Abstract

Autophagy is associated with the pathogenesis of Lewy body disease, including Parkinson's disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). It is known that several downstream autophagosomal proteins are incorporated into Lewy bodies (LBs). We performed immunostaining and Western blot analysis using a cellular model of PD and human brain samples to investigate the involvement of upstream autophagosomal proteins (ULK1, ULK2, Beclin1, VPS34 and AMBRA1), which initiate autophagy and form autophagosomes. Time course analysis of cultured cells transfected with flag‐α‐synuclein and synphilin‐1 revealed upregulation of these upstream proteins with accumulation of LB‐like inclusions. In human specimens, only mature LBs were positive for upstream autophagosomal proteins. Western blotting of fractionated brain lysates showed that upstream autophagosomal proteins were detected in the soluble and insoluble fraction in DLB, corresponding to the bands of phosphorylated α‐synuclein. However, Western blot analysis of total brain lysates in PD and DLB showed that the increase of upstream autophagosomal proteins was only partial. The quantitative, qualitative and locational alteration of upstream autophagosomal proteins in the present study indicates their involvement in the pathogenesis of LB disease. Our data also suggest that misinduction or impairment of upstream autophagy might occur in the disease process of LB disease.

Keywords: autophagy, dementia with Lewy bodies, Lewy body, Lewy body disease, Parkinson's disease

Introduction

Macroautophagy (herein referred to as autophagy) is a highly conserved degradation pathway whereby not only cytosolic components but also aberrant proteins are sequestered within double‐membraned vesicles, known as autophagosomes. The engulfed proteins are then dissolved after fusion with lysosomes. This degradation process is tightly regulated by phosphorylation, dephosphorylation, acetylation or ubiquitination of various molecular complexes involved in autophagy. The upstream part of the autophagy chain primarily involves the formation of autophagosomes. UNC‐51‐like kinase 1 (ULK1) is a crucial initiator of autophagy, and regulated by various routes that include the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), AMP‐activated protein kinase (AMPK) and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) 23, 36, 45. Under normal conditions, mTOR phosphorylates and negatively regulates a complex consisting of ULK1, ULK2, autophagy‐related gene 13 (ATG13), ATG101 and FIP200 3, 11, 12, 14, 15, 26, 32. Upon inhibition of mTOR, ULK1 is activated and triggers the phosphorylation of ATG13 and FIP200, thus initiating autophagy 19. In addition to mTOR, the major energy sensor AMPK also activates ULK1 through its phosphorylation 23. Growth factor deprivation causes activation of GSK3, resulting in phosphorylation of acetyltransferase TIP60 and upregulation of ULK1 28. Upon induction of autophagy, the ULK1 complex is recruited to isolate membrane where ULK1 phosphorylates Beclin1, one of the core components of class III phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase [PI(3)KC3] 7. The PI(3)KC3 complex comprises at least six components: VPS34, p150, Beclin1, ATG14L, UVRAG and Rubicon 18, 27, 30, 47, 48, 61. Phosphorylation of Beclin1 at Ser 15 (Ser 14 in mice) is essential for its activation, followed by autophagy‐specific activation of VPS34 42. Furthermore, autophagy/Beclin‐1 regulator 1 (AMBRA1) induces autophagosome nucleation by promoting the interaction of Beclin1 and VPS34. AMBRA1 also mediates Lys 63‐ubiquitination of ULK1, contributing to ULK1 stabilization and its self‐association during autophagy 7, 34. In addition, AMBRA1 is involved in autophagic removal of damaged mitochondria through interaction with Parkin 53. These findings suggest that delicate control of autophagy initiation and autophagosome formation is based on intricate and elegant cross‐talk among upstream autophagosomal kinases.

Accumulation of misfolded proteins in proteinaceous inclusions is considered to be a common feature of many neurodegenerative diseases, and clearance of abnormal proteins by the ubiquitin–proteasome system and/or autophagy–lysosome system is paramount for cellular survival. Abnormal autophagy is involved in various neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer's disease (AD) 4, 35, Parkinson's disease (PD) 50 and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) 44. In PD and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), phosphorylated α‐synuclein (p‐α‐Syn) is accumulated and fibrillated in the neuronal cytoplasm and processes as Lewy bodies (LBs) and Lewy neurites, respectively 10, 43. A growing body of evidence suggests that oligomers and protofibrils of α‐Syn are neurotoxic 8, 24, 25. Recently, it has been demonstrated that proteins involved in the downstream part of the autophagy process, including microtubule‐associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3), neighbor of BRCA gene 1 (NBR1) and γ‐aminobutyric acid type A receptor protein, are incorporated into LBs 37, 50. The phosphatidyl ethanolamine‐conjugated form of LC3 (LC3‐II) is tightly bound to the inner surface of autophagosomes and serves as an anchor for autophagy substrates using cargo receptors (p62 and NBR1) 20, 21. These findings indicate that the autophagy–lysosome system is implicated in the pathogenesis of LB disease (PD and DLB). Moreover, histone deacetylase 6 plays a role in aggresome formation and acts as a linker between polyubiquitinated proteins and the molecular motor dynein 22, 33. Despite previous detailed analyses of the downstream autophagosomal proteins, only a few fragmentary studies have investigated the involvement of upstream autophagosomal proteins in the formation of LBs 17, 57, 58. Little is known about (i) whether upstream autophagy proteins are involved in the disease process of LB disease and (ii), if so, when and how these proteins are induced.

In the present study, we performed immunostaining and Western blot analysis using a cellular model of PD and human brain samples to better understand the pathogenesis of LB disease. Our results revealed that the upstream autophagy proteins (ULK1, ULK2, VPS34 and AMBRA1) were consistently present in LBs and were upregulated during the formation of LB‐like inclusions. However, in the brains of LB disease, the increase of upstream autophagosomal proteins was only partial.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against ULK1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), ULK2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), VPS34 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), Beclin1 (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA), phosphorylated Beclin1 (hereafter referred to as p‐Beclin1) (Abbiotec, San Diego, CA, USA), AMBRA1 (ProSci‐incorporated, Poway, CA, USA), AMBRA1 (Novus Biologicals), AMBRA1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), LC3 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and β‐actin (Sigma), rabbit monoclonal antibodies against GFP (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and p‐α‐Syn (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), and mouse monoclonal antibody against FLAG (Sigma) were used as primary antibodies. Anti‐p‐Beclin1 antibody recognizes translated Beclin1 only when phosphorylated at Ser 15 (Ser 14 in mice) 42.

