Abstract

Blockade of programmed death-1 (PD-1) reinvigorates exhausted CD8+ T cells, resulting in tumor regression in cancer patients. Recently, reinvigoration of exhausted CD8+ T cells following PD-1 blockade was shown to be CD28-dependent in mouse models. Herein, we examined the role of CD28 in anti-PD-1 antibody-induced human T cell reinvigoration using tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells (CD8+ TILs) obtained from non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Single-cell analysis demonstrated a distinct expression pattern of CD28 between mouse and human CD8+ TILs. Furthermore, we found that human CD28+CD8+ but not CD28–CD8+ TILs responded to PD-1 blockade irrespective of B7/CD28 blockade, indicating that CD28 costimulation in human CD8+ TILs is dispensable for PD-1 blockade-induced reinvigoration and that loss of CD28 expression serves as a marker of anti-PD-1 antibody-unresponsive CD8+ TILs. Transcriptionally and phenotypically, PD-1 blockade-unresponsive human CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs exhibited characteristics of terminally exhausted CD8+ T cells with low TCF1 expression. Notably, CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs had preserved machinery to respond to IL-15, and IL-15 treatment enhanced the proliferation of CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs as well as CD28+PD-1+CD8+ TILs. Taken together, these results show that loss of CD28 expression is a marker of PD-1 blockade-unresponsive human CD8+ TILs with a TCF1– signature and provide mechanistic insights into combining IL-15 with anti-PD-1 antibodies.

Keywords: anti-PD-1, T cells, TCF1, CD28, IL-15

Subject terms: Tumour immunology, Immunotherapy

Introduction

Antibodies that block the programmed cell death-1 (PD-1)/programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) axis have been approved for treating several types of cancers due to their antitumor efficacy.1 However, clinical responses following anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment are heterogeneous, and a relatively small proportion of patients benefit from this treatment.2 To overcome treatment resistance, a number of clinical trials have been conducted on combination treatment with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy and blocking antibodies for other immune checkpoint receptors, agonistic antibodies for costimulatory molecules, chemotherapeutic agents, target agents, and cytokines.3 However, the biological basis of such combinations has not been able to keep up with clinical trials. Therefore, the key components of resistance to such anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies need to be identified for a more rational design of trials of combination treatments.

CD8+ T cells are the major effectors in PD-1 blockade-induced antitumor responses, and reinvigoration of exhausted CD8+ T cells is one of the main determinants of responsiveness to PD-1 blockade.4–6 Studies of exhausted CD8+ T cells have been performed extensively in mouse chronic viral infection and tumor models, showing that exhausted CD8+ T cells are not a homogeneous population but rather phenotypically and functionally heterogeneous. The cells can be divided into “early exhausted”, which are defined as PD-1int, EomesloTbethi, TCF1+, or CXCR5+, and “terminally exhausted” CD8+ T cells, which are defined as PD-1hi, EomeshiTbetlo, or TCF1–.7–14 The early exhausted CD8+ T cells exhibit progenitor-like function and respond to PD-1 blockade, whereas terminally exhausted CD8+ T cells do not respond.7–14

Expression of costimulatory receptors in CD8+ T cells is also an important factor for responsiveness to PD-1 blockade.15,16 Reinvigoration of exhausted CD8+ T cells after PD-1 blockade has been shown to be CD28-dependent in mouse chronic infection and tumor models. Conditional gene deletion studies confirmed that the presence or absence of CD28 determines CD8+ T cell proliferation after PD-1 blockade; CD28-CD8+ T cells responded poorly to PD-1 blockade, whereas CD28+CD8+ T cells were reinvigorated.16

To extend the findings from mouse models and gain insights into the heterogeneous response of CD8+ TILs to PD-1 blockade in cancer patients, we analyzed CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs from patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). We found that CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs respond poorly to PD-1 blockade compared with their CD28+ counterparts. Unlike mouse CD28, human CD28 signaling was dispensable for the PD-1 blockade-induced proliferative response, and human CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs showed features of terminal exhaustion along with low TCF1 expression. Further investigation revealed that IL-15 reinvigorates PD-1 blockade-unresponsive CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs. Our study demonstrates loss of CD28 expression as a marker of unresponsiveness to PD-1 blockade in human CD8+ TILs and provides mechanistic insights into combining IL-15 with anti-PD-1 therapy for reinvigoration of PD-1-unresponsive CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs.

Results

Single-cell analysis of CD8+ TILs reveals a different pattern of CD28 expression between humans and mice

Publicly available single-cell RNA (scRNA) sequencing datasets for CD8+ T cells isolated from human NSCLC tissues17 and a mouse tumor model18 were used to compare the expression pattern of CD28 in human and mouse CD8+ TILs. Dimensional reduction analysis (t-SNE) revealed several clusters with distinct transcriptional profiles (Fig. 1a–d). In mice, Cd28 tended to be more highly expressed in exhausted CD8+ TILs (C2 and C4; Fig. 1e) and coexpressed with Havcr2 (Tim-3), a marker of terminal T cell exhaustion, but exhibited reciprocal expression with Tcf7 (Tcf1; Fig. 1g). In humans, CD28 was more highly expressed in pre-exhaustion or naïve-like CD8+ TILs (C2 and C5; Fig. 1f) and exhibited coexpression with TCF7 (TCF1) but low coexpression with HAVCR2 (TIM-3; Fig. 1h). We further analyzed CD28 expression in mouse and human CD8+ TILs by flow cytometry. In MC38-OVA mouse tumors, CD28 was expressed at a similar level between Tcf1– and Tcf1+ PD-1+CD8+ TILs (Fig. 1i). Moreover, CD28 expression was significantly higher in Tcf1–PD-1+CD8+ TILs than in their Tcf1+ counterparts in mouse Lewis lung tumors (Supplementary Fig. S1). In contrast, in human NSCLC, CD28 expression was significantly higher in TCF1+PD-1+CD8+ TILs than in their TCF1– counterparts (Fig. 1j). Thus, single-cell analysis of mouse and human tumors revealed a distinct expression pattern of CD28 that indicates the need for research specific to human TILs regarding the role of CD28 in PD-1-mediated T cell reinvigoration.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of CD28 expression patterns between mouse and human CD8+ TILs. a t-SNE projection of public scRNA-seq profiles of mouse CD8+ TILs (n = 540) from T3 tumors. The data were obtained from Gubin et al.18 The cells are colored based on four clusters defined by k-means clustering. b Heatmap of expression values with a list of representative DEGs in each cluster. c t-SNE projection of public scRNA-seq profiles of human CD8+ TILs from NSCLC patients. The data were obtained from Guo et al.17 The cells are colored based on five clusters defined by k-means clustering. d Heatmap of expression values of a list of representative DEGs in each cluster. Violin plots of the log expression level of Cd28 in mouse CD8+ TILs (e) and CD28 in human CD8+ TILs (f). Expression levels of Cd28, Tcf7, Pdcd1, and Havcr2 among mouse CD8+ TILs (g) and CD28, TCF7, PDCD1, and HAVCR2 among human CD8+ TILs (h) illustrated on t-SNE plots. i Expression of CD28 in mouse Tcf1– and Tcf1+ PD-1+CD8+ TILs. Mouse TILs were isolated 14 days after subcutaneous injection of MC38-OVA cells for flow cytometry analysis (n = 6). j Expression of CD28 in human TCF1– and TCF1+ PD-1+CD8+ TILs that were isolated from tumors obtained from NSCLC patients (n = 30). Paired t-test (i, j). ns, not significant, ****P < 0.0001

