Abstract

Enterovirus A71 (EV‐A71) belongs to the species group A in the E nterovirus genus within the P icornaviridae family. EV‐A71 usually causes self‐limiting hand, foot and mouth disease or herpangina but rarely causes severe neurological complications such as acute flaccid paralysis and encephalomyelitis. The pathology and neuropathogenesis of these neurological syndromes is beginning to be understood. EV‐A71 neurotropism for motor neurons in the spinal cord and brainstem, and other neurons, is mainly responsible for central nervous system damage. This review on the general aspects, recent developments and advances of EV‐A71 infection will focus on neuropathogenesis and its implications on other neurotropic enteroviruses, such as poliovirus and the newly emergent Enterovirus D68. With the imminent eradication of poliovirus, EV‐A71 is likely to replace it as an important neurotropic enterovirus of worldwide importance.

Keywords: CNS, enterovirus, Enterovirus A71, neuropathogenesis, neurotropism

Introduction

Enterovirus 71 (EV‐A71) belongs to a large group of enteroviruses that traditionally includes poliovirus, coxsackievirus A and B, echovirus and other numbered enterovirus (enteroviruses discovered later and given unique consecutive numbers) 86. More recent classifications of enteroviruses have utilized viral genomic sequence to further refine the nomenclature 44. Currently, the Enterovirus genus in the Picornaviridae family includes nine species groups (species A to H and species J), each consisting of a varying number of enterovirus serotypes. Species group A (25 serotypes) comprises about half the original coxsackieviruses A, including coxsackievirus A16 (CV‐A16), and an important numbered enterovirus, EV‐A71. Species group B, the largest group (63 serotypes), comprises all coxsackieviruses B, echoviruses and numbered enteroviruses. Species group C (23 serotypes) comprises the three poliovirus serotypes, the rest of the coxsackieviruses A and numbered enteroviruses, and species group D (five serotypes) includes enterovirus D68 (EV‐D68). Human rhinovirus species groups have recently been included to the Enterovirus genus 44.

EV‐A71 and CV‐A16 are major causes of hand‐food‐mouth disease (HFMD) and herpangina in infants and young children. In addition, EV‐A71 infection has proven to be complicated by aseptic meningitis, acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) and encephalomyelitis 100. In fact, EV‐A71 was first isolated in 1969 from the feces of a 9 month old infant with fatal encephalitis in the USA 94. Since then, many large HFMD outbreaks with significant neurological complications and mortality have been reported worldwide in Europe, Australia, USA and Asia 39, 67, 68, 112. With the expected eradication of poliovirus, EV‐A71 could well emerge as the most prevalent neurotropic enterovirus. This review supplements previous reviews 67, 68, 85, 100 on the general aspects of EV‐A71 infection and on more recent developments and advances. How the pathology and neuropathogenesis of AFP and encephalomyelitis and impacts on our understanding of other neurotropic enteroviruses, including poliovirus and the newly emergent Enterovirus D68 (EV‐D68), will be discussed.

Virology

EV71 shares a common morphology and structure with other members of the Picornaviridae family. The non‐enveloped, symmetrically icosahedral virion of about 30 nm in diameter, is one of the smallest viruses 90. The virus capsid or protein shell is made up of 60 repeating units called protomers, each composed of four viral structural proteins (VP1 to VP4). The crystal structure of EV‐A71 has been recently determined at 3.8 Å resolution 88, 89. Enteroviruses are relatively stable viruses, insensitive to organic solvents and resistant to acid pH, thus their ability to survive conditions in the gastrointestinal tract 86.

The EV‐A71 genome is a single‐stranded, positive (+) sense RNA molecule of approximately 7.5 kb. It encodes for four structural proteins and several non‐structural proteins. The entire genome of some virus strains has been sequenced. Phylogenetic analysis of EV‐A71 strains using variations in the VP1 region, has been used to study the molecular epidemiology of outbreaks 68, 100. Based on these genomic variations, EV‐A71 was divided into three genogroups: A (prototype virus); B (B1‐B5) and C (C1‐C5). This has enabled epidemiologists and virologists to study the source and spread of the viruses across countries and continents. It was found that B1 and B2 genogroup viruses were predominant in Japan, Europe and the USA in the 70s and 80s. More recently, B3 to B5 genogroup viruses circulated in Southeast Asia, while genogroup C1 to C5 viruses were also detected in Southeast Asia, the Far East and Australia 68, 100.

Several putative virus receptors on host plasma membranes that enable EV‐A71 attachment and viral entry have been found, including the human scavenger receptor class B2 (SCARB2), P‐selectin glycoprotein ligand‐1 (PSGL‐1), annexin II, sialic acid, dendritic cell‐specific ICAM‐3 grabbing non‐integrin, nucleolin and heparin sulphate 54, 77, 101, 102, 119, 121, 122. Perhaps the best studied virus receptor is SCARB2, a ubiquitously expressed major transmembrane lysosomal protein. In the human CNS, SCARB2 was found mainly on neurons and glial cells. A human SCARB2 transgenic mouse model that demonstrated susceptibility to EV‐A71 infection and convincing similarity to HFMD complicated by encephalomyelitis was successfully developed recently, confirming SCARB2 as an important functional receptor 28. PSGL‐1, dendritic cell‐specific ICAM3 grabbing non‐integrin, and sialic acid are limited to leukocytes, dendritic cells, epithelial, and endothelial cells, respectively 54, 77, 121, 122. The ubiquitous heparin sulphate and nucleolin apparently could facilitate attachment but not viral entry 101, 102.

Viral Transmission

Like poliovirus, humans are the only natural hosts for EV‐A71. Person‐to‐person transmission is usually through fecal‐oral or oral‐oral routes, and sometimes via droplets 86. Viral isolation from throat swabs appears to be significantly higher than from rectal swabs or feces, suggesting that the oral‐oral route may be more important than the fecal‐oral route 82, 83. Moreover, detection of viral antigens and RNA in tonsillar crypt squamous epithelium but not in other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, suggests that the palatine tonsil and oral mucosa is the major source of viral shedding into the oral cavity, and very likely in the feces as well 34. As virus can be cultured from skin vesicles 82, 83, it is conceivable that cutaneous‐oral transmission could also occur but its relative significance is unknown. Figure 1 summarizes a hypothesis for the possible routes of viral entry into the body and the CNS, viral replication sites and shedding in Enterovirus 71 encephalomyelitis, based on available data from human and animal studies.

Figure 1.

A hypothesis for the possible routes of viral entry into the body and CNS, viral replication sites and viral shedding in Enterovirus 71 encephalomyelitis, based on available data from human and animal studies. While person‐to‐person transmission is mainly via fecal‐oral and oral‐oral routes, the portal/s for viral entry are unknown but likely to be via the palatine tonsil and oropharyngeal mucosa after viral replication in these tissues. Viral entry through the gastrointestinal tract could possibly occur as well. Viremia spreads infection to the skin and perhaps other organs where there is further viral replication. Neuroinvasion occurs through retrograde axonal transport up cranial and spinal motor nerves to infect motor nuclei and anterior horn cells in the brainstem and spinal cord, respectively. Within the CNS, motor and other neural pathways spread virus further. However, hematogenous spread into the CNS still cannot be excluded. As no gastrointestinal tract replication sites have been identified, the source of fecal viral shedding may be mainly the tonsil/oropharynx.

