Abstract

Background:

Homelessness and unstable housing (HUH) negatively impact care outcomes for people living with HIV (PLWH). To inform design of a clinic program for PLWH experiencing HUH, we quantified patient preferences and trade-offs across multiple HIV-service domains using a discrete choice experiment (DCE).

Methods:

We sequentially sampled PLWH experiencing HUH presenting at an urban HIV clinic with ≥1 missed primary care visit and viremia in the last year to conduct a DCE. Participants chose between two hypothetical clinics varying across five service attributes: care team “get to know me as a person” versus not; receiving $10, $15 or $20 gift cards for clinic visits; drop-in versus scheduled visits; direct phone communication to care team versus front-desk staff; staying 2 versus 20 blocks from the clinic. We estimated attribute relative utility (i.e., preference) using mixed-effects logistic regression and calculated the monetary trade-off of preferred options.

Results:

Among 65 individuals interviewed, 61% were >40 years-old; 45% white; 77% male; 25% heterosexual; 56% lived outdoors/emergency housing, and 44% in temporary housing. Strongest preferences were for patient-centered care team (β = 3.80; 95%CI 2.57-5.02) and drop-in clinic appointments (β = 1.33; 95%CI 0.85-1.80), with a willingness to trade $32.79 (95%CI 14.75-50.81) and $11.45 (95%CI 2.95-19.95) in gift cards/visit, respectively.

Conclusion:

In this DCE, PLWH experiencing HUH were willing to trade significant financial gain to have a personal relationship with and drop-in access to their care team rather than more resource-intensive services. These findings informed Ward 86’s “POP-UP” program for PLWH-HUH and can inform “Ending the HIV Epidemic” efforts.

Keywords: HIV, Homelessness and Unstable Housing, Retention in Care, Discrete Choice Experiment

Introduction

Homelessness and unstable housing (HUH) are major barriers to realizing the full benefits of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for people living with HIV (PLWH).1–9 In San Francisco, only 33% of PLWH experiencing HUH were virally suppressed in 2018 compared to 75% in those who were housed.10 Moreover, in the context of a worsening homelessness epidemic, with fears that the COVID-19 pandemic will exacerbate this problem, unstable housing constitutes a major obstacle to achieving the goals of the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative.11–16 Multiple strategies exist to enhance retention in care for PLWH experiencing HUH,17–22 such as providing low-barrier care, using financial incentives to promote behavior change, and strengthening patient-centered care.18,20,23 Since multiple individual-level and structural barriers to care exist for PLWH experiencing HUH, multi-component programs are likely to be required to improve care outcomes for this highly vulnerable population.12,24–30 However, consensus on program design and component prioritization is lacking and program implementation may need to adapt to accommodate clinic- and patient-level characteristics.

Robust methods to elicit patient preferences for program components can guide program design. Discrete choice experiments (DCE), research tools commonly used in marketing, can be used to quantify patient preferences and evaluate trade-offs between program components.31,32 In this paper, we employed a DCE among PLWH experiencing HUH to understand patient preferences for, relative utility of, and trade-offs between program components to help us design a clinic-based care model to improve retention in care and treatment outcomes among PLWH experiencing HUH.

Methods

Study setting, population and sampling

This study was conducted between March and July, 2019 at the San Francisco General Hospital’s HIV primary care clinic (“Ward 86”), which serves a vulnerable and diverse patient population with approximately one-third experiencing HUH.7 Clinic providers referred patients to this study. Eligible participants 1) reported HUH defined as staying outdoors (e.g. on the streets, in parks or in a vehicle), in emergency housing (e.g. shelter, navigation center or temporary room in an single residency occupancy (SRO) hotel), “couch surfing” (i.e. living temporarily with friends or family or in a place in exchange for sex or drugs), an institution (e.g. drug or alcohol treatment program, transitional housing), non-residential space (e.g. commercial space, office space or storage unit); 2) had at least one viral load measurement > 200 copies/mL in the past 12 months; 3) ≥1 missed primary care visit in the 12 months; and 4) were able to conduct the interviews in English. Patients received a $20 gift card to a local grocery store for their participation. This study was approved by University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Institutional Review Board.

