Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) manifests aggressive tumor growth and early metastasis. Crucial steps in tumor growth and metastasis are survival, angiogenesis, invasion, and immunosuppression. Our prior research showed that chemokine CXC- receptor-2 (CXCR2) is expressed on endothelial cells, innate immune cells, and fibroblasts, and regulates angiogenesis and immune responses. Here, we examined whether tumor angiogenesis, growth, and metastasis of CXCR2 ligands expressing PDAC cells are regulated in vivo by a host CXCR2-dependent mechanism. C57BL6 Cxcr2−/− mice were generated following crosses between Cxcr2−/+ female and Cxcr2−/− male. Cxcr2 ligands expressing Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS-PDAC) cells were orthotopically implanted in the pancreas of wild-type or Cxcr2−/− C57BL6 mice. No significant difference in PDAC tumor growth was observed. Host Cxcr2 loss led to an inhibition in microvessel density in PDAC tumors. Interestingly, an enhanced spontaneous and experimental liver metastasis was observed in Cxcr2−/− mice compared with wild-type mice. Increased metastasis in Cxcr2−/− mice was associated with an increase in extramedullary hematopoiesis and expansion of neutrophils and immature myeloid precursor cells in the spleen of tumor-bearing mice. These data suggest a dynamic role of host CXCR2 axis in regulating tumor immune suppression, tumor growth, and metastasis.

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cancer (PDAC) is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death, for which treatment options are limited.1 PDAC progression, metastasis, and therapy resistance involve complex interactions between tumor cells and dynamic tumor microenvironment (TME).2 PDAC tumors are known to contain infiltrates of immune cells that help to suppress the anti-tumor responses.3, 4, 5 Such immune infiltrates, composed of both myeloid and lymphoid lineages, include neutrophils, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), macrophages, and T-regulatory (Treg) cells.5

Chemokine CXC-receptor-2 (CXCR2) and its ligands regulate the growth of the tumor, angiogenesis, and metastasis in various cancers.6, 7, 8, 9 CXCR2 is known to orchestrate immune responses in multiple diseases, including cancer.10, 11, 12 Several studies have confirmed the presence of CXCR2 and its ligands in human PDAC tissues and cell lines.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 In addition to PDAC cells, CXCR2 is expressed on endothelial cells and neutrophils.18, 19, 20 The expression of CXCR2 has also been reported on PDAC fibroblasts21 and is a known mediator of tumor progression, angiogenesis, and metastasis in PDAC.16,22,23 Studies from our group and others show that CXCR2 is expressed on endothelial cells.19,24,25 Cxcr2+ neutrophils are one of the innate immune cell types that originate from the myeloid precursor,26 and play a protumor role in cancer.27,28 Deletion of host Cxcr2 in melanoma and breast cancer leads to inhibition of tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis.9,29,30 However, the role of host Cxcr2 expressed on stromal cells (neutrophils, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells) in PDAC growth and metastasis remains unclear.12,31

Here, we hypothesized that tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis in CXCR2 ligands expressing PDAC cells are regulated by a host stromal Cxcr2-dependent mechanism in the PDAC TME. Syngeneic immunocompetent wild-type (WT) and whole-body Cxcr2 knockout (Cxcr2−/−) mice showed no significant difference in PDAC tumor growth and enhanced spontaneous and experimental liver metastasis in Cxcr2−/− mice compared with WT mice. The deletion of Cxcr2 led to inhibition in microvessel density, in situ cell proliferation, and increased apoptosis in PDAC tumors. Additionally, increased metastasis in Cxcr2−/− mice was associated with an increase in extramedullary hematopoiesis (EMH) and expansion of neutrophils and immature myeloid precursor cells in the spleen of tumor-bearing mice. These data reveal a dynamic role of host CXCR2 axis in regulating pancreatic tumor growth, immune suppression, and metastasis.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

UN-KC-6141 cell line32 [referred to as Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS)-PDAC cells in this study] were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle’s medium (Thermo Scientific, Logan, UT), supplemented with fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch GA), l-glutamine (MediaTech, Manassas, VA), twofold vitamin solution (MediaTech), and gentamycin (Gibco, Life Technologies, New York, NY). KRAS-PDAC-Luc/green fluorescent protein (GFP) cells were generated using pBABE-luciferase enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) retroviruses. Infected GFP-expressing cells used in this study were flow-sorted in the Flow Cytometry Facility at University of Nebraska Medical Center (Omaha, NE). All the cell lines were free of Mycoplasma, as determined by the MycoAlert Plus Mycoplasma Detection kit (Lonza, Rockville, MD) and pathogenic murine viruses. Human DNA Identification Laboratory, University of Nebraska Medical Center, performed the short tandem repeat tests for cell line authentication. Cultures were maintained for no longer than 6 weeks after recovery from frozen stocks.

Animal Models and Details of in Vivo Studies

Mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. All procedures were performed according to institutional guidelines and approved by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

C57BL6 mice heterozygous (+/−) and knockout (−/−) for Cxcr2 were purchased from Charles Rivers (Wilmington, MA). Cxcr2−/− mice were generated using Cxcr2-/+ female and Cxcr2−/− male mice. All colonies were maintained in the pathogen-free transgenic mouse facility at University of Nebraska Medical Center. Genomic DNA was isolated from tail clippings performed on 2- to 3-week–old mice. The tail clippings were digested overnight at 55°C by incubating in 300 μL digestion buffer containing 5 mmol/L EDTA, pH 8.0, 200 mmol/L NaCl, 100 mmol/L Tris, pH 8.0, and 0.2% SDS.33 Genomic DNA was amplified with specific primers for WT Cxcr2 (forward, 5′-GGTCGTACTGCGTATCCTGCCTCAG-3′; reverse, 3′-TAGCCATGATCTTGAGAAGTCCATG-5′) and neomycin resistance gene (forward, 5′-CTTGGGTGGAGAGGCTATTC-3′; reverse, 3′-AGGTGAGATGACAGGAGATC-5′). PCR amplification products were electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose gel containing 0.25 μg/mL ethidium bromide.

Cxcr2-positive UN-KC-6141 cells (2 × 105 cells per mouse) were inoculated orthotopically in the pancreas of WT and Cxcr2−/− mice, male or female, aged 6 to 8 weeks. Mice were euthanized after 4 to 6 weeks and examined for tumor growth and metastasis. A part of the tumor was processed to isolate tumor-associated lymphocytes, and another part was fixed in 10% formalin and processed for histologic analysis.

For the experimental liver metastasis model, 1 × 105 cells were injected intrasplenic per mouse. Moribund mice were euthanized. Splenic primary tumors and liver metastases were removed and processed for histologic analysis.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid kit (Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for murine (m)CXCL2, mCXCL5, and mCXCL7 were performed using a Duoset kit (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), according to the manufacturer's protocol. All experiments were performed in duplicate.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections (4 μm thick) were deparaffinized, antigen was retrieved using sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0), and microwaving for 10 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by incubating with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 30 minutes. After blocking non-specific binding by incubating with serum, slides were probed with primary antibody (Table 1) overnight at 4°C. Slides were washed and appropriate secondary antibodies were added. Immunoreactivity was detected using the ABC Elite Kit and 3,3-diaminobenzidine substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), as per the manufacturer’s protocols. A reddish-brown precipitate indicated positive staining. Nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin. For quantitative evaluation, positive cells were counted from five independent areas.

Table 1.

