Graphical abstract

Keywords: Biosynthesis of Au/ Fe3O4 nanoparticles, Sonochemical activation, Sonocatalytic degradation, Spectroscopy

Highlights

-

•

A sonochemical activation-assisted biosynthesis of Au/Fe3O4 NP’s is proposed.

-

•

Piper auritum was employed as reducing agent of metallic precursor.

-

•

Au/Fe3O4 NP’s shows an enhanced catalytic activity in degradation of methyl orange.

-

•

A superparamagnetic behavior of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles was observed.

-

•

The sonocatalytic process and degradation pathway involved were described in detail.

Abstract

In this research, a sonochemical activation-assisted biosynthesis of Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles is proposed. The proposed synthesis methodology incorporates the use of Piper auritum (an endemic plant) as reducing agent and in a complementary way, an ultrasonication process to promote the synthesis of the plasmonic/magnetic nanoparticles (Au/Fe3O4). The synergic effect of the green and sonochemical synthesis favors the well-dispersion of precursor salts and the subsequent growth of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles.

The hybrid green/sonochemical process generates an economical, ecological and simplified alternative to synthesizing Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles whit enhanced catalytic activity, pronounced magnetic properties. The morphological, chemical and structural characterization was carried out by high- resolution Scanning electron microscopy (HR-SEM), Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS) and X-Ray diffraction (XRD), respectively. Ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) and X-ray photoelectron (XPS) spectroscopy confirm the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles obtention. The magnetic properties were evaluated by a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM). Superparamagnetic behavior, of the Au/ Fe3O4 nanoparticles was observed (Ms = 51 emu/g and Hc = 30 Oe at 300 K). Finally, the catalytic activity was evaluated by sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange (MO). In this stage, it was possible to achieve a removal percentage of 91.2% at 15 min of the sonocatalytic process (160 W/42 kHz). The initial concentration of the MO was 20 mg L−1, and the Fe3O4-Au dosage was 0.075 gL−1. The MO degradation process was described mathematically by four kinetic adsorption models: Pseudo-first order model, Pseudo-second order model, Elovich and intraparticle diffusion model.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the magnetic-plasmonic materials have been widely studied due to their applications as bifunctional nanomaterials in several areas, including biology, biomedicine, bio-labelling, optics, electronics and catalysis [1], [2], [3]. Generally, the magnetic-plasmonic materials are composed in their magnetic part by superparamagnetic iron oxides nanoparticles (SPION), which are employed in wastewater treatment, heterogeneous catalysis, drug delivery, cancer treatment, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), biological separation, photocatalysis and hyperthermia [4], [5], [6]. Regarding the plasmonic part, are composed of a noble metal such as Au. In whose case has been employed in electrochemical sensors, biocompatible systems, as antibacterial material and advanced oxidation process (AOPs) [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. Recently, the AOPs has reported a high efficiency in wastewater treatment and pollutant degradation due to the AOPs promote the formation of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals, which exhibits a significant oxidation potential [12], [13], [14]. Some AOPs such as sonolysis, sonocatalysis, sonophotocatalysis, electro-Coagulation, electro-peroxene and Fenton process, among others, has been employed in the degradation of Methylene Blue, Methyl Orange, Acid Orange 7 (AO7), Basic Violet 10 (BV10), diclofenac, ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, Arsenate, Auramine-O (AO, acid blue 129, Chromium, nitrophenol [13], [15], [16], [17], [18].

Nonetheless, the properties of the magnetic-plasmonic materials depend in great measure of the morphology and particle size distribution [19]. In this sense, the implementation and study of new methodologies to synthesize magnetic plasmonic materials are focused on the green chemical and the use of the physic-chemical procedures that reduce or eliminate the use of toxic chemical reagents [20], [21], [22], [23].

In recent years, sonochemistry has been widely studied due that offers a great quantity of application in many fields of knowledge. Nonetheless, the potential sonochemistry applications have not been exploited in deep [20], [21]. Specifically, in the sonochemical synthesis of nanomaterials, the use of ultrasound in chemical reactions, favors the dispersion of the reactive species in the synthesis process. The propagation of ultrasound waves in a liquid generates the acoustic cavitation phenomena, which provide a mechanical activation to the reaction, given as result the destruction of the attractive forces of molecules in the liquid phase [1]. The sonochemical synthesis has been generally employed to obtain well-dispersed and core–shell type nanoparticles [1].

On the other hand, the employ of the green chemistry in the synthesis of metallic and bimetallic nanoparticles has covered a preponderant role due to the green chemistry reduce or eliminate the use and/or generation of hazardous substances [7], [24], [25]. In this sense, the great quantity of organic and biocompatible components presents in the plant extracts (antioxidants, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, also known as secondary metabolites, which including the flavones, flavanols, isoflavones, flavanones and anthocyanidins), have promoted the use of plant extracts as reducing or stabilizing agents in the synthesis of nanomaterials, due that these organic components are directly involved in the reduction of metallic ions of the precursors [26], [27].

The use of the endemic plant species such as Cynara cardunculus, Silybum marianum, Lonicera japonica, Melissa officinalis, Artemisia absinthium, Anthemis nobilis, Lonicera japonica, Thymus kotschyanus, Moringa oleifera flower, Cnicus Benedictus and Justicia spicigera were reported in the obtention of Au and Fe3O4 NP’s [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]. Nonetheless, the Piper auritum extract, has not been employed for the magnetic plasmonic nanoparticles of Au/Fe3O4 composition. The Piper auritum is an endemic and medicinal plant that grows in the tropical area of Central America. The Piper auritum, offers antimicrobial properties due to the great quantity of phytoalexins in their composition, which are compound of low molecular weight in the Piper auritum as result of the biotic and abiotic stresses [33], [34], [35]. In this sense, this work proposes the green synthesis of Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles by Piper auritum extract and sonochemical activation. The synergic effect of the green synthesis and the sonochemical synthesis offers a functional methodology to the obtention of Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles with significant catalytic and magnetic properties. Complementary, the sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange is also studied, being possible to achieve a removal percentage of 91.2% at 15 min of the sonocatalytic process (160 W/42 kHz). Is important to mentioning that result obtained were highly competitive in relation to those reported in the literature, considering the simplification and economy of the catalyst synthesis route, as well as the low power of the ultrasound equipment and mainly the short period of time in which the sonocatalytic degradation was carried out.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Sonochemical activation-assisted green synthesis of Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles

The proposed synthesis of Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles, is based on the precursor salts reduction method by Piper auritum extract.

