Abstract

The cellular prion protein (PrPC) is best known for its misfolded disease‐causing conformer, PrPSc. Because the availability of PrPC is often limiting for prion propagation, understanding its regulation may point to possible therapeutic targets. We sought to determine to what extent the human microRNAome is involved in modulating PrPC levels through direct or indirect pathways. We probed PrPC protein levels in cells subjected to a genome‐wide library encompassing 2019 miRNA mimics using a robust time‐resolved fluorescence‐resonance screening assay. Screening was performed in three human neuroectodermal cell lines: U‐251 MG, CHP‐212 and SH‐SY5Y. The three screens yielded 17 overlapping high‐confidence miRNA mimic hits, 13 of which were found to regulate PrPC biosynthesis directly via binding to the PRNP 3’UTR, thereby inducing transcript degradation. The four remaining hits (miR‐124‐3p, 192‐3p, 299‐5p and 376b‐3p) did not bind either the 3’UTR or CDS of PRNP, and were therefore deemed indirect regulators of PrPC. Our results show that multiple miRNAs regulate PrPC levels both directly and indirectly. These findings may have profound implications for prion disease pathogenesis and potentially also for their therapy. Furthermore, the possible role of PrPC as a mediator of Aβ toxicity suggests that its regulation by miRNAs may also impinge on Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: 3'UTR, microRNA, PRNP, PrP, screen

Introduction

Prion diseases are characterized by misfolding and aggregation of the cellular prion protein (PrPC) into its pathogenic conformer, PrPSc 42. Despite significant advances in exposing the physiological roles of PrPC and in elucidating mechanisms underlying PrPSc‐induced toxicity, the molecular machinery controlling spatiotemporal PrPC expression remains unexplored.

Over the past decade, microRNAs (miRNA) have emerged as important biomarkers and micro‐modulators of numerous biological processes ranging from development to disease 19. These roughly 22 nucleotide non‐coding RNAs predominantly regulate protein expression levels post‐transcriptionally by repressing and/or degrading an estimated 60% of all human protein‐coding transcripts 16. miRNAs function by associating with Argonaute (AGO) proteins to form a mature miRNA‐induced silencing complex (miRISC). While four human AGO proteins have been described, only AGO2 possesses endonucleolytic activity 31. miRNAs guide the miRISC to targets by typically binding their 2‐8 nucleotide “seed sites” to complementary mRNA 3′ untranslated regions (3′UTRs) 22. Comprehensive analysis of miRNA interaction sites in human brains using Argonaute cross‐linking immunoprecipitation (AGO‐CLIP) has revealed that 41% of these sites reside in 3′UTRs, while coding sequences (CDS), intronic regions and 5′ untranslated regions (5′UTR) make up the other 40%, 15% and 1%, respectively 9.

Several miRNAs, most notably miR‐124‐3p, miR‐146a‐5p and miR‐342‐3p, have been found to become consistently deregulated following prion infection in GT1‐7 neuronal cells 7, RML inoculation in mice 39, 40, scrapie infection in sheep 41, BSE infection in macaques 33 and sporadic Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease (sCJD) in humans 25. These miRNAs also display similar spatiotemporal expression patterns during prion disease pathogenesis 8, 27 and in sCJD subtypes 23, implying that mechanisms of deregulation may be conserved across species. Intriguingly, miR‐124‐3p, which is highly expressed in almost all brain regions 44, has also been found to be downregulated in the brains of patients suffering from Alzheimer’s 24 and Huntington’s disease 18. These data collectively qualify miRNAs as potential biomarkers and as possible regulators of the pathogenic process in transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSE). It has also been reported once (but never confirmed) that human PrPC binds AGO, and in doing so promotes the formation and stabilization of miRISC 17. However, it remains unknown to what extent, miRNAs might play a part in regulating PrPC expression levels. As suppression of PrPC by shRNA can abrogate PrPSc accumulation and prolongs survival of scrapie‐infected mice 37, identification of endogenous PrPC modulators may provide a therapeutic avenue for TSEs.

Several miRNA target prediction tools exist that calculate likeliness of miRNA binding to transcripts through assessing their thermodynamic stability and conserved seed region complementarity in 3’UTR 1 and CDS 38. Yet, these estimates remain tentative due to their high degree of false positives. AGO‐CLIP offers a more biologically accurate compendium of miRNA‐bound target sites. However, as these data are predominantly generated via AGO2 immunoprecipitation, the recovered hits correspond mostly to endonucleolytically cleaved transcripts 31, whereas the pleiotropic interplay between other AGO proteins is not reflected in CLIP data 43. Furthermore, miRNA‐AGO associations do not necessarily imply functional downstream effects. Accordingly, a comparison of miRNA transfection and AGO‐CLIP data revealed an overlap between miRNA targets detected by the two approaches, but found that CLIP was not strongly predictive of target expression changes 45. Cell‐based screenings can address the limitations of target detection techniques by assessing functionality of canonical, non‐canonical and indirect regulators.

The current study aims to examine the degree to which the human microRNAome affects PrPC expression, and determine whether PrPC‐regulating miRNAs function through direct or indirect pathways. Toward this goal, we developed a robust high‐throughput arrayed screen, employing a genome‐wide miRNA library. This exploratory approach was able to exhaustively analyze miRNA‐induced changes in PrPC, some of which were previously predicted by target interaction estimates, whereas others are entirely novel. These findings may acquire medical significance in view of the requirement for PrPC in development of prion diseases 12, 13 and its presumed, albeit controversial, role in mediating Aβ toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease 14, 21.

Methods

Cell lines

A homozygous frameshift mutation was generated in the PRNP locus of SH‐SY5Y (ATCC) using the CRISPR‐Cas9 system to delete the second adenine in the third codon of the PRNP CDS (chr20: 4,699,229), located in exon 2. This was achieved by designing a sgRNA that bound in close proximity to the PRNP start codon. This sgRNA was cloned into a MLM3636 expression vector and transfected into SH‐SY5Y wt cells alongside a Cas9‐2A‐EGFP plasmid. 48 h after transfection, single EGFP‐positive cells were sorted into a 96 well plate by single cell fluorescence‐activated cell sorting. Individual clones were expanded for four weeks and screened for PRNP ‐/‐. Clones were characterized by blunt‐end PCR insertion of PRNP fragments into TOPO vectors. Sanger sequencing (Figure S1) revealed that a double strand break and subsequent non‐homologous end joining had induced a frameshift and a premature stop codon, resulting in a functional PrPC knockout mutant. The full‐length 765bp linearized CDS region of mouse Prnp, under the control of a CMV promotor, was stably transfected and randomly integrated into these PrPC knockout cells. Following antibiotic selection, a single clone, designated SH‐SY5Y M4, was expanded on the basis of high PrPC expression levels.

SH‐SY5Y M4 and U‐251 MG (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) cells were cultured in OptiMEM supplemented with, 1% GlutaMAX (GM), 1% MEM Non‐Essential Amino Acids, 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (PS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 10% FBS (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA, USA). CHP‐212 were cultured in a 1:1 ratio of EMEM (ATCC) to Ham’s F12 Nutrient Mixture (Thermo Fisher) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% PS. HEK‐293T (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM (Thermo Fisher) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% GM and 1% PS. All cell lines were grown in 150‐cm2 Corning cell culture flasks (Merck), counted using Trypan Blue (Thermo Fisher) in a TC20 Automated Cell Counter (Bio‐Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and seeded in absence of antibiotics during experimentation.

Screen workflow

2019 mirVana miRNA mimics or analogous inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were printed as triplicates in disparate locations across 24 white CulturPlate‐384 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) alongside Silencer Select human PRNP/mouse Prnp‐targeting (Ambion) positive control and AllStars Negative Control (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) siRNAs (44 per plate: 22 in outer‐ and 22 in central wells). Printing was performed using an Echo 555 acoustic dispenser (Labcyte Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) to obtain final concentrations of 20 nM for mimics and control siRNAs or 60nM for inhibitors per well. All following dispensing steps were carried out using peristaltic dispensing technology on the MultifloFX (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) with cassettes as indicated. Printed libraries were reverse transfected into cells by first dispensing 5 uL RNAiMAX (0.3% final) (Thermo Fisher) diluted in PS‐free media using a 1 uL cassette. Plates were centrifuged and seeded with 25 uL of 4000 SH‐SY5Y M4, 5000 CHP‐212 or 6000 U‐251 MG per well using a 5 uL cassette.

