This randomized clinical trial evaluates the efficacy and safety of timolol maleate solution, 0.5%, for the early treatment of infantile hemangioma in infants younger than 60 days.

Key Points

Question

Does the use of topical timolol in the first 2 months of life prevent further infantile hemangioma (IH) growth?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 69 patients younger than 60 days, there were no significant differences between use of timolol and placebo for complete or nearly complete IH resolution at 24 weeks. A significant improvement in lesion color was observed at week 4 in the timolol group, and topical timolol was well tolerated.

Meaning

Topical timolol appears well tolerated in the treatment of early proliferative IH but provides limited benefit in the resolution of lesions when given during the early proliferative stage.

Abstract

Importance

Treatment of infantile hemangioma (IH) with topical timolol in the first 2 months of life (early proliferative phase) may prevent further growth and the need for treatment with oral propranolol. To our knowledge, no studies have determined whether beginning early treatment with timolol for IH is better than in other proliferative stages.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of timolol maleate solution, 0.5%, for the early treatment of IH in infants younger than 60 days.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2a pilot clinical trial included patients aged 10 to 60 days with focal or segmental hemangiomas (superficial, deep, mixed, or minimal/arrested growth). Patients were randomly assigned to treatment with topical timolol maleate solution, 0.5%, or placebo twice daily for 24 weeks. Changes in lesion size (volume, thickness) and color were evaluated from photographs taken at 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 36 weeks. Vital signs and adverse effects were recorded at each visit. The study was carried out from November 2015 to January 2017, and data analyses were completed in September 2019.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome of complete or nearly complete IH resolution and the secondary outcomes of changes in lesion thickness, volume, and color were evaluated by a blinded investigator.

Results

Of the 69 patients recruited, the mean (SD) age was 48.4 (10.6) days; 55 (80%) were female; and 51 (74%), 11 (16%), 6 (9%), and 1 (1%) had superficial, mixed, abortive, or deep IHs, respectively. The IHs were localized, segmental, or indeterminate in 60 (87%), 7 (10%), and 2 (3%) patients, respectively. The IHs were located on the head and/or neck (n = 23 [33%]) or other body sites (n = 46 [67%]). The study was completed by 26 of 33 (79%) patients receiving timolol and 31 of 36 (86%) receiving placebo. There were no significant differences between timolol and placebo for complete or nearly complete IH resolution at 24 weeks (n = 11 [42%] vs n = 11 [36%]; P = .37). The odds ratio of complete or almost complete response vs no response at week 24 was 1.33 (95% CI, 0.45-3.89). There were no between-group differences in IH size (volume, thickness). An improvement in color was observed at week 4 in the timolol group, and timolol was well tolerated with no systemic adverse effects.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this randomized clinical trial, results demonstrated that topical timolol is well tolerated for the treatment of early proliferative IH but provides limited benefit in lesion resolution when given during the early proliferative stage.

Trial Registration

EudraCT Identifier: 2013-005199-17

Introduction

Infantile hemangiomas (IHs) are the most common benign tumors of infancy.1 They exhibit a rapid growth before 8 weeks of age, and most growth is complete by 5 months of age.2,3 Most IHs regress spontaneously without treatment, but complications needing treatment arise in approximately 10% to 15% of cases.4,5,6

In recent years, timolol maleate, a nonselective β-adrenergic drug, has been used as a topical agent to treat superficial IHs. A recent meta-analysis7 concluded that topical timolol is an effective and safe agent for treatment of superficial IHs, although the quality of evidence was assessed as low to moderate, with only 1 small randomized clinical trial (RCT)8 included in the analysis. Consequently, there is very little guidance on the use of topical timolol for IH in clinical practice.7

We hypothesized that the use of topical timolol in the early proliferative phase would be even more effective for preventing hemangioma growth and the need for oral propranolol treatment. This pilot RCT aimed to analyze the efficacy and safety of timolol maleate solution, 0.5%, for treating IM during the first 60 days of life.

Methods

This was a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2a clinical trial approved by all participating centers’ institutional review boards (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau in Barcelona, Spain, and Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío in Seville, Spain) and executed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines were used.

Patients aged 10 to 60 days with focal or segmental IHs (superficial, deep, mixed, or minimal/arrested growth) were recruited. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in the trial protocol in Supplement 1.

