Abstract

Myeloid cells in tumor tissues constitute a dynamic immune population characterized by a non-uniform phenotype and diverse functional activities. Both tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which are more abundantly represented, and tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) are known to sustain tumor cell growth and invasion, support neoangiogenesis and suppress anticancer adaptive immune responses. In recent decades, several therapeutic approaches have been implemented in preclinical cancer models to neutralize the tumor-promoting roles of both TAMs and TANs. Some of the most successful strategies have now reached the clinic and are being investigated in clinical trials. In this review, we provide an overview of the recent literature on the ever-growing complexity of the biology of TAMs and TANs and the development of the most promising approaches to target these populations therapeutically in cancer patients.

Keywords: tumor-associated macrophages, tumor microenvironment, macrophage targeting

Subject terms: Cancer microenvironment, Innate immune cells

Introduction

The presence and functional activities of myeloid cells in tumors are raising increasing interest since these cells are relevant modulators of anticancer therapies and potential targets of specific treatments.

In recent decades, our knowledge on the functional role of myeloid cells (macrophages and neutrophils) and their reciprocal interactions with tumor cells has remarkably increased. The amounts and types of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes, commonly referred to as the immune landscape, have been robustly shown to have prognostic value based on the evidence showing that specific cell types are associated with distinct disease outcomes in patients. For instance, the density of CD8+ T cells usually positively correlates with survival and therapeutic response. In the case of myeloid cells, instead, the general observation is that their density is negatively associated with prognosis.1–6

In a few studies, however, specific subsets of myeloid cells were correlated with better clinical responses and longer survival. These findings underline the remarkable heterogeneity of macrophages/neutrophils in tumors. This characteristic, referred to as “myeloid plasticity”, is dictated by specific responses to different local stimuli, which induce distinct genetic programs.7,8

Recent fate mapping and RNA-sequencing experiments have produced a picture of the diversity of tumor-associated myeloid cells that is much more complex than that conceived just a few years ago. If the earlier simplified scheme was that tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) appear to be distinct from M1-polarized macrophages and closer—but not identical—to M2 (M2-like) macrophages, it is now evident that TAM heterogeneity is much wider and dictated by the tumor microenvironment (TME) and stage of disease.3–5,9

Mirroring the macrophage nomenclature, tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) have been dissected into N1 and N2 subtypes, defining cells with protumor and antitumor activities, respectively.10–12 As already mentioned, this nomenclature represents an oversimplification of neutrophil heterogeneity in cancer.

Attention has also been directed to the origin of macrophages in tumor tissues. Whereas previous knowledge exclusively attributed the ontogeny of TAMs to bone marrow-derived monocytes, recent evidence shows that tissue-resident macrophages also contribute to the biology of TAMs rather than functioning as bystanders in carcinogenesis.

This review summarizes the state-of-the-art knowledge on myeloid cells in tumors, particularly macrophages and neutrophils. The impacts of these populations on cancer progression and treatment efficacy are discussed. Finally, we provide an overview of the available therapeutic strategies targeting cancer-associated myeloid cells, specifically those designed to limit the immunosuppressive and tumor-promoting functions of these populations.

Origin and phenotype of myeloid cells in tumors

Tumor-associated macrophages

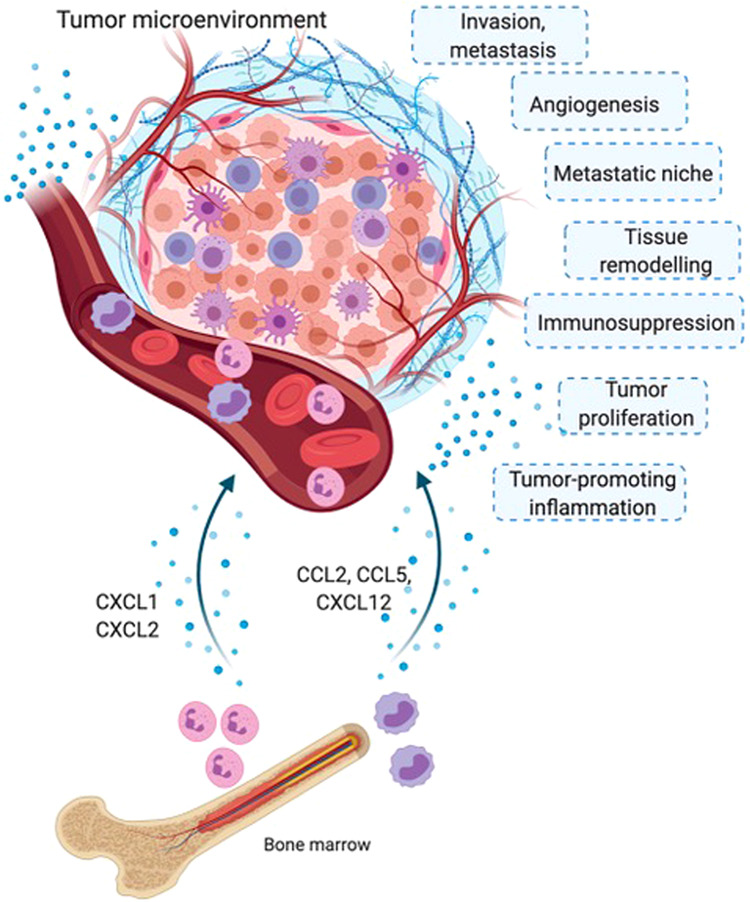

Overall, the vast majority of TAMs are derived from circulating monocytes that are continuously recruited to the tumor site. Cancer cells and TAMs, as well as other cells in the TME, such as fibroblasts, are major sources of the chemoattractants mediating the recruitment of monocytes3–5 (Fig. 1). Nonetheless, the profile of tissue-resident macrophages is also affected when nearby cells undergo neoplastic transformation and can contribute to the TAM population. Virtually all tissues harbor resident macrophages, which play important defensive roles as innate immune sentinels and trophic functions involved in the maintenance of tissue integrity and healing upon injury. It is known that resident macrophages have an origin during embryogenesis distinct from that of hematopoietic precursors in the yolk sac or fetal liver, and they self-renew by local proliferation throughout adulthood.13 Notwithstanding, resident macrophages can be repopulated by circulating monocytes in specific tissues and under specific circumstances.14 The frequency of tissue-resident macrophages among TAMs and, more importantly, their functional role are still open issues.15,16 Franklin et al. demonstrated that the numbers of resident macrophages progressively decreased over time in murine models of breast cancer, while those of monocyte-derived TAMs concomitantly increased. Consistently, depletion of resident macrophages did not influence tumor growth, whereas depletion of circulating monocytes resulted in a better outcome.17 In contrast, in murine pancreatic cancer models, resident macrophages were found to expand during tumor progression and acquire a profibrotic transcriptional profile, favoring the desmoplastic reaction typical of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Loss of resident macrophages but not monocyte-derived macrophages significantly reduced tumor growth.18 In brain tumors, most (but not all) TAMs are derived from resident microglia rather than circulating monocytes, probably because of the presence of the blood-brain barrier.19,20 Other recent studies have highlighted the role of tissue-resident macrophages in tumors. Etzerodt et al. reported that a population of self-renewing CD163+ Tim4+ macrophages residing in the omentum provides a protective niche for ovarian cancer stem cells and has a causative role in their metastatic spread.21

Fig. 1.

