Abstract

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases are major risk factors in the development of cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease (AD). These cardio‐cerebral disorders promote a variety of vascular risk factors which in the presence of advancing age are prone to markedly reduce cerebral perfusion and create a neuronal energy crisis. Long‐term hypoperfusion of the brain evolves mainly from cardiac structural pathology and brain vascular insufficiency. Brain hypoperfusion in the elderly is strongly associated with the development of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and both conditions are presumed to be precursors of Alzheimer dementia. A therapeutic target to prevent or treat MCI and consequently reduce the incidence of AD aims to elevate cerebral perfusion using novel pharmacological agents. As reviewed here, the experimental pharmaca include the use of Rho kinase inhibitors, neurometabolic energy boosters, sirtuins and vascular growth factors. In addition, a compelling new technique in laser medicine called photobiomodulation is reviewed. Photobiomodulation is based on the use of low level laser therapy to stimulate mitochondrial energy production non‐invasively in nerve cells. The use of novel pharmaca and photobiomodulation may become important tools in the treatment or prevention of cognitive decline that can lead to dementia.

Keywords: Alzheimer's, mild cognitive impairment, photobiomodulation, brain hypoperfusion, cerebral blood flow, neuronal energy crisis, ROCK inhibitors, Sirtuins, DMSO

Introduction

The vascular hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease (AD) is based on the concept that chronic cerebral hypoperfusion can lead to neurodegenerative changes, including the formation of senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain 27, 36, 37. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion develops mainly in the elderly population as the heart and its arteries progressively age structurally and functionally. These mechano‐functional abnormalities can lower the heart's ability to deliver the energy fuel necessary to meet the metabolic demands of brain cells, thus contributing to their potential death 9, 30, 68, 148. It would seem that during advanced aging, the heart can continue to be a good friend to the brain or become its insidious foe.

Follow‐up studies of the “low supply:high demand” concept provided an important step toward our understanding of AD. This was achieved in the late 1990s when it became apparent that some vascular factors affecting cerebral perfusion could promote the development of cognitive impairment and promote Alzheimer dementia in elderly individuals 23, 24, 45, 65, 115, 143, 153.

Since then, vascular risk factors to AD have received a great deal of attention, particularly in the last decade. The reason is that vascular factors have emerged as therapeutic targets that can be treated to slowdown, prevent or reverse the pathways leading to AD 34, 66, 88, 123. Vascular risk factors to AD can also be considered markers of dementia because they promote chronic brain hypoperfusion, a suspected precursor of Alzheimer dementia. For example, neuroimaging studies indicate that cerebral hypoperfusion in the medio‐temporal area, posterior cingulate gyrus, precuneus and the associative frontotemporal‐parietal cortices and areas prone to AD pathology can generally predict severe cognitive decline transitioning mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to AD.

Many studies have shown the importance of a single vascular risk factor during advanced aging in the development of cognitive decline, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, atherosclerosis, assorted cardiovascular disorders and diabetes type 2 26, 88, 165, but multiple vascular risk factors often co‐exist which can incrementally increase the vascular burden on the brain and hasten the development of cognitive impairment and the onset of AD 6, 55, 64.

Vascular risk factors to AD during aging should refer exclusively to those conditions that create a burden to cerebral blood flow (CBF) and which are capable of accelerating or promoting cognitive impairment and Alzheimer dementia. This conclusion is supported by evidence that up to 90% of patients with AD show signs of cerebral hypoperfusion together with pathological features of amyloid angiopathy 126.

In the absence of vascular risk factors to AD, it is doubtful that advanced aging alone can accelerate or promote either cognitive decline, neurodegeneration or dementia. However, this conclusion has not been rigorously examined. Curiously, some nonagenarians and centenarians (the oldest‐old) remain cognitively normal despite the presence of high levels of brain amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles or other neuropathological features of AD seen at post‐mortem 22, 49, 75.

Cognitive Reserve

Some authors 160 have suggested that “cognitive reserve” in the elderly offers some degree of protection from age‐related neuropathology, but there is no evidence that cognitive reserve even exists. We have long maintained that what seems to be important in the resilience of the brain to mildly protect against age‐related wear and tear damage 28 is not the degree of higher education, innate intelligence or occupational attainment but the ability to engage in vigorous mental activities that can induce a boost in CBF 1, 136 These mental activities are more likely to be used by people with higher education, intellectual achievement and professional attainment but are not exclusive to this group. Excluding the APOE4 genotype from the formula 162, a low‐educated or unskilled worker with intellectual curiosity can engage in critical thinking and achieve the same degree of protection from age‐related cognitive decline. This is demonstrated by a recent study by Wilson and colleagues 167 who recruited over 1000 cognitively normal elderly individuals with a mean age of 80 years and diverse levels of education and professional attainments. It was found after a 5‐year follow‐up that those individuals who engaged in sustained, mentally stimulating activities such as playing chess, reading newspapers and visiting a library, predicted better cognitive function than those who did not engage in such mental activities.

We speculate that all things being equal, an uneducated but mentally active individual has the same opportunity of lessening the risk of AD as a graduate from Oxford.

This disparity between higher and lower education and relative risk to AD has nevertheless baffled scientists who have offered various theories, including cognitive reserve, to explain the phenomenon. However, one clue that may help explain the high‐low education‐AD risk ambiguity is the generally accepted correlation between neurovascular coupling and cognitive function. Consequently, an increase in metabolic demand, such as critical thinking requires an increase in brain blood flow 145, 146, 149. Following this reasoning, studies have shown that mental activity requiring certain types of thinking can increase oxidative metabolism and regional CBF in multiple cortical and subcortical fields including the hippocampus, one of the initial sites of AD pathology 135.

The resultant average increase in CBF following mental reasoning activities appears to be modest, about 10% from baseline 135, and may be short‐lived 95. But if performed on a routine basis, it may explain what is believed to be cognitive reserve in some individuals who engage in such mental activities.

When Cerebral Blood Flow Drops

Between the ages of 20–65, normal CBF generally declines about 15%–20% 84, 117, 151, 152. This gradual CBF drop in the aging brain occurs well before the onset of dementia and is considered a pattern of normal aging. However, if a further drop in CBF occurs during normal aging, possibly resulting from vascular risk factors, brain cell survival in regions associated with cognitive function are destined to be compromised 25, 78, 118.

Older individuals and the oldest‐old share this normal but progressive cerebral blood flow decline 90, 151. But if brain blood flow declines too steeply, a critically attained threshold of cerebral hypoperfusion (CATCH) ensues creating a neuronal energy crisis that threatens brain cell survival 25. As a progressive cerebrovascular insufficiency, CATCH will destabilize neurons, synapses, neurotransmission and cognitive function, eventually evolving into a severe neurodegenerative process characterized by the increased formation of amyloid beta‐containing plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid angiopathy and neurodegeneration 38.

If, in our judgment, elderly individuals can buffer the age‐related CBF drop with mental or cardiac activities, a grace period sparing them temporarily from cognitive decline may result, unlike their less mentally active counterparts.

Advanced age in the presence of a vascular risk factor or multiple vascular risk factors, is, in this author's view, a determinant and precursor of Alzheimer dementia by virtue of the resultant cerebral hypoperfusion, brain cell hypometabolism and neuronal energy crisis created by the key mediators, age and brain blood flow.

The question has been asked many times. Can anything be done to slow down the number of new AD cases expected to rise in the next few decades? The answer is, a tentative yes.

Because virtually all risk factors to AD described thus far can lower CBF to critical levels, this review will discuss possible interventions aimed at the two major accomplices that contribute to cerebral hypoperfusion, the heart and the brain.

Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Interventions

Hypertension

It is well documented that high blood pressure can increase the risk of stroke and cardiovascular disease and that the presence of these conditions can lead to cognitive impairment (see review in Ref. 69). Late‐life hypertension has also been linked to AD especially in those not treated for high blood pressure during midlife 50, 61, 120, 144.

High blood pressure is known to reduce CBF but the exact mechanism(s) involved in this action have not been clarified 85. Because cardiac output remains normal even when CBF is reduced during high blood pressure 128, two possible causes for the cerebral blood flow reduction may occur in hypertensive individuals. First, hypertension can increase systemic vascular resistance to slow down normal CBF. Second, CBF may fall when blood pressure rises caused by direct damage to brain endothelial cells that produce the vasodilator nitric oxide 128.

