Abstract

Meningiomas with prominent inflammation are traditionally classified as “lymphoplasmacyte‐rich meningioma” (LPM). Both inflammatory and neoplastic meningeal proliferations have recently been linked to IgG4 disease, although a potential association with LPM has not been previously explored. Sixteen meningiomas with inflammatory cells outnumbering tumor cells were further characterized by CD3, CD20, CD68 and/or CD163, CD138, kappa, lambda, IgG and IgG4 immunostains. There were 11 female and 4 male patients, ranging from 22 to 78 (median 59) years of age. Tumors consisted of 10 World Health Organization (WHO) grade I, 5 grade II and 1 grade III LPMs. Immunohistochemically, the most numerous cell type was the macrophage in all cases followed by CD3‐positive T cells and fewer CD20‐positive B cells. Plasma cells ranged from moderate‐marked (N = 5) to rare (N = 7), or absent (N = 4). Maximal numbers of IgG4 plasma cells per high power field (HPF) ranged from 0 to 32, with only two cases having counts exceeding 10/HPF. The IgG4/IgG ratio was increased focally in only two cases (30% and 31%). Additionally, plasma cells represented only a minor component in most examples, whereas macrophages predominated, suggesting that “inflammation‐rich meningioma” may be a more accurate term. The inflammatory stimulus for most cases remains to be elucidated.

Keywords: IgG4, inflammation, lymphoplasmacyte rich, meningioma

Abbreviations

- CNS

central nervous system

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- IPT

inflammatory pseudotumor

- LPM

lymphoplasmacyte‐rich meningioma

Introduction

IgG4‐related disease is a recently recognized distinct entity that may be associated with universal features including tumefactive lesions, IgG4‐rich plasma cells in a dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate, storiform fibrosis and often an elevated serum IgG4 level 34. In 2001, Hamano et al reported that patients with autoimmune pancreatitis had elevated serum levels of IgG4 compared with pancreatitis due to other causes 13. This was followed by the revelation of increased numbers of IgG4‐positive plasma cells in the pancreas and surrounding tissues of the resected pancreatectomy specimens of autoimmune pancreatitis 17. Over the years, it has become evident that IgG4‐related sclerosing disease can involve many other organs individually or in various combinations, without a requirement for pancreatic involvement 24.

As the spectrum of this disease continues to evolve and be better defined, the literature on central nervous system (CNS) involvement by this autoimmune disorder, including diagnostic criteria, remains scant. Lindstrom et al studied 10 cases of unexplained lymphoplasmacytic meningeal inflammation (previously diagnosed as idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis) and evaluated these for IgG and IgG4 expression using immunohistochemistry (IHC) 24. Proposing a cutoff of greater than 10 IgG4‐positive plasma cells per high power field averaged over 5 consecutive/high power fields (HPFs) to be IgG4 related, 5 of their 10 cases qualified as IgG4 disease 24. They also noted that their IgG4‐positive cases often displayed other histological features commonly seen in this disorder, including dense fibrosis and phlebitis 24. They therefore concluded that a subset of dural‐based chronic inflammatory lesions previously considered idiopathic might, in fact, represent IgG4‐related meningeal disease. A review of the literature on CNS involvement by this disease also reveals isolated case reports of IgG4 disease presenting as hypophysitis 14, 33, pachymeningitis with or without dural mass 3, 18, 36, 40, spinal cord involvement 3, or an orbital mass 38.

Interestingly, increased numbers of IgG4‐positive plasma cells have also been noted in a spectrum of head and neck lesions designated as inflammatory pseudotumors (IPTs), suggesting that a subset of these may similarly fall under the family of IgG4‐sclerosing disease. Once the neoplastic counterpart of ALK‐associated inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor is excluded, CNS IPT (also called plasma cell granuloma/xanthogranuloma/histiocytoma) is the leading consideration. CNS IPT is a mass like, often dural‐based lesion characterized by a non‐clonal spindle cell proliferation of fibroblastic/myofibroblastic cells and a chronic inflammatory component comprised of lymphocytes, plasma cells and eosinophils in varying proportions 19. IgG4‐related IPTs are well known to occur in some head and neck sites including the salivary gland, lacrimal glands and pituitary gland 19. Other reported sites include nose/paranasal sinus 15, intracranial/dural sites 25 and parapharyngeal space 26. IgG4‐related IPT of the trigeminal nerve without involvement of other CNS sites has also been reported by Katsura et al 19. Most recently, increased numbers of IgG4‐positive plasma cells were observed in a subset of dural‐based marginal zone lymphomas, raising the possibility that IgG4 disease may even predispose to neoplastic transformation 37. Given that the spectrum of CNS lesions associated with IgG4 disease continues to evolve and expand, we sought to explore possible associations with another neoplastic disorder, meningioma, specifically those associated with marked chronic inflammation, commonly referred to as lymphoplasmacyte‐rich meningioma (LPM). Furthermore, because IgG4‐sclerosing disease has been known to respond well to corticosteroid therapy 24, 36, establishing a link between this entity and LPM could potentially have significant treatment implications.

