Abstract

Levels of cerebral amyloid, presumably β‐amyloid (Abeta), toxicity and the incidence of cortical and subcortical ischemia increases with age. However, little is known about the severe pathological condition and dementia that occur as a result of the comorbid occurrence of this vascular risk factor and Abeta toxicity. Clinical studies have indicated that small ischemic lesions in the striatum are particularly important in generating dementia in combination with minor amyloid lesions. These cognitive deficits are highly likely to be caused by changes in the cortex. In this study, we examined the viability and morphological changes in microglial and neuronal cells, gap junction proteins (connexin43) and neuritic/axonal retraction (Fer Kinase) in the striatum and cerebral cortex using a comorbid rat model of striatal injections of endothelin‐1 (ET1) and Abeta toxicity. The results demonstrated ventricular enlargement, striatal atrophy, substantial increases in β‐amyloid, ramified microglia and increases in neuritic retraction in the combined models of stroke and Abeta toxicity. Changes in connexin43 occurred equally in both groups of Abeta‐treated rats, with and without focal ischemia. Although previous behavioral tests demonstrated impairment in memory and learning, the visual discrimination radial maze task did not show significant difference, suggesting the cognitive impairment in these models is not related to damage to the dorsolateral striatum. These results suggest an insight into the relationship between cortical/striatal atrophy, pathology and functional impairment.

Keywords: axonal retraction, beta‐amyloid, cellular degeneration, infarct, microgliosis

Introduction

Focal ischemia in different parts of the brain leads to transient accumulation and increased β‐amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing in the regions adjacent to the periphery of ischemic lesion and white matter, including the cortex 1, 23, 36, suggesting an interplay between ischemia and β‐amyloid pathology. Similarly, an increasing number of epidemiological studies indicate that cerebral ischemia significantly increases the risk of, potentially preventable, vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) or poststroke dementia, including dementia of the Alzheimer type 18, 56. It is not known whether this is caused by unmasking of preexisting Alzheimer's disease (AD) or development of new AD lesions, where β‐amyloid (Aβ) appears to play a critical role in neurotoxicity. These observations emphasize the need to identify overlapping molecular mechanisms associated with combinations of cerebral ischemia and VCI or dementia related to β‐amyloid pathology. In this regard, a study carried out in 1997 demonstrated that the comorbid occurrence of subcortical lacunar infarcts and AD lesions resulted in significantly more dementia compared with either condition alone as well as with cortical infarcts and AD lesions 43. The validity of this concept was confirmed in a population study 12. In some familial forms of AD, Aβ deposition starts in striatum 22 as well as ventral striatum is the brain region that showed Aβ deposition early in AD pathology in in vivo β‐amyloid imaging 22. Such infarcts can precipitate the development of AD 43, 49. Subjects with a given density of cortical neurofibrillary tangles have lower cognitive performance in the presence of infarcts, and this effect is even more marked for small lacunar than large hemispheric infarcts 16, 43.

We have previously conducted studies to examine the combined effect of striatal ischemia and β‐amyloid toxicity on neuroinflammation, β‐amyloid and tau accumulation, behavioral changes 53, and ischemia size 52. More recently, we have provided mechanistic insight into the relationship between hippocampal pathology and progenitor cells and function 5. In addition, these previous investigations have provided some important insight that has been used to guide clinical studies using positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, which suggests that following stroke, cortical amyloid and white matter inflammation independently contribute to impaired cognition 45. However, it is expected that the extensive connectivity of the striatum with the neocortex would result in substantive changes in this latter site, as there has been little attention paid to the changes that might be occurring in the neocortex as a consequence of striatal ischemia and β‐amyloid toxicity. Therefore, our working hypothesis is that mimicking the clinical condition of combined striatal infarcts and β‐amyloid toxicity will lead to exacerbated neuroinflammation and accumulation of APP fragments in both cortical and striatal regions of the brain, with evidence of cell‐injury, faulty cell‐to‐cell communication and axonal growth in the neocortex. Hence, in the present investigation we examined changes in the striatum and the neocortex in the combined model of cerebral ischemia and β‐amyloid toxicity to determine the relationship between microglia, cells displaying high levels of APP proteolytic fragments, degeneration, connexin43 gap junction protein involved in intercellular communication and the extent of neuritic retraction as depicted by the high levels of Fer Kinase. In addition, exploration of behavioral impairments has also been limited to hippocampus and cortical tasks, and not included tasks related to lesions in the dorsolateral striatum 26, 27, 32 that was also performed.