Damage from high blood pressure to brain endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells that control vascular tone is suspected to be a culprit of cognitive impairment caused by the pulsatile pressure changes generated on the cerebral microvasculature from hypertension 114. Endothelial damage is a crucial step in the evolution of atherosclerosis and precedes clinical symptoms of disease 163, 164. Endothelial cell dysfunction is commonly associated with an increased production of the vasoconstrictors thromboxane A2, prostaglandin H2, 20‐HETE and superoxide anion in cerebral resistance arteries and is an early marker of extracerebral atherosclerosis 19.

As critically less blood flow reaches the brain microcirculation from hemodynamic disturbances, neurons associated with cognitive function will likely engage in suboptimal neurotransmission, thus negatively affecting cognitive behavior 92. Aside from contributing to systolic hypertension, the association involving arterial stiffness and high pulse waves can be considered to be a targets of therapeutic opportunity to prevent or treat cognitive impairment during advanced aging 138.

At present, there is an important focus in developing drugs that target the 20‐HETE pathway for the treatment of hypertension, with the well‐established evidence that CYP4F2 mutation is associated with increased 20‐HETE urinary excretion and systolic hypertension 3.

A number of highly selective inhibitors of 20‐HETE such as 17‐ODYA (17‐octadecynoic acid), HET0016 (N‐hydroxy‐N′‐(4‐butyl‐2methylphenyl)formamidine) and TS011 (N‐(3‐Chloro‐4‐morpholin‐4‐yl)Phenyl‐N′‐hydroxyimido formamide) have been shown to be potential targets for hypertension and as safeguards of endothelial cell damage 102, 111, 170. Inhibitors of 20‐HETE show promise as regulators of hypertension‐related cognitive impairment and protectors of vascular pathology.

Disturbance of the intracellular calcium homeostasis is a key feature in the pathophysiology of neurodegeneration. Amlodipine, a long‐acting calcium channel inhibitor, is reported to improve endothelial function in patients with essential hypertension 63. This action is achieved by amlodipine's ability to relax arterial smooth muscle cells thereby reducing peripheral vascular resistance. Another calcium channel blocker, nilvadipine, is presently undergoing a phase III clinical trial in Europe and Scandinavia to treat mild to moderate AD 104.

There is mounting evidence that the renin‐angiotensin system (RAS) may have a crucial role in cognitive impairment, including learning and memory function. The main role of RAS is to regulate blood pressure. It does this by releasing the hormone renin into the blood stream where it is converted to angiotensin I and from there, it changes to the more powerful angiotensin II via the enzyme angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE).

To take advantage of controlling high blood pressure and its damaging cognitive consequences, perindopril, a centrally acting ACE inhibitor, is reported to block hippocampal ACE and prevent cognitive impairment in mouse models of AD 48, 156. Perindopril has also been shown to have a favorable outcome on the rate of decline in patients with AD, especially when compared with calcium channel blockers used for hypertension 142. ACE inhibitors that act centrally have been shown to improve activities of daily living in Alzheimer patients 107.

Medications to control high blood pressure during advanced aging, particularly calcium channel blockers and centrally acting ACE inhibitors may have a protective role in slowing down cognitive decline but the evidence remains far from clear caused by the difficulty of assessing their effects on a heterogenous population in adequately powered, randomized controlled clinical trials 108.

Hypotension

As the pendulum swings back from drugs treating hypertension during advanced aging, the paradoxical phenomenon of inducing hypotension and low diastolic blood pressure becomes a real possibility that may usher an increased risk of AD. Thus, diastolic pressures of <65 mm Hg appear to be associated with a greater chance of developing AD 124.

How is hypotension associated with an increased risk of AD remains unclear but suggestions have centered on poorer cerebral perfusion when compared to individuals with diastoloic pressures of 66–90 mm Hg 124. Untreated hypertension and hypotension have been shown in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, to be associated with lower performance in older individuals on tests measuring executive function, perceptuomotor speed and confrontation 164.

Hypotension can result from blood pressure anomalies, dehydration, bleeding, medications, cardiac pathology, including carotid sinus and vasovagal syndromes. Iatrogenic‐induced hypotension is known to occur when normotensive patients with white coat hypertension are treated aggressively by physicians who are not familiar with this phenomenon 53. These patients can exhibit false elevation of blood pressure when exposed to a clinical setting.

All the abnormalities related to hypotension mentioned above can be controlled with appropriate intervention. However, hypotension should not be treated unless it is low enough to cause undesirable symptoms. Hypotensive symptoms may include lightheadedness, chest pain, reflex tachycardia, weakness, syncope, coldness of extremities and difficulty thinking, especially in the elderly. Many of these symptoms derive from brain hypoperfusion or low cardiac output. Therapies primarily consist of a combination of vasoconstrictor drugs (midodrine, fludrocortisone), isometric exercise, volume expansion by ingesting extra fluid and salt, compression garments and postural adjustment.

Atrial Fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a heart rhythm disorder (arrhythmia) generally involving a rapid heart rate. The rate of ventricular contraction in the normal heart is the same as the rate of atrial contraction. In atrial fibrillation, however, the rate of ventricular contraction is less than the rate of atrial contraction. Diagnosis of AF can be usually made with 12 lead electrocardiogram 86. The risk of AF is more common in males and increases with age 89.

AF is classified into three types. Paroxysmal AF can last a few minutes to several hours or days before it stops on its own. Persistent AF occurs longer than a week and may stop on its own or by treatment, usually electrical cardioversion. Permanent AF occurs when normal heart rhythm cannot be restored with treatment.

One major risk for dementia and disability after AF is stroke. Novel oral anticoagulants have come into common practice to reduce the risk of non‐valvular related stroke in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF. These new anticoagulants are direct thrombin blockers and include factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban 97.

One procedure that may eliminate the use of anticoagulants and their potential side effects of increased bleeding is left atrial appendage closure. The left atrial appendage is an ear‐shaped sac in the muscle wall of the left atrium where blood clots can form in AF patients. When these blood clots are pumped out of the heart, they can cause a stroke. The technique for closure of the left atrial appendage can now be performed non‐surgically with devices that can be inserted percutaneously to the heart through special catheters 97.

Besides stroke, patients with AF have an increased long‐term risk of heart failure, cerebral hypoperfusion, cognitive impairment and Alzheimer dementia 46, 72, 76.

Not surprisingly, studies have shown an association between atrial fibrillation and diminished cognitive function leading to AD even in the absence of stroke, hypertension or diabetes 2 72, 76.

When cerebrovascular events were examined in a population‐based study, the risk of AD after AF appeared to be stronger than for vascular dementia 116. A more recent prospective study of 37,000 patients with a mean average age of 60 showed a significant increase in cognitive impairment incidence during a 5‐year follow‐up period 14.

Atrial fibrillation also appears to involve a significant conversion to dementia in nondemented subjects whether or not cognitive impairment was present 54, 119. Many studies have shown that atrial fibrillation induces significant brain hypoperfusion 58 which can compromise the aging cerebrovasculature. Although the true mechanism that associates AF to cognitive impairment is unclear, a suspicion is that cerebral hypoperfusion may be triggered by the chronic arrhythmia that is present 51.

If persistent AF becomes refractory to medication or electrical cardioversion, a surgical technique called pulmonary vein ablation can be considered. This procedure involves many different variations and anatomic approaches but commonly relies on introducing a catheter with an electrode tip threaded to the heart atrium from the groin or the internal jugular vein and destroying by freezing or heating, the venous or heart tissue that is the source of electrical irritability causing AF 127.

Catheter ablation for persistent AF is a relatively safe procedure and is reputed to have a 95% success rate patients experiencing significant improvement of their AF over a 6‐year period 169.

Pulmonary vein ablation for intractable AF has not been examined with respect to preventing cognitive impairment and AD onset in patients. This would be an important study to undertake and an excellent reason to consider the ablation procedure. However, because AF can generate brain hypoperfusion and AD onset, a randomized controlled trial should be organized to investigate the potential of this procedure to control AF, improve quality of life and slow down or prevent cognitive decline.

Aortic and Mitral Valve Pathology

In 2006, this author suggested that aortic and mitral valve damage could contribute to cognitive impairment leading to AD 29. Since then, it has been reported that patients with AD undergoing echocardiography are more likely to have aortic valve thickening, aortic valve regurgitation, left ventricular wall motion abnormalities, left ventricular hypertrophy, reduced ejection fraction 129, features that will result in chronic brain hypoperfusion, a precursor of cognitive decline and untimely closure of the mitral valve.

