Abstract

Huntington's disease (HD) is characterized by pronounced pathology of the basal ganglia, with numerous studies documenting the pattern of striatal neurodegeneration in the human brain. However, a principle target of striatal outflow, the globus pallidus (GP), has received limited attention in comparison, despite being a core component of the basal ganglia. The external segment (GPe) is a major output of the dorsal striatum, connecting widely to other basal ganglia nuclei via the indirect motor pathway. The internal segment (GPi) is a final output station of both the direct and indirect motor pathways of the basal ganglia. The ventral pallidum (VP), in contrast, is a primary output of the limbic ventral striatum. Currently, there is a lack of consensus in the literature regarding the extent of GPe and GPi neurodegeneration in HD, with a conflict between pallidal neurons being preserved, and pallidal neurons being lost. In addition, no current evidence considers the fate of the VP in HD, despite it being a key structure involved in reward and motivation. Understanding the involvement of these structures in HD will help to determine their involvement in basal ganglia pathway dysfunction in the disease. A clear understanding of the impact of striatal projection loss on the main neurons that receive striatal input, the pallidal neurons, will aid in the understanding of disease pathogenesis. In addition, a clearer picture of pallidal involvement in HD may contribute to providing a morphological basis to the considerable variability in the types of motor, behavioral, and cognitive symptoms in HD. This review aims to highlight the importance of the globus pallidus, a critical component of the cortical‐basal ganglia circuits, and its role in the pathogenesis of HD. This review also summarizes the current literature relating to human studies of the globus pallidus in HD.

Keywords: ventral pallidum, globus pallidus externus, globus pallidus internus, Huntington's disease, basal ganglia

THE GLOBUS PALLIDUS—A CRITICAL COMPONENT OF THE INDIRECT, DIRECT AND LIMBIC PATHWAYS OF THE BASAL GANGLIA

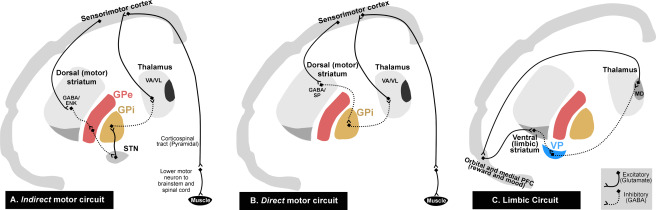

The basal ganglia are integrated into connectional forebrain loops which form cerebro‐cortical/basal ganglia/thalamo/cerebro‐cortical circuits 92. The main functional loops include the “direct” and “indirect” motor circuits, and the limbic circuit 4, 40, 94, 102, 120, 138. A summary of the cortico‐basal ganglia‐thalamo‐cortico loops is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagrams of motor “indirect,” “direct” and limbic cortico‐basal ganglia‐thalamo‐cortical loops. The projections in the cortico‐basal ganglia‐thalamo‐cortical loop form several functionally segregated parallel and interconnected systems. The main functional loops include the motor “indirect” (A) and “direct” (B) circuits, and the limbic (C) circuit. In the indirect pathway (A), the excitatory cortico‐striatal projection terminates on striatal medium spiny neurons that contain GABA/ENK. The striatal output first passes to the inhibitory GPe and then to GPi via the excitatory STN whereby disinhibition of the STN neurons reduces thalamic activation of the cortex. In the direct pathway (B), the cortical excitatory fibers terminate on striatal projection neurons that contain GABA/SP which projects to GPi and SNr. These result in inhibition of the GPi and SNr, and disinhibition of the VA/VL thalamic output to the cerebral cortex. Thus, the result of cortical activation in the direct pathway is opposite to that of the indirect circuit: reinforcement rather than reduction of cortical activity to generate movement. In the limbic circuit (C), the ventral (limbic) striatum, combined with the VP, forms part of a loop system involved in the regulation of mood and emotion. The GABAergic ventral striatum receives excitatory glutamatergic input from orbital and medial PFC. The ventral striatum in turn projects to the GABAergic VP. This information from the VP then projects toward the MD thalamic nucleus, and subsequently back to the orbital and medial PFC. The continuous and dotted lines indicate excitatory and inhibitory pathways, respectively. ENK, enkephalin; SP, substance‐P; GPe, globus pallidus external segment; GPi, globus pallidus internal segment; VP, ventral pallidum; STN, subthalamic nucleus; VA/VL, ventral anterior/ventral lateral thalamic nuclei; MD, medial dorsal thalamic nucleus; Orbital and medial PFC, orbital and medial prefrontal cortex.

The main flow of cortical information through the motor circuits of the basal ganglia is termed the “direct” and “indirect” pathways 2, 4, 22, 44, 101, 120. Understanding these pathways is critical to understanding the physiology of motor impairments in Huntington's disease (HD). According to these pathway models, cortical information (originating from the premotor, supplementary motor and primary motor cortices), which passes to the striatum, is processed and transmitted through the basal ganglia via two main routes. First, a direct GABAergic inhibitory input flows from the striatum to the output nuclei of the basal ganglia, which includes the globus pallidus internal segment (GPi) (direct pathway). Second, an indirect output from the striatum to the globus pallidus external segment (GPe) provides, in turn, an inhibitory input to the glutamatergic subthalamic nucleus (STN), which projects an excitatory output to the GPi (indirect pathway). The indirect pathway can be viewed as a polysynaptic dis‐inhibitory pathway through the GPe and STN. Therefore, the direct and indirect pathways converge on the GPi, which provides an inhibitory output projection to the ventral anterior and ventral lateral (VA/VL) nuclear regions of the thalamus. The VA/VL thalamic nucleus projects an excitatory input mainly to the frontal and premotor cortex, which subsequently influences the motor cortical output 31, 66, 85.

The GPe is the component of the indirect circuit which relays striatal input toward the STN 70. In comparison, the GPi receives input from the striatum, GPe and STN in both the indirect and direct circuits, and projects the information outside the basal ganglia 90. This highlights the fact that these nuclei have differing involvement in the basal ganglia circuitry. In both the indirect and direct pathways the excitatory cortico‐striatal projection terminates on striatal medium spiny projection neurons (MSNs), which are the principal neurons of the striatum. A dramatic set of findings made in the 1980s found that the cells of origin leaving the striatum toward the direct and indirect pathways express different neuropeptides that coexist with gamma‐amino butyric acid (GABA) 43, 45, 50, 81. The striatal efferents passing through the GPi arise from MSNs which contain GABA as the principal neurotransmitter and the neuropeptide substance‐P 9, 50, 81. In contrast, striatal efferents to GPe arise from MSNs which contain GABA and the neuropeptide enkephalin 45, 50, 82. The two classes of MSNs can also be subdivided based on the kinds of dopamine receptors they express. The D1 dopamine receptor class is mainly expressed on substance‐P containing MSNs, which form part of the direct circuitry, whereas the D2 class is specifically expressed on enkephalin‐containing MSNs, forming part of the indirect circuit 126. In essence, MSNs which express D1 receptors and substance‐P project to the GPi, whereas those expressing D2 receptors and enkephalin project toward the GPe 38, 39, 126.

