Abstract

High dietary fat and/or cholesterol intake is a risk factor for multiple diseases and has been debated for multiple sclerosis. However, cholesterol biosynthesis is a key pathway during myelination and disturbances are described in demyelinating diseases. To address the possible interaction of dyslipidemia and demyelination, cholesterol biosynthesis gene expression, composition of the body's major lipid repositories and Paigen diet‐induced, systemic hypercholesterolemia were examined in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis (TME) using histology, immunohistochemistry, serum clinical chemistry, microarrays and high‐performance thin layer chromatography. TME‐virus (TMEV)‐infected mice showed progressive loss of motor performance and demyelinating leukomyelitis. Gene expression associated with cholesterol biosynthesis was overall down‐regulated in the spinal cord of TMEV‐infected animals. Spinal cord levels of galactocerebroside and sphingomyelin were reduced on day 196 post TMEV infection. Paigen diet induced serum hypercholesterolemia and hepatic lipidosis. However, high dietary fat and cholesterol intake led to no significant differences in clinical course, inflammatory response, astrocytosis, and the amount of demyelination and remyelination in the spinal cord of TMEV‐infected animals. The results suggest that down‐regulation of cholesterol biosynthesis is a transcriptional marker for demyelination, quantitative loss of myelin‐specific lipids, but not cholesterol occurs late in chronic demyelination, and serum hypercholesterolemia exhibited no significant effect on TMEV infection.

Keywords: cholesterol biosynthesis, high‐performance thin layer chromatography, hypercholesterolemia, microarray, multiple sclerosis, Paigen diet, Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis

Introduction

Half a century ago, a positive correlation between high dietary fat intake and the risk for developing multiple sclerosis (MS) was described 79. Since then, numerous studies have been conducted investigating high‐fat diets, obesity and hypercholesterolemia as possible risk factors for MS 2, 21, 29, 47, 80, 91, 98, 101. However, conflicting findings of various studies allowed no final conclusion about possible beneficial or detrimental effect of high‐fat diets on initiation and progression of demyelinating diseases 2, 16, 37, 73, 101. Increasing evidence suggests that obesity and subsequent dyslipidemia is an important comorbidity in MS 53. Changes in lifestyle due to physical and mental impairment were suggested as possible contributing factors 53. In addition, recent studies revealed an association between an adverse lipid profile [high serum levels of total cholesterol, low‐density lipoproteins (LDLs) and triglycerides] and progressing disease severity 30, 81, 82, 95, 96. Adverse lipid profiles, especially low high‐density lipoproteins (HDLs) and high LDL levels, are known to act as pro‐inflammatory mediators either initiating or exacerbating inflammatory diseases such as atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome and obesity 22.

The hallmark of the progressive form of MS is ongoing myelin destruction and a failure of sufficient remyelination 23, 66, 85, 86. Only about 20% of MS patients display prominent remyelination 65. Paradoxically, the presence of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), predecessors of myelin‐forming oligodendrocytes, was repeatedly described in MS lesions 13, 24, 39, 74. The differentiation and maturation process of OPCs seems to be dysregulated by unknown factors leading to a failure of remyelination. This has been shown for MS and in some related animal models 13, 24, 44, 46, 78, 89.

Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis (TME) is an experimentally, virus‐induced, inflammatory, demyelinating disease of the spinal cord. Observations in TME indicate a robust association of down‐regulated cholesterol biosynthesis with demyelination and deterioration of the clinical score 88. As cholesterol biosynthesis is described as a rate‐limiting step in myelin synthesis 70, an altered cholesterol biosynthesis is suggested as a possible pathomechanistic factor inhibiting remyelination 88. Imbalances of the lipid and cholesterol metabolism in MS and several animal models of demyelinating diseases have frequently been described 15, 17, 27, 97. Decreased cholesterol levels have been observed in MS lesions as well as in the normal appearing white and gray matter of MS patients 17, 27, 97. Under physiological conditions, cholesterol is synthesized locally de novo in the central nervous system (CNS) and the blood–brain barrier shields the brain cholesterol pool from the circulatory cholesterol pool. Nonetheless, brain endothelial cells have the possibility of LDL uptake through luminal receptors 9, 36. Interestingly, under pathological conditions, the interaction between the CNS and circulatory cholesterol seems to be enhanced 4, 5, 14, 43, 48, 67, 69, 71, 102. Moreover, a physiologic hypercholesterolemia is observed during the peak of the myelination process 18, 90. Similarly, administration of dietary lipids during pregnancy and lactation apparently had an accelerating effect on the myelination of the CNS 72. Furthermore, feeding high levels of cholesterol resulted in an increased brain cholesterol level in rats 19 and rabbits 76.

Because of the controversial discussion about the efficacy of statins, 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl‐coenzyme‐A reductase (HMG‐CoA‐reductase) inhibitors 93, as possible treatment of MS, further studies investigating the interaction between demyelinating diseases and cholesterol biosynthesis are required. In particular, studies that address the role of cholesterol biosynthesis on disease progression of MS, with particular emphasis on its potential beneficial effect on remyelination, are required. Therefore, the hypothesis of this study was that dietary cholesterol supplementation influences demyelination and remyelination in TME. The aims were threefold and included: (i) detailed analysis of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway on the transcriptional level; (ii) quantitative analysis of the lipid composition of spinal cord, blood serum and liver; and (iii) determination of the effect of experimentally induced, systemic hypercholesterolemia on TME infection.

Materials and Methods

Microarray experiment

Microarray analysis of transcriptional changes was performed with SJL/JHanHsd mice (Harlan Winkelmann, Borchen, Germany) intracerebrally infected with 1.63 × 106 plaque forming units (PFU) per mouse of the BeAn strain of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) in comparison with mock‐infected mice at 14, 42, 98 and 196 days post infection (dpi), as described previously 88. Briefly, six biological replicates were used per group and time point, except for five TMEV‐infected mice at 98 dpi. RNA was isolated from frozen spinal cord specimens using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), amplified and labeled with the Message‐Amp II‐Biotin enhanced kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) and hybridized to Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Quality control and low level analysis of raw fluorescence intensities were performed with RMAExpress 10. MIAME‐compliant data sets are deposited in the ArrayExpress database (E‐MEXP‐1717; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress). In order to focus on the transcriptional changes related to cholesterol biosynthesis, 22 genes of the canonical cholesterol biosynthesis pathway of Metacore™ database (version 6.5, GeneGo, St. Joseph, MO, USA) and 22 manually selected individual genes involved in cholesterol metabolism and transport (Supporting Information Table S1) were individually analyzed using pair‐wise Mann–Whitney U‐tests (IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 21, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was generally accepted as P ≤ 0.05.

Feeding experiment

Three‐week‐old female SJL/J mice (Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany) were randomly grouped into two feeding groups and fed with conventional mouse diet (low‐fat control diet; product number: S2205‐E010, ssniff Spezialdiäten GmbH, Soest, Germany; Table 1), or Paigen diet (high‐fat Paigen 1.25% cholesterol diet; product number: S2205‐E015, ssniff Spezialdiäten GmbH; Table 1) 63, beginning 13 days prior to the infection (−13 dpi) for the complete time of the experiment ad libitum with free access to tap water. The animals were housed in isolated ventilated cages (Tecniplast, Hohenpeißenberg, Germany). At the age of 5 weeks, animals from the two feeding groups were inoculated into the right cerebral hemisphere with 1.63 × 106 PFU/mouse of the Bean strain of TMEV as previously described 87, 88, 89. Mock infection was performed with solvent only 87, 88, 89. At 7, 21, 42, 98 and 196 dpi, six animals per group (except 5 mice at 42 dpi in mock‐infected, Paigen diet‐fed group) were sacrificed after general anesthesia as described 87.

Table 1.

Diet composition. Abbreviation: ME = metabolized energy

| Food ingredients | Control diet S2205‐E010 (% dry weight) | High‐fat Paigen diet S2205‐E015 (% dry weight) |

|---|---|---|

| Casein | 20.00 | 20.00 |

| Cornstarch | 30.00 | — |

| Maltodextrin | 20.39 | 0.94 |

| Dextrose | 11.00 | — |

| Sucrose | — | 50.00 |

| Cellulose | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| DL‐methionine | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| L‐cystine | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Vitamin premixture | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mineral premixture, AIN93G | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Choline Cl | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Butylated hydroxytoluene | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Cholesterol | — | 1.25 |

| Corn oil | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Soybean oil | 6.00 | — |

| Cocoa butter | — | 15.20 |

| ME (Atwater) (MJ/kg) | 16.2 | 18.5 |

| ME (Atwater) (kcal/g) | 3.9 | 4.4 |

| kcal% protein | 18 | 16 |

| kcal% fat | 17 | 36 |

| kcal% carbohydrates | 65 | 48 |

Diet composition in percent dry weight of the conventional diet, used as control diet, and the cholesterol‐rich, high‐fat Paigen diet, used to induce hypercholesterolemia in female SJL/J mice applied as a maintenance diet from 14 days prior to the infection with Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus or mock substance over the complete studied period of 196 days post infection.

