group are employed as part of the protocol and likely minimize this inaccurate reporting and bias. Even so, our findings suggests participants’ reporting may still be useful in identifying those most at risk of alcohol onset.

In conclusion, these findings provide preliminary evidence of factors that may influence curiosity about alcohol use. We found that lack of perceived harm from alcohol experimentation was related to the greatest odds of curiosity about alcohol use. Further, a GFA analysis revealed that when youth did not perceive alcohol use as risky and also believed that their friends would not disapprove of alcohol use, they were more likely to endorse being curious. This suggests that while individual variables are important, the pattern of an individual’s profile is useful for identifying those at risk. Providing thorough, accurate and age-targeted information on alcohol-related harms may delay onset of adolescent alcohol use. Future longitudinal work through the ABCD study needs to assess whether these latent factors predict transition to alcohol use behaviors as well as curiosity.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression with All Independent Variables Included.

| Variable | Coefficient Estimate | Standard Error | Z value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −3.345 | 1.444 | −2.317 | 0.02 |

| Past Month Parents’ Tobacco Use | −0.01 | 0.017 | −0.600 | 0.548 |

| Parental History AUD | 0.196 | 0.316 | 0.620 | 0.535 |

| Delay Discounting | −0.434 | 0.228 | −1.906 | 0.057 |

| UPPS – Negative Urgency | 0.023 | 0.031 | 0.735 | 0.462 |

| UPPS – Planning | −0.01 | 0.033 | −0.290 | 0.772 |

| UPPS – Sensation Seeking | 0.035 | 0.027 | 1.259 | 0.208 |

| UPPS – Positive Urgency | −0.001 | 0.028 | −0.053 | 0.958 |

| UPPS – Perseveration | 0.047 | 0.035 | 1.346 | 0.178 |

| BIS/BAS – Fun Seeking | −0.012 | 0.031 | −0.400 | 0.689 |

| BIS/BAS – Behavioral Inhibition | 0.011 | 0.02 | 0.529 | 0.597 |

| BIS/BAS – Reward Response | −0.021 | 0.028 | −0.734 | 0.463 |

| Neighborhood Safety | −0.191 | 0.074 | −2.579 | 0.0099 |

| Adverse Life Events | 0.078 | 0.03 | 2.572 | 0.01 |

| Family Conflict | 0.029 | 0.038 | 0.769 | 0.442 |

| Frequency of Viewing R-Movies | 0.240 | 0.117 | 2.056 | 0.04 |

| Perceived Risk of Binge Drinking | 0.192 | 0.108 | 1.778 | 0.075 |

| Perceived Risk of Regular Drinking | −0.022 | 0.106 | −0.211 | 0.833 |

| Perceived Risk of Trying 1–2 Drinks | −0.608 | 0.092 | −6.596 | 4.23e-11 |

| Peer Disapproval of Alcohol Use | 0.669 | 0.41 | 1.629 | 0.103 |

| Internalizing Symptoms | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.252 | 0.801 |

| Externalizing Symptoms | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.401 | 0.688 |

| Perceived Ease of Alcohol Access | 0.063 | 0.056 | 1.116 | 0.265 |

| Friends Binge Drink | 0.111 | 0.291 | 0.383 | 0.702 |

| Friends Drink Alcohol | −0.399 | 0.25 | −1.595 | 0.111 |

| Race (Black) | −0.667 | 0.302 | −2.207 | 0.027 |

| Race (Asian) | −0.067 | 0.495 | −0.134 | 0.893 |

| Race (Other/Mixed) | −0.169 | 0.193 | −0.878 | 0.38 |

| Age | 0.017 | 0.009 | 1.910 | 0.056 |

| Sex | 0.295 | 0.136 | 2.167 | 0.03 |

| Household Income (≥$50k and <$100k/year) | 0.257 | 0.202 | 1.275 | 0.202 |

| Household Income (≥$100k/year) | 0.597 | 0.207 | 2.888 | 0.004 |

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by T32 AA013525 (PI: Riley/Tapert to Wade), U01DA041089 (PI: Tapert/Jacobus), NIH/NIDA R21 DA047953 (PI: Jacobus), and California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Grants Program Office of the University of California Grant 580264 (PI: Jacobus).

