Abstract

The modulation and selectivity mechanisms of seven mixed-action kappa opioid receptor (KOR)/mu opioid receptor (MOR) bitopic modulators were explored. Molecular modeling results indicated that the ‘message’ moiety of seven bitopic modulators shared the same binding mode with the orthosteric site of the KOR and MOR, whereas the ‘address’ moiety bound with different subdomains of the allosteric site of the KOR and MOR. The ‘address’ moiety of seven bitopic modulators bound to different subdomains of the allosteric site of the KOR and MOR may exhibit distinguishable allosteric modulations to the binding affinity and/or efficacy of the ‘message’ moiety. Moreover, the 3-hydroxy group on the phenolic moiety of the seven bitopic modulators induced selectivity to the KOR over the MOR.

Keywords: : allosteric modulation mechanism, kappa opioid receptor (KOR)/mu opioid receptor (MOR), mixed-action KOR/MOR ligand, molecular dynamics simulations, psychostimulant abuse and addiction, selectivity

The increasingly widespread use of cocaine and other psychostimulants, such as methamphetamine, in the United States makes stimulant use disorders a major public health problem. According to the latest statistics released by the National Survey on Drug Use and Health in 2018, about 5.5 million Americans over the age of 12 admitted to using cocaine in their lifetimes, and approximately 1.9 million Americans aged 12 or older were past-year methamphetamine users [1]. Both cocaine and methamphetamine are CNS and PNS stimulants [2–4]. Their use may cause high levels of dopamine to be released into the CNS and make people feel intense euphoria and a short-term boost in energy. However, both cocaine and methamphetamine are highly addictive stimulants [5]. Long-term and frequent use of cocaine and methamphetamine may cause the CNS to adapt and increase the risk of developing psychostimulant addiction [6,7].

Kappa opioid receptor (KOR) plays a critical role in regulation of addictive behaviors. It is a promising target in the treatment of drug abuse and addiction [8]. KOR and its endogenous opioid peptides, dynorphins, play important roles in modulating the release of dopamine in the reward circuitry in the CNS [9]. Dynorphins exhibit an inverse effect on dopamine compared with psychostimulants [10]. Accumulating evidence has indicated that KOR agonists may efficiently attenuate the behavioral effects of psychostimulants [11–13]. For example, cocaine-induced hyperactivity and behavioral sensitization are effectively attenuated by the KOR agonist Mesyl Sal B in rodents [14]. Unfortunately, activation of the KOR by KOR agonists may also induce undesirable side effects (e.g., depression and aversion) [15–17]. Consequently, clinical development of KOR agonists for treatment of psychostimulant abuse and addiction has not been successful. Thus, development of novel KOR agonists with fewer unwanted side effects to treat cocaine and other psychostimulant abuse and addiction is still an unmet medical need.

It is reported that mu opioid receptor (MOR) and KOR agonists mediate opposite effects on dopamine release [18]. Activating the KOR or antagonizing the MOR may induce depression, whereas activation of the MOR by partial agonists may cause euphoria and sedation [19,20]. In fact, a trade-off of adverse effects caused by a ligand carrying both KOR agonism and MOR partial agonism may lead to an effective and desired balance in therapeutic outcome. For example, Greedy et al. reported that orvinol derivatives with mixed KOR agonist and MOR partial agonist activities may be considered potential therapies for treating cocaine abuse [21]. Therefore, design and development of a KOR agonist with a certain degree of MOR efficacy may be a potential pharmacotherapy approach for the treatment of cocaine and other psychostimulant abuse with fewer side effects.

Three reported compounds, β-funaltrexamine (β-FNA), nalfurafine (NFF) and 42B (Figure 1 & Supplementary Figure 1), are representative ligands with mixed-action KOR and MOR activities [4,22–24]. β-FNA is one of the most well-known derivatives of β-naltrexamine and acts as an irreversible MOR antagonist and a KOR full agonist [25]. Using protein chemistry and site-directed mutagenesis methods, Chen et al. determined that β-FNA formed a covalent bond with K5.39 of the MOR, which was confirmed in the crystal structure of the inactive MOR co-crystallized with β-FNA [26]. In the crystal structure, the β-carbon of the double bond in the fumarate of β-FNA was demonstrated to form a covalent bond with the ε-amino of K5.39 [27]. In addition, β-FNA acted as a high-efficacy KOR agonist. From the binding assay, β-FNA showed no significant selectivity for the MOR over the KOR (Ki MOR/KOR ≈ 0.16) (Table 1) [28,29]. NFF is a derivative of naltrexone developed in Japan in 2009 [30]. In 2015, NFF was approved to treat pruritus in Japan and is the first and only clinically approved KOR agonist at present [31]. Moreover, NFF acts as a selective KOR full agonist and a MOR partial agonist [32–34]. It also exhibits high effectiveness in suppressing drug abuse and addiction in animal models [35,36]. For example, behavioral effects of cocaine can be significantly attenuated by low doses of NFF in rodents [35–38]. As shown in Table 1, the binding affinity of NFF for the KOR is not significantly different from that for the MOR [36,39]. Removing the 3-hydroxy group of NFF produces compound 42B. Similar to NFF, 42B exhibits full agonist activity at the KOR but only partial agonist activity at the MOR. By contrast, 42B shows a 60-fold higher selectivity for the KOR (Ki = 2.8 nM) over the MOR (Ki = 169.0 nM) [23].

Figure 1. . Chemical structures of β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP with atom notations.

The ‘message’ moiety, linker and ‘address’ moiety in the structures are colored red, blue and magenta, respectively.

β-FNA: β-funaltrexamine; NFF: Nalfurafine.

Table 1. . Binding affinities and efficacies of β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP.

| Compound | Ki (nM) | Ki ratio |

[35S]-GTPγS binding | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOR | KOR | MOR/KOR | MOR | KOR | |||

| EC50 (nM) | Stimulation (%) | EC50 (nM) | Stimulation (%) | ||||

| β-FNA | 2.20† | 14.0† | 0.16 | 3.10 ± 1.30‡ | 19.0 ± 1.00‡ | 5.10 ± 1.40‡ | 78.0 ± 9.00‡ |

| NFF | 0.58§ | 0.20§ | 2.60 | 3.11 ± 0.63¶ | 73.88 ± 2.93¶ | 0.10 ± 0.02¶ | 90.90 ± 3.25¶ |

| 42B | 169.0§ | 2.82§ | 59.80 | 214.90 ± 0.39¶ | 48.87 ± 2.45¶ | 25.56 ± 1.50¶ | 91.34 ± 1.15¶ |

| NBP | 0.63 | 0.18 | 3.50 | 0.42 ± 0.05 | 61.29 ± 1.11 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 98.76 ± 1.52 |

| 3-dHNBP | 24.51 | 7.44 | 3.29 | 290.90 ± 41.99 | 33.62 ± 3.92 | 81.88 ± 9.09 | 99.27 ± 2.79 |

| NCP | 1.25 | 0.13 | 9.62 | 1.82 ± 0.28 | 58.14 ± 1.48 | 0.28 ± 0.03 | 97.14 ± 1.50 |

| 3-dHNCP | 58.27 | 6.13 | 9.51 | 338.43 ± 31.1 | 26.48 ± 3.73 | 92.0 ± 8.47 | 100.20 ± 2.37 |

Analyzing the chemical structures of β-FNA, NFF and 42B (Figure 1), it is apparent that all three compounds are epoxymorphinan derivatives. They possess very similar ‘message’ moieties (the epoxymorphinan scaffold) but relatively different ‘address’ moieties, which are connected to the ‘message’ moiety by an acrylamide linker. Therefore, it is intriguing how their insignificant structural differences affect their selectivity and efficacy profiles with regard to the KOR and MOR. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the only difference in structure between NFF and 42B is the 3-hydroxy group on the phenolic moiety. Both function as KOR full agonists and MOR partial agonists. However, NFF and 42B display different selectivity profiles with regard to the KOR and MOR. To gain further insight into how the 3-hydroxy group on the epoxymorphinan scaffold may induce different selectivity profiles regarding the KOR and MOR, the study was extended to two other pairs of compounds – NBP and its 3-dehydroxy derivative, 3-dehydroxy-NBP (3-dHNBP), and NCP and its 3-dehydroxy derivative, 3-dehydroxy-NCP (3-dHNCP) (Figure 1) – from the authors' opioid ligand library. Similar to NFF and 42B, these two pairs of compounds also possess three parts: a ‘message’ moiety, an ‘address’ moiety and a linker between the ‘message’ moiety and ‘address’ moiety. Notably, the linker of NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP is relatively shorter than that of NFF and 42B. Based on the binding and functional assay (Table 1), none of them showed significant selectivity for the KOR and MOR compared with 42B. By contrast, they all acted as mixed-action KOR full agonists and MOR partial agonists at significantly different potency levels.