Immediately after death organs were removed, brain and liver were weighted (Sartorius TE13S‐DS, Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany). For histology and immunohistochemistry, the organs were fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h and embedded in paraffin wax (formalin fixed and paraffin embedded, FFPE). For lipid analysis, specimens were immediately snap‐frozen and stored at −80°C. For cryo‐sections liver was embedded into Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (OCT; Tissue‐Tek® O.C.T.™ compound, Sakura, Alphen aan den Rijn, Netherlands). Additionally, spinal cord segments were fixed with 5% glutaraldehyde/cacodylate buffer for 24 h, post fixated with 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated and embedded in epoxy resin 7, 89. The animal experiments were authorized by the local authorities (Regierungspräsidium, Hannover, Germany, permission number: AZ: 33.14‐42502‐04‐11/0517).

Clinical examination and rotarod analysis

The clinical course was evaluated weekly employing weight measurements (Sartorius TE13S‐DS) and Rotarod testing (RotaRod Treadmill, TSE Technical & Scientific Equipment, Bad Homburg, Germany). Prior to infection, mice were trained twice at −13 and −7 dpi for 10 minutes at a constant speed of 5 or 10 rpm (rounds per minute), respectively. For the measurements, the rod speed was linearly increased from 5 to 55 rpm over a time period of 5 minutes and the attained rpm at drop was analyzed for significant differences between the groups using three‐factorial ANOVA with repeated measures and post hoc independent t‐tests for the factors status of infection, time point post infection and feeding regimen using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 21). A mean score per mouse was calculated from three trials per day 88. Statistical significance was generally accepted as P ≤ 0.05.

Clinical chemistry

Blood was collected immediately after death from vena cava caudalis. Serum was stored at −80°C. Serum concentration of total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides, alanine transaminase (ALT), gamma‐glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), glutamate dehydrogenase (GLDH), total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, albumin, urea (Cobas®, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and free fatty acids (FFA; Wako chemicals GmbH, Neuss, Germany) was measured with a Hitachi Automatic Bioanalyzer (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Arithmetic means with 5%–95% confidence interval of mock‐infected animals fed with normal diet were used as reference values.

Histological examination

Serial sections of FFPE liver specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), Heidenhain's azan trichrome stain and Fouchet's stain, and were semiquantitatively scored for lipidosis (0 = no lipidosis; 1 = single foci of lipidosis; 2 = mild lipidosis; 3 = moderate lipidosis; 4 = marked lipidosis; 5 = severe, diffuse lipidosis), type of intracytoplasmic lipid droplets (micro‐ or macrovesicular), fibrosis (0 = no fibrosis; 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe), cholestasis (0 = no cholestasis; 1 = mild; 2 = moderate; 3 = severe), and the presence of inflammatory infiltrates and necrosis, respectively 83. Cryo‐sections of the liver were stained with Oil red O stain and the percentage of Oil red O positive area was morphometrically assessed using the analySis 3.1 software package (SOFT Imaging System, Münster, Germany) 31.

FFPE transversal sections of the ascending aorta, heart and large pulmonary arteries were stained with HE and examined for pathomorphological changes by light microscopy.

FFPE transverse sections of cervical, thoracic and lumbar spinal cord segments were stained with HE and Luxol fast blue‐cresyl violet (LFB‐CV) and evaluated semiquantitatively for meningitis, leukomyelitis (0 = no changes; 1 = scattered infiltrates; 2 = 2–3 layers of inflammatory cells; 3 = more than 3 layers of inflammatory cells) and demyelination (0 = no changes; 1 = ≤25%; 2 = 25%–50%; 3 = 50%–100% white matter affected) 33, 87, 88. Demyelination and remyelination in the spinal cord were assessed semiquantitatively in semi‐thin, epoxy resin‐embedded, toluidine blue‐stained, transverse sections of cervical, thoracic and lumbar spinal cord (0 = no changes; 1 = ≤25%; 2 = 25%–50%; 3 = 50%–100% of white matter affected) 89. A mean score per mouse was calculated from cervical, thoracic and lumbar spinal cord scores.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on serial FFPE transverse spinal cord sections using the avidin‐biotin‐peroxidase complex (ABC) method (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) with 3,3′‐diaminobezidine‐tetrahydrochloride (DAB) as chromogen 89. The antibodies applied were anti‐CD3 (polyclonal rabbit anti‐human, diluted 1:1000, Dako A0452, Hamburg, Germany) for T‐lymphocytes, anti‐CD107b (monoclonal rat anti‐mouse biotinylated, clone M3/84, diluted 1:800, Serotec MCA2293B, Oxford, UK) for microglia/macrophages, anti‐IgG (goat anti‐mouse‐IgG, diluted 1:200, Vector Laboratories, BA9200) for plasma cells, anti‐glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; polyclonal rabbit anti‐cow, diluted 1:1000, Dako Z0334) for astrocytes, anti‐myelin basic protein (MBP; polyclonal rabbit anti‐human, diluted 1:1600, Merck/Millipore AB980, Darmstadt, Germany) for myelin, anti‐periaxin (PRX; polyclonal rabbit anti‐human; diluted 1:5000; Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for peripheral myelin, anti‐neural/glial‐antigen 2 (NG2; polyclonal rabbit anti‐rat, diluted 1:400, Merk/Millipore AB5320) for OPCs and anti‐TMEV (polyclonal rabbit anti‐TMEV capsid protein VP1, diluted 1:2000) for virus detection. The density of NG2, MBP, CD3, IgG, CD107b, PRX and TMEV immunopositive cells per square millimeter was calculated by dividing the number of immunopositive cells counted manually in the thoracic spinal cord section by the measured area of the spinal cord 78, 89. The percentage of MBP‐positive white matter area and GFAP‐positive spinal cord area was calculated by dividing the computationally detected immunopositive area by the total white matter area employing analySis 3.1 software package 78, 88, 89. Clinical chemistry, histology and immunohistochemistry were analyzed using Kruskal–Wallis tests followed by pair‐wise post hoc Mann–Whitney U‐tests with Bonferroni correction independently for the factors infection, time and feeding group (IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 21). Statistical significance was generally accepted as P ≤ 0.05.

High‐performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) of liver and spinal cord

HPTLC was performed to analyze liver and spinal cord cell membrane lipids. Lipids were extracted and prepared for HPTLC with minor modifications as previously described 11. Briefly, liver and spinal cord samples were homogenized in multiple steps and dissolved in methanol and chloroform (2:1). The upper aqueous layer was removed and the remaining fraction was vacuum‐dried and stored at −20°C. Liver and spinal cord lipid samples were dissolved in chloroform/methanol (1:1) solution, applied on HPTLC Silica gel 60 glass plates (Merck), and run with three subsequent running solutions consisting of acetic acid ethyl ester/1‐propanol/chloroform/methanol/0.25% potassium chloride (27:27:27:11:10), n‐hexane/diethyl ether/acetic acid (75:23:2) and 100% n‐hexane. For visualization of the lipid bands, plates were stained in phosphoric acid/copper sulfate (10:7.5) solution. Lipid bands were identified by comparison to authentic standards (Sigma‐Aldrich) and analyzed using the CP ATLAS software (http://www.lazarsoftware.com/index.html). Results were corrected for variable input amount of tissue and normalized across the technical repeats. An average intensity of two repeats for each sample was calculated. Statistical significance was calculated by three‐factorial ANOVA and post hoc independent t‐tests (IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 21). Statistical significance was generally accepted as P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Clinical course and histopathological changes in the spinal cord in TMEV‐infected animals fed with control diet

TMEV‐infected mice showed a progressive decline of motor performance in the rotarod assay (Figure 1). At 195 dpi, rotarod performance was reduced to 32.1% of the baseline measurement at 0 dpi (Figure 1). TMEV‐infected animals achieved significant less rpm compared to mock‐infected mice from 49 to 196 dpi. Pathohistological examination of the spinal cord demonstrated a mononuclear inflammation of the meninges and within the white matter in TMEV‐infected mice compared to control mice beginning with 7 dpi (Figures 1 and 2). The infiltrates were composed of CD3‐positive T‐lymphocytes, IgG‐producing B‐lymphocytes and few CD107b‐positive macrophages (Figure 1). The inflammation in the parenchyma of the white matter was dominated by CD107b‐positive macrophages; to a lesser extent, CD3‐positive T‐lymphocytes and IgG‐producing B‐lymphocytes were detectable. CD3‐positive T‐lymphocytes represented the first cellular response to TMEV infection with a significantly higher cell density as early as 7 dpi in TMEV‐infected animals compared to mock‐infected animals (Figure 1). A significantly higher amount of IgG‐producing B‐lymphocytes and CD107b‐positive macrophages was detectable beginning with 42 dpi in all TMEV‐infected mice compared to mock‐infected mice (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Rotarod performance and inflammatory changes in the spinal cord. A. Rotarod performance at 0–195 days post infection (dpi) of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)‐infected female SJL/J mice (n = 6) compared to mock‐infected female SJL/J mice (n = 6; except mock infected; Paigen diet group: 42 dpi n = 5) grouped into two feeding groups (control diet; Paigen diet). Performance is displayed as rounds per minute (rpm). B–D. Cell density of inflammatory infiltrates characterized by immunohistochemistry of the animals described in (A) at 7, 21, 42, 98 and 196 dpi for (B) CD3‐positive T‐lymphocytes, (C) IgG‐producing B‐lymphocytes and (D) CD107b‐positive macrophages. The cell density is displayed as box‐and‐whisker plots showing the median and 95% percentile. Statistical significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) as detected by pair‐wise Mann–Whitney U‐tests are marked with asterisks (★) for the comparison of TMEV‐infected animals with mock‐infected animals of the same feeding group. Statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) between Paigen diet and control diet‐fed animals of the same infection group are marked with a dot (●).