Cell culture

HEK293 cells were purchased from the Japanese Collection of the Research Bioresources Cell Bank (Osaka, Japan), and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics. For the formation of LB‐like inclusions, 1 μg of a plasmid designed for simultaneous expression of flag‐α‐synuclein and synphilin‐1 tagged with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) 52 was transfected into HEK293 cells using X‐tremegene 9® (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). These inclusions are known to contain components of LBs, including ubiquitin, p62, NUB1, NEDD8, LC3 and the proteasome, suggesting that the inclusions generated in our assay are similar to the LBs in brains of patients and the pathological significance of the inclusions in this model is already established 37, 52. EGFP–vector control was also utilized to confirm no occurrence of inclusions or autophagy induction after this transfection.

Specificity of the primary antibodies

Specificity of the primary antibodies was examined by Western blot analysis and immunohistochemistry. Lysates were prepared from frozen cerebral cortex tissue of neurologically normal control subjects and whole brain of adult mice and rats. HEK293 cells transfected with a plasmid designed for AMBRA1 with C terminal FLAG were also examined by Western blot analysis using anti‐FLAG and anti‐AMBRA1 antibodies. Isotype and dilution matched control antisera (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) were further utilized to differentiate non‐specific background signal from specific antibody signal.

Semi‐quantitative analysis, Western blot analysis and immunocytochemistry of cultured cells

At 0, 12, 24 and 48 h after transfection, semi‐quantitative analysis was performed to count the LB‐like inclusions based on 10 randomly chosen low‐power fields. The cultured cells were also harvested to assess the expression levels of proteins in the total lysates. The cells were lysed with sample buffer (75 mM Tris‐HCl, pH 6.8, 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 25% glycerol, 5% β‐mercaptoethanol), and Western blot analysis was performed as reported previously 60. Anti‐ULK1 (1:1000), anti‐ULK2 (1:1000), anti‐Beclin1 (1:1000), anti‐p‐Beclin1 (1:1000), anti‐VPS34 (1:1000), anti‐AMBRA1 (1:1000), anti‐GFP (1:4000), anti‐β‐actin (1:10 000) and anti‐LC3 (1:4000) antibodies were used as the primary antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated anti‐rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as the secondary antibody.

For immunostaining, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X‐100 for 10 minutes, followed by incubation with anti‐ULK1 (1:100), anti‐ULK2 (1:100), anti‐Beclin1 (1:100), anti‐p‐Beclin1 (1:100), anti‐VPS34 (1:100) and anti‐AMBRA1 (1:100) antibodies. Alexa Fluor 594‐conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA; 1:750) was utilized as a secondary antibody. After a rinse in phosphate‐buffered saline, the cells were mounted and examined with a confocal microscope (EZ‐Ci; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Human subjects and immunohistochemistry

Tissue samples were obtained from the Department of Neuropathology, Institute of Brain Science, Hirosaki University Graduate School of Medicine, Hirosaki, and the Department of Pathology, Brain Research Institute, University of Niigata, Niigata, Japan. Thirty‐one autopsy cases were investigated in this study; these included cases of sporadic PD (Braak PD stage 4; n = 7) 2, neocortical‐type DLB (n = 5) 31, AD (n = 8), ALS (n = 5) and normal controls (aged 53–84 years, average 66.5 years, n = 6). For routine histological investigations, the brain and spinal cord were fixed with 10% buffered formalin for 3–4 weeks. In all cases except for AD, the concomitant AD‐related neurofibrillary changes were less than Braak stage IV 1. All cases of AD lacked α‐synuclein pathology.

Four‐micrometer thick sections were cut from the temporal cortex, hippocampus, midbrain, upper pons and spinal cord of patients with PD, DLB, AD and ALS and control subjects, and immunostained using the avidin‐biotin‐peroxidase complex method with diaminobenzidine as the chromogen. The primary antibodies used were anti‐ULK1 (1:100), anti‐ULK2 (1:500), anti‐Beclin1 (1:200), anti‐VPS34 (1:200) and two anti‐AMBRA1 antibodies (1:500). The sections were pretreated in an autoclave for 10 minutes in 10 mmol citrate buffer (pH 6.0).

Paraffin sections from the midbrain of PD patients were processed for double‐label immunofluorescence. Deparaffinized sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with a mixture of monoclonal anti‐p‐α‐Syn (#64; Wako, Osaka, Japan; 1:1000) and polyclonal anti‐ULK1 (1:50), anti‐ULK2 (1:100), anti‐VPS34 (1:100) or anti‐AMBRA1 (1:50). The sections were then rinsed and incubated with anti‐rabbit IgG tagged with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen; 1:1000) or anti‐mouse IgG tagged with Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen; 1:1000) for 2 h at 4°C. Then the sections were mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) and examined as described earlier.

Fractionation and Western blot analysis of brain lysates

For biochemical analysis, brain tissues were dissected out at autopsy and frozen rapidly at −70°C. For the present study, frozen tissues from the substantia nigra of patients with PD (aged 65–79 years, average 71.3 years, n = 3) and age‐matched normal controls (aged 64–82 years, average 75 years, n = 3) and the middle temporal cortex of patients with DLB (aged 66–91 years, average 77.8 years, n = 7) and age‐matched normal controls (aged 62–82 years, average 73.5 years, n = 7) were employed. Western blot analysis was performed as described earlier. Anti‐ULK1 (1:1000), anti‐ULK2 (1:1000), anti‐Beclin1 (1:1000), anti‐p‐Beclin1 (1:1000), anti‐VPS34 (1:1000) and anti‐β‐actin (1:10 000) antibodies were used as the primary antibodies.

For fractionation of brain extracts, frozen tissues from DLB patients (n = 4) and control cases (n = 4) were weighed and sequentially extracted with buffers of increasing strength using a protocol described previously 49. Briefly, samples were homogenized with 10 volumes of buffer A (10 mM Tris‐HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EGTA, 10% sucrose, 0.8 M NaCl) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and centrifuged (fraction 1). Afterwards, another equal volume of buffer A containing 2% Triton X‐100 was added. Incubation was continued for 30 minutes at 37°C, and then centrifugation was performed at 100 000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C (fraction 2). The resulting pellet was homogenized in five volumes of buffer A with 1% sarkosyl and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. The homogenate was then spun at 100 000 × g for 30 minutes at room temperature (fraction 3). The sarkosyl‐insoluble pellet was homogenized in four volumes of buffer A containing 1% 3‐[(3‐cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio] propanesulfonate and spun at 100 000 × g for 20 minutes at room temperature (fraction 4). The pellet was then sonicated in 1.5 volumes of 8 M urea buffer (fraction 5). For Western blot analysis, anti‐p‐α‐Syn antibody (1:2000) was used as the primary antibody in addition to anti‐ULK1 (1:1000), anti‐ULK2 (1:1000), anti‐Beclin1 (1:1000), anti‐p‐Beclin1 (1:1000), anti‐VPS34 (1:1000) and anti‐β‐actin antibodies (1:10 000).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using two‐sample t‐test and one‐way analysis of variance. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Hirosaki University Graduate School of Medicine.

