Abstract

Understanding the events that are responsible for a disease is mandatory for setting up a therapeutic strategy. Although spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is considered a rare neurodegenerative pathology, its impact in our society is really devastating as it strikes young people from birth onward, and it affects their families either emotionally or financially. Moreover, it requires intensive care for the children, and this diverts both parents and relatives from their occupations. Each neuron is very different from one another; therefore, in a neurodegenerative disease, the population of axons, synapses and cell bodies degenerate asynchronously, and subpopulations of neurons have different vulnerabilities. The knowledge of the sequence of events along the lengths of individual neurons is crucial to understand if each synapse degenerates before the corresponding axon, or if each axon degenerates before the corresponding cell body. Early degeneration of one neuronal compartment in disease often reflects molecular defects somewhere else. Up until now, SMA is considered mostly a lower motor neuron disease caused by the loss‐of‐function mutations in the SMN1 gene; here, we inspect other features that can be altered by this defect, such as the cross talk between muscle and motor neuron and the role of physical inactivity.

Keywords: cardiotrophin 1, miRNA, muscle activity, NMJ, SMN1, SMN2, spinal muscular atrophy

Introduction

Guido Werdnig in 1891 and Johann Hoffmann, between 1893 and 1900, described a total of nine cases of a disease where young people were affected by a new form of muscular atrophy (spinal muscular atrophy or SMA).

The carrier frequency of the disease is of 1 in 54, and its incidence is 1 in 11 000 as it was shown in a pan‐ethnic study. Furthermore, it was determined that in the Unites States, there are substantial differences between different ethnic groups 86.

SMA is typically classified into four phenotypes (1–4) on the basis of age of onset and the highest motor function achieved. While this classification has several clinical advantages, it could result inadequate to provide prognostic information, or to aid stratification of patients in clinical trials 57. An additional phenotype (type 0), a severe form of prenatal onset, was recently described; this is the most severe type and death threatening, and it can be diagnosed during the gestation. If not adequately supported after birth, the infants affected by this severe form of SMA do not survive beyond the first months of life 75. Type 1 or the Werdnig‐Hoffmann disease is also very severe. Patients cannot sit, and their life expectancy usually does not exceed 2 years; moreover, some of them have the inability to control the position of their head. Type 2 SMA is an intermediate form, its onset is between 7 and 18 months, and the patients can sit but never stand. Type 2 SMA patients can survive to adulthood. Type 3 SMA (Kugelberg and Welander) has the onset after the 30th month of life, the severity of the disease is classified depending on the weakness of the proximal muscles (before or after 3 years); moreover, the patient can walk, but in some more severe forms, they stop walking during adulthood. Finally, type 4 of the disease has the onset between the 10th and the 30th year of life. They have a normal lifespan, they can stand and walk, and if well trained, they can keep doing so for the rest of their lives 57.

As already mentioned, SMA is a genetic disease. In the early 1990s, two groups were able to assign the locus for the chronic forms to the long arm of chromosome 5 9, 30, 55, 56, 61. In the following years, the structure of the gene called survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) 12, 13, 39, and its regulation, were described 50, 60, 85. Finally, in 2000, the centromeric gene SMN2 was also found 15, 53, 83, 88, and its expression resulted as being responsible for the severity of SMA 29. SMN protein is involved in many different cell processes concerning the splicing 25, 40, 47, 48, 69; it is an ubiquitous protein, meaning that it is present in all the organism's cells, and its absence is not compatible with life. This is shown in the mouse, which contains only one copy of Smn. The knock‐out (KO) mice display massive cell deaths during early embryonic development, indicating that the Smn gene product is necessary for cellular survival and function 82. In humans, the role of the centromeric duplication of the gene SMN is crucial. The SMN2 transcript normally lacks exon 7 because of the C‐to‐T transition at codon 280, which is located in an exonic enhancer 49; it is translationally silent but is necessary and sufficient to dictate exon 7 alternative splicing 50. This difference causes an inefficient production of full‐length transcript from SMN2 gene; moreover, the protein due to lack of exon 7 is less stable 49. If the SMN1 gene is mutated, the presence of SMN2 and its capacity to produce the full‐length transcript is pivotal for the survival of the patient. In this scenario, the number of duplications of SMN2 might influence the severity of the disease; indeed, SMN2 gene can be correctly spliced for less than 20% 49, and this percentage, if SMN1 is mutated and non‐functional, is not sufficient to ensure the correct amount of protein unless there are two or more copies of SMN2.

Ubiquitous Protein That Mostly Affect the Central Nervous System

Since the discovery of the genes involved in the SMA, a main question has arisen within the scientific community:

How can the lack of an ubiquitous protein mostly affect a single subset of the central nervous system neurons, namely the motor neurons?

Also, another question was brought to the attention of the scientists:

Is it really true that the other tissues, different from the nervous ones, are not affected?

Up until now, we can make two hypotheses to explain the molecular mechanisms of the SMA. The first is that the alteration of the level of SMN protein, which constitutes the spliceosome, has altered some important genes in the motor neural circuits, and the second is that SMN protein has other peculiar functions in the motor neurons.

The best‐characterized activity of the SMN complex is the assembly of spliceosome proteins (Sm proteins) onto small nuclear RNA (snRNAs), forming the spliceosomal snRNPs 54. These abundant nuclear RNPs function in the context of a dynamic macromolecular machine known as the spliceosome to carry out the excision of introns and ligation of exons to form mature mRNAs. In 2007, Pellizoni's group 27 demonstrated that the reduction of SMN protein also caused a decrease in the levels of other ribosomal proteins such as Gemini 2, 6 and 7. Moreover, a particular ribosomal protein U11 (a small nuclear RNA‐protein complex), that is, a component of the minor—U12‐type subset of the spliceosome, was affected in the SMA animal models. Indeed, in the first few years of this century, it was discovered that two spliceosomal machineries existed. The majority is in charge of 99% of the introns of the splice, and the minor splices the remainder 66, 67.

The reduced snRNP assembly capacity, as a consequence of low SMN levels, may not automatically translate into a defect of snRNP if the SMN complexes are in excess. In order for snRNP accumulation to be influenced in vivo, the SMN complexes have to fail to gather the demand for Sm core formation on the snRNAs, which is regulated primarily by the rate of small nuclear RNA transcription. Therefore, the physiologically critical parameter is the threshold of SMN activity required to support the cellular level of snRNP, which is development and tissue specific 27.