Figure 2.

Demyelination and remyelination in the spinal cord. Light microscopy of thoracic spinal cord in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus ( TMEV )‐infected female SJL/J mice and mock‐infected female SJL/J mice grouped into two feeding groups (control diet; P aigen diet). A–D. Hematoxylin and eosin‐stained ventral thoracic spinal cord at 196 dpi. TMEV infection induced a mild to moderate, mononuclear infiltration in the meninges and the perivascular space of the white matter and a progressive demyelination. Pathohistological examination of mock‐infected animals was unremarkable. Pictures were taken with a 20‐fold objective. The bar indicates 50 μm. E–H. Luxol fast blue‐cresyl violet‐stained ventral thoracic spinal cord at 196 dpi. TMEV infection induced a severe progressive demyelination. No demyelination was observed in mock‐infected animals. Pictures were taken with a 20‐fold objective. The bar indicates 50 μm. I–L. Epoxy resin‐embedded semi‐thin toluidine blue‐stained ventral thoracic spinal cord sections at 196 dpi. Remyelinated axons are characterized by thinner myelin sheaths than normal. Myelin debris can be found intra‐cytoplasmatically in macrophages. Pictures were taken with a 60‐fold immersion oil objective. The bar indicates 10 μm. M–N. Semiquantitative scoring (0–3) of (M) demyelination, assessed in Luxol fast blue‐cresyl violet‐stained spinal cord section and (N) remyelination, assessed in semi‐thin toluidine blue‐stained spinal cord sections at 7, 21, 42, 98 and 196 dpi. The scores are displayed as box‐and‐whisker plots showing the median and 95% percentile. Statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) as detected by pair‐wise Mann–Whitney U‐tests are marked with asterisks (★) for the comparison of TMEV‐infected animals with mock‐infected animals of the same feeding group. Statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) between Paigen diet and control diet‐fed animals of the same infection group are marked with a dot (●).

First demyelinated foci were detected at 21 dpi as assessed in LFB‐CV‐stained spinal cord sections. The amount of demyelination progressively increased until 196 dpi (Figure 2). Evaluation of HE‐ and toluidine blue‐stained specimens confirmed the results obtained in LFB‐CV‐stained spinal cord sections with a strong correlation of the three independent evaluations (Spearman's correlation, HE, r = 0.95, P ≤ 0.05; toluidine blue, r = 0.89, P ≤ 0.05; Figure 2; Supporting Information Figures S1 and S2). The amount of demyelination, as determined by the MBP‐immunopositive white matter area, was in accordance with the semiquantitative histological evaluation using LFB‐CV. Beginning at 98 dpi, TMEV‐infected animals showed a progressively decreasing MBP immunoreactivity of the white matter compared to mock‐infected animals (Figure 3). NG2‐positive cell density was significantly increased in TMEV‐infected animals compared to mock‐infected animals, starting at 98 dpi (Figure 3). Remyelination, semiquantitatively assessed in semi‐thin toluidine blue‐stained spinal cord sections, was progressively increasing from 42 to 196 dpi in TMEV‐infected animals (Figure 2; Supporting Information Figures S1 and S2). PRX immunohistochemistry indicated an involvement of Schwann cell remyelination in this process by an increasing number of PRX‐immunopositive cells at 98 and 196 dpi (Figure 3). The amount of astrogliosis assessed by immunohistochemistry showed an increase in the GFAP‐immunopositive area with a statistical significance at 42 and 196 dpi (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry confirmed the presence of viral antigen in the spinal cords of the TMEV‐infected animals in association to inflammatory and demyelinating changes with a prominent expression starting at 42 dpi.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical assessment of demyelination and remyelination in the spinal cord. A. Myelin basic protein (MBP)‐immunopositive positive white matter area. B. Density of neuron/glial‐antigen 2 (NG2)‐immunopositive cells. C. Density of periaxin (PRX)‐immunopositive cells. D. Glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP)‐immunopositive spinal cord area of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)‐infected female SJL/J mice (n = 6) compared with mock‐infected female SJL/J mice (n = 6; except mock infected; Paigen diet group: 42 dpi n = 5) grouped into two feeding groups (control diet; Paigen diet) at 7, 21, 42, 98 and 196 days post infection. The scores are displayed as box‐and‐whisker plots showing the median and 95% percentile. Statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) as detected by pair‐wise Mann–Whitney U‐tests are marked with asterisks (★) for the comparison of TMEV‐infected animals with mock‐infected animals of the same feeding group. Statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) between Paigen diet and control diet‐fed animals of the same infection group are marked with a dot (●).

Analysis of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway on the transcriptional level

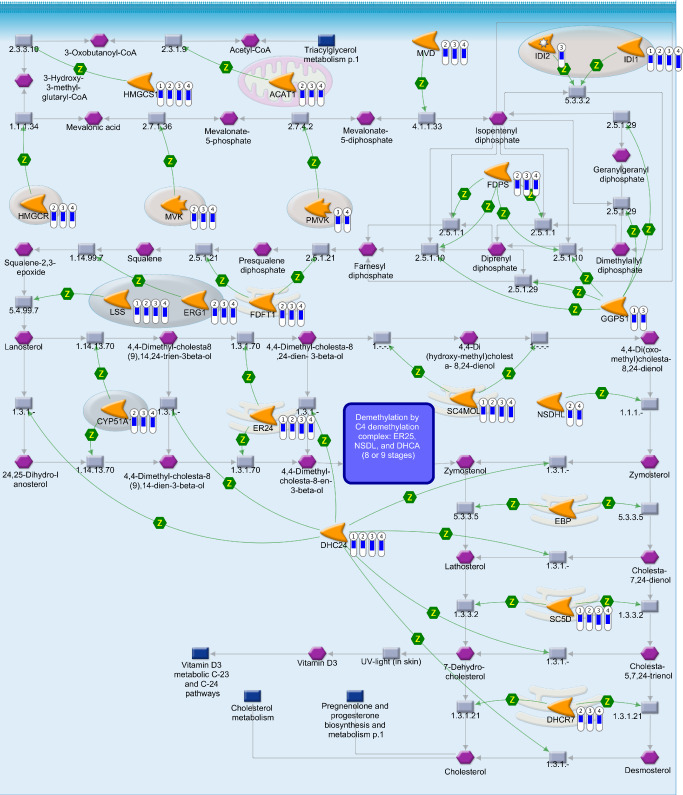

In order to focus on cholesterol biosynthesis, a subset of 22 genes representing the Metacore™ cholesterol biosynthesis pathway was analyzed in detail (Figure 4; Supporting Information Table S1). The low level and pathway analysis of the complete data set has been described in detail in a previous publication 88. Independent analysis of manually selected genes employing traditional statistical methods revealed that nearly all genes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis are mildly down‐regulated in TMEV‐infected animals compared to mock‐infected animals on at least one time point (Figure 4; Supporting Information Table S1). There were 7, 17, 17 and 18 significantly down‐regulated genes detected at 14, 42, 98 and 196 dpi, respectively (Figure 4; Supporting Information Table S1). Seven of these genes were differentially regulated at all time points. When ranked according to their fold change, these seven genes were among the most severely down‐regulated transcripts within the animals with prominent demyelination at 98 and 196 dpi. The most severe down‐regulation was detected for isopentenyl‐diphosphate delta isomerase (Idi1). Additional analysis of single, manually selected genes involved in cholesterol metabolism and transport showed that 7‐dehydrocholesterol reductase (Dhcr7) and cytochrome P450, family 46, subfamily a, polypeptide 1 (Cyp46a1) were significantly down‐regulated beginning at 42 dpi, the first day of significant demyelination in TME. In contrast, apolipoprotein E (Apoe) and ATP‐binding cassette, sub‐family A (ABC1), member 1 (Abca1) were significantly up‐regulated (Supporting Information Table S1).

Figure 4.

