Abstract

Neuronal loss in specific brain regions and neurons with intracellular inclusions termed Lewy bodies are the pathologic hallmark in both Parkinson's disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Lewy bodies comprise of aggregated intracellular vesicles and proteins and α‐synuclein is reported to be a major protein component. Using human brain tissue from control, PD and DLB and light and confocal immunohistochemistry with antibodies to superoxide dismutase 2 as a marker for mitochondria, α‐synuclein for Lewy bodies and βIII Tubulin for microtubules we have examined the relationship between Lewy bodies and mitochondrial loss. We have shown microtubule regression and mitochondrial and nuclear degradation in neurons with developing Lewy bodies. In PD, multiple Lewy bodies were often observed with α‐synuclein interacting with DNA to cause marked nuclear degradation. In DLB, the mitochondria are drawn into the Lewy body and the mitochondrial integrity is lost. This work suggests that Lewy bodies are cytotoxic. In DLB, we suggest that microtubule regression and mitochondrial loss results in decreased cellular energy and axonal transport that leads to cell death. In PD, α‐synuclein aggregations are associated with intact mitochondria but interacts with and causes nuclear degradation which may be the major cause of cell death.

Keywords: alpha synuclein, confocal microscopy, immunohistochemistry, microtubules, mitochondria, neurodegeneration

Introduction

The detection of Lewy bodies at autopsy has long been considered the pathogenic hallmark of Parkinson's disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). The mechanisms which cause the formation of Lewy bodies and whether they are toxic are two key questions that need to be answered to understand the disease process. α‐synuclein is a major component of Lewy bodies and much of the reported toxicity of Lewy bodies is centered around the toxicity of α‐synuclein and whether soluble or fibrillar forms are more toxic 4, 5, 7, 32, 33. While a number of mutations in the α‐synuclein gene results in familial PD the fact that a triplication leading to elevated production of normal α‐synuclein also leads to early onset PD suggests that normal α‐synuclein can also be toxic and cause neuronal loss. 27. Although it is argued that the elevated level of α‐synuclein is responsible for the pathology, the triplication site does cover 17 putative genes which might also be involved 27. This raises an interesting question as it has been reported that normal α‐synuclein is a stable tetramer that resists aggregation suggesting other components are also involved 2. The question of whether α‐synuclein is toxic prior to the formation of Lewy bodies has not been resolved and some consider that the aggregation and the formation of Lewy bodies are a mechanism for detoxifying α‐synuclein and other aggregated proteins 12, 14, 19, 30, 31, 33. There is considerable evidence to suggest that oligomerization, fibrillization and aggregation of α‐synuclein is responsible for the toxicity of α‐synuclein in vitro but how this results in neurodegeneration in the human brain is unclear.

While α‐synuclein is a component of Lewy bodies, there are many other proteins that have been identified that suggest the involvement of microtubules, mitochondria, lysosomal and autophagy pathways 8, 15, 16, 17, 31. These data suggest that Lewy bodies are probably not the result of unbound cytosolic protein aggregation but the result of vesicular aggregation due to the accumulation of multiple intracellular trafficking pathways. There are several reports using a variety of models suggesting that mutant or modified α‐synuclein can induce the unfolded protein response within the endoplasmic reticulum and cell death 28, 29. In addition, in yeast models it has been reported that α‐synuclein blocks endoplasmic reticulum trafficking vesicles from docking with the Golgi apparatus resulting in vesicular accumulation 6, 14. Other research in cell culture has shown that disruption of the proteasome results in centrosomal aggregates which alters microtubule nucleation and disruption of the trans‐Golgi network. Olanow et al have suggested that Lewy bodies are a dysfunctional aggresome which forms at the centrosome in response to proteolytic stress to facilitate the clearance of sequested proteins 22. There is general consensus that α‐synuclein fibrils and aggregation are toxic but if these aggregations are contained within a trafficking vesicle they might not be so toxic to the neuron. There is now a body of literature suggesting that some form of vesicular aggregation is involved in the formation of the Lewy body but whether the Lewy body itself is toxic has been difficult to address. Lewy bodies are reported to pass through a range of developmental stages. Gai et al have reported in a confocal microscopy study that Lewy bodies start as an unstructured mass of vesicles which progressively become ordered with rings of specific proteins. Lipids occupy the central region with concentric rings of α‐synuclein and ubiquitin 10. This vesicular structure with intact mitochondria can be seen using electron microscopy 10. Wakabayashi and et al (31,32) have also reported a similar progression in a detailed light microscopy study of brain stem Lewy bodies, suggesting pale bodies progress through stages to feed the development of a typical Lewy body with a halo similar to those described by Gai et al. In this article, we have examined the distribution of Lewy bodies in early and mature stages in relation to microtubules, mitochondria and nuclear material and show how the developing Lewy body results in neuronal degeneration in both conditions.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

The SOD2 antibody was raised against the N‐terminal of SOD2 and produced one clean band at 24kD on brain tissue homogenates and produced punctate staining with immunohistochemistry of brain tissue. Karnati S et al have recently reported that SOD2 is exclusively a specific mitochondrial protein 13.

