Abstract

This study aimed to explore the effect of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) on bladder smooth muscle cells (BSMCs) under high glucose (HG) treatment in vitro. BSMCs from Sprague–Dawley rat bladders were cultured and passaged in vitro. The third-generation cells were cultured and divided into control group, HG group, HG + CGRP group, HG + CGRP + asiatic acid (AA, p-p38 activator) group, CGRP group, AA group, HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 (CGRP receptor antagonist) group and HG + LY2228820 (p38 MAPK inhibitor) group. The cell viability, apoptosis, malondialdehyde (MDA) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels of BSMCs were observed by the relevant detection kits. The expressions of α-SM-actin, p38 and p-p38 were detected by qRT-PCR or Western blot analysis. Compared with the control group, the cell viability, SOD and α-SM-actin levels of BSMCs were decreased and apoptotic cells, MDA and p-p38 levels were increased after HG treatment, while these changes could be partly reversed when BSMCs were treated with HG and CGRP or LY2228820 together. Moreover, AA or CGRP-8-37 could suppress the effect of CGRP on BSMCs under HG condition. Our data indicate that CGRP protects BSMCs from oxidative stress induced by HG in vitro, and inhibit the α-SM-actin expression decrease through inhibiting the intracellular p38 MAPK signaling pathway.

Subject terms: Cell biology, Drug discovery, Diseases, Medical research

Introduction

Diabetic cystopathy (DCP) is a common urinary complication of diabetes. Even in patients with stable glycemic control, the incidence of DCP is still as high as 25%1. Patients with DCP mainly present with symptoms such as low bladder detrusor contractility and decreased urination sensation, which eventually causes chronic urinary retention and full urinary incontinence2, 3.

The exact pathogenesis of DCP is not fully understood. The etiology research is currently focused on three parties: myogenic factors, neurogenic factors and oxidative stress. Oxidative stress responses induced by hyperglycemia are increasingly becoming the focus of research4–6. The consequence of hyperglycemic stimulation is the increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), thus starting the oxidative stress. These reactive molecules can directly oxidize and damage DNA, proteins and lipids, which can also activate multiple stress-sensitive signaling pathways in cells as signaling molecules7–9. At present, it is believed that oxidative stress causes peripheral autonomic neuropathy and bladder smooth muscle damage, resulting in progressively worsening bladder function10–12. Elrashidy et al. has reported that long-term diabetes caused oxidative stress that could promote the bladder muscle fibrosis and apoptosis11. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is the main constituent neuropeptide of sensory nerves. Our previous studies showed CGRP was down-regulated in DCP, which contributes to the bladder dysfunction13, 14. Other research has also indicated that the content of CGRP in the bladder wall of diabetic rats significantly decreased, suggesting that CGRP plays a key role in the development of DCP15. It is reported that CGRP can decrease the oxidative stress level in rats with severe acute pancreatitis through inhibiting the p38 MAPK pathway activity16. Our previous study also showed that CGRP could decrease the oxidative stress level in dorsal root ganglion neurons under high glucose (HG) treatment in vitro through PI3K/AKT pathway14.

We speculated that CGRP protected bladder smooth muscle cells (BSMCs) from oxidative stress induced by HG in vitro. In the current study, the cell model with diabetes was induced with HG, then the cell viability, apoptosis and α-SM-actin (contractile marker in smooth muscle cells) expression of BSMCs under HG with or without CGRP in vitro were observed, and then asiatic acid (AA, p-p38 activator), CGRP-8-37 (CGRP receptor antagonist) and LY2228820 (p38 MAPK inhibitor) were applied to explore the possible relevant mechanism.

Materials and methods

Animal

The experiment was approved by Ethical Committee on Animal Experiment Committee of Nanjing Medical University (KY-20190643). Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 12, male 6, female 6; 200–220 g, 213.58 ± 5.84 g) were purchased from Nanjing Medical University Animal Experiment Center. All experiments and methods were performed in accordance with the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines17. We declared that all methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Cell culture

The rat bladder smooth muscle cells (BSMCs) were isolated and cultured according to previous studies18–21. Briefly, the rat was anesthetized and the bladder was removed quickly. The bladder was rinsed with 0.01 M sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and minced into 1 mm3 sections, then was incubated with 0.3 mg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 1 mg/ml collagenase I, 0.2 mg/ml elastase III and 2 mg/ml crystallized bovine serum albumin for 1.5 h at 37 ℃. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 5 mM D-glucose (Gibco/BRL), 100 U/ml penicillin, 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. The culture medium was replaced with fresh medium twice a week. The cells were passaged when they had reached 80–90% confluence, and the third- generation cells were used in the following experiments.

