Abstract

Objective:

Sociocultural differences between patients and physicians affect communication, and suboptimal communication can lead to patient dissatisfaction and poor health outcomes. To mitigate disparities in surgical outcomes, the Provider Awareness and Cultural dexterity Toolkit for Surgeons (PACTS) was developed as a novel curriculum for surgical residents focusing on patient-centeredness and enhanced patient-clinician communication through a cultural dexterity framework. This study’s objective was to examine surgical faculty and surgical resident perspectives on potential facilitators and barriers to implementing the cultural dexterity curriculum.

Design, Setting, and Participants:

Focus groups were conducted at two separate academic conferences, with the curriculum provided to participants for advanced review. The first four focus groups consisted entirely of surgical faculty (n=37), each with 9 to 10 participants. The next four focus groups consisted of surgical residents (n=31), each with 6 to 11 participants. Focus groups were recorded and transcribed, and the data were thematically analyzed using a constant, comparative method.

Results:

Three major themes emerged: (1) Departmental and hospital endorsement of the curriculum are necessary to ensure successful rollout. (2) Residents must be engaged in the curriculum in order to obtain full participation and “buy-in.” (3) The application of cultural dexterity concepts in practice are influenced by systemic and institutional factors.

Conclusions:

Institutional support, resident engagement, and applicability to practice are crucial considerations for the implementation of a cultural dexterity curriculum for surgical residents. These three tenets, as identified by surgical faculty and residents, are critical for ensuring an impactful and clinically relevant education program.

Keywords: cultural dexterity, healthcare disparities, resident education, focus groups, curriculum implementation

Introduction

As the United States becomes increasingly diverse, it is imperative that healthcare providers are prepared to address the sociocultural needs of their patient populations.1 Sociocultural differences between patients and physicians affect communication and may lead to patient dissatisfaction and poor health outcomes.2,3 Multiple studies have demonstrated a need for graduate medical education to include training in cultural competency, defined as “the ability of health care providers and the health-care system to communicate effectively with, and provide quality health care to, patients from diverse sociocultural backgrounds.”4-6 The increase in diversity and parallel documentation of disparities in surgical outcomes demonstrate the importance of incorporating cross-cultural training within surgical residency education.1

Through funding from the NIH National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIH-NIMHD), the Provider Awareness and Cultural dexterity Toolkit for Surgeons (PACTS) trial attempts to mitigate disparities in surgical outcomes by improving patient-centeredness and enhancing patient-clinician communication through a cultural dexterity framework. This framework places greater emphasis on skills acquisition and adaptability to dynamic interpersonal circumstances than the traditional cultural competency framework. The PACTS curriculum, which includes four modules, follows a “flipped classroom” design. Participants are asked to complete an interactive online learning module prior to participating in an in-person experiential learning session. This format deviates from the classic lecture style in that the typical didactic content is delivered via an interactive slide deck beforehand with the opportunity for role playing, discussion, and feedback during the session itself. As an educational model, the “flipped classroom” approach has been described in the literature as an effective way to foster learning, engagement, and camaraderie for adult learners in health care professions.7,8 The trial will be conducted at eight academic medical centers across the United States.

Surgical residents who participated in early implementation of this novel cultural dexterity curriculum expressed that the curriculum was necessary and impactful.1 However, the existence of a fully developed surgical education curriculum does not ensure a successful implementation within surgery residency training programs. Shah et al. described five surgery programs that sought to provide cross-cultural training, with only the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) component of three of the five programs still in place five years after the original study.9 Many challenges exist in implementing a new curriculum, including work-hour restrictions, clinical demands, limited time for teaching from attendings given their own clinical responsiblities, curriculum oversight, and accreditation guidelines.8

Given the changes in the landscape of surgical education, including work-hour restrictions, clinical demands, attending responsibilities, curriculum oversight, and accreditation guidelines, the challenges in implementing a new curriculum are not uncommon.10 We obtained surgical faculty and surgical resident perspectives on potential facilitators and barriers to implementing a cultural dexterity curriculum. Although observations reported here were specific to the implementation of the PACTS curriculum, the findings from the focus groups may be applied to the implementation of any surgical education curriculum.

