Clinical History

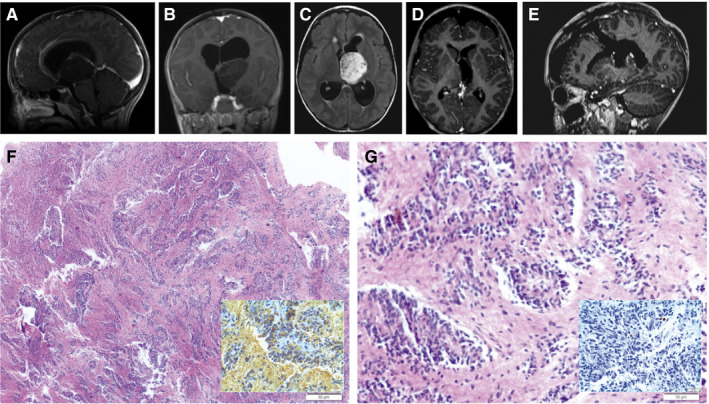

An eight‐year‐old female patient, who was previously healthy, presented with episodes of a headache followed by recurrent bilateral eyelid movements described as a "heartbeat" that lasts few seconds following by spontaneous remission without loss of consciousness. These symptoms were experienced periodically for about 30 days. On physical examination, the patient showed no motor, sensory, or cognitive deficits. A CT brain scan revealed a left thalamic mass lesion without contrast enhancement. MRI revealed an extensive left thalamic tumor that was hypointense/isointense on T1‐weighted MRI, hyperintense on T2‐weighted MRI. The sagittal (Figure 1A) and coronal (Figure 1B) views of a T1‐weighted MRI after gadolinium injection evidenced no‐enhancement of a large anterodorsal left thalamic tumor compressing the third ventricle. While the axial view of a FLAIR MRI showed the hyperintensity of a large tumor in the left thalamus (Figure 1C). A transcranial EEG showed no abnormalities.

Figure 1.

The patient underwent microsurgery to resect the tumor using a left frontal transcortical approach that was performed with the aid of surgical microscope and intraoperative electrophysiological monitoring of somatosensory evoked potentials. The patient achieved gross total resection of the tumor (Figure 1D, E) and experienced no postoperative deficits or any episodes of blepharospasm even from the first postoperative day. The patient remains on outpatient follow‐up after 15 months without adjuvant treatment, and the most recent brain MRI revealed no recurrence of the injury.

Gross and Microscopic Pathology

Examination of the resected tissue showed bipolar cells that were elongated and homomorphous with moderate cellularity (Figure 1F). The tumors cells have spindle‐cell morphology, displayed in angiocentric patterns and perivascular rosettes (Figure 1G). No mitotic activity is appreciated. No vascular proliferation or necrosis present. The tumor is immunoreactive for GFAP (Figure 1H). A stain to neurofilament demonstrates the infiltrative nature of the lesion. The tumor demonstrates dot‐like perinuclear immunoreactivity for EMA. The frequency of Ki67/Mib‐1 immunolabeling in the tumor cells is very low (Figure 1I). MYB rearrangement was detected by iFISH in the tumor samples. What is your diagnosis?

Diagnosis

Angiocentric Glioma.

Discussion

Angiocentric gliomas are WHO grade I tumors, classified within a subgroup of gliomas that includes astroblastoma and chordoid gliomas of the third ventricle 2. They are rare tumors with few reported cases or case series. Interestingly, almost all such tumors present with simple partial or complex partial seizures, or in some cases with status epilepticus. Furthermore, they are also characterized by drug‐resistant seizure 3.

Microscopy reveals infiltrative characteristics in angiocentric gliomas. Bipolar cells are arranged in an elongated, monomorphous and angiocentric pattern along cortical blood vessels. There are also pseudorosettes of ependymoma‐like, subpial aggregates and miniature schwannoma‐like nodules. There is usually no mitosis and limited vascular proliferation. Immunohistochemistry shows positive results for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and variable results for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), S‐100 protein and vimentin (VIM) 2, 3.

The main differential diagnosis to be considered alongside angiocentric glioma is ependymoma. Given that the microscopic appearances of both possess similar features, such as perivascular rosettes, histopathological differentiation between these two tumors can be a challenge. However, determining the diagnosis is of considerable practical importance due to differences in respective prognosis. Supratentorial ependymoma is considered a WHO grade II tumor. However, while characterized as a low‐grade tumor, supratentorial ependymoma can relapse and disseminate, frequently requiring adjuvant therapy and surgical reinterventions. In contrast, angiocentric glioma, a WHO grade I tumor, is rarely associated with relapse or malignant transformation following complete surgical resection. Other differential diagnoses include astroblastoma and astrocytoma 2, 3.

Recently, Zhang et al. 4 found MYB rearrangements in groups of patients with angiocentric gliomas. Genomic analysis of angiocentric gliomas revealed a tripartite mechanism involving MYB‐QKI rearrangements, which suggests a different tumor profile that separates angiocentric gliomas from others gliomas 1.

This case endorses that angiocentric glioma may be present, albeit more rarely, in brain regions such as the thalamus and not necessarily be associated with seizures. Additionally, the MYB rearrangement should be seen as a potential genetic alteration to characterize the angiocentric gliomas in the new area of pathologic definitions aided by genetic profiles.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Brent Alan Orr, MD, PhD. and Dr. David Ellison, MD, PhD. for performing the pathology review at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

References

- 1. Bandopadhayay P, Ramkissoon LA, Jain P, Bergthold G, Wala J, Zeid R, et al. (2016) MYB‐QKI rearrangements in angiocentric glioma drive tumorigenicity through a tripartite mechanism. Nat Genet 48:273–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella‐Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. (2016) The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 131:803–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang M, Tihan T, Rojiani AM, Bodhireddy SR, Prayson RA, Iacuone JJ, et al. (2005) Monomorphous angiocentric glioma: a distinctive epileptogenic neoplasm with features of infiltrating astrocytoma and ependymoma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 64(10):875–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang J, Wu G, Miller CP, Tatevossian RG, Dalton JD, Tang B, et al. (2013) Whole‐genome sequencing identifies genetic alterations in pediatric low‐grade gliomas. Nat Genet 45:602–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]