The indirect and direct pathways have apparently opposing effects upon the output nuclei and the thalamic target nuclei. In the indirect pathway, the excitatory glutamatergic cortico‐striatal projection terminates on striatal MSNs that contain GABA, enkephalin (ENK) and dopamine D2‐class receptors, thereby reducing the output of GPe GABAergic activity. This leads to the decreased inhibition (or disinhibition) of STN neurons, triggering an increase in glutamatergic activation of the GPi and substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) output regions. The increase in GPi activation reduces thalamic activation of the cortex. Activation of the indirect circuit leads to “negative feedback” as opposed to the “feed forward” effect of direct circuit activation (Figure 1, panel A). In the direct pathway, the excitatory glutamatergic fibers of the cortico‐striatal projection terminate on striatal MSNs that contain GABA, substance‐P and dopamine D1‐class receptors. This increased activity of GABAergic MSNs exerts an inhibitory influence on GPi and SNr neurons. Because the neurons of the GPi and SNr are GABAergic (inhibitory), their inhibition leads to an increase in activity of the glutamatergic thalamo‐cortical neurons on which they synapse. Thus, activation of the direct pathway is opposite to that of the indirect pathway, supporting thalamo‐cortical interactions via a “positive feedback” mechanism. This makes it clear that excitation of direct pathway MSNs by cortical input leads to reinforcement, rather than reduction in activity of the motor cortex (Figure 1, panel A) 22, 23, 34, 39, 40, 106, 122, 138. This completes the cerebro‐cortical/basal ganglia/thalamus/cerebro‐cortical motor circuit.

In comparison to the dorsal components of the basal ganglia circuitry and their involvement in the direct/indirect motor circuits, the ventral striatum (also known as the nucleus accumbens), combined with the ventral pallidum (VP), forms part of a loop system involved in the regulation of mood and emotion 4, 46, 55, 56, 108. The ventral striatum receives excitatory glutamatergic input from the orbital and medial prefrontal (OMPFC) cortical areas 13, 16, 57, 143. The GABAergic ventral striatal regions that receive fibers from the OMPFC, in turn, project to the GABAergic VP 47, 55. This information from the VP then projects toward the mediodorsal (MD) thalamic nucleus, and subsequently back to the OMPFC (Figure 1, Panel C) 48, 97, 103.

INTRODUCTION TO THE HUMAN GLOBUS PALLIDUS

The globus pallidus or pallidum (GP) is the principle target of striatal outflow and is a core structure of the basal ganglia. It is a triangular mass of cells which lies along the medial aspect of the putamen. The GP is divided by a medial medullary lamina into the GPe and GPi segments. The ventral pallidum (VP) is distinguished from the dorsal GPe and GPi, based on its close connections with limbic structures, with the anterior commissure serving as an anatomical border. The term “globus pallidus” comes from the pale appearance of the GP, which is due to the low density of neurons surrounded and encapsulated by large numbers of myelinated axons (white matter) 27, 42, 94. The GPe and GPi receive mainly sensorimotor and associative cortical information via the indirect and direct motor circuits involving the dorsal striatum. As components of the dorsal striatopallidal system, the GPe and GPi both play a predominant role in initiating motor activity. In contrast, the VP largely receives limbic cortical information via the ventral striatum, and as part of the ventral striatopallidal system, the VP has a role in regulating emotion and initiating movement in response to emotional or motivation stimuli 4, 5, 46, 56, 62, 70, 90.

The neuronal population in the GP is comprised mainly of GABAergic pallidal projection neurons, which suggests that they have an inhibitory effect on their target neurons 2, 95, 96, 104. Structurally, the GP differs from the striatal nuclei, being predominantly composed of large, widely spaced fusiform cells, containing triangular or polygonal cell bodies, with up to four thick dendrites extending to 700 µm in length 26, 36, 37, 102, 142. Pallidal neurons are sparse in distribution compared to striatal neurons, and are 100 times less numerous than spiny striatal projection neurons, meaning that there is convergence in the striatal‐pallidal projection such that a single pallidal receives input from approximately ∼100 striatal neurons 42, 141. The axon of a single pallidal neuron can travel for a very long distance, innervating a diverse range of neuronal types 12, 73, 120. Pallidal neurons have long, thick, smooth, sparsely spiny, poorly branching dendrites 37. Pallidal dendrites are densely innervated by synapses which cover the entire dendrite 26, 27, 36. The majority of these synapses represent GABAergic input, provided by the GABAergic striato‐pallidal pathway, which terminates on cell dendrites and soma of pallidal efferent neurons 12, 95, 112. Myelinated striatal axons cross perpendicular to pallidal discoidal dendritic fields and provide unmyelinated collaterals (described as “woolly fibers”) parallel to pallidal dendrites with which they repeatedly synapse 27, 49. These woolly fibers can be stained using immunohistochemistry specific for peptides, such as enkephalin and substance‐P 50.

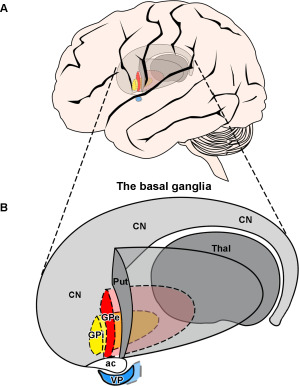

The cellular morphology of GPi neurons is similar to that of the GPe. Three types of pallidal projection neurons have been identified based on their neurochemistry and morphology properties: Type 1 and 2 are the largest in size, have been described in multiple mammalian species, and make up 80%–90% of the total population of pallidal neurons in the GP 26, 36, 37, 134. When labeled with Nissl stains, the majority of these neuronal cell soma in the GP are large (35–70 µm), contain varying amounts of Nissl granules, and appear elongated with a triangular or spindle‐shaped cell soma 27. Type 1 pallidal neurons contain GABA (gamma‐aminobutyric acid) 121 and the calcium‐binding protein parvalbumin 69, but are immunonegative for any other immunohistochemical markers and make up about 10% of the large pallidal neuron population 134. Type 2 cells are identical in cell morphology to type 1 cells, but are subdivided into “type 2” based on their double calcium‐binding protein immunoreactivity 35. These large pallidal neurons co‐label for both parvalbumin and calretinin (another calcium‐binding protein) on the same cells, and make up 90% of the large human pallidal neuron population 35, 134. Medium‐sized type 3 neurons in the globus pallidus have also been described in previous studies 26; in primates they are intensely immunoreactive for calretinin only 69, are less than 25 µm in cell soma size, and in the human make up approximately 10%–20% of the total number of neurons in the human globus pallidus 134. It is possible that the smaller neurons with spiny dendrites are local circuit neurons/interneurons 26, 37. The main subdivisions of the globus pallidus, the external segment (GPe), internal segment (GPi) and ventral pallidum (VP), are highlighted in Figure 2 and will be discussed in detail.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of a lateral view of the human brain depicting the location of the globus pallidus externus (GPe), internus (GPi) and ventral pallidum (VP) in the basal ganglia. Diagram showing a (A) lateral view of the brain with the location of the basal ganglia, and a (B) three‐dimensional schematic lateral view of the GPe, GPi and VP. Note the putamen (Put) is located most laterally, and the globus pallidus internal segment (GPi) is located most medially (represented with dotted lines). The GPe (solid red) is located most caudomedially to the striatum. The GPi (solid yellow) is located medially to the GPe. The VP (solid blue) is located ventrally to the GPe, and is separated by the anterior commissure. Abbreviations: Put, putamen; CN, caudate nucleus; ac, anterior commissure; Thal, thalamus; GPe, globus pallidus external segment; GPi, globus pallidus internal segment; VP, ventral pallidum.

THE GLOBUS PALLIDUS EXTERNAL SEGMENT

Located caudomedially to the striatum (Figure 2), the external segment of the globus pallidus (GPe) is a relatively large nucleus, which receives major input from two major basal ganglia nuclei, the striatum and the STN 70. The GPe receives massive GABAergic afferent fibers from the striatum and glutamatergic afferent fibers from the STN. The GPe also receives sparse afferents from the cerebral cortex, thalamus, GPi, SNc, raphe nuclei and pedunculopontine tegmentum 25, 33, 53, 69, 102, 140. In both rodents and primates, the majority, if not all of the striatal projection neurons project to the GPe, with approximately half of the neurons projecting to the GPe only, and the other half providing collaterals to the GPe en route to the GPi and SNr 65, 98, 139.