Material and Methods

Intervention Procedure

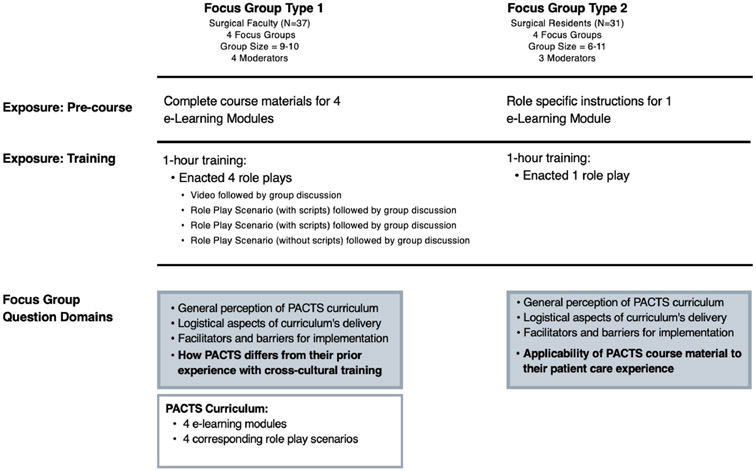

In total, eight focus groups were conducted with four groups of surgical faculty and four groups of residents to obtain their perceptions on implementation. Semi-structured interview guides were developed by the research team to elicit rich descriptions of the experiences that faculty members and residents had with the PACTS curriculum and, more generally, perceived facilitators and barriers to its implementation.

In the focus groups consisting of surgical faculty, every participant was provided with all four e-learning modules and accompanying role play scenarios to review prior to the focus group sessions. The first role play was a video demonstration played for all participants. The second and third role plays were enacted by several participants of the focus groups in front of the remaining participants; everyone was provided with the role play scenario and accompanying scripts. The fourth role play was enacted by several participants of the focus groups in front of the remaining participants; everyone was provided with a role play scenario with no script.

In the focus groups consisting of surgical residents, participants were provided with an updated version of the curriculum that had been reviewed by the surgical faculty focus groups and modified based on their input. The content of the e-learning modules were updated with more recent examples and changes were made to the role play scenarios to make them more specific to the cultural dexterity skills taught in the curriculum. Every participant was provided with one e-learning module and accompanying role play scenario to review prior to the focus group session. The e-learning module and role play scenarios that were provided for review were specific to the focus group that the participant had been assigned to.

Recruitment Strategy

The first four focus groups consisted of surgical faculty who were recruited using a convenience sampling of members of the Association of Academic Surgery attending the 2018 Executive Council Retreat. The focus groups were scheduled in advance for all faculty already participating in the Executive Council Retreat, although participation was entirely voluntary. Each group consisted of 9-10 surgical faculty by random assignment and lasted approximately one hour. The focus groups were moderated by four investigators with qualitative experience (G.O., D.S., A.G., and N.R.U.). These four focus groups were conducted simultaneously at Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois during the retreat. Participants were asked about their general perception of the PACTS curriculum, the logistical aspects of the curriculum’s delivery, how PACTS differed from their prior experiences with cross-cultural training, and what they perceived to be facilitators and barriers in implementing the curriculum.

The second four focus groups consisted of surgical residents who were recruited using a convenience sample of attendees at the 2019 Academic Surgical Congress. Selection criteria included all surgical residents that were not currently training at the eight academic medical centers participating in the PACTS trial. Recruitment for the focus groups was conducted in advance by email through the Association of Program Directors in Surgery listserv, and through word of mouth. Recruitment also took place in person during the conference. Residents who were interested in participating in the focus groups were provided with a survey link that included an information sheet with details regarding the study and sign up for a focus group time based on their availability. These focus groups were conducted over the course of two days in Houston, Texas during the conference. Each group consisted of 6 to 11 surgical residents by random assignment and lasted approximately one hour. The focus groups were moderated by three investigators (G.O., A.G., and E.R.). Participants were asked about their general perception of the PACTS curriculum, the logistical aspects of the curriculum’s delivery, the applicability of the material to their patient care and experience, and what they perceived to be facilitators and barriers in implementing the curriculum. Residents were compensated with a $25 Amazon gift card for their participation in the focus groups.