Results

Specificity of the primary antibodies

Anti‐ULK1, anti‐ULK2 and anti‐VPS34 antibodies recognized bands of similar molecular size (about 100 kDa) in human, mouse and rat brain. Anti‐Beclin1 and anti‐p‐Beclin1 antibodies detected bands of about 52 kDa. These recognized bands were compatible with the molecular mass of ULK1, ULK2, Beclin1, p‐Beclin1 and VPS34 (Figure S1A–E). On the other hand, anti‐AMBRA1 antibody (ProSci‐incorporated) detected a very weak band of about 150 kDa upon immunoblotting (Figure S1F). Immunohistochemistry using these antibodies (ProSci‐incorporated, Novus Biologicals, and Cell Signaling Technology) revealed positive immunolabeling of LBs in PD (Figure S1G). Furthermore, both anti‐FLAG and anti‐AMBRA1 antibodies detected a band of 150 kDa only in HEK293 cells transfected with FLAG‐AMBRA1 (Figure S1H). Immunohistochemistry using isotype and dilution matched control antisera did not stain any LBs (data not shown).

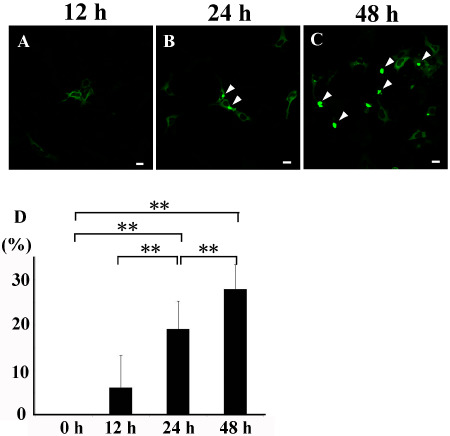

Upstream autophagy‐related proteins are increased in parallel with accumulation of LB‐like inclusions

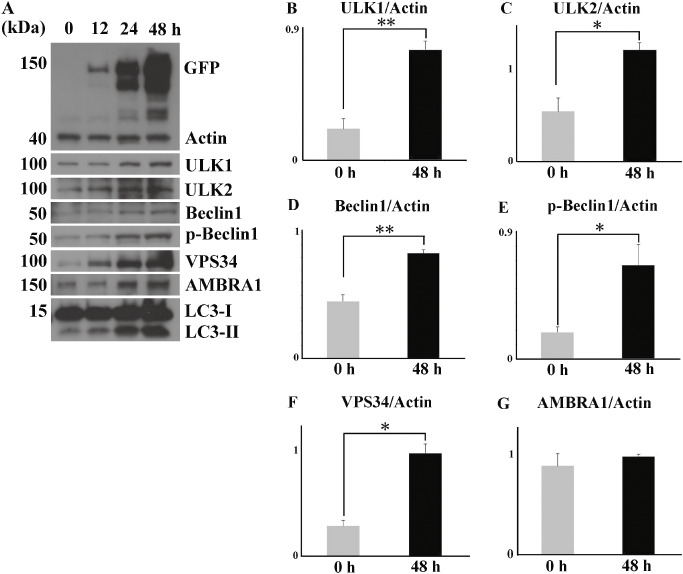

No inclusions were found in HEK293 cells transfected with EGFP vector control (data not shown). Transfection of flag‐α‐Syn and synphilin‐1 tagged with EGFP significantly increased the number of LB‐like inclusions over time (Figure 1). Transfection reagent treatment and transfection of EGFP–vector control did not induce autophagy (Figure S2). Time course analysis showed that the expression levels of upstream autophagosomal proteins rose in parallel with accumulation of the inclusions (Figure 2A). Activation of autophagy was confirmed by upregulation of LC3‐II relative to the level of LC3‐I (Figure 2A). Two‐point analysis at 0 and 48 h after transfection demonstrated a significant increase in the levels of ULK1, ULK2, Beclin1, p‐Beclin1 and VPS34 (Figure 2B–F). There was no significant increase of AMBRA1 due to variation in the results of three independent analyses (Figure 2G).

Figure 1.

Time course analysis of L ewy body ( LB )‐like inclusions. Green signal indicates enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). Increased numbers of LB‐like inclusions (arrowheads) in the cytoplasm of HEK293 cells at 12 (A), 24 (B) and 48 h (C) after transfection with flag‐α‐synuclein and synphilin‐1 tagged with EGFP. (D) Significantly increased number of LB‐like inclusions over time. Bars = 20 μm, **P < 0.01.

Figure 2.

Time course analysis of upstream autophagosomal proteins. (A) Chronological upregulation of the proteins (ULK1, ULK2, VPS34, AMBRA1, p‐Beclin1 and Beclin1) parallels the accumulation of Lewy body (LB)‐like inclusions. LC3‐II is also upregulated relative to LC3‐I. Significant increase in the expression levels of ULK1 (B), ULK2 (C), Beclin1 (D), p‐Beclin1 (E) and VPS34 (F), but not AMBRA1 (G), 48 h after transfection. Values are expressed as means + standard deviation of three experiments. *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

Previous studies using cultured cells have shown that Beclin1 co‐localizes with synphilin‐1‐positive aggresomes, and that VPS34 partially surrounds them 57. We also examined the cultured cells using antibodies against ULK1, ULK2, VPS34, Beclin1, p‐Beclin1 and AMBRA1. However, all antibodies did not immunolabel LB‐like inclusions at 48 h (data not shown).