Origins of tumor-associated myeloid cells. Tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) and macrophages (TAMs) originate from bone marrow monocytic and neutrophilic precursors, respectively, released into the circulation. Chemokines and other chemoattractants (including CCL2, CCL5, and CXCL12) produced by cellular components of the tumor microenvironment induce the recruitment of myeloid cells to tumor tissue. Once in the microenvironment, TAMs and TANs display several protumor functions, such as sustaining tumor-promoting inflammation, stimulating tumor cell proliferation, inducing T cell immunosuppression, organizing tissue remodeling responses, and stimulating angiogenesis, favoring invasion and metastasis

The tumor microenvironment dictates the number and types of myeloid cells recruited from the circulation via the expression of a wide range of chemoattractants. Bone marrow-derived monocytes are recruited beginning in the early phases of carcinogenesis by chemokines of the CC and CXC families, such as CCL2, CCL5, and CXCL12.22 Once they arrive in the neoplastic environment, monocytes differentiate into mature macrophages, a transition facilitated by tumor-derived hematopoietic growth factors, such as monocyte colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) and granulocyte-monocyte CSF (GM-CSF). Other tumor products (e.g., IL-10, TGFß, and PGE) are important in this phase, as they play significant roles in the functional polarization of monocytes/macrophages into immunosuppressive cells.23,24

Notably, tumor-produced CSFs also have systemic effects on bone marrow hematopoietic progenitors and stimulate the “emergency myelopoiesis”, with increased production of monocytes, neutrophils and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). This is clearly evident in preclinical murine tumor models but has also been described in human cancer. This myelopoietic response is governed by cancer cell-produced growth factors, including the abovementioned CSFs, and is dependent on the transcription factor C/EBPβ. The C/EBPβ-driven expansion of myeloid cells, including MDSCs, is also positively regulated by retinoic acid-related orphan receptor C expressed in immature cells.25,26

The intrinsic heterogeneity of macrophages was initially described as two main categories: the M1 type (classically activated) and the M2 type (alternatively activated). This M1/M2 classification is now too limited for TAMs, due to their great diversity, although overall, most TAMs more closely resemble M2 macrophages and are reported to be M2-like cells.27–29

Phenotyping of TAMs by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry has shown that these cells express typical myeloid surface markers such as CD68; CD163; C-type lectin receptors including CD206, MGL, MARCO and, more recently, the tetraspan molecule MS4A4A;30 and immune checkpoint molecules, such as PD1/PD-L1 and VISTA.31–33 Markers such as CD68, CD163 and CD206 have been useful in defining, characterizing and enumerating TAMs in human tumors; they also constitute candidate prognostic variables for cancer patients. Indeed, most of what we know about the prognostic role of TAMs comes from studies that have used these markers.

Tumor-associated neutrophils

Neutrophils originate in the bone marrow, and their maturation is orchestrated by granulocyte CSF, GM-CSF, and IL-6 (Fig. 1).34–36 As mentioned above for myelomonocytic cells, alterations in the hematopoietic process occur in tumor-bearing mice and cancer patients, leading to neutrophilia and the appearance of immature myeloid cells in the blood.11,26,37–39 Circulating neutrophils express the chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2, and their recruitment to tumor tissues is regulated mainly by CXC chemokines.11,26,37–40 Other molecules, such as the complement components anaphylatoxin C5a and tumor-derived oxysterols, can also contribute to the recruitment of neutrophils to the TME.41–43

Identification of TANs by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry has been mainly performed with CD66b in humans and lymphocyte antigen 6G (Ly6G) in mice, in addition to CD45 and CD11b.12,39,44 This basic phenotypic definition includes a number of distinct subsets, such as immature and mature neutrophils, neutrophils expressing a set of interferon-stimulated genes and neutrophils with a distinct density (i.e., low-density neutrophils and high-density neutrophils).12,44 There is no consensus regarding the nomenclature for the diversity and plasticity of neutrophils in cancer or defining neutrophils with protumor or antitumor activities (recently reviewed in12). However, some molecules have been proposed to identify neutrophil subsets associated with the antitumor response, including CD177,45 and CD101,46 or the protumor response, including lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor 1 (LOX1),47 CD117,48 and PD-L1.48–50

Ever-increasing myeloid diversity

Recently, methods with single-cell resolution, such as RNA sequencing and mass cytometry by time-of-flight (CyTOF), have revealed an unprecedented level of diversity within the myeloid compartment of tumors. Numerous cancer types including lung cancer,51–53 brain cancer,54,55 breast cancer,56 ovarian cancer,21 head and neck carcinoma,57 melanoma,58 renal cancer,59 and colorectal liver metastases60 have already been analyzed. The myeloid population can be dissected into several distinct clusters based on differential gene or marker expression. Furthermore, the location of myeloid cells in the TME, as well as their morphological features, may be correlated with specific functions. In a recent paper, a single-cell analysis of human TAMs from liver metastases derived from colorectal tumors revealed that a simple morphometric feature of TAMs, their size (cell area), correlated with clinicopathological variables. Interestingly, large TAMs were associated with a poorer survival rate than small TAMs.60

Relatively few studies aimed at deciphering the diversity of neutrophils in cancer have been published. Interestingly, single-cell RNA sequencing of TANs from human and mouse lung tumors revealed the presence of a continuum of activation states conserved between the species.51–53 Five and six neutrophil subsets have been identified in human and mouse tumors, respectively. Among these clusters, three modules of gene expression are conserved between human and mouse TANs, consisting of neutrophils expressing canonical neutrophil markers, neutrophils expressing inflammatory cytokines (e.g., CCL3 and CSF1) and neutrophils expressing type I interferon-response genes (e.g., IRF7 and IFIT1).

Overall, the substantial amount of data generated with single-cell approaches constitutes an extraordinary cell atlas available to the scientific community. Efforts are now focused on recognizing the functional relevance of the different myeloid clusters and identifying which genes/markers are specifically expressed by tumor-supporting TAMs/TANs and which by immunostimulatory myeloid effectors. This distinction would provide a great advantage for clinical translation and could be exploited in the design of more specific targeted strategies in clinical settings, as well as in the choice of markers with prognostic potential.

Tumor-promoting functions of myeloid cells in tumors

Tumor-associated macrophages

In most but not all human tumors, high infiltration of TAMs is associated with a poor patient prognosis,1–6 with notable exceptions such as colorectal cancer.

Macrophages may exert both pro- and antitumor activities, depending on their functional activation state in the TME. The antitumor potential of monocytes/macrophages includes tumor cell killing, phagocytosis and scavenging of tumor debris, recruitment/activation of NK cells, and activation of Th1 immune responses.31,61–63 The tumor-promoting functions of TAMs are diverse and may impact on the different stages of tumor progression, from cancer initiation to metastasis, contributing to different hallmarks of cancer (Fig. 1). TAMs may directly promote tumor cell proliferation through the production of growth factors, such as epidermal growth factor, which induces cancer cell proliferation, and the support of epithelial–mesenchymal transition in tumor cells.64 In the initial phase of carcinogenesis, the reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates released by myeloid cells may contribute to DNA damage and genetic instability.65 At more advanced stages, M2-like macrophages can be found in the metastatic cell niche, where they exert trophic functions while promoting tumor-initiating cell evasion of immune clearance.66,67 Indeed, TAMs support cancer stem cell expansion by producing several mediators, such as IL-6, PDGF, MFG-E8, hCAP-18/LL-37 and, as recently reported, the protein glycoprotein nonmetastatic B (GPNMB).68–71 Furthermore, macrophage-derived cytokines, such as IL-1, promote the recruitment and seeding of metastatic cancer cells at niche sites.66,72,73

In addition, TAMs act indirectly by impacting different cell types or the extracellular matrix of the TME. Macrophages activated by type II cytokines (IL-4 or IL-13) and other environmental factors contribute to tissue repair, remodeling and fibrosis.74 In tumors, macrophages promote the recruitment of myofibroblasts and release or activate TGFβ1. In specific tumors, such as early pancreatic adenocarcinoma18 and colon cancer,75 macrophages also have a direct profibrotic role mediated by depositing extracellular matrix components.