Human CD28–CD8+ TILs respond poorly to PD-1 blockade but in a CD28-independent manner

To further examine the characteristics of human CD28–CD8+ TILs compared with CD28+CD8+ TILs, we analyzed TILs from human NSCLC tissues. Most of the CD28– and CD28+CD8+ TILs expressed PD-1, and the frequency of PD-1+ cells was similar between the two populations (Fig. 2a). Tumor-associated antigen-specific (MAGE-A1278-286) cells were detected in both CD28– and CD28+ CD8+ TIL populations with no significant difference (Fig. 2b). We stimulated TILs with anti-CD3 antibodies in the presence of anti-PD-1 blocking antibodies and analyzed the expression of Ki-67, a marker of cell cycle entry, in the CD28– and CD28+ CD8+ T cell populations. The frequency of Ki-67+ cells significantly increased among CD28+CD8+ TILs but did not increase among CD28–CD8+ TILs (Fig. 2c). We confirmed this result with sorted CD28– and CD28+ CD8+ TILs (Fig. 2d). The frequency of Ki-67+ cells significantly increased among sorted CD28+CD8+ TILs but did not increase among sorted CD28–CD8+ TILs, and the stimulation index (Ki-67+ frequency with anti-PD-1 antibody/Ki-67+ frequency with isotype control) was significantly higher in CD28+CD8+ TILs than in CD28–CD8+ TILs (Fig. 2e, f). In proliferation assays with CellTrace Violet (CTV) dilution, anti-PD-1 antibodies significantly increased the proliferation of CD28+CD8+ TILs but failed to increase the proliferation of CD28–CD8+ TILs, and the stimulation index (mitotic index with anti-PD-1 antibody/mitotic index with isotype control) was significantly higher in CD28+CD8+ TILs than in CD28–CD8+ TILs (Fig. 2g, h).

Fig. 2.

Human CD28–CD8+ TILs respond poorly to PD-1 blockade. a Percentage of PD-1+ cells among CD28– and CD28+ CD8+ TILs (n = 30). b Percentage of MAGE-A1-specific cells among CD28– and CD28+ CD8+ TILs (n = 6). c Frequency of Ki-67+ cells among gated CD28– and CD28+ CD8+ TILs after 72 h of anti-CD3 antibody stimulation in the presence of anti-PD-1 or isotype antibodies (n = 30). d Representative flow cytometry plot of CD28 expression before and after sorting. Representative flow cytometry plots of Ki-67 expression (e), the percentage of Ki-67+ cells, and the stimulation index (f) of sorted CD28– and CD28+ CD8+ TILs after 72 h of anti-CD3 antibody stimulation in the presence of anti-PD-1 or isotype antibodies (n = 5). Stimulation index = Ki-67+ frequency with anti-PD-1 antibody/Ki-67+ frequency with isotype control. Representative flow cytometry plots of CTV dilution (g), the percentage of proliferated CTVlo cells and the stimulation index (h) of sorted CD28– and CD28+ CD8+ TILs after 72 h of anti-CD3 antibody stimulation in the presence of anti-PD-1 or isotype antibodies (n = 5). Stimulation index = mitotic index (MI) with anti-PD-1 antibody/MI with isotype control. Representative flow cytometry plots of Ki-67 staining among peripheral blood CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ T cells before (day 0) and 7 days after anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibody treatment in patients with NSCLC (i) and the summary data of 12 patients (j). k Cell proliferation measured by CTV dilution after 72 h of anti-CD3 antibody stimulation in the presence of anti-CD80/anti-CD86 or isotype antibodies in sorted CD28+CD8+ TILs (n = 5). l Percentage of proliferated CTVlo cells and the stimulation index of sorted CD28+CD8+ TILs after 72 h of anti-CD3 antibody stimulation in the presence of anti-PD-1 or isotype antibodies and in the presence or absence of anti-CD80/anti-CD86 antibodies (n = 5). Stimulation index = MI with anti-PD-1 antibody/MI with isotype control. m Percentage of Ki-67+ cells among CD28+CD8+ TILs after 72 h of anti-CD3 antibody stimulation in the presence of anti-CD80/CD86 antibodies or CTLA4-Ig (n = 9). n Percentage of Ki-67+ cells and the stimulation index among CD28+CD8+ TILs after 72 h of anti-CD3 antibody stimulation in the presence of anti-PD-1 or isotype antibodies and anti-CD80/CD86 antibodies or CTLA4-Ig (n = 9). o Frequency of Ki-67+ cells among CD8+ TILs after 72 h of anti-CD3 antibody stimulation with or without CD28-Ig (n = 8). p Frequency of Ki-67+ cells and the stimulation index among CD8+ TILs after 72 h of anti-CD3 antibody stimulation with isotype or anti-PD-1 antibodies in the presence or absence of CD28-Ig (n = 8). Stimulation index = Ki-67+ frequency with anti-PD-1 antibody/Ki-67+ frequency with isotype control. Bar graphs represent the mean ± s.d. (a, b). Paired t-test (a–c, f, h, j–p). ns, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

Next, we examined the expression of Ki-67 among CD28– and CD28+CD8+ T cells from anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibody-treated NSCLC patients. Recently, our group and others have shown that the expression of Ki-67 among peripheral blood PD-1+CD8+ T cells after anti-PD-1 therapy peaks 1 week after treatment.6,19 When we analyzed Ki-67 expression in this setting, CD28–PD-1+CD8+ T cells did not have a significant increase in the frequency of Ki-67+ cells, whereas CD28+PD-1+CD8+ T cells exhibited a significant increase (Fig. 2i, j). Taken together, the results indicate that human CD28–CD8+ T cells respond poorly to PD-1 blockade in ex vivo assays and in in vivo anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibody-treated patients.

On the basis of such a difference in responsiveness to PD-1 blockade of CD8+ TILs according to CD28 expression, we tested whether CD28-B7 ligation is required for CD28+CD8+ TILs to respond to PD-1 blockade. Sorted CD28+CD8+ T cells from TILs were labeled with CTV dye and cocultured with CD8-depleted, autologous TILs, and CD14+ monocytes among these cells express B7 molecules, such as CD80 and CD86 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Blocking the CD28-B7 interaction with anti-CD80 and anti-CD86 antibodies significantly decreased the proliferation of CD28+CD8+ TILs (Fig. 2k) but did not abrogate the PD-1 blockade-induced increase in proliferation (Fig. 2l). Next, we used other agents that block the CD28-B7 interaction. CTLA-4-Ig significantly decreased the percentage of Ki-67+ cells among CD28+CD8+ TILs, as did anti-CD80/CD86 antibodies (Fig. 2m). PD-1 blockade significantly increased the percentage of Ki-67+ cells among CD28+CD8+ TILs, regardless of the presence of CTLA-4-Ig (Fig. 2n), corroborating the results from the anti-CD80/CD86 antibody experiment. CD28-Ig also significantly reduced the percentage of Ki-67+ cells among CD8+ TILs (Fig. 2o). In addition, PD-1 blockade significantly increased the percentage of Ki-67+ cells among CD8+ TILs, regardless of the presence of CD28-Ig (Fig. 2p). These findings indicate that CD28 expression by human CD8+ TILs is not required for PD-1 responsiveness but serves as a marker of anti-PD-1 antibody responsiveness.