It is well known that the KOR and MOR are two critical members of opioid receptors [40] and possess two main types of binding sites for their ligands [41,42]. One is the primary binding site, also known as the orthosteric site, predominantly targeted by orthosteric ligands [43], such as morphine (MOR agonist) [44], naltrexone (MOR antagonist) [45] and salvinorin A (KOR agonist) [46]. Because of the high degree of sequence homology among opioid receptors, especially within their orthosteric sites, orthosteric ligands may not possess the desired selectivity among the receptors. The other binding site of an opioid receptor is the allosteric site [47], which is topographically distinct from the orthosteric site and may be targeted by allosteric modulators. Allosteric modulators often exhibit high subtype selectivity due to the high sequence divergence within the allosteric sites among opioid receptors. Notably, it is reported that allosteric modulators exhibit the potential to modulate the potency and/or efficacy of orthosteric ligands [48,49].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation can conduct all-atom simulation of the biomolecular system and provide detailed information regarding protein structure and dynamics, and with the rapid improvement in computer power and computational techniques, MD simulations have become the most commonly used method to study the protein allostery [50–55]. Subsequent simulation-based analyses (e.g., decomposing polar and nonpolar interaction into residue–ligand pairs by molecular mechanics/generalized born surface area [MM/GBSA]) and key distance, angle and dihedral angle analyses may help to collect information from the trajectories produced by MD simulations and further identify conformational change related to mechanisms of protein allosteric modulations. For example, in the authors' recent molecular modeling studies on the opioid ligands developed based on the ‘message–address’ concept, results of the binding free energy calculation, energy decomposition analyses and distance analyses indicated that their ‘message’ moiety bound with the orthosteric site and their ‘address’ moiety might interact with the allosteric site. The ‘address’ moiety may bind to different subdomains of the allosteric site of opioid receptors and exhibit allosteric modulations distinguishable from the binding affinity and/or efficacy of the ‘message’ moiety [56,57]. Ligands that include the features of both an orthosteric ligand and an allosteric modulator and have unique pharmacological profiles are typically defined as bitopic modulators [58].

In the present work, multiple molecular modeling methods, including molecular docking, MD simulation, free energy calculation and energy decomposition analyses, have been applied to understand the binding modes of seven mixed-action KOR/MOR ligands (i.e., β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP) in the MOR and KOR. The allosteric modulatory mechanisms of their ‘address’ moieties to their efficacy and receptor selectivity have been explored. Furthermore, through comparison of three pairs of compounds (i.e., NFF vs 42B, NBP vs 3-dHNBP, NCP vs 3-dHNCP), the effects of the 3-hydroxy group on their binding affinity and selectivity profiles have been disclosed. These results provide insight into the structure–function relationship of these ligands and may help design and develop novel mixed-action KOR/MOR bitopic modulators to potentially treat psychostimulant abuse and addiction with fewer side effects.

Methods

Biological data in Table 1 were collected following the same or similar methods and protocols previously reported [50].

Molecular docking studies

As per the results of the [35S]-GTPγS functional assays displayed in Table 1, β-FNA was identified as a mixed KOR partial agonist and MOR antagonist [4,24]. NFF, 42B, NBP and NCP functioned as mixed KOR full agonists and MOR partial agonists with moderate efficacy [23,39,59]. NBP's 3-dehydroxy derivative, 3-dHNBP, and NCP's 3-dehydroxy derivative, 3-dHNCP, were identified as mixed KOR full agonists and MOR partial agonists with low efficacy. Thus, the crystal structures of agonist-bound KOR (Protein Data Bank identifier [PDB ID]: 6B73) [60], antagonist-bound MOR (PDB ID: 4DKL) [27] and agonist-bound MOR (PDB ID: 5C1M) [61] downloaded from www.rcsb.org were used to form the protein templates. Except for the monomer of the KOR and MOR, other components of the three crystal structures were first removed. Next, the missing residues in extracellular loop 2 (ECL-2) and intracellular loop 3 (ICL-3) of 6B73 and the missing residues in ICL-3 of 4DKL were modeled and implemented through Sybyl 8.0 (Tripos, MO, USA). Finally, the missing hydrogen atoms were added to the three proteins to complete the preparation of the receptors. In addition, β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP were sketched in Sybyl 8.0 (Tripos) and assigned Gasteiger-Hückel charges. Afterward, the seven ligands were further energy minimized to a gradient of 0.05 with 10,000 iterations in Sybyl 8.0 (Tripos).

The molecular docking study was conducted using GOLD 5.6 (Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge, UK) to obtain the ligand–receptor complex. As described in studies of the crystal structures of the KOR and MOR [27,60–62], ionic interactions were formed between D3.32 of the KOR and MOR and the original ligands, MP1104, JDTic, β-FNA and BU72. In addition, hydrogen bonding interactions were formed between Y3.33 of the KOR and MOR and the three original ligands, MP1104, β-FNA and BU72. Hence, similar to the docking process of previous studies [50,51], in the present docking process, the binding sites of the KOR and MOR were defined by the atoms within 10 Å of the γ-carbon atom of D3.32 in the KOR and MOR. The distances between the oxygen atom at the side chain of D3.32 in the KOR and MOR and the protonated nitrogen atom at the 17-amino group of the seven ligands were restricted to 4.0 Å. The distances between the phenolic oxygen atom of Y3.33 and the dihydrofuran oxygen atom of the ligands were restricted to 3.5 Å. It should be noted that there is a covalent bond between the ε-amino group of K5.39 and the β-carbon atom of the double bond in the fumarate of β-FNA in the crystal structure of the antagonist-bound MOR (PDB ID: 4DKL) [27]. Thus, the distance between the nitrogen atom of the ε-amino group of K5.39 and the β-carbon atom of the double bond in the fumarate in β-FNA was restricted to 1.52 Å when β-FNA was docked back into the inactive MOR and the active KOR. Except for the aforementioned parameters, molecular docking studies were conducted with standard default settings. The docking solutions with the highest ChemPLP score among the 50 solutions were chosen to merge into their respective receptors as the optimal docking poses and named β-FNA_MORinactive, β-FNA_KORactive, NFF_MORactive, NFF_KORactive, 42B_MORactive, 42B_KORactive, NBP_MORactive, NBP_KORactive, 3-dHNBP_MORinactive, 3-dHNBP_KORactive, NCP_MORactive, NCP_KORactive, 3-dHNCP_MORinactive and 3-dHNCP_KORactive complexes.

Building the membrane system to the ligand–receptor complexes

As we know, KOR and MOR are members of membrane proteins. Thus, simulating the β-FNA_MORinactive, β-FNA_KORactive, NFF_MORactive, NFF_KORactive, 42B_MORactive, 42B_KORactive, NBP_MORactive, NBP_KORactive, 3-dHNBP_MORinactive, 3-dHNBP_KORactive, NCP_MORactive, NCP_KORactive, 3-dHNCP_MORinactive and 3-dHNCP_KORactive complexes requires them to be in a membrane-aqueous system. In the present study, the CHARMM-GUI website service was applied to build the membrane-aqueous systems for the 14 ligand–receptor complexes from the molecular docking studies [63,64]. First, the ligand–receptor complex was uploaded to the website service, and a disulfide bridge was added between C3.25 and CECL2 of the KOR and MOR. Since the coordinates of the inactive MOR and active KOR were different from that of their crystal structures as a result of adding the missing residues to ICL-3 of 4DKL and ECL-2 and ICL-3 of 6B73, the protein orientation options including the Orientations of Proteins in Membranes database [65] and aligning the first principal axis along the z-axis were compared in advance (NFF_KORactive and 42B_KORactive complexes were selected as the representatives; Supplementary Table 1). In addition, as the protein area of the ligand–receptor complex in the present study was larger than that of the crystal structures of the KOR and MOR, in the second step, aligning the first principal axis along the z-axis that may form a larger system size was applied to orient the ligand–receptor complex. Third, as 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylphosphatidylcholine (POPC) has the potential to form a bilayer secondary structure and a simple structure and is easily modeled, the POPC lipid bilayer is one of the most widely used single-species lipid bilayers for in silico simulations [66,67]. Thus, the ligand–receptor complex was inserted into the POPC homogeneous lipid (approximately 80 POPC molecules at the upper and lower leaflets, respectively). In addition, sodium and chloride ions were added using the Monte Carlo ion replacement method to make the concentration of NaCl approximately 0.15 M [68]. Fourth, the system from the third step was solved with the TIP3P water model in a rectangular box. Finally, the system, including the ligand–receptor complex, POPC lipid membrane, ions and TIP3P water molecules (Supplementary Figure 2), was generated as the starting structure to conduct the following MD simulations. The average system size was approximately 75,000 atoms.

MD simulations

Before the MM minimizations and MD simulations, the hydrogen atoms of the KOR and MOR were first added using the tleap program of AMBER 14 [69]. Second, the geometries of β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP were optimized using Hartree–Fock/6-31G * in Gaussian 03 in advance [70]. The partial charges (restrained electrostatic potential) and force field parameters of the seven ligands were formed using the antechamber program in AMBER 14 [71]. Third, the charmmlipid2amber.py script of AMBER 14 was applied to convert the format of the POPC lipid bilayer to be recognized by LEaP and Lipid14 [69]. Additionally, the general AMBER force field (gaff) [71], the standard AMBER force field (ff12SB) [72] and the AMBER lipid force field (lipid14) [73] were used to describe the parameters of ligands, proteins and lipid membrane, respectively.