TAMs are crucial promoters of the neoangiogenic switch in tumors. Hypoxia, a major driver of angiogenesis in cancer tissues, induces the upregulation of HIF-1α expression and secretion of proangiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A).76 Accordingly, the TAM frequency correlates with the vascular density in preclinical tumor models and human tumors.77 Macrophage depletion through Csf1 inactivation, clodronate liposome administration or CSF1 receptor (CSF1R) inhibition has been associated with reduced angiogenesis in tumors in different preclinical models, including the tumors of MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice.78,79 In addition, VEGF-A deficiency in TAMs was found to reduce angiogenesis and abnormalities in tumor vessels in mouse cancer models but to increase tumor growth,80 indicating that myeloid-derived VEGF-A is essential for the tumorigenic alteration of the vasculature and that this alteration delays tumor progression. TAMs are a source of additional angiogenic factors, chemokines with proangiogenic and prolymphangiogenic potential and inflammatory cytokines, including placental growth factor, fibroblast growth factor 2, VEGF-C, TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, and CXCL8.81

Moreover, myeloid cells produce different types of proteases, such as members of the MMP and cathepsin families, that mobilize ECM-bound VEGF-A and other factors. A subset of TAMs expressing the receptor TIE2 associates with endothelial cells and promotes angiogenesis by releasing proangiogenic and tissue-remodeling factors. Inhibition of the angiopoietin 2-TIE2 axis reduces angiogenesis as well as leukocyte recruitment and interactions between endothelial cells and TIE2-expressing TAMs, thereby inhibiting tumor growth.82,83

TAMs are major drivers of immunosuppression in the TME. Mediators released by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, such as Th2 cells and Treg cells (producing IL-4 and Il-10), and by tumor cells (IL-10, TGFβ, and PGE2) activate an immunosuppressive program in TAMs.23,24 Furthermore, in mouse and human melanoma, IL-1 was shown to induce the upregulation of the expression of TET2, a DNA methylcytosine dioxygenase, which sustained the immunosuppressive functions of TAMs.84

Recently, complement anaphylatoxins have been shown to contribute to TAM-dependent T cell suppression.42,85 In agreement with the evidence of a protumor role for complement in cancer, the humoral pattern recognition molecule PTX3 has been identified to act as an extrinsic oncosuppressor gene, acting through the regulation of complement-dependent and macrophage-sustained tumor-promoting inflammation in sarcomas.86,87 The activation of this program in macrophages leads to direct immunosuppressive effects on cytotoxic T cells and to indirect effects on adaptive immune responses through the recruitment and activation of Tregs and Th2 cells via chemokines (e.g., CCL17 and CCL22), as well as inhibition of DCs and defective T cell recruitment through abnormal vessels or the fibrotic ECM. In particular, monocyte-related MDSCs inhibit the development of antitumor adaptive immunity in lymphoid organs and effector immune responses in the tumor itself.37 Myelomonocytic cells also promote metabolic starvation of T cells due to the activity of arginase and production of amino acid metabolites by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). Finally, TAMs express the ligands of checkpoint molecules, such as PD-L1, PD-L2, B7 ligands,88 and VISTA,89 which suppress adaptive T cell immune responses and promote Treg recruitment.4,90

As mentioned above, TAMs also facilitate the invasive behavior of cancer cells and metastatic progression through the release of proteolytic enzymes involved in ECM digestion.91

Tumor-associated neutrophils

The role played by neutrophils in cancer is controversial, as both protumor and antitumor activities have been attributed to TANs.11,12 In patients with cancer, high levels of peripheral blood neutrophils and TANs and a high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio have been generally associated with a poor prognosis and low response to treatment.12,39 Neutrophils are an important component of tumor-promoting inflammation and have been associated with genetic instability, proliferation of tumor cells, extravasation of circulating tumor cells, metastasis, angiogenesis and suppression of antitumor immunity.11,12,92–96

In contrast with these findings, neutrophils can kill tumor cells through direct cytotoxic activity mediated by the generation of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide, expression of TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL) and activation of antitumor immunity.10,97–100 In response to IFNγ and GM-CSF, TANs acquire antigen-presenting cell (APC) features and the capacity to stimulate the proliferation of both CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells.97,98 In addition, a recent investigation showed a tripartite interaction among neutrophils, macrophages and a subset of unconventional T cells (defined as TCRαβ+ CD4- CD8-) that sustained the development of effective IFNγ-dependent antitumor immunity.99

The dual role played by TANs in cancer may be explained by their diversity and plasticity.36 Indeed, reflecting the dichotomy of M1 and M2 macrophages, N1-N2 nomenclature has been proposed for antitumor and protumor neutrophils, respectively.10,12 In particular, TGFβ polarizes neutrophils into a protumor state characterized by high arginase expression and immunosuppressive activity towards T cells,10 while IFNβ and a combination of IFNγ and GM-CSF stimulate neutrophil polarization into an antitumor phenotype characterized by cytotoxic activity towards tumor cells and acquisition of APC features.97,98

Overall, both TAMs and TANs in the TME may display contrasting functional activities. A better understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in the diversity of myeloid cells in cancer is essential for the development of specific therapeutic strategies targeting TAMs and TANs.

Myeloid cell interference with anticancer therapies

Tumor-associated macrophages

The multitude of studies aimed at addressing the function and prognostic role of macrophages and neutrophils in human cancer provides information to explore whether these phagocytes contribute to the efficacy of anticancer strategies. Both positive and negative interactions have been documented, either limiting or reinforcing the effect of anticancer strategies.3,101–103 This is not surprising, as this variability reflects the complexity of the microenvironment and heterogeneity of myeloid functions.

Interference with conventional anticancer strategies: chemotherapy and radiotherapy

In conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy, macrophages have been shown to either boost or limit the therapeutic effect. The observed positive interactions acquire particular relevance from the perspective of combinatorial strategies including chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Immunogenic cell death (ICD) is certainly the principal mechanism of potentiation observed when doxorubicin, oxaliplatin and cyclophosphamide are used. ICD implies the release of “eat-me” signals from tumor cells, activating the phagocytic and antigen-presenting activities of macrophages.101,104–108 In addition, chemotherapy can directly modulate the macrophage phenotype, reprogramming TAMs towards an antitumor phenotype, an effect observed with gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer,109 5-fluorouracil in colorectal cancer110 and docetaxel in a preclinical model of breast cancer.111 In human studies, this interaction results in the association of a high density of macrophages with better prognosis only in chemotherapy-treated patients. Preclinical models, however, document primarily negative effects of macrophages on the responsiveness to chemotherapy; the several mechanisms identified include orchestration of an immunosuppressive response, tissue repair-related functions, nourishment of tumor cells and prometastatic activity.3,102,103 In line with these findings, depletion of TAMs with anti-CSF1/CSF1R antibodies was found to result in enhanced chemosensitivity to a combinatorial chemotherapeutic approach in human breast cancer xenografts112 and more recently in a genetic mammary tumor model.113 Macrophage infiltration was found to be associated with chemoresistance to 5-fluorouracil in colon cancer cell lines,114 and macrophage depletion increased responsiveness to paclitaxel (PTX) treatment in breast cancer.115 Other actions of TAMs that foster chemoresistance include the release of growth factors protecting tissues from chemotherapy-induced damage.68,116 The density of macrophages localized in proximity to blood vessels, namely, perivascular macrophages, was shown to be increased after chemotherapy treatment and to promote tumor revascularization and relapse in both mouse tumors and human tumors.117 Of note, paclitaxel and doxorubicin increase the ability of perivascular macrophages to promote tumor cell metastasis.118

Macrophage interference with the effects of irradiation is controversial, possibly depending on the tissue type and immune infiltration.119,120 Radiation therapy profoundly affects the composition of the TME, inducing important modifications that can affect the overall immune response and eventually lead to recruitment of tumor-promoting macrophages.121 For instance, radiation therapy induces TGFβ,122 a potent immunosuppressive agent. Additionally, TAMs and other myeloid suppressor cells have been shown to drive a fibrotic reaction that can promote tumor recurrence. Notably, these negative outcomes could be blocked by the administration of a selective inhibitor of CSF-1R.123 Nonetheless, macrophages contribute to the systemic “abscopal” effect induced by radiotherapy, a condition whereby tumor regression occurs at sites distant from the irradiated lesions. In agreement, neoadjuvant low-dose irradiation has been shown to elicit immunostimulatory macrophage functions in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma.119,120

Interference with unconventional anticancer strategies: mAb-mediated targeted therapy and immunotherapy

While conventional therapies primarily target cancer cells, more recent treatments, especially mAb-based targeted therapies and immunotherapies, more profoundly rely on the engagement of myeloid cells.5

As professional phagocytes, macrophages are fully capable of phagocytosing124 and lysing tumor cells,125 critical tasks to be considered when a tumor-specific antibody is used. In fact, these therapies are based on the capability of therapeutic antibodies to trigger antitumor activity, such as blockade of tumor survival signals, neutralization of tumor growth factors, activation of complement and triggering of immune cells expressing Fcγ receptors (FcγR), to induce antibody-dependent cytotoxicity (ADCC) and phagocytosis.125–127 There is a growing number of therapeutic antibodies targeting tumor-specific antigens currently being used in the clinical setting (including rituximab targeting CD20,128,129 trastuzumab targeting ERBB2,126,130–132 cetuximab targeting EGFR,125 and daratumumab targeting CD38 in myeloma cells133). The tissue localization of macrophages in the tumor microenvironment of many cancer types makes these phagocytes ideal mediators of the efficacy of such antibodies. Functional polymorphisms in human FcγRIIIA may affect the antibody-mediated cytotoxicity of monocytes/macrophages and correlate with response rates. This has been shown in lymphoma patients treated with rituximab,134 breast cancer patients treated with trastuzumab132 and metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with cetuximab.135

