Abstract

Background

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) imaging of the Synaptic Vesicle glycoprotein (SV) 2A is a new tool to quantify synaptic density. [18F]UCB-H was one of the first promising SV2A-ligands to be labelled and used in vivo in rodent and human, while limited information on its pharmacokinetic properties is available in the non-human primate. Here, we evaluate the reliability of the three most commonly used modelling approaches for [18F]UCB-H in the non-human cynomolgus primate, adding the coupled fit of the non-displaceable distribution volume (VND) as an alternative approach to improve unstable fit. The results are discussed in the light of the current state of SV2A PET ligands.

Results

[18F]UCB-H pharmacokinetic data was optimally fitted with a two-compartment model (2TCM), although the model did not always converge (large total volume of distribution (VT) or large uncertainty of the estimate). 2TCM with coupled fit K1/k2 across brain regions stabilized the quantification, and confirmed a lower specific signal of [18F]UCB-H compared to the newest SV2A-ligands. However, the measures of VND and the influx parameter (K1) are similar to what has been reported for other SV2A ligands. These data were reinforced by displacement studies using [19F]UCB-H, demonstrating only 50% displacement of the total [18F]UCB-H signal at maximal occupancy of SV2A. As previously demonstrated in clinical studies, the graphical method of Logan provided a more robust estimate of VT with only a small bias compared to 2TCM.

Conclusions

Modeling issues with a 2TCM due to a slow component have previously been reported for other SV2A ligands with low specific binding, or after blocking of specific binding. As all SV2A ligands share chemical structural similarities, we hypothesize that this slow binding component is common for all SV2A ligands, but only hampers quantification when specific binding is low.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13550-021-00777-8.

Keywords: SV2A, Cynomolgus non-human Primates, PET, Synaptic imaging

Background

Synaptic vesicle glycoproteins (SV) are critical to proper nervous system function and have been demonstrated to be involved in vesicle trafficking. They belong to the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) of transporters and consist of a 12-transmembrane glycoprotein and a cytoplasmic N-terminal region containing a long sequence that varies among the three SV2 isoforms (SV2A, SV2B and SV2C) [1, 2]. SV2A and -B are highly homologous to each other, with SV2A showing ubiquitous expression in both excitatory and inhibitory synapses throughout the entire brain [3, 4]; in contrast, SV2B and SV2C are present in a more restricted pattern in the brain, and in only a subset of synapses [2, 5]. The hypothesis of SV2 as vesicular transport protein is based on a significant homology to other transport proteins, however no endogenous substrate has been reported [3], neither has any transport activity been demonstrated [2]. Another hypothetical function is vesicle trafficking and exocytosis, and the modification of the synaptic function [4–6].

Lynch and coworkers identified SV2A as the brain-binding site of the anti-epileptic drug levetiracetam (LEV, Keppra®, UCB Pharma Ltd., Slough, Berkshire, UK) [7]. Seizure protection by LEV and other SV2A ligands strongly correlates with the degree of SV2A occupancy in vivo [3, 8]. However, the site of SV2A-LEV interaction and the mechanism of action remain unclear. LEV does not cause a SV2A conformational state change and it is assumed that SV2A transports LEV or LEV prevents transport of the endogenous substrate [4], as one of the functional consequences of LEV binding to SV2A in brain slices is reduced exocytosis [6]. With the aim of a better understanding of the role of SV2A in epilepsy and of studying SV2A in diseases of the central nervous system, several SV2A-specific ligands have been developed [9], [18F]UCB-H being one of the first to be labelled [10], subsequently characterized in the rodent [10, 11], and in the human brain [12]. The demonstration of the co-localization of SV2A with other synaptic markers using [11C]-UCB-J [13], showed the potential of in vivo imaging of the synaptic density using Positron Emission Tomography (PET), and led recently to the development of new [18F]-labelled ligands [9, 14–19]. Preclinical characterization of [18F]UCB-H has mostly been done in the rodent brain [20–22], while in non-human primates (NHP) limited data is available [23, 24]. In humans a preliminary study was performed on four healthy subjects [12], preceding a clinical study in Alzheimer’s patients [25]. Here, we aimed to characterize pharmacodynamics properties of [18F]UCB-H in non-human cynomolgus primates in complement to these existing data and to discuss the obtained results in the light of the current state of SV2A PET ligands.

Material and methods

Animals

Experiments were conducted on four young adult male cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis, 5.2 ± 1.1 kg, 4.4 ± 0.7 years). Animal use procedures were in accordance with the recommendations of the European regulations (EU Directive 2010/63) and approved by the local ethical committee (CETEA n°44), and the French Ministry of Education and Research (NEUROMODEL: APAFIS#389-20150327162135690v02). The experimental data reported in this study are in compliance with the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting in Vivo Experiments) guidelines [26].

Radiochemistry

Radiosynthesis of the enantiomeric ligand [18F]UCB-H was realized through a one-step radiolabelling of a pyridyliodonium precursor as previously described [27]. [18F]UCB-H was formulated in 0.9% aqueous saline with 3% ethanol (v/v). The radiochemical purity of [18F]UCB-H was > 98% and the molar activity at the time of injection was 54 ± 32 GBq/μmol.