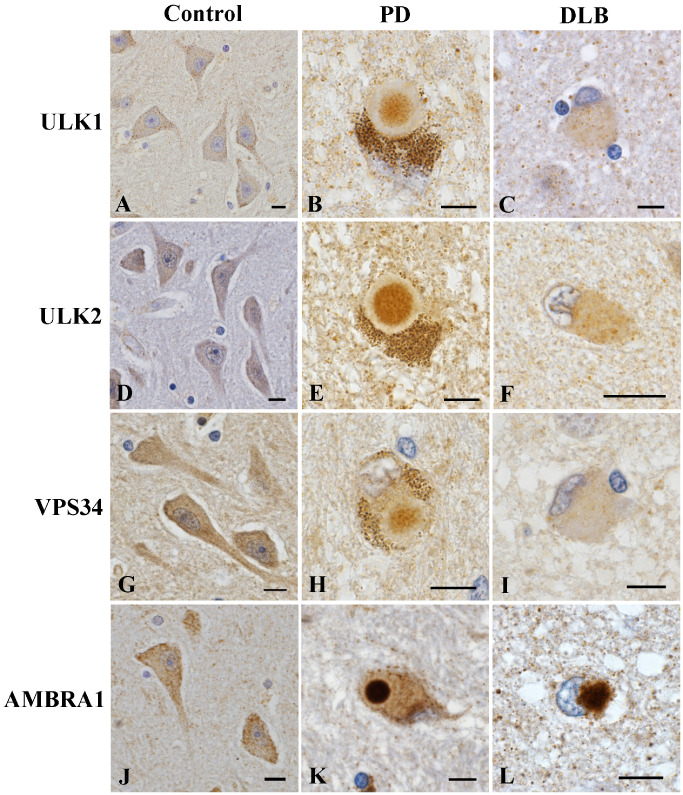

Upstream autophagosomal proteins are incorporated into LBS

To further confirm whether upstream autophagosomal proteins were associated with LB formation in human subjects, brain specimens from patients with PD and DLB, and normal controls, were examined immunohistochemically. In normal controls, the neuronal cytoplasm was weakly positive for ULK1 (Figure 3A), ULK2 (Figure 3D), VPS34 (Figure 3G) and AMBRA1 (Figure 3J) throughout the brain and spinal cord. In PD and DLB, the cores of LBs in the substantia nigra and locus ceruleus were moderately immunopositive for ULK1 (Figure 3B), ULK2 (Figure 3E) and VPS34 (Figure 3H). Intraneuritic LBs (Lewy neurites) were not immunolabeled. Cortical LBs were slightly positive for ULK1 (Figure 3C), ULK2 (Figure 3F) and VPS34 (Figure 3I). Anti‐AMBRA1 antibodies intensely immunolabeled both brainstem‐type and cortical LBs (Figure 3K,L). Lewy neurites were also positive for AMBRA1. No LBs were stained with anti‐Beclin1 antibody. None of the primary antibodies against upstream autophagosomal proteins immunolabeled diffuse cytoplasmic staining or pale bodies, which are considered to represent the early stage of LBs 54 (data not shown). No immunoreactivity was seen in senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in AD, or skein‐like inclusions in ALS (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Immunoreactivity of upstream autophagosomal proteins in human subjects. The neurons in the hippocampus of normal control subjects (A, D, G, J). Brainstem‐type Lewy bodies (LBs) in the substantia nigra in patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) (B, E, H, K) and cortical LBs in the temporal cortex of patients with dementia with LBs (DLB) (C, F, I, L). Weak immunoreactivity for ULK1 (A), ULK2 (D), VPS34 (G) and AMBRA1 (J) in the neuronal cytoplasm. The core of brainstem‐type LBs is moderately immunopositive for ULK1 (B), ULK2 (E) and VPS34 (H). Cortical LBs are slightly positive for ULK1 (C), ULK2 (F) and VPS34 (I). Intense immunoreactivity for AMBRA1 in the core of brainstem‐type LBs (K) and cortical LBs (L). Bars = 10 μm.

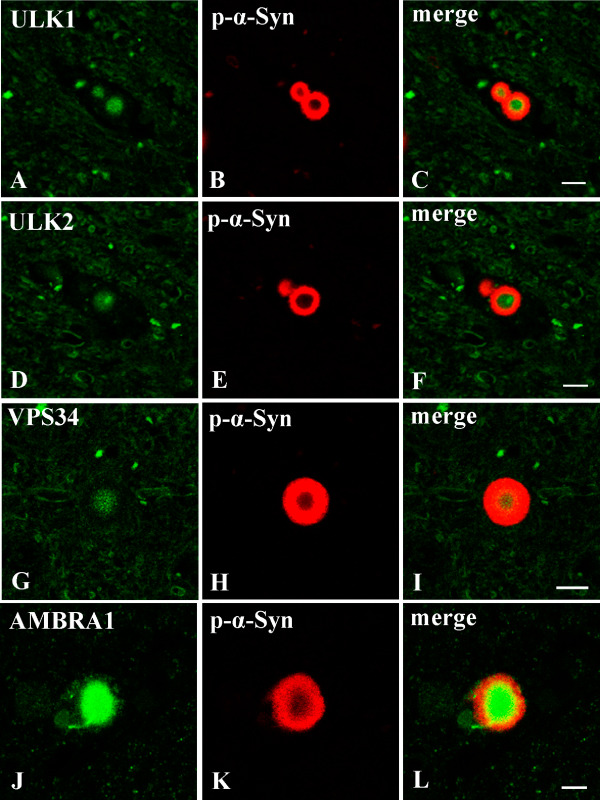

Double immunofluorescence analysis revealed that immunoreactivity for ULK1, ULK2, VPS34 and AMBRA1 was consistently concentrated in the central portion of LBs, whereas p‐α‐Syn immunoreactivity was more intense in the peripheral portion (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Double immunofluorescence staining of the substantia nigra in Parkinson's disease ( PD ). ULK1, ULK2, VPS34 and AMBRA1 appear green; phosphorylated α‐synuclein (p‐α‐Syn) appears red; and overlap of ULK1, ULK2, VPS34 or AMBRA1 and p‐α‐Syn appears yellow (merged). Immunoreactivity for ULK1, ULK2, VPS34 and AMBRA1 is more apparent in the core of Lewy bodies, whereas the peripheral portions show intense staining with anti‐p‐α‐Syn. Bars = 10 μm.