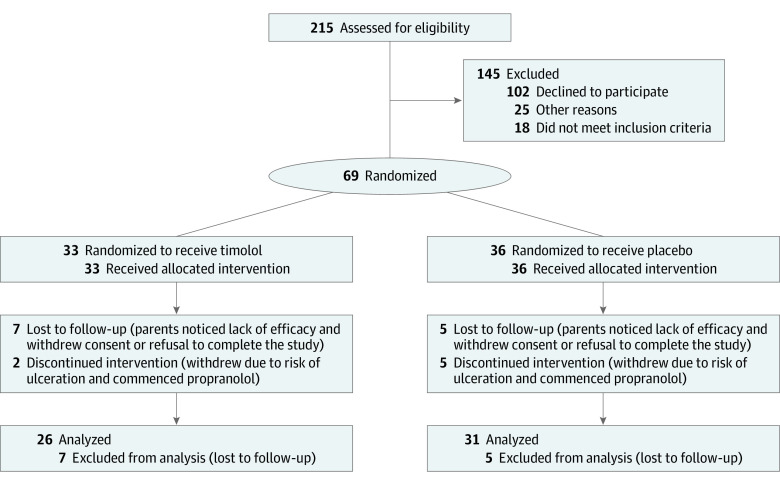

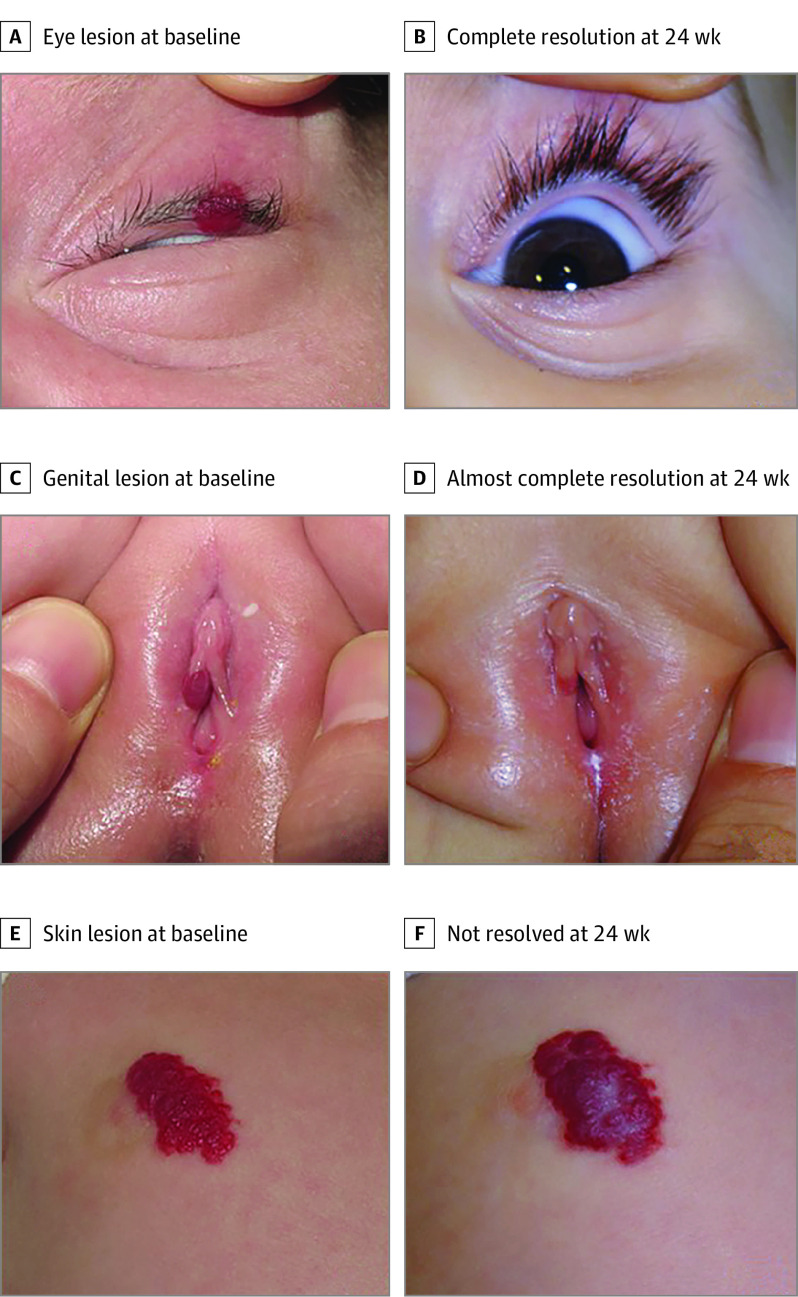

Participants were randomized through a computer-generated process to receive either 2 drops of timolol maleate solution, 0.5%, administered topically every 12 hours for 24 weeks or 2 drops of a saline-based placebo (Figure 1). Clinical photographs of the IHs taken at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 36 weeks were used to assess the degree of resolution of the IHs, which were assessed qualitatively as complete, almost complete, or not resolved (Figure 2) by the study investigator (F.Z.M.) and a blinded evaluator (J.B.). Lesion volume was assessed using 2 perpendicular hemicircumferential measurements of the IHs.9 Coloration was assessed using a semiquantitative scale (1, barely noticeable; 2, red with central clearing; 3, dull red; 4, bright red). Systemic effects were assessed by measuring systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate at baseline, 1 hour after the initial dose of timolol or placebo, and at weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24. Adverse effects were reported at every visit.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

Figure 2. Degree of Infantile Hemangioma Resolution.

Examples of degree of resolution in 3 hemangiomas treated with timolol and assessed qualitatively as complete (A), almost complete (B), or not resolved (C) after 24 weeks of treatment. Almost complete resolution was defined as a minimum degree of telangiectasia, erythema, cutaneous thickening, soft tissue swelling, and/or distortion of anatomical references.

The primary end point was the rate of complete or almost complete resolution of the IH after 24 weeks of treatment with timolol or placebo. Secondary outcomes were change in thickness, volume, and coloration of the IH at 24 weeks of treatment; persistence of efficacy, assessed at 36 weeks; and the safety and tolerability of timolol.