In the first stage of the process, The Piper auritum extract was obtained from the mixture of 200 ml of deionized water with 15 g of Piper auritum leaves (previously dried). The mixture obtained was heated at 100 °C for 10 min. In parallel form, a HAuCl4·3H2O solution at 50 mM was prepared. The Piper auritum extract and the HAuCl4·3H2O solution were mixed and ultrasonicated at 42 kHz for 15 min. Finally, a solution of salt precursors of de FeCl3·6H2O and FeCl2·4H2O was incorporated into the reaction in a ratio Fe (III)/Fe (II) = 2 under ultrasonic agitation for 60 min. The ultrasonic bath was operated at 42 kHz of frequency and 160 W (Digital Ultrasonic Cleaner, Brand: Kendall, Model: CD-4820; 9.5 × 5.9 × 3.0 in.) in all phases of the synthesis. The water volume employed in the ultrasonic bath was 1750 ml. The Ph reaction was adjusted to 11 by NaOH solution. The Au@Fe3O4 nanoparticles were washed whit isopropyl alcohol and lyophilized for their characterizations. Fig. 1 shows the green synthesis of Au@Fe3O4 by Sonochemical activation.

Fig. 1.

Illustrative scheme of the sonochemical activation-assisted biosynthesis of Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles.

2.2. Sonocatalytic degradation of Methylene orange (MO)

The Sonocatalytic degradation process of MO was carried out using an ultrasonic bath at 42 kHz. The initial MO concentration (pollutant) was 20 mgL−1. Posteriorly, three solutions of Au/Fe3O4/MO at 25, 50 and 75 mgL−1 were prepared. The solutions were placed in the ultrasonic bath. Aliquots of the Au/Fe3O4/MO solutions were collected, and the absorbance was measured by UV–vis in intervals of 1 min until the minimum surface plasmon resonance (SPR) value was observed. All experiments were performed in the dark at room temperature to nullify the photocatalytic reaction. The adsorption kinetic of the MO degradation was described by four models showed in Table 1 [36], [37], [38], [39].

Table 1.

Theoretical adsorption models employed for the calculation of the kinetic parameter in the sonocatalytic degradation of MO.

| Model | Equation | Integrated form |

|---|---|---|

| Pseudo-First Order | ||

| Pseudo-Second Order | ||

| Elovich | ||

| Intraparticle diffusion |

3. Results and Discussion.

3.1. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

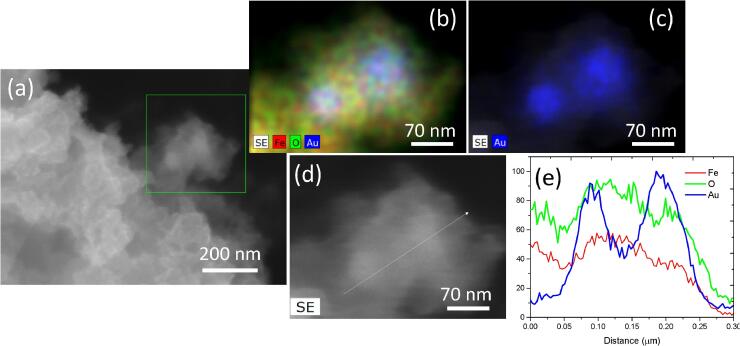

Fig. 2 (a) Shows the morphology of the Au/Fe3O4 nano-alloys obtained by the hybrid green/sonochemical synthesis. In this image, a spherical morphology is appreciated. The observed agglomeration in the sample can be associated presumably with the stearic effect of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles, whose effect is produced by the magnetic interaction between the individual particles. A size distribution particle size approximately of 35 nm can be observed. However, by subsequent analysis of X-ray diffraction (XRD), the crystallite size will be calculated.

Fig. 2.

(a) SEM image of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoalloys obtained, (b) Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS) analysis and (c)-(e) EDS mapping of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles synthesized by sonochemical/ green method. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 2 (b). Shows the Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS) analysis of the Au/Fe3O4 nano-alloys. The main elements identified were Fe, O and Au. Confirming the chemical composition of the Au/Fe3O4 nanostructures. In complementary form, Fig. 2 (c) reveals an SEM image of the Au/Fe3O4 nanostructures obtained by detection of secondary electrons (SE) at high magnification (220 kX). In this figure is possible to appreciate in detail the morphology, size distribution and structure of the Au/Fe3O4 nano-alloys. To identify the location of each element, Fig. 2 (d)-(e), shows an elemental mapping of the sample obtained by EDS. In both images, is possible to identify the Au as a core of the nanostructure, while the Fe and O are situated on the Au surface. This fact indicates presumably, the core–shell type structure formation.

Fig. 3(a)-(c) display an additional EDS mapping of the Au/Fe3O4 nanostructures, while Fig. 3 (d)-(e) show Composition profile obtained by EDS line-scan across the sample, confirming the arrangement of the Au, Fe and O elements, gold in the core and Fe/O on the Au surface.

Fig. 3.

(a)-(c) EDS mapping of the Au/ Fe3O4 nanostructures synthesized by Piper auritum and (d)- (e) EDS line-scan of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles.

3.2. X-Ray diffraction analysis

Fig. 4 (a) shows the XRD pattern of the Au/Fe3O4 nanostructures obtained. Based on the Bragg reflection observed, the crystal structure of the magnetite (PDF# 0019-0629) whit inverse spinel and space Group Fd-3m (2 2 7) was identified. Additionally, intensities consistent with the ccp (cubic close-packed) structure of Au (PDF# 004-0484) and space group: Fm-3m (2 2 5), also were identified. The located predominant intensities, d-spacing, diffraction planes are showed in Table 2.

Fig. 4.

(a) XRD pattern of the Au/Fe3O4 nanostructures obtained by sonochemical activation and (b)-(c) the intensities associated to the planes (Fe3O4-220) and (Au-111) of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles.

Table 2.