Cell treatments

The cell model with diabetes was induced by HG as previously described by Qiu22, 23. Briefly, BSMCs were grown in DMEM supplemented with 5 mM D-glucose (normal glucose as a control), to mimic diabetes in vitro, the cells were maintained in DMEM with 25 mM D-glucose (Gibco/BRL) for 48 h as a HG treatment. BSMCs were divided into 8 groups: control group, HG group, HG + CGRP group, HG + CGRP + AA group, CGRP group, AA group, HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 group and HG + LY2228820 group. The relevant use concentrations were as follows: CGRP (20 pg/ml, Abcam, UK), AA (5 μM, Abcam, UK), CGRP-8-37 (2 μM, Abcam, UK) and LY2228820 (1 μM, Abcam, UK). The cells were incubated in the incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 48 h.

Methyl-thiazole-tetrazolium (MTT) assay

The cell viability of the cultured BSMCs was measured by MTT kit (Amresco, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL)

The apoptosis of BSMCs was measured using TUNEL kit for rats (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Malondialdehyde (MDA) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels

The MDA and SOD levels in BSMCs were detected by MDA kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) and SOD kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) respectively according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunofluorescence

Cell culture medium was replaced with 5% goat serum to block non-specific reaction at room temperature for 30 min and then the cells were incubated with 1:500 diluted rabbit anti-α-SM-actin primary antibody (Abcam, UK) for 6 h at room temperature. Then the cells were washed three times with 0.01 M PBS and incubated with 1:500 diluted Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit second antibody (Abcam, UK) in the dark for 3 h at room temperature. Hoechst33342 was used to stain the cell nuclei in the dark for 0.5 h at room temperature. The α-SM-actin immunopositive cells were observed and photographed with a fluorescent microscope (Leica DMIRB, Germany).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

The qRT-PCR was performed according to previous study24. The Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) was used to extract the total RNA of BSMCs in the four groups. The cDNA was generated with RevertAidTM First Strand cDNA Synthesized Kit (Fermentas, Canada). The PCR analyses were conducted using FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche, Switzerland) on Corbett RG-6000 PCR system (QIAGEN, German). The sense and antisense primers were synthesized as follows: p38 forward 5′-AGGAGAGGCCCACGTTCTAC-3′, reverse 5′-TCAGGCTCTTCCATTCGTCT-3′; α-SM-actin forward 5′-GGAAGACAGCACAGCTCTGG-3′, reverse 5′-CATAGAGGGACAGCACAGCC-3′; GAPDH forward 5′-GCAAGTTCAACGGCACAG-3′, reverse 5′-GCCAGTAGACTCCACGACAT-3′. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The results were calculated with comparative Ct method.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was applied to determine the levels of protein expression in cells according to previous studies25–28. Briefly, the proteins in the four groups were extracted by RIPA buffer (Beyotime, China) and transfected onto the PVDF membranes, then the PVDF membranes were incubated with 1:500 diluted mouse anti-p38 primary antibody (Abcam, UK), 1:500 diluted mouse anti-p-p38 primary antibody (Santa Cruz, USA), 1:500 diluted mouse anti-α-SM-actin primary antibody (Abcam, UK) and 1:1000 diluted rabbit anti-β-actin primary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich Co., USA) overnight at 4 °C. The following day, the membranes were probed with the 1:5000 IRDye diluted 700-conjugated affinity-purified goat anti-mouse second antibody (Rockland Immunochemicals, USA) or 1:5000 diluted IRDye 800-conjugated affinity-purified goat anti-rabbit second antibody (1:5000, Rockland Immunochemicals, USA) for 60 min at room temperature. Then protein bands were visualized using Odyssey laser scanning system (LI-COR Inc., USA) and the intensities were quantified by Odyssey 3.0 image analysis system software.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD). The statistics package for social science 21.0 (SPSS 21.0) was used to do the statistical analysis. The differences among the groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical charts are made with GraghPad Prism 7.0 software. The difference at p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval

The experiment was approved by Ethical Committee on Animal Experiment Committee of Nanjing Medical University.