As discussed below, macrophage phagocytic activity can be inhibited by CD47, a ubiquitously expressed transmembrane protein that functions as a “don’t eat me signal” and is overexpressed in many cancer types. CD47 mediates the resistance of tumor cells to macrophage phagocytosis by binding to SIRPα, a negative regulator of macrophage phagocytosis, and limits the antitumor efficacy of therapeutic antibodies.136–139 For this reason, targeting CD47 in combination with mAb-based therapies is being evaluated in clinical settings.140

In immune checkpoint-targeted immunotherapy, macrophages have been shown to affect the efficacy of immunomodulatory antibodies that target membrane molecules with regulatory functions, such as checkpoint inhibitors, in multiple ways. The mechanism of action of checkpoint inhibitors entails the blockade of negative signal transduction in T cells. Nonetheless, it has been shown that FcR-mediated depletion of Treg cells by macrophages is required for the therapeutic antitumor effects of checkpoint inhibitors directed against CTLA-4.141,142 This suggests that the tissue localization of macrophages in the tumor microenvironment can significantly contribute to this function. Another level of complexity is added by the expression of checkpoint ligands (such as PD-L1, PD-L2, B7-1, and B7-2) on macrophages,88,143,144 which makes TAMs a direct target of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Another mechanism of interaction with checkpoint inhibitors is provided by the expression of PD-1 by TAMs, which has been shown to negatively correlate with phagocytic activity against tumor cells.31

Recently, histopathological analysis of non-small cell lung cancer specimens from patients treated with anti-PD1 therapy in the neoadjuvant setting, identified macrophages in the regression bed (the area of immune-mediated tumor clearance), and macrophage assessment has been used to build an irPRC (immune-related pathologic response criteria) scoring system,145 which could be exploited to identify standardized assays to assess immunotherapeutic efficacy.

As with chemotherapy, however, contrasting evidence on the interaction of immunotherapy with myeloid cells also exists. Depletion of macrophages has been shown to potentiate various immunotherapeutic strategies, including vaccination146 and checkpoint inhibition.147–149

On the whole, these observations suggest the hypothesis that strategies aimed at targeting macrophages and neutrophils may be more effective if tested in combination with conventional cancer therapies. The preclinical and clinical evidence derived from such attempts varies significantly according to tumor type, and efforts are ongoing to identify the best combination option.

Tumor-associated neutrophils

Interference with conventional anticancer strategies: chemotherapy and radiotherapy

The impact of neutrophils on treatment responses to conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy is complex. Evidence from in vitro experiments and an in vivo transplantation mouse model of breast cancer suggests that cytoreductive agents, such as 5-FU, gemcitabine and doxorubicin, unleash adaptive immune responses by causing neutrophil apoptosis.150,151 In addition to eliminating immunosuppressive neutrophils, 5-FU and gemcitabine can activate the inflammasome and IL-1β secretion in neutrophils.152 In turn, IL-1β sustains the secretion of IL-17 by CD4+ T cells, promoting tumor inflammation and resistance to chemotherapy.152 In apparent contrast with these observations, neutrophils have also been associated with a good response to chemotherapy in patients with gastric, colorectal or high-grade ovarian cancer.153–155 Further studies are needed to determine the functional mechanism by which neutrophils can improve the response to chemotherapy. Colocalization of TANs and CD8+ T cells has been observed in human colorectal cancer sections, suggesting that neutrophils may support antitumor adaptive immunity.154 Thus, whether neutrophils have a beneficial or detrimental impact on the response to chemotherapy is still debated and may depend on the cancer type, stage or treatment. Clinical studies of cancer patients treated with radiotherapy have demonstrated that high levels of blood neutrophils and TANs are associated with poor overall survival.156 However, in different mouse models of tumor cell line transplantation, radiotherapy was shown to induce rapid and transient infiltration of neutrophils with cytotoxic activity against tumor cells, and neutrophil depletion reduced treatment efficacy.157 Therefore, the role played by neutrophils in response to radiotherapy remains to be elucidated.

Strategies to target tumor-associated macrophages

The critical role that TAMs play in cancer progression has propelled a considerable number of studies aimed at targeting TAMs with varying approaches.

Depletion or inhibition of TAM infiltration in tumors

Early attempts to reduce the number of macrophages in tumors employed bisphosphonates, which have long been studied in the treatment of osteoporosis. Bisphosphonates are selectively adsorbed into bone tissues, where they are internalized by osteoclasts and induce their apoptosis. Some preclinical studies have reported positive effects on tumors, especially bone metastases, which has created interest in the clinical use of these compounds in the treatment of bone-metastatic breast and prostate cancers in combination with chemotherapy or hormonal therapy.3,4

Another early approach to reduce the macrophage content of tumors was to inhibit the chemoattractants that regulate monocyte recruitment to the tumor site. Chemokine inhibitors, such as an anti-CCL2 mAb or CCR2 blockade, have been tested with some success in experimental tumors.158

Anti-CCR2 antibodies and small-molecule inhibitors entered clinical trials for patients with solid tumors but did not produce substantial positive results, even when combined with chemotherapy or immunotherapy.159,160 A likely explanation is the large redundancy of the chemokine system, which contains many different ligands and receptors. CXCL12 is another chemokine involved in monocyte recruitment that has been targeted for therapeutic purposes. Inhibition of CXCR4 with the antagonist AMD3100 (plerixafor) is under evaluation in patients with solid and hematological tumors (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=Neoplasia&term=plerixafor&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=). Olaptesed pegol (NOX-A12), a pegylated l-oligoribonucleotide (aptamer) that binds to and neutralizes CXCL12, is being tested in patients with metastatic solid tumors (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=neoplasia&term=olaptesed&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=).

As mentioned above, CSF1 receptor (CSF-1R) has attracted interest as a potential target molecule, primarily because it is exclusively expressed by cells of the monocytic lineage, and its specific ligand CSF-1 (M-CSF) is the master regulator of macrophage survival and differentiation. Different types of inhibitors of CSF-1R (antibodies and small molecules) have been developed and tested with success in experimental mouse models, showing antitumor activity.147,161,162 In patients, inhibitors of CSF1-R (PLX7486, PLX3397 and the mAb AMG820) are now being evaluated in several clinical studies in combination with conventional or targeted chemotherapy and with checkpoint blockade immunotherapy or radiotherapy.163,164 In addition to blocking the recruitment and viability of macrophages, inhibition of CSF-1R alone or in combination with other therapies has other effects and stimulates the reprogramming of TAMs towards an antitumor M1 phenotype.161

Another approach to eliminate macrophages is the use of chemotherapeutics that specifically affect the monocytic cell lineage. Trabectedin, a compound of marine origin, is a registered antineoplastic drug used in soft tissue sarcoma and ovarian cancer.165 In addition to killing tumor cells, trabectedin exhibits selective cytotoxicity to monocytes and macrophages and reduces the numbers of monocytes in the circulation and TAMs in tumors through a TRAIL-dependent apoptotic pathway.166 The antitumor efficacy of trabectedin, through its effects on TAMs, has been reported in preclinical models of bone metastatic prostate tumors, melanoma and pancreatic tumors.166–170

Nevertheless, the prospect that nonspecific depletion of monocytes/macrophages may be harmful, as their roles in host defense and homeostasis are crucial, must be considered.171 Given the phenotypic heterogeneity of TAMs, it is critical to apply a relatively selective targeting approach and impact only specific subsets. A good example was recently reported. The scavenging receptor CD163 defines a subset of TAMs that mediate immune suppression in an experimental model of melanoma. Specific depletion of CD163+ TAMs induced the infiltration of activated T cells and inflammatory monocytes, which both contributed to tumor regression. Interestingly, pantargeting of TAMs nullified the therapeutic effects achieved with the specific targeting of CD163+ TAMs, clearly indicating the importance of the more focused and informed approach.172