Antibodies Used for the Study

| Species reactivity | Antibody | Supplier | Catalog no. | Host species | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | Cleaved caspase 3 | Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA) | Asp175 | Rabbit | 1:200 |

| Mouse | Ly6G/Ly6C | Thermo Scientific | MA1-40038 | Rat | 1:50 |

| Mouse | Ki-67 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX) | sc-15402 | Rabbit | 1:50 |

| Mouse | Myeloperoxidase | Abcam (Cambridge, UK) | Ab9535 | Rabbit | 1:100 |

| Mouse | CD31 | Abcam | Ab28364 | Rabbit | 1:200 |

| Mouse | CD44 | Abcam | Ab157107 | Rabbit | 1:500 |

| Mouse | E-cadherin | BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) | 610182 | Mouse | 1:500 |

Flow Cytometry

Multicolored flow cytometry was performed to characterize immune cells isolated from the pancreas and spleens and single-cell suspensions were prepared from freshly isolated spleens by crushing them and passing the mixture through a cell strainer. Immune cells were stained using the following antibodies: anti-CD11b (allophycocyanin); anti-Ly6C (phycoerythrin/Cy7); anti-Ly6G/Ly6C (Alexa Fluor 700); anti-F4/80 (fluorescein isothiocyanate); anti-CD3 (fluorescein isothiocyanate); anti-CD4 (phosphatidylethanolamine); anti-CD8 (antigen-presenting cell); anti-CD25 (Alexa Fluor 700); and anti-CD49b [pan–natural killer; peridinin chlorophyll protein (PErCP)/Cy5.5], all from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). Flow cytometry was performed using BD LSR II (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and data were analyzed with BD FACSDiva software version 8 (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software version 10 (BD Biosciences).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism software version 8.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Significance was determined by nonparametric U-test. For all statistical tests, P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

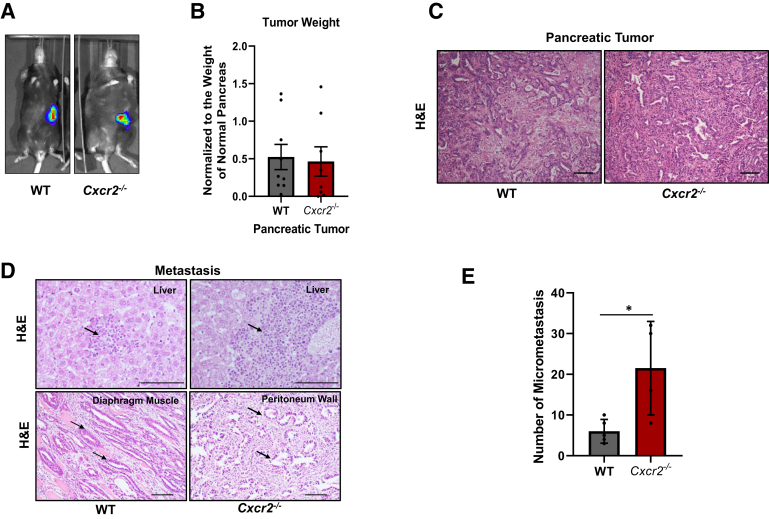

Host Cxcr2 Knockout Do Not Impact Pancreatic Tumor Burden but Enhances Liver Metastasis

The role of host Cxcr2 in regulating pancreatic cancer (PC) tumor growth and metastasis was examined using an immunocompetent orthotopically implanted murine model of PC. KRAS-PDAC cells, derived from the ductal lesions of Pdx1-cre; LSL-Kras(G12D) mice, were orthotopically injected in the pancreas of WT or Cxcr2-depleted mice with a genetic background of C57BL6 mice. These cells express CXCR2 and its ligands at both mRNA and protein levels.16 KRAS-PDAC cells were transduced to express a GFP-firefly luciferase vector. Mice were euthanized after 8 weeks and no change in the tumor weight was observed in the different genotypes (Figure 1, A and B). There was no difference in the tumor incidence (100% and 87.5% in WT and Cxcr2-deleted mice, respectively) or tumor histology (Figure 1C) in mice with different genotypes. Next, PC tumor growth of KRAS-PDAC cells was analyzed using ectopic s.c. implantation into WT and Cxcr2−/− mice. Similar to our earlier observation,15 significant inhibition was observed in tumor burden in Cxcr2−/− mice compared with WT mice (Supplemental Figure S1A). These data demonstrate that Cxcr2−/− deletion impacts PC tumor growth in an organ site-dependent manner.

Figure 1.

The host Cxcr2 deletion does not affect tumor growth but enhances metastasis. A: Intravital luciferase images demonstrating the development of orthotopic tumors in wild-type (WT) and Cxcr2−/− mice inoculated with Kirsten rat sarcoma (KRAS)–pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma–green fluorescent protein cells. B: Graph showing the weight of tumors harvested from WT and Cxcr2−/− mice. Each dot on the graph represents data point from an individual animal. C: Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, showing the histopathology of tumors. D: Representative images of H&E of the liver, peritoneum wall, and diaphragm in WT and Cxcr2−/− mice, demonstrating metastasis. Arrows indicate metastatic cells. E: Graphs showing quantitation of spontaneous micrometastasis in the liver of WT and Cxcr2−/− mice. Cxcr2−/− mice have higher metastasis in the liver in comparison with those in WT mice. Error bars represent SD. Statistical significance determined by U-test. n = 9 WT mice (A); n = 8 Cxcr2−/− mice (A). ∗P < 0.05. Scale bars = 100 μm (C and D).

Next, the role of host Cxcr2 was examined in spontaneous pancreatic cancer (PC) metastasis. Tissues from organs such as liver, peritoneum, and diaphragm were examined in WT and Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing mice for the presence of macrometastasis. Both WT and Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing mice showed metastasis in the liver, peritoneum, and diaphragm (Figure 1D). Interestingly, there was a significant increase of micrometastases in livers (P = 0.0397) of Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing mice compared with those in WT tumor-bearing mice (Figure 1E).

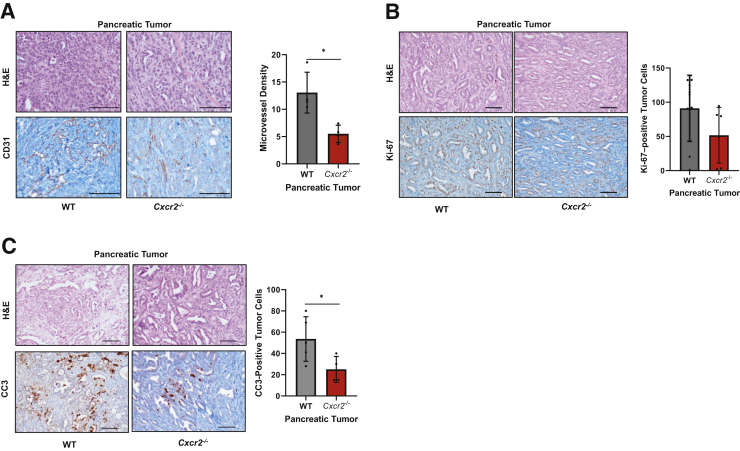

Host Cxcr2 Knockout Decreases Angiogenesis in Tumors of Cxcr2−/− Mice

To understand the impact of Cxcr2−/− on pancreatic tumor growth and metastasis, neoangiogenesis, in situ cell proliferation, and apoptosis were examined. Microvessel density was examined by performing immunohistochemistry (IHC) using CD31 antibody. Our data demonstrate that tumors from Cxcr2−/− mice had significantly lower microvessel density (P = 0.0286) compared with tumors from WT mice (Figure 2A). Next, IHC for Ki-67 (cell proliferation) and cleaved caspase 3 (apoptosis) was performed on tumors derived from KRAS-PDAC–GFP-bearing WT and Cxcr2−/− mice. The staining was quantified to evaluate the proliferation and apoptosis index. Our data demonstrate a decrease in the proliferation index in the WT versus Cxcr2−/− mice (Figure 2B). Cxcr2−/− mice tumors demonstrated increased apoptosis compared with the WT group (Figure 2C). In addition, similar to our previous report,34 decreased microvessel density and in situ cell proliferation was observed in KRAS-PDAC tumors implanted subcutaneously into Cxcr2−/− mice compared with that in WT mice (Supplemental Figure S1, B and C).

Figure 2.

Host Cxcr2 deletion inhibits microvessel density, in situ cell proliferation, and enhanced apoptosis. Representative photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, along with corresponding CD31 (A), Ki-67 (B), and cleaved caspase 3 (CC3; C) immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining, and graphs representing quantitation of each IHC stain. Each dot on the graph represents data point from an individual animal. Error bars represent SD. Statistical significance determined by U-test. ∗P < 0.05. Scale bars = 100 μm (A–C). WT, wild type.