XRD Parameter associated to the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles obtained green-sonochemical method.

| 2θ | d-spacing | hkl | Area | FWHM | Shape factor | Max Height |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17.78723 | 4.8219 | Fe3O4 (1 1 1) | 1190.06465 | 8.6247 | 1.77498 | 55.46122 |

| 30.21173 | 2.9571 | Fe3O4 (2 2 0) | 239.20025 | 0.64835 | 0.44965 | 296.35886 |

| 35.58971 | 2.5185 | Fe3O4 (3 1 1) | 864.21665 | 0.639 | 0.70339 | 982.47862 |

| 38.16011 | 2.3515 | Au (1 1 1) | 346.19008 | 0.80786 | 1.04958 | 266.37591 |

| 43.30779 | 2.0925 | Fe3O4 (4 0 0) | 210.97002 | 0.67555 | 0.84157 | 213.79379 |

| 44.39807 | 2.0365 | Au (2 0 0) | 86.93023 | 0.22669 | 2.11608 | 114.52376 |

| 53.67608 | 1.7061 | Fe3O4 (4 2 2) | 490.96835 | 2.9535 | 1.84485 | 63.29905 |

| 57.27823 | 1.6102 | Fe3O4 (5 1 1) | 155.36929 | 0.73323 | −0.16396 | 209.58352 |

| 62.91244 | 1.4802 | Fe3O4 (4 4 0) | 289.67727 | 0.7049 | 0.5022 | 323.56291 |

| 64.46336 | 1.44 | Au (2 2 0) | 195.38711 | 2.07424 | 1.28117 | 51.94736 |

| 74.32472 | 1.2588 | Fe3O4 (5 3 3) | 671.28478 | 3.76323 | 2.11375 | 53.39942 |

| 77.77532 | 1.2281 | Au (3 1 1) | 58.67757 | 1.03287 | 3.21387 | 15.93292 |

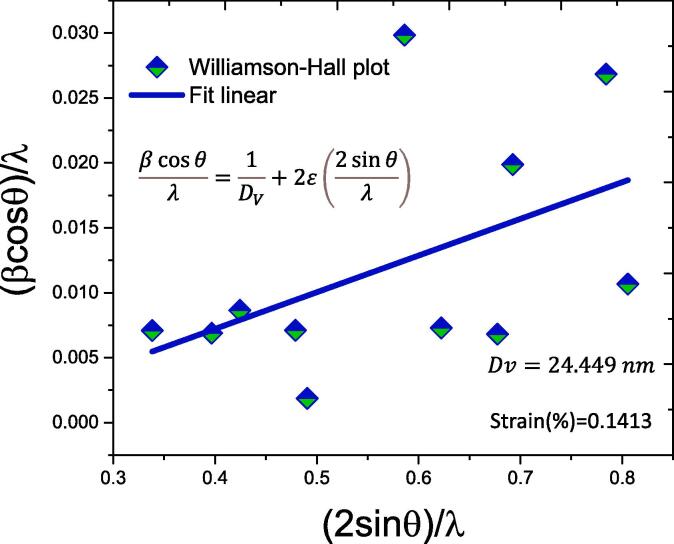

On the other hand, the crystallite size of the Au/Fe3O4 nanostructure was calculated from the experimental XRD pattern employing the Williamson-Hall method. Which in the first stage of the method, consider the full width at half maximum of the peak (FWHM) [40], which were calculated from the XRD data by the Pseudo-Voight function [41], [42], [43] (Table 2.)

| (2) |

where L(x) is the Gaussian curve which are described mathematically as:

| (3) |

And G(x) is the Gaussian curve represented as:

| (4) |

Fig. 4 (b)–(c) displays the intensities associated with the planes (Fe3O4-220)- and (Au −111) respectively. In both figures the Gaussian and Lorentzian part of the Pseudo-Voight function is display

The equation that governs the Williamson-Hall method described as follows:

| (4) |

Graphically, the terms β cosθ/ λ and 2 sinθ/λ, denotes the microstrain and domain size, which are calculated from the slope and intercepts values, respectively [44]. Fig. 5 show the graphically the results of the Williamson-Hall analysis. The crystallite size calculated from this method is 24.44 nm. Which are in good agreement to the particle size observed by SEM.

Fig. 5.

Williamson-Hall plot of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles obtained by green/sonochemical synthesis. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.3. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis.

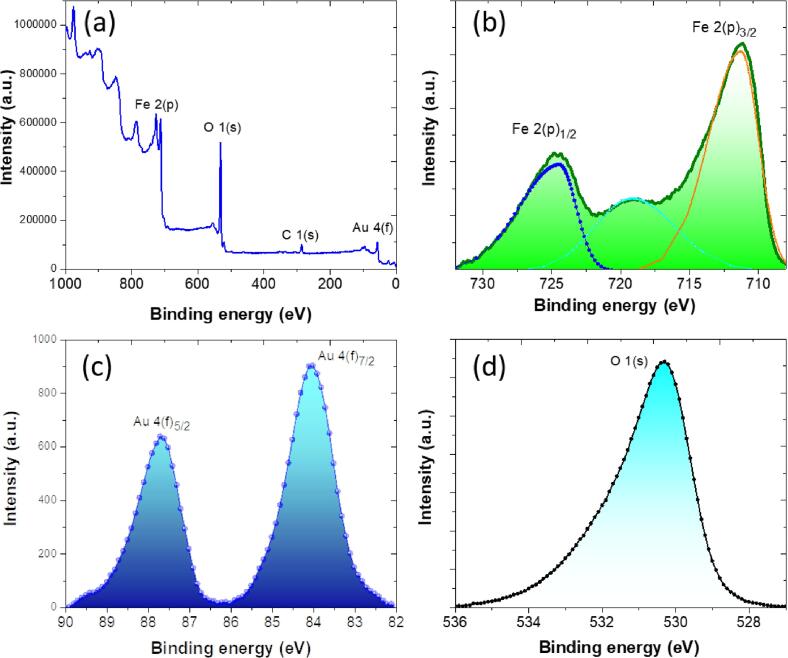

The valence state or electron structures of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles obtained was studied by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Fig. 6 (a) reveals a XPS survey spectra of Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles. In this figure, the Fe 2p, O 1 s and Au 4f signals were fully identified. This result confirms the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles formation and support the structural morphological, chemical and structural characterization presented previously.

Fig. 6.

(a) XPS survey spectra of Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles, HR-XPS spectra of the (b) Fe 2(p), (c) Au 4(f) and (c) O1(s) orbitals.

Fig. 6 (b) presents the HR-XPS spectrum corresponding to the Fe2(p) orbital. The binding energies located at 724.8 and 711.2 eV, are associated to the Fe 2(p)1/2 and Fe 2 (p) 3/2 spin orbitals of magnetite, respectively. Specifically, the energy separation between Fe 2 (p)1/2 and Fe 2p3/2, exhibits a typical value (13.6 eV) attributed the core level signal of Fe3O4[45]

Fig. 6 (c) displays the orbitals of Au (f)3/2 and Au (f)7/2, which were located at 87.8 and 84.1 eV, respectively [4], [5]. Finally, Fig. 6 (d) shows the HR-XPS spectrum of the O 1(s) orbital, presumably associated to the Fe3O4 phase of the sample. The binding energy observed at 530.3 eV corresponds to the O 1(s) orbital. The XPS analysis corroborate and support the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles obtention through the proposed green/sonochemical method.