α‐Synuclein antibodies were raised in sheep against human α‐synuclein peptide sequence 116–131. The antibodies were affinity‐purified using the antigen and extensively characterized as described. 3, 9, 10, 12, 23.

Details of the antibodies used in these experiments are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of antibodies and dilutions used to conduct this work.

| Antibody | Species | Dilution | Supplier Code | Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary antibodies | ||||

| Superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) | Rabbit |

1/1500 LM 1/200 CM |

ab86087 | Abcam plc, Cambridge, UK |

| Mitochondrial Marker MTCO2 | Mouse | 1/100 | ab3298 | Abcam plc, Cambridge, UK |

| alpha synuclein | Sheep | 1/250 | AS3SB | Antibody Technology Australia Pty, Ltd, Adelaide, Australia. |

| βIII Tubulin | Mouse | 1/100 | G712A | Promega Corporation, Madison, USA. |

| Secondary antibodies | ||||

| Donkey anti mouse | Cy3 | 1/200 | 715‐165‐151 | Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, USA |

| Donkey anti mouse | DyLight 488 | 1/100 | 715‐485‐150 | Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, USA |

| Donkey anti rabbit | Cy3 | 1/200 | 711‐165‐152 | Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, USA |

| Donkey anti rabbit | DyLight488 | 1/100 | 711‐485‐152 | Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, USA |

| Donkey anti sheep | Cy5 | 1/200 | 713‐175‐003 | Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, USA |

| Donkey anti sheep | Alexa 488 | 1/100 | 713‐545‐147 | Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, USA |

| Donkey anti rabbit | Biotin | 1/2000 | 711‐065‐152 | Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, USA |

Brain tissue

The brain tissue was obtained from the National Health and Medical Research Council South Australian Brain Bank with ethics approval from the Flinders Clinical Research Ethics Committee. PD and DLB cases were diagnosed using the revised criteria for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis according to the third report of the DLB consortium 18. The control cases were obtained from people who died of unrelated causes without diagnosed neurological disease and absence of LB pathology confirmed by neuropathological examination. Multiple sections at different depths from each block were analyzed. Cortical Lewy bodies are relatively sparse and every Lewy body and α‐synuclein aggregation on each section was photographed using confocal microscopy. Each Lewy body or α‐synuclein aggregation had to include a neuronal nucleus to be included. Similarly all the nigra Lewy bodies with a nucleus were photographed.

Details of PD, DLB and control tissue used in these experiments are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of cases used for histology and immunohistochemistry.

| Case number | Sex | Age (yr) | Diagnosis | Region | PMI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | F | 85 | PD | CG, MFG, SN | 12 |

| P2 | F | 83 | PD | CG, MFG, SN | 24 |

| P3 | F | 91 | PD | CG, MFG, SN | 24 |

| P4 | F | 73 | PD | CG, MFG, SN | 21 |

| D1 | M | 69 | DLB | CG, MFG | 31 |

| D2 | M | 79 | DLB | CG, MFG | 24 |

| D3 | F | 81 | DLB | CG, MFG | 7 |

| D4 | M | 80 | DLB | CG, MFG | 6 |

| C1 | F | 79 | ALC | CG, MFG | 4 |

| C2 | F | 61 | AC | CG, MFG | 8 |

| C3 | F | 71 | MI | CG, MFG | 7 |

| C4 | F | 86 | MLI | CG, MFG | 6 |

PMI = post mortem interval; PD = Parkinson's disease; DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies disease; C = Control; M = male; F = female; CG = Cingulate gyrus; MFG = middle frontal gyrus; SN = substantia nigra; ALC = adeno lung carcinoma; Unk = unknown; AC = acidosis; MI = myocardial infarct; MLI = multiple lacunar infarcts.

Immunohistochemistry

Both light and confocal microscopies were used in these studies. Light microscopy was used to examine single labeled experiments while confocal was used in multi labeled studies. The each channel of the confocal microscope was set up to only receive a narrow band of the emitted wavelength of each fluorophore and each scan was done sequentially to eliminate bleed through from adjacent fluorophores. The nuclear dye Dapi was used specifically to detect DNA and the Dapi channel was set to 405 to 480 nm. When Dapi binds to RNA it emits a signal at 500 nm would not be detected.

Light microscopy

PD, DLB and control brain sections from cases shown in Table 2 were deparaffinized, subjected to high temperature/EDTA antigen retrieval, treated with hydrogen peroxide and blocked with normal horse serum and then incubated for 18 h with rabbit SOD2 antibodies and pre‐immune serum as a negative control as previously described 24. The primary antibodies were visualized with biotinylated donkey anti‐rabbit secondary antibodies (Jackson) and the antibody complex visualized using a Vector ABC kit (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) and DAB substrate (Sigma‐Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Sections were examined and photographed with an Olympus BX50 microscope (Tokyo, Japan) linked to a QImaging Micro Publisher 5.0 RTV camera (Canada).

