Abstract

The integrated diagnosis of anaplastic oligodendroglioma, IDH mutant and 1p/19q co‐deleted, grade III (O3id) is a histomolecular entity that WHO 2016 classification distinguished from other diffuse gliomas by specific molecular alterations. In contrast, its cell portrait is less well known. The present study is focused on intertumor and intratumor, cell lineage‐oriented, heterogeneity in O3id. Based on pathological, transcriptomic and immunophenotypic studies, a novel subgroup of newly diagnosed O3id overexpressing neuronal intermediate progenitor (NIP) genes was identified. This NIP overexpression pattern in O3id is associated with: (i) morphological and immunohistochemical similarities with embryonic subventricular zone, (ii) proliferating tumor cell subpopulation with NIP features including expression of INSM1 and no expression of SOX9, (iii) mutations in critical genes involved in NIP biology and, (iv) increased tumor necrosis. Interestingly, NIP tumor cell subpopulation increases in O3id recurrence compared with paired newly diagnosed tumors. Our results, validated in an independent cohort, emphasize intertumor and intratumor heterogeneity in O3id and identified a tumor cell subpopulation exhibiting NIP characteristics that is potentially critical in oncogenesis of O3id. A better understanding of spatial and temporal intratumor cell heterogeneity in O3id will open new therapeutic avenues overcoming resistance to current antitumor treatments.

Keywords: anaplastic oligodendroglioma, 1p/19q co‐deletion, embryonic subventricular zone, neuronal intermediate progenitor

Introduction

Anaplastic diffuse gliomas form a group of primary malignant brain tumors with a significant clinical, radiological, histological and molecular intertumor heterogeneity. Historically and in WHO 2007, the histological diagnosis of these tumors was defined by morphological similarities between tumor glial cells and normal glial cells 46: anaplastic astrocytoma (A3)/glioblastoma (GBM), anaplastic oligodendroglioma (OD3) or anaplastic oligo‐astrocytoma (OA3) presenting astrocyte‐like cells, oligodendrocyte‐like tumor cells, or a mixed phenotype, respectively. Because key mutations defining different oncogenic molecular pathways with high clinical relevance were identified, these tumors are now classified by WHO 2016 according to an integrated histomolecular diagnosis combining histological information (demonstration of diffuse glioma and grading criteria) and molecular information (presence or absence of key molecular alterations) 4, 41, 47, 64.

The WHO 2016 integrated diagnosis of anaplastic oligodendroglioma IDH‐mutant and 1p/19q codeleted (O3id) is a diffuse glioma with chromosome arms 1p/19q co‐deletion, IDH (ie, IDH1 or IDH2 genes) mutation and one or more criteria of anaplasia (high mitotic activity, microvascular proliferation, and necrosis) 47. O3id exhibit better prognosis and better chemosensitivity compared with other anaplastic diffuse gliomas 12, 74. However, they ineluctably relapse and become resistant to anti‐tumor treatments similarly to the other diffuse gliomas. O3id frequently present the histological diagnosis of OD3 or OA3, express the “proneural” tumor signature 20 but the cell phenotype of this histomolecular entity is poorly understood.

Several recent works on human tumors and murine models of gliomas showed that oligodendroglial precursor cells (OPC) are the cells of origin and/or the tumor propagating cells in gliomas with oligodendroglial morphology 45, 61. In contrast, tumor cells with neural stem cells (NSC) phenotype were rarely found in such tumors 7.

In embryo, neural stem cells (NSC) produce, first, neuronal precursors directly or via neuronal intermediate progenitors (NIP). After the glial switch, NSC becomes gliogenic progenitors and produce: (i) oligodendrocytes via OPC and, (ii) later, astrocytes via astrocyte precursors cells (APC) 39. Gene expression is highly dynamic during specification and differentiation of these lineages as showed by single cell analysis 35. In the early neuronal lineage, the transcription factor INSM1 promotes neuronal fate and expansion of NIP and is downregulated in more differentiated neuronal cells 22, 35. ELAVL2 [embryonic lethal abnormal visual system (ELAV)‐like neuron‐specific RNA binding protein 2] is highly expressed in NIP 35 and promotes neuronal differentiation and mitotic arrest by regulation of the transduction of mRNA 1. The transcription factor SOX11 is involved in neuronal differentiation from NIP to mature neuron 8, 13, 35. We, thus, decided to investigate the phenotype of O3id tumor cells in light of cell types reported during CNS development.

Material and Methods

Patients and tumors selection

Two cohorts of adult supratentorial high grade diffuse gliomas were established retrospectively: (i) a training cohort from the Hôpitaux Universitaires La Pitié‐Salpêtrière, and (ii) a validation cohort from POLA—prise en charge des tumeurs oligodendrogliales anaplasiques—network cohort. The training cohort included 33 newly diagnosed cases: (i) 33 with available tumor tissue for immunohistochemistry, (ii) 23 with available transcriptome profiling data and (iii) 21 with enough tumor tissue for targeted expression profiling using RT‐PCR. Six adult non‐tumor brain tissue samples (from epilepsy surgery) were used as non‐tumor control. Informed consents of patients were obtained for review of medical records for researches purposes and molecular analysis of biological tissues. The POLA network validation cohort included 94 cases with available transcriptome profiling data previously reported 62. Human fetuses without any neuropathological alterations were collected after legal abortion or spontaneous death. All procedures were approved by the ethics committee (Agence de Biomédecine; approval number: PFS12‐0011).

Pathology, genetic and transcriptomic analysis

Tumors of the training cohort were reviewed by two pathologists (FB and KM). Histological characteristics of tumors of the validation cohort were established during a central review described in a previous report 62. Only histological diagnoses of OD3 or OA3 which are further called anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors (AOT) were selected for further studies. IDH1/2 mutational and chromosome arms 1p/19q statuses were determined as previously described 20, 30. Tumors were then classified according to the WHO 2016 integrated diagnoses of (i) anaplastic oligodendroglioma, IDH‐mutant and 1p/19q co‐deleted (O3id), anaplastic astrocytoma IDH‐mutant, glioblastoma IDH‐mutant, glioblastoma IDH‐wildtype and anaplastic oligo‐astrocytoma, NOS. The three last tumor types were gathered in a group termed “non 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT”. The RNA extraction and the gene expression profiling upon Genechip Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Expression array (Affymetrix, CA) were performed as previously described 20.

Reverse transcription‐PCR (RT‐PCR)

Quantitative gene expression measurements, at mRNA level, were performed for 24 genes (22 genes of interest and 2 control genes) using the « UPL assay design center » (Roche Applied Science®) (Supporting Information Table 1). RT‐PCR was performed as described previously 3.

Immunohistochemistry and staining scoring

Tissue sections were cut from formalin‐fixed and paraffin‐embedded (FFPE) tumor samples. Sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. For fluorescent immunolabeling, antigen retrieval was performed using pH = 6.0 citrate buffer or pH = 8.0 Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid buffer and microwave heating. After blocking with fetal calf serum, sections were incubated with primary antibodies (Table 1). The following secondary antibodies were used: Alexa 488 Donkey anti‐Mouse IgG, Cy3 Donkey anti‐Rabbit IgG, Cy3 Donkey anti‐Goat IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch Lab., Inc., Baltimore). Nuclei were labeled with 4′,6‐Diamidino‐2‐Phenylindole (DAPI). Fluorescence microscope Axio Imager Z1 (Zeiss®) was used to acquire signal. The fluorescent immunolabeling markers (SOX9, INSM1, and marker of proliferation Ki‐67) were quantified by counting single cells. For chromogenic immunolabeling, deparaffinization and immunolabeling of the sections were performed manually or by a fully automated immunohistochemistry system Ventana benchmark XT system® (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) using as chromogen: streptavidin–peroxidase complex with diaminobenzidin, alkaline phosphatase with Fast Red (ultraView Universal Alkaline Phosphatase Red Detection Kit, Ventana®) or Vector Blue (Vector®). The chromogenic immunolabeling of markers (INSM1 for Insulinoma‐associated 1, NFIA for Nuclear Factor I/A) were quantified by evaluating the ratio of the number of immunopositive cells out of the number of all tumor cells. The ELAVL2 and SOX11 immunolabeling were evaluated by a score ranging from 0 to 400 adapted from Hirsch et al 28. The percentage of tumor cells at different staining intensities was determined by visual assessment: Score = (percentage area of weak labeling × 2) + (percentage area of moderate labeling × 3) + (percentage of intense labeling × 4). Micrographs were acquired with Axiocam ICc 1 camera and Axiovision 4.8.2 software (Zeiss®).

Table 1.