The program PMEMD.cuda in AMBER 14 was applied to perform MD simulations [69,74]. Before MD simulations, a three-step energy minimization on the 14 systems was conducted using the sander program in AMBER 14, first restricting the ligand–receptor complex and the lipid molecules to minimize the water molecules and ions, then restricting the backbone atoms of the protein and ligand to minimize the side chain of the protein, lipid molecules, water molecules and ions, and finally using no restriction to minimize the whole system. Each step first ran 3000 cycles of steepest descent, followed by 3000 cycles of conjugate gradient minimizations. After this, each system was heated through seven steps in two ensembles, NVT and NPT: two steps in the NVT ensemble (constant volume and temperature) from 0 to 100 K and five steps in the NPT ensemble (constant pressure and temperature) from 100 to 310 K. The total time of the seven heating steps was 3.5 ns (0–50 K, 0.5 ns; 50–100 K, 0.5 ns; 100–150 K, 0.5 ns; 150–200 K, 0.5 ns; 200–250 K, 0.5 ns; 250–300 K, 0.5 ns; 300–310 K, 0.5 ns). After the heating process, 100 ns MD simulations were performed. In the process of performing the MD simulations, the NPT ensemble (P = 105 Pa; T = 310 K) and periodic boundary conditions were applied. Langevin thermostat was applied to control the temperature. The integration time step was set at 2 fs. The cutoff of the nonbonded van der Waals interactions was set at 10 Å. The snapshots were saved every 10 ps. The particle mesh Ewald method was applied to compute the long-range electrostatic interactions [75]. In the present study, three independent 100 ns MD simulations were conducted for each system to ensure that 100 ns MD simulations were enough for each system to achieve stability. Each MD simulation for the same system applied the same initial starting structures but different initial velocities. After analyzing the equilibrium of the three independent MD simulations on each system (Supplementary Figure 3 & Supplementary Table 2), the independent MD simulation of each system with the most stable root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) value was chosen as the representative independent MD simulation for each system and used to conduct the subsequent analysis. In addition, since KOR and MOR are transmembrane proteins and the 14 ligand–receptor complexes were inserted into the POPC bilayer membrane to perform MD simulations, membrane equilibration was important to the stability of the 14 systems [76,77]. Thus, the NFF_KORactive and 42B_KORactive systems were selected as representatives to calculate the area per lipid value to evaluate membrane equilibration (Supplementary Figure 4) by MEMBPLUGIN in Visual Molecular Dynamics [78].

Analyses of data from MD simulations

The MM/GBSA method was applied to compute the binding free energies and decompose the binding free energies into individual energy components. The energy calculation and decomposition were based on the following equation [79]:

| (Eq. 1) |

In Equation 1, ΔEMM represents the change in interaction energy between ligand and receptor in a vacuum, including the internal bonded energy (ΔEinter), van der Waals energy (ΔEvdw) and electrostatic energy (ΔEele). ΔGGB and ΔGSA represent changes in the polar and nonpolar desolvation free energies, respectively. TΔS represents the change in the conformational entropy at temperature T. During the binding free energy calculation, the GB and Laboratoire de Chimie des Polymères Organiques methods were applied to calculate the polar (ΔGGB) and nonpolar (ΔGSA) desolvation free energy, respectively [80]. In addition, there are about 75,000 atoms in each system, and considering the large amount of computational resources required to calculate the conformational entropy for such large systems, the change in conformational entropy contribution (TΔS) was not calculated in the present work.

After obtaining the binding free energy, to quantitatively evaluate the energy contribution of each residue to the binding of ligands with the receptor, the binding free energy, van der Waals energy (ΔEvdw), electrostatic energy (ΔEele) and polar and nonpolar desolvation free energies (ΔGGB and ΔGSA) were respectively decomposed into ligand–residue pairs using the mm_gbsa and sander programs in AMBER 14 [81,82].

Results & discussion

Optimal docking poses from molecular docking studies

In the docking study, β-FNA, 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP were docked into the crystal structure of antagonist-bound MOR (PDB ID: 4DKL) [27]. NFF, 42B, NBP and NCP were docked into the crystal structure of agonist-bound MOR (PDB ID: 5C1M) [61]. β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, NCP, 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP were docked into the crystal structure of agonist-bound KOR (PDB ID: 6B73) [60]. According to the reported crystal structures of MOR, KOR and delta opioid receptor and the authors' previous molecular modeling studies on some epoxymorphinan derivatives (e.g., NAQ, NCQ, NAN and INTA) [27,56,57,60], D3.32 may form ionic interactions with the 17-quaternary nitrogen atom of epoxymorphinan derivatives. Thus, the docking poses with this binding feature and highest ChemPLP score were selected as the optimal binding poses and named β-FNA_MORinactive, β-FNA_KORactive, NFF_MORactive, NFF_KORactive, 42B_MORactive, 42B_KORactive, NBP_MORactive, NBP_KORactive, 3-dHNBP _MORinactive, 3-dHNBP _KORactive, NCP_MORactive, NCP_KORactive, 3-dHNCP_MORinactive and 3-dHNCP_KORactive (Supplementary Figure 5).

Based on their docking poses, there were about 20 residues within 5 Å of β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP in the 14 complexes (Supplementary Table 3). As shown in Supplementary Figure 5 & Supplementary Table 3, residues D3.32, Y3.33, M3.36, W6.48, I6.51 and H6.52 located at the orthosteric site were highly conserved in both the KOR and MOR. As described earlier, D3.32 may form ionic interactions with the 17-quaternary nitrogen atom of β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP. Residues Y3.33, M3.36, W6.48, I6.51 and H6.52 may form hydrophobic interactions with the epoxymorphinan scaffolds (‘message’ moieties) of the seven respective compounds. In addition, hydrophobic residues W6.48, I7.39, G7.42 and Y7.43 accommodated the seven compounds' cyclopropylmethyl moieties. The binding modes between the orthosteric sites of the KOR and MOR and the epoxymorphinan scaffolds of the seven ligands were almost the same as those of the reported epoxymorphinan derivatives with the KOR and MOR.

By contrast, it is worth noting that the ‘address’ moieties of β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP seemed to interact with two different subdomains of the allosteric sites of the KOR and MOR. The ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA interacted with the subdomain formed by residues I6.55, E6.58 and Y7.35 of the KOR and residues V6.55, K6.58 and W7.35 of the MOR – namely, ABD1 (Supplementary Figure 5) – whereas the ‘address’ moieties of NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP bound with another subdomain formed by residues Q2.60, WECL1 and L3.29 of the KOR and residues Q2.60, WECL1 and I3.29 of the MOR, defined as ABD2 (Supplementary Figure 5). To obtain relatively stable binding modes and further explore the detailed interactions between ligands and receptors, the 14 ligand–receptor complexes were applied to conduct the subsequent MD simulations.

The stability of the ligand–receptor complexes after MD simulations

MD simulation has been recognized as a feasible computational method for simulating macromolecular conformational dynamics [83,84]. In the present study, 100-ns MD simulations were conducted on each system, including a ligand–receptor complex, POPC bilayer membrane, ions and water molecules. According to previous studies, the average RMSD values of the backbone atoms of a protein less than 3.0 Å indicate the stability of a system [85,86]. As shown in Supplementary Figure 3 & Supplementary Table 2, the 14 systems may achieve equilibrium after 100-ns MD simulations. Thus, the independent MD simulation of each system with the most stable RMSD value was chosen as a representative for the subsequent discussions.

Figure 2A & B displays the most stable RMSD value of the backbone atoms of the proteins and the seven ligands of the 14 systems during the 100-ns MD simulations. As shown in Figure 2A, the conformations of 14 systems achieved equilibrium after about 55-ns MD simulations. The average RMSD values of the backbone atom of the residues in the 14 systems from 80- to 100-ns MD simulations were 2.52, 1.76, 1.83, 2.21, 2.11, 1.87, 2.06, 2.12, 2.55, 2.20, 2.23, 2.28, 2.30 and 2.03 Å, respectively. Moreover, the average RMSD values of the seven ligands in the 14 systems from 80- to 100-ns MD simulations were 1.89, 1.91, 0.60, 1.17, 0.59, 1.17, 1.15, 0.93, 0.86, 1.82, 2.03, 0.94, 2.13 and 0.97 Å, respectively (Figure 2B), which also met the stability requirement that the average RMSD value of a ligand must be below 2.5 Å [85,86].

Figure 2. . The RMSD and RMSF of the 14 complexes relative to their respective starting structures.

The RMSD of the backbone atoms of the proteins (A) and ligands (B), together with the RMSF of the backbone atoms of the β-FNA_MORinactive, β-FNA_KORactive, NFF_MORactive, NFF_KORactive, 42B_MORactive, 42B_KORactive, NBP_MORactive, NBP_KORactive, 3-dHNBP_MORinactive, 3-dHNBP_KORactive, NCP_MORactive, NCP_KORactive, 3-dHNCP_MORinactive and 3-dHNCP_KORactive complexes (C).

β-FNA: β-funaltrexamine; KOR: Kappa opioid receptor; MOR: Mu opioid receptor; NFF: Nalfurafine; RMSD: Root-mean-square deviation; RMSF: Root-mean-square fluctuation.

Furthermore, the analyses of the root-mean-square fluctuation of the backbone atoms of the residues in the 14 systems during the representative MD simulations were conducted using the AMBER 14 module CPPTRAJ [87], and the results are plotted in Figure 2C. As shown in Figure 2C, residues located at the N-terminus, three ICLs, three ECLs and C-terminus displayed higher fluctuation values than residues located at the seven transmembrane helices (TMHs). These observations were consistent with the structural motifs of the opioid receptors. That is, the conformations of the seven TMHs were relatively more rigid and stable, whereas the conformations of the N-terminus, three ICLs, three ECLs and C-terminus were more flexible. This may provide further evidence that the conformations of all 14 systems achieved equilibrium during the 80- to 100-ns MD simulations. In addition, the area per lipid value during the 80- to 100-ns MD simulations of the two representative systems (NFF_KORactive and 42B_KORactive) confirmed the membrane equilibration of the 14 systems (Supplementary Figure 4). Therefore, the MD trajectories from the last 20-ns (80–100 ns) MD simulations were selected to conduct further binding free energy calculation and energy decomposition analysis using the MM/GBSA method.