Human CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs exhibit distinct features of effector-like but severely exhausted T cells

To gain further insight into the different responsiveness to PD-1 blockade of human CD28– and CD28+CD8+ TILs, we performed a transcriptome analysis of the two populations. Because PD-1+CD8+ T cells are targeted by anti-PD-1 antibodies, we compared the characteristics of CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs. The CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs exhibited distinct gene expression profiles with 117 differentially expressed genes (DEGs; adjusted P < 0.01, log2 fold change >1; Fig. 3a). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering revealed that the two populations had distinct gene signatures and were well segregated (Fig. 3b). Fifty-four genes were significantly upregulated and 63 genes were significantly downregulated in CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Table S1). Notably, CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs expressed higher levels of immune checkpoint inhibitory receptors (HAVCR2, LAG3, PDCD1, and CTLA4), lower levels of memory markers (CCR7, LEF1, SELL, and TCF7), and lower levels of CXCR5 than CD28+PD-1+CD8+ TILs (Fig. 3c). These CD28–PD-1+CD8+ cells had higher levels of expression of cytotoxic molecules (GZMA, GZMB, PRF1, and GNLY) but lower levels of expression of TNF and GZMK than their CD28+ counterparts (Fig. 3c). CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs also had features of tissue-resident T cells, high PRDM1, ZNF683, CXCR6, and ITGAE expression, and lower expression of S1PR1 (Fig. 3c). Recently, suggested features of terminal exhaustion, high CD101 and low CD5,20 were also observed in CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs (Fig. 3a). Several of the DEGs between CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs were confirmed at the protein level using flow cytometry, including inhibitory receptors (CTLA-4, TIM-3, and TIGIT), markers of progenitor-like exhausted T cells (TCF-1 and CXCR5), effector molecules (granzyme B and granzyme K), and tissue residency markers (CD103 and CD69; Fig. 3d, e).

Fig. 3.

RNA-seq and flow cytometry analyses of human CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+CD8+ TILs. a CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ T cells were sorted from tumors of four NSCLC patients, and RNA-seq was performed. Volcano plot showing differential gene expression of CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs. Blue points indicate significantly downregulated genes, and red points indicate significantly upregulated genes (adjusted P < 0.01, log2 fold change > 1.0). b Unsupervised clustering of the 117 DEGs between CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs from four patients. c Expression of selected T cell function-associated genes in CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs. Genes with significantly different expression levels are marked by asterisks. Representative flow cytometry plots (d) and summary data (e) of the protein expression of selected markers in CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs (n = 30). Paired t-test (e). ns, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showed that CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs had strong enrichment of PD-1hi TILs21 and LAYN+ clusters in NSCLC17 and HCC22, which are highly exhausted T cell clusters (Fig. 4a). In addition, the signatures derived from the TILs of melanoma patients,23 HIV-specific T cells from HIV progressor patients versus elite controllers,24 and CD39+ versus CD39– HCV-specific T cells25 were significantly enriched in CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, these cells exhibited significant enrichment in signatures of TCF1– and CXCR5– CD8+ T cells from mouse models of chronic infection,9,10 which are the more terminally exhausted CD8+ T cells that do not respond to PD-1 blockade (Fig. 4a). Although CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs were enriched for signatures of terminal exhaustion, these cells also exhibited significant enrichment in the effector T cell-related signature26 and NK cell signature,27 implying their capacity for cytotoxicity (Fig. 4a). However, neither CD28–PD-1+ nor CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs exhibited significant enrichment in the naïve CD8+ T cell signature26 or anergic T cell signature.28 CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs did not exhibit senescent cell signatures29 (Fig. 4b), although CD28–CD8+ T cells are also known to be replicatively senescent in healthy individuals.30

Fig. 4.

CD28–CD8+ TILs show distinct features of effector-like but severely exhausted T cells. a GSEA of public gene sets in the transcriptome of CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs; results are presented as normalized enrichment scores (NESs). *q < 0.05, **q < 0.01, ****q < 0.0001. b GSEA of genes upregulated in naïve CD8+ T cells, anergic T cells, and senescent cells. c The predictive value of the CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TIL signature (expression level of the 54 upregulated genes in CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs estimated by GSVA normalized with the CD8+ T cell fractions obtained by CIBERSORT) for disease progression after anti-PD-1 antibody treatment in melanoma patients. d Survival curves of patients in the Hugo cohort grouped by the expression level of the CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TIL signature. The high and low groups were divided by the cutoff value derived from the ROC curve. Log-rank test (d)

Next, we evaluated whether the gene signature of CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs is associated with poor outcomes after anti-PD-1 treatment. We utilized public RNA-seq data from anti-PD-1 antibody-treated melanoma patients31 and found that a higher CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TIL signature significantly predicted progression after anti-PD-1 treatment (Fig. 4c) and was associated with poorer overall survival (Fig. 4d). Collectively, these results indicate that CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs have features of terminal exhaustion with effector-like function and are associated with a poor response to anti-PD-1 treatment.

Proliferation of CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs is enhanced by IL-15

Next, we extended the flow cytometry analysis of CD28–PD-1+ vs. CD28–PD-1+ CD8+ TILs to cytokine receptors. We focused on receptors for common gamma chain cytokines, including CD25, CD122, CD127, and CD132. We found that CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs expressed higher levels of receptors for IL-15 (CD122 and CD132) and IL-2 (CD25, CD122, and CD132) but lower levels of IL-7 receptor (CD127; Fig. 5a) than CD28+PD-1+CD8+ TILs, although the differences in the expression of CD122 and CD127 were not substantial. The expression pattern of receptors indicated that CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs may respond to IL-15 or IL-2 stimulation, although they poorly respond to PD-1 blockade.

Fig. 5.

CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs have a preserved machinery to respond to IL-15. a Surface expression of CD25 (IL-2Rα), CD127 (IL-7R), CD122 (IL-2Rβ), and CD132 (IL-2Rγ) on CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs (n = 30). Phosphorylation of STAT5 or Akt 1 h after IL-15 stimulation (10 ng/mL) in CD28–PD-1+ (b) and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs (c). Relative increase (the ratio of gMFI in IL-15- and PBS-treated samples) in p-STAT5 (d) and p-Akt (e) in CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs (n = 7). Representative flow cytometry plots of CTV dilution (f), the percentage of proliferated CTVlo cells and the mitotic index (MI) in sorted CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs (g) upon stimulation with IL-15 and/or anti-CD3 antibodies for 6 days (n = 5). Representative flow cytometry plot (h) and the frequency of Ki-67+ cells among CD28– (i) and CD28+ CD8+ TILs (j) after stimulation with anti-CD3 antibodies with or without IL-15 in the presence of anti-PD-1 or isotype antibodies (n = 15). The box plot represents the IQR, with the horizontal line indicating the median. Whiskers extend to a maximum of 1.5 × IQR beyond the box. Bar graphs represent the mean ± s.d. (f, g). Paired t-test (a–e, g, i, j). ns, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

As diverse forms of IL-15 have been developed as immunotherapeutic agents and are currently in clinical trials in combination with anti-PD-1 therapy for the treatment of NSCLC,32 we tested whether CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs can respond to IL-15. The phosphorylation of the downstream IL-15 signaling pathway was examined in CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs and their CD28+ counterparts. STAT5 and Akt were phosphorylated upon IL-15 treatment in CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs (Fig. 5b) as well as in their CD28+ counterparts (Fig. 5c). The phosphorylation levels were similar between the two subsets (Fig. 5d, e). IL-15 did not significantly change the expression of CD28 on CD8+ TILs (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Next, we tested whether CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs proliferate in response to ex vivo IL-15 treatment (Fig. 5f, g). Both CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs proliferated in response to IL-15, and proliferation was further increased when combined with anti-CD3 stimulation. No significant difference in the extent of proliferation between CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs was observed (Fig. 5g). When we evaluated the combined effect of anti-PD-1 therapy and IL-15 in the presence of anti-CD3 therapy, the proliferation of CD28–CD8+ TILs was increased significantly by IL-15 but not by the anti-PD-1 therapy (Fig. 5h, i). For CD28+CD8+ TILs, proliferation was increased significantly by both IL-15 and the anti-PD1 therapy, although the magnitude of increase was higher with IL-15 (Fig. 5h, j). These data indicate that IL-15 with or without anti-PD-1 therapy can robustly enhance the proliferation of TILs by reinvigorating not only CD28+CD8+ TILs but also CD28–CD8+ TILs.

In vivo combination treatment of IL-15/IL-15Rα and anti-PD-1 therapy has enhanced antitumor efficacy

The efficacy of IL-15 in combination with an anti-PD-1 blocking antibody was further tested in vivo using ovalbumin (OVA)-expressing MC38 tumors, a commonly utilized mouse tumor model.33,34 First, we examined the expression of IL-15 receptors on CD8+ TILs from established MC38 tumors 14 days postimplantation. We examined Tcf1–PD-1+ and Tcf1+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs in mice instead of CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs because CD28 expression differs between humans and mice (Fig. 1) and CD28 expression in human PD-1+CD8+ TILs is strongly associated with TCF1 (Fig. 3a, e). However, TCF1 did not directly regulate the expression of CD28 (Supplementary Fig. S4). IL-15 receptors were highly expressed in both Tcf1– and Tcf1+ PD-1+CD8+ TILs (Fig. 6a). IL-15 receptors were also highly expressed in both Tcf1– and Tcf1+ OVA-specific CD8+ TILs (Fig. 6b). Anti-PD-1 antibody or IL-15/IL-15Rα monotherapy significantly delayed tumor growth compared with the control treatment, and combined treatment with an anti-PD-1 antibody and IL-15/IL-15Rα resulted in a significant decrease in tumor size and tumor weight compared with monotherapies (Fig. 6c, d). The therapeutic effects of IL-15/IL-15Rα and the anti-PD-1 antibody were abrogated by CD8+ T cell depletion (Supplementary Fig. S5), indicating that the therapeutic effects of IL-15/IL-15Rα and the anti-PD-1 antibody depend on CD8+ T cells. The number of OVA-specific CD8+ TILs was significantly increased in the combined treatment group (Fig. 6e) in both TCF1+ and TCF1– subpopulations (Fig. 6f, g). Collectively, our data demonstrate that combination treatment with IL-15/IL-15Rα and an anti-PD-1 antibody can enhance antitumor efficacy in a mouse tumor model.

Fig. 6.

Combination of IL-15/IL-15Rα and an anti-PD-1 antibody in an in vivo mouse model. Mouse TILs were isolated from MC38-OVA tumors 14 days after subcutaneous injection for flow cytometry analysis (n = 6). Expression of CD122 and CD132 in Tcf1– and Tcf1+ cells among PD-1+CD8+ TILs (a) and OVA-specific (SIINFEKL) CD8+ TILs (b). Representative flow cytometry plots are shown on the left side of each panel. c Tumor growth curves of MC38-OVA tumors treated with isotype antibody (n = 17), anti-PD-1 antibody (n = 19), IL-15/IL-15Rα (n = 18), and a combination of anti-PD-1 antibody and IL-15/IL-15Rα (n = 17). Treatments were delivered at 14, 17, and 20 days after tumor injection (gray arrowheads). The data are the average of two independent experiments. d Tumor weight of the four treatment groups after sacrifice at day 26. Number of OVA-specific CD8+ TILs (e), Tcf1+ OVA-specific CD8+ TILs (f), and Tcf1– OVA-specific CD8+ TILs (g) per gram of tumor in the four treatment groups. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. (c), and bar graphs represent the mean and s.d. (d–g). Paired t-test (a, b), linear regression (c), Mann–Whitney U test (d–g). ns, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

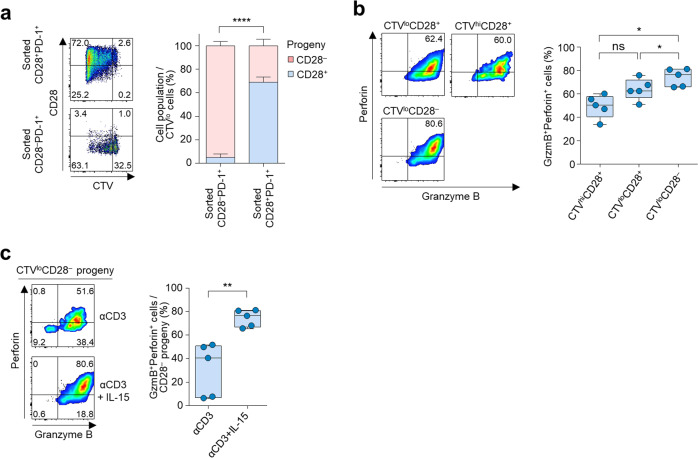

CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs have a progenitor-progeny relationship, and IL-15 increases cytotoxic molecules in CD28– progeny

Recent studies have described progenitor-like and terminally exhausted CD8+ T cells that have distinct expression of TCF1, Eomes, T-bet, and CXCR5.7–12 Due to the distinct pattern of TCF1 expression in CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs, we reasoned that CD28+PD-1+ and CD28–PD-1+ CD8+ TILs may be progenitor-like and terminally exhausted cells, respectively. The hallmark of such progenitor cells is self-renewal and the generation of effector progeny. Therefore, we sorted CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs and cultured them in the presence of anti-CD3 antibody stimulation and IL-15. We found that CD28+PD-1+CD8+ TILs generate not only CD28+ but also CD28– progeny upon proliferation, whereas the CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs only produced CD28– progeny, implying unidirectional CD28+ to CD28– conversion (Fig. 7a).

Fig. 7.