Selection of attributes for the choice experiment

We performed a literature review to identify interventions that improve retention in care among PLWH experiencing HUH33: 1) providing low-barrier access primary care without the need for clinic appointments;20 2) utilizing financial incentives for care engagement;18 3) allowing for direct communication with clinical care team;34–36 and 4) strengthening models of patient-centered care.23 We then conducted 10 semi-structured interviews to confirm the acceptability of program components identified in the literature review and elicit additional attributes. The resulting attribute choices derived from this iterative process were as follows (Figure 2): 1) defining patient-centered care as “providers and staff get to know me as a person” versus “providers and staff do not get to know me as a person,”37 2) having “scheduled visits” via appointment or “unscheduled drop-in visits (Monday - Friday afternoon)”;30 3) receiving gift cards for attending clinic visits in the amount of $10, $15, or $20;18 4) communicating with clinic team through “phone calls directly to a care provider at the clinic during clinic hours” versus “through phone calls to the front desk during clinic hours”;38 5) the distance from where the patient stays to the clinic equaling “2 city blocks” versus “20 city blocks”.29 Final choice tasks were piloted among 7 patients to confirm general comprehension, refine definitions, and verify readability.

DCE design

We used Lighthouse Studio Version 9.6.1 (Sawtooth Software, Provo, Utah, USA) to construct the survey. The DCE included five attributes as listed above, four of which used two-level choice-tasks by two-levels and one of which used a three-level choice-task, yielding a total of 48 (e.g., 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 3) potential combinations. Because it is not feasible to evaluate the total number of comparisons ([47 × 48]/2 or 1,128), we constructed a fractional factorial design to limit the number of choice pairings presented to respondents.39 We used an orthogonal main effect plan (OMEP)39 to construct choice tasks that prioritized understanding trade-offs and preferences of having the first attribute (“providers and staff who get to know patients as a person”) compared to other attributes.

We considered balance (i.e. ensuring that each attribute level was presented to the respondents the same number of times, with no option provided more than the other options), orthogonality (i.e. ensuring that each pair of attribute levels appeared with the same frequency across all pairs of attributes),40,41 and efficiency when constructing the DCE design. In this way, the correlation among attributes was zero. We tested efficiency using SAS™ software. One hundred percent efficiency is achieved when D-Error (the average variance of all attributes) is equal to 1/number of choice tasks. The final design was balanced, orthogonal, and fully efficient with a D-efficiency of 100% relative to the hypothetical optimal design.

Participants completed 12 choice-tasks, which maximized the design’s efficiency and minimized cognitive burden.39 The survey displayed pictorial examples alongside attributes in order to improve understanding and compare the two options (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which demonstrates the attributes and pictorial examples presented in the DCE). Each choice-task presented participants with two models of clinic programs that differed from each other across one or more characteristics. The participant was then asked for their clinic preference: “Do you prefer going to Clinic A, Clinic B, or would you rather not go to either one?”

Sample size

We calculated that 63 patients would be sufficient using a rule suggested by Johnson and Orme that a sample size required for the main effects depends on the number of choice tasks (t), the number of alternatives per task, not including the none alternative (a), and the largest number of levels for any one attribute (c) according to the following equation: N > 500c / (t × a).42

Data collection

We used tablets to collect sociodemographic information (using REDCap™) and conduct the DCE survey. The first author screened for eligibility and obtained consent, guided the participants through an example question and remained available to answer clarifying questions during the survey.