Materials and Methods

Animal, treatment and tissue preparation

All animal protocols were carried out according to the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Western University (approval ID: 2008‐113). Male Wistar rats (250 g to 310 g—) were anesthetized using sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg, i.p., Ceva, Sante Animale, Montreal, Canada). The animals were positioned in a stereotaxic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA) with the incisor bar below the interaural line, set at 3.3 mm. Body temperatures were maintained at 37°C. To insert the stainless steel cannula (30‐gauge), small burr holes were drilled in the parietal bone. There were four groups of animals (n = 4–7 for each group). To model striatal ischemia (ET1 group), a single injection of 6 pmol endothelin‐1 (ET1; Sigma‐Aldrich, Oakville, ON, Canada) per 3 μL (dissolved in saline) was made into the right striatum through the cannula (anterior/posterior: +0.5 mm, medial/lateral: −3.0 mm relative to bregma, and dorsoventral: −5.0 mm below dura). The rat model of β‐amyloid toxicity (Aβ group) is well established 10, 41. Briefly, Aβ25‐35 peptide (Bachem, Torrance, CA, USA) at 50 nmol/10 μL dissolved in saline was injected into the lateral ventricles bilaterally (anterior/posterior: −0.8 mm, mediolateral: ±1.4 mm relative to bregma, and dorsoventral: −4.0 mm below dura). This model of β‐amyloid toxicity has been chosen because the toxic fragment, Aβ25‐35, has been found in AD brains 21, 24 and shown in more than a number of in vivo 10, 41, 53 and in vitro 6 studies to be a trigger of neurodegeneration, neuroinflammation with reactive astrocytosis and cognitive deficits [reviewed in 20]. A further advantage of using Aβ25‐35 is to induce modest pathological changes that can be combined with a small ischemia model to examine the interactions. For rats receiving both bilateral intracerebroventricular (ICV) Aβ25‐35 injections and unilateral ET1 injections (Aβ+ET1 group), the Aβ25‐35 peptide injection into the lateral ventricles was followed by the ET1 injection into the striatum. The sham rats (SHAM group) received all the surgical steps without injections of Aβ25‐35 or ET1. Paxinos and Watson 34 atlas was used to determine all stereotaxic coordinates. Following ET1, Aβ25‐35 or saline injections, the cannula was left in situ for 3 minutes before removing slowly. After suturing the wound, all rats received subcutaneous injection of 30 μg/kg buprenorphine and an intramuscular injection of 20 μL (50 mg/mL stock) enrofloxacin antibiotic (Baytril, Bayer Inc., Toronto, Canada) and were subsequently allowed to recover from surgery. Three weeks after surgery, all the animals were euthanized by an overdose (160 mg/kg) of pentobarbital i.p. injection and transaortically perfused, first with heparinized phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4). The brains were removed, postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, and cryoprotected by immersion in 30% sucrose for 36 h at 4°C. Animals for western blotting were sacrificed by cervical decapitation, brains were removed immediately and snap‐frozen by immersing in liquid nitrogen. Fresh frozen brains were kept at −80°C until used for biochemical studies.

Histology

Immunohistochemistry was performed on serial, coronal sections of the entire brain, 35‐μm in thickness using a sliding microtome (Tissue‐Tek® Cryo3® Microtome/Cryostat, Sakura Finetek, CA, USA) for cryoprotected brains. Sections were then stained with antibodies against ramified microglia (OX‐6, BD Pharmingen, Mississauga, Canada, 554926, 1:1000), APP, Abeta and its fragment 17‐24 (4G8, Signet, Covance, Emeryville, CA, USA, 9220‐10), neuron‐specific nuclear protein (NeuN, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA, MAB377, 1:200) and the gap junction protein connexin43 (Cx43; Sigma‐Aldrich, C6219, 1:600). Briefly, parallel series of free‐floating, cryoprotected sections were incubated with 1% H2O2 in 0.1 M PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature, with serum in 0.1 M PBS for 1 h at room temperature, with primary antibodies in 0.1 M PBS for 24 h at 4°C, with biotin‐conjugated secondary antibodies [OX‐6 and Aβ; horse anti‐mouse (BA‐2000)] in 0.1 M PBS for 1 h at room temperature, with 2% of avidin–biotin complex (ABC) in 0.1 M PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, sections were incubated with 0.05% 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB; Sigma) and 50 μL of 1% H2O2 for 15 minutes at room temperature. After each incubation step, sections were washed with 0.1 M PBS four times for 5 minutes each. Finally, all sections were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol and cleared in xylene before cover slipping with Depex (Depex, BDH Chemicals, Poole, UK). Serums, ABC reagent and biotinylated antibodies were from the Vectastain Elite ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA). Negative controls included all histological procedures with no primary antibody added.

FluoroJade B (FJB) staining

Sections were mounted on gelatin‐coated glass slides, air‐dried, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol and placed in 0.06% potassium permanganate solution for 15 minutes before rinsing in distilled water. Next, sections were placed in 0.0004% FJB (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA) solution for 20 minutes, rinsed in distilled water, cleared in xylene and cover slipped using Depex.

Quantitative western blotting

Detergent‐resistant cortical membranes were isolated based on their insolubility in TritonX‐100 at 4°C and their ability to float in sucrose density gradients. Fresh frozen brain cortices from both hemispheres were homogenized in 1.0 mL of PTN 50 buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X‐100, 50 mM NaCl) containing 10 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 5 μg leupeptin and 1 μg pepstatin A, and centrifuged at 12 000 rpm for 10 minutes to remove insoluble material. The remaining supernatant was diluted with equal volumes of 80% sucrose. Samples were carefully overlaid with equal volumes of 30% and 5% sucrose, respectively. The gradient was centrifuged at 130 000 × g (average) for 20 h at 4°C in a Beckman L8‐70 Ultracentrifuge (SW40‐400 rotor; Beckman Coulter, Mississauga, Canada) and aliquoted into 600‐μL fractions. Membrane raft‐containing fractions were tracked by the enrichment of the dendritic membrane raft marker flotillin‐1 (BD Biosciences Mississauga, Canada, 610820, 1:1000) using sodium dodecyl sulphate‐western blotting. Raft‐containing and raft‐free fractions were pooled, concentrated using Amicon Ultra‐4 centrifugal filters (Millipore) and probed with anti‐Fer Kinase (Abcam, Abcam, Toronto, Canada, ab79573, 1:1000). Data analysis was performed using the Molecular Analyst II densitometric software (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Cognitive testing

A subset of 40 animals (10 rats/group) underwent testing in the Morris water maze, discriminative fear‐conditioning to context task and visual discrimination radial maze tasks. While the methods and results of the Morris water maze and discriminative fear‐conditioning to context tasks have been described recently 5, this paper describes only the visual discrimination radial maze task. The apparatus for visual discrimination radial maze task was the same as used previously 33. Briefly, an eight‐arm radial maze elevated 60 cm from the floor with a 40‐cm diameter center platform and 60 cm × 9 cm arms were used. Small light bulbs were affixed on the inner side of each arm and a food cup was located at the end of each arm in the floor of the arm. The maze was in a 305 cm × 216 cm room illuminated underneath by a lamp. Following all behavioral testing, the eight‐arm radial maze was wiped clean with detergent and water. Animals were food‐deprived to 90% of their body weight for 7 days before testing. All feeding was conducted after behavioral testing. Pre‐exposure: Animals were allowed to freely roam the eight‐arm radial maze for 10 minutes. All arms were open and no food reward was present at any food cups located at the ends of the arms. Visual discrimination task: All arms of the maze remained open throughout testing. Animals were trained for 21 consecutive days. Animals were given 10 minutes to complete the training trial. A trial consisted of placing the animal in the middle of the maze facing the east. A light at the end of the arm indicated a food cup containing a food reward (ie, baited). If an animal entered a baited arm and ate the reward, the light was turned off. The number of entered arms as well as total time spent in the maze was recorded. If an animal ate all food rewards, they were promptly removed from the radial maze. If they reached the 10‐minute mark without eating all the food rewards, they were removed from the apparatus and returned to their home cage. Four out of eight arms were baited with food every day, and the determination of which arms were baited each day was randomly assigned.