PET imaging

Experimental design

All four non-human primates (NHP) underwent a 2-h (2 h) test and retest PET scan; two NHP underwent an additional 4-h (4 h) retest PET scan. Three NHP underwent one 4-h (4 h) displacement PET scan. Arterial blood sampling was performed during test and retest scans with PET imaging spaced by at least 3 weeks between each scan. To this end, the femoral artery opposite to the saphenous vein used for radioligand injection was cannulated. For the 2-h (2 h) scans, we collected in total 28 blood samples of 1 mL: 16 samples during the first 5 min followed by 3 samples every 5 min and 11 samples every 10 min. For the 4 h scans, we collected an additional 6 samples every 20 min during the last two hours (34 samples in total). Larger samples (2 – 3 mL) were collected at 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120 min (2 h) and at 180, 240 min (4 h) for metabolite analysis. Displacement of [18F]UCB-H was done by intravenous (IV) administration 90 min after [18F]UCB-H injection of a bolus of 30 mg/kg LEV, or of 80 µg/kg (≈250 nmol/kg) or 5 mg/kg (≈15 µmol/kg) of cold [19F]-UCB-H. Full experimental design of all NHP is outlined in Additional file 1: Table 1.

Drug formulation

Solvents and LEV (C8H14N2O2; MM 170.21 g/mol) were obtained at Sigma-Aldrich® (France), and [19F]-UCB-H (C16H12F4N2O; MM 324.28 g/mol) was synthesised as previously described [27]. Injectable solutions of [19F]-UCB-H for displacement studies were prepared with a mixture of Tetrahydrofuran (THF), Médialipide® and glucose at 2.5% as previously described [28]. LEV was dissolved in a glucose solution of 2.5% to reach a concentration of 90 mg/mL.

PET imaging

PET imaging was performed on the microPET FOCUS220 (Siemens) under standard anesthesia and monitoring procedures [29]. Data acquisition started with the IV bolus injection of [18F]UCB-H (32.9 ± 1.0 MBq/kg, 0.35 ± 0.07 µg/kg). Dynamic PET images were reconstructed using standard OSEM-2D algorithms while correcting for radioactive decay, scatter, attenuation and detectors inhomogeneity, which were measured prior to PET scanning using respectively 57Co and 68Ge external sources.

Blood measurement & analysis

Plasma was separated from whole-blood by centrifugation (5 min, 2054xg, 4 °C) and 50 µL of plasma and whole-blood were counted using a PET cross-calibrated gamma well counter (WIZARD2, PerkinElmer, France) to obtain the whole-blood and plasma activity curves. All data were corrected for radioactive decay from the injection time. For the larger blood samples, 500 µL plasma was deproteinized with acetonitrile. The supernatant was injected in high-performance liquid chromatography, equipped with an Atlantis® T3 5 μm 4.6 × 150 mm column (Waters) and an Atlantis® T3 5 μm 3.9 × 5 mm pre-column (Waters), with an LB-513 radioactivity flow detector (Berthold, La Garenne Colombes, France, MX Z100 cell). The eluant was collected in intervals of 15 s (fraction collector III, Waters, France) and counted in the gamma well counter (WIZARD2, PerkinElmer, France) to measure total activity. [18F]UCB-H parent fraction was calculated as a percentage of the total radioactivity (metabolites and parent).

For each animal, a 2-exponential decay function was fitted to [18F]UCB-H parent fraction, which was time multiplied with the plasma activity curve to obtain the metabolite-corrected arterial plasma input function (mcAIF) used for the kinetic modeling.

The fraction of [18F]UCB-H in NHP plasma samples not bound to plasma protein was measured before PET injection using a previously described ultrafiltration method [30]. In brief, standard amounts of [18F]UCB-H (≈15 kBq) were added to 200 μL plasma that was applied to Microcon® filtration devices containing an YM-10 membrane (Millipore, France). The devices were centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 g (Sigma 2-16KL, France). [18F]UCB-H activity concentration in the resulting ultrafiltrate (≈70 μL, CFP) and a sample of plasma (CP) were counted. The free fraction (fp) was calculated as: fp = CFP/CP and measured in triplicates.

PET data analysis

PET image analysis was performed using PMOD software version 3.8 (PMOD Technologies Ltd., Zurich, Suisse). After individual co-registration of PET-MR images, a cynomolgus atlas published by Ballanger and coworkers [31] was normalized to PET images to extract time activity curves in different brain regions. Volumes of interest (VOI) were cerebral white matter (16.7 cm3), striatum (0.24 cm3), thalamus (0.89 cm3), cerebellum (3.83 cm3), frontal—(2.50 cm3), parietal—(5.35 cm3), and temporal (8.22 cm3) cortex, and whole brain (72.2 cm3) as a composite region of all regions in the atlas. [18F]UCB-H pharmacokinetics were evaluated by analyzing the time activity curves of the test- and retest scans using 1- and 2-tissue compartment models (unconstrained and constrained with global K1/k2 coupled fit across all regions, further referred to as 2TCM and 2TCM-c) [32], and Logan graphical analysis with a fixed t* at 60 min [33] using the arterial plasma input function corrected for radio-metabolites to derive the volume of distribution in each region. Percentage standard error (%SE) was estimated from the theoretical parameter covariance matrix. Only reliable estimates (%SE less than 25%) were included in the current analyses. For the three drug studies, percent displacement of the total activity in the whole brain was estimated relative to an average baseline constructed from the two 4 h baseline studies. Briefly, Standardized Uptake Value (SUV) time activity curves (TACs) were calculated for the two baseline and the three displacement studies. Then, each curve was normalized to the SUV at t = 90 min, corresponding to the timeframe immediately before the administration of the drugs in the displacement studies. Baseline curves were averaged and the percent displacement of total activity was calculated as (baseline-displacement)/baseline at a given time post drug administration (see “Results”).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R software (version 3.3.1.). Plasma, intact parent fraction and time activity curves were statistically compared between subjects using a one-factor variance analysis. Absolute Test–Retest variability (aTRV) of PET quantification parameters was calculated as ABS(test—retest) / AVERAGE(test, retest). Reliability was evaluated using a two-factor mixed model in order to calculate the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) (Package Psych, Version 1.7.8). All values are expressed as average ± standard error of the mean (SEM; significance level was fixed at p < 0.05).