Binding free energy calculation & energy decomposition analysis for the 14 complexes

The binding free energies, together with four individual energy components (electrostatic energy, ΔEele; van der Waals energy, ΔEvdw; polar and nonpolar contributions to desolvation upon ligand binding, ΔGGB and ΔGSA) of the β-FNA_MORinactive, β-FNA_KORactive, NFF_MORactive, NFF_KORactive, 42B_MORactive, 42B_KORactive, NBP_MORactive, NBP_KORactive, 3-dHNBP_MORinactive, 3-dHNBP_KORactive, NCP_MORactive, NCP_KORactive, 3-dHNCP_MORinactive and 3-dHNCP_KORactive complexes, were calculated using the MM/GBSA method based on the 1000 snapshots extracted from the 80- to 100-ns MD simulations, and the calculated results are summarized in Table 2. In Table 1, the Ki values of β-FNA, NFF and 42B in the MOR and KOR were determined using two different groups, and the Ki values of NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP in the MOR and KOR were determined using the same group. According to Ki, the experimental binding free energy can be calculated using ΔG ≈ RTlnKi. In the present study, the calculated square of correlation coefficient R2 between the calculated and experimental binding free energies of the NBP_MORactive, NBP_KORactive, 3-dHNBP_MORinactive, 3-dHNBP_KORactive, NCP_MORactive, NCP_KORactive, 3-dHNCP_MORinactive and 3-dHNCP_KORactive complexes was 0.63, which indicated the reliability of the predicted results in Table 2.

Table 2. . Binding free energies and four individual energy components of the 14 systems calculated using the MM/GBSA method (kcal/mol).

| System | ΔEele† | ΔEvdw‡ | ΔGGB§ | ΔGSA¶ | ΔEbind# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-FNA_MORinactive | 24.33 | -53.85 | -0.90 | -4.78 | -35.17 |

| β-FNA_KORactive | -69.19 | -52.59 | 91.37 | -5.06 | -35.48 |

| NFF_MORactive | 11.33 | -62.35 | 3.22 | -5.57 | -53.39 |

| NFF_KORactive | -92.91 | -60.87 | 103.88 | -5.20 | -50.44 |

| 42B_MORactive | 25.03 | -54.54 | -12.91 | -5.02 | -47.45 |

| 42B_KORactive | -90.30 | -54.37 | 91.25 | -4.99 | -58.42 |

| NBP_MORactive | 3.50 | -52.11 | -0.47 | -4.52 | -53.62 |

| NBP_KORactive | -105.95 | -56.87 | 108.76 | -4.99 | -59.07 |

| 3-dHNBP_MORinactive | 26.52 | -51.64 | -9.35 | -4.34 | -38.84 |

| 3-dHNBP_KORactive | -94.42 | -61.01 | 106.48 | -4.72 | -53.70 |

| NCP_MORactive | 32.0 | -70.27 | -11.06 | -5.55 | -54.89 |

| NCP_KORactive | -110.43 | -58.51 | 116.19 | -5.33 | -58.10 |

| 3-dHNCP_MORinactive | 37.91 | -57.29 | -15.95 | -4.93 | -40.27 |

| 3-dHNCP_KORactive | -95.63 | -61.69 | 99.11 | -5.46 | -63.68 |

Electrostatic contribution.

Van der Waals contribution.

Polar desolvation contribution.

Nonpolar desolvation contribution.

Predicted binding free energy (without conformational entropy contributions).

β-FNA: β-funaltrexamine; KOR: Kappa opioid receptor; MM/GBSA: Molecular mechanics/generalized born surface area; MOR: Mu opioid receptor; NFF: Nalfurafine.

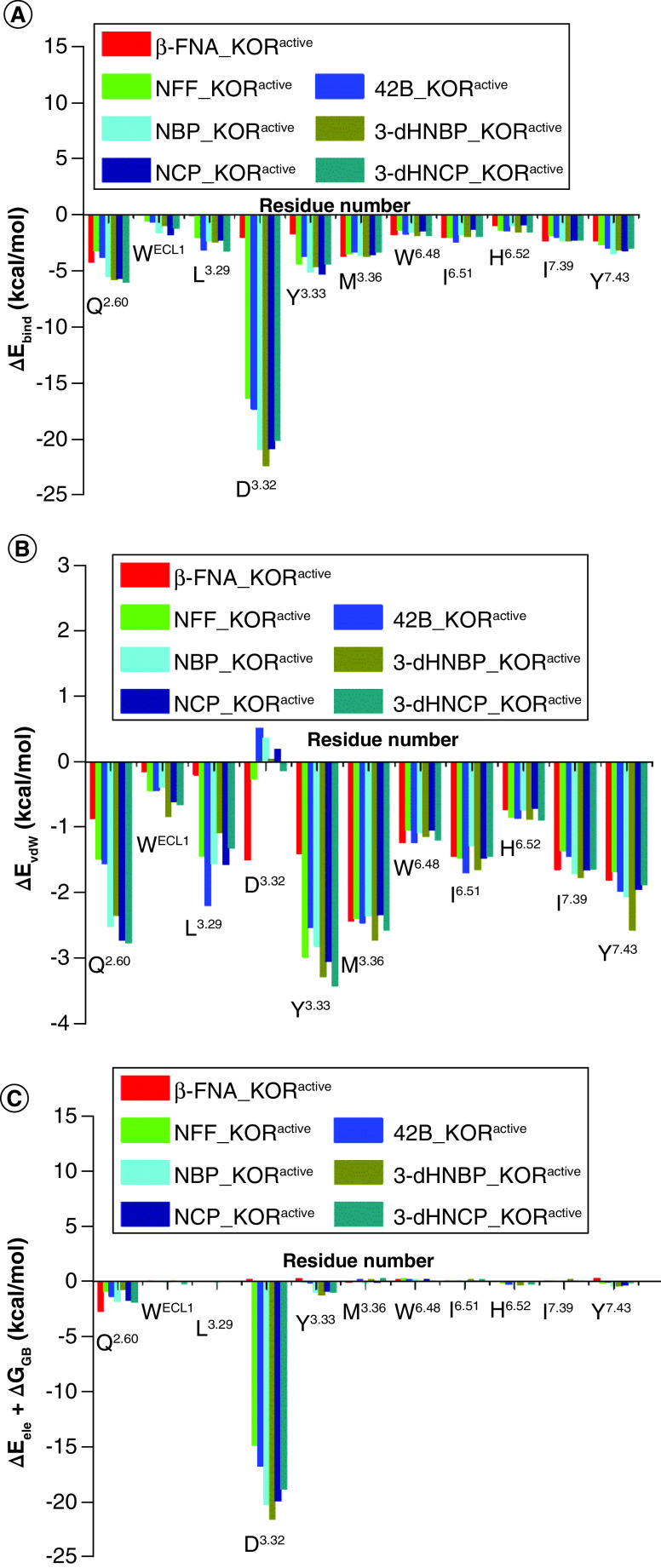

As shown in Table 2, the nonpolar solvation energy (ΔGSA) of the 14 complexes was almost the same. The total electrostatic interaction contribution (ΔEele + ΔGGB) for each complex was 23.43, 22.18, 14.55, 10.97, 12.12, 0.95, 3.03, 2.81, 17.17, 12.06, 20.94, 5.76, 21.96 and 3.48 kcal/mol, respectively, which was unfavorable for the binding of the seven ligands with the MOR and KOR. Notably, the total electrostatic interaction contribution (ΔEele + ΔGGB) between the 42B_MORactive (12.12 kcal/mol) and 42B_KORactive (0.95 kcal/mol) complexes, the NCP_MORactive (20.94 kcal/mol) and NCP_KORactive (5.76 kcal/mol) complexes and the 3-dHNCP_MORinactive (21.96 kcal/mol) and 3-dHNCP_KORactive (3.48 kcal/mol) complexes showed significant differences, which may lead to a possible explanation of the selectivity of 42B, NCP and 3-dHNCP to the KOR over the MOR (Table 1). Moreover, among the four energy components, the greatest energy contribution to the binding of the seven ligands with the KOR and MOR was the van der Waals energy (ΔEvdw). This result was consistent with the fact that most of the amino acid residues located at the orthosteric and allosteric sites were hydrophobic. Therefore, the total electrostatic interaction energy, van der Waals interaction energy and binding free energy were decomposed into ligand–residue pairs using the MM/GBSA method to further explore the key residues related to the binding of the seven ligands with the MOR and KOR.

After the energy decomposition analyses, residues with significant energy contributions (> 1.0 kcal/mol) to the total electrostatic energy, van der Waals energy and binding free energy of the 14 complexes were defined as key residues and selected to conduct further analyses. Among them, V6.55 (MOR)/I6.55 (KOR), K6.58 (MOR)/E6.58 (KOR) and W7.35 (MOR)/Y7.35 (KOR) located at the subdomain ABD1 of the allosteric sites of the MOR and KOR and Q2.60 (MOR and KOR), WECL1 (MOR and KOR) and I3.29 (MOR)/L3.29 (KOR) located at the subdomain ABD2 of the allosteric sites of the MOR and KOR, which may form interactions with the ‘address’ moieties of β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP. In addition, D3.32, Y3.33, M3.36, W6.48, I6.51 and H6.52 located at the orthosteric sites of the KOR and MOR and accommodated the ‘message’ moieties of the seven ligands. The binding modes and detailed interactions between the seven ligands and two receptors were then analyzed to explore their allosteric modulation mechanisms.

