Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS:

The benefits of highly effective therapies for chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) or HCV infection can only be realized if infected individuals are identified and linked to care. We sought to identify gaps in awareness of diagnosis of HBV or HCV infection in a population-based sample of adults living in the United States (US).

METHODS:

Using National Health and Nutrition Examinations Surveys data, we examined factors associated with HBV and HCV awareness. Participants surveyed from 2013 through 2016, age ≥20 years, with complete serologic analyses were included. HBV and HCV infections were defined by detection of serum HBsAg and anti-HCV, respectively. The primary outcome was awareness of infection—if participants replied “yes” to the question: “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you have hepatitis B or C?”

RESULTS:

Of 14,745 participants, 68 had HBV and 211 had HCV infection, corresponding to prevalence values of 0.7% and 1.8%, respectively. Among HBV-infected persons, 32% reported awareness, and 28% of aware persons reported treatment. Among HCV-infected persons, 49% reported awareness, 45% of aware persons were treated, and 59% of treated patients achieved a sustained virologic response. Factors associated with greater awareness in multivariable models included US citizenship, higher education, and abnormal level of alanine aminotransferase for HBV-infected participants and non-Hispanic race, income above the poverty line, not married, and history of injection drug use for HCV-infected participants.

CONCLUSIONS:

Fewer than half of US adults with HBV or HCV infection are aware of their infection. Opportunities to increase awareness include provider education on cut-off values for abnormal level of alanine aminotransferase that should prompt screening, and expansion of existing screening interventions to under-recognized at-risk groups.

Keywords: ALT, Viral Hepatitis, Linkage to Care, Cascade

Availability of effective hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccines and curative hepatitis C virus (HCV) therapies has made the elimination of chronic viral hepatitis an attainable public health goal. In the United States alone, a combined 5 million individuals are estimated to be chronically infected with viral hepatitis.1,2 Delays in diagnosis of chronic viral hepatitis can result in significant morbidity and mortality from cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, contributing to about 20,000 deaths in the United States annually and high health care utilization.3 Movement of infected individuals through the viral hepatitis care cascade is first contingent on awareness of diagnosis, often the step with the largest drop-off in the cascade.4 Awareness subsequently requires engagement in care, which is important regardless of treatment eligibility, because benefits include counselling on viral transmission, appropriate vaccinations, fibrosis assessment, and screening for hepatocellular carcinoma if indicated.5,6

Lack of awareness of HBV and HCV diagnoses among affected individuals in the United States is a pressing issue. The asymptomatic nature of chronic HBV and HCV infection until development of end-stage liver disease dictates a reliance on screening for case-finding and places a disproportionate burden on providers and public health campaigns. Prior estimates of awareness of HBV and HCV infection among US adults were performed in high-risk populations, such as Asian immigrants for HBV7 and injection drug users for HCV8; these estimates are prone to selection bias and cannot be generalized to the broader US population. Studies have also been restricted to either HBV7 or HCV9 infection. Although these viruses impact populations with distinct risk profiles and treatment challenges, the downstream consequences are similar and a comparison of awareness between the 2 may be informative.

We used recent data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a cross-sectional survey of adults living in the United States, to characterize the current chronic viral hepatitis cascade in a population-based cohort. In addition, we compared existing gaps in awareness among US adults with the objective of identifying disease-specific targets for future high-impact interventions.

Methods

Survey

NHANES is a stratified and multistage survey of a representative, noninstitutionalized, and civilian US population carried out by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) in 2-year cycles since 1999. Approximately 5000 individuals are randomly selected every cycle to undergo a screening questionnaire at home, followed by a standardized physical examination in a mobile examination center that includes blood and urine laboratory testing. Oversampling of key subgroups of interest can change each cycle and allows for increased precision in estimates relating to these populations. Starting from 2011, Asians were oversampled. Before 2013, a hepatitis C follow-up questionnaire was administered 6 months after examination to participants who tested positive for HCV. Starting in 2013, this questionnaire was replaced by a viral hepatitis questionnaire that was given to all participants during their home screening interview and included questions regarding hepatitis B. More detailed information regarding survey methodology and analysis is available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

Study Cohort

All NHANES participants greater than or equal to 20 years surveyed between 2013 and 2016 with complete laboratory testing for viral hepatitis were included. HBV infection was defined as a positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and core antibody (anti-HBc, total). HBV DNA testing was not performed. Although HCV RNA testing was available in those with a positive hepatitis C antibody (anti-HCV), we defined HCV infection as a positive anti-HCV alone because we could not differentiate between spontaneous clearance or sustained virologic response based on available testing. Accordingly, those with a positive anti-HCV but negative HCV RNA were considered to have attained sustained virologic response if they reported prior treatment. Demographic and clinical covariates (defined in Supplementary Table 1) for analysis were obtained from NHANES public use files on the NCHS Web site.