Results

Blood data

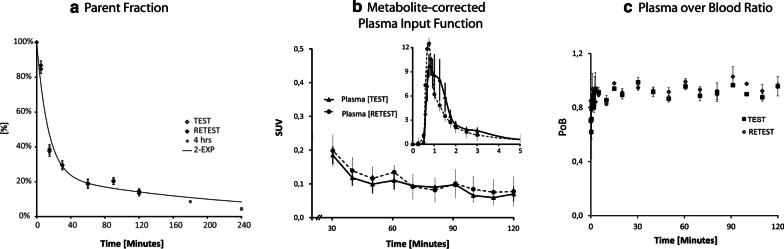

[18F]UCB-H shows a rapid metabolism in the arterial blood with an intact parent fraction of 37 ± 3.9% at 15 min, 29.5 ± 3.4% at 30 min, 19 ± 3.5% at 60 min, 14.6 ± 1.9% at 120 min and 4.4 ± 0.7% at 240 min after tracer injection. The parent fraction was fitted with a two-exponential decay function based on blood data acquired up to 4 h after tracer injection, and on the residuals (Fig. 1a). Whole blood and plasma-input functions were highly consistent between animals with stable plasma to whole-blood ratio of 0.90 ± 0.05 over the entire 120-min acquisition period (Fig. 1b, c). Plasma free parent fraction (fp) measured by ultrafiltration before tracer injection was 42.6 ± 1.6%.

Fig. 1.

Blood measures after i.v. [18F]UCB-H injection in the cynomolgus NHP in test- and retest studies. Parental fraction (in %) was fitted with a two-exponential decay function based on blood data acquired up to 4 h after tracer injection (a). Average (± SEM) metabolite-corrected plasma input function (b) and plasma to whole blood ratio (c) were highly consistent between and within animals

Brain kinetics

Time activity curves

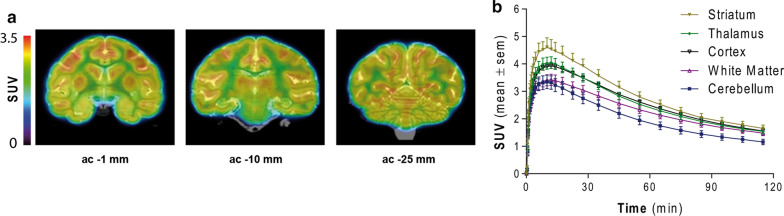

Figure 2b shows representative time-activity curves (TACs) in a subset of brain regions. [18F]UCB-H entered rapidly in the brain, reaching maximal uptake 5 to 15 min after injection, followed by a relatively slow terminal elimination phase. Highest SUV uptake was observed in the striatum, followed by the thalamus and the cortical regions.

Fig. 2.

a Representative 60–120 min summed coronal PET images at ac -1 mm, ac – 10 mm and ac -25 mm coregistered to T2-weighted MR images. b Average (± SEM) TAC in striatum, thalamus, cortex, white matter and cerebellum

Compartment modeling

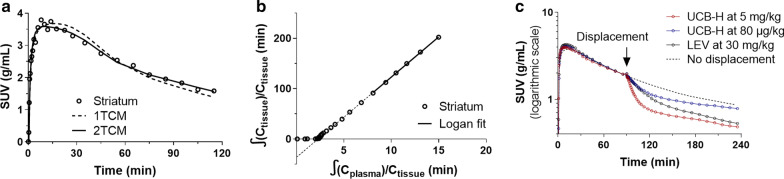

According to the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the two-compartment model (2TCM) fitted better the TACs compared to the one-compartment model (1TCM) (AIC1TCM = 21.9 ± 1.8 vs. AIC2TCM = 0.71 ± 1.73). However, across all scans and VOI, VT estimated by 2TCM was only quantifiable (%SE < 25%) in 50% of cases (Fig. 3a and Additional file 1: Fig. 1). There was high uncertainty on the estimation of k3 and even higher for k4 where the estimate tended toward 0 in 30% of cases independent of the VOI, with therefore unreliable estimates of k3/k4 in > 80% of cases. 2TCM-c was more stable and enabled estimation of VT in 80% of cases, and of k3/k4 in 70% of cases. Logan graphical analysis fitted robustly all TACs, with a representative plot shown in Fig. 3b.

Fig. 3.

a According to the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the two-compartment model (2TCM, full line) fitted better the TACs (here striatum, circles) compared to the one-compartment model (1TCM, dashed line). b Logan graphical linear fit of striatal TAC (circles) with t* fixed at 60 min. c Dose dependent displacement of [18F]UCB-H at 90 min after radioligand injection by [19F]UCB-H at 80 µg/kg (red) and 5 mg/kg (blue). Slower brain penetrance of LEV (30 mg/kg, black) induced a slower displacement

Figure 4a shows correlation plots between VT estimates obtained with Logan, 1TCM, 2TCM-c, and the cases for which 2TCM converged. Good agreement was found between 2TCM and Logan or 2TCM-c estimates (R2 = 0.90 and R2 = 0.91, respectively) with a slight overall underestimation of VT (-3 ± 1% for Logan, and -4 ± 1% for 2TCM-c), while 1TCM had a moderate correlation with 2TCM (R2 = 0.68) and overall larger bias for VT (-9 ± 1%) (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

a Linear correlations show a better agreement between 2TCM, Logan and 2TCM-c as compared to 1TCM. b Overall, Logan and 2TCM-c provide lower underestimation of VT (-3 ± 1% and -4 ± 1% respectively), as compared to 1TCM (-9 ± 1%)