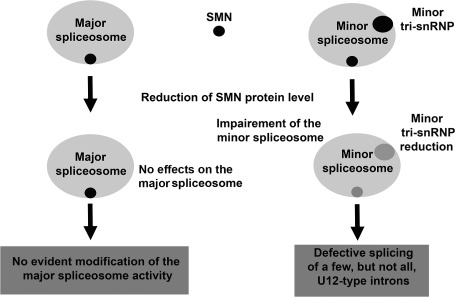

It seems that the processing of minor spliceosome is slower and perhaps more error prone than the major spliceosome under normal conditions, and it might represent a rate‐limiting step for the expression of many genes 67. Decreased levels of minor snRNPs such as U11 may further enhance this situation; furthermore, they have deleterious consequences on the expression of mRNAs containing U12‐type introns in cells of SMA patients 4. Moderate decrease (up to fivefold) in the level of the minor spliceosome does not affect splicing of minor introns 72, whereas a 25‐fold decrease in the level of the minor tri‐snRNP (which is composed by the small nuclear RNAs U4/U5/U6) in lymphoblasts leads to a differential retention of minor introns in vivo 4 (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic description of the changes in spliceosome activity in cells with reduced levels of SMN protein (see text).

Table 1.

Summary of the effects of SMN deficiency in neuron and muscle. Abbreviations: EPC = endplate current; MEPC = miniature endplate current; NMJ = neuromuscular junction; SMA = spinal muscular atrophy

| SMN1 reduction effect in neuron | SMN1 reduction effect in muscle |

|---|---|

| SMN protein absence incompatible with life | |

| Role in minor splicing pathway 27, 54 | |

| Misregulation of neuronal actin dynamics 5 | SMN1 protein interaction with α‐actinin and αB‐crystallin 23 |

| Stasimon expression in cholinergic neurons is necessary and sufficient to fully rescue aberrant neurotransmitter release at the NMJs 51 | Smn muscular mutant mice have a weak regenerative capability in response to necrosis 17 |

| The sensory‐motor circuit dysfunction can be the starting point of motor system deficits in this SMA model 32 | The replacement of high levels of SMN in muscle fibers, but not in the neurons, has no effect on the SMA phenotype or the survival of the animal 28 |

| Co‐culturing human myotubes and embryonic wild‐type rat spinal cord undergo degeneration 1–3 weeks after innervation 7 | |

| miR‐9 was downregulated in the dorsal root ganglion entrapped neurons 77 | In the muscle, the expression of miR‐1 and miR‐133a, which are the most specific muscle miR, decreased after nerve entrapment 77 |

| CT‐1 produced by the muscle after physical training promote the survival of subsets of neurons in the developing peripheral nervous system through activation of transcription factor NF‐κB 58 | |

| Most SMA NMJs remained innervated even later in the course of the disease; however, they showed abnormal synaptic transmission 38 | |

| Animal models of SMA showed a reduction in axon growth, but no alterations in survival or dendrite length. Neurite outgrowth was enhanced in PC12 cells overexpressing Smn 79 | EPC and MEPC decay time constants at the post‐synaptic site were prolonged because of a slowed switch from the fetal (γ) acetylcholine receptor (AChR) subunit to the adult subunit (ε) in SMA models 38, 59 |

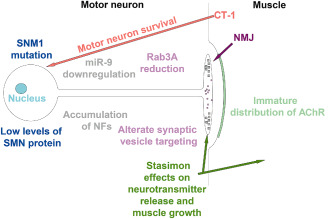

In this regard, while it is clearly established that a reduced amount of SMN protein is responsible for SMA, the molecular mechanism by which this deficiency induces the specific degeneration of motor neurons remains unknown. Based on the proposal that misregulation of neuronal actin dynamics is central to SMA pathogenesis 5 (Table 1), it is noticeable that a high proportion of U12‐type introns are highly present in cytoskeletal‐related organization gene 11, 42. Another recently analyzed gene that might be involved in the disease is Stasimon. The gene target of SMN encodes an evolutionarily conserved transmembrane protein that is required for normal neurotransmitter release by motor neurons in Drosophila melanogaster (drosophila) and motor axon outgrowth in Danio rerio (zebrafish), undergoing SMN‐dependent U12 splicing. In an outstanding paper, a striking similarity in the effects of both Stasimon and SMN deficiency on the electrophysiological properties of drosophila motor neurons was revealed 51. Restoration of Stasimon expression in cholinergic neurons is necessary and sufficient to fully rescue aberrant neurotransmitter release at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) (Figure 3 and Table 1). Moreover, Stasimon is able to strongly counteract muscle growth defects in SMN loss‐of‐function mutants, mimicking the cellular requirement for SMN in the drosophila motor circuit 51.

Figure 3.

Scheme illustrating the changes in the nerve and muscle and NMJ. With the same colours the correlated events are indicated. NF = neurofilaments, miR‐9 = micro‐RNA 9, CT‐1 = cardiotrophin‐1, NJM = neuromuscular junction,  = synaptic vesicles,

= synaptic vesicles,  = neurofilaments accumulation.

= neurofilaments accumulation.

SMN Tissue Expression

The outcome of the SMN1 mutation is mostly a neurological one. However, it has been known that other organs are also affected.

For instance, some patients with severe type 1 SMA have heart defects 80, 84, typically atrial and ventricular septal defects, which are often concurrent with the alteration of the autonomic system, the alteration of the normal heart rhythm that can cause sudden death.

It is also well known that β‐oxidation abnormalities, ie, dicarboxylic aciduria, appear to be distinctive to SMA, compared to normal controls, or other equally debilitating denervating disorders. These abnormalities are proportional to the clinical severity of SMA, as infants with severe SMA have significant abnormalities in levels of fatty acid metabolites, which are not seen in older children with milder forms 19, 35, 87. This evidence raises the possibility that SMN protein can have other functions rather than the mRNA metabolism regulation, or that there is potential loss or alteration of a gene contiguous to SMN 19.

The reduced bone mineral density in SMA is related to the reduced mobility or to the pathophysiological aspects of the disease; for instance, a comparative study with other disorders, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy, does not provide concordant results 37.

An interesting issue could be the change of the expression of SMN (mRNA and protein). A pivotal paper concerning the mRNA expression in human fetuses was produced by Dallapiccola's group 63. SMN mRNA was detected in the spinal cord (dorsal and ventral portions), skeletal muscle, lung, heart, kidney, liver and spleen, indicating that SMN could be considered a housekeeping gene. Differently, the expression of SMN protein changes during the development, and it differs in various tissues. In normal fetuses, the SMN protein is abundant in all the tissues: skeletal muscle, heart, kidney, thymus, brain and pancreas, and it is barely detectable in the lung tissue. In postnatal patients, the level of SMN protein drops consistently in all the tissues, with the exception of the kidney where it was less reduced. In the skeletal muscle, the level of proteins was much lower in the SMA 1 fetuses than in SMA 2 or 3 14.