To estimate the sample size, we hypothesized a 10% response rate for placebo and 40% response rate for timolol. Based on these assumptions, with a 2-sided significance of P = .05 and power of 0.8, a total sample size of 70 patients was required with fewer than 10% withdrawals.

All analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 25.0 (IBM Corporation). Fisher exact test was used to evaluate response to treatment. Changes in lesion volume, thickness, and color were analyzed through Wilcoxon test for paired data. A threshold of P = .05 was used for statistical significance. For more detailed descriptions of the statistics, see eMethods in Supplement 2.

Results

Of the 69 patients included in the analysis, the mean (SD) age was 48.4 (10.6) days, 55 (80%) were female, 33 (48%) were randomized to topical treatment with timolol and 33 (48%) to placebo. A total of 50 patients completed 24 weeks of treatment, 24 (48%) with timolol and 26 (52%) with placebo. Baseline demographics and characteristics of the 69 patients evaluable by patient-reported outcome are summarized in eTable 1 in Supplement 2.

Efficacy Outcomes

At 24 weeks, 11 (42%) patients treated with timolol had complete or nearly complete resolution of IH compared with 11 (36%) in the placebo group, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = .37). In the per-protocol analysis (n = 57), the odds ratio of complete or almost complete response vs no response was 1.33 (95% CI, 0.45-3.89) at 24 weeks; in the intention-to-treat analysis (n = 69), there were no significant differences in response and the odds ratio was 1.36 (95% CI, 0.41-3.13).