A summary of VT obtained by the different methods (2TCM, 2TCM-c, 1TCM and Logan) for different regions is shown in Table 1. aTRV and ICC were calculated for VT obtained by 2TCM-c, and Logan. Overall, aTRV were lower, and ICC were higher for Logan (~ 11% and ~ 0.6) compared to 2TCM-c (~ 17% and ~ 0.4) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Regional estimates of VT- and BPND for test-, and retest scans

| Brain region | 2TCM | 2TCM-c | 1TCM | Logan (t* = 60) | 2TCM-c | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VT [mL/cm3] | VT [mL/cm3] | VT [mL/cm3] | VT [mL/cm3] | k3/k4 (BPND) | |||||||||||

| Mean | ± | SEM | Mean | ± | SEM | Mean | ± | SEM | Mean | ± | SEM | Mean | ± | SEM | |

| Striatum | |||||||||||||||

| Test | 15.3 | ± | 2.25 | 15.0 | ± | 1.11 | 14.2 | ± | 1.29 | 15.8 | ± | 1.15 | 1.16 | ± | 0.36 |

| Retest | 14.1 | ± | 0.96 | 15.3 | ± | 0.93 | 14.8 | ± | 0.61 | 15.7 | ± | 1.04 | 1.12 | ± | 0.39 |

| Thalamus | |||||||||||||||

| Test | 15.6 | ± | 1.98 | 15.0 | ± | 1.38 | 13.3 | ± | 1.17 | 14.9 | ± | 0.99 | 1.03 | ± | 0.25 |

| Retest | 13.0 | ± | 1.08 | 14.2 | ± | 1.06 | 13.4 | ± | 0.60 | 14.3 | ± | 1.11 | 0.97 | ± | 0.36 |

| Cerebellum | |||||||||||||||

| Test | 10.6 | ± | 0.08 | 9.70 | ± | NA | 9.8 | ± | 0.78 | 11.2 | ± | 0.68 | 1.24 | ± | NA |

| Retest | 12.3 | ± | NA | 13.3 | ± | 2.97 | 10.4 | ± | 0.82 | 11.1 | ± | 0.75 | 1.22 | ± | 0.42 |

| White matter | |||||||||||||||

| Test | 14.0 | ± | 2.37 | 13.8 | ± | 1.69 | 12.3 | ± | 1.13 | 13.9 | ± | 1.00 | 1.25 | ± | 0.16 |

| Retest | 12.6 | ± | 1.08 | 13.7 | ± | 1.61 | 12.5 | ± | 0.68 | 13.6 | ± | 1.23 | 0.83 | ± | 0.47 |

| Frontal cortex | |||||||||||||||

| Test | 16.3 | ± | 3.68 | 14.8 | ± | 2.15 | 13.8 | ± | 1.64 | 15.0 | ± | 1.59 | 1.25 | ± | 0.32 |

| Retest | 13.1 | ± | 0.66 | 14.7 | ± | 1.37 | 13.8 | ± | 1.15 | 14.8 | ± | 1.87 | 1.32 | ± | 0.40 |

| Temporal cortex | |||||||||||||||

| Test | 13.9 | ± | 1.60 | 14.8 | ± | 1.30 | 12.9 | ± | 0.83 | 14.1 | ± | 0.77 | 1.00 | ± | 0.24 |

| Retest | 14.0 | ± | 0.01 | 13.1 | ± | 0.76 | 13.0 | ± | 0.52 | 13.9 | ± | 0.91 | 0.97 | ± | 0.54 |

| Parietal cortex | |||||||||||||||

| Test | 15.5 | ± | 3.24 | 15.4 | ± | 1.54 | 14.3 | ± | 1.41 | 15.4 | ± | 1.35 | 1.08 | ± | 0.26 |

| Retest | 13.6 | ± | 0.36 | 16.1 | ± | 1.40 | 14.8 | ± | 0.75 | 15.7 | ± | 1.43 | 1.17 | ± | 0.29 |

VT was estimated using 2TCM, 2TCM-c, 1TCM and Logan. BPND was estimated by k3/k4 using a 2TCM-c. Only estimates at < 25%SE were included. NA = undetermined

Table 2.

Summary of aTRV and ICC values for VT estimates by 2TCM-c and Logan

| Brain region | 2TCM-c VT (mL/cm3) | Logan (t* = 60) VT (mL/cm3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aTRV | ICC | aTRV | ICC | |

| Striatum | 12% | 0,52 | 11% | 0.67 |

| Thalamus | 18% | 0,05 | 12% | 0.61 |

| Cerebellum | NA | NA | 14% | 0.32 |

| White matter | 24% | 0.43 | 13% | 0.62 |

| Frontal cortex | 11% | 0.84 | 11% | 0.89 |

| Temporal cortex | 25% | NA | 13% | 0.61 |

| Parietal cortex | 19% | 0.38 | 12% | 0.75 |

aTRV and ICC calculation of the most relevant VT estimates obtained with 2TCM-c and Logan. Only estimates at <25%SE were included. For 2TCM, only NHP2 had acceptable estimates in both test-, and retest conditions.