Laboratory Assays

Qualitative detection of HBsAg and anti-HBc for HBV infection were performed using immunoassays (Ortho CD VITROS Anti-HBc and HBsAg test, Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, Raritan, NJ). An initial antibody screening test (VITROS Anti-HCV test, Ortho Clinical Diagnostics) was performed for HCV. All anti-HCV-positive tests were first tested for RNA using an in vitro nucleic acid amplification test (COBAS AMPLICOR HCV MONITOR Test version 2.0, Roche Diagnostics Corp, Indianapolis, IN). Only RNA-negative samples were tested with an antibody confirmation test using an enzyme immunoassay (INNO-LIA HCV Score Assay, Fujirebio Europe, Gent, Belgium). Samples with an indeterminate antibody confirmation test result were designated as missing.

Outcome

The following questions were asked in the viral hepatitis questionnaire: “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you have hepatitis B (or C)?”; and those answering “yes” were then asked, “Please look at the drugs on this card that are prescribed for hepatitis B (or C). Were you ever prescribed any medicine to treat hepatitis B (or C)?” The primary outcome was HBV/HCV awareness defined as answering “Yes” to question 1. Treatment was defined as answering “Yes” to question 2. Participants that refused to answer or answered “Do not know” to either question were considered missing.

Statistical Analysis

To estimate the equivalent number of infections in the US noninstitutionalized population, unadjusted prevalence estimates expressed as a percentage were multiplied to population totals provided by NCHS averaged over the time period of interest.

All analyses were done accounting for survey weights and complex survey design. Differences between baseline characteristics were examined using Student t tests for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Population counts of HBV- and HCV-infected were estimated using unadjusted prevalence estimates expressed as a percentage multiplied to population totals obtained from NCHS and averaged over the time period studied. Covariates associated with awareness were examined in univariate models and those with P < .10 in univariate models were included in multivariable logistic regression models. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA v14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Viral Hepatitis Prevalence and Cascade of Care

Of 20,146 NHANES participants who completed the screening interview between 2013 and 2016, 11,488 (59%) were equal to or older than 20 years (Supplementary Figure 1). Sixty-eight (0.7%) of 10,402 participants with HBV serologies had positive anti-HBc and HBsAg testing, corresponding to an estimated HBV prevalence of 0.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.5%–0.9%) in the noninstitutionalized civilian adult US population between 2013 and 2016. Of 10,343 participants with HCV serologies, 211 (2.0%) tested positive for anti-HCV, corresponding to an estimated HCV prevalence of 1.8% (95% CI, 1.5%–2.1%). Of those who tested positive for anti-HCV, HCV RNA was also positive in 52%. Prevalence of active HCV viremia was 0.9% (95% CI, 0.8%–1.1%). Among foreign-born participants, the prevalence of HBV was 2.3% (95% CI, 1.7%–3.2%) and HCV was 0.8% (95% CI, 0.5%–1.3%). Conversely, HBV and HCV prevalence was 0.3% (95% CI, 0.2%–0.5%) and 2.1% (95% CI, 1.6%–2.7%) among US-born, respectively.