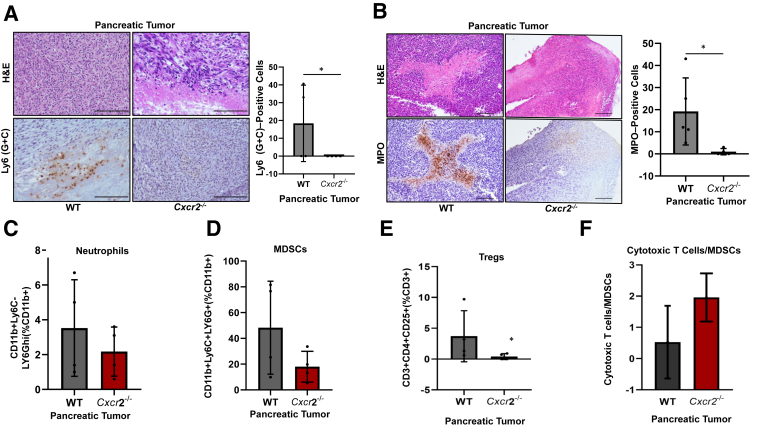

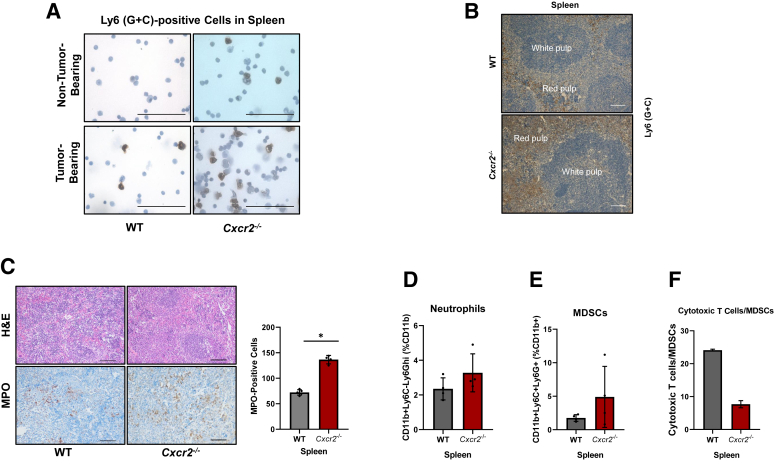

Depletion of Host Cxcr2 Impairs Recruitment of Neutrophils and Immature Myeloid Precursor Cells in the Pancreatic Tumor

Assessment of myeloid cells by immunohistochemistry of Ly6 (G + C) markers on tumors from WT and Cxcr2−/− mice indicated a decrease in myeloid cell population in Cxcr2−/− mice in comparison with that in WT mice (Figure 3A). To further distinguish this population, flow cytometry was used to analyze neutrophil [CD11b+Ly6C−Ly6Ghi (%CD11b+)] and macrophage [F480+ (%CD11b+)] cell populations in the tumors of WT and Cxcr2−/− mice and immunohistochemistry was used for myeloperoxidase (MPO)-positive neutrophil cells on tumors derived from WT and Cxcr2−/− mice. There was a significant decrease (P = 0.0159) in MPO-positive neutrophils in tumors of Cxcr2−/− mice in comparison with the tumors of WT mice (Figure 3B). Similarly, flow cytometry analysis of CD11b+Ly6C−Ly6Ghi (%CD11b+) marker for neutrophil showed a decrease in the percentage of neutrophils in the tumors derived from Cxcr2−/− mice in comparison with the tumors derived from WT mice (Figure 3C). However, there was no change in the F480+ (CD11b+) macrophages in the tumor of Cxcr2−/− and WT mice (Supplemental Figure S2A). Additionally, tumors from Cxcr2−/− mice had fewer immature myeloid cells [CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6C+ (%CD11b+)] positive for both Ly6G and Ly6C marker in comparison with those in the WT tumors (Figure 3D). These immature myeloid cells can be immunosuppressive and are referred to as MDSCs. Together, our data suggest that loss of host CXCR2 axis hinders the recruitment of neutrophils and immature myeloid cell population to the tumors.

Figure 3.

The frequency of myeloid cells in the pancreas of tumor-bearing wild-type (WT) and Cxcr2−/− mice. A and B: Representative photomicrographs demonstrating hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining, and their quantitation for Ly6 (G + C)–positive myeloid cells (A) and myeloperoxidase (MPO)–positive neutrophils (B) in the tumors of WT and Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing mice. Each dot on the graph represents data point from an individual animal. Error bars represent SD. Statistical significance determined by U-test. C–E: Effect of Cxcr2 deletion on the percentage of neutrophils [CD11b+Ly6C−Ly6Ghi (%CD11b+) as determined by flow cytometry; C], myeloid-derived suppressor cells [MDSCs; CD11b+Ly6C+Ly6G+ (%CD11b+); D], and T-regulatory (Treg) cells [CD3+CD4+CD25+ (%CD3+); E] in the pancreas of WT and Cxcr2−/− mice. F: Bar graph comparing the ratios of cytotoxic T cells/MDSCs in the pancreas of tumor-bearing WT and Cxcr2−/− mice. Each dot on the graph represents a data point from an individual animal. Error bars represent SD. Statistical significance determined by U-test. ∗P < 0.05. Scale bars = 100 μm (A and B).

Host Cxcr2 deletion in the immunosuppressive reg-cell–like population [CD3+CD4+CD25+ (%CD3+)] resulted in a lower frequency of immunosuppressive Treg-cell–like population in the tumor from Cxcr2−/− mice as compared with that in WT mice (Figure 3E). However, no significant changes were seen in the cell population of T cytotoxic [CD3+CD4−CD8+ (%CD3+)] cells and T helper cells [CD3+CD4+CD25− (%CD3+)] (Supplemental Figure S2, B and C) in the tumor of Cxcr2−/− and WT mice. Furthermore, there was a small increase in the ratio of cytotoxic T cells [CD3+CD4−CD8+ (%CD3+)] to MDSCs [CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6C+ (%CD11b+)] in the tumors of Cxcr2−/− mice compared with that in the WT mice (Figure 3F). Together, a decrease in neutrophils and immunosuppressive Treg cells and an increase in cytotoxic T cell/MDSC ratio suggest enhancement of anti-tumor immunity in tumors of Cxcr2−/− mice compared with that in WT mice.

Host Cxcr2 Depletion Does Not Alter Tumor Cell Stemness or Epithelial Characteristics

To gain mechanistic insight into enhanced metastasis, stem cell marker CD44 and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition marker E-cadherin were evaluated in the tumors of WT and Cxcr2−/− mice using immunohistochemistry. There was no difference in immunostaining of either CD44 (Supplemental Figure S3A) or E-cadherin (Supplemental Figure S3B) in the tumors of WT and Cxcr2−/− mice.

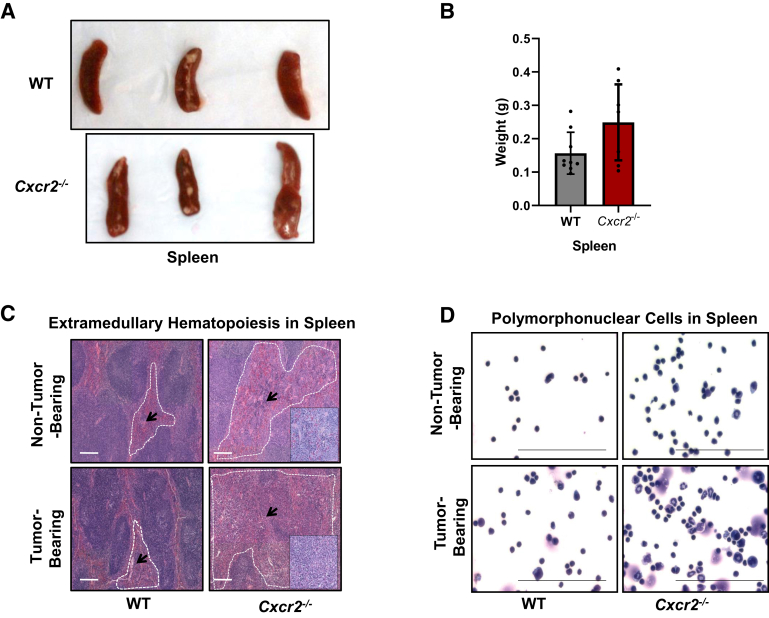

Increased EMH and Accumulation of Neutrophils and Immature Myeloid Precursor Cells in the Spleens of Tumor-Bearing Cxcr2−/− Mice

In the next set of experiments, spleens, reservoirs for tumor-associated immune cells, and EMH were examined in the WT tumor-bearing and Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing mice. Gross evaluation of spleens derived from tumor-bearing mice demonstrated increased spleen size and weight (Figure 4, A and B) in the Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing mice versus the WT tumor-bearing mice. Histopathologic evaluation of hematoxylin and eosin–stained spleens of tumor-bearing mice showed higher EMH in the spleens of Cxcr2−/− mice versus the WT genotype (Figure 4C). Furthermore, WT and Cxcr2−/− mice showed differences in the ratios of the expanding populations (Table 2). Inside the follicular zone in the spleens of WT tumor-bearing mice, the ratio of myeloid/erythroid and lymphoid precursors was 1:3. However, in Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing mice, the follicular zones showed much higher expansion of myeloid precursor cells, with a myeloid/erythroid and lymphoid precursor ratio of 3:1 (Table 2). Hema 3 staining on splenocytes demonstrated an enhanced accumulation of polymorphonuclear cells in the spleens of Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing mice in comparison with the WT tumor-bearing group. Non–tumor-bearing Cxcr2−/− mice also had more polymorphonuclear cells than the WT mice (Table 2). However, their accumulation was highest in the tumor-bearing Cxcr2−/− group (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Splenomegaly and extramedullary hematopoiesis in the spleens of tumor-bearing Cxcr2−/− mice. A: Representative images of spleens resected from tumor-bearing wild-type (WT) and Cxcr2−/− mice. B: Graph demonstrating increased spleen weight in the tumor-bearing Cxcr2−/− mice versus the WT group. Each dot on the graph represents a data point from an individual animal. C: Representative images of histopathologic evaluation of hematoxylin and eosin–stained spleens of non–tumor-bearing and tumor-bearing mice showing higher extramedullary hematopoiesis (EMH) in the spleens of Cxcr2−/− mice versus the WT genotype. Follicular zones are marked with white dashed lines. Arrows indicate EMH. Insets show EMH at higher magnification. D: Representative images of Hema 3 staining of cytospins prepared from the splenocytes of WT and Cxcr2−/− non–tumor-bearing and tumor-bearing mice. Scale bars = 100 μm (C and D).