Strategies to reprogram TAMs into antitumor effectors

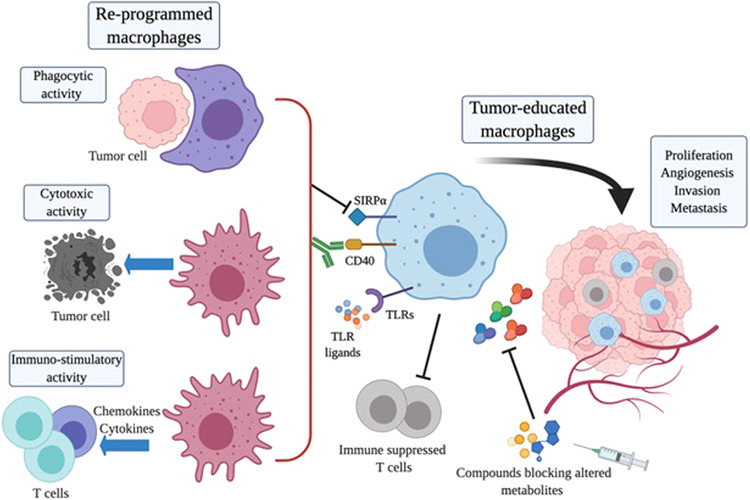

Macrophages activated in an antitumor state have the potential to kill and phagocytose cancer cells; they can also limit tumor growth via the secretion of activating factors and chemokines that stimulate and recruit effector T cells. The remarkable functional plasticity of macrophages is the rationale for developing approaches to switch cells from M2-like immunosuppressive TAMs into M1-like immunostimulatory and antitumor cytotoxic effectors (Fig. 2). Functional reprogramming of TAMs, or global activation of innate immunity against cancer cells, was tested long ago, for instance, with the use of microbial molecules (bacterial muramyl dipeptide and BCG) or cytokines (IFNs).3,173

Fig. 2.

Strategies for reprogramming macrophages in cancer. Tumor-educated macrophages have several tumor-promoting functions. Strategies to reprogram TAMs into M1-like antitumor effectors are depicted in the figure. Blockade of SIRP1α molecules with inhibitory antibodies reactivates the phagocytosis of tumor cells. Agonistic antibodies specific for the receptor CD40 or ligands of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) trigger TAM antitumor cytotoxic activity and induce the production of immunostimulatory cytokines and chemokines that recruit and activate T cells as part of an adaptive immune response. The altered metabolism of the tumor environment impacts the functional activity of TAMs; compounds inhibiting specific metabolic factors may relieve the stress caused by altered tumor metabolism and rewire the functional activity of macrophages

Targeting cell-surface receptors on TAMs

In more recent years, specific surface receptors on macrophages have been targeted with antibodies. An agonistic anti-CD40 mAb mimics the effect of the ligand CD40L expressed by activated T cells and has been demonstrated to be effective in stimulating cytotoxic macrophages.174 Anti-CD40 mAbs are under clinical evaluation in combination with checkpoint immunotherapy, chemotherapy or targeted therapies in patients with advanced solid tumors.174

As noted previously, the CD47-SIRPα axis inhibits phagocytosis by macrophages. Pharmacological blockade of CD47 has been shown to restore the phagocytosis and killing of tumor cells and produce tumor regression in various preclinical cancer models.139 Based on the idea that targeting the CD47-SIRPa axis could complement antitumor antibodies and possibly reinforce their efficacy, an anti-CD47 blocking antibody has been used in combination with rituximab,136,175 and nonfunctional engineered SIRPα variants have been used as adjuvants for antitumor antibodies, including rituximab, cetuximab and trastuzumab, with promising results.176 Other clinical trials of anti-CD47 mAbs in combination with anti-PD-1 therapy are now underway. (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=neoplasia&term=CD47&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=).

The C-type lectin receptor CD206 is a phagocytic receptor typically expressed in M2-polarized macrophages and abundantly present on TAMs. Using the synthetic peptide RP-182 specific for CD206, Jaynes et al. demonstrated that peptide treatment reprogrammed TAMs to an antitumor M1-like phenotype with increased production of inflammatory cytokines and the ability to phagocytose cancer cells.177 In murine cancer models, RP-182 suppressed tumor growth, extended survival and synergized with immunotherapy.

Another C-type lectin receptor of interest expressed by TAMs is Macrophage Receptor with Collagenous structure (MARCO). In murine tumor models of breast cancer, colon cancer and melanoma, anti-MARCO mAbs have induced significant antitumor activity by reprogramming TAMs into proinflammatory effectors, thereby increasing tumor immunogenicity. Interestingly, the antitumor activity of an anti-MARCO Ab was dependent on the inhibitory Fc-receptor FcgRIIB.178

Targeting toll-like receptors on TAMs

Innate immune cells are rich in Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) of microbes and initiate signaling in cells to activate an inflammatory immune response.179,180 Historically, BCG (Bacillus Calmette-Guérin), which stimulates TLR2 and TLR4, was the first FDA-approved TLR-stimulating agent and, after decades, is still used to treat bladder cancer in combination with anti-PD-1 therapy.181,182 The receptors TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 are located in the endosomal compartment, where they recognize pathogen-associated nucleic acids. Several in vitro and in vivo preclinical studies have investigated the potential activity of synthetic compounds specific for these TLRs to reprogram TAMs into antitumor effectors. Ligands trigger the secretion of immunostimulatory cytokines, including the antitumor type I IFN pathway. In addition to macrophages, dendritic cells are also stimulated by TLR agonists, and among these cells, the pDC subset is the most potent in producing type I IFNs.180,183 To date, only imiquimod (TLR7 agonist) has been approved by the FDA for the topical treatment of squamous and basal cell carcinomas. Other compounds, such as poly I:C (TLR3 agonist), resiquimod and NKTR-262 (TLR7/8 agonists) and CMP-001 and tilsotolimod (TLR9 agonists), have been developed and are being evaluated in early-phase clinical trials, either as adjuvants for cancer vaccines to boost antitumor responses or in combination with other treatments.184

The analogue poly-ICLC (stabilized with polylysine and carboxymethylcellulose to improve drug pharmacokinetics) is one of the most extensively investigated compounds, with more than 100 clinical trials. In phase I/II trials, poly-ICLC has been used either as an antitumor vaccine adjuvant or in combination with anti-CTLA4, anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 mAbs in patients with advanced disease (https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials/intervention/poly-iclc).

The topical application of TLR agonists in cutaneous neoplasms or intratumoral injection into accessible lesions has been safe, with low-grade adverse events, such as flu-like symptoms and hypotension. Evidence that these agents trigger the IFN response has been reported in some studies showing increased production of cytokines and infiltration of CD8+ T cells. The TLR7/8 agonist resiquimod (R848) is an analogue of imiquimod. In vitro and preclinical studies have demonstrated that R848 treatment triggers a strong antitumor response.185 In clinical trials, topical administration or local injection of R848 is being evaluated in melanoma patients in combination with vaccine therapy (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=neoplasia&term=R848+&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=).

Other TLR7/8 agonists are in phase III trial evaluation for skin neoplasia, anal carcinoma and cervical intraepithelial lesions.184 The TLR8 agonist motolimod, in combination with cetuximab, was shown to induce partial responses and disease stabilization in some patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer.186 The TLR9 agonist DV281 is currently being evaluated in a phase 1b/2 study in combination with nivolumab in patients with advanced NSCLC.187 In patients with metastatic melanoma, SD-101, another TLR9 agonist, has been investigated in combination with immunotherapy.188,189

Although most clinical trials with TLR agonists have been conducted to test drug safety, shrinkage of injected lesions has been observed in some patients. These promising results further support combination of TLR agonists with checkpoint inhibitors to treat progressing patients who are nonresponsive to immunotherapy, based on the rationale of further boosting immunity and “warming” immunologically cold tumors.