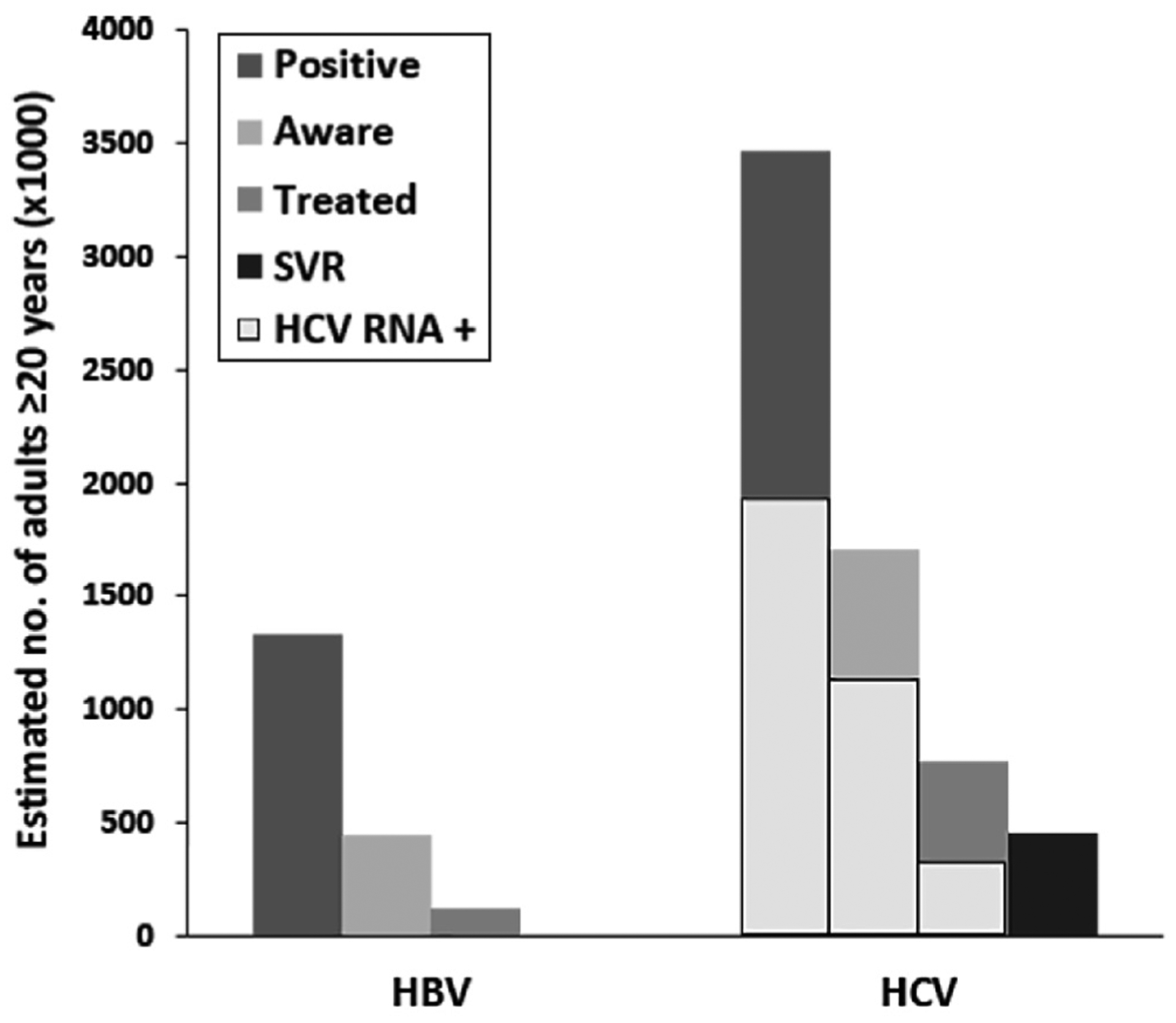

Figure 1 compares the cascades of care for HBV and HCV infection. An estimated 1.3 million (95% CI, 0.9–1.7 million) persons in the United States were HBV-infected. 34% (95% CI, 19%–54%) of HBV-infected persons reported awareness and 28% (95% CI, 10%–57%) of aware persons reported ever having HBV treatment. In contrast, 3.5 million (95% CI, 2.9–4.1 million) US adults were estimated to have HCV infection. Of these, 49% (95% CI, 41%–58%) reported awareness, 45% (95% CI, 32%–59%) of aware persons reported ever having HCV treatment, and 59% (95% CI, 35%–80%) of treated individuals had achieved sustained virologic response based on HCV RNA testing.

Figure 1.

Cascades of care for HBV and HCV infection in US adults. Figure shows estimates of number of US adults infected, aware of infection, and reported treatment with HBV and HCV infections between 2013 and 2016. Solid gray columns represent the HCV RNA positive subgroup of HCV-infected individuals. Individuals with sustained virologic response are those who are HCV antibody positive and HCV RNA negative with self-reported history of treatment. SVR, sustained virologic response.

Characteristics of US Adults With Viral Hepatitis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of HBV- and HCV-infected NHANES participants are shown in Supplementary Table 2. The mean age of HBV-infected was 49 years compared with 53 years for HCV-infected (P = .18). Most HCV-infected were between 40 and 59 years of age; correspondingly, baby boomers born between 1945 and 1965 comprised 60% of all HCV-infected. HBV-infected were much more likely to be foreign-born (66% vs 8%) and less likely to be US citizens (76% vs 98%) than HCV-infected (all P < .01). Racial composition differed between HBV- and HCV-infected (P < .001). Fifty-two percent of HBV-infected were Asian, followed by 20% non-Hispanic white, and 20% non-Hispanic black; 98% of Asians and 75% of blacks with HBV were foreign-born. HCV-infected were 65% white, 15% black, and 12% Hispanic; 65% of His-panics with HCV identified as foreign-born. More HBV-infected (68%) than HCV-infected (40%) were married (P = .03). A high proportion of both HBV- and HCV-infected reported having insurance (>70%) and access to care (>80%). Injection drug use (IDU) was a major risk factor for 44% of HCV-infected versus 11% of HBV-infected (P = .01). An abnormal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was noted in 53% of HBV-infected and 45% of HCV-infected (P = .32).

Differences in Aware and Unaware in Hepatitis B Virus and Hepatitis C Virus Infection

Table 1 shows the characteristics of HBV- and HCV-infected adults stratified by awareness. For US adults with HBV infection, age, sex, and race were similar between aware and unaware groups. Although the proportion foreign-born were nearly equivalent, a higher percentage of HBV-aware individuals were US citizens (91% vs 68%; P = .02). Aware HBV-infected adults were more often married (85% vs 60%; P = .04) and more highly educated (76% with some college or above vs 50% unaware; P = .05). A lower mean platelet count was present in aware individuals (179 vs 217; P < .001). Specific risk factors for HBV (IDU, men who have sex with men [MSM], blood transfusion) were reported at similar proportions in HBV aware and unaware. Aware HCV-infected adults were more often baby boomers than unaware (70% vs 48%; P = .07), less often below the federal poverty line (25% vs 51%; P = .07), and less often married (25% vs 51%; P = .07). Unaware individuals with HCV were more likely to be foreign-born than aware (11% vs 4%; P = .02), and less likely to be non-English speakers (3% vs 9%; P = .05). Higher proportions of HCV aware reported history of IDU (53% vs 33%; P = .03) or MSM (17% vs 2%; P = .01) as risk factors. Other baseline factors were similar among HCV-infected.