Colocalization of mitochondrial SOD2 and MTCO2 and mitochondrial SOD2 and Lewy bodies

PD, DLB and control brain sections were deparaffinized and subjected to high temperature/EDTA antigen retrieval. The sections were then blocked with normal horse serum and then incubated for 18 h with rabbit antibodies against SOD2 and mouse MTCO2 antibodies to further confirm both antibodies were localized to mitochondria. SOD2 was also colocalized with α‐synuclein to examine the relationship between mitochondria and Lewy bodies. Sections were examined using a Leica TSC SP5 Confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

Colocalization of SOD2 (mitochondria), α‐synuclein (Lewy body patgy) and βIII tubulin (microtubules)

PD, DLB and control brain sections were deparaffinized and subjected to high temperature/EDTA antigen retrieval. The sections were then blocked with normal horse serum and then incubated for 18 h with rabbit antibodies against SOD2 and sheep antibodies against α‐synuclein and mouse antibodies against βIII Tubulin. The primary antibodies were visualized using secondary antibodies conjugated to the following fluorescent fluorophores donkey anti rabbit Cy3 (Jackson) and donkey anti‐sheep Cy5 (Jackson) and donkey anti‐mouse Alexa 488 (Jackson Immunoresearch). In all cases the confocal scanning Z position was set to achieve the maximum size of the Lewy body.

Results

Light microscopy

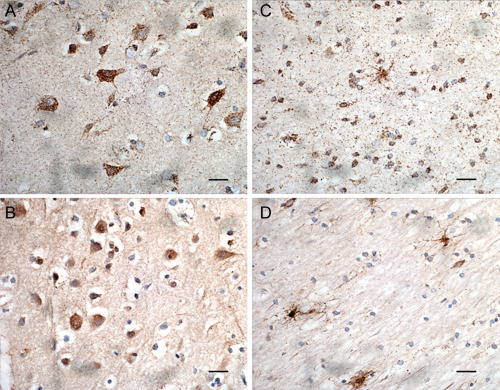

Light microscopy using the SOD2 antibody and DAB staining indicated that SOD2 was present in most brain cells in control tissue. The staining was punctate and was visible in the cell bodies and in the axons scattered throughout the tissue in both white and grey matter (Figure 1A,C). The profile was different in DLB tissue with most cells in the gray matter showing a more diffuse staining and with less staining in the surrounding tissue. The contrast was much more pronounced in the DLB white matter with the astrocytes exhibiting strong staining but the surrounding axonal tissue was almost devoid of punctate staining (Figure 1B,D).

Figure 1.

Light immunohistochemistry (DAB substrate) showing SOD2 (1/1500) staining of cells in control tissue gray matter (A), control tissue white matter (C), DLB tissue gray matter (B), DLB tissue white matter (D). Bar = 20 μm.

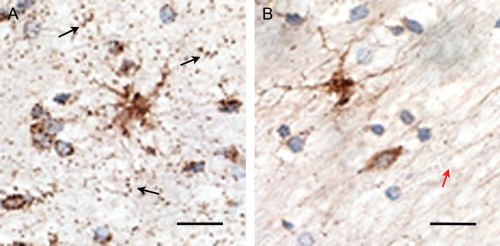

At higher magnification the difference within the white matter is more pronounced (Figure 2A,B). In the white matter in control tissue the mitochondrial SOD2 staining within the astrocytes and oligodendrocytes is clearly visible and with very distinct staining within the surrounding axons. In the DLB tissue, there was a similar staining in the astrocytes but very little staining in oligodendrocytes and the surrounding axons. The staining in the few mitochondria within the axons was much less intense than in control tissue.

Figure 2.

Light immunohistochemistry using SOD2 antibodies (1/1500) (DAB substrate) at oil immersion (1000×) showing punctate staining of mitochondria within the axons in control tissue in mid frontal gyrus white matter (black arrows) (A). Reduction in the levels of SOD2 staining in the axons in DLB mid frontal gyrus white matter (red arrow) (B). Bar = 20 μm.

Confocal microscopy

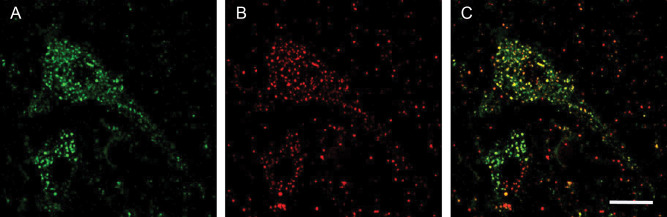

Colocalization of SOD2 and MTC02 mitochondrial markers

Although SOD2 is a mitochondrial protein it was colocalized with MTC02 another reported known mitochondrial marker (Abcam) to confirm the cellular location. Figure 3 shows almost complete colocalization between both proteins. The intensity varies slightly between different mitochondria but both antigens are present in all mitochondria.