Targeting signaling pathways to reprogram TAMs

PI3Kγ is a myeloid-specific isoform of the PI3K family. PI3Kγ regulates innate immunity by activating C/EBPβ in response to inflammation but also simultaneously negatively regulates NF-κB activation. Thus, PI3Kγ acts as a key immunosuppressive pathway in myeloid cells, and pharmacological inhibition of PI3Kγ signaling has been studied in preclinical tumor models. Kaneda et al. reported that selective inhibition of PI3Kγ reverted immunosuppression and induced CD8+ T cell recruitment into the TME and tumor growth inhibition.190 The combination of PI3Kγ inhibitors with other therapeutics, including vasculature disrupting agents, other kinase inhibitors and checkpoint inhibitors, has been even more effective.191–193 There are hundreds of ongoing clinical trials using pan-PI3K inhibitors, but only a few early-phase studies have employed specific inhibitors of the myeloid γ isoform in cancer patients (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=neoplasia&term=PI3K%CE%B3&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=).

Another strategy that has been proven to be successful is the epigenetic modulation of TAMs with histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, especially the selective class IIa inhibitor TMP195. In the MMTV-PyMT mammary tumor model, treatment with TMP195 stimulated macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of tumor cells and TAM reprogramming into proinflammatory immunostimulatory effectors.194 Combined treatment with TMP195 and chemotherapy or anti-PD-1 therapy resulted in increased antitumor effects. Interestingly, a combination of low-dose adjuvant epigenetic compounds reduced metastatic spread in a preclinical metastasis model (after removal of the primary tumor).195 The effects were mainly mediated via the inhibition of myeloid cell recruitment in premetastatic niches.

Metabolic modulation to reprogram TAMs

In recent years, a number of studies have highlighted the important implications of altered cancer metabolism on the biology and functional activities of macrophages, with these changes in metabolism generally shifting macrophage polarization towards a tumor-promoting phenotype.196 Therefore, metabolic modulation has been tested as a potential strategy to reprogram TAMs towards an antitumor state. Tumor-derived metabolites, such as adenosine, glutamine and lactate, have been mostly studied and tested in preclinical models to assess their effects on tumors. In a recent paper, Powell’s group employed a small molecule (prodrug of 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine) to target glutamine.197 Glutamine metabolism is important in crucial biological functions, such as nucleotide synthesis, amino acid production, redox balance, glycosylation and extracellular matrix production.198 In their study, Powell et al. demonstrated that blocking glutamine metabolism in a mouse breast cancer model reduced tumor growth and metastases not only by acting on tumor cells but also by enhancing macrophage activation and inhibiting MDSC generation.197

In a study employing a different strategy to target the same metabolic pathway, Mazzone’s group used an inhibitor of the enzyme glutamine synthase, which generates glutamine from glutamate. The glutamine synthase inhibitor glufosinate reduced metastasis formation in highly metastatic mouse models of melanoma and breast and lung cancer.199 The treatment also reduced angiogenesis and immunosuppression, with reprogramming of TAMs into antitumor effectors.

Tumor-derived lactate promotes M2 macrophage polarization200 via activation of the ERK/STAT3 signaling pathway or the sensor protein Gpr132 expressed by macrophages. Pharmacological inhibition of the ERK/STAT3 axis with selumetinib or stattic, or of the Gpr132 protein hampered lactate-induced M2 macrophage polarization and showed significant antitumor effects in preclinical studies.201,202

Another tumor metabolite, extracellular adenosine, affects the functions of TAMs, such as phagocytosis and the production of cytokines, including macrophage-derived VEGF.203 Deletion of the adenosine receptor A2A in myeloid cells has been shown to prevent tumor progression and metastasis in melanoma tumor models.204

It has long been known that TAMs and MDSCs produce substantial levels of indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase (IDO), which converts tryptophan into kynurenine. This potent immunosuppressive pathway inhibits cytotoxic T cells and favors the expansion of Treg cells.205 IDO inhibitors are now being tested in clinical trials in combination with other therapies (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=IDO&Search=Search).

Overall, these findings support the concept that metabolic rewiring of the tumor microenvironment has significant positive effects on TAMs; however, the potential for therapeutic intervention in cancer patients remains to be investigated.206

Cell therapy with macrophages expressing chimeric antigen receptors

Cell therapy with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells genetically engineered to recognize the CD19 antigen has been approved by the FDA for hematological malignancies.207 Macrophages are historically more resistant to transduction procedures than lymphocytes. In a recent paper, Klichinsky et al. succeeded in transducing an anti-HER2 CAR into primary human macrophages (CAR-Ms) using a modified replication-incompetent adenovirus. They demonstrated that CAR-Ms with sustained expression of the transgene efficiently reduced tumor volume in immunodeficient mice bearing HER2-positive human tumors.208 The high efficiency of this technique opens new avenues for the use of engineered macrophages in cell therapy settings.

Strategies to target tumor-associated neutrophils

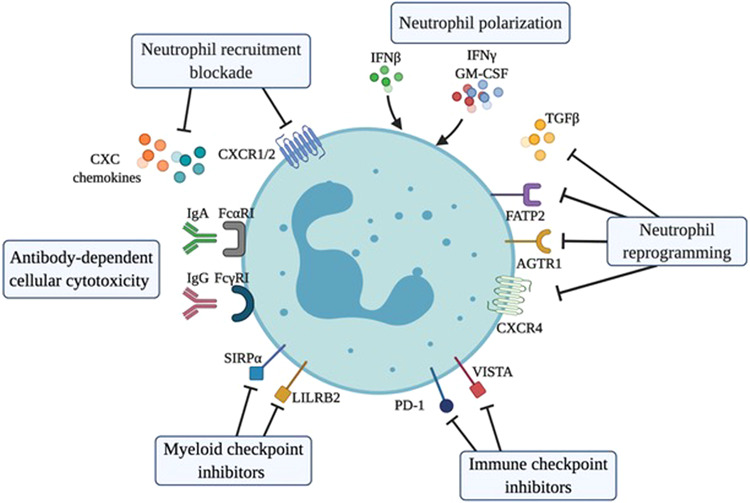

Preclinical studies have provided the basis for the development of neutrophil-targeting approaches in cancer treatment12 (Fig. 3). For instance, strategies to inhibit neutrophil mobilization and recruitment in tumors by blocking CXCL8 or the chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 are now being evaluated in clinical trials.40,209,210 In addition, approaches to reprogram neutrophils into an activated antitumor state have been proposed, including reduction of tumor hypoxia100 and blockade of selected molecules, such as TGFβ,10 fatty acid transport protein 2,211 CXCR4,212 angiotensin converting enzyme,213 angiotensin II type 1 receptor,213 and nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase.214

Fig. 3.

Strategies for targeting neutrophils in cancer. Inhibition of CXC chemokines or their receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 can limit the mobilization and recruitment of neutrophils into the tumor microenvironment. Treatment with IFNβ or GM-CSF + IFNγ or blockade of TGFβ, AGTR1, FATP2 or CXCR4 induces the polarization or reprogramming of neutrophils into an activated antitumor state characterized by cytotoxic activity towards cancer cells or activation of an antitumor immune response. Neutrophils express the ligands of the lymphocyte checkpoint molecules PD-1 and VISTA and the myeloid checkpoint molecules LILRB2 and SIRPα, which represent potential targets to inhibit the immunosuppressive activities of neutrophils and improve their effector activities. The expression of FcαRI and FcγRI by neutrophils represents a target for the elimination of antibody-opsonized cancer cells through the processes of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and trogoptosis

Increasing cytotoxic and phagocytic activities of neutrophils

As discussed above for macrophages, neutrophils express FcγRs and can kill tumor cells via ADCC.215 Therefore, in a mouse lymphoma model, depletion of neutrophils was found to decrease the efficacy of treatment with monoclonal antibodies directed against CD20 (rituximab) or CD52 (alemtuzumab).215 In addition to FcγRs, human neutrophils express FcαRI (also known as CD89), which is a high-affinity receptor for IgA and a strong inducer of ADCC.215,216 Interestingly, treatment with anti-CD20 IgA in mice genetically modified to express human FcαRI (mice do not express FcαRI) protected against lymphoma through the activity of cytotoxic neutrophils.217 Moreover, the IgA-mediated cytotoxic activity of neutrophils can be potentiated by blocking the CD47-SIRPα axis.218

The process of trogoptosis, which refers to the active transfer of plasma membrane between cells, can sustain the ADCC activity of neutrophils against cancer cells in vitro and in vivo.219 Interestingly, trogoptosis of tumor cells by neutrophils can be amplified by blocking the CD47-SIRPα axis.219 Further in vivo investigations have shown that the increased elimination of tumor cells achieved by anti-SIRPα therapy is altered upon neutrophil depletion.220

Collectively, these findings identify the CD47-SIRPα axis, targeted alone or in combination with therapeutic antibodies, as a promising target to increase the antitumor activity of neutrophils.