Materials and Methods

Case selection

A subset of meningiomas with a prominent inflammatory component, including LPMs, was retrieved from the archives of the authors' surgical pathology and consultation files. A total of 16 cases were identified from 15 patients. Information regarding neuroimaging features, recurrence and medical history of cancer or inflammatory conditions (especially thyroiditis and pancreatitis) was obtained from the medical records at the institution from which the case originated.

Morphological evaluation

All cases were morphologically evaluated and graded by one of the authors (AP) utilizing the World Health Organization (WHO) grading scheme for meningiomas 30. In order to qualify as a LPM, inflammatory cells had to outnumber tumor cells in at least portions of the mass; additionally, the predominant pattern of inflammation, that is, intratumoral vs. peritumoral, was also recorded. Degree of sclerosis (subjectively stratified into mild, moderate or marked) and presence or absence of perivascular inflammation/vasculitis/perivenular phlebitis and vascular thrombosis were also documented. Presence or absence of psammoma bodies, lymphoid follicles, eosinophils and granulomas was also evaluated.

IHC staining

IHC was performed on formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded tissue sections using the streptavidin–biotin peroxidase method. Antibodies and dilutions used were epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) (DAKO; dilution 1:100), progesterone receptor (PR) (DAKO; dilution 1:100), Ki‐67 (MIB‐1 clone; DAKO; dilution 1:1000), CD20 (Leica; dilution ready to use/undiluted) CD3 (Leica; dilution ready to use/undiluted), CD68 (Leica; dilution ready to use/undiluted), CD163 (Leica; dilution 1:100), CD138 (Leica; dilution ready to use/undiluted), IgG (DAKO; dilution 1:600), IgG4 (Cell Marque; dilution‐undiluted), kappa (Cell Marque; dilution 1:5) and lambda (Cell Marque; dilution 1:2). Antigen retrieval was achieved using either heat‐induced epitope retrieval (DAKO Pascal pressure cooker) in 10 mM citrate buffer at pH 6.0 (EMA, Ki‐67, kappa, lambda and IgG) or automated on the Leica Bond System in ER1 at pH 6.0 (PR, CD20, CD138 and CD163), ER2 at pH 9.0 (CD3 and CD68), or proteinase K (DAKO) (IgG4). The blocking step included incubation with 3% H2O2. The detection chromagen was 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB).

IHC scoring

All immunohistochemical stains were evaluated by three pathologists (AP, AL, AH). EMA and PR were scored as positive or negative. The Ki‐67 labeling index (LI) was scored in a minimum of 500 cells as the maximal fraction of tumor cells showing nuclear positivity for this marker (“hot spots”), with results expressed as a percentage. Care was taken to exclude endothelial and inflammatory cells, although this was difficult in some cases. CD3, CD20, CD138, CD68 and CD163 positive infiltrates were scored subjectively as mild, moderate or marked based on cell densities (roughly defined as: mild = scattered immunoreactive cells; marked = over half of cells in multiple low magnification fields are immunopositive; moderate = cell densities of positive cells between those of mild and severe). Kappa and lambda stains were estimated by quantitative scoring as the maximal number of immunopositive plasma cells in any 5 consecutive HPFs. Based on criteria reported in literature, a kappa to lambda ratio greater than 4.0 (kappa restricted) or less than 0.5 (lambda restricted) was considered clonal 4, 27. Using these cutoffs, the results were reported as either polyclonal or monoclonal. IgG and IgG4 were similarly scored by calculating the maximal number of IgG‐ and IgG4‐positive plasma cells in any consecutive 5 HPFs, and the results were expressed as a ratio of IgG4/IgG (percentage). More specifically, regions of interest were outlined using dotting pens in consecutive sections stained with IgG and IgG4 in order to ensure that the same areas were included in both counts, before ratios were determined. The final counts were divided by five in order to determine a final count/HPF. Final IgG4 counts >10/HPF and IgG4/IgG ratios >25% were considered significant.

Results

The clinical details are highlighted in Table 1. There was a female predominance and most lesions were intracranial, except one case where the mass was spinal. All masses were single and four patients had recurrent tumors (either current presentation or subsequent). Associated significant systemic manifestations were not noted in most cases, except for a history of sarcoidosis (case 2), familial thyroid autoimmune disease (case 6) and chronic myeloid leukemia (case 9).

Table 1.