Canonical cholesterol biosynthesis pathway map in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis. Transcriptional changes associated with cholesterol biosynthesis pathway in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)‐infected mice in comparison with mock‐infected control mice, illustrated in the canonical cholesterol biosynthesis pathway map from Metacore™ database (Genego, St. Joseph, MI, USA). The bars labeled from one to four display the fold changes of significantly differentially regulated genes in TMEV‐infected animals (n = 6) compared with mock‐infected animals (n = 6) on 4 days post infection (dpi) employing pair‐wise Mann–Whitney U‐tests (P ≤ 0.05) (1 = 14 dpi; 2 = 42 dpi; 3 = 98 dpi; 4 = 196 dpi). The blue indicator scale of the bar marks the down‐regulation and displays a comparable measurement of the magnitude of the negative fold change. Green arrows = positive functional interaction; Z = catalysis; gray arrows = technical links; orange icons = enzymes; purple hexagons = generic compound; blue rectangle = normal process; gray rectangle = reaction. Acat1 = acetyl‐Coenzyme A acetyltransferase 1; Cyp51 = cytochrome P450, family 51; Dhcr24 = 24‐dehydrocholesterol reductase; Dhcr7 = 7‐dehydrocholesterol reductase; Ebp = phenylalkylamine Ca2+ antagonist (emopamil) binding protein; Fdft1 = farnesyl diphosphate farnesyl transferase 1; Fdps = farnesyl diphosphate synthetase; Ggps1 = geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase 1; Hmgcr = 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl‐Coenzyme A reductase; Hmgcs1 = 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl‐Coenzyme A synthase 1; Idi1 = isopentenyl‐diphosphate delta isomerase; Idi2 = isopentenyl‐diphosphate delta isomerase 2; Lss = lanosterol synthase; Mvd = mevalonate (diphospho) decarboxylase; Mvk = mevalonate kinase; Nsdhl = NAD(P)‐dependent steroid dehydrogenase‐like; Pmvk = phosphomevalonate kinase; Sc4mol = sterol‐C4‐methyl oxidase‐like; Sc5d = sterol‐C5‐desaturase (fungal ERG3, delta‐5‐desaturase) homolog (Saccharomyces cerevisiae); Sqle = squalene epoxidase; Tm7sf2 = transmembrane 7 superfamily member 2.

Quantitative analysis of the lipid composition of blood serum, liver and spinal cord

The lipid composition of blood serum, liver and spinal cord was measured in order to detect the influence of TMEV infection on the major storage pools of the body. No significant influence of TMEV infection on the serum levels of total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides and FFA was observed (Figure 5). Similarly, TMEV infection did not influence levels of triglycerides, FFA, cholesterol, monoacylglycerol, phosphatidylethanolamine, cardiolipin, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin compared to mock‐infected animals in the liver (Figure 6). Galactocerebroside was below the threshold in the liver. In the spinal cord, galactocerebroside and sphingomyelin levels were significantly decreased in TMEV‐infected animals at 196 dpi (Figure 7). Triglyceride, free fatty acids, cholesterol, monoacylglycerol, cardiolipin, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylcholine were not affected by TMEV infection at any time point (Figure 7).

Figure 5.

Blood serum lipid levels. Serum lipid levels at 7, 21, 42, 98 and 196 days post infection (dpi) of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)‐infected female SJL/J mice (n = 6; TMEV‐infected, control diet group: 7 dpi n = 3) compared to mock‐infected female SJL/J mice (n = 6; except mock infected; Paigen diet group: 42 dpi n = 5) grouped into two feeding groups (control diet; Paigen diet) as measured with Hitachi Automatic Bioanalyzer. Data of (A) total cholesterol, (B) low‐density lipoprotein, (C) high‐density lipoprotein, (D) triglycerides and (E) free fatty acids are displayed in mmol/L as box‐and‐whisker plots showing the median and 95% percentile. Statistical significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) as detected by pair‐wise Mann–Whitney U‐tests are marked with asterisks (★) for the comparison of TMEV‐infected animals with mock‐infected animals of the same feeding group. Statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) between Paigen diet and control diet‐fed animals of the same infection group are marked with a dot (●).

Figure 6.

Quantitative lipid composition and light microscopy of the liver. A. Lipid composition of the liver at 98 days post infection (dpi) of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus‐infected female SJL/J mice (n = 6; TMEV‐infected, control diet group: 7 dpi n = 3) compared to mock‐infected female SJL/J mice (n = 6; for A–C except mock infected; Paigen diet group: 42 dpi n = 5) grouped into two feeding groups (control diet; Paigen diet). Displayed are the lipid intensity values per sample weight, as measured with high‐performance thin layer chromatography. Bars show the median and 95% percentile. Statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) as detected by three‐factorial ANOVA with post hoc independent t‐tests are marked with asterisks (★) for the comparison of TMEV‐infected animals with mock‐infected animals of the same feeding group. Statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) between Paigen diet and control diet‐fed animals of the same infection group are marked with a dot (●). B–I. Exemplary light microscopy of the liver from a TMEV‐infected, control diet‐fed mouse (left) and a TMEV‐infected, Paigen diet‐fed mouse (right) at 98 dpi. B–C. Hematoxylin and eosin stain, a moderate to severe, multifocal to diffuse, centrolobularly accentuated, microvesicular hepatic lipidosis was detectable in all Paigen diet‐fed mice. D–E. Heidenhain's azan trichrome stain; a mild, multifocal, hepatic fibrosis associated with the fatty degeneration was detectable in Paigen diet‐fed animals. F–G. Fouchet's stain; no cholestasis in any of the groups was detectable. H–I. Oil red O stained area was significantly higher in TMEV‐ and mock‐infected, Paigen diet‐fed mice compared to control diet‐fed mice. Pictures were taken with a 10‐fold objective for (B–C), 20‐fold objective for (D–G) and 40‐fold objective for (H–I). The bar indicates 100 μm in (B–C), 50 μm in (D–G)and 20 μm in (H–I).

Figure 7.

Lipid composition of the spinal cord. Lipid composition of the spinal cord of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus‐infected female SJL/J mice (n = 6) compared to mock‐infected female SJL/J mice (n = 6; except mock infected; Paigen diet group: 42 dpi n = 5) grouped into two feeding groups (control diet; Paigen diet) on (A) 21 days post infection (dpi), (B) 42 dpi, (C) 98 dpi and (D) 196 dpi. Displayed are lipid intensity values per sample weight, as measured with high‐performance thin layer chromatography. The data are displayed as bars showing the median and 95% percentile. Statistical significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) as detected by three‐factorial ANOVA with post hoc independent t‐tests are marked with asterisks (★) for the comparison of TMEV‐infected animals with mock‐infected animals of the same feeding group. Statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) between Paigen diet and control diet‐fed animals of the same infection group are marked with a dot (●).

Influence of hypercholesterolemia on TMEV infection

Peripheral metabolic and pathomorphological changes

Paigen diet significantly increased the body weight in TMEV‐infected animals from −7 to 140 dpi compared to the TMEV‐infected, control diet group (Figure 8; mock‐infected, control diet mean = 19.29 g, SD = 2.50; TMEV‐infected, control diet mean = 16.91 g, SD = 1.44; mock‐infected, Paigen diet mean = 22.73 g, SD = 3.84; TMEV‐infected, Paigen diet mean = 19.27 g, SD = 1.97).

Figure 8.

Body weight. Mean body weight in gram (g) over time (days post infection; dpi) of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)‐infected female SJL/J mice (n = 6) compared to mock‐infected female SJL/J mice (n = 6; except mock infected; Paigen diet group: 42 dpi n = 5) grouped into two feeding groups (control diet; Paigen diet).

In order to detect the influence of Paigen diet on systemic cholesterol repositories, blood serum and liver were analyzed. Over the entire investigated period (7–196 dpi), TMEV‐ and mock‐infected mice fed with Paigen diet displayed a significant increase in serum total cholesterol and LDL levels compared with control diet mice of the same infection group (Figure 5). TMEV‐infected, Paigen diet‐fed mice displayed a trend toward lower total cholesterol levels beginning at 42 dpi with a significant difference observed at 98 dpi compared to mock‐infected, Paigen diet‐fed mice (Figure 5). A significant increase in serum HDL levels was measured at 21, 42 and 98 dpi in TMEV‐ and mock‐infected, Paigen diet‐fed mice compared to TMEV‐ and mock‐infected control diet‐fed mice (Figure 5). A trend toward decreased serum triglyceride levels with statistical significance at 21, 42 and 196 dpi was observed in Paigen diet, TMEV‐infected mice compared to control diet, TMEV‐infected animals (Figure 5). Paigen diet, TMEV‐infected mice showed a trend toward lower free fatty acid serum levels as compared to Paigen diet, mock‐infected mice, with a statistical significance at 42 and 98 dpi. Serum albumin levels showed a trend to lower levels in Paigen diet, TMEV‐infected mice compared to control diet, TMEV‐infected mice with a statistical significance at 7 and 98 dpi. No differences were detected between feeding groups or between TMEV‐ and mock‐infected mice for ALT, GLDH. GGT, total bilirubin and direct bilirubin were under the detection limit of 3 IU/L, 1.7 μmol/L and 1.5 μmol/L, respectively.