It was later demonstrated that SMN has a function in the muscle, where it is localized in the sarcomere of the drosophila, or it is co‐localized with α‐actinin in a Z‐line pattern in mammals; in addition, αB‐crystallin (a member of the small heat shock protein family, with a chaperone‐like function) was reported to form a complex with SMN in immortal cell line obtained from cervical cancer (HeLa cells) 23 (Table 1). Thus, the SMN complex can interact with at least two distinct Z‐line proteins, α‐actinin and αB‐crystallin.

Is the Secondary Motor Neuron the Only Cell Type Affected?

On the basis of the data previously reported, the question that arises is whether the lower motor neuron or other cells can play an important role in the physiopathology of the SMA. The identification of the site where the first neuronal degenerative events occur is primary for the understanding of the pathogenesis and for the development of an appropriate pharmacological strategy. In order to achieve this goal, we need to consider what is the meaning of “first neuronal events” because, in some cases, the first cellular structures to degenerate are often not where the first molecular events happen 18.

Furthermore, we can hypothesize that there is a role of the muscular exercise in the attenuation of the symptoms, and if so, which are the retrograde messages from the muscle that can preserve the motor neuron?

The changes in SMN expression during the development allow us to postulate the developmental disease status of the SMA. During skeletal muscle development, myoblasts fuse into myotubes that subsequently become muscle fibers; the primary myotubes are usually present by 8 weeks of development, and they are regarded as classic myotubes with chains of central nuclei. Secondary myotubes with smaller diameters and more widely spaced nuclei usually appear after 13–14 weeks. Myotube diameters in humans tend to decrease between 12 and 15 weeks of gestation 36. On the contrary, in SMA patients, there is an increase of the myotubes size between 12 and 15 weeks 52. In this scenario, the works pursuit by Judith Melki's group have a pivotal role 16, 62. The efforts of the scientists aimed at the understanding of the impact of the Smn1 mutation in the muscle deleting the gene specifically in this tissue. The first mutant mice used (HSA‐Cre, Smn F7/Δ7) display a severe phenotype characterized by necrosis of muscle fibers associated with destabilization of the sarcolemma components 16, a marked reduced lifespan with median survival of 4 weeks, more severe than in mice knocked out for genes encoding components of the dystrophin glycoprotein complex such as dystrophin (mdx mouse). An important characteristic of these mutant mice was the low proportion of myocytes with central nuclei, which suggests a weak regenerative process in response to necrosis 16. For that reason, Melki's group generated a new mouse mutant (HSA‐Cre, Smn F7/F7) where the deletion of the Smn1 gene was present only in the fused myotubes but not in the satellite cells, leading to the necrosis process of myofibers, while the satellite cells remain unaffected. Using these animal models, it was possible to evaluate the regenerative capacity of intact satellite cells in response to the damage of the mature muscle. These mice exhibit mild phenotype with median survival of 8 months and motor performance similar to the controls within the first 6 months of age, despite severe myopathic process. In contrast, mutant mice carrying the (HSA‐Cre, Smn F7/Δ7), in which satellite cells are heterozygously deleted for Smn, develop acute necrosis of muscle fibers, progressive motor paralysis and early death at 1 month of age 16. On the other hand, some experiments pursued by Burghes' laboratory demonstrated that the replacement of high levels of SMN in muscle fibers, but not in the neurons, has no effect on the SMA phenotype or the survival of the animal; on the contrary, replacement of SMN in neurons (which also partially replaced on the muscles) rescues the SMA phenotype and significantly increases survival of the animal 28. The authors were not able to assay the effect of the increased expression of SMN in neurons alone; so, we cannot exclude the possibility that real recovery could be achieved only with the concomitant expression in neurons and muscle. To corroborate these results, it was recently demonstrated that self‐complementary adeno‐associated virus 9 (scAAV9, correcting Smn in SMA pups) can infect ∼60% of motor neurons when injected intravenously into neonatal mice, and it induces a recovery if the treatment is performed in a limited time window (postnatal day 1). Treatment on postnatal day 5 results in partial correction, whereas postnatal day 10 treatment has little effect 26. This treatment, however, induced a significant increase of SMN protein not only in the neurons but also in the muscle; therefore, we cannot exclude that the improvements obtained in the previously described animal model are ascribable to concomitant neuron and muscle SMN expression.

This tight interaction between neuron and muscle was also demonstrated by means of co‐culturing human myotubes and embryonic wild‐type rat spinal cord explants; indeed, myofibers from patients with SMA 1 and 2, but not SMA 3 or other childhood motor neuron diseases, undergo degeneration 1–3 weeks after innervation, indicating that the degeneration was caused by the muscle component, and it was related to the gravity of the SMA disease 7 (Table 1). These authors also demonstrated that the conditioned media of either control or SMA co‐cultures had no influence on survival of any of their pending co‐cultures (using permeable support systems that rule out the possibility of cell contact) 6. The involvement of the muscle degeneration in SMA disease was also studied by means of transplantation approach; in the mutant mouse (HSA‐Cre, Smn F7/F7), bone marrow (BM) stem cells and amniotic fluid stem cells (AFCs) were transplanted. Very interestingly, both transplantations were able to increase the survival; in fact, 50% of the BM‐treated mice and 75% of the AFC‐treated mice survived for 18 months in comparison to the complete death of the untreated group 73. Only AFCs were able to engraft in the muscle stem cell niche for long periods of time (15 months), and they showed a regenerative capacity 73. These results strongly underline the role of muscle preservation on SMA, although the authors did not take in consideration the neural side.

In this scenario, a recent paper by McCabe's group 32 brought new important findings, and it changed the view of the disease. The restricted muscle expression of smn in drosophila model produced no significant increase in the muscle surface area or rhythmic motor output; moreover, it effected locomotion, and it induced changes in NMJ excitatory post‐synaptic potential (eEPSP). On the contrary, the expression of smn under the control of a pan neuronal promoter fully rescued the muscle surface area of smn mutants to control (wild‐type) levels; moreover, this treatment completely restored their locomotor velocity, rhythmic motor output and NMJ eEPSP amplitudes. This result represented a very interesting finding as it was not due to the restoration of the SMN levels in the motor neurons (that in drosophila are glutamatergic) but to the restoration of SMN protein levels in the cholinergic neurons, the major excitatory neuron in this invertebrate. These data indicate the sensory‐motor circuit dysfunction as the starting point of motor system deficits in this SMA model, and they imply that enhancement of motor neural network activity could ameliorate the disease 32.

miRNA and SMA

MicroRNAs (miRNAs or miRs) are endogenous short (on average 23 nucleotides) RNAs that play important gene‐regulatory roles in animals and plants by pairing the mRNAs of protein‐coding genes and directing their post‐transcriptional repression. This category of genes has undergone extensive study because of their involvement in many different cellular mechanisms. It was demonstrated that in a SMA mouse model [mouse ES cells from a Tg(Hlxb9‐GFP)1Tmj Tg (SMN2)89Ahmb Smn1tm1Msd/J mouse Jackson Laboratory], miR‐9 was specifically downregulated 31. miR‐9 is an ancient microRNA, whose mature sequence is 100% conserved across Bilateria. miR‐9 drives progenitor commitment through in the early phases of the development, but concomitantly, it exerts an opposite effect on neurogenesis progression. Human miR‐9 also has a role in proliferation and maturation of early NPCs, and it regulates migration of NPCs in vitro and in vivo 22. Furthermore, miR‐9 possesses the neuronal differentiation and migration promoting activity 76.