3.4. Electrochemical characterization of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles by cyclic voltammetry

Fig. 7 Shows the cyclic voltammetry profile of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles, obtained from the −0.6 to 1.5 V at scan rate of 50 mVs−1. The cathodic scan process shows a reduction peak located at 0.3 V, which can be correlated whit Au structure [46], [47]. While a oxidation peak is observed at 0.62 V during the anodic stage, which can be also associated to the Au structure [48].

Fig. 7.

Cyclic voltammograms of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles in acid media and scan rate of 50 mAV−1.

Is important to mentioning, that an oxidation or reduction peak associated to the Fe is not observe. This result indicates presumable, the Au interaction is predominant in the electrochemical behavior of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles synthesized by green methodology. On the other hand, the stability of the sample is pronounced, due that after 9 cycles, the cyclic voltammetry does not exhibit significant variations in potential or current. With the results obtained; the specific capacitance of the material was calculated (Table 3) from the follow equation [46].

| (5) |

where:

is the specific capacitance.

= is the average charge during the charging and discharging process

is the mass of the active materials

Is the potential window

Table 3.

Capacitance specific for each cycle of the cyclic voltammetry of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles (m = 0.001 g, scan rate = 50 mVs−1 and (V2-V1) = 2.1 V).

| Cycle | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (V*mA) | 0.047 | 0.047 | 0.048 | 0.049 | 0.050 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.053 | 0.054 |

| Cp (F/g) | 0.222 | 0.225 | 0.229 | 0.234 | 0.239 | 0.242 | 0.245 | 0.250 | 0.256 |

Regarding to the optical characteristics of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoalloy, Fig. 8 (a) shows a Uv–vis spectrum of the Fe3O4 and Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles. The typical intensity attributed to the surface plasmonic resonance (SPR) of the gold was observed at 535 nm. This fact corroborates the plasmonic nature of the nanoparticles synthesized by sonochemical activation-assisted biosynthesis of Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Fig. 8 (b) display the band gap energy (Eg) which was determined according to the Tauc plot.

Fig. 8.

(a). Uv–vis spectra and (b) Tauc plot of the Fe3O4 and Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles.

The values of band gap for the Fe3O4 and Au/Fe3O4 were 2.64 and 2.77 eV, respectively. Based in these calculations, is possible to affirm that the presence of the Au, increase the band gap value of the material, and consequently, best catalytic properties.

3.5. Magnetic properties of Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles

Fig. 9 display the magnetic hysteresis loops at 10, 100 and 300 K. the magnetic coercivity is nearly zero in the tree temperatures and consequently, a superparamagnetic behavior can be considered. The hysteresis loop at 300 K exhibits a mostly pronounced superparamagnetic behavior [49]. The saturation magnetization observed for the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles are in the range of 51 to 58 emu/g, whose value is inside the average values reported anteriorly. Moreover, the variations in the coercive field as a temperature function can be attributed to the crystallite size or interaction effects between the nanoparticles and/or canted spins at the surface and magnetic anisotropy [13], [50]. However, the variations temperature dependence of the coercive field in the samples at 100 and 300 K it was minimums, in contrast with the sample evaluated at 10 K. Hence, the temperature dependence of the coercive in this case can be attributed to the temperature of the sample.

Fig. 9.

Magnetic hysteresis loop and ZFC/FC curves of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles.

This result suggests that a spin freezing phenomenon is carried out, considering that the particles possess two phases, Au and Fe3O4 and the interaction between the interface of the species (Au/Fe3O4) generate different regions aligned in the spins located the interface and particle surface [3], [49]. Fig. 9 show a ZFC-FC curve (insert) of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles, indicate that the blocking temperature appreciate around 340 K. Hence, at low temperature the disorder of the spin most pronounced. Consequently, at 10 K, coercive field is mayor. The magnetic parameters of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles are insert in the Fig. 9

3.6. Methyl orange sonocatalytic degradation process

In order to determine the behavior of the Au/Fe3O4 nanostructures in the MO Sonocatalytic degradation process, four kinetic adsorption model were employed to describe and calculate the kinetic parameter of the organic dye. Fig. 10 (a)-(d) shows the Pseudo First order, Pseudo Second Order, Elovich and Intraparticle diffusion models plotted from the experimental data collected in MO Sonocatalytic degradation process.

Fig. 10.

Experimental data and kinetics models of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles evaluated on the sonocatalytic degradation of MO, (a) Pseudo-first order, (b) Pseudo-second order, (c) Elovich and (d) Intraparticle diffusion model.

Table 4. Show the kinetic parameters calculated in the sonochemical degradation of methyl orange and correlation factors (R2) obtained from the experimental data obtained in the MO Sonocatalytic degradation process. Based on the results obtained, the best-fitting of the correlation factor R2, is presented for the PSO model associated to the concentration of 25 mg L−1 of Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles. In this sense, is possible to affirm that the Pseudo second order model at lower concentration, describe the MO Sonocatalytic degradation phenomena. In general form, the PSO model suggests an exchange ionic between the adsorbent and the adsorbate and implicitly, a chemisorption process [51], [52].

Table 4.