Targeting neutrophils through checkpoint inhibitors

Neutrophils express ligands of immune checkpoint molecules, including PD-L149,50 and V-domain immunoglobulin suppressor of T-cell activation (VISTA).89,221 In a preclinical tumor model, VISTA was found to inhibit the TLR-mediated activation of downstream signaling in myeloid cells. Blocking VISTA turned monocytes and DCs into proinflammatory cells that promoted the infiltration of T cells and activation of T cell-mediated antitumor immunity.221 Data demonstrating impacts of PD-L1 expression on neutrophil activities are increasing. In patients with gastric cancer or hepatocellular carcinoma, the presence of PD-L1+ neutrophils has been associated with a poor prognosis.222,223 Hypoxic conditions and stimulation with IFNγ or IL-6 can upregulate the expression of PD-L1 on neutrophils; PD-L1+ neutrophils suppress T cell activity in vitro, but this effect can be reversed by PD-L1 blockade.222,223 In addition to unleashing the adaptive immune response, blockade of PD-L1 on neutrophils has been proposed to enhance neutrophil cytotoxic activity against cancer cells expressing PD-1.224 Collectively, these findings suggest that neutrophils are a valuable target for PD-1/PD-L1 axis blockade.

In addition to PD-L1 and VISTA, other myeloid checkpoints, including CD200R,225 paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor alpha (PILRα),226 leukocyte immune-globulin-like receptor B2 (LILRB2)227 and SIRPα,228 are expressed on neutrophils. Recent investigations have also identified the expression of PD-1229 and atypical chemokine receptor 2 (ACKR2) on neutrophil precursors.230 The latter can act as a key regulator of myeloid cell differentiation; in fact, ACKR2 deficiency in mice induces the mobilization of neutrophils with increased cytotoxic activity towards cancer cells.230

The significance of the expression of CD200R and PILRα on neutrophils remains to be elucidated. In contrast, preclinical findings from mouse tumor models reveal that neutrophils can play a role in the efficacy of agents blocking the CD47-SIRPα signaling axis (see above) or the receptor LILRB2, which act as negative regulators of neutrophil activation.12,227,231

Concluding remarks

Tumor tissues are populated by a plenitude of myeloid cells that are highly heterogeneous in functional activity, localization and morphology and engage in complex bidirectional interactions with not only tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes but also other stromal components. Among immune populations, TAMs and TANs are major drivers of cancer immune suppression and are emerging as both indicators of cancer prognosis and promising targets for therapeutic intervention.

The role of myeloid cells in cancer has been recognized for a long time; however, only recently, high-dimensional analyses, which have increased the resolution of cell profiling to unprecedented levels, have shed new light on the variety of myeloid cells in the TME of many tumors. At the single-cell level, TAMs in primary tumors are considerably diverse, with distinct fingerprints relevant to cancer progression232,233 and response to therapy.234 At present, only one study employing single-cell analysis of TAMs in human metastases has been published.60 A more extensive analysis of the diversity of TAMs at metastatic sites of human cancer is warranted given the clinical significance of TAMs.

In addition, spatial assessment analyses have confirmed the localization of macrophages in the TME as an important determinant of function. Integration of high-resolution transcriptomics and spatial analyses could allow more refined definition of the distinct myeloid populations relevant to cancer. Finally, the significant correlations of TAM- and TAN-related features with clinical outcomes across cancers provide the foundation to test these features as prognostic indicators.