Analyses

Data analyses were done blindly and with adequate allocation concealment. Histological analyses of brain sections were carried out under light and fluorescence microscopy. Photomicrographs were taken using a Leica Digital Camera DC 300 (Leica Microsystems Ltd., Heerbrugg, Switzerland) attached to Leitz Diaplan Microscope. Digitized images acquired using a 10× objective were saved as TIFF files with an identical level of sharpness and contrast using the IM50 software. The striatum volumes were determined on histological sections using the Image J (version 4.11b, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) by tracing the striatal area quantification plug‐in analysis tool on the computer screen. The volumes (mm3) were calculated by integrating the corresponding areas with the interval thickness of sections. Cells were counted within the entire striatum and neocortex. Ten sections were studied from each brain, taken from the anterior to posterior levels (1.7 to −3.14 from the bregma) with intervals of 144 μm. Cellular densities on each of the 10 slices (expressed as the number of stained cells per mm2 in the optical field) were calculated as the arithmetic mean number of cells in the ipsilateral hemispheres for each animal. The results were displayed as the numbers of stained cells per millimeter of each region analyzed.

Statistical analyses

All values were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Volumetric measurements were analyzed by one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and/or Student's unpaired two‐tailed t‐tests. Number of Aβ, OX6, Cx43, FJB‐labeled cells, behavioral task and Fer Kinase densitometric levels were analyzed using one‐way ANOVA, followed by post hoc Tukey's (β‐amyloid, OX6, Cx43, FJB, visual discrimination radial maze) and Dunnett's (Fer K) tests. The significance level was P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Striatal atrophy and pathology

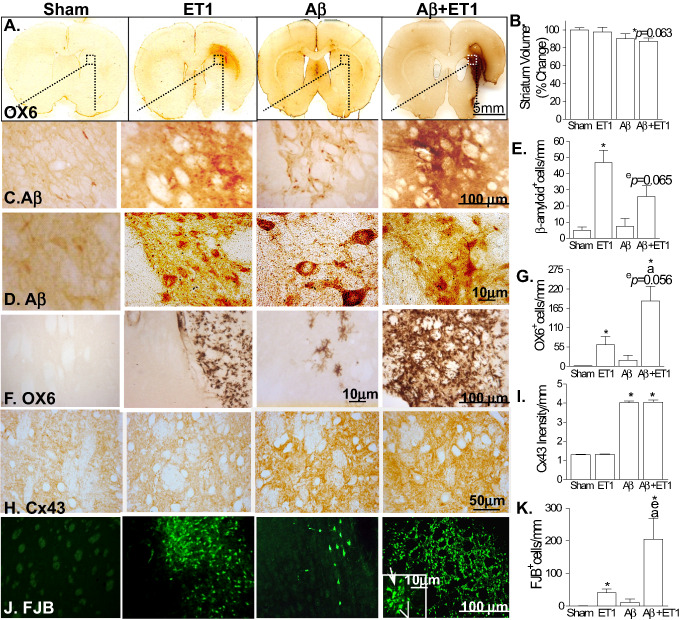

The combined Aβ+ET1 rats exhibited several hallmark features indicative of a degenerating brain. First, in coronal tissue sections (Figure 1A), there was evidence of forebrain lateral ventricle enlargement of Aβ+ET1 rat brains in comparison to those of sham, ET1 and Aβ rats, as shown by us recently 5, which was closely accompanied by tissue loss in the striatum of the Aβ+ET1 rats (12.7% ± 3.6%) (Figure 1B). In addition, the area of inflammation associated with the infarct, as measured with the OX6 staining, was also increased in Aβ+ET1 rats compared with ET1 alone.

Figure 1.

Striatal atrophy and pathology: representative coronal sections stained with OX6 at the levels of motor cortex show ventricular enlargement, striatal shrinkage and infarct volume in Aβ+ET1 rats compared with sham rats with normal brain morphology (A). High‐resolution immunostaining images indicate cells demonstrating expression of APP fragments including β‐amyloid (C,D), ramified microglia (OX‐6; F), connexin43 (Cx43; H) and degeneration (FJB; J) in the ipsilateral striatum of Aβ+ET1 rats. Inset in F showed high‐resolution FJB positive cells that appeared to be degenerating neurons (line) and microglia (arrow). Plots demonstrate a quantitative analysis of reduction in the volume of ipsilateral striatum (B), β‐amyloid (E), OX6 (G), Cx43 (I) and FJB (K) immunostaining in the ipsilateral striatum across the groups, *,e,a P < 0.05, (*compared with sham, ecompared with ET1, acompared with Aβ).

Bilateral injections of Aβ25‐35 in ET1 and Aβ+ET1 rats have been shown to elevate the deposition of APP fragments including β‐amyloid (Figure 1C–E) 53 in the cells that appear to be small, pyknotic or round‐shaped degenerating neurons. The lower number of Aβ positive neuronal cells in Aβ+ET1 rats also indicates the loss of neurons in these rats compared with ET1 rats alone. The anti‐Aβ antibody (9220‐10; 4G8) used in this study recognizes the 17–24 amino acids of Aβ peptide, which is different from the Aβ (25‐35) sequence of the injected β‐amyloid peptide.