List of primary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry.

| Species | Antigen | Dilution | Reference | Provider |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rabbit polyclonal | ELAVL2 | 1/500 | 14008‐1‐AP | Proteintech |

| Mouse monoclonal H09 | IDH1 R132H | 1/50 | DIA‐H09 | Dianova |

| Mouse monoclonal 2E3 | INA | 1/100 | NB300‐140 | Novus Biologicals |

| Goat polyclonal | Ki67 | 1/80 | sc‐7844 | Santa Cruz |

| Mouse monoclonal | INSM1 | 1/250 | sc‐271408 | Santa Cruz |

| Rabbit polyclonal | NFIA | 1/400 | NBP1‐81406 | Novus Biological |

| Rabbit polyclonal | SOX9 | 1/50 | sc‐20095 | Santa Cruz |

| Rabbit polyclonal | SOX11 | 1/100 | HPA000356 | Sigma‐Aldrich |

Computational biology analysis

Gene signatures of the different CNS cell types observed during development (ie, lineages from NSC to neurons, oligodendrocytes and astrocytes) were retrieved from the literature (Supporting Information Table 2, Figure 1a) 39. A gene list was retrieved from study of NIP in the cerebral cortex 35 and only genes expressed in both subpallium and pallium of mouse embryo were selected to build a forebrain NIP signature. Human genes homologous to murine genes were identified using the software bioDBnet 53. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed with the JavaGSEA application using the following parameters: number of permutations = 1000, False Discovery Rate less than 0.25, permutations of phenotype 51, 70. Hierarchical clustering was performed using Babelomics 4.3 with Self Organizing Tree Algorithm (SOTA) and correlation coefficient of Spearman 50. As a preliminary step, tumor samples which co‐segregate with non‐tumor brain were excluded for the following analysis because they were considered as highly contaminated by non‐tumor cells.

Table 2.

Clinico‐patho‐biological characteristics of NIPhigh and NIPlow subgroups of oligodendrogliomas.

| NIPhigh | NIPlow | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 34 | 52 | ||

| Age (y) | 48.7 (11.1 n = 34) | 44.9 (11.0 n = 52) | P = 0.121 | NS, t test |

| Male | 20 | 31 | P = 0.941 | NS, chi 2 |

| Female | 14 | 21 | ||

| Frontal lobe involved | 28 | 43 | P = 0.811 | NS, chi 2 |

| Frontal lobe not involved | 6 | 8 | ||

| OD3 | 32 | 45 | P = 0.470 | NS, Fisher |

| OA3 | 2 | 7 | ||

| Mitoses per 10 high power fields | 11.3 (7.7 n = 30) | 9.5 (7.0 n = 47) | P = 0.210 | NS, Mann–Whitney |

| Microvasc. proliferation | 32 | 38 | P = 0.0142 | NS, chi 2 |

| No microvasc. proliferation | 2 | 14 | ||

| Necrosis | 14 | 6 | P = 0.0034* | S, chi 2 |

| No necrosis | 20 | 46 | ||

| INA IHC + | 33 | 46 | P = 0.236 | NS, Fisher exact test |

| INA IHC − | 1 | 6 | ||

| IDH mutant | 30 | 51 | (by definition) | |

| IDH wt | 1 | 1 | ||

| CIC mutated CIC wt |

14 7 |

15 16 |

P = 0.244 | NS, chi 2 test |

| 1p/19q co‐del | 34 | 52 | (by definition) | |

| Non 1p/19q co‐del. | 0 | 0 | ||

| 9p loss | 9 | 14 | P = 0.963 | NS, chi 2 test |

| 9p retained | 25 | 38 | ||

| 10q loss | 5 | 4 | P = 0.146 | NS, Fisher test |

| 10q retained | 26 | 51 |

Cases of training and validation series were gathered. Standard deviation is indicated between brackets. Number of cases is precised between brackets. The threshold of significance P < 0.05 was adjusted for multiple comparison by Bonferroni method. The adjusted threshold is P < 0.0045. Abbreviations: co‐del., co‐deletion; IHC, immunohistochemistry; microvasc., microvascular; NS, non‐significant; OA3, anaplastic oligo‐astrocytoma; OD3, anaplastic oligodendroglioma; S, significant; wt, wildtype, y: years.

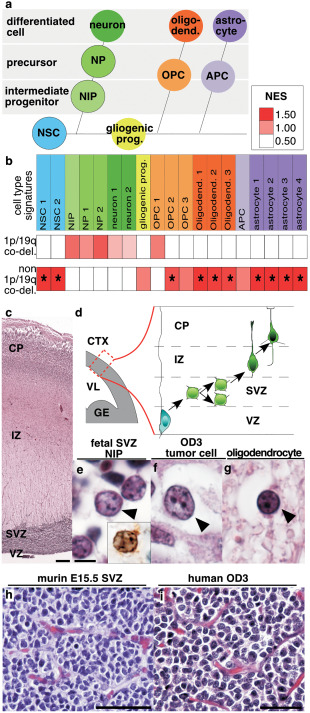

Figure 1.

Expression of cell lineage signatures according to 1p/19q co‐deletion status in anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors. a. Schematic representation of embryonic central nervous system lineages. Neural stem cells produce neurons, becomes gliogenic progenitors after the glial switch and then produce oligodendrocytes and astrocytes. b. Normalized Enrichment Score obtained by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis for cell lineage signatures is presented by a color scale. Significant enrichments (False Discovery Rate < 0.25) are indicated by an asterisk. c. Human cerebral cortex at gestational week 19 (GW19) (H&E). d. Schema of the embryonic mammalian cerebral cortex with its layers: ventricular zone containing neural stem cells, subventricular zone containing neuronal intermediate progenitors, intermediate zone containing neuronal precursors and cortical plate containing differentiating neurons. e. Neuronal intermediate progenitors (arrowhead) in the human fetal GW19 SVZ (H&E) are identified by INSM1 immunostaining (inset in e). f, g. Adult human anaplastic oligodendroglioma with tumor cell (arrowhead in f, H&E) and residual oligodendrocyte (arrowhead in g, H&E). h. Murine cerebral cortex SVZ at embryonic day 15 and i. human anaplastic oligodendroglioma: both presented honey comb aspect and branched vessels. Abbreviations. 1p/19q co‐del., 1p/19q co‐deletion; APC, astrocyte precursor cell; CP, cortical plate; CTX, cerebral cortex; GE, ganglionic eminence; gliogenic prog., gliogenic progenitors; IZ, intermediate zone; NES, Normalized Enrichment Score; NIP, neuronal intermediate progenitor; NP, neuronal precursor; NSC, neural stem cells; OPC, oligodendrocyte progenitor cell; OD3, anaplastic oligodendroglioma (grade III); SVZ, subventricular zone; VL, lateral ventricle; VZ, ventricular zone. Scale bars. C: 250 µm; E–G: 5 µm; H: 25 µm; I: 50 µm.

Statistical analysis

Discrete variables with normal distribution were compared between two groups by two‐tailed t test; other discrete variables were compared by Mann–Whitney test. Discrete variables were compared between three or more groups by Kruskal–Wallis test; post‐hoc pairwise comparisons were performed by Wilcoxon rank sum test or by Mann–Whitney test. Qualitative variables were compared by Chi‐square test if expected values were superior to 5, if not by Fisher exact test. A Bonferroni correction was used when a multiple comparison was performed. Survival analysis was performed by Kaplan–Meier method and log‐rank test.

Results

O3id overexpress neurogenesis genes

In order to determine the cell phenotype of O3id, we compared gene expression of O3id to non 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT (tumors with OD3 or OA3 histological diagnoses that do not fulfill the criteria of integrated diagnosis of O3id) in the training series. CNS cell lineage expression signatures obtained from previously reported expression arrays were compared between O3id (n = 13) vs. non 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT (n = 10) using GSEA (Figure 1a, b; Supporting Information Table 3). Although not reaching statistically significant thresholds, the only enrichments observed in O3id:were: (i) neuronal intermediate progenitor (NIP), (ii) neuronal precursor, (iii) neuron and (iv) OPC. By contrast, O3id showed significant underexpression of gene lists related to NSC, mature oligodendrocytes and astrocytes.

Using quantitative RT‐PCR, expression of markers of CNS cell lineages revealed significantly overexpression of Doublecortin (DCX, neuronal precursor marker) and underexpression of Nuclear factor 1 A‐type (NFIA, glial marker) in O3id (n = 14) vs. non‐tumor brain samples (n = 6). In addition, NFIA was significantly underexpressed in O3id compared with non 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT (n = 7) (Supporting Information Figure 1).

In the same line, immunolabeling showed that the ratio of NFIA‐positive/total tumor cells was lower in O3id than in non 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT (0.33 vs. 0.79 respectively, nO3id =14 and n = 19non 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT, P = 0.0007, Supporting Information Figure 1).

O3id share features with embryonic subventricular zone containing NIP

NIP are located in the embryonic subventricular zone (eSVZ) which is located between the ventricular zone (VZ) containing the NSC/apical progenitors and the intermediate zone (IZ) containing axonal processes and migrating neuronal precursors (Figure 1c, d).

O3id cells were morphologically closer to NIP (at gestational week 19 when corticogenesis is ongoing) than adult oligodendrocytes (Figure 1e–g). Indeed, similarly to O3id tumor cells, NIP have round nucleus, clear chromatin, several small nucleoli, and clear perinuclear halo.

O3id share additional similar features with eSVZ from E15.5 mouse embryo cerebral cortex: (i) a rich anastomotic capillary network with “chicken wire” branching 31, 75 (Figure 1h–i), and (ii) a perinuclear dot expression staining pattern of the neuronal intermediate filament internexin alpha (INA), a positive‐marker of neurons and their early precursors 43 and a negative marker of oligodendrocytes (Supporting Information Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hierarchical clustering of tumors according to the expression of genes of the gliogenic progenitor vs. NIP. a. columns correspond to tumors and lines correspond to genes. NIPhigh subgroup contained 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT clustering together with higher expression of NIP genes. NIPlow subgroup contained the other 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT. b. WHO 2016 histological and integrated diagnoses and molecular markers are indicated for each tumor. Abbreviations: A3, IDH‐mutant: anaplastic astrocytoma, IDH‐mutant; GBM, IDH‐mutant: glioblastoma, IDH‐mutant; GBM, IDH‐wildtype, glioblastoma, IDH‐wildtype; IHC, immunohistochemical; OA3, anaplastic oligo‐astrocytoma; OD3, anaplastic oligodendroglioma.