Analysis

Using STATA™, we tabulated patient demographics, drug/alcohol use, and clinical characteristics. We used a mixed logit regression model to estimate the relative utility (i.e., preference) of each attribute level in the cohort which, assuming independence of attributes, presents the relative mean preference weights (β-coefficients), standard deviations (SDs) of effects across the sample, and captures the heterogeneity across participants.39,40 The gift card attribute was treated as a continuous variable and the remaining attributes were treated as dichotomous variables. No sub-group analyses were performed given the limited number of participants. We conducted a willingness to pay analysis to calculate ratios of utilities to determine the amount in dollars that would be required to have an equivalent preference for that attribute.39

Results

Demographics

Two hundred forty-two patients were referred for participation from social workers, primary care physicians, and urgent care providers during clinical visits, of whom 192 did not meet enrollment criteria (housing status, lack of engagement in care or virologic suppression), yielding 65 eligible patients, all of whom completed the DCE. Of the 65 respondents (Table 1), 40 (61%) were older than 50 years of age; 50 (77%) were male; 36 (55%) were non-white; 16 (25%) identified as heterosexual; 33 (51%) received any secondary education (e.g. college or greater); 57 (88%) reported some form of substance use; and 25 (38%) had achieved virologic suppression at least once in the 12-months prior to the survey. In terms of housing status, 36 (56%) reported staying outdoors or in emergency housing and 29 (44%) reported living in temporary housing.

Table 1:

Patient baseline demographic and clinical information, (N=65).

| Patient Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) < 30 31-40 41–50 >50 |

9 (14) 16 (25) 18 (28) 22 (33) |

| Self-Reported Gender Male Female Male-to-Female Transgendered/Transgendered Woman Other gender not listed |

50 (77) 9 (13) 3 (5) 3 (5) |

| Highest level of schooling completed Some college or more |

33 (51) |

| Race White Black/African American Latino Other |

29 (45) 20 (31) 12 (18) 4 (6) |

| Sexual Identity Lesbian, gay or homosexual Straight or heterosexual Bisexual Don’ know Other |

29 (45) 16 (25) 10 (15) 5 (8) 5 (8) |

| Substance Use Opiates Stimulants Other |

7 (11) 40 (62) 18 (28) |

| Viral load < 200 copies/mL in 12 months prior to survey | 25 (38) |

| Psychiatric Diagnosis Depression or Anxiety Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder None |

39 (60) 24 (37) 15 (23) |

|

Current living arrangement (n, %) Outdoors Emergency housing “Couch surfing” or “housing sitting” An institution A non-residential space that you rent, own or occupy |

14 (22) 22 (34) 16 (25) 10 (15) 3 (4) |

Outdoors = on the streets, in parks or in a vehicle; Emergency housing = (shelter, navigation center or temporary room in an SRO/hotel); couch surfing (e.g. temporarily with friends or family or in a place in exchange for sex or drugs); An institution = drug or alcohol treatment program, transitional housing; Non-residential space = commercial space, office space or storage unit