Allosteric modulation mechanisms of β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP & 3-dHNCP in the KOR

The functional assay results indicated that β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP functioned as KOR full agonists (Table 1). As described in the molecular docking results, the ‘message’ moiety of β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP bound with the orthosteric site of the KOR, formed by residues D3.32, Y3.33, M3.36, W6.48, I6.51 and H6.52. The subdomain ABD2 of the allosteric site of the KOR accommodated the ‘address’ moiety of NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP, and the subdomain ABD1 of the allosteric site of the KOR accommodated the ‘address' moiety of β-FNA (Supplementary Figure 5A). The binding modes of the ‘message’ moieties after 100-ns MD simulations were similar to the binding modes from the molecular docking studies. It was noted that the binding subdomain of the ‘address' moiety of β-FNA in the β-FNA_KORactive complex shifted from subdomain ABD1 to subdomain ABD2 after MD simulations. Hence, the ‘address’ moiety of all seven ligands formed interactions with subdomain ABD2 of the allosteric site of the KOR after the MD simulations (Figure 3). According to the our previous study on ligands developed based on the ‘message–address’ concept, the interaction of the ‘address’ moiety of the ligand with subdomain ABD2 of the allosteric site of the MOR may produce positive allosteric modulation of the binding and efficacy of the ‘message’ moiety and further induce the receptor's staying in its active state [57]. Therefore, the ABD2 binding subdomain of the ‘address’ moiety of the seven ligands in the allosteric site of the KOR may provide a plausible explanation for the fact that β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP displayed agonist activity toward the KOR.

Figure 3. . The binding modes of the seven ligands in the KOR after MD simulations.

(A) β-FNA_KORactive, (B) NFF_KORactive, (C) 42B_KORactive, (D) NBP_KORactive, (E) 3-dHNBP_KORactive, (F) NCP_KORactive and (G) 3-dHNCP_KORactive. Active KOR shown as a cartoon model in light pink. β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP shown as stick-and-ball models. Key amino acid residues shown as stick models. Carbon atoms: β-FNA in white, NFF in magenta, 42B in cyan, NBP in orange, 3-dHNBP in green, NCP in pink, 3-dHNCP in dark cyan, key amino acid residues of the KOR in light cyan. Subdomain ABD2 of the allosteric site shown as a surface model in light orange. The red arrow in (A) represents the movement orientation of the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA in the β-FNA_KORactive complex.

β-FNA: β-funaltrexamine; KOR: Kappa opioid receptor; NFF: Nalfurafine.

β-FNA in the KOR

In the β-FNA_KORactive complex after MD simulations, the side chain of E6.58 (carboxyl group) may form a polar repulsive force with the acetate group of β-FNA and further repel the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA away from K5.39 (from 4.2 to 5.8 Å) (Figure 4A & Supplementary Figure 6A & Supplementary Table 4). In addition, the amino group of the side chain of Q2.60 located at subdomain ABD2 of the allosteric site of the KOR may form a strong hydrogen bonding interaction with the carbonyl group in the acetate group of β-FNA (from 7.5 to 3.0 Å) (Figure 4A & Supplementary Figure 6A & Supplementary Table 4). Therefore, the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA seemed to favor subdomain ABD2 of the allosteric site of the KOR. The movement of the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA may cause a hydrophobic interaction to form between W6.48 and the epoxymorphinan scaffold of β-FNA in the β-FNA_KORactive complex (-1.9 kcal/mol). This is supported by the distance analyses in Supplementary Table 4. The distance between the atoms at the epoxymorphinan scaffold of β-FNA and the atoms at the side chain of W6.48 decreased by about 0.6 Å after 100 ns MD simulations. Previous studies on the crystal structures of active KOR and MOR have reported that ligands interacting with the side chain of W6.48 may stabilize the conformation of the side chain of W6.48 and help keep it at its active position [60,61]. Therefore, the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA may induce the epoxymorphinan scaffold of β-FNA to exhibit agonist activity toward the KOR. In other words, the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA may function as a positive allosteric modulator of the ‘message’ moiety of β-FNA in the KOR.

Figure 4. . Energy decomposition analyses of the seven ligands in the KOR.

(A) binding free energy, (B) van der Waals interaction and (C) net electrostatic interaction decomposition analyses of β-FNA_KORactive, NFF_KORactive, 42B_KORactive, NBP_KORactive, 3-dHNBP_KORactive, NCP_KORactive and 3-dHNCP_KORactive complexes.

β-FNA: β-funaltrexamine; KOR: Kappa opioid receptor; NFF: Nalfurafine.

NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP & 3-dHNCP in the KOR

As shown in Figure 3B–G, the ‘address’ moieties of the six ligands, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP, bound with the same subdomain ABD2 of the allosteric site in the KOR. The ‘address’ moieties mainly formed aliphatic CH–π interactions with residues Q2.60 and I3.29 and a π–π stacking interaction with WECL1 (Figure 4). Notably, the total binding free energy contributions of Q2.60, WECL1 and L3.29 in the NBP_KORactive, 3-dHNBP_KORactive, NCP_KORactive and 3-dHNCP_KORactive complexes were significantly larger than those in the NFF_KORactive and 42B_KORactive complexes (Table 3). As the interactions between subdomain ABD2 and the ligand were related to the activation of the KOR [60,61], the greater binding affinity between subdomain ABD2 and the ‘address’ moieties of NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP compared with that between subdomain ABD2 and the ‘address’ moieties of NFF and 42B may explain why NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP exhibited relatively higher efficacy to the KOR than did NFF and 42B (Table 1). Moreover, the aliphatic CH–π interaction with L3.29 may help stabilize the conformation of I3.40 and keep it at its active position (Supplementary Figure 6B). As described in the crystal structure of the active KOR, residues I3.40, P5.50 and F6.44 formed the conserved core triad, which was a central ‘micro-switch’ for the activation of the KOR [60]. Taken together, the ‘address’ moieties of NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP may exhibit positive allosteric modulations of their ‘message’ moieties, and all may cause the KOR to remain at its active state, which helps explain the agonism of these ligands toward the KOR.

Table 3. . The binding free energy contributions of Q2.60, WECL1 and I(MOR)/L(KOR)3.29 in NFF_MORactive, NFF_KORactive, 42B_MORactive, 42B_KORactive, NBP_MORactive, NBP_KORactive, 3-dHNBP_KORactive, NCP_MORactiv e, NCP_KORactive and 3-dHNCP_KORactive complexes.

| System | Residue | Total energy (kcal/mol) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q2.60 | WECL1 | I/L3.29 | ||

| NFF_MORactive | -2.99 | -0.45 | -1.03 | -4.47 |

| NFF_KORactive | -3.32 | -0.68 | -2.16 | -6.16 |

| 42B_MORactive | -2.58 | -0.71 | -0.58 | -3.87 |

| 42B_KORactive | -3.92 | -0.73 | -3.27 | -7.92 |

| NBP_MORactive | -5.42 | -1.00 | -2.09 | -8.51 |

| NBP_KORactive | -5.56 | -1.69 | -2.44 | -9.69 |

| 3-dHNBP_KORactive | -5.89 | -1.08 | -2.53 | -9.50 |

| NCP_MORactive | -5.50 | -1.21 | -2.42 | -9.13 |

| NCP_KORactive | -5.77 | -1.89 | -2.39 | -10.05 |

| 3-dHNCP_KORactive | -6.12 | -1.29 | -3.37 | -10.78 |

KOR: Kappa opioid receptor; MOR: Mu opioid receptor; NFF: Nalfurafine.

According to the aforementioned analyses, the interactions between the seven ligands, β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP, and residues Q2.60, D3.32, W6.48 and Y7.43 were involved in the activation of the KOR. Recent studies of the G protein-biased activation and inactivation mechanism of opioid receptors suggested that a ligand directly interacting with residues Q2.60, D3.32 and Y7.43 and further stabilizing the conformation of W6.48 may increase its G protein bias [88,89]. Thus, β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP seem to be potential G protein-biased KOR ligands. In addition, a study of the cryo-electron microscopy structure of the KOR reported that the conformation of the active KOR was highly similar to that of the crystal structure. [90]. Residues D3.49, R3.50, Y3.51, I3.40, P5.50, T6.34, F6.44 and Y5.58 are important for the activation of the KOR. More specifically, breaking the hydrogen bond between R3.50 at TMH3 and T6.34 at TMH6 and forming a hydrogen bond between R3.50 at TMH3 and Y5.58 at TMH5 have been recognized as the switches from the inactive to active state in G protein-coupled receptors [91]. As shown in Supplementary Figure 7 & Supplementary Table 5, nearly identical conformations of these highly conserved residues and the same hydrogen bonds formed between R3.50 at TMH3 and Y5.58 at TMH5 in the β-FNA_ KORactive, NFF_KORactive, 42B_KORactive, NBP_KORactive, 3-dHNBP_KORactive, NCP_KORactive and 3-dHNCP_KORactive complexes, and the active KOR complexing with KOR agonist MP1104 (PDB ID: 6B73) [60] revealed that the KOR in seven complexes formed interactions with the α5 helix of the G protein that were similar to the cryo-electron microscopy structure of the KOR [90]. That is, residues from TMH2, TMH3, ICL2, ICL3 and TMH6 of the KOR exhibited interactions with the α5 helix of the G protein.

Allosteric modulation mechanisms of β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP & 3-dHNCP in the MOR

It has been reported that β-FNA acts as an irreversible MOR antagonist [27]. Based on the binding and functional assay results, 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP acted as low-efficacy MOR partial agonists, whereas NFF, 42B, NBP and NCP functioned as high-efficacy MOR partial agonists (Table 1). As shown in Figure 5, the orthosteric site of the MOR formed by residues D3.32, Y3.33, M3.36, W6.48, I6.51 and H6.52 exhibited similar interactions with the ‘message’ moieties of β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP after 100 ns MD simulations. However, the binding subdomain of the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA, 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP was different from that of the ‘address’ moiety of NFF, 42B, NBP and NCP. That is, the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA, 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP seemed to bind to subdomain ABD1, whereas the ‘address’ moiety of NFF, 42B, NBP and NCP may bind to subdomain ABD2. According to the authors’ previous studies, the different binding modes of the ‘address’ moiety of the epoxymorphinan derivatives with the allosteric site of the opioid receptor may affect the binding affinity or/and efficacy of the ‘message’ moiety with the opioid receptor. The ‘address’ moiety bound with subdomain ABD1 may exhibit negative allosteric modulation of the binding affinity or/and efficacy of the ‘message’ moiety. By contrast, the ‘address’ moiety interacting with subdomain ABD2 may function as a positive allosteric modulator of the binding affinity or efficacy of the ‘message’ moiety [56,57]. Therefore, the different binding subdomains of the ‘address’ moiety in β-FNA_MORinactive/3-dHNBP_MORinactive/3-dHNCP_MORinactive complexes versus NFF_MORactive/42B_MORactive/NBP_MORactive/NCP_MORactive complexes may provide a plausible explanation for the different efficacy profiles with regard to the MOR.

