Clinical history and imaging studies

A 3‐year‐old boy was referred for pre‐surgical evaluation due to drug‐resistant complex partial seizures. The patient was born to unrelated healthy parents and had developed normally. There was no family history of any central nervous system (CNS) disease. His seizures started at the age of 4 months and were characterized by daily, brief (30–60 seconds) episodes of staring, gestural automatisms, and tachycardia, followed by somnolence or headache. From the age of 14 months he also started suffering from frequent left focal motor seizures often leading to generalized seizure. At the time of our observation, seizures still occurred daily despite treatment with several antiepileptic drugs. In addition, his parents had also noted initial worsening of cognitive function. Dermatologic evaluation revealed a large congenital nevus on the scalp (Fig 1a) and two small black pigmented nevi on gluteus and abdomen. Electroencephalographic recordings showed frequent slow and sharp waves over the right temporal region. Brain MRI showed a focal lesion in the right uncus. The lesion was hyperintense on T1‐weighted (fig 1b) and hypointense on T2‐weighted images with no gadolinium enhancement. No mass effect or surrounding edema was evident. A right anterior temporal lobectomy and hippocampectomy was performed (Figs 2a, 2b). Intraoperative electrocorticography before resection revealed active spikes around the lesion. The postoperative course was uneventful. After surgery, the boy remained seizure‐free at the 15‐months follow‐up.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Gross and microscopic pathology

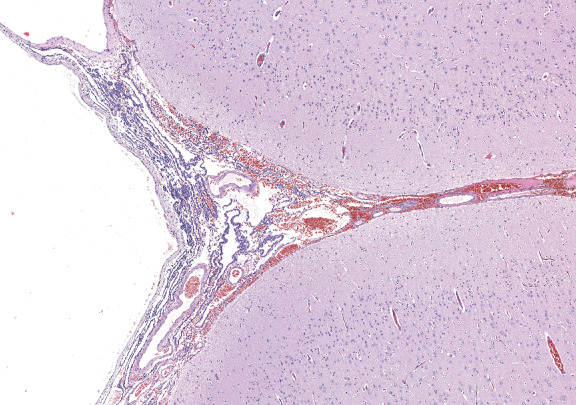

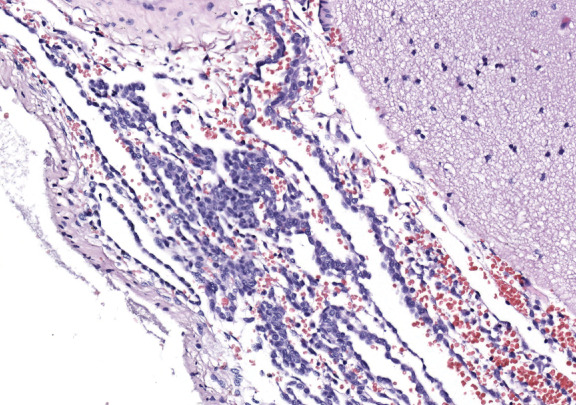

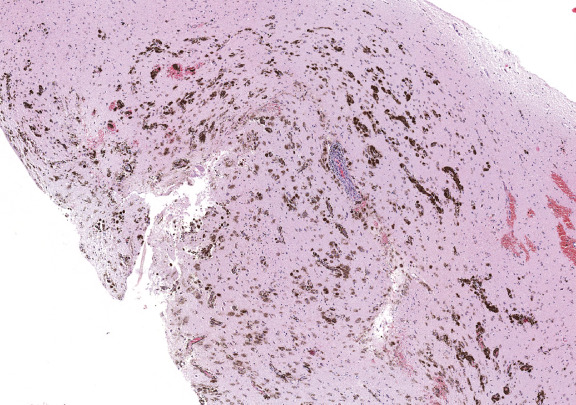

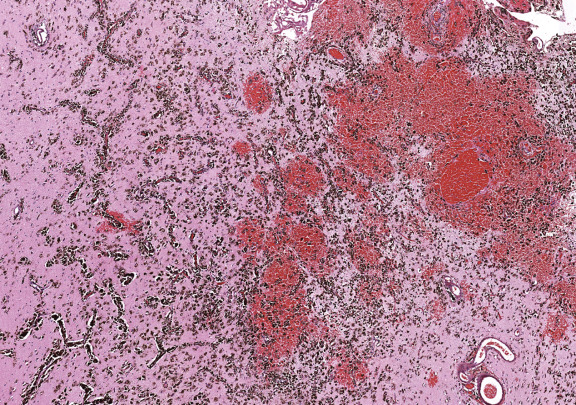

On gross inspection, the uncus was replaced by a grayish‐to‐black friable soft tissue without definite mass formation (Fig 2b). In the leptomeninges there were nests of melanin‐containing cells with round or oval nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figs 3, 4, 5, 6) heavily infiltrating the perivascular and Virchow‐Robin spaces. These cells and their nuclei were uniform in shape and size, showing no cellular or nuclear atypia. Mitoses were absent. The proliferative index was low. The cells resulted positive for antibodies against S100 protein and HMB45 but were unreactive for MAP2, GFAP, and epithelial membrane antigen. The temporal cortex was normal, as confirmed by the Neu‐N immunohistochemical staining. No dysmorphic neurons were observed.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

What is the diagnosis?

Diagnosis

Neurocutaneous melanosis.

Discussion

Neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM) is a nonfamilial congenital neurocutaneous syndrome characterized by melanocytic nevi and excessive proliferation of melanocytes within the CNS 5. This rare condition, estimated to occur in less than 1 in 20,000 newborns, is believed to be an embryologic defect in the migration of melanoblasts from the neural crest to the leptomeninges and the skin 5. Since its first description by Rokitansky in 1861 7, about 100 patients have been reported 6.