Figure 3.

Confocal localization of the nuclear dye Dapi, SOD2 and MTCO2 in control tissue, [(A), SOD2 (1/200), DyLight™ 488‐green; (B) MTCO2 (1/100), Cy3‐red; (C) merged image; bar = 10 μm.

Colocalization of SOD2 and α‐synuclein in DLB

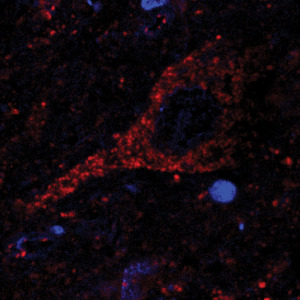

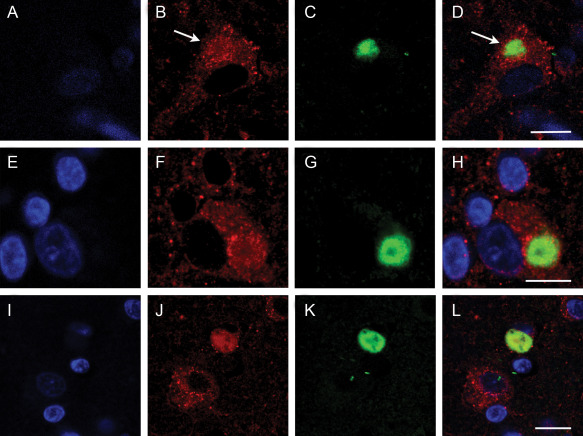

Colocalization of SOD2 and α‐synuclein showed that there was a progressive association of mitochondria with α‐synuclein aggregations in DLB and PD Lewy bodies. In normal neurons, there is an even distribution of mitochondria throughout the cell body and along axons (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Confocal localization of the nuclear dye Dapi, SOD2 (1/200) (Cy3 red) in neurons in DLB tissue.

In DLB cortical neurons with an aggregation of α‐synuclein, mitochondria can be seen to be attracted to the α‐synuclein aggregation (Figure 5D,H). As the aggregation develops into a Lewy body more mitochondria are sequested into the Lewy body and they form a ring around the periphery. Mitochondria within the Lewy body appear to lose their structure and the staining of SOD2 becomes diffuse (Figure 5I). As the Lewy body develops further, most of the neuronal mitochondria are sequested into the Lewy body and appear to be destroyed. The SOD2 staining becomes completely amorphous indicating a loss of mitochondrial structure (Figure 5I). In Figure 5, it can be seen that normal neurons nearby have discreet punctate mitochondrial staining evenly distributed throughout the neuron similar to that shown in Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Confocal localization of the nuclear dye Dapi, SOD2 (1/200) (Cy3 red) and α‐synuclein (1/250) (DyLight™ 488‐green) in neurons in DLB tissue. Panel A,E,I, Dapi; B,F,J, SOD2; C,G,K, α‐synuclein; and D,H,L, merged image. White arrows indicate accumulating mitochondria with the early stage Lewy body in a DLB neuron. Bar = 10 μm.

Colocalization of SOD2 and α‐synuclein in PD

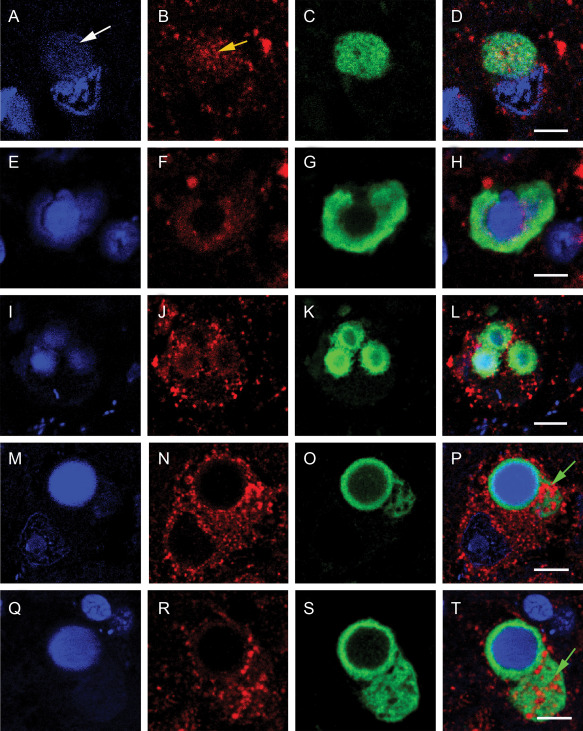

In PD, the profile is different and a more diverse range of Lewy body forms are evident in the substantia nigra (Figure 6). The process appears to start as an aggregation of α‐synuclein in the neuronal cytoplasm with the sequestration of mitochondria similar to DLB. The process also appears to have an effect on the neuronal nucleus as this appears to degrade (Figures 6a and 7). As this process continues there is further nuclear degradation. α‐Synuclein aggregation is associated with the mitochondria (Figure 6 green arrows) but is not associated with α‐synuclein when it forms a ring structure around degrading nuclear material.