Clinical features

| Case # | Age/gender | Presenting signs and symptoms | Imaging details | Extent of surgery | Follow‐up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45/F | NA | Parasagittal | NA | RF at 13 years |

| 2 | 62/F | Incidental finding | 1.7 cm, homogenously enhancing, left temporal | GTR | RF at 1 year |

| 3 | 22/M | Seizure activity | Left posterior frontal | GTR | Recurred at 3 years |

| 4 | 70/F | NA | Enhancing, extra‐axial mass, left temporal | GTR | RF at 4 years |

| 5 | 54/F | Seizure activity | Right parietal parafalcine | GTR | Recurred at 3 years (current tumor). RF 14 months later |

| 6 | 50/F | NA | Suprasellar | GTR | RF at 14 months |

| 7 | 61/F | Seizure activity, decreased concentration | 6.6 cm, heterogeneously enhancing, extra‐axial, left frontal falcine | GTR | Recurred at 50 months. Alive with residual tumor at 80 months |

| 8 | 32/M | Numbness over right frontoparietal occipital region | 4.7 cm, homogenously enhancing, extra‐axial, left temporal | GTR | RF at 2 months; lost to follow‐up |

| 9 | 46/F | Facial weakness | 2.5 cm, homogenously enhancing, left frontoparietal | GTR | RF at 1 year |

| 10 | 65/F | Confusion, nausea and gait instability | Heterogeneously enhancing, extra‐axial, bifrontal (left > right) | GTR | RF at 1 year |

| 11 | 73/F | Slowly progressive lower limb weakness, bladder and bowel incontinence | Contrast enhancing, intradural, extramedullary lesion at T4/5 | NA | NA |

| 12 | 57/M | Disturbance of taste and smell, intermittent diplopia | Large, contrast enhancing, extra‐axial, centered in left frontal pole | GTR | Recurred at 2 years (case 13) |

| 13 | 59/M | NA | Left orbital recurrence (case 12) | GTR | RF at 16 months |

| 14 | 78/F | Headaches, mild ataxia and left‐sided tinnitus | Contrast enhancing, dural based, left cerebellopontine angle | GTR | RF at 13 months |

| 15 | 63/M | Bilateral lower extremity weakness and hyperreflexia | 6.9 cm, heterogeneously enhancing, extra‐axial, right parasagittal | Near GTR | RF at 2 months |

| 16 | 47/F | Seizure activity | 4.6 cm, homogenously enhancing, extra‐axial, posterior parietal | NA | NA |

GTR = gross total resection; NA = not available; RF = recurrence free.

Detailed imaging studies were available in 12 cases, as highlighted in Table 1. The neuroimaging features generally appeared consistent with meningioma and no obvious features specific for LPM were found in the current study.

Morphologically, most cases were WHO grade I meningioma (10 of 16 cases), with five cases qualifying for WHO grade II and one qualifying as anaplastic (WHO grade III). Most cases had an intratumoral pattern of inflammation with intermingled meningothelial and inflammatory cells. However, two cases were characterized by mostly solid‐appearing meningioma surrounded by dense chronic inflammation at the periphery of the tumor. Although, a perivascular inflammatory pattern was also noted in three cases, none of the cases showed clear features of vasculitis. Eosinophils were not prominent in any case. Lymphoid follicles were noted in a minority of cases, but none featured granuloma formation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Morphological features

| Case # | Grade | Dural invasion | Brain invasion | Other aggressive features | Mitoses per 10 HPF | Psammoma bodies | Lymphoid follicles | Granulomas | Pattern of inflammation | Perivascular inflammation, vasculitis, perivenular phlebitis | Associated vascular thrombosis | Eosinophils |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | II | NA | NA | Sheeting, small cells, hypercellularity, nucleoli | 0 | No | No | No | Intratumoral | No | No | No |

| 2 | I | Yes | NA | No | 1 | Yes | No | No | Intratumoral | No | No | No |

| 3 | II | No | Yes | Chordoid features | 2 | No | Yes | No | Peritumoral | Yes (perivascular inflammation) | No | Mild |

| 4 | I | NA | NA | No | 0 | No | No | No | Intratumoral | No | No | No |

| 5 | II | NA | Yes | Sheeting, nucleoli | 1 | No | No | No | Intratumoral | No | No | No |

| 6 | I | NA | NA | No | 1 | No | Yes | No | Intratumoral | No | No | No |

| 7 | I | NA | NA | No | 1 | No | No | No | Intratumoral | No | No | No |

| 8 | I | Yes | NA | No | 0 | No | Yes | No | Intratumoral | No | No | No |

| 9 | II | No | NA | No | 5 | Yes | Yes | No | Peritumoral | Yes (perivascular inflammation) | No | No |

| 10 | III | No | Yes | Nucleoli, necrosis, small cells, focally chordoid, sarcomatoid | 29 | No | No | No | Intratumoral | No | No | No |

| 11 | II | NA | NA | Necrosis | 6 | Yes | No | No | Intratumoral | Yes (perivascular inflammation) | No | No |

| 12 | I | NA | NA | Focally rhabdoid | 1 | No | No | No | Intratumoral | No | No | No |

| 13 | I | Yes | NA | Sheeting | 1 | Yes | No | No | Intratumoral | No | No | No |

| 14 | I | NA | NA | None | 0 | Yes | No | No | Intratumoral | No | No | No |

| 15 | I | NA | NA | None | ND | No | No | No | Intratumoral | Yes (perivascular inflammation) | No | No |

| 16 | I | NA | No | None | <4 | Yes | No | No | Intratumoral | No | No | No |

HPF = high power field; NA = not applicable (eg, no brain present); ND = not done.