NCM can be associated with a large spectrum of neurologic symptoms, which vary with age 5, 6. The most common initial clinical signs and symptoms are related to increased intracranial pressure, including seizures (48%), vomiting (40%), headache (35%), cranial nerve palsies (26%, papilledema (10%), and meningeal signs (3%). Some children also develop signs of spinal cord and root involvement and myelopathy. Conversely, patients with later onset usually show localized sensorimotor deficits, difficulties with speech, or psychiatric symptoms 5, 6. CNS melanoma develops in about 50%.

The diagnosis of NCM should be strongly suspected in patients with large pigmented nevi or small multiple hairy dark nevi, usually over the neck, trunk, or the back 5. The main differential diagnosis is with metastatic melanoma of the skin with brain metastases, primary malignant leptomeningeal melanoma, benign melanotic neuroectodermal tumors, melanocytic nerve sheath tumor (nevus of Ota), and melanotic nevus of Scheiden 5, 6. Neuroimaging is of great importance for a correct diagnosis. In fact, as melanin pigment is inherently paramagnetic, the typical NCM lesions usually exhibit high intensity on T1‐weighted MR images and low intensity to isointensity on T2‐weighted images 2. This pattern of parenchymal melanosis is most evident and frequent at the uncus and adjacent temporal cortex.

Our patient had a clinical diagnosis of drug‐resistant temporal lobe epilepsy caused by histologically proven NCM. Such cases, are rarely reported in literature 1, 4, 8 and NCM should be therefore listed among the possible causes of chronic partial epilepsy. In this patient, the post‐surgery pathological study revealed that the lesion was composed of melanin‐containing polygonal cells arranged in solid alveolar or multiple lobular patterns. The histological and immunohistochemical features of the cells are consistent with those of melanocytes 3. The perivascular infiltrations of the Virchow‐Robin spaces of brain tissue with melanocytes are also a typical histological hallmark of NCM 5, 6. Although distinguishing between benign proliferative melanosis and invasive malignant melanoma can be difficult, a confirmation of benign noninvasive disease in our patient is supported by lack of necrosis, cellular atypia, or excessive mitotic activity. Furthermore, melanoma can be differentiated from melanocytosis by immunohistochemical labelling of proliferation‐associated antigens such as Ki‐67 (3, 6). Finally, the absence of dysmorphic neurons is consistent with the view that etiologically the lesion represents a developmental malformation involving neural crest–derived and neuroepithelial cells 6.

The prognosis of NCM is variable but usually poor, sometimes even in the absence of malignancy. More than 50% of patients die within 3 years after the neurologic presentation, generally due to increased intracranial pressure. In particular, the association of Dandy‐Walker syndrome has an extremely bleak prognosis 5, 6. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy have little effect on the disease course in case of malignant leptomeningeal involvement. The efficacy of prophylactic resection of dermal lesions to reduce the risk of malignancy is uncertain 6. Our patient showed surgically successful removal of the epileptogenic lesion, confirming that resection should be seriously considered for treatment of this type of lesion.

Abstract

Neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM) is a rare, nonfamilial congenital neurocutaneous syndrome characterized by melanocytic nevi and excessive proliferation of melanocytes within the central nervous system. We report the surgical pathological features of a lesion in the right temporal lobe in a 3‐year‐old boy with congenital pigmented nevi and complex partial seizures. Brain MRI showed a focal lesion in the right uncus. The lesion was hyperintense on T1‐weighted and hypointense on T2‐weighted images with no gadolinium enhancement. A right anterior temporal lobectomy and hippocampectomy was performed. Post‐surgery pathological study revealed the histological and immunohistochemical features of NCM. At the postoperative follow‐up the boy remained seizure‐free. This case confirms that NCM should be listed among the possible causes of chronic drug‐resistant partial epilepsy. Surgical resection should be considered for treatment of this type of lesion.

References

- 1. Andermann F (2005) Neurocutaneous melanosis and epilepsy surgery. Epileptic Disord 7:57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barkovich AJ, Frieden I, Williams M (1994) MR of neurocutaneous melanosis. Am J Neuroradiol 15:859–867. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen Y, Deng W, Zhu H, Li J, Xu Y, Dai X, Jia C, Kong Q, Huang L, Liu Y, Ma C, Xiao C, Liu Y, Li Q, Bezard E, Qin C (2009) The pathologic features of neurocutaneous melanosis in a cynomolgus macaque. Vet Pathol 46:773–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fu YJ, Morota N, Nakagawa A, Takahashi H, Kakita A (2010) Neurocutaneous melanosis: surgical pathological features of an apparently hamartomatous lesion in the amygdala. J Neurosurg Pediatr 6:82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kadonaga JN, Frieden IJ (1991) Neurocutaneous melanosis: definition and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 24:747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pavlidou E, Hagel C, Papavasilliou A, Giouroukos S, Panteliadis C (2008) Neurocutaneous melanosis: report of three cases and up‐to‐date review. J Child Neurol 23:1382–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rokitanski J (1861) Ein ausgezeichneter Fall von Pigment‐Mal mit ausgebreiteter Pigmentierung der inneren Hirn‐ und Rü chenmarkhaute. Ally Wien Med Z 6:113–116. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ye BS, Cho YJ, Jang SH, Lee BI, Heo K, Jung HH, Chang JW, Kim SH (2008) Neurocutaneous melanosis presenting as chronic partial epilepsy. J Clin Neurol 4:134–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]