Figure 5. . The binding modes of the seven ligands in the MOR after MD simulations.

(A) β-FNA_MORinactive, (B) 3dHNBP_MORinactive, (C) 3dHNCP_MORinactive, (D) NFF_MORactive, (E) 42B_MORactive, (F) NBP_MORactive and (G) NCP_MORactive complexes after MD simulations. Inactive and active MORs shown as cartoon models in light yellow and light blue, respectively. β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP shown as stick-and-ball models. Key amino acid residues shown as stick models. Carbon atoms: β-FNA in white, NFF in magenta, 42B in cyan, NBP in orange, 3-dHNBP in green, NCP in pink, 3-dHNCP in dark cyan, key amino acid residues of the MOR in dark violet. Subdomains ABD1 and ABD2 of the allosteric site shown as surface models in lemon and light orange, respectively.

β-FNA: β-funaltrexamine; MOR: Mu opioid receptor; NFF: Nalfurafine.

β-FNA in the MOR

The covalent bond formed between the ε-amino group of K5.39 and the β-carbon atom of the double bond in the fumarate of β-FNA in the crystal structure of inactive MOR was not reproducible in the β-FNA_MORinactive complex because of the limitation of classical MD simulations, which cannot simulate the formation or breaking of a covalent bond [92]. Instead, a strong electrostatic interaction was observed between the ε-amino group of K5.39 and the fumarate group of β-FNA after 100-ns MD simulations, indicating such a bond formation in the β-FNA_MORinactive complex. This seemed to be supported by the net electrostatic energy contribution of K5.39 (-9.19 kcal/mol) (Figure 6C) and the distance analysis displayed in Supplementary Table 4 (2.9 Å) and Supplementary Figure 6A. Thus, because of this dramatically strong electrostatic interaction, the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA stayed at subdomain ABD1 of the allosteric site of the MOR after 100-ns MD simulations. Consequently, the hydrophobic interactions between W6.48 and the epoxymorphinan scaffold of β-FNA were extremely weakened (-0.28 kcal/mol). Previous studies on the crystal structures of the active KOR and MOR have reported that ligands interacting with the side chain of W6.48 may stabilize the conformation of the side chain of W6.48 and help keep it at its active position [60,61]. Therefore, the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA may induce the ‘message’ moiety of β-FNA to exhibit antagonist activity toward the MOR. In other words, the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA seemed to act as a negative allosteric modulator of the ‘message’ moiety of β-FNA in the MOR.

Figure 6. . Energy decomposition analyses of the seven ligands in the MOR.

(A & B) binding free energy, (C & D) van der Waals interaction and (E & F) net electrostatic interaction decomposition analyses of β-FNA_MORinactive, 3dHNBP_MORinactive, 3dHNCP_MORinactive, NFF_MORactive, 42B_MORactive, NBP_MORactive and NCP_MORactive complexes.

β-FNA: β-funaltrexamine; MOR: Mu opioid receptor; NFF: Nalfurafine.

3-dHNBP & 3-dHNCP in the MOR

Based on the original molecular docking study (Supplementary Figure 5B), the ‘address’ moieties of 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP bound with subdomain ABD2 of the allosteric site in the MOR. However, after 100-ns MD simulations, the binding subdomain of the ‘address’ moieties of 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP changed from subdomain ABD2 to subdomain ABD1 (Figure 5B & C). The ‘address’ moieties of 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP mainly formed interactions with three residues, K5.39, V6.55 and W7.35. K5.39 formed electrostatic interactions with the ‘address’ moieties of 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP. V6.55 and W7.35, located at subdomain ABD1 of the allosteric site in the MOR, formed hydrophobic interactions with the ‘address’ moieties of 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP. These interactions were supported by the energy decomposition analyses (Figure 6). In addition, similar to β-FNA in the MOR, the hydrophobic interactions between W6.48 and the epoxymorphinan scaffolds of 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP (Figure 6) were too weak to stabilize the conformation of the side chain of W6.48. Thus, the ‘address’ moieties of 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP exhibited allosteric modulations of their ‘message’ moieties similar to that of the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA to its ‘message’ moiety in the MOR, indicating that both ligands acted as low-efficacy partial agonists of the MOR.

NFF, 42B, NBP & NCP in the MOR

As NFF, 42B, NBP and NCP functioned as high-efficacy MOR partial agonists (Table 1), the agonist-bound MOR (PDB ID: 5C1M) was selected as their target protein template. Comparing their binding modes in the active MOR with those of β-FNA, 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP in the inactive MOR, the most significant different interactions were the hydrophobic interaction with HN.54 and the hydrogen bonding interaction with SN.55 at the N-terminus in the NFF_MORactive, 42B_MORactive, NBP_MORactive and NCP_MORactive complexes. Because of the flexibility of the N-terminus, the side chain conformations of residues HN.54 and SN.55 in these four complexes were not identical (Figure 5D–G). Consequently, the hydrophobic interaction between HN.54 and the linker of NFF and the hydrogen bonding interaction between SN.55 and the linker of NFF were formed in the NFF_MORactive complex (Figure 5D), which can be proved by the van der Waals interaction energy contribution of HN.54 (-1.77 kcal/mol) (Figure 6D & Supplementary Table 6) and the net electrostatic energy contribution of SN.55 (-3.31 kcal/mol) (Figure 6F & Supplementary Table 6). By contrast, there seemed to be no hydrogen bond formation between SN.55 and the linker of 42B, whereas only the hydrophobic interaction between HN.54 and the linker of 42B was observed in the 42B_MORactive complex (Figures 5E & 6D). In the NBP_MORactive and NCP_MORactive complexes, HN.54 and SN.55 were far away from NBP and NCP. Hence, there was no hydrogen bond or hydrophobic interaction formed with NBP or NCP (Figures 5F & G & 6D & F).

Zooming further in, the steric hindrance caused by the side chain of HN.54 may induce the ‘address’ moieties of NFF and 42B to move away from I3.29 (Supplementary Table 4). This movement may further affect the binding of the ‘message’ moieties of NFF and 42B with the orthosteric site of the MOR. Taking the positions of Y3.33, W6.48, I6.51, H6.52 and Y7.43 at the orthosteric site into consideration (Figure 5D & E), the interactions between Y3.33 and the two ligands seemed weakened, whereas the interactions between residues W6.48, I6.51, H6.52 and Y7.43 and the two ligands strengthened. This was supported by the energy decomposition and distance analyses (Figure 6 & Supplementary Table 4). The hydrophobic interaction between W6.48 and the epoxymorphinan scaffolds of NFF and 42B (Figure 6) may further stabilize the side chain of W6.48 in its active position. This stabilization effect indicated that the ‘address’ moieties of NFF and 42B may induce positive allosteric modulations of their epoxymorphinan scaffolds of NFF and 42B, which may keep the MOR at its active state.

In contrast to the NFF_MORactive and 42B_MORactive complexes, as discussed earlier, no interactions were observed between residues HN.54 and SN.55 and the linkers of NBP and NCP. The ‘address’ moieties of NBP and NCP instead may form aliphatic CH–π interactions with residues Q2.60 and I3.29 and π–π stacking interactions with WECL1 (Figure 6), which is similar to NBP and NCP in the KOR. The total binding free energy contributions of Q2.60, WECL1 and I3.29 in the NBP_MORactive and NCP_MORactive complexes were also similar to those in the NBP_KORactive and NCP_KORactive complexes (Table 3). Consequently, the allosteric modulation mechanism of the ‘address’ moieties of NBP and NCP in the MOR was similar to that of NBP and NCP in the KOR. The aliphatic CH–π interaction with I3.29 may help stabilize the conserved core triad formed by residues I3.40, P5.50 and F6.44 and further keep it at the active position. Therefore, similar to NBP and NCP in the KOR, the ‘address’ moieties of NBP and NCP exhibited positive allosteric modulations of their ‘message’ moieties and kept the MOR at its active state.

Using β-FNA, NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP in the KOR as references, the interactions between W6.48 of the MOR and β-FNA, 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP might not be strong enough to stabilize the conformation of the side chain of W6.48, whereas NFF, 42B, NBP and NCP formed strong interactions with W6.48 and further stabilized the side chain of W6.48 at its active state. Thus, the MOR interacted with NFF, 42B, NBP and NCP may increase its G protein bias tendency. Moreover, with the exception of the differences in agonist structure, the conformations of the key amino acids at the active-state binding pocket formed interactions with the agonist (BU72 or DAMGO) are highly similar in both the crystal and cryo-electron microscopy structures of the MORs [93]. Most importantly, the conformations of residues D3.49, R3.50, Y3.51, I3.40, P5.50, T6.34, F6.44 and Y5.58 in the NFF_MORactive, 42B_MORactive, NBP_MORactive and NCP_MORactive complexes are quite similar to that in the crystal structure of the active MOR complexing with the MOR agonist BU72. Such that observations indicated that NFF, 42B, NBP and NCP may induce the MOR formed similar interactions with the α5 helix of the G protein to that of the cryo-electron microscopy structure of the MOR with the α5 helix of the G protein (Supplementary Figure 8) [93]. TMHs 3, 5 and 6 and ICL3 of the MOR in the NFF_MORactive, 42B_MORactive, NBP_MORactive and NCP_MORactive complexes may be able to form interactions with the α5 helix of the G protein. In addition, the well-recognized micro-switches, hydrogen bonds formed between R3.50 and Y5.58 in the NFF_MORactive, 42B_MORactive, NBP_MORactive and NCP_MORactive complexes and hydrogen bonds formed between R3.50 and T6.34 in the β-FNA_MORinactive, 3-dHNBP_MORinactive and 3-dHNCP_MORinactive complexes further verified the agonist activities of NFF, 42B, NBP and NCP and the antagonist activities of β-FNA, 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP toward the MOR.