Clinical Manifestations

The incubation period after EV‐A71 infection is about 3 to 6 days 64. Uncomplicated EV‐A71 infection manifests as HFMD or the more localized herpangina 85. Typically, HFMD patients have a self‐limiting, acute febrile illness presenting with oral ulcers on the tongue and buccal mucosa, and vesicular or small erythematous maculopapular rashes on the hands, feet, knees or buttocks. Oral ulcerations in herpangina are similar to HFMD, except that they are more confined to the posterior oral cavity involving the buccal mucosa, tonsillar pillars, soft palate or uvula. HFMD and herpangina are considered to represent both ends of the clinical spectrum of mucocutaneous manifestations of EV‐A71 85.

The neurological complications are well known but rare in EV71 infection 37, 85. Aseptic meningitis is characterized by mononuclear infiltration in the meninges without involving the brain parenchyma. Meningitis may occur by itself or accompany HFMD/herpangina. AFP is characterized by acute limb weakness plus decreased reflexes without disturbance of limb sensation, similar to classical poliomyelitis. It is due to isolated infection of groups of anterior horn cells in the spinal cord. Encephalomyelitis is an inflammation involving both the brain and spinal cord. It often occurs with manifestations of HFMD/herpangina, but aseptic meningitis is invariably found. The typical encephalomyelitis patient presents with a few days of non‐specific fever, lethargy and very acute onset of neurological symptoms and signs, and often dies within hours of hospital admission 35, 37, 61. Encephalomyelitis is characterized by hyporeflexic flaccid muscle weakness, myoclonic jerks, ataxia, nystagmus, oculomotor and bulbar palsies and coma, in various combinations 112. Brainstem encephalitis or rhombencephalitis has been used to describe a similar syndrome without muscle weakness. In the terminal stages, there is autonomic dysregulation (cold sweating, mottled skin, tachycardia, hypertension, hyperglycemia, tachypnea), fulminant pulmonary edema and myocardial dysfunction 37. The four clinical stages of infection have been defined as: stage 1, HFMD/herpangina; stage 2, CNS involvement; stage 3, cardiopulmonary collapse; stage 4, convalescence/sequelae 35, 37. Most infections are stage 1, with some cases progressing to stage 2, and a few advancing to the most severe stage 3. The exact prevalence of severe neurological complications is unknown but is probably much less than 1%. In stage 4, patients may recover or develop significant neurological sequelae including cerebellar dysfunction, severe respiratory and motor impairment, delayed neurodevelopment and reduced cognitive function 14, 38.

Typically in encephalomyelitis, the T2 weighted MRI shows mainly hyperintense lesions in the spinal cord and brainstem 19, 21, 96. In the spinal cord, there was involvement of the anterior horns bilaterally and at all levels, continuing into the posterior areas of the medulla, pons and midbrain. More rarely, lesions may be found in the thalamus, frontal and parietal lobe white matter and other parts of the brain 96, 126. In AFP patients, lesions were confined to the anterior horn regions of the cord and ventral nerve roots 17, 18, 19.

Laboratory Diagnosis

As a biosafety level 2 virus, EV‐A71 isolation and identification in clinical specimens, eg, throat swabs and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), can be done in most laboratories and is the gold‐standard for diagnosis. For this purpose, human rhadomyosarcoma and Vero cells (African green monkey kidney cells) remain the most commonly used, and the cytopathic effects are characteristic. Isolated viruses can be identified by conventional neutralization tests, immunofluorescence staining using EV‐A71‐specific monoclonal antibodies or by specific reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) 85, 112. Overall, the rate of virus isolation from CSF is very low (<5%) compared to throat, vesicle and rectal swabs 82, 112. Recently, several new molecular diagnostic methods for simple, rapid identification of EV‐A71 in clinical specimens have been described, including nested RT‐PCR, real‐time RT‐PCR, reverse transcription loop‐mediated isothermal amplification and droplet digital PCR 29, 59, 97, 127.However, these new methods require specific primers (targeted to the VP1 gene) that have to be constantly revised accordingly to the prevalent EV‐A71 genogroups/variants in a new outbreak area.

Pathology of Fatal EV‐A71 Encephalomyelitis

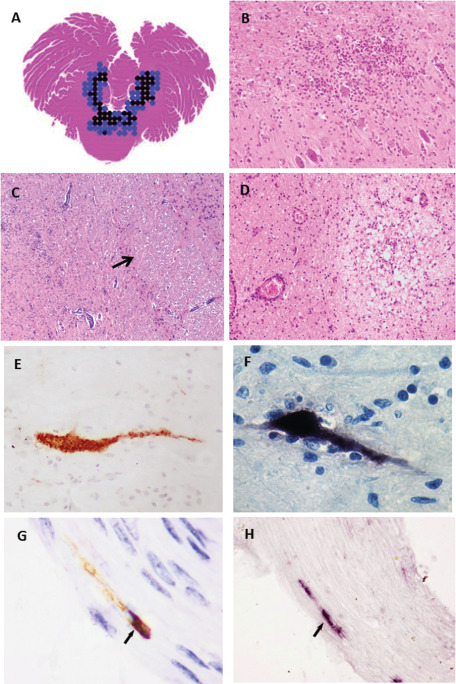

Based on autopsy cases, the pathology of EV‐A71 encephalomyelitis is beginning to be better understood 9, 10, 34, 36, 61, 98, 114, 120, 123, 125, 129. EV‐A71 encephalomyelitis showed a stereotyped distribution of inflammation in which the most intense inflammation was found in the spinal cord, brainstem (Figure 2A), hypothalamus and cerebellar dentate nucleus (Figure 2B). The inflammation was typical of viral encephalitis consisting of perivascular cuffing, edema, necrosis, microglial nodules and neuronophagia (Figure 2B–D). At all levels of the cord, the anterior horn cells showed direct evidence of neuronotropism with demonstrable viral antigens/RNA in neuronal bodies and processes (Figure 2E,F). Similarly, neuronal viral antigens/RNA may also be demonstrated in other inflamed areas in the medulla, pontine tegmentum/floor of the fourth ventricle (Figure 2A) and the midbrain posterior to the corticospinal tracts (crus cerebri), hypothalamus and subthalamic nucleus. However, viral antigens/RNA may be very focal even in severely inflamed areas. The cerebral cortex, shows much milder and less consistent inflammation mostly in the motor area. Inflammation was absent in the globus pallidus, putamen, caudate nucleus, thalamus, hippocampus, anterior pons and cerebellar cortex. The whole of the medulla, including the inferior olivary nucleus and cranial nerve nuclei, reticular formation and nucleus ambiguus area showed inflammation (Figure 2D). No viral inclusions were found. Some inflammatory cells around infected neurons may show phagocytosed viral antigens but generally, meninges, glial cells, blood vessels and choroid plexus were all negative for viral antigens/RNA. Mild meningitis was found throughout the CNS. Inflammatory cells were predominantly CD68+ macrophages and CD15+ neutrophils 114, 123. CD3+, CD8+ and CD20+lymphocytes, if present, were found sparsely in perivascular spaces or in the parenchyma 114, 123.

Figure 2.