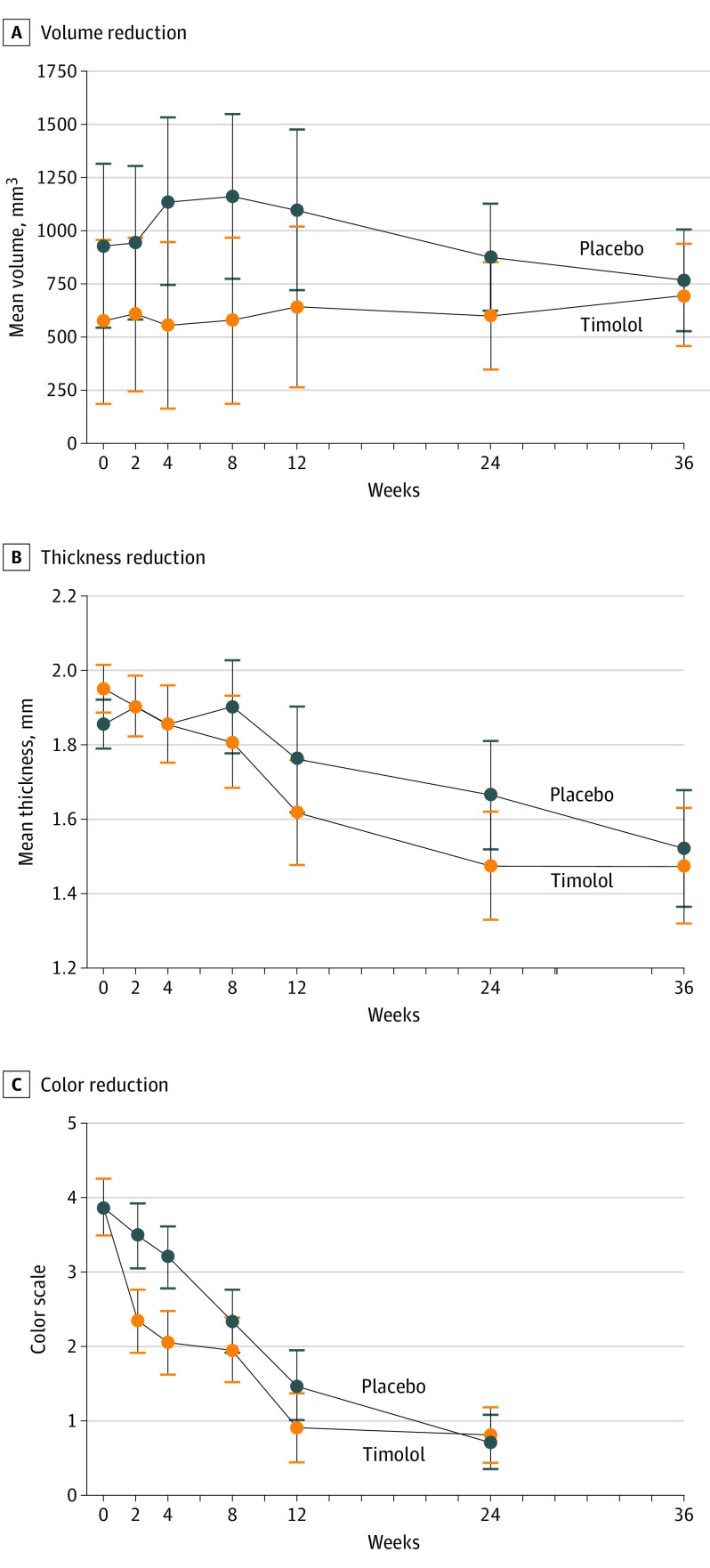

We observed a decrease of IH volume in the timolol group related to the time of evolution compared with the placebo group, although statistical significance was not achieved (week 2, P < .51; week 4, P < .30; week 8, P < .30; week 12, P < .40; week 24, P < .04; and week 36, P < .84; supporting data are reported in Figure 3A and eFigure in Supplement 2). Likewise, no statistically significant differences were found in the decrease of IH mean thickness between both groups (week 2, P < .99; week 4, P < .74; week 8, P < .59; week 12, P < .48; week 24, P < .36; and week 36, P < .83; supporting data are reported in Figure 3B); however, in the timolol group, the decrease in thickness occurred earlier than in the placebo group. In both groups, there was an improvement in color related to the time of evolution, which was more pronounced in the timolol group but was only significant at week 4 (week 2, P < .33; week 4, P < .01; week 8, P < .09; week 12, P < .61; and week 24, P < .12; supporting data are reported in Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Volume, Thickness, and Color of Infantile Hemangioma During Evaluation.

All error bars indicate an SD of 1.

Safety Outcomes

Comparison of baseline systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate with 1-hour posttreatment levels showed no significant differences between both groups (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Posttreatment heart rate was reduced in both treatment groups but failed to achieve statistical significance. Three patients in the timolol group had hypotension 1 hour posttreatment, and 1 patient had bradycardia. All patients were asymptomatic during the episodes.

Adverse events were noted in 16 patients across both groups. Local xerosis from medication, ulceration, and infection of the IH were the most common adverse events, although no events resulted in drug discontinuation.

Discussion

This RCT assessed the efficacy and safety of topical timolol for treatment of IH in the early proliferative phase. Difference in resolution rate with use of timolol was not significant compared with placebo. There were also no significant differences in IH volume and thickness, although volume measurements were difficult and imprecise in patients with mainly superficial IMs. Treatment with timolol produced a statistically significant improvement in lesion color only at week 4. A retrospective, multicenter cohort study of topical timolol treatment in patients with IHs aged 1 to 3 months (n = 454) showed similar results where color improvement (69.6%) was much greater than improvement in size, extent, and volume (38.8%).10 The rapid improvement observed in color may reassure parents and even justify treatment for IHs in visible areas.