The effect of the 3-hydroxy group on ligand selectivity profile

The compounds 42B, 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP are 3-dehydroxy derivatives of NFF, NBP and NCP, respectively. Thus, the six ligands were divided into three pairs: NFF and 42B, NBP and 3-dHNBP and NCP and 3-dHNCP. The only difference in the chemical structures of each pair was the 3-hydroxy group on the phenolic moiety of the epoxymorphinan scaffold. The binding modes of NFF, 42B, NBP, 3-dHNBP, NCP and 3-dHNCP in the MOR and KOR indicated that residues Y3.33, K5.39, V5.42, W6.48, I6.51 and H6.52 formed a pocket that perfectly surrounded the phenyl moiety of the six ligands. The binding free energy contributions of the six residues in the NFF_MORactive, NFF_KORactive, 42B_MORactive, 42B_KORactive, NBP_MORactive, NBP_KORactive, 3-dHNBP_MORinactive, 3-dHNBP_KORactive, NCP_MORactive, NCP_KORactive, 3-dHNCP_MORinactive and 3-dHNCP_KORactive complexes are summarized in Supplementary Table 7. Clearly, in the MOR, the ligands with a 3-hydroxy group formed a stronger interaction with the six residues than the ligands without a 3-hydroxy group. In the KOR, the ligands with a 3-hydroxy group had a binding affinity with the six residues similar to that of the ligands without a 3-hydroxy group (Supplementary Table 7).

With regard to the NFF and 42B pair, as described earlier, both NFF and 42B functioned as mixed-action KOR full agonists and MOR partial agonists, whereas the lack of a 3-hydroxy group seemed to induce selectivity between the MOR and the KOR for 42B. However, for the other two pairs, NBP versus 3-dHNBP and NCP versus 3-dHNCP, 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP exhibited no significant selectivity profile change between the MOR and the KOR compared with NBP and NCP, respectively (Table 1). As described earlier, the ‘address’ moieties of 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP in the inactive MOR seemed to bind to subdomain ABD1 after MD simulations, whereas the ‘address’ moieties of NBP and NCP in the active MOR seemed to bind to subdomain ABD2 (Figure 5B, C, F & G). Therefore, we may conclude that the ‘address’ moieties binding with different subdomains may induce significant different allosteric modulations to the binding of the ‘message’ moieties. The interactions between Y7.43 of the MOR and the ‘address’ moiety of 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP demonstrated no significant difference compared with the interactions with the ‘address’ moiety of NBP and NCP (Supplementary Table 7). That is, for these two pairs, removal of the 3-hydroxy group did not induce a selectivity profile change to the MOR and KOR. Therefore, the authors postulated that removal of the 3-hydroxy group on the epoxymorphinan scaffold may be a potential method for gaining selectivity between the MOR and KOR if the same or similar ligand efficacy profile is observed. As a consequence, two pairs of ligands designed by the replacement of a bromine atom of NBP with a chlorine atom and methyl group, together with their 3-dehydroxy derivatives, have been synthesized and biologically evaluated. The binding assay results revealed that the 3-dehydroxy derivatives demonstrated reduced binding affinities for the MOR and KOR compared with ligands with the 3-hydroxy group. Further comprehensive functional assay and molecular modeling studies will be conducted to verify the authors' prediction in the future.

Conclusion

An opioid ligand with a mixed KOR agonist and MOR agonist/antagonist profile may be a potential therapeutic for psychostimulant abuse and addiction. β-FNA, NFF and 42B are three representative mixed-action KOR/MOR ligands. They possess a similar ‘message’ moiety (epoxymorphinan scaffold) but different ‘address’ moieties. In the present work, molecular modeling methods, including molecular docking and MD simulations, were utilized to explore the selectivity and activation mechanisms of these three mixed-action KOR/MOR ligands.

The computational results indicated that two subdomains (ABD1 and ABD2) of the allosteric site of the MOR and KOR may accommodate the ‘address’ moiety of the ligands. Which subdomain would be ‘favorable’ to the ‘address’ moiety of the ligands seemed critical to their efficacy profile. The electrostatic interaction between the ε-amino group of K5.39 and the β-carbon of the double bond in the fumarate of β-FNA caused the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA to interact with subdomain ABD1 such that the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA may exhibit negative allosteric modulation of the binding of its ‘message’ moiety in the MOR. By contrast, in the β-FNA_KORactive complex, the polar repulsive force between the side chain of E6.58 and the acetate group of β-FNA as well as the hydrogen bonding interaction between the amino group of the side chain of Q2.60 and the carbonyl group in the acetate group of β-FNA induced the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA to interact with subdomain ABD2 and further caused the ‘address’ moiety of β-FNA to produce positive allosteric modulation of the binding of its ‘message’ moiety in the KOR.

With regard to NFF and 42B, because of the aliphatic CH–π interaction between the ‘address’ moiety of NFF and 42B and residues Q2.60 and I/L3.29, the ‘address’ moiety of NFF and 42B bound with subdomain ABD2 of the KOR and MOR. This seemed to be the reason why the ‘address’ moiety of NFF and 42B functioned like a positive allosteric modulator in the MOR and KOR. Moreover, the 3-hydroxy group of the epoxymorphinan scaffold may play a critical role in the selectivity profile of NFF and 42B with regard to the MOR and KOR. However, seemingly due to the fact that 3-dHNBP and 3-dHNCP carry different efficacy profiles in the MOR from those of NBP and NCP, the 3-hydroxy group had no significant influence on selectivity profiles for these two pairs of ligands between the MOR and KOR.

In summary, a combination of multiple computational and molecular modeling methods seemed feasible for characterizing the selectivity and activation mechanisms of β-FNA, NFF and 42B to the MOR and KOR. It is speculated that the ‘address’ moiety with high π-electron density may induce activation of the MOR and KOR. In addition, removal of the 3-hydroxy group of an epoxymorphinan ligand may help achieve selectivity between the MOR and KOR (presumably, the dehydroxy product maintains the same or similar efficacy profile on the receptors). We expect our study may provide guidance for the development of novel and more potent mixed KOR agonists and MOR partial agonists to potentially treat psychostimulant abuse and addiction with fewer side effects.

Future perspective

An opioid ligand acting as a mixed KOR agonist and MOR partial agonist/antagonist may be applied to treat psychostimulant abuse with fewer side effects. β-FNA, NFF and 42B represent three different types of mixed-action KOR/MOR ligands. β-FNA functions as a mixed KOR partial agonist and MOR antagonist. NFF and its 3-dehydroxy derivative, 42B, act as selective KOR full agonists and MOR partial agonists. Exploring the modulation and selectivity mechanisms of these compounds may provide clues to the future design of novel mixed-action KOR/MOR bitopic modulators to potentially treat psychostimulant abuse.

Summary points.

The selectivity and activation mechanisms of three representative mixed-action kappa opioid receptor/mu opioid receptor (KOR/MOR) ligands, β-funaltrexamine, nalfurafine and 42B, were explored by molecular modeling methods in the present work.

To gain further insights into the effects of the 3-hydroxy group on ligand selectivity profile, four more mixed-action KOR/MOR ligands, NBP, NCP and their 3-dehydroxy derivatives, 3-dehydroxy-NBP and 3-dehydroxy-NCP, were studied.

The ‘address’ moiety of bitopic modulators bound with different subdomains of the allosteric site of the KOR and MOR may exhibit significantly different allosteric modulation of the binding of the ‘message’ moiety with the orthosteric site of the KOR and MOR.

The ‘address’ moiety of bitopic modulators bound with subdomains formed by residues Q2.60 (MOR and KOR) and I(MOR)/L(KOR)3.29 may show positive allosteric modulation of the ‘message’ moiety.

The ‘address’ moiety of bitopic modulators bound with subdomains formed by residues V(MOR)/I(KOR)6.55, K(MOR)/E(KOR)6.58 and W(MOR)/Y(KOR)7.35 seems to function as a positive allosteric modulator of the ‘message’ moiety.

The ‘address’ moiety of bitopic modulators with high π-electron density may induce activation of the MOR and KOR.

Removal of the 3-hydroxy group of an epoxymorphinan derivative may help achieve selectivity between the MOR and KOR (presumably, the dehydroxy product maintains the same or similar efficacy profile on the receptors).