In motor neurons, miR‐9 has an important role in the fine‐tuning of the expression of the neurofilament (NF) subunits. In particular, the heavy chain neurofilaments (NEFH) present nine miR‐9 binding sites, dispersed over the 3′UTR of NEFH mRNA. By means of a heterologous reporter assay, it was also demonstrated that miR‐9 is able to modulate the expression of NEFH, and this is dependent on the presence of miR‐9 binding sites at the NEFH mRNA 31. These data strongly suggest a model in which the loss of miR‐9 expression or activity may result in derepression of NEFH and, subsequently, dysregulation of NF stoichiometry. miR‐9 also plays a role in the columnar organization (in chicken), and its concentration regulates the levels of expression of FoxP1, a gene that is involved in the determination of motor neuron subtypes with a still unclear mechanism. Consequently, a dysregulation of miR‐9 could induce a change in the determination of motor neuron subtypes cell fate, in the neural tube 64, 65, and this can have an enormous implication in the functionality of the spinal cord.

miR‐9 has a different role also in the sciatic nerve entrapment or denervation; interestingly, miR‐9 was downregulated (together with other 5 miRNAs) (Figure 3 and Table 1) in the dorsal root ganglion entrapped neurons. Concordantly, in the muscle, the expression of miR‐1 and miR‐133a, which are the most specific muscle miR, decreased after nerve entrapment, indicating that there is an interaction between denervated muscle and nerve 77, which could be present in other neurodegenerative diseases such as SMA.

Physical Inactivity and SMA

Physical inactivity has a high impact on people, reducing their lifespan 8.

The role of myokines in the interaction between muscle and nervous systems can have a pivotal role in some neurological pathologies where the disuse of the muscle is an important issue. These aspects surely have an important influence in people affected by SMA, especially for the one and two forms.

Because the muscle activity is shown to have a big impact in motor neuron homeostasis, and the active muscle produces cytokines that have a role in motor neuron survival, the training can have a fundamental role in SMA patients.

For instance, it has been demonstrated that interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) produced during muscle activity is one of the players 68. For example, IL‐6 is produced and released in response to muscle contractions, and it exerts both its effects locally (acting in an autocrine or paracrine way) within the muscle and, when released into the circulation, peripherally in several organs in a hormone‐like fashion. Contracting skeletal muscle per se is the main source of the IL‐6 in the circulation in response to exercise. In resting human skeletal muscle, the IL‐6 mRNA content is very low, while small amounts of IL‐6 protein are present predominantly in type I fibers 74. Moreover, it was found that an increase in the IL‐6 mRNA content was detectable in the contracting skeletal muscle after 30 minutes of exercise and up to 100‐fold increases may be present at the end of the exercise bout 34.

IL‐6 is a member of the leukemia inhibitory factor/ciliary neurotrophic factor/oncostatin M/interleukin 6/interleukin 11 families of cytokines, several members of this family are known to signal through the transmembrane protein gp130.

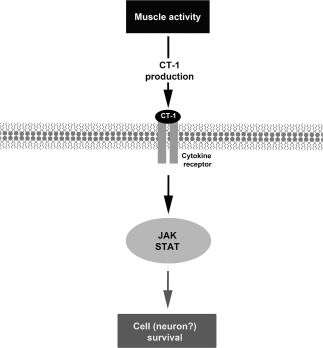

Within this family, the cardiotrophin‐1 (CT‐1) was originally identified in developing embryos, and it is expressed in the heart, skeletal muscle, liver and dorsal root ganglia 71. In adults, human CT‐1 mRNA is detected in the heart, skeletal muscle, ovary, colon, prostate and testis; moreover, it is present in fetal kidney and lung 70. CT‐1 promotes the survival of subsets of neurons in the developing peripheral nervous system through activation of transcription factor NF‐κB 58 (Figures 2 and 3 and Table 1). This myokine was shown to have a role in preventing motor neuron death in animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) 3 and in an animal model of SMA 41. In the SMA preclinical model, intramuscular injection of adenoviral vector expressing CT‐1, even at very low dose improved median survival, delayed motor defect of mutant mice and exerted protective effect against loss of proximal motor axons and aberrant cytoskeletal organization of motor synaptic terminals 41. There is a growing body of evidence that physical training exerts its potential benefits on the individual's health status by modulating the immune system and the whole body metabolism, including the brain functions. An increase of the blood levels of CT‐1 in some athletes during physical training was determined 43. As training induces the expression of CT‐1, we can hypothesize that this cytokine could have a positive effects in SMA patients, and the muscular training could be extremely useful for the preservation of the motor neuron and the NMJ (Figures 2 and 3 and Table 1).

Figure 2.

Hypothetical mechanism that could be involved in the survival of the motor neuron after physical activity. CT‐1 = cardiotrophin‐1; JAK = Janus kinase; STAT = signal transducer and activator of transcription.

NMJ Alteration in SMA

Up to now, we did not take into account an important apparatus that could be damaged in SMA disease: the NMJ. This main site of neural–muscle communication was studied in the mouse model SMA (hSMN2/delta7SMN/mSmn −/−) 38. Surprisingly, most SMA NMJs remained innervated even later in the course of the disease; however, the authors showed abnormal synaptic transmission (Table 1). From the presynaptic site, there was a twofold reduction in the amplitudes of the evoked endplate currents (EPCs); however, normal spontaneous miniature EPC (MEPC) amplitudes indicated a reduced quantal content. Moreover, SMA animal NMJs showed increased facilitation, suggesting a reduced probability of vesicle release and a decreased density of synaptic vesicles, which are likely to contribute to the reduced release probability. On the post‐synaptic position, EPC and MEPC decay time constants were prolonged because of a slowed switch from the fetal (γ) acetylcholine receptor (AChR) subunit to the adult (ε) subunit 38, 59 (Table 1).