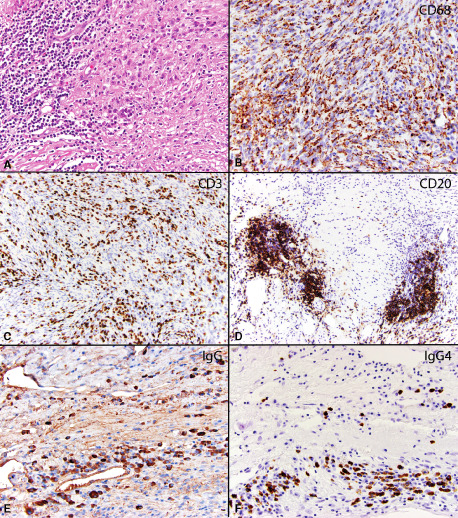

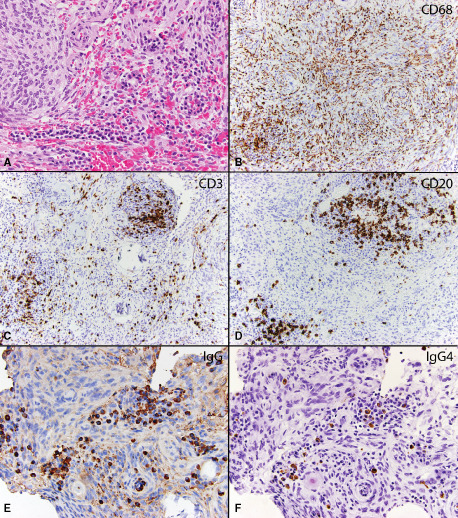

Table 3 highlights the immunohistochemical features in all cases. EMA positivity was found in all cases where it was performed (12 of 12). There was variable PR expression in 10 cases and no staining in 2 cases. The Ki‐67 proliferation index ranged from 1% to 40% and was mostly elevated (>4%) in higher grade examples. Characterization of the inflammatory infiltrate by IHC revealed the lymphocytes to be predominantly CD3‐positive T cells with a variable, but consistently smaller number of CD20‐positive B cells. All cases featured a dense (marked) infiltrate of CD68‐ or CD163‐positive macrophages, such that the macrophage was consistently the most abundant inflammatory cell present (Figures 1 and 2). Plasma cells were characterized by CD138 staining and ranged from mild to marked infiltrates, although this was often not a prominent feature as they were scored as absent to only mild in 11/16 (69%) cases. In all but one case, kappa and lambda studies revealed a polyclonal phenotype. In one case (case 14), monoclonality was suggested immunohistochemically, but there were no other morphologic, immunohistochemical or clinical features to suggest an underlying plasma cell dyscrasia or lymphoma. IgG‐positive plasma cells ranged from 0 to 107 (median 7.5)/HPF and IgG4‐positive plasma cells ranged from 0 to 32 (median 0)/HPF. However, only two cases had IgG4 numbers greater than 10/HPF (cases 9 and 14) and in both of these, this was only a focal finding. Calculation of the ratio of IgG/IgG4 as a percentage also revealed an increase in these same two cases, although again it was a focal feature (Figures 3 and 4). Four cases had no plasma cells and, therefore, no IgG, IgG4, kappa or lambda subclass staining.

Table 3.

Immunohistochemical features

| Case # | EMA | PR | Ki‐67 index (%) | CD20‐positive B cells | CD3‐positive T cells | CD68/CD163‐positive macrophages | CD138‐positive plasma cells | IgG4/HPF | IgG/HPF | IgG4/IgG (%) | Kappa/lambda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ND | ND | ND | Mild | Moderate | Marked | Mild | 0 | 0 | NA | Only rare staining |

| 2 | Positive | Positive | Low (per report) | Mild | Moderate | Marked | Mild | 0 | 4 | 0 | Polyclonal |

| 3 | Positive | Negative | ND | Moderate | Marked | ND | Mild | 5 | 105 | 5 | Polyclonal |

| 4 | Positive | ND | ND | Mild | Marked | Marked | Mild | 0 | 4 | 0 | Polyclonal |

| 5 | Positive | Negative | 16 | Moderate | Marked | Marked | Moderate | 2 | 107 | 2 | Polyclonal |

| 6 | ND | ND | ND | Moderate | Marked | Marked | Mild | 1 | 6 | 4 | Polyclonal |

| 7 | Positive | Positive | 7 | Mild | Marked | Marked | Mild | 0 | 12 | 0 | Polyclonal |

| 8 | Positive | Positive | 3 | Moderate | Marked | Marked | Marked | 1 | 70 | 2 | Polyclonal |

| 9 | Positive | Positive | 17 | Moderate | Marked | Marked | Moderate | 32 | 103 | 31 | Polyclonal |

| 10 | Positive | Positive | 40 | Mild | Marked | Marked | Marked | 0 | 98 | 0 | Polyclonal |