Figure 6.

Confocal localization of the nuclear dye Dapi, SOD2 (1/200) (Cy3 red) and α‐synuclein (1/250) (DyLight™ 488‐green) in neurons in PD tissue. Panel (A,E,I,M,Q) Dapi; (B,F,J,N,R) SOD2; (C,G,K,O,S) α‐synuclein; and (D,H,L,P,T) merged image. White arrow show unraveling DNA (enlarged in Figure 7). Yellow arrow indicates accumulating mitochondria with the early stage Lewy body in a PD neuron. Green arrow show accumulating mitochondria within α‐synuclein aggregation in a complex PD Lewy body. Bar = 5 μm.

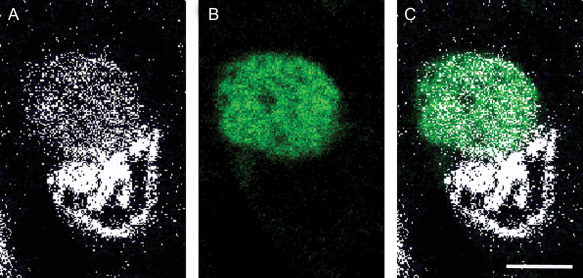

In substantia nigra Lewy body formation in PD nuclear degradation appears to be a key event. In Figure 7, it can be seen that nuclear material is extruding from the nuclear membrane when associated with a Lewy body. In more defined Lewy bodies (Figure 6M–T) with a ring structure, the nucleus has lost its integrity and is of an amorphous nature surrounded by α‐Synuclein. Nuclear involvement was not seen in DLB to the same extent (Figure 5).

Figure 7.

High power confocal localization of the nuclear dye Dapi [panel (A), converted to white] and α‐synuclein panel (B) (white arrow in figure 6) and merged image panel (C). Bar = 5 μm.

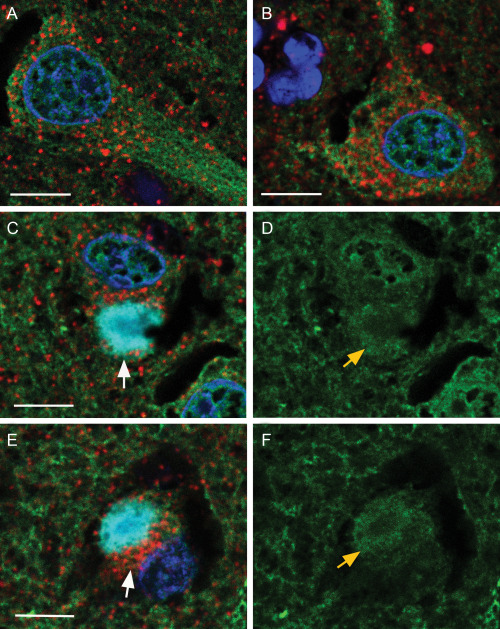

Colocalization of SOD2, α‐synuclein and βIII tubulin in DLB

In both PD and DLB neurons without Lewy bodies there is an even distribution of mitochondria throughout the cells which appear to line up along microtubules which occupy a large proportion of the cell body and axons as shown in the DLB (Figure 8A,B). In neurons with a Lewy body in DLB Figure 8C–F the microtubules are retracted into the Lewy body (yellow arrows) and drag the mitochondria to the Lewy body. This first appears as a ring around the Lewy body (white arrows) (Figures 5 and 8C,E, DLB); and Figure 6 (PD), then the mitochondria are incorporated into the Lewy body and the punctate staining is lost. Eventually the majority of the microtubules are incorporated into the Lewy body and the neuron is depleted of mitochondria. This is clearly seen in Figure 8C,D,E,F.

Figure 8.

Confocal localization of the nuclear dye Dapi, SOD2 (mitochondria, 1/200, Cy3 red), βIII tubulin (microtubules, 1/100, DyLight™ 488‐green) and α‐synuclein (Lewy bodies, 1/250, Cy5 blue) in neurons in control and DLB tissue. Panels (A, B)—two merged images in control cells. Panels (C, D) and (E, F)—merged image of a neurons with a Lewy body (C, E) and respective microtubules (D, F). White arrows show mitochondria associated with Lewy body. Yellow arrows shows wound up microtubules. Bar = 10 μm.