The use of timolol in the first weeks of life did not always achieve hemangioma stabilization; therefore, patients treated with timolol should be monitored closely. Owing to the risk of ulceration, 7 patients were switched during the current study to treatment with oral propranolol, the drug of choice for systemic treatment of IH.4,11

Although we found no safety concerns with use of timolol in the present study, detectable levels of timolol have been reported in the urine and blood following topical treatment of IHs.12,13,14 Special attention to avoid systemic absorption is advisable when using timolol in infants with low birth weight, or an IH of more than 3-mm thickness, on the diaper area, or near mucous membranes.15

Limitations

The main limitations of this study were that the final sample size was less than originally calculated and that there was a higher rate of dropouts than expected. A larger number of patients might have proven significance.

Conclusions

In this RCT, topical timolol solution, 0.5%, used twice daily for 24 weeks was not effective for the treatment of early proliferative IH. There was only improvement in lesion color at week 4, but it was not significantly different than with use of placebo. This early improvement may be highly desired for some families for whom visible IHs may cause social stigma. There were no noteworthy systemic adverse effects. Larger multicenter RCTs may be needed to demonstrate the efficacy of this treatment.

Trial Protocol

eMethods.

eTable 1. Baseline characteristics of patients with infantile hemangiomas

eTable 2. Blood pressure and heart rate measurements at baseline and 1-hour post initial treatment

eFigure. Lesion thickness, by category, in IH patients treated with timolol or placebo for 24 weeks

References

- 1.Munden A, Butschek R, Tom WL, et al. Prospective study of infantile haemangiomas: incidence, clinical characteristics and association with placental anomalies. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(4):907-913. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tollefson MM, Frieden IJ. Early growth of infantile hemangiomas: what parents’ photographs tell us. Pediatrics. 2012;130(2):e314-e320. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang LC, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, et al. ; Hemangioma Investigator Group . Growth characteristics of infantile hemangiomas: implications for management. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):360-367. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390(10089):85-94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00645-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, Nopper AJ; Section on Dermatology, Section on Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, and Section on Plastic Surgery . Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):e1060-e1104. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baselga E, Roe E, Coulie J, et al. Risk factors for degree and type of sequelae after involution of untreated hemangiomas of infancy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(11):1239-1243. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.2905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan M, Boyce A, Prieto-Merino D, Svensson Å, Wedgeworth E, Flohr C. The role of topical timolol in the treatment of infantile hemangiomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(10):1167-1171. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan H, McKay C, Adams S, Wargon O. RCT of timolol maleate gel for superficial infantile hemangiomas in 5- to 24-week-olds. Pediatrics. 2013;131(6):e1739-e1747. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsang MW, Garzon MC, Frieden IJ. How to measure a growing hemangioma and assess response to therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23(2):187-190. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00216.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Püttgen K, Lucky A, Adams D, et al. ; Hemangioma Investigator Group . Topical timolol maleate treatment of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20160355. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Léauté-Labrèze C, Hoeger P, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of oral propranolol in infantile hemangioma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):735-746. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weibel L, Barysch MJ, Scheer HS, et al. Topical timolol for infantile hemangiomas: evidence for efficacy and degree of systemic absorption. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(2):184-190. doi: 10.1111/pde.12767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borok J, Gangar P, Admani S, Proudfoot J, Friedlander SF. Safety and efficacy of topical timolol treatment of infantile haemangioma: a prospective trial. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(1):e51-e52. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drolet BA, Boakye-Agyeman F, Harper B, et al. ; Pediatric Trials Network Steering Committee . Systemic timolol exposure following topical application to infantile hemangiomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(3):733-736. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frommelt P, Juern A, Siegel D, et al. Adverse events in young and preterm infants receiving topical timolol for infantile hemangioma. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(4):405-414. doi: 10.1111/pde.12869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eMethods.

eTable 1. Baseline characteristics of patients with infantile hemangiomas

eTable 2. Blood pressure and heart rate measurements at baseline and 1-hour post initial treatment

eFigure. Lesion thickness, by category, in IH patients treated with timolol or placebo for 24 weeks