On synapse development and maturation point of view, some authors showed a reduction in axon growth, but no alterations in survival or dendrite length in animal models of SMA. Moreover, neurite outgrowth was enhanced in PC12 cells overexpressing Smn (Table 1). The deficiency of full‐length SMN protein leads to alterations of β‐actin protein and mRNA localization in axons and growth cones 79. These in vitro data demonstrate that reduced Smn levels can cause defects in motor neuron outgrowth and path finding, suggesting that defects in these developmental pathways may contribute to SMA pathogenesis. In addition, the cellular defects appear prior to overt symptoms; moreover; they are located and restricted distally to the motor neuron synapse, and they mostly impair the normal maturation of the NMJ. These cellular defects cause neurotransmission alteration which most likely accounts for the profound muscle weakness and motor neuron loss that characterize SMA 33. This maturation is impaired in a SMA 1 animal model because some molecular components of presynaptic terminals were down regulated in normally innervated NMJs of the most severely affected proximal muscles (eg, intercostalis, transversus abdominis and sternomastoid). The levels of Rab3A (a GTP‐binding protein involved in targeting synaptic vesicles to the active zones and in neurotransmitter release in nerve terminals) and calcitonin gene‐related peptide (CGRP) are remarkably reduced (Figure 3), whereas other synaptic vesicle markers such as synaptophysin (SyPhys) and synaptic vesicles (SV) 2 were normal or slightly decreased 20.

The inefficient maturation of the NMJ was already demonstrated by Wirth's group 78. In two of the SMA mouse models, NMJs did not undergo maturation, and the AChR cluster shape remained uniform (Figure 3) [the morphology of the AChR cluster shape was previously classified in four morphology 2: (1) uniform—NMJs are immature and appear as oval plaques with even distribution of AChRs; (2) folds—plaques have bright bands and form post‐synaptic folds; (3) perforated—plaques have single or multiple small holes; and (4) pretzel‐like—plaques have a pretzel‐like shape that is the most mature].

Lin‐Chao's group 89 demonstrated that the depletion, but not the ablation, of a microtubule destabilizing protein, named stathmin/Op18, induced an increase of NMJ maturation respective to the SMA animals (Smn−/−SMN2+/+, carrying four copies of SMN2). In different muscles, such as the tibialis anterior and the gastrocnemius, over 50% of the SMA animals' NMJs were immature, showing uniform plaques. However, the presence at intermediate level of stathmin induced a significantly lower percentage of plaques with a uniform structure and a higher percentage with pretzel‐like structure compared to the SMA animal or the SMA Stmn−/− 89 (Figure 3).

These data suggest that stathmin not only has a role in oxidative stress and inflammation 10 but it may also play a role in the axonal pathogenesis of SMA, although it is not associated with the death of SMA‐like mice.

Axonal Transport Alteration in SMA

In the last years, different authors have tried to describe the mechanisms through which the structural and functional alterations of NMJ abnormalities occur. Initially, the muscles innervated by thoracic motor neurons and lumbar motor neurons were taken as a model 81. A reduction of synaptic vesicles and an accumulation of NFs at the NMJ level of the sciatic nerve branches were already observed 17, 33, 38, so the reduced axonal transport may provide a mechanistic explanation for reduced synaptic vesicle density and concomitant synaptic transmission defects while providing evidence that suggests that NF accumulation results from local NMJ alterations to NFs. NF accumulations might act as a physical barrier in the distal axon contributing to SMA pathogenesis.

In a recent study, Dale and collaborators 21 showed that NF and phosphorylated NF content, from cell body to sciatic nerve, appeared normal in SMAΔ7 mice. Moreover, decreased transport was not due to impaired kinesin function; indeed, kinesin heavy chain Kif5c, which is predominantly utilized in kinesin oligomer formation in motor neurons, was not altered in SMAΔ7 mice. In addition, fast, anterograde transport of synaptic vesicle 2 (SV2‐c) and synaptotagmin (Syt1) proteins was reduced 2 days before the observed decrease in synaptic vesicle density 21, but in this phenomenon, no alteration of expression or reduced kinesin activity was involved. Accordingly, reduced synaptic vesicle densities at SMAΔ7 NMJs may be a consequence of the reduced synaptic vesicle transport and release that dropped by 50% at P14 21. The role of NFs and phosphorylated NFs in SMA was also studied in retinal neuron primary cultures 46. As shown by Dale and collaborators for motor neurons 21, abnormal accumulation of phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated NFs as well as microtubule proteins was detected 46 in the retinal preparation from Smn2B/− mice 24, suggesting that aggregation of NFs is a general phenomenon in the pathology of SMA, which is not restricted to the motor neurons. On the other hand, a further observation of the reduced number in cells expressing calretinin 46, a calcium sensor and binding protein (CaBP), is of relevance for SMA as it already demonstrated the selective vulnerability of motor neurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis at the expression level of CaBP. Motor neurons deficient in CaBPs died early, and those with high levels of CaBPs were spared in mice modeled for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 1. It remains to be determined whether there are changes in CaBP‐expressing cells in the spinal cord of SMA mice.

In this scenario, a recent paper by Ling and collaborators 45 illustrated the heterogeneity of the denervation in many muscles. This denervation is more prominent in muscles located in the head and trunk, but it also occurred in proximal and distal limb muscles. For those reasons, NMJ vulnerability is not solely determined by muscle location, and presynaptic pathology (eg, NF accumulation) did not correlate with NMJ vulnerability to denervation, indicating that the results obtained by Dale 21 cannot be generalized for all the muscles. In a previous paper, Ling and collaborators 44 showed that almost all NMJs in hindlimb muscles of SMNΔ7 mice remained entirely innervated at the last stage of the disease, and they were capable of eliciting muscle contraction, regardless of a small reduction in quantal content. Moreover, the authors showed, in the SMNΔ7 mouse model, a decrease in the number of central synapses, mainly the proprioceptive inputs, on the lateral motor neurons in lumbar spinal segments L3–5 innervating the distal hindlimb muscles. Interestingly, in the studies of autopsied spinal cord tissues from the SMA type I patients, a reduction in synaptophysin immunoreactivity indicating a loss of central synapses has also been reported in the ventral horn of the spinal cord 90. This loss occurs among surviving SMNΔ7 motor neurons devoid of degenerative features; however, the possibility of synapse loss resulting from secondary events in response to neurodegeneration, such as gliosis, cannot be totally ruled out 44. Together, these results raise the possibility that central synapse loss plays an important role in the pathogenesis of SMA.

Conclusions

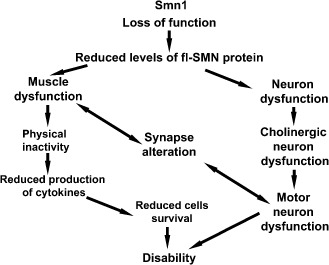

SMA is a multifactorial pathology (Figure 4 and Table 1) triggered by the loss‐of‐function mutations in SMN1 gene and the alteration of the SMN protein function. The cells and the pathways affected by this deficiency are many and are correlated. Up‐to‐date pharmacological, cellular or surgical approaches are ineffective for SMA probably because the focus of the intervention is mostly the motor neuron site.

Figure 4.