Discussion

Superoxide dismutase is a key mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme located in the mitochondria and inactivates the superoxide radical generated during cellular respiration. In the human brain tissues examined it is present in all cells. This antibody was characterized using Western blots and detected a molecular weight of 22 kD which is the reported molecular weight of SOD2. The protein ran as one clean band under both reducing and nonreducing conditions in control, PD and DLB mid frontal gyrus brain tissue (Data supplied but not shown). To confirm that SOD2 was specific for mitochondria it was colocalized with another mitochondrial marker MTCO2 which is raised against the full length native human cytochrome C oxidase subunit II. SOD2 is a component of the mitochondrial matrix while cytochrome C is a component of the mitochondrial inner membrane. Both antibodies indicated that these proteins were colocalized to mitochondria to varying degrees, this variation most likely due to each antigen being localized to a different mitochondrial compartment.

Light immunohistochemistry using this SOD2 antibody showed marked differences in the staining between control and DLB tissue. In control gray matter the staining was punctate in both the neuronal cell body and in the nerve processes which gave the neuropil a “spotted” appearance. The staining was still present in the neurons in DLB gray matter but the pattern was more diffuse with less staining in the processes. This profile was even more pronounced in the white matter where the staining in the processes in the control tissues was very distinct. In DLB white matter the processes were almost devoid of staining yet the astrocytes cell bodies were heavily stained. This profile suggests there is marked mitochondrial loss in neural tissue in DLB. The neuronal cell bodies in DLB still exhibited strong staining, although the staining was more diffuse than in control tissue. Examination of the same tissue with the astrocyte marker GFAP and with the neurofilament marker N200 indicated that this loss was due to a decrease in astrocytic processes and axonal breaks (data supplied but not included).

The relationship between SOD2 positive mitochondria and Lewy body pathology was also examined. Lewy body structure in the cortical regions in DLB and within the dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra in PD show similarities but also marked differences. Lewy bodies in both conditions are intracellular inclusions containing a high concentration of α‐synuclein. In DLB it is rare to find more than one inclusion per neuron but in PD multiple inclusion are often seen with a wider variety of structures. In this study, we have examined the relationship between mitochondria and α‐synuclein aggregations and the development of Lewy bodies in DLB and PD.

In DLB, when α‐synuclein begins to aggregate (pre‐Lewy body stage) in neurons as seen in Figure 6, the mitochondria are drawn to the aggregation which partially depletes the remaining cytoplasm. As the Lewy body develops and occupies more of the neuronal cytoplasm it attracts increasing amounts of the mitochondria. This is initially seen as a ring of punctate staining around the periphery of the Lewy body but as the mitochondria are incorporated into the center of the Lewy body the staining becomes diffuse indicating the mitochondrial integrity is lost. This is highlighted in Figure 6 (bottom image) where two cells are shown, one with a full complement of punctate mitochondria and the other containing a Lewy body with a mass of diffuse staining. In DLB the neuronal nucleus of cells with Lewy bodies remains relatively intact but with a low level of Dapi staining in some Lewy bodies indicating that some nuclear material is incorporated. Recently, Müller et al quantified mitochondrial DNA deletions in PD with age‐matched controls and showed increased mitochondrial DNA damage in LB‐positive midbrain neurons 20. This is consistent with this study as mitochondria are degraded as they are incorporated into Lewy bodies.

In Lewy body containing neurons in the substantia nigra of PD tissue a greater range of structures were observed. α‐Synuclein aggregation appears to develop in some cells in a diffuse manner similar to DLB and where the aggregation attracts mitochondria. The aggregating α‐synuclein appears to have a more detrimental effect on the neuronal nucleus in PD. In Figure 7A–D and expanded in Figure 8 the α‐synuclein aggregation is associated with unraveling nuclear material. In many substantia nigra neurons with Lewy bodies the α‐synuclein aggregation has formed around a diffuse aggregation of unstructured nuclear material. Whether the α‐synuclein has caused the nuclear damage or if the nuclear damage proceeded the α‐synuclein accumulation is difficult to determine. These results indicate that α‐synuclein has an affinity for nuclear material as shown in Figure 7E–H, which is consistent with several recent reports 11, 21, 25. It appears that there are two processes involved. There are the diffuse α‐synuclein aggregations and the attraction of mitochondria as seen in Figure 7P,T (green arrows) and the enveloping of unstructured nuclear material (Figure 7H,L,P,T). In both cases, the α‐synuclein aggregation has attracted the mitochondria as seen in the ring structure of Figure 7N,R. The rings of α‐synuclein surrounding DNA material was not see in DLB and the Lewy bodies in PD appear far more complex. An additional difference between the Lewy bodies in the cortical cells in DLB and substantia nigra cells in PD is that in DLB the mitochondria are incorporated into the Lewy body and their staining becomes diffuse suggesting complete loss of structure. In the substantia nigra, the mitochondria remained intact but the nucleus became degraded which may have implications for the mechanism of cell death in each disease. These data are consistent with the finding of Reeves et al which showed in a single neuron study in the substantia nigra that there was no direct association between mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction and the formation of α‐synuclein pathology 26.