Kinetic parameters calculated in the sonochemical degradation of methyl orange.

| Au/Fe3O4 NP’s Concentration Kinetic Model |

25 mg L−1 | 50 mg L−1 | 75 mg L−1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lagergren First-Order K1 (min−1) | K1 | R2 | K1 | R2 | K1 | R2 | |||

| 0.0737 | 0.3682 | 0.6082 | 0.9412 | 0.3464 | 0.9342 | ||||

| Pseudo-second Order [K2] (g·mg−1·min−1) |

K2 | H2 | R2 | K2 | H2 | R2 | K2 | H2 | R2 |

| 20.2574 | 0.5383 | 0.9961 | 0.6724 | 0.1244 | 0.8991 | 4.5405 | 0.3516 | 0.7064 | |

| Intraparticle Duffusion Ki (mg·g−1·min−0.5) | Ci | Ki | R2 | Ci | Ki | R2 | Ci | Ki | R2 |

| 0.1854 | 0.0465 | 0.3517 | 0.0079 | 0.1160 | 0.9592 | 0.0059 | 0.0504 | 0.9110 | |

| Elovich α (mg·g−1·min) β (g·mg−1) | α | β | R2 | α | β | R2 | α | β | R2 |

| 1.1571 | 16.0963 | 0.4642 | 0.2912 | 10.9552 | 0.8959 | 0.1130 | 21.4716 | 0.7221 | |

On the one hand, this result suggests that the positive partial charges of the Au/Fe3O4 nanostructures promote the ionic exchange with the MO. The significant interaction between the MO molecule and the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles promotes the chemisorption process. On the other hand, the Sonocatalytic degradation process also favor the MO degradation, due that the ultrasonic waves present in the reaction (aqueous solution) generates reactive radical species such as •OH, which contribute to the degradation of the MO molecule [53], [54]. It is to say, the MO degradation rate increase due to the generation of more hydroxyl radicals. The reaction to generate of hydroxyl radicals from the dissociation of water molecules can described by the follows equations [53], [54], [54], [54], [55], [56], [57]:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

The mechanism sonocatalytic of MO degradation, can be proposed from the follow way. In a first stage, the light and heat produced by the ultrasonic cavitation of the system, produce an excitation in the catalyst, consequently, electron-hole (e − and h + ) pairs are formed on the on the Au/Fe3O4 surface. Posteriorly, the interaction of the electrons on the Au/Fe3O4 surface whit the oxygen molecules produce some active species as •OH, and H2O2 from a series of reactions described in general form as:

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

Finally, the reactive species or hydroxyl groups, promotes the MO degradation molecule, contributing to the decomposition of the –N = N– bonding, given as result the disappearance of orange color in the solution [58], [59]. In others words, the hydroxyl radical interact directly with the –N = N–bond of the MO, given as result the decomposition of the MO in some intermediate products such as N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine and N,N-dimethyl-benzenamine. In the final stage of the process, is possible to obtain sulfanilic acid, carbon dioxide and water. In this sense, the MO sonocatalytic degradation process carried out in the present work, is in concordance with the previous reports [59]. Fig. 11 describe the proposed sonocatalytic mechanism and possible pathway for degradation of methyl orange by Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles.

Fig. 11.

Proposed sonocatalytic mechanism and possible pathway for degradation of methyl orange by Fe3O4/Au nanoparticles. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

It is important to mentioning that by the employ of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles in the sonocatalytic process with the experimental conditions proposed, was possible to achieve a removal percentage of 91.2% at 15 min of the sonocatalytic process (160 W/42 kHz). Is important to mentioning that result obtained were highly competitive in relation to those reported in the literature, considering the simplification and economy of the catalyst synthesis route, as well as the low power of the ultrasound equipment and mainly the short period of time in which the sonocatalytic degradation was carried out. Table 5 shows a comparative table of various catalysts evaluated in different advanced oxidation processes (AOPs). In this sense is possible to affirm, in conclusive form, that the proposed methodology offer the possibility to obtain Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles whit notable magnetic and catalytic properties and consequently, with potential applications and several fields. This fact, represent the main scientific achievement of this work, taking in a count the efficiency of degradation of the material and the simplicity of the synthesis methodology.

Table 5.

Comparative table of various catalysts evaluated in different advanced oxidation processes (AOPs).

| Catalyst | Catalyst Syntheis Route | Pollutant | AOPs | Concentration pollutant | Catalyst Dosage | Ultrasonic Power /Frequency | Reaction Time | Degradation efficiency | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SrTiO3/mpg-C3N4 | Hydrothermal method | Basic violet | Sonocatalysis | 10 mg L−1 | 0.3 g L−1 | 240 W | 120 min | 80% | [11] |

| Ozone | Acid orange 07 (AO7) | Electro-Peroxone (EP) and ultrasound (US) | 50 mg L−1 | 0.33 g L−1 | 100 W/20 kHz/ 300 mA | 30 min | 88% | [12] | |

| CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4 | Thermal decomposition and liquid phase self-assembly method | Methylene blue | Sonocatalysis | 8 mg L−1 | 0.25 g L−1 | 665 W/40 kHz | 45 min | 92.81% | [10] |

| NiFe-LDH/rGO | Hydrothermal method | Moxifloxacin | Sonophotocatalysis | 20 mg L−1 | 1.0 g L−1 | 150 W | 60 min | 90.40% | [14] |

| Tungsten disulfide (WS2) | Sonochemical | Basic violet 10 | Sonocatalysis | 10 mg L−1 | 1.0 g L−1 | 400 W | 150 min | 94.01% | [60] |

| CoFe2O4-rGO | Surfactant assisted high temperature thermal decomposition | AO7, AR17, BR46 and BY28) | Heterogeneous sono-Fenton-like process | 10 mg L−1 | 0.08 g L−1 | 350 W | 120 min | 90.5% (AO7) | [61] |

| Au/ Fe3O4 | Green sonochemical | Methyl orange | Sonocatalytic | 20 mg L−1 | 0.075 g L − 1 | 160 W/42 kHz | 15 min | 91.20% | This work |

| TiO2-MMT | hydrothermal method | Ciprofloxacin (CIP) | Sonocatalysis | 10 mg L−1 | 0.2 g L−1 | 350–650 WL−1 | 120 min | 65.01% | [62] |

| FeCeOx | Precipitation method/calcination | Diclofenac | Sonocatalysis | 20 mg L−1 | 0.5 g L−1 | 3.0 W/cm3 20 kHz | 30 min | 80% | [57] |

| Lantanide- doped ZnO nanoparticles Er-ZnO | Sonochemical | Reactive Orange 29 (RO29) | Sonocatalysis | 10 mg L−1 | 1.0 g L−1 | 150 W/36 kHz | 150 min | 80% | [55] |

| Porous trigonal TiO2 nanoflakes (p-TiO2) | Hydrotermal calcination | Rhodamine B (RhB) | Sonocatalysis | 5 mg L−1 | 0.5 g L−1 | 80 W/40 kHz | 180 min | 81% | [63] |

| Zinc Oxide on Montmorillonite (MMT-ZnO) | Chemical reduction | Naproxen | Sonocatalysis | 10 mg L−1 | 0.5 g L−1 | 650 W/60 kHz | 120 min | 73.60% | [64] |

| Bismuth tungstate Bi2WO6 | hydrothermal method | Methyl Orange MO | Sonocatalysis | 10 mg L−1 | 1.0 g L−1 | 400 W/ 40 kHz | 30 min | 80% | [65] |

| CuS/CoFe2O4 | hydrothermal method | Rhodamine B (RhB) | H2O2/Sonolisys | 25 mg L−1 | 0.5 g L−1 | 100 W/37 kHz | 30 min | 72% | [66] |

| Fe3O4 + H2O2 | rod milling and ball milling | Basic violet 10 (BV10) | heterogeneous sono-Fenton process | 30 mg L−1 | 0.5 g L−1 | 450 WL−1 | 120 min | 75.94% | [13] |