Table 2.

EMH in Spleens of Cxcr2−/− Tumor-Bearing Mice

| Spleen and sample ID | EMH score | Ratio of myeloid/erythroid and lymphoid precursors |

|---|---|---|

| WT and non–tumor bearing | 0–1 | 1:8 |

| Cxcr2−/− and non–tumor bearing | 2–3 | 1:2 |

| WT and tumor bearing | 2 | 1:3 |

| Cxcr2−/− and tumor bearing | 4 | 3:1 |

Histopathologic evaluation of hematoxylin and eosin–stained spleens of tumor-bearing mice showed higher EMH in the spleens of Cxcr2−/− mice versus the WT genotype. The extent of EMH was independently evaluated by two pathologists and scored from 0 to 4 (0 for no EMH to 4 for highest EMH). The ratio of myeloid/erythroid and lymphoid precursors inside the follicular zone was analyzed.

EMH, extramedullary hematopoiesis; ID, identifier; WT, wild type.

Alterations in the frequencies of Ly6 (G + C)–positive populations inside the spleens of Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing hosts were also observed. IHC for Ly6 (G + C) on splenocytes indicated an increased number of Ly6 (G + C)–positive cells in Cxcr2−/− non–tumor-bearing mice and tumor-bearing hosts (Figure 5A). These cells were localized in spleen by performing Ly6 (G + C) IHC and Ly6 (G + C) cells were observed in the red pulp (Figure 5B). To further characterize this myeloid population, IHC for MPO (a marker for neutrophils) was performed on the spleens of tumor-bearing WT and Cxcr2−/− mice (Figure 5C). A significantly enhanced accumulation (P = 0.0159) of MPO-positive cells was observed inside the spleens of Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing hosts (Figure 5C). This observation was further confirmed by performing flow cytometry analysis for neutrophils using the CD11b+Ly6C−Ly6Ghi (%CD11b+) marker. An increase in the number of neutrophils was observed in the spleens of Cxcr2−/− mice in comparison with those of the WT mice (Figure 5D). Screening for immature myeloid cells (positive for both Ly6G and Ly6C marker) or possible MDSC population in the spleen was done by using CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6C+ (%CD11b+) gate and an increase in immature myeloid cells in the spleen of Cxcr2−/− mice compared with the WT mice spleen was observed (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Increased accumulation of neutrophils and immature myeloid precursor cells in the spleens of tumor-bearing Cxcr2−/− mice. A: Representative photomicrographs demonstrating immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for Ly6 in cytospins prepared from splenocytes of wild-type (WT) and Cxcr2−/− non–tumor-bearing and tumor-bearing mice. B: Ly6 in the red pulp of spleens of WT and Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing mice. C: Representative photomicrographs of immunohistochemical staining for myeloperoxidase (MPO), showing marked neutrophils in the spleens of Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing mice, and graphs depicting the quantitation of myeloperoxidase IHC stain. Each dot on the graph represents data points from an individual animal. Error bars represent SD. Statistical significance determined by U-test. D and E: Flow cytometry analysis for the evaluation of the percentage of neutrophils (D) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs; E) inside the spleens of WT and Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing mice. F: Bar graph showing the ratios of cytotoxic T cells/MDSCs in the spleen of tumor-bearing WT and Cxcr2−/− mice. Each dot on the graph represents data point from an individual animal. Error bars represent SD. ∗P < 0.05. Scale bars: 100 μm (A–C). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

However, flow cytometry using the F4/80+ (CD11b+) marker indicated no change in macrophages (Supplemental Figure S4A) in the spleen of Cxcr2−/− and WT mice. Evaluation of the effect of Cxcr2 deletion on the immunosuppressive Treg cell population [CD3+CD4+CD25+ (%CD3+)], T cytotoxic cells [CD3+CD4−CD8+ (%CD3+)], and T helper cells [CD3+CD4+CD25− (%CD3+)] (Supplemental Figure S4B–D) indicated a slight decrease in Treg population, a decrease in T cytotoxic cells, and no change in T helper cells in the spleen of WT and Cxcr2−/− mice. Lastly, contrary to our observation in the pancreatic tumors of WT and Cxcr2−/− mice, reduced cytotoxic T cell/MDSC ratio was observed in the spleens of Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing hosts (Figure 5F). These results suggest that Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing hosts have a peripheral accumulation of neutrophils and immature myeloid precursor cells.

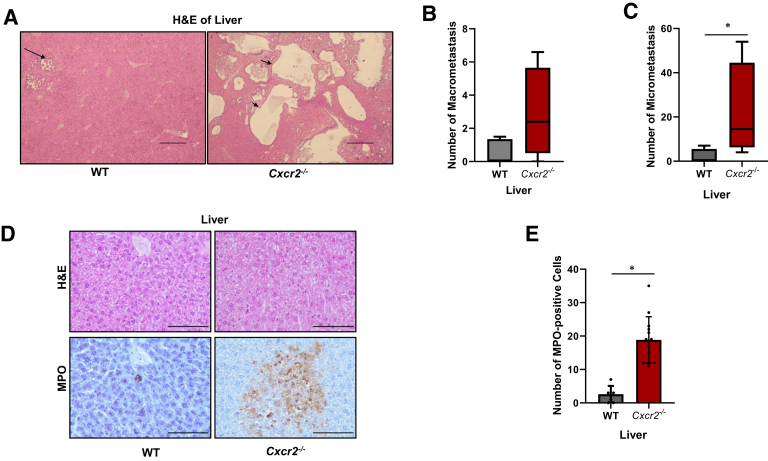

Depletion of Host Cxcr2 Enhances the Accumulation of Neutrophils in the Liver, Resulting in the Generation of a Premetastatic Niche

To further confirm the observation of enhanced metastasis with loss of host Cxcr2, an experimental metastasis model was used in which KRAS-PDAC cells (25 × 104) were injected into the spleens of WT or Cxcr2−/− mice and liver metastasis was evaluated after 4 weeks. Quantitation of macrometastases indicated that Cxcr2−/− mice developed a higher number of macrometastatic and micrometastatic lesions compared with the WT mice (Figure 6A–C).

Figure 6.

Host Cxcr2 deletion enhanced experimental metastasis by generating a premetastatic niche inside the livers with the accumulation of neutrophils. A: Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of livers, demonstrating metastatic lesions in the livers. Arrows indicate metastatic lesions. B and C: Graphs showing quantitation of macrometastasis and micrometastasis in wild-type (WT) and Cxcr2−/− mice. Error bars represent SD. Statistical significance determined by U-test. D and E: Representative images showing immunohistochemistry of myeloperoxidase (MPO) and graph showing quantitation of increased accumulation of MPO-positive cells inside the livers of Cxcr2−/− hosts. Statistical significance determined by U-test. ∗P < 0.05. Scale bars: 500 μm (A); 100 μm (D).

Next, immune cell phenotype was analyzed in the metastatic tumors to define the underlying mechanism(s) for increased liver metastasis in the Cxcr2−/− mice. Statistically significant higher accumulation of MPO-positive neutrophils (P < 0.0001) in the livers of Cxcr2−/− mice in comparison with livers of WT mice, suggested a generation of the premetastatic niche (Figure 6, D and E).