Although speculation, it is likely that the depletion of mitochondria and the loss of cellular energy may well be the mechanism of cell death in DLB while in PD the loss of nuclear integrity and the effect on protein synthesis may be the cause of cell death. This concept supports the work of Alvarez‐Erviti et al who have suggested that miRNA‐induced downregulation of chaperone‐mediated autophagy proteins plays an important role in the α‐synuclein pathology associated with PD 1, as the loss of nuclear integrity would down regulate all mRNA production. The depletion of mitochondria from the cellular processes and cell body into the Lewy body were very clear in DLB. To examine this process whereby the mitochondria are drawn into the Lewy body we have colocalized the mitochondria, Lewy bodies and microtubles. Microtubules provide the mechanism for intracellular trafficking. In control tissues where the microtubules were parallel to the cut of the section it was clear that the mitochondria were aligned with the microtubules. In cells with a Lewy body in DLB tissue the microtubules appeared to be “wound up” and retracted and the mitochondria were dragged into the Lewy body. The mechanism of this process is unresolved but we have previously reported that the Lewy body probably follows a maturation process progressing from a collection of vesicles to a specific circular arrangement of proteins 9. We are suggesting that during this process microtubules are retracted into the Lewy body and bring along the mitochondria and other cellular components. First the mitochondria line up around the periphery of the mitochondria and are subsequently drawn into the Lewy body with loss of structural integrity. This process explains several phenomena, the decrease in cellular trafficking due to the loss of microtubules and mitochondria, why neuronal processes regress from the extremities to the cell body and explains why Lewy bodies contain a large number of intracellular proteins including the microtubule associated protein MAP‐1B 12, 31

In conclusion, we have shown that as Lewy bodies develop in both PD and DLB they draw in mitochondria from the periphery and the accumulating α‐synuclein interacts with nuclear DNA. This interaction appears to differ in PD and DLB as in PD α‐synuclein appears to degrade the nucleus and forms a tight ring around amorphous nuclear staining earlier in this process. These factors plus the loss of peripheral microtubules would lead to decreased axonal trafficking. The combined result is that Lewy bodies will result in depleted ATP, damaged DNA and reduced trafficking leading to cell death and neuronal loss.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web‐site:

Co‐localization of DNA Fluorophore dyes Acridine Orange with DAPI

DAB Immunostaining of Normal Control and DLB cases with Neurofilament and GFAP Antibodies

White matter processes

Neurofilament staining

Astrocytic Processes staining (GFAP)

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the excellent assistance of the Flinders University Microscopy and Image Analysis Facility. We also acknowledge the excellent service from the South Australian Brain Bank in supplying all the brain tissue used in this study.

Conflict of interest statement: None of the authors has any conflict of interest to declare with respect to this study.