CD28+PD-1+ and CD28–PD-1+ CD8+ TILs show a progenitor-progeny relationship, and IL-15 enhances the cytotoxicity of CD28– progeny. a Percentage of CD28– or CD28+ cells among proliferated cells (CTVlo cells) following stimulation with anti-CD3 antibody and IL-15 for 6 days in sorted CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs (n = 5). b Percentage of granzyme B+ perforin+ cells among CTVhiCD28+, CTVloCD28+, and CTVloCD28– cells (all originating from sorted CD28+PD-1+CD8+ TILs) following stimulation with anti-CD3 antibody and IL-15 for 6 days. c Percentage of granzyme B+ perforin+ cells in CD28– progeny derived from CD28+PD-1+CD8+ TILs after simulation with anti-CD3 antibody or anti-CD3 antibody plus IL-15 for 6 days. Representative flow cytometry plots are shown on the left side of each panel. The box plot represents the IQR, with the horizontal line indicating the median. Whiskers extend to a maximum of 1.5 × IQR beyond the box (b,c). Bar graphs represent the mean and s.d. (a). Paired t-test (a–c). ns, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001

A recent study showed that tumor control is inferior when tumor-specific TCF1– effector cells are inefficiently generated,35 indicating a critical role of the effector functions of TCF1–CD8+ T cells in tumor control. In our study, the CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs expressed higher levels of cytotoxic molecules (Fig. 3c–e) and had more effector CD8+ T cell features than their CD28+ counterparts (Fig. 4a). To test the role of the progeny CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs in tumor control, we sorted Tcf1–PD-1+ and Tcf1+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs obtained from MC38-OVA tumors using Slamf6 and Tim-3 as surrogate surface markers of Tcf1 expression14,36 and adoptively transferred each subset into a new host bearing an MC38-OVA tumor. We confirmed the distinct expression of Tcf1 in Slamf6–Tim-3+ and Slamf6+Tim3– PD-1+CD8+ TILs (Supplementary Fig. S6). We found that tumor growth was significantly delayed by adoptive transfer of Tcf1–(Slamf6–Tim-3+) CD8+ TILs but not by adoptive transfer of Tcf1+(Slamf6+Tim-3+) CD8+ TILs (Supplementary Fig. S7). This result implies that CD28– (or Tcf1–) CD8+ TILs exert immediate effector functions against tumor cells.

In our human data, the CD28– progeny produced from the CD28+PD-1+CD8+ TILs exhibited higher expression of granzyme B and perforin than the CD28+ progeny (Fig. 7b). However, the CD28– progeny exhibited significantly lower expression of granzyme B and perforin when generated in the presence of anti-CD3 antibodies without IL-15 (Fig. 7c). Taken together, the results indicate that the progenitor CD28+PD-1+CD8+ TILs produce CD28– progeny and that IL-15 increases the cytotoxic features of the CD28– progeny.

Discussion

Exhausted CD8+ T cells in chronic viral infection or tumors are not a homogeneous population and exist in different states of dysfunction.7–12 Only a subset of these exhausted CD8+ T cells have a chance for reinvigoration following PD-1 blockade. Although the heterogeneity of exhausted CD8+ T cells has been investigated in humans, no studies have directly addressed the anti-PD-1 antibody responsiveness of different subpopulations of CD8+ T cells infiltrating human tumors. Less is known about how to rescue the anti-PD-1 antibody-unresponsive subsets of CD8+ TILs. In the present study, we utilized human lung tumor tissues and described terminally exhausted CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs with low TCF1 expression that did not respond to anti-PD-1 antibodies but could be rescued by IL-15.

CD28 expressed on T cells has been shown to be the primary target of PD-1-mediated inhibition, and the CD28-B7 interaction is required for the reinvigoration of exhausted CD8+ T cells upon PD-1 blockade.15,16 Data on the CD28 dependency of the effect of PD-1 blockade are based on murine models of chronic viral infection and tumors.16 Although mice and humans share key characteristics of T cell exhaustion, they also differ in certain aspects. In the present study, we found that the pattern of CD28 expression was different between mouse and human CD8+ TILs. We found that human CD28+CD8+ TILs, but not CD28–CD8+ TILs, respond to PD-1 blockade irrespective of the CD28-B7 interaction, which indicates that CD28 is a marker of anti-PD-1 antibody responsiveness rather than a requirement for anti-PD-1 antibody-induced reinvigoration. We used anti-CD80/CD86 antibodies, CTLA-4-Ig, and CD28-Ig to block the CD28-B7 interaction. We could not use anti-CD28 antibodies for blocking because they have agonistic effects. CD80 and CD86 preferably bind to CTLA-4, which could influence the observed outcome, as T cells are regulated by a balance of positive (CD28) and negative (CLTA-4) signals. In our study, CTLA-4 was expressed among CD8+ TILs, although the expression level was weak. However, the proliferation of CD8+ TILs was decreased by blocking agents, including anti-CD80/CD86 antibodies and CTLA-4-Ig. These data indicate that the blocking agents may affect the B7-CD28 interaction rather than the B7-CTLA-4 interaction, resulting in inhibitory effects on T cell proliferation. Therefore, the use of anti-CD80/CD86 antibodies or CTLA-4-Ig may be effective for abrogating CD28 costimulation. Despite a decrease in proliferation after CD28 blocking, the anti-PD-1 antibody-induced increase in proliferation was maintained. This is in contrast to the findings of a previous study showing that blocking CD28 ligands abrogate the antitumor effects of PD-L1-blocking antibodies in mouse tumor models.16 The in vivo results from mouse tumor models should be interpreted carefully since blocking CD28 ligands causes poor priming of T cells and may result in poor tumor control apart from the effect of CD28 on PD-1 blockade. In this regard, our ex vivo experiments using human TILs more precisely dissected the effect of CD28 on PD-1 blockade. Our analyses revealed that PD1 blockade-unresponsive CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs have a terminally exhausted phenotype with low TCF1 expression, which are well-known features of exhausted CD8+ T cells that do not respond to PD-1 blockade.13,14,37

TCF1 is a downstream transcription factor of the Wnt-β catenin pathway. In T cells, TCF1 plays a role in the development and maintenance of stemness.38,39 In addition, TCF1-expressing exhausted CD8+ T cells respond to PD-1 blockade in mouse chronic viral infection and tumor models. In humans, a higher frequency of TCF1 expression in CD8+ TILs has been shown to be associated with superior treatment outcomes after anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients.37 Considering the importance of TCF1 expression for the response to anti-PD-1 treatment, TCF1 may serve as a target to overcome anti-PD-1 resistance. A Gsk-3β inhibitor, TWS119, which can enhance the activity of TCF1, has been tested in generating stem-like memory CD8+ T cells for adoptive T cell therapy.38,40 However, systemic application is limited in cancer patients because intrinsic activation of the Wnt-β catenin pathway in tumor cells can cause immune evasion.41–44 Therefore, rather than directly targeting TCF1, we investigated an alternative to enhance the proliferation of CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs using IL-15. Notably, the CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs had higher expression of IL-15 receptors than their CD28+ counterparts and a preserved downstream signaling pathway to respond to IL-15.