Data Collection

All participants were provided with an information sheet regarding the purpose of the study, the name and affiliation of researchers, as well as risks and benefits of participation. Participation in the focus groups was voluntary, with consent implied through participation. The focus group sessions were audio recorded and transcribed, and all files stored on a secure institutional server. The interview transcripts were uploaded and coded in NVivo Version 12.6.0, a qualitative data analysis software for data management. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Partners Healthcare (Protocol#: 2018P001237).

Qualitative Data Analyses

Focus group recordings were transcribed verbatim and deidentified. The transcriptions were coded using a constant, comparative method by an evaluation team of 3 investigators (GJL, ER, RBA). Constant comparison was conducted in developing a theory that is grounded in the data. Grounded theory was originally defined by Glaser and Strauss as a means of deriving theory to explain a phenomenon. It occurs in 3 stages: (1) open coding, when codes are assigned to summarize textual data; (2) axial coding, to begin identifying relationships between the open codes; and (3) selective coding, where the data are refined into a single phenomenon, thus forming the grounded theory.11,12 A draft codebook was developed through open coding by GJL and MSP, who independently read each transcript and met weekly to ensure a consistent interpretation of codes. Disagreements of open codes were resolved by reviewing transcripts and discussing perspective until consensus was reached between GJL and MSP. Once a comprehensive codebook was developed, a team of researchers (GJL, ER, RBA) separately coded the same transcript. Constant peer debrief meetings and checks with research team members were held in order to reach consensus. Inter-coder reliability was tested (K=0.86), which ensured high reliability amongst all three investigators. Once coding was complete, thematic analysis was conducted, where transcripts were analyzed for relevant content to identify emerging categories. Peer debriefings were held after coding was complete, wherein principal and co-investigators (DSS, GO, AJR, KL) reviewed analysis, interpretations, and framing13,14 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Similarities and Differences in Surgery Faculty and Resident Focus Groups

Results

The surgical faculty focus groups consisted of 37 participants from 30 academic institutions across various regions in the U.S., mostly from the Midwest; 33% were women. The surgical resident focus groups consisted of 31 participants from 21 academic institutions across the U.S. with most from the South region: 55% were women. The demographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Surgical Faculty and Resident Focus Group Participants

| Surgical Faculty (N=37) | Surgical Residents (N=31) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 12 | 32 | 17 | 55 |

| Male | 25 | 68 | 14 | 45 |

| Geographic representation | ||||

| Northeast | 10 | 28 | 6 | 20 |

| Midwest | 17 | 46 | 6 | 20 |

| South | 9 | 25 | 12 | 39 |

| West | 1 | 1 | 6 | 20 |

| International | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Three major themes emerged from the collective data across both sets of focus groups that summarize perceptions of potential barriers to implementing a novel surgical education curriculum. (1) Institutional support: the importance of departmental and hospital endorsement of the curriculum to ensure successful rollout. (2) Resident engagement: what is needed for full participation and buy-in from the residents. (3) Applicability to practices: the influence of systemic and institutional factors on the utilization of the concepts taught in the curriculum.

Theme 1: Institutional support

Both faculty and residents agreed that in order for rollout of the curriculum to be successful, support at the departmental and larger hospital level would be necessary. Participants indicated that the department could best demonstrate the importance of the curriculum by integrating teachings into protected, required education time. As one faculty member stated: “It probably doesn’t matter that much what the resident response to it is, if the program director believes that it’s a worthy part of the curriculum, then you could do it.”

The residents shared similar sentiments that the value of the curriculum would only be appreciated if the department provided protected time for residents to complete it. As expressed by one resident: “I do think that program participation will be important… if we’re not given the time, then no one prioritizes it.”

Faculty, in particular, recognized that departmental support should include faculty members at each institution to serve as local champions who are familiar with the curriculum and reinforce the value of the materials to the residents as well as other faculty. A total of 6 excerpts across both sets of focus groups were coded for local champions within the context of the curriculum rollout. Over 83% (5/6 excerpts) of the excerpts were coded from the faculty interviews, which reflects a need not identified by the residents. This code is exemplified by the following remark from a faculty member: “I think you … need to identify a few institutional champions, faculty members that are going to support your efforts and be very present. Even if it’s not directed towards faculty members, you can have people that are boots on the ground that are basically going to show the residents… we think this is very important, this is meaningful to the department, and we also have a vested interest in it.”