In advanced stage of PD and DLB, upstream autophagosomal proteins are localized with soluble and insoluble fraction, but their increase is only partial

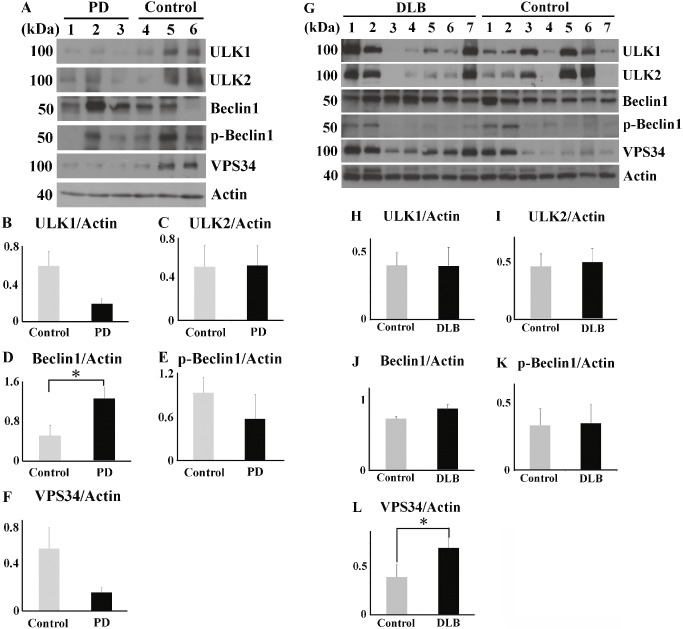

Immunoblotting was performed using total lysates of the substantia nigra of normal controls (n = 3) and PD patients (n = 3), and the middle temporal cortex of normal controls (n = 7) and DLB patients (n = 7). The raw data of PD or DLB patients are shown in Figure 5A or G, respectively. In the brains of patients with PD, there was no significant increase of ULK1 and ULK2 (Figure 5B,C). Only Beclin1 expression significantly increased in PD (Figure 5D). The levels of p‐Beclin1 and VPS34 also did not reach statistical significance between PD patients and normal controls (Figure 5E,F). In the brains of patients with DLB, the levels of ULK1, ULK2, Beclin1 and p‐Beclin1 varied among individuals. There was no significant difference in the levels of ULK1, ULK2, Beclin1 and p‐Beclin1 between DLB patients and controls (Figure 5H–K). By contrast, VPS34 expression was significantly higher in the brains of DLB patients than in controls (Figure 5L). In human brain lysates, three different anti‐AMBRA1 antibodies did not detect a band around its molecular weight of 150 kDa.

Figure 5.

Western blot analysis of total brain lysates from Parkinson's disease ( PD ) patients, dementia with Lewy's body ( DLB ) patients and controls. Raw data for levels of ULK1, ULK2, Beclin1, p‐Beclin1 and VPS34 in the substantia nigra of patients with PD (n = 3) and normal controls (n = 3) (A) and the temporal cortex of patients with DLB (n = 7) and normal controls (n = 7) (G). There are no significant differences in ULK1 and ULK2 levels between PD patients and controls (B, C). The Beclin1 expression significantly increased in PD patients than in the controls (D). P‐Beclin1 and VPS34 levels are unchanged between PD patients and controls (E, F). There are no significant differences in ULK1, ULK2, Beclin1 and p‐Beclin1 levels between DLB patients and controls (H–K). (L) The VPS34 level is significantly higher in the DLB patients than in the controls. *P < 0.05.

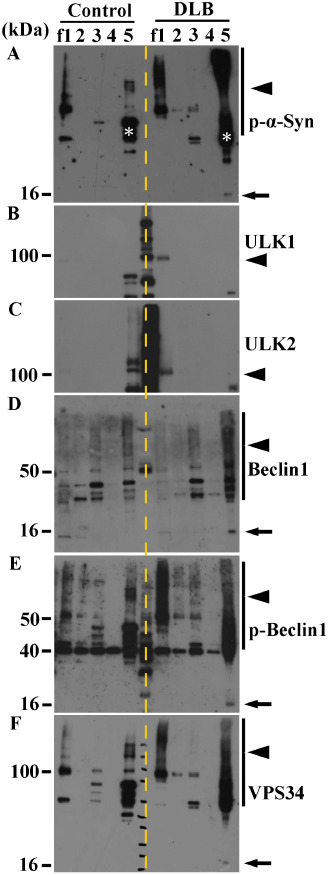

We further fractionated the brain lysates from DLB patients (n = 4) and normal controls (n = 4). The upstream autophagosomal proteins (ULK1, ULK2, VPS34, Beclin1 and p‐Beclin1) were localized with soluble or insoluble fractions of the DLB patients. One representative case of the four cases is shown in Figure 6. p‐α‐Syn with a molecular mass of 16 kDa was detected in the insoluble fraction (fraction 5) from the DLB patient (Figure 6A). We also confirmed the appearance of p‐α‐Syn smears in the soluble and insoluble fractions (fractions 1 and 5) from the DLB patient (Figure 6A). Bands of ULK1 and ULK2 were found to be much stronger in the soluble fraction (fraction 1) from the DLB patient, relative to that of the control (Figure 6B,C). Bands of Beclin1, p‐Beclin1 and VPS34 were observed at 16 kDa in the insoluble fraction (fraction 5) from the DLB patient (Figure 6D–F). Moreover, these proteins were also detected in the soluble and insoluble fractions (fractions 1 and 5) from the DLB patient, corresponding to the smear bands of p‐α‐Syn (Figure 6A,D–F).

Figure 6.

Western blot analysis of fractionated brain lysates from dementia with Lewy's body ( DLB ) and control. (A) In the insoluble fraction (fraction f5) from a representative patient with DLB, a band of p‐α‐Syn expression corresponding to a molecular mass of 16 kDa is evident (arrow). High‐molecular mass p‐α‐Syn is evident in the soluble (f1) and insoluble (f5) fractions from the DLB patient (arrowhead). White asterisks indicate non‐specific bands. (B, C) A ULK1‐ or ULK2‐positive band is evident in the soluble fraction (f1) in DLB (arrowheads), but not in the control. (D–F) High‐molecular mass Beclin1 (D), p‐Beclin1 (E) and VPS34 (F) are seen in the insoluble fraction (f5) in DLB (arrows). High‐molecular mass ladders of p‐Beclin1 (E) and VPS34 (F) are also evident in the soluble fraction (f1) in DLB (arrowheads).