Finally, the most commonly mutated genes in O3id are CIC, FUBP1, NOTCH2 and TCF12 9, 40 were reported highly expressed in the eSVZ on mouse embryos in public atlas (Supporting Information Figure 3).

Two subgroups of O3id were identified based on their expression of NIP genes

A hierarchical clustering of O3id was thus performed based on genes committing to neurogenesis or to gliogenesis (NIP list and gliogenic progenitor list). Two subgroups of O3id were identified. The NIPhigh sugbroup (n = 7/13, 54%) contained O3id exhibiting higher expression of NIP and OPC genes. The other O3id were considered as the NIPlow subgroup (n = 6/13, 46%) and showed higher expression of genes associated with gliogenic progenitors, astrocytes and mature oligodendrocytes compared with NIPhigh subgroup (Figure 2a, b).

Similarly to the results obtained in the training set, O3id overexpressed gene lists of the neuronal lineage in the multicentric validation cohort including 73 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT and 21 non 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT (Supporting Information Figure 4; Supporting Information Table 4). A NIPhigh subgroup (n = 27/73, 37%) and a NIPlow subgroup (n = 46/73, 63%) of O3id were identified (Supporting Information Figure 5).

NIPhigh O3id exhibit proliferating INSM+/SOX9‐ tumor cells subpopulation

The following markers addressing different steps of the neuronal lineage were used: (i) INSM1 as a specific marker of NIP in the developing CNS, not expressed in the adult CNS (Supporting Information Figure 6) and which drives NIP specification and expansion 14, 22, 42, (ii) ELAVL2 as a marker of NIP promoting mitotic arrest and neuronal differentiation 1, 35, (iii) SOX11 as a marker of differentiation from NIP to neurons 8, 13, and (iv) SOX9 as a marker of immature glial cells and OPC 33.

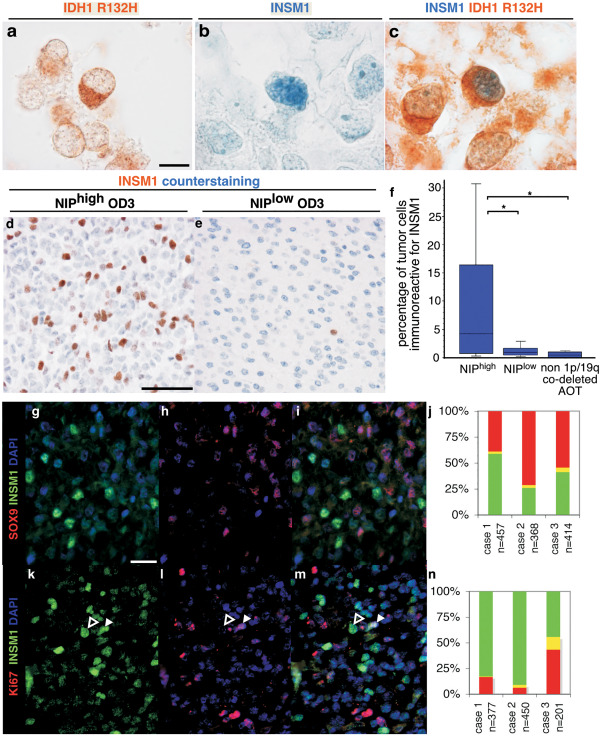

INSM1 immunostaining was positive in large tumor cells areas characterized by high cell density in NIPhigh subgroup tumors. In addition, association of nuclear INSM1 labeling with cytoplasmic IDH1 R132H labeling within the same cells demonstrated that O3id tumor cells express INSM1 (n = 2/2, Figure 3a–c).

Figure 3.

INSM1 immunolabeling in anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors. a–c. three sections of the same anaplastic oligodendroglial tumor of the NIPhigh subgroup were immunolabeled for IDH1 R132H (brown signal in a, c), and INSM1 (blue signal in b, c). Some tumor cells showed cytoplasmic immunolabeling for IDH1 R132H and nuclear immunolabeling for INSM1 (c). d, e. Immunolabeling of INSM1 (brown signal) and counterstaining (blue signal) in anaplastic oligodendroglioma of the NIPhigh and NIPlow subgroups. f. Quantification of INSM1 immunolabeling in NIPhigh vs. NIPlow and non 1p/19q co‐deleted tumors with significant difference (P = 0.0163 Kruskal–Wallis test; asterisk NIPhigh vs. NIPlow P = 0.0454; asterisk NIPhigh vs. non 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT P = 0.0143; Mann–Whitney test). g–i. Double immunolabeling of an anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors of the NIPhigh subgroup by INSM1 (green, g, i) and SOX9 (red, h, i) with quantification (j). Both markers are expressed by two mainly exclusive tumor cell populations. k–m, double immunolabeling of an anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors of the NIPhigh subgroup by INSM1 (green, k, m) and Ki‐67 (red, l, m) with quantification (n). Most INSM1+ cells are negative for Ki‐67 (open arrowhead, f–h) and a minority of INSM1+ cells are positive for Ki‐67 (solid arrowhead, f–h). Scale bars. A–C: 10 µm, D–E: 50 µm. G–I, K–M: 20 µm.

The proportion of tumor cells expressing INSM1 was significantly higher in NIPhigh O3id compared with NIPlow O3id and to non 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT (nNIPhigh = 11, nNIPlow = 16, nnon 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT =8 p = 0.0163, Kruskal–Wallis) (Figure 3d–f).

INSM1 and SOX9 immunolabeling mainly excluded each other showing their expression by two distinct tumor cell populations: INSM1+/SOX9‐ NIP‐like cells and INSM1‐/SOX9+ OPC‐like cells (Figure 3g–j). Interestingly, INSM1+ and SOX9+ tumor cells both proliferate (Figure 3k–n, data not shown).

ELAVL2 and SOX11 immunolabeling showed expression by a majority of tumor cells with heterogeneous level in a majority of OD3id. Assessment of the expression by Hirsch score showed a nonstatistically significant higher expression of SOX11 and ELAVL2 in NIPhigh vs. NIPlow tumors (nNIPhigh = 12, nNIPlow = 16, mean score SOX11NIPhigh = 273 ±46, mean score SOX11NIPlow = 248 ±74, SOX11 P = 0.53; mean score ELAVL2NIPhigh= 206 ±104, mean score ELAVL2NIPlow = 177 ±95, ELAVL2 P = 0.43, Mann–Whitney test). Tumor areas with INSM1 expression showed higher expression of SOX11 and ELAVL2 (n = 6, Supporting Information Figure 7).

NIPhigh O3id clinico‐patho‐biological characteristics compared with NIPlow O3id

Age, sex, brain location, mitotic activity, and INA expression were not significantly different between NIPhigh and NIPlow O3id tumors or patients (Table 2). Necrosis was significantly more abundant in NIPhigh subgroup vs. NIPlow subgroup (P = 0.0034). Microvascular proliferation was significantly more frequent in NIPhigh subgroup vs. NIPlow subgroup with nonadjusted P = 0.0142. However, this difference was not significant if p is adjusted for multiple comparisons (threshold of significance P < 0.0045). Chromosome arm 9p and chromosome arm 10q losses occurred at similar rates in both subgroups. The analysis of overall survival showed no statistically significant difference between NIPhigh and NIPlow subgroups (nNIPhigh = 34, nNIPlow = 52, P = 0.582, Supporting Information Figure 8) but older age had a worse prognosis (nage < 45y = 38, nage > 45y = 48, P = 0.013) and necrosis and microvascular proliferation showed a trend for shorter survival (nno necrosis = 65, nnecrosis = 21, P = 0.055, and nno microvascular proliferation = 16, nmicrovascular proliferation = 70, P = 0.074, respectively).

GSEA for GeneOntology lists found an enrichment in NIPhigh subgroup vs. NIPlow subgroup for genes involved in DNA metabolism, RNA metabolism, DNA methylation and histones methylation (Supporting Information Table 5). GSEA for Oncogenic Signature lists found an enrichment in NIPhigh subgroup in both training and validation sets for genes associated with: (i) activation of Sonic Hedgehog, MYC, E2F1 and, (ii) inactivation of retinoblastoma and EZH2.

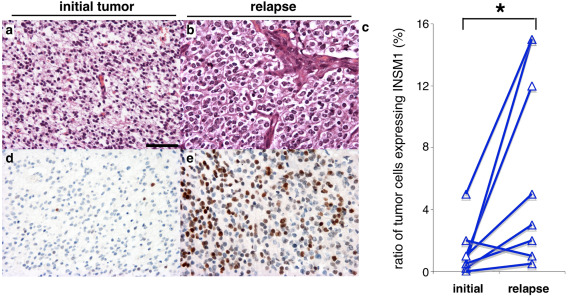

A significant increase of the ratio of INSM1+ tumor cells/total tumors cells was observed in a cohort of 8 O3id compared with their paired newly diagnosed 1p/19q co‐deleted tumors (paired t test, P = 0.03) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

INSM1 expression in newly diagnosed tumors and their relapse. a, b. H&E of a newly diagnosed anaplastic oligodendroglioma (a) and its relapse (b). c. Quantification of the ratio of INSM1 positive tumor cells among the total tumor cells in initial tumors and their relapse. Pairs of tumors are linked by a line. Asterisk correspond to P = 0.03, paired t test. d, e. INSM1 immunolabeling (brown) and blue counterstaining of the newly diagnosed (d) and relapsing (e) tumors. Scale bar: a, b, d, e: 100 µm.