Table 1.

Comparison of Weighted Characteristics in Individuals With and Without Awareness of HBV (n = 68) and HCV Infection (n = 206)

| Characteristics | HBV | HCV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aware n = 21 | Not aware n = 47 | P value | Aware n = 93 | Not aware n = 113 | P value | |

| Mean age, y | 50.5 ± 5.3 | 48.7 ± 2.8 | .75 | 54.2 ± 1.6 | 51.7 ± 1.6 | .34 |

| Baby boomer, % | — | — | 69.8 ± 8.1 | 48.4 ± 6.6 | .07 | |

| Male, % | 50.6 ± 15.8 | 52.8 ± 7.7 | .90 | 65.2 ± 7.0 | 53.1 ± 8.5 | .19 |

| Race, %a | .49 | .16 | ||||

| Mexican or other Hispanic | 0 | 7.4 ± 5.2b | 6.6 ± 2.1b | 16.1 ± 3.8 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 26.7 ± 20.2b | 17.0 ± 8.9b | 72.1 ± 4.2 | 56.8 ± 7.7 | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 8.1 ± 5.8b | 25.5 ± 8.4b | 15.5 ± 3.9 | 15.4 ± 3.1 | ||

| Asian | 59.3 ± 17.3 | 47.4 ± 8.4 | 2.1 ± 1.3b | 2.2 ± 1.1b | ||

| Foreign born, % | 67.4 ± 19.0 | 65.1 ± 8.2 | .91 | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 10.9 ± 3.0 | .02 |

| US citizen, % | 91.4 ± 6.7 | 68.2 ± 8.4 | .02 | 100 | 96.1 ± 1.8 | .02 |

| Non-English language, % | 54.0 ± 16.3 | 36.6 ± 6.4 | .30 | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 8.9 ± 2.8 | .05 |

| Poverty index <1, % | 20.9 ± 9.4b | 22.2 ± 8.2b | .92 | 28.9 ± 5.3 | 46.6 ± 7.7 | .07 |

| Married, % | 84.5 ± 9.0 | 59.9 ± 8.4 | .04 | 25.1 ± 6.4 | 51.2 ± 8.4 | .07 |

| Education level, % | ||||||

| Some college or higher | 75.5 ± 8.9 | 48.8 ± 8.5 | .05 | 36.1 ± 8.2 | 34.5 ± 5.0 | .50 |

| Has insurance, % | 82.7 ± 10.6 | 70.7 ± 5.9 | .32 | 73.8 ± 7.4 | 72.6 ± 7.4 | .64 |

| Access to care, % | 89.0 ± 6.4 | 81.6 ± 6.2 | .39 | 79.1 ± 6.1 | 84.5 ± 4.4 | .49 |

| History of IDU, % | — | — | 53.0 ± 6.8 | 32.9 ± 6.5 | .03 | |

| MSM, % | 12.7 ± 11.1b | 5.2 ± 5.0b | .51 | 16.9 ± 7.9b | 1.5 ± 1.5b | .009 |

| Ever pregnant, % | 80.1 ± 16.9 | 83.3 ± 8.3 | .88 | 87.7 ± 4.3 | 100 | .04 |

| Blood transfusion, % | 9.0 ± 3.8b | 26.6 ± 20.2b | .21 | 24.7 ± 5.1 | 12.9 ± 3.0 | .06 |

| Abnormal ALT, %c | 82.6 ± 7.9 | 57.9 ± 9.5 | .08 | 57.1 ± 4.8 | 59.5 ± 5.2 | .36 |

| Mean platelet count, ×109/L | 178.9 ± 8.0 | 217.4 ± 9.1 | < .001 | 210.7 ± 9.8 | 235.7 ± 11.6 | .08 |

| APRI >1.5d, % | — | — | 9.8 ± 4.1b | 8.0 ± 2.2 | .67 | |

| FIB-4 >3.25d, % | 15.3 ± 5.4b | 5.6 ± 2.1 | .08 |

NOTE. All results given with mean or % ± standard error.

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index; FIB-4, Fibrosis-4 Score; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IDU, injection drug use; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Other race not reported because of small sample size.

Estimate has a relative standard error over 30% and may not be statistically reliable per National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey analytic guidelines.

Defined as ≥35 U/L for males, ≥25 U/L for females.