The OX6 staining showed reliable demarcation of the infarct with a significant increase in the number of microglial cells mostly concentrated in the ipsilateral dorsolateral striatum of ET1 and Aβ+ET1 rat brains compared with sham and Aβ rats, significantly more in the Aβ+ET1 brains than in the ET1 group. The majority of the OX6 positive cells found in striatum showed highly ramified structures (Figure 1F,G). Cx43 immunostaining increased bilaterally in both the Aβ and Aβ+ET1 rats but did not show any increased staining in the ET1 rats compared with sham (Figure 1H,I).

To examine the cellular degeneration, we used FJB (polyanionic fluorescein derivative) that has been shown to stain injured neurons as a result of acute insult 39, although it could also label astrocytes and microglia 11 during a chronic neurodegenerative process. We found significant numbers of FJB+ degenerative cells with a distinct microglial and neuronal morphology surrounding the ischemic lesion at the motor cortex level and lateral ventricles at the somatosensory cortex level in the ipsilateral striatum in ET1 and Aβ+ET1 rat brains, significantly more in the Aβ+ET1 brains than in the ET1 group (Figure 1J,K). It is important to note that identical brain regions showed dense staining for ramified microglial cells (OX6 stain), indicating that 21 days after the insult most of the microglial cells were at the verge of degeneration. Nevertheless, a small proportion of FJB+ cells in the injured striatum, according to their morphology, appeared to be degenerating neurons (inset—white line). Sham brains, contralateral striatum and Aβ rats did not show any significant staining for FJB.

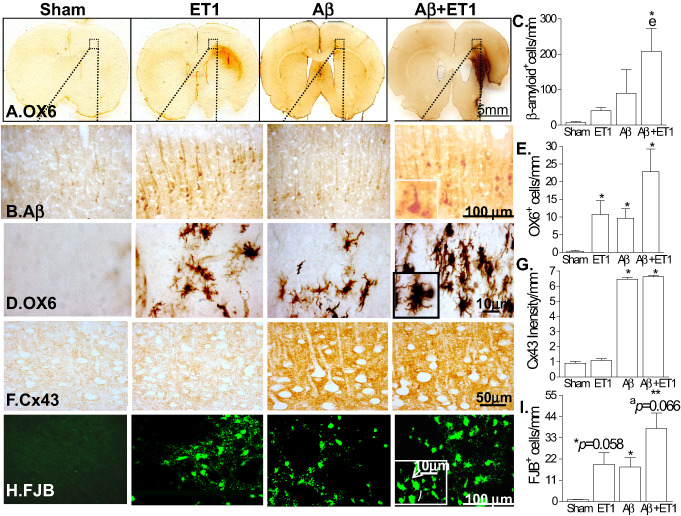

Cortical pathology

In the animals with only ishemia (ET1), there were increased numbers of Aβ, OX6 and FJB positive cells at the levels of motor and somatosensory cortices, close to layer VI compared with sham rats (Figure 2). Rats with Aβ alone showed a significant increase in OX6, Cx43 and FJB staining at the level of somatosensory cortex (Figure 2A–I). The combination of Aβ toxicity and ischemia (Aβ+ET1) showed an overall cortical increase (than both Aβ and ET1) in APP fragments (including β‐amyloid) in cells with typical neuronal morphology (inset) (Figure 2B,C), as well as increases in OX6 staining in ramified microglial cells with stout cell bodies (inset) (Figure 2D,E) and Cx43 (Figure 2F,G), and finally FJB staining in both microglial (inset—arrow) and neuronal (inset—line) cells (Figure 2H,I).

Figure 2.

Cortical pathology: the low‐magnification images of rat brain sections stained with OX6 in A illustrate the location of the high‐magnification photomicrographs in B–E. Immunostaining indicates cells demonstrating expression of APP fragments (including β‐amyloid; B), ramified microglia (OX‐6; C), connexin43 (Cx43; D) and degeneration (FJB; E) in the ipsilateral neocortex of Aβ+ET1 rats. Insets showed high‐resolution images of β‐amyloid expressing neuronal (B), ramified microglial (C) and FJB positive cells (E) that appeared to be degenerating neurons (E; line) and microglia (E; arrow). Plots in F–I show quantitative analysis of immunostaining in the ipsilateral cortex across the groups, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, (*compared with sham, ecompared with ET1, acompared with Aβ).

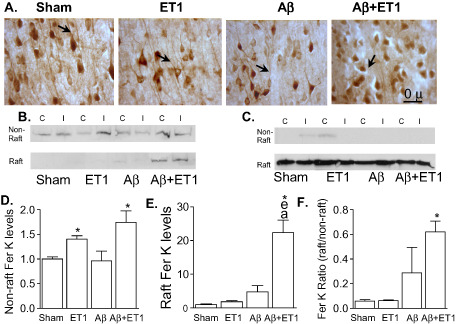

Axonal and dendritic changes

A feature of pathogenesis in degenerating brains such as AD, includes axonal and dendritic atrophy 47. For these reasons, we investigated changes in neuronal morphology (NeuN) and Fer tyrosine kinase (Fer Kinase) in the cortex. Fer kinase is an early marker for axonal retraction and degeneration 40. Although, NeuN is not primarily used as a marker of neuronal retraction, we did observe an apparent decrease in the length of neuronal processes (arrows) of typical pyknotic neurons in the ipsilateral cortex of Aβ+ET1 rats compared with morphologically intact neurons in sham rats (Figure 3A). This apparent decrease in the length of neuronal processes observed with the NeuN staining was consistent with the results of the immunoblots of Fer Kinase that showed bilaterally increased expression in both non‐raft (Figure 3B,D) and raft (Figure 3B,E) domains of Aβ+ET1 rat brains compared with sham, ET1 and Aβ rats. The membrane raft marker flotillin‐1 was used to verify raft membrane fractions (Figure 3C). Non‐raft Fer Kinase levels within the ipsilateral cortex of ET1 rats were also increased (Figure 3B,D). Plot F shows a significant difference in the ratio between raft and non‐raft Fer Kinase protein in the Aβ+ET1 rat brains compared with sham (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Axonal retraction: immunostaining of neurons (NeuN) appears to show pyknosis and empty space around shrunken cell bodies and a decrease in the length of neuronal processes (arrows) in the layer V of ipsilateral cortex of Aβ+ET1 rats (A). Western blots show levels of Fer kinase (Fer K) (B) in non‐raft and raft fractions, and flotillin‐1 (C) protein in the raft section of the contralateral (C) and ipsilateral (I) cortices. Plots show quantitative analysis of sham normalized increase in Fer K levels into the ipsilateral non‐raft (D) and raft (E) containing fractions, as well as the ratio of Fer K levels within the raft to non‐raft domains (F) of Aβ+ET1 rats, *P < 0.05, (*compared with sham, ecompared with ET1, acompared with Aβ).