Description of a hypothetical flow of the events responsible of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). SMA is a pathology caused by a reduction of the full‐length (fl)SMN protein levels. The motor neurons are the most affected cells, but their loss might not only be due to the reduction of the SMN protein. Retrograde signals from the muscles and the modification at the synapse site can be important players of the motor neuron alteration.

In this review, we analyzed the role of other players that can be involved in the pathology believing that also the muscle itself and the interaction muscle fiber and neuron play an important role in SMA pathology. The muscle and the NMJs can be major players in SMA not only because the mutation of SMN1 gene can reduce its regenerative process in response to necrosis but also because they can send many information to the motor neuron, which helps it to stay alive, including cytokines release, miRNA and neuron–muscle contact. The knowledge of alternative and parallel sites of intervention might open, in the near future, new and real expectations for the solution to the problem.

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply grateful to Francesca D'Urso for manuscript editing. This work was supported by Asamsi ONLUS via Prosciutta, 23‐48018 Faenza (RA), Italy.

References

- 1. Alexianu ME, Ho BK, Mohamed AH, La Bella V, Smith RG, Appel SH (1994) The role of calcium‐binding proteins in selective motor neuron vulnerability in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol 36:846–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bolliger MF, Zurlinden A, Luscher D, Butikofer L, Shakhova O, Francolini M et al (2010) Specific proteolytic cleavage of agrin regulates maturation of the neuromuscular junction. J Cell Sci 123:3944–3955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bordet T, Lesbordes JC, Rouhani S, Castelnau‐Ptakhine L, Schmalbruch H, Haase G, Kahn A (2001) Protective effects of cardiotrophin‐1 adenoviral gene transfer on neuromuscular degeneration in transgenic ALS mice. Hum Mol Genet 10:1925–1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boulisfane N, Choleza M, Rage F, Neel H, Soret J, Bordonne R (2011) Impaired minor tri‐snRNP assembly generates differential splicing defects of U12‐type introns in lymphoblasts derived from a type I SMA patient. Hum Mol Genet 20:641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bowerman M, Anderson CL, Beauvais A, Boyl PP, Witke W, Kothary R (2009) SMN, profilin IIa and plastin 3: a link between the deregulation of actin dynamics and SMA pathogenesis. Mol Cell Neurosci 42:66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Braun S, Croizat B, Lagrange MC, Poindron P, Warter JM (1997) Degeneration of cocultures of spinal muscular atrophy muscle cells and rat spinal cord explants is not due to secreted factors and cannot be prevented by neurotrophins. Muscle Nerve 20:953–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Braun S, Croizat B, Lagrange MC, Warter JM, Poindron P (1995) Constitutive muscular abnormalities in culture in spinal muscular atrophy. Lancet 345:694–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bronnum‐Hansen H, Juel K, Davidsen M, Sorensen J (2007) Impact of selected risk factors on expected lifetime without long‐standing, limiting illness in Denmark. Prev Med 45:49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brzustowicz LM, Lehner T, Castilla LH, Penchaszadeh GK, Wilhelmsen KC, Daniels R et al (1990) Genetic mapping of chronic childhood‐onset spinal muscular atrophy to chromosome 5q11.2–13.3. Nature 344:540–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bsibsi M, Bajramovic JJ, Vogt MH, van Duijvenvoorden E, Baghat A, Persoon‐Deen C et al (2010) The microtubule regulator stathmin is an endogenous protein agonist for TLR3. J Immunol 184:6929–6937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burge CB, Padgett RA, Sharp PA (1998) Evolutionary fates and origins of U12‐type introns. Mol Cell 2:773–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burglen L, Lefebvre S, Clermont O, Burlet P, Viollet L, Cruaud C et al (1996) Structure and organization of the human survival motor neurone (SMN) gene. Genomics 32:479–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burglen L, Spiegel R, Ignatius J, Cobben JM, Landrieu P, Lefebvre S et al (1995) SMN gene deletion in variant of infantile spinal muscular atrophy. Lancet 346:316–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burlet P, Huber C, Bertrandy S, Ludosky MA, Zwaenepoel I, Clermont O et al (1998) The distribution of SMN protein complex in human fetal tissues and its alteration in spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet 7:1927–1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Campbell L, Potter A, Ignatius J, Dubowitz V, Davies K (1997) Genomic variation and gene conversion in spinal muscular atrophy: implications for disease process and clinical phenotype. Am J Hum Genet 61:40–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cifuentes‐Diaz C, Frugier T, Tiziano FD, Lacene E, Roblot N, Joshi V et al (2001) Deletion of murine SMN exon 7 directed to skeletal muscle leads to severe muscular dystrophy. J Cell Biol 152:1107–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cifuentes‐Diaz C, Nicole S, Velasco ME, Borra‐Cebrian C, Panozzo C, Frugier T et al (2002) Neurofilament accumulation at the motor endplate and lack of axonal sprouting in a spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. Hum Mol Genet 11:1439–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Conforti L, Adalbert R, Coleman MP (2007) Neuronal death: where does the end begin? Trends Neurosci 30:159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crawford TO, Sladky JT, Hurko O, Besner‐Johnston A, Kelley RI (1999) Abnormal fatty acid metabolism in childhood spinal muscular atrophy. Ann Neurol 45:337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dachs E, Hereu M, Piedrafita L, Casanovas A, Caldero J, Esquerda JE (2011) Defective neuromuscular junction organization and postnatal myogenesis in mice with severe spinal muscular atrophy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 70:444–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dale JM, Shen H, Barry DM, Garcia VB, Rose FF Jr, Lorson CL, Garcia ML (2011) The spinal muscular atrophy mouse model, SMADelta7, displays altered axonal transport without global neurofilament alterations. Acta Neuropathol 122:331–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Delaloy C, Gao FB (2010) A new role for microRNA‐9 in human neural progenitor cells. Cell Cycle 9:2913–2914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. den Engelsman J, Gerrits D, de Jong WW, Robbins J, Kato K, Boelens WC (2005) Nuclear import of {alpha}B‐crystallin is phosphorylation‐dependent and hampered by hyperphosphorylation of the myopathy‐related mutant R120G. J Biol Chem 280:37139–37148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. DiDonato CJ, Lorson CL, De Repentigny Y, Simard L, Chartrand C, Androphy EJ, Kothary R (2001) Regulation of murine survival motor neuron (Smn) protein levels by modifying Smn exon 7 splicing. Hum Mol Genet 10:2727–2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fischer U, Liu Q, Dreyfuss G (1997) The SMN‐SIP1 complex has an essential role in spliceosomal snRNP biogenesis. Cell 90:1023–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Foust KD, Wang X, McGovern VL, Braun L, Bevan AK, Haidet AM et al (2010) Rescue of the spinal muscular atrophy phenotype in a mouse model by early postnatal delivery of SMN. Nat Biotechnol 28:271–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 