Omitted in HBV analysis because of small sample size

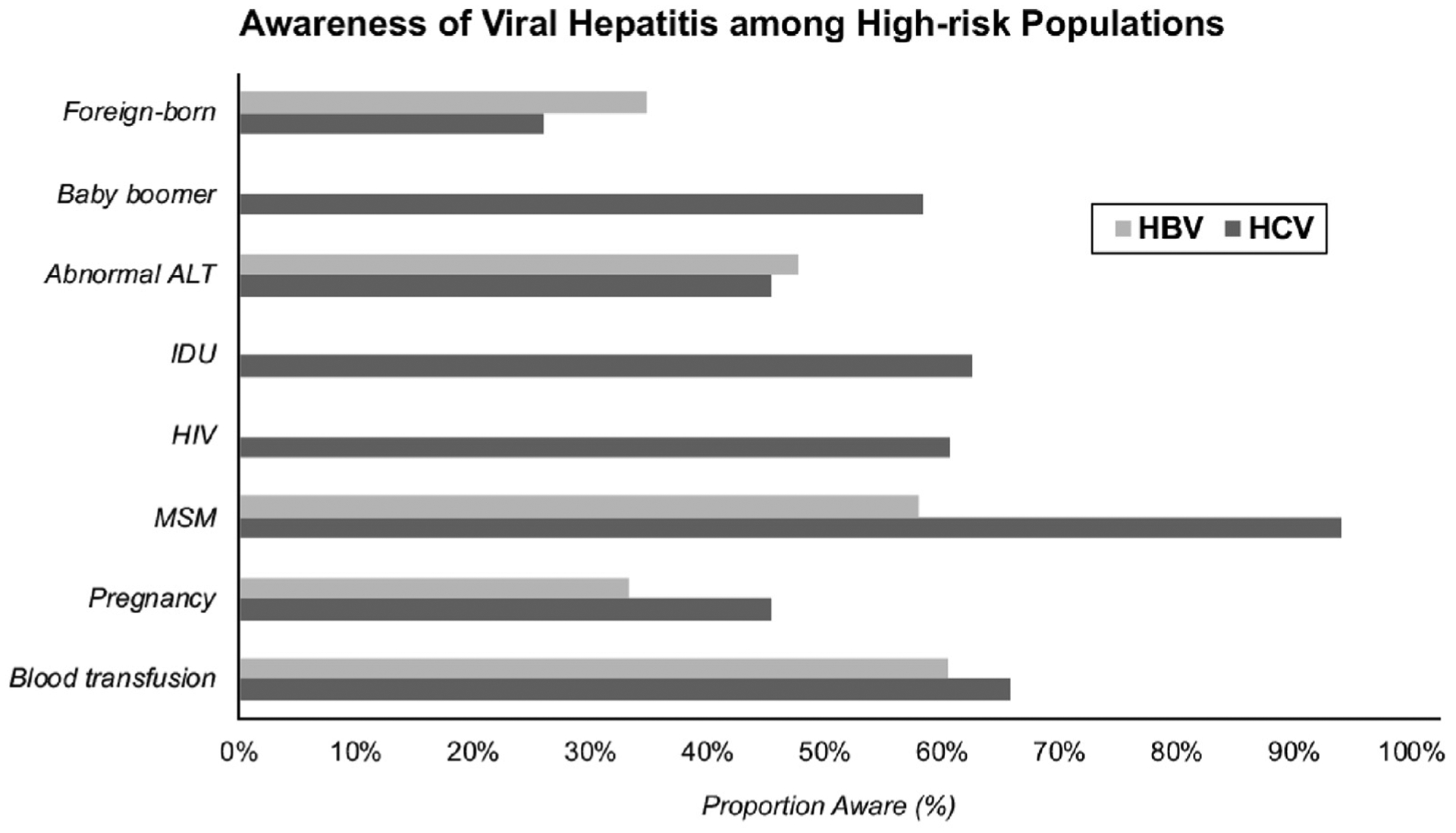

There were differences in the proportion who were aware of viral hepatitis status within demographic and clinical categories (awareness by high-risk populations highlighted in Figure 2; full results in Supplementary Table 3). Specifically, 58% of baby boomers reported HCV awareness, compared with only 36% of non–baby boomers. Hispanics were least likely to be aware of either infection (0% aware of HBV and 29% aware of HCV), and non-Hispanic whites most likely (45% aware of HBV and 56% aware of HCV). Only 14% of non-Hispanic blacks were HBV aware, compared with 46% HCV aware. Thirty-nine percent of Asians with HBV reported awareness. Higher proportions of awareness (>50%) were reported among certain high-risk populations for HCV infection including baby boomers, IDU, human immunodeficiency virus–positive, MSM, and history of blood transfusion. For HBV infection, awareness was more than 50% in those reporting MSM and history of blood transfusion only (no aware subjects with IDU or human immunodeficiency virus). There was low awareness among foreign-born individuals, with 35% reporting awareness of HBV and 26% reporting awareness of HCV. Notably, less than half of HBV-infected (48%) and HCV-infected (45%) persons with abnormal ALT levels (≥35 U/L males, ≥25 U/L females) were aware of their disease. Among HCV-infected, 73% with Fibrosis-4 Score (FIB-4) >3.25 reported awareness; only 3 HBV patients had FIB-4 >3.25 and none were aware. Of women with a history of pregnancy 33% and 45% reported being aware of HBV and HCV infections, respectively.

Figure 2.