A. Horizontal section of the whole cerebellum at the mid‐pons level from an autopsy of EV‐A71 encephalomyelitis in which the distribution of moderate (blue dots) and severe inflammation (black dots) was shown. The inflammation was confined to the tegmentum/floor of 4th ventricle (C) and dentate nucleus (B), sparing the anterior pons (C, arrow) and cerebellar hemisphere. Intense parenchymal inflammation, necrosis and perivascular cuffing was seen in the medulla (D). In inflamed areas, viral antigens (E) and RNA (F) were localized to infected neuronal bodies and processes with or without evidence of neuronophagia. In an experimental mouse model of encephalomyelitis infected by intramuscular injection into jaw/facial muscles, viral antigens (G, arrow) and RNA (H, arrow) were demonstrated in cranial nerves. Permissions to reproduce images were obtained for figure C 115 and for figure G and H 103.

Although lungs revealed marked pulmonary edema with multifocal hemorrhage with or without inflammation, viral antigens/RNA were not detectable. Myocarditis is generally absent or if present, is very mild 9, 120. Viral antigens/RNA were absent in the myocardium. The mesenteric lymph nodes, Peyer's patches, spleen and thymus showed congestion and/or reactive hyperplasia 34, 123, 129. In the palatine tonsil, viral antigens/RNA were demonstrated in squamous epithelium lining the crypts but not in the squamous epithelium covering the external surface nor in lymphoid cells or blood vessels 34. Viral antigens/RNA were not detected in the gastrointestinal mucosa, liver, pancreas, kidney and skeletal muscle fibers. EV‐A71 has been isolated from CNS tissues including cerebrum, cerebellum, pons, medulla, and spinal cord 37, 61, 120, and from non‐CNS tissues, including tonsils, intestines, pancreas, myocardium and blood. However, viral cultures from lungs, liver and kidney showed negative results 9, 22.

Neuropathogenesis of EV‐A71 Encephalomyelitis

Neuronotropism was first demonstrated in autopsy cases of EV‐A71 encephalomyelitis from a HFMD outbreak in Malaysia in 1999 10, 61, 113. Viral antigens/RNA were detected mostly in neurons that were undergoing neuronophagia or degeneration, suggesting that viral cytolysis is an important mechanism for tissue injury. Several recent animal models of EV‐A71 infection, including mouse and monkey models, have since confirmed viral neuronotropism and cytolysis 28, 75, 76, 80, 128. However, other mechanisms of tissue injury, eg, immune mediated or bystander effects, cannot be excluded because neuronal viral antigens/RNA were often more focal than expected from the extent and severity of inflammation 114. There is a possibility that following EV‐A71 infection, apoptosis or autophagy may occur as demonstrated in vitro and in animal studies 25, 40, 48, 99, 111, 118. However, we have been unable to demonstrate apoptosis in our series of encephalomyelitis cases (unpublished observation).

Based on the stereotyped distribution of inflammation and viral antigens/RNA in human autopsies supported by findings in a mouse model, it was postulated that viral entry into the CNS may be via peripheral motor nerves 80, 114. As peripheral motor nerves originate in cord anterior horn cells, these neurons will be the first to be infected. It was reported in a mouse model that efferent motor axons adjacent to infected anterior horn cells in the spinal cord could be infected 80. Furthermore, cranial motor nerves (Figure 2G,H) could similarly facilitate viral retrograde axonal transport to reach the murine brainstem motor nuclei and reticular formation after intramuscular injection of virus into the jaw muscles 103. Being the first neurons to be infected, it is not surprising that motor and adjacent neurons in the spinal cord, medulla, pons and midbrain showed the most severe inflammation. The mild inflammation in the motor cortex is consistent with a delay in viral spread from cord/brainstem motor nuclei to the motor cortex via motor pathways. Other neural pathways may also be involved with viral transmission as the severely inflamed dentate nucleus is not directly connected to motor pathways. Interestingly, in contrast to the severely inflamed inferior olivary nucleus with which it has direct neural connections, the cerebellar cortex was never found to be inflamed. Like poliomyelitis, it is assumed that AFP is due to a localized, focal infection of a group of motor neurons in the spinal cord. Based on data from mouse models, which demonstrated severe skeletal muscle infection before CNS involvement, it is tempting to speculate that virus spreads from skeletal muscle to motoneuron junctions, up peripheral motor nerves and thence into the motor nuclei in the CNS 81, 103. However, human skeletal muscle infection has not be demonstrated.

Hematogenous spread of virus through the blood–brain barrier (BBB) has not been well studied and cannot be excluded. In in vitro experiments, EV‐A71 was able to infect, activate and/or induce apoptosis in human endothelial cells suggesting that viral penetration into the CNS via the BBB may be possible 53, 63. Intraperitoneal or intravenous inoculation in mouse and monkey models was followed rapidly by CNS infection presumably as a result of viremia but it is difficult to demonstrate if neuroinvasion was due to a breach in the BBB or due to virus entering skeletal muscle/motor nerves 28, 76, 80. Assuming that virus is able to cross the BBB, it may preferentially infect certain groups or types of neurons, eg, motor neurons, resulting in the stereotyped distribution of inflammation and viral antigens/RNA in the CNS.

Pulmonary edema and cardiopulmonary collapse, both terminal events in encephalomyelitis, may be related to neurogenic pulmonary edema 100, a concept that has been described in sudden deaths in bulbar poliomyelitis and other CNS diseases 4. As reviewed recently, there may a complex interplay of various pathogenetic mechanisms involving a cytokine storm of inflammatory mediators arising from strong systemic and CNS inflammatory responses and an excessive sympathetic hyperactivity/catecholamine release as a result of brainstem encephalitis 100. The end result is cardiotoxicity/dysfunction and acute pulmonary edema. Proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF‐α, IL‐1β, IL‐6, IL‐10, IL‐13 and IFN‐γ, and chemokines such as IL‐8, IFN‐γ induced protein, monocyte chemoattractant protein, monokine induced by IFN‐γ, were found to be increased in the cerebrospinal fluid and/or plasma in patients with brainstem encephalitis with or without pulmonary edema 109. Most of these inflammatory mediators that form part of the cytokine storm, except TNF‐α, IL‐1β, IL‐8 and IFN‐γ, could modulate changes in pulmonary vascular permeability to cause pulmonary edema. Pulmonary edema apparently could not be explained by hemodynamic factors because patients initially had normal cardiac function, pulmonary artery pressure and vascular resistance. Depletion of CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes, natural killer cells and lowered EV‐A71‐specific cellular response may also contribute to pulmonary edema 13, 106. Interestingly, neurogenic pulmonary edema in bulbar poliomyelitis was reported to best correlate with damage to the dorsal nuclei of the vagus and medial reticular nuclei (vasomotor) 4. We speculate that other contributory factors to sudden collapse may be damage to medullary respiratory control center and respiratory muscle paralysis following severe cord motor neuron injury. Unlike humans, pulmonary edema has not been reported in animal models including rodents and non‐human primates 28, 55, 75, 76, 80, 111.

So far, there is no evidence that mutations in the viral genome of EV‐A71 confer neurovirulence, unlike poliovirus in which mutations in the 5′ UTR can determine virulence 45. So far, analysis of whole EV‐A71genomic sequences derived from fatal and non‐fatal cases has not revealed any mutations responsible for neurovirulence. Nevertheless, several studies have demonstrated that mutations in structural and non‐structural genes may confer or attenuate neurovirulence in mice and monkey models 2, 3. There is still every possibility that neurovirulent viral strains could arise from specific viral mutations in future outbreaks of HFMD as recombinant events are very common among EV‐A71 strains 49, 58, 69. Other viral factors like the infective viral dose, host factors like immune status caused by diminishing protective maternal antibodies 62, 131 or immunosuppression 1, 41, genetic predisposition [2′‐5′‐oligoadenylate synthetase1, HLA A33, chemokine (c‐c motif) ligand 2] 8, 15, 32, and gender may be important and should be investigated further.