27. Gabanella F, Butchbach ME, Saieva L, Carissimi C, Burghes AH, Pellizzoni L (2007) Ribonucleoprotein assembly defects correlate with spinal muscular atrophy severity and preferentially affect a subset of spliceosomal snRNPs. PLoS One 2:e921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gavrilina TO, McGovern VL, Workman E, Crawford TO, Gogliotti RG, DiDonato CJ et al (2008) Neuronal SMN expression corrects spinal muscular atrophy in severe SMA mice while muscle‐specific SMN expression has no phenotypic effect. Hum Mol Genet 17:1063–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gavrilov DK, Shi X, Das K, Gilliam TC, Wang CH (1998) Differential SMN2 expression associated with SMA severity. Nat Genet 20:230–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gilliam TC, Brzustowicz LM, Castilla LH, Lehner T, Penchaszadeh GK, Daniels RJ et al (1990) Genetic homogeneity between acute and chronic forms of spinal muscular atrophy. Nature 345:823–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Haramati S, Chapnik E, Sztainberg Y, Eilam R, Zwang R, Gershoni N et al (2010) miRNA malfunction causes spinal motor neuron disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:13111–13116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Imlach WL, Beck ES, Choi BJ, Lotti F, Pellizzoni L, McCabe BD (2012) SMN Is Required for Sensory‐Motor Circuit Function in Drosophila. Cell 151:427–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kariya S, Park GH, Maeno‐Hikichi Y, Leykekhman O, Lutz C, Arkovitz MS et al (2008) Reduced SMN protein impairs maturation of the neuromuscular junctions in mouse models of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet 17:2552–2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Keller C, Steensberg A, Pilegaard H, Osada T, Saltin B, Pedersen BK, Neufer PD (2001) Transcriptional activation of the IL‐6 gene in human contracting skeletal muscle: influence of muscle glycogen content. FASEB J 15:2748–2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kelley RI, Sladky JT (1986) Dicarboxylic aciduria in an infant with spinal muscular atrophy. Ann Neurol 20:734–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kelly AM, Rubinstein NA (1994) The diversity of muscle fiber types and its origin during development. In: Myology: Basic and Clinica, Engel AG (ed.), pp. 119–133. McGraw‐Hill: New York. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kinali M, Banks LM, Mercuri E, Manzur AY, Muntoni F (2004) Bone mineral density in a paediatric spinal muscular atrophy population. Neuropediatrics 35:325–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kong L, Wang X, Choe DW, Polley M, Burnett BG, Bosch‐Marce M et al (2009) Impaired synaptic vesicle release and immaturity of neuromuscular junctions in spinal muscular atrophy mice. J Neurosci 29:842–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lefebvre S, Burglen L, Reboullet S, Clermont O, Burlet P, Viollet L et al (1995) Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy‐determining gene. Cell 80:155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lefebvre S, Burlet P, Liu Q, Bertrandy S, Clermont O, Munnich A et al (1997) Correlation between severity and SMN protein level in spinal muscular atrophy. Nat Genet 16:265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lesbordes JC, Cifuentes‐Diaz C, Miroglio A, Joshi V, Bordet T, Kahn A, Melki J (2003) Therapeutic benefits of cardiotrophin‐1 gene transfer in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet 12:1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Levine A, Durbin R (2001) A computational scan for U12‐dependent introns in the human genome sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 29:4006–4013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Limongelli G, Calabro P, Maddaloni V, Russo A, Masarone D, D'Aponte A et al (2010) Cardiotrophin‐1 and TNF‐alpha circulating levels at rest and during cardiopulmonary exercise test in athletes and healthy individuals. Cytokine 50:245–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ling KK, Lin MY, Zingg B, Feng Z, Ko CP (2010) Synaptic defects in the spinal and neuromuscular circuitry in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. PLoS One 5:e15457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ling KK, Gibbs RM, Feng Z, Ko CP (2012) Severe neuromuscular denervation of clinically relevant muscles in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet 21:185–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liu H, Beauvais A, Baker AN, Tsilfidis C, Kothary R (2011) Smn deficiency causes neuritogenesis and neurogenesis defects in the retinal neurons of a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Dev Neurobiol 71:153–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu Q, Dreyfuss G (1996) A novel nuclear structure containing the survival of motor neurons protein. EMBO J 15:3555–3565. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Liu Q, Fischer U, Wang F, Dreyfuss G (1997) The spinal muscular atrophy disease gene product, SMN, and its associated protein SIP1 are in a complex with spliceosomal snRNP proteins. Cell 90:1013–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lorson CL, Androphy EJ (2000) An exonic enhancer is required for inclusion of an essential exon in the SMA‐determining gene SMN. Hum Mol Genet 9:259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lorson CL, Hahnen E, Androphy EJ, Wirth B (1999) A single nucleotide in the SMN gene regulates splicing and is responsible for spinal muscular atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:6307–6311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lotti F, Imlach WL, Saieva L, Beck ES, Hao Le T, Li DK et al (2012) An SMN‐dependent U12 splicing event essential for motor circuit function. Cell 151:440–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Martinez‐Hernandez R, Soler‐Botija C, Also E, Alias L, Caselles L, Gich I et al (2009) The developmental pattern of myotubes in spinal muscular atrophy indicates prenatal delay of muscle maturation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 68:474–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McAndrew PE, Parsons DW, Simard LR, Rochette C, Ray PN, Mendell JR et al (1997) Identification of proximal spinal muscular atrophy carriers and patients by analysis of SMNT and SMNC gene copy number. Am J Hum Genet 60:1411–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Meister G, Eggert C, Fischer U (2002) SMN‐mediated assembly of RNPs: a complex story. Trends Cell Biol 12:472–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Melki J, Abdelhak S, Sheth P, Bachelot MF, Burlet P, Marcadet A et al (1990) Gene for chronic proximal spinal muscular atrophies maps to chromosome 5q. Nature 344:767–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Melki J, Sheth P, Abdelhak S, Burlet P, Bachelot MF, Lathrop MG et al (1990) Mapping of acute (type I) spinal muscular atrophy to chromosome 5q12‐q14. The French Spinal Muscular Atrophy Investigators. Lancet 336:271–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mercuri E, Bertini E, Iannaccone ST (2012) Childhood spinal muscular atrophy: controversies and challenges. Lancet Neurol 11:443–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Middleton G, Hamanoue M, Enokido Y, Wyatt S, Pennica D, Jaffray E et al (2000) Cytokine‐induced nuclear factor kappa B activation promotes the survival of developing neurons. J Cell Biol 148:325–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Missias AC, Chu GC, Klocke BJ, Sanes JR, Merlie JP (1996) Maturation of the acetylcholine receptor in skeletal muscle: regulation of the