| 11 | Positive | Positive | 8 | Mild | Moderate | Marked | Mild | 0 | 9 | 0 | Polyclonal |

| 12 | Positive | Positive | 4 | Mild | Moderate | Marked | None | 0 | 0 | NA | No plasma cells |

| 13 | Positive | Positive | 3 | Mild | Moderate | Marked | None | 0 | 0 | NA | No plasma cells |

| 14 | Positive | Positive | 3 | Moderate | Moderate | Marked | Marked | 27 | 92 | 30 | Inconclusive† |

| 15 | ND | Positive | 1 | Mild | Mild | Marked | None | 0 | 0 | NA | No plasma cells |

| 16 | ND | ND | <8 | Mild | Moderate | Marked | None | 0 | 0 | NA | No plasma cells |

†Immunostains suggested kappa restriction in case 14, although there was no additional morphologic, immunohistochemical or clinical evidence to support a lymphoproliferative disorder.

EMA = epithelial membrane antigen; HPF = high power field; NA = not applicable because of lack of plasma cells; ND = not done; PR = progesterone receptor.

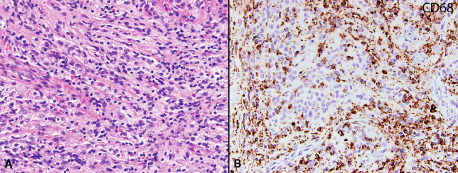

Figure 1.

Case 13: WHO grade I meningioma with an intratumoral infiltrate of lymphocytes (original magnification 200x) A. Immunohistochemical stain for CD68 showing many macrophages within the tumor (original magnification 20x) B.

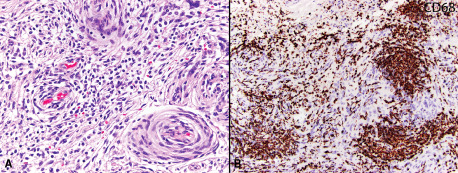

Figure 2.

Case 15: WHO grade I meningioma with an intratumoral infiltrate of lymphocytes, including a focal perivascular distribution (original magnification 200x) A. Immunohistochemistry for CD68 reveals many macrophages within the tumor (original magnification 200x) B.

Figure 3.

Case 9: Atypical (WHO grade II) meningioma surrounded by dense chronic inflammation with many admixed histiocytes. The inflammation is mostly at the edge of the tumor (original magnification 200X) A. Immunohistochemical stains for CD68 reveals numerous macrophages within the tumor (original magnification 200X) B, while CD3 reveals numerous T lymphocytes (original magnification 20X) C and CD20 reveals moderate numbers of B lymphocytes within the tumor, including occasional lymphoid follicle formation (original magnification 200X) D. An immunohistochemical stain for IgG reveals moderate numbers of IgG positive plasma cells within the tumor (103/hpf) (original magnification 200X). Inset: another field of view showing many IgG positive plasma cells (original magnification 100x) E. An immunohistochemical stain for IgG4 reveals clusters of IgG4 positive plasma cells, reaching up to 32/hpf (original magnification 200X) F.

Figure 4.

Case 14: WHO grade I meningioma with an intratumoral infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells (original magnification 200X) A. Immunohistochemical stains for CD68 reveals numerous macrophages within the tumor (original magnification 200X) B. A stain for CD3 reveals moderate numbers of T lymphocytes (original magnification 200X) C, while CD20 reveals moderate numbers of B lymphocytes within the tumor (original magnification 200X) D. An immunohistochemical stain for IgG reveals clusters of IgG positive plasma cells (92/hpf) (original magnification 200X) E and IgG4 shows focally significant numbers of IgG4 positive plasma cells (27/hpf) (original magnification 200x) F.

Discussion

LPM represents one of the least common and poorly characterized variants of meningioma. As such, there remains considerable controversy over diagnostic definitions, etiology, therapeutic implications and even whether or not this represents a distinct or clinically meaningful diagnosis. Specifically, what exact percentage of inflammatory cells needs to be present in a meningioma to qualify as LPM designation is unclear, and previous studies may have suffered from too lax, or too stringent criteria. For this reason, additional studies are sorely needed. We specifically attempted to confine our work to meningiomas where at least in one region of the tumor the inflammation predominated over the meningeal counterpart.

With these criteria, our study shows that the majority of LPMs have no clear association with IgG4 disease, but that there can occasionally be an increase in IgG4‐positive plasma cells at least focally. Unfortunately, both of our “positive” cases were recent biopsies with limited follow‐up times, such that it is difficult for us to determine any meaningful differences between these cases and either LPMs without IgG4 plasma cells or more typical meningiomas with limited inflammation. Nonetheless, there was no known systemic disease and only a single meningioma was present in these two patients rather than diffuse thickening or multifocal meningiomas. These two patients are currently being treated as standard surgical cases, that is, no differently than they would be for a conventional meningioma.