Beyond the departmental level, faculty and residents identified the necessity of support at the institutional level given the multidisciplinary nature of the surgical profession. Both groups agreed that nurses and advanced practice providers would be important in ensuring that cultural dexterity practices are upheld. As faculty member described: “The nurse practitioners, PAs…they see something, but they are afraid to bring it up because they don’t want to be in that predicament when the residents are clearly wrong.”

Including auxiliary healthcare providers and their perspectives is strongly supported by the residents. This is demonstrated by a quote from a resident: “A lot of ancillary staff, or some of our nursing colleagues…do a really great job of addressing pain and asking questions in a very specific way that’s appropriate… It’s hard to ignore the role that they play and the skill we can learn from them.”

Theme 2: Resident engagement

Residents emphasized the importance of interest in the content of the curriculum as a driver of participation and willingness to spend time learning the concepts. For example, participants indicated that awareness of personal implicit biases would be an important facilitator of buy-in. Faculty and residents agreed that exposing residents to their own biases through the Implicit Association Test (IAT)12 at the beginning of the curriculum would motivate them to go through training. There were a total of 23 excerpts across both sets of focus groups coded for awareness of personal biases necessary to ensure resident engagement. Over 39% (9/23 excerpts) of the excerpts were from faculty members, indicating an agreement amongst both groups of participants. As one faculty participant stated: “I think it will be really important that they do… some sort of pre-work so that there is some acknowledgement that they may have implicit biases, because … like most people we all assume that … we will be objective and not have those biases … I think that resident resistance, honestly in my program will probably be the biggest barrier to overcome.”

This is in agreement with a statement by a resident participant:“Doing the test first would be hard-hitting… and [the residents] would be encouraged to go through this training.”

In addition to recognizing implicit biases to achieve buy-in, residents requested evidence in the form of patient testimonials and patient outcomes to support the principles taught in the curriculum. This concept was established across a total of 19 excerpts coded for request of evidence specific to patients. Over 74% (14/19 excerpts) of the excerpts were from residents, which indicates their recognition of their own limitations in evaluating the quality of the care that they are providing to their patients. “…Incorporating like an actual patient interview with a patient that's been impacted by this could be pretty eye-opening and hit closer to home for some people.”

In contrast, the priorities of other mandatory education modules, as well as clinical responsibilities were cited by residents as competing factors for engaging in the curriculum. The faculty also shared similar concerns, with additional resident education affecting coverage in the operating room or in their clinics. As stated by a resident: “It's module after module after module. So when I go to those modules, I'm actually trying to get through them as fast as possible.” This notion is supported by a faculty member, who reflects: “If it’s not on a Saturday, and it’s not on regular academic time, then now you’re taking away from our clinics, our operative time, that residents cover.”

Residents indicated that prior experiences with role playing as part of their education curriculum are likely to affect their perception of the utility of the case exploration-based didactic sessions. A total of 8 excerpts were coded for prior perceptions of role playing, with over 87% (7/8 excerpts) from residents. One resident elaborated that pre-existing impressions of role playing would be a limiting factor in engaging fully with the curriculum. “…it seems like they're making you do role play because they needed to fill up the whole hour, so now for ten minutes you're stuck there doing a role play, and you didn't get anything out of it… Once you're set in that perception, it's harder to actually go into it and get something out of it, because you've already had this perception in your mind, "I've just gotta make it through this hour, and then we can get on with our day.””

Theme 3: Applicability to practice

While recognizing the importance of the curriculum, participants remarked on the likelihood of applying cultural dexterity practices in the clinical setting given systemic factors and the surgery culture. These factors were discussed in relation to the sustainability of the curriculum. Participants discussed the hierarchical nature of the surgical specialty, and the challenges faced by residents and faculty in addressing their coworkers or superiors. A total of 15 excerpts were coded for leadership buy-in and the hierarchy of the surgical specialty, with 11/15 excerpts from faculty participants. One faculty member alluded to the difficulties in changing their practices when it has not yet been adopted by the entire department. “How do you address these issues, how do you talk about it, should I call my division chief, should I talk to my colleague one on one? And from a resident perspective, if a senior resident does it during rounds and a junior resident realizes that it is wrong, how they address it.”