Treatment and Vaccines

There are currently no approved antiviral drugs for treatment of EV‐A71 infections but numerous candidates have been tested including type 1 interferons, ribavirin, suramin, pleconaril, inhibitors of EV‐A71 non‐structural proteins (eg, 3D polymerase) and cellular receptor inhibitors. Detailed results from these studies have been recently reviewed 95. Suramin, which binds to the viral capsid, prevents viral attachment to cells 92, 110. As it has demonstrated exceptional post‐exposure and therapeutic efficacy in mouse and rhesus monkey models, it appears to be a promising drug 92. Type 1 interferon and ribavirin have also shown efficacy in mouse models 52, 56. Milrinone, a cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase inhibitor which is used as a treatment for congestive cardiac failure may reduce mortality in patients 105, 107.

Normal, polyclonal or hyperimmune (anti‐EV‐A71) intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) has been used as a therapeutic modality for EV‐A71 infection. Some studies reported improvements in severe EV‐A71 infection after IVIG administration 12, 84. Chemokine and cytokine levels before and after treatment apparently showed reduction 108. In Taiwan, IVIG is now routinely used for the treatment of CNS complications 12, 105. In addition to IVIG, passive immunization using specific anti‐EV‐A71 monoclonal antibodies (human or humanized) is being actively developed as better therapies based on results in animal experiments 11, 24, 43, 51. Interestingly, passive immunization was found to be useful to ameliorate experimental brainstem encephalitis 103.

The success of both the formalin‐inactivated and live attenuated vaccines in controlling poliovirus epidemics underscores the potential use of mass vaccination as an effective means to control EV‐A71 epidemics. Numerous studies have demonstrated that inactivated EV‐A71 virus vaccine can protect against lethal EV‐A71 infection in mouse models, either by transplacental transfer of maternal antibodies, passive immunization using antibodies from immunized mice or active immunization 81, 116, 124. A concerted effort to develop vaccines suitable for human populations reached a milestone when inactivated vaccines were tested in three independent phase 3 clinical trials involving more than 10 000 children each 50, 130, 132. All three vaccines could elicit protective immune responses over the course of two epidemic seasons with vaccine efficacies of > 90%, and only mild adverse effects, such as fever. Unfortunately, these vaccines did not protect against CV‐A16 infection 50, 130, 132. Other vaccine formats, including DNA vaccines, viral‐like particles, synthetic peptides, and recombinant VP1 proteins derived from milk of transgenic mice expressing VP1have been developed and found to be immunogenic 20, 23, 27, 104.

Poliovirus, Coxsackievirus A16, Enterovirus D68 and Other Neurotropic Enteroviruses

The best known neurotropic enterovirus is undoubtedly poliovirus, which was discovered more than a century ago 91. The spectrum of neurological diseases caused by poliovirus includes, aseptic meningitis, paralytic poliomyelitis (spinal poliomyelitis, bulbar poliomyelitis and bulbospinal poliomyelitis), and the rare encephalitis 86. These clinical syndromes generally resemble those of EV‐A71, although poliovirus uses a different virus receptor, CD155 70. Poliovirus neuronotropism in the CNS has been convincingly demonstrated in mouse and monkey models by immunohistochemistry and by ultrastructural studies 33, 74, 76, and viral RNA has been localized in the human spinal cord motor neurons 26. As far as stereotypic distribution of inflammation is concerned, perhaps the closest to EV‐A71 encephalomyelitis is bulbospinal poliomyelitis 6. EV‐A71 associated AFP also appears similar to spinal poliomyelitis as evidenced by clinical and MRI features 17, 37. It is widely believed that poliovirus utilizes both hematogenous as well as retrograde axonal transport based on evidence extensively reviewed elsewhere 86, 91. The transgenic mouse model that expresses the human CD155 poliovirus receptor has provided additional support for fast retrograde axonal transport in motor nerves 46, 78, 93 similar to findings in the EV‐A71 mouse model 16, 80, 103. Furthermore, it is postulated that the poliovirus could enter peripheral nerve via the motoneuron junction after viral endocytosis and endosomal movement along microtubules to reach and infect cord motor neurons 45, 73, 79. The probable use of the motoneuron junction by EV‐A71 for entry into peripheral nerves remains to be investigated, although skeletal muscle infection in the mouse model is consistent with this notion. There is evidence that in poliovirus and EV‐A71 infections, the palatine tonsil may play an important role as a site for viral replication and as a portal for viral entry. Poliovirus has been cultured from tonsils and thought to be a portal for viral entry in experimentally infected chimpanzees 5. EV‐A71 has been isolated from human tonsils 22 and viral antigens/RNA localized to tonsillar crypt squamous epithelium 34.

Although similar in many ways to EV‐A71, neurological complications in CV‐A16 infection are probably very rare 30. Most of the evidence of CV‐A16 neurovirulence in anecdotal reports has been indirect because virus was not isolated from CSF or CNS tissues, but from extra CNS sites, such as throat or rectum. In large epidemics of HFMD where neurological complications are more likely to occur, it is not uncommon to have EV‐A71, CV‐A16 and other enteroviruses circulating together, thus confirmation of the causative neurotropic virus is difficult, unless virus was isolated from clinically relevant sites. With the advent of MRI and molecular diagnosis, perhaps better evidence for CV‐A16 neurotropism will be forth coming in future. Nonetheless, in at least one CV‐A16 associated rhombencephalitis (virus cultured from rectal swab), brain MRI showed hyperintense lesions that were strikingly similar to EV‐A71 30. We believe that CV‐A16 neurotropism has not been unequivocally demonstrated in human infected tissues or animal models 7, 57, 66.

EV‐D68 as a species group D serotype is unique among enteroviruses in that it has properties of both enteroviruses and rhinoviruses, which are predominant causes of the common cold 42. Until recently, EV‐D68 usually causes a rare self‐limited respiratory illness. From 2008, localized outbreaks were reported, culminating in more widespread outbreaks of >1000 cases of severe lower respiratory disease in 2014. Reports of AFP (later called acute flaccid myelitis) associated with EV‐D68 surfaced from 2005 onwards in the USA, France and Norway. Not surprisingly, most virus isolations from these outbreaks were obtained from patients' respiratory secretions; only rarely from blood and cerebrospinal fluid 31, 71, 87. The reasons for the emergence of neurotropic strains of EV‐D68 are still unknown. So far, no viral genomic variations have been linked to neurovirulence 31, 117. In Denmark, recent isolates had >98% genome homology with viruses associated with AFP but no AFP was reported 72. MRI showed hyperintensive, non‐enhancing lesions in bilateral anterior horns and/or central gray areas, and ventral roots, over extensive areas of the spinal cord, most prominently in the cervical cord. In the brainstem, lesions were found in the pontine tegmentum, medulla, midbrain, anterior pons and dentate nucleus 65, 71. No supratentorial lesions were found. By and large, the distribution of these lesions corresponded very well with MRI and autopsy findings in EV‐A71 encephalomyelitis 19, 114, 115, 126. The only post‐mortem case diagnosed as EV‐D68 infection by RT‐PCR and sequencing, showed extensive meningoencephalitis characterized by inflammation in the cerebellum, midbrain, pons, medulla and cervical cord, with prominent neuronophagia of motor nuclei 47. Unfortunately, further details of topographic distribution of inflammation or detection of viral antigens/RNA were not available. Based on available data, we speculate that like EV‐A71, EV‐D68 may be able to enter the CNS via retrograde viral transmission up peripheral and cranial motor nerves to infect motor neurons in the cord and brainstem, respectively. Moreover, it is likely that EV‐D68 is neuronotropic, with a predilection for motor neurons.