In another echocardiographic study, it was found that patients with AD exhibit suboptimal transmitral flow efficiency during left ventricular diastolic filling 11. Suboptimal transmitral flow deficiency impairs normal formation of a vortex alongside a diastolic jet and can result in stagnation of blood within the left ventricular apex. These findings suggest that the lack of optimal hemodynamic diastolic filling efficiency could be partly responsible for the association between the pathological left ventricular relaxation and eventual cognitive dysfunction seen in some patients prior to AD 11. The echocardiographic studies are supported by autopsy examinations of AD patients which reveal that valvular pathology is a common finding in these patients 21.

A more recent report using echocardiography in patients with AD concluded that these patients are more likely to have diastolic dysfunction, higher atrial conduction times and increased arterial stiffness compared to same sex and age‐matched controls 16. The results of this study indicate that patients with AD have abnormal aortic stiffening caused by the more pronounced left ventricular relaxation dysfunction.

Aortic Stiffening in the Elderly

Evidence indicates that cognitive impairment can be induced when hemodynamic anomalies of the brain microvasculature are activated by aortic stiffness 157. The damage to brain microvessels from aortic stiffening would occur as follows. The aorta is known to be a reservoir of pulsatile energy delivered by left ventricular ejection during systole and discharges that energy during diastole. Because the aorta is normally more distensible than the stiffer carotid arteries, it can absorb the ventricular ejection and dampen pulsatile flow into the distal vasculature. This hemodynamic phenomenon is called the Windkessel effect 52. The Windkessel effect acts to dampen excessive transmission of pulsatile flow that can damage the cerebral microvasculature and impair astrocyte signaling of neurons that control cerebral blood flow 33, 100.

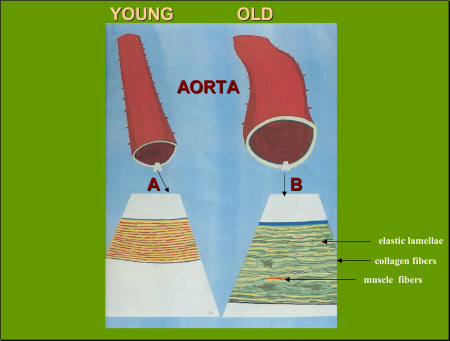

The normal proximal aorta thus reduces aortic‐carotid wave reflection, a physiologic event called impedance mismatch, which avoids excess transmission to the cerebral arterioles and capillaries. However, during aging, the presence of hypertension, inflammatory proteins or atherosclerosis, a loss of elastic lamellae which provide distensibility to the aorta occurs, markedly reducing aortic compliance with the net effect of increasing pulse pressure and systolic pressure while reducing diastolic pressure and wave reflection at the carotid arteries (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

When the aorta ages, structural remodeling occurs. This is observed in the enlarged insets (A and B) of the medial layer of the aortic wall which show normal, young aorta (inset A) and old aorta (inset B) where major changes in age‐related aortic stiffening is seen affecting the concentric musculoelastic layers called elastic lamella. The elastic lamellae (yellow) and muscle fibers (red) confer recoil and distensibility to the aorta but they undergo thinning and fraying during advanced aging, thus reducing aortic elasticity. Tensile strength is also impaired with increase of collagen fibers (black) in the aging aorta. These changes tend to increase systemic vascular resistance and blood pressure [adapted from de la Torre 171].

Collagen deposition also contributes to aortic stiffening 168. These hemodynamic abnormalities are worsened if vascular risk factors develop 33, 100. When this happens, exaggerated pulsatile flow or pulse wave velocity is transmitted to microvessels in the brain where white matter hyperintensities and damage to endothelial cells that participate in controlling cerebral blood flow will result 99.

This pathologic process suggests a mechanistic link between cerebral hypoperfusion and cognitive impairment whose primary trigger is loss of the Windkessel effect. Progressive increases of pulse wave velocity in elderly people are postulated to result in increasing cognitive decline and eventual AD 62.

Experimental findings suggest that arterial stiffness and increased pulse wave velocity during aging may occur from a mitochondrial disbalance between healthy production of mitochondria and degradation of damaged mitochondria, a process known as mitophagy 105. If mitophagy can be enhanced in age‐related arterial stiffening, it is speculated that the mitochondrial stress/dysfunction resulting from the disbalance between mitochondrial biogenesis and degradation could be reversed or managed 133.

Trehalose, a nutraceutical that enhances mitophagy, was reported to reverse age‐related arterial stiffening of the aorta and pulse wave velocity when given as a food supplement to old mice 101. This study inferred and supported the notion that mitochondrial stress/dysfunction during aging underlies age‐related aortic stiffening, possibly in the presence of oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines. Thus, trehalose and similar non‐reducing disaccharides, could lower free radical production and pulse wave velocity while normalizing the over‐produced aortic collagen I, a key contributor to age‐associated arterial stiffness 81, 83 (Figure 1). Downstream, trehalose also acts as an antioxidant and free radical scavenger 109.

Because trehalose is a natural sugar with no apparent serious side effects and can be assimilated much like sucrose, it would be of much interest if human studies could confirm its effect on mice, given that aortic stiffening and pulse wave velocity show marked improvement when rodents are fed trehalose. Improvement of aortic stiffening would be reflected by a slowing or prevention of cognitive decline.

Aortic stiffness has been classically treated with anti‐hypertensive medication. Long‐term trials have suggested that angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors are useful in markedly reducing pulse wave velocity and to a lesser extent, calcium channel blockers and beta blockers 112.

It seems a wise practice for elderly patients that are evaluated at cardiac clinics to look for signs of increased pulse wave velocity, a relatively simple office test and strong predictor of cardiovascular pathology and aortic stiffness. Because cardiovascular disease has been shown to be associated with cognitive impairment 125, 132, 139, 172, treating structural cardiopathic changes before they become refractory or spin out of control seems an advantageous strategy to prevent cognitive deterioration and potentially Alzheimer's disease.

Heart Failure

Heart failure is the most common reason for hospitalization among older adults 12, and moderate to severe cognitive impairment is a common finding in these patients 173. It is one of the fastest growing cardiovascular disorders caused by the rising elderly population and is estimated to affect 20% of people over age 80 47.

Heart failure can occur when the heart cannot adequately pump enough blood to meet the body's needs, including the brain. This pump failure is often caused by a dysfunctional left ventricular ejection fraction. The most common cause of heart failure occurs from stenosis of the coronary arteries which supply oxygen to the heart. Lack of oxygen to cardiac tissue results in tissue edema, shortness of breath, sleep apnea and muscular weakness.

Heart failure has been shown to be an important risk factor in the development of cognitive impairment affecting complex reasoning, memory, psychomotor speed and executive functions 121.

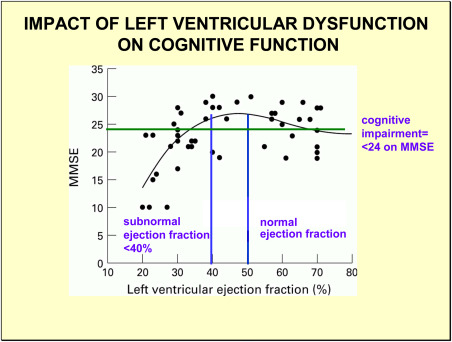

Heart failure is often associated with other comorbid vascular risk factors to AD including ischemic heart disease, hypertension and atrial fibrillation 122. Brain hypoperfusion is a common outcome of heart failure 174. As blood flow pumped out of the heart slows down, returning venous blood to the heart backs up, causing tissue edema particularly in the lungs. Zuccala and his colleagues 174 have reported that heart failure patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (low cardiac output) show an association with cognitive impairment (Figure 2). An ejection fraction less that 40% can confirm a diagnosis of heart failure.

Figure 2.

Each black circle represents a patient tested for cognitive impairment using mini‐mental state examination (MMSE) and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). An ejection fraction less than 40% is considered diagnostic of heart failure. The left lower quadrant on the figure shows a cluster of patients with subnormal ejection fraction and low MMSE. Right upper quadrant shows a cluster of patients with normal ejection fraction and normal MMSE. A smaller cluster of patients have low MMSE with normal LVEF (lower right quadrant) or normal MMSE with low LVEF (upper left quadrant). The plot supports the concept that low LVEF, a marker of poor blood flow to the brain, correlates with cognitive impairment (<24 MMSE). Adapted from Zuccala et al. 173.