Participants contemplated the benefits of a curriculum that provides education tailored to the patient population at each institution, as opposed to a standardized curriculum for all participating institutions. Out of 12 excerpts coded for tailoring a curriculum, 50% were from faculty participants and 50% were from resident participants. Overall, there was agreement amongst faculty and residents with regards to the benefits of a tailored curriculum by means of a pre-assessment of each institution’s needs, current practices, and patient population, with over 85% of faculty and residents (10/12 excerpts) supporting this approach. In championing a tailored curriculum that reflects the cultures or ethnicities that present most predominantly, one resident stated:“Every hospital I worked in is very different as far as the minorities that are present in that area. And so maybe the role play focuses more on Hispanics being a large minority population that's quite varied. But maybe my hospital really never treats Hispanic patients…[but] actually Amish patients. And so I think it'd be nice for… information that's more specific towards some populations.”

In 2/12 excerpts, this notion is challenged by the idea that residents will likely move to different hospitals and geographic locations after their training, and thus be expected to work with a different population group. As one faculty stated: “I know that the residency programs in the country are very heterogenous, like some residents may never encounter a non-English speaking patient, but I think at the end of the day, these residents are going to go out into the world and practice, and they may end up in a place where minorities are the majority. So, I think it should be standardized… Because they may do fellowship or go into practice somewhere that you need that kind of cultural dexterity. And if you also make it program based, or different type of curriculum, then that’s going to make the whole thing very difficult to implement.”

Existing infrastructure within institutions was discussed as another factor impacting the application of cultural dexterity practices. Overall, 17 excerpts were coded across both sets of focus groups that describe a variety of institution-specific barriers and facilitators. Approximately 65% (11/17 excerpts) of the discussion was centered around the amount of time spent with an interpreter. Both faculty and residents cited this time as a barrier in treating patients with limited English proficiency. They described efficiency as a necessity in managing their responsibilities as providers, which is affected by access to interpreter services and the amount of time allotted to each patient encounter in the clinic. As one resident explained:“…as a resident, I feel slammed. I'm busy. My job is to be efficient, [instead of] waiting around or figuring out the phone situation. So again, supporting us in saying like, "Hey, this is how the hospital is going to make this easier for you." Would be one way to make me think, "Okay, you're not just piling more stuff on the resident.””

Discussion

In this study of potential facilitators and barriers to implementing a cultural dexterity curriculum, surgical faculty and residents identified 3 major themes: institutional support, resident engagement, and applicability to practice. All of these themes emerged from discussions with both faculty and residents, highlighting the importance of addressing these factors when planning to implement a surgical education curriculum.

Creating an opportunity for residents to engage in the curriculum

The logistics of incorporating a cultural dexterity curriculum into the existing training program framework for residents were considered important to its overall uptake. Suggestions to increase resident attendance included requiring participation as established by the program director or department chair, and incorporation of didactic sessions within protected education time. These findings are supported by studies demonstrating that the importance or relevance of cultural competency is conferred by requiring the training in residency programs.7,15 Given these findings, we expect all residents at participating PACTS sites to participate in the educational components of the curriculum – even those who opt out of the evaluation portion of the trial. Additionally, given competing priorities of other educational modules and clinical responsibilities, the modules should be efficient and the platforms for delivery must appeal to a variety of learning styles. As exemplified by another study evaluating a professionalism and communication skills curriculum for surgical house staff, efforts must be taken to ensure sufficient time to effectively teach the knowledge and skills, but not so much time as to burden residents who already have busy clinical demands.16 In order to enhance opportunities for residents to engage in the PACTS curriculum, program directors at each of the institutions participating in the trial were directly involved in the planning, development, and implementation of the curriculum in their respective residency training programs.

Demonstrating the importance of cross-cultural training

Resident buy-in was cited as one of the most important barriers to overcome in obtaining resident engagement. In order to recognize the importance of the curriculum, it was suggested that residents be exposed to their personal biases. Further, data should be provided to report disparities in patient care. A previous study identified negative attitudes towards cross-cultural training amongst surgery residents, as many residents believed they had already acquired the necessary patient care, professionalism, and interpersonal and communication skills during medical school training.16 Participants were in agreement in their support of a pre-curriculum evaluation to identify gaps in knowledge, as well as the addition of relevant patient data and outcomes in order to address any preconceived perceptions of the cross-cultural training. Additionally, a list of best practices for cross-cultural care and supplemental reading material related to specific patient populations were described as essential resources for the curriculum. As identified in a study evaluating cultural competency education for pediatric residents and faculty, culture-specific knowledge and identification of best practices were most frequently requested to be included in training.18 The curriculum has been updated to incorporate a pre-assessment of existing biases through the IAT, a summary of best practices for cross-cultural care, supplemental literature, and physical reference materials to support cultural dexterity practices that can be applied at all institutions. Additionally, the curriculum is rooted in the principle of cultural dexterity, which is a paradigm shift from engaging patient-provider encounters with prior cultural beliefs of the patient’s background to a skillset focused on understanding the provider’s biases and the historical, structural, and institutional matters that limit optimal care for various populations, while learning how to navigate the encounter to enhance the bi-directional communication.