The output of the GPe is GABAergic, and inhibitory on its targets 61. Most neurons of the GPe are projection neurons, which are GABAergic in nature 69, 72, 95, 104, 121. GPe neurons project to most of the basal ganglia nuclei, including the STN 14, 15, 93, striatum 10, internal globus pallidus (GPi) 53, 123 substantia nigra 99 and other GPe neurons 60, 70. A single‐axon tracing study of neurons in the GPe of primates demonstrated that based on their axonal targets, ∼84.2% of the total number of GPe axons studied projected to the STN. However, none of these axons projected only to the STN. In fact, 52.6% branched to both the STN and SNr, 18% branched to both the STN and GPi, and 13.2% branched to the STN, SNr and GPi 116. Because GPe output connects to virtually every other basal ganglia nucleus, this makes the GPe a crucial component of the indirect pathway of the basal ganglia motor circuit, which is critical in relaying striatal input to the STN 40, 120. Furthermore, the literature suggests that the GPe is an important integrative locus in the basal ganglia. This organization allows single GPe pallidal neurons to exert an effect not only on the STN, which is the main GPe target, but also on two major output structures of the basal ganglia, the SNr and GPi.

In terms of neurochemical architecture, the GPe can be distinguished laterally from the striatum, and medially from the GPi in the human brain, based on the high expression of the neuropeptide enkephalin, which originates in striatal fibers that project directly into the region. The anterior commissure separates the GPe dorsally from the subcommissural VP 45, 50.

THE GLOBUS PALLIDUS INTERNAL SEGMENT

Located medially to the external segment (GPe), the GPi is separated from its larger counterpart by the medial medullary lamina (Figure 2). The GPi is a final output station of the basal ganglia, through which body movement is controlled 21, 90. Although the GPe and GPi share a common neurotransmitter (GABA) and have similar cellular morphology, they are distinct in terms of function and place in the basal ganglia circuitry.

The striatum sends rich GABAergic afferents to the GPi, with about 70% of the total number of synaptic terminals in contact with GPi neurons originating from striatal spiny neurons 117. The striatum projects to the GPi via two major projection systems, the direct and indirect pathways 4. The direct pathway arises from GABAergic striatal neurons which contain substance‐P and projects monosynaptically to the GPi. The indirect pathway arises from GABAergic striatal neurons containing enkephalin, and projects polysynaptically to the GPi by a series of connections involving the GPe and STN 90. Two other major inputs to the GPi are glutamatergic afferents from the STN (about 10%), and GABAergic afferents from the GPe (about 15%) 90, 117, 123. Other inputs into the GPi include glutamatergic input from the intralaminar nuclei of the thalamus, serotonergic input from the dorsal raphe nucleus, glutamatergic and cholinergic input from the pedunculopontine nucleus and dopaminergic input from the substantia nigra 78, 79, 80.

The neuronal population in the GPi is comprised of GABAergic pallidal neurons, which have an inhibitory effect on their target neurons 2. The GPi projects to the ventral anterior/ventral lateral (VA/VL) nucleus of the thalamus in primates, where GPi pallidal fibers entering the thalamus give off several collaterals and terminate primarily on thalamic projection neurons 68, 76. The thalamic neurons which receive GPi input project to the striatum as well as the primary motor cortex, supplementary motor area and premotor cortex 90. Therefore, the GPi has a major role in gathering movement‐related activity from the striatum, GPe and STN, integrating this information and conveying the processed information outside the basal ganglia toward the thalamus, and motor cortices. In addition, GPi pallidal neurons also project to the lateral habenular nucleus (involved in the limbic reward pathway) and the motor pedunculopontine nucleus, which suggests an integrative role for the GPi in other circuits in the brain, including the reward pathway 99, 100.

In terms of neurochemical architecture, the GPi can be distinguished medially from the GPe in the human brain on the basis of its high expression of the neuropeptide substance‐P, which originates in striatal fibers that project directly into the region. This difference in neuropeptide expression in the GPi compared to the GPe reflects how the striatal afferents to the GPi originate in a different population of striatal neurons, containing either enkephalin (for the GPe) or substance‐P (for the GPi) 45, 50, 81.

THE VENTRAL PALLIDUM

The VP was first identified in 1975 as a primary GABAergic output for the ventral striatum, located immediately ventral to the anterior commissure (Figure 2B) 51, 58. This area has been included as part of the pallidum based on shared histological criteria, including the presence of “pallidal‐like” projection neurons, and the fact that its main source of input is the ventral striatum 55. It has also been shown that the VP contains heterogeneous cell types, including cholinergic and GABAergic projection neurons 119. Notions of the VP as a striatal output for movement, comparable to the GP, arose from the view that it functioned as a motor expression region 56. For example, based on a series of behavioral studies, Mogenson and Yang proposed that the nucleus accumbens projections to the VP translated limbic motivation signals into motor output 88. This account attributed the “limbic‐motor integration” to the accumbens‐pallidal system, and specifically identified ventral pallidal projections to the brainstem (ie, pedunculopontine tegmentum) as a primary motor output for limbic motivation signals. The VP also receives glutamatergic input from the subthalamic nucleus 71, 128. Likewise, dopaminergic projections from both the substantia nigra and the ventral tegmental area (midbrain regions associated with the basal ganglia and limbic systems, respectively) terminate in the VP 74, 91.

The VP projects back to nearly all of its input sources, including the nucleus accumbens, for reciprocal information exchange 124. The VP also projects to the subthalamic nucleus and hypothalamus, as well as midbrain structures including the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area 48, 51. Further, fibers innervate the pedunculopontine nucleus, a key structure involved in the reward circuit 75. Additionally, output from the VP re‐enters corticolimbic loops via direct projections to the medial prefrontal cortex, and dense projections to the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus 48, 103, 109, 145. The VP also projects back to both the GPe and GPi, which is a unique projection, in that the dorsal structures (the GPe and GPi) do not project to the VP 46. Parts of the VP also project to the lateral habenular nucleus, which is part of the reward circuit 84, 89.

Currently, the VP is an area of focus in the study of addictive behaviors 87, 118, 127. Evidence supporting the notion that the VP may be involved in motivation and hedonics has been uncovered in both animal and human studies. A recent clinical report describes a former drug‐addicted human patient, who, after an extreme overdose, became unresponsive, hypoxic and hypotensive. He was found to have selective bilateral lesions to the VP, and reported the disappearance of all drug cravings and then remained abstinent from recreational drugs, reporting a loss in “pleasure.” The patient also reported a depressed mood, with noted “anhedonia”—an inability to feel pleasure 86. Furthermore, a patient with bilateral damage to the globus pallidus, which extended to the VP, reported an “inability to feel emotions” and a “profound lack of motivation” 129. Reward cues also activate the VP, as shown by cue‐triggered “craving” of drugs. Childress et al (2008) presented cocaine‐addicted subjects with pictures of drug‐associated cues (ie, images of taking drugs). These images triggered VP activation as shown through functional MRI 17. Furthermore, it has also been shown that the VP plays a role in sex and social affiliation. VP activity through functional MRI is shown to increase during male sexual arousal and in response to subliminally presented images of happy human faces and sexual images 17, 110, 136.

Thus, the key role of the VP in reward, mood and pleasure processing, as evidenced by these studies, indicates that an exploration into the role of the VP in mood disorders and disorders with a mood component, is warranted. Such limbic‐related anatomical connectivity sets the stage for the VP to mediate reward and motivation functions at many levels of the brain, beyond merely aiding translation to movement 119. The close relation between the ventral striatum and VP within the limbic loop of the basal ganglia led to the coining of the term “ventral striatopallidum” 108. The ventral striatopallidum is known to be an integrator of emotional, cognitive and sensory information, and a linker of motivation to behavior 57, 135.