Results

The cell viability and apoptosis of BSMCs

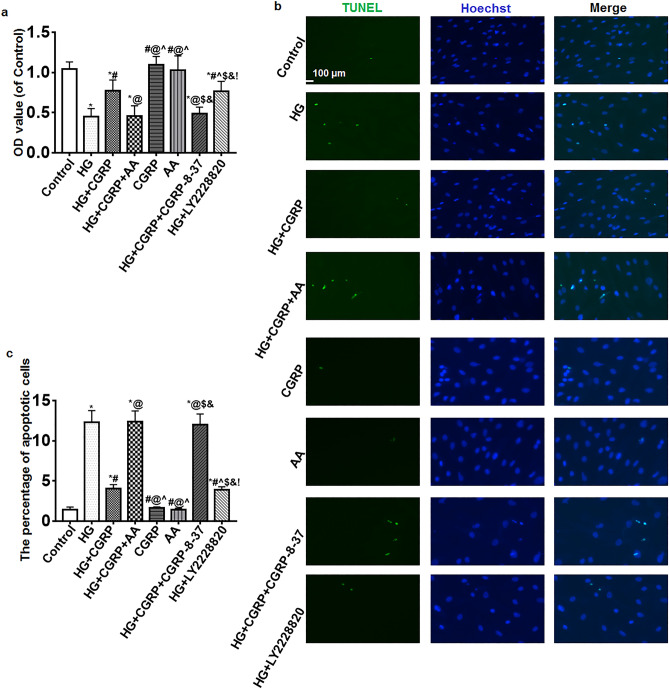

The viability of BSMCs was detected by MTT. Compared with the control, CGRP and AA groups, the OD values of the other groups decreased but the OD values of the HG + CGRP and HG + LY2228820 groups were higher than that in the HG, HG + CGRP + AA and HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 groups (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) The viability of BSMCs was detected by MTT. Compared with the control, CGRP and AA groups, the OD values of the other groups decreased but the OD values of the HG + CGRP and HG + LY2228820 groups were higher than that in the HG, HG + CGRP + AA and HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 groups. (b) TUNEL assay results showed that there were almost no apoptotic cells in the control, CGRP and AA groups. More apoptotic cells were observed in the HGgroup, after CGRP or LY2228820 treatment, the number of apoptotic cells was decreased. AA or CGRP-8-37 reversed the effect of CGRP on the cells. (c) Statistical histogram of the percentage of apoptotic cells in each group. *VS. control group, p < 0.05; # VS. HG group, p < 0.05; @ VS. HG + CGRP group, p < 0.05; ^ VS. HG + CGRP + AA group, p < 0.05; $ VS. CGRP group, p < 0.05; & VS. AA group, p < 0.05; ! VS. HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 group, p < 0.05. Bar = 100 μm. n = 6. The bar charts were created by GraghPad Prism 7.0 software (Version 7.00, URL: www.graphpad.com).

The apoptosis of BSMCs was detected by TUNEL. Results showed that there were almost no apoptotic cells in the control, CGRP and AA groups. More apoptotic cells were observed in the HG group, after CGRP or LY2228820 treatment, the number of apoptotic cells was decreased. AA or CGRP-8-37 reversed the effect of CGRP on the cells. The difference of percentage of apoptotic cells was statistically significant (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1b, c).

Oxidative stress level of BSMCs

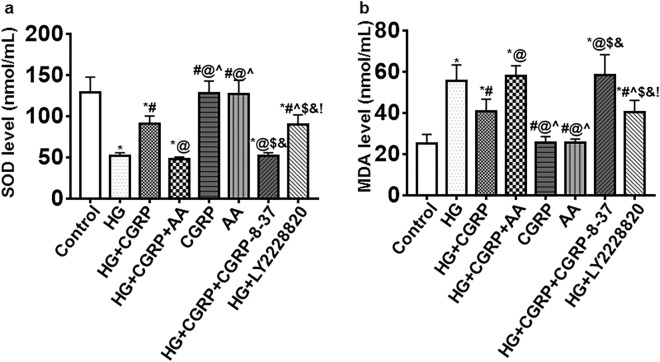

Compared with the control, CGRP and AA groups, the SOD levels in the other groups decreased, but the SOD levels in the HG + CGRP and HG + LY2228820 groups were higher than that in the HG group, HG + CGRP + AA and HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 groups (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