IL-15 is a member of the common gamma chain cytokine family and is well known for its role in maintaining the CD8+ T cell pool via homeostatic proliferation and for its function in increasing the cytotoxicity of NK cells and CD8+ T cells.45,46 Previous studies in mouse chronic viral infection models have reported that antigen-specific CD8+ T cells are not maintained by cytokines such as IL-15 and IL-7.47 However, IL-15 has shown therapeutic efficacy in mouse tumor models.48,49 In addition, diverse forms of IL-15 have been developed as immunotherapeutic agents and are currently in clinical trials in combination with anti-PD-1 antibodies for the treatment of solid tumors.32,50 In the current study, we found that human CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs and their CD28+ counterparts responded well to IL-15 in terms of proliferation. In our in vitro assay system, IL-15-induced proliferation dominated over anti-PD-1 antibody-induced proliferation, although the anti-PD-1 antibody significantly increased the proliferation of CD28+CD8+ TILs. These results could be due to the differences in how CD8+ T cell populations respond to treatments. Anti-PD-1 antibodies reinvigorate tumor antigen-specific PD-1+CD8+ TILs, whereas IL-15 can activate CD8+ TILs regardless of antigen specificity, including bystander T cells, which are abundant in tumor tissues.51–53 As tumor antigen-specific T cells are more important in antitumor immunity than bystander T cells, we believe that anti-PD-1 antibody-induced proliferation is not negligible, although its magnitude was lower than the magnitude of IL-15-induced proliferation. The in vivo combination of IL-15 and an anti-PD-1 antibody significantly delayed tumor growth in a CD8+ T cell-dependent manner and increased tumor-specific CD8+ TIL infiltration.

The CD28+PD-1+ and CD28–PD-1+ CD8+ TILs exhibited a progenitor-progeny relationship reminiscent of the recently suggested hierarchy of exhausted CD8+ T cells.54 CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs exhibit not only a terminally exhausted phenotype but also characteristics of effector cells with higher expression of cytotoxic molecules. We found that the progeny Tcf1–PD-1+CD8+ TILs in mouse tumors exhibited better efficacy in immediate tumor control than progenitor-like Tcf1+PD-1+CD8+ TILs. This implies that the progeny derived from the progenitor exhausted CD8+ T cells may be the population that exhibits cytotoxic effects against the tumor cells. In our study, we found that IL-15 could increase the expression of effector molecules in CD28– progeny, which may contribute to better tumor control in addition to enhanced proliferation of CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs.

In summary, we describe CD28 as a marker of the cellular response to PD-1 blockade in CD8+ TILs that functions in a different manner in mice and humans. Moreover, we found that IL-15 can rescue anti-PD-1 antibody-unresponsive CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs. Our results provide a mechanistic basis for the combination of anti-PD-1 with IL-15 as an option to overcome unresponsiveness to anti-PD-1 therapy.

Materials and methods

Study design

The aim of this study was to investigate PD-1 blockade-unresponsive CD8+ TILs and enhance the function of these cells. We used human CD8+ TILs obtained from treatment-naïve NSCLC patients who underwent surgical resection. Fifty-seven patients with NSCLC who underwent surgical resection of the primary tumor at Samsung Medical Center between December 2017 and December 2018 were included (Supplementary Table S2). An additional cohort of stage IV NSCLC patients who received anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment between April 2018 and August 2018 at Samsung Medical Center was included to evaluate the response of peripheral blood CD8+ T cells (Supplementary Table S3). Peripheral blood was collected on the day of treatment initiation and 1 week after the first dose. The sample size is specified in each figure legend. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Samsung Medical Center (SMC 2010-04-039-052), and all patients provided written informed consent. The reagents and resources used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S4.

Mice

Female C57BL/6 mice aged 6–9 weeks were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and housed at Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) under SPF conditions. All experiments followed protocols approved by the KAIST Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

In vivo tumor model

MC38-OVA cells were generously provided by Sang-Jun Ha. Lewis lung carcinoma cells were purchased from ATCC. The cells were cultured in DMEM (Welgene) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Welgene) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Welgene). A total of 1 × 106 MC38-OVA cells or Lewis lung carcinoma cells were injected subcutaneously into the right flank. Tumors were measured every 3 days starting 11 days postinoculation. Tumor volume (mm3) was calculated using the following formula: Volume = (tumor length) × (tumor width)2/2. Mice were treated with 200 µg anti-PD-1 or isotype-matched control antibody (BioXCell) with or without 1 µg recombinant IL-15/IL-15Rα Complex Protein (Invitrogen) on days 14, 17, and 20. On day 26, the mice were sacrificed for TIL analysis. For CD8+ T cell depletion experiments, the anti-CD8α antibody (BioXCell) was delivered on days 11, 14, 17, and 20.

In vivo adoptive transfer

A total of 1 × 106 MC38-OVA cells were injected subcutaneously, and progenitor or progeny (terminally exhausted) TILs were sorted from the tumors on days 19–21. Cells were resuspended in PBS, and 50,000 cells were transferred via tail vein injection into each mouse, which had been subcutaneously injected with 1 × 106 MC38-OVA cells 2 days before the adoptive transfer. In mice that received both progenitor and progeny cells, 25,000 cells of each cell population were transferred. Tumor size was measured at day 7 and every 3 days afterward.

Sample preparation

Fresh human tumor samples collected immediately after surgery were dissociated into single-cell suspensions using a gentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec) with a Tumor Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Briefly, tumor tissue was cut into small pieces and transferred to a gentle MACS C-tube (Miltenyi Biotec), and 4.7 mL of RPMI 1640 (Welgene) premixed with 200 µL of enzyme H, 100 µL of enzyme R, and 25 µL of enzyme A (Miltenyi Biotec) was added. Next, the C-tubes were placed on a gentleMACS Octo Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec) for 1 h at 37 °C. The cell suspension was passed through a 70 µM strainer and washed once with PBS. The cells were counted and cryopreserved for further use. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from peripheral blood by density gradient centrifugation with lymphocyte separation medium (Corning). Mouse TILs were isolated by mechanical dissociation using a gentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec) and Percoll (GE Healthcare) density gradient centrifugation.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Cells were blocked with TrueStain FcX (BioLegend), and surface staining was performed with the indicated antibodies (Table S4) for 20 min at 4 °C. Dead cells were gated out using the LIVE/DEAD fixable dead cell stain kit (Invitrogen). For intracellular staining, surface-stained cells were fixed and permeabilized with the Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBiosciences) and further stained with the indicated antibodies. TCF1 was stained with anti-TCF1 antibody (Cell Signaling) followed by secondary anti-rabbit antibody. For detection of phosphorylated molecules, surface-stained cells were fixed with IC fixation buffer (eBioscience) and permeabilized with methanol, followed by staining with phospho-specific antibodies. MAGE-A1-specific CD8+ T cells were identified using APC-conjugated HLA-A*0201 dextramers (MAGE-A1278–286; KVLEYVIKV; Immudex). For mouse TILs, OVA-specific CD8+ T cells were detected using APC-conjugated H-2 Kb dextramers (OVA257–264; SIINFEKL; Immudex). Cells were acquired on an LSRII cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo (TreeStar).