Associations between meningiomas and inflammatory responses or inflammatory disorders have not been thoroughly studied, although perhaps some overlap exists between LPM and some examples of chordoid meningiomas. In the original description, chordoid meningiomas were frequently associated with prominent lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, lymphoid follicles, germinal center formation and systemic features of Castleman's disease, iron‐resistant microcytic anemia and/or hypergammaglobulinemia that resolved after meningioma resection and recurred with tumor regrowth 20. Although larger series have failed to demonstrate a strong association of chordoid meningiomas with systemic manifestations, a mild‐to‐moderate inflammatory component was noted in approximately 60% of cases in one large series 8, whereas more pronounced inflammatory responses and systemic disorders continue to be reported in subsets by others 1, 12, 22, 23. This raises the question about the possibility of significant IgG4 plasma cell infiltrates in chordoid meningiomas with prominent inflammation. Our series includes one example (case 3) of a young man with chordoid meningioma containing prominent inflammation. This case revealed dense, mostly, peritumoral inflammation comprised of prominent lymphocytes and plasma cells, including germinal center formation and scattered eosinophils. Although many IgG‐positive plasma cells were noted in this case, the ratio of IgG4/IgG failed to achieve significance. Nonetheless, further studies are needed in chordoid meningiomas to evaluate its association with IgG4 disease or other inflammatory/immune disorders. An additional possible link between chordoid meningiomas and LPMs is the fact that these two can be associated with systemic inflammatory disorders, while this is rarely reported with other meningioma subtypes 2. Up to 21% of LPMs have been associated with systemic manifestations such as hypergammaglobulinemia and/or anemia, especially in younger patients 42; this is highly reminiscent of the experience with chordoid meningiomas, as noted earlier.

The link between inflammation, meningioma and systemic disorders appears complex, but intriguing. In a recent study, Zhu et al reviewed the clinical, radiological and histological features of 19 LPMs along with 43 additional cases from the literature 42. The features are similar to those of conventional meningioma, although young age of onset, lack of female predilection, multifocality, diffuse growth pattern, heterogeneous contrast enhancement, cystic changes and peritumoral brain edema may be more commonly encountered. These features were not obvious in our current study, although it was limited to 15 patients, which is nonetheless large for a series on LPM, but underpowered for detection of clinic–radiologic associations. It should also be noted that although recurrence and survival rates have been mostly favorable, clinical follow‐up has been limited in the literature (>3 years in only 19 patients). It still remains unclear whether the inflammation is secondary to the meningioma or whether in some cases, the meningothelial proliferation is reactive to a primary inflammatory process 39.

Finally, our series was not only limited to WHO grade I LPMs, but also included higher grade examples. This therefore expands the known spectrum of LPM to include more atypical WHO grade II and anaplastic WHO grade III cases. In most of our cases, the evidence argued against any possible association with IgG4 disease. Additionally, the fact that significant IgG4 positivity was noted in a small subset of our cases is, in itself, not diagnostic of IgG4 disease. In a consensus statement by Deshpande et al, strict diagnostic criteria should be followed to diagnose IgG4‐sclerosing disease 10. In our series, aside from the consistent presence of dense lymphoplasmacytic/macrophage inflammation, the other diagnostic features were either absent (perivenular phlebitis) or present, but not as classically reported (eg, fibrosis present, but not in a storiform fashion). In terms of diagnostic cutoffs for IgG4 disease in tissue, the literature is diverse and many different values have been offered 5, 9, 11, 16, 24, 29, 41. Lindstrom et al have suggested that the presence of more than 10 IgG4‐positive plasma cells/HPF is indicative of IgG4 meningeal disease 24. At the international symposium on IgG4‐related disease held in Boston in 2011, however, Deshpande and colleagues described cutoffs specific to each organ type, and for meninges, they felt that there was insufficient experience to provide definitive criteria 10. In terms of IgG4/IgG ratio, many researchers have suggested values greater than 40% as significant 6, 7, 32. This is mostly consistent with the study by Lindstrom et al where cases with IgG4‐related meningeal disease had IgG4/IgG ratios in the range of 24%–60% (average 42%). However, the ratio should be considered significant only in corroboration with other features of IgG4 disease, as significant overlapping ratios may be seen in non‐IgG4‐related conditions 10. In the current study, the same two cases reached significance for both levels of IgG4/HPF and the IgG4/IgG ratio. As such, it is possible that rare examples of LPM are associated with IgG4 disease. However, caution should be used in interpretation of the findings of elevated IgG4‐positive plasma cells in isolation, particularly when only qualifying focally as in our cases. Within the spectrum of IgG4‐sclerosing disease, many cases may not fulfill or partially fulfill the criteria for this entity. Deshpande et al have therefore proposed classification into categories as highly suggestive, probable or insufficient evidence for IgG4 disease 10. Because the literature on CNS IgG4 disease is still limited, meningeal involvement is currently proposed as probable IgG4‐sclerosing disease 10. The CNS manifestations of IgG4 disease as well as the findings of our current study require further research to better understand and define this entity in this location.