AChR gamma‐to‐epsilon Switch. Dev Biol 179:223–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Monani UR, Lorson CL, Parsons DW, Prior TW, Androphy EJ, Burghes AH, McPherson JD (1999) A single nucleotide difference that alters splicing patterns distinguishes the SMA gene SMN1 from the copy gene SMN2. Hum Mol Genet 8:1177–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Munsat TL, Skerry L, Korf B, Pober B, Schapira Y, Gascon GG et al (1990) Phenotypic heterogeneity of spinal muscular atrophy mapping to chromosome 5q11.2–13.3 (SMA 5q). Neurology 40:1831–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nicole S, Desforges B, Millet G, Lesbordes J, Cifuentes‐Diaz C, Vertes D et al (2003) Intact satellite cells lead to remarkable protection against Smn gene defect in differentiated skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol 161:571–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Novelli G, Calza L, Amicucci P, Giardino L, Pozza M, Silani V et al (1997) Expression study of survival motor neuron gene in human fetal tissues. Biochem Mol Med 61:102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Otaegi G, Pollock A, Hong J, Sun T (2011) MicroRNA miR‐9 modifies motor neuron columns by a tuning regulation of FoxP1 levels in developing spinal cords. J Neurosci 31:809–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Otaegi G, Pollock A, Sun T (2011) An optimized sponge for microRNA miR‐9 affects spinal motor neuron development in vivo . Front Neurosci 5:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Patel AA, Steitz JA (2003) Splicing double: insights from the second spliceosome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4:960–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Patel AA, McCarthy M, Steitz JA (2002) The splicing of U12‐type introns can be a rate‐limiting step in gene expression. EMBO J 21:3804–3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pedersen L, Pilegaard H, Hansen J, Brandt C, Adser H, Hidalgo J et al (2011) Exercise‐induced liver chemokine CXCL‐1 expression is linked to muscle‐derived interleukin‐6 expression. J Physiol 589:1409–1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pellizzoni L, Kataoka N, Charroux B, Dreyfuss G (1998) A novel function for SMN, the spinal muscular atrophy disease gene product, in pre‐mRNA splicing. Cell 95:615–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Pennica D, Swanson TA, Shaw KJ, Kuang WJ, Gray CL, Beatty BG, Wood WI (1996) Human cardiotrophin‐1: protein and gene structure, biological and binding activities, and chromosomal localization. Cytokine 8:183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pennica D, Wood WI, Chien KR (1996) Cardiotrophin‐1: a multifunctional cytokine that signals via LIF receptor‐gp 130 dependent pathways. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 7:81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Pessa HK, Ruokolainen A, Frilander MJ (2006) The abundance of the spliceosomal snRNPs is not limiting the splicing of U12‐type introns. RNA 12:1883–1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Piccoli M, Franzin C, Bertin E, Urbani L, Blaauw B, Repele A et al (2012) Amniotic Fluid Stem Cells Restore the Muscle Cell Niche in a HSA‐Cre, Smn(F7/F7) Mouse Model. Stem Cells 30:1675–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Plomgaard P, Penkowa M, Pedersen BK (2005) Fiber type specific expression of TNF‐alpha, IL‐6 and IL‐18 in human skeletal muscles. Exerc Immunol Rev 11:53–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Prior TW, Russman BS (1993) Spinal Muscular Atrophy. 1993–2000 (Updated 2011 Jan 27) Edition. University of Washington: Seattle. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Qu Q, Shi Y (2009) Neural stem cells in the developing and adult brains. J Cell Physiol 221:5–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Rau CS, Jeng JC, Jeng SF, Lu TH, Chen YC, Liliang PC et al (2010) Entrapment neuropathy results in different microRNA expression patterns from denervation injury in rats. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 11:181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Riessland M, Ackermann B, Forster A, Jakubik M, Hauke J, Garbes L et al (2010) SAHA ameliorates the SMA phenotype in two mouse models for spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet 19:1492–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Rossoll W, Jablonka S, Andreassi C, Kroning AK, Karle K, Monani UR, Sendtner M (2003) Smn, the spinal muscular atrophy‐determining gene product, modulates axon growth and localization of beta‐actin mRNA in growth cones of motoneurons. J Cell Biol 163:801–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rudnik‐Schoneborn S, Heller R, Berg C, Betzler C, Grimm T, Eggermann T et al (2008) Congenital heart disease is a feature of severe infantile spinal muscular atrophy. J Med Genet 45:635–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ruiz R, Casanas JJ, Torres‐Benito L, Cano R, Tabares L (2010) Altered intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in nerve terminals of severe spinal muscular atrophy mice. J Neurosci 30:849–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Schrank B, Gotz R, Gunnersen JM, Ure JM, Toyka KV, Smith AG, Sendtner M (1997) Inactivation of the survival motor neuron gene, a candidate gene for human spinal muscular atrophy, leads to massive cell death in early mouse embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:9920–9925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Schwartz M, Sorensen N, Hansen FJ, Hertz JM, Norby S, Tranebjaerg L, Skovby F (1997) Quantification, by solid‐phase minisequencing, of the telomeric and centromeric copies of the survival motor neuron gene in families with spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet 6:99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Shababi M, Habibi J, Yang HT, Vale SM, Sewell WA, Lorson CL (2010) Cardiac defects contribute to the pathology of spinal muscular atrophy models. Hum Mol Genet 19:4059–4071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Strasswimmer J, Lorson CL, Breiding DE, Chen JJ, Le T, Burghes AH, Androphy EJ (1999) Identification of survival motor neuron as a transcriptional activator‐binding protein. Hum Mol Genet 8:1219–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Sugarman EA, Nagan N, Zhu H, Akmaev VR, Zhou Z, Rohlfs EM et al (2012) Pan‐ethnic carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis for spinal muscular atrophy: clinical laboratory analysis of >72 400 specimens. Eur J Hum Genet 20:27–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Tein I, Sloane AE, Donner EJ, Lehotay DC, Millington DS, Kelley RI (1995) Fatty acid oxidation abnormalities in childhood‐onset spinal muscular atrophy: primary or secondary defect(s)? Pediatr Neurol 12:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Velasco E, Valero C, Valero A, Moreno F, Hernandez‐Chico C (1996) Molecular analysis of the SMN and NAIP genes in Spanish spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) families and correlation between number of copies of cBCD541 and SMA phenotype. Hum Mol Genet 5:257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Wen HL, Ting CH, Liu HC, Li H, Lin‐Chao S (2013) Decreased stathmin expression ameliorates neuromuscular defects but fails to prolong survival in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Neurobiol Dis 52:94–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Yamanouchi Y, Yamanouchi H, Becker LE (1996) Synaptic alterations of anterior horn cells in Werdnig‐Hoffmann disease. Pediatr Neurol 15:32–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]