Establishing an environment for sustainability

It is apparent that departmental and institutional support are necessary to ensure the application of cultural dexterity attitudes and skills in the clinical setting. Given the hierarchical nature of the surgical specialty, both residents and faculty cited barriers in implementing system-wide changes from the bottom up. Other studies identified a lack of faculty role models as a key barrier, which speaks to the importance of leadership and the surgical hierarchy influencing the ability of residents to apply.2,19,20 On an institutional level, discussions centered around the priorities of efficiency competing with additional time spent with an interpreter for patients with limited English proficiency. Recommendations to establish an environment for sustainability included more access to interpreter services, policy changes in the amount of time allocated for a patient encounter in the clinic, and buy-in from ancillary staff who facilitate surgical care in different roles. These recommendations are supported by residents who evaluated an earlier version of the PACTS curriculum in a prior study by Udyavar et al1 and led to the creation of informational handouts (visual abstracts) about the PACTS trial which were provided to faculty during implementation of the curriculum and data collection.

This study has several limitations. First, the surgery faculty focus groups took place in July 2018, seven months prior to the surgery resident focus groups in February 2019. Modifications were made to the curriculum in the time between the faculty and resident focus groups, thus diminishing the consistency and comparability between the two groups. However, the most prominent themes that participants identified are likely applicable to the implementation of surgical residency curriculum, related to communication and non-technical skills. Additionally, faculty focus groups were able to review all four curriculum modules, while the resident participants evaluated only one e-learning module and corresponding case-based experiential learning session. As such, the faculty had more context regarding the curriculum, in particular because the modules were designed to be delivered sequentially and some concepts build upon those in previous modules. Ultimately, our intent is to improve the curriculum with feedback obtained by these focus groups and implement the curriculum broadly at institutions training surgical residents. With cultural dexterity serving as the core of the curriculum it will offer wideranging flexibility and be adaptable to various institutions. The curriculum will be available to all institutions training surgical residents once the PACTS trial is complete.

Second, focus groups were facilitated by different investigators with different focus group interview guides for the faculty and resident groups. Differences in focus group facilitators and interview guides could lead to different responses and group dynamics, thus reducing consistency between the two groups. The interview guides for both the faculty and resident focus groups included specific questions pertaining to the logistical aspects of the curriculum’s delivery as well as perceived facilitators and barriers in implementing the curriculum. The present analysis was restricted to feedback specific to the logistics of implementing the curriculum rather than purely curriculum content.

While the perspectives shared by the faculty and the residents were not directly opposed to each other, there were certain views that were nearly unilaterally expressed by the faculty. Those include the importance of having local champions at each institution, and the impact of leadership buy-in given the hierarchical nature of the surgical specialty. The views that were nearly unilaterally expressed by the residents include the necessity of patient testimonials and patient outcomes to support the principles taught in the curriculum, as well as the impact of pre-existing impressions of role playing as a factor in buy-in. Although these differences reflect the inherent dissimilarities in perspectives amogst faculty and residents, in combination, these views provide a more comprehensive assessment of the curriculum.

Finally, our method of recruitment by convenience sampling increases risk for selection bias in our study cohort. Both faculty and residents who agreed to participate may have had a higher baseline personal interest in cultural competency and/or already believed in its importance. However, these potential personal biases towards the curriculum content should not significantly influence what participants perceive to be barriers and facilitators to implementation. The participants were also recruited as part of the Academic Surgical Congress and Association for Academic Surgery’s Executive Council, and although the faculty and residents were from various regions in the U.S., most are from academic medical centers or have an interest in academic surgery and not representative of community-centered programs. We are mindful of this limitation and will need to incorporate representation from community-centered programs and other non-academic medical centers as we consider broad scale implementation.