Discussion

Over the last years, significant advances have been accomplished in deciphering intertumor heterogeneity in anaplastic diffuse gliomas 71. In contrast, intratumor cell phenotypic heterogeneity has been less investigated. Transcriptomic classification of glioblastoma identified a “proneural” signature which is enriched in O3id 20, 76. Nevertheless, the “proneural” signature associates genes of oligodendroglial and neuronal lineages and thus does not correspond exactly to the proneural specification program governing neuronal vs. glial lineages in the normal CNS. Therefore, the current work was focused in deciphering the intertumor and intratumor heterogeneity of tumor cell phenotype compared with CNS lineages.

It has been recently demonstrated that the cell of origin of oligodendroglioma is OPC 45, 61 and it is admitted that oligodendroglioma cells mimic normal oligodendroglial lineage 46. However, we have observed enrichment for gene expression of neuronal lineage (NIP, neuronal precursors and neurons) in O3id. Contamination of tumor tissue by infiltrative normal adult neurons cannot account for the expression of NIP markers as INSM1 which are downregulated after embryonic development and are not expressed by adult neurons 2, 22, 42 (Supporting Information Figure 6). In addition, the neuronal phenotype of some tumor cells was confirmed by INSM1 expression in IDH1 R132H immunoreactive cells. Nonetheless, contamination of tumor samples by residual neurons may explain the expression of the gene lists related to mature neurons. We also observed frequent expression of the NIP markers ELAVL2 and SOX11 by tumor cells of OD3id. SOX11 expression in high grade gliomas was reported 78 and SOX11 overexpression in xenografted human gliomas cells promoted neuronal differentiation 69. ELAVL2 expression was reported in glioblastoma 65 but not in oligodendroglioma. We observed a co‐expression of INSM1, ELAVL2 and SOX11 in the same tumor areas which supports the activation of a neurogenesis gene network in a tumoral subpopulation rather than a random and uncoupled expression of these markers across the tumor bulk. INSM1 expression corresponds to the more immature step of NIP expansion in comparison to ELAVL2 and SOX11 which drive neuronal differentiation. Higher expression of INSM1 in NIPhigh vs. NIPlow favors a more immature phenotype of this subgroup whereas ELAVL2 and SOX11 are more widely expressed in both NIPhigh and NIPlow subgroups.

Previous works reported neuronal features in O3id supporting a neuronal specification of some AOT cells: (i) a rare neurocytic morphology 48, 52, 54, 60, (ii) a rare gangliocytic morphology 29, 58, 72, 81, or (iii) frequent neuronal markers expression, for example, INA in tumors with honeycomb “oligodendroglial” morphology 19, 20, 21 and see Supporting Information Table 6 for the list of other neuronal markers expressed in AOT). The absence of neurocytic/gangliocytic histological variants in our series excludes that the enrichment of neuronal gene lists that we observed in O3id corresponds to these rare variants. As most of the gene lists were inferred by homology with mouse cell types, our comparisons need to be improved in the future using characteristics of human neural lineages. The comparison of O3id with the neuronal lineage opens new perspectives for investigating tumor biology. Genes recurrently mutated in O3id (CIC, FUBP1, NOTCH2, TCF12) are expressed in murine embryonic cortical SVZ at E13.5. These genes could be involved in cortical NIP biology although such a role has not been reported. Indeed, at E13.5, only neurogenesis occur in the cortical SVZ whereas oligodendrogliogenesis will occur at birth 36. As some tumor cells of O3id have a NIP phenotype, embryonic SVZ could be a model to test a specific functional effect of these mutations in NIP. Nevertheless, we did not find association between CIC mutation and NIPhigh subgroup and CIC, FUBP1, NOTCH2, TCF12 could have roles in both neuronal and oligodendroglial lineages which require further studies. CIC and NOTCH2 are expressed in cerebellar neuronal precursor and NOTCH2 was shown to inhibit differentiation and to maintain proliferation 44, 67. Notch signaling had a tumor suppressor role in a murine glioma model: the decrease of Notch signaling in this murine model mimicked glioblastoma with primitive neuronal component 25. Our analysis revealed an enrichment of MYC and Shh signaling in the NIPhigh subgroup which may be involved in NIP‐like tumor cells proliferation. MYC pathway was shown to promote neurogenesis in the chick embryo 83 and MYC amplification transform gliomas into glioblastoma with primitive neuroectodermal tumor‐like component/GBM‐PNET‐like 59 termed glioblastoma with primitive neuronal component in WHO 2016 47. MYC activity was shown to be increased in a subgroup of OD3id by several mechanisms 32. The extracellular signal Shh was shown to promote proliferation of bipotent (neuronal and oligodendroglial) embryonic progenitors 82. Shh and MYC signaling pathways thus appear as putative therapeutic targets to treat OD3id with NIPhigh phenotype.

Based on gene expression profiling, we observed different phenotypes among AOT associated to the expression of the master genes controlling glial specification and to the tumor genotypes. SOX9 and NFIA together control a glial fate 17, 33, 57. Maintained NFIA expression determines astrocytic fate by inhibiting SOX10. By contrast, NFIA downregulation in OPC allows SOX10‐induced oligodendroglial specification 27. SOX10 was previously shown to be expressed in all glioma subtypes, whereas NFIA expression was low in oligodendrogliomas and high in astrocytomas 5, 23, 26, 63, 68. We observed higher expression of SOX9 and NFIA, and significant enrichment of gene list related to astrocytes in non 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT. These findings are consistent with SOX9 and NFIA controlling gliogenesis mainly along the astrocytic lineage in the integrated diagnosis of anaplastic astrocytoma, IDH‐mutant. By contrast, OD3id showed lower expression of SOX9 and sparse NFIA expression consistent with rarer astrocytic cells. We showed, for the first time to the best of our knowledge, the possibility to distinguish 1p/19q co‐deleted and non 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT by the ratio of NFIA+ tumor cells with high sensitivity and specificity. Although loss of ATRX identified most of IDH‐mutant non 1p/19q co‐deleted tumors, NFIA could help detection of ATRX maintained, non‐1p/19q co‐deleted tumors. Its reliability waits for validation in larger series.

We described a new intertumor heterogeneity in OD3id based on the NIP phenotype: NIPhigh and NIPlow subgroups. The NIPhigh subgroup accounted for 54% and 37% of training set and validation set, respectively. The two subgroups could correspond to different cell of origin or oncogenic pathways but we did not observe significant differences in genetic alterations between both subgroups. The enrichment in the NIPhigh subgroup of lists involved in DNA methylation and EZH2 function suggests that methylation profiles could also distinguish the two subgroups and will require further studies. Alternatively, NIPhigh subgroup could result from the progression of NIPlow subgroup as suggested by: (i) more frequent necrosis and microvascular proliferation in NIPhigh subgroup, and (ii) increase of INSM1 expression in relapses. The increase of the NIPhigh phenotype during tumor progression could result from tumor dedifferentiation and increased plasticity between glial and neuronal lineages. Differently, a small subpopulation of progenitor‐like tumor cells that lack differentiation and harbor higher lineage plasticity could exist in the initial tumor and would increase during tumor progression.

Microvascular proliferation and necrosis were associated to shorter survival in OD3id 24. In our series, these parameters showed a non‐statistically significant trend for worse prognosis probably because of the limited number of cases. NIPhigh subgroup showed more frequent microvascular proliferation (94%) and necrosis (41%) than NIPlow subgroup (26% and 12%, respectively) but NIPhigh phenotype did not have prognostic value. We propose that NIPhigh phenotype is associated to more aggressive OD3id rather than an independent prognostic factor.

Finally, our work identifies novel intertumor and intratumor tumor cell heterogeneities in OD3id based on the presence of tumor cells with NIP phenotype. These findings will help the understanding of OD3id biology and open new therapeutic avenues considering neuronal cell lineage.

Funding: This work is funded by the French Institut National du Cancer (INCa) and part of the national program Cartes d'Identité des Tumeurs® (CIT) http://cit.ligue-cancer.net/funded and developed by the Ligue Nationale contre le cancer.

The research leading to these results received fundings from the programs “Investissements d'avenir” ANR‐10‐IAIHU‐06 and ANR‐11‐INBS‐0011 (NeurATRIS: Translational Research Infrastructure for Biotherapies in Neurosciences), from Fondation ARC pour la recherche sur le cancer (n°PJA 20151203562) and from Association pour la Recherche sur les Tumeurs Cérébrales (ARTC).