4. Conclusions

The synthesis route proposed offers a greener alternative for the obtention of Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles with significant magnetic and photocatalytic properties. The synthesis based on Piper auritum as reducing agent and assisted by sonication exhibits many advantages under the traditional methodologies. The main advantages of the method are their simple procedure, low or null toxicity, and a low cost. Taking into count the enhanced photocatalytic activity and pronounced magnetic properties of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles. On the other hand, the reduction capacity of the antioxidants species presents in the Piper auritum, make possible the reduction of the metallics salts of Au and Fe. Likewise, the incorporation of ultrasound waves, complementing and favor the reaction due to the generation of reactive radical species during the collapsing of the microbubbles process. Additionally, the ultrasound waves incorporation favors the dissociation of metallic ions in the aqueous solution of the reaction. Given as result a mayor dispersion of nucleation sites for the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Based on the result obtained, is possible to affirm that the catalytic and magnetic properties of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles, can be the starter point for futures studies and application of the Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles obtained by the proposed green sonochemical route. Finally, the ultrasonic waves present sonocatalytic degradation generates reactive radical species such as *OH, which contribute to the degradation of the MO molecule. It is to say, the MO degradation rate increase due to the generation of more hydroxyl radicals.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The author of this work, make manifest their gratitude to the “Cathedras CONACYT” program and the Center of Applied Physics and Advanced Technology belonging to the National Autonomous University of Mexico (CFATA-UNAM) as well as the to the National Materials Characterization Laboratory (LaNCaM).