As surrogate of BPND, k3/k4 obtained by 2TCM-c, was estimated to be 1.07 ± 0.02 on average; regional test, and retest values are detailed in Table 1. The tissue influx parameter of [18F]UCB-H (K1), a measure of blood flow and tracer extraction, was equal for 2TCM and 2TCM-c and estimated to 0.37 ± 0.01 mL/cm3/min in grey matter regions. The average VND (K1/k2 from 2TCM-c) over all VOIs and animals was 7.89 ± 1.23 mL/cm3, with a free fraction in tissue fND of 6.1 ± 1.3%. Additional file 1: Table 2 summarizes all individual estimates (< 25%SE) by 2TCM, 2TCM-c, 1TCM and Logan.

Displacement studies

In all brain regions, [18F]UCB-H uptake was displaced by [19F]UCB-H in a dose-dependent manner with the displacement occurring rapidly; brain penetration of [19F]UCB-H is fast with maximum uptake 5–15 min after injection. Low dose of [19F]UCB-H (80 µg/kg, more than 100 fold [18F]UCB-H mass dose) resulted in ~ 20–25% displacement, and high dose of [19F]UCB-H (5 mg/kg) displaced close to 50% of [18F]UCB-H, where both measurements were estimated at 35 min after injection of cold [19F]UCB-H when the displacement was maximum (Fig. 3c).

LEV administration at pharmacological dose has a much slower brain penetration [34], and a dose of 30 mg/kg induced a slower displacement of [18F]UCB-H of ~ 40% as estimated at 150 min after injection of LEV (at the end of the 240 min acquisition) (Fig. 3c).

Discussion

The current study evaluates [18F]UCB-H pharmacokinetics in healthy NHPs. We demonstrated similar metabolism in NHP as previously described in the rodent, human and rhesus monkey [11, 12, 23]. We have shown that [18F]UCB-H equilibrates rapidly between whole blood and plasma, with high availability in plasma (fp of 42.6 ± 1.6%). Similar to data obtained in rodent and human [11, 12], we observed in the NHP a good brain penetrance with ubiquitous brain uptake. Tissue influx parameters of [18F]UCB-H were comparable to other SV2A radioligands for grey matter regions [13, 24]. Even though a better goodness of fit of the TACs was obtained with 2TCM compared to 1TCM, not all TACs could be fitted with 2TCM. Previously, this has been the criteria to preconize the graphical method of Logan [12]. Here we demonstrate that Logan provides reliable estimates of VT with a relatively low aTRV (~ 12%), although larger than that reported for [11C]UCB-J in humans (~ 4%)[35], and a small bias relative to 2TCM of ~ -3% compared to ~ -9% for 1TCM. In a preliminary rhesus NHP study, Zheng and colleagues alternatively proposed 1TCM and the multilinear analysis method (MA1) to obtain reliable estimates of VT for [18F]UCB-H [23]. Here, in the cynomolgus NHP, we demonstrated an aTRV above 10% for 1TCM and a poor reliability. For MA1 we found aTRV of VT (~ 11%), but a larger negative bias (~ -8%) compared to Logan (data not shown).

We observed that the convergence issue with 2TCM was mainly due to instability of the k4 estimate tending to zero in ~ 30% of all cases, independent of the regions. Brain kinetics of SV2A ligands [11C]UCB-J [35, 36] and [18F]SynVesT-1 (a.k.a [18F]SDM-8, [18F]MNI-1126) [14] have been reported as better described by 2TCM in human, but were better modeled with 1TCM in cynomolgus or rhesus monkeys [24, 37, 38], and [11C]UCB-A was better described with 1TCM at baseline in pigs but 2TCM was required after blocking of the specific signal [39]. Interestingly, all authors reported issues with 2TCM similar to those reported here, namely lack of convergence or large standard error for VT [14, 35, 36, 39], with large uncertainty on k4 and values close to 0 [14, 35]. As a consequence, 1TCM for [11C]UCB-J and [18F]SynVesT-1 [14, 35], and Logan graphical analysis for [11C]UCB-A [39] was selected as method of choice. We reported here similar issues with the use of 2TCM for [18F]UCB-H. We obtained similar AIC for reversible or irreversible 2TCM, and spectral analysis indicated a component at the edge of the frequency range (data not shown), suggesting a small slow component for [18F]UCB-H. Although this component could reflect penetrating metabolites, inaccuracy of metabolite correction or vascularity activity correction, its exact nature remains unclear. Given the similarity in chemical structures between the current SV2A ligands and the aforementioned results reported in the literature, we hypothesize that this slow component is likely common between all these ligands. Moreover, this component is problematic when the specific signal is low (low affinity ligands or blocking studies) and when kinetics can only be described with 2TCM. This was nicely illustrated with [18F]MNI-1126 (high affinity of the (R)-enantiomer), [18F]MNI-1038 (racemate) and [18F]MNI-1128 (low affinity of the (S)-enantiomer) [24, 40], where 1TCM was the best model for [18F]MNI-1126, but 2TCM had to be used both for [18F]MNI-1038 and [18F]MNI-1128 (lower specific signal), with very low k4 for [18F]MNI-1128 [24]. Here, similarly to [11C]UCB-A [39], the method of choice for [18F]UCB-H was Logan graphical analysis, as 1TCM was not adequate due to its lower affinity compared to other SV2A radioligands.