DCE Results

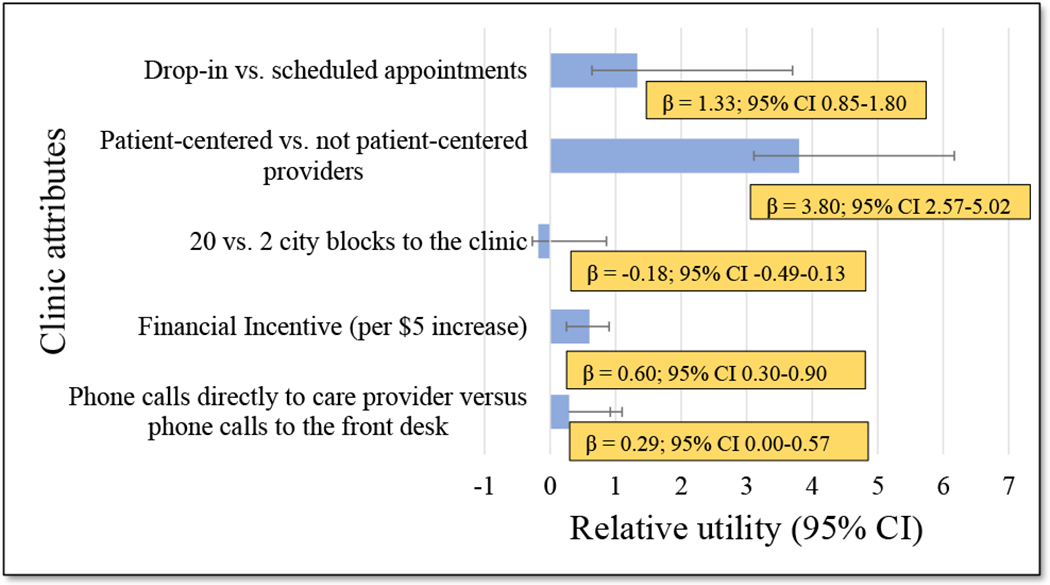

The strongest preferences (Figure 1) were for patient-centered providers (β = 3.80; 95% CI 2.57-5.02) and drop-in (rather than scheduled) clinic visits (β = 1.33; 95%CI 0.85-1.80) (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows mixed logit regression model results). A weaker preference was expressed for receiving gift cards for coming to clinic visits (β = 0.60 per $5 incentive; 95% CI 0.30-0.90). No statistically significant preference was observed for having the ability to make direct phone calls to the care provider versus phone calls to the front desk (β = 0.29; 95% CI -0.001 – 0.57) and staying 20 versus 2 city blocks away from the clinic (β = -0.18; 95% CI -0.49-0.13).

Figure 1:

Relative utilities (i.e. preferences) of clinic attributes (results from the mixed logit regression model)

In the willingness to pay analysis, participants were willing to trade a hypothetical $32.79 (95% CI 14.75 - 50.81) in gift cards per visit to have a care team that gets to know them as a person, $11.45 (95% CI 2.95 - 19.96) for having drop-in versus scheduled appointments and $2.46 (95% CI 0.46 - 4.47; p = 0.016) for having direct communication with care providers versus front-desk staff.

Discussion

We performed the first DCE reported in the literature to elicit preferences for a clinical care program for PLWH experiencing HUH. We observed that participants most strongly preferred patient-centered providers and hypothetically were willing to trade almost $33 for this preference. Other statistically significant findings included a strong patient preference for drop-in, rather than scheduled, appointments. Surprisingly, there was no preference for shorter travel distance to clinic, suggesting that flexible clinic design superseded clinic location in terms of attributes that would encourage retention in care.

Numerous qualitative studies support the importance of positive patient-provider relationships,28,43,44 which has been characterized as having a provider “who cares about you”.45 In a choice experiment conducted in Zambia among patients with HIV who were lost to follow-up, patients were willing to travel longer distances and attend a clinic with shorter operating hours in order to interact with healthcare providers who were “nice”.46 Another choice experiment among patients with HIV/HCV co-infection in a safety net clinic indicated that receiving treatment from a patient’s current regular provider was the single most important attribute in making treatment decisions.32 Positive experiences with HIV providers and clinic staff has been associated with improved retention in HIV care47 and having a patient-centered provider has been associated with a 32% higher odds of adhering to ART.37 Our study adds information to the current research by quantifying the degree to which PLWH experiencing HUH may be willing to forego other interventions in order to receive care from a provider with whom they have a positive relationship.

A strong preference for drop-in, rather than scheduled, appointments was another statistically significant finding from our study, which has been supported by qualitative studies.48–50 Indeed, walk-in access and same-day appointments have been adopted by other clinics that serve PLWH experiencing homelessness and who are poorly retained in care.20,51

Limitations to this study should be considered. First, DCEs collect data based on stated preferences and not on actual behavior or care outcomes. Second, we assumed model linearity in the willingness to pay analysis. Third, results are limited to participants who are somewhat engaged with clinic staff, rather than completely out of care, and excluded those who could not complete the survey in English. Fourth, our evaluation emphasized only one dimension of patient-centeredness but did not elicit preferences in other dimensions important to this construct.52–54

Conclusion

This is the first DCE to help design a novel clinical care program in an urban safety net HIV clinic. PLWH experiencing HUH strongly preferred having providers who know them as a person and having a model of care with drop-in, rather than scheduled, appointments. These preferences helped our HIV clinic (Ward 86) design a novel model of care for PLWH-HUH called the “POP-UP” program.55 Further research is needed to refine our understanding on how patients define “a provider that knows me” and the role of patient-centeredness in improving retention in care among PLWH experiencing HUH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr’s Hae Young Kim and David Glidden for assistance with biostatistical analysis.