A recent report by Alves and her colleagues 44 indicates that heart failure in elderly persons is associated with lowered cerebral blood flow in the posterior cingulate gyrus and the lateral temporoparietal cortex, regions that are linked to memory and visuospatial orientation. This finding is of interest because memory and visuospatial dysfunction are two of the earliest signs in imminent AD.

There is an urgent need to assess patients with heart failure and cardiovascular disease to prevent cognitive dysfunction because this co‐morbidity can affect the patient's ability to make appropriate self‐care decisions 17. For this purpose, we support the creation of transdisciplinary heart–brain clinics to identify and tailor‐treat patients with actual or risk of heart disease and cognitive impairment 35, 36.

Although CBF and cognitive function are reduced in heart failure, this syndrome can improve following implantation of a pacemaker in patients with bradycardia or from the use of selective cardiovascular agents 173. Clearly, aggressive treatment of heart failure to reverse brain hypoperfusion and the subsequent development of cognitive impairment could have a significant impact in reducing the incidence of AD in these patients.

Coronary Artery Disease

Over 380,000 deaths occur annually from coronary artery disease (CAD) making this malady one of the leading causes of mortality in the United States 57. There is no single cause of CAD which usually involves the buildup of cholesterol‐rich plaques called atheromas on the inside lining of the coronary arteries. The atheromas tend to thicken the arterial wall causing narrowing of the arterial space and reduced delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the cardiac tissue. The atheromas are made up of a chemical bouillabaisse that includes cholesterol, fatty compounds, inflammatory cells, calcium and fibrin.

Atheromas are the basis of atherosclerosis in coronary, peripheral or cerebral blood vessels. When an atheromatous plaque suddenly ruptures, platelets aggregate around it inducing intraluminal thrombosis or increased narrowing of the vessel, a condition that can result in myocardial infarction or stroke. The use of platelet deaggregators such as aspirin and clopidogrel or cilostazol, a phosphodiesterase type 3 inhibitor that can widen vessel lumen to increase blood flow is generally used to prevent stroke consequences such as neurologic disability and cognitive dysfunction. Stroke and CAD are known to reduce brain blood flow and potentially impair cognitive function, and both are reported to be vascular risk factors to AD 141, 150.

The risk to AD could stem primarily from atherosclerotic coronary vessels that damage cardiac endothelial cells and lower the heart's pumping ability to optimally perfuse the brain. This thinking is supported by the presence of high levels of cholesterol, low density lipoprotein and triglycerides found in the blood of probable AD subjects 147.

A number of studies are now in progress testing whether cholesterol homeostasis and lipoprotein disturbances using cholesterol‐lowering statins can alter AD pathology. However, the results of these studies are inconclusive and controversial with regard to the potential neuroprotective effects of statins 96. Another approach we and others have recommended is to pharmacologically increase endothelial nitric oxide, a powerful vasodilator with antithrombotic, anti‐ischemic and antiatherosclerotic activities 38.

The Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study (FINGER) is one of the few studies in the world investigating multi‐domain interventions in an older population that can prevent or slow‐down cognitive impairment. The plan is to target several specific vascular risk factors to AD, including cardiovascular disease 79.

Some of the diagnostic tools used in the FINGER study have been discussed here and elsewhere and include neuroimaging, neuropsychological testing, blood chemistry, echocardiography, ultrasound examination of the carotid artery and pulse wave velocity measurement 31, 79. FINGER is an ongoing study and its interventional findings may be available at the end of 2014.

Cerebrovascular Diseases

Cerebrovascular diseases refer to any pathology where an area of the brain is temporarily or permanently affected by bleeding or lack of blood flow.

Reduced blood flow to organs or tissue may occur from vessel narrowing (stenosis), clot formation (thrombosis), blockage (embolism) or blood vessel rupture (hemorrhage). Lack of sufficient blood flow affects brain tissue and may cause a stroke and cognitive decline. Stroke is a common cerebrovascular disorder and the second leading cause of death and disability in the world 154.

Two types of stroke are possible, ischemic and hemorrhagic. Ischemic strokes account for about 80% of all strokes and about 7% of deaths compared to 37% mortality for hemorrhagic strokes within the first 30 days 154.

A history of stroke or cerebrovascular disease is an important clinical finding because specific therapy may prevent further events and could be a clue for prevention or treatment to potential or actual cognitive impairment.

Cognitive deficits and dementia are not uncommon following an ischemic stroke. The reasons for the cognitive consequences after a stroke are not altogether clear but blockade or restricted blood flow to specific brain regions such as the hippocampus may contribute to the pathogenesis of post‐stroke cognitive impairment 155. It is estimated that 30% of stroke survivors develop cognitive deficits 131, often within 30 days following a stroke 106.

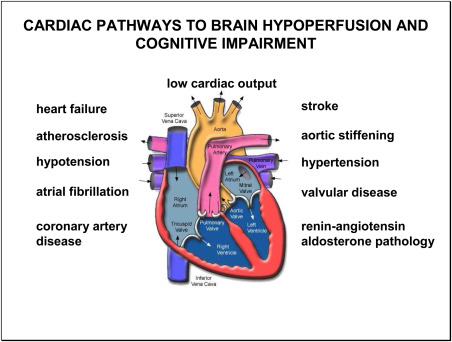

Prevention of ischemic stroke could significantly lower the incidence of cognitive impairment and dementia during advanced aging. The classic prevention schemes for stroke which have been discussed above, aim at the probable cause of this cerebral insult. These measures include management of hypertension, atrial fibrillation, valvular pathology, atherosclerosis and heart failure (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Structural and functional deficits of the elderly heart can negatively affect cognitive function and increase the risk of dementia. Two cardinal features of these deficits are (i) they reduce blood flow to the brain and (ii) they are associated with cognitive impairment (see text for details).

People either at risk or presenting these health issues can also be advised of preventive lifestyle changes involving diet, exercise, alcohol consumption, obesity and smoking. Lifestyle changes can be combined with specific treatments such as anticoagulation therapy, antiplatelet therapy, cholesterol lowering, blood pressure control and diabetes management 103.

This brief review has focused on heart and brain deficits that can lead to cognitive impairment and to Alzheimer or vascular dementia. The collective findings summarized here is that when the human heart and its vasculature enter the process of senescence, there is a gradual deterioration of structure and function which can remain stable for many years or show signs of slow or rapid destabilization. When the cardiovascular system is impaired, the degree of that impairment will determine the severity of the consequent deficits.

The major pathologic fallout generated from cardiovascular deficits is chronic cerebral hypoperfusion (Figure 3). Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in the aging brain can be extremely harmful because it can deprive ischemic‐sensitive brain cells in the hippocampus and cortex of vital nutrients needed for their energy metabolism and survival. Regions of hippocampal and cortical brain cells are associated with learning and memory. Damage or death of these brain cells stemming from insufficient blood flow delivery will diminish cognitive function and increase the risk of dementia 15, 140. Following this logic, it would seem sensible to explore research avenues that may increase blood flow to the aging brain in order to maintain neuronal homeostasis threatened by brain hypoperfusion and ostensibly delay neurocognitive deficits as long as possible.

Increasing Blood Flow to the Brain: A Strategy for Alzheimer Prevention

Until recently, increasing cerebral blood flow was generally limited to pharmacotherapy. Many drugs, including antihypertensives, cholinergics and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, are reported to increase cerebral blood flow but in this author's experience, their action, is brief and unsustainable. Moreover, except for compounds that suppress the activity of carbonic anhydrase 110, the effect of these drugs on raising brain perfusion is trivial. Novel experimental drugs and new devices could be the answer to the problem of sustaining significant cerebral blood flow increase while providing safe limits for long‐term use.

Nitric Oxide

Nitric oxide produced by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) has been shown to be an important regulator of cerebral blood flow 56. Rho kinase (ROCK) is a serine‐threonine kinase that regulates, among many other actions, smooth muscle contraction, and appears to play a role in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular spasm 4, 93.

Reduced cerebral blood flow appears associated with enhanced ROCK activity and decreased eNOS expression 130. When the selective ROCK inhibitors fasudil and hydroxyfasudil were used in a mice ischemic brain model, eNOS expression and nitric oxide production became elevated leading to an increase in cerebral blood flow in both hypoperfused and nonischemic brain regions 130. The increase in cerebral blood flow correlated well with the eNOS increase 130. The effect of fasudil in reversing ischemia is also observed in the heart 7. Fasudil is used clinically as a therapeutic agent against cerebral vasospasm in Japan but is not approved in the United States.