Many more enterovirus serotypes from various species groups have been associated with neurological syndromes 42. However, good evidence for some of these associations may be lacking because viral isolation from a clinically relevant site is often unavailable because of poor collection/storage techniques, obtaining specimens outside the optimal virus replication/shedding period and lack of proper lab facilities. Even in the recent EV‐D68 outbreaks, although epidemiological, clinical and other data suggested this, it remains unproven that EV‐D68 is the causative virus of the neurological complications. Further studies are needed to resolve these issues. In anecdotal reports, eg, echovirus 7 (B species group) encephalitis, a positive viral culture from the CSF, and good supporting MRI data, even in the absence of post‐mortem findings, is probably good enough evidence that echovirus 7 is neurotropic. Interestingly, the MRI findings in echovirus 7 encephalitis were similar to EVA‐71 encephalomyelitis 60. Thus, overall, neurotropic enteroviruses may share common neuropathogenesis and pathways to invade the CNS.

Conclusion

With the imminent eradication of poliovirus as the most prevalent neurotropic enterovirus the world has known, other non‐polio, neurotropic enteroviruses, notably EV‐A71, could replace it as a cause of widespread morbidity and mortality 68, 100. Much work remains to be done to more fully understand the neuropathogenesis of these viruses. Wider availability of newer molecular techniques, CNS diagnostic imaging and greater awareness of neurotropic potential of enteroviruses could help with the diagnosis and identification of future outbreaks of emerging or re‐emerging complicated enteroviral infections.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part, by the University of Malaya/Ministry of Education High Impact Research Grant (H‐20001‐00‐E000004) and University of Malaya Research Grant (RG141/09HTM).