In summary, our findings show that when planning to implement a cultural dexterity curriculum for surgical residents, it is crucial to consider themes of institutional support, resident engagement, and applicability to practice. These three tenets, as identified by both surgical faculty and residents, are critical for ensuring an impactful and clinically significant education program.

Highlights.

Surgical faculty and surgical resident perspectives on potential facilitators and barriers to implementing a surgical education curriculum

A novel curriculum for surgical residents aimed at mitigating disparities in surgical outcomes through a cultural dexterity framework

Institutional support, resident engagement, and applicability to practice are necessary for ensuring an impactful and clinically significant education program

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work was supported by the NIH National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (R01-MD011685).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Udyavar R, Smink DS, Mullen JT, et al. Qualitative Analysis of a Cultural Dexterity Program for Surgeons: Feasible, Impactful, and Necessary. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(5): 1159–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissman JS, Betancourt J, Campbell EG, et al. Resident physicians’ preparedness to provide cross-cultural care. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294(9):1058–1067. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.9.1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haider AH, Scott VK, Rehman KA, et al. Racial disparities in surgical care and outcomes in the United States: A comprehensive review of patient, provider, and systemic factors. J Am CollSurg. 2013;216(3). doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betancourt JR, Corbett J, Bondaryk MR. Addressing Disparities and Achieving Equity Cultural Competence, Ethics, and Health-care Transformation. Chest. 2014;145(1):143–148 doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beach MC, Cooper LA, Robinson KA, et al. Strategies for improving minority healthcare quality. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2004;(90):1–8. doi: 10.1037/e439452005-001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (with CD). Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2003. doi: 10.17226/12875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Effectiveness of the Surgery Core Clerkship Flipped Classroom: a prospective cohort trial- Clinical Key. https://www-clinicalkey-com.proxyhu.wrlc.org/#!/content/playContent/1-s2.0-S0002961015006042?returnurl=null&referrer=null. Accessed January 21, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Gillispie V Using the flipped classroom to bridge the gap to generation Y. Ochsner J. 2016;16(1):32–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ly CL, Chun MBJ. Welcome to Cultural Competency Surgery’s Efforts to Acknowledge Diversity in Residency Training. J Surg Educ. 2012;70:284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kensinger CD, McMaster WG, Vella MA, Sexton KW, Snyder RA, Terhune KP. Residents as educators: A modern model. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(5):949–956. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibbs GR. In : The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis. SAGE Handb Qual Data Anal. 2013:277–294. doi: 10.4135/9781446282243.n19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leech NL, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Beyond Constant Comparison Qualitative Data Analysis: Using NVivo. Sch Psychol Q. 2011;26(1):70–84. doi: 10.1037/a0022711 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creswell JW, Miller DL. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Pract. 2000;39(3):124–130. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, Olson K, Spiers J. Verification Strategies for Establishing Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. Int J Qual Methods. 2002; 1 (2): 13–22. doi: 10.1177/160940690200100202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nosek BA, Greenwald AG, Banaji MR. Understanding and Using the Implicit Association Test: II. Method Variables and Construct Validity. 2005. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chun MBJ, Young KGM, Honda AF, Belcher GF, Maskarinec GG. The Development of a Cultural Standardized Patient Examination for a General Surgery Residency Program. 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2012.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hochberg MS, Kalet A, Zabar S, Kachur E, Gillespie C, Berman RS. Can professionalism be taught? Encouraging evidence. Am J Surg. 2010;199:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rule ARL, Reynolds K, Sucharew H, Volck B. Perceived Cultural Competency Skills and Deficiencies Among Pediatric Residents and Faculty at a Large Teaching Hospital. Hosp Pediatr. 2018;8(9):554–569. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2017-0110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacDonald ME, Carnevale FA, Razack S. Understanding what residents want and what residents need: The challenge of cultural training in pediatrics. Med Teach. 2007;29(5):464–471. doi: 10.1080/01421590701509639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shapiro J, Hollingshead J, Morrison E. Self-perceived attitudes and skills of cultural competence: A comparison of family medicine and internal medicine residents. Med Teach. 2003;25(3):327–329. doi: 10.1080/0142159031000100454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]