The human VP, like the GPe and GPi, can be divided chemoarchitectonically into areas based on the extent of substance‐P and enkephalin innervation, which originates in the ventral striatum 50. Staining for these peptides has been useful in defining the boundaries of the VP 26, 36, 50, 81, 112. The rostral pole of the VP can be ventrally separated from the GPe by the anterior commissure 59.

GROSS NEUROPATHOLOGY OF THE HUMAN GP IN HUNTINGTON'S DISEASE

A neuropathological grading system, the framework of which is based on the distinctive, temporospatial pattern of degeneration in the HD striatum, was developed by Vonsattel et al. 131, 132. The assignment of the degree of neuropathological severity is based on gross and microscopic findings on post‐mortem HD tissue. The system has five grades (0–4) of severity of striatal involvement. This grading system applies to brains from individuals diagnosed clinically as having HD, with or without genetic testing confirmation. The following descriptions refer to the gross neuropathological state of the human GP in Huntington's disease:

At Grades 0, 1 and 2: The GP does not show gross macroscopic changes.

Grade 3 comprises 52% of all brains. At grade 3, the CN is dramatically atrophic. The medial outline of the head of the CN forms a straight line, or is slightly concave medially. Both the putamen and globus pallidus now exhibit moderate reductions in size. However, the nucleus accumbens remains unchanged. The GPe shows slight to moderate fibrillary astrocytosis, whereas the GPi does not exhibit the same change.

Grade 4 comprises 28% of all HD brains. The neostriatum neuronal loss is 90% or more. In the most severe grade, gross macroscopic examination reveals an extremely atrophic CN, which presents a concave appearance accompanied with widened lateral ventricles. The medial contour of the head of the CN is concave, as is the CN at the anterior limb of the internal capsule. The putamen decreases markedly in size, with widened perivascular spaces in its ventral portion. At this grade, the nucleus accumbens shows some shrinkage, but is relatively preserved in comparison to the dorsal striatum. In at least 50% of grade 4 brains, the underlying nucleus accumbens (ventral striatum) remains relatively preserved, but is not normal. The external medullary lamina of the GP is not seen, with the GP showing marked atrophy (approximately half the size in comparison to age‐matched controls). Microscopically, neuronal loss and gliosis are evident throughout the CN and putamen. The nucleus accumbens exhibits slight to moderate astrocytosis, mainly in the dorsal region. The GP exhibits astrocytosis, especially in the GPe, and the neurons are seen to be more closely packed together than in age‐matched controls. There is an overall dorsal to ventral, anterior to posterior and medial to lateral progression of neuronal death observed, with the dorsal medial striatum affected earlier than the ventral striatum.

CELLULAR AND RECEPTOR CHANGES IN THE STRIATUM AND GLOBUS PALLIDUS IN HD—RELATION TO THE INDIRECT AND DIRECT MOTOR CIRCUITS

In HD, it has been postulated that the degeneration of the projection neurons within the striatum leads to aberrant activation of the basal ganglia output nuclei, resulting in uncoordinated movement, cognition and emotional control. Various autoradiographic, in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical studies have reported the loss of neurochemicals and neurotransmitters associated with receptors in the striatum. As mentioned above, the most affected neuronal populations in the striatum are the medium‐sized spiny GABAergic projection neurons (MSNs) that constitute ∼90%–95% of the striatal neuronal population. There are two major GABAergic populations of MSNs: 1) those projecting mainly to the external segment of the globus pallidus (GPe), which are typically rich in the neuropeptide enkephalin and devoid of the neuropeptide substance‐P, and 2) those projecting to the internal segment of the globus pallidus (GPi), which are rich in the neuropeptide substance‐P, and poor in enkephalin. MSNs are also associated with a large number of ion channel and metabotropic receptors on the surface membranes including cannabinoid (CB1) 41, GABAA receptors 134 and dopamine receptors (D1 and D2) 63, 67.

MSNs of the indirect motor circuit contain GABA and enkephalin, whereas MSNs of the direct motor circuit contain GABA and substance‐P. In HD, the MSNs degenerate with advancing HD grade 130, 132. Both enkephalin and substance‐P MSNs are lost 29, 83. However, MSNs projecting to the GPe (indirect pathway) that express enkephalin and dopamine D2 receptors have been shown to be most vulnerable to the disease process 1, 7, 24, 111. The enkephalinergic MSNs are shown to degenerate in advance of MSNs that express substance‐P and dopamine D1 receptors that project to the GPi and SNr (direct pathway) 24, 39. In addition, a reduction in glutamate NMDA receptor binding, GABAA receptor binding and cannabinoid receptor binding are all evident in the HD striatum 41, 137, 144, which could be indicative of dysfunction or downregulation of these receptors in addition to the loss of MSNs.

The projections of striatal MSNs to the pallidal output nuclei which contain enkephalin, substance‐P and cannabinoid receptors are progressively lost with advancing HD grade, as shown in post‐mortem tissue, mirroring the loss of MSNs in the striatum. Staining for the neuropeptide enkephalin is dramatically lost in a grade‐dependent manner in the GPe. This reflects the loss of the GABAergic enkephalin‐positive pathway to the GPe (indirect pathway), based on the presymptomatic and early HD grade (grade 0–1) loss of enkephalin immunoreactivity from striatal efferent terminals in the GPe 6, 24, 111, 115. There is also a later loss of substance‐P in the GPi, reflecting the loss of the GABAergic substance‐P positive pathway to the GPi (direct pathway) 3, 111. Quantification of substance‐P immunolabeled terminals within the GPi, in a sample of HD cases ranging from 0 to 4, demonstrated that the loss of striatal projections to the GPi proceeded far more gradually than the loss of enkephalin immunolabeled striatal terminals to the GPe 24. These results were confirmed in a previous study by our group 6, showing that this substance‐P immunoreactivity from striato‐pallidal terminals is progressively reduced in later stages of HD 24, 41. There is also a loss of cannabinoid receptors on the presynaptic terminals of both the direct and indirect pathways 41. Furthermore, associated with the loss of neurotransmitter GABA from the striato‐pallidal indirect and direct pathways, there is a major increase in post‐synaptic GABAA and GABAB receptors, which is proposed to be a compensatory upregulatory response of GABAA receptors on the pallidal output neurons 6, 30, 105. A summary of the main cellular and receptor changes in Huntington's disease is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram detailing the loss of medium spiny neurons in HD and the subsequent impact on receptors in the striatum, globus pallidus external segment (GPe) and globus pallidus internal segment (GPi) of the brain. In the striatum, the GABAergic medium spiny projection neurons (in red) are divided into two groups: 1) those that stain for enkephalin (Enk) and 2) those staining for substance P (Sub P). These project to the large GABAergic pallidal neurons in the GPe and GPi (in blue). The small boxes near the axon terminals in the GPe and GPi represent the presynaptic D1 or D2 dopamine receptors and CB1 cannabinoid receptors. The boxes on the pallidal cells represent post‐synaptic GABAA receptors (GA) and GABAB receptors (GB). In Huntington's disease the medium spiny neurons that degenerate are indicated by dotted lines. Arrows indicate up‐ or downregulation of receptors. 1) The GABA/Enk striato‐GPe neurons of the indirect pathway and their associated receptors are affected in the early stages of the disease while 2) the GABA/Sub P (striato‐GPi) neurons of the direct pathway and receptors are affected in HD cases with advanced pathology. Abbreviations: GPe, globus pallidus external segment; GPi, globus pallidus internal segment; GABA, gamma amino butyric acid.