Levels of CXCR2 ligands were also evaluated in the serum of tumor-bearing WT and Cxcr2−/− mice to explain the enhanced recruitment of neutrophils in the liver. While there was no change in the levels of mCXCL5 and mCXCL7 (Supplemental Figure S5, A and B), mCXCL2 level was up-regulated in the serum of Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing mice in comparison with that in the WT tumor-bearing mice (Supplemental Figure S5C). These findings suggest that increased levels of CXCL2 ligand might aid the migration of tumor cells (with intact CXCR2 expression) to livers with premetastatic niche and settlement of tumor cells at the secondary site.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate the role of host Cxcr2-expressing stromal cells in PDAC growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Deletion of host Cxcr2 did not reduce the primary tumor burden but increased liver metastasis. Interestingly, Cxcr2 knockout led to inhibition in microvessel density, in situ cell proliferation, and increased apoptosis in PDAC tumors. More importantly, increased liver metastasis in Cxcr2−/− mice was associated with an increase in extramedullary hematopoiesis and expansion of neutrophils and immature myeloid precursor cells in the spleen of tumor-bearing mice.

Our results show that host Cxcr2 deletion did not affect the size of orthotopic PDAC tumors. On the contrary, significant inhibition in tumor growth in PDAC implanted subcutaneously in Cxcr2−/− mice compared with WT mice was observed. Thus, our data suggest that orthotopic implantation and s.c. implantation of KRAS-PDAC cells into WT and Cxcr2−/− mice have a differential effect on tumor growth. The s.c. implantations lack the TME, and they parallel the growth of cells in vitro in an incubator. However, orthotopic implantations encounter the right surrounding microenvironment with pancreatic cells such as fibroblasts, endothelial cells, immune cells, and others. Apart from tumor cells, most cells present in the TME are positive for the expression of CXCR2. Thus, CXCR2 deletion may impact tumor growth in an organ site-dependent manner. Prior reports have shown that inhibiting Cxcr2 in the tumor-bearing host can either promote or inhibit the growth of PDAC tumors.17,34 Treatment with a neutralizing anti-mouse CXCR2 antibody significantly reduced tumor volume, proliferation, and angiogenesis in an orthotopic xenograft mouse model of PDAC.34 Li et al34 showed that orthotopic inoculation of syngeneic cells in mice with a Cxcr2-deficient background led to reduced tumor volume when implanted subcutaneously. Hertzer et al35 observed larger tumors in Cxcr2−/− mice versus those in the WT mice, in addition to larger tumors in an orthotopic xenograft rodent model treated with the CXCR2 antagonist reparixin.35 Moreover, depletion of Cxcr2 in the LSL-KrasG12D/+;LSL-Trp53R172H/+;Pdx-1-Cre (KPC) mouse model was found not to affect primary tumor growth.36 However, the use of the GFP-luciferase–tagged PDAC-6141 cell line has its limitations. It has been shown that immunogenicity and cytotoxicity of GFP-tagged cells potentially confound the interpretation of in vivo experimental data.37

The CXCR2 signaling axis has been shown to mediate angiogenesis in various cancers, including PDAC. Despite no difference in primary tumor burden, we observed significant inhibition in microvessel density in PDAC tumors in Cxcr2−/− mice compared with that in WT mice. Wente et al38 were the first to demonstrate the role of blockade of CXCR2 in inhibiting pancreatic cancer cell-induced angiogenesis. They evaluated angiogenesis induced by culture supernatants of PDAC cell lines in vivo using the corneal micropocket assay.38 Li et al34 reported that tumor-bearing Cxcr2−/− mice demonstrated a reduction in the levels of bone marrow–derived endothelial progenitor cells in the bone marrow and blood. Congruent with this observation, they showed that CXCR2 knockout reduced the proliferation and capillary tube formation of bone marrow–derived cells in vitro.34 However, the overall impact of reduced angiogenesis on tumor progression is hard to predict as PC is known to be hypovascular.39

Neutrophils and MDSCs are known to express CXCR2, and several studies have elaborated on the role of the CXCR2 signaling axis in MDSC trafficking in various cancers, including breast,11 colon,40 and rhabdomyosarcoma.41 We observed lower recruitment of neutrophils and immature myeloid precursor cells to the tumors of Cxcr2−/− hosts and their expansion in the spleen. This, in addition to the accumulation of neutrophils and MDSCs in the spleen, represents a protumor or immunosuppressive microenvironment, leading to higher metastasis with intrasplenic injected cancer cells. This is further supported by a recent report by Highfill et al41 also demonstrating that Cxcr2 deficiency inhibited the granulocytic MDSC trafficking to the tumors in murine rhabdomyosarcoma, resulting in their compensatory accumulation in the spleens and bloodstream. The authors further concluded that CXCR2+ granulocytic MDSCs mediate local immunosuppression, and inhibiting CXCR2 signaling can enhance the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors.41 However, they did not observe metastasis in their model. We observed no effect of host Cxcr2 ablation on the recruitment of macrophages, as is also seen in previous reports demonstrating no effect of Cxcr2 activation on monocyte chemotaxis.42 On the other hand, Han et al43 recently showed that loss of Cxcr2 signaling reduces the number of macrophages, dendritic cells, and monocytic MDSCs in melanoma tumors, indicating that different tumor types recruit different populations of myeloid cells.

One of the key findings of this study was enhanced EMH, resulting in the accumulation of neutrophils in the spleens of Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing mice compared with those in WT mice, suggesting that host Cxcr2 deficiency leads to systemic immunosuppression. In cancer patients, EMH persists and is essential for the increased demand of tumor-associated lymphocytes.44 A recent report demonstrated that splenectomy could delay lung tumor growth in the K-rasLSL-G12D/+;p53fl/fl (KP) mouse model,44 suggesting extramedullary stem and progenitor cells as targets of drug therapy.44 EMH can result from the switching of dormant hematopoietic precursor stem cells in the spleens or can be a secondary phenomenon following the filtration of hematopoietic precursor cells into the spleens.45

Cxcr2−/− mice have been shown to have an expansion of myeloid progenitor cells in spleens, blood, and bone marrow.46, 47, 48 Accumulation of immature myeloid cells inside the host is known to contribute to immune evasion, resulting in increased metastasis.49 We observed increased accumulation of immature myeloid cells and neutrophils in both spleens and livers of Cxcr2−/− mice with increased spontaneous and experimental metastasis. These results provide a plausible explanation for enhanced liver metastasis. However, Cxcr2 is also expressed by various cells in the TME, such as endothelial cells, myeloid cells, stromal cells, and others. Thus, multiple factors, in addition to a lack of Cxcr2 in the liver organ, could prepare the liver for the pancreatic cancer cells. One possible explanation for our observation is that, in Cxcr−/− mice, there is enhanced secretion of Cxcr2 ligands with IL-17/granulocyte colony-stimulating factor activation.50 These enhanced Cxcr2 ligands, such as CXCL1, can enhance the recruitment of neutrophils in the liver, generating a premetastatic niche.51,52 Multiple recent studies52, 53, 54 and experts55 suggest that accumulation of neutrophils is the first step that leads to the generation of premetastatic niche similar to what we observed in the livers of mice with Cxcr2 deletion. Recently, Cxcr2 ligands have also been shown to induce neutrophil extracellular traps,56 which, in turn, can activate and proliferate dormant cancer cells.57 Thus, Cxcr2 deletion may be more efficient in enhancing metastasis niche formation in different organs by perturbing neutrophil influx rather than strengthening the selectivity of tumor products.

Increased spontaneous and experimental liver metastasis was observed in Cxcr2−/− host mice. However, Steele et al showed that genetic depletion of Cxcr2 in the KPC model of PC significantly inhibited metastasis.36 Since Steele et al36 used a model system with mutant KRAS and nonfunctional p53 in the pancreas along with host Cxcr2 deletion, the observed discrepancies might be explained due to the different models used in these studies. Similarly, Sano et al58 demonstrated reduced cell invasion and migration of pancreatic cancer cells in heterozygous Cxcr2 background with pancreas-specific oncogenic KRAS and knockout of transforming growth factor-β receptor type II. Further investigations using genetic models of PDAC and manipulation of Cxcr2 expression to determine the outcome of host Cxcr2 on PDAC metastasis are ongoing.