The authors’ study may provide guidance for the development of novel and more potent mixed KOR agonists and MOR partial agonists to potentially treat psychostimulant abuse and addiction with fewer side effects.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplementary data

To view the supplementary data that accompany this paper please visit the journal website at: www.future-science.com/doi/suppl/10.4155/fmc-2020-0308

Disclaimer

The content of this work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the NIH.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work was partially supported by the Virginia Commonwealth University Center for High-Performance Computing and NIH/National Institute on Drug Abuse grants R01DA024022, R01DA044855 and UG3DA050311 (Y Zhang) and R01 DA041359, R21 DA045274 and P30 DA013429 (L-Y Liu-Chen). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. www.samhsa.gov/data/

- 2.White FJ, Kalivas PW. Neuroadaptations involved in amphetamine and cocaine addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 51(1–2), 141–153 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lott DC, Lott DC, Kim S-J et al. Serotonin transporter genotype and acute subjective response to amphetamine. Am. J. Addict. 15(5), 327–335 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broadbear JH, Sumpter TL, Burke TF et al. Methocinnamox is a potent, long-lasting, and selective antagonist of morphine-mediated antinociception in the mouse: comparison with clocinnamox, β-funaltrexamine, and β-chlornaltrexamine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 294(3), 933–940 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Addiction Centers. https://americanaddictioncenters.org/stimulant-drugs

- 6.D'Souza MS. Brain and cognition for addiction medicine: from prevention to recovery neural substrates for treatment of psychostimulant-induced cognitive deficits. Front. Psychiatry 10, 509 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buttner A. Neuropathological alterations in cocaine abuse. Curr. Med. Chem. 19(33), 5597–5600 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Redila VA, Chavkin C. Stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking is mediated by the kappa opioid system. Psychopharmacology 200(1), 59–70 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karkhanis A, Holleran KM, Jones SR. Dynorphin/kappa opioid receptor signaling in preclinical models of alcohol, drug, and food addiction. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 136, 53–88 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruijnzeel AW. Kappa-opioid receptor signaling and brain reward function. Brain Res. Rev. 62(1), 127–146 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crawford C, McDougall S, Bolanos C, Hall S, Berger S. The effects of the kappa agonist U-50,488 on cocaine-induced conditioned and unconditioned behaviors and Fos immunoreactivity. Psychopharmacology 120(4), 392–399 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shippenberg T, LeFevour A, Heidbreder C. Kappa-opioid receptor agonists prevent sensitization to the conditioned rewarding effects of cocaine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 276(2), 545–554 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heidbreder CA, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Shoaib M, Shippenberg TS. Development of behavioral sensitization to cocaine: influence of kappa opioid receptor agonists. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 275(1), 150–163 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kivell B, Paton K, Kumar N et al. Kappa opioid receptor agonist mesyl Sal B attenuates behavioral sensitization to cocaine with fewer aversive side-effects than salvinorin A in rodents. Molecules 23(10), 2602 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kivell BM, Ewald AW, Prisinzano TE. Salvinorin A analogs and other kappa-opioid receptor compounds as treatments for cocaine abuse. Adv. Pharmacol. 69, 481–511 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shippenberg T, Zapata A, Chefer V. Dynorphin and the pathophysiology of drug addiction. Pharmacol. Ther. 116(2), 306–321 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Todtenkopf MS, Marcus JF, Portoghese PS, Carlezon WA. Effects of κ-opioid receptor ligands on intracranial self-stimulation in rats. Psychopharmacology 172(4), 463–470 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Opposite effects of mu and kappa opiate agonists on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens and in the dorsal caudate of freely moving rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 244(3), 1067–1080 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • An in vivo study on the opposite effects of mu and kappa agonists on dopamine release.

- 19.Phan NQ, Lotts T, Antal A, Bernhard JD, Ständer S. Systemic kappa opioid receptor agonists in the treatment of chronic pruritus: a literature review. Acta Derm. Venereol. 92(5), 555–560 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan ZZ. μ-opposing actions of the κ-opioid receptor. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 19(3), 94–98 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greedy BM, Bradbury F, Thomas MP et al. Orvinols with mixed kappa/mu opioid receptor agonist activity. J. Med. Chem. 56(8), 3207–3216 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou Y, Kreek MJ. Clinically utilized kappa-opioid receptor agonist nalfurafine combined with low-dose naltrexone prevents alcohol relapse-like drinking in male and female mice. Brain Res. 1724, 146410 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagase H, Imaide S, Hirayama S, Nemoto T, Fujii H. Essential structure of opioid κ receptor agonist nalfurafine for binding to the κ receptor 2: synthesis of decahydro (iminoethano) phenanthrene derivatives and their pharmacologies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 22(15), 5071–5074 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toll L, Berzetei-Gurske I, Polgar W et al. Standard binding and functional assays related to medications development division testing for potential cocaine and opiate narcotic treatment medications. NIDA Res. Monogr. 178, 440–466 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takemori A, Portoghese PS. Affinity labels for opioid receptors. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 25(1), 193–223 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen C, Yin J, de Riel JK et al. Determination of the amino acid residue involved in [3H] β-funaltrexamine covalent binding in the cloned rat μ opioid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 271(35), 21422–21429 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS et al. Crystal structure of the μ-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature 485(7398), 321–326 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Describes the crystal structure of the mouse mu opioid receptor in complex with an irreversible morphinan antagonist.

- 28.Cami-Kobeci G, Neal AP, Bradbury FA et al. Mixed κ/μ opioid receptor agonists: the 6β-naltrexamines. J. Med. Chem. 52(6), 1546–1552 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tam S, Liu-Chen L. Reversible and irreversible binding of beta-funaltrexamine to mu, delta and kappa opioid receptors in guinea pig brain membranes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 239(2), 351–357 (1986). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakao K, Mochizuki H. Nalfurafine hydrochloride: a new drug for the treatment of uremic pruritus in hemodialysis patients. Drugs Today (Barc.) 45(5), 323 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inui S. Nalfurafine hydrochloride to treat pruritus: a review. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 8, 249–255 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Systematic review of nalfurafine (NFF).

- 32.Schattauer SS, Kuhar JR, Song A, Chavkin C. Nalfurafine is a G-protein biased agonist having significantly greater bias at the human than rodent form of the kappa opioid receptor. Cell. Signal. 32, 59–65 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao D, Huang P, Chiu Y-T et al. Comparison of pharmacological properties between the kappa opioid receptor agonist nalfurafine and 42B, its 3-dehydroxy analogue: disconnect between in vitro agonist bias and in vivo pharmacological effects. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 11(19), 3036–3050 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y, Tang K, Inan S et al. Comparison of pharmacological activities of three distinct κ ligands (salvinorin A, TRK-820 and 3FLB) on κ opioid receptors in vitro and their antipruritic and antinociceptive activities in vivo. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 312(1), 220–230 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasebe K, Kawai K, Suzuki T et al. Possible pharmacotherapy of the opioid κ receptor agonist for drug dependence. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1025(1), 404–413 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mori T, Nomura M, Nagase H, Narita M, Suzuki T. Effects of a newly synthesized κ-opioid receptor agonist, TRK-820, on the discriminative stimulus and rewarding effects of cocaine in rats. Psychopharmacology 161(1), 17–22 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White J. Drug addiction: from basic research to therapy. Drug Alcohol Rev. 28(4), 455–455 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunn A, Windisch K, Ben-Ezra A et al. Modulation of cocaine-related behaviors by low doses of the potent KOR agonist nalfurafine in male C57BL6 mice. Psychopharmacology 237(8), 2405–2418 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawai K, Hayakawa J, Miyamoto T et al. Design, synthesis, and structure–activity relationship of novel opioid κ-agonists. Biorg. Med. Chem. 16(20), 9188–9201 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waldhoer M, Bartlett SE, Whistler JL. Opioid receptors. Annu. Rev. Biochem 73(1), 953–990 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Livingston KE, Stanczyk MA, Burford NT, Alt A, Canals M, Traynor JR. Pharmacologic evidence for a putative conserved allosteric site on opioid receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 93(2), 157–167 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Remesic M, Hruby VJ, Porreca F, Lee YS. Recent advances in the realm of allosteric modulators for opioid receptors for future therapeutics. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 8(6), 1147–1158 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marino KA, Shang Y, Filizola M. Insights into the function of opioid receptors from molecular dynamics simulations of available crystal structures. Br. J. Pharmacol. 175(14), 2834–2845 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frances B, Gout R, Monsarrat B, Cros J, Zajac J-M. Further evidence that morphine-6 beta-glucuronide is a more potent opioid agonist than morphine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 262(1), 25–31 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kato H. Pharmacological effects of a mu-opioid receptor antagonist naltrexone on alcohol dependence. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi 43(5), 697–704 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roth BL, Baner K, Westkaemper R et al. Salvinorin A: a potent naturally occurring nonnitrogenous kappa opioid selective agonist. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 99(18), 11934–11939 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Livingston KE, Traynor JR. Allostery at opioid receptors: modulation with small molecule ligands. Br. J. Pharmacol. 175(14), 2846–2856 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gregory KJ, Dong EN, Meiler J, Conn PJ. Allosteric modulation of metabotropic glutamate receptors: structural insights and therapeutic potential. Neuropharmacology 60(1), 66–81 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allegretti M, Cesta MC, Locati M. Allosteric modulation of chemoattractant receptors. Front. Immunol. 7, 170 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Comprehensive review of the modulation of allosteric modulators to the orthosteric ligands in G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR).

- 50.Stolzenberg S, Michino M, LeVine MV, Weinstein H, Shi L. Computational approaches to detect allosteric pathways in transmembrane molecular machines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1858(7), 1652–1662 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hertig S, Latorraca NR, Dror RO. Revealing atomic-level mechanisms of protein allostery with molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS Comp. Biol. 12(6), e1004746 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Collier G, Ortiz V. Emerging computational approaches for the study of protein allostery. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 538(1), 6–15 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Systematically summarizes the computational approaches to studying communication in allosteric proteins.

- 53.Feher VA, Durrant JD, Van Wart AT, Amaro RE. Computational approaches to mapping allosteric pathways. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 25, 98–103 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stolzenberg S, Quick M, Zhao C et al. Mechanism of the association between Na+ binding and conformations at the intracellular gate in neurotransmitter: sodium symporters. J. Biol. Chem. 290(22), 13992–14003 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]