The disruptions of these striatal pathways in HD have led to hypotheses on how they affect the basal ganglia circuitry in HD. Clear hypotheses have been raised relating the early loss of enkephalinergic indirect pathway MSNs to the symptomatology of HD 2, 24. The loss of striatal neurons that give rise to the indirect pathway could result in increasing the inhibitory action of the GPe upon the STN. The STN then becomes hypofunctional and causes a reduction in the inhibitory action of the GPi upon the thalamus. This subsequent disinhibition of the thalamus is postulated to result in the appearance of uncontrolled chorea movements, a characteristic feature of HD 2, 19, 20, 24, 54. In contrast, the loss of the substance‐P direct pathway MSNs that project from the striatum to the GPi may contribute to dystonia in advanced (grade 3) HD. The nearly complete loss of this projection system by grade 4 may be associated with the akinesia of terminal HD 2, 11, 24. This could be due to an increase in the inhibitory action of the GPi upon the thalamus, reducing the thalamocortical neuronal excitatory input to the cortex, and thereby contributing to a symptom shift from hyperkinesia to hypokinesia 2, 11, 22, 24.

CURRENT INVOLVEMENT OF THE GPE, GPI AND VP IN HD

Neuroimaging studies have reported severe atrophy of the globus pallidus in HD patients 8, 28, 32, 114. However, in vivo imaging studies have not specifically isolated the GPe, GPi or VP, nor have they separately evaluated the extent of volumetric decline in HD. Post‐mortem pathology studies have also reported that significant progressive atrophy of the GPe occurs, with greater atrophy and gliosis observed compared to the GPi based on qualitative and morphometric analysis 77, 113, 132. However, only one stereological approach has reported a decline in GPe volume (42%) and GPi volume (21%) specifically in HD relative to controls 52.

Two studies using non‐stereological methods have reached conflicting conclusions in regards to GPe and GPi pallidal neuron involvement in HD. In one quantitative study by Lange et al. in 1976, which compared six HD cases of unreported grades with 15 control cases, the absolute number of pallidal neurons was shown to decrease by up to 40% in the GPe and 43% in the GPi, which was accompanied by a 50% reduction in pallidal volume 77. However, the neuronal density was up to 42% higher within the GPe and 27% higher in the GPi, and no changes were found in relation to the soma volume of individual pallidal neurons in HD. This morphometric study suggested that pallidal neuronal loss was due to primary degeneration (cell‐autonomous processes), rather than being solely the consequence of striatal degeneration (non‐cell‐autonomous processes), thereby suggesting that pallidal neuron loss also contributes to GP atrophy.

However, more recent studies have proposed an alternative fate for the GP, suggesting that the GP atrophy is mainly due to neuropil loss, resulting from striatal fibers and terminals, and to a lesser extent the loss of neurons 3, 111, 125. Wakai et al. histometrically examined six HD cases (of advanced striatal neuropathological grading) in comparison to 10 control cases. Examination of pallidal neurons in five selected coronal sections taken along the rostral‐caudal axis, using a non‐stereological cell‐counting method, detected no pallidal neuron loss in HD 133. This study supported the hypothesis that no pallidal neuronal depletion was recognized in HD, despite marked atrophy of tissue volume, thereby attributing overall GP atrophy to striato‐pallidal fiber loss and non‐cell autonomous processes.

Currently, neuropathological analyses of limbic associated regions in human HD brains are relatively sparse, with no reported studies in HD post‐mortem tissue documenting cellular changes within the VP. The ventral (limbic) striatum, which has the nucleus accumbens as its major component, appears to be relatively preserved in HD compared to the dorsal (motor) striatum 64, 132. In one study of Parkinson's disease patients with a pathological gambling problem, single‐photon emission computed tomography showed enhanced resting‐state activity (regional cerebral blood flow) in the VP of these individuals compared with non‐gambling PD patients 18. It might therefore be possible that Huntington's disease, like Parkinson's disease, a neurodegenerative disorder involving both the limbic system and basal ganglia, has an association with changes in VP activity.