We observed a decrease in neutrophils, an increase in the ratio of cytotoxic T cells/MDSCs in the pancreas, and a lower frequency of immunosuppressive Treg cells, suggesting enhancement of anti-tumor immunity in tumors of Cxcr2−/− mice compared with that in the WT mice. Literature suggests that Treg cells can be induced and differentiated by traditional T cells to suppress immune response. The observed antitumor immunity in tumors implies that the unchanged traditional T-cell populations (T helper cells and T cytotoxic cells) and a decrease in neutrophils do not signal Treg induction and differentiation inside the tumor.59, 60, 61, 62, 63 Conversely, in spleens, the ratio of cytotoxic T cells to MDSCs was reduced. Clark et al4 provide direct evidence for the role of MDSCs in regulating T-cell responses by demonstrating that lack of tumor-infiltrating effector T cells strongly correlated with the presence of intratumoral MDSCs. Additionally, MDSCs cause indirect immunosuppression by promoting the recruitment of Treg cells and by blocking the entry of effector T cells to the tumor sites.64 Immature myeloid population or MDSCs suppress the proliferation and activation of T cells by inhibiting the expression of major histocompatibility complex class II on antigen-presenting cells65, 66, 67, 68 and CD3-ζ chains on T cells, respectively, primarily by the production of inducible nitric oxide synthase and arginase 1.69, 70, 71 However, in the peripheral tissues, MDSCs function as antigen-presenting cells and induce reactive oxygen species–mediated T-cell suppression during the antigen-specific interaction between MDSCs and T cells.69 However, it remains unclear whether neutrophils or immature myeloid populations present in PDAC tumors suppress T-cell functionality. Therefore, the role of neutrophils or immature myeloid precursor populations in the immune suppression of the Cxcr2−/− hosts needs further investigation.

Higher metastasis in our model led us to evaluate epithelial marker E-cadherin and cancer stemness marker CD44. Unfortunately, we did not observe any difference in E-cadherin or CD44 expression between tumors of WT mice and Cxcr2−/− mice. Exploration of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition markers such as N-cadherin, Snail, and Twist, as well as different cancer stemness markers in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and induction of stem cell–like property, may explain our observation of increased metastasis. However, delineating the ligand-receptor interaction that mediates the recruitment of neutrophils to the liver needs further evaluation.

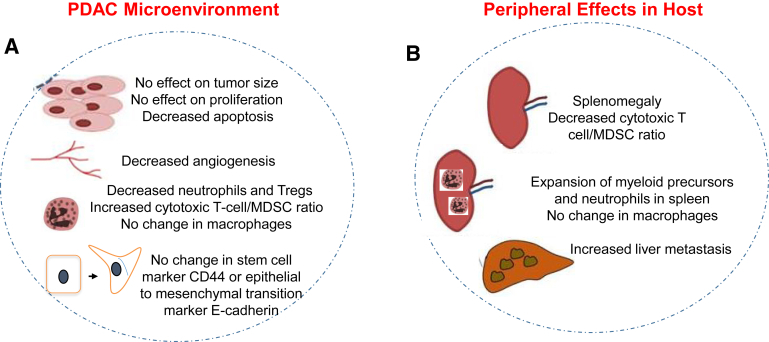

Collectively, our data reveal the dynamic roles of Cxcr2 in mediating host responses during the development of the PDAC. We demonstrate that Cxcr2 is essential for the migration of neutrophils from the spleens to the tumors in the PDAC. Additionally, we also show that host Cxcr2 knockout causes the systemic expansion of neutrophils in the spleens of tumor-bearing hosts. Thus, our data suggest the presence of mechanism(s) that compensate for the anti-tumor effect caused by inhibition in angiogenesis and reduced infiltration of neutrophils to the PDAC tumors in Cxcr2−/− hosts (Figure 7). Increased metastasis in Cxcr2−/− mice was associated with an increase in extramedullary hematopoiesis and systemic immunosuppressive microenvironment in the spleen of tumor-bearing mice. Further experimentation in an advanced model system may help in defining the role of Cxcr2 signaling in pancreatic cancer progression and metastasis.

Figure 7.

Diagrammatic representation of the effect of depletion of Cxcr2 signaling on pancreatic cancer. A: Host Cxcr2 deletion does not effect the overall tumor burden despite enhanced apoptosis in the tumors. Angiogenesis is significantly inhibited in the tumors of Cxcr2−/− hosts. B: Host Cxcr2 depletion results in enhanced metastasis to livers. Peripheral accumulation of immature myeloid cells inside the enlarged spleens of Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing hosts may result in immune evasion. MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; Treg, T regulatory.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grant R01 CA228524 (R.K.S.) and University of Nebraska Medical Center Predoctoral Fellowships (A.P. and S.S.).

A.P. and S.S. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2021.01.002.

Supplemental Data

The deletion of host Cxcr2 inhibits s.c. tumor growth angiogenesis and in situ cell proliferation. Bar graph demonstrating inhibition in the tumor growth (A), cell proliferation (B), and angiogenesis (C) in the s.c. tumors of wild-type (WT) and Cxcr2−/− mice. Statistical significance determined by U-test. ∗P < 0.05.

Effect of host Cxcr2 deletion on the frequency of macrophages, cytotoxic T cells, and T helper cells in the pancreas of tumor-bearing mice. Bar graph demonstrating changes on the percentages of macrophages [F480+ (%CD11b+); A], cytotoxic T cells [CD3+CD4–CD8+ (%CD3); B], and T helper cells [CD3+CD4+CD25– (%CD3); C] in the pancreas of wild-type (WT) and Cxcr2−/− mice.

Representative images showing immunohistochemistry of CD44 (A) and E-cadherin (B) in the tumor of wild-type (WT) and Cxcr2−/− mice. Tumors of both WT and Cxcr2−/− mice demonstrate no changes in CD44 and E-cadherin staining pattern. Scale bars = 100 μm (A and B). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Effect of host Cxcr2 deletion on the frequency of macrophages, T-regulatory (Treg) cells, cytotoxic T cells, and T helper cells in the spleen of tumor-bearing mice. Bar graph demonstrating changes on the percentages of macrophages [F480+ (%CD11b+); A], T-regulatory cells [CD3+CD4+CD25+ (%CD3); B], cytotoxic T cells [CD3+CD4–CD8+ (%CD3); C], and T helper cells [CD3+CD4+CD25− (%CD3); D] in the spleen of wild-type (WT) and Cxcr2−/− mice.

Host Cxcr2 deletion does not change the levels of murine (m)CXCL5 and mCXCL7 chemokines but CXCL2 in the serum of the pancreas of tumor-bearing mice. Bar graph showing no changes in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detection of mCXCL5 (A) and mCXCL7 (B), but increase in CXCL2 (C), in the serum of wild-type (WT) and Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing mice.