Following a 72‐h incubation period at 37°C, media was removed by turning the plate upside‐down and 10 uL of lysis buffer (0.5% Na deoxycholate, 0.5% Triton X, supplemented with cOmplete Mini Protease Inhibitors and 0.5% BSA (Merck)) was dispensed per well. 5 uL (2.5 nM final) POM2 or POM19 (made in‐house), coupled to Europium (Eu), as previously described 4, and diluted in 1X Lance Detection Buffer (Perkin Elmer) was dispensed for U‐251 MG and CHP‐212 or SH‐SY5Y M4 cells, respectively. Five microliter (5 nM final) POM1 conjugated to Allophycocyanin (APC) was successively added per well for all cell types screened. TR‐FRET readout was performed after a 12‐h 4°C incubation using an EnVison 2105 Multimode Plate Reader (PerkinElmer) with previously defined measurement parameters 4.

Quantitative PCR

Candidate mimic PRNP mRNA levels were assessed in a follow‐up U‐251 MG screen. Samples were identically processed up to the point of media removal, after which a 3:1 mixture of TRIzolLS (Thermo Fisher) to media was applied to wells and mRNA was extracted according the manufacturers’ protocol. QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) was used for cDNA synthesis and qPCR was performed using FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Rox) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Candidate mimics were run in biological triplicates and assessed for PRNP mRNA levels using GUSB, TBP and ACTB as housekeeping genes for sample normalization. HMGA2 mRNA normalized to ACTB was used as a post‐inhibitor screen quality control assessment to test library efficacy, using let‐7d‐5p inhibitor as a presumptive positive regulator of HMGA2. All qPCR samples were run in technical triplicates in white Hard‐Shell 96‐Well PCR Plates (Bio‐Rad) using the following primer pairs:

| PRNP (NM_000311.4): | For: GACCGAGGCAGAGCAGTCAT |

| Rev: AGTGTTCCATCCTCCAGGCTTC | |

| ACTB (NM_001101.3): | For: ACAGAGCCTCGCCTTTGCC |

| Rev: AGCGCGGCGATATCATCATCC | |

| GUSB (NM_000181.3): | For: GACACGCTAGAGCATGAGGG |

| Rev: GGGTGAGTGTGTTGTTGATGG | |

| TBP (NM_003194.4): | For: CCCGAAACGCCGAATATAATCC |

| Rev: AATCAGTGCCGTGGTTCGTG | |

| HMGA2 (NM_003483.4): | For: CACTTCAGCCCAGGGACAAC |

| Rev: CTCACCGGTTGGTTCTTGCT |

Cell viability

To assess miRNA‐induced alterations in cell viability, we used AllStars Hs Cell Death Control siRNA (Qiagen) as a positive control for candidate mimics in a follow‐up U‐251 MG screen. After 72 h incubation and media removal, 10 uL fresh media and 10 uL CellTiter‐Glo 2.0 (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) were added per well. Samples were incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature prior to performing an Ultra‐Sensitive luminescence readout on an EnVision reader at 0mm measurement height and 0.3 s integration time.

Quality control

Following TR‐FRET readout, FRET data from each 384‐well plate was inspected for the presence of systematic and random errors, for example, temperature‐induced plate gradients, dispensing patterns or problems while printing constructs into wells. We used the open‐source Python3 software tool HTS ( H igh T hroughput S creening) for data handling, screen quality control, statistical analysis and reporting of per‐well measurement data. Source code, installation manual, tutorials and data examples are available via elkeschaper.github.io/hts. HTS provides standard screening parameters in an automated and highly standardized manner. To comply with reproducible research standards, code, explanations, and analyses are all provided in one notebook report. In particular, the following readouts were computed with HTS: Net‐FRET calculations and heat map visualizations for controls and samples, TR‐FRET channel as well as cell viability heat maps, histograms and smoothened histograms for visualization of controls and samples, Z′‐factor and SSMD calculations, row/column effects.

Data analysis

Net FRET calculations and blank subtractions were performed as previously described 4 per plate for each mimic and inhibitor screen. Z′‐Factors (Z′) were calculated across all 24 plates per screen using central controls. Sample SSMDs were derived from biological triplicates and central negative control mean and standard deviation values across four plates, among which replicas were printed. Mimic screening hit calling criteria were set at ≥5, ≤−5 for U‐251 MG and ≥3, ≤−3 for both CHP‐212 and SH‐SY5Y M4. Inhibitor screen hit calling criteria were set at ≥1.5, ≤−1.5 for U‐251 MG and CHP‐212 due to overall low SSMD scores. Negative and positive controls from TR‐FRET, cell viability and qPCR assays were set at 100% and 0%, respectively. Samples were normalized to this range by feature scaling. An arbitrary 10% cutoff above or below the negative control was selected as the determinant for altered PrPC, cell viability or PRNP mRNA levels. An unpaired two‐tailed parametric t‐test was used for calculating significance between samples for the reporter assays.

Reporter construction

The wt PRNP 3’UTR and nine mutant forms thereof (Table S1) were cloned into pmirGLO Dual‐Luciferase miRNA Target Expression Vector (Promega) multiple cloning sites and downstream of firefly luciferase. Incorporation was achieved by simultaneously cloning various combinations of three gBlocks (IDT) into the cleaved multiple cloning site using Gibson Assembly Master Mix (NEB). Each mutant construct was designed to harbor two single nucleotide substitutions separated by a single unaltered nucleotide in the prospective single‐ or double binding site/s of the 3′UTR 30. Mimic hit site selection was based on TargetScan7.2 in silico predicted interactions. A reporter harboring the wt PNRP CDS was constructed by PCR‐amplifying the insert from primary human myoblast gDNA and cloning it in‐frame into the multiple cloning site of pmirGLO. Plasmid assembly was confirmed by XmnI (NEB) restriction digestion and insert sequencing using the following primers:

Seq‐3′UTR Rev1: GCAATTTACTTTTCAGCTGCC

Seq‐3′UTR For2: CTCTGGCTCCTTCAGCAGCTAG

Seq‐3′UTR For3: GGAGGCAACCTCCCATTTTAGATG

Seq‐CDS Rev1: CTGCCGAAATGTATGATGGG

Seq‐CDS For2: GTGGCTGGGGTCAAGGAG

Reporter assessment

Plasmid reporters (20 ng) and their corresponding mimics (20 nM final) were printed in white CulturPlate‐384 and reverse co‐transfected into HEK‐293T using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher) (0.3% final). Following a 37°C 48‐h incubation period, 30 uL of each Dual‐Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) reagent was sequentially added per well and incubated at RT for 20 minutes prior to Ultra‐Sensitive luminescence readout. Firefly luciferase signals were subsequently divided by Renilla luciferase signals for each well.

Western blotting

10–30 µg of BCA‐defined cell lysate was boiled at 95°C in NuPAGE LDS (Thermo Fisher) supplemented with 100 mM DTT (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Samples were loaded on NuPAGE 4%–12% Bis‐Tris gels and transferred to PVDF membranes via an iBlot 2 (Thermo Fisher). Membranes were blocked in 5% SureBlock (LubioScience, Zürich, Switzerland) and stained using POM1 or mouse anti‐actin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). HRP‐conjugated goat anti‐mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Cambridgeshire, UK) was used as a secondary antibody and Immobilon Crescendo (Merck) was used for imaging.