Despite the extensive literature examining the implications of HD in the striatum in human tissue, very little exists with regard to the impact of striatal loss on the main neurons that receive striatal input, the pallidal neurons. There is also a lack of detailed knowledge concerning the relationship between pallidal neurodegeneration and striatal neuropathological grade and symptom heterogeneity. Furthermore, as the GPe and GPi are critical structures involved in the indirect and direct basal ganglia motor circuits, a better understanding of the extent of their involvement in HD is crucial in order to gain a better understanding of basal ganglia dysfunction. Also, as there is currently no literature which implicates the VP in HD, despite it being a key structure of the limbic pathway, a detailed examination of the VP in HD post‐mortem human tissue is required, in order to determine whether this region is affected by HD and whether it contributes to the clinical symptomatology of HD.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1. Albin RL, Reiner A, Anderson KD, Dure LS, Handelin B, Balfour R et al (1992) Preferential loss of striato‐external pallidal projection neurons in presymptomatic Huntington's disease. Ann Neurol 31:425–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Albin RL, Young A, Penny J (1989) The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci 12:366–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB (1990) Abnormalities of striatal projections neurons and N‐methyl‐d‐aspartate in presymptomatic Huntington's disease. N Engl J Med 322:1293–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alexander GE, Crutcher M (1990) Functional architecture of basal ganglia circuits: neural substrates of parallel processing. Trends Neurosci 13:266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alexander GE, Delong MR, Strick PL (1986) Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci 9:357–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Allen KL, Waldvogel HJ, Glass M, Faull RL (2009) Cannabinoid (CB(1)), GABA(A) and GABA(B) receptor subunit changes in the globus pallidus in Huntington's disease. J Chem Neuroanat 37:266–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Augood S, Faull R, Love D, Emson P (1996) Reduction in enkephalin and substance P messenger RNA in the striatum of early grade Huntington's disease: a detailed cellular in situ hybridization study. Neuroscience 72:1023–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aylward EH, Li Q, Stine OC, Ranen N, Sherr M, Barta PE et al (1997) Longitudinal change in basal ganglia volume in patients with Huntington's disease. Neurology 48:394–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beach TG, McGeer EG (1984) The distribution of substance P in the primate basal ganglia: an immunohistochemical study of baboon and human brain. Neuroscience 13:29–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beckstead RM (1983) A pallidostriatal projection in the cat and monkey. Brain Res Bull 11:629–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berardelli A, Noth J, Thompson PD, Bollen EL, Currà A, Deuschl G et al (1999) Pathophysiology of chorea and bradykinesia in Huntington's disease. Mov Disord 14:398–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bevan MD, Booth PA, Eaton SA, Bolam JP (1998) Selective innervation of neostriatal interneurons by a subclass of neuron in the globus pallidus of the rat. J Neurosci 18:9438–9452. Nov 15; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carmichael ST, Price JL (1996) Connectional networks within the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex of macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol 371:179–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carpenter MB, Batton RR, Carleton SC, Keller JT (1981) Interconnections and organization of pallidal and subthalamic nucleus neurons in the monkey. J Comp Neurol 197:579–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carpenter MB, Fraser RA, Shriver JE (1968) The organization of pallidosubthalamic fibers in the monkey. Brain Res 11:522–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chiba T, Kayahara T, Nakano K (2001) Efferent projections of infralimbic and prelimbic areas of the medial prefrontal cortex in the Japanese monkey, Macaca Fuscata. Brain Res 888:83–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Childress AR, Ehrman RN, Wang Z, Li Y, Sciortino N, Hakun J et al (2008) Prelude to passion: limbic activation by “unseen” drug and sexual cues. PLoS One 3:e1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cilia R, Siri C, Marotta G, Isaias IU, De Gaspari D, Canesi M et al (2008) Functional abnormalities underlying pathological gambling in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 65:1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crossman AR (1987) Primate models of dyskinesia: the experimental approach to the study of basal ganglia‐related involuntary movement disorders. Neuroscience 21:1–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crossman AR, Mitchell I, Sambrook M, Jackson A (1988) Chorea and myoclonus in the monkey induced by gamma‐aminobutyric acid antagonism in the lentiform complex. The site of drug action and a hypothesis for the neural mechanisms of chorea. Brain 111:1211–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. DeLong MR (1971) Activity of pallidal neurons during movement. J Neurophysiol 34:414–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. DeLong MR (1990) Primate models of movement disorders of basal ganglia origin. Trends Neurosci 13:281–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. DeLong MR, Georgopoulos AP ( 1981) Motor function of the basal ganglia. In: Handbook of Physiology, Sect 1: The Nervous System, Vol 2: Motor Control, Part 2. Brookhart JM, Mountcastle VB, Brooks VB (eds), pp. 1017–1061. American Physiological Society: Bethesda. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Deng YP, Albin RL, Penney JB, Young AB, Anderson KD, Reiner A (2004) Differential loss of striatal projection systems in Huntington's disease: a quantitative immunohistochemical study. J Chem Neuroanat 27:143–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Deschênes M, Bourassa J, Doan VD, Parent AA (1996) Single‐cell study of the axonal projections arising from the posterior intralaminar thalamic nuclei in the rat. Eur J Neurosci 8:329–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Difiglia M, Pasik P, Pasik T (1982) A Golgi and ultrastructural study of the monkey globus pallidus. J Comp Neurol 212:53–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Difiglia M, Rafols JA (1988) Synaptic organization of the globus pallidus. J Electron Microsc Tech 10:247–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Douaud G, Gaura V, Ribeiro MJ, Lethimonnier F, Maroy R, Verny C et al (2006) Distribution of grey matter atrophy in Huntington's disease patients: a combined ROI‐based and voxel‐based morphometric study. Neuroimage 32:1562–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Emson PC, Arregui A, Clement‐Jones V, Sandberg BE, Rossor M (1980) Regional distribution of methionine‐enkephalin and substance P‐like immunoreactivity in normal human brain and in Huntington's disease. Brain Res 199:147–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Faull R, Waldvogel H, Nicholson L, Synek B (1993) The distribution of GABA∼ A‐benzodiazepine receptors in the basal ganglia in Huntington's disease and in the quinolinic acid‐lesioned rat. Prog Brain Res 99:105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Faull RLM, Mehler WR (1978) The cells of origin of nigrotectal, nigrothalamic and nigrostriatal projections in the rat. Neuroscience 3:989–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fennema‐Notestine C, Archibald SL, Jacobson MW, Corey‐Bloom J, Paulsen JS, Peavy GM et al (2004) In vivo evidence of cerebellar atrophy and cerebral white matter loss in Huntington disease. Neurology 63:989–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fink‐Jensen A, Mikkelsen JD (1991) A direct neuronal projection from the entopeduncular nucleus to the globus pallidus. A PHA‐L anterograde tracing study in the rat. Brain Res 542:175–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Flaherty AW, Graybiel AM (1994) Anatomy of the basal ganglia. In: Movement Disorders. Marsden CD, Fahn S (eds), pp. 3–27. Butterworths: London. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fortin M, Parent A (1994) Calretinin labels a specific neuronal subpopulation in primate globus pallidus. Neuroreport 5:2097–2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fox CA, Andrade AM, LuQui IJ, Rafols JA (1974) The primate globus pallidus: a Golgi and electron microscopic study. J Hirnforsch 15:75–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. François C, Percheron G, Yelnik J, Heyner S (1984) A Golgi analysis of the primate globus pallidus. I. Inconstant processes of large neurons. Other neuronal types, afferent axons. J Comp Neurol 227:182–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gerfen CR (1992) The neostriatal mosaic: multiple levels of compartmental organization in the basal ganglia. Annu Rev Neurosci 15:285–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gerfen CR, Engber TM, Mahan LC, Susel Z, Chase TN, Monsma FJ Jr et al (1990), D1 and D2 dopamine receptor‐regulated gene expression of striatonigral and striatopallidal neurons. Science (New York, NY) 250:1429–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gerfen CR, Wilson CJ (1996) The basal ganglia. In: Integrated Systems of the CNS, Part III. Swanson LW, Björklund A, Hökfelt T (eds), pp. 371–468. Elsevier: Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Glass M, Dragunow M, Faull RL (2000) The pattern of neurodegeneration in Huntington's disease: a comparative study of cannabinoid, dopamine, adenosine and GABA(A) receptor alterations in the human basal ganglia in Huntington's disease. Neuroscience 97:505–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Goldberg J, Bergman H (2011) Computational physiology of the neural networks of the primate globus pallidus: function and dysfunction. Neuroscience 198:171–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Graybiel AM (1986) Neuropeptides in the basal ganglia. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis 64:135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Graybiel AM, Penney JB (1999) Chemical architecture of the basal ganglia. In: The Primate Nervous System, Part III, Vol. 15. Bloom FE, Björklund A, Hokfelt T (eds), pp. 227–284. Elsevier: Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Haber SN, Elde R (1981) Correlation between Met‐enkephalin and substance P immunoreactivity in the primate globus pallidus. Neuroscience 6:1291–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Haber SN, Knutson B (2010) The reward circuit: linking primate anatomy and human imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology 35:4–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Haber SN, Lynd E, Klein C, Groenewegen H (1990) Topographic organization of the ventral striatal efferent projections in the rhesus monkey: an anterograde tracing study. J Comp Neurol 293:282–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Haber SN, Lynd‐Balta E, Mitchell SJ (1993) The organization of the descending ventral pallidal projections in the monkey. J Comp Neurol 329:111–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Haber SN, Nauta WJH (1983) Ramifications of the globus pallidus in the rat as indicated by patterns of immunohistochemistry. Neuroscience 9:245–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Haber SN, Watson SJ (1985) The comparative distribution of enkephalin, dynorphin and substance P in the human globus pallidus and basal forebrain. Neuroscience 14:1011–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Haber SN, Wolfe DP, Groenewegen HJ (1990) The relationship between ventral striatal efferent fibers and the distribution of peptide‐positive woolly fibers in the forebrain of the rhesus monkey. Neuroscience 39:323–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Halliday GM, McRitchie DA, Macdonald V, Double KL, Trent RJ, McCusker E (1998) Regional specificity of brain atrophy in Huntington's disease. Exp Neurol 154:663–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hazrati L‐N, Parent A, Mitchell S, Haber S (1990) Evidence for interconnections between the two segments of the globus pallidus in primates: a PHA‐L anterograde tracing study. Brain Res 533:171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hedreen JC, Folstein SE (1995) Early loss of neostriatal striosome neurons in Huntington's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 54:105–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Heimer L (1978)The olfactory cortex and the ventral striatum. In: Limbic Mechanisms. Livingston KE, Hornykiewicz O (eds), pp. 95–187. Plenum Press: New York. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Heimer L, Switzer TD, Van Hoesen GW (1982) Ventral striatum and ventral pallidum. Component of the motor system? Trends Neurosci 5:83–87. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Heimer L, Van Hoesen GW, Trimble M, Zahm DS (2008) The Anatomy of the basal forebrain. In: Anatomy of Neuropsychiatry: The New Anatomy of the Basal Forebrain and its Implications for Neuropsychiatric Illness. pp. 27–67. Academic Press: San Diego. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/book/9780123742391 [Google Scholar]