Overall, deeper knowledge of myeloid heterogeneity in cancer and the increasing recognition of the clinical relevance of myeloid cells hold promise for the development of a “Macroscore” that could complement the T cell-based “Immunoscore”235 in the clinic. In addition, the discovery of myeloid checkpoints12,175 may pave the way for the development of innovative immunotherapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to the results reviewed here has received funding from Associazione Italiana Ricerca Cancro (AIRC): AIRC 5X1000 IG-21147 to A.M.; the funding agency had no role in the preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ruffell B, Coussens LM. Macrophages and therapeutic resistance in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engblom C, Pfirschke C, Pittet MJ. The role of myeloid cells in cancer therapies. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016;16:447–462. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mantovani A, et al. Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017;14:399–416. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cassetta L, Pollard JW. Targeting macrophages: therapeutic approaches in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018;17:887–904. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeNardo DG, Ruffell B. Macrophages as regulators of tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019;19:369–382. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0127-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura K, Smyth MJ. Myeloid immunosuppression and immune checkpoints in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2020;17:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0306-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geissmann F, et al. Unravelling mononuclear phagocyte heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010;10:453–460. doi: 10.1038/nri2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiss M, et al. Myeloid cell heterogeneity in cancer: not a single cell alike. Cell Immunol. 2018;330:188–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Locati M, Curtale G. Mantovani A. Diversity, mechanisms, and significance of macrophage plasticity. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2019;15:123–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fridlender ZG, et al. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coffelt SB, Wellenstein MD, de Visser KE. Neutrophils in cancer: neutral no more. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016;16:431–446. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaillon S, et al. Neutrophil diversity and plasticity in tumour progression and therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2020;20:485–503. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-0281-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ginhoux F, Guilliams M. Tissue-resident macrophage ontogeny and homeostasis. Immunity. 2016;44:439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bain CC, et al. Long-lived self-renewing bone marrow-derived macrophages displace embryo-derived cells to inhabit adult serous cavities. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:ncomms11852. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loyher PL, et al. Macrophages of distinct origins contribute to tumor development in the lung. J. Exp. Med. 2018;215:2536–2553. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laviron M, Boissonnas A. Ontogeny of tumor-associated macrophages. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1799. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franklin RA, et al. The cellular and molecular origin of tumor-associated macrophages. Science. 2014;344:921–925. doi: 10.1126/science.1252510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu Y, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma originate from embryonic hematopoiesis and promote tumor progression. Immunity. 2017;47:323–338.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Müller A, et al. Resident microglia, and not peripheral macrophages, are the main source of brain tumor mononuclear cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;137:278–288. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hambardzumyan D, Gutmann DH, Kettenmann H. The role of microglia and macrophages in glioma maintenance and progression. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19:20–27. doi: 10.1038/nn.4185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Etzerodt A, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages in omentum promote metastatic spread of ovarian cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2020;217:e20191869. doi: 10.1084/jem.20191869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mantovani A, et al. The chemokine system in cancer biology and therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazzoni M, et al. Senescent thyrocytes and thyroid tumor cells induce M2-like macrophage polarization of human monocytes via a PGE2-dependent mechanism. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;38:208. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1198-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porta C, et al. Tumor-derived prostaglandin E2 promotes p50 NF-κB-dependent differentiation of monocytic MDSCs. Cancer Res. 2020;80:2874–2888. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marigo I, et al. Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression depend on the C/EBPbeta transcription factor. Immunity. 2010;32:790–802. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strauss L, et al. RORC1 regulates tumor-promoting “emergency” granulo-monocytopoiesis. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:253–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mantovani A, et al. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:549–555. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allavena P, et al. The Yin-Yang of tumor-associated macrophages in neoplastic progression and immune surveillance. Immunol. Rev. 2008;222:155–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murray PJ, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mattiola I, et al. The macrophage tetraspan MS4A4A enhances dectin-1-dependent NK cell-mediated resistance to metastasis. Nat. Immunol. 2019;20:1012–1022. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0417-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon SR, et al. PD-1 expression by tumour-associated macrophages inhibits phagocytosis and tumour immunity. Nature. 2017;545:495–499. doi: 10.1038/nature22396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blando J, et al. Comparison of immune infiltrates in melanoma and pancreatic cancer highlights VISTA as a potential target in pancreatic cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:1692–1697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811067116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato S, et al. Expression of TIM3/VISTA checkpoints and the CD68 macrophage-associated marker correlates with anti-PD1/PDL1 resistance: implications of immunogram heterogeneity. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9:1708065. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1708065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walker F, et al. IL6/sIL6R complex contributes to emergency granulopoietic responses in G-CSF- and GM-CSF-deficient mice. Blood. 2008;111:3978–3985. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-119636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borregaard N. Neutrophils, from marrow to microbes. Immunity. 2010;33:657–670. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawrence SM, Corriden R, Nizet V. The ontogeny of a neutrophil: mechanisms of granulopoiesis and homeostasis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol/ Rev. 2018;82:e00057–17. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00057-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:253–268. doi: 10.1038/nri3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coffelt SB, et al. IL-17-producing γδ T cells and neutrophils conspire to promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2015;522:345–348. doi: 10.1038/nature14282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaul ME, Fridlender ZG. Tumour-associated neutrophils in patients with cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019;16:601–620. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mollica Poeta V, et al. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: new targets for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2019;10:379. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raccosta L, et al. The oxysterol-CXCR2 axis plays a key role in the recruitment of tumor-promoting neutrophils. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:1711–1728. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reis ES, et al. Complement in cancer: untangling an intricate relationship. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018;18:5–18. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roumenina LT, et al. Context-dependent roles of complement in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2019;19:698–715. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carnevale S, et al. The complexity of neutrophils in health and disease: focus on cancer. Semin Immunol. 2020;48:101409. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2020.101409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou G, et al. CD177+ neutrophils suppress epithelial cell tumourigenesis in colitis-associated cancer and predict good prognosis in colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2018;39:272–282. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgx142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evrard M, et al. Developmental analysis of bone marrow neutrophils reveals populations specialized in expansion, trafficking, and effector functions. Immunity. 2018;48:364–379.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Condamine T., et al. Lectin-type oxidized LDL receptor-1 distinguishes population of human polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer patients. Sci. Immunol. 1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Zhu YP, et al. Identification of an early unipotent neutrophil progenitor with pro-tumoral activity in mouse and human bone marrow. Cell Rep. 2018;24:2329–2341.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Noman MZ, et al. PD-L1 is a novel direct target of HIF-1α, and its blockade under hypoxia enhanced MDSC-mediated T cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:781–790. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng Y, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts induce PDL1+ neutrophils through the IL6-STAT3 pathway that foster immune suppression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:422. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0458-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lavin Y, et al. Innate immune landscape in early lung adenocarcinoma by paired single-cell analyses. Cell. 2017;169:750–765.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lambrechts D, et al. Phenotype molding of stromal cells in the lung tumor microenvironment. Nat. Med. 2018;24:1277–1289. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zilionis R, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of human and mouse lung cancers reveals conserved myeloid populations across individuals and species. Immunity. 2019;50:1317–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klemm F, et al. Interrogation of the microenvironmental landscape in brain tumors reveals disease-specific alterations of immune cells. Cell. 2020;181:1643–1660. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Friebel E, et al. Single-cell mapping of human brain cancer reveals tumor-specific instruction of tissue-invading leukocytes. Cell. 2020;181:1626–1642. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Azizi E, et al. Single-cell map of diverse immune phenotypes in the breast tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2018;174:1293–1308.e36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Puram SV, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of primary and metastatic tumor ecosystems in head and neck cancer. Cell. 2017;171:1611–1624.e24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tirosh I, et al. Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science. 2016;352:189–196. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chevrier S, et al. An immune atlas of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cell. 2017;169:736–749.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Donadon M, et al. Macrophage morphology correlates with single-cell diversity and prognosis in colorectal liver metastasis. J. Exp. Med. 2020;217:e20191847. doi: 10.1084/jem.20191847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hanna RN, et al. Patrolling monocytes control tumor metastasis to the lung. Science. 2015;350:985–990. doi: 10.1126/science.aac9407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Molgora M, et al. The Yin–Yang of the interaction between myelomonocytic cells and NK cells. Scand. J. Immunol. 2018;88:e12705. doi: 10.1111/sji.12705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Helm O, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages exhibit pro- and anti-inflammatory properties by which they impact on pancreatic tumorigenesis. Int. J. Cancer. 2014;135:843–861. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Canli Ö, et al. Myeloid cell-derived reactive oxygen species induce epithelial mutagenesis. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:869–883.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Joyce JA, Pollard JW. Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:239–252. doi: 10.1038/nrc2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guo X, et al. Single tumor-initiating cells evade immune clearance by recruiting type II macrophages. Genes Dev. 2017;31:247–259. doi: 10.1101/gad.294348.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jinushi M, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages regulate tumorigenicity and anticancer drug responses of cancer stem/initiating cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:12425–12430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106645108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lu H, et al. A breast cancer stem cell niche supported by juxtacrine signalling from monocytes and macrophages. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:1105–1117. doi: 10.1038/ncb3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pastò A, Consonni FM, Sica A. Influence of innate immunity on cancer cell stemness. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:3352. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liguori M, et al. The soluble glycoprotein NMB (GPNMB) produced by macrophages induces cancer stemness and metastasis via CD44 and IL-33. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0501-0.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qian BZ, et al. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature. 2011;475:222–225. doi: 10.1038/nature10138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peinado H, et al. Pre-metastatic niches: organ-specific homes for metastases. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2017;17:302–317. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bosurgi L, et al. Macrophage function in tissue repair and remodeling requires IL-4 or IL-13 with apoptotic cells. Science. 2017;356:1072–1076. doi: 10.1126/science.aai8132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Afik R, et al. Tumor macrophages are pivotal constructors of tumor collagenous matrix. J. Exp. Med. 2016;213:2315–2331. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lewis JS, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor by macrophages is up-regulated in poorly vascularized areas of breast carcinomas. J. Pathol. 2000;192:150–158. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH687>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Leek RD, et al. Association of macrophage infiltration with angiogenesis and prognosis in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4625–4629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lin EY, et al. Macrophages regulate the angiogenic switch in a mouse model of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11238–11246. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Priceman SJ, et al. Targeting distinct tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells by inhibiting CSF-1 receptor: combating tumor evasion of antiangiogenic therapy. Blood. 2010;115:1461–1471. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-237412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stockmann C, et al. Deletion of vascular endothelial growth factor in myeloid cells accelerates tumorigenesis. Nature. 2008;456:814–818. doi: 10.1038/nature07445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.De Palma M, Biziato D, Petrova TV. Microenvironmental regulation of tumour angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2017;17:457–474. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mazzieri R, et al. Targeting the ANG2/TIE2 axis inhibits tumor growth and metastasis by impairing angiogenesis and disabling rebounds of proangiogenic myeloid cells. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:512–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schmittnaegel M, et al. Dual angiopoietin-2 and VEGFA inhibition elicits antitumor immunity that is enhanced by PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9:eaak9670. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aak9670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pan W, et al. The DNA methylcytosine dioxygenase tet2 sustains immunosuppressive function of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells to promote melanoma progression. Immunity. 2017;47:284–297.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Medler TR, et al. Complement C5a fosters squamous carcinogenesis and limits T cell response to chemotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2018;34:561–578.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bonavita E, et al. PTX3 is an extrinsic oncosuppressor regulating complement-dependent inflammation in cancer. Cell. 2015;160:700–714. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rubino M, et al. Epigenetic regulation of the extrinsic oncosuppressor PTX3 gene in inflammation and cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1333215. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1333215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kryczek I, et al. B7-H4 expression identifies a novel suppressive macrophage population in human ovarian carcinoma. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:871–881. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang L, et al. VISTA, a novel mouse Ig superfamily ligand that negatively regulates T cell responses. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:577–592. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ruffell B, Affara NI, Coussens LM. Differential macrophage programming in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mason SD, Joyce JA. Proteolytic networks in cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shojaei F, et al. Role of Bv8 in neutrophil-dependent angiogenesis in a transgenic model of cancer progression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:2640–2645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712185105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wculek SK, Malanchi I. Neutrophils support lung colonization of metastasis-initiating breast cancer cells. Nature. 2015;528:413–417. doi: 10.1038/nature16140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen MB, et al. Inflamed neutrophils sequestered at entrapped tumor cells via chemotactic confinement promote tumor cell extravasation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:7022–7027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715932115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Szczerba BM, et al. Neutrophils escort circulating tumour cells to enable cell cycle progression. Nature. 2019;566:553–557. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0915-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Butin-Israeli V, et al. Neutrophil-induced genomic instability impedes resolution of inflammation and wound healing. J. Clin. Investig. 2019;129:712–726. doi: 10.1172/JCI122085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]