The oxidative stress level of BSMCs was measured by SOD and MDA kits. (a) Compared with the control, CGRP and AA groups, the SOD levels in the other groups decreased, but the SOD levels in the HG + CGRP and HG + LY2228820 groups were higher than that in the HG group, HG + CGRP + AA and HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 groups. (b) Compared with the control, CGRP and AA groups, the MDA level in the other groups increased but the MDA levels in the HG + CGRP and HG + LY2228820group were lower than that in the HG group, HG + CGRP + AA and HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 groups. * VS. control group, p < 0.05; # VS. HG group, p < 0.05; @ VS. HG + CGRP group, p < 0.05; ^ VS. HG + CGRP + AA group, p < 0.05; $ VS. CGRP group, p < 0.05; & VS. AA group, p < 0.05; ! VS. HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 group, p < 0.05. n = 6. The bar charts were created by GraghPad Prism 7.0 software (Version 7.00, URL: www.graphpad.com).

Compared with the control, CGRP and AA groups, the MDA level in the other groups increased but the MDA levels in the HG + CGRP and HG + LY2228820group were lower than that in the HG group, HG + CGRP + AA and HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 groups (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2b).

The expression of α-SM-actin in BSMCs

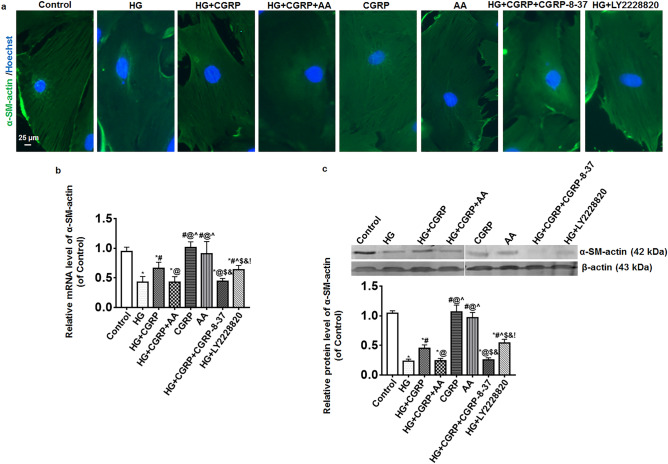

The expression of α-SM-actin in BSMCs was measured by immunofluorescence, qRT-PCR and Western blot. The result of immunofluorescence showed the visible α-SM-actin fibers of BSMCs were found in the control, CGRP, AA, HG + CGRP and HG + LY2228820 groups while they were unclear in the HG, HG + CGRP + AA and HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 groups (Fig. 3a). Compared with the control, CGRP and AA groups, the mRNA expressions of α-SM-actin in the HG group, the HG + CGRP + AA and HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 groups were significantly decreased. Though the expression of α-SM-actin mRNA in the HG + CGRP and HG + LY2228820 groups also deceased, it was higher than that in the HG, HG + CGRP + AA and HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 groups (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3b). The change of the protein expression of α-SM-actin among the groups was similar to that of mRNA (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

The expression of α-SM-actin in BSMCs was measured by immunofluorescence, qRT-PCR and Western blot. (a) The result of immunofluorescence showed the visible α-SM-actin fibers in BSMCs were found in the control, CGRP, AA, HG + CGRP and HG + LY2228820 groups while they were unclear in the HG, HG + CGRP + AA and HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 groups. (b,c) Compared with the control, CGRP and AA groups, the mRNA and protein expressions of α-SM-actin in the HG group, the HG + CGRP + AA and HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 groups were significantly decreased. Though the expression of α-SM-actin mRNA and protein in the HG + CGRP and HG + LY2228820 groups also deceased, it was higher than that in the HG, HG + CGRP + AA and HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 groups. * VS. control group, p < 0.05; # VS. HG group, p < 0.05; @ VS. HG + CGRP group, p < 0.05; ^ VS. HG + CGRP + AA group, p < 0.05; $ VS. CGRP group, p < 0.05; & VS. AA group, p < 0.05; ! VS. HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 group, p < 0.05. Bar = 25 μm. n = 6. The bar charts were created by GraghPad Prism 7.0 software (Version 7.00, URL: www.graphpad.com). The Western blot bands were created by Odyssey 3.0 image analysis system software (Version 1.2.15, URL: www.licor.com/bio/supportsupport).