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web‐site:

Figure S1. RT‐qPCR and immunohistochemistry for lineage markers of central nervous system in anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors. a, schematic representation of embryonic central nervous system lineages. Neural stem cells produce neurons, becomes gliogenic progenitors after the glial switch and then produce oligodendrocytes and astrocytes. b, c, RT‐qPCR in anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors (AOT) with or without 1p/19q co‐deletion, and in control (non tumoral cerebral tissue). b, genes correspond to markers of the different cell types: embryonic stem cells (cyan), NSC (blue), neuronal precursors (green), gliogenic progenitors (yellow), oligodendroglial lineages (orange), and astrocytic lineage (purple). Asterisk correspond to significant Kruskal‐Wallis test for global alpha risk<0,05. c, pairwise comparison by Wilcoxon rank sum test of the level of expression for the markers with significant Kruskal‐Wallis test. *: p <0,05; **: p<0,01; *** p<0,001. d‐f, NFIA immunolabeling in 1p/19q co‐deleted and non 1p/19q codeleted AOT. Nuclear labeling (brown) of few cells in 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT (D) and of most of the cells in non 1p/19q codeleted AOT (e). f, quantification of the ratio of NFIA immunolabeled tumor cells. 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT have significantly lower ratio than non 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT, p=0.0007, t test. A threshold of 50% NFIA positive tumor cells predicted 1p/19q co‐deletion with sensibility 89% and specificity of 92% in n=33 AOT. Abbreviations. APC: astrocyte precursor cell, 1p/19q co‐del.: 1p/19q co‐deletion, ESC: embryonic stem cell, gliogenic prog.: gliogenic progenitors, NIP: neuronal intermediate progenitors, NP: neuronal precursor, NSC: neural stem cells, OPC: oligodendrocyte progenitor cell.

Figure S2. Internexin alpha immunolabeling. Internexin alpha (INA) immunolabeling was positive in adult human neurons (a, c), negative in adult human oligodendrocytes (b, d). e, f, double immunolabeling of INA and OLIG2 showed that oligodendrocytes are OLIG2 positive and INA negative. Embryonic murine neuronal precursors (g) showed INA immunolabeling as a dot (arrowhead in g) similarly to some tumor cells of 1p/19q co‐deleted anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors (arrowhead in h).

Figure S3. Murin homologs of genes frequently mutated in 1p/19q co‐deleted oligodendroglial tumors are expressed in the embryonic subventricular zone. a‐f, in situ hybridization on sagittal sections were retrieved from: (i) Genepaint (Visel et al, 2004), (ii) Allen Brain Atlas (©2012 Allen Institute for Brain Science. Allen Developing Mouse Brain Atlas [Internet]. Available from: http://developingmouse.brain-map.org), and (iii) Brain Gene Expression Map (http://www.stjudebgem.org) (Magdaleno et al, 2006). Sections are shown with rostral on the left, dorsal on the top, ventricular zone (solid arrowhead) and subventricular zone (open arrowhead) for Cic (a), Olig2 (b), Notch2 (c), Tcf12 (d), Fubp1 (e) and Cux2 (f). Olig2 and Cux2 are shown to localize the subventricular zone. Cic, Notch2, Fubp1 and Tcf2 were expressed in embryonic subventricular zone. g, level and expression pattern of genes shown in a‐f are summarized with gray scale (low expression in light grey and high expression in dark grey). Abbreviations: svz, subventricular zone; vz, ventricular zone.

Figure S4. Lineage signature expression according to 1p/19q co‐deletion status in anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors of the validation series. a, schematic representation of embryonic central nervous system lineages. Neural stem cells produce neurons, becomes gliogenic progenitors after the glial switch and then produce oligodendrocytes and astrocytes. b, Normalized Enrichment Score obtained by Gene Set Enrichment analysis for cell lineage signatures is presented by a color scale. Abbreviations. APC: astrocyte precursor cell, codel.1p/19q: co‐deletion 1p/19q, ESC: embryonic stem cell, gliogenic prog.: gliogenic progenitors, NES: Normalized Enrichment Score, NIP: neuronal intermediate progenitors, NP: neuronal precursor, NSC: neural stem cells, OPC: oligodendrocyte progenitor cell.

Figure S5. Hierarchical clustering of anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors of the validation series. a, tumors were clustered according to the differential expression of genes of the gliogenic progenitor signature and neuronal intermediate progenitor signature. Columns correspond to tumors and lines correspond to genes. NIPhigh subgroup corresponded to 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT clustering together with higher expression of NIP genes. NIPlow subgroup corresponded to other 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT. b, histology and molecular of each tumor is indicated. Abbreviations: A3, IDH‐mutant: anaplastic astrocytoma, IDH‐mutant; GBM, IDH‐mutant: glioblastoma, IDH‐mutant; GBM, IDH‐wildtype: glioblastoma, IDH‐wildtype; OA3, anaplastic oligo‐astrocytoma; OA3, NOS: anaplastic oligo‐astrocytoma, NOS; O3id: integrated diagnosis of anaplastic oligodendroglioma, IDH‐mutant and 1p/19q co‐deleted; OD3, anaplastic oligodendroglioma.

Figure S6. INSM1 immunolabeling in nontumor and tumor human tissues. INSM1 immunolabeling was negative in adult human cerebral cortex (a) and white matter (b). It was diffusely positive as a nuclear staining in medulloblastoma (c), and neuroendocrine carcinoma (d).

Figure S7. a, schema of the fetal cerebral cortex. Neural stem cells in the ventricular zone (VZ) produce neuronal intermediate progenitor (NIP) which migrate to the subventricular zone (SVZ). NIP proliferate and produce neuronal precursor which migrate through the intermediate zone (IZ) to the cortical plate (CP). In the CP, neuronal precursors differentiate into neurons. INSM1 is expressed in NIP. SOX11 and ELAVL2 are expressed from NIP to neurons. b, SOX11 immunolabeling of the human fetal cerebral cortex at 13 gestation week showed prominent expression in the SVZ containing NIP (c), and maintained expression in neuronal precursor of IZ and neurons of CP (d). Scarce SOX11 immunolabeling in adult white matter (e) and cerebral cortex (f). Weak ELAVL2 immunolabeling in adult white matter glial cells (g) and high expression in adult cerebral cortex neurons (h). i, high expression of SOX11 in a NIPhigh tumor. j, expression score of SOX11 was non significantly higher in NIPhigh versus NIPlow tumors (p=0.53, Mann‐Whitney). k, high expression of ELAVL2 in a NIPhigh tumor. l, expression score of ELAVL2 was non significantly higher in NIPhigh versus NIPlow tumors (p=0.43, Mann‐Whitney test). m‐o, consecutive sections of a NIPhigh tumor were immunolabeled for INSM1 (m), SOX11 (n) and ELAVL2 (o); some areas of the tumor showed a high co‐expression of INSM1, SOX11 and ELAVL2 (arrowheads in m‐o). Abbreviations: CP: cortical plate, IZ: intermediate zone, SVZ: subventricular zone, VZ: ventricular zone.

Figure S8. Kaplan–Meier survival curves and p value of log‐rank test are shown for the variables: (a) age (nage<45y=38, nage>45y=48), (b) necrosis (nno necrosis=65, nnecrosis=21), (c) microvascular proliferation (nno microvascular proliferation=16, nmicrovascular proliferation=70), and (d) NIPhigh versus NIPlow groups (nNIPhigh=34, nNIPlow=52).

Table S1. List of genes and primers for analysis of gene expression by reverse transcription and PCR.

Table S2. References of gene lists used for GSEA References: (6, 10, 11, 18, 33, 35, 37, 66).

Table S3. Detailed results of GSEA analysis in the training series

Abbreviations. ES, Enrichment Score; NES, Normalized Enrichment Score; NOM p‐val, Nominal p value; FDR q‐val, False Discovery Rate q value; FWER p‐val, Familywise‐error rate p value.

Table S4. Detailed results of GSEA analysis in the validation series

Abbreviations. ES, Enrichment Score; NES, Normalized Enrichment Score; NOM p‐val, Nominal p value; FDR q‐val, False Discovery Rate q value; FWER p‐val, Familywise‐error rate p value.

Table S5. GSEA analysis of NIPhigh versus NIPlow subgroup for Gene Ontology and Oncogenic Signaling in the validation series.

Abbreviations. ES, Enrichment Score; NES, Normalized Enrichment Score; NOM p‐val, Nominal p value; FDR q‐val, False Discovery Rate q value; FWER p‐val, Familywise‐error rate p value.

Table S6. Neuronal Markers expressed in oligodendroglial tumors References: (15, 16, 20, 21, 34, 38, 49, 55, 56, 73, 77, 79, 80).

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Institut Universitaire de Cancérologie (IUC), ONCOMOLPATH (AP‐HP). We are grateful to the staff of Neuropathology Department for technical assistance.

Contributor Information

Ahmed Idbaih, Email: ahmed.idbaih@gmail.com, Email: ahmed.idbaih@aphp.fr.