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erkan M., Reiser-Erkan C., Michalski C.W., Kleeff J. Tumor microenvironment and progression of pancreatic cancer. Exp Oncol. 2010;32:128–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans A., Costello E. The role of inflammatory cells in fostering pancreatic cancer cell growth and invasion. Front Physiol. 2012;3:270. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark C.E., Hingorani S.R., Mick R., Combs C., Tuveson D.A., Vonderheide R.H. Dynamics of the immune reaction to pancreatic cancer from inception to invasion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9518–9527. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wormann S.M., Diakopoulos K.N., Lesina M., Algul H. The immune network in pancreatic cancer development and progression. Oncogene. 2014;33:2956–2967. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desurmont T., Skrypek N., Duhamel A., Jonckheere N., Millet G., Leteurtre E., Gosset P., Duchene B., Ramdane N., Hebbar M., Van Seuningen I., Pruvot FoR, Huet G., Truant S.P. Overexpression of chemokine receptor CXCR2 and ligand CXCL7 in liver metastases from colon cancer is correlated to shorter disease-free and overall survival. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:262–269. doi: 10.1111/cas.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma B., Varney M.L., Saxena S., Wu L., Singh R.K. Induction of CXCR2 ligands, stem cell-like phenotype, and metastasis in chemotherapy-resistant breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2016;372:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi Z., Yang W.M., Chen L.P., Yang D.H., Zhou Q., Zhu J., Chen J.J., Huang R.C., Chen Z.S., Huang R.P. Enhanced chemosensitization in multidrug-resistant human breast cancer cells by inhibition of IL-6 and IL-8 production. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;135:737–747. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma B., Nannuru K.C., Saxena S., Varney M.L., Singh R.K. CXCR2: a novel mediator of mammary tumor bone metastasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1237. doi: 10.3390/ijms20051237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapman R.W., Phillips J.E., Hipkin R.W., Curran A.K., Lundell D., Fine J.S. CXCR2 antagonists for the treatment of pulmonary disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;121:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acharyya S., Oskarsson T., Vanharanta S., Malladi S., Kim J., Morris P.G., Manova-Todorova K., Leversha M., Hogg N., Seshan V-á, Norton L., Brogi E., Massagu J. A CXCL1 paracrine network links cancer chemoresistance and metastasis. Cell. 2012;150:165–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu L., Saxena S., Awaji M., Singh R.K. Tumor-associated neutrophils in cancer: going pro. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:564. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang S., Wu Y., Hou Y., Guan X., Castelvetere M.P., Oblak J.J., Banerjee S., Filtz T.M., Sarkar F.H., Chen X., Jena B.P., Li C. CXCR2 macromolecular complex in pancreatic cancer: a potential therapeutic target in tumor growth. Transl Oncol. 2013;6:216–225. doi: 10.1593/tlo.13133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frick V.O., Rubie C., Wagner M., Graeber S., Grimm H., Kopp B., Rau B.M., Schilling M.K. Enhanced ENA-78 and IL-8 expression in patients with malignant pancreatic diseases. Pancreatology. 2008;8:488–497. doi: 10.1159/000151776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li A., King J., Moro A., Sugi M.D., Dawson D.W., Kaplan J., Li G., Lu X., Strieter R.M., Burdick M., Go V.L., Reber H.A., Eibl G., Hines O.J. Overexpression of CXCL5 is associated with poor survival in patients with pancreatic cancer. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1340–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purohit A., Varney M., Rachagani S., Ouellette M.M., Batra S.K., Singh R.K. CXCR2 signaling regulates KRAS (G12D) -induced autocrine growth of pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;9:16. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuo Y., Raimondo M., Woodward T.A., Wallace M.B., Gill K.R., Tong Z., Burdick M.D., Yang Z., Strieter R.M., Hoffman R.M., Guha S. CXC-chemokine/CXCR2 biological axis promotes angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo in pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1027–1037. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li A., Dubey S., Varney M.L., Dave B.J., Singh R.K. IL-8 directly enhanced endothelial cell survival, proliferation, and matrix metalloproteinases production and regulated angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2003;170:3369–3376. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li A., Varney M.L., Valasek J., Godfrey M., Dave B.J., Singh R.K. Autocrine role of interleukin-8 in induction of endothelial cell proliferation, survival, migration and MMP-2 production and angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2005;8:63–71. doi: 10.1007/s10456-005-5208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston R.A., Mizgerd J.P., Shore S.A. CXCR2 is essential for maximal neutrophil recruitment and methacholine responsiveness after ozone exposure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L61–L67. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00101.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ijichi H., Chytil A., Gorska A.E., Aakre M.E., Bierie B., Tada M., Mohri D., Miyabayashi K., Asaoka Y., Maeda S., Ikenoue T., Tateishi K., Wright C.V.E., Koike K., Omata M., Moses H.L. Inhibiting Cxcr2 disrupts tumor-stromal interactions and improves survival in a mouse model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4106–4117. doi: 10.1172/JCI42754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuo Y., Ochi N., Sawai H., Yasuda A., Takahashi H., Funahashi H., Takeyama H., Tong Z., Guha S. CXCL8/IL-8 and CXCL12/SDF-1alpha co-operatively promote invasiveness and angiogenesis in pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:853–861. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuo Y., Campbell P.M., Brekken R.A., Sung B., Ouellette M.M., Fleming J.B., Aggarwal B.B., Der C.J., Guha S. K-Ras promotes angiogenesis mediated by immortalized human pancreatic epithelial cells through mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:799–808. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salcedo R., Resau J.H., Halverson D., Hudson E.A., Dambach M., Powell D., Wasserman K., Oppenheim J.J. Differential expression and responsiveness of chemokine receptors (CXCR1-3) by human microvascular endothelial cells and umbilical vein endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2000;14:2055–2064. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0963com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Addison C.L., Daniel T.O., Burdick M.D., Liu H., Ehlert J.E., Xue Y.Y., Buechi L., Walz A., Richmond A., Strieter R.M. The CXC chemokine receptor 2, CXCR2, is the putative receptor for ELR+ CXC chemokine-induced angiogenic activity. J Immunol. 2000;165:5269–5277. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kruger P., Saffarzadeh M., Weber A.N., Rieber N., Radsak M., von Bernuth H., Benarafa C., Roos D., Skokowa J., Hartl D. Neutrophils: between host defence, immune modulation, and tissue injury. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004651. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu L., Awaji M., Saxena S., Varney M.L., Sharma B., Singh R.K. IL-17-CXC chemokine receptor 2 axis facilitates breast cancer progression by up-regulating neutrophil recruitment. Am J Pathol. 2020;190:222–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu L., Saxena S., Singh R.K. In: Neutrophils in the tumor microenvironment. Tumor Microenvironment: Hematopoietic Cells – Part A. Birbrair A., editor. Springer International Publishing; New York, NY: 2020. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh S., Nannuru K.C., Sadanandam A., Varney M.L., Singh R.K. CXCR1 and CXCR2 enhances human melanoma tumourigenesis, growth and invasion. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1638–1646. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nannuru K.C., Sharma B., Varney M.L., Singh R.K. Role of chemokine receptor CXCR2 expression in mammary tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis. J Carcinog. 2011;10:40. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.92308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaul M.E., Fridlender Z.G. Neutrophils as active regulators of the immune system in the tumor microenvironment. J Leukoc Biol. 2017;102:343–349. doi: 10.1189/jlb.5MR1216-508R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torres M.P., Rachagani S., Souchek J.J., Mallya K., Johansson S.L., Batra S.K. Novel pancreatic cancer cell lines derived from genetically engineered mouse models of spontaneous pancreatic adenocarcinoma: applications in diagnosis and therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80580. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang D., Wang H., Brown J., Daikoku T., Ning W., Shi Q., Richmond A., Strieter R., Dey S.K., DuBois R.N. CXCL1 induced by prostaglandin E2 promotes angiogenesis in colorectal cancer. J Exp Med. 2006;203:941–951. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li A., Cheng X.J., Moro A., Singh R.K., Hines O.J., Eibl G. CXCR2-dependent endothelial progenitor cell mobilization in pancreatic cancer growth. Transl Oncol. 2011;4:20–28. doi: 10.1593/tlo.10184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hertzer K.M., Donald G.W., Hines O.J. CXCR2: a target for pancreatic cancer treatment? Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2013;17:667–680. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.772137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steele C W., Karim S A., Leach J D.G., Bailey P., Upstill-Goddard R., Rishi L., Foth M., Bryson S., McDaid K., Wilson Z., Eberlein C., Candido J B., Clarke M., Nixon C., Connelly J., Jamieson N., Carter C.R., Balkwill F., Chang D K., Evans T.R.J., Strathdee D., Biankin A V., Nibbs R J.B., Barry S T., Sansom O J., Morton J P. CXCR2 inhibition profoundly suppresses metastases and augments immunotherapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:832–845. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ansari A.M., Ahmed A.K., Matsangos A.E., Lay F., Born L.J., Marti G., Harmon J.W., Sun Z. Cellular GFP toxicity and immunogenicity: potential confounders in in vivo cell tracking experiments. Stem Cell Rev. 2016;12:553–559. doi: 10.1007/s12015-016-9670-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wente M.N., Keane M.P., Burdick M.D., Friess H., Buchler M.W., Ceyhan G.O., Reber H.A., Strieter R.M., Hines O.J. Blockade of the chemokine receptor CXCR2 inhibits pancreatic cancer cell-induced angiogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2006;241:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feig C., Gopinathan A., Neesse A., Chan D.S., Cook N., Tuveson D.A. The pancreas cancer microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4266–4276. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katoh H., Wang D., Daikoku T., Sun H., Dey S-á, DuBois R-á. CXCR2-expressing myeloid-derived suppressor cells are essential to promote colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:631–644. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Highfill S.L., Cui Y., Giles A.J., Smith J.P., Zhang H., Morse E., Kaplan R.N., Mackall C.L. Disruption of CXCR2-mediated MDSC tumor trafficking enhances anti-PD1 efficacy. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:237ra67. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bailey C., Negus R., Morris A., Ziprin P., Goldin R., Allavena P., Peck D., Darzi A. Chemokine expression is associated with the accumulation of tumour associated macrophages (TAMs) and progression in human colorectal cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2007;24:121–130. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han X., Shi H., Sun Y., Shang C., Luan T., Wang D., Ba X., Zeng X. CXCR2 expression on granulocyte and macrophage progenitors under tumor conditions contributes to mo-MDSC generation via SAP18/ERK/STAT3. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:598. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1837-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cortez-Retamozo V., Etzrodt M., Newton A., Rauch P.J., Chudnovskiy A., Berger C., Ryan R.J.H., Iwamoto Y., Marinelli B., Gorbatov R., Forghani R., Novobrantseva T.I., Koteliansky V., Figueiredo J.L., Chen J.W., Anderson D.G., Nahrendorf M., Swirski F.K., Weissleder R., Pittet M.J. Origins of tumor-associated macrophages and neutrophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:2491–2496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113744109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Keane J.C., Wolf B.C., Neiman R.S. The pathogenesis of splenic extramedullary hematopoiesis in metastatic carcinoma. Cancer. 1989;63:1539–1543. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890415)63:8<1539::aid-cncr2820630814>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gerard C., Rollins B.J. Chemokines and disease. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:108–115. doi: 10.1038/84209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cacalano G., Lee J., Kikly K., Ryan A.M., Pitts-Meek S., Hultgren B., Wood W.I., Moore M.W. Neutrophil and B cell expansion in mice that lack the murine IL-8 receptor homolog. Science. 1994;265:682–684. doi: 10.1126/science.8036519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shuster D.E., Kehrli M.E., Jr., Ackermann M.R. Neutrophilia in mice that lack the murine IL-8 receptor homolog. Science. 1995;269:1590–1591. doi: 10.1126/science.7667641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kusmartsev S., Gabrilovich D.I. Role of immature myeloid cells in mechanisms of immune evasion in cancer. Cancer Immunol Immun. 2006;55:237–245. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0048-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mei J., Liu Y., Dai N., Hoffmann C., Hudock K.M., Zhang P., Guttentag S.H., Kolls J.K., Oliver P.M., Bushman F.D., Worthen G.S. Cxcr2 and Cxcl5 regulate the IL-17/G-CSF axis and neutrophil homeostasis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:974–986. doi: 10.1172/JCI60588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang D., Sun H., Wei J., Cen B., DuBois R.N. CXCL1 is critical for premetastatic niche formation and metastasis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:3655–3665. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Acharyya S., Oskarsson T., Vanharanta S., Malladi S., Kim J., Morris P.G., Manova-Todorova K., Leversha M., Hogg N., Seshan V.E., Norton L., Brogi E., Massague J. A CXCL1 paracrine network links cancer chemoresistance and metastasis. Cell. 2012;150:165–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Granot Z., Henke E., Comen E.A., King T.A., Norton L., Benezra R. Tumor entrained neutrophils inhibit seeding in the premetastatic lung. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:300–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee W., Ko S.Y., Mohamed M.S., Kenny H.A., Lengyel E., Naora H. Neutrophils facilitate ovarian cancer premetastatic niche formation in the omentum. J Exp Med. 2019;216:176–194. doi: 10.1084/jem.20181170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ng L.G. Neutrophil: a mobile fertilizer. J Exp Med. 2019;216:4–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.20182059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Teijeira A., Garasa S., Gato M., Alfaro C., Migueliz I., Cirella A., de Andrea C., Ochoa M.C., Otano I., Etxeberria I., Andueza M.P., Nieto C.P., Resano L., Azpilikueta A., Allegretti M., de Pizzol M., Ponz-Sarvise M., Rouzaut A., Sanmamed M.F., Schalper K., Carleton M., Mellado M., Rodriguez-Ruiz M.E., Berraondo P., Perez-Gracia J.L., Melero I. CXCR1 and CXCR2 chemokine receptor agonists produced by tumors induce neutrophil extracellular traps that interfere with immune cytotoxicity. Immunity. 2020;52:856–871.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Albrengues J., Shields M.A., Ng D., Park C.G., Ambrico A., Poindexter M.E., Upadhyay P., Uyeminami D.L., Pommier A., Kuttner V., Bruzas E., Maiorino L., Bautista C., Carmona E.M., Gimotty P.A., Fearon D.T., Chang K., Lyons S.K., Pinkerton K.E., Trotman L.C., Goldberg M.S., Yeh J.T., Egeblad M. Neutrophil extracellular traps produced during inflammation awaken dormant cancer cells in mice. Science. 2018;361:eaao4227. doi: 10.1126/science.aao4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sano M., Ijichi H., Takahashi R., Miyabayashi K., Fujiwara H., Yamada T., Kato H., Nakatsuka T., Tanaka Y., Tateishi K., Morishita Y., Moses H.L., Isayama H., Koike K. Blocking CXCLs–CXCR2 axis in tumor–stromal interactions contributes to survival in a mouse model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma through reduced cell invasion/migration and a shift of immune-inflammatory microenvironment. Oncogenesis. 2019;8:8. doi: 10.1038/s41389-018-0117-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li C., Jiang P., Wei S., Xu X., Wang J. Regulatory T cells in tumor microenvironment: new mechanisms, potential therapeutic strategies and future prospects. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:116. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01234-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sakaguchi S., Mikami N., Wing J.B., Tanaka A., Ichiyama K., Ohkura N. Regulatory T cells and human disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2020;38:541–566. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042718-041717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toker A., Ohashi P.S. Expression of costimulatory and inhibitory receptors in FoxP3(+) regulatory T cells within the tumor microenvironment: implications for combination immunotherapy approaches. Adv Cancer Res. 2019;144:193–261. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Campbell C., Rudensky A. Roles of regulatory T cells in tissue pathophysiology and metabolism. Cell Metab. 2020;31:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cuadrado E., van den Biggelaar M., de Kivit S., Chen Y.Y., Slot M., Doubal I., Meijer A., van Lier R.A.W., Borst J., Amsen D. Proteomic analyses of human regulatory T cells reveal adaptations in signaling pathways that protect cellular identity. Immunity. 2018;48:1046–1059.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chao T., Furth E.E., Vonderheide R.H. CXCR2-dependent accumulation of tumor-associated neutrophils regulates T-cell immunity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:968–982. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kusmartsev S.A., Li Y., Chen S.H. Gr-1+ myeloid cells derived from tumor-bearing mice inhibit primary T cell activation induced through CD3/CD28 costimulation. J Immunol. 2000;165:779–785. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stoll S., Delon J., Brotz T.M., Germain R.N. Dynamic imaging of T cell-dendritic cell interactions in lymph nodes. Science. 2002;296:1873–1876. doi: 10.1126/science.1071065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miller M.J., Safrina O., Parker I., Cahalan M.D. Imaging the single cell dynamics of CD4+ T cell activation by dendritic cells in lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 2004;200:847–856. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Corzo C.A., Condamine T., Lu L., Cotter M.J., Youn J.I., Cheng P., Cho H.I., Celis E., Quiceno D.G., Padhya T., McCaffrey T.V., McCaffrey J.C., Gabrilovich D.I. HIF-1alpha regulates function and differentiation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2439–2453. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gabrilovich D.I., Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fujimura T., Mahnke K., Enk A.H. Myeloid derived suppressor cells and their role in tolerance induction in cancer. J Dermatol Sci. 2010;59:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goedegebuure P., Mitchem J.B., Porembka M.R., Tan M.C., Belt B.A., Wang-Gillam A., Gillanders W.E., Hawkins W.G., Linehan D.C. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: general characteristics and relevance to clinical management of pancreatic cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:734–751. doi: 10.2174/156800911796191024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The deletion of host Cxcr2 inhibits s.c. tumor growth angiogenesis and in situ cell proliferation. Bar graph demonstrating inhibition in the tumor growth (A), cell proliferation (B), and angiogenesis (C) in the s.c. tumors of wild-type (WT) and Cxcr2−/− mice. Statistical significance determined by U-test. ∗P < 0.05.