Paigen diet induced a significantly higher liver weight compared to the control diet‐fed animals in TMEV‐ and mock‐infected animals. Histological examination of the liver revealed a moderate to severe, multifocal to diffuse, centrolobularly accentuated, microvesicular hepatic lipidosis in 89.9% of all Paigen diet‐fed mice (Figure 6). Oil red O positive area was significantly higher in all Paigen diet‐fed mice compared to control diet‐fed mice (Figure 6). A mild, multifocal, periportally accentuated, hepatic fibrosis was associated with the fatty degeneration in all Paigen diet‐fed mice in 22.0% of the animals beginning with 98 dpi (Figure 6). The inflammatory response in the liver showed no significant difference between the feeding groups. No necrosis or cholestasis was detectable in any of the groups.

HPTLC analysis of the liver lipid content revealed a significant increase in the amount of triglycerides and cholesterol in TMEV‐ and mock‐infected, Paigen diet‐fed mice at 98 dpi. Phosphatidylinositol was increased only in TMEV‐infected, Paigen diet‐fed mice compared to TMEV‐infected, control diet‐fed mice. Free fatty acid, monoacylglycerol, phosphatidylethanolamine, cardiolipin, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin showed comparable levels in Paigen diet and control diet groups (Figure 6).

Histological examination of the heart, aorta and large pulmonary arteries was performed to exclude Paigen diet‐induced atherosclerotic changes. In 6% of all animals, a mild, multifocal lymphohistioplasmacytic infiltration within the myocardium with no significant alteration due to TMEV infection or the feeding regimen was detectable. Furthermore, a mild, focal, lymphohistioplasmacytic, subintimal or intramural infiltration was found in the aorta of 3% of the animals and in large pulmonary arteries in 1% of the animals with no significant alteration due to infection or feeding regimen.

CNS metabolic and pathomorphological changes

The feeding regimen had no influence on the motor performance of the animals as determined by the rotarod assay. Rotarod performance in TMEV‐infected, Paigen diet mice was reduced to 24.53% at 195 dpi compared to their performance at 0 dpi (Figure 1).

Scoring the degree of meningitis, leukomyelitis and demyelination revealed no significant difference between the feeding groups in TMEV‐infected animals (Figures 1 and 2; Supporting Information Figures S1 and S2). Immunohistochemical evaluation of the amount and quality of inflammatory infiltrates, MBP‐positive white matter area and GFAP‐positive area revealed no significant difference between TMEV‐infected, Paigen diet‐fed mice and TMEV‐infected, control diet‐fed mice (Figures 1 and 3). NG2‐positive cell density was significantly increased in TMEV‐infected animals compared to mock‐infected animals, starting at 42 dpi in the Paigen diet group and at 98 dpi in the control diet group. At 196 dpi, TMEV‐infected, Paigen diet mice had a significantly decreased number of NG2‐immunopositive cells compared to TMEV‐infected, control diet mice (Figure 3). The feeding regimen had no influence on the amount and timing of remyelination or the amount of Schwann cell remyelination (Figures 2 and 3; Supporting Information Figures S1 and S2).

The quantitative analysis of the lipid content of the spinal cord detected a significantly higher level of sphingomyelin only at 98 dpi in TMEV‐infected, Paigen diet‐fed mice compared to TMEV‐infected, control diet‐fed mice. No effect of the feeding regimen was detectable on 21, 42 and 196 dpi (Figure 7). Similarly, the quantity of triglyceride, free fatty acid, cholesterol, monoacylglycerol, galactocerebroside, phosphatidylethanolamine, cardiolipin, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylcholine was not influenced by the feeding regimen (Figure 7).

Discussion

Previous studies reported inconsistent results concerning the role of cholesterol and high‐fat diet as a pathomechanistic factor 2, 16, 21, 29, 37, 47, 73, 80, 91, 98, 101 or comorbidity of MS 53. However, cholesterol biosynthesis is a key pathway during the physiologic myelination process 69, and transcriptional down‐regulation of cholesterol biosynthesis is the most important biological function associated with demyelination in TME 88. Here, we addressed the question whether dietary cholesterol supplementation influences demyelination and remyelination in TME by: (i) detailed analysis of the transcriptional changes along the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway; (ii) quantitative analysis of the lipid composition of spinal cord, blood serum and liver during TMEV infection; and (iii) determination of the effect of experimentally induced, systemic hypercholesterolemia on TMEV infection.

Transcriptional profiling of cholesterol biosynthesis

On the transcriptional level, we observed an overall down‐regulation of genes associated with cholesterol biosynthesis, comparable to observations in myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)‐induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in rats 58, and in MS patients 51. This down‐regulation was suggested to be a transcriptional representation of a reduced capacity for myelin repair 51. The majority of the examined genes showed progressive down‐regulation, indicating a continuous decline in the ability to synthesize cholesterol. This correlates with the chronic progressive clinical course of TME. Seven genes of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway were down‐regulated at all examined time points. The rather early decrease in their expression, already at 14 dpi, indicates their regulatory importance or a special vulnerability of oligodendrocytes triggered by the viral infection or the inflammatory changes in the environment. Idi1 was identified as the gene with the strongest down‐regulation. It encodes an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of isopentenyl diphosphate to dimethylallyl diphosphate, a substrate for farnesyl synthesis 100. Reduced activity of IDI1 is known to be the main pathomechanism in the Zellweger syndrome and neonatal adrenoleukodystrophy 45. The neuropathological lesions in these disorders include an inflammatory demyelination, noninflammatory dysmyelination and nonspecific reduction of the myelin volume in the white matter. Furthermore, Dhcr24 and Sc5d were down‐regulated on all time points. Mutations in Dhcr24 diminish the reduction of the delta‐24 double bond of sterol intermediates during cholesterol biosynthesis 92. Mutations in Sc5d diminish the transformation of lanosterol into 7‐dehydrocholesterol 42. Both result in a phenotype similar to the human Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome (SLOS) 69. SLOS is elicited by an inherited mutation in DHCR7, a gene responsible for the conversion of 7‐dehydrocholesterol to cholesterol. The disorder is characterized by dysmyelinogenesis 12, 20, 40. Dietary cholesterol supplementation is one of the standard therapies in this disease 12, 20, 40. Down‐regulation of DHCR7 was described not only in MS lesions, but also in the normal appearing white matter of affected patients. Dhcr7 was down‐regulated in our data at 42, 98 and 196 dpi. This finding suggests a down‐regulation of cholesterol biosynthesis prior to demyelination 49. Additionally, down‐regulation was detected for Hmgcs1 in all studied time points compared to mock‐infected animals. A mutation in Hmgcs1, a gene encoding for the enzyme that mediates the condensation of acetyl‐CoA and acetoacetyl‐CoA to 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl‐CoA, seems to be responsible for a misdirected migration of OPCs causing a lack of interaction between glial cells and axons resulting in a failure to express myelin genes 55. Moreover, the detected down‐regulation of Cyp46a1, encoding an important cholesterol‐removing enzyme, and the increased gene expression of Apoe and Abca1, both involved in the efflux and transport of cholesterol, lead in all likelihood to changes in CNS cholesterol homeostasis 54.

Based on these observations, it can be concluded that the observed failure of sufficient remyelination is associated by a down‐regulation of genes described above. Observations during developmental myelination suggested the presence of specific checkpoints to ensure sufficient production of cholesterol to precede brain myelination 26, 35. Considering the concept of an orchestrated remyelination process, it seems plausible that the suggested dysregulation of OPCs in MS and its animal models may be caused by insufficient cholesterol biosynthesis. However, a down‐regulation of genes associated with cholesterol biosynthesis as a secondary reaction to an overabundance of available cholesterol as a consequence of demyelination might reduce the necessity of de novo synthesis of cholesterol. In this context, the increased gene expression of Apoe and Abca1 might indicate the enhanced transport rate of cholesterol between the cells. A secondary decrease of mRNA expression associated with cholesterol biosynthesis due to a progressive loss of oligodendrocytes represents another possible mechanism. To further elucidate the underlying processes, the lipid composition of the main cholesterol repositories in the body was analyzed in the second part of the study.

Changes in the lipid composition of blood serum, liver and spinal cord

Recent studies indicate that serum dyslipidemia could be a comorbidity of MS 53. Different MRI studies in MS patients showed an association of an adverse lipid profile with disability progression 30, 81, 82, 95, 96, an effect we could not reproduce in the present study. It can eventually be related to the fact that mice have relatively high HDL and low LDL levels under physiological conditions 28. Therefore, the mouse is generally not as susceptible as humans to a disruption of this lipoprotein balance 28. However, results vary in the human diseases. In one study, MS patients' plasma levels of triglycerides were increased, whereas LDL levels decreased in comparison to healthy controls 64. Another study reported increased total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and triglyceride serum levels in MS patients 77.