A. Asa Clemenzi-Allen received support from an NIH T32AI060530-12

E. Geng received support from an NIH K24 AI134413

The “Ward 86” HIV program in the Division of HIV, ID and Global Medicine received an unrestricted investigator-initiated grant from the Gilead Foundation to support implementation and evaluation of the ‘POP-UP’ program, a clinical program for PLWH experiencing HUH (Grant # IN-US-985-5691). Gilead had no role in the interpretation or presentation of these results.

Direct CFAR Funding Support

This research was supported by an Ending the HIV Epidemic Supplemental grant from the National Institutes of Health to the UCSF-Gladstone Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI027763).

Indirect/Partial Funding Support

This publication/presentation/grant proposal was made possible with help from an Ending the HIV Epidemic supplement to the UCSF-Gladstone Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH-funded program (P30 AI027763).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

No Conflicts of Interest to report

References

- 1.Clemenzi-Allen A, Neuhaus J, Geng E, et al. Housing Instability Results in Increased Acute Care Utilization in an Urban HIV Clinic Cohort. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(5):ofz148. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham WE, Sohler NL, Tobias C, et al. Health services utilization for people with HIV infection: comparison of a population targeted for outreach with the U.S. population in care. Med Care. 2006;44(11):1038–1047. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000242942.17968.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aidala AA, Lee G, Abramson DM, Messeri P, Siegler A. Housing Need, Housing Assistance, and Connection to HIV Medical Care. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(S2):101–115. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9276-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spinelli M, Hessol N, Schwarcz S, et al. Homelessness at diagnosis is associated with death among people with HIV in a population-based study of a US city. Aids. 2019;33(11):1789–1794. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheer S, Hsu L, Schwarcz S, et al. Trends in the San Francisco Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic in the “Getting to Zero” Era. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(7):1027–1034. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrico AW, Hunt PW, Neilands TB, et al. Stimulant Use and Viral Suppression in the Era of Universal Antiretroviral Therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;80(1):89–93. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemenzi-Allen A, Geng E, Christopoulos K, et al. Degree of Housing Instability Shows Independent “Dose-Response” With Virologic Suppression Rates Among People Living With Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(3):58–60. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doshi RK, Milberg J, Jumento T, Matthews T, Dempsey A, Cheever LW. For Many Served By The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, Disparities In Viral Suppression Decreased, 2010–14. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1):116–123. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandsager P, Marier A, Cohen S, Fanning M, Hauck H, Cheever LW. Reducing HIV-Related Health Disparities in the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(S4):S246–S250. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colfax G, Enora W, Scheer S. HIV Annual Epidemiology Report. Published online September 2019. https://www.sfdph.org/dph/files/reports/RptsHIVAIDS/HIV-Epidemiology-Annual-Report-2018.pdf

- 11.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321(9):844–845. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Z Vital Signs: HIV Transmission Along the Continuum of Care — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6811e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz I, Jha AK. HIV in the United States: Getting to Zero Transmissions by 2030. JAMA. 2019;321(12):1153–1154. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petry L, Kwak Y, Connery P, Green S, Gallant J. Homeless Count & Survey Comprehensive Report, San Francisco. Published online July 18, 2019. http://hsh.sfgov.org/wp-content/uploads/FINAL-PIT-Report-2019-San-Francisco.pdf

- 15.Caplan V San Francisco 2019 Point-in-Time Homeless Count. :11.