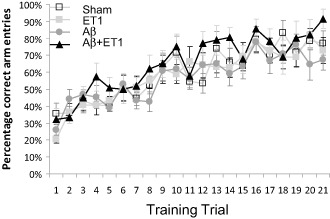

Cognitive testing

The visual discrimination radial maze task primarily requires an intact dorsolateral striatum that is thought to be involved in the acquisition of stimulus–response associations. Our results indicate that all groups demonstrated normal acquisition at the same rate over the course of 21 training days. No differences were observed between any groups (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cognitive impairment: cognitive testing using visual discrimination radial maze task indicates percentage of correct arm entries by sham, ET1, Αβ and Aβ+ET1 rats over the course of 21 training days. Plot shows no differences between any groups.

Abbreviations: Alzheimer's disease (AD), amyloid precursor protein (APP), β‐amyloid (Aβ), intracerebroventricular (ICV), endothelin‐1 ( ET1), phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), avidin–biotin complex (ABC), connexin43 (Cx43), 3,3′‐diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB), fluorojade B (FJB), contralateral (C), ipsilateral (I).

Discussion

The clinical literature presents a compelling argument for the role of vascular insults in potentiating neurodegeneration in vulnerable brains, such as aging individuals with high levels of β‐amyloid and/or those developing Alzheimer's‐type pathologies 8, 15. Previously, we have characterized some critical pathological changes in combined models of β‐amyloid toxicity and ischemia in both transgenic mice 53 and non‐transgenic rat models 5. These models have been particularly effective in helping to determine potential therapeutic agents that might dissociate the additive or synergistic connection between the small focal ischemia and the early pathological events of dementia such as high levels of β‐amyloid and neuroinflammation. The one brain area that is potentially critically important in the cascade of events for the interactions between ischemia and β‐amyloid toxicity is the cerebral cortex and at the site of the infarct in the striatum. This particularly becomes important when, initially, AD emerged as a type of cortical dementia mainly associated with the loss of large pyramidal neurons primarily in the area of associative cortices 35. In the present study we have undertaken a closer look at the changes in the striatum and, in particular, the neocortex in a combined model of β‐amyloid toxicity and small striatal ischemia to further investigate the exacerbated biochemical alterations in this rat model.

On a gross anatomical level, the results indicated that the comorbid occurrence of β‐amyloid toxicity and striatal infarct elicits enlargement in both the lateral ventricles and a trend toward reduction in the volume of the striatum, suggesting there is a loss or degeneration of striatal cells leading to compression or atrophy of the striatum. It has been demonstrated that the progression from mild cognitive impairment to AD is associated with ventricular enlargement and this, in turn, is correlated with senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangle deposition 42, 46.

By investigating several key components, we found a combination of several underlying degenerative effects that might suggest mechanisms that lead to abnormalities in forebrain architecture. The first characteristic finding is a considerably larger increase in cortical and striatal β‐amyloid in the Aβ25‐35 seeded brains in the presence of a relatively small ischemic infarct in the striatum. The increased APP processing and/or endogenous production of β‐amyloid in AβandAβ+ET1 rat brains is likely triggered by Aβ 25‐35 ICV injections or seeding similar to some of the pathological changes we observed in previous studies 5, 10, 50. The high‐hydrophobic amino acids content of Aβ25‐35 and their tendency to aggregate more than the Aβ42 peptide, the neurotoxicity of Aβ25‐35 5, 6, 10, 41, 42, 57 and its presence in the core of senile plaques and extracellular neurofibrillary tangles 24 reinforce its potential involvement in the pathogenesis and etiology of AD. This additional Aβ production could be either caused by the overexpression of APP in neurons (as shown by us), astrocytes or ramified microglia 6, 37. However, what remains to be determined is the mechanism by which Aβ25‐35 trigger leads to a greatly enhanced initial increase in β‐amyloid following the striatal infarct.

The second characteristic change that we identified was a large increase in the density of ramified microglial cells and possibly an upregulation of inflammatory mediators in ET1and Aβ+ET1 rat brains in the striatum and neocortex. This neuroinflammatory change is yet another common feature of neurodegenerative pathologies and ischemic lesions 3. This observation is in accordance with AD hallmarks, as Aβ peptides‐induced toxicity, proinflammatory mediators 37 and deposition of diffuse plaques in the AD brain 2, 19 have been shown to induce microglial activation. ET1 is a potent activator of microglia 25 and can cause prominent microglial staining in rats receiving only ET1. After the elimination of cell debris, in the remodeled adult brain, phagocytic microglial cells rapidly transform into a ramified microglial state 4, 44. Large numbers of these ramified microglia are what we observe at the site of inflammation in the ET1and Aβ+ET1 rat brains in both the striatum and even more significantly in the neocortex, which could partly explain the formation of dementia observed clinically when these two conditions coexist.