Dimethyl Sulfoxide

An experimental rat model of Alzheimer dementia with severe memory impairment was developed in our laboratory by permanently tying‐off both carotid arteries in old rats 39 and following them over an 18‐week period 41. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was combined with the glycolytic intermediate fructose 1,6‐diphosphate (FDP) and administered orally to cerebral hypoperfused rats from weeks 15–16 following carotid occlusion 41. The rationale for using this drug combination is DMSO's ability to scavenge circulating free radicals and increase cerebral blood flow, thus counteracting induced hypoperfusion 70 and by FDP to act as an intermediate of anaerobic glycolytic metabolism thereby restoring oxidative phosphorylation and increasing the brain cell energy fuel adenosine triphosphate (ATP) when administered during prolonged hypoperfusion states 70, 91.

The results of this study indicated that daily oral administration of DMSO + FDP but not either drug alone is an effective treatment for improving ischemic‐induced visuospatial memory impairment in aging rats. The effect of DMSO + FDP on visuospatial memory improvement and the loss of this effect after discontinuation of therapy on week 16 suggests a drug cause and effect 41, 70. These findings also indicate that in order to maintain memory improvement during induced‐brain hypoperfusion, this drug combination (and possibly most other similar remedies) must be given on a chronic basis.

Angiogenesis

Neoangiogenesis has been obtained experimentally with intravenous injections of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) introduced into ischemic brain tissue 5. Because VEGF does not cross the blood brain barrier easily, angiogenic gene therapy may offer the promise of delivering this protein directly into the brain. The technique would involve delivery of VEGF using plasmids, which are small, circular and relatively inert DNA molecules. However, although plasmids could be injected directly into ischemic brain regions, thereby bypassing the blood–brain barrier, there is a possibility that they may be taken up only temporarily and in a few cells. Nevertheless, success in plasmid delivery of VEGF has been reported in animal models 158 and in patients with critical limb ischemia 10 and ischemic myocardium 87.

Sirtuins

Sirtuins (SIRT) are a family of proteins that regulate a wide variety of cellular processes, among them, mitochondrial energy metabolism and function 13. Understanding SIRT physiological mechanisms may provide a novel approach to control energy metabolic problems associated with aging. So far, seven mammalian homologues of SIRT have been identified. Sirtuins 1‐7 (SIRT1‐7) belong to the class of deacetylase enzymes, which are dependent on NAD+ for activity. Research studies of SIRT support the notion that manipulating SIRT1 activity might result in protection from a host of metabolic derangements brought on by aging and hypoxia 94.

SIRT1 activation studies show that SIRT1 could be a novel therapeutic target in the management of metabolic energy disease and has prompted considerable research to identify other activators of SIRT1 18. For example, resveratrol, a substance found in red wine, has been shown to improve mitochondrial biogenesis and function by enhancing NAD+ levels and promoting SIRT1 activation in mice 67, 80. Based on this evidence, it has been suggested that resveratrol could be useful in the treatment or prevention of age‐related decline in cardiac function and neurometabolic damage 2.

Other SIRT activators such as the flavonoids fisetin and quercetin have been extracted from apples, strawberries and grapes as well as red wine 43. The potential benefits of SIRT activators in aiding the aging process from diseases that will imperil cognitive function remains largely unexplored. However, the appeal of SIRT activators is that they can be found in healthy foods or red wine and consequently have a low risk of side effects for the elderly individual when properly given as supplements to their diet. Moreover, the door has recently opened to countless new synthetic SIRT activators that are considerably more potent than resveratrol 2. Two such synthetic SIRT1 activators SIRT‐2104 and SIRT‐1720 were designed to slow‐down the aging process and delay a number of age‐related diseases in humans, such as inflammatory processes and cardiovascular disorders, two precursors of Alzheimer dementia 98, 101. It is conceivable that SIRT1 activators could constitute a novel class of drugs that could benefit the elderly and perhaps even middle age individuals, a concept that needs to be tested in randomized controlled human trials.

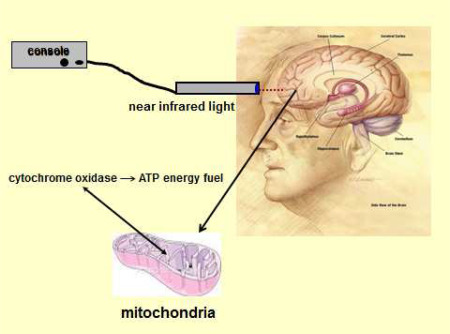

Low Level Laser Therapy

One of the most compelling new approaches to manage cognitive decline is not based on pharmacotherapy but on laser medicine. Low level laser therapy (LLLT) also known as photobiomodulation, is a process where cells or tissue can be exposed to low levels of near‐infrared (NIR) light producing photons to induce a photochemical reaction in the cell that yields molecular energy 20 (Figure 4). These laser‐generated photons can pass through bone relatively efficiently and are absorbed by chromophores in the brain cell mitochondria to stimulate cellular respiration and the release of cytochrome C oxidase to directly increase the production of ATP, the energy fuel for all cell activity 73, 74. The stored energy can then be used to perform cellular tasks that require mitochondrial energy metabolism, for example, modulation of cytotoxic free radicals and neurometabolic function.

Figure 4.

Technique used to increase adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in brain neurons of the prefrontal cortex using low level light therapy (LLLT). The probe for LLLT is placed transcranially on the scalp and a light‐emitting diode releases a steam of photons from the laser light source (console) to activate mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase receptors. After activation, these receptors increase the synthesis of ATP for added neuronal energy. Pilot data is available that suggests executive function is increased in normal volunteers using LLLT. See text for details. Adapted from de la Torre 171.

The possibility of stabilizing neurometabolic function before or during cognitive decline has led investigators to test LLLT as a potential non‐invasive treatment for cognitive impairment secondary to brain hypoperfusion in rats. Rats exposed to LLLT showed a dose‐dependent increase in oxygen consumption in the brain cortex, an indication that cytochrome oxidase activity and ATP were being produced 134. This experiment was followed up with continuous wave near‐infrared light delivered to the forehead of normal human volunteers using a low‐power laser diode with wavelengths adjusted to maximize scalp and skull tissue penetration without inducing damage to either (Figure 4).

In a recent study, a delayed match‐to‐sample memory task and reaction time showed significant improvement for memory retrieval latency and number of correct trials in the LLLT group when compared to the placebo group 8.

This brief trial using LLLT in normal human volunteers suggests that this technique could become an efficient, non‐invasive way to improve cognitive function in people at risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a transitional state that precedes AD onset 60.

Because LLLT appears to improve blood flow 161 and the production of ATP 82, it could be useful not only as a treatment for cognitive decline but also as a preventive intervention in individuals with chronic brain hypoperfusion who are at risk of cognitive impairment and Alzheimer dementia 59. Aside from its preventive potential, LLLT could also be applied as a treatment to elderly individuals with a diagnosis of AD although the outcome of this practice is less clear. This is an attractive tool with clinical promise because ATP and oxygenation could be increased in the brain using NIR light non‐invasively in cases where deficient neuronal energy metabolism might develop from ischemia, trauma or chronic hypoperfusion. Moreover, NIR light therapy has potential application in other brain conditions such as post‐traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety.

As we have reviewed here and elsewhere 33, the rationale for using pharmacotherapy to increase cerebral blood flow to the brain has mounting evidence connecting brain hypoperfusion to MCI and some researchers consider the reduced brain blood flow as the likely the cause of this dyscognitive condition 32, 42, 71, 77, 137, 166. Cerebral hypoperfusion secondary to vascular risk factors during aging delivers suboptimal amounts of glucose and oxygen to hypometabolic brain cells.

Hypoxia from brain hypoperfusion blocks mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, thereby inhibiting ATP synthesis and reoxidation of NADH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide). This leads to a decrease in the ATP/ADP (adenosine dinucleotide) ratio and an increase in the NADH, NAD (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) ratio, a marker of mitochondrial dysfunction.

This pathological progression may be corrected by increasing blood flow to the brain pharmacologically in order to provide needed fuel to the mitochondria which in turn will churn out ATP needed by the hypometabolic nerve cells 40.