Effect of host Cxcr2 deletion on the frequency of macrophages, cytotoxic T cells, and T helper cells in the pancreas of tumor-bearing mice. Bar graph demonstrating changes on the percentages of macrophages [F480+ (%CD11b+); A], cytotoxic T cells [CD3+CD4–CD8+ (%CD3); B], and T helper cells [CD3+CD4+CD25– (%CD3); C] in the pancreas of wild-type (WT) and Cxcr2−/− mice.

Representative images showing immunohistochemistry of CD44 (A) and E-cadherin (B) in the tumor of wild-type (WT) and Cxcr2−/− mice. Tumors of both WT and Cxcr2−/− mice demonstrate no changes in CD44 and E-cadherin staining pattern. Scale bars = 100 μm (A and B). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Effect of host Cxcr2 deletion on the frequency of macrophages, T-regulatory (Treg) cells, cytotoxic T cells, and T helper cells in the spleen of tumor-bearing mice. Bar graph demonstrating changes on the percentages of macrophages [F480+ (%CD11b+); A], T-regulatory cells [CD3+CD4+CD25+ (%CD3); B], cytotoxic T cells [CD3+CD4–CD8+ (%CD3); C], and T helper cells [CD3+CD4+CD25− (%CD3); D] in the spleen of wild-type (WT) and Cxcr2−/− mice.

Host Cxcr2 deletion does not change the levels of murine (m)CXCL5 and mCXCL7 chemokines but CXCL2 in the serum of the pancreas of tumor-bearing mice. Bar graph showing no changes in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detection of mCXCL5 (A) and mCXCL7 (B), but increase in CXCL2 (C), in the serum of wild-type (WT) and Cxcr2−/− tumor-bearing mice.