Discussion

In the present study, Western blot analysis of a cellular model of PD demonstrated that the levels of upstream autophagosomal proteins (ULK1, ULK2, VPS34 and Beclin1) were increased chronologically along with the accumulation of LB‐like inclusions. Phosphorylation of Ser 15 on Beclin1 implies activation of autophagy through interaction of the PI(3)KC3 and ULK1 complexes. Of note, immunoblotting of fractionated brain lysates from the representative DLB patient showed that the PI(3)KC3 complex, composed of Beclin1, p‐Beclin1 and VPS34, was localized with soluble and insoluble smear bands of p‐α‐Syn. The ULK1 complex was also found only in the soluble fraction from DLB patients. These qualitative and locational alterations of these proteins clearly mean their involvement in the disease process of LB disease. On the other hand, in the present study of the cultured cells, anti‐ULK1, anti‐ULK2, anti‐Beclin1, anti‐VPS34 and anti‐AMBRA1 antibodies did not stain LB‐like inclusions. Thus, these upstream autophagosomal proteins might not be interacting proteins of p‐α‐Syn and the autophagy–lysosome system may represent an adaptive response leading to LB degradation.

The present study revealed that the molecules involved in the upstream part of the autophagy process (ULK1, ULK2, VPS34 and AMBRA1) were consistently accumulated in LBs in human patients. However, no immunoreactivity for ULK1, ULK2, VPS34 or AMBRA1 was found in pale bodies or areas of diffuse cytoplasmic staining, which are the precursors of LBs 54. In a cellular model of PD, induction of autophagy occurred with accumulation of LB‐like inclusions, whereas in the brains of LB disease, upstream autophagosomal proteins might be induced from the later stage of LB formation. In addition, Western blot analysis in the brains of advanced PD and DLB patients showed that upstream autophagosomal proteins were insufficiently increased. To date, malfunction of downstream autophagosomal proteins, including LC3‐II, has been reported in LB disease and multiple system atrophy 37, 50, 51. The present study further demonstrated that upstream autophagosomal proteins, which play a key role in autophagosome formation, are also involved in LB disease. It is worth noting that no autophagosomes or their membrane components have so far been detected in LBs by electron microscopy. Accordingly, our results raise a question of how later stage induction of autophagy can lead to effective degradation of such large LBs. In a mouse model of PD, secondary dysregulation of autophagy has been shown to occur, contributing to the death of dopaminergic neurons 6. In other neurodegenerative diseases, including AD and frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP‐43 inclusions, impairment of autophagy is also known 29, 38, 41. Taken together, it is likely that in advanced stage of PD and DLB, both upstream and downstream parts of the autophagic process might be less effectively working to degrade p‐α‐Syn or misinduction of autophagy might occur. Autophagy impairment might be a common pathological condition in advanced stage of neurodegenerative diseases.

LBs comprise more than 90 molecular components 55. Several molecules are observed only in brainstem‐type LBs, two of them [cytochrome c and extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK)] being prominently localized in the central portion of brainstem‐type LBs 9, 13. Dysfunction of cytochrome c, a component of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, generates oxidative stress 46. ERK is one of the mitogen‐activated protein kinases and related to tau phosphorylation 39. In addition, independent of the Beclin1/VPS34 pathway, ERK also acts downstream of mitophagy as a result of 1‐methyl‐4‐phenylpyridinium‐induced depletion of mitochondrial membrane potential and increased lipid oxidation 5. The present study demonstrated consistent positivity of the upstream autophagosomal proteins in the central portion of brainstem‐type LBs. It would be of great interest to examine possible cross‐links between these molecules from the perspective of mitophagy and LB core immunoreactivity.

Intense AMBRA1 reactivity was seen in both brainstem‐type and cortical LBs. In addition to the role of AMBRA1 as an autophagy facilitator, it binds to Parkin on damaged mitochondria and activates autophagosome formation in association with the PI(3)KC3 complex 53. Indeed, accumulation of p‐α‐Syn can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction 16. This Parkin–AMBRA1‐mediated mechanism for the removal of damaged mitochondria may be involved in the disease process of PD and DLB.

It has been widely debated whether activation of autophagy could be a therapeutic option for patients with neurodegenerative disorders. In PD, autophagy is impaired, leading to reduced degradation of aberrant protein. Accumulation of p‐α‐Syn causes mitochondrial dysfunction, thus compromising the intracellular environment 6, 16. This vicious circle may be another important aspect of PD pathogenesis. In fact, in a cellular model of PD, modulation of autophagy has been shown to reduce synphilin‐1 aggregates along with Beclin1 activation 57. The present study has clearly demonstrated the involvement of autophagy‐related proteins in the disease process of LB disease. Our findings reinforce the hypothesis that proper modulation of autophagy might reduce the aberrant protein burden in cells. In this context, however, we need to consider the degree to which autophagy should be activated. In mouse models of cancer, heterozygous disruption of Beclin1 has been shown to promote tumorigenesis 40, 59. Conversely, autophagy shows greatest activation in ischemic regions of tumors, associated with tumor growth 56, suggesting that hyperactivation of autophagy might lead to coincidental complications, such as promotion of spontaneous tumors. Thus, restoring the functional level of autophagy in PD back to the basal level may be optimal for cellular survival.

In conclusion, the present study has demonstrated quantitative, qualitative and locational alteration of upstream autophagosomal proteins in LB disease. In advanced stage of PD and DLB, LB‐bearing neurons might be terminally ill and unable to degrade abnormal proteins. Our results support the contention that autophagy‐modulating therapy might be feasible for patients with PD and DLB. Maintenance of autophagy from the early stage of PD and DLB might be essential for neuroprotection.

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

Supporting information

Figure S1. (A–E) Specificity of the primary antibodies. Anti‐ULK1, anti‐ULK2 and anti‐VPS34 antibodies recognizing bands of similar molecular size (about 100 kDa) in human, mouse and rat brain (arrows). Anti‐Beclin1 and anti‐p‐Beclin1 antibodies detecting bands of about 52 kDa (arrows). (F) Anti‐AMBRA1 antibody detecting a very weak band of its molecular weight 150 kDa (arrow). (G) Anti‐AMBRA1 antibody (Novus Biologicals) revealing positive immunolabeling of LBs in PD. Two other anti‐AMBRA1 antibodies (ProSci‐incorporated and Cell Signaling Technology) showing similar immunostaining of LBs. (H) Anti‐AMBRA1 antibody detecting a band of 150 kDa, corresponding to a band of FLAG‐AMBRA1. Bar = 10 μm.

Figure S2. No induction of autophagy after treatments of transfection reagent or EGFP–vector control in the results of three independent analyses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant numbers 26860655 (YM), 26430050 (KT), 26430049 (FM) and 24300131 (KW); a grant for Hirosaki University Institutional Research (KW), the Collaborative Research Project (2015‐2508) of the Brain Research Institute, Niigata University (FM), the Research Committee for Ataxic Disease (HS, KW) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan, Japan Foundation for Neuroscience and Mental Health (KW), the GSK Japan Research Grant (YM) and Hirosaki University Grant for Exploratory Research by Young Scientists and Newly‐appointed Scientists (YM). The authors wish to express their gratitude to A. Ono and M. Nakata for technical assistance.