It should be pointed out that photobiomodulation has been used experimentally in rat and dog cardiac ischemia where NIR light from light emitting diodes can reduce hypoxia, improve reoxygenation and stabilize myocardial infarction following cardiomyocyte damage 113, 159, 171. Such an approach would also be expected to benefit CBF hemodynamics.

The idea of increasing brain blood flow pharmacologically to prevent cognitive decline however, could be bypassed by a working LLLT technique that would provide direct neuronal cell energy, thereby circumventing increasing blood flow delivery of glucose and oxygen for the same purpose of promoting more ATP synthesis. If pharmacotherapy could be circumvented with LLLT, drug effects and parallel toxicity would be eliminated in the consumer. A technological advancement of this nature would provide hypoperfused brain cells with the energy boost needed to maintain optimal neurometabolism and longer‐term survival. Thus, if further studies are consistent with the concept of photobiomodulation stimulating the mitochondrial respiratory chain and ATP production, it could introduce a simple and efficient method of preventing or treating the dark spectre of cognitive meltdown and dementia 159.

Nevertheless, many unresolved questions remain. For example, how long will mitochondrial production of ATP last after stimulation with LLLT? What optimal wavelength and timing of the applied LLLT will promote the best results to the cognitively impaired patient? How often will patients with cognitive issues need to be treated with LLLT? How will cognitive improvement be measured in LLLT‐treated subjects?

The answer to these and other key questions will need to be addressed before general application of photobiomodulation is clinically applied to patients suffering or at risk of neurometabolic deterioration.

Acknowledgments

The author reports no conflict of interest in the writing of this article.

Re‐use of this article is permitted in accordance with the Terms and Conditions set out at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com/onlineopen#OnlineOpen_Terms