Results

High‐throughput screen reliably detects PrPC

To identify miRNAs regulating PrPC, we performed a genome‐wide human miRNA screen. We assessed PrPC levels from cell lysates in single wells using a time‐resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR‐FRET) readout as described 4. This allowed high‐throughput arrayed screening of the entire currently available human miRNA repertoire (miRBase v.21), consisting of 2′019 mimics and 2′019 corresponding inhibitors. Screening was performed using U‐251 MG glioblastoma, CHP‐212 neuroblastoma and SH‐SY5Y M4 neuroblastoma human cell lines (Figure 1A). Cell lines were selected based on high PrPC expression, as revealed by western blot (Figure S2A) and TR‐FRET (Figure S2B). SH‐SY5Y M4, a PRNP‐/‐ line overexpressing the mouse Prnp CDS (see Methods), was used for the selective interrogation of non‐3′UTR regulating miRNAs. Overlap of miRNA‐mediated PrPC regulation in multiple cell lines allowed us to identify high‐confidence hits that may be universally functional.

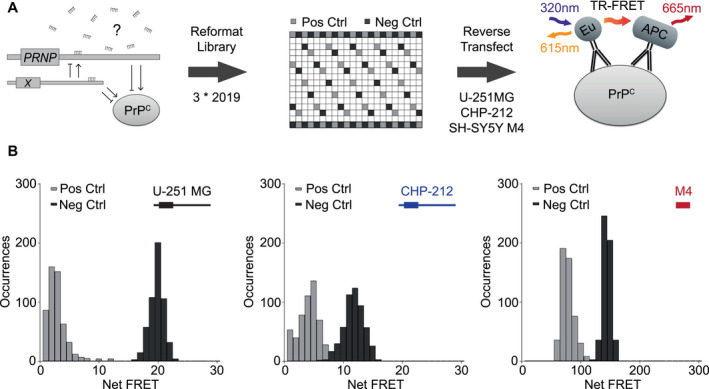

Figure 1.

Design of screening strategy and quality controls. A. Screening workflow comprises reformatting library, positive controls (light grey) and negative controls (dark grey) into 384‐well plates, reverse transfecting cells, incubating plates for 72 h, removing culture media, lysing content, dispensing fluorophore‐coupled antibodies and performing a TR‐FRET readout. B. Histograms displaying positive and negative control signal occurrences (22 each per plate across 24 plates) for U‐251 MG (Z′: 0.453), CHP‐212 (Z′: −0.403) and SH‐SY5Y M4 (Z′: 0.072) mimic screens with illustrations of each respectively expressed transcript.

As RNA interference (RNAi) screens are often hampered by poor reproducibility 5, we set out to develop a highly robust assay by optimizing sample and control distributions, library concentration, transfection reagent concentration, cell number, reaction volumes, incubation duration, lytic buffer composition and fluorophore‐coupled antibody concentration. In order to minimize effects of temperature‐induced gradients observed in cell‐based screens 26, we implemented a media removal step at 72 h (see Methods). We found that the incorporation of this step strongly reduced replicate variability (Figure S3). This observation indicated that pre‐media removal artifacts had primarily resulted from volumetric well‐to‐well disparities. No systemic intra‐ or inter‐plate gradients were observed for any screen. However, plate‐well series plots assessing row effects revealed small, albeit consistently disproportionate signals among outer, but not central control wells. Outer control wells were therefore excluded from all analyses.

PRNP/Prnp‐targeting siRNA positive controls and non‐targeting siRNA negative controls dispersed throughout each plate served as a screening quality benchmark. U‐251 MG mimic screening yielded the most pronounced separation of controls (Figure 1B), as revealed by a high Z‐factor (Z′: 0.453) across 24 plates. In contrast, CHP‐212 and SH‐SY5Y M4 screens only displayed poor (Z′: −0.403) and marginal (Z′: 0.072) qualities, respectively 46. Mimic replicates showed a robust correlation for U‐251 MG (R 2 mean: 0.65) and CHP‐212 (R 2 mean: 0.52), which was not the case for SH‐SY5Y M4 (R 2 mean: 0.22) (Figure S2C). miRNA inhibitors, while generating similar Z′ for U‐251 MG: 0.396 and CHP‐212: −0.346 (Figure S4B) did not affect PrPC expression levels (Figure S4C). Notably, low CHP‐212 Z‐factors, stemming from high control signal variabilities, may have been imparted by cell growth saturation.

Identification of 19 Overlapping Candidate Mimics

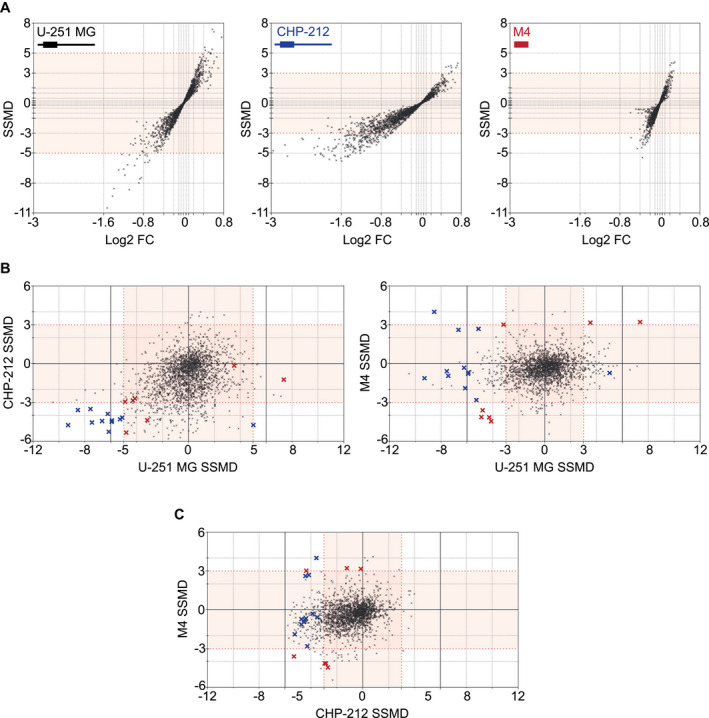

In order to highlight differences in sample reproducibility, denoted by strictly standardized mean difference (SSMD) 47, and biological effect sizes, denoted by log2 fold change, among cell lines, we visualized screening data using dual‐flashlight plots (Figure 2A and Figure S5A). Hit selection was performed by overlaying SSMDs from CHP‐212 or SH‐SY5Y M4 with U‐251 MG screens. We applied SSMDs set at extremely strong cutoffs (≥5, ≤−5) for U‐251 MG, and very strong cutoffs (≥3, ≤−3) 48 for CHP‐212 and SH‐SY5Y M4 cells. This yielded a total of 12 candidate mimics from CHP‐212 screen overlaps (blue crosses) and 7 candidate mimics from SH‐SY5Y M4 screen overlaps (red crosses) (Figure 2B). Mimic screen datasets displaying replicate Net FRET, SSMD, log2 fold change, P‐value, miRNA name and sequence are listed in Table S2. Intersection of CHP‐212 and SH‐SY5Y M4 SSMDs shows that this strategy would have called only 3 out of the 19 candidates (Figure 2C). However, as CHP‐212 produced a poor Z′ and SH‐SY5Y M4 harbored no PRNP 3′UTR, we opted to utilize more reliable hit‐calling strategy by contrasting screens only to U‐251 MG.

Figure 2.

miRNA mimic screening identified 19 candidate hits. A. Dual‐flashlight plots displaying SSMD vs. Log2 fold change (FC) with illustrations of each respectively expressed PRNP/Prnp transcript for U‐251 MG (black), CHP‐212 (blue) and SH‐SY5Y M4 (red) screens. Sample distribution angles illustrated in plots indicate cell‐line dependent variability in PrPC expression, with U‐251 MG exhibiting stronger sample replicability, exemplified by high SSMDs, and CHP‐212 exhibiting larger biological effect sizes, as illustrated by greater Log2 fold changes. B. SSMD overlaps between U‐251 MG (SSMD ≥5, ≤−5) and CHP‐212 (≥3, ≤−3) (left plot) identified 12 candidates (blue crosses). SSMD overlaps between U‐251 MG (≥3, ≤−3) and M4 (≥3, ≤−3) (right plot) identified 7 candidates (red crosses). A majority of candidates displayed consistent miRNA‐induced down‐ or upregulation in overlapped screens, whereas three hits exhibited divergent PrPC regulation. (Bottom right quadrant of left plot: 1 blue cross. Top left quadrant of right plot: 1 blue and 1 red cross). C. SSMD overlaps between CHP‐212 (≥3, ≤−3) and SH‐SY5Y M4 (≥3, ≤−3) shows comparative distribution of mimic candidates.