Pola Network:

Christine Desenclos, Henri Sevestre, Philippe Menei, Audrey Rousseau, Joel Godard, Gabriel Viennet, Antoine Carpentier, Sandrine Eimer, Hugues Loiseau, Phong Dam‐Hieu, Isabelle Quintin‐Roué, Jean‐Sebastien Guillamo, Emmanuelle Lechapt‐Zalcman, Jean‐Louis Kemeny, Toufik Khallil, Dominique Cazals‐Hatem, Thierry Faillot, Ioana Carpiuc, Pomone Richard, Caroline Le Guerinel, Claude Gaultier, Marie‐Christine Tortel, Marie‐Hélène Aubriot‐Lorton, François Ghiringhelli, Clovis Adam, Fabrice Parker, Claude‐Alain Maurage, Carole Ramirez, Edouard Marcel Gueye, François Labrousse, Anne Jouvet, Olivier Chinot, Luc Bauchet, Valérie Rigau, Patrick Beauchesne, Dr Guillaume Gauchotte, Mario Campone, Delphine Loussouarn, Denys Fontaine, Fanny Vandenbos, Claire Blechet, Mélanie Fesneau, Jean Yves Delattre, Selma Elouadhani‐Hamdi, Damien Ricard, Delphine Larrieu‐Ciron, Pierre‐Marie Levillain, Philippe Colin, Marie‐Danièle Diebold, Danchristian Chiforeanu, Elodie Vauléon, Olivier Langlois, Annie Laquerrière, Marie Janette Motsuo Fotso, Michel Peoc'h, Marie Andraud, Gwenaelle Runavot, Marie‐Pierre Chenard, Georges Noel, Dr Stéphane Gaillard, Dr Chiara Villa, Nicolas Desse, Elisabeth Cohen‐Moyal, Emmanuelle Uro‐Coste, and Frédéric Dhermain