References

- 1. Aaslid R (1987) Visually evoked dynamic blood flow response of the human cerebral circulation. Stroke 18:771–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alcaín FJ, Villalba JM Sirtuin activators (2009). Expert Opin Ther Pat 19:403–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alonso‐Galicia M, Falck JR, Reddy KM, Roman RJ (1999) 20‐HETE agonists and antagonists in the renal circulation. Am J Physiol 277:F790–F796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amano M, Fukata Y, Kaibuchi K (2000) Regulation and functions of Rho‐associated kinase. Exp Cell Res 261:44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Banai S, Jacklisch M, Shou M, Lazarous D, Scheinowitz M (1994) Angiogenic‐induced enhancement of collateral blood flow to the ischemic myocardium by vascular endothelial growth factor in dogs. Circulation 89:2983–2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bangen KJ, Nation DA, Delano‐Wood L, Weissberger GH, Hansen LA, Galasko DR et al (2014) Aggregate effects of vascular risk factors on cerebrovascular changes in autopsy‐confirmed Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 11:394–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bao W, Hu E, Tao L, Boyce R, Mirabile R, Thudium DT et al (2004) Inhibition of ROCK protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res 61:548–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barrett DW, Gonzalez‐Lima F (2013) Transcranial infrared laser stimulation produces beneficial cognitive and emotional effects in humans. Neuroscience 230:13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bauer J, Plaschke K, Martin E, Bardenheuer HJ, Hoyer S (1997) Causes and consequences of neuronal energy deficit in sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 826:379–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baumgartner I, Pieczek A, Manor O, Blair R, Kearney M, Walsh K, Isner JM (1998) Constitutive expression of phVEGF165 after intramuscular gene transfer promotes collateral vessel development in patients with critical limb ischemia. Circulation 97:1114–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Belohlavek M, Jiamsripong P, Calleja AM, McMahon EM, Maarouf CL, Kokjohn TA et al (2009) Patients with Alzheimer disease have altered transmitral flow: echocardiographic analysis of the vortex formation time. J Ultrasound Med 28:1493–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bodlin SJ (2005) Heart failure in the elderly. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 3:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brenmoehl J, Hoeflich A (2013) Dual control of mitochondrial biogenesis by sirtuin 1 and sirtuin 3. Mitochondrion in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bunch TJ, Weiss JP, Crandall B (2010) Atrial fibrillation is independently associated with senile, vascular, and Alzheimer's dementia. Heart Rhythm 7:433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Buratti L, Balucani C, Viticchi G, Falsetti L, Altamura C, Avitabile E et al (2014) Cognitive deterioration in bilateral asymptomatic severe carotid stenosis . Stroke 45:2072–2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Çalık AN, Özcan KS, Yüksel G, Güngör B, Aruğarslan E, Varlibas F et al (2014) Altered diastolic function and aortic stiffness in Alzheimer's disease. Clin Interv Aging 9:1115–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cameron J, Worrall‐Carter L, Page K, Riegel B, Lo SK, Stewart S (2010) Does cognitive impairment predict poor self‐care in patients with heart failure? Eur J Heart Fail 12:508–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cantó C, Gerhart‐Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, Noriega L, Milne JC et al (2009) AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature 458:1056–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cheng J, Wu CC, Gotlinger KH, Zhang F, Falck JR, Narsimhaswamy D, Schwartzman ML (2010) 20‐hydroxy‐5,8,11,14‐eicosatetraenoic acid mediates endothelial dysfunction via IkappaB kinase‐dependent endothelial nitric‐oxide synthase uncoupling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 332:57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chung H, Dai T, Sharma SK, Huang YY, Carroll JD, Hamblin MR (2012) The nuts and bolts of low‐level laser (light) therapy. Ann Biomed Eng 40:516–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Corder EH, Ervin JF, Lockhart E, Szymanski MH, Schmechel DE, Hulette CM (2005) Cardiovascular damage in Alzheimer disease: autopsy findings from the Bryan ADRC. J Biomed Biotechnol 2005:189–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Corrada MM, Berlau DJ, Kawas CH (2012) A population‐based clinicopathological study in the oldest‐old: The 90+ Study. Curr Alzheimer Res 9:709–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. de la Torre JC (1997) Hemodynamic consequences of deformed microvessels in the brain in Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 826:75–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. de la Torre JC (1997) Cerebromicrovascular pathology in Alzheimer's disease compared to normal aging. Gerontology 43:26–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. de la Torre JC (2000) Critically attained threshold of cerebral hypoperfusion: the CATCH hypothesis of Alzheimer's pathogenesis. Neurobiol Aging 21:331–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. de la Torre JC (2002) Alzheimer's disease: how does it start? J Alzheimers Dis 4:497–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de la Torre JC (2004) Alzheimer's disease is a vasocognopathy: a new term to describe its nature. Neurol Res 26:517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de la Torre JC (2004) Is Alzheimer's disease a neurodegenerative or a vascular disorder? Data, dogma, and dialectics. Lancet Neurol 3:184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. de la Torre JC (2006) How do heart disease and stroke become risk factors for Alzheimer's disease? Neurol Res 28:637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. de la Torre JC (2008) Pathophysiology of neuronal energy crisis in Alzheimer's disease. Neurodegener Dis 5:126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de la Torre JC (2008) Alzheimer's disease prevalence can be lowered with non‐invasive testing. J Alzheimers Dis 14:353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. de la Torre JC (2010) The vascular hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: bench to bedside and beyond. Neurodeg Dis 7:116–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. de la Torre JC (2012) Cerebral hemodynamics and vascular risk factors: setting the stage for Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 32:553–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. de la Torre JC (2013) Vascular risk factors: a ticking time bomb to Alzheimer's disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 28:551–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. de la Torre JC (2014) In‐house heart‐brain clinics to reduce Alzheimer's disease incidence. J Alzheimers Dis 42:S431–S442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. de la Torre JC (2016). Alzheimer's Turning Point: A Vascular Approach to Clinical Prevention. Springer. New York, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 37. de la Torre JC, Mussivand T (1993) Can disturbed brain microcirculation cause Alzheimer's disease? Neurol Res 15:146–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. de la Torre JC, Stefano GB (2000) Evidence that Alzheimer's disease is a microvascular disorder: the role of constitutive nitric oxide. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 34:119–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. de la Torre JC, Fortin T, Park G, Butler K, Kozlowski P, Pappas B et al (1992) Chronic cerebrovascular insufficiency induces dementia‐like deficits in aged rats. Brain Res 582:186–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. de la Torre JC, Cada A, Nelson N, Davis G, Sutherland RJ, Gonzalez‐Lima F (1997) Reduced cytochrome oxidase and memory dysfunction after chronic brain ischemia in aged rats. Neurosci Lett 223:165–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. de la Torre JC, Nelson N, Sutherland RJ, Pappas BA (1998) Reversal of ischemic‐induced chronic memory dysfunction in aging rats with a free radical scavenger‐glycolytic intermediate combination. Brain Res 779:285–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Demarin V, Morovic S (2014) Ultrasound subclinical markers in assessing vascular changes in cognitive decline and dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 42(Suppl. 3):S259–S266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. De Santi C, Pietrabissa A, Mosca F, Pacifici GM (2002) Methylation of quercetin and fisetin, flavonoids widely distributed in edible vegetables, fruits and wine, by human liver. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 40:207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. de Toledo Ferraz Alves TC, Ferreira LK, Wajngarten M, Busatto GF (2010) Cardiac disorders as risk factors for Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 20:749–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Di Iorio A, Zito M, Lupinetti M, Abate G (1999) Are vascular factors involved in Alzheimer's disease? Facts and theories. Aging (Milano) 11:345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Di Nisio M, Prisciandaro M, Rutjes AW, Russi I, Maiorini L, Porreca E (2014) Dementia in patients with atrial fibrillation and the value of the Hachinski ischemic score. Geriatr Gerontol Int 15:770–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dodson JA, Truong TT, Towle VR, Kerins G, Chaudhry SI (2013) Cognitive impairment in older adults with heart failure: prevalence, documentation, and impact on outcomes. Am J Med 126:120–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dong YF, Kataoka K, Tokutomi Y, Nako H, Nakamura T, Toyama K et al (2011) Perindopril, a centrally active angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor, prevents cognitive impairment in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. FASEB J 25:2911–2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Driscoll I, Resnick SM, Troncoso JC, An Y, O'Brien R, Zonderman AB (2006) Impact of Alzheimer's pathology on cognitive trajectories in nondemented elderly. Ann Neurol 60:688–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Elias PK, D'Agostino RB, Elias MF, Wolf PA (1995) Blood pressure, hypertension, and age as risk factors for poor cognitive performance. Exp Aging Res 21:393–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ettorre E, Cicerchia M, De Benedetto G (2009) A possible role of atrial fibrillation as a risk factor for dementia. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 49:71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Frank O (1990) The basic shape of the arterial pulse. First treatise: mathematical analysis. J Mol Cell Cardiol 22:255–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Franks PW (2005) White‐coat hypertension and risk of stroke: do the data really tell us what we need to know? Hypertension 45:183–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Forti P, Maioli F, Pisacane N, Rietti E, Montesi F, Ravaglia G (2006) Atrial fibrillation and risk of dementia in nondemented elderly subjects with and without mild cognitive impairment. Neurol Res 28:625–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Genest J Jr, Cohn JS (1995) Clustering of cardiovascular risk factors: targeting high‐risk individuals. Am J Cardiol 76:8A–20A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Girouard H, Wang G, Gallo EF, Anrather J, Zhou P, Pickel VM, Iadecola C (2009) NMDA receptor activation increases free radical production through nitric oxide and NOX2. J Neurosci 29:2545–2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ (2014) Heart disease and stroke statistics–2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 129:e28–e292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gomez CR, McLaughlin JR, Njemanze PC, Nashed A Effect of cardiac dysfunction upon diastolic cerebral blood flow. Angiology 43:625–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gonzalez‐Lima F, Barrett DW (2014) Augmentation of cognitive brain functions with transcranial lasers. Front Syst Neurosci 8:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gonzalez‐Lima F, Barksdale BR, Rojas JC (2014) Mitochondrial respiration as a target for neuroprotection and cognitive enhancement. Biochem Pharmacol 88:584–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Guo Z, Qiu C, Viitanen M, Fastbom J, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L (2001) Blood pressure and dementia in persons 75+ years old: 3‐year follow‐up results from the Kungsholmen Project. J Alzheimers Dis 3:585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hanon O, Haulon S, Lenoir H, Seux ML, Rigaud AS, Safar M et al (2005) Relationship between arterial stiffness and cognitive function in elderly subjects with complaints of memory loss. Stroke 36:2193–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. He Y, Si D, Yang C, Ni L, Li B, Ding M, Yang P (2014) The effects of amlodipine and S(‐)‐amlodipine on vascular endothelial function in patients with hypertension. Am J Hypertens 27:27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Heinzel S, Liepelt‐Scarfone I, Roeben B, Nasi‐Kordhishti I, Suenkel U, Wurster I et al (2014) A neurodegenerative vascular burden index and the impact on cognition. Front Aging Neurosci 6:161–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hofman A, Ott A, Breteler MM, Bots ML, Slooter AJ, van Harskamp F et al (1997) Atherosclerosis, apolipoprotein E, and prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer's disease in the Rotterdam study. Lancet 349:151–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Honig LS, Tang MX, Albert S, Costa R, Luchsinger J, Manly J et al (2003) Stroke and the risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 60:1707–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Howitz KT, Bitterman KJ, Cohen HY, Lamming DW, Lavu S, Wood JG et al (2003) Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature 425:191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hoyer S (1993) Brain oxidative energy and related metabolism, neuronal stress, and Alzheimer's disease: a speculative synthesis. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 6:3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Imtiaz B, Tolppanen AM, Kivipelto M, Soininen H (2014) Future directions in Alzheimer's disease from risk factors to prevention. Biochem Pharmacol 88:661–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Jacob SW, de la Torre JC (2015) Dimethyl Sulfoxide in Trauma and Disease, pp. 133–188. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Johnson NA, Jahng GH, Weiner MW, Miller BL, Chui HC, Jagust WJ et al (2005) Pattern of cerebral hypoperfusion in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment measured with arterial spin‐labeling MR imaging: initial experience. Radiology 234:851–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kalantarian S, Stern TA, Mansour M, Ruskin JN (2013) Cognitive impairment associated with atrial fibrillation: a meta‐analysis. Ann Intern Med 158:338–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Karu TI (1999) Primary and secondary mechanisms of action of visible to near‐IR radiation on cells. J Photochem Photobiol B 49:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Karu TI, Pyatibrat LV, Kalendo GS (1995) Irradiation with He‐Ne laser increases ATP level in cells cultivated in vitro. J Photochem Photobiol B 27:219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kawas CH, Greenia DE, Bullain SS, Clark CM, Pontecorvo MJ, Joshi AD, Corrada MM (2013) Amyloid imaging and cognitive decline in nondemented oldest‐old: the 90+ study. Alzheimers Dement 9:199–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kilander L, Andr'en B, Nyman H, Lind L, Boberg M, Lithell H (1998) Atrial fibrillation is an independent determinant of low cognitive function: a cross‐sectional study in elderly men. Stroke 29:1816–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kitagawa K (2010) Cerebral blood flow measurement by PET in hypertensive subjects as a marker of cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis 20:855–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kivipelto M, Helkala EL, Hänninen T, Laakso MP, Hallikainen M, Alhainen K et al (2001) Midlife vascular risk factors and late‐life mild cognitive impairment: a population‐based study. Neurology 56:1683–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kivipelto M, Solomon A, Ahtiluoto S, Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Antikainen R et al (2013) The Finnish geriatric intervention study to prevent cognitive impairment and disability (FINGER): study design and progress. Alzheimers Dement 9:657–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart‐Hines Z, Meziane H, Lerin C, Daussin F et al (2006) Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC‐1alpha. Cell 127:1109–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lakatta EG, Levy D (2003) Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part I: aging arteries: a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation 107:139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lapchak PA, De Taboada L (2010) Transcranial near infrared laser treatment (NILT) increases cortical adenosine‐5′‐triphosphate (ATP) content following embolic strokes in rabbits. Brain Res 1306:100–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. LaRocca TJ, Hearon CM Jr, Henson GD, Seals DR (2014) Mitochondrial quality control and age‐associated arterial stiffening. Exp Gerontol 58:78–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Leenders KL, Perani D, Lammertsma AA, Heather JD, Buckingham P, Healy MJ et al (1990) Cerebral blood flow, blood volume and oxygen utilization. Normal values and effect of age. Brain 113:27–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lipsitz LA, Gagnon M, Vyas M, Iloputaife I, Kiely DK, Sorond F (2005) Antihypertensive therapy increases cerebral blood flow and carotid distensibility in hypertensive elderly subjects. Hypertension 45:216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Lloyd‐Jones DM, Wang T, Leip EP (2004) Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham heart study. Circulation 110:1042–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Losordo DW, Vale PR, Symes JF, Dunnington CH, Esakof DD, Maysky M et al (1998) Gene therapy for myocardial angiogenesis: initial clinical results with direct myocardial injection of phVEGF165 as sole therapy for myocardial ischemia. Circulation 98:2804–2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Luchsinger JA, Reitz C, Honig LS, Tang MX, Shea S, Mayeux R (2005) Aggregation of vascular risk factors and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Neurology 65:545–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Madan S, Shah S, Partovi S, Parikh SA (2014) Use of novel oral anticoagulant agents in atrial fibrillation: current evidence and future perspective. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 4:314–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Marchal G, Rioux P, Petit‐Taboué MC, Sette G, Travère JM, Le Poec C et al (1992) Regional cerebral oxygen consumption, blood flow, and blood volume in healthy human aging. Arch Neurol 49:1013–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Markov AK (1986) Hemodynamics and metabolic effects of fructose 1,6‐diphosphate in ischemia and shock—experimental and clinical observations. Ann Emerg Med 15:1470–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Marshall RS, Lazar RM, Pile‐Spellman J, Young WL, Duong DH, Joshi S, Ostapkovich N (2001) Recovery of brain function during induced cerebral hypoperfusion. Brain 124:1208–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Masumoto A, Mohri M, Shimokawa H, Urakami L, Usui M, Takeshita A (2002) Suppression of coronary artery spasm by the ROCK inhibitor fasudil in patients with vasospastic angina. Circulation 105:1545–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Mattagajasingh I, Kim CS, Naqvi A, Yamamori T, Hoffman TA, Jung SB et al (2007) SIRT1 promotes endothelium‐dependent vascular relaxation by activating endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:14855–14860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Mazoyer B, Houdé O, Joliot M, Mellet E, Tzourio‐Mazoyer N (2009) Regional cerebral blood flow increases during wakeful rest following cognitive training. Brain Res Bull 80:133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Mcguinness B, Passmore P (2010) Can statins prevent or help treat Alzheimer's disease? J Alzheimer's Dis 20:925–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Meier P, Franzen O, Lansky AJ (2014) Almanac 2013: novel non‐coronary cardiac interventions. Acta Cardiol 69:435–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Mercken EM, Mitchell SJ, Martin‐Montalvo A, Minor RK, Almeida M, Gomes AP et al (2014) SRT2104 extends survival of male mice on a standard diet and preserves bone and muscle mass. Aging Cell 13:787–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Mitchell GF, Parise H, Vita JA, Larson MG, Warner E, Keaney JF Jr et al (2004) Local shear stress and brachial artery flow‐mediated dilation: the Framingham heart study. Hypertension 44:134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. van Mitchell GF, Buchem MA, Sigurdsson S, Gotal JD, Jonsdottir MK, Kjartansson Ó et al (2011) Arterial stiffness, pressure and flow pulsatility and brain structure and function: the age, gene/environment susceptibility–Reykjavik study. Brain 134:3398–3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Mitchell SJ, Martin‐Montalvo A, Mercken EM, Palacios HH, Ward TM, Abulwerdi G et al (2014) The SIRT1 activator SRT1720 extends lifespan and improves health of mice fed a standard diet. Cell Rep 6:836–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Miyata N, Seki T, Tanaka Y, Omura T, Taniguchi K, Doi M et al (2005) Beneficial effects of a new 20‐hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid synthesis inhibitor, TS‐011 [N‐(3‐chloro‐4‐morpholin‐4‐yl) phenyl‐N′‐hydroxyimido formamide], on hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 314:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. National Stroke Foundation (2010). Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management, Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 104. Nimmrich V, Eckert A (2013) Calcium channel blockers and dementia. Br J Pharmacol 169:1203–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Nunnari J, Suomalainen A (2012) Mitochondria: in sickness and in health. Cell 148:1145–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Nys GM, van Zandvoort MJ, de Kort PL, Jansen BP, Kappelle LJ, de Haan EH (2005) Restrictions of the mini‐mental state examination in acute stroke. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 20:623–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. O'Caoimh R, Kehoe PG, Molloy DW (2014) Renin angiotensin aldosterone system inhibition in controlling dementia‐related cognitive decline. J Alzheimers Dis in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. O'Caoimh R, Healy L, Gao Y, Svendrovski A, Kerins DM, Eustace J et al (2014) Effects of centrally acting angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors on functional decline in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 40:595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Oku K, Kurose M, Kubota M, Fukuda S, Kurimoto M, Tujisaka Y et al (2005) Combined NMR and quantum chemical studies on the interaction between trehalose and dienes relevant to the antioxidant function of trehalose. J Phys Chem B Condens Matter Mater Surf Interfaces Biophys 109:3032–3040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Oliver DW, Dormehl IC, Redelinghuys IF, Hugo N, Beverly G (1993) Drug effects on cerebral blood flow in the baboon model—acetazolamide and nimodipine. Nuklearmedizin 32:292–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Omura T, Tanaka Y, Miyata N, Koizumi C, Sakurai T, Fukasawa M et al (2006) Effect of a new inhibitor of the synthesis of 20‐HETE on cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury. Stroke 37:1307–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Ong KT, Delerme S, Pannier B, Safar ME, Benetos A, Laurent S et al (2011) Aortic stiffness is reduced beyond blood pressure lowering by short‐term and long‐term antihypertensive treatment: a meta‐analysis of individual data in 294 patients. J Hypertens 29:1034–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Oron U, Yaakobi T, Oron A, Mordechovitz D, Shofti R, Hayam G et al (2001) Low‐energy laser irradiation reduces formation of scar tissue after myocardial infarction in rats and dogs. Circulation 103:296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. O'Rourke MF, Safar ME (2005) Relationship between aortic stiffening and microvascular disease in brain and kidney: cause and logic of therapy. Hypertension 46:200–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Ott A, Breteler MM, de Bruyne MC, van Harskamp F, Grobbee DE, Hofman A (1997) Atrial fibrillation and dementia in a population‐based study. The Rotterdam study. Stroke 28:316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Ott A, Breteler MM, De Bruyne MC, Van Harskamp F, Grobbee D, Hofman A (1997) Atrial fibrillation and dementia in a population‐based study: the Rotterdam study. Stroke 28:316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Pantano P, Baron J‐C, Lebrun‐Grandie P (1984) Regional cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption in human aging. Stroke 15:635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Polidori MC, Marvardi M, Cherubini A, Senin U, Mecocci P (2001) Heart disease and vascular risk factors in the cognitively impaired elderly: implications for Alzheimer's dementia. Aging (Milano) 13:231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Polidori MC, Marvardi M, Cherubini A, Senin U, Mecocci P (2001) Heart disease and vascular risk factors in the cognitively impaired elderly: implications for Alzheimer's dementia. Aging (Milano) 13:231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Power MC, Weuve J, Gagne JJ, McQueen MB, Viswanathan A, Blacker D (2011) The association between blood pressure and incident Alzheimer disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Epidemiology 22:646–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Pressler SJ, Kim J, Riley P, Ronis DL, Gradus‐Pizlo I (2010) Memory dysfunction, psychomotor slowing, and decreased executive function predict mortality in patients with heart failure and low ejection fraction. J Card Fail 16:750–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Pullicino P, Mifsud V, Wong E, Graham S, Ali I, Smajlovic D (2001) Hypoperfusion‐related cerebral ischemia and cardiac left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 10:178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Purnell C, Gao S, Callahan CM, Hendrie HC (2009) Cardiovascular risk factors and incident Alzheimer disease: a systematic review of the literature. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 23:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Qiu C, von Strauss E, Fastbom J, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L (2003) Low blood pressure and risk of dementia in the Kungsholmen project: a 6‐year follow‐up study. Arch Neurol 60:223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Qiu C, Winblad B, Marengoni A, Klarin I, Fastbom J, Fratiglioni L (2006) Heart failure and risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease: a population‐based cohort study. Arch Intern Med 166:1003–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM (2010) Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med 362:329–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Rajappan K, Ginks M (2014) Catheter ablation of persistent atrial fibrillation. Future Cardiol 10:553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Ramchandra R, Barrett CJ, Malpas SC (2005) Nitric oxide and sympathetic nerve activity in the control of blood pressure. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 32:440–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]