The expression of p38 MAPK in BSMCs

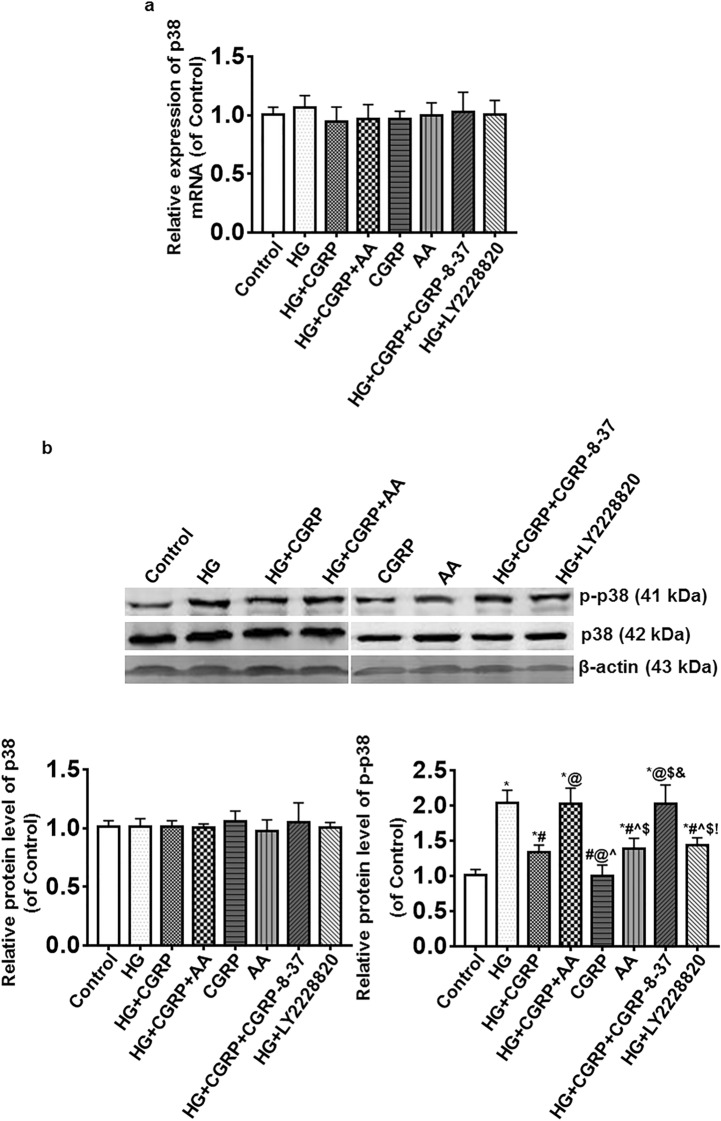

The expressions of p38 mRNA and protein in the groups were no significant changes (p > 0.05). Compared with the control and CGRP groups, the expression of p-p38 protein in the AA group increased. The expression of p-p38 protein in the HG group was notably increased, the degree of the change was reduced when BSMCs were treated with CGRP or LY2228820 at the same time, and AA or CGRP-8-37 could suppress the effect of CGRP on the expression of p-p38 protein in BSMCs under HG (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

The expressions of p38 MAPK in BSMCs were detected by qRT-PCR and Western blot. (a) The expression of p38 mRNA in the groups was no significant change. (b) The expression of p38 protein in the groups was no significant change. Compared with the control and CGRP groups, the expression of p-p38 protein in AA group increased. The expression of p-p38 protein in the HG group was notably increased, the degree of the change was reduced when BSMCs were treated with CGRP or LY2228820 at the same time, and AA or CGRP-8-37 could suppress the effect of CGRP on the expression of p-p38 protein in BSMCs under HG. . * VS. control group, p < 0.05; # VS. HG group, p < 0.05; @ VS. HG + CGRP group, p < 0.05; ^ VS. HG + CGRP + AA group, p < 0.05; $ VS. CGRP group, p < 0.05; & VS. AA group, p < 0.05; ! VS. HG + CGRP + CGRP-8-37 group, p < 0.05. n = 6. The bar charts were created by GraghPad Prism 7.0 software (Version 7.00, URL: www.graphpad.com). The Western blot bands were created by Odyssey 3.0 image analysis system software (Version 1.2.15, URL: www.licor.com/bio/supportsupport).