References

- 1. Ahmed R, Buckland M, Davies L, Halmagyi GM, Rogers SL, Oberst S, Barnett MH (2011) Enterovirus 71 meningoencephalitis complicating rituximab therapy. J Neurol Sci 305:149–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arita M, Nagata N, Iwata N, Ami Y, Suzaki Y, Mizuta K et al (2007) An attenuated strain of enterovirus 71 belonging to genotype A showed a broad spectrum of antigenicity with attenuated neurovirulence in cynomolgus monkey. J Virol 81:9386–9395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arita M, Ami Y, Wakita T, Shimizu H (2008) Cooperative effect of the attenuation determinants derived from poliovirus sabin 1 strain is essential for attenuation of enterovirus 71 in the NOD/SCID mouse infection model. J Virol 82:1787–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baker AB (1957) Poliomyelitis: a study of pulmonary edema. Neurology 7:743–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bodian D (1955) Emerging concept of poliomyelitis infection. Science 12:105–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bodian D (1968) Poliomyelitis. In: Pathology of the Nervous System. Minckler J (ed.), pp. 2323–2344. McGraw‐Hill: New York. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cai Y, Liu Q, Huang X, Li D, Ku Z, Zhang Y, Huang Z (2013) Active immunization with Coxsackievirus A16 experimental inactivated vaccine induces neutralizing antibodies and protects mice against lethal infection. Vaccine 26:2215–2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cai Y, Chen Q, Zhou W, Chu C, Ji W, Ding Y et al (2014) Association analysis of polymorphisms in OAS1 with susceptibility and severity of hand, foot and mouth disease. Int J Immunogenet 41:384–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chan KP, Goh KT, Chong CY, Teo ES, Lau G, Ling AE (2003) Epidemic hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by human enterovirus 71, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis 9:78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chan LG, Parashar UD, Lye MS, Ong FGL, Zaki SR, Alexander JP et al (2000) Deaths of children during an outbreak of hand, foot, and mouth disease in Sarawak, Malaysia: clinical and pathological characteristic of the disease. Clin Infect Dis 31:678–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chang HW, Lin YW, Ho HM, Lin MH, Liu CC, Shao HY et al (2013) Protective efficacy of VP1‐specific neutralizing antibody associated with a reduction of viral load and pro‐inflammatory cytokines in human SCARB2‐transgenic mice. PLoS ONE 30:e69858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chang LY, Hsia SH, Wu CT, Huang YC, Lin KL, Fang TY, Lin TY (2004) Outcome of enterovirus 71 infections with or without stage‐based management: 1998–2002. Pediatr Infect Dis J 23:327–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang LY, Hsiung CA, Lu CY, Lin TY, Huang FY, Lai YH et al (2006) Status of cellular rather than humoral immunity in correlated with clinical outcome of enterovirus 71. Pediatr Res 60:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chang LY, Huang LM, Gau LM, Susan SF, Wu YY, Hsia SH et al (2007) Neurodevelopment and cognition in children after enterovirus 71 infection. N Engl J Med 356:1226–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chang LY, Chang IS, Chen WJ, Huang YC, Chen GW, Shih SR et al (2008) HLA‐A33 is associated with susceptibility to enterovirus 71 infection. Pediatrics 122:1271–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen CS, Yao YC, Lin SC, Lee YP, Wang YF, Wang JR et al (2007) Retrograde axonal transport: a major transmission route of enterovirus 71 in mice. J Virol 81:8996–9003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen CY, Chang YC, Huang CC, Lui CC, Lee KW, Huang SC (2001) Acute flaccid paralysis in infants and young children with enterovirus 71 infection: MR imaging finding and clinical correlates. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 22:200–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen F, Li JJ, Liu T, Wen GQ, Xiang W (2013) Clinical and neuroimaging features of enterovirus 71 related acute flaccid paralysis in patients with hand‐foot‐mouth disease. Asian Pac J Trop Med 6:68–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen F, Liu T, Li J, Xing Z, Huang S, Wen G (2014) MRI characteristics and follow‐up findings in patients with neurological complications of enterovirus 71‐related hand, foot, and mouth disease. Int J Clin Exp Med 7:2696–2704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen HL, Huang JY, Chu TW, Tsai TC, Hung CM, Lin CC et al (2008) Expression of VP1 protein in the milk of transgenic mice: a potential oral vaccine protects against enterovirus 71 infection. Vaccine 26:2882–2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cheng H, Zeng J, Li H, Li Y, Wang W (2015) Neuroimaging of HFMD infected by EV71. Radiol Infect Dis 1:103–108. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chong CY, Chan KP, Shah VA, Ng WYM, Lau G, Teo TS et al (2003) Hand, foot and mouth disease in Singapore: a comparison of fatal and non‐fatal cases. Acta Paediatr 92:1163–1169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chung YC, Ho MS, Wu JC, Chen WJ, Huang JH, Chou ST, Hu YC (2008) Immunization with virus‐like particles of enterovirus 71 elicits protect immune responses and protects mice against lethal challenge. Vaccine 26:1855–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Deng YQ, Ma J, Xu LJ, Li YX, Zhao H, Han JF et al (2015) Generation and characterization of a protective mouse monoclonal antibody against human enterovirus 71. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol DOI: 10.1007/s00253-015-6652-8 (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Du X, Wang H, Xu F, Huang Y, Liu Z, Liu T (2015) Enterovirus 71 induces apoptosis of SH‐SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells through stimulation of endogenous microRNA let‐7b expression. Mol Med Rep 12:953–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Esiri MM (1997) Viruses and rickettsiae. Brain Pathol 7:695–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Foo DGW, Alonso S, Chow VTK, Poh CL (2007) Passive protection against lethal enterovirus 71 infection in newborn mice by neutralizing antibodies elicited by a synthetic peptide. Microbes Infect 9:1299–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fujii K, Nagata N, Sato Y, Ong KC, Wong KT, Yamayoshi S et al (2013) Transgenic mouse model for the study of enterovirus 71 neuropathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:14753–14758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fujimoto T, Yoshida S, Munemura T, Taniguchi K, Shinohara M, Nishio O et al (2008) Detection and quantification of enterovirus 71 genome from cerebrospinal fluid of an encephalitis patient by PCR application. Jpn J Infect Dis 61:497–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goto K, Sanefuji M, Kusuhara K, Nishimura Y, Shimizu H, Kira R et al (2009) Rhombencephalitis and coxsackievirus A16. Emerg Infect Dis 15:1686–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Greninger AL, Naccache SN, Messacar K, Clayton A, Yu G, Somasekar S et al (2015) A novel outbreak enterovirus D68 strain associated with acute flaccid myelitis cases in the USA [1](2012‐14): a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 15:671–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Han ZL, Li JA, Chen ZB (2014) Genetic polymorphism of CCL2‐2510 and susceptibility to enterovirus 71 encephalitis in a Chinese population. Arch Virol 159:2503–2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hashimoto I, Hagiwara A, Komatsu T (1984) Ultrastructural studies on the pathogenesis of poliomyelitis in monkeys infected with poliovirus. Acta Neuropathol 64:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. He Y, Ong KC, Gao Z, Zhao X, Anderson VM, McNutt MA et al (2014) Tonsillar crypt epithelium is an important extra‐nervous system site for viral replication in EV71 encephalomyelitis. Am J Pathol 184:714–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ho M, Chen ER, Hsu KH, Twu SJ, Chen KT, Tsai SF et al (1999) An epidemic of enterovirus 71 infection in Taiwan. N Engl J Med 341:929–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hsueh C, Jung SM, Shih SR, Kuo TT, Shieh WJ, Zaki SR et al (2000) Acute encephalomyelitis during an outbreak of enterovirus type 71 infection: report of an autopsy case with pathologic, immunofluorescence, and molecular studies. Mod Pathol 13:1200–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huang CC, Liu CC, Chang YC, Chen CY, Wang ST, Yeh TF (1999) Neurologic complication in children with enterovirus 71 infection. N Engl J Med 341:929–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huang MC, Wang SM, Hsu YW, Lin HC, Chi CY, Liu CC (2006) Long‐term cognitive and motor deficits after enterovirus 71 brainstem encephalitis in children. Pediatrics 118:1785–1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Huang PN, Shih SR (2014) Update on enterovirus 71 infection. Curr Opin Virol 5:98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Huang SC, Chang CL, Wang PS, Tsai Y, Liu HS (2009) Enterovirus 71‐induced autophagy detected in vitro and in vivo promotes viral replication. J Med Virol 81:1241–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kassab S, Saghi T, Boyer A, Lafon ME, Gruson D, Lina B et al (2013) Fatal case of enterovirus 71 infection and rituximab therapy, France, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis 19:1345–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Khetsuriani N, Lamonte‐Fowlkes A, Oberst S, Pallansch MA, Prevention CfDCa (2006) Enterovirus surveillance‐United States, 1970–2005. MMWR Surveill Summ 55:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kiener TK, Jia Q, Meng T, Chow VTK, Kwang J (2014) A novel universal neutralizing monoclonal antibody against Enterovirus 71 that targets the highly conserved “knob” region of VP3 protein. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8:e2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. King AMQ, Adams MJ, Carstens EB, Lefkowitz EJ (2012) Virus Taxonomy: Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses: Ninth REPORT of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press: San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Koike S, Nomoto A (2010) Poliomyelitis. In: The Picornaviruses. Ehrenfeld E, Domingo E, Roos RP (eds), pp. 339–351. ASM Press: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Koike S, Taya C, Kurata T, Abe S, Ise I, Yonekawa H, Nomoto A (1991) Transgenic mice susceptible to poliovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88:951–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kreuter JD, Barnes A, McCarthy JE, Schwartzman JD, Oberste MS, Rhodes CH et al (2011) A fatal central nervous system enterovirus 68 infection. Arch Pathol Lab Med 135:793–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lee YR, Wang PS, Wang JR, Liu HS (2014) Enterovirus 71‐induced autophagy increases viral replication and pathogenesis in a suckling mouse model. J Biomed Sci 21:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li J, Huo X, Dai Y, Yang Z, Lei Y, Jiang Y et al (2012) Evidence for intertypic and intratypic recombinant events in EV71 of hand, foot and mouth disease during an epidemic in Hubei Province, China, 2011. Virus Res 169:195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li R, Liu L, Mo Z, Wang X, Xia J, Liang Z et al (2014) An inactivated enterovirus 71 vaccine in healthy children. N Engl J Med 370:829–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Li Z, Xu L, He D, Yang L, Liu C, Chen Y et al (2014) In vivo time‐related evaluation of a therapeutic neutralization monoclonal antibody against lethal enterovirus 71 infection in a mouse model. PLoS ONE 9:e109391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Li ZH, Li CM, Ling P, Shen FH, Chen SH, Liu CC et al (2008) Ribavirin reduces mortality in enterovirus 71‐infected mice by decreasing viral replication. J Infect Dis 197:854–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Liang CC, Sun MJ, Lei HY, Chen SH, Yu CK, Liu CC et al (2004) Human endothelial cell activation and apoptosis induced by enterovirus 71 infection. J Med Virol 74:597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lin YW, Wang SW, Tung YY, Chen SH (2009) Enterovirus 71 infection of human dendritic cells. Exp Biol Med 234:1166–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lin YW, Yu SL, Shao HY, Lin HY, Liu CC, Hsiao KN et al (2013) Human SCARB2 transgenic mice as an infectious animal model for enterovirus 71. PLoS ONE 8:e57591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Liu ML, Lee YP, Wang YF, Lei HY, Liu CC, Wang SM et al (2005) Type 1 interferons protect mice against enterovirus 71 infection. J Gen Virol 86:3263–3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Liu Q, Shi J, Huang X, Liu F, Cai Y, Lan K, Huang Z (2014) A