References

- 1.Dheyab M.A., Aziz A.A., Jameel M.S., Khaniabadi P.M., Mehrdel B. Mechanisms of effective gold shell on Fe3O4 core nanoparticles formation using sonochemistry method. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;64:104865. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fantechi E., Roca A.G., Sepúlveda B., Torruella P., Estradé S., Peiró F., Coy E., Jurga S., Bastús N.G., Nogués J., Puntes V. Seeded Growth Synthesis of Au-Fe3O4 Heterostructured Nanocrystals: Rational Design and Mechanistic Insights. Chem. Mater. 2017;29(9):4022–4035. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b00608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin F.-H., Doong R.-a. Catalytic Nanoreactors of Au@Fe3O4 Yolk-Shell Nanostructures with Various Au Sizes for Efficient Nitroarene Reduction. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2017;121(14):7844–7853. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b00130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thamilselvan A., Manivel P., Rajagopal V., Nesakumar N., Suryanarayanan V. Improved electrocatalytic activity of Au@Fe 3 O 4 magnetic nanoparticles for sensitive dopamine detection. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 2019;180:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song R.-B., Zhou S., Guo D., Li P., Jiang L.-P., Zhang J.-R., Wu X., Zhu J.-J. Core/Satellite Structured Fe3O4/Au Nanocomposites Incorporated with Three-Dimensional Macroporous Graphene Foam as a High-Performance Anode for Microbial Fuel Cells, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020;8(2):1311–1318. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b07059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawan S., Maalouf R., Errachid A., Jaffrezic-Renault N. Metal and metal oxide nanoparticles in the voltammetric detection of heavy metals: A review. TrAC - Trends Anal. Chem. 2020;131:116014. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2020.116014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vijilvani C., Bindhu M.R., Frincy F.C., AlSalhi M.S., Sabitha S., Saravanakumar K., Devanesan S., Umadevi M., Aljaafreh M.J., Atif M. Antimicrobial and catalytic activities of biosynthesized gold, silver and palladium nanoparticles from Solanum nigurum leaves. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2020;202 doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.111713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuentes-García J.A., Santoyo-Salzar J., Rangel-Cortes E., Goya G.F., Cardozo-Mata V., Pescador-Rojas J.A. Effect of ultrasonic irradiation power on sonochemical synthesis of gold nanoparticles. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;70:105274. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bahrani S., Razmi Z., Ghaedi M., Asfaram A., Javadian H. Ultrasound-accelerated synthesis of gold nanoparticles modified choline chloride functionalized graphene oxide as a novel sensitive bioelectrochemical sensor: Optimized meloxicam detection using CCD-RSM design and application for human plasma sample. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;42:776–786. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassani A., Eghbali P., Metin Ö. Sonocatalytic removal of methylene blue from water solution by cobalt ferrite/mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride (CoFe2O4/mpg-C3N4) nanocomposites: response surface methodology approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018;25(32):32140–32155. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eghbali P., Hassani A., Sündü B., Metin Ö. Strontium titanate nanocubes assembled on mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride (SrTiO3/mpg-C3N4): Preparation, characterization and catalytic performance. J. Mol. Liq. 2019;290:111208. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghanbari F., Zirrahi F., Lin K.-Y., Kakavandi B., Hassani A. Enhanced electro-peroxone using ultrasound irradiation for the degradation of organic compounds: A comparative study. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020;8(5):104167. doi: 10.1016/j.jece:2020.104167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hassani A., Karaca C., Karaca S., Khataee A., Açışlı Ö., Yılmaz B. Enhanced removal of basic violet 10 by heterogeneous sono-Fenton process using magnetite nanoparticles. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;42:390–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khataee A., Sadeghi Rad T., Nikzat S., Hassani A., Aslan M.H., Kobya M., Demirbaş E. Fabrication of NiFe layered double hydroxide/reduced graphene oxide (NiFe-LDH/rGO) nanocomposite with enhanced sonophotocatalytic activity for the degradation of moxifloxacin. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;375:122102. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2019.122102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain B., Hashmi A., Sanwaria S., Singh A.K., Susan M.A.B.H., Carabineiro S.A.C. Catalytic Properties of Graphene Oxide Synthesized by a “Green” Process for Efficient Abatement of Auramine-O Cationic Dye. Anal. Chem. Lett. 2020;10(1):21–32. doi: 10.1080/22297928.2020.1747536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khataee A., Sajjadi S., Rahim Pouran S., Hasanzadeh A. Efficient electrochemical generation of hydrogen peroxide by means of plasma-treated graphite electrode and activation in electro-Fenton. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017;56:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jiec.2017.07.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Gisi S., Lofrano G., Grassi M., Notarnicola M. Characteristics and adsorption capacities of low-cost sorbents for wastewater treatment: A review. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2016;9:10–40. doi: 10.1016/j.susmat.2016.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuervo Lumbaque E., Lopes Tiburtius E.R., Barreto-Rodrigues M., Sirtori C. Current trends in the use of zero-valent iron (Fe0) for degradation of pharmaceuticals present in different water matrices, Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2019;24:e00069. doi: 10.1016/j.teac.2019.e00069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roy F., Et Taouil A., Lallemand F., Heintz O., Moutarlier V., Hihn J.Y. Alkanethiol self-assembling on gold: Influence of high frequency ultrasound on adsorption kinetics and electrochemical blocking. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;40:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thari F.Z., Tachallait H., El Alaoui N.-E., Talha A., Arshad S., Álvarez E., Karrouchi K., Bougrin K. Ultrasound-assisted one-pot green synthesis of new N- substituted-5-arylidene-thiazolidine-2,4-dione-isoxazoline derivatives using NaCl/Oxone/Na3PO4 in aqueous media. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;68:105222. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elshikh M.S., Chen T.-W., Mani G., Chen S.-M., Huang P.-J., Ali M.A., Al-Hemaid F.M., Al-Mohaimeed A.M. Green sonochemical synthesis and fabrication of cubic MnFe2O4 electrocatalyst decorated carbon nitride nanohybrid for neurotransmitter detection in serum samples. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;70:105305. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma D., Ledwani L., Mehrotra T., Kumar N., Pervaiz N., Kumar R. Biosynthesis of hematite nanoparticles using Rheum emodi and their antimicrobial and anticancerous effects in vitro. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2020;206 doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2020.111841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samuel M.S., Jose S., Selvarajan E., Mathimani T., Pugazhendhi A. Biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using Bacillus amyloliquefaciens; Application for cytotoxicity effect on A549 cell line and photocatalytic degradation of p-nitrophenol. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2020;202 doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.111642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khodadadi B., Bordbar M., Nasrollahzadeh M. Achillea millefolium L. extract mediated green synthesis of waste peach kernel shell supported silver nanoparticles: Application of the nanoparticles for catalytic reduction of a variety of dyes in water. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;493:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qasim S., Zafar A., Saif M.S., Ali Z., Nazar M., Waqas M., Haq A.U., Tariq T., Hassan S.G., Iqbal F., Shu X.-G., Hasan M. Green synthesis of iron oxide nanorods using Withania coagulans extract improved photocatalytic degradation and antimicrobial activity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2020;204:111784. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2020.111784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruíz-Baltazar Á.d.J. Kinetic adsorption models of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized by Cnicus Benedictus: Study of the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue and antibacterial activity. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020;120:108158. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2020.108158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Á. de J. Ruíz-Baltazar, Green synthesis assisted by sonochemical activation of Fe3O4-Ag nano-alloys: Structural characterization and studies of sorption of cationic dyes. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020;120 doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2020.108148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruíz-Baltazar Á.D.J., Reyes-López S.Y., Mondragón-Sánchez M.D.L., Estevez M., Hernández-Martinez A.R., Pérez R. Biosynthesis of Ag nanoparticles using Cynara cardunculus leaf extract: Evaluation of their antibacterial and electrochemical activity. Results Phys. 2018;11:1142–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2018.11.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de J. Ruíz-Baltazar Á., Méndez-Lozano N., Larrañaga-Ordáz D., Reyes-López S.Y., Zamora Antuñano M.A., Pérez Campos R. Magnetic Nanoparticles of Fe3O4 Biosynthesized by Cnicus benedictus Extract: Photocatalytic Study of Organic Dye Degradation and Antibacterial Behavior. Processes. 2020;8(8):946. doi: 10.3390/pr8080946. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Jesús Ruíz-Baltazar Á., Reyes-López Simón.Y., Larrañaga D., Estévez M., Pérez R. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using a Melissa officinalis leaf extract with antibacterial properties. Results Phys. 2017;7:2639–2643. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2017.07.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de J. Ruíz-Baltazar Á. Green Composite Based on Silver Nanoparticles Supported on Diatomaceous Earth: Kinetic Adsorption Models and Antibacterial Effect. J. Clust. Sci. 2018;29:509–519. doi: 10.1007/s10876-018-1357-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menezes Maciel Bindes M., Hespanhol Miranda Reis M., Luiz Cardoso V., Boffito D.C. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from green tea leaves and clarification with natural coagulants (chitosan and Moringa oleífera seeds) Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;51:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conde-Hernández L.A., Guerrero-Beltrán J.Á. Total phenolics and antioxidant activity of piper auritum and porophyllum ruderale. Food Chem. 2014;142:455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pineda R.M., Vizcaíno S.P., García C.M.P., Gil J.H.G., Durango D.L.R. Chemical composition and antifungal activity RPM. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2012;71:507–515. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aguilar-Urquizo E., Itza-Ortiz M.F., Sangines-Garcia J.R., Pineiro-Vázquez A.T., Reyes-Ramirez A., Pinacho-Santana B. Phytobiotic activity of piper auritum and ocimum basilicum on avian e. Coli, Rev. Bras. Cienc. Avic. 2020;22:1–10. doi: 10.1590/1806-9061-2019-1167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruíz-Baltazar Á.D.J., Reyes-López S.Y., Mondragón-Sánchez M.D.L., Robles-Cortés A.I., Pérez R. Eco-friendly synthesis of Fe<inf>3</inf>O<inf>4</inf> nanoparticles: Evaluation of their catalytic activity in methylene blue degradation by kinetic adsorption models. Results Phys. 2019;12 doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2018.12.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruíz-Baltazar A., Esparza R., Gonzalez M., Rosas G., Pérez R. Preparation and characterization of natural zeolite modified with iron nanoparticles. J. Nanomater. 2015;2015:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2015/364763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruíz-Baltazar A., Reyes-López Simón.Y., Tellez-Vasquez O., Esparza R., Rosas G., Pérez R. Analysis for the Sorption Kinetics of Ag Nanoparticles on Natural Clinoptilolite. Adv. Condens. Matter Phys. 2015;2015:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2015/284518. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernández-Abreu A.B., Álvarez-Torrellas S., Águeda V.I., Larriba M., Delgado J.A., Calvo P.A., García J. Enhanced removal of the endocrine disruptor compound Bisphenol A by adsorption onto green-carbon materials. Effect of real effluents on the adsorption process. J. Environ. Manage. 2020;266:110604. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan H., Yerramilli A.S., D’Oliveira A., Alford T.L., Boffito D.C., Patience G.S. Experimental methods in chemical engineering: X-ray diffraction spectroscopy—XRD. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2020;98:1255–1266. doi: 10.1002/cjce.23747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de J. Ruíz-Baltazar Á. Kinetic adsorption models of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized by Cnicus Benedictus: Study of the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue and antibacterial activity. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2020;120 doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2020.108158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sánchez-Bajo F., Cumbrera F.L. The Use of the Pseudo-Voigt Function in the Variance Method of X-ray Line-Broadening Analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1997;30(4):427–430. doi: 10.1107/S0021889896015464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scardi P., Ermrich M., Fitch A., Huang E.-W., Jardin R., Kuzel R., Leineweber A., Mendoza Cuevas A., Misture S.T., Rebuffi L., Schimpf C. Size–strain separation in diffraction line profile analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2018;51(3):831–843. doi: 10.1107/S1600576718005411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sen R., Das G.C., Mukherjee S. X-ray diffraction line profile analysis of nano-sized cobalt in silica matrix synthesized by sol-gel method. J. Alloys Compd. 2010;490(1-2):515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.10.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amarjargal A., Tijing L.D., Im I.T., Kim C.S. Simultaneous preparation of Ag/Fe3O4 core-shell nanocomposites with enhanced magnetic moment and strong antibacterial and catalytic properties. Chem. Eng. J. 2013;226:243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2013.04.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao G., Liu G. Electrochemical deposition of gold nanoparticles on reduced graphene oxide by fast scan cyclic voltammetry for the sensitive determination of As(III) Nanomaterials. 2019;9(1):41. doi: 10.3390/nano9010041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baghayeri M., Ansari R., Nodehi M., Razavipanah I., Veisi H. Voltammetric aptasensor for bisphenol A based on the use of a MWCNT/Fe3O4@gold nanocomposite. Microchim. Acta. 2018;185 doi: 10.1007/s00604-018-2838-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liang R.P., Yao G.H., Fan L.X., Qiu J.D. Magnetic Fe 3O 4@Au composite-enhanced surface plasmon resonance for ultrasensitive detection of magnetic nanoparticle-enriched α-fetoprotein. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2012;737:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.León Félix L., Coaquira J.A.H., Martínez M.A.R., Goya G.F., Mantilla J., Sousa M.H., Valladares L.D.L.S., Barnes C.H.W., Morais P.C. Structural and magnetic properties of core-shell Au/Fe 3 O 4 nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–8. doi: 10.1038/srep41732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mogomotsi R.N., Akinola S.S., Emeka E.E., Fayemi O.E. Cyclic voltammetry, photocatalytic and antimicrobial comparative studies of fabrication Fe3O4 and Fe3O4/PAN nanofibers. Mater. Res. Express. 2020;7(5):055001. doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/ab8ba1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akram M.Y., Ahmed S., Li L., Akhtar N., Ali S., Muhyodin G., Zhu X.-Q., Nie J. N-doped reduced graphene oxide decorated with Fe 3 O 4 composite: Stable and magnetically separable adsorbent solution for high performance phosphate removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019;7(3):103137. doi: 10.1016/j.jece:2019.103137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wen T., Wang J., Li X., Huang S., Chen Z., Wang S., Hayat T., Alsaedi A., Wang X. Production of a generic magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles decorated tea waste composites for highly efficient sorption of Cu(II) and Zn(II) J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017;5(4):3656–3666. doi: 10.1016/j.jece:2017.07.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sonocatalytic degradation 1 EXCELENTE 7.pdf, (n.d.).