Discussion

Patients with DCP mainly present low bladder detrusor contractility, however, the effect of hyperglycemia on BSMCs remains largely elusive. To explore the possible related mechanism, the cell model with diabetes was induced with HG in this research according to previous studies22, 23. At the beginning, BSMCs were cultured and passaged in the medium containing 5 mM D-glucose, to mimic diabetes in vitro, and then BSMCs were maintained in the medium with 25 mM D-glucose for 48 h. Results showed that the viability of BSMCs significantly decreased and apoptotic cells became more after HG treatment, at the same time the SOD level decreased and MDA increased. SOD is an important antioxidant enzyme, and its level decreases, suggesting a decline in antioxidant capacity29. MDA is a lipid oxidative damage marker, and its increased level indicates a higher level of oxidative stress30. The above results indicate that the BSMC model with diabetes has been successfully established and HG caused the BSMC damage through oxidative stress.

The α-SM-actin is the main contractile marker of smooth muscle31, 32. The effect of hyperglycemia on the expression of α-SM-actin is still unclear. In this research, the expression of α-SM-actin in BSMC model with diabetes was measured by immunofluorescence, qRT-PCR and Western blot, the results displayed that the expression of α-SM-actin in BSMCs induced by HG significantly decreased, which may attribute to low bladder detrusor contractility in DCP.

It is well known that the MAPK signaling pathway plays an important role in the regulation of cell migration, proliferation and apoptosis, among them, ERK1/2 cascades are mostly activated for cell growth factor-stimulated signaling, whereas JNK and p38 MAPK process cell stress evoked by physical, chemical and biological stress stimuli33, 34. Our results showed that p-p38 protein level was dramatically increased in BSMCs of HG group and p38 MAPK inhibitor LY2228820 could reduce the change, which suggests that p38 MAPK signaling pathway is involved in BSMC damage through oxidative stress. Many studies have shown that diabetes can cause a decrease in CGRP, CGRP declines in the state of hyperglycemia, causing strong and long-lasting contraction of blood vessels, resulting in vascular endothelial damage, microcirculation disorders, tissue ischemia and hypoxia, which contribute to various diabetes complications, and many agents targeting the CGRP system are in clinical trials35–38. CGRP are the main transmitters affiliated with bladder sensory nerves—specifically, the content of CGRP in the bladder wall of diabetic rats, especially in the submucosal plexus, and the CGRP nerve distribution significantly decreased, suggesting that CGRP plays a key role in the development of DCP15. Some studies show CGRP protects cells or animals from oxidative stress through the MAPK signaling pathway39–42. In the current study, after BSMC model with diabetes induced by HG was treated with CGRP or LY2228820, the cell viability and α-SM-actin expression increased, and apoptosis, oxidative stress and p-p38 protein level decreased. These results indicate that CGRP protects BSMCs from oxidative stress through inhibiting p38 MAPK signaling pathway, and to further verify it, the BSMC model with diabetes was treated by CGRP and p-p38 activator or CGRP receptor antagonist together, and AA or CGRP-8-37 could suppress the protective effect of CGRP.

Conclusions

CGRP protects BSMCs under HG condition in vitro from oxidative stress, and inhibit the α-SM-actin expression decrease through inhibiting the intracellular p38 MAPK signaling pathway.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Z.W designed the study. J.X, Y.L, S.Z performed the experiment. L.D, B.S, Y.S performed the data analyses. J.X and Z.W wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81400758); Six top talent fund of Jiangsu Province (No. 2014-wsw-12); Nanjing Medical Science and Technology Development Project (No. YKK17210).

Data availability

The primary data are available in the “Supplementary Material”.

Code availability

N/A.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-87140-y.