The third characteristic change we observed was an elevation in Cx43 immunoreactivity in Aβand Aβ+ET1 rat brains. Interestingly, the addition of ischemia to Aβ25‐35 injections resulted in no additional increase in Cx43, suggesting that changes in these gap junction proteins may not be part of the mechanism related to the interaction of ischemia and β‐amyloid toxicity. Microglial activation promotes the release of glutamate and ATP through astrocytic Cx43 hemichannels, which then can have detrimental effects on neuronal survival 31. However, in our experiments, the Cx43 elevation in both Aβ groups and Aβ+ET1 rat brains is probably independent of microglial activation as it was absent in ET1 injection alone, which did, in fact, have prominent microglial activation. Thus, in these experiments it appears that increased Cx43 expression must be attributed to the direct effect of Aβ25‐35 injection and not mediated by microglia activation. Cx43 has been co‐localized with β‐amyloid plaques in the brains of AD patients 29 and transgenic mice 28, suggesting a possible remodeling of neuron–astrocyte interactions, which is perhaps the case in the Aβ‐injected animals.

The fourth characteristic change we observed was prominent FJB staining corresponding to cell injury in both the striatum and neocortex. It is likely that the substantial cellular loss in the striatum plays a role in causing the loss of striatal tissue in Aβ+ET1 brains. Ischemic injury and neurodegenerative disorders share common features of cell death, such as a molecularly regulated necrosis 48 and/or caspase‐mediated apoptosis 17. Common molecular pathways bringing together neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration have been described 9, 55, a situation that might be present in ET1, Aβ and Aβ+ET1 rats. Future investigations could be done to establish the direct biochemical connections between the activation of glial cells and caspase‐3 30. and the mechanisms these biochemical connections play in the enhanced pathology in the combined ischemia and β‐amyloid toxicity.

The final characteristic change we observed was an apparent decrease in axonal and dendritic length in the cortex of the combined ischemia and Aβ25‐35‐injected rats. It has been shown that β‐amyloid deposits induce breakage of dendritic and axonal branches in a mouse model of AD 47. Very recently, we have also shown aberrant dendritic morphology in neurons developing from progenitor cells in the hippocampus of Aβ+ET1 rats 5. This effect of β‐amyloid may possibly be involved in altering the appearance of axons and dendrites we observed in the cortical regions of Aβ+ET1 rats, as these rats also had a significant increase in endogenous amyloid. Fer Kinase (Fer K) is not only a marker for neurodegeneration but also leads to neuritic retraction, and is markedly increased during global and focal infarct and during post cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury 53. Domain‐specific bilateral amplification of cortical levels of Fer K into the raft and non‐raft membranes in Aβ+ET1 rats confirmed the histological observation we had shown using NeuN staining that there was an exacerbated abnormal pyknotic neuronal morphology with shrunken cell bodies and surrounding empty spaces, as well as an apparent decrease in the length of neuronal processes in the rats with combined insults. This also suggests that the signaling events occurring within the membrane raft domains, and regulated by Fer K, might be responsible for neuronal cell death observed in Aβ+ET1 rats. In addition to neurodegeneration, Fer K also regulates cytoskeletal organization and membrane‐associated receptor endocytosis 13. Membrane rafts are membrane microdomains that are rich in sphingolipids and cholesterol and are thought to be a clustering point for cellular activity during neurodegeneration 38 and axonal growth 14.

The Aβ+ET1 rats did not demonstrate any impairment in place learning in the visual discrimination learning on the radial maze, a behavioral task that is thought to be mediated via the acquisition of stimulus–response associations and is sensitive to relatively large, bilateral lesions in the dorsolateral striatum 26, 27, 32. Interestingly, Aβ+ET1 rats have shown learning and memory impairment in discriminative fear‐conditioning to context task that is linked to hippocampal dysfunction 5. These rats have also shown progressive deterioration in memory and learning with the Barnes circular maze up to 8 weeks post insult 52. The present investigation did not show any deficit related to the dorsolateral striatum, suggesting that the neural machinery necessary for sensory detection and processing, movement generation, and motivation to drive behavior was intact in these rats, mainly caused by the unilateral striatal lesion sparing the contralateral striatum. A further explanation for the differential behavioral results from these studies is that perhaps the behavioral effects in these rats are primarily caused by the dysfunction of prefrontal cortical circuits, in addition to hippocampus. Support for this possibility comes from a previous study showing a similar pattern of functional effects on the discriminative fear‐conditioning to context task in rats with neurotoxic damage to the ventromedial orbitofrontal cortex 54. Rats with damage to this prefrontal region did not show normal fear responses to the shock vs. the no‐shock context but were able to actively avoid the shock context during the preference test.

In conclusion, our results provide evidence from pathological changes in the striatum and cortex that may be related to the mechanisms responsible for the synergistic or overlapping relationship between a vascular insult such as focal ischemia and β‐amyloid trigger that might lead to full dementia. Our results suggest that the triggering event is Aβ overproduction, leading to neuroinflammation, which when combined with ET1‐induced glial activation, can synergistically lead to neuritic retraction and degeneration of existing neurons in the cortex. This can be compared and contrasted with the events in the hippocampus in which glial activation appears to synergistically lead to degeneration of neurons by reducing the survival of adult‐born neurons, possibly by impairing dendritic development and enhancing axonal retraction of the immature neurons, eventually resulting in functional deficits 5. It is not clear if the 21‐day injury time point following ET1 and/or Aβ+ET1 injections represent the maximum degeneration and thus it will be of interest to assess earlier post injury time points as well as to elucidate if there is a point of no return that determines whether a cortical neuron will eventually die. We do have some insight into this as we have previously shown that the behavioral deficits in the combined model are progressive when examined at 2, 4 and 8 weeks post insult. With a relatively complete characterization of the interaction of ischemia and β‐amyloid toxicity for different brain regions, as well as data indicating that anti‐inflammatories can potentially interrupt this association 51, 53, future experiments can be designed to understand the critical mechanisms that mediate the interation between inflammation and increases in endogenous β‐amyloid in the hippocampus and cortex, not only in these models but others including transgenic models and those with pathology stimulated by β‐amyloid‐derived diffussable ligands (ADDLs) [reviewed in 7].