References

- 1. Alvarez‐Erviti L, Seow Y, Schapira AHV, Rodriguez‐Oroz MC, Obeso JA, Cooper JM (2013) Influence of microRNA deregulation on chaperone‐mediated autophagy and a‐synuclein pathology in Parkinson's disease. Cell Death Dis 4;e545; doi:10.1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bartels T, Choi JG, Selkoe DJ (2011). α‐Synuclein occurs physiologically as a helically folded tetramer that resists aggregation. Nature 477:107–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Braak H, Sandmann‐Keil D, Gai WP, Braak E (1999) Extensive axonal Lewy neurites in Parkinson's disease: a novel pathological feature revealed by α‐synuclein immunocytochemistry. Neurosci Lett 265:67–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Choi BK, Choi MG, Kim JY, Yang Y, Lai Y, Kweon DH et al (2013) Large α‐synuclein oligomers inhibit neuronal SNARE‐mediated vesicle docking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:4087–4092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Colla E, Jensen PH, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Glabe C, Lee MK (2012) Accumulation of toxic α‐synuclein oligomer within endoplasmic reticulum occurs in α‐synucleinopathy in vivo. J Neurosci 32:3301–3305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cooper AA, Gitler AD, Cashikar A, Haynes CM, Hill KJ, Bhullar B et al (2006) α‐synuclein blocks ER‐Golgi traffic and Rab1 rescues neuron loss in Parkinson's models. Science 313:324–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Daturpalli S, Waudby CA, Meehan S, Jackson SE (2013) Hsp90 inhibits α‐synuclein aggregation by interacting with soluble oligomers. J Mol Biol 425:4614–4628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dehay B, Martinez‐Vicente M, Caldwell GA, Caldwell KA, Yue Z, Cookson MR et al (2013) Lysosomal impairment in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 28:725–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gai WP, Power JHT, Blumbergs PC, Culvenor JG, Jensen PH (1999) α‐Synuclein immunoisolation of glial inclusions from multiple system atrophy brain tissue reveals multiprotein components. J Neurochem 73:2093–2100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gai QP, Yuan HX, Power JHT, Blumbergs PC, Jensen PH (2000) In situ and in vitro study of colocalization and segregation of α‐synuclein, ubiquitin and lipids in Lewy bodies. Exp Neurol 166:324–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hegde ML, Rao KSJ (2007) DNA induces folding in α−synuclein: understanding the mechanism using chaperone property of osmolytes. Arch Biochem Biophys 464:57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jenson PH, Islam K, Kenney JM, Nielson MS, Power JHT, Gai W (2000) Microtubule‐associated protein 1B is a component of cortical Lewy bodies and bind α‐synuclein filaments. J Biol Chem 275:21500–21507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Karnati S, Lüers G, Pfreimer S, Baumgart‐Vogt E (2013) Mammalian SOD2 is exclusively located in mitochondria and not present in peroxisomes. Histochem Cell Biol 140:105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kincaid MM, Cooper AA (2007) Misfolded proteins traffic from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) due to ER export signals. Mol Biol Cell 18:455–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Klucken J, Poehler AM, Ebrahimi‐Fakhari D, Schneider J, Nuber S, Rockenstein E et al (2012) Alpha‐synuclein aggregation involves a bafilomycin A1‐sensitive autophagy pathway. Autophagy 8:754–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kramer ML, Schulz‐Schaeffer WJ (2007) Presynaptic alpha‐synuclein aggregates, not Lewy bodies, cause neurodegeneration in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurosci 27:1405–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leverenz JB, Umar I, Wang Q, Montine TJ, McMillan PJ, Tsuang DW et al (2007) Proteomic identification of novel proteins in cortical Lewy bodies. Brain Pathol 17:139–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O'Brien JT, Feldman H et al (2005) Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology 65:1863–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mori F, Nishie M, Kakita A, Yoshimoto M, Takahashi H, Wakabayashi K (2006) Relationship among α‐synuclein accumulation, dopamine synthesis, and neurodegeneration in Parkinson disease substantia nigra. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 65:808–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Müller SK, Bender A, Laub C, Högen T, Schlaudraff F, Liss B et al (2013) Lewy body pathology is associated with mitochondrial DNA damage in Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging 34:2231–2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Muralidhar, L. Hegde and Rao, KSJ (2007) DNA induces folding in α‐synuclein: understanding the mechanism using chaperone property of osmolytes. Arch Biochem Biophys 464:57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Olanow CW, Perl DP, DeMartino GN, McNaught KP (2004) Lewy‐body formation is an aggresome‐related process: a hypothesis. Lancet Neurol 3:496–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Power JHT, Asad S, Chataway TK, Chegini F, Manavis J, Temlett JA et al (2008) Peroxiredoxin 6 in human brain: molecular forms, cellular distribution and associations with Alzheimer's disease pathology. Acta Neuropathol 115:611–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Power JHT, PH, Blumbergs PC (2009) Glutathione peroxidase in human brain: cellular distribution and its potential role in the degradation of Lewy bodies in Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Acta Neuropathol 117: 63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Padmaraju V, Bhaskar JJ, Ummiti JS, Rao P, Salimath PV, Rao KS (2011) Role of advanced glycation on aggregation and DNA binding properties of α‐synuclein. J Alz Dis 24:211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reeve AK, Park T, Jaros E, Campbell GR, Lax NZ, Hepplewhite PD et al (2012) Relationship between mitochondria and α‐synuclein: a study of single substantia nigra neurons. Arch Neurol 69:385–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, Singleton A, Hague S, Kachergus J et al (2003) Alpha‐synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson's disease. Science 302:841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smith WW, Jiang H, Pei Z, Tanaka Y, Morita H, Sawa A et al (2005) Endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial cell death pathways mediate A53T mutant alpha‐synuclein‐induced toxicity. Hum Mol Genet 14:3801–3811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sugeno N, Takeda A, Hasegawa T, Kobayashi M, Kikuchi A, Mori F et al (2008) Serine 129 phosphorylation of α‐synuclein induces unfolded protein response‐mediated cell death. J Biol Chem 283:23179–23188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tanaka M, Kim YM, Lee G, Junn E, Iwatsubo T, Mouradian MM. (2004) Aggresomes formed by α‐synuclein and synphilin‐1 are cytoprotective. J Biol Chem 279:4625–4631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wakabayashi K, Tanji K, Mori F, Takahashi H (2007) The Lewy body in Parkinson's disease: molecules implicated in the formation and degradation of α‐synuclein aggregates. Neuropathology 27:494–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wakabayashi K, Tanji K, Odagiri S, Miki Y, Mori F, Takahashi H (2013) The Lewy body in Parkinson's disease and related neurodegenerative disorders. Mol Neurobiol 47:495–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wan OW, Kenny K, Chung K (2012) The role of alpha‐synuclein oligomerization and aggregation in cellular and animal models of Parkinson's disease. PLoS One 6:e38545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web‐site:

Co‐localization of DNA Fluorophore dyes Acridine Orange with DAPI

DAB Immunostaining of Normal Control and DLB cases with Neurofilament and GFAP Antibodies

White matter processes

Neurofilament staining

Astrocytic Processes staining (GFAP)

Supporting Information

Supporting Information