For sorting, human CD8+ TILs were enriched from tumor single-cell suspensions using CD8+ MACS positive selection (Miltenyi Biotec). The negative fraction was irradiated (3000 rad) and used as feeder cells. The sorted CD8+ TILs were further sorted on a FACS Aria II (BD Biosciences) cytometer to obtain CD28+ and CD28– or CD28+PD-1+ and CD28–PD-1+ CD8+ TILs with purity >95%. For mouse TIL sorting, mouse CD8 + TILs were enriched from tumor single-cell suspensions using CD8+ MACS positive selection (Miltenyi Biotec) followed by sorting of live CD45+CD8+PD-1+CD44+Slamf6+Tim-3– or live CD45+CD8+PD-1+CD44+Slamf6–Tim-3+ cells on a FACS Aria II (BD Biosciences) cytometer.

In vitro proliferation assays

The reinvigoration capacity after PD-1 blockade was assessed as described previously.55 TILs were labeled with CellTrace Violet (Invitrogen) and stimulated with soluble anti-CD3 antibody (1 ng/mL; Miltenyi Biotech) in the presence of 10 µg/mL anti-PD-1 or matched isotype control antibody (BioLegend). For combination treatment, 1 ng/mL recombinant human IL-15 (PeproTech) was added. For B7-blocking experiments, anti-CD80 and anti-CD86 antibodies (10 µg/mL; BD Biosciences), recombinant CTLA-4-Fc chimera (5 µg/mL; R&D Systems), or recombinant CD28-Fc chimera (10 µg/mL; R&D Systems) was added. For the experiments with sorted CD8+ TIL populations, irradiated autologous feeder cells derived from the rest of the tumor single-cell suspension were used. After 72 h of stimulation, cells were harvested and stained for flow cytometric analysis. The mitotic index was estimated by dividing the number of cell divisions by the absolute number of precursor cells, which was calculated based on the number of cells in each mitotic division. The stimulation index was defined as the ratio of the mitotic indices (or frequency of Ki-67+ cells) of anti-PD-1 antibody-treated samples and isotype control antibody-treated samples. All experiments were performed in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

siRNA transfection

Sorted CD8+ T cells were transfected with TCF7 siRNA or control siRNA (Invitrogen) using a Neon transfection electroporator (Invitrogen) according to the supplier’s protocol. The expression of TCF1 and CD28 was analyzed 72 h after transfection using flow cytometry.

RNA sequencing and analysis

RNA sequencing was performed on sorted CD28–PD-1+ and CD28+PD-1+ CD8+ TILs. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA quality was assessed by an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer using a RNA 6000 Nano Chip (Agilent Technologies), and RNA was quantified using an ND-2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Extracted RNAs were processed using the QuantSeq 3′ mRNA-Seq Library Prep Kit (Lexogen). Briefly, 500 ng of total RNA was prepared, and an oligo-dT primer containing an Illumina-compatible sequence at its 5′ end was hybridized to the RNA, and reverse transcription was performed. After degradation of the RNA template, second strand synthesis was initiated by a random primer containing an Illumina-compatible linker sequence at its 5′ end. The double-stranded library was purified by magnetic beads. The library was amplified to add the complete adapter sequences required for cluster generation. The finished library was purified from PCR components. High-throughput sequencing was performed as single-end 75 sequencing using NextSeq 500 (Illumina). Reads were aligned on a human reference sequence (hg19) using Bowtie2.56 The number of mapped reads on each gene was calculated using Bedtools.57 Gene counts were normalized by library size, and the differential expression of genes was analyzed using DESeq2 (v. 1.24.0). DEGs were determined according to cutoffs of an adjusted P value < 0.01 and a log2 fold change > 1. GSEA was performed using Broad Institute software (http://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp).

RNA-seq data and patient information for anti-PD-1 antibody-treated patients were obtained from a previously published study (GSE78220).31 Only patients who had both pretreatment RNA-seq and clinical outcome data were included in the analysis. Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) was performed using the GSVA R package (v.1.32.0).58 The enrichment score for the CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TIL signature (significantly upregulated genes in CD28–PD-1+CD8+ TILs) was calculated by GSVA for each tumor sample and then normalized by multiplying the value by the CD8+ T cell fractions estimated by CIBERSORT.17,59 The predictive power of the enrichment score for cancer progression was evaluated by a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The optimal cutoff point for the enrichment score was determined by the maximized Youden index on the ROC curve. The patient group was dichotomized by the cutoff point as “high” and “low”, and these groups were compared for overall survival.

Single-cell RNA sequencing data analysis

The scRNA-seq data for mouse T3 tumors and NSCLC patients were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus datasets GSE11935218 and GSE99254.17 For human data (GSE99254), the analysis was restricted to the cells labeled “Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T Cells” (n = 1956). For mouse data (GSE119352), CD8+ T cells were selected based on the normalized expression levels of Cd3e and Cd8a (n = 540). Downstream analyses were performed in R using the Seurat package (v.3.0).60 Clusters were annotated by their differential gene expression signature.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 and R software (v.3.5.1). For continuous variables, paired or unpaired t tests, Mann–Whitney tests, or Wilcoxon signed rank tests were performed as specified in the figure legends. Pearson correlation analysis was used to evaluate correlations between parameters. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and comparisons were made using the log-rank test. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

KHK, HKK, M-JA, and E-CS contributed to the conceptual design of the study. HKK, M-JA, JK, and BMK collected human samples. KHK, HL, and HK processed patients’ samples. KHK and E-CS designed the experiments. KHK, H-DK, CGK, HL, JWH, SJC were involved in data acquisition. KHK, HKK, H-DK, CGK, HL, JWH, SJC, S-HP, M-JA, and E-CS were involved in data analysis and interpretation. KHK performed statistical analysis. KHK, HKK, M-JA, and E-CS drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Kyung Hwan Kim, Hong Kwan Kim

These authors jointly supervised this work: Myung-Ju Ahn, Eui-Cheol Shin

Contributor Information

Myung-Ju Ahn, Email: silkahn@skku.edu.

Eui-Cheol Shin, Email: ecshin@kaist.ac.kr.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41423-020-0427-6) contains supplementary material.