Awareness of HBV and HCV infection among high-risk populations. Estimates of HBV awareness among IDU not reported because of low number of events (n = 3; 0% aware). There were no HBV-infected with HIV co-infection. Abnormal ALT defined as ≥25 U/L in women and ≥35 U/L in men. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Factors Impacting Awareness of Hepatitis B Virus and Hepatitis C Virus Infection

On univariate analysis, factors associated with greater odds of HBV awareness included US citizenship, being married, some college or higher education, and higher ALT (P < .1) (Table 2). Higher body mass index was associated with lower odds of awareness. For HCV infection, age categories 40–59 and older than 60 (compared with <20), baby boomers, MSM, history of blood transfusion, history of IDU, and a FIB-4 >3.25 were associated with HCV awareness (P < .1). Hispanic race/ethnicity, foreign-born, non-English language, lower poverty index, and being married were associated with being less aware of HCV infection (P < .1). Having an abnormal ALT was not associated with HCV awareness, but there was a trend toward increased HBV awareness (P = .06). A lower platelet count was associated with higher awareness for both HBV and HCV.

Table 2.

Characteristics Independently Associated With Self-Reported HBV or HCV Awareness

| Univariate | Multivariable | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds ratio |

Lower 95% |

Upper 95% |

P value |

Odds ratio |

Lower 95% |

Upper 95% |

P value |

| HBV | ||||||||

| US citizen (ref: noncitizen) | 4.95 | 0.96 | 25.4 | .06 | 3.07 | 1.03 | 9.23 | .05 |

| Married (ref: not married) | 3.64 | 0.87 | 15.3 | .08 | — | — | — | — |

| Education level (ref: ≤HS graduate) | ||||||||

| Some college or higher | 3.24 | 1.04 | 10.10 | .04 | 6.43 | 1.49 | 27.63 | .02 |

| BMI (continuous) | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.97 | .01 | — | — | — | — |

| ALT (continuous) | 1.02 | 1.00 | 1.04 | .07 | — | — | — | — |

| Abnormal ALT (ref: normal ALT) | 4.00 | 0.96 | 16.70 | .06 | 2.93 | 1.03 | 8.33 | .04 |

| Platelet count (per 1 × 109 unit increase) | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.996 | .007 | — | — | — | — |

| HCV | ||||||||

| Baby boomer (ref: not) | 2.47 | 0.88 | 6.96 | .09 | — | — | — | — |

| Hispanic race (ref: non-Hispanic) | 0.37 | 0.20 | 0.67 | .002 | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.66 | .01 |

| Foreign born (ref: US-born) | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.75 | .009 | — | — | — | — |

| Non-English (ref: English) | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.88 | .03 | — | — | — | — |

| Poverty index <1 (ref: >1) | 0.46 | 0.19 | 1.08 | .07 | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.65 | .01 |

| Married (ref: not) | 0.44 | 0.18 | 1.10 | .08 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.69 | .01 |

| MSM (ref: not)a | 13.4 | 1.21 | 148.5 | .04 | — | — | — | — |

| Blood transfusion (ref: never) | 2.22 | 0.95 | 5.19 | .06 | — | — | — | — |

| Injection drug use (ref: never) | 2.31 | 1.10 | 4.84 | .03 | 3.64 | 1.64 | 8.08 | .003 |

| Platelet count (per 1 × 109 unit increase) | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | .05 | — | — | — | — |

| FIB-4 >3.25 (ref <3.25) | 3.14 | 1.06 | 9.33 | .04 | — | — | — | — |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; FIB-4, Fibrosis-4 Score; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HS, high school; MSM, men who have sex with men; ref, reference.

Excluded from multivariable model because of small number.

In multivariable analysis, factors that remained independently associated with awareness in adults with HBV infection were US citizenship (odds ratio [OR], 3.1; 95% CI, 1.0–9.2), higher education (OR, 6.4; 95% CI, 1.5–27.6), and abnormal ALT (OR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.0–8.3). In HCV-infected adults, history of IDU was strongly associated with being aware (OR, 3.6; 95% CI, 1.6–8.1); and being of Hispanic race/ethnicity (OR, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.7), below the poverty line (OR, 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.7), and married (OR, 0.2; 95% CI, 0.1–0.7) were associated with lacking awareness.

Discussion

We demonstrate with recent cross-sectional population-based survey data that a significant proportion of US adults nationwide with chronic viral hepatitis remain unaware of their infection status. The proportion aware of their HCV infection (49%) was higher than HBV infection (34%), possibly the result of highly publicized efforts to combat HCV since the availability of all oral direct-acting antivirals.10 Of those aware, one-third with HBV and less than half with HCV reported receiving treatment, highlighting an additional gap in the care cascade. Lack of identification of treatment-eligible patients with HBV and all patients with HCV not only represent missed opportunities for treatment but also for secondary benefits, such as decreasing transmission and prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma.11,12 Potential target populations identified by our results for implementation of screening interventions are primarily those outside of traditional at-risk demographics, such as blacks for HBV and Hispanics and non–baby boomers for HCV. Areas for improvement for both viruses include increased screening among pregnant women, those with abnormal liver tests, and foreign-born.