The ABCD Study is supported by the National Institutes of Health and additional federal partners under award numbers U01DA041022, U01DA041028, U01DA041048, U01DA041089, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041120, U01DA041134, U01DA041148, U01DA041156, U01DA041174, U24DA041123, and U24DA041147.

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study (https://abcdstudy.org), held in the NIMH Data Archive (NDA). This is a multisite, longitudinal study designed to recruit more than 10,000 children age 9–10 and follow them over 10 years into early adulthood. A full list of supporters is available at https://abcdstudy.org/federal-partners.html. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/study-sites/. ABCD consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and/or provided data but did not necessarily participate in analysis or writing of this report. This manuscript reflects the views of the authors and may not reflect the opinions or views of the NIH or ABCD consortium investigators. The ABCD data repository grows and changes over time. The ABCD data used in this report came from Annual Release 2.0.1, doi: 10.15154/1503209. DOIs can be found at https://ndar.nih.gov/study.html?id=576

Reference List

- Achenbach TM (2009). The Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessemnt (ASEBA): Development, Findings, Theory, and Applications. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Epstein LH, Cuevas J, Rodgers K, & Wileyto EP (2009). Does delay discounting play an etiological role in smoking or is it a consequence of smoking? Drug Alcohol Depend, 103(3), 99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Albaugh MD, Avenevoli S, Chang L, Clark DB, Glantz MD, . . . Sher KJ (2018). Demographic, physical and mental health assessments in the adolescent brain and cognitive development study: Rationale and description. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 32, 55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cable N, Roman Mella MF, & Kelly Y. (2017). What could keep young people away from alcohol and cigarettes? Findings from the UK Household Longitudinal Study. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 371. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4284-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambron C, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Guttmannova K, & Hawkins JD (2018). Neighborhood, Family, and Peer Factors Associated with Early Adolescent Smoking and Alcohol Use. J Youth Adolesc, 47(2), 369–382. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0728-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, & White TL (1994). Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Cannonier T, Conley MI, Cohen AO, Barch DM, Heitzeg MM, . . . Workgroup AIA (2018). The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study: Imaging acquisition across 21 sites. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 32, 43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Somerville LH, Gotlib IH, Ayduk O, Franklin NT, Askren MK, . . . Shoda Y. (2011). Behavioral and neural correlates of delay of gratification 40 years later. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 108(36), 14998–15003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108561108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, & Pierce JP (2001). Determining the probability of future smoking among adolescents. Addiction, 96(2), 313–323. doi: 10.1080/09652140020021053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, & Winters KC (2002). Measuring risks and outcomes in substance use disorders prevention research. J Consult Clin Psychol, 70(6), 1207–1223. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.6.1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, & Darkes J. (2003). The validity of self-reports of alcohol consumption: state of the science and challenges for research. Addiction, 98, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, & Molina BSG (2011). Childhood Risk Factors for Early-Onset Drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72(5), 741–751. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavan H, Bartsch H, Conway K, Decastro A, Goldstein RZ, Heeringa S, . . . Zahs D. (2018). Recruiting the ABCD sample: Design considerations and procedures. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 32, 16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentzke AS, Wang B, Robinson JN, Phillips E, & King BA (2019). Curiosity About and Susceptibility Toward Hookah Smoking Among Middle and High School Students. Prev Chronic Dis, 16, E04. doi: 10.5888/pcd16.180288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giambra LM, Camp CJ, & Grodsky A. (1992). Curiosity and stimulation seeking across the adult life span: Cross-sectional and 6- to 8-year longitudinal findings. Psychology and Aging, 7(1), 150–157. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.7.1.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM, Shankman SA, Olino TM, Seeley JR, Kosty DB, & Lewinsohn PM (2014). Anxiety disorders and risk for alcohol use disorders: the moderating effect of parental support. Drug Alcohol Depend, 140, 191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grevenstein D, Nagy E, & Kroeninger-Jungaberle H. (2015). Development of risk perception and substance use of tobacco, alcohol and cannabis among adolescents and emerging adults: evidence of directional influences. Subst Use Misuse, 50(3), 376–386. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.984847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossnickle EM (2014). Disentangling Curiosity: Dimensionality, Definitions, and Distinctions from Interest in Educational Contexts. Educational Psychology Review, 28(1), 23–60. doi: 10.1007/s10648-014-9294-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber MJ, Gelman BD, & Ranganath C. (2014). States of curiosity modulate hippocampus-dependent learning via the dopaminergic circuit. Neuron, 84(2), 486–496. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.08.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Unger JB, Azen SP, MacKinnon DP, & Johnson CA (2012). Do cognitive attributions for smoking predict subsequent smoking development? Addict Behav, 37(3), 273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Unger JB, Palmer PH, Chou CP, & Johnson CA (2013). The role of cognitive attributions for smoking in subsequent smoking progression and regression among adolescents in China. Addict Behav, 38(1), 1493–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton CM, Strader LC, Pratt JG, Maiese D, Hendershot T, Kwok RK, . . . Haines J. (2011). The PhenX Toolkit: get the most from your measures. Am J Epidemiol, 174(3), 253–260. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayatbakhsh MR, Mamun AA, Najman JM, O’Callaghan MJ, Bor W, & Alati R. (2008). Early Childhood Predictors of Early Substance use and Substance use Disorders: Prospective Study. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 42(8), 720–731. doi: 10.1080/00048670802206346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry KL, Slater MD, & Oetting ER (2005). Alcohol Use in Early Adolescence: The Effect of Changes in Risk Taking, Perceived Harm and Friends’ Alcohol Use. J. Stud. Alcohol, 66, 275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron J, Maughan B, Dick DM, Kendler KS, Lewis G, Macleod J, . . . Hickman M. (2013). Conduct problem trajectories and alcohol use and misuse in mid to late adolescence. Drug Alcohol Depend, 133(1), 100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull JG, Brunelle TJ, Prescott AT, & Sargent JD (2014). A longitudinal study of risk-glorifying video games and behavioral deviance. J Pers Soc Psychol, 107(2), 300–325. doi: 10.1037/a0036058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humensky JL (2010). Are adolescents with high socioeconomic status more likely to engage in alcohol and illicit drug use in early adulthood? Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy, 5, 19. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-5-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, Borek N, Lambert E, Carusi C, . . . Compton WM (2017). Design and methods of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Tob Control, 26(4), 371–378. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-052934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isles AR, Winstanley CA, & Humby T. (2019). Risk taking and impulsive behaviour: fundamental discoveries, theoretical perspectives and clinical implications. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 374(1766), 20180128. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2018.0128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, & Rogers ML (2015). The prospective association between sipping alcohol by the sixth grade and later substance use. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs, 76, 212–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepma M, Verdonschot RG, van Steenbergen H, Rombouts SA, & Nieuwenhuis S. (2012). Neural mechanisms underlying the induction and relief of perceptual curiosity. Front Behav Neurosci, 6, 5. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2012.00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Patrick ME (2020). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2019: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Patrick ME (2019). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use 1975–2018: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor:: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2015). Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2014: Volume I, Secondary School Students. The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Kang MJ, Hsu M, Krajbich IM, Loewenstein G, McClure SM, Wang JT, & Camerer CF (2009). The wick in the candle of learning: Epistemic curiosity activates reward circuitry and enhances memory. Psychological Science, 20(8), 963–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, & Bickel WK (2014). A 5-trial adjusting delay discounting task: accurate discount rates in less than one minute. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol, 22(3), 222–228. doi: 10.1037/a0035973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche S, & Kuntsche E. (2016). Parent-based interventions for preventing or reducing adolescent substance use - A systematic literature review. Clin Psychol Rev, 45, 89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantini R, McGrath AC, Stein LA, Barnett NP, Monti PM, & Colby SM (2015). Misreporting in a randomized clinical trial for smoking cessation in adolescents. Addict Behav, 45, 57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppäaho E, Ammad-ud-din M, & Kaski S. (2017). GFA: Exploratory Analysis of Multiple Data Sources with Group Factor Analysis. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lisdahl KM, Sher KJ, Conway KP, Gonzalez R, Feldstein Ewing SW, Nixon SJ, . . . Heitzeg M. (2018). Adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) study: Overview of substance use assessment methods. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 32, 80–96. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciana M, Bjork JM, Nagel BJ, Barch DM, Gonzalez R, Nixon SJ, & Banich MT (2018). Adolescent neurocognitive development and impacts of substance use: Overview of the adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) baseline neurocognition battery. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 32, 67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynman DR (2013). Development of the Short Form of the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale. Unpublished Technical Report [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Amlung MT, Few LR, Ray LA, Sweet LH, & Munafo MR (2011). Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 216(3), 305–321. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2229-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Staff J, Patrick ME, Wray-Lake L, & Schulenberg JE (2015). Alcohol use at the cusp of adolescence: a prospective national birth cohort study of prevalence and risk factors. J Adolesc Health, 56(6), 639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin CB, & Shohamy D. (2016). Curiosity and reward: Valence predicts choice and information prediction errors enhance learning. J Exp Psychol Gen, 145(3), 266–272. doi: 10.1037/xge0000140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos BS, & Moos RH (1994). Family Environment Scale Manual and Sampler Set: Development, Applications and Research. Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Myerson J, Green L, & Warusawitharana M. (2001). Area under the curve as a measure of delay discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 76, 235–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nodora J, Hartman SJ, Strong DR, Messer K, Vera LE, White MM, . . . Pierce JP (2014). Curiosity predicts smoking experimentation independent of susceptibility in a US national sample. Addict Behav, 39(12), 1695–1700. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, & Merritt RK (1996). Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol, 15, 355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Distefan JM, Kaplan RM, & Gilpin EA (2005). The role of curiosity in smoking initiation. Addict Behav, 30(4), 685–696. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice JP, Reich T, Bucholz AK, Neuman RJ, Fishman R, Rochberg N, . . . Begleiter H. (1995). Comparison of direct interview and family history diagnoses of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 19, 1018–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, AbiNader MA, Vaughn MG, Sanchez M, Oh S, & Clark Goings T. (2019). National Trends in Parental Communication With Their Teenage Children About the Dangers of Substance Use, 2002–2016. J Prim Prev, 40(4), 483–490. doi: 10.1007/s10935-019-00559-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Tanski S, Stoolmiller M, & Hanewinkel R. (2010). Using sensation seeking to target adolescents for substance use interventions. Addiction, 105(3), 506–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02782.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Wills TA, Stoolmiller M, Gibson J, & Gibbons FX (2006). Alcohol use in motion pictures and its relation with early-onset teen drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67(1), 54–65. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP (2013). Adolescent neurodevelopment. J Adolesc Health, 52(2 Suppl 2), S7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein LA, Colby SM, O’Leary TA, Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Spirito A, . . . Barnett NP (2002). Response distortion in adolescents who smoke: a pilot study. J Drug Educ, 32, 271–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong DR, Hartman SJ, Nodora J, Messer K, James L, White M, . . . Pierce J. (2015). Predictive Validity of the Expanded Susceptibility to Smoke Index. Nicotine Tob Res, 17(7), 862–869. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanski SE, Dal Cin S, Stoolmiller M, & Sargent JD (2010). Parental R-Rated Movie Restriction and Early-Onset Alcohol Use. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs, 71, 452–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Koob GF, Croyle RT, Bianchi DW, Gordon JA, Koroshetz WJ, . . . Weiss SRB (2018). The conception of the ABCD study: From substance use to a broad NIH collaboration. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 32, 4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood SN (2017). Generalized additive models: An introduction with R (2nd ed.). New York: Chapman Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TC, Stairs AM, Settles RF, Combs JL, & Smith GT (2010). The measurement of dispositions to rash action in children. Assessment, 17(1), 116–125. doi: 10.1177/1073191109351372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Gonzalez R, Feldstein Ewing SW, Paulus MP, Arroyo J, Fuligni A, . . . Wills T. (2018). Assessment of culture and environment in the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development Study: Rationale, description of measures, and early data. Dev Cogn Neurosci, 32, 107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]