We performed homologous (with [19F]UCB-H) and heterologous (with reference compound LEV) displacement studies to evaluate the reversibility of [18F]UCB-H binding. The total uptake of [18F]UCB-H was clearly displaceable, and in a dose-dependent manner by [19F]UCB-H up to 50% of the total uptake at the highest dose tested (5 mg/kg). Based on [18F]UCB-H brain uptake curves and an fND of ~ 6%, we have a maximum free concentration of UCB-H of ~ 2.5 mM after administration 5.0 mg/kg. For UCB-H, in vitro Ki of 9 nM in human brain [40] and in vivo KD of 30 nM in NHP [38] were reported, and conservatively considering a KD of 30 nM, near full saturation of SV2A would be expected (> 98% occupancy) at a dose of 5 mg/kg and a free concentration of 2.5 mM. We have reported a maximum displacement of the total uptake of 50% with UCB-H, indicating that only about half of the total uptake is displaceable for [18F]UCB-H; therefore, BPND would be expected close to 1.0. Although imperfect because of all the microparameters correlations, k3/k4 from 2TCM with coupled fit K1/k2 was taken here as a surrogate of BPND to estimate the size of the specific signal and compare to previously reported results with other ligands. The expected BPND close to 1.0 is in agreement with the average value for k3/k4 of 1.1 reported in Table 1. Lower BPND values were reported in humans [12], however the binding potentials were derived relative to the centrum semiovale and would likely be higher if calculated using the true VND [14]. Finally, the displacement study with LEV evidenced its slower brain penetrance compared to UCB-H, with a displacement of the total uptake of ~ 40% measured 2.5 h after 30 mg/kg i.v. LEV administration, which would correspond to an occupancy of ~ 75–80% of SV2A in agreement with values in the literature [14, 24, 38]. We observed some displacement in the white matter both with [19F]UCB-H and LEV. This is likely due to high spill-in from cortical regions rather than true specific signal in the white matter, as indicated by the higher than expected uptake and VT [12]. Here, we coregistered T2-weighted MR-PET images to the Ballanger template [31] and used the inverse transformation to extract TACs from the PET images. Cynomolgus brains have relatively small white matter regions, with some inter-animal variability. Therefore, this approach appeared less precise to segment white matter regions, and prone to partial volume effect; as such, the current data set did not allow to use or evaluate the utility of the white matter as a reference region.

Altogether, our data confirm similar brain penetration and non-displaceable uptake for [18F]UCB-H as described for [11C]UCB-J [38], [18F]MNI1126 [16] (aka [18F]Synvest-1 [14]). In agreement with previous reports in rhesus NHP [23, 38], VT-estimates and consequently BPND of [18F]UCB-H in cynomolgus NHP are considerably lower (~ 50% lower for VT, and 3 to fourfold lower for BPND) compared to VT and BPND measures with [11C]UCB-J [35, 38] and other [18F]-labelled SV2A radioligands, [18F]synvest1 [14, 16] and [18F]synvest2 [17] (alias [18F]SDM-2 [18]). As a consequence, [18F]UCB-H will be less sensitive to detect small changes compared to the latest SV2A ligands. Nevertheless, a clinical study using [18F]UCB-H in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) patients demonstrated a correlation between lower synaptic density and poorer awareness of memory functioning in Aβ-positive individuals [25], confirming earlier data in AD patients using [11C]UCB-J [41]. Additionally, this [18F]UCB-H clinical study [25] suggested a widespread synaptic decline in AD patients across the neocortex and in some subcortical nuclei, including the basal forebrain, which was confirmed in a comparable but larger cohort of AD patients using [11C]UCB-J [42]. These and other data [43] have demonstrated the potential of the [18F]UCB-H radioligand.

Conclusions

[18F]UCB-H was the first [18F]-labeled SV2A radioligand [10, 11], before a long series of new [18F]-labeled SV2A candidate ligands [17, 18, 24]. Here, we aimed to complete existing data on [18F]UCB-H by pharmacokinetic studies in young NHP. We show that, when specific binding is low, a slow component gives rise to compartment modeling difficulties with 2TCM due to instability of k4 estimation, which in 30% of all cases tends to 0. A similar observation has previously been reported for other SV2A candidate ligands [24, 39]. Graphical analysis allows nevertheless a reliable quantification of VT with acceptable aTRV and bias. Despite a lower sensitivity due to lower BPND, [18F]UCB-H recently provided sound data in a clinical AD study [25], paving the road for synaptic PET imaging using highly specific SV2A ligands in neurodegenerative disorders.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Additional data on experimental design and individual measures.

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to Leopold Eymin and Sophie Lecourtois for animal handling and PET acquisition. They also thank Romina Aron-Badin for animal care support and MRI acquisitions.

Abbreviations

- 1TCM

One-compartment model

- 2TCM

Two-compartment model

- %SE

Percentage standard error

- AIC

Akaike Information Criterion

- aTRV

Absolute Test–Retest variability

- BPND

Non-Displaceable Binding Potential

- fp

Plasma free parent fraction

- LEV

Levetiracetam

- mcAIF

Metabolite-corrected arterial plasma input function

- NHP

Non-human Primates

- PET

Positron Emission Tomography

- TAC

Time-activity curves

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- SUV

Standardized uptake value

- VOI

Volumes of interest

- VT

Total Volume of Distribution

- SV2A

Synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A

Authors' contributions

Radiochemistry: GB, YB, CL; Animal experimentation: MG, MG; PET Imaging & experimental design: SG, NVC; PET Modelling and Analysis: SG, OB, NVC; Scientific writing: OB, NVC; Secured funding: AL, AP, ES, PH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by NeurATRIS: A translational Research Infrastructure for Biotherapies in Translational Neurosciences (Investissement d’Avenir – ANR-11-INBS-0011, A.L.P.)

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Animal use procedures were in accordance with the recommendations of the European regulations (EU Directive 2010/63) and approved by the local ethical committee (CETEA n°44), and the French Ministry of Education and Research (NEUROMODEL: APAFIS#389-20150327162135690v02). The experimental data reported in this study are in compliance with the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting in Vivo Experiments) guidelines [26].