Our reported national HBV prevalence of 0.7% is higher than the previously published NHANES prevalence rate of 0.3%, which had been constant over the 1988–2012 time period studied.13 Explanations for this may be oversampling of Asians starting in the 2011–2012 cycle, although accounted for in weighting, and exclusion of children in this study. The higher prevalence of HBV in foreign-born individuals in our study (2.3% compared with 1.1%13) also suggests increased immigration from endemic areas in recent years. Our reported HCV prevalence (based on anti-HCV positivity) of 1.8% is consistent with reports that similarly defined HCV infection,14 acknowledging this is an overestimate of chronic infection by including those who spontaneously cleared. Fifty-two percent of those anti-HCV positive between 2013 and 2016 were viremic, compared with 67% between 2001 and 2010.14 Our estimated HCV RNA prevalence of 0.9% is on par with a recent NHANES report over the same time period of 0.84% HCV RNA prevalence.15 This represents 2.0 million viremic individuals, lower than the 2.7 million estimated from NHANES data between 2003 and 20102 and 3.2 million between 1999 and 2002,16 reflecting the expected downward trend with increasing uptake of direct-acting antiviral therapy starting from 2011 and high rates of HCV cure. However, the overall proportion of infected (either past or current infection) adults who are aware of their HCV diagnosis has remained constant, 49.7% between 2001 and 20089 compared with 49% in this study, suggesting more concerted public health efforts are still needed to identify those infected and initiate the HCV care cascade.

Certain subpopulations with well-established and familiar risk factors for viral hepatitis had higher rates of awareness. Among HCV-infected, we found 3.6-fold higher odds of awareness among persons who inject drugs, suggesting that substantial efforts to promote testing and awareness in this high-risk population have been effective and may be applicable to other groups. Similarly, MSM (of whom 60% also reported IDU) had the highest rates of HCV awareness and higher rates of HBV awareness than other risk groups. One hypothesis for greater awareness is that these groups may have more frequent contact with or better access to health care. Overall, however, a high proportion (70%–80%) reported insurance and access to “a routine place for health care” and access was ultimately not associated with awareness, which more likely reflects sampling exclusion of marginalized groups in NHANES.

Our findings identify remaining gaps in awareness, and high-yield opportunities to enhance viral hepatitis screening. First, elevated ALT levels (>19–25 U/L for women and 29–33 U/L for men by guidelines) should prompt evaluation for viral hepatitis with testing for HBsAg and antibody to HCV.17 Reference ranges for upper limit of ALT range widely and are unstandardized across laboratories, and guideline cutoffs based on published histologic studies should be considered gold standard.18,19 How well clinicians adhere to viral hepatitis screening in practice on the basis of guideline cutoffs is unknown, although our study suggests there is room for improvement. Increasing provider education, particularly among primary care providers who are on the frontlines of viral hepatitis diagnosis and less likely to encounter liver-related society guidelines, on clinically relevant upper limits of ALT may be an important means of enhancing case identification. Second, deficient awareness of both HBV and HCV diagnoses was also identified among women who have been pregnant. Although high rates of prenatal HBV screening and low rates of maternal-to-child transmission are reported in the United States,20,21 our finding suggests screening does not equate awareness among these women and represents a missed opportunity for engagement in the viral hepatitis care cascade within a health care setting.

Lastly, expansion of screening campaigns to additional groups identified by this study as having low awareness is needed. In populations with high burden of HBV infection, such as Asian immigrants, awareness can be as high as 75%.22 In comparison, we found only 12% of noncitizen immigrant communities were HBV aware, with citizens 3-fold more likely to be aware, suggesting that recent immigrants are more vulnerable to undetected infection. Racial disparities in HCV awareness were found, in particular low awareness among Hispanics and foreign-born. A prior assessment of a community-based sample of US Hispanics/Latinos with HCV demonstrated a low 32% with awareness, dropping to 8% among those who were uninsured.23 Targeting these less often considered populations with evidence-based interventions, such as outreach events and patient navigation programs created through partnerships with existing community-based organizations, could be incorporated into ongoing elimination efforts.24

There are several limitations to this study. NHANES sampling does not capture institutionalized populations, homeless, and other groups with higher risk of viral hepatitis. Furthermore, the cutoff for “adult” in NHANES of 20 years or older does not account for rising viral hepatitis infections among young opiate users. This likely leads to underestimation of the proportion of the population unaware and untreated. For HBV-infected, HBV DNA testing is not available and phase of infection and treatment eligibility cannot be determined. Based on existing literature, the proportion of patients with HBV that meet guideline-based treatment criteria varies widely, ranging from 25% to 47% depending on the underlying population.25,26 Therefore, the 28% that reported treatment among those aware in this study is on the lower end of expected treatment eligibility and most likely represents undertreatment, a problem that has been suggested by other studies.27 Furthermore, it should be noted that 0 of 3 HBV-infected individuals with FIB-4 >3.25 were aware of their infection and patients with cirrhosis are those in whom treatment is most urgently indicated. Lastly, we had limited ability to obtain reliable estimates in some patient subgroups with HBV (ie, advanced fibrosis, Hispanic race).

In summary, this population-based study provides a current snapshot on progress with viral hepatitis elimination in the United States. We highlight the continued inadequate state of viral hepatitis awareness (<50%) among all individuals in the United States and especially among high-risk subpopulations (abnormal liver tests, foreign-born, and parous women). Despite growing public visibility of viral hepatitis over the past decade with increase in number treated, progress in the number being diagnosed has lagged behind. Considering the low overall awareness of both HBV and HCV diagnoses, concurrent increased funding for high-quality implementation research and scale-up of screening and linkage to care campaigns across the United States to augment rises in treatment access for viral hepatitis is warranted.