- 58. Heimer L, Wilson RD ( 1975) The subcortical projections of the allocortex: similarities in the neural associations of the hippocampus, the piriform cortex, and the neocortex. In: Golgi Centennial Symposium. Santini M (ed), pp. 177–193. Raven Press: New York. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Heimer L,D, Olmos JS, Alheid GF, Pearson J, Sakamoto N, Shinoda K et al (1999) The human basal forebrain. II. In: Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy. Vol. 15: The Primate Nervous System Part III. Bloom FE, Björklund A, Hokfelt T (eds), pp. 57–226. Elsevier: Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jaeger D, Kita H (2011) Functional connectivity and integrative properties of globus pallidus neurons. Neuroscience 198:44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jessel TM, Emson PC, Paxinos G, Cuello AC (1978) Topographic projections of substance P and GABA pathways in the striato‐and pallido‐nigral system: a biochemical and immunohistochemical study. Brain Res 152:487–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Joel D, Weiner I (1997) The connections of the primate subthalamic nucleus: indirect pathways and the open‐interconnected scheme of basal ganglia‐thalamocortical circuitry. Brain Res Rev 23:62–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Joyce JN, Lexow N, Bird E, Winokur A (1988) Organization of dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in human striatum: receptor autoradiographic studies in Huntington's disease and schizophrenia. Synapse 2:546–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kassubek J, Juengling FD, Kioschies T, Henkel K, Karitzky J, Kramer B et al (2004) Topography of cerebral atrophy in early Huntington's disease: a voxel based morphometric MRI study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 75:213–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kawaguchi Y, Wilson CJ, Emson PC (1990) Projection subtypes of rat neostriatal matrix cells revealed by intracellular injection of biocytin. J Neurosci 10:3421–3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kayahara T, Nakano K (1996) Pallido‐thalamo‐motor cortical connections: an electron microscopic study in the macaque monkey. Brain Res 706:337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Khan ZU, Gutiérrez A, Martín R, Peñafiel A, Rivera A, De La Calle A (1998) Differential regional and cellular distribution of dopamine D2‐like receptors: an immunocytochemical study of subtype‐specific antibodies in rat and human brain. J Comp Neurol 402:353–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kim R, Nakano K, Jayaraman A, Carpenter MB (1976) Projections of the globus pallidus and adjacent structures: an autoradiographic study in the monkey. J Comp Neurol 169:263–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kita H (1994) Parvalbumin‐immunopositive neurons in rat globus pallidus: a light and electron microscopic study. Brain Res 657:31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kita H (2007) Globus pallidus external segment. Prog Brain Res 160:111–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kita H, Kitai ST (1987) Efferent projections of the subthalamic nucleus in the rat: light and electron microscopic analysis with the PHA‐L method. J Comp Neurol 260:435–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kita H, Kitai ST (1994) The morphology of globus pallidus projection neurons in the rat: an intracellular staining study. Brain Res 636:308–319. Feb 14; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kita H, Tokuno H, Nambu A (1999) Monkey globus pallidus external segment neurons projecting to the neostriatum. Neuroreport 10:1467–1472. May 14; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Klitenick MA, Deutch AY, Churchill L, Kalivas PW (1992) Topography and functional role of dopaminergic projections from the ventral mesencephalic tegmentum to the ventral pallidum. Neuroscience 50:371–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kobayashi Y, Okada KI (2007) Reward prediction error computation in the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus neurons. Ann NY Acad Sci 1104:1310–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kuo JS, Carpenter MB (1973) Organization of pallidothalamic projections in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol 151:201–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lange H, Thorner G, Hopf A, Schroder KF (1976) Morphometric studies of the neuropathological changes in choreatic diseases. J Neurol Sci 28:401–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lavoie B, Parent A (1990) Immunohistochemical study of the serotoninergic innervation of the basal ganglia in the squirrel monkey. J Comp Neurol 299:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lavoie B, Parent A (1994) Pedunculopontine nucleus in the squirrel monkey: projections to the basal ganglia as revealed by anterograde tract‐tracing methods. J Comp Neurol 344:210–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lavoie B, Smith Y, Parent A (1989) Dopaminergic innervation of the basal ganglia in the squirrel monkey as revealed by tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemistry. J Comp Neurol 289:36–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Mai JK, Stephens PH, Hopf A, Cuello AC (1986) Substance P in the human brain. Neuroscience 17:709–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Maneuf YP, Mitchell IJ, Crossman AR, Brotchie JM (1994) On the role of enkephalin cotransmission in the GABAergic striatal efferents to the globus pallidus. Exp Neurol 125:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Marshall PE, Landis D, Zalneraitis EL (1983) Immunocytochemical studies of substance P and leucine‐enkephalin in Huntington's disease. Brain Res 289:11–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O (2007) Lateral habenula as a source of negative reward signals in dopamine neurons. Nature 447:1111–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Mehler WR (1971) Idea of a new anatomy of the thalamus. J Psychiatric Res 8:203–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Miller J, Vorel S, Tranguch A, Kenny E, Mazzoni P, van Gorp W et al, (2006) Anhedonia after a selective bilateral lesion of the globus pallidus. Am J Psychiatry 163:786–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mitrovic I, Napier TC (2002) Mu and kappa opioid agonists modulate ventral tegmental area input to the ventral pallidum. Eur J Neurosci 15:257–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Mogenson GJ, Yang CR (1991) The contribution of basal forebrain to limbic‐motor integration and the mediation of motivation to action. In: The Basal Forebrain: Anatomy to Function, Napier TC, Kalivas PW, Hanin I (eds), pp. 267–290. Springer: Boston. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Morissette M‐C, Boye SM (2008) Electrolytic lesions of the habenula attenuate brain stimulation reward. Behav Brain Res 187:17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Nambu A (2007) Globus pallidus internal segment. Prog Brain Res 160:135–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Napier TC, Muench MB, Maslowski RJ, Battaglia G ( 1991) Is dopamine a neurotransmitter within the ventral pallidum/substantia innominata? In: The Basal Forebrain: Anatomy to Function, Napier TC, Kalivas PW, Hanin I (eds), pp. 183–195. Springer: Boston. [Google Scholar]

- 92. Nauta WJH. and Domesick VB (1984) Afferent and Efferent Relationships of the Basal Ganglia. In: Ciba Foundation Symposium 107 - Functions of the Basal Ganglia, Evered D, and O'Connor M (eds), John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Chichester, UK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Nauta WJH, Mehler WR (1966) Projections of the lentiform nucleus in the monkey. Brain Res 1:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Nieuwenhuys R, Voogd J, van Huijzen C ( 2008) Telencephalon: basal ganglia. In: The Human Central Nervous System, 4th edn, pp. 427–489. Springer: Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Oertel W, Mugnaini E (1984) Immunocytochemical studies of GABAergic neurons in rat basal ganglia and their relations to other neuronal systems. Neurosci Lett 47:233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Oertel W, Nitsch C, Mugnaini E (1983) Immunocytochemical demonstration of the GABA‐ergic neurons in rat globus pallidus and nucleus entopeduncularis and their GABA‐ergic innervation. Adv Neurol 40:91–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Öngür D, Price JL (2000) The organization of networks within the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex of rats, monkeys and humans. Cerebral Cortex 10:206–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Parent A, Charara A, Pinault D (1995) Single striatofugal axons arborizing in both pallidal segments and in the substantia nigra in primates. Brain Res 698:280–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Parent A, De Bellefeuille L (1983) The pallidointralaminar and pallidonigral projections in primate as studied by retrograde double‐labeling method. Brain Res 278:111–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Parent A, Gravel S, Boucher R (1981) The origin of forebrain afferents to the habenula in rat, cat and monkey. Brain Res Bull 6:23–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Parent A, Hazrati LN (1993) Anatomical aspects of information processing in primate basal ganglia. Trends Neurosci 16:111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Parent A, Hazrati LN (1995) Functional anatomy of the basal ganglia. II. The place of subthalamic nucleus and external pallidum in basal ganglia circuitry. Brain Res Rev 20:128–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Parent M, Levesque M, Parent A (1999) The pallidofugal projection system in primates: evidence for neurons branching ipsilaterally and contralaterally to the thalamus and brainstem. J Chem Neuroanat 16:153–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Penney JB, Young AB (1981) GABA as the pallidothalamic neurotransmitter: implications for basal ganglia function. Brain Res 207:195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Penney JB, Young AB (1982) Quantitative autoradiography of neurotransmitter receptors in Huntington disease. Neurology 32:1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Penney JB, Young AB (1986) Striatal inhomogeneities and basal ganglia function. Mov Disord 1:135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Percheron G, Yelnik J, Francois C (1984) A Golgi analysis of the primate globus pallidus. III. Spatial organization of the striato‐pallidal complex. J Comp Neurol 227:214–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Petrasch‐Parwez E, Habbes HW, Löbbecke‐Schumacher M, Saft C, Niescery J (2012) The amygdala—a discrete multitasking manager. The Ventral Striatopallidum and Extended Amygdala in Huntington Disease Ferry B, (ed). DOI: 10.5772/48520. Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/the-amygdala-a-discrete-multitasking-manager/the-ventral-striatopallidum-and-extended-amygdala-in-huntington-disease [Google Scholar]