murine model of coxsackievirus A16 infection for anti‐viral evaluation. Antiviral Res 105:26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Liu W, Wu S, Xiong Y, Li T, Wen Z, Yan M et al (2014) Co‐circulation and genomic recombination of coxsackievirus A16 and enterovirus 71 during a large outbreak of hand, foot, and mouth disease in Central China. PLoS ONE 9:e96051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lui YL, Tan EL (2014) Droplet digital PCR as a useful tool for the quantitative detection of Enterovirus 71. J Virol Methods 2007:200–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lum LC, Chua KB, McMinn PC, Goh AY, Muridan R, Sarji SA et al (2002) Echovirus 7 associated encephalomyelitis. J Clin Virol 23:153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lum LCS, Wong KT, Lam SK, Chua KB, Goh AYT, Lim WL et al (1998) Fatal enterovirus 71 encephalomyelitis. J Pediatr 133:795–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Luo ST, Chiang PS, Chao AS, Liou GY, Lin R, Lin TY, Lee MS (2009) Enterovirus 71 maternal antibodies in infants, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis 15:581–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Luo W, Zhong J, Zhao W, Liu J, Zhang R, Peng L et al (2015) Proteomic analysis of human brain microvasular endothelial cells reveals differential protein expression in response to enterovirus 71 infection. Biomed Res Int 2015:864169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ma E, Fung C, Yip SH, Wong C, Chuang SK, Tsang T (2011) Estimation of the basic reproduction number of enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A16 in hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreaks. Pediatr Infect Dis J 30:675–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Maloney JA, Mirsky DM, Messacar K, Dominguez SR, Schreiner T, Stence NV (2015) MRI findings in children with acute flaccid paralysis and cranial nerve dysfunction occurring during the 2014 enterovirus D68 outbreak. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 36:245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mao Q, Wang Y, Gao R, Shao J, Yao X, Lang S et al (2012) A neonatal mouse model of coxsackievirus A16 for vaccine evaluation. J Virol 86:11967–11976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. McMinn P (2002) An overview of the evolution of enterovirus 71 and its clinical and public health significance. FEMS Microbiol Rev 26:91–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. McMinn PC (2012) Recent advances in the molecular epidemiology and control of human enterovirus 71 infection. Curr Opin Virol 2:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. McWilliam Leith EC, Cabrerizo M, Cardosa J, Harvala H, Ivanova OE, Koike S et al (2012) The association of recombination events in the founding and emergence of subgenogroup evolutionary lineages of human enterovirus 71. J Virol 86:2676–2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Mendelsohn CL, Wimmer E, Racaniello VR (1989) Cellular receptor for poliovirus: molecular cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of a new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Cell 56:855–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Messacar K, Schreiner TL, Maloney JA, Wallace A, Ludke J, Oberste MS et al (2015) A cluster of acute flaccid paralysis and cranial nerve dysfunction temporally associated with an outbreak of enterovirus D68 in children in Colorado, USA. Lancet 385:1662–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Midgley SE, Christiansen CB, Poulsen MW, Hansen CH, Fischer TK (2015) Emergence of enterovirus D68 in Denmark, June 2014 to February 2015. Euro Surveill 20:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mueller S, Wimmer E, Cello J (2005) Poliovirus and poliomyelitis: a tale of guts, brain, and an accidental event. Virus Res 111:175–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Nagata N, Iwasaki T, Ami Y, Harashima A, Hatano I, Suzaki Y et al (2001) Comparison of neuropathogenicity of poliovirus type 3 in transgenic mice bearing the poliovirus receptor gene and cynomolgus monkeys. Vaccine 19:3201–3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Nagata N, Shimizu H, Ami Y, Tano Y, Harashima A, Suzaki Y et al (2002) Pyramidal and extrapyramidal involvement in experimental infection of cynomolgus monkeys with enterovirus 71. J Med Virol 67:207–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Nagata N, Iwasaki T, Ami Y, Tano Y, Harashima A, Suzaki Y et al (2004) Differential localization of neurons susceptible to enterovirus 71 and poliovirus type 1 in the central nervous system of cynomolgus monkeys after intravenous inoculation. J Gen Virol 85:2981–2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Nishimura Y, Shimojima M, Tano Y, Miyamura T, Wakita T, Shimizu H (2009) Human P‐selectin glycoprotein ligand‐1 is a functional receptor for enterovirus 71. Nat Med 15:794–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ohka S, Yang WX, Terada E, Iwasaki K, Nomoto A (1998) Retrograde transport of intact poliovirus through the axon via the fast transport system. Virology 250:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ohka S, Nihei C, Yamazaki M, Nomoto A (2012) Poliovirus trafficking toward central nervous system via human poliovirus receptor‐dependent and independent pathway. Front Microbiol 3:147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ong KC, Munisamy B, Leong KL, Devi S, Cardosa MJ, Wong KT (2008) Pathologic characterization of a murine model of human enterovirus 71 encephalomyelitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 67:532–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ong KC, Devi S, Cardosa J, Wong KT (2010) Formaldehyde inactivated whole‐virus vaccine protects a murine model of enterovirus 71 encephalomyelitis against disease. J Virol 84:661–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Ooi MH, Solomon T, Podin Y, Mohan A, Akin W, Yusuf MA et al (2007) Evaluation of different clinical sample types in diagnosis of human enterovirus 71‐associated hand‐foot‐and‐mouth disease. J Clin Microbiol 45:1858–1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ooi MH, Wong SC, Podin Y, Akin W, del Sel S, Mohan A et al (2007) Human enterovirus 71 disease in Sarawak, Malaysia: a prospective clinical, virological, and molecular epidemiological study. Clin Infect Dis 44:646–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Ooi MH, Wong SC, Mohan A, Podin Y, Perera D, Clear D et al (2009) Identification and validation of clinical predictors for the risk of neurological involvement in children with hand, foot, and mouth disease in Sarawak. BMC Infect Dis 9:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Ooi MH, Wong SC, Lewthwaite P, Cardosa MJ, Solomon T (2010) Clinical features, diagnosis, and management of enterovirus 71. Lancet Neurol 9:1097–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Pallansch MA, Roos RP (2001) Enteroviruses: poliovirus, coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, and newer enteroviruses. In: Field Virology. Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Martin MA, Lamb RA, Roizman B (eds), pp. 723–775. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Pastula DM, Aliabadi N, Haynes AK, Messacar K, Schreiner T, Maloney J et al (2014) Acute neurologic illness of unknown etiology in children‐Colorado, August–September 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 63:901–902. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Pleva P, Perera R, Cardosa J, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG (2012) Crystal structure of human enterovirus 71. Science 336:1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Pleva P, Perera R, Cardosa J, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG (2012) Structure determination of enterovirus 71. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 68:1217–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Racaniello VR (2001) Picornaviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Field Virology. Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Martin MA, Lamb RA, Roizman B (eds), pp. 685–722. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- 91. Racaniello VR (2006) One hundred years of polivirus pathogenesis. Virology 344:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ren P, Zou G, Bailly B, Xu S, Zeng M, Chen X et al (2014) The approved pediatric drug suramin identified as a clinical candidate for the treatment of EV71 infection—suramin inhibits EV71 infection in vitro and in vivo . Emerg Microbes Infect 3:e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Ren R, Racaniello VR (1992) Poliovirus spreads from muscle to central nervous system by neural pathway. J Infect Dis 166:747–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Schmidt NJ, Lennette EH, Ho HH (1974) An apparently new enterovirus isolated from patients with disease of the central nervous system. J Infect Dis 129:304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Shang L, Xu M, Yin Z (2013) Antiviral drug discovery for the treatment of enterovirus 71 infections. Antiviral Res 97:183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Shen WC, Chiu HH, Chow KC, Tsai CH (1999) MR imaging findings of enteroviral encephalomyelitis: an outbreak in Taiwan. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 20:1889–1895. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Shi W, Li K, Ji Y, Jiang Q, Shi M, Mi Z (2011) Development and evaluation of reverse transcription‐loop mediated isothermal amplication assay for rapid detection of enterovirus 71. BMC Infect Dis 11:197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Shieh WJ, Jung SM, Hsueh C, Kuo TT, Mounts A, Parashar U et al (2001) Pathological studies of fatal cases in outbreak of hand, foot, and mouth disease, Taiwan. Emerg Infect Dis 7:146–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Shih SR, Weng KF, Stollar V, Li ML (2008) Viral protein synthesis is required for Enterovirus 71 to induce apoptosis in human glioblastoma cells. J Neurovirol 14:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Solomon T, Lewthwaite P, Perera D, Cardosa MJ, McMinn P, Ooi MH (2010) Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of enterovirus 71. Lancet Infect Dis 10:778–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Su PY, Wang YF, Huang SW, Lo YC, Wang YH, Wu SR et al (2015) Cell surface nucleolin facilitates enterovirus 71 binding and infection. J Virol 89:4527–4538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Tan CW, Poh CL, Sam IC, Chan YF (2013) Enterovirus 71 uses cell surface heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan as an attachment receptor. J Virol 87:611–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Tan SH, Ong KC, Wong KT (2014) Enterovirus 71 can directly infect the brainstem via cranial nerves and infection can be ameliorated by passive immunization. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 73:999–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Tung SW, Bakar SA, Sekawi Z, Rosli R (2007) DNA vaccine construct against enterovirus 71 elicit immune response in mice. Genet Vaccines Ther 5:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Wang JN, Yao CT, Yeh CN, Huang CC, Wang SM, Liu CC, Wu JM (2006) Critical management in patients with severe enterovirus 71 infection. Pediatr Int 48:250–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Wang SM, Lei HY, Huang KJ, Wu JM, Wang JR, Yu CK et al (2003) Pathogenesis of enterovirus 71 brainstem encephalitis in pediatric patients: role of cytokines and cellular immune activation in patients with pulmonary edema. J Infect Dis 188:564–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Wang SM, Lei HY, Huang MC, Wu JM, Chen CT, Wang JN et al (2005) Therapeutic efficacy of milrinone in the management of enterovirus 71‐induced pulmonary edema. Pediatr Pulmonol 39:219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Wang SM, Lei HY, Huang MC, Siu LY, Lin HC, Yu CK et al (2006) Modulation of cytokine production by intravenous immunoglobulin in patients with enterovirus 71 associated brainstem encephalitis. J Clin Virol 37:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Wang SM, Lei HY, Liu CC (2012) Cytokine immunopathogenesis of enterovirus 71 brain stem encephalitis. Clin Dev Immunol 2012:876241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Wang Y, Qing J, Sun Y, Rao Z (2014) Suramin inhibits EV71 infection. Antiviral Res 103:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Wang YF, Chou CT, Lei HY, Liu CC, Wang SM, Yan JJ et al (2004) A mouse‐adapted enterovirus 71 strain causes neurological disease in mice after oral infection. J Virol 78:7916–7924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. WHO (2011) A Guide to Clinical Management and Public Heath Response for Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease (HFMD). Word Heath Organization: Manila, Philippines. [Google Scholar]