References

- 1.Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science. 2018;359:1350–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, Ribas A. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;168:707–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang J, et al. Trial watch: the clinical trial landscape for PD1/PDL1 immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018;17:854–855. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tumeh PC, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014;515:568–571. doi: 10.1038/nature13954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang AC, et al. T-cell invigoration to tumour burden ratio associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature. 2017;545:60–65. doi: 10.1038/nature22079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim KH, et al. The first-week proliferative response of peripheral blood PD-1(+)CD8(+) T cells predicts the response to anti-PD-1 therapy in solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:2144–2154. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackburn SD, Shin H, Freeman GJ, Wherry EJ. Selective expansion of a subset of exhausted CD8 T cells by alphaPD-L1 blockade. Proc. Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15016–15021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801497105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paley MA, et al. Progenitor and terminal subsets of CD8+ T cells cooperate to contain chronic viral infection. Science. 2012;338:1220–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.1229620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Utzschneider DT, et al. T Cell Factor 1-expressing memory-like CD8(+) T cells sustain the immune response to chronic viral infections. Immunity. 2016;45:415–427. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Im SJ, et al. Defining CD8+ T cells that provide the proliferative burst after PD-1 therapy. Nature. 2016;537:417–421. doi: 10.1038/nature19330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He R, et al. Follicular CXCR5- expressing CD8(+) T cells curtail chronic viral infection. Nature. 2016;537:412–428. doi: 10.1038/nature19317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu T, et al. The TCF1-Bcl6 axis counteracts type I interferon to repress exhaustion and maintain T cell stemness. Sci Immunol. 2016;23:eaai8593. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aai8593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siddiqui I, et al. Intratumoral Tcf1(+)PD-1(+)CD8(+) T cells with stem-like properties promote tumor control in response to vaccination and checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Immunity. 2019;50:195–211. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller BC, et al. Subsets of exhausted CD8(+) T cells differentially mediate tumor control and respond to checkpoint blockade. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:326–336. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0312-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hui E, et al. T cell costimulatory receptor CD28 is a primary target for PD-1-mediated inhibition. Science. 2017;355:1428–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamphorst AO, et al. Rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells by PD-1-targeted therapies is CD28-dependent. Science. 2017;355:1423–1427. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf0683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo X, et al. Global characterization of T cells in non-small-cell lung cancer by single-cell sequencing. Nat Med. 2018;24:978–985. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gubin MM, et al. High-dimensional analysis delineates myeloid and lymphoid compartment remodeling during successful immune-checkpoint cancer therapy. Cell. 2018;175:1014–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang AC, et al. A single dose of neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade predicts clinical outcomes in resectable melanoma. Nat Med. 2019;25:454–461. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0357-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Philip M, et al. Chromatin states define tumour-specific T cell dysfunction and reprogramming. Nature. 2017;545:452–456. doi: 10.1038/nature22367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thommen DS, et al. A transcriptionally and functionally distinct PD-1(+) CD8(+) T cell pool with predictive potential in non-small-cell lung cancer treated with PD-1 blockade. Nat Med. 2018;24:994–1004. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0057-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng C, et al. Landscape of infiltrating T cells in liver cancer revealed by single-cell sequencing. Cell. 2017;169:1342–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tirosh I, et al. Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science. 2016;352:189–196. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quigley M, et al. Transcriptional analysis of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells shows that PD-1 inhibits T cell function by upregulating BATF. Nat Med. 2010;16:1147–1151. doi: 10.1038/nm.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta PK, et al. CD39 expression identifies terminally exhausted CD8+ T cells. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005177. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wherry EJ, et al. Molecular signature of CD8+ T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity. 2007;27:670–684. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bezman NA, et al. Molecular definition of the identity and activation of natural killer cells. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1000–1009. doi: 10.1038/ni.2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Safford M, et al. Egr-2 and Egr-3 are negative regulators of T cell activation. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:472–480. doi: 10.1038/ni1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fridman AL, Tainsky MA. Critical pathways in cellular senescence and immortalization revealed by gene expression profiling. Oncogene. 2008;27:5975–5987. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weng NP, Akbar AN, Goronzy J. CD28(-) T cells: their role in the age-associated decline of immune function. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hugo W, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic features of response to anti-PD-1 therapy in metastatic melanoma. Cell. 2016;165:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wrangle JM, et al. ALT-803, an IL-15 superagonist, in combination with nivolumab in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: a non-randomised, open-label, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:694–704. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30148-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurtulus S, et al. Checkpoint blockade immunotherapy induces dynamic changes in PD-1(-)CD8(+) tumor-infiltrating T cells. Immunity. 2019;50:181–194. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanchez-Paulete AR, et al. Cancer Immunotherapy with immunomodulatory anti-CD137 and anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies requires BATF3-dependent dendritic cells. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:71–79. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snell LM, et al. CD8(+) T cell priming in established chronic viral infection preferentially directs differentiation of memory-like cells for sustained immunity. Immunity. 2018;49:678–694. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Z, et al. TCF-1-centered transcriptional network drives an effector versus exhausted CD8 T cell-fate decision. Immunity. 2019;51:840–855. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sade-Feldman M, et al. Defining T cell states associated with response to checkpoint immunotherapy in melanoma. Cell. 2018;175:998–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gattinoni L, et al. Wnt signaling arrests effector T cell differentiation and generates CD8+ memory stem cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:808–813. doi: 10.1038/nm.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeannet G, et al. Essential role of the Wnt pathway effector Tcf-1 for the establishment of functional CD8 T cell memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9777–9782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914127107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sabatino M, et al. Generation of clinical-grade CD19-specific CAR-modified CD8+ memory stem cells for the treatment of human B-cell malignancies. Blood. 2016;128:519–528. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-11-683847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhan T, Rindtorff N, Boutros M. Wnt signaling in cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36:1461–1473. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruiz de Galarreta M., et al. beta-catenin activation promotes immune escape and resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2019; 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Nsengimana J, et al. beta-Catenin-mediated immune evasion pathway frequently operates in primary cutaneous melanomas. J Clin Investig. 2018;128:2048–2063. doi: 10.1172/JCI95351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xue J, et al. Intrinsic beta-catenin signaling suppresses CD8(+) T-cell infiltration in colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;115:108921. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jabri B, Abadie V. IL-15 functions as a danger signal to regulate tissue-resident T cells and tissue destruction. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:771–783. doi: 10.1038/nri3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waldmann TA. The biology of interleukin-2 and interleukin-15: implications for cancer therapy and vaccine design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:595–601. doi: 10.1038/nri1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shin H, Blackburn SD, Blattman JN, Wherry EJ. Viral antigen and extensive division maintain virus-specific CD8 T cells during chronic infection. J Exp Med. 2007;204:941–949. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu RB, et al. IL-15 in tumor microenvironment causes rejection of large established tumors by T cells in a noncognate T cell receptor-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:8158–8163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301022110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mathios D, et al. Therapeutic administration of IL-15 superagonist complex ALT-803 leads to long-term survival and durable antitumor immune response in a murine glioblastoma model. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:187–194. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Conlon K, et al. Abstract CT082: phase (Ph) I/Ib study of NIZ985 with and without spartalizumab (PDR001) in patients (pts) with metastatic/unresectable solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2019;79:CT082. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simoni Y, et al. Bystander CD8(+) T cells are abundant and phenotypically distinct in human tumour infiltrates. Nature. 2018;557:575–579. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duhen T, et al. Co-expression of CD39 and CD103 identifies tumor-reactive CD8 T cells in human solid tumors. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2724. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05072-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scheper W, et al. Low and variable tumor reactivity of the intratumoral TCR repertoire in human cancers. Nat Med. 2019;25:89–94. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McLane LM, Abdel-Hakeem MS, Wherry EJ. CD8 T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection and cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2019;37:457–495. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-041015-055318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim HD, et al. Association between expression level of PD1 by tumor-infiltrating CD8(+) T cells and features of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1936–1950. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:841–842. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hanzelmann S, Castelo R, Guinney J. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform. 2013;14:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Newman AM, et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. 2015;12:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Satija R, Farrell JA, Gennert D, Schier AF, Regev A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:495–502. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.