Inhibitor screening on the other hand, produced no overlaps between cell lines, even when setting low SSMD (≥1.5, ≤−1.5) cutoff criteria (Figure S5B). Moreover, no inhibitor generated SSMDs ≤−3 or ≥3 in any individual cell line. Inhibitor screen datasets are shown in Table S3. We assessed whether the absence of inhibitor effects was due to a lack of library functionality by transfecting U‐251 MG with the library‐sourced let‐7d‐5p inhibitor, a known regulator of HMGA2 36. A statistically significant upregulation of HMGA2 expression was observed at all concentrations (Figure S4A), indicating that our inhibitor library was functional. These findings suggest a potential compensatory role in the regulation of PrPC expression by endogenous miRNAs, which could be overcome by simultaneous inhibition of all functionally redundant miRNAs. Alternatively, it is likely that U‐251 MG and CHP‐212 express insufficient quantities of endogenous PrPC‐regulating miRNAs.

While the majority of mimics displayed consistent PrPC down‐ or up‐regulation, three candidates exhibited divergent PrPC regulatory effects in different cell lines (Figure 2B). Each of these opposing effects was attributed to a mimic‐induced altered cell number in a follow‐up viability assessment (Figure S6B). For example, miR‐342‐5p was found to increase cell viability in U‐251 MG, which contrarily may have resulted in death of the already growth saturated CHP‐212 cells. In contrast, miR‐148b‐3p, which was found to increase viability of U‐251 MG cells while simultaneously eliciting PrPC downregulation by targeting the PRNP 3′UTR could exclusively be detected in SH‐SY5Y M4 when contrasted to U‐251 MG (Figure 2B). By this standard, a majority of miRNA mimic candidates eliciting an effect on PrPC via the PRNP 3′UTR would be detectable only in U‐251 MG‐CHP‐212 overlaps.

Hits predominantly reduce steady state PRNP mRNA levels

We first sought to determine whether the regulatory actions of our candidate mimics on PrPC were independent of any miRNA‐induced alterations in cell growth. To do so, we transfected mimics into U‐251 MG alongside scrambled negative‐ as well as cell death‐inducing positive control siRNAs, and assessed changes in viability. Based on our cutoff criteria, no miRNAs decreased cell viability whereas six out of the 19 mimic candidates increased cell viability (Figure S6B). However, out of these 6 mimics only miR‐342‐5p and miR‐4802‐5p displayed a concomitant PrPC increase (Figure S6A). These two mimic candidates are therefore likely to increase PrPC levels due to increased cell viability. The remaining 17 mimics were considered high‐confidence hits regulating PrPC independently of cell count.

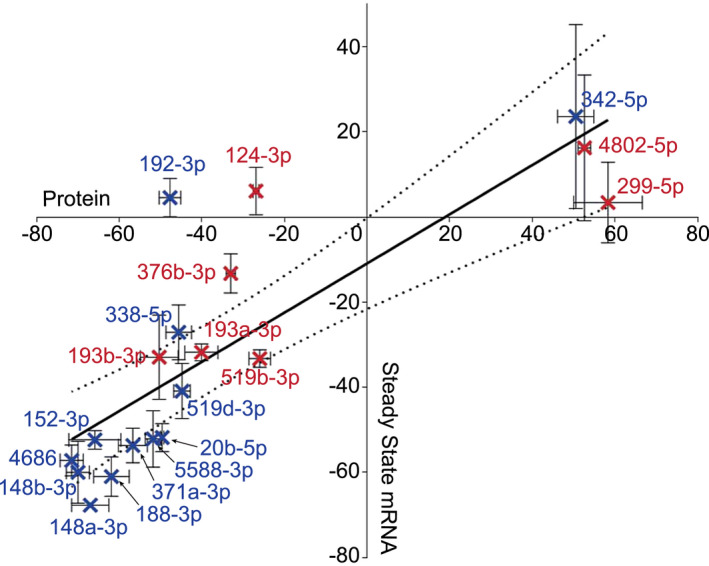

In order to assess whether hits elicited translational repression or mRNA degradation, we assessed steady‐state PRNP mRNA levels. RNA was extracted at the same 72 h time point at which we measured PrPC protein levels, as miRNA‐target interactions often initially result in translational repression followed by mRNA degradation 6. All but three hits were found to down‐regulate PRNP mRNA (Figure S6C). Moreover, the degree of mRNA regulation correlated strongly with the degree of protein regulation (R 2: 0.679) for all candidate mimics (Figure 3), suggesting that the majority of hits function either directly via degradation of PRNP mRNA or indirectly via transcriptional regulation. miR‐124‐3p, miR‐192‐3p and miR‐299‐5p altered PrPC protein but not PRNP mRNA levels, indicating that these hits regulate PrPC either by inhibiting/activating PRNP translation directly, or by regulating a PrPC interactor.

Figure 3.

Relationship between expression of PRNP mRNA and PrPC protein in cells treated with miRNA mimics. Correlation coefficient of the linear regression analysis between PrPC protein (N = 3, Standard error of the mean (SEM) error bars) and steady state PRNP mRNA (N = 3, Standard error of the mean (SEM) error bars) was R 2: 0.679 with 95% confidence intervals. This suggests that miRNA mimic‐driven regulation of PrPC results from degradation of the PRNP transcript. Blue crosses represent CHP‐212, while red crosses represent SH‐SY5Y M4 screen overlaps. Axis values indicate changes in expression relative to respective controls.

miRNA Target Sites Abundant in PRNP 3′UTR

To determine whether the miRNAs identified by our screen regulate PrPC in a direct or indirect manner, we examined TargetScan7.2 (www.targetscan.org) predicted miRNA target sites within the PRNP 3′UTR (Table 1). Of the 13 predicted miRNAs with broadly conserved sites, three miRNAs, namely miR‐148a‐3p, miR‐148b‐3p and miR‐152‐3p were among our hits. Additionally, of 447 miRNAs with poorly conserved sites a further nine hits, namely miR‐20b‐5p, miR‐188‐3p, miR‐338‐5p, miR‐519d‐3p, miR‐4686, miR‐5588‐3p, miR‐193a‐3p, miR‐193b‐3p and miR‐519b‐3p were predicted to bind the PRNP 3′UTR. Two screening hits, namely miR‐371a‐3p and miR‐376b‐3p that were not predicted to harbor binding sites in the 3′UTR, did however have closely related family members miR‐371b‐3p and miR‐376c‐3p that were predicted to possess poorly conserved target sites therein. Interestingly, none of the miRNAs that induced discordant changes in steady state mRNA and PrPC protein levels had a predicted binding site in the PRNP 3′UTR. We further examined CLIP datasets for putative miRNA binding sites of all hits (Table 1). These further confirmed the absence of target sites for either miR‐124‐3p or miR‐192‐3p, but indicated binding of miR‐299‐5p to the PRNP CDS. Overall 14 miRNAs are predicted to bind the PRNP 3′UTR by targeting 9 sequences.

Table 1.