Supplementary Material

What You Need to Know.

Background

Elimination of viral hepatitis is a goal set forth by the World Health Organization. To achieve this goal, the first step is to identify infected individuals. Using a population-based cohort of adults surveyed and tested from 2013 through 2016, we examined rates of awareness of hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and treatment of patients who are aware of their infection.

Findings

Fewer than half of adults with HBV or HCV infection are aware of their infection. Among aware patients, 28% of HBV-infected and 59% of HCV-infected patients had been treated.

Implications for patient care

Opportunities to increase awareness include provider education on cut-off values for abnormal level of alanine aminotransferase that should prompt screening, and expansion of existing screening interventions to under-recognized at-risk groups.

Funding

Kali Zhou is supported by T32 5T32DK060414-14 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- CI

confidence interval

- FIB-4

Fibrosis-4 score

- anti-HBc

hepatitis B core antibody

- HBsAg

hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- IDU

injection drug use

- MSM

men who have sex with men

- NCHS

National Center for Health Statistics

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- OR

odds ratio

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology at www.cghjournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.047.

Conflicts of interest

This author discloses the following: Norah A. Terrault reports grant support from Gilead Sciences and BMS. The other author discloses no conflicts.

References

- 1.Kowdley KV, Wang CC, Welch S, et al. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B among foreign-born persons living in the United States by country of origin. Hepatology 2012;56:422–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denniston MM, Jiles RB, Drobeniuc J, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:293–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galbraith JW, Donnelly JP, Franco RA, et al. National estimates of healthcare utilization by individuals with hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:755–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yehia BR, Schranz AJ, Umscheid CA, et al. The treatment cascade for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e101554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology 2018;67:1560–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panel A-IHG. Hepatitis C guidance 2018 update: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 2018;67:1477–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen TT, Taylor V, Chen MS Jr, et al. Hepatitis B awareness, knowledge, and screening among Asian Americans. J Cancer Educ 2007;22:266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korthuis PT, Feaster DJ, Gomez ZL, et al. Injection behaviors among injection drug users in treatment: the role of hepatitis C awareness. Addict Behav 2012;37:552–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denniston MM, Klevens RM, McQuillan GM, et al. Awareness of infection, knowledge of hepatitis C, and medical follow-up among individuals testing positive for hepatitis C: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2008. Hepatology 2012;55:1652–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jorgensen C, Carnes CA, Downs A. “Know more hepatitis:” CDC’s national education campaign to increase hepatitis C testing among people born between 1945 and 1965. Public Health Rep 2016;131(Suppl 2):29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in HCV patients treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Gastroenterology 2017;153:996–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sung JJ, Tsoi KK, Wong VW, et al. Meta-analysis: treatment of hepatitis B infection reduces risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;28:1067–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts H, Kruszon-Moran D, Ly KN, et al. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in U.S. households: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 1988–2012. Hepatology 2016;63:388–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ditah I, Ditah F, Devaki P, et al. The changing epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001 through 2010. J Hepatol 2014;60:691–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenberg ES, Rosenthal EM, Hall EW, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in US states and the District of Columbia, 2013 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1: e186371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwo PY, Cohen SM, Lim JK. ACG clinical guideline: evaluation of abnormal liver chemistries. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112:18–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dutta A, Saha C, Johnson CS, et al. Variability in the upper limit of normal for serum alanine aminotransferase levels: a statewide study. Hepatology 2009;50:1957–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JK, Shim JH, Lee HC, et al. Estimation of the healthy upper limits for serum alanine aminotransferase in Asian populations with normal liver histology. Hepatology 2010; 51:1577–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris AM, Isenhour C, Schillie S, et al. Hepatitis B virus testing and care among pregnant women using commercial claims data, United States, 2011–2014. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2018; 2018:4107329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko SC, Fan L, Smith EA, et al. Estimated annual perinatal hepatitis B virus infections in the United States, 2000–2009. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2016;5:114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyun S, Lee S, Ventura WR, et al. Knowledge, awareness, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection among Korean American parents. J Immigr Minor Health 2018;20:943–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuniholm MH, Jung M, Del Amo J, et al. Awareness of hepatitis C virus seropositivity and chronic infection in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). J Immigr Minor Health 2016;18:1257–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris AM, Link-Gelles R, Kim K, et al. Community-based services to improve testing and linkage to care among non-U.S.-born persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection—three U. S. programs, October 2014-September 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:541–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vu VD, Do A, Nguyen NH, et al. Long-term follow-up and sub-optimal treatment rates of treatment-eligible chronic hepatitis B patients in diverse practice settings: a gap in linkage to care. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2015;2:e000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Bisceglie AM, Lombardero M, Teckman J, et al. Determination of hepatitis B phenotype using biochemical and serological markers. J Viral Hepat 2017;24:320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen C, Holmberg SD, McMahon BJ, et al. Is chronic hepatitis B being undertreated in the United States? J Viral Hepat 2011; 18:377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.