- 54.Sonocatalytic degradation 1 EXCELENTE equations 5.pdf, (n.d.).

- 55.Sonocatalytic degradation 1 EXCELENTE equations 5.pdf, (n.d.). Alireza KhataeeBehrouz VahidShabnam SaadiSang Woo Joo[1–3][4][5,6][7,8][9,10][11,12][8,9]%0A.

- 56.Sonocatalytic degradation 1 EXCELENTE 6.pdf, (n.d.).

- 57.Chong S., Zhang G., Wei Z., Zhang N., Huang T., Liu Y. Sonocatalytic degradation of diclofenac with FeCeOx particles in water. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;34:418–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nguyen C.H., Fu C.C., Juang R.S. Degradation of methylene blue and methyl orange by palladium-doped TiO2 photocatalysis for water reuse: Efficiency and degradation pathways. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;202:413–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xie S., Huang P., Kruzic J.J., Zeng X., Qian H. A highly efficient degradation mechanism of methyl orange using Fe-based metallic glass powders. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep21947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khataee A., Eghbali P., Irani-Nezhad M.H., Hassani A. Sonochemical synthesis of WS2 nanosheets and its application in sonocatalytic removal of organic dyes from water solution. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;48:329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hassani A., Çelikdağ G., Eghbali P., Sevim M., Karaca S., Metin Ö. Heterogeneous sono-Fenton-like process using magnetic cobalt ferrite-reduced graphene oxide (CoFe2O4-rGO) nanocomposite for the removal of organic dyes from aqueous solution. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;40:841–852. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hassani A., Khataee A., Karaca S., Karaca C., Gholami P. Sonocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin using synthesized TiO2 nanoparticles on montmorillonite. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;35:251–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Song L., Zhang S., Wu X., Wei Q. Synthesis of porous and trigonal TiO2 nanoflake, its high activity for sonocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B and kinetic analysis. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2012;19(6):1169–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karaca M., Kiranşan M., Karaca S., Khataee A., Karimi A. Sonocatalytic removal of naproxen by synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles on montmorillonite. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016;31:250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.He L.L., Liu X.P., Wang Y.X., Wang Z.X., Yang Y.J., Gao Y.P., Liu B., Wang X. Sonochemical degradation of methyl orange in the presence of Bi2WO6: Effect of operating parameters and the generated reactive oxygen species. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016;33:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Siadatnasab F., Farhadi S., Khataee A. Sonocatalytic performance of magnetically separable CuS/CoFe2O4 nanohybrid for efficient degradation of organic dyes. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;44:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]