In the spinal cord, galactocerebroside (galactosylceramide; GalC) and sphingomyelin levels were significantly decreased in TMEV‐infected animals compared to mock‐infected animals at 196 dpi. GalC is the most typical myelin lipid and is used as a marker for mature oligodendrocytes 6. GalC is proportional to the amount of myelin during development 61. GalC‐deficient mice show impaired insulator function of the myelin sheath 6. Sphingomyelin is involved in cell adhesion and forms lipid rafts with cholesterol for signal transduction 66; for a review see 50. Interestingly, cholesterol levels were not different between TMEV‐ and mock‐infected animals, although a decrease in cholesterol is described in lesions and normal appearing white matter in MS patients 17, 27, 97. However, our findings are in line with a study in EAE. In the latter, transcriptional changes in cholesterol biosynthesis and transport, but no alterations in spinal cord cholesterol levels, were detected 58. A plausible explanation could be the different degradation capacities for various lipid components in the myelin sheath and the sustained duration of the disease in human patients. Under physiological circumstances, myelin‐incorporated cholesterol has a half‐life of about 300 days. In contrast, cerebrosides have a half‐life of about 20 days 3. Furthermore, hyperactivities of degradation enzymes as described for the hydrolysis of sphingomyelin may play a central role 99. However, an impaired response or clearing activity of macrophages might represent a possible cause for the poor clearance of myelin debris leading to dysregulation of OPC differentiation 44, 68.

Influence of hypercholesterolemia on TMEV infection

Because we did not detect serum dyslipidemia in a lipid balanced diet, we were interested in the influence of hypercholesterolemia in TME. A possible beneficial effect of cholesterol supplementation appeared to be plausible in view of our microarray study. Moreover, in an in vitro study, treatment with statins leads to the formation of abnormal myelin membranes 52 or retraction of processes and cell death of OPCs and oligodendrocytes, which could be rescued by cholesterol supplementation 56. Furthermore, fat‐deficient diet in rats led to an increased susceptibility for EAE 75. However, cholesterol supplementation has never been offered as a potential treatment for MS likely due to controversially discussed negative impact of high‐fat diets as a possible etiological factor for MS 2, 47, 80, 91, 94, 98. However, as demonstrated in SLOS, dietary cholesterol supplementation can have a beneficial effect in the setting of disturbed myelination 12, 20, 40.

In the present study, we could neither see an anticipated beneficial effect due to the higher circulatory availability of cholesterol, nor detect a negative impact of a high cholesterol diet on the development of the disease. This was substantiated by clinical assessment, histology and immunohistochemistry. The amount, onset or duration of meningitis, leukomyelitis, demyelination or remyelination remained unchanged. The reason for the significantly decreased density of NG2‐positive cells in the TMEV‐infected, Paigen diet‐fed mice compared with TMEV‐infected, control diet‐fed animals of 35.4% at 196 dpi remains elusive. These observations cannot be explained by an increased differentiation of OPCs to myelinating oligodendrocytes, because no consecutive increase in myelinated area was detectable. Similar to previous studies in TME, an increased number of OPCs without maturation to myelinating oligodendrocytes was demonstrated at earlier time points 89. Interestingly, a similar differentiation arrest was observed in a cuprizone experiment in simvastatin‐treated animals 57.

An interesting finding, however, was the increase of sphingomyelin levels in the spinal cord at 98 dpi in TMEV‐infected Paigen diet‐fed mice compared to TMEV‐infected control diet‐fed mice. Sphingomyelin accounts for about 20% of the phospholipid in plasma lipoproteins and is increased in response to high cholesterol diet and metabolic abnormalities 59. Previous studies showed that brain capillaries are able to take up sphingomyelin from the circulatory 8, 38. The uptake in myelinating brains was higher than in mature brains 8. Increased sphingomyelin levels have been described to be beneficial in brain vulnerability to oxidative stress 32. On the other hand, sphingomyelin is thought to be involved in multiple neurological disorders 1, 34. However, the results of the present study showed no secondary effect of the increased sphingomyelin levels; therefore, the biological relevance remains unclear.

Surprisingly, our results are in contrast to a similar feeding experiment using a Western‐type lipid‐rich diet conducted in MOG‐induced EAE in C57BL/6J mice 84. They show that a high‐fat diet increases the immune cell infiltration, inflammatory mediator production, and exacerbates neurologic symptoms in EAE 84. The difference may be caused by the different mouse strains used or the mode in which myelin loss is induced. The C57BL/6J mice used by Timmermans et al are known to be one of the most atherosclerosis‐sensitive strains 28, whereas the SJL/J mouse strain develops a significant hypercholesterolemia, despite a relative resistance to atherosclerosis, when fed with Paigen diet 60, 62. In contrast to Paigen diet, Western‐type diet is known to have a higher atherogenic potential 28. Thus, the increased inflammatory reaction in Timmermans et al could be a secondary effect of atherosclerotic changes or caused by the C57BL/6‐specific inflammatory response to high‐fat diets 25, 41.

Clinical chemistry showed significantly elevated total cholesterol, HDL, LDL and free fatty acids in the blood serum of all Paigen diet‐fed animals. The observed down‐regulation of triglycerides as an effect of the Paigen diet is well known in atherosclerosis research 28, 60, 62.

Based on the insights gained in this study, it can be concluded that down‐regulation of cholesterol biosynthesis is a robust transcriptional marker for demyelination in TME, similar to EAE 58 and MS 51. Furthermore, demyelination and remyelination in the chronic progressive disease represent two processes that develop and precede independently from serum cholesterol levels, most likely because of an inability of circulatory cholesterol to enter the CNS due to a closed blood–brain barrier. Moreover, serum hypercholesterolemia and dyslipidemia exhibit no negative effect on virus‐induced, inflammatory demyelination in the CNS in this atherosclerosis‐resistant mouse strain. The reported findings could indicate that the inconclusive reports regarding dyslipidemia and MS are influenced by rather indirect pathomechanistic factors and/or the confounding influence of the respective genetic predisposition toward atherosclerosis.

Funding

This study was in part supported by Niedersachsen‐Research Network on Neuroinfectiology (N‐RENNT) of the Ministry of Science and Culture of Lower Saxony, Germany. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Wenhui Sun and Yanyong Sun received a grant from the China Scholarship Council (CSC) under File No. 2010617013 and File No. 2009617013, respectively.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author Contribution

R.U., U.D., H.Y.N. and W.B. initiated the scientific research; B.B.R., W.S, G.B., Y.S., P.K. and F.C. performed the experiments; R.U., B.B.R., W.S., A.K., U.D. and F.C. analyzed the data; B.B.R., W.S., R.U., W.B., F.C., G.B. and H.Y.N. edited the manuscript.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Light microscopy of epoxy resin‐embedded semi‐thin toluidine blue‐stained spinal cord.

Figure S2. Semiquantitative assessment of demyelination.

Table S1. Fold changes and P‐values of genes associated with cholesterol synthesis, metabolism and transport.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anuschka Unold, Thomas Feidl and Martin Gamber [Department of Non‐Clinical Drug Safety, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co KG, Biberach (Riß), Germany] for excellent technical support in microarray technology and Priv.‐Doz. Dr Gunter Eckert (Department of Pharmacology, Goethe‐University, Frankfurt, Germany) for kindly providing his protocols for lipid analysis. We also thank Petra Grünig, Bettina Buck and Caro Schütz (Department of Pathology, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Hannover, Germany) for excellent technical support. The BeAn strain of TMEV was a generous gift of Prof. H.L. Lipton, Department of Microbiology‐Immunology, University of Illinois, Chicago, IL, USA.