Competing interests

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Olivier Barret and Nadja Van Camp are contributed equally to this work

References

- 1.Bajjalieh SM, Frantz GD, Weimann JM, McConnell SK, Scheller RH. Differential expression of synaptic vesicle protein 2 (SV2) isoforms. J Neurosci. 1994;14(9):5223–5235. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05223.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janz R, Sudhof TC. SV2C is a synaptic vesicle protein with an unusually restricted localization: anatomy of a synaptic vesicle protein family. Neuroscience. 1999;94(4):1279–1290. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00370-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniels V, Wood M, Leclercq K, Kaminski RM, Gillard M. Modulation of the conformational state of the SV2A protein by an allosteric mechanism as evidenced by ligand binding assays. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169(5):1091–1101. doi: 10.1111/bph.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mendoza-Torreblanca JG, Vanoye-Carlo A, Phillips-Farfan BV, Carmona-Aparicio L, Gomez-Lira G. Synaptic vesicle protein 2A: basic facts and role in synaptic function. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;38(11):3529–3539. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartholome O, Van den Ackerveken P, Sánchez Gil J, de la Brassinne BO, Leprince P, Franzen R, et al. Puzzling out synaptic vesicle 2 family members functions. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:148. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loscher W, Gillard M, Sands ZA, Kaminski RM, Klitgaard H. Synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A ligands in the treatment of epilepsy and beyond. CNS Drugs. 2016;30(11):1055–1077. doi: 10.1007/s40263-016-0384-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lynch BA, Lambeng N, Nocka K, Kensel-Hammes P, Bajjalieh SM, Matagne A, et al. The synaptic vesicle protein SV2A is the binding site for the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(26):9861–9866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308208101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillard M, Fuks B, Leclercq K, Matagne A. Binding characteristics of brivaracetam, a selective, high affinity SV2A ligand in rat, mouse and human brain: relationship to anti-convulsant properties. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;664(1–3):36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mercier J, Archen L, Bollu V, Carre S, Evrard Y, Jnoff E, et al. Discovery of heterocyclic nonacetamide synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) ligands with single-digit nanomolar potency: opening avenues towards the first SV2A positron emission tomography (PET) ligands. ChemMedChem. 2014;9(4):693–698. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201300482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bretin F, Warnock G, Bahri MA, Aerts J, Mestdagh N, Buchanan T, et al. Preclinical radiation dosimetry for the novel SV2A radiotracer [18F]UCB-H. EJNMMI Res. 2013;3(1):35. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-3-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warnock GI, Aerts J, Bahri MA, Bretin F, Lemaire C, Giacomelli F, et al. Evaluation of 18F-UCB-H as a novel PET tracer for synaptic vesicle protein 2A in the brain. J Nucl Med. 2014;55(8):1336–1341. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.136143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bahri MA, Plenevaux A, Aerts J, Bastin C, Becker G, Mercier J, et al. Measuring brain synaptic vesicle protein 2A with positron emission tomography and [18 F]UCB-H. Alzheimer's Dementia Transl Res Clin Intervent. 2017;3(4):481–486. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finnema SJ, Nabulsi NB, Eid T, Detyniecki K, Lin SF, Chen MK, et al. Imaging synaptic density in the living human brain. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(348):348–396. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naganawa M, Li S, Nabulsi NB, Henry S, Zheng MQ, Pracitto R, et al. First-in-human evaluation of (18)F-SynVesT-1, a novel radioligand for PET imaging of synaptic vesicle protein 2A. J Nucl Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Mercier J, Provins L, Valade A. Discovery and development of SV2A PET tracers: potential for imaging synaptic density and clinical applications. Drug Discov Today Technol. 2017;25:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Constantinescu CC, Tresse C, Zheng M, Gouasmat A, Carroll VM, Mistico L, et al. Development and in vivo preclinical imaging of fluorine-18-labeled synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) PET tracers. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Cai Z, Li S, Zhang W, Pracitto R, Wu X, Baum E, et al. Synthesis and preclinical evaluation of an (18)F-labeled synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A PET imaging probe: [(18)F]SynVesT-2. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11(4):592–603. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai Z, Li S, Finnema S, Lin S-f, Zhang W, Holden D, et al. Imaging synaptic density with novel 18F-labeled radioligands for synaptic vesicle protein-2A (SV2A): synthesis and evaluation in nonhuman primates. J Nucl Med. 2017;58(supplement 1):547.

- 19.Becker G, Dammicco S, Bahri MA, Salmon E. The rise of synaptic density PET imaging. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 2020;25(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Becker G, Warnier C, Serrano ME, Bahri MA, Mercier J, Lemaire C, et al. Pharmacokinetic characterization of [(18)F]UCB-H PET radiopharmaceutical in the rat brain. Mol Pharm. 2017;14(8):2719–2725. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serrano ME, Bahri MA, Becker G, Seret A, Mievis F, Giacomelli F, et al. Quantification of [(18)F]UCB-H binding in the rat brain: from kinetic modelling to standardised uptake value. Mol Imaging Biol. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Serrano ME, Becker G. Evaluating the in vivo specificity of [(18)F]UCB-H for the SV2A protein, compared with SV2B and SV2C in rats using micropet. 2019;24(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Zheng M-Q, Holden D, Nabulsi N, Lin S-f, Mercier J, Hannestad J, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of 18F-UCB-H, a novel PET imaging tracer for the synaptic vesicle protein 2A. J Nucl Med. 2014;55(supplement 1):1792.