Additionally, no marker is entirely specific, including serum IgG4 levels; indeed, these markers may be elevated to significant levels in non‐IgG4‐related conditions including inflammatory processes, as well as malignancies 9, 21, 28, 35, 41. There is therefore a need to define additional markers to add specificity to the diagnosis. FOXP3 (a marker for CD25‐positive T‐regulatory cells) has been well studied in immune‐mediated processes 31. Its relevance in the context of IgG4‐sclerosing disease lacks sufficient data and maybe a potential surrogate marker to be further evaluated.

This study also discovered the consistent presence of numerous macrophages (defined by either CD68 or CD163) in the entire series. This suggests that macrophages are a consistent accompanying population in LPMs. As such, it is possible that “inflammation‐rich meningioma” is a more accurate term for these cases.

Conclusion

IgG4‐positive plasma cells are rarely a component of meningiomas with a prominent inflammatory component. Their significance in this context is unclear and may require further research. In contrast, macrophages consistently form the most abundant cell type within inflammation‐rich meningiomas.

References

- 1. Arima T, Natsume A, Hatano H, Nakahara N, Fujita M, Ishii D et al (2005) Intraventricular chordoid meningioma presenting with Castleman disease due to overproduction of interleukin‐6. Case report. J Neurosurg 102:733–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cassereau J, Lavigne C, Michalak‐Provost S, Ghali A, Dubas F, Fournier HD (2008) An intraventricular clear cell meningioma revealed by an inflammatory syndrome in a male adult: a case report. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 110:743–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chan SK, Cheuk W, Chan KT, Chan JK (2009) IgG4‐related sclerosing pachymeningitis: a previously unrecognized form of central nervous system involvement in IgG4‐related sclerosing disease. Am J Surg Pathol 33:1249–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang CC, Schur BC, Kampalath B, Lindholm P, Becker CG, Vesole DH (2001) A novel multiparametric approach for analysis of cytoplasmic immunoglobulin light chains by flow cytometry. Mod Pathol 14:1015–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Takahashi N, Zhang L et al (2006) Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis: the Mayo Clinic experience. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 4:1010–1016, quiz 934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheuk W, Chan JK (2010) IgG4‐related sclerosing disease: a critical appraisal of an evolving clinicopathologic entity. Adv Anat Pathol 17:303–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheuk W, Yuen HK, Chu SY, Chiu EK, Lam LK, Chan JK (2008) Lymphadenopathy of IgG4‐related sclerosing disease. Am J Surg Pathol 32:671–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Couce ME, Aker FV, Scheithauer BW (2000) Chordoid meningioma: a clinicopathologic study of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 24:899–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deshpande V, Chicano S, Finkelberg D, Selig MK, Mino‐Kenudson M, Brugge WR et al (2006) Autoimmune pancreatitis: a systemic immune complex mediated disease. Am J Surg Pathol 30:1537–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deshpande V, Zen Y, Chan JK, Yi EE, Sato Y, Yoshino T et al (2012) Consensus statement on the pathology of IgG4‐related disease. Mod Pathol 25:1181–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dhall D, Suriawinata AA, Tang LH, Shia J, Klimstra DS (2010) Use of immunohistochemistry for IgG4 in the distinction of autoimmune pancreatitis from peritumoral pancreatitis. Hum Pathol 41:643–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Epari S, Sharma MC, Sarkar C, Garg A, Gupta A, Mehta VS (2006) Chordoid meningioma, an uncommon variant of meningioma: a clinicopathologic study of 12 cases. J Neurooncol 78:263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hamano H, Kawa S, Horiuchi A, Unno H, Furuya N, Akamatsu T et al (2001) High serum IgG4 concentrations in patients with sclerosing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med 344:732–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hsing MT, Hsu HT, Cheng CY, Chen CM (2013) IgG4‐related hypophysitis presenting as a pituitary adenoma with systemic disease. Asian J Surg 36:93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ishida M, Hotta M, Kushima R, Shibayama M, Shimizu T, Okabe H (2009) Multiple IgG4‐related sclerosing lesions in the maxillary sinus, parotid gland and nasal septum. Pathol Int 59:670–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kamisawa T, Funata N, Hayashi Y, Eishi Y, Koike M, Tsuruta K et al (2003) A new clinicopathological entity of IgG4‐related autoimmune disease. J Gastroenterol 38:982–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kamisawa T, Funata N, Hayashi Y, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Amemiya K et al (2003) Close relationship between autoimmune pancreatitis and multifocal fibrosclerosis. Gut 52:683–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kanno H, Tanino M, Watanabe K, Ozaki Y, Itoh T, Kimura T et al (2013) Intracranial mass‐forming lesion associated with dural thickening and hypophysitis. Neuropathology 33:213–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Katsura M, Morita A, Horiuchi H, Ohtomo K, Machida T (2011) IgG4‐related inflammatory pseudotumor of the trigeminal nerve: another component of IgG4‐related sclerosing disease? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 32:E150–E152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kepes JJ, Chen WY, Connors MH, Vogel FS (1988) “Chordoid” meningeal tumors in young individuals with peritumoral lymphoplasmacellular infiltrates causing systemic manifestations of the Castleman syndrome. A report of seven cases. Cancer 62:391–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuo TT, Chen TC, Lee LY (2009) Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation of the spleen (SANT): clinicopathological study of 10 cases with or without abdominal disseminated calcifying fibrous tumors, and the presence of a significant number of IgG4+ plasma cells. Pathol Int 59:844–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee DK, Kim DG, Choe G, Chi JG, Jung HW (2001) Chordoid meningioma with polyclonal gammopathy. Case report. J Neurosurg 94:122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lin JW, Ho JT, Lin YJ, Wu YT (2010) Chordoid meningioma: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases at a single institution. J Neurooncol 100:465–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lindstrom KM, Cousar JB, Lopes MB (2010) IgG4‐related meningeal disease: clinico‐pathological features and proposal for diagnostic criteria. Acta Neuropathol 120:765–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lui PC, Fan YS, Wong SS, Chan AN, Wong G, Chau TK et al (2009) Inflammatory pseudotumors of the central nervous system. Hum Pathol 40:1611–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maruya S, Miura K, Tada Y, Masubuchi T, Nakamura N, Fushimi C et al (2010) Inflammatory pseudotumor of the parapharyngeal space: a case report. Auris Nasus Larynx 37:397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nakayama S, Yokote T, Hirata Y, Iwaki K, Akioka T, Miyoshi T et al (2012) An approach for diagnosing plasma cell myeloma by three‐color flow cytometry based on kappa/lambda ratios of CD38‐gated CD138(+) cells. Diagn Pathol 7:131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Narula N, Vasudev M, Marshall JK (2010) IgG(4)‐related sclerosing disease: a novel mimic of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 55:3047–3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Otsuki M, Chung JB, Okazaki K, Kim MH, Kamisawa T, Kawa S et al; Research Committee of Intractable Pancreatic Diseases provided by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan and the Korean Society of Pancreatobiliary Diseases (2008) Asian diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: consensus of the Japan‐Korea Symposium on Autoimmune Pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol 43:403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Perry A, Louis DN, Scheithauer BW, Budka H, Von Deimling A (2007) Meningiomas. In: WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System. Louis DNOH, Weistler OD, Cavenee WK (eds), pp. 164–172. IARC: Lyon. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sakaguchi S (2005) Naturally arising Foxp3‐expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non‐self. Nat Immunol 6:345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sato Y, Kojima M, Takata K, Morito T, Asaoku H, Takeuchi T et al (2009) Systemic IgG4‐related lymphadenopathy: a clinical and pathologic comparison to multicentric Castleman's disease. Mod Pathol 22:589–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shimatsu A, Oki Y, Fujisawa I, Sano T (2009) Pituitary and stalk lesions (infundibulo‐hypophysitis) associated with immunoglobulin G4‐related systemic disease: an emerging clinical entity. Endocr J 56:1033–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stone JH, Zen Y, Deshpande V (2012) IgG4‐related disease. N Engl J Med 366:539–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Strehl JD, Hartmann A, Agaimy A (2011) Numerous IgG4‐positive plasma cells are ubiquitous in diverse localised non‐specific chronic inflammatory conditions and need to be distinguished from IgG4‐related systemic disorders. J Clin Pathol 64:237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tanboon J, Felicella MM, Bilbao J, Mainprize T, Perry A (2013) Probable IgG4‐related pachymeningitis: a case with transverse sinus obliteration. Clin Neuropathol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Venkataraman G, Rizzo KA, Chavez JJ, Streubel B, Raffeld M, Jaffe ES, Pittaluga S (2011) Marginal zone lymphomas involving meningeal dura: possible link to IgG4‐related diseases. Mod Pathol 24:355–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wallace ZS, Khosroshahi A, Jakobiec FA, Deshpande V, Hatton MP, Ritter J et al (2012) IgG4‐related systemic disease as a cause of “idiopathic” orbital inflammation, including orbital myositis, and trigeminal nerve involvement. Surv Ophthalmol 57:26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yamaki T, Ikeda T, Sakamoto Y, Ohtaki M, Hashi K (1997) Lymphoplasmacyte‐rich meningioma with clinical resemblance to inflammatory pseudotumor. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg 86:898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yamashita H, Takahashi Y, Ishiura H, Kano T, Kaneko H, Mimori A (2012) Hypertrophic pachymeningitis and tracheobronchial stenosis in IgG4‐related disease: case presentation and literature review. Intern Med 51:935–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang L, Notohara K, Levy MJ, Chari ST, Smyrk TC (2007) IgG4‐positive plasma cell infiltration in the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. Mod Pathol 20:23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhu HD, Xie Q, Gong Y, Mao Y, Zhong P, Hang FP et al (2013) Lymphoplasmacyte‐rich meningioma: our experience with 19 cases and a systematic literature review. Int J Clin Exp Med 6:504–515. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]