References

- 1. Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF (2008) Altered lipid metabolism in brain injury and disorders. Subcell Biochem 49:241–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alter M, Yamoor M, Harshe M (1974) Multiple sclerosis and nutrition. Arch Neurol 31:267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ando S, Tanaka Y, Toyoda Y, Kon K (2003) Turnover of myelin lipids in aging brain. Neurochem Res 28:5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balazs Z, Panzenboeck U, Hammer A, Sovic A, Quehenberger O, Malle E, Sattler W (2004) Uptake and transport of high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) and HDL‐associated alpha‐tocopherol by an in vitro blood‐brain barrier model. J Neurochem 89:939–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baron W, Hoekstra D (2010) On the biogenesis of myelin membranes: sorting, trafficking and cell polarity. FEBS Lett 584:1760–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baumann N, Pham‐Dinh D (2001) Biology of oligodendrocyte and myelin in the mammalian central nervous system. Physiol Rev 81:871–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baumgärtner W, Krakowka S, Blakeslee JR (1987) Persistent infection of Vero cells by paramyxoviruses. A morphological and immunoelectron microscopic investigation. Intervirology 27:218–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bentejac M, Bugaut M, Delachambre MC, Lecerf J (1989) Utilization of high‐density lipoprotein sphingomyelin by the developing and mature brain in the rat. J Neurochem 52:1495–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Björkhem I, Meaney S (2004) Brain cholesterol: long secret life behind a barrier. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24:806–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP (2003) A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19:185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brogden G, Propsting M, Adamek M, Naim HY, Steinhagen D (2014) Isolation and analysis of membrane lipids and lipid rafts in common carp (Cyprinus carpio L. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol 169:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Caruso PA, Poussaint TY, Tzika AA, Zurakowski D, Astrakas LG, Elias ER et al (2004) MRI and 1H MRS findings in Smith‐Lemli‐Opitz syndrome. Neuroradiology 46:3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang A, Nishiyama A, Peterson J, Prineas J, Trapp BD (2000) NG2‐positive oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in adult human brain and multiple sclerosis lesions. J Neurosci 20:6404–6412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chrast R, Saher G, Nave KA, Verheijen MH (2011) Lipid metabolism in myelinating glial cells: lessons from human inherited disorders and mouse models. J Lipid Res 52:419–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Confaloni AM, D'Urso D, Salvati S, Serlupi Crescenzi G (1988) Dietary lipids and pathology of nervous system membranes. Ann Ist Super Sanita 24:171–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Coo H, Aronson KJ (2004) A systematic review of several potential non‐genetic risk factors for multiple sclerosis. Neuroepidemiology 23:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cumings JN (1955) Lipid chemistry of the brain in demyelinating diseases. Brain 78:554–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dietschy JM, Turley SD (2004) Thematic review series: brain lipids. Cholesterol metabolism in the central nervous system during early development and in the mature animal. J Lipid Res 45:1375–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dufour F, Liu QY, Gusev P, Alkon D, Atzori M (2006) Cholesterol‐enriched diet affects spatial learning and synaptic function in hippocampal synapses. Brain Res 1103:88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elias ER, Irons MB, Hurley AD, Tint GS, Salen G (1997) Clinical effects of cholesterol supplementation in six patients with the Smith‐Lemli‐Opitz syndrome (SLOS). Am J Med Genet 68:305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Esparza ML, Sasaki S, Kesteloot H (1995) Nutrition, latitude, and multiple sclerosis mortality: an ecologic study. Am J Epidemiol 142:733–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Esteve E, Ricart W, Fernandez‐Real JM (2005) Dyslipidemia and inflammation: an evolutionary conserved mechanism. Clin Nutr 24:16–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ferguson B, Matyszak MK, Esiri MM, Perry VH (1997) Axonal damage in acute multiple sclerosis lesions. Brain 120 (Pt 3):393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Franklin RJ (2002) Why does remyelination fail in multiple sclerosis? Nat Rev Neurosci 3:705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Friedman G, Ben‐Yehuda A, Dabach Y, Hollander G, Babaey S, Ben‐Naim M et al (2000) Macrophage cholesterol metabolism, apolipoprotein E, and scavenger receptor AI/II mRNA in atherosclerosis‐susceptible and ‐resistant mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20:2459–2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fünfschilling U, Jockusch WJ, Sivakumar N, Mobius W, Corthals K, Li S et al (2012) Critical time window of neuronal cholesterol synthesis during neurite outgrowth. J Neurosci 32:7632–7645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gerstl B, Kahnke MJ, Smith JK, Tavaststjerna MG, Hayman RB (1961) Brain lipids in multiple sclerosis and other diseases. Brain 84:310–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Getz GS, Reardon CA (2006) Diet and murine atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26:242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ghadirian P, Jain M, Ducic S, Shatenstein B, Morisset R (1998) Nutritional factors in the aetiology of multiple sclerosis: a case‐control study in Montreal, Canada. Int J Epidemiol 27:845–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Giubilei F, Antonini G, Di Legge S, Sormani MP, Pantano P, Antonini R et al (2002) Blood cholesterol and MRI activity in first clinical episode suggestive of multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand 106:109–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Haist V, Ulrich R, Kalkuhl A, Deschl U, Baumgärtner W (2012) Distinct spatio‐temporal extracellular matrix accumulation within demyelinated spinal cord lesions in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis. Brain Pathol 22:188–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Halmer R, Walter S, Fassbender K (2014) Sphingolipids: important players in multiple sclerosis. Cell Physiol Biochem 34:111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hansmann F, Herder V, Kalkuhl A, Haist V, Zhang N, Schaudien D et al (2012) Matrix metalloproteinase‐12 deficiency ameliorates the clinical course and demyelination in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis. Acta Neuropathol 124:127–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Haughey NJ (2010) Sphingolipids in neurodegeneration. Neuromolecular Med 12:301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Herz J, Farese RV Jr (1999) The LDL receptor gene family, apolipoprotein B and cholesterol in embryonic development. J Nutr 129 (2S Suppl.):473S–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Heverin M, Meaney S, Lutjohann D, Diczfalusy U, Wahren J, Bjorkhem I (2005) Crossing the barrier: net flux of 27‐hydroxycholesterol into the human brain. J Lipid Res 46:1047–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hewson DC, Phillips MA, Simpson KE, Drury P, Crawford MA (1984) Food intake in multiple sclerosis. Hum Nutr Appl Nutr 38:355–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Homayoun P, Bentejac M, Lecerf J, Bourre JM (1989) Uptake and utilization of double‐labeled high‐density lipoprotein sphingomyelin in isolated brain capillaries of adult rats. J Neurochem 53:1031–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Horner PJ, Thallmair M, Gage FH (2002) Defining the NG2‐expressing cell of the adult CNS. J Neurocytol 31:469–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Irons M, Elias ER, Abuelo D, Bull MJ, Greene CL, Johnson VP et al (1997) Treatment of Smith‐Lemli‐Opitz syndrome: results of a multicenter trial. Am J Med Genet 68:311–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ishii I, Ito Y, Morisaki N, Saito Y, Hirose S (1995) Genetic differences of lipid metabolism in macrophages from C57BL/6J and C3H/HeN mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 15:1189–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kanungo S, Soares N, He M, Steiner RD (2013) Sterol metabolism disorders and neurodevelopment‐an update. Dev Disabil Res Rev 17:197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Karasinska JM, Rinninger F, Lutjohann D, Ruddle P, Franciosi S, Kruit JK et al (2009) Specific loss of brain ABCA1 increases brain cholesterol uptake and influences neuronal structure and function. J Neurosci 29:3579–3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kotter MR, Li WW, Zhao C, Franklin RJ (2006) Myelin impairs CNS remyelination by inhibiting oligodendrocyte precursor cell differentiation. J Neurosci 26:328–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Krisans SK, Ericsson J, Edwards PA, Keller GA (1994) Farnesyl‐diphosphate synthase is localized in peroxisomes. J Biol Chem 269:14165–14169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kuhlmann T, Miron V, Cui Q, Wegner C, Antel J, Bruck W (2008) Differentiation block of oligodendroglial progenitor cells as a cause for remyelination failure in chronic multiple sclerosis. Brain 131 (Pt 7):1749–1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lauer K (1997) Diet and multiple sclerosis. Neurology 49 (2 Suppl. 