References

- 1. Braak H, Braak E (1991) Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer‐related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82:239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, de Vos RA (2003) Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging 24:197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chan EY, Longatti A, McKnight NC, Tooze SA (2009) Kinase‐inactivated ULK proteins inhibit autophagy via their conserved C‐terminal domains using an Atg13‐independent mechanism. Mol Cell Biol 29:157–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Choi AM, Ryter SW, Levine B (2013) Autophagy in human health and disease. N Engl J Med 368:651–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chu CT, Zhu J, Dagda R (2007) Beclin 1‐independent pathway of damage‐induced mitophagy and autophagic stress: implications for neurodegeneration and cell death. Autophagy 3:663–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dehay B, Bové J, Rodríguez‐Muela N, Perier C, Recasens A, Boya P et al (2010) Pathogenic lysosomal depletion in Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci 30:12535–12544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Di Bartolomeo S, Corazzari M, Nazio F, Oliverio S, Lisi G, Antonioli M et al (2010) The dynamic interaction of AMBRA1 with the dynein motor complex regulates mammalian autophagy. J Cell Biol 191:155–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ding TT, Lee SJ, Rochet JC, Lansbury PT Jr (2002) Annular alpha‐synuclein protofibrils are produced when spherical protofibrils are incubated in solution or bound to brain‐derived membranes. Biochemistry 41:10209–10217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferrer I, Blanco R, Carmona M, Puig B, Barrachina M, Gómez C et al (2001) Active, phosphorylation‐dependent mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK/ERK), stress‐activated protein kinase/c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK), and p38 kinase expression in Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neural Transm 108:1383–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fujiwara H, Hasegawa M, Dohmae N, Kawashima A, Masliah E, Goldberg MS et al (2002) α‐Synuclein is phosphorylated in synucleinopathy lesions. Nat Cell Biol 4:160–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ganley IG, Lam DH, Wang J, Ding X, Chen S, Jiang X (2009) ULK1.ATG13.FIP200 complex mediates mTOR signaling and is essential for autophagy. J Biol Chem 284:12297–12305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hara T, Takamura A, Kishi C, Iemura S, Natsume T, Guan JL et al (2008) FIP200, a ULK‐interacting protein, is required for autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol 181:497–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hashimoto M, Takeda A, Hsu LJ, Takenouchi T, Masliah E (1999) Role of cytochrome C as a stimulator of alpha‐synuclein aggregation in Lewy body disease. J Biol Chem 274:28849–28852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hosokawa N, Hara T, Kaizuka T, Kishi C, Takamura A, Miura Y et al (2009) Nutrient‐dependent mTORC1 association with the ULK1‐Atg13‐FIP200 complex required for autophagy. Mol Biol Cell 20:1981–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hosokawa N, Sasaki T, Iemura S, Natsume T, Hara T, Mizushima N (2009) Atg101, a novel mammalian autophagy protein interacting with Atg13. Autophagy 5:973–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hsu LJ, Sagara Y, Arroyo A, Rockenstein E, Sisk A, Mallory M et al (2000) Alpha‐synuclein promotes mitochondrial deficit and oxidative stress. Am J Pathol 157:401–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang Y, Chegini F, Chua G, Murphy K, Gai W, Halliday GM (2012) Macroautophagy in sporadic and the genetic form of Parkinson's disease with the A53T α‐synuclein mutation. Transl Neurodegener 1:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Itakura E, Kishi C, Inoue K, Mizushima N (2008) Beclin 1 forms two distinct phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase complexes with mammalian Atg14 and UVRAG. Mol Biol Cell 19:5360–5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jung CH, Jun CB, Ro SH, Kim YM, Otto NM, Cao J et al (2009) ULK‐Atg13‐FIP200 complexes mediate mTOR signaling to the autophagy machinery. Mol Biol Cell 20:1992–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T et al (2000) LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J 19:5720–5728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Oshitani‐Okamoto S, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T (2004) LC3, GABARAP and GATE16 localize to autophagosomal membrane depending on form‐II formation. J Cell Sci 117:2805–2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kawaguchi Y, Kovacs JJ, McLaurin A, Vance JM, Ito A, Yao TP (2003) The deacetylase HDAC6 regulates aggresome formation and cell viability in response to misfolded protein stress. Cell 115:727–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL (2011) AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol 13:132–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lashuel HA, Hartley D, Petre BM, Walz T, Lansbury PT Jr (2002) Neurodegenerative disease: amyloid pores from pathogenic mutations. Nature 418:291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lashuel HA, Petre BM, Wall J, Simon M, Nowak RJ, Walz T et al (2002) Alpha‐synuclein, especially the Parkinson's disease‐associated mutants, forms pore‐like annular and tubular protofibrils. J Mol Biol 322:1089–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee EJ, Tournier C (2011) The requirement of uncoordinated 51‐like kinase 1 (ULK1) and ULK2 in the regulation of autophagy. Autophagy 7:689–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liang C, Feng P, Ku B, Dotan I, Canaani D, Oh BH et al (2006) Autophagic and tumour suppressor activity of a novel Beclin1‐binding protein UVRAG. Nat Cell Biol 8:688–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lin SY, Li TY, Liu Q, Zhang C, Li X, Chen Y et al (2012) GSK3‐TIP60‐ULK1 signaling pathway links growth factor deprivation to autophagy. Science 336:477–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ma JF, Huang Y, Chen SD, Halliday G (2010) Immunohistochemical evidence for macroautophagy in neurones and endothelial cells in Alzheimer's disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 36:312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Matsunaga K, Saitoh T, Tabata K, Omori H, Satoh T, Kurotori N et al (2009) Two Beclin 1‐binding proteins, Atg14L and Rubicon, reciprocally regulate autophagy at different stages. Nat Cell Biol 11:385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O'Brien JT, Feldman H et al (2005) Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 65:1863–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mercer CA, Kaliappan A, Dennis PB (2009) A novel, human Atg13 binding protein, Atg101, interacts with ULK1 and is essential for macroautophagy. Autophagy 5:649–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Miki Y, Mori F, Tanji K, Kakita A, Takahashi H, Wakabayashi K (2011) Accumulation of histone deacetylase 6, an aggresome‐related protein, is specific to Lewy bodies and glial cytoplasmic