References

- 1.Yuan Z, Tang Z, He C, Tang W. Diabetic cystopathy: a review. J. Diabetes. 2015;7:442–447. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burakgazi AZ, Alsowaity B, Burakgazi ZA, Unal D, Kelly JJ. Bladder dysfunction in peripheral neuropathies. Muscle Nerve. 2012;45:2–8. doi: 10.1002/mus.22178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshimura N, Chancellor MB, Andersson KE, Christ GJ. Recent advances in understanding the biology of diabetes-associated bladder complications and novel therapy. BJU Int. 2005;95:733–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das P, Biswas S, Mukherjee S, Bandyopadhyay SK. Association of oxidative stress and obesity with insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mymensingh Med. J. 2016;25:148–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poblete-Aro C, Russell-Guzman J, Parra P, Soto-Munoz M, Villegas-Gonzalez B, Cofre-Bolados C, Herrera-Valenzuela T. Exercise and oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Rev. Med. Chil. 2018;146:362–372. doi: 10.4067/s0034-98872018000300362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reus GZ, Carlessi AS, Silva RH, Ceretta LB, Quevedo J. Relationship of oxidative stress as a link between diabetes mellitus and major depressive disorder. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019;2019:8637970. doi: 10.1155/2019/8637970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ighodaro OM. Molecular pathways associated with oxidative stress in diabetes mellitus. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;108:656–662. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rehman K, Akash MSH. Mechanism of generation of oxidative stress and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus: how are they interlinked? J. Cell. Biochem. 2017;118:3577–3585. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thakur P, Kumar A, Kumar A. Targeting oxidative stress through antioxidants in diabetes mellitus. J. Drug Target. 2018;26:766–776. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2017.1419478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersson KE. Oxidative stress and its possible relation to lower urinary tract functional pathology. BJU Int. 2018;121:527–533. doi: 10.1111/bju.14063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elrashidy RA, Liu G. Long-term diabetes causes molecular alterations related to fibrosis and apoptosis in rat urinary bladder. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2019;111:104304. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2019.104304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsounapi P, Honda M, Hikita K, Sofikitis N, Takenaka A. Oxidative stress alterations in the bladder of a short-period type 2 diabetes rat model: antioxidant treatment can be beneficial for the bladder. In Vivo. 2019;33:1819–1826. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding L, Song T, Yi C, Huang Y, Yu W, Ling L, Dai Y, Wei Z. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) improves the diabetic cytopathy (DCP) via up-regulation of CGRP and cAMP. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e57477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y, Zhang S, Xue J, Wei Z, Ao P, Shen B, Ding L. CGRP Reduces apoptosis of DRG cells induced by high-glucose oxidative stress injury through PI3K/AKT induction of heme oxygenase-1 and Nrf-2 expression. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019;2019:2053149. doi: 10.1155/2019/2053149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langdale CL, Thor KB, Marson L, Burgard EC. Maintenance of bladder innervation in diabetes: a stereological study of streptozotocin-treated female rats. Auton. Neurosci. Basic. 2014;185:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu SH, Guang Y, Wang WX. Protective effects of calcitonin gene-related peptide-mediated p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway on severe acute pancreatitis in rats. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019;64:447–455. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kropp BP, Zhang Y, Tomasek JJ, Cowan R, Furness PD, 3rd, Vaughan MB, Parizi M, Cheng EY. Characterization of cultured bladder smooth muscle cells: assessment of in vitro contractility. J. Urol. 1999;162:1779–1784. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)68237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin L, Dai SD, Fan GY. Glucocorticoid-induced differentiation of primary cultured bone marrow mesenchymal cells into adipocytes is antagonized by exogenous Runx2. APMIS. 2010;118:595–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2010.02634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park JM, Adam RM, Peters CA, Guthrie PD, Sun Z, Klagsbrun M, Freeman MR. AP-1 mediates stretch-induced expression of HB-EGF in bladder smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:C294–301. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.2.C294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu X, Cubeddu LX, Malave A. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in primary culture of rat bladder smooth muscle cells by plasma from cyclophosphamide-treated rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;416:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00846-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiu AW, Bian Z, Mao PA, Liu QH. IL-17A exacerbates diabetic retinopathy by impairing Muller cell function via Act1 signaling. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016;48:e280. doi: 10.1038/emm.2016.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiu AW, Liu QH, Wang JL. Blocking IL-17A alleviates diabetic retinopathy in rodents. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017;41:960–972. doi: 10.1159/000460514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H, Jin G, Zhu P, Zou L, Shi J, Yi X, Zhang X, Tian M, Qin J. Upregulation of Lhx8 increase VAChT expression and ACh release in neuronal cell line SHSY5Y. Neurosci. Lett. 2014;559:184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balkir L, Tourkova IL, Makarenkova VP, Shurin GV, Robbins PD, Yin XM, Chatta G, Shurin MR. Comparative analysis of dendritic cells transduced with different anti-apoptotic molecules: sensitivity to tumor-induced apoptosis. J. Gene Med. 2004;6:537–544. doi: 10.1002/jgm.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu JH, Liu YQ, Deng QW, Peng YP, Qiu YH. Dopamine D2 receptor is involved in alleviation of type II collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015;2015:496759. doi: 10.1155/2015/496759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao XY, Cui SW, Wang XQ, Peng YP, Qiu YH. Tyrosine hydroxylase expression in CD4(+) T cells is associated with joint inflammatory alleviation in collagen type II-induced arthritis. Rheumatol. Int. 2013;33:2597–2605. doi: 10.1007/s00296-013-2788-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimmermann D, Homa KE, Hocky GM, Pollard LW, De La Cruz EM, Voth GA, Trybus KM, Kovar DR. Mechanoregulated inhibition of formin facilitates contractile actomyosin ring assembly. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:703. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00445-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu F, Liu R, Shen X, Xu H, Sheng L. Study on the interaction and antioxidant activity of theophylline and theobromine with SOD by spectra and calculation. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019;215:354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsikas D. Assessment of lipid peroxidation by measuring malondialdehyde (MDA) and relatives in biological samples: analytical and biological challenges. Anal. Biochem. 2017;524:13–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karoor V, Fini MA, Loomis Z, Sullivan T, Hersh LB, Gerasimovskaya E, Irwin D, Dempsey EC. Sustained activation of rho GTPases promotes a synthetic pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell phenotype in neprilysin null mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018;38:154–163. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.310207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L, Zhang Y, Wu Y, Yu J, Zhang Y, Zeng F, Shi L. Role of the balance of Akt and MAPK pathways in the exercise-regulated phenotype switching in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019 doi: 10.3390/ijms20225690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun Y, Liu WZ, Liu T, Feng X, Yang N, Zhou HF. Signaling pathway of MAPK/ERK in cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, senescence and apoptosis. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 2015;35:600–604. doi: 10.3109/10799893.2015.1030412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yue J, Lopez JM. Understanding MAPK signaling pathways in apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020 doi: 10.3390/ijms21072346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Enriquez-Perez IA, Galindo-Ordonez KE, Pantoja-Ortiz CE, Martinez-Martinez A, Acosta-Gonzalez RI, Munoz-Islas E, Jimenez-Andrade JM. Streptozocin-induced type-1 diabetes mellitus results in decreased density of CGRP sensory and TH sympathetic nerve fibers that are positively correlated with bone loss at the mouse femoral neck. Neurosci. Lett. 2017;655:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hay DL, Garelja ML, Poyner DR, Walker CS. Update on the pharmacology of calcitonin/CGRP family of peptides: IUPHAR Review 25. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018;175:3–17. doi: 10.1111/bph.14075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang NW, Wei HX, Wu WF, Lin PM, Chen Y, Liu ZW, Wang HL, Bian YZ, Yu K, Lin S, 2019. Effect of ropivacaine on peripheral neuropathy in streptozocin diabetes-induced rats through TRPV1-CGRP pathway. Bioscience Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Zheng LR, Zhang YY, Han J, Sun ZW, Zhou SX, Zhao WT, Wang LH. Nerve growth factor rescues diabetic mice heart after ischemia/reperfusion injury via up-regulation of the TRPV1 receptor. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2015;29:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaeffer C, Vandroux D, Thomassin L, Athias P, Rochette L, Connat JL. Calcitonin gene-related peptide partly protects cultured smooth muscle cells from apoptosis induced by an oxidative stress via activation of ERK1/2 MAPK. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1643:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Umoh NA, Walker RK, Millis RM, Al-Rubaiee M, Gangula PR, Haddad GE. Calcitonin gene-related peptide regulates cardiomyocyte survival through regulation of oxidative stress by PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways. Ann. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2014;2:1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang SI, Yuan Y, Jiao S, Luo QI, Yu J. Calcitonin gene-related peptide protects rats from cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury via a mechanism of action in the MAPK pathway. Biomed. Rep. 2016;4:699–703. doi: 10.3892/br.2016.658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou Y, Zhang M, Sun GY, Liu YP, Ran WZ, Peng L, Guan CX. Calcitonin gene-related peptide promotes the wound healing of human bronchial epithelial cells via PKC and MAPK pathways. Regul. Pept. 2013;184:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Zhang NW, Wei HX, Wu WF, Lin PM, Chen Y, Liu ZW, Wang HL, Bian YZ, Yu K, Lin S, 2019. Effect of ropivacaine on peripheral neuropathy in streptozocin diabetes-induced rats through TRPV1-CGRP pathway. Bioscience Rep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The primary data are available in the “Supplementary Material”.

N/A.