2):S55–S61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Leoni V, Caccia C (2013) 24S‐hydroxycholesterol in plasma: a marker of cholesterol turnover in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochimie 95:595–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lindberg RLP, De Groot CJA, Certa U, Ravid R, Hoffmann F, Kappos L, Leppert D (2004) Multiple sclerosis as a generalized CNS disease—comparative microarray analysis of normal appearing white matter and lesions in secondary progressive MS. J Neuroimmunol 152:154–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lindner R, Naim HY (2009) Domains in biological membranes. Exp Cell Res 315:2871–2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lock C, Hermans G, Pedotti R, Brendolan A, Schadt E, Garren H et al (2002) Gene‐microarray analysis of multiple sclerosis lesions yields new targets validated in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat Med 8:500–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Maier O, De Jonge J, Nomden A, Hoekstra D, Baron W (2009) Lovastatin induces the formation of abnormal myelin‐like membrane sheets in primary oligodendrocytes. Glia 57:402–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Marrie RA, Horwitz RI (2010) Emerging effects of comorbidities on multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 9:820–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Martin M, Dotti CG, Ledesma MD (2010) Brain cholesterol in normal and pathological aging. Biochim Biophys Acta 1801:934–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mathews ES, Mawdsley DJ, Walker M, Hines JH, Pozzoli M, Appel B (2014) Mutation of 3‐hydroxy‐3‐methylglutaryl CoA synthase I reveals requirements for isoprenoid and cholesterol synthesis in oligodendrocyte migration arrest, axon wrapping, and myelin gene expression. J Neurosci 34:3402–3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Miron VE, Rajasekharan S, Jarjour AA, Zamvil SS, Kennedy TE, Antel JP (2007) Simvastatin regulates oligodendroglial process dynamics and survival. Glia 55:130–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Miron VE, Zehntner SP, Kuhlmann T, Ludwin SK, Owens T, Kennedy TE et al (2009) Statin therapy inhibits remyelination in the central nervous system. Am J Pathol 174:1880–1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mueller AM, Pedre X, Stempfl T, Kleiter I, Couillard‐Despres S, Aigner L et al (2008) Novel role for SLPI in MOG‐induced EAE revealed by spinal cord expression analysis. J Neuroinflammation 5:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nilsson A, Duan RD (2006) Absorption and lipoprotein transport of sphingomyelin. J Lipid Res 47:154–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Nishina PM, Wang J, Toyofuku W, Kuypers FA, Ishida BY, Paigen B (1993) Atherosclerosis and plasma and liver lipids in nine inbred strains of mice. Lipids 28:599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Norton WT, Poduslo SE (1973) Myelination in rat brain: method of myelin isolation. J Neurochem 21:749–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Paigen B, Ishida BY, Verstuyft J, Winters RB, Albee D (1990) Atherosclerosis susceptibility differences among progenitors of recombinant inbred strains of mice. Arteriosclerosis 10:316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Paigen B, Morrow A, Brandon C, Mitchell D, Holmes P (1985) Variation in susceptibility to atherosclerosis among inbred strains of mice. Atherosclerosis 57:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Palavra F, Marado D, Mascarenhas‐Melo F, Sereno J, Teixeira‐Lemos E, Nunes CC et al (2013) New markers of early cardiovascular risk in multiple sclerosis patients: oxidized‐LDL correlates with clinical staging. Dis Markers 34:341–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Patrikios P, Stadelmann C, Kutzelnigg A, Rauschka H, Schmidbauer M, Laursen H et al (2006) Remyelination is extensive in a subset of multiple sclerosis patients. Brain 129 (Pt 12):3165–3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Podbielska M, Krotkiewski H, Hogan EL (2012) Signaling and regulatory functions of bioactive sphingolipids as therapeutic targets in multiple sclerosis. Neurochem Res 37:1154–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. de Preux AS, Goosen K, Zhang W, Sima AA, Shimano H, Ouwens DM et al (2007) SREBP‐1c expression in Schwann cells is affected by diabetes and nutritional status. Mol Cell Neurosci 35:525–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Robinson S, Miller RH (1999) Contact with central nervous system myelin inhibits oligodendrocyte progenitor maturation. Dev Biol 216:359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Saher G, Brugger B, Lappe‐Siefke C, Mobius W, Tozawa R, Wehr MC et al (2005) High cholesterol level is essential for myelin membrane growth. Nat Neurosci 8:468–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Saher G, Quintes S, Nave KA (2011) Cholesterol: a novel regulatory role in myelin formation. Neuroscientist 17:79–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Saher G, Simons M (2010) Cholesterol and myelin biogenesis. Subcell Biochem 51:489–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Salvati S, Sanchez M, Campeggi LM, Suchanek G, Breitschop H, Lassmann H (1996) Accelerated myelinogenesis by dietary lipids in rat brain. J Neurochem 67:1744–1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Schwarz S, Leweling H (2005) Multiple sclerosis and nutrition. Mult Scler 11:24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Scolding N, Franklin R, Stevens S, Heldin CH, Compston A, Newcombe J (1998) Oligodendrocyte progenitors are present in the normal adult human CNS and in the lesions of multiple sclerosis. Brain 121 (Pt 12):2221–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Selivonchick DP, Johnston PV (1975) Fat deficiency in rats during development of the central nervous system and susceptibility to experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Nutr 105:288–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sparks DL, Scheff SW, Hunsaker JC 3rd, Liu H, Landers T, Gross DR (1994) Induction of Alzheimer‐like beta‐amyloid immunoreactivity in the brains of rabbits with dietary cholesterol. Exp Neurol 126:88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sternberg Z, Leung C, Sternberg D, Li F, Karmon Y, Chadha K, Levy E (2013) The prevalence of the classical and non‐classical cardiovascular risk factors in multiple sclerosis patients. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 12:104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sun Y, Lehmbecker A, Kalkuhl A, Deschl U, Sun W, Rohn K et al (2015) STAT3 represents a molecular switch possibly inducing astroglial instead of oligodendroglial differentiation of oligodendroglial progenitor cells in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 41:347–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Swank RL (1950) Multiple sclerosis; a correlation of its incidence with dietary fat. Am J Med Sci 220:421–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Swank RL (1954) Effect of high fat feedings on viscosity of the blood. Science 120:427–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Tettey P, Simpson S Jr, Taylor B, Blizzard L, Ponsonby AL, Dwyer T et al (2014a) An adverse lipid profile is associated with disability and progression in disability, in people with MS. Mult Scler 20:1734–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Tettey P, Simpson S Jr, Taylor B, Blizzard L, Ponsonby AL, Dwyer T et al (2014b) Adverse lipid profile is not associated with relapse risk in MS: results from an observational cohort study. J Neurol Sci 340:230–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Thoolen B, Maronpot RR, Harada T, Nyska A, Rousseaux C, Nolte T et al (2010) Proliferative and nonproliferative lesions of the rat and mouse hepatobiliary system. Toxicol Pathol 38 (7 Suppl.):5S–81S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Timmermans S, Bogie JF, Vanmierlo T, Lutjohann D, Stinissen P, Hellings N, Hendriks JJ (2014) High fat diet exacerbates neuroinflammation in an animal model of multiple sclerosis by activation of the renin angiotensin system. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 9:209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Trapp BD, Nave KA (2008) Multiple sclerosis: an immune or neurodegenerative disorder? Annu Rev Neurosci 31:247–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Trapp BD, Ransohoff R, Rudick R (1999) Axonal pathology in multiple sclerosis: relationship to neurologic disability. Curr Opin Neurol 12:295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ulrich R, Baumgärtner W, Gerhauser I, Seeliger F, Haist V, Deschl U, Alldinger S (2006) MMP‐12, MMP‐3, and TIMP‐1 are markedly upregulated in chronic demyelinating Theiler murine encephalomyelitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 65:783–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ulrich R, Kalkuhl A, Deschl U, Baumgärtner W (2010) Machine learning approach identifies new pathways associated with demyelination in a viral model of multiple sclerosis. J Cell Mol Med 14:434–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ulrich R, Seeliger F, Kreutzer M, Germann PG, Baumgärtner W (2008) Limited remyelination in Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis due to insufficient oligodendroglial differentiation of nerve/glial antigen 2 (NG2)‐positive putative oligodendroglial progenitor cells. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 34:603–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Uranga RM, Keller JN (2010) Diet and age interactions with regards to cholesterol regulation and brain pathogenesis. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res 2010:219683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Warren SA, Warren KG, Greenhill S, Paterson M (1982) How multiple sclerosis is related to animal illness, stress and diabetes. Can Med Assoc J 126:377–382, 85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Waterham HR, Koster J, Romeijn GJ, Hennekam RC, Vreken P, Andersson HC et al (2001) Mutations in the 3beta‐hydroxysterol Delta24‐reductase gene cause desmosterolosis, an autosomal recessive disorder of cholesterol biosynthesis. Am J Hum Genet 69:685–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Weber MS, Steinman L, Zamvil SS (2007) Statins – treatment option for central nervous system autoimmune disease? Neurother 4:693–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Weinstock‐Guttman B, Baier M, Park Y, Feichter J, Lee‐Kwen P, Gallagher E et al (2005) Low fat dietary intervention with omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation in multiple sclerosis patients. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 73:397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Weinstock‐Guttman B, Zivadinov R, Horakova D, Havrdova E, Qu J, Shyh G et al (2013) Lipid profiles are associated with lesion formation over 24 months in interferon‐beta treated patients following the first demyelinating event. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 84:1186–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Weinstock‐Guttman B, Zivadinov R, Mahfooz N, Carl E, Drake A, Schneider J et al (2011) Serum lipid profiles are associated with disability and MRI outcomes in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation 8:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Wender M, Filipek‐Wender H, Stanislawska J (1974) Cholesteryl esters of the brain in demyelinating diseases. Clin Chim Acta 54:269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Westlund KB, Kurland LT (1953) Studies on multiple sclerosis in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and New Orleans, Louisiana. II. A controlled investigation of factors in the life history of the Winnipeg patients. Am J Hyg 57:397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Wheeler D, Bandaru VV, Calabresi PA, Nath A, Haughey NJ (2008) A defect of sphingolipid metabolism modifies the properties of normal appearing white matter in multiple sclerosis. Brain 131 (Pt 11):3092–3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Xuan JW, Kowalski J, Chambers AF, Denhardt DT (1994) A human promyelocyte mRNA transiently induced by TPA is homologous to yeast IPP isomerase. Genomics 20:129–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Zhang SM, Willett WC, Hernan MA, Olek MJ, Ascherio A (2000) Dietary fat in relation to risk of multiple sclerosis among two large cohorts of women. Am J Epidemiol 152:1056–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Zhao S, Hu X, Park J, Zhu Y, Zhu Q, Li H et al (2007) Selective expression of LDLR and VLDLR in myelinating oligodendrocytes. Dev Dyn 236:2708–2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Light microscopy of epoxy resin‐embedded semi‐thin toluidine blue‐stained spinal cord.

Figure S2. Semiquantitative assessment of demyelination.

Table S1. Fold changes and P‐values of genes associated with cholesterol synthesis, metabolism and transport.