inclusions. Neuropathology 31:561–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nazio F, Strappazzon F, Antonioli M, Bielli P, Cianfanelli V, Bordi M et al (2013) mTOR inhibits autophagy by controlling ULK1 ubiquitylation, self‐association and function through AMBRA1 and TRAF6. Nat Cell Biol 15:406–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nixon RA, Yang DS (2011) Autophagy failure in Alzheimer's disease—locating the primary defect. Neurobiol Dis 43:38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Noda T, Ohsumi Y (1998) Tor, a phosphatidylinositol kinase homologue, controls autophagy in yeast. J Biol Chem 273:3963–3966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Odagiri S, Tanji K, Mori F, Kakita A, Takahashi H, Wakabayashi K (2012) Autophagic adapter protein NBR1 is localized in Lewy bodies and glial cytoplasmic inclusions and is involved in aggregate formation in α‐synucleinopathy. Acta Neuropathol 124:173–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Odagiri S, Tanji K, Mori F, Miki Y, Kakita A, Takahashi H et al (2013) Brain expression level and activity of HDAC6 protein in neurodegenerative dementia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 430:394–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Perry G, Roder H, Nunomura A, Takeda A, Friedlich AL, Zhu X et al (1999) Activation of neuronal extracellular receptor kinase (ERK) in Alzheimer disease links oxidative stress to abnormal phosphorylation. Neuroreport 10:2411–2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Qu X, Yu J, Bhagat G, Furuya N, Hibshoosh H, Troxel A et al (2003) Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the beclin1 autophagy gene. J Clin Invest 112:1809–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rohn TT, Wirawan E, Brown RJ, Harris JR, Masliah E, Vandenabeele P (2011) Depletion of Beclin‐1 due to proteolytic cleavage by caspases in the Alzheimer's disease brain. Neurobiol Dis 43:68–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Russell RC, Tian Y, Yuan H, Park HW, Chang YY, Kim J et al (2013) ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin‐1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nat Cell Biol 15:741–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Saito Y, Kawashima A, Ruberu NN, Fujiwara H, Koyama S, Sawabe M et al (2003) Accumulation of phosphorylated alpha‐synuclein in aging human brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 62:644–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sasaki S (2011) Autophagy in spinal cord motor neurons in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 70:349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schmelzle T, Hall MN (2000) TOR, a central controller of cell growth. Cell 103:253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM, Ames BN (1994) Oxidative damage and mitochondrial decay in aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91:10771–10778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sun Q, Fan W, Chen K, Ding X, Chen S, Zhong Q (2008) Identification of Barkor as a mammalian autophagy‐specific factor for Beclin 1 and class III phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:19211–19216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sun Q, Westphal W, Wong KN, Tan I, Zhong Q (2010) Rubicon controls endosome maturation as a Rab7 effector. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:19338–19343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tanji K, Kamitani T, Mori F, Kakita A, Takahashi H, Wakabayashi K (2010) TRIM9, a novel brain‐specific E3 ubiquitin ligase, is repressed in the brain of Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Dis 38:210–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tanji K, Mori F, Kakita A, Takahashi H, Wakabayashi K (2011) Alteration of autophagosomal proteins (LC3, GABARAP and GATE‐16) in Lewy body disease. Neurobiol Dis 43:690–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tanji K, Odagiri S, Maruyama A, Mori F, Kakita A, Takahashi H et al (2013) Alteration of autophagosomal proteins in the brain of multiple system atrophy. Neurobiol Dis 49:190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tanji K, Tanaka T, Mori F, Kito K, Takahashi H, Wakabayashi K et al (2006) NUB1 suppresses the formation of Lewy body‐like inclusions by proteasomal degradation of synphilin‐1. Am J Pathol 169:553–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Van Humbeeck C, Cornelissen T, Hofkens H, Mandemakers W, Gevaert K, De Strooper B et al (2011) Parkin interacts with Ambra1 to induce mitophagy. J Neurosci 31:10249–10261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wakabayashi K, Hayashi S, Kakita A, Yamada M, Toyoshima Y, Yoshimoto M et al (1998) Accumulation of α‐synuclein/NACP is a cytopathological feature common to Lewy body disease and multiple system atrophy. Acta Neuropathol 96:445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wakabayashi K, Tanji K, Odagiri S, Miki Y, Mori F, Takahashi H (2013) The Lewy body in Parkinson's disease and related neurodegenerative disorders. Mol Neurobiol 47:495–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. White E (2012) Deconvoluting the context dependent role for autophagy in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 12:401–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wong E, Bejarano E, Rakshit M, Lee K, Hanson HH, Zaarur N et al (2012) Molecular determinants of selective clearance of protein inclusions by autophagy. Nat Commun 3:1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yan JQ, Yuan YH, Gao YN, Huang JY, Ma KL, Gao Y et al (2014) Overexpression of human E46K mutant α‐synuclein impairs macroautophagy via inactivation of JNK1‐Bcl‐2 pathway. Mol Neurobiol 50:685–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yue Z, Jin S, Yang C, Levine AJ, Heintz N (2003) Beclin1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad U S A 100:15077–15082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhang HX, Tanji K, Mori F, Wakabayashi K (2008) Epitope mapping of 2E2‐D3, a monoclonal antibody directed against human TDP‐43. Neurosci Lett 434:170–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhong Y, Wang QJ, Li X, Yan Y, Backer JM, Chait BT et al (2009) Distinct regulation of autophagic activity by Atg14L and Rubicon associated with Beclin 1‐phosphatidylinositol‐3‐kinase complex. Nat Cell Biol 11:468–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. (A–E) Specificity of the primary antibodies. Anti‐ULK1, anti‐ULK2 and anti‐VPS34 antibodies recognizing bands of similar molecular size (about 100 kDa) in human, mouse and rat brain (arrows). Anti‐Beclin1 and anti‐p‐Beclin1 antibodies detecting bands of about 52 kDa (arrows). (F) Anti‐AMBRA1 antibody detecting a very weak band of its molecular weight 150 kDa (arrow). (G) Anti‐AMBRA1 antibody (Novus Biologicals) revealing positive immunolabeling of LBs in PD. Two other anti‐AMBRA1 antibodies (ProSci‐incorporated and Cell Signaling Technology) showing similar immunostaining of LBs. (H) Anti‐AMBRA1 antibody detecting a band of 150 kDa, corresponding to a band of FLAG‐AMBRA1. Bar = 10 μm.

Figure S2. No induction of autophagy after treatments of transfection reagent or EGFP–vector control in the results of three independent analyses.