- 109. Pirot S, Jay TM, Glowinski J, Thierry AM (1994) Anatomical and electrophysiological evidence for an excitatory amino acid pathway from the thalamic mediodorsal nucleus to the prefrontal cortex in the rat. Eur J Neurosci 6:1225–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Rauch SL, Shin LM, Dougherty DD, Alpert NM, Orr SP, Lasko M et al (1999) Neural activation during sexual and competitive arousal in healthy men. Psych Res 91:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Reiner A, Albin RL, Anderson KD, D'Amato CJ, Penney JB, Young AB (1988) Differential loss of striatal projection neurons in Huntington disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:5733–5737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Reiner A, Medina L, Haber SN (1999) The distribution of dynorphinergic terminals in striatal target regions in comparison to the distribution of substance P‐containing and enkephalinergic terminals in monkeys and humans. Neuroscience 88:775–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Roos RAC (1986) Neuropathology of Huntington's disease. In: Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol. 49, Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, Klawans HL (eds), pp. 315–326. New York: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- 114. Rosas HD, Koroshetz WJ, Chen YI, Skeuse C, Vangel M, Cudkowicz ME et al (2003) Evidence for more widespread cerebral pathology in early HD An MRI‐based morphometric analysis. Neurology 60:1615–1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Sapp E, Ge P, Aizawa H, Bird E, Penney J, Young AB et al (1995) Evidence for a preferential loss of enkephalin immunoreactivity in the external globus pallidus in low grade Huntington's disease using high resolution image analysis. Neuroscience 64:397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Sato F, Lavallee P, Levesque M, Parent A (2000) Single‐axon tracing study of neurons of the external segment of the globus pallidus in primate. J Comp Neurol 417:17–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Shink E, Smith Y (1995) Differential synaptic innervation of neurons in the internal and external segments of the globus pallidus by the GABA‐and glutamate‐containing terminals in the squirrel monkey. J Comp Neurol 358:119–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Smith KS, Berridge KC (2007) Opioid limbic circuit for reward: interaction between hedonic hotspots of nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum. J Neurosci 27:1594–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Smith KS, Tindell AJ, Aldridge JW, Berridge KC (2009) Ventral pallidum roles in reward and motivation. Behav Brain Res 196:155–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Smith Y, Bevan MD, Shink E, Bolam JP (1998) Microcircuitry of the direct and indirect pathways of the basal ganglia. Neuroscience 86:353–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Smith Y, Parent A, Seguela P, Descarries L (1987) Distibution of GABA‐immunoreactive neurons in the basal ganglia of the squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus). J Comp Neurol 259:50–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Smith Y, Shink E, Sidibe M (1998) Neuronal circuitry and synaptic connectivity of the basal ganglia. Neurosurg Clin N Am 9:203–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Smith Y, Wichmann T, DeLong M (1994) Synaptic innervation of neurons in the internal pallidal segment by the subthalamic nucleus and the external pallidum in monkeys. J Comp Neurol 343:297–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Spooren WP, Lynd‐Balta E, Mitchell S, Haber SN (1996) Ventral pallidostriatal pathway in the monkey: evidence for modulation of basal ganglia circuits. J Comp Neurol 370:295–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Storey E, Beal M (1993) Neurochemical substrate of rigidity and chorea in Huntington's disease. Brain 116:1201–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Surmeier DJ, Song WJ, Yan Z (1996) Coordinated expression of dopamine receptors in neostriatal medium spiny neurons. J Neurosci 16:6579–6591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Tindell AJ, Smith KS, Pecina S, Berridge KC, Aldridge JW (2006) Ventral pallidum firing codes hedonic reward: when a bad taste turns good. J Neurophysiol 96:2399–2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Turner MS, Lavin A, Grace AA, Napier TC (2001) Regulation of limbic information outflow by the subthalamic nucleus: excitatory amino acid projections to the ventral pallidum. J Neurosci 21:2820–2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Vijayaraghavan L, Vaidya JG, Humphreys CT, Beglinger LJ, Paradiso S (2008) Emotional and motivational changes after bilateral lesions of the globus pallidus. Neuropsychology 22:412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Vonsattel JP, DiFiglia M (1998) Huntington disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 57:369–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Vonsattel JP, Keller C, Amaya M (2008) Huntington's Disease. In: Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vol. 89. Duyckaerts C, Litvan I (eds), pp. 599–618. Elsevier: Amsterdam. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Vonsattel JP, Myers RH, Stevens TJ, Ferrante RJ, Bird ED, Richardson EP Jr (1985) Neuropathological classification of Huntington's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 44:559–577. Nov; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Wakai M, Takahashi A, Hashizume Y (1993) A histometrical study on the globus pallidus in Huntington's disease. J Neurol Sci 119:18–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Waldvogel HJ, Kubota Y, Fritschy J, Mohler H, Faull RL (1999) Regional and cellular localisation of GABA(A) receptor subunits in the human basal ganglia: an autoradiographic and immunohistochemical study. J Comp Neurol 415:313–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Waraczynski MA (2006) The central extended amygdala network as a proposed circuit underlying reward valuation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 30:472–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Whalen PJ, Rauch SL, Etcoff NL, McInerney SC, Lee MB, Jenike MA (1998) Masked presentations of emotional facial expressions modulate amygdala activity without explicit knowledge. J Neurosci 18:411–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Whitehouse PJ, Trifiletti RR, Jones BE, Folstein S, Price DL, Snyder SH et al (1985) Neurotransmitter receptor alterations in Huntington's disease: autoradiographic and homogenate studies with special reference to benzodiazepine receptor complexes. Ann Neurol 18:202–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Wilson CJ (2004) Basal ganglia. In: The Synaptic Organization of the Brain. Shepherd GM, (ed), pp. 361–413. Oxford University Press: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- 139. Wu Y, Richard S, Parent A (2000) The organization of the striatal output system: a single‐cell juxtacellular labeling study in the rat. Neurosci Res 38:49–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Yasukawa T, Kita T, Xue Y, Kita H (2004) Rat intralaminar thalamic nuclei projections to the globus pallidus: a biotinylated dextran amine anterograde tracing study. J Comp Neurol 471:153–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Yelnik J (2002) Functional anatomy of the basal ganglia. Mov Disord 17:S15–S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Yelnik J, Percheron G, Francois C (1984) A Golgi analysis of the primate globus pallidus. II. Quantitative morphology and spatial orientation of dendritic arborizations. J Comp Neurol 227:200–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Yeterian EH, Pandya DN (1991) Prefrontostriatal connections in relation to cortical architectonic organization in rhesus monkeys. J Comp Neurol 312:43–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Young AB, Greenamyre JT, Hollingsworth Z, Albin R, D'Amato C, Shoulson I et al (1988) NMDA receptor losses in putamen from patients with Huntington's disease. Science 241:981–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Zahm DS, Zaborszky L, Alheid GF, Heimer L (1987) The ventral striatopallidothalamic projection. II. The ventral pallidothalamic link. J Comp Neurol 255:592–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]