Acknowledgments

Emerging team grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; R1478A47) to D. F. C. and CIHR Vascular Research fellowship to Z.A. funded this research.

Disclosure Statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Abe K, Tanzi RE, Kogure K (1991) Selective induction of Kunitz‐type protease inhibitor domain‐containing amyloid precursor protein mRNA after persistent focal ischemia in rat cerebral cortex. Neurosci Lett 125:172–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akama KT, Albanese C, Pestell RG, Van Eldik LJ (1998) Amyloid beta‐peptide stimulates nitric oxide production in astrocytes through an NFkappaB‐dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:5795–5800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Akundi RS, Candelario‐Jalil E, Hess S, Hull M, Lieb K, Gebicke‐Haerter PJ, Fiebich BL (2005) Signal transduction pathways regulating cyclooxygenase‐2 in lipopolysaccharide‐activated primary rat microglia. Glia 51:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amtul Z, Hepburn JD (2014) Protein markers to cerebrovascular disruption of neurovascular unit: immunohistochemical and imaging approaches. Rev Neurosci doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2013-0041. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Amtul Z, Nikolova S, Gao L, Keeley RJ, Bechberger JF, Fisher AL et al (2014) Comorbid Abeta toxicity and stroke: hippocampal atrophy, pathology, and cognitive deficit. Neurobiol Aging 35:1605–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bitting L, Naidu A, Cordell B, Murphy GM Jr (1996) Beta‐amyloid peptide secretion by a microglial cell line is induced by beta‐amyloid‐(25‐35) and lipopolysaccharide. J Biol Chem 271:16084–16089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Catalano SM, Dodson EC, Henze DA, Joyce JG, Krafft GA, Kinney GG (2006) The role of amyloid‐beta derived diffusible ligands (ADDLs) in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Top Med Chem 6:597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cechetto DF, Hachinski V, Whitehead SN (2008) Vascular risk factors and Alzheimer's disease. Expert Rev Neurother 8:743–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centonze D, Finazzi‐Agro A, Bernardi G, Maccarrone M (2007) The endocannabinoid system in targeting inflammatory neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci 28:180–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheng G, Whitehead SN, Hachinski V, Cechetto DF (2006) Effects of pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate on beta‐amyloid (25‐35)‐induced inflammatory responses and memory deficits in the rat. Neurobiol Dis 23:140–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Damjanac M, Rioux BA, Barrier L, Pontcharraud R, Anne C, Hugon J et al (2007) Fluoro‐Jade B staining as useful tool to identify activated microglia and astrocytes in a mouse transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res 1128:40–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Esiri MM, Nagy Z, Smith MZ, Barnetson L, Smith AD (1999) Cerebrovascular disease and threshold for dementia in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease. Lancet 354:919–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Geerts H (2004) NC‐531 (Neurochem). Curr Opin Investig Drugs 5:95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guirland C, Suzuki S, Kojima M, Lu B, Zheng JQ (2004) Lipid rafts mediate chemotropic guidance of nerve growth cones. Neuron 42:51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hachinski V, Munoz D (2000) Vascular factors in cognitive impairment—where are we now? Ann N Y Acad Sci 903:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heyman A, Fillenbaum GG, Welsh‐Bohmer KA, Gearing M, Mirra SS, Mohs RC et al (1998) Cerebral infarcts in patients with autopsy‐proven Alzheimer's disease: CERAD, part XVIII. Consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 51:159–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hitomi J, Katayama T, Eguchi Y, Kudo T, Taniguchi M, Koyama Y et al (2004) Involvement of caspase‐4 in endoplasmic reticulum stress‐induced apoptosis and Abeta‐induced cell death. J Cell Biol 165:347–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Honig LS, Tang MX, Albert S, Costa R, Luchsinger J, Manly J et al (2003) Stroke and the risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 60:1707–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hu J, Van Eldik LJ (1999) Glial‐derived proteins activate cultured astrocytes and enhance beta amyloid‐induced glial activation. Brain Res 842:46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kaminsky YG, Marlatt MW, Smith MA, Kosenko EA (2010) Subcellular and metabolic examination of amyloid‐beta peptides in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis: evidence for Abeta(25‐35). Exp Neurol 221:26–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaneko I, Morimoto K, Kubo T (2001) Drastic neuronal loss in vivo by beta‐amyloid racemized at Ser(26) residue: conversion of non‐toxic [D‐Ser(26)]beta‐amyloid 1‐40 to toxic and proteinase‐resistant fragments. Neuroscience 104:1003–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klunk WE, Price JC, Mathis CA, Tsopelas ND, Lopresti BJ, Ziolko SK et al (2007) Amyloid deposition begins in the striatum of presenilin‐1 mutation carriers from two unrelated pedigrees. J Neurosci 27:6174–6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koistinaho J, Pyykonen I, Keinanen R, Hokfelt T (1996) Expression of beta‐amyloid precursor protein mRNAs following transient focal ischaemia. Neuroreport 7:2727–2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kubo T, Nishimura S, Kumagae Y, Kaneko I (2002) In vivo conversion of racemized beta‐amyloid ([D‐Ser 26]A beta 1‐40) to truncated and toxic fragments ([D‐Ser 26]A beta 25‐35/40) and fragment presence in the brains of Alzheimer's patients. J Neurosci Res 70:474–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Levin ER (1995) Endothelins. N Engl J Med 333:356–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McDonald RJ, Hong NS, Devan BD (2004) The challenges of understanding mammalian cognition and memory‐based behaviours: an interactive learning and memory systems approach. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 28:719–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McDonald RJ, White NM (1993) A triple dissociation of memory systems: hippocampus, amygdala, and dorsal striatum. Behav Neurosci 107:3–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mei X, Ezan P, Giaume C, Koulakoff A (2010) Astroglial connexin immunoreactivity is specifically altered at beta‐amyloid plaques in beta‐amyloid precursor protein/presenilin1 mice. Neuroscience 171:92–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nagy JI, Li W, Hertzberg EL, Marotta CA (1996) Elevated connexin43 immunoreactivity at sites of amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res 717:173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nicolas O, Gavin R, Braun N, Urena JM, Fontana X, Soriano E et al (2007) Bcl‐2 overexpression delays caspase‐3 activation and rescues cerebellar degeneration in prion‐deficient mice that overexpress amino‐terminally truncated prion. FASEB J 21:3107–3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Orellana JA, Shoji KF, Abudara V, Ezan P, Amigou E, Saez PJ et al (2011) Amyloid beta‐induced death in neurons involves glial and neuronal hemichannels. J Neurosci 31:4962–4977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Packard MG, Hirsh R, White NM (1989) Differential effects of fornix and caudate nucleus lesions on two radial maze tasks: evidence for multiple memory systems. J Neurosci 9:1465–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Packard MG, McGaugh JL (1996) Inactivation of hippocampus or caudate nucleus with lidocaine differentially affects expression of place and response learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem 65:65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Paxinos G, Watson C (1986) The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press, Inc.: San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pearson RC, Esiri MM, Hiorns RW, Wilcock GK, Powell TP (1985) Anatomical correlates of the distribution of the pathological changes in the neocortex in Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82:4531–4534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pluta R, Ulamek M, Januszewski S (2006) Micro‐blood‐brain barrier openings and cytotoxic fragments of amyloid precursor protein accumulation in white matter after ischemic brain injury in long‐lived rats. Acta Neurochir Suppl 96:267–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pooler AM, Arjona AA, Lee RK, Wurtman RJ (2004) Prostaglandin E2 regulates amyloid precursor protein expression via the EP2 receptor in cultured rat microglia. Neurosci Lett 362:127–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rosslenbroich V, Dai L, Franken S, Gehrke M, Junghans U, Gieselmann V, Kappler J (2003) Subcellular localization of collapsin response mediator proteins to lipid rafts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 305:392–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schmued LC, Albertson C, Slikker W Jr (1997) Fluoro‐Jade: a novel fluorochrome for the sensitive and reliable histochemical localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res 751:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shapovalova Z, Tabunshchyk K, Greer PA (2007) The Fer tyrosine kinase regulates an axon retraction response to Semaphorin 3A in dorsal root ganglion neurons. BMC Dev Biol 7:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sigurdsson EM, Lee JM, Dong XW, Hejna MJ, Lorens SA (1997) Bilateral injections of amyloid‐beta 25‐35 into the amygdala of young Fischer rats: behavioral, neurochemical, and time dependent histopathological effects. Neurobiol Aging 18:591–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Silbert LC, Quinn JF, Moore MM, Corbridge E, Ball MJ, Murdoch G et al (2003) Changes in premorbid brain volume predict Alzheimer's disease pathology. Neurology 61:487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Snowdon DA, Greiner LH, Mortimer JA, Riley KP, Greiner PA, Markesbery WR (1997) Brain infarction and the clinical expression of Alzheimer disease. The nun study. JAMA 277:813–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Streit WJ, Graeber MB, Kreutzberg GW (1988) Functional plasticity of microglia: a review. Glia 1:301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Thiel A, Radlinska BA, Paquette C, Sidel M, Soucy JP, Schirrmacher R, Minuk J (2010) The temporal dynamics of poststroke neuroinflammation: a longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging‐guided PET study with 11C‐PK11195 in acute subcortical stroke. J Nucl Med 51:1404–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, De Zubicaray GI, Janke AL, Rose SE, Semple J et al (2004) Mapping hippocampal and ventricular change in Alzheimer disease. Neuroimage 22:1754–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tsai J, Grutzendler J, Duff K, Gan WB (2004) Fibrillar amyloid deposition leads to local synaptic abnormalities and breakage of neuronal branches. Nat Neurosci 7:1181–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vanlangenakker N, Vanden BT, Krysko DV, Festjens N, Vandenabeele P (2008) Molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology of necrotic cell death. Curr Mol Med 8:207–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vermeer SE, Prins ND, den Heijer T, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM (2003) Silent brain infarcts and the risk of dementia and cognitive decline. N Engl J Med 348:1215–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Whitehead S, Cheng G, Hachinski V, Cechetto DF (2005) Interaction between a rat model of cerebral ischemia and beta‐amyloid toxicity: II. Effects of triflusal. Stroke 36:1782–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Whitehead SN, Bayona NA, Cheng G, Allen GV, Hachinski VC, Cechetto DF (2007) Effects of triflusal and aspirin in a rat model of cerebral ischemia. Stroke 38:381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Whitehead SN, Cheng G, Hachinski VC, Cechetto DF (2007) Progressive increase in infarct size, neuroinflammation, and cognitive deficits in the presence of high levels of amyloid. Stroke 38:3245–3250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Whitehead SN, Massoni E, Cheng G, Hachinski VC, Cimino M, Balduini W, Cechetto DF (2010) Triflusal reduces cerebral ischemia induced inflammation in a combined mouse model of Alzheimer's disease and stroke. Brain Res 1366:246–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zelinski EL, Hong NS, Tyndall AV, Halsall B, McDonald RJ (2010) Prefrontal cortical contributions during discriminative fear conditioning, extinction, and spontaneous recovery in rats. Exp Brain Res 203:285–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zipp F, Aktas O (2006) The brain as a target of inflammation: common pathways link inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Neurosci 29:518–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zlokovic BV (2002) Vascular disorder in Alzheimer's disease: role in pathogenesis of dementia and therapeutic targets. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 54:1553–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zussy C, Brureau A, Keller E, Marchal S, Blayo C, Delair B et al (2013) Alzheimer's disease related markers, cellular toxicity and behavioral deficits induced six weeks after oligomeric amyloid‐beta peptide injection in rats. PLoS ONE 8:e53117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]