- 113. Wong KT, Chua KB, Lam SK (1999) Immunohistochemical detection of infected neurons as a rapid diagnosis of enterovirus 71 encephalomyelitis. Ann Neurol 45:271–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Wong KT, Badmanathan M, Ong KC, Kojima H, Nagata N, Chua KB et al (2008) The distribution of inflammation and virus in human enterovirus 71 encephalomyelitis suggests possible viral spread by neural pathways. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 67:162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Wong KT, Ng KY, Ong KC, Ng WF, Shankar SK, Mahadevan A et al (2012) Enterovirus 71 encephalomyelitis and Japanese encephalitis can be distinguished by topographic distribution of inflammation and specific intraneuronal detection of viral antigen and RNA. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 38:443–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Wu CN, Lin YC, Fann C, Liao NS, Shih SR, Ho MS (2002) Protection against lethal enterovirus 71 infection in newborn mice by passive immunization with subunit VP1 vaccines and inactivated virus. Vaccine 20:895–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Wylie KM, Wylie TN, Orvedahl A, Buller RS, Herter BN, Magrini V et al (2015) Genome sequence of enterovirus D68 from St. Louis, Missouri, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 21:184–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Xi X, Zhang X, Wang B, Wang T, Wang J, Huang H et al (2013) The interplays between autophagy and apoptosis induced by enterovirus 71. PLoS ONE 8:e56966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 119. Yamayoshi S, Yamashita Y, Li J, Hanagata N, Minowa T, Takemura T, Koike S (2009) Scavenger receptor B2 is a cellular receptor for enterovirus 71. Nat Med 15:798–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Yan JJ, Wang JR, Liu CC, Yang BF, Su IJ (2000) An outbreak of enterovirus 71 infection in Taiwan 1998: a comprehensive pathological, virological and molecular study on a case of fulminant encephalitis. J Clin Virol 17:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Yang B, Chuang H, Yang KD (2009) Sialylated glycans as receptor and inhibitor of enterovirus 71 infection to DLD‐1 intestinal cells. Virol J 6:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Yang SL, Chou YT, Wu CN, Ho MS (2011) Annexin II blinds to capsid protein VP1 of enterovirus 71 and enhances viral infectivity. J Virol 85:11809–11820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Yang Y, Wang H, Gong E, Du J, Zhao X, McNutt MA et al (2009) Neuropathology in 2 cases of fatal enterovirus type 71 infection from a recent epidemic in the People's Republic of China: a histopathologic, immunohistochemical, and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction study. Hum Pathol 40:1288–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Yu CK, Chen CC, Chen CL, Wang JR, Liu CC, Yang JJ, Su IJ (2000) Neutralizing antibody provided protection against enterovirus type 71 lethal challenge in neonatal mice. J Biomed Sci 7:523–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Yu P, Gao Z, Zong Y, Bao L, Xu L, Deng W et al (2014) Histopathological features and distribution of EV71 antigens and SCARB2 in human fatal cases and a mouse model for enterovirus 71 infection. Virus Res 189:121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Zeng H, Wen F, Gan Y, Huang W (2012) MRI and associated clinical characteristics of EV71‐induced brainstem encephalitis in children with hand‐foot‐mouth disease. Neuroradiology 54:623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Zhang S, Wang J, Yan Q, He S, Zhou W, Ge S, Xia N (2014) A one‐step, triplex real‐time RT‐PCR assay for the simultaneous detection of enterovirus 71, coxsackievirus A16 and pan‐enterovirus in a single tube. PLoS ONE 16:e102724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Zhang Y, Cui W, Liu L, Wang J, Zhao H, Liao Y et al (2011) Pathogenesis study of enterovirus 71 infection in rhesus monkeys. Lab Invest 91:1337–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Zhang YC, Jiang SW, Gu WZ, Hu AR, Lu CT, Liang XY et al (2012) Clinicopathologic features and molecular analysis of enterovirus 71 infection: report of an autopsy case from the epidemic of hand, foot and mouth disease in China. Pathol Int 62:565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Zhu F, Xu W, Xia J, Liang Z, Liu Y, Zhang X et al (2014) Efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of an enterovirus 71 vaccine in China. N Engl J Med 370:818–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Zhu FC, Liang ZL, Meng FY, Zeng Y, Mao QY, Chu K et al (2012) Retrospective study of the incidence of HFMD and seroepidemiology of antibodies against EV71 and Cox A16 in prenatal women and their infants. PLoS ONE 7:e37206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Zhu FC, Meng FY, Li JX, Li XL, Mao QT, Tao H et al (2013) Efficacy, safety, and immunology of an inactivated alum‐adjuvant enterovirus 71 vaccine in children in China: a multicentre, randomised, double ‐bind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 381:2024–2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]