- 24.Constantinescu CC, Tresse C, Zheng M, Gouasmat A, Carroll VM, Mistico L, et al. Development and in vivo preclinical imaging of fluorine-18-labeled synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) PET tracers. Mol Imaging Biol. 2019;21(3):509–518. doi: 10.1007/s11307-018-1260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bastin C, Bahri MA, Meyer F, Manard M, Delhaye E, Plenevaux A, et al. In vivo imaging of synaptic loss in Alzheimer's disease with [18F]UCB-H positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;47(2):390–402. doi: 10.1007/s00259-019-04461-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(4):256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warnier C, Lemaire C, Becker G, Zaragoza G, Giacomelli F, Aerts J, et al. Enabling efficient positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A) with a robust and one-step radiosynthesis of a highly potent (18)F-labeled ligand ([(18)F]UCB-H) J Med Chem. 2016;59(19):8955–8966. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goutal S, Langer O, Auvity S, Andrieux K, Coulon C, Caillé F, et al. Intravenous infusion for the controlled exposure to the dual ABCB1 and ABCG2 inhibitor elacridar in nonhuman primates. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2018;8(3):536–542. doi: 10.1007/s13346-017-0472-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Camp N, Balbastre Y, Herard AS, Lavisse S, Tauber C, Wimberley C, et al. Assessment of simplified methods for quantification of [(18)F]-DPA-714 using 3D whole-brain TSPO immunohistochemistry in a non-human primate. J Cerebral Blood Flow Metab. 2020;40(5):1103–1116. doi: 10.1177/0271678X19859034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tournier N, Cisternino S, Peyronneau MA, Goutal S, Dolle F, Scherrmann JM, et al. Discrepancies in the P-glycoprotein-mediated transport of (18)F-MPPF: a pharmacokinetic study in mice and non-human primates. Pharm Res. 2012;29(9):2468–2476. doi: 10.1007/s11095-012-0776-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ballanger B, Tremblay L, Sgambato-Faure V, Beaudoin-Gobert M, Lavenne F, Le Bars D, et al. A multi-atlas based method for automated anatomical Macaca fascicularis brain MRI segmentation and PET kinetic extraction. Neuroimage. 2013;77:26–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slifstein M, Laruelle M. Models and methods for derivation of in vivo neuroreceptor parameters with PET and SPECT reversible radiotracers. Nucl Med Biol. 2001;28(5):595–608. doi: 10.1016/S0969-8051(01)00214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wolf AP, Dewey SL, Schlyer DJ, et al. Graphical analysis of reversible radioligand binding from time-activity measurements applied to [N-11C-methyl]-(-)-cocaine PET studies in human subjects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10(5):740–747. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicolas JM, Hannestad J, Holden D, Kervyn S, Nabulsi N, Tytgat D, et al. Brivaracetam, a selective high-affinity synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) ligand with preclinical evidence of high brain permeability and fast onset of action. Epilepsia. 2016;57(2):201–209. doi: 10.1111/epi.13267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finnema SJ, Nabulsi NB, Mercier J, Lin SF, Chen MK, Matuskey D, et al. Kinetic evaluation and test-retest reproducibility of [(11)C]UCB-J, a novel radioligand for positron emission tomography imaging of synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A in humans. J Cerebral Blood Flow Metab. 2017:271678x17724947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Mansur A, Rabiner EA, Comley RA, Lewis Y, Middleton LT, Huiban M, et al. Characterization of 3 PET tracers for quantification of mitochondrial and synaptic function in healthy human brain: (18)F-BCPP-EF, (11)C-SA-4503, and (11)C-UCB-J. J Nucl Med. 2020;61(1):96–103. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.119.228080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li S, Cai Z, Wu X, Holden D, Pracitto R, Kapinos M, et al. Synthesis and in vivo evaluation of a novel PET radiotracer for imaging of synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A (SV2A) in nonhuman primates. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2019;10(3):1544–1554. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nabulsi NB, Mercier J, Holden D, Carré S, Najafzadeh S, Vandergeten M-C, et al. Synthesis and preclinical evaluation of 11C-UCB-J as a PET tracer for imaging the synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A in the brain. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(5):777–784. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.168179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Estrada S, Lubberink M, Thibblin A, Sprycha M, Buchanan T, Mestdagh N, et al. [(11)C]UCB-A, a novel PET tracer for synaptic vesicle protein 2A. Nucl Med Biol. 2016;43(6):325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel S, Knight A, Krause S, Teceno T, Tresse C, Li S, et al. Preclinical in vitro and in vivo characterization of synaptic vesicle 2A-targeting compounds amenable to F-18 labeling as potential PET radioligands for imaging of synapse integrity. Mol Imaging Biol. 2020;22(4):832–841. doi: 10.1007/s11307-019-01428-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen MK, Mecca AP, Naganawa M, Finnema SJ, Toyonaga T, Lin SF, et al. Assessing synaptic density in alzheimer disease with synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2A positron emission tomographic imaging. JAMA Neurol. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Mecca AP, Chen MK, O'Dell RS, Naganawa M, Toyonaga T, Godek TA, et al. In vivo measurement of widespread synaptic loss in Alzheimer's disease with SV2A PET. Alzheimer's Dementia. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Serrano ME, Bahri MA, Becker G, Seret A, Germonpré C, Lemaire C, et al. Exploring with [(18)F]UCB-H the in vivo Variations in SV2A Expression through the Kainic Acid Rat Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Mol Imaging Biol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Additional data on experimental design and individual measures.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.