References

- 1. Akamatsu W, Okano HJ, Osumi N, Inoue T, Nakamura S, Sakakibara S et al (1999) Mammalian ELAV‐like neuronal RNA‐binding proteins HuB and HuC promote neuronal development in both the central and the peripheral nervous systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:9885–9890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akerstrom V, Chen C, Lan MS, Breslin MB (2013) Adenoviral insulinoma‐associated protein 1 promoter‐driven suicide gene therapy with enhanced selectivity for treatment of neuroendocrine cancers. Ochsner J 13:91–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alentorn A, Marie Y, Carpentier C, Boisselier B, Giry M, Labussiere M et al (2012) Prevalence, clinico‐pathological value, and co‐occurrence of PDGFRA abnormalities in diffuse gliomas. Neuro Oncol 14:1393–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alentorn A, Sanson M, Idbaih A (2012) Oligodendrogliomas: new insights from the genetics and perspectives. Curr Opin Oncol 24:687–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bannykh SI, Stolt CC, Kim J, Perry A, Wegner M (2006) Oligodendroglial‐specific transcriptional factor SOX10 is ubiquitously expressed in human gliomas. J Neurooncol 76:115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beckervordersandforth R, Tripathi P, Ninkovic J, Bayam E, Lepier A, Stempfhuber B et al (2010) In vivo fate mapping and expression analysis reveals molecular hallmarks of prospectively isolated adult neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 7:744–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beier D, Wischhusen J, Dietmaier W, Hau P, Proescholdt M, Brawanski A et al (2008) CD133 expression and cancer stem cells predict prognosis in high‐grade oligodendroglial tumors. Brain Pathol 18:370–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bergsland M, Ramskold D, Zaouter C, Klum S, Sandberg R, Muhr J (2011) Sequentially acting Sox transcription factors in neural lineage development. Genes Dev 25:2453–2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bettegowda C, Agrawal N, Jiao Y, Sausen M, Wood LD, Hruban RH et al (2011) Mutations in CIC and FUBP1 contribute to human oligodendroglioma. Science 333:1453–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boutin C, Hardt O, de Chevigny A, Core N, Goebbels S, Seidenfaden R et al (2010) NeuroD1 induces terminal neuronal differentiation in olfactory neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:1201–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cahoy JD, Emery B, Kaushal A, Foo LC, Zamanian JL, Christopherson KS et al (2008) A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: a new resource for understanding brain development and function. J Neurosci 28:264–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cairncross G, Wang M, Shaw E, Jenkins R, Brachman D, Buckner J et al (2013) Phase III trial of chemoradiotherapy for anaplastic oligodendroglioma: long‐term results of RTOG 9402. J Clin Oncol 31:337–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen C, Lee GA, Pourmorady A, Sock E, Donoghue MJ (2015) Orchestration of neuronal differentiation and progenitor pool expansion in the developing cortex by soxc genes. J Neurosci 35:10629–10642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. De Smaele E, Fragomeli C, Ferretti E, Pelloni M, Po A, Canettieri G et al (2008) An integrated approach identifies Nhlh1 and Insm1 as Sonic Hedgehog‐regulated genes in developing cerebellum and medulloblastoma. Neoplasia 10:89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dehghani F, Maronde E, Schachenmayr W, Korf HW (2000) Neurofilament H immunoreaction in oligodendrogliomas as demonstrated by a new polyclonal antibody. Acta Neuropathol 100:122–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dehghani F, Schachenmayr W, Laun A, Korf HW (1998) Prognostic implication of histopathological, immunohistochemical and clinical features of oligodendrogliomas: a study of 89 cases. Acta Neuropathol 95:493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Deneen B, Ho R, Lukaszewicz A, Hochstim CJ, Gronostajski RM, Anderson DJ (2006) The transcription factor NFIA controls the onset of gliogenesis in the developing spinal cord. Neuron 52:953–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dougherty JD, Fomchenko EI, Akuffo AA, Schmidt E, Helmy KY, Bazzoli E et al (2012) Candidate pathways for promoting differentiation or quiescence of oligodendrocyte progenitor‐like cells in glioma. Cancer Res 72:4856–4868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ducray F, Criniere E, Idbaih A, Mokhtari K, Marie Y, Paris S et al (2009) alpha‐Internexin expression identifies 1p19q codeleted gliomas. Neurology 72:156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ducray F, Idbaih A, de Reynies A, Bieche I, Thillet J, Mokhtari K et al (2008) Anaplastic oligodendrogliomas with 1p19q codeletion have a proneural gene expression profile. Mol Cancer 7:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ducray F, Mokhtari K, Criniere E, Idbaih A, Marie Y, Dehais C et al (2011) Diagnostic and prognostic value of alpha internexin expression in a series of 409 gliomas. Eur J Cancer 47:802–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Farkas LM, Haffner C, Giger T, Khaitovich P, Nowick K, Birchmeier C et al (2008) Insulinoma‐associated 1 has a panneurogenic role and promotes the generation and expansion of basal progenitors in the developing mouse neocortex. Neuron 60:40–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ferletta M, Uhrbom L, Olofsson T, Ponten F, Westermark B (2007) Sox10 has a broad expression pattern in gliomas and enhances platelet‐derived growth factor‐B–induced gliomagenesis. Mol Cancer Res 5:891–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Figarella‐Branger D, Mokhtari K, Dehais C, Carpentier C, Colin C, Jouvet A et al (2016) Mitotic index, microvascular proliferation, and necrosis define 3 pathological subgroups of prognostic relevance among 1p/19q co‐deleted anaplastic oligodendrogliomas. Neuro Oncol 18:888–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Giachino C, Boulay JL, Ivanek R, Alvarado A, Tostado C, Lugert S et al (2015) A tumor suppressor function for notch signaling in forebrain tumor subtypes. Cancer Cell 28:730–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glasgow SM, Laug D, Brawley VS, Zhang Z, Corder A, Yin Z et al (2013) The miR‐223/nuclear factor I‐A axis regulates glial precursor proliferation and tumorigenesis in the CNS. J Neurosci 33:13560–13568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glasgow SM, Zhu W, Stolt CC, Huang TW, Chen F, LoTurco JJ et al (2014) Mutual antagonism between Sox10 and NFIA regulates diversification of glial lineages and glioma subtypes. Nat Neurosci 17:1322–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hirsch FR, Varella‐Garcia M, Bunn PA, Jr. , Di Maria MV, Veve R, Bremmes RM et al (2003) Epidermal growth factor receptor in non‐small‐cell lung carcinomas: correlation between gene copy number and protein expression and impact on prognosis. J Clin Oncol 21:3798–3807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Horbinski C, Kofler J, Yeaney G, Camelo‐Piragua S, Venneti S, Louis DN et al (2011) Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 analysis differentiates gangliogliomas from infiltrative gliomas. Brain Pathol 21:564–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Houillier C, Wang X, Kaloshi G, Mokhtari K, Guillevin R, Laffaire J et al (2010) IDH1 or IDH2 mutations predict longer survival and response to temozolomide in low‐grade gliomas. Neurology 75:1560–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Javaherian A, Kriegstein A (2009) A stem cell niche for intermediate progenitor cells of the embryonic cortex. Cereb Cortex 19:i70–i77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kamoun A, Idbaih A, Dehais C, Elarouci N, Carpentier C, Letouze E et al (2016) Integrated multi‐omics analysis of oligodendroglial tumours identifies three subgroups of 1p/19q co‐deleted gliomas. Nat Commun 7:11263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kang P, Lee HK, Glasgow SM, Finley M, Donti T, Gaber ZB et al (2012) Sox9 and NFIA coordinate a transcriptional regulatory cascade during the initiation of gliogenesis. Neuron 74:79–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Katsetos CD, Del Valle L, Geddes JF, Aldape K, Boyd JC, Legido A et al (2002) Localization of the neuronal class III beta‐tubulin in oligodendrogliomas: comparison with Ki‐67 proliferative index and 1p/19q status. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 61:307–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kawaguchi A, Ikawa T, Kasukawa T, Ueda HR, Kurimoto K, Saitou M, Matsuzaki F (2008) Single‐cell gene profiling defines differential progenitor subclasses in mammalian neurogenesis. Development 135:3113–3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kessaris N, Fogarty M, Iannarelli P, Grist M, Wegner M, Richardson WD (2006) Competing waves of oligodendrocytes in the forebrain and postnatal elimination of an embryonic lineage. Nat Neurosci 9:173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Khodosevich K, Seeburg PH, Monyer H (2009) Major signaling pathways in migrating neuroblasts. Front Mol Neurosci 2:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Koperek O, Gelpi E, Birner P, Haberler C, Budka H, Hainfellner JA (2004) Value and limits of immunohistochemistry in differential diagnosis of clear cell primary brain tumors. Acta Neuropathol 108:24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kriegstein A, Alvarez‐Buylla A (2009) The glial nature of embryonic and adult neural stem cells. Annu Rev Neurosci 32:149–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Labreche K, Simeonova I, Kamoun A, Gleize V, Chubb D, Letouze E et al (2015) TCF12 is mutated in anaplastic oligodendroglioma. Nat Commun 6:7207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Labussiere M, Idbaih A, Wang XW, Marie Y, Boisselier B, Falet C et al (2010) All the 1p19q codeleted gliomas are mutated on IDH1 or IDH2. Neurology 74:1886–1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lan MS, Russell EK, Lu J, Johnson BE, Notkins AL (1993) IA‐1, a new marker for neuroendocrine differentiation in human lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 53:4169–4171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lariviere RC, Julien JP (2004) Functions of intermediate filaments in neuronal development and disease. J Neurobiol 58:131–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee CJ, Chan WI, Cheung M, Cheng YC, Appleby VJ, Orme AT, Scotting PJ (2002) CIC, a member of a novel subfamily of the HMG‐box superfamily, is transiently expressed in developing granule neurons. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 106:151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liu C, Sage JC, Miller MR, Verhaak RG, Hippenmeyer S, Vogel H et al (2011) Mosaic analysis with double markers reveals tumor cell of origin in glioma. Cell 146:209–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK (2007) WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System, 4th edn. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK (2016) WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System, Revised, 4th update edn. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Makuria AT, Henderson FC, Rushing EJ, Hartmann D‐P, Azumi N, Ozdemirli M (2007) Oligodendroglioma with neurocytic differentiation versus atypical extraventricular neurocytoma: a case report of unusual pathologic findings of a spinal cord tumor. J Neuro‐Oncol 82:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Marucci G, Di Oto E, Farnedi A, Panzacchi R, Ligorio C, Foschini MP (2012) Nogo‐A: a useful marker for the diagnosis of oligodendroglioma and for identifying 1p19q codeletion. Hum Pathol 43:374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Medina I, Carbonell J, Pulido L, Madeira SC, Goetz S, Conesa A et al (2010) Babelomics: an integrative platform for the analysis of transcriptomics, proteomics and genomic data with advanced functional profiling. Nucleic Acids Res 38:W210–W213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, Subramanian A, Sihag S, Lehar J et al (2003) PGC‐1alpha‐responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet 34:267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mrak RE, Yasargil MG, Mohapatra G, Earel J Jr., Louis DN (2004) Atypical extraventricular neurocytoma with oligodendroglioma‐like spread and an unusual pattern of chromosome 1p and 19q loss. Hum Pathol 35:1156–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mudunuri U, Che A, Yi M, Stephens RM (2009) bioDBnet: the biological database network. Bioinformatics 25:555–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mueller W, Lass U, Veelken J, Reuter F, von Deimling A (2006) 45‐year‐old male with symptomatic mass in the frontal lobe. Brain Pathol (Zurich, Switzerland) 16:89–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mukasa A, Ueki K, Matsumoto S, Tsutsumi S, Nishikawa R, Fujimaki T et al (2002) Distinction in gene expression profiles of oligodendrogliomas with and without allelic loss of 1p. Oncogene 21:3961–3968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mut M, G√ºler‐Tezel G, Lopes MBS, Bilginer B, Ziyal I, Ozcan OE (2005) Challenging diagnosis: oligodendroglioma versus extraventricular neurocytoma. Clin Neuropathol 24:225–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Namihira M, Kohyama J, Semi K, Sanosaka T, Deneen B, Taga T, Nakashima K (2009) Committed neuronal precursors confer astrocytic potential on residual neural precursor cells. Dev Cell 16:245–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Perry A, Burton SS, Fuller GN, Robinson CA, Palmer CA, Resch L et al (2010) Oligodendroglial neoplasms with ganglioglioma‐like maturation: a diagnostic pitfall. Acta Neuropathol 120:237–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Perry A, Miller CR, Gujrati M, Scheithauer BW, Zambrano SC, Jost SC et al (2009) Malignant gliomas with primitive neuroectodermal tumor‐like components: a clinicopathologic and genetic study of 53 cases. Brain Pathol 19:81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Perry A, Scheithauer BW, Macaulay RJ, Raffel C, Roth KA, Kros JM (2002) Oligodendrogliomas with neurocytic differentiation. A report of 4 cases with diagnostic and histogenetic implications. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 61:947–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Persson AI, Petritsch C, Swartling FJ, Itsara M, Sim FJ, Auvergne R et al (2010) Non‐stem cell origin for oligodendroglioma. Cancer Cell 18:669–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Reyes‐Botero G, Dehais C, Idbaih A, Martin‐Duverneuil N, Lahutte M, Carpentier C et al (2013) Contrast enhancement in 1p/19q‐codeleted anaplastic oligodendrogliomas is associated with 9p loss, genomic instability, and angiogenic gene expression. Neuro Oncol 16:662–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rousseau A, Nutt CL, Betensky RA, Iafrate AJ, Han M, Ligon KL et al (2006) Expression of oligodendroglial and astrocytic lineage markers in diffuse gliomas: use of YKL‐40, ApoE, ASCL1, and NKX2‐2. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 65:1149–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sahm F, Reuss D, Koelsche C, Capper D, Schittenhelm J, Heim S et al (2014) Farewell to oligoastrocytoma: in situ molecular genetics favor classification as either oligodendroglioma or astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathol 128:551–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Schramm M, Falkai P, Pietsch T, Neidt I, Egensperger R, Bayer TA (1999) Neural expression profile of Elav‐like genes in human brain. Clin Neuropathol 18:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sim FJ, McClain CR, Schanz SJ, Protack TL, Windrem MS, Goldman SA (2011) CD140a identifies a population of highly myelinogenic, migration‐competent and efficiently engrafting human oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Nat Biotechnol 29:934–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Solecki DJ, Liu XL, Tomoda T, Fang Y, Hatten ME (2001) Activated Notch2 signaling inhibits differentiation of cerebellar granule neuron precursors by maintaining proliferation. Neuron 31:557–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Song HR, Gonzalez‐Gomez I, Suh GS, Commins DL, Sposto R, Gilles FH et al (2010) Nuclear factor IA is expressed in astrocytomas and is associated with improved survival. Neuro Oncol 12:122–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Su Z, Zang T, Liu ML, Wang LL, Niu W, Zhang CL (2014) Reprogramming the fate of human glioma cells to impede brain tumor development. Cell Death Dis 5:e1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA et al (2005) Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge‐based approach for interpreting genome‐wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:15545–15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Suzuki H, Aoki K, Chiba K, Sato Y, Shiozawa Y, Shiraishi Y et al (2015) Mutational landscape and clonal architecture in grade II and III gliomas. Nat Genet 47:458–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tanaka Y, Nobusawa S, Yagi S, Ikota H, Yokoo H, Nakazato Y (2012) Anaplastic oligodendroglioma with ganglioglioma‐like maturation. Brain Tumor Pathol 29:221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Vallat‐Decouvelaere AV, Gauchez P, Varlet P, Delisle MB, Popovic M, Boissonnet H et al (2000) So‐called malignant and extra‐ventricular neurocytomas: reality or wrong diagnosis? A critical review about two overdiagnosed cases. J Neuro‐Oncol 48:161–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. van den Bent MJ, Brandes AA, Taphoorn MJ, Kros JM, Kouwenhoven MC, Delattre JY et al (2013) Adjuvant procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine chemotherapy in newly diagnosed anaplastic oligodendroglioma: long‐term follow‐up of EORTC brain tumor group study 26951. J Clin Oncol 31:344–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Vasudevan A, Long JE, Crandall JE, Rubenstein JL, Bhide PG (2008) Compartment‐specific transcription factors orchestrate angiogenesis gradients in the embryonic brain. Nat Neurosci 11:429–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD et al (2010) Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell 17:98–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Vyberg M, Ulhoi BP, Teglbjaerg PS (2007) Neuronal features of oligodendrogliomas–an ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study. Histopathology 50:887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Weigle B, Ebner R, Temme A, Schwind S, Schmitz M, Kiessling A et al (2005) Highly specific overexpression of the transcription factor SOX11 in human malignant gliomas. Oncol Rep 13:139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Wharton SB, Chan KK, Hamilton FA, Anderson JR (1998) Expression of neuronal markers in oligodendrogliomas: an immunohistochemical study. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 24:302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wolf HK, Buslei R, Bl√ºmcke I, Wiestler OD, Pietsch T (1997) Neural antigens in oligodendrogliomas and dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors. Acta Neuropathol 94:436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Yamashita S, Yokogami K, Niibo T, Takeishi G, Ikeda T, Miyata S et al (2011) Oligodendroglial ganglioglioma. Brain Tumor Pathol 28:311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Yung SY, Gokhan S, Jurcsak J, Molero AE, Abrajano JJ, Mehler MF (2002) Differential modulation of BMP signaling promotes the elaboration of cerebral cortical GABAergic neurons or oligodendrocytes from a common sonic hedgehog‐responsive ventral forebrain progenitor species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:16273–16278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zinin N, Adameyko I, Wilhelm M, Fritz N, Uhlen P, Ernfors P, Henriksson MA (2014) MYC proteins promote neuronal differentiation by controlling the mode of progenitor cell division. EMBO Rep 15:383–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web‐site:

Figure S1. RT‐qPCR and immunohistochemistry for lineage markers of central nervous system in anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors. a, schematic representation of embryonic central nervous system lineages. Neural stem cells produce neurons, becomes gliogenic progenitors after the glial switch and then produce oligodendrocytes and astrocytes. b, c, RT‐qPCR in anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors (AOT) with or without 1p/19q co‐deletion, and in control (non tumoral cerebral tissue). b, genes correspond to markers of the different cell types: embryonic stem cells (cyan), NSC (blue), neuronal precursors (green), gliogenic progenitors (yellow), oligodendroglial lineages (orange), and astrocytic lineage (purple). Asterisk correspond to significant Kruskal‐Wallis test for global alpha risk<0,05. c, pairwise comparison by Wilcoxon rank sum test of the level of expression for the markers with significant Kruskal‐Wallis test. *: p <0,05; **: p<0,01; *** p<0,001. d‐f, NFIA immunolabeling in 1p/19q co‐deleted and non 1p/19q codeleted AOT. Nuclear labeling (brown) of few cells in 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT (D) and of most of the cells in non 1p/19q codeleted AOT (e). f, quantification of the ratio of NFIA immunolabeled tumor cells. 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT have significantly lower ratio than non 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT, p=0.0007, t test. A threshold of 50% NFIA positive tumor cells predicted 1p/19q co‐deletion with sensibility 89% and specificity of 92% in n=33 AOT. Abbreviations. APC: astrocyte precursor cell, 1p/19q co‐del.: 1p/19q co‐deletion, ESC: embryonic stem cell, gliogenic prog.: gliogenic progenitors, NIP: neuronal intermediate progenitors, NP: neuronal precursor, NSC: neural stem cells, OPC: oligodendrocyte progenitor cell.

Figure S2. Internexin alpha immunolabeling. Internexin alpha (INA) immunolabeling was positive in adult human neurons (a, c), negative in adult human oligodendrocytes (b, d). e, f, double immunolabeling of INA and OLIG2 showed that oligodendrocytes are OLIG2 positive and INA negative. Embryonic murine neuronal precursors (g) showed INA immunolabeling as a dot (arrowhead in g) similarly to some tumor cells of 1p/19q co‐deleted anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors (arrowhead in h).

Figure S3. Murin homologs of genes frequently mutated in 1p/19q co‐deleted oligodendroglial tumors are expressed in the embryonic subventricular zone. a‐f, in situ hybridization on sagittal sections were retrieved from: (i) Genepaint (Visel et al, 2004), (ii) Allen Brain Atlas (©2012 Allen Institute for Brain Science. Allen Developing Mouse Brain Atlas [Internet]. Available from: http://developingmouse.brain-map.org), and (iii) Brain Gene Expression Map (http://www.stjudebgem.org) (Magdaleno et al, 2006). Sections are shown with rostral on the left, dorsal on the top, ventricular zone (solid arrowhead) and subventricular zone (open arrowhead) for Cic (a), Olig2 (b), Notch2 (c), Tcf12 (d), Fubp1 (e) and Cux2 (f). Olig2 and Cux2 are shown to localize the subventricular zone. Cic, Notch2, Fubp1 and Tcf2 were expressed in embryonic subventricular zone. g, level and expression pattern of genes shown in a‐f are summarized with gray scale (low expression in light grey and high expression in dark grey). Abbreviations: svz, subventricular zone; vz, ventricular zone.

Figure S4. Lineage signature expression according to 1p/19q co‐deletion status in anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors of the validation series. a, schematic representation of embryonic central nervous system lineages. Neural stem cells produce neurons, becomes gliogenic progenitors after the glial switch and then produce oligodendrocytes and astrocytes. b, Normalized Enrichment Score obtained by Gene Set Enrichment analysis for cell lineage signatures is presented by a color scale. Abbreviations. APC: astrocyte precursor cell, codel.1p/19q: co‐deletion 1p/19q, ESC: embryonic stem cell, gliogenic prog.: gliogenic progenitors, NES: Normalized Enrichment Score, NIP: neuronal intermediate progenitors, NP: neuronal precursor, NSC: neural stem cells, OPC: oligodendrocyte progenitor cell.

Figure S5. Hierarchical clustering of anaplastic oligodendroglial tumors of the validation series. a, tumors were clustered according to the differential expression of genes of the gliogenic progenitor signature and neuronal intermediate progenitor signature. Columns correspond to tumors and lines correspond to genes. NIPhigh subgroup corresponded to 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT clustering together with higher expression of NIP genes. NIPlow subgroup corresponded to other 1p/19q co‐deleted AOT. b, histology and molecular of each tumor is indicated. Abbreviations: A3, IDH‐mutant: anaplastic astrocytoma, IDH‐mutant; GBM, IDH‐mutant: glioblastoma, IDH‐mutant; GBM, IDH‐wildtype: glioblastoma, IDH‐wildtype; OA3, anaplastic oligo‐astrocytoma; OA3, NOS: anaplastic oligo‐astrocytoma, NOS; O3id: integrated diagnosis of anaplastic oligodendroglioma, IDH‐mutant and 1p/19q co‐deleted; OD3, anaplastic oligodendroglioma.

Figure S6. INSM1 immunolabeling in nontumor and tumor human tissues. INSM1 immunolabeling was negative in adult human cerebral cortex (a) and white matter (b). It was diffusely positive as a nuclear staining in medulloblastoma (c), and neuroendocrine carcinoma (d).

Figure S7. a, schema of the fetal cerebral cortex. Neural stem cells in the ventricular zone (VZ) produce neuronal intermediate progenitor (NIP) which migrate to the subventricular zone (SVZ). NIP proliferate and produce neuronal precursor which migrate through the intermediate zone (IZ) to the cortical plate (CP). In the CP, neuronal precursors differentiate into neurons. INSM1 is expressed in NIP. SOX11 and ELAVL2 are expressed from NIP to neurons. b, SOX11 immunolabeling of the human fetal cerebral cortex at 13 gestation week showed prominent expression in the SVZ containing NIP (c), and maintained expression in neuronal precursor of IZ and neurons of CP (d). Scarce SOX11 immunolabeling in adult white matter (e) and cerebral cortex (f). Weak ELAVL2 immunolabeling in adult white matter glial cells (g) and high expression in adult cerebral cortex neurons (h). i, high expression of SOX11 in a NIPhigh tumor. j, expression score of SOX11 was non significantly higher in NIPhigh versus NIPlow tumors (p=0.53, Mann‐Whitney). k, high expression of ELAVL2 in a NIPhigh tumor. l, expression score of ELAVL2 was non significantly higher in NIPhigh versus NIPlow tumors (p=0.43, Mann‐Whitney test). m‐o, consecutive sections of a NIPhigh tumor were immunolabeled for INSM1 (m), SOX11 (n) and ELAVL2 (o); some areas of the tumor showed a high co‐expression of INSM1, SOX11 and ELAVL2 (arrowheads in m‐o). Abbreviations: CP: cortical plate, IZ: intermediate zone, SVZ: subventricular zone, VZ: ventricular zone.

Figure S8. Kaplan–Meier survival curves and p value of log‐rank test are shown for the variables: (a) age (nage<45y=38, nage>45y=48), (b) necrosis (nno necrosis=65, nnecrosis=21), (c) microvascular proliferation (nno microvascular proliferation=16, nmicrovascular proliferation=70), and (d) NIPhigh versus NIPlow groups (nNIPhigh=34, nNIPlow=52).

Table S1. List of genes and primers for analysis of gene expression by reverse transcription and PCR.

Table S2. References of gene lists used for GSEA References: (6, 10, 11, 18, 33, 35, 37, 66).

Table S3. Detailed results of GSEA analysis in the training series

Abbreviations. ES, Enrichment Score; NES, Normalized Enrichment Score; NOM p‐val, Nominal p value; FDR q‐val, False Discovery Rate q value; FWER p‐val, Familywise‐error rate p value.

Table S4. Detailed results of GSEA analysis in the validation series

Abbreviations. ES, Enrichment Score; NES, Normalized Enrichment Score; NOM p‐val, Nominal p value; FDR q‐val, False Discovery Rate q value; FWER p‐val, Familywise‐error rate p value.

Table S5. GSEA analysis of NIPhigh versus NIPlow subgroup for Gene Ontology and Oncogenic Signaling in the validation series.

Abbreviations. ES, Enrichment Score; NES, Normalized Enrichment Score; NOM p‐val, Nominal p value; FDR q‐val, False Discovery Rate q value; FWER p‐val, Familywise‐error rate p value.

Table S6. Neuronal Markers expressed in oligodendroglial tumors References: (15, 16, 20, 21, 34, 38, 49, 55, 56, 73, 77, 79, 80).

Supporting Information