- 16.United States. The annual homeless assessment report to Congress. Published online December 2017. https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2017-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

- 17.Cunningham WE, Weiss RE, Nakazono T, et al. Effectiveness of a Peer Navigation Intervention to Sustain Viral Suppression Among HIV-Positive Men and Transgender Women Released From Jail: The LINK LA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(4):542–553. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metsch LR, Feaster DJ, Gooden L, et al. Effect of Patient Navigation With or Without Financial Incentives on Viral Suppression Among Hospitalized Patients With HIV Infection and Substance Use: A Randomized Clinical Trial HHS Public Access. JAMA. 2016;316(2):156–170. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cabral HJ, Davis-Plourde K, Sarango M, Fox J, Palmisano J, Rajabiun S. Peer Support and the HIV Continuum of Care: Results from a Multi-Site Randomized Clinical Trial in Three Urban Clinics in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(8):2627–2639. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1999-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dombrowski JC, Ramchandani M, Dhanireddy S, Harrington RD, Moore A, Golden MR. The Max Clinic: Medical Care Designed to Engage the Hardest-to-Reach Persons Living with HIV in Seattle and King County, Washington. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32(4):149–156. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borne D, Tryon J, Rajabiun S, Fox J, de Groot A, Gunhouse-Vigil K. Mobile Multidisciplinary HIV Medical Care for Hard-to-Reach Individuals Experiencing Homelessness in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(S7):S528–S530. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajabiun S, Tryon J, Feaster M, et al. The Influence of Housing Status on the HIV Continuum of Care: Results From a Multisite Study of Patient Navigation Models to Build a Medical Home for People Living With HIV Experiencing Homelessness. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(Suppl 7):S539–S545. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kertesz SG, Holt CL, Steward JL, et al. Comparing Homeless Persons’ Care Experiences in Tailored Versus Nontailored Primary Care Programs. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(S2):S331–S339. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kay ES, Batey DS, Mugavero MJ. The HIV treatment cascade and care continuum: updates, goals, and recommendations for the future. AIDS Res Ther. 2016;13(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s12981-016-0120-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Operario D, Nemoto T. HIV in transgender communities: syndemic dynamics and a need for multicomponent interventions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2010;55 Suppl 2:S91–3. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbc9ec [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gwadz MV, Collins LM, Cleland CM, et al. Using the multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) to optimize an HIV care continuum intervention for vulnerable populations: a study protocol. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):383. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4279-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metsch LR, Pugh T, Colfax G. An HIV Behavioral Intervention Gets It Right—and Shows We Must Do Even Better. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(4):553–555. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holtzman CW, Shea JA, Glanz K, et al. Mapping patient-identified barriers and facilitators to retention in HIV care and antiretroviral therapy adherence to Andersen’s Behavioral Model. AIDS Care. 2015;27(7):817–828. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1009362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yehia BR, Stewart L, Momplaisir F, et al. Barriers and facilitators to patient retention in HIV care. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):246. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0990-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dombrowski JC, Simoni JM, Katz DA, Golden MR. Barriers to HIV Care and Treatment Among Participants in a Public Health HIV Care Relinkage Program. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zanolini A, Sikombe K, Sikazwe I, et al. Understanding preferences for HIV care and treatment in Zambia: Evidence from a discrete choice experiment among patients who have been lost to follow-up. PLOS Med. 2018;15(8):e1002636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shumway M, Luetkemeyer AF, Peters MG, Johnson MO, Napoles TM, Riley ED. Direct-acting antiviral treatment for HIV/HCV patients in safety net settings: patient and provider preferences. AIDS Care. Published online March 4, 2019:1–8. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1587353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clemenzi-Allen AA, Hickey M, Conte M, et al. Improving Care Outcomes for PLWH Experiencing Homelessness and Unstable Housing: a Synthetic Review of Clinic-Based Strategies. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2020;17(3):259–267. doi: 10.1007/s11904-020-00488-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dillingham R, Ingersoll K, Flickinger TE, et al. PositiveLinks: A Mobile Health Intervention for Retention in HIV Care and Clinical Outcomes with 12-Month Follow-Up. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32(6):241–250. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flickinger TE, DeBolt C, Waldman AL, et al. Social Support in a Virtual Community: Analysis of a Clinic-Affiliated Online Support Group for Persons Living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(11):3087–3099. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1587-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saberi P, Siedle-Khan R, Sheon N, Lightfoot M. The Use of Mobile Health Applications Among Youth and Young Adults Living with HIV: Focus Group Findings. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2016;30(6):254–260. doi: 10.1089/apc.2016.0044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beach MC, Keruly J, Moore RD. POPULATIONS AT RISK Is the Quality of the Patient-Provider Relationship Associated with Better Adherence and Health Outcomes for Patients with HIV? doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00399.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gardner LI, Giordano TP, Marks G, et al. Enhanced Personal Contact With HIV Patients Improves Retention in Primary Care: A Randomized Trial in 6 US HIV Clinics. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bridges JFP, Hauber AB, Marshall D, et al. Conjoint Analysis Applications in Health—a Checklist: A Report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health. 2011;14(4):403–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson FR, Lancsar E, Marshall D, et al. Constructing Experimental Designs for Discrete-Choice Experiments: Report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.08.2223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mangham LJ, Hanson K, McPake B. How to do (or not to do) … Designing a discrete choice experiment for application in a low-income country. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24(2):151–158. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Orme B Getting Started with Conjoint Analysis: Strategies for Product Design and Pricing Research; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yehia BR, Stewart L, Momplaisir F, et al. Barriers and facilitators to patient retention in HIV care. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0990-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson MO, Chesney MA, Goldstein RB, et al. Positive provider interactions, adherence self-efficacy, and adherence to antiretroviral medications among HIV-infected adults: A mediation model. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20(4):258–268. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wood TJ, Koester KA, Christopoulos KA, Sauceda JA, Neilands TB, Johnson MO. If someone cares about you, you are more apt to come around: improving HIV care engagement by strengthening the patient-provider relationship. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:919–927. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S157003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zanolini A, Sikombe K, Sikazwe I, et al. Understanding preferences for HIV care and treatment in Zambia: Evidence from a discrete choice experiment among patients who have been lost to follow-up. Published online 2018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dang BN, Westbrook RA, Hartman CM, Giordano TP. Retaining HIV Patients in Care: The Role of Initial Patient Care Experiences. AIDS Behav. 20. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1340-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith LR, Fisher JD, Cunningham CO, Amico KR. Understanding the Behavioral Determinants of Retention in HIV Care: A Qualitative Evaluation of a Situated Information, Motivation, Behavioral Skills Model of Care Initiation and Maintenance. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26(6):344–355. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maulsby C, Sacamano P, Jain KM, et al. Barriers and Facilitators to the Implementation of a National HIV Linkage, Re-Engagement, and Retention in Care Program. AIDS Educ Prev. 2017;29(5):443–456. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2017.29.5.443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lam Y, Westergaard R, Kirk G, et al. Provider-Level and Other Health Systems Factors Influencing Engagement in HIV Care: A Qualitative Study of a Vulnerable Population. Price MA, ed. PloS One. 2016;11(7):e0158759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kertesz SG, Pollio DE, Jones RN, et al. Development of the Primary Care Quality-Homeless (PCQ-H) Instrument. Med Care. 2014;52(8):734–742. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berwick DM. What ‘Patient-Centered’ Should Mean: Confessions Of An Extremist. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(Supplement 1):w555–w565. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, Dirmaier J. An Integrative Model of Patient-Centeredness – A Systematic Review and Concept Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beach MC, Keruly J, Moore RD. Is the quality of the patient-provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):661. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00399.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Imbert E, Hickey M, Clemenzi-Allen AA, et al. POP-UP Clinic: A multicomponent model of care for people living with HIV (PLHIV) who experience homelessness or unstable housing (HUH). Oral Abstract Presented at: AIDS 2020. (Virtual). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.