TargetScan7.2 predicted target sites of mimic candidates with PRNP 3′UTR. Units in brackets indicate the number of predicted interaction sites when using poorly conserved miRNA family criteria. CLIP detected miRNA‐PRNP interactions and their respective target sites in PRNP transcript (Ensembl ID:ENST00000379440.8) are also illustrated. Underscores indicate binding to the CDS and bold lettering indicates a closely related miRNA family member.

| Hits | Predicted | CLIP Site | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20b‐5p | Yes (1) | 2279‐2307 | Boudreau RL et al 9 |

| 148a‐3p | Yes (2) | 2466‐2488 | Balakrishnan I et al 3 |

| 148b‐3p | Yes (2) | 1186‐1193, 2466‐2488 | Boudreau RL et al 9 |

| 152‐3p | Yes (2) | 2464‐2488 | Balakrishnan I et al 3 |

| 188‐3p | Yes (1) | No | N/A |

| 192‐3p | No | No | N/A |

| 338‐5p | Yes (2) | 2234‐2253 | Balakrishnan I et al 3 |

| 342‐5p | No | No | N/A |

| 371a‐3p | 371b‐3p (1) | No | N/A |

| 519d‐3p | Yes (1) | 2289‐2307 | Balakrishnan I et al 3 |

| 4686 | Yes (1) | No | N/A |

| 5588‐3p | Yes (1) | No | N/A |

| 124‐3p | No | No | N/A |

| 193a‐3p | Yes (1) | 1276‐1284 | Balakrishnan I et al 3 |

| 193b‐3p | Yes (1) | No | N/A |

| 299‐5p | No | 581‐609 | Balakrishnan I et al 3 |

| 376b‐3p | 376c‐3p (1) | 2302‐2321 | Boudreau RL et al 9 |

| 519b‐3p | Yes (1) | No | N/A |

| 4802‐5p | No | No | N/A |

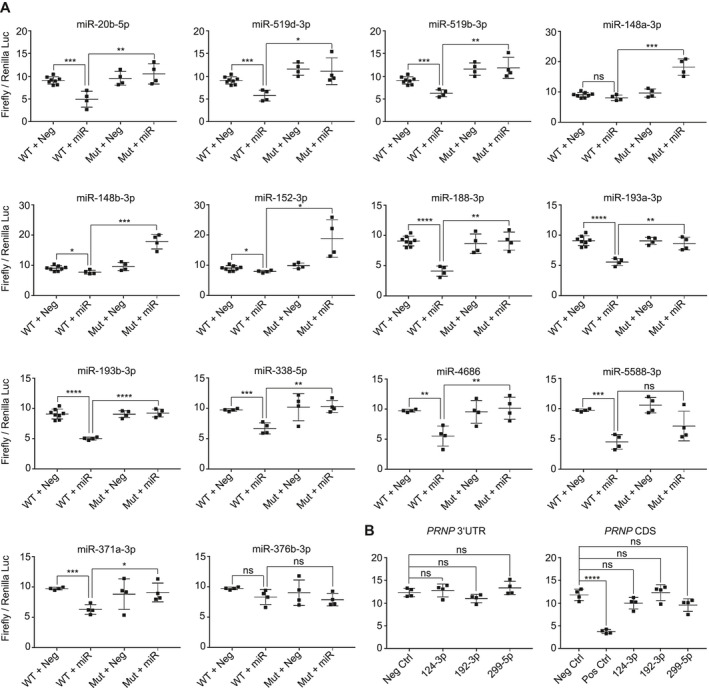

In order to confirm putative miRNA target sites and validate a miRNA‐mediated regulation of protein expression through these sites, we utilized a common dual‐luciferase reporter assay. The wild type (wt) or mutant 3′UTR or wt CDS of PRNP was cloned downstream of the Firefly luciferase CDS. After normalization with Renilla luciferase, which acts as an internal control, the Firefly luciferase signal acts as a proxy for miRNA function. Plasmids harboring the full‐length wt PRNP 3′UTR, 9 mutant forms thereof (Table S1), or the full‐length PRNP CDS were co‐transfected into HEK‐293T with respective mimics.

miR‐148a‐3p, miR‐148b‐3p and miR‐152‐3p, only had a minor or no significant effect on the wt PRNP 3′UTR reporter (Figure 4), despite CLIP data indicating that these miRNAs bind the PRNP 3′UTR 3, 9. However, when co‐transfecting these mimics with their respective mutant reporter, we observed significant signal increases relative to the wt 3′UTR reporter. Differences in wt and mutant reporters were only observed in the presence of mimics, suggesting that these three miRNA directly regulate the PRNP 3′UTR. Notably, sequence alignment using Clustal Omega (www.ebi.ac.uk) revealed that all three of these miRNAs are partially complementary to the Renilla luciferase CDS, potentially accounting for the lack of effect observed in the wt PRNP 3′UTR reporter. miR‐20b‐5p, miR‐188‐3p, miR‐338‐5p, miR‐371a‐3p, miR‐519d‐3p, miR‐519b‐3p, miR‐4686, miR‐193a‐3p, miR‐193b‐3p and miR‐5588‐3p all elicited a significant signal reduction when co‐transfected with the wt PRNP 3′UTR reporter. Moreover, these effects were mitigated when the wt 3′UTR construct was replaced with respective mutant reporters for all but miR‐5588‐3p, thereby confirming that 12 out of the 14 predicted sites are functional targets for miRNA‐mediated PrPC down‐regulation. It is feasible that the miR‐5588‐3p‐induced effect could not be inhibited when co‐transfecting this mimic with its mutant reporter construct due to an additional unpredicted 3′UTR target site.

Figure 4.

Reporter assay confirms predicted PRNP 3′UTR sites as targets for majority of hits. A. Co‐transfection of mimics with wt PRNP 3′UTR or respective mutation harboring reporters found that 12 out of 14 TargetScan7.2 predictions were functional sites for miRNAs. Only miR‐376b‐3p did not significantly regulate Firefly luciferase via the 3′UTR and only miR‐5588‐3p could not be confirmed to elicit its effect through its prospective target site. B. Assessment of miR‐124‐3p, 192‐3p and 299‐5p with wt PRNP 3′UTR or CDS reporters found that none of these miRNAs significantly regulated Firefly luciferase through either site.

Although miR‐371a‐3p and miR‐376b‐3p were only derivatively predicted to bind the PRNP 3′UTR, we assessed whether they could evoke an effect via the wt 3′UTR reporter. We found that miR‐371a‐3p significantly regulated the PRNP 3′UTR reporter in a site‐specific manner, whereas miR‐376b‐3p had no effect. The lack of miR‐376b‐3p‐mediated regulation may be due to its altered seed region sequence relative to miR‐376c‐3p, which was predicted to bind the PRNP 3′UTR. We also examined whether miR‐124‐3p, miR‐192‐3p or miR‐299‐5p could elicit an effect via either the PRNP 3′UTR or the CDS, but found that none of these mimics significantly regulated either the wt 3′UTR or CDS reporter (Figure 4). In conclusion, our reporter assays revealed that 13 out of the 17 screening hits had functional target sites within the PRNP 3′UTR, while the remaining 4 PrPC regulators could not be confirmed to regulate PRNP in a direct manner (summarized in Table 2).

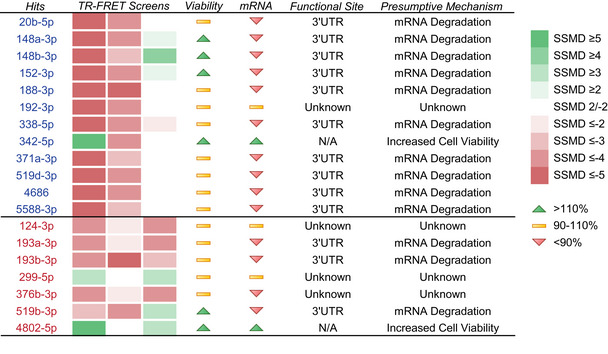

Table 2.

Compilation of hit‐mediated effects. Heat map of SSMD scores in U‐251 MG (column 1), CHP‐212 (column 2) and SH‐SY5Y M4 (column 3) screens. Cell viability and PRNP mRNA values are coded according to a ≥10% increase (green arrow), ≥10% decrease (red arrow) or no change above/below ≤10% (yellow bar) relative to negative controls. Reporter‐confirmed target sites and presumptive modes of miRNA action on PrPC are also listed. Blue and red fonts represent CHP‐212 and SH‐SY5Y M4 overlaps with U‐251 MG screen, respectively.

|

Discussion

The current study exhaustively explores and validates functional roles of PrPC‐regulating miRNAs. This was accomplished by developing a robust high‐throughput arrayed screening platform that assessed direct and indirect effects of the human miRNAome on PrPC levels. Selection of a suitable cell line that produces reproducible results, as revealed by control‐derived Z′‐Factors, is a prerequisite for successful screening. We detected 17 high‐confidence miRNA mimic hits, 13 of which were found to function directly by binding to the PRNP 3′UTR and induce transcript degradation. Crucially, the degree to which miRNA mimics regulated PrPC protein correlated well (R 2: 0.679) with the degree of PRNP mRNA expression change (Figure 3). These results are consistent with the observation that 66%–90% miRNA‐mediated repression can be attributed to mRNA destabilization 15.

Hit‐induced PrPC reduction found in U‐251 MG and CHP‐212 was not generally reflected in SH‐SY5Y M4 cells (Table 2). This was expected for miRNAs acting through the PRNP 3′UTR, which is not present in SH‐SY5Y M4. An exception were miR‐193a‐3p and miR‐193b‐3p, which displayed decreased PrPC levels in all three cell lines. This suggests that these miRNAs may induce PrPC regulation through multiple pathways.

Four of our hits could not be confirmed to regulate PRNP via its 3′UTR or CDS and were therefore deemed indirect regulators of PrPC expression. Owing to the high number of miRNA targets that may function as single intermediary interactors or in complex regulatory cascades, it would be challenging to identify such indirect regulatory pathways. However, based on the unchanged PRNP mRNA but significantly altered PrPC protein levels upon transfection with miR‐124‐3p, miR‐192‐3p or miR‐299‐5p mimics, we speculate that these three miRNAs may function by regulating PrPC protein stability and/or turnover. Conversely, miR‐376b‐3p, which was found to decrease both mRNA and protein levels, may possibly function by targeting a PRNP‐regulating transcription factor.

As PrPC is essential for scrapie‐induced neurotoxicity 10, and the depletion of neuronal PrPC is known to prevent disease and reverse accompanying pathognomonic spongiosis occurring during prion infection 28, reduction or depletion of endogenous PrPC might constitute a therapeutic option for TSEs. Moreover, as conditional post‐natal knockout 29 or complete ablation 34 of PrPC results in relatively mild phenotypes 2, 11, the modulation of PrPC levels does in fact represent a compelling therapeutic approach. Notably, the pleiotropic nature of miRNAs provides them with one important therapeutic advantage over siRNAs, as it enables single miRNAs to modulate multiple possibly disease‐linked pathways in complex multigenic conditions.

Applying miRNA functional information to expression datasets has the potential to uncover novel miRNA‐regulated pathways that may play important, if not causal, roles in disease. miR‐124‐3p, one of the most abundant miRNAs in the brain, is known to be deregulated in multiple CNS disorders 44. In prion disease specifically, miR‐124‐3p has been shown to become significantly upregulated in mouse hippocampal CA1 neurons at 70 and 90 days post scrapie infection, while contrarily becoming downregulated at 130 and 160 days post infection 27. In human post‐mortem sCJD frontal cortical and cerebellar samples, miR‐124‐3p was similarly found to be decreased relative to control tissues 23. This conserved temporal regulation in miR‐124‐3p expression indicates a potential role of this miRNA in prion disease pathology.

Both miR‐148a‐3p and 148b‐3p are highly expressed in the human brain 35. These two mimic hits elicited the strongest down‐regulatory effect on PrPC protein and PRNP mRNA levels (Figure 3), indicating that these miRNAs may mediate endogenous suppression of the prion protein in healthy brains. However, neither of these miRNAs has been found to be deregulated during prion infection.

The current study marks the first to discover a functional indirect regulatory role of miR‐124‐3p on PrPC expression levels. No other screening hit except for miR‐124‐3p has been documented as being consistently altered during prion disease. miR‐146a‐5p and miR‐342‐3p, which have been found to be deregulated in multiple TSEs 25, 33, 40, 41, had no effect on PrPC expression levels.

There is a growing consensus that modulation of PrPC may represent the most realistic therapeutic approach for treatment of prion diseases, which may have particular prophylactic value for genetic PRNP mutation carriers 32. Furthermore, as the depletion of PrPC has been found to cause demyelination in the peripheral nervous system 11 through reduced excitation of its receptor Gpr126 20, these considerations highlight the importance of elucidating PrPC‐regulatory mechanisms in physiological conditions. In‐depth investigations, not only of animal models but also observational studies in human cohorts are warranted. The ultimate goal of such studies would be to test whether manipulation of the miRNA landscape, or its downstream effectors in the case of indirectly acting miRNAs, might be pharmacologically exploitable for the treatment of patients at risk of prion diseases.

Contributorship Statement

AA and DP conceived the study. ES, IX and ME conceptualized the screen quality control and designed templates for dispensing the miRNA library and the controls into microplates. ES authored the open source HTS software tool. ME assisted with troubleshooting of the robotic high‐throughput screening platform and provided advice on screening optimizations. VE generated the SH‐SY5Y PRNP ‐/‐ and SH‐SY5Y M4 clones. CS provided general project supervision and support with molecular cloning. DP designed experiments, carried them out, and analyzed their results. DP, AA and CS wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1 . Putative target site mutations in reporters. TargetScan7.2 predicted interaction sites of screening hits with 3′UTR of PRNP (Ensembl ID: ENST00000379440.8). wt target and mutated target sequences in reporter constructs are listed. Bold lettering represents a related miRNA family member and red font indicates altered nucleotides in reporter. Blue and red font indicate CHP‐212 and SH‐SY5Y M4 overlaps with U‐251 MG screen, respectively.

Table S2 . Complete miRNA mimic screening datasets in U‐251 MG, CHP‐212 and SH‐SY5Y M4. Tables show sample ID, replicate Net FRET signals, Net FRET signal mean, Net FRET signal standard deviation (SD), sample SSMD, log2 fold change, P‐values, miRNA accession numbers, corresponding mature miRNA name, and mature miRNA sequence.

Table S3 . Complete miRNA inhibitor screening datasets in U‐251 MG and CHP‐212. Tables show sample ID, replicate Net FRET signals, Net FRET signal mean, Net FRET signal standard deviation (SD), sample SSMD, log2 fold change, P‐values, target miRNA accession numbers, target miRNA name, and target miRNA sequence.

Figure S1 . SH‐SY5Y PRNP ‐/‐ clone sequencing report. Sanger sequencing trace data shows a deletion of the second adenine in the third codon of the PRNP CDS (chr20: 4,699,229), in exon 2 (Ensembl ID:ENST00000379440.8) in SH‐SY5Y PRNP ‐/‐ clone.

Figure S2 . High miRNA mimic screening replicability. A) Western blot PrPC expression in 30 µg of cell lysates (10 µg for SH‐SY5Y M4). B) TR‐FRET PrPC expression in 6 µg cell lysates (N = 4, standard deviation (SD) error bars) using POM2‐Eu and POM1‐APC fluorophores. C) Linear correlation with 95% confidence intervals of biological replicates in U‐251 MG, CHP‐212 and SH‐SY5Y M4 mimic screens with illustrations of respectively expressed transcripts.

Figure S3 . TR‐FRET in culture media vs. media‐removed conditions. Various numbers of SH‐SY5Y M4 cells seeded per well in 30 uL media and incubated for 72 h prior to direct addition of 10 uL 4X lysis buffer (left plot) or media removal followed by addition of 10 uL 1X lysis buffer (right plot). PrPC assessment via TR‐FRET shows reduced replicate variability when applying a media removal step prior to lysis (N = 48, standard deviation (SD) error bars).

Figure S4 . No linear correlation between miRNA inhibitor screen replicates. A) Assessing efficacy of the miRNA inhibitor library by transfecting an inhibitor of let‐7d‐5p, a ubiquitously expressed miRNA known to negatively regulate HMGA2 levels, into U‐251 MG cells at 20, 40 and 60 nM. RT‐qPCR analysis of HMGA2 normalized to ACTB was performed for let‐7d‐5p mimic, let‐7d‐5p inhibitor and non‐targeting siRNA (Neg Ctrl) ‐transfected cells (N = 3, Standard error of the mean (SEM) error bars). A 60 nM concentration of miRNA inhibitors was selected for screening in both U‐251 MG and CHP‐212 cells. B) Histograms displaying positive and negative control signal occurrences (22 per plate across 24 plates) for U‐251 MG (Z′: 0.396) and CHP‐212 (Z′: −0.346) inhibitor screens with illustrations of each respectively expressed transcript. C) Biological triplicate with linear regressions and 95% confidence intervals in U‐251 MG and CHP‐212 inhibitor screens display a clustering of sample replicates, indicating an overall lack of biological effect produced by the inhibitor library.

Figure S5 . Inhibitor screens identify no hits. A) Dual‐flashlight plots displaying SSMD vs. Log2 fold change (FC) in U‐251 MG and CHP‐212 miRNA inhibitor screens with illustrations of expressed transcripts. B) SSMD inhibitor screen overlaps identify 0 hits at low cut‐off criteria among U‐251 MG (SSMD ≥1.5, ≤−1.5) and CHP‐212 (≥1.5, ≤−1.5).

Figure S6 . Hit‐induced effects. A) PrPC protein regulation by hits in U‐251 MG mimic screen (TR‐FRET) normalized to respective controls. B) Cell viability alterations by mimic hits in U‐251 MG (CellTiter‐Glo2.0) normalized to respective controls. Protein regulation coinciding with 10% increased or decreased viability were excluded. C) PRNP mRNA regulation by hits in U‐251 MG (RT‐qPCR using ACTB, TBP and GUSB housekeeping genes) normalized to respective controls. Blue and red crosses indicate CHP‐212 and SH‐SY5Y M4 overlaps with U‐251 MG screen, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rita Moos for POM antibody production and Irina Abakumova for TR‐FRET antibody‐fluorophore conjugation. AA is the recipient of an Advanced Grant of the European Research Council and grants from the Swiss National Research Foundation, the Clinical Research Priority Programs (CRPP) ‘Small RNAs’ and ‘Human Haemato‐Lymphatic Diseases’ of the University of Zurich, SystemsX.ch, and the Swiss Personalized Health Network. miRNA libraries were purchased with CRPP funds. Daniel Pease is the recipient of the Candoc Forschungskredit Nr. FK‐17‐033.

References

- 1. Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW, Bartel DP (2015) Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife 4: e05005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aguzzi A, Baumann F, Bremer J (2008) The prion's elusive reason for being. Annu Rev Neurosci 31:439–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Balakrishnan I, Yang X, Brown J, Ramakrishnan A, Torok‐Storb B, Kabos P et al (2014) Genome‐wide analysis of miRNA‐mRNA interactions in marrow stromal cells. Stem Cells 32:662–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ballmer BA, Moos R, Liberali P, Pelkmans L, Hornemann S, Aguzzi A (2017) Modifiers of prion protein biogenesis and recycling identified by a highly parallel endocytosis kinetics assay. J Biol Chem 292:8356–8368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barrows NJ, Le Sommer C, Garcia‐Blanco MA, Pearson JL (2010) Factors affecting reproducibility between genome‐scale siRNA‐based screens. J Biomol Screen 15:735–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bazzini AA, Lee MT, Giraldez AJ (2012) Ribosome profiling shows that miR‐430 reduces translation before causing mRNA decay in zebrafish. Science 336:233–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bellingham SA, Coleman BM, Hill AF (2012) Small RNA deep sequencing reveals a distinct miRNA signature released in exosomes from prion‐infected neuronal cells. Nucleic Acids Res 40:10937–10949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boese AS, Saba R, Campbell K, Majer A, Medina S, Burton L et al (2016) MicroRNA abundance is altered in synaptoneurosomes during prion disease. Mol Cell Neurosci 71:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boudreau RL, Jiang P, Gilmore BL, Spengler RM, Tirabassi R, Nelson JA et al (2014) Transcriptome‐wide discovery of microRNA binding sites in human brain. Neuron 81:294–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brandner S, Isenmann S, Raeber A, Fischer M, Sailer A, Kobayashi Y et al (1996) Normal host prion protein necessary for scrapie‐induced neurotoxicity. Nature 379:339–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bremer J, Baumann F, Tiberi C, Wessig C, Fischer H, Schwarz P et al (2010) Axonal prion protein is required for peripheral myelin maintenance. Nat Neurosci 13:310–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bueler H, Fischer M, Lang Y, Bluethmann H, Lipp HP, DeArmond SJ et al (1992) Normal development and behaviour of mice lacking the neuronal cell‐surface PrP protein. Nature 356:577–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bueler H, Raeber A, Sailer A, Fischer M, Aguzzi A, Weissmann C (1994) High prion and PrPSc levels but delayed onset of disease in scrapie‐inoculated mice heterozygous for a disrupted PrP gene. Mol Med 1:19–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Calella AM, Farinelli M, Nuvolone M, Mirante O, Moos R, Falsig J et al (2010) Prion protein and Abeta‐related synaptic toxicity impairment. EMBO Mol Med 2:306–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eichhorn SW, Guo H, McGeary SE, Rodriguez‐Mias RA, Shin C, Baek D et al (2014) mRNA destabilization is the dominant effect of mammalian microRNAs by the time substantial repression ensues. Mol Cell 56:104–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP (2009) Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res 19:92–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gibbings D, Leblanc P, Jay F, Pontier D, Michel F, Schwab Y et al (2012) Human prion protein binds Argonaute and promotes accumulation of microRNA effector complexes. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19:517–524, S1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnson R, Zuccato C, Belyaev ND, Guest DJ, Cattaneo E, Buckley NJ (2008) A microRNA‐based gene dysregulation pathway in Huntington's disease. Neurobiol Dis 29:438–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krol J, Loedige I, Filipowicz W (2010) The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat Rev Genet 11:597–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kuffer A, Lakkaraju AK, Mogha A, Petersen SC, Airich K, Doucerain C et al (2016) The prion protein is an agonistic ligand of the G protein‐coupled receptor Adgrg6. Nature 536:464–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lauren J, Gimbel DA, Nygaard HB, Gilbert JW, Strittmatter SM (2009) Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by amyloid‐beta oligomers. Nature 457:1128–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP (2005) Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Llorens F, Thune K, Marti E, Kanata E, Dafou D, Diaz‐Lucena D et al (2018) Regional and subtype‐dependent miRNA signatures in sporadic Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease are accompanied by alterations in miRNA silencing machinery and biogenesis. PLoS Pathog 14:e1006802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lukiw WJ (2007) Micro‐RNA speciation in fetal, adult and Alzheimer's disease hippocampus. Neuroreport 18:297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lukiw WJ, Dua P, Pogue AI, Eicken C, Hill JM (2011) Upregulation of micro RNA‐146a (miRNA‐146a), a marker for inflammatory neurodegeneration, in sporadic Creutzfeldt‐Jakob disease (sCJD) and Gerstmann‐Straussler‐Scheinker (GSS) syndrome. J Toxicol Environ Health A 74:1460–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maddox CB, Rasmussen L, White EL (2008) Adapting cell‐based assays to the high throughput screening platform. Problems Encountered and Lessons Learned. JALA Charlottesv Va 13:168–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Majer A, Medina SJ, Niu Y, Abrenica B, Manguiat KJ, Frost KL et al (2012) Early mechanisms of pathobiology are revealed by transcriptional temporal dynamics in hippocampal CA1 neurons of prion infected mice. PLoS Pathog 8:e1003002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mallucci G, Dickinson A, Linehan J, Klohn PC, Brandner S, Collinge J (2003) Depleting neuronal PrP in prion infection prevents disease and reverses spongiosis. Science 302:871–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mallucci GR, Ratte S, Asante EA, Linehan J, Gowland I, Jefferys JG, Collinge J (2002) Post‐natal knockout of prion protein alters hippocampal CA1 properties, but does not result in neurodegeneration. EMBO J 21:202–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mayr C, Hemann MT, Bartel DP (2007) Disrupting the pairing between let‐7 and Hmga2 enhances oncogenic transformation. Science 315:1576–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Meister G, Landthaler M, Patkaniowska A, Dorsett Y, Teng G, Tuschl T (2004) Human Argonaute2 mediates RNA cleavage targeted by miRNAs and siRNAs. Mol Cell 15:185–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Minikel EV, Vallabh SM, Lek M, Estrada K, Samocha KE, Sathirapongsasuti JF et al (2016) Quantifying prion disease penetrance using large population control cohorts. Sci Transl Med 8:322ra9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Montag J, Hitt R, Opitz L, Schulz‐Schaeffer WJ, Hunsmann G, Motzkus D (2009) Upregulation of miRNA hsa‐miR‐342‐3p in experimental and idiopathic prion disease. Mol Neurodegener 4:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nuvolone M, Hermann M, Sorce S, Russo G, Tiberi C, Schwarz P et al (2016) Strictly co‐isogenic C57BL/6J‐Prnp‐/‐ mice: a rigorous resource for prion science. J Exp Med 213:313–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Panwar B, Omenn GS, Guan Y (2017) miRmine: a database of human miRNA expression profiles. Bioinformatics 33:1554–1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Park SM, Shell S, Radjabi AR, Schickel R, Feig C, Boyerinas B et al (2007) Let‐7 prevents early cancer progression by suppressing expression of the embryonic gene HMGA2. Cell Cycle 6:2585–2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pfeifer A, Eigenbrod S, Al‐Khadra S, Hofmann A, Mitteregger G, Moser M et al (2006) Lentivector‐mediated RNAi efficiently suppresses prion protein and prolongs survival of scrapie‐infected mice. J Clin Invest 116:3204–3210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reczko M, Maragkakis M, Alexiou P, Grosse I, Hatzigeorgiou AG (2012) Functional microRNA targets in protein coding sequences. Bioinformatics 28:771–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Saba R, Goodman CD, Huzarewich RL, Robertson C, Booth SA (2008) A miRNA signature of prion induced neurodegeneration. PLoS One 3:e3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saba R, Gushue S, Huzarewich RL, Manguiat K, Medina S, Robertson C, Booth SA (2012) MicroRNA 146a (miR‐146a) is over‐expressed during prion disease and modulates the innate immune response and the microglial activation state. PLoS One 7:e30832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sanz Rubio D, Lopez‐Perez O, de Andrés Pablo Á, Bolea R, Osta R, Badiola JJ et al (2017) Increased circulating microRNAs miR‐342‐3p and miR‐21‐5p in natural sheep prion disease. J Gen Virol 98:305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Scheckel C, Aguzzi A (2018) Prions, prionoids and protein misfolding disorders. Nat Rev Genet 19:405–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schurmann N, Trabuco LG, Bender C, Russell RB, Grimm D (2013) Molecular dissection of human Argonaute proteins by DNA shuffling. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20:818–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sun Y, Luo ZM, Guo XM, Su DF, Liu X (2015) An updated role of microRNA‐124 in central nervous system disorders: a review. Front Cell Neurosci 9:193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wen J, Parker BJ, Jacobsen A, Krogh A (2011) MicroRNA transfection and AGO‐bound CLIP‐seq data sets reveal distinct determinants of miRNA action. RNA 17:820–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR (1999) A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J Biomol Screen 4:67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang XD (2007) A new method with flexible and balanced control of false negatives and false positives for hit selection in RNA interference high‐throughput screening assays. J Biomol Screen 12:645–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang XD (2009) A method for effectively comparing gene effects in multiple conditions in RNAi and expression‐profiling research. Pharmacogenomics 10:345–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 . Putative target site mutations in reporters. TargetScan7.2 predicted interaction sites of screening hits with 3′UTR of PRNP (Ensembl ID: ENST00000379440.8). wt target and mutated target sequences in reporter constructs are listed. Bold lettering represents a related miRNA family member and red font indicates altered nucleotides in reporter. Blue and red font indicate CHP‐212 and SH‐SY5Y M4 overlaps with U‐251 MG screen, respectively.

Table S2 . Complete miRNA mimic screening datasets in U‐251 MG, CHP‐212 and SH‐SY5Y M4. Tables show sample ID, replicate Net FRET signals, Net FRET signal mean, Net FRET signal standard deviation (SD), sample SSMD, log2 fold change, P‐values, miRNA accession numbers, corresponding mature miRNA name, and mature miRNA sequence.

Table S3 . Complete miRNA inhibitor screening datasets in U‐251 MG and CHP‐212. Tables show sample ID, replicate Net FRET signals, Net FRET signal mean, Net FRET signal standard deviation (SD), sample SSMD, log2 fold change, P‐values, target miRNA accession numbers, target miRNA name, and target miRNA sequence.

Figure S1 . SH‐SY5Y PRNP ‐/‐ clone sequencing report. Sanger sequencing trace data shows a deletion of the second adenine in the third codon of the PRNP CDS (chr20: 4,699,229), in exon 2 (Ensembl ID:ENST00000379440.8) in SH‐SY5Y PRNP ‐/‐ clone.

Figure S2 . High miRNA mimic screening replicability. A) Western blot PrPC expression in 30 µg of cell lysates (10 µg for SH‐SY5Y M4). B) TR‐FRET PrPC expression in 6 µg cell lysates (N = 4, standard deviation (SD) error bars) using POM2‐Eu and POM1‐APC fluorophores. C) Linear correlation with 95% confidence intervals of biological replicates in U‐251 MG, CHP‐212 and SH‐SY5Y M4 mimic screens with illustrations of respectively expressed transcripts.

Figure S3 . TR‐FRET in culture media vs. media‐removed conditions. Various numbers of SH‐SY5Y M4 cells seeded per well in 30 uL media and incubated for 72 h prior to direct addition of 10 uL 4X lysis buffer (left plot) or media removal followed by addition of 10 uL 1X lysis buffer (right plot). PrPC assessment via TR‐FRET shows reduced replicate variability when applying a media removal step prior to lysis (N = 48, standard deviation (SD) error bars).

Figure S4 . No linear correlation between miRNA inhibitor screen replicates. A) Assessing efficacy of the miRNA inhibitor library by transfecting an inhibitor of let‐7d‐5p, a ubiquitously expressed miRNA known to negatively regulate HMGA2 levels, into U‐251 MG cells at 20, 40 and 60 nM. RT‐qPCR analysis of HMGA2 normalized to ACTB was performed for let‐7d‐5p mimic, let‐7d‐5p inhibitor and non‐targeting siRNA (Neg Ctrl) ‐transfected cells (N = 3, Standard error of the mean (SEM) error bars). A 60 nM concentration of miRNA inhibitors was selected for screening in both U‐251 MG and CHP‐212 cells. B) Histograms displaying positive and negative control signal occurrences (22 per plate across 24 plates) for U‐251 MG (Z′: 0.396) and CHP‐212 (Z′: −0.346) inhibitor screens with illustrations of each respectively expressed transcript. C) Biological triplicate with linear regressions and 95% confidence intervals in U‐251 MG and CHP‐212 inhibitor screens display a clustering of sample replicates, indicating an overall lack of biological effect produced by the inhibitor library.

Figure S5 . Inhibitor screens identify no hits. A) Dual‐flashlight plots displaying SSMD vs. Log2 fold change (FC) in U‐251 MG and CHP‐212 miRNA inhibitor screens with illustrations of expressed transcripts. B) SSMD inhibitor screen overlaps identify 0 hits at low cut‐off criteria among U‐251 MG (SSMD ≥1.5, ≤−1.5) and CHP‐212 (≥1.5, ≤−1.5).

Figure S6 . Hit‐induced effects. A) PrPC protein regulation by hits in U‐251 MG mimic screen (TR‐FRET) normalized to respective controls. B) Cell viability alterations by mimic hits in U‐251 MG (CellTiter‐Glo2.0) normalized to respective controls. Protein regulation coinciding with 10% increased or decreased viability were excluded. C) PRNP mRNA regulation by hits in U‐251 MG (RT‐qPCR using ACTB, TBP and GUSB housekeeping genes) normalized to respective controls. Blue and red crosses indicate CHP‐212 and SH